Submitted:

27 June 2025

Posted:

30 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

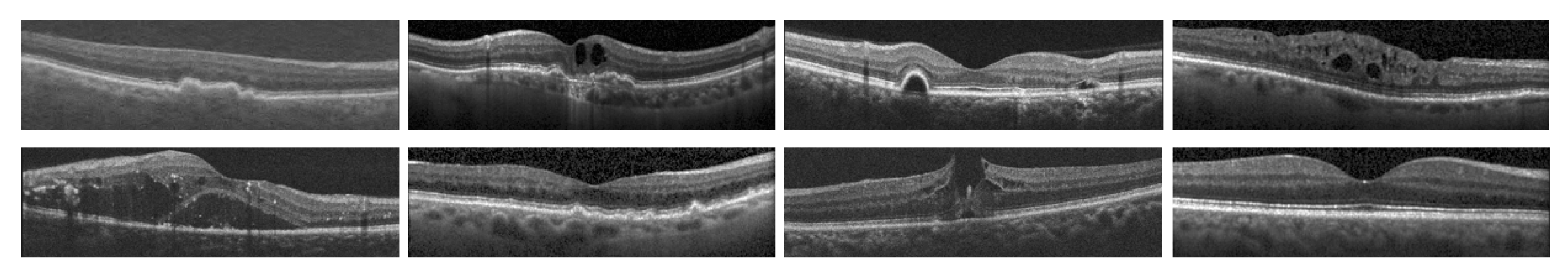

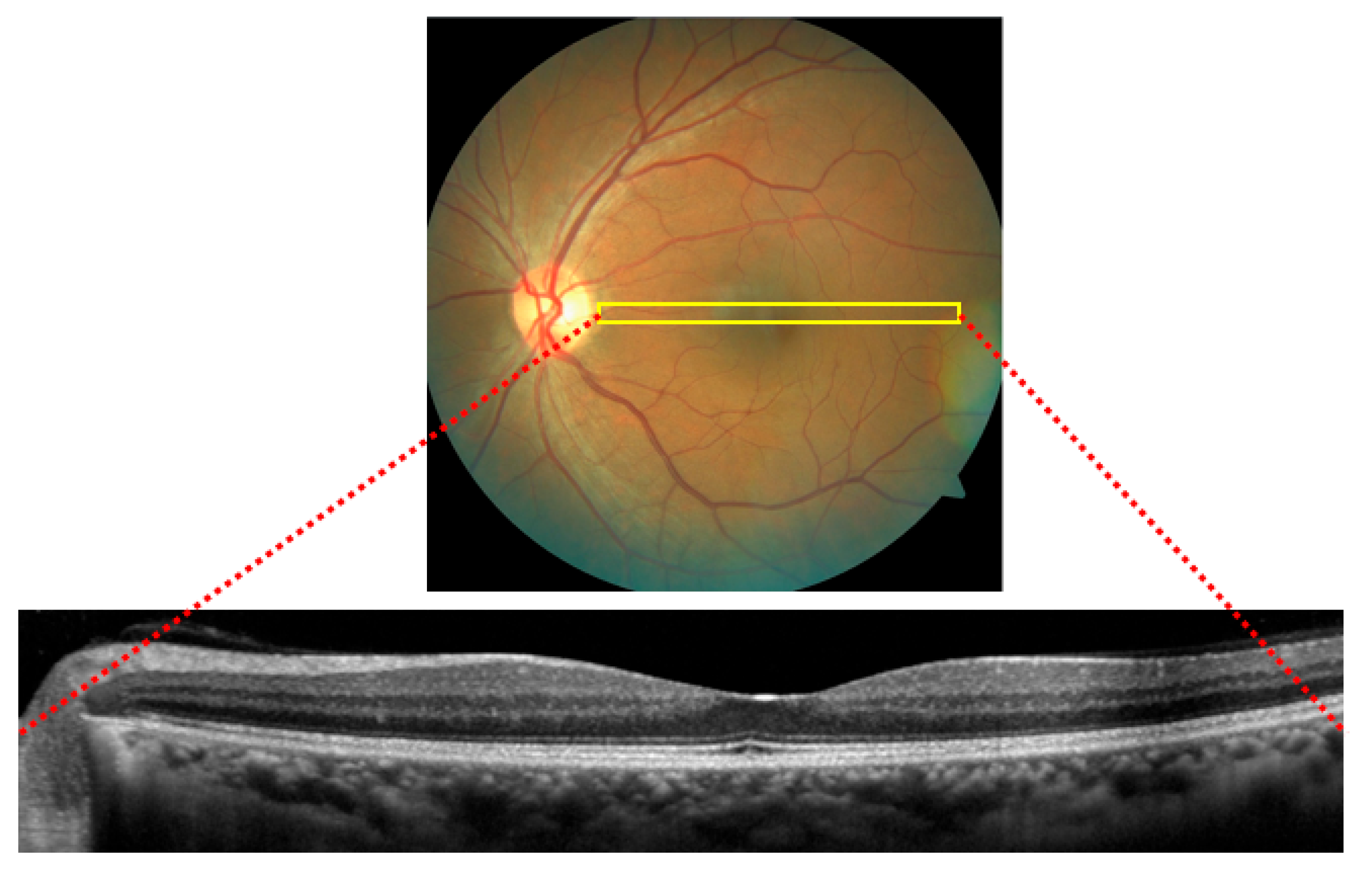

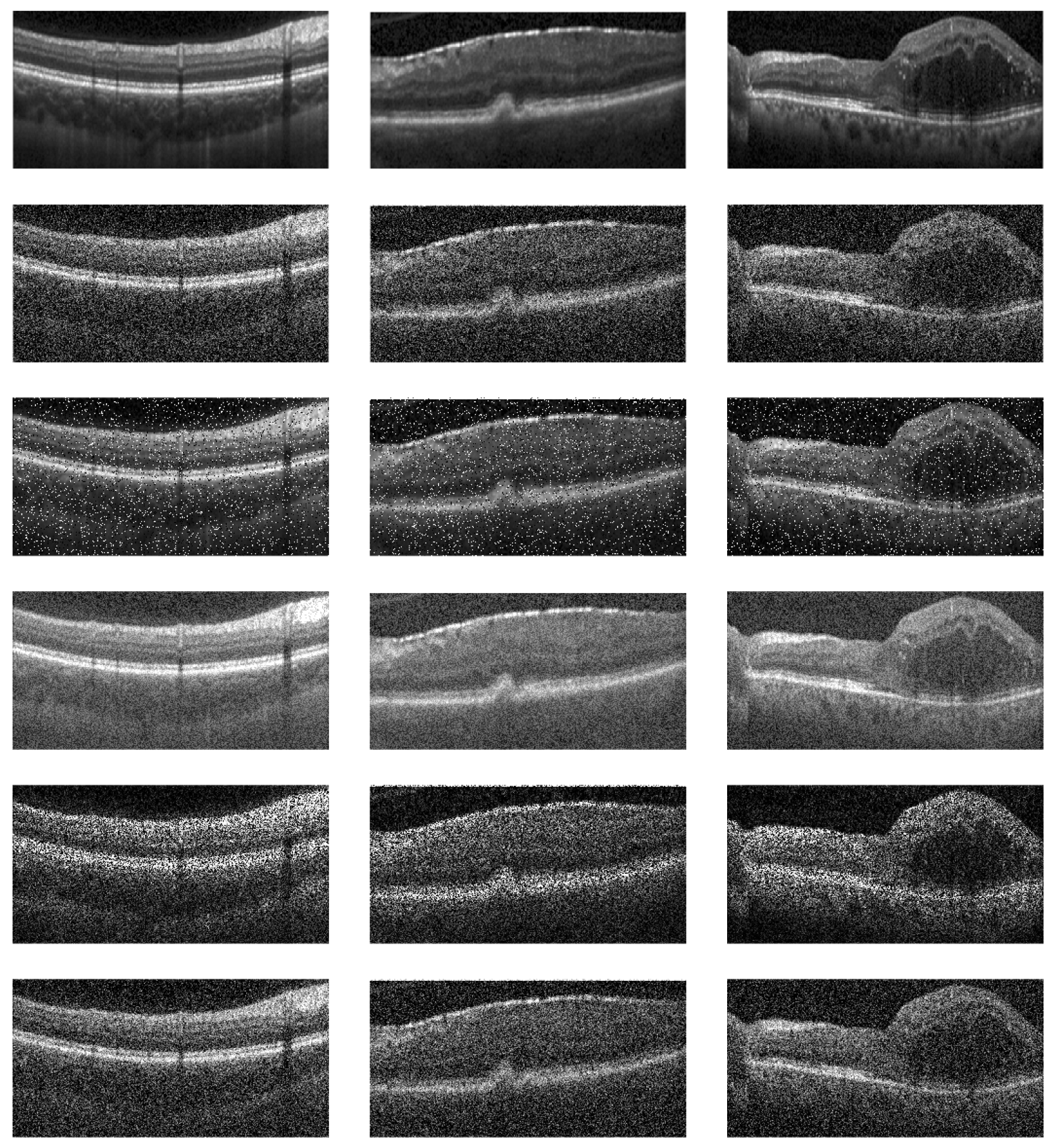

1.1. Optical Coherence Tomography

1.2. Feature Extraction Techniques

1.3. Other Survey Literature on OCT

- Provides a systematic review of the existing methods of feature extraction from OCT images, categorizing them into hand-crafted and deep learning-based approaches:

- 2.

- Assesses the impact of dataset choice on the performance of feature extraction methods.

- 3.

- Explores the emerging field of adversarial conditions in medical imaging, particularly in OCT, to propose future directions for research that could lead to more robust, accurate, and clinically relevant feature extraction technologies.

