Submitted:

27 June 2025

Posted:

27 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

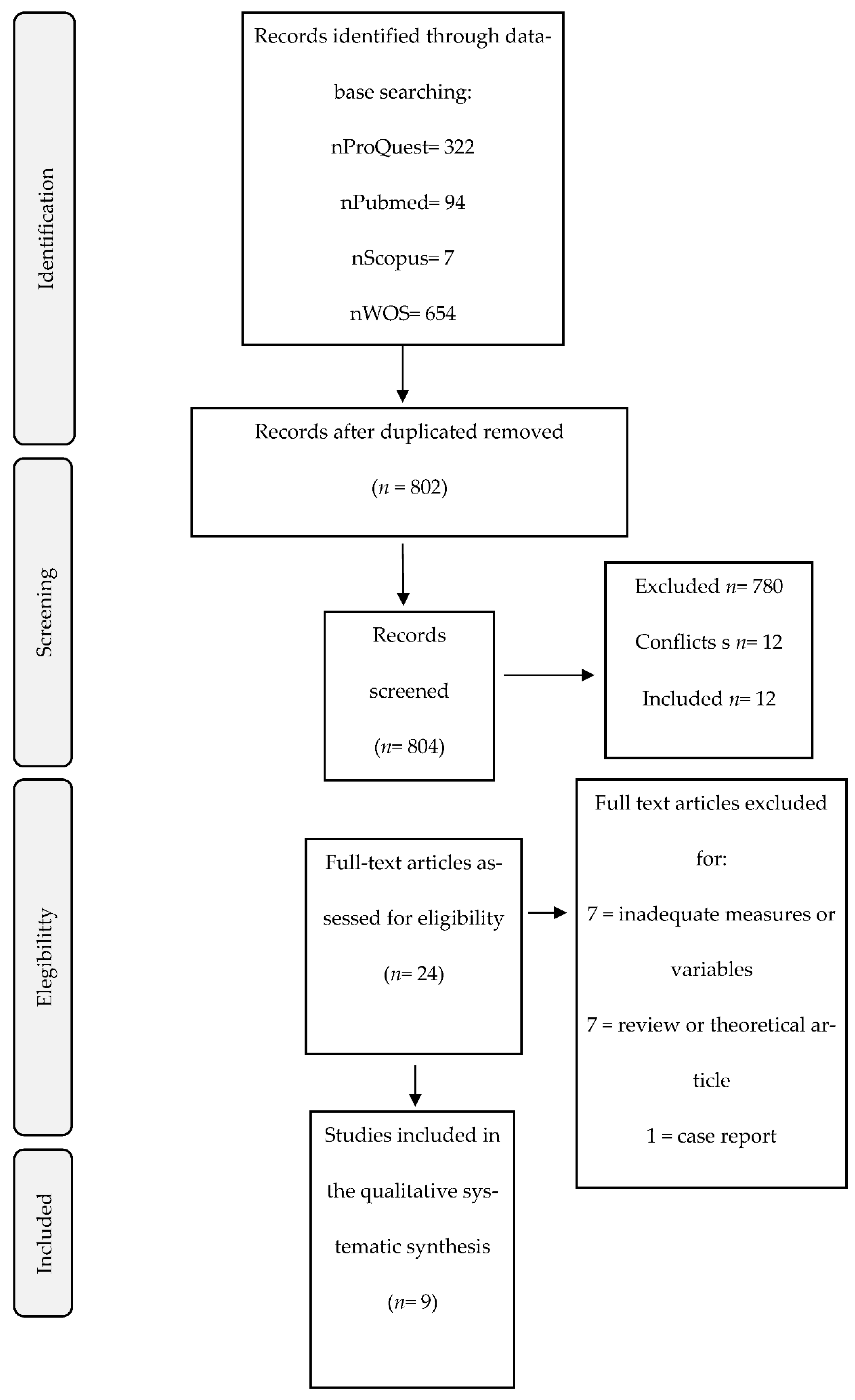

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedure & Ethical Considerations

2.2. Quality Assessment

2.3. Study Selection and Screening

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics.

