1. Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in companion animals, particularly dogs and cats, has been steadily increasing and is now a significant concern in veterinary clinical practice. Although various antimicrobial stewardship programs (ASPs) have been proposed to mitigate this trend [

1,

2,

3], effective strategies for reducing resistance rates in small animal practice, especially in veterinary referral hospital settings, remain underdeveloped. Inappropriate antimicrobial use is influenced by multiple factors, including institutional prescribing culture, diagnostic limitations, and case complexity, particularly in secondary or referral facilities [

4,

5]. Effective interventions must be context-specific and guided by data generated in each hospital environment.

Previous studies have shown that restricting the use of third-generation cephalosporins and fluoroquinolones can reduce the prevalence of methicillin-resistant staphylococci (MRS) and extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing

Escherichia coli in primary care veterinary settings [

6]. Furthermore, cumulative antibiograms have proven useful for monitoring resistance trends and guiding antimicrobial selection [

7]. However, no study has employed antibiogram-based approaches to identify hospital-specific hazard factors or determine critical control points for resistance emergence in veterinary referral hospitals. Moreover, although antimicrobial use and resistance data collected within hospitals offer valuable insights, such internal monitoring systems have not been widely leveraged to design tailored interventions.

We hypothesized that characterizing current antimicrobial use and resistance patterns, followed by the implementation of targeted interventions based on these findings, could effectively reduce hospital-associated AMR. Therefore, this study aimed to develop a hospital-specific cumulative antibiogram, evaluate local antimicrobial use and resistance patterns, and assess their utility in identifying key intervention points to reduce AMR in a secondary care companion animal hospital.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Analysis of Antimicrobial Use and Resistance for Identification of Critical Control Points

This study was conducted at the University of Tokyo Veterinary Medical Center, a secondary referral hospital providing advanced care for companion animals. Clinical bacterial isolates and antimicrobial prescription data from August 2016 to August 2018 were retrospectively analyzed to identify hospital-specific hazard points contributing to AMR. For historical comparison, dispensing records from 2013 to 2014 were also reviewed to evaluate trends in second-line antimicrobial use.

Bacterial identification and antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) were outsourced to the Sanritsu Zelkova Veterinary Laboratory and conducted in accordance with the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) M100-S26 or CLSI VET01-S guidelines. Antimicrobial use was calculated as days of therapy [

8] based on prescription counts. Annual cumulative antibiograms were constructed to visualize susceptibility trends for major pathogens, particularly

Staphylococcus pseudintermedius and

Enterobacteriaceae. These data were integrated to perform hazard analysis and identify critical control points where inappropriate or high-risk prescribing practices may contribute to resistance emergence.

2.2. Intervention Strategy

Based on the analysis of the 2016–2018 data, several concerns regarding antimicrobial use were identified, consistent with findings from previous studies [

4,

5]. These included empiric prescriptions without pathogen identification, a lack of effective second-line options for multidrug-resistant organisms, excessive use of carbapenems and fluoroquinolones, and misinterpretation of AST results due to reporting on intrinsically resistant organisms. In response, a hospital-specific antimicrobial stewardship intervention was initiated in January 2019. All strategies were implemented as non-mandatory recommendations without enforcement authority. The core components included:

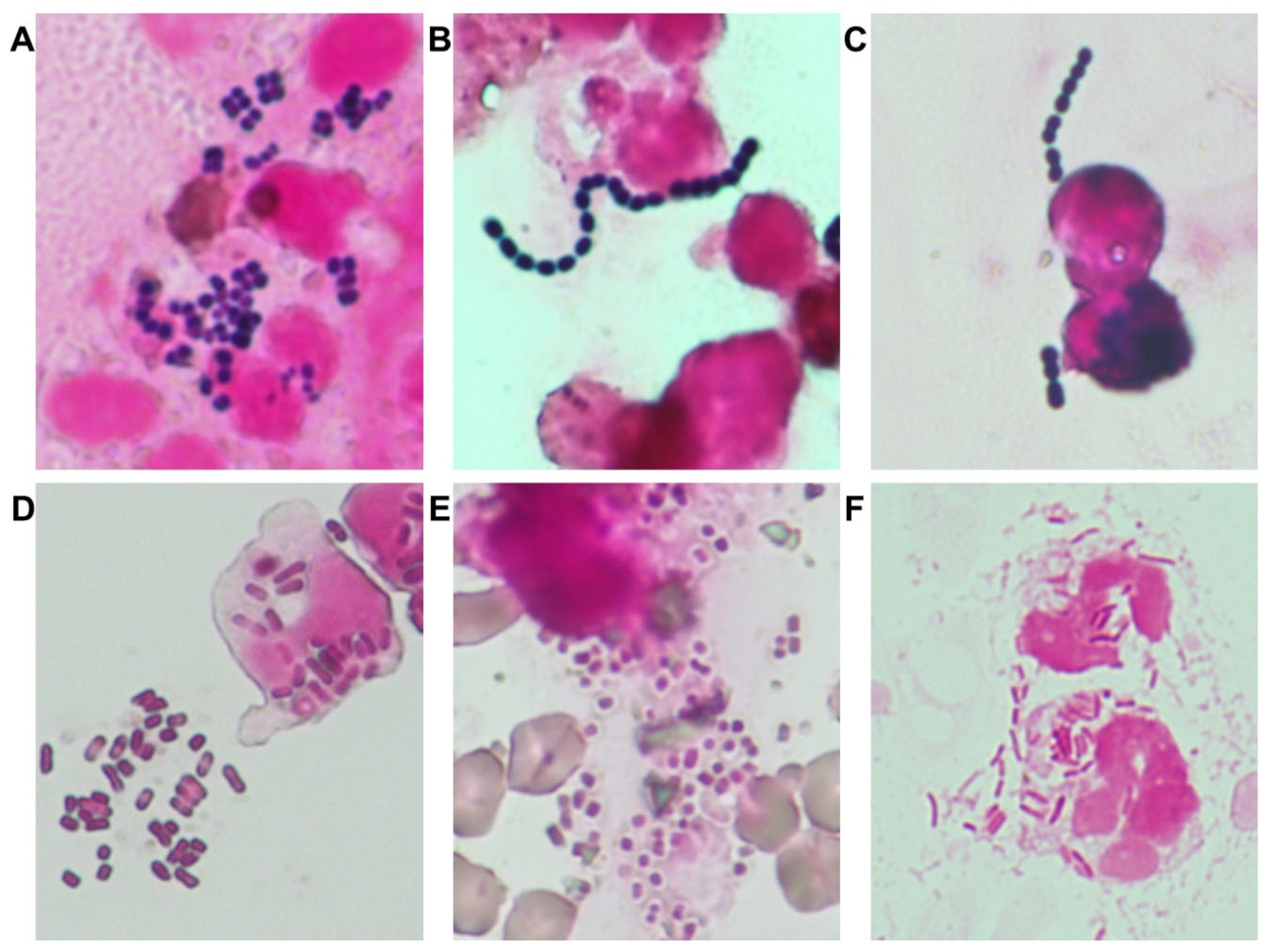

1. Proactive use of Gram staining: Gram staining was implemented as a frontline diagnostic tool to guide early pathogen estimation, particularly for six major organisms relevant to small animal medicine (

Figure 1), as supported by prior studies [

9,

10,

11]. Gram staining results were used in conjunction with antibiogram trends and clinical severity to guide empirical therapy.

2. Empirical therapy optimization: Empirical treatment protocols were revised based on Gram stain results and annual antibiogram data to identify and eliminate ineffective antibiotic choices. Narrow-spectrum agents were prioritized, and the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics was discouraged unless supported by microbiological evidence. Additionally, pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD)-based dosing regimens have been developed for certain antibiotics using Monte Carlo simulations [

12].

3. Restriction of high-risk antimicrobials: Use of high-risk agents, particularly carbapenems and fluoroquinolones, was restricted to cases supported by culture and sensitivity data.

4. Refinement of AST result reporting: Laboratory reporting protocols were modified to suppress susceptibility data for organisms with known intrinsic resistance, thereby preventing clinicians from misinterpreting AST reports and inadvertently prescribing ineffective agents.