2. Review of OCT Datasets for Ocular Disorder Classification

3. Hand-Crafted Feature Extraction Techniques

4. Deep Learning Approaches

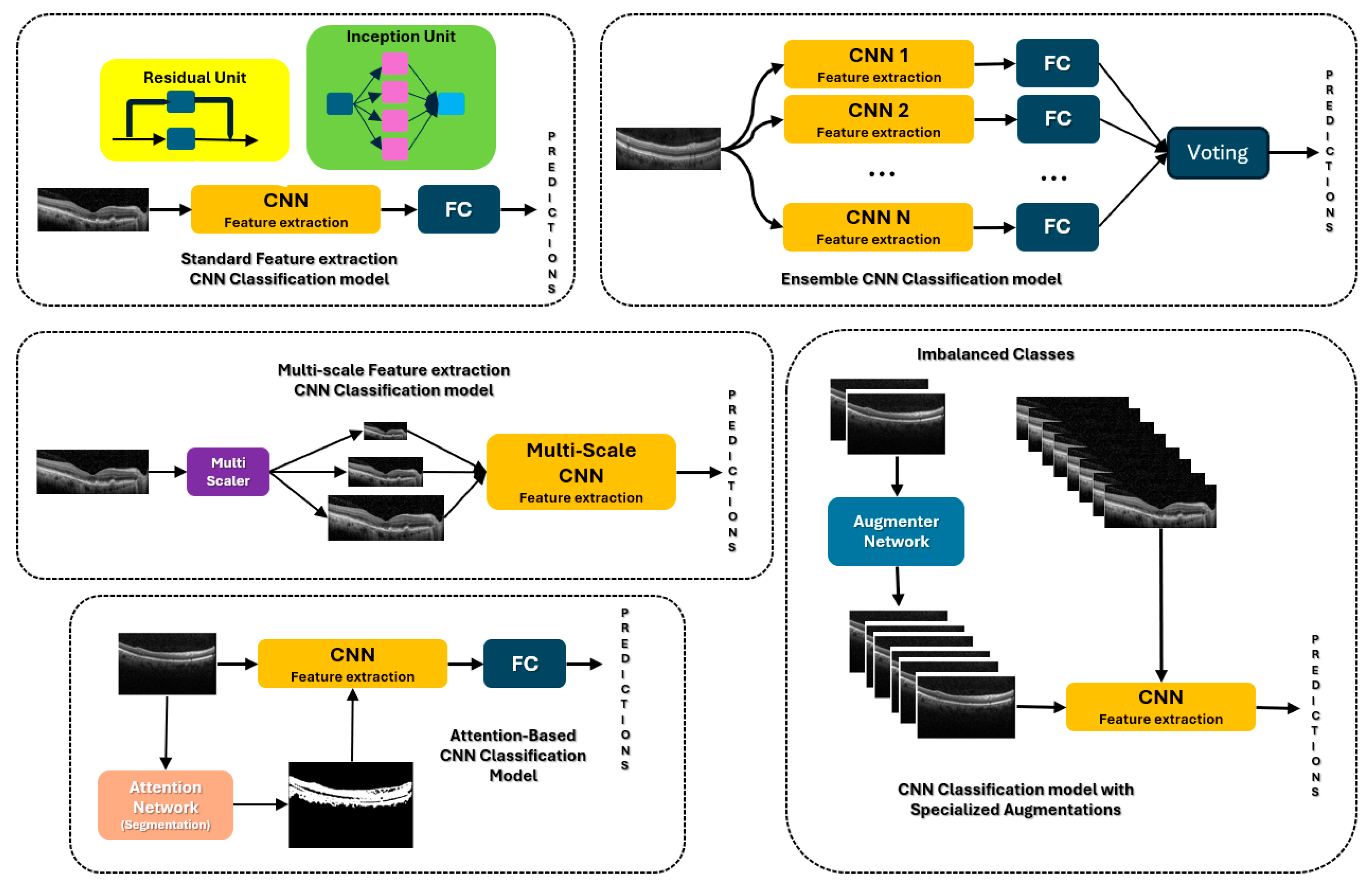

4.1. CNNs

4.2. CNN with Attention

4.3. CNN Ensembles and Multiscale

4.4. CNN Augmentations

4.5. Transformers

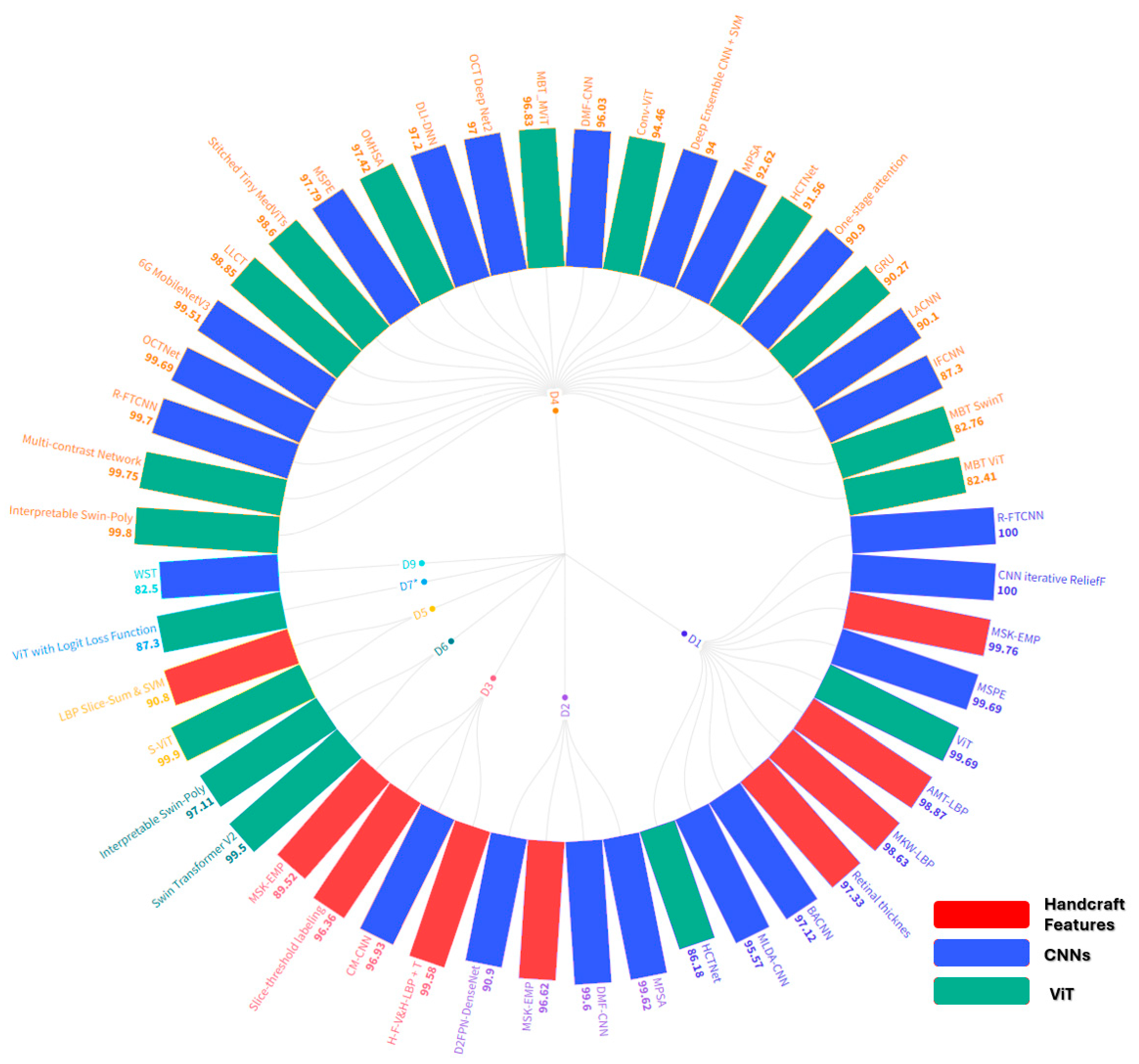

5. Comparative Analysis

6. Future Work

6.1. Medical Imaging with Adversarial Samples

6.2. Incorporation of Large Language Models

6.3. Proposals for Future Research

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ignacio, A. Viedma, David Alonso-Caneiro, Scott A. Read, Michael J. Collins, Deep learning in retinal optical coherence tomography (OCT): A comprehensive survey. Neurocomputing 2022, 507, 247–264, ISSN 0925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M. , Fraz, M. M. & Barman, S.A. Computer Vision Techniques Applied for Diagnostic Analysis of Retinal OCT Images: A Review. Arch Computat Methods Eng 2017, 24, 449–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meiburger, K.M.; Salvi, M.; Rotunno, G.; Drexler, W.; Liu, M. Automatic Segmentation and Classification Methods Using Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography (OCTA): A Review and Handbook. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 9734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Pan and X. Chen, "Retinal OCT Image Registration: Methods and Applications. in IEEE Reviews in Biomedical Engineering 2023, 16, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsharkawy, M.; Elrazzaz, M.; Ghazal, M.; Alhalabi, M.; Soliman, A.; Mahmoud, A.; El-Daydamony, E.; Atwan, A.; Thanos, A.; Sandhu, H.S.; et al. Role of Optical Coherence Tomography Imaging in Predicting Progression of Age-Related Macular Disease: A Survey. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharuka, R. Mhatre, D., Patil, N., Chitnis, S., Karnik, M. (2021). A Survey on Classification and Prediction of Glaucoma and AMD Based on OCT and Fundus Images. In: Raj, J.S. (eds) International Conference on Mobile Computing and Sustainable Informatics . ICMCSI 2020. EAI/Springer Innovations in Communication and Computing. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- R. Kiefer, J. Steen, M. Abid, M. R. Ardali and E. Amjadian, "A Survey of Glaucoma Detection Algorithms using Fundus and OCT Images," 2022 IEEE 13th Annual Information Technology, Electronics and Mobile Communication Conference (IEMCON), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2022, pp. 0191-0196. [CrossRef]

- M. Naveed, A. Ramzan and M. U. Akram, "Clinical and technical perspective of glaucoma detection using OCT and fundus images: A review," 2017 1st International Conference on Next Generation Computing Applications (NextComp), Mauritius, 2017, pp. [CrossRef]

- Ran, A.R. , Tham, C.C., Chan, P.P. et al. Deep learning in glaucoma with optical coherence tomography: a review. Eye 2021, 35, 188–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammed Halil Akpinar, Abdulkadir Sengur, Oliver Faust, Louis Tong, Filippo Molinari, U. Rajendra Acharya, Artificial Intelligence in Retinal Screening Using OCT Images: A Review of the Last Decade (2013-2023). Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine 2024, 108253, ISSN 0169-2607. [CrossRef]

- K. A. Nugroho, "A Comparison of Handcrafted and Deep Neural Network Feature Extraction for Classifying Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) Images," 2018 2nd International Conference on Informatics and Computational Sciences (ICICoS), Semarang, Indonesia, 2018, pp. 1-6. [CrossRef]

- S. K. Dash, P. K. Sethy, A. Das, S. Jena and A. Nanthaamornphong. Advancements in Deep Learning for Automated Diagnosis of Ophthalmic Diseases: A Comprehensive Review. 2024; 12, 171221–171240. [CrossRef]

- P. P. Srinivasan, L.A. Kim, P.S. Mettu, S.W. Cousins, G.M. Comer, J.A. Izatt, and S. Farsiu, "Fully automated detection of diabetic macular edema and dry age-related macular degeneration from optical coherence tomography images. BioMedical Optics Express 2014, 5, 3568–3577. [CrossRef]

- Rasti, R.; Rabbani, H.; Mehridehnavi, A.; Hajizadeh, F. Macular OCT Classification Using a Multiscale Convolutional NeuralNetwork Ensemble. IEEE Trans. Med Imaging 2017, 37, 1024–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotoudeh-Paima, S. Labeled Retinal Optical Coherence Tomography Dataset for Classification of Normal, Drusen, and CNV Cases, Mendeley Data, 2021, V1. Available online: https://paperswithcode.com/dataset/labeled-retinal-optical-coherence-tomography.