3.1.1. Participants

3.1.2. Sample Selection and Research Design

3.1.3. Variables: Attachment Evaluation

3.2. Main Results

3.2.1. Attachment

3.2.2. Pregnancy Experience and Support

3.2.3. Psychopathology

3.2.4. Influential Variables

3.3. Quality Assessment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Taebi, M., Alavi, N. M., & Ahmadi, S. M. (2020). The experiences of surrogate mothers: A qualitative study. Nursing and Midwifery Studies, 9(2), 51–59. [CrossRef]

- Gunnarsson Payne, J., Korolczuk, E., & Mezinska, S. (2020). Surrogacy relationships: a critical interpretative review. Upsala Journal of Medical Sciences, 125(2), 183–191. [CrossRef]

- Kardasz, Z., Gerymski, R., & Parker, A. (2023). Anxiety, Attachment Styles and Life Satisfaction in the Polish LGBTQ+ Community. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(14), 6392. [CrossRef]

- *Fischer, S., & Gillman, I. (1991). Surrogate Motherhood: Attachment, Attitudes and Social Support. Psychiatry (New York), 54(1), 13–20. [CrossRef]

- van den Akker, O. B. A. (2017). Separation and Parenting a Surrogate Baby. Surrogate Motherhood Families, 147–168. [CrossRef]

- Rubin, R. (1984) Maternal identity and the maternal experience. New York: Springer.

- Baslington, H. (2002). The social organization of surrogacy: Relinquishing a baby and the role of payment in the psychological detachment process. Journal of Health Psychology, 7(1), 57–71. [CrossRef]

- Snyder, K. S., Luchner, A. F., & Tantleff-Dunn, S. (2023). Adverse childhood experiences and insecure attachment: The indirect effects of dissociation and emotion regulation difficulties. Psychological Trauma, Advance online publication. [CrossRef]

- Jadva, V., Jones, C., Hall, P., Imrie, S., & Golombok, S. (2023). “I know it’s not normal but it’s normal to me, and that’s all that matters”: experiences of young adults conceived through egg donation, sperm donation, and surrogacy. Human Reproduction, 38(5), 908–916. [CrossRef]

- Riddle, M.P. (2022). The psychological impact of surrogacy on the families of gestational surrogates: implications for clinical practice. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology, 43(2), 122–127. [CrossRef]

- Dumitru, A. E., Gică, C., Iordăchescu, D. A., Panaitescu, A. M., Peltecu, G., Botezatu, R., & Gică, N. (2021). Gestational surrogacy. Medical, psychological and legal aspects. Rjlm.Ro, 29, 323–327. [CrossRef]

- Edelmann, R.J. (2004). Surrogacy: the psychological issues. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 22(2), 123–136. [CrossRef]

- Yau, A., Friedlander, R. L., Petrini, A., Holt, M. C., White, D. E., Shin, J., Kalantry, S., & Spandorfer, S. (2021). Medical and mental health implications of gestational surrogacy. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 225(3), 264–269. [CrossRef]

- Mamédio, C., Andrucioli de Mattos, C., & Cuce, M. (2007). The PICO strategy for the research question construction and evidence search. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem, 15(3). [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., ... & Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372.

- Steel, P., Fariborzi, H., & Hendijani, R. (2023). An Application of Modern Literature Review Methodology: Finding Needles in Ever-Growing Haystacks. Sage Research Methods: Business. [CrossRef]

- Orwin, R. G. (1994). Evaluating coding decisions. In H. Cooper & L. V. Hedges (Eds.), The handbook of research synthesis (pp. 139–162). Russell Sage Foundation.

- Hernández-Nieto, R. A. (2002). Contribuciones al análisis estadístico: sensibilidad estabilidad y consistencia de varios coeficientes de variabilidad relativa y el coeficiente de variación proporcional cvp el coeficiente. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Pub.

- Thomas, H. (2003). Quality assessment tool for quantitative studies. Effective Public Health Practice Project. https://www.ephpp.ca/quality-assessment-tool-for-quantitative-studies/.