Additionally, structured educational sessions on antimicrobial resistance, prescribing principles, and optimal stewardship practices were provided to veterinary interns and clinical staff. The intervention’s effectiveness was evaluated by comparing antimicrobial use patterns and resistance rates before and after the intervention.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Bayesian inference was used to identify antimicrobial classes that were significantly overprescribed relative to national trends. The higher of the 2016 or 2020 national usage proportions (based on official sales data from the National Veterinary Assay Laboratory:

https://www.maff.go.jp/nval/yakuzai/yakuzai_p3_6.html) was used as the prior. Institutional prescription counts were used to update the beta distribution, and posterior distributions were generated by drawing 10,000 samples using the Rbeta function in R. Overprescription was considered statistically significant if the posterior probability was > 0.95.

To assess resistance trends from 2017 to 2024, binomial logistic regression was performed with year as a continuous predictor. The log-odds slope and corresponding odds ratio (OR) per year were calculated to evaluate significant changes in resistance rates. All analyses were performed in R (v4.4.1) using the ggplot2 (v3.5.1), dplyr (v1.1.4), tidyr (v1.3.1), and multcomp (v1.4.26) packages.

3. Results

3.1. Bacterial Epidemiology, Antimicrobial Resistance, and Identification of Critical Control Points

Between August 2016 and August 2018, 878 clinical bacterial isolates were collected from the University of Tokyo Veterinary Medical Center. The six most frequently identified organisms were Staphylococcus spp. (n = 214),

E. coli (n = 185), Enterococcus spp. (n = 125),

Klebsiella spp. (n = 96), Streptococcus spp. (n = 56), and Pseudomonas spp. (n = 45) (

Figure 1). Among these, antimicrobial resistance was notably prevalent: MRS accounted for 64% of

Staphylococcus spp. isolates; ESBL-producing

E. coli and

Klebsiella spp. were detected in 51% and 78% of respective isolates

Bayesian analysis revealed that as early as 2013, the institutional use of fluoroquinolones and carbapenems significantly exceeded the national usage proportions, with posterior probabilities surpassing 0.99. This trend persisted through 2016, during which additional overprescription of penems was also identified (posterior probability = 1.00), indicating sustained overuse of multiple broad-spectrum agents. Integrating AST results with dispensing data identified several potential critical control points, including the empirical overuse of second-line agents, insufficient prioritization of narrow-spectrum alternatives, and inconsistent antimicrobial selection based on Gram-staining results and clinical severity.