- Kermany, Daniel; Zhang, Kang; Goldbaum, Michael (2018), “Labeled Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) and Chest X-Ray Images for Classification”, Mendeley Data, V2. [CrossRef]

- S. Farsiu, SJ. Chiu, R.V. O’Connell, F.A. Folgar, E. Yuan, J.A. Izatt, and C.A. Toth "Quantitative Classification of Eyes with and without Intermediate Age-related Macular Degeneration Using Optical Coherence Tomography. Ophthalmology 2014, 121, 162–172. [CrossRef]

- O.S. Naren, Retinal OCT- C8, 2021, URL https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/obulisainaren/retinal-oct-c8.

- Yu-Ying Liu, Mei Chen, Hiroshi Ishikawa, Gadi Wollstein, Joel S. Schuman, James M. Rehg, Automated macular pathology diagnosis in retinal OCT images using multi-scale spatial pyramid and local binary patterns in texture and shape encoding. Medical Image Analysis 2011, 15, 748–759. [CrossRef]

- Lemaître G, Rastgoo M, Massich J, Sankar S, Mériaudeau F, Sidibé D. Classification of SD-OCT volumes with LBP: application to DME detection. Proceedings of the ophthalmic medical image analysis second international workshop, OMIA 2015, held in conjunction with MICCAI2015, Munich, Germany, 9 Oct 2015; 2015. p. 9–16. [CrossRef]

- P. Gholami, P. Roy, M.K. Parthasarathy, and V. Lakshminarayanan, “ OCTID: Optical Coherence Tomography Image365 Database. Comput. and Elec. Engin. 2020, 81. [CrossRef]

- D. Song et al., "Deep Relation Transformer for Diagnosing Glaucoma with Optical Coherence Tomography and Visual Field Function. in IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging 2021, 40, 2392–2402. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peyman Gholami, Mohsen Sheikh Hassani, Mohana Kuppuswamy Parthasarathy, John S. Zelek, and Vasudevan Lakshminarayanan "Classification of optical coherence tomography images for diagnosing different ocular diseases. Proc. SPIE 10487, Multimodal Biomedical Imaging XIII, 1048705 (16 March 2018); [CrossRef]

- Yu, Yao-Wen, Cheng-Hung Lin, Cheng-Kai Lu, Jia-Kang Wang, and Tzu-Lun Huang. Automated Age-Related Macular Degeneration Detector on Optical Coherence Tomography Images Using Slice-Sum Local Binary Patterns and Support Vector Machine. Sensors 2023, 23, 7315. [CrossRef]

- Guillaume Lemaître,1Mojdeh Rastgoo,1Joan Massich,1Carol Y. Cheung,2Tien Y. Wong,3Ecosse Lamoureux,3Dan Milea,3Fabrice Mériaudeau,1,4and Désiré Sidibé1, Classification of SD-OCT Volumes Using Local Binary Patterns: Experimental Validation for DME Detection. Hindawi 2016, 2016, 3298606. [CrossRef]

- K. Alsaih et al., "Classification of SD-OCT volumes with multi pyramids, LBP and HOG descriptors: Application to DME detections," 2016 38th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), Orlando, FL, USA, 2016, pp. 1344-1347. [CrossRef]

- Alex Liew "Multi-kernel Wiener local binary patterns for OCT ocular disease detections with resiliency to Gaussian noises. Proc. SPIE 13033, Multimodal Image Exploitation and Learning 2024, 2024, 130330H. [CrossRef]

- A. Liew, S. Agaian, S. Benbelkacem, Distinctions between Choroidal Neovascularization and Age Macular Degeneration in Ocular Disease Predictions via Multi-Size Kernels ξcho-Weighted Median Patterns. Diagnostics. 2023, 13, 729. [CrossRef]

- A. Liew, L. Ryan, and S. Agaian "Alpha mean trim texture descriptors for optical coherence tomography eye classification. Proc. SPIE 12100. Multimodal Image Exploitation and Learning 2022, 2022, 121000F. [CrossRef]

- Jianguo Xu, Weihua Yang, Cheng Wan, Jianxin Shen, Weakly supervised detection of central serous chorioretinopathy based on local binary patterns and discrete wavelet transform. Computers in Biology and Medicine 2020, 127, 104056. [CrossRef]

- Liu YY, Chen M, Ishikawa H, Wollstein G, Schuman JS, Rehg JM. Automated macular pathology diagnosis in retinal OCT images using multi-scale spatial pyramid and local binary patterns in texture and shape encoding. Med Image Anal. 2011, 15, 748–59. [CrossRef]

- Y. -W. Yu, C. -H. Lin, C. -K. Lu, J. -K. Wang and T. -L. Huang, "Distinct Feature Labeling Methods for SVM-Based AMD Automated Detector on 3D OCT Volumes," 2022 IEEE International Conference on Consumer Electronics (ICCE), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2022, pp. 1-5. [CrossRef]

- Md Akter Hussain, Alauddin Bhuiyan,Chi D. Luu,R. Theodore Smith,Robyn H. Guymer,Hiroshi Ishikawa,Joel S. Schuman,Kotagiri Ramamohanarao, Classification of healthy and diseased retina using SD-OCT imaging and Random Forest algorithm, PLOS ONE, June 4, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Anju Thomas, A. P. Sunija, Rigved Manoj, Rajiv Ramachandran, Srikkanth Ramachandran, P. Gopi Varun, P. Palanisamy, RPE layer detection and baseline estimation using statistical methods and randomization for classification of AMD from retinal OCT. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine 2021, 200, 105822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratul, P. Srinivasan, Leo A. Kim, Priyatham S. Mettu, Scott W. Cousins, Grant M. Comer, Joseph A. Izatt, and Sina Farsiu, "Fully automated detection of diabetic macular edema and dry age-related macular degeneration from optical coherence tomography images. Biomed. Opt. Express 2014, 5, 3568–3577. [Google Scholar]

- Mousavi, Elahe; Kafieh, Rahele; Rabbani, Hossein. Classification of dry age-related macular degeneration and diabetic macular oedema from optical coherence tomography images using dictionary learning. IET Image Processing 2020, 14, 1571–1579, IET Digital Library, https://digital-library.theiet.org/content/journals/10.1049/iet-ipr.2018.6186. [CrossRef]

- Yankui Sun, Shan Li, and Zhongyang Sun Fully automated macular pathology detection in retina optical coherence tomography images using sparse coding and dictionary learning. Journal of Biomedical Optics 2017, 22, 016012. [CrossRef]

- İsmail Kayadibi, Gür Emre Güraksın, Utku Köse, A Hybrid R-FTCNN based on principal component analysis for retinal disease detection from OCT images. Expert Systems with Applications 2023, 230, 120617, ISSN 0957–4174. [CrossRef]

- Shengyong Diao, Jinzhu Su, Changqing Yang, Weifang Zhu, Dehui Xiang, Xinjian Chen, Qing Peng, Fei Shi, Classification and segmentation of OCT images for age-related macular degeneration based on dual guidance networks. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2023, 84, 104810, ISSN 1746–8094. [CrossRef]

- Barua, Prabal Datta, Wai Yee Chan, Sengul Dogan, Mehmet Baygin, Turker Tuncer, Edward J. Ciaccio, Nazrul Islam, Kang Hao Cheong, Zakia Sultana Shahid, and U. Rajendra Acharya. Multilevel Deep Feature Generation Framework for Automated Detection of Retinal Abnormalities Using OCT Images. Entropy 2021, 23, 1651. [CrossRef]

- Ji, Qingge, Wenjie He, Jie Huang, and Yankui Sun. Efficient Deep Learning-Based Automated Pathology Identification in Retinal Optical Coherence Tomography Images. Algorithms 2018, 11, 88. [CrossRef]

- Alqudah, AM. AOCT-NET: a convolutional network automated classification of multiclass retinal diseases using spectral-domain optical coherence tomography images. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2020, 58, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leyuan Fang, Yuxuan Jin, Laifeng Huang, Siyu Guo, Guangzhe Zhao, Xiangdong Chen. Iterative fusion convolutional neural networks for classification of optical coherence tomography images. Journal of Visual Communication and Image Representation 2019, 59, 327–333. [CrossRef]

- Ranjitha Rajan, S.N. Kumar, IoT based optical coherence tomography retinal images classification using OCT Deep Net2. Measurement: Sensors 2023, 25, 100652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuji, T. , Hirose, Y., Fujimori, K. et al. Classification of optical coherence tomography images using a capsule network. BMC Ophthalmol 2020, 20, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bridge, J. , Harding, S.P., Zhao, Y., Zheng, Y. (2019). Dictionary Learning Informed Deep Neural Network with Application to OCT Images. In: Fu, H., Garvin, M., MacGillivray, T., Xu, Y., Zheng, Y. (eds) Ophthalmic Medical Image Analysis. OMIA 2019. Lecture Notes in Computer Science(), vol 11855. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Baharlouei, Zahra; Shaker, Fariba; Plonka, Gerlind; Rabbani, Hossein (2023). Application of Deep Dictionary Learning and Predefined Filters for Classification of Retinal Optical Coherence Tomography Images. Optica Open. Preprint. [CrossRef]