- Glonti, K., Gordeev, V. S., Goryakin, Y., Reeves, A., Stuckler, D., McKee, M., & Roberts, B. (2015).A Systematic Review on Health Resilience to Economic Crises. PLOS ONE, 10(4), e0123117. [CrossRef]

- *Lamba, N., Jadva, V., Kadam, K., & Golombok, S. (2018). The psychological well-being and prenatal bonding of gestational surrogates. Human Reproduction, 33(4), 646–653. [CrossRef]

- Lorenceau, E. S., Mazzucca, L., Tisseron, S., & Pizitz, T. D. (2015). A cross-cultural study on surrogate mother’s empathy and maternal-foetal attachment. Women and Birth, 28(2), 154–159. [CrossRef]

- *Carone, N., Baiocco, R., Lingiardi, V., & Kerns, K. (2020). Child attachment security in gay father surrogacy families: Parents as safe havens and secure bases during middle childhood. Attachment and Human Development, 22(3), 269–289. [CrossRef]

- *Carone, N., Mirabella, M., Innocenzi, E., Quintigliano, M., Antoniucci, C., Manzi, D., Fortunato, A., Giovanardi, G., Speranza, A. M., & Lingiardi, V. (2023). The intergenerational transmission of attachment during middle childhood in lesbian, gay, and heterosexual parent families through assisted reproduction: The mediating role of reflective functioning. Attachment and Human Development, 1–27. [CrossRef]

- *Carone, N. (2022). Family alliance and intergenerational transmission of coparenting in gay and heterosexual single-father families through surrogacy: associations with child attachment security. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(13). [CrossRef]

- *Carone, N., Barone, L., Manzi, D., Baiocco, R., Lingiardi, V., & Kerns, K. (2020). Children’s exploration of their surrogacy origins in gay two-father families: longitudinal associations with child attachment security and parental scaffolding during discussions about conception. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 512702. [CrossRef]

- *Carone, N., Manzi, D., Barone, L., Lingiardi, V., Baiocco, R., & Bos, H. M. W. (2021). Father–child bonding and mental health in gay fathers using cross-border surrogacy during the COVID-19 pandemic. BioMedicine Online, 43(4), 756–764. [CrossRef]

- *Carone, N., Manzi, D., Barone, L., Mirabella, M., Speranza, A. M., Baiocco, R., & Lingiardi, V. (2023). Disclosure and child exploration of surrogacy origins in gay father families: Fathers’ Adult Attachment Interview coherence of mind matters.of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 42(5), 977–992. [CrossRef]

- Kerns, K., Mathews, B. L., Koehn, A. J., Williams, C. T., & Siener-Ciesla, S. (2015). Assessing both safe haven and secure base support in parent-child relationships. Attachment & Human Development, 17(4), 337–353. [CrossRef]

- Calvo, V. (2008). Aspetti di validazione della Security Scale in ambito italiano: Consistenza interna e distribuzione dei punteggi (Manoscritto non pubblicato).Università degli Studi di Padova.

- Marci, T., Lionetti, F., Moscardino, U., Pastore, M., Calvo, V., & Altoé, G.(2018). Measuring attachment security via the Security Scale: Latent structure, invariance across mothers and fathers and convergent validity. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 15(4), 481–492. [CrossRef]

- Condon, J. T. (1993). T The assessment of antenatal emotional attachment: Development of a questionnaire instrument.British Journal of Medical Psychology, 66(2), 167–183. [CrossRef]

- Della Vedova, A. M., & Burro, R. (2017). Surveying prenatal attachment in fathers: the Italian adaptation of the Paternal Antenatal Attachment Scale (PAAS-IT). Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 35(5), 493–508. [CrossRef]

- Steele, H., & Steele, M. (2005). The construct of coherence as an indicator of attachment security in middle childhood: The Friends and Family Interview. In Attachment in Middle Childhood (pp. 137–160). Guilford Press.

- Cranley, M. S. (1981). Development of a tool for the measurement of maternal attachment during pregnancy. Nursing Research, 30, 281–284.

- George, C., Kaplan, N., & Main, M. (1985). Adult Attachment Interview protocol (Unpublished manuscript). UC Berkeley.

- Main, M., Goldwyn, R., & Hesse, E. (2002). Adult Attachment Scoring and Classification Systems (Unpublished Manual). UC Berkeley.