3.2. Impact of Intervention on Antimicrobial Use and Resistance Trends

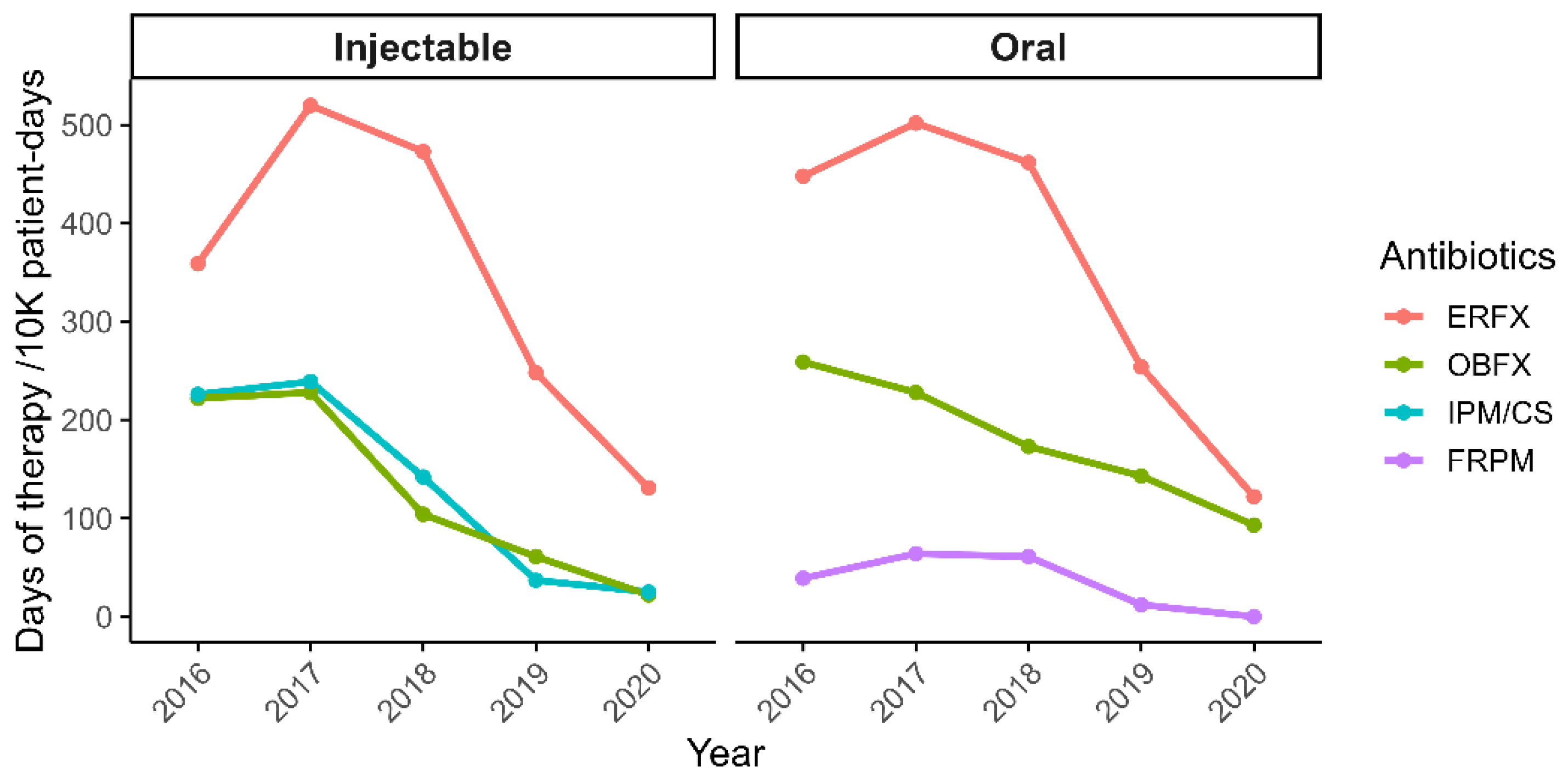

Following the implementation of antimicrobial stewardship interventions, prescription rates documented in medical records decreased by over 50% by 2020, with total days of therapy per 10,000 patient-days declining from 5,262 to 2,575. Notably, usage of injectable antimicrobials showed marked reductions: imipenem/cilastatin decreased by 88%, enrofloxacin (ERFX) by 71%, and orbifloxacin (OBFX) by 88%. Oral formulations followed similar trends, with ERFX and OBFX decreasing by 72% and 90%, respectively, and faropenem was completely discontinued (100% reduction;

Figure 2).