- X. Wang et al., "UD-MIL: Uncertainty-Driven Deep Multiple Instance Learning for OCT Image Classification. in IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics 2020, 24, 3431–3442. [CrossRef]

- Rasti R, Mehridehnavi A, Rabbani H, Hajizadeh F. , Automatic diagnosis of abnormal macula in retinal optical coherence tomography images using wavelet-based convolutional neural network features and random forests classifier. J Biomed Opt. 2018, 23, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- L. Fang, C. Wang, S. Li, H. Rabbani, X. Chen, and Z. Liu. Attention to Lesion: Lesion-Aware Convolutional Neural Network for Retinal Optical Coherence Tomography Image Classification. in IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging 2019, 38, 1959–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. S. Mishra, B. Mandal and N. B. Puhan. Multi-Level Dual-Attention Based CNN for Macular Optical Coherence Tomography Classification. in IEEE Signal Processing Letters 2019, 26, 1793–1797. [CrossRef]

- S. S. Mishra, B. Mandal and N. B. Puhan. Perturbed Composite Attention Model for Macular Optical Coherence Tomography Image Classification. in IEEE Transactions on Artificial Intelligence 2022, 3, 625–635. [CrossRef]

- Xiaoming Liu, Yingjie Bai, Jun Cao, Junping Yao, Ying Zhang, Man Wang, Joint disease classification and lesion segmentation via one-stage attention-based convolutional neural network in OCT images. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2022, 71, 103087, ISSN 1746–8094. [CrossRef]

- Huang X, Ai Z, Wang H, She C, Feng J, Wei Q, Hao B, Tao Y, Lu Y, Zeng F. GABNet: global attention block for retinal OCT disease classification. Front Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1143422. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- V. Das, E. Prabhakararao, S. Dandapat and P. K. Bora. B-Scan Attentive CNN for the Classification of Retinal Optical Coherence Tomography Volumes. in IEEE Signal Processing Letters 2020, 27, 1025–1029. [CrossRef]

- Abd Elaziz M, Mabrouk A, Dahou A, Chelloug SA. Medical Image Classification Utilizing Ensemble Learning and Levy Flight-Based Honey Badger Algorithm on 6G-Enabled Internet of Things. Comput Intell Neurosci. 2022, 2022, 5830766. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hassan B, Hassan T, Li B, Ahmed R, Hassan O. Deep Ensemble Learning Based Objective Grading of Macular Edema by Extracting Clinically Significant Findings from Fused Retinal Imaging Modalities. Sensors (Basel). 2019, 19, 2970. [CrossRef]

- Vineeta Das, Samarendra Dandapat, Prabin Kumar Bora, Multi-scale deep feature fusion for automated classification of macular pathologies from OCT images. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2019, 54, 101605. [CrossRef]

- A. Thomas et al., A novel multiscale and multipath convolutional neural network based age-related macular degeneration detection using OCT images. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine 2021, 209, 106294. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anju Thomas, Harikrishnan P. M., Adithya K. Krishna, Palanisamy P., Varun P. Gopi. A novel multiscale convolutional neural network based age-related macular degeneration detection using OCT images. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2021, 67, 102538. [CrossRef]

- Saman Sotoudeh-Paima, Ata Jodeiri, Fedra Hajizadeh, Hamid Soltanian-Zadeh, Multi-scale convolutional neural network for automated AMD classification using retinal OCT images. Computers in Biology and Medicine 2022, 144, 105368. [CrossRef]

- Akinniyi O, Rahman MM, Sandhu HS, El-Baz A, Khalifa F. Multi-Stage Classification of Retinal OCT Using Multi-Scale Ensemble Deep Architecture. Bioengineering (Basel). 2023, 10, 823. [CrossRef]

- R. Rasti, H. Rabbani, A. Mehridehnavi and F. Hajizadeh. Macular OCT Classification Using a Multi-Scale Convolutional Neural Network Ensemble. in IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging 2018, 37, 1024–1034. [CrossRef]

- V. Das, S. Dandapat and P. K. Bora. Automated Classification of Retinal OCT Images Using a Deep Multi-Scale Fusion CNN. in IEEE Sensors Journal 2021, 21, 23256–23265. [CrossRef]

- Y. Rong et al., "Surrogate-Assisted Retinal OCT Image Classification Based on Convolutional Neural Networks. in IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics 2019, 23, 253–263. [CrossRef]

- V. Das, S. Dandapat and P. K. Bora. A Data-Efficient Approach for Automated Classification of OCT Images Using Generative Adversarial Network. in IEEE Sensors Letters 2020, 4, 7000304. [CrossRef]

- V. Das, S. Dandapat and P. K. Bora, "Unsupervised Super-Resolution of OCT Images Using Generative Adversarial Network for Improved Age-Related Macular Degeneration Diagnosis. in IEEE Sensors Journal 2020, 20, 8746–8756. [CrossRef]

- Z. Ma, Q Xie; P. Xie; F. Fan, X Gao, J. Zhu, HCTNet: A Hybrid ConvNet-Transformer Network for Retinal Optical Coherence Tomography Image Classification. Biosensors 2022, 12, 542. [CrossRef]

- He, J. , Wang, J. , Han, Z. et al. An interpretable transformer network for the retinal disease classification using optical coherence tomography. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 3637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A. Playout, R. Duval, M. C. Boucher, F. Cheriet. Focused Attention in Transformers for interpretable classification of retinal images. Medical Image Analysis 2022, 82, 102608, ISSN 1361–8415. [CrossRef]

- Cai L, Wen C, Jiang J, et al, Classification of diabetic maculopathy based on optical coherence tomography images using a Vision Transformer model. BMJ Open Ophthalmology 2023, 8, e001423. [CrossRef]

- Badr Ait Hammou, Fares Antaki, Marie-Carole Boucher, Renaud Duval. MBT: Model-Based Transformer for retinal optical coherence tomography image and video multi-classification. International Journal of Medical Informatics 2023, 178, 105178. [CrossRef]

- Junyong Shen, Yan Hu, Xiaoqing Zhang, Yan Gong, Ryo Kawasaki, Jiang Liu, Structure-Oriented Transformer for retinal diseases grading from OCT images. Computers in Biology and Medicine 2023, 152, 106445, ISSN 0010–4825. [CrossRef]

- H. Wang et al. OCTFormer: An Efficient Hierarchical Transformer Network Specialized for Retinal Optical Coherence Tomography Image Recognition. in IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2023, 72, 2532217. [CrossRef]

- Hemalakshmi, G.R. , Murugappan, M. , Sikkandar, M.Y. et al. Automated retinal disease classification using hybrid transformer model (SViT) using optical coherence tomography images. Neural Comput & Applic 2024, 36, 9171–9188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, P.; Sathi, K.A.; Hossain, M.A.; Dewan, M.A.A. Conv-ViT: A Convolution and Vision Transformer-Based Hybrid Feature Extraction Method for Retinal Disease Detection. J. Imaging 2023, 9, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang Yu, Hongqing Zhu, Transformer-based cross-modal multi-contrast network for ophthalmic diseases diagnosis. Biocybernetics and Biomedical Engineering 2023, 43, 507–527, ISSN 0208. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Han, Y.; Yang, X. Multi-Fundus Diseases Classification Using Retinal Optical Coherence Tomography Images with Swin Transformer V2. J. Imaging 2023, 9, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huajie Wen, Jian Zhao, Shaohua Xiang, Lin Lin, Chengjian Liu, Tao Wang, Lin An, Lixin Liang, Bingding Huang, Towards more efficient ophthalmic disease classification and lesion location via convolution transformer. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine 2022, 220, 106832, ISSN 0169–2607. [CrossRef]

- Mohammad Mahdi Azizi, Setareh Abhari, Hedieh Sajedi, Stitched vision transformer for age-related macular degeneration detection using retinal optical coherence tomography images, June 5, 2024, PLOS ONE. [CrossRef]

- Mona Ashtari-Majlan, Mohammad Mahdi Dehshibi, David Masip, Spatial-aware Transformer-GRU Framework for Enhanced Glaucoma Diagnosis from 3D OCT Imaging, arXiv, March 2024.

- Zhencun Jiang, Lingyang Wang, Qixin Wu, Yilei Shao, Meixiao Shen, Wenping Jiang, and Cuixia Dai. Computer-aided diagnosis of retinopathy based on vision transformer. Journal of Innovative Optical Health Sciences 2022, 15, 2250009.

- Yuka Kihara, Mengxi Shen, Yingying Shi, Xiaoshuang Jiang, Liang Wang, Rita Laiginhas, Cancan Lyu, Jin Yang, Jeremy Liu, Rosalyn Morin, Randy Lu, Hironobu Fujiyoshi, William J. Feuer, Giovanni Gregori, Philip J. Rosenfeld, Aaron Y. Lee. Detection of Nonexudative Macular Neovascularization on Structural OCT Images Using Vision Transformers. Ophthalmology Science 2022, 2, 100197. [CrossRef]

- Oghbaie, M. , Araújo, T., Emre, T., Schmidt-Erfurth, U., Bogunović, H. (2023). Transformer-Based End-to-End Classification of Variable-Length Volumetric Data. In: Greenspan, H., et al. Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2023. MICCAI 2023. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 14225. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Zenan Zhou, Chen Niu, Huanhuan Yu, Jiaqing Zhao, Yuchen Wang, and Cuixia Dai "Diagnosis of retinal diseases using the vision transformer model based on optical coherence tomography images. Proc. SPIE 12601, SPIE-CLP Conference on Advanced Photonics 2022, 1260102 (28 March 2023). [CrossRef]

- A. Liew, S. Agaian, L. Zhao "Mitigation of adversarial noise attacks on skin cancer detection via ordered statistics binary local features. Proc. SPIE 12526, Multimodal Image Exploitation and Learning 2023, 2023, 125260O. [CrossRef]

- Alex Liew, Sos S. Agaian, and Liang Zhao "Enhancing the resilience of wireless capsule endoscopy imaging against adversarial contrast reduction using color quaternion modulus and phase patterns. Proc. SPIE 13033, Multimodal Image Exploitation and Learning 2024, 130330I (7 June 2024). [CrossRef]

- Magdalini Paschali, Sailesh Conjeti, Fernando Navarro, Nassir Navab, Generalizability vs. Robustness: Adversarial Examples for Medical Imaging. arXiv:1804.00504v1.