- Grabow, A., & Becker-Blease, K. (2023). Acquiring psychopathy and callousness traits: Examining the influence of childhood betrayal trauma and adult dissociative experiences in a community sample. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 24(2), 268–283. [CrossRef]

- Yárnoz, S., Alonso-Arbiol, I., Plazaola, M., María, L., & De Murieta, S. (2001). Apego en adultos y percepción de los otros. Anales de Psicología, 17(2), 159–170. [CrossRef]

- Dávila, Y. (2015). La influencia de la familia en el desarrollo del apego. Revista Anales, 57, 121–130. https://publicaciones.ucuenca.edu.ec/ojs/index.php/anales/article/view/792.

- Yılmaz, H., Arslan, C., Arslan, E., Yılmaz, H., Arslan, C., & Arslan, E. (2022). El efecto de las experiencias traumáticas en los estilos de apego. Anales de Psicología, 38(3), 489–498. [CrossRef]

| Author and year | Country and participants | Variables | Design | Main results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fischer & Gillman (1991) |

USA 42 women (21 GS; 21 pregnant but not through GS) |

- Sociodemographic and clinical variables: age, place of birth, marital status, educational level, socioeconomic status, religious affiliation, duration of pregnancy, and average number of children born. - Psychological variables: number of interpersonal resources and perceived support level, maternal-fetal attachment, maternal attitudes, self-perception, and pregnancy-related behavior. |

Observational, descriptive, cross-sectional, comparative. | Non-gestational mothers through surrogacy were more bonded to the unborn baby in: differentiation of the "self" from the fetus (t(40) = 8.14, p < .05), interaction with the baby (t(40) = 6.91, p < .05), and attribution of characteristics and intentions to the baby (t(40) = 2.07, p < .05). Surrogate mothers had more positive attitudes towards body image (t(40) = 2.07, p < .05) and attitudes towards sex (t(40) = 2.82, p < .05). They had more negative attitudes towards pregnancy and the baby (t(40) = 11.58, p < .05). |

| Lorenceau et al. (2015) | France N = 76 (44 GS; 32 mothers but not through GS) |

- Sociodemographic and clinical variables: age, nationality, age at first GS/pregnancy (comparison group), type of GS, number of children by type of GS, number of biological children, number of children by non-gestating parents' sex, desire to repeat GS experience, and previous losses before GS. - Psychological variables: empathy (personal distress, empathic concern, perspective taking, and fantasy scale), emotional state (depression and anxiety), desirability scale (social desirability), and attachment (attachment quality and attachment quantity). |

Observational, cross-sectional. | Anglo-Saxon and European surrogate mothers had lower maternal-fetal attachment (AGEST δ = 0.95) and quality (AGEST δ = 1.52), and less empathy (AGEST δ = 1.04, p < 0.05). The type of surrogacy had effects on the number of gestational or traditional children born (H(2) = 13.833, p < 0.001), as well as on the quality of maternal-fetal attachment. |

| Lamba et al. (2018) | India 119 women (50 GS; 69 pregnant but not through GS) |

- Sociodemographic variables: age, educational level, marital status, number of children, income level, religious affiliation. - Psychological variables: anxiety, depression, stress, emotional and instrumental prenatal bond, GS experiences including concealment, criticism, living situation, perceived support, satisfaction with payment, meeting the newborn, and meeting the intended parents. |

Correlational, longitudinal (T1 between 4-9 months of pregnancy; T2 between 4-6 months after birth). | Surrogate mothers had more depression before (χ²(1) = 12.9, p < 0.001) and after (χ²(1) = 6.12; p = 0.01) childbirth than non-surrogate mothers (p < 0.02), lower maternal-fetal attachment (F(1, 116) = 4.19, p = 0.04) but higher attention and care towards the unborn baby (F(1, 116) = 4.27, p = 0.04). |

| Carone, Baiocco et al. (2020) | Italy 30 children born via GS aged 7 to 13 years and their 66 same-sex parents. |

- Sociodemographic and clinical variables: age, child's sex, number of siblings, parents' ethnicity, family residence, parents' education, parents' occupation, parents' employment status, duration of the couple's relationship, child's age at t1, child's age at t2, parents' age, and annual household income. - Psychological variables: children's attachment and exploration of their surrogacy origins. |

