1. Introduction

Sarcoidosis is a complex systemic disease characterized by the formation of granulomas in various organs, predominantly affecting the lungs, lymph nodes, skin, eyes, central nervous system and heart: it remains an insidious disease, since etiology is not fully elucidated yet and because the standard corticosteroid therapy may cause severe collateral effects [

1]. The immune system is engaged in the

incipit of an inflammatory response to different environmental triggers, leading to the formation of granulomas as sarcoidosis histologic hallmark; therefore, understanding its pathogenesis remains an important task to achieve in order to explore alternative therapeutic strategies [

1].

Specifically, this minireview deals with the relationship between Cutibacterium acnes (C. acnes) and sarcoidosis: the medical literature has been screened with the keywords “C. acnes”, “sarcoidosis”, “pathogenesis of sarcoidosis”, and the most significant papers have been selected as the main sources to highlight and review the updated know-how on this topic.

The aim is to summarize the present knowledge about the potential cause-effect relationship existing between C. acnes and sarcoidosis, clarifying the role of specific molecular patterns of C. acnes able to activate immunological pathways relevant in the pathogenesis of sarcoidosis. That will allow the future research and novel therapeutic strategies in the management of a complex disease as sarcoidosis.

2. Cutibacterium acnes: Commensal Bacterium and Opportunistic Pathogen

The genus

Cutibacterium is a cutaneous group of microorganisms previously designated as

Propionibacterium, which has been reclassified into four genera [

2], and is a Gram-positive bacterium considered as commensal, representing the major component of microbiota in human skin and eyes, though also well-represented in the anaerobic component of both intestinal tract and human gingival plaques (

Table 1).

In particular,

C. acnes is an ubiquitous Gram-positive anaerobe slow-growing microorganism present in the sebaceous sites (on the face, back, and pre-thoracic region), with individual-specific rather than site-specific distribution [

6].

C. acnes is usually considered a commensal, i.e. a member of the skin microbiota, established through adaptive immune tolerance mechanisms put in action since the early neonatal period [

7]. Epidermis has a complex structure with many functions, such as to protect and defend the body from external hazards by acting as a physical and immunological barrier modulating the microbiota [

8]. The healthy skin harbors microorganisms from multiple kingdoms: bacteria, fungi, and viruses; in particular

Cutibacterium biofilm formation is significantly enhanced in the presence of staphylococcal strains, enabling robust growth under both anaerobic and aerobic conditions [

9].

C. acnes strains can be divided into the major types IA, IB, II, and III, according to sequence comparison of the

recA or

tly genes [

10]. More recently, further discrimination has been provided by various multilocus sequence typing (MLST) schemes and repetitive-sequence-based PCR protocols [

11,

12,

13,

14].

C. acnes subtype I, more specifically termed I-1a, is predominantly associated with moderate-to-severe acne [

12,

13]. In contrast,

C. acnes type II is reported as the most prevalent type by previous studies of prostatic specimens from patients with prostate cancer (PCa) [

15].