- Puttagunta, M.K. , Ravi, S. & Nelson Kennedy Babu, C. Adversarial examples: attacks and defences on medical deep learning systems. Multimed Tools Appl 2023, 82, 33773–33809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xingjun Ma, Yuhao Niu, Lin Gu, Yisen Wang, Yitian Zhao, James Bailey, Feng Lu, Understanding adversarial attacks on deep learning based medical image analysis systems, Pattern Recognition 2021, 110, 107332, ISSN 0031-3203. [CrossRef]

- Finlayson SG, Bowers JD, Ito J, Zittrain JL, Beam L, Kohane IS. Adversarial attacks on medical machine learning emerging vulnerabilities demand new conversations. Sci (80- ) 2019, 363, 1287–1290. [CrossRef]

- Samuel, G. Finlayson et al., Adversarial attacks on medical machine learning. Science 2019, 363, 1287–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirano, H.; Minagi, A.; Takemoto, K. Universal adversarial attacks on deep neural networks for medical image classification. BMC Med Imaging 2021, 21, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang Chen, Jian Wang, Han Liu, Wentao Kong, Zhe Zhao, Longfei Ma, Hongen Liao, Daoqiang Zhang. Frequency constraint-based adversarial attack on deep neural networks for medical image classification. Computers in Biology and Medicine 2023, 164, 107248. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laith Alzubaidi, Khamael AL–Dulaimi, Huda Abdul-Hussain Obeed, Ahmed Saihood, Mohammed A. Fadhel, Sabah Abdulazeez Jebur, Yubo Chen, A.S. Albahri, Jose Santamaría, Ashish Gupta, Yuantong Gu, MEFF – A model ensemble feature fusion approach for tackling adversarial attacks in medical imaging. Intelligent Systems with Applications 2024, 22, 200355. [CrossRef]

- Xiaodong Yue, Zhicheng Dong, Yufei Chen, Shaorong Xie, Evidential dissonance measure in robust multi-view classification to resist adversarial attack, Information Fusion 2025, 113, 102605, ISSN 1566-2535. [CrossRef]

- Shancheng Jiang, Zehui Wu, Haiqiong Yang, Kun Xiang, Weiping Ding, Zhen-Song Chen, A prior knowledge-guided distributionally robust optimization-based adversarial training strategy for medical image classification. Information Sciences 2024, 673, 120705. [CrossRef]

- Yi Li, Huahong Zhang, Camilo Bermudez, Yifan Chen, Bennett A. Landman, Yevgeniy Vorobeychik, Anatomical context protects deep learning from adversarial perturbations in medical imaging. Neurocomputing 2020, 379, 370–378. [CrossRef]

- Jacob Devlin, Ming-Wei Chang, Kenton Lee, Kristina Toutanova, BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding, arXiv, Oct 2018 – 99.

- Hugo Touvron, Thibaut Lavril, Gautier Izacard, Xavier Martinet, Marie-Anne Lachaux, Timothée Lacroix, Baptiste Rozière, Naman Goyal, Eric Hambro, Faisal Azhar, Aurelien Rodriguez, Armand Joulin, Edouard Grave, Guillaume Lample, LLaMA: Open and Efficient Foundation Language Models, arXiv, Feb 2023.

- Li, J. , Guan, Z., Wang, J. et al. Integrated image-based deep learning and language models for primary diabetes care. Nat Med (2024). [CrossRef]

- Pusheng Xu, Xiaolan Chen, Ziwei Zhao, Danli Shi, Unveiling the Clinical Incapabilities: A Benchmarking Study of GPT-4V(ision) for Ophthalmic Multimodal Image Analysis, medRxiv 2023.11.27.23299056.

- Liu X, Wu J, Shao A, Shen W, Ye P, Wang Y, Ye J, Jin K, Yang J. Uncovering Language Disparity of ChatGPT on Retinal Vascular Disease Classification: Cross-Sectional Study. J Med Internet Res 2024, 26, e51926, URL: https://www.jmir.org/2024/1/e51926. [CrossRef]

- Dossantos J, An J, Javan R. Eyes on AI: ChatGPT’s Transformative Potential Impact on Ophthalmology. Cureus. 2023, 15, e40765. [CrossRef]

- Nikdel, Mojgan MD; Ghadimi, Hadi MD; Suh, Donny W. MD, FACS; Tavakoli, Mehdi MD, FICO. Accuracy of the Image Interpretation Capability of ChatGPT-4 Vision in Analysis of Hess Screen and Visual Field Abnormalities. Journal of Neuro-Ophthalmology.

| Feature Comparison | [1] | [2] | [3] | [4] | [5] | [6] | [7] | [8] | [9] | [10] | [11] | [12] | OUR |

| Covers both DL and Hand-Crafted Features | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ✓ | - | ✓ |

| In-depth discussion on Hand-Craft Features | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ✓ | ✓ | - | - | - | ✓ |

| In-depth discussion on CNNs and its various types | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| In-depth discussion on Vision Transformers | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ✓ | - | ✓ |

| In-depth comparisons between types of CNNs | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Includes comparative analysis of DL and HCF | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ✓ |

| Includes in-depth discussion of ocular disorders | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ✓ | ✓ | - |

| Discusses latest advancements | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | - | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Review of multiple OCT datasets | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ✓ | - | ✓ |

| Reviews specific OCT imaging technique | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Identifies gaps in current research | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Suggest future research into Adversarial Attacks | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ✓ |

| Suggest future research in LLMs | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ✓ |

| Dataset | Classes and Counts | Institutional Source or website |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 15 DME volume images , 15 AMD volume images, and 15 Normal volume images | Duke University, Harvard University, and University of Michigan |

| 2 | 48 AMD volume images , 50 DME images, 50 normal images | Noor Eye Hospital in Tehran (NEH) |

| 3 | 120 Normal volume images, 160 Drusen volume images, and 161 CNV volume images, 16,822 3D OCT images Total | Noor Eye Hospital in Tehran (NEH) |

| 4* | 37,206 CNV 2D images, 11,349 DME images 8,617 Drusen 2D images, 51,140 Normal 2D images |

University of California San Diego, Guangzhou Women and Children’s Medical Center |

| 4 | Trimmed Down version of 4* referred to as OCT2017 37,455 CNV 2D images, 11,598 DME 2D images, 8,866 drusens 2D images, and 26,565 normal 2D images, total of 84,484 OCT images |

University of California San Diego, Guangzhou Women and Children’s Medical Center |

| 5 | 269 Intermediate AMD volume images and 115 Normal Volume images | Boards of from Devers Eye Institute, Duke Eye, Center, Emory Eye Center, and National Eye Institute |

| 6 | 3000 AMD images, 3000 CNV images, 3000 DME images, 3000 MH images, 3000 DR images, 3000 CSR images, 24,000 total 2D OCT images | Boards of from Devers Eye Institute, Duke Eye, Center, Emory Eye Center, and National Eye Institute |

| 7 | Normal Macular (316), Macular Edema (261), Macular Hole (297), AMD (284) | UPMC Eye Center, Eye and Ear Institute, Ophthalmology and Visual Science Research Center |

| 7* | 3319 OCT images Total, 1254 early DME, 991 advanced DME, 672 severe DME and 402 atrophic maculopathy |

Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University |

| 8 | 16 DME volume images & 16 normal volume images | Singapore Eye Research Institute (SERI) |

| 9 | Macular holes, MH (102), AMD (55), Diabetic retinopathy, DR (107), and Normal retinal images (206) | Cirrus HD-OCT machine (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Inc., Dublin, CA) at Sankara Nethralaya (SN) Eye Hospital in Chennai, India |

| 10 | 1395 samples (697 glaucoma and 698 non-glaucoma) | Zhongshan Ophthalmic Center, Sun Yat-sen University |

| Refs | Method | Method’s Descriptions | Performance Summary |

|---|---|---|---|

| [24] | LBP Slice-Sum & SVM | Low-complexity feature vector slice-sum with SVM classifier |

D5Method: Accuracy (%), Sensitivity (%), LBP-RIU2: 90.80, 93.85, 87.72 |

| [25] | 3D-LBP | Global descriptors extracted from 2D feature image for LBP and from the 3D volume OCT image. Features are fed into classifier for predictions |

D9,VACC% F1% SE% SP% Global-LBP: 81.2 78.5 68.7 93.7 Local-LBP: 75.0 75.0 75.0 75.0 Local-LBP-TOP: 75.0 73.3 68.7 81.2 |

| [26] | HOG + LBP | Histogram of Oriented Gradients (HOG) and LBP features are extracted combined. These features are fed into linear SVM Classifier |

D9,VSens, Spec, Prec, F1, Acc. HOG: 0.69 0.94 0.91 0.81 0.78 HOG+PCA: 0.75 0.87 0.85 0.80 0.81 |

| [27] | Multi-kernel Wiener local binary patterns (MKW-LBP) | Image denoised using wiener filter. MKW-LBP descriptor calculates the mean and variance of neighboring pixels. SVMs, Adaboost, and Random Forest are used for classifications. |

D1Kernel / Classifier: Prec. (%), Sen. (%), spec. (%), Acc (%), 3 × 3 / SVM-Poly: 97.84, 97.48, 98.89, 97.86 3 × 5 / SVM-Poly: 98.84, 98.59, 99.41, 98.85 5 × 5 / SVM-Poly: 98.19, 98.05, 99.15, 98.33 |

| [28] | Multi-Size Kernels Echo-Weighted Median Patterns (MSK-EMP) | Image denoised using median filter and is flattened. MSKξMP is a variant of LBP which selects a weighted median pixel in a kernel and is applied to preprocessed image. Also employs Singular Value Decomposition and Neighborhood Component Analysis based weighted feature selection method. | Classifier: prec., sens., spec, acc D1SVM-Poly: 0.9976, 0.9971, 0.9989, 0.9978 D2SVM-Poly: 0.9662, 0.9663, 0.9833, 0.9669 D3SVM: RBF: 0.8952, 0.8758, 0.9395, 0.8887 |

| [29] | Alpha Mean trim Local Binary Patterns (AMT-LBP) | Image denoised using median filter and is flattened. AMT-LBP is a variant of LBP which encodes by averages all pixel values in a kernel omitting highest and lowest values. SVM is employed for classification |