Observational, longitudinal (T1 mean age of children was 8.3 years, T2 was 18 months later). Observational, cross-sectional, non-experimental. | The age of the children, main and interactive effects of parental support, and children's attachment security as predictors explained children's exploration of their origins, with high variance (TCD = 0.34) and low BIC (163.22). Parental scaffolding* and attachment security are interrelated (β = 0.23, p = 0.048) and affect how children explore their origins. Children with greater attachment security reported more exploration of their surrogacy origins (β = 0.30, p = 0.009), but only when there were higher levels of parental scaffolding (β = 0.20, p = 0.072). Along with the child's age factor (β = 0.02, p < 0.001), these predicted greater exploration. |

| Carone, Barone et al. (2020) | Italy 387 children (33 born via GS; 37 children born via insemination; 317 control group) and their families (66 same-sex parents; 74 lesbian parents; 634 heterosexual families). |

-Sociodemographic and clinical variables: child's sex, number of siblings, parents' ethnic background, parents' residence, parents' educational level, parents' occupation, parents' employment status, duration of the couple's relationship, marital status, genetic parenthood, child's age at the visit, parents' age, and household income. - Psychological variables: Identification of children's primary/secondary attachment figures, attachment, support seeking and affiliative proximity seeking, parenting practices and beliefs. |

Observational, cross-sectional. | The security of children's attachment did not differ by family type (gay fathers or lesbian mothers) (F(1,135) = 2.04, p = .16, ηp² = .02, d = .30). Significant associations between attachment security and positive parental control (b = 0.04, t(117) = 1.96, p = .053), parental warmth (b = 0.09, t(99) = 4.69, p < .001), parental responsiveness (b = 0.10, t(130) = 4.43, p < .001), negative parental control (b = -0.08, t(106) = -2.80, p < .01), parental rejection (b = -0.10, t(122) = -3.18, p < .01) and willingness to serve as an attachment figure (b = 0.19, t(127) = 4.97, p < .001). The willingness of parents to serve as an attachment figure and parental behaviors predicted children's attachment security better than family type (b = 0.03, t(66) = 0.74, p = .46). |

| Carone et al. (2021) | Italy 80 same-sex parents with GS children (30 during COVID-19 and 50 before). |

- Sociodemographic and clinical variables: parents' age, gender, sexual orientation, country of residence, annual household income, education and employment, number, gender, age, and conception method of the child(ren), the country where GS took or is taking place and expected birth date of the baby. - Psychological variables: parent-child bond, parents' mental health, social support, and stressful events. |

Observational, cross-sectional. | A lower father-child bond was observed during the COVID-19 pandemic (SE = 15.45, CI 2.5%-97.5% = 10.20, 73.43, p = 0.010), more depression (SE = 5.53, CI 2.5%-97.5% = 4.89, 25.66, p = 0.004), somatization (SE = 6.06, CI 2.5%-97.5% = 4.91, 30.96, p = 0.006) and anxiety (SE = 5.92, CI 2.5%-97.5% = 7.70, 31.10, p = 0.001), than previously. |

| Carone (2022) | Italy 59 single-parent families (31 same-sex and 28 heterosexuals via GS). |

- Sociodemographic and clinical variables: child's gender, number of siblings, family residence, father's ethnic background, father's educational level, father's employment status, father's marital status, non-parental caregivers involved in shared parenting, child's age, father's age, and annual household income. - Psychological variables: coparenting, child attachment. |

Observational, cross-sectional. | There are no significant differences in: co-parenting quality in families of origin between single gay fathers and single heterosexual fathers (F(1,57) = 0.257, p = 0.614, ηp² = 0.004); children's attachment security between children of single gay and heterosexual fathers (F(1,55) = 0.317, p = 0.860, ηp² = 0.001), nor between boys and girls (F(1,55) = 0.586, p = 0.447, ηp² = 0.011); family alliance by family type (Wilks’ λ(16,40) = 0.727, p = 0.536, ηp² = 0.273), nor the child's gender (Wilks’ λ(16,40) = 0.739, p = 0.590, ηp² = 0.261), nor their interaction (Wilks’ λ(16,40) = 0.784, p = 0.787, ηp² = 0.216). Significant relationship between co-parenting quality in the family of origin and children's attachment security, through conflict observed during family interactions (LTP) (estimated point = 0.561, SE = 0.269, 95% CI [0.084, 1.121], p = 0.037). No relationship between co-parenting quality in the family of origin and children's attachment security through support observed during family interactions. |

| Carone, Manzi et al. (2023) | Italy 30 children born via GS and their 60 same-sex parents. |