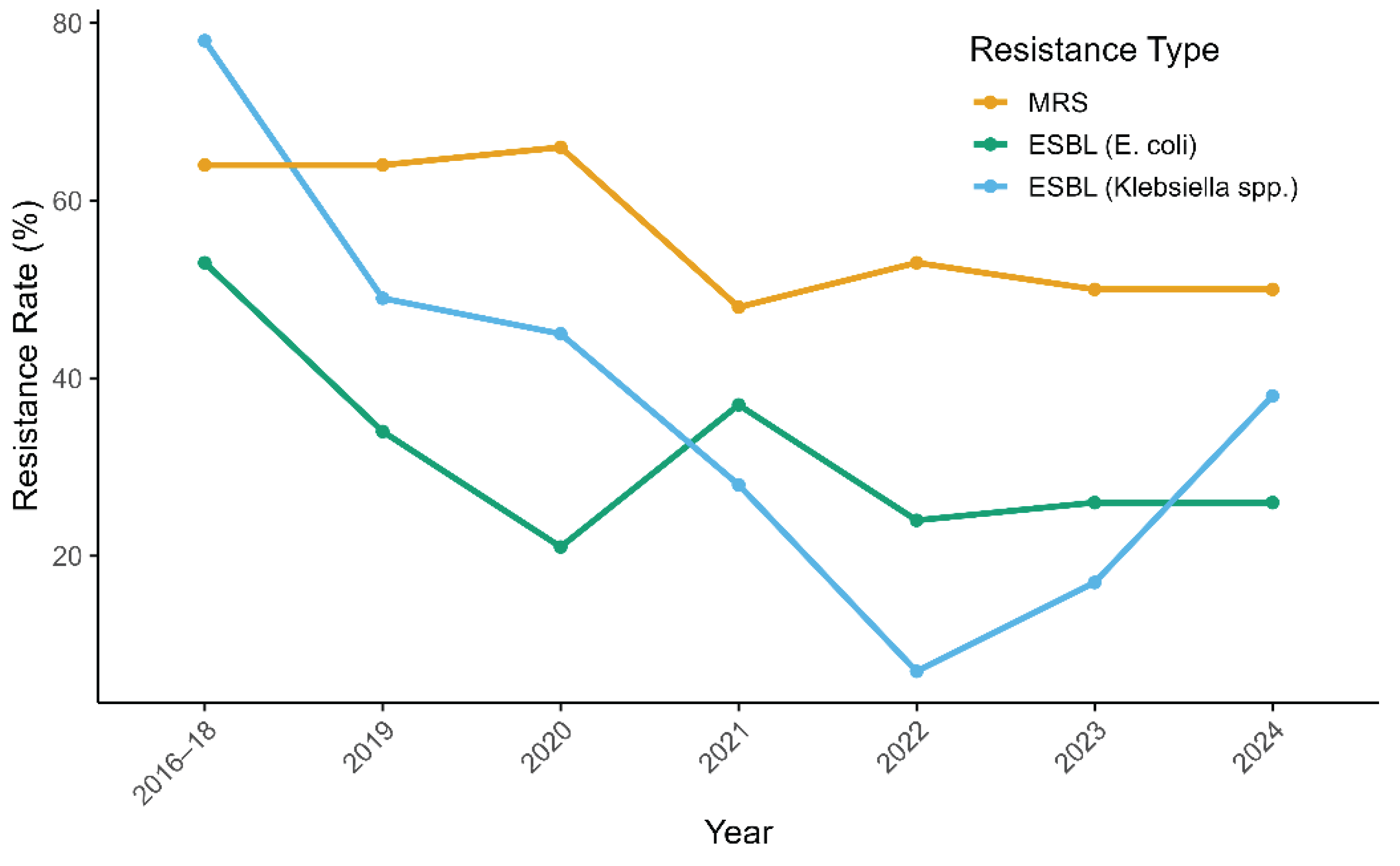

Corresponding shifts in resistance rates were also observed, particularly among gram-negative bacteria. By 2022, the prevalence of ESBL-producing E. coli decreased from 53% to 24%, while that of ESBL-producing Klebsiella spp. dropped from 78% to 7%. In contrast, MRS prevalence remained high, showing only a modest decline (from 64% to 53%). To assess these trends, binomial logistic regression was performed using data from 2017 to 2022. A statistically significant decreasing trend in resistance was observed for all three pathogens. The OR per year was 0.90 (p = 0.0179) for MRS, 0.78 (p = 2.00 × 10−6) for ESBL-producing E. coli, and 0.55 (p = 9.38 × 10−11) for ESBL-producing Klebsiella spp.

In September 2022, stewardship leadership transitioned from the original lead (TM) to a successor (RF). During 2023–2024, MRS rates remained stable at 50%, the prevalence of ESBL-producing

E. coli remained at 26%, and ESBL-producing

Klebsiella spp. increased from 17% to 38% (

Figure 3). To assess the potential effect of leadership change on resistance patterns, a separate logistic regression was used to compare resistance rates between the two-year periods before (2021–2022) and after (2023–2024) the transition. The ORs for the earlier period relative to the latter were 1.02 (

p = 0.918) for MRS, 1.31 (

p = 0.310) for ESBL-producing

E. coli, and 0.70 (

p = 0.498) for ESBL-producing

Klebsiella spp., indicating no statistically significant impact of the leadership transition on resistance trends.

4. Discussion

The antimicrobial stewardship intervention implemented at our secondary referral hospital led to a substantial reduction in overall antimicrobial use and coincided with marked improvements in resistance rates among gram-negative bacteria. By 2020, total antimicrobial prescriptions had decreased by over 50%, with the most significant reductions observed in broad-spectrum agents such as carbapenems and fluoroquinolones. These reductions were temporally associated with declines in the prevalence of ESBL-producing

E. coli and

Klebsiella spp., which decreased from 53% to 24% and from 78% to 7%, respectively, by 2022. These findings are consistent with previous studies highlighting the role of β-lactam and fluoroquinolone restriction in mitigating resistance among Enterobacteriaceae [

6,

13], and reinforce the clinical utility of cumulative antibiograms for empirical treatment selection.