D1SVM-Poly: tr1=0, tr2=2 || SVM-Poly: tr1=2, tr2=0 || SVM-Poly: tr1=2, tr2=2 precision 0.9796 || 0.9846 || 0.9710 sensitivity 0.9751 || 0.9813 || 0.9654 specificity 0.9887 || 0.9920 || 0.9854 accuracy 0.9774 || 0.9836 || 0.9700 F-measure 0.9773 || 0.9829 || 0.9680 AUC 0.9740 || 0.9802 || 0.9697 |

| [30] | H-F-V&H-LBP + T |

Combines discrete wavelet transform (DWT) image decomposition and LBP based texture feature extraction, and multi-instance learning (MIL). LBP is chosen for its ability to handle low contrast and low-quality images. | D3,BAcc.: 99.58% |

| [32] | Slice-chain labeling Slice-threshold labeling |

OCT B-scans of a volume image are employed where each slice is labeled and threshold, which extracts features. |

D3,BD5 – Acc.: 92.50% D3,BD5 – Acc.: 96.36% |

| [33] | Retinal thickness Method | The thickness of the retinal layers is measured, and each OCT image is classified according to the thickness. |

D3,BD1 – Acc.: 97.33%, Sen. 94.67%, Spec. 100%, F1: 97.22%, AUC: 0.99 |

| [34] | RPE layer detection and baseline estimation using statistical methods | Pixel grouping / iterative elimination, guided by layer intensities are employed to detect the RPE layer and is enhanced by randomization techniques. |

D1,VAMD Acc: 100% Normal Acc: 93.3% DME Acc: 96.6% |

| [35] | Histogram of Oriented Gradients (HOG) descriptors and SVM | Noise removal using sparsity-based block matching and 3D-filtering. HOG and SVM are employed for classification of AMD and DME. |

D1,VAMD Acc: 100% Normal Acc: 86.67% DME Acc: 100% |

| [36] | Dictionary Learning (COPAR), (FDDL), and (LRSDL) | Image denoising, flattening the retinal curvature, cropping, extracting HOG features, and classifying using a dictionary learning approach. |

D1,VD1 – AMD Acc: 100% Normal Acc: 100% DME Acc: 95.13% |

| [37] | Sparse Coding Dictionary Learning | Preprocessed retina aligning and image cropping, Then, image partitioning, feature extracting, dictionary training with sparse coding is applied to the OCT images. Linear SVM is utilized to classify images. |

D1,VD1 – AMD Acc: 100% Normal Acc: 100% DME Acc: 95.13% |

| Refs | Method | Method’s Description | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| [38] | Hybrid Retinal Fine Tuned Convolutional Neural Network (R-FTCNN) | R-FTCNN is employed with Principal Component Analysis (PCA) used concurrently within this methodology. PCA converts the fully connected layers of the R-FTCNN into principal components, and the Softmax function is then applied to these components to create a new classification model. |

D1FC1 + PCA: Acc: 1.0000, Sen.: 1.0000, Spec.: 1.0000, Prec.: 1.0000, F1: 1.0000, AUC: 1.0000 D4FC1 + PCA: Acc: 0.9970, Sen.: 0.9970, Spec.: 0.9990, Prec.: 0.9970, F1: 0.9970, AUC: 0.99999 (61mil-parameters) |

| [39] | Complementary Mask Guided Convolutional Neural Network (CM-CNN) | CM-CNN classifies OCT B-scans by using masks generated from a segmentation task. A Class Activation Map Guided UNet (CAM-UNet) segments drusen and CNV lesions, utilizing CAM output from the CM-CNN |

D3AUC, Sen, Spe, Class Acc D3CNV: 0.9988, 0.9960, 0.9680, 0.9773 D3Drusen 0.9874, 0.9120, 0.9980, 0.9693 D3Normal 0.9999, 1, 0.9880, 0.9920 D3Overall Acc: 0.9693 |

| [40] | CNN iterative ReliefF + SVM |

DeepOCT employs multilevel feature extraction using 18 pre-trained networks combined with tent maximal pooling, followed by feature selection using ReliefF. |

D1Acc:1.00, Pre:1.00, F1:1.00, Rec:1.00, MCC:1.00 4**Acc: 0.9730, Pre: 0.9732, F1: 0.9730, Rec: 0.9730, MCC: 0.9641 |

| [41] | Inception V3 – Custom Fully Connected layers | Eliminating the final layers of a pre-trained Inception V3 model and using the remaining part as a fixed feature extractor. | D1,VAMD 15/15 = 100%, DME 15/15 = 100%, NOR 15/15 = 100% |

| [42] | AOCT-NET | Utilizes a softmax classifier to distinguish between five retinal conditions: AMD, CNV, DME, drusen, and normal cases |

4+5AMD: 100%, 100%; CNV: 98.64%, 100%; DME: 99.2%, 0.96; Drusen: 97.84%, 0.92; Normal: 98.56%, 0.97 |

| [43] | Iterative fusion convolutional neural network (IFCNN) | Employs iterative fusion for merging features from the current convolutional layer with those from all preceding layers in the network. |

D4Sensitivity., Specificity, Accuracy Drusen 76.8 ± 7.2, 94.9 ± 1.9, 93 ± 1.7 87.3 ± 2.2; CNV 87.9 ± 4.3, 96 ± 1.7, 92.4 ± 1.3, DME 81.9 ± 6.8, 96.3 ± 2, 94.4 ± 1, Normal 92.2 ± 4.7 96 ± 1.6 94.8 ± 1.2. |

| [44] | IoT OCT Deep Net2 | Expands from 30 to 50 layers and features a dense architecture with three recurrent modules |

D4Precision, Recall, F1-Score, Acc. 0.97 Normal:0.99, 0.93, 0.96, CNV: 0.95, 0.98, 0.98, DME: 0.96, 0.99, 0.98, Drusen: 0.99, 1.00, 0.99 |

| [45] | Capsule Network | Composed of neuron groups representing different attributes, utilizes vectors to learn positional relationships between image features. |

D4Sensitivity, Specificity, Precision, F1 CNV: 1.0, 0.9947, 1.0, 1.0, DME: 0.992, 0.9973, 0.992, 0.992, Drusen: 0.992, 0.9973, 0.992, 0.992, Normal: 1.0, 1.0, 1.0, 1.0 |

| [46] | Dictionary Learning Informed Deep Neural Network (DLI-DNN) | Downsampling by utilizing DAISY descriptors and Improved Fisher kernels to extract features from OCT images. | D4Accuracy: 97.2%, AUC: 0984, Sensitivity: 97.1%, Specificity: 99.1% |

| [47] | S-DDL – 4 classes Wavelet Scattering Transform (WST) – 5 classes |

S-DDL addresses the vanishing gradient problem and shortens training time. WST employs the Wavelet Scattering Transform using predefined filters within the network layers |

D9CSR-Acc: 0.7609, Sen: 0.2381, Spec: 0.9155 D9AMD-Acc: 0.9186, Sens: 0.8182, Spec: 0.9333 D9MH-Acc: 0.8, Sens: 0.7, Spec: 0.8308 D9NO-Acc: 0.9326, Sens: 0.9512, Spec: 0.9167 D9AMD-Acc: , Sens: 1.0, Spec: 0.9216 D9CSR-Acc: 0.9057, Sen: 0.7273, Spec: 0.9524 D9DR-Acc: 0.9038, Sens: 0.8889,Spec: 0.9060 D9MH-Acc: 0.9038, Sens: 0.6923, Spec: 0.9744 D9NO-Acc: 0.9792, Sens: 0.9545, Spec: 1.0, OA: 82.5% |

| [48] | Multiple instance learning (UD-MIL) | Employs instance-level classifier for iteratively deep multiple instance learning, where this enables the classifier. Then a recurrent neural network (RNN) utilizes the features from those instances to make the final predictions. |

D5Accuracy, F1, AUC μ=0.1, 0.971 ± 0.010, 0.980 ± 0.007, 0.955 ± 0.020 μ=0.2, 0.979 ± 0.018, 0.986 ± 0.012, 0.970 ± 0.027 μ=0.3, 0.979 ± 0.018, 0.986 ± 0.012, 0.970 ± 0.027 μ=0.4, 0.979 ± 0.011, 0.986 ± 0.007, 0.975 ± 0.020 μ=0.5, 0.979 ± 0.011, 0.986 ± 0.007, 0.975 ± 0.020 |

| Refs. | Method | Method’s Descriptions | Results | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [50] | Lesion-aware convolutional neural network (LACNN) | LACNN concentrates on local lesion-specific regions by utilizing a lesion detection network to generate a soft attention map over the entire OCT image. | D4 | Acc | Prec | |||||

| Drusen | 93.6 ± 1.4 | 70.0 ± 5.7 | ||||||||

| CNV | 92.7 ± 1.5 | 93.5 ± 1.3 | ||||||||

| DME | 96.6 ± 0.2 | 86.4 ± 1.6 | ||||||||

| Normal | 97.4 ± 0.2 | 94.8 ± 1.1 | ||||||||

|

D4Overall ACC: 90.1 ± 1.4, Overall Sensitivity: 86.8 ± 1.3 D2Overall Sensitivity: 99.33 ± 1.49, Overall PR: 99.39 ± 1.36, F1, 99.33 ± 1.49, AUC: 99.40 ± 1.34 | ||||||||||

| [51] | Multi-Level Dual-Attention Based CNN (MLDA-CNN) | A dual-attention mechanism is applied at multiple levels a CNN and integrates multi-level feature-based attention emphasizes high-entropy regions within the finer features. |

D1Acc: 95.57, Prec: 95.29, Recall: 96.04, F1: 0.996 D2Acc: 99.62 (+/- 0.42), Prec: 99.60 (+/- 0.39), Recall: 99.62 (+/- 0.42), F1: 0.996, AUC: 0.9997 |

|||||||

| [52] | Multilevel Perturbed Spatial Attention (MPSA) & Multidimension Attention (MDA) | MPSA emphasizes key regions in input images and intermediate network layers by perturbating to the attention layers. MDA captures the information across different channels of the extracted feature maps. |