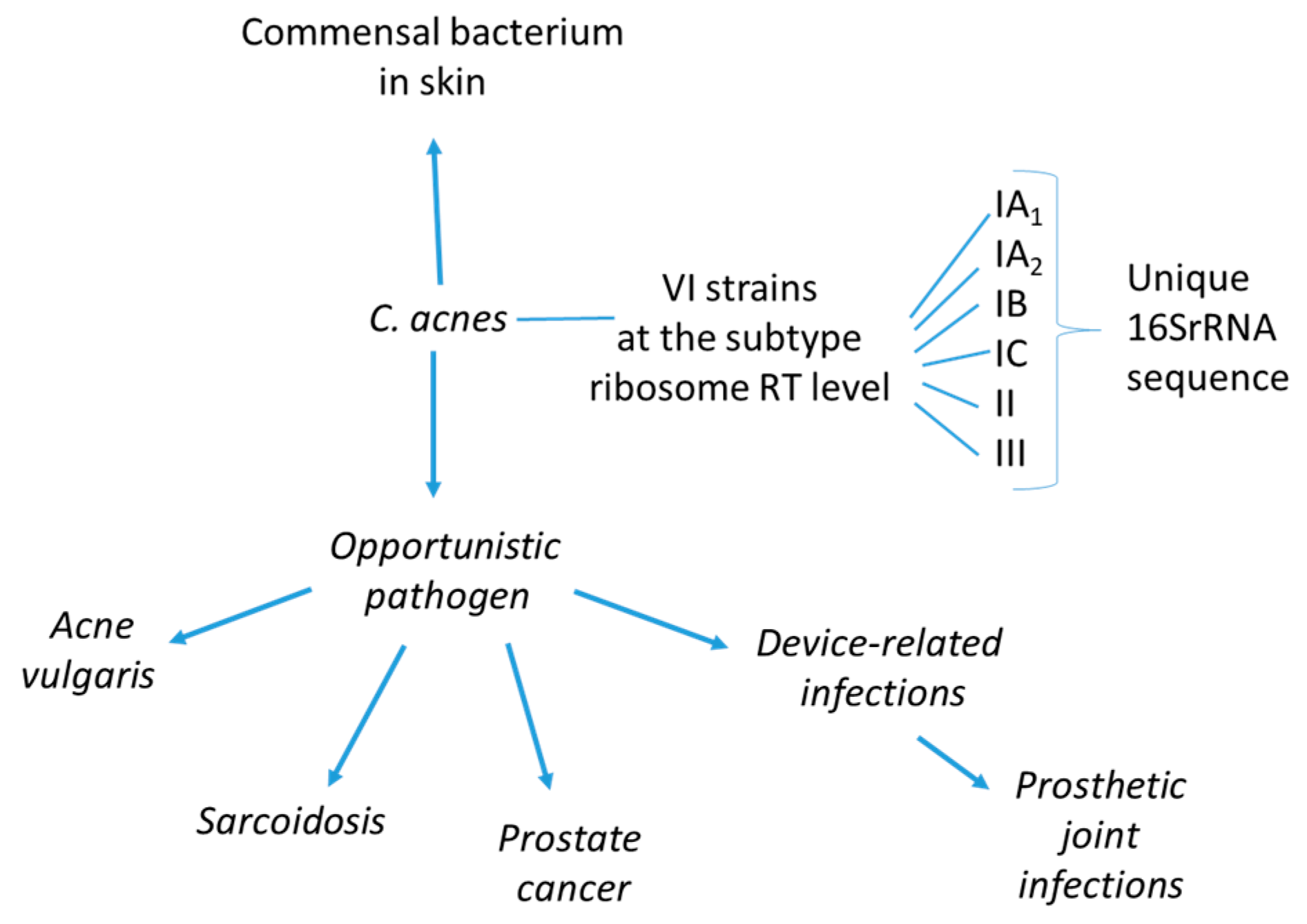

C. acnes is believed to play a remarkable role in maintaining skin health via occupation of ecological niches that could be colonised by more pathogenic microbes; it produces short chain fatty acids, thiopeptides, bacteriocins, and other molecules with inhibitory properties against such organisms [

16]. Moreover, it plays a role in the balance between healthy and inflamed skin (as in the case of acne disease), acting also as an opportunistic pathogen in other various inflammatory conditions, including sarcoidosis, PCa and prosthetic joint infections (

Figure 1).

There is evidence of certain disease-associated phylotypes of the bacterium persisting on body implants and causing postoperative inflammation such as endocarditis, endophthalmitis and intravascular nervous system infections [

17]. Tissue invasion and deposition of

C. acnes have also been reported in glandular epithelial cells and circulating macrophages contributing to benign prostate hyperplasia [

18]. Moreover, the prevalence of the phylotypes IA-1 over the others, rather than a change in the abundance of

C. acnes, is responsible for the development of acne [

19,

20].

Figure 1.

Cutibacterium acnes is considered an opportunistic microorganism, with the potential to switch from being a commensal to a pathogen causing different diseases. The

C. acnes different phylotypes recognised by MALDI-MS prototyping [

21] are shown.

Figure 1.

Cutibacterium acnes is considered an opportunistic microorganism, with the potential to switch from being a commensal to a pathogen causing different diseases. The

C. acnes different phylotypes recognised by MALDI-MS prototyping [

21] are shown.

However, beyond the evidence that analysis of these infections has shown an involvement of different phylotypes of the bacterium, it remains important to ascertain whether the isolation of

C. acnes strains in different tissues should be considered as a true infection or a contamination [

3]. To date, it is not clear which are the underlying mechanisms set in motion by

C. acnes strains to result in infection, inflammation and/or localization in distant parts of the body. However, it is known that bacteria-infected cells secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines and also anti-microbial factors, all playing a role in the delicate balance between functional and dysfunctional (disease) conditions [

22].