In contrast, the prevalence of MRS declined only modestly, from 64% to 53% by 2022, and remained stable at approximately 50% thereafter. This limited response suggests that our stewardship strategies were less effective in controlling resistance among MRS. Although previous studies have reported reductions in MRS rates following antimicrobial stewardship efforts [

6,

7], several factors may have limited effectiveness in this study. These include suboptimal adherence to stewardship recommendations, continued empirical use of β-lactam antibiotics for presumed staphylococcal infections, and insufficient de-escalation based on culture results. Additionally, unlike gram-negative organisms, which are primarily driven by antimicrobial selective pressure, MRS prevalence may not be as responsive to stewardship interventions alone [

14]. Therefore, additional strategies such as decolonization protocols and enhanced infection control measures may be required to achieve further reductions.

Although stewardship leadership transitioned in September 2022 from the original lead (TM) to a new clinician (RF), statistical analysis revealed no significant changes in resistance rates across the 2021–2022 and 2023–2024 periods. ORs comparing the earlier to the latter period were 1.02 for MRS, 1.31 for ESBL-producing E. coli, and 0.70 for ESBL-producing Klebsiella spp. However, the increase in ESBL-producing Klebsiella from 17% to 38% during the latter period suggests a potential weakening of stewardship impact, warranting further attention. These findings underscore the importance of continuity in program leadership, consistent institutional support, and structured handovers to maintain long-term effectiveness. Periodic reviews of antibiogram trends are also essential to adapt interventions to evolving resistance dynamics.

This study has several limitations. First, the adoption rate of individual recommendations was not assessed due to the voluntary nature of the interventions. Nevertheless, institution-wide prescribing and resistance data were used to determine the overall effect. Second, the distinct effects of each intervention component were not analyzed separately, as they were implemented as part of a coordinated strategy. Third, external infection control practices associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, such as increased handwashing, masking, and environmental sanitation, may have influenced resistance trends. However, the use of multi-year pre- and post-intervention data helped mitigate this limitation and supported the internal validity of the findings.

5. Conclusions

Hospital-specific antimicrobial stewardship programs, including in-hospital education and antibiotic selection guided by antibiograms, have been effective in reducing resistance among gram-negative bacteria. These programs also show promise in controlling MRS, although continued efforts are needed to address the persistent resistance in gram-positive bacteria.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, software, visualization, validation, and writing—original draft preparation TM; investigation, TM and RF; data curation, TM, RF, and YT; writing—review and editing TM, RF, YT, DN, SN, TN, RN, and YM; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because all data were obtained retrospectively from routine clinical records and microbiological test results, with no identifiable patient information, and no additional procedures beyond standard clinical care. The antimicrobial stewardship interventions implemented during the study were non-mandatory recommendations without enforcement, and all activities were conducted under the institutional ethical guidelines for clinical quality improvement and surveillance.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to institutional policy and the inclusion of clinical records that may contain sensitive or indirectly identifiable information.

Acknowledgments

This article is a revised and expanded version of a paper entitled "Assessing Antimicrobial Resistance in Companion Animals at a Referral Hospital: The Impact of Antimicrobial Stewardship Strategies", which was presented at the 2024 ACVIM Forum in Minneapolis, Minnesota, on June 8 [

15]. The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the clinical staff, interns, and laboratory personnel at the University of Tokyo Veterinary Medical Center for their invaluable support in data collection, microbiological diagnostics, and implementing antimicrobial stewardship activities throughout the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AMR |