D1Acc: 100%, Prec: 100%, Recall: 100% D2Acc: 99.79 (+/- 0.43), Prec: 99.80 (+/- 0.41), Recall: 99.78 (+/- 0.43) D4Acc: 92.62 (+/- 1.69), Prec: 89.96 (+/- 3.16), Recall: 88.53 (+/- 3.26) |

|||||||

| [53] | One-stage attention-based framework weakly supervised lesion segmentation | One-stage attention-based classification and segmentation, where the classification network generates a heatmap through Grad-CAM and integrates the proposed attention block. | D4 | Acc | SE | Spec | ||||

| CNV | 93.6 ± 1.9 | 90.1 ± 3.8 | 96.5 ± 1.4 | |||||||

| DME | 94.8 ± 1.2 | 86.5 ± 1.5 | 96.4 ± 2.1 | |||||||

| DRUSEN | 94.6 ± 1.4 | 71.5 ± 4.8 | 96.9 ± 1.2 | |||||||

| NORMAL | 97.1 ± 1.0 | 96.3 ± 1.5 | 98.9 ± 0.3 | |||||||

| D4OA: 90.9 ± 1.0, OS: 86.3 ± 1.8, OP: 85.5 ± 1.6 | ||||||||||

| [54] | Efficient Global Attention Block (GAB) and Inception | GAB generates an attention map across three dimensions for any intermediate feature map and computes adaptive feature weights by multiplying the attention map with the input feature map. |

D4*Accuracy: 0.914, Recall: 0.9141, Specificity: 0.9723, F1: 0.915, AUC: 0.9914 |

|||||||

| [55] | B-scan attentive convolutional neural network (BACNN) | BACNN employs a self-attention module to aggregate extracted features based on their clinical significance, producing high-level feature vector for diagnosis. | D1Sen: 97.76 ± 2.07, Spec: 95.61 ± 4.35, Acc: 97.12 ± 2.78, | |||||||

| D2 | Sens. | Spec. | Acc. | |||||||

| AMD | 92.0 ± 4.4 | 95.0 ± 0.1 | 93.2 ± 2.7 | |||||||

| DME | 100.0 ± 0.0 | 98.9 ± 2.4 | 99.3 ± 1.5 | |||||||

| Normal | 87.8 ± 4.3 | 93.2 ± 2.3 | 92.2 ± 2.3 | |||||||

| [56] | 6G-enabled IoMT method – MobileNetV3 | Leverages transfer learning for feature extraction and optimized through feature selection using Hunger Games search algorithm. | D4 | Acc. | Recall | Prec | ||||

| SVM | 99.69 | 99.69 | 99.69 | |||||||

| XGB | 99.38 | 99.38 | 99.4 | |||||||

| KNN | 99.59 | 99.59 | 99.59 | |||||||

| RF | 99.38 | 99.38 | 99.4 | |||||||

| [57] | Deep Ensemble CNN + SVM, Naïve Bayes, Artificial Neural Network | A secondary layer within the CNN model to extract key feature descriptors, where they are subsequently concatenated and fed into a supervised hybrid classifier SVM and naïve Bayes models |

D4Sensivity, Specificity, Accuracy ANN: 0.96, 0.90, 0.93 || SVM: 0.94, 0.91, 0.91 NB: 0.93, 0.90, 0.91 || Ensemble: 0.97, 0.92, 0.94 |

|||||||

| [58] | Multi-scale deep feature fusion (MDFF) CNN | MDFF technique captures inter-scale variations in the images, providing the classifier with discriminative information | D4 | Sens. | Spec. | Acc. | ||||

| CNV | 96.6 | 98.73 | 97.78 | |||||||

| DME | 94.14 | 98.97 | 98.33 | |||||||

| DR | 90.49 | 98.32 | 97.52 | |||||||

| NO | 96.9 | 89.26 | 97.85 | |||||||

| [59] | Multiscale and multipath CNN with six convolutional layers | MDFF captures variations across different scales and are fed into a classifier | Precision | Recall | Accu. | |||||

| D1-2C | 0.969 | 0.967 | 0.9666 | |||||||

| D2-2C | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.9897 | |||||||

| D4-2C | 0.998 | 0.998 | 0.9978 | |||||||

| [60] | Multiscale CNN with seven convolutional layers | The architecture consists of a multiscale CNN with seven convolutional layers allowing for the generation of numerous local structures with various filter sizes | Precision Recall F1-score Accuracy AUC D1-2C 0.9687, 0.9666, 0.9666, 0.9667, 1.0000 D2-2C 0.9803, 0.9795, 0.9795, 0.9795, 0.9816 D4-2C 0.9973, 0.9973, 0.9973, 0.9973, 0.9999 D9-2C 0.9810 0.9808 0.9809 0.9808 0.9971 |

|||||||

| [61] | Multi-scale CNN based on the feature pyramid network | Combines a feature pyramid network (FPN) and by utilizing multi-scale receptive fields providing end-to-end training | Accuracy (%) Sensitivity (%) Specificity (%) D2FPN-VGG16: 92.0 ± 1.6, 91.8 ± 1.7, 95.8 ± 0.9 D2FPN-ResNet50: 90.1 ± 2.9, 89.8 ± 2.8, 94.8 ± 1.4 D2FPN-DenseNet: 90.9 ± 1.4, 90.5 ± 1.9, 95.2 ± 0.7 D2FPN-EfficientNetB0: 87.8 ± 1.3, 86.6 ± 1.8, 93.3 ± 0.8 D4FPN-VGG16: 98.4, 100, 97.4 |

|||||||

| [62] | Multi-scale (pyramidal) feature ensemble architecture (MSPE) | A multi-scale feature ensemble architecture employing a scale-adaptive neural network generates multi-scale inputs for feature extraction and ensemble learning. |

D1Acc= 99.69%, Sen= 99.71%, Spec.= 99.87% D4Accy=97.79%, Sen=95.55%, Spec.=99.72% |

|||||||

| [63] | Multi-scale convolutional mixture of expert (MCME) ensemble model | MCME model utilizes a cost function for feature learning by applying CNNs at multiple scales. Maximizing a likelihood function for the training dataset and ground truth using a Gaussian mixture model. |

D2Precision: 99.39 ± 1.21, Recall: 99.36 ± 1.33, F1: 99.34 ± 1.34, AUC: 0.998 |

|||||||

| [64] | Deep Multi-scale Fusion CNN (DMF-CNN) | DMF-CNN uses multiple CNNs with varying receptive fields to extract scale-specific features which are then extract cross-scale features. Additionally, a joint scale-specific and cross-scale multi-loss optimization strategy is employed. |

D2Sensitivity (%), Precision (%), F1 Score, OS, OP/OF1 AMD: 99.62 ± 0.27, 99.54 ± 0.17, 99.58 ± 0.16, 99.58 ± 0.23 DME: 99.45 ± 0.59, 99.45 ± 0.38, 99.45 ± 0.35, 99.59 ± 0.20 Normal: 99.68 ± 0.22, 99.75 ± 0.41, 99.71 ± 0.20, 99.60 ± 0.22 OA: 99.60 ± 0.21, AUC: 0.997 ± 0.002 D4Sensitivity (%), Precision (%), F1 Score CNV: 97.33 ± 1.05, 97.05 ± 1.19, 97.18 ± 0.32 DME: 93.22 ± 3.22, 96.26 ± 2.17, 94.65 ± 1.09 Drusen: 89.29 ± 3.59, 87.73 ± 3.84, 88.34 ± 1.27 Normal: 97.62 ± 1.11, 97.49 ± 1.30, 97.55 ± 0.49, OS/OP/OF1/OA: 94.37 ± 1.16, 94.64 ± 0.90, 94.43 ± 0.59, 96.03 ± 0.43 |

|||||||

| [65] | Surrogate-assisted CNN | Denoising, thresholding and morphological dilation are performed on images to create masks, which produce surrogate images for training the CNN model. |

D1Denoised: Acc: 95.09%, Sen. 96.39%, Spec: 93.60% D1Surrogate: Acc: 95.09%, Sen. 96.39%, Spec: 93.60% |

|||||||

| [66] | CNN and Semi-supervised GAN | D2 | Sen (%) | Spec (%) | Acc (%) | |||||

| AMD | 98.38 ± 0.69 | 97.79 ± 0.68 | 97.98 ± 0.61 | |||||||

| DME | 96.96 ± 1.32 | 99.23 ± 0.36 | 98.61 ± 0.49 | |||||||

| Normal | 96.96 ± 0.73 | 99.12 ± 0.64 | 98.26 ± 0.67 | |||||||

| OS/OSp/OA: 97.43 ± 0.68, 98.71 ± 0.34, 97.43 ± 0.66 | ||||||||||

| Refs. | Method | Method’s Descriptions | Results | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [68] | Hybrid ConvNet-Transformer network (HCTNet) | HCT-Net employs feature extraction modules via residual dense block. Next, two parallel branches, a Transformer and ConvNet are utilized to capture both global and local contexts in the OCT images. A feature fusion module with an adaptive reweighting mechanism integrates these global and local features. | D1 | Acc. (%) | Sen. (%) | Prec. (%) | |||

| AMD | 95.94 | 82.6 | 95.08 | ||||||

| DME | 86.61 | 80.22 | 85.29 | ||||||

| Normal | 89.81 | 93.39 | 85.22 | ||||||

| OA: 86.18%, OS: 85.40%, OP: 88.53% | |||||||||

| D4 | Acc (%) | Sen. (%) | Prec. (%) | ||||||

| CNV | 94.6 | 92.23 | 95.53 | ||||||

| DME | 96.14 | 87.96 | 84.42 | ||||||

| Drusen | 95.54 | 77.36 | 79.00 | ||||||

| Normal | 96.84 | 96.73 | 93.5 | ||||||

| OA: 91.56%, OS: 88.57%, OP: 88.11% | |||||||||

| [69] | Interpretable Swin-Poly Transformer network | Swin-Poly Transformer shifts window partitions and connects adjacent non-overlapping windows from the previous layer, allowing it to flexibly capture multi-scale features. The model refines cross-entropy by adjusting the importance of polynomial bases, thereby improving the accuracy of retinal OCT image classification. | D4 | Acc. | Prec. | Recall | |||