2.1. Molecular Markers of Cutibacterium acnes

C. acnes strains show both high- and low-inflammatory potential, but the individual colonization by a microorganism sequence does not predict the host susceptibility to the disease [

23]. It is largely accepted that almost all

C. acnes subspecies and phylotypes share a similar invasiveness ability [

24]. Several molecular markers exist, which can lead to

C. acnes identification, typing and different pathogenic roles in many clinical conditions. For instance, lipidomic analysis helped identifying specific lipid markers of

C. acnes species such as phosphatidylcholine (PC) 30:0, sphingomyelins (SM) 33:1 and 35:1, derived phosphatidylglycerol

(PG) with an alkyl ether substituent PG O-32, and cardiolipins/fatty acid amides, specific of different phylotypes with potential diagnostic value [

23,

25].

Indeed, each

C. acnes type (IA1, IB, II, and III) exhibits pathogenic or commensal potential. Type I strains abundantly produce lipases, proteinases, and hyaluronidases, and type IA1 has previously been isolated from acne-prone skin; hence, it is considered a particularly virulent and prevalent strain in conditions such as acne vulgaris [

26]. Analyzing the lipidome of each

C. acnes strain, individual lipid compounds are considered markers for a given phylotype; i.e.

C. acnes DSM 16379 (type IB), has a significant amount of PC 30:0. In addition to their obvious structural role, these PCs presumably play an active role in virulence determination, confirming the pathogenic potential of type I strains [

27]. Type II and III

C. acnes are considered to represent “healthy skin” microbiota species [

28]. While some bacterial strains are capable of producing sphingolipids, they can also acquire them from a mammalian host: the acquired sphingolipids can then be modified by bacterial enzymes to produce new sphingolipids, which help to conceal microorganisms from the host immune system [

29]. Particularly noteworthy is sphingomyelin SM 35:1, whose distinct amounts are observed only in

C. acnes strains PCM 2334 and DSM 13655, which are type II and III, respectively. This finding supports the hypothesis that the acquisition and modification of host sphingolipids may lead to commensalism or hostile interactions (tissue damage/disease) [

29].

C. acnes produces two variants of hyaluronate lyase (HYL). The HYL-IB/II variant has a high level of activity and can completely degrade the hyaluronic acid (HA) present in type IB and II strains; the HYL-IA variant has a lower level of activity and can only partially degrade the HA present only in type IA strains [

30]. This difference in expression between

C. acnes strains may account for differences in tissue invasion capability between phylotypes. Indeed, type AI strains are found mostly on the surface of the skin in inflammatory acne, whereas type IB/II strains are more frequently associated with deep soft tissue infections [

31]. HYL is considered to act as a virulence factor by facilitating the bacterial invasion of tissues and degrading the compounds of the upper layers of skin and its extracellular matrix, thereby promoting the spread of inflammation. In addition, the products of HA degradation by HYL may be used as nutrients by the bacterium, but may also variably contribute to inflammation [

32,

33].

T helper type 1 (

Th1) immune responses to catalase (KAT) C. acnes were measured by interferon (IFN)-γ assay in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from 12 sarcoidosis patients, 13 other pneumonitis patients, and 11 healthy volunteers; the KAT protein provoked a significantly higher response in sarcoidosis patients [

34]

.

The

C. acnes-related inflammation produces matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) activation, contributing to tissue remodeling; other markers are adhesion factors and pore forming toxins, CMP1 to CMP5 [

35], lipase-mediated free fatty acids and coproporphyrin III. The latter one contributes to the perifollicular inflammatory reaction by stimulating the expression of pro-inflammatory molecules, such as CXCL8/IL-8 and prostaglandin PGE2 [

4] of keratinocytes, inducing the aggregation of

Staphylococcus aureus and formation of biofilms in the nose [

4].

2.2. Innate and Acquired Immunity in the Pathogenicity of Cutibacterium acnes

The causal relationship between dysfunctional microbiome and disease states requires a careful analysis taking into account bacterial strain heterogeneity, host genetics as well as host's environments. Many factors contribute to the development of

C. acnes infection, first of all the role played by host immunity. As commensal,

C. acnes stays latent in the body until a mixture and overlapping of triggering insults activate it towards the switching to be pathogenic. In this process,