Antimicrobial Resistance |

| ASP |

Antimicrobial Stewardship Program |

| AST |

Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing |

| CLSI |

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute |

| ERFX |

Enrofloxacin |

| ESBL |

Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase |

| MRS |

Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococci |

| OBFX |

Orbifloxacin |

| OR |

Odds Ratio |

| PK/PD |

Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic |

References

- Allerton, F.; Prior, C.; Bagcigil, A.F.; Broens, E.; Callens, B.; Damborg, P.; Dewulf, J.; Filippitzi, M.E.; Carmo, L.P.; Gomez-Raja, J.; et al. Overview and Evaluation of Existing Guidelines for Rational Antimicrobial Use in Small-Animal Veterinary Practice in Europe. Antibiotics (Basel) 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, E.; Costin, M.; Granick, J.; Kornya, M.; Weese, J.S. 2022 AAFP/AAHA Antimicrobial Stewardship Guidelines. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2022, 58, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weese, J.S.; Giguere, S.; Guardabassi, L.; Morley, P.S.; Papich, M.; Ricciuto, D.R.; Sykes, J.E. ACVIM consensus statement on therapeutic antimicrobial use in animals and antimicrobial resistance. J Vet Intern Med 2015, 29, 487–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardefeldt, L.Y.; Gilkerson, J.R.; Billman-Jacobe, H.; Stevenson, M.A.; Thursky, K.; Bailey, K.E.; Browning, G.F. Barriers to and enablers of implementing antimicrobial stewardship programs in veterinary practices. J Vet Intern Med 2018, 32, 1092–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, C.; Smith, M.; Currie, K.; Dickson, A.; Smith, F.; Davis, M.; Flowers, P. Exploring the behavioural drivers of veterinary surgeon antibiotic prescribing: A qualitative study of companion animal veterinary surgeons in the UK. BMC Vet Res 2018, 14, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurita, G.; Tsuyuki, Y.; Murata, Y.; Takahashi, T.; Veterinary Infection Control Association, A.M.R.W.G. Reduced rates of antimicrobial resistance in Staphylococcus intermedius group and Escherichia coli isolated from diseased companion animals in an animal hospital after restriction of antimicrobial use. J Infect Chemother 2019, 25, 531–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyori, K.; Shishikura, T.; Shimoike, K.; Minoshima, K.; Imanishi, I.; Toyoda, Y. Influence of hospital size on antimicrobial resistance and advantages of restricting antimicrobial use based on cumulative antibiograms in dogs with Staphylococcus pseudintermedius infections in Japan. Vet Dermatol 2021, 32, 668-e178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redding, L.E.; Grunwald, H.; Melofchik, C.; Meily, P.; Henry, A.; Stefanovski, D. Comparison of animal daily doses and days of therapy for antimicrobials in species of veterinary importance. Prev Vet Med 2020, 176, 104942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuyama, H.; Yamashiro, S.; Kinjo, K.; Tamaki, H.; Kishaba, T. Validation of sputum Gram stain for treatment of community-acquired pneumonia and healthcare-associated pneumonia: a prospective observational study. BMC Infect Dis 2014, 14, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Way, L.I.; Sullivan, L.A.; Johnson, V.; Morley, P.S. Comparison of routine urinalysis and urine Gram stain for detection of bacteriuria in dogs. J Vet Emerg Crit Care (San Antonio) 2013, 23, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimura, J.; Kinoshita, T.; Yamakawa, K.; Matsushima, A.; Nakamoto, N.; Hamasaki, T.; Fujimi, S. Impact of Gram stain results on initial treatment selection in patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia: a retrospective analysis of two treatment algorithms. Crit Care 2017, 21, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumoto, M.; Motegi, T.; Uno, H.; Yokono, M.; Harada, K. Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic analysis of cefmetazole against extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in dogs using Monte Carlo Simulation. Front Vet Sci 2023, 10, 1270137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giamarellou, H.; Galani, L.; Karavasilis, T.; Ioannidis, K.; Karaiskos, I. Antimicrobial Stewardship in the Hospital Setting: A Narrative Review. Antibiotics (Basel) 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karanika, S.; Paudel, S.; Grigoras, C.; Kalbasi, A.; Mylonakis, E. Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Clinical and Economic Outcomes from the Implementation of Hospital-Based Antimicrobial Stewardship Programs. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2016, 60, 4840–4852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motegi, T.; Nagakubo, D.; Maeda, S.; Yonezawa, T.; Nishimura, R.; Y., M. Assessing Antimicrobial Resistance in Companion Animals at a Referral Hospital: The Impact of Antimicrobial Stewardship Strategies. In Proceedings of the 2024 ACVIM Forum, Minnesota, June 8, 2024.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).