| CNV | 1.0000 | 0.9960 | 1.0000 | ||||||

| DME | 0.9960 | 1.0000 | 0.9960 | ||||||

| Drusen | 1.0000 | 0.9960 | 1.0000 | ||||||

| Normal | 0.9960 | 1.0000 | 0.9960 | ||||||

| Ave. | 0.9980 | 0.9980 | 0.9980 | ||||||

| D6 | Acc. | Prec. | Recall | ||||||

| AMD | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | ||||||

| CNV | 0.9489 | 0.9389 | 0.9571 | ||||||

| CSR | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | ||||||

| DME | 0.9439 | 0.9512 | 0.9457 | ||||||

| DR | 1.0000 | 0.9972 | 1.0000 | ||||||

| Drusen | 0.9200 | 0.9580 | 0.9114 | ||||||

| MH | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9971 | ||||||

| Normal | 0.9563 | 0.9254 | 0.9571 | ||||||

| Ave. | 0.9711 | 0.9713 | 0.9711 | ||||||

| [70] | Focused Attention Transformer | Focused Attention employs iterative conditional patch resampling to produce interpretable predictions through high-resolution attribution maps. | D4* | Acc. (%) | Spec. (%) | Recall (%) | |||

| T2T-ViT_14 | 94.40 | 98.13 | 94.40 | ||||||

| T2T-ViT_19 | 93.20 | 97.73 | 93.20 | ||||||

| T2T-ViT_24 | 93.40 | 97.80 | 93.40 | ||||||

| [71] | ViT with Logit Loss Function | Captures global features via self-attention mechanism reducing reliance on local texture features. Adjusting classifier’s logit weights and modified to a logit cross-entropy function with L2 regularization as loss function. | D7* | Acc (%) | Sen. (%) | Spec. (%) | |||

| Early DME | 90.87 | 87.03 | 93.02 | ||||||

| Advanced DME | 89.96 | 88.18 | 90.72 | ||||||

| Severe DME | 94.42 | 63.39 | 98.4 | ||||||

| maculopathy | 95.13 | 89.42 | 96.66 | ||||||

| OA: 87.3% | |||||||||

| [72] | Model-Based ViT (MBT-ViT), Model-Based ViT (MBT-SwimT), Multi-Scale Model-Based ViT (MBT-ViT) |

Approximate sparse representation MBT utilizes ViT Swin ViT and Multiscale ViT for OCT video classification. Then estimates key features before performing data classification. | D4 | Acc. | Recall | ||||

| MBT ViT | 0.8241 | 0.8138 | |||||||

| MBT SwinT | 0.8276 | 0.8172 | |||||||

| MBT_MViT | 0.9683 | 0.9667 | |||||||

| [73] | Structure-Oriented Transformer (SoT) |

SoT employs guidance mechanism that acts as a filter to emphasize the entire retinal structure. Utilizes Vote Classifier, which optimizes the utilization of all output tokens to generate the final grading results. | B-acc | Sen | Spe | ||||

| D1SoT | 0.9935 | 0.9925 | 0.9955 | ||||||

| D5 SoT | 0.9935 | 0.9925 | 0.9955 | ||||||

| [74] | OCT Multihead Self-Attention (OMHSA) | OMHSA enhances self-attention mechanism by incorporating local information extraction, where a network architecture, called OCTFormer and is built by repeatedly stacking convolutional layers and OMHSA blocks at each stage. | D4 | ACC | Prec. | Sen. | |||

| OCT Former-T |

94.36 | 94.75 | 94.37 | ||||||

| OCT Former-S |

96.67 | 96.78 | 96.68 | ||||||

| OCT Former-B |

97.42 | 97.47 | 97.43 | ||||||

| [75] | Squeeze Vision transformer (S-ViT) |

SViT combines SqueezeNet and ViT to capture local and global features, which enables more precise classification while maintaining lower computational complexity. |

D5 Acc.: 0.9990, Sen.: 0.9990, Prec.: 1.000 |

||||||

| [22] | Deep Relation Transformer (DRT) | DRT integrates both OCT and Vision Field (VF) data, where this model incorporates a deep reasoning mechanism to identify pairwise relationships between OCT and VF. | D10Ablation Study | ||||||

| Back-bone | Acc (%) | Sen (%) | Spec (%) | ||||||

| Light ResNet | 88.3±1.0 | 93.7±3.5 | 82.4±4.1 | ||||||

| ResNet-18 | 87.6±2.3 | 93.1±2.4 | 82.1±4.3 | ||||||

| ResNet-34 | 87.2±1.6 | 90.4±5.0 | 83.9±3.6 | ||||||

| [76] | Conv-ViT – inception V3 and ResNet50 | Integrates Inception-V3 and ResNet-50 to capture texture information by evaluating the relationships between nearby pixels. A Vision Transformer processes shape-based features by analyzing correlations between distant pixels. | D4 | Feature Level Concatenation |

Decision Level Conc. |

||||

| Acc. | 94.46% | 87.38% | |||||||

| Prec. | 0.94 | 0.87 | |||||||

| Recall | 0.94 | 0.86 | |||||||

| F1 Score | 0.94 | 0.86 | |||||||

| [77] | Multi-contrast Network |

ViT Cross-modal multi-contrast network integrates color fundus photographs (CFP), which utilizes multi-contrast learning to extract features. Then a channel fusion head then aggregates across different modalities. | D4 | Acc (%) | SE (%) | SP (%) | |||

| Normal | 99.5 | 99.38 | 100 | ||||||

| CNV | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||||||

| DR | 99.5 | 100 | 99.42 | ||||||

| AMD | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||||||

| All | 99.75 | 99.84 | 99.85 | ||||||

| [78] | Swin Transformer V2 with Poly Loss function | Swin Transformer V2-based leverages self-attention within local windows while using a PolyLoss function | D4 | Acc. | Recall | Spec. | |||

| CNV | 0.999 | 1.00 | 0.996 | ||||||

| DME | 0.999 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| DRUSEN | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| NORMAL | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| D6 | Acc. | Recall | Spec. | ||||||

| AMD | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| CNV | 0.989 | 0.949 | 0.995 | ||||||

| CSR | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| DME | 0.992 | 0.977 | 0.995 | ||||||

| DR | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| DRUSEN | 0.988 | 0.934 | 0.995 | ||||||

| MH | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| NORMAL | 0.991 | 0.98 | 0.992 | ||||||

| [79] | Lesion-localization convolution transformer (LLCT) |

LLCT combines CNN-extracted feature maps with a self-attention network to capture both local and global image context. The model uses backpropagation to adjust weights, enhancing lesion detection by integrating global features from forward propagation. | D4 | Acc (%) | Sens (%) | Spec. (%) | |||

| CNV | 98.1 ± 1.9 | 99.4 ± 0.3 | 97.6 ± 2.7 | ||||||

| DME | 99.6 ± 0.2 | 99.6 ± 0.0 | 99.5 ± 0.3 | ||||||

| Drusen | 98.1 ± 2.3 | 92.8 ± 8.5 | 99.9 ± 0.2 | ||||||

| Norm | 99.6 ± 0.6 | 98.8 ± 1.7 | 99.9 ± 0.2 | ||||||

| [80] | Stitched MedViTs | Stitching approach combines two MedViT models to find an optimal architecture. This method inserts a linear layer between pairs of stitchable layers, with each layer selected from one of the input models, creating a candidate model in the search space. | D4 | Spec. | Acc. | ||||

| micro MedViT | 0.928 ± 0.002 | 0.828 ± 0.007 | |||||||

| tiny MedViT | 0.933 ± 0.002 | 0.841 ± 0.007 | |||||||

| micro MedViT | 0.987 ± 0.001 | 0.977 ± 0.002 | |||||||

| tiny MedViT | 0.986 ± 0.002 | 0.977 ± 0.004 | |||||||

| [81] | Bidirectional Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) | Combines a pre-trained Vision Transformer for slice-wise feature extraction with a bidirectional GRU to capture inter-slice spatial dependencies, enabling analysis of both local details and global structural integrity. | D4 | ACC | SEN | SPE | |||

| ResNet34 + GRU | 87.39 (± 1.73) | 92.03 | 72.86 | ||||||

| ViT-large + GRU | 90.27 (± 1.44) | 94.25 | 78.18 | ||||||

| Ref | Adversarial Samples introduced | Modality | Technique Employed |

|---|---|---|---|

| [27] | Gaussian Distributed Noise with various noise levels | OCT images | MKW-LBP local descriptor with SVM and Random forest classifiers |

| [86] | Pepper Noises with various noise densities | Skin Cancer Images | OS-LBP codes skin cancer images and is used to train CNN models. Trained models are employed for identifying potential skin cancer areas and to mitigate the effects of image degradation. |

| [87] | Contrast Degradations | Endoscopic Images | Encodes WCE images using CQ-MPP and is used to train CNN models. Trained are employed for identifying areas of lesions and to mitigate the effects contrast degradations. |

| [88] | Fast Gradient Sign Method (FGSM) | Skin cancer images, MRI | Adversarial Training using Inception for skin cancer classification and Brain tumors segmentations |

| [89] | FGSM Perturbations, Basic Iterative Method (BIM), Projected Gradient Descent (PGD), Carlini and Wagner (CW) Attack | Eye Fundus, Lung X-Rays, Skin Cancer images | KD models normal samples within the same class as densely clustered in a data manifold, whereas adversarial samples are distributed more sparsely outside the data manifold. LID is a metric used to describe the dimensional properties of adversarial subspaces in the vicinity of adversarial examples. |

| [94] | Frequency constraint-based adversarial attack | 3D-CT, a 2D chest X-Ray image dataset, a 2D breast ultrasound dataset, and a 2D thyroid ultrasound | A perturbation constraint, known as the low-frequency constraint, is introduced to limit perturbations to the imperceptible high-frequency components of objects, thereby preserving the similarity between the adversarial and original examples. |

| [95] | Model Ensemble Feature Fusion (MEFF) | Fundoscopy, Chest X-Ray, Dermoscopy | MEFF approach is designed to mitigate adversarial attacks in medical image applications by combining features extracted from multiple deep learning models and training machine learning classifiers using these fused features. |

| [96] | Multi-View Learning | Natural RGB Images | A multi-view classification method with an adversarial sample uses the evidential dissonance measure in subjective logic to evaluate the quality of data views when subjected to adversarial attacks. |

| [97] | Medical morphological knowledge-guided | Lung CT Scans | This approach trains a surrogate model with an augmented dataset using guided filtering to capture the model’s attention, followed by a gradient normalization-based prior knowledge injection module to transfer this attention to the main classifier. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).