- Sociodemographic and clinical variables: child's gender assigned at birth, number of siblings, family residence, locations where surrogacy agreements were made, egg donors' identity status at t1, disclosure level at t1, annual household income, duration of the couple's relationship, father's ethnicity, father's education, father's occupation, father's employment status, child's age at t1, child's age at t2, and father's age. - Psychological variables: information about GS, parents' AAI mental coherence, and children's exploration of their surrogacy origins. |

Observational, longitudinal (T1 mean age of 8 years and 3 months (SD = 1.68). T2 mean age of 9 years (SD = 1.69)). | No significant differences were found between boys and girls in the exploration of their surrogacy origins (F(1,28) = 0.308, p = .583, ηp² = 0.011), nor in mind coherence between genetic parents, non-genetic parents, and parents who did not disclose their (non) genetic status (χ²(2) = 0.443, p = .801, ε² = 0.008). The interaction between disclosure and parents' mind coherence at t1 predicted greater exploration in children (β = .296, p = .013). Parents' mind coherence at t1 (β = .220, p = .065), and children's age at t2 (β = .213, p = .096), were not significant. Parents with greater coherence in their interviews (with an AAI range between 1.78 and 6.30) had children who explored their surrogacy origins more deeply. |

| Carone, Mirabella et al. (2023) | 30 lesbian mother dyads via donor insemination, 25 same-sex father dyads via GS, 21 heterosexual father dyads via gamete donation, and 76 children. | - Sociodemographic and clinical variables: child's gender assigned at birth, parents' relationship duration, child's age, number of children, parents' ethnic background, parents' educational level, employment status, parents' age, and net annual income. - Psychological variables: parents' attachment and reflective functioning. Children's attachment and verbal abilities. |

Observational, cross-sectional. | Children of lesbian mothers (β = .46, SE = .34, p = .180), gay fathers (β = -.01, SE = .36, p = .970), and heterosexual parents showed similar levels of attachment security. However, there were no differences based on the parents' gender (β = −.15, SE = .20, p = .450), sexual orientation (β = .22, SE = .26, p = .399), or their interaction (β = −.38, SE = .36, p = .289) in mind coherence. Mothers and fathers showed similar levels of reflective functioning (RF) (β = .19, SE = .17, p = .258). There were no differences in the parents' sexual orientation (β = .43, SE = .21, p = .040), with gay fathers and lesbian mothers showing higher levels of RF than heterosexual parents (main difference = 0.77, SE = 0.27, p = .027). There was a significant interaction between parents' gender and sexual orientation (β = .69, SE = .33, p = .039). There were no differences between family types in the distribution of secure and insecure attachment patterns in children according to the FFI, nor in comparisons with international and national data. There is a significant indirect effect of parents' mind coherence on children's attachment security, mediated by parents' reflective functioning. Parents with greater mind coherence achieved higher levels of RF, and higher RF levels were associated with greater children's attachment security according to the FFI. |

| FISRT AUTOR | DESIGN | REPRESENTATIVENESS | REPRESENTATIVENESS II | CONFOUNDING FACTORS | DATA COLLECTION | DATA ANALYSIS | DATA REPORTING | OVERALL RATING |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FISCHER | 4 | 4 | N/A | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Low-moderate |

| LORENCEAO | 4 | 3 | N/A | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Low-moderate |

| LAMBA | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Low-moderate |

| CARONE | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Low-moderate |

| CARONE | 4 | 2 | N/A | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Low-moderate |

| CARONE | 4 | 3 | N/A | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | Low-moderate |

| CARONE | 4 | 3 | N/A | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | Low-moderate |

| CARONE | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | Low-moderate |

| CARONE | 4 | 3 | N/A | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | Low-moderate |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).