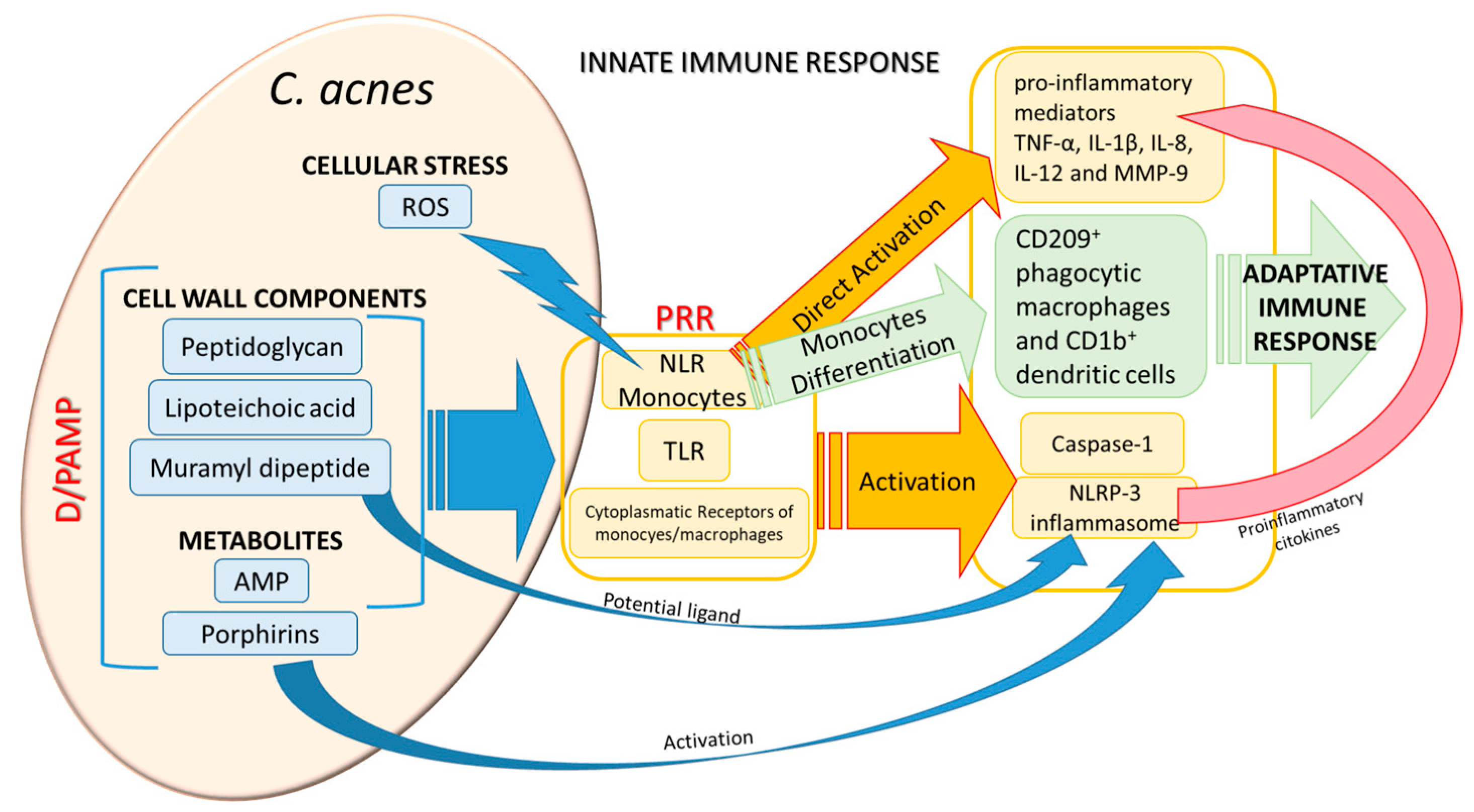

C. acnes can elicit many different responses from the host: after the initial recognition process of the bacterium danger- or pathogen-associated molecular patterns (D/PAMP) by the host patterns recognition receptors (PRR), a cascade of chemokines is produced by innate immune response followed by the host modulation of adaptive immune response.

C. acnes final effects on the host are the complex result of a fine balance between evasion and stimulation mechanisms.

C. acnes also represents a priming agent enhancing the efficacy of the host anti pathogenic response [

36]. The first step in the switching process from commensal into pathogenic implies the recognition process by the host.

C. acnes has many arrows to its bow for being recognized by the host as a prostimulatory agent by its cell-wall components (peptidoglycan, lipoteichoic acid, muramyl dipeptide, etc) or through metabolite production such as porphyrins [

37] and antimicrobial peptides (AMP)[

38]. (

Figure 2). The recognition of

C. acnes PAMPs is mediated by host toll-like receptors (TLR) (TLR-2, -4, -6, and the intracellular TLR-9, [

35,

39]), NOD-like receptors (NLR), and monocytes/macrophages cytoplasmic receptors. NLR can be also activated via reactive-oxygen species (ROS) released by

C. acnes-stimulated cellular stress, as shown in

C. acnes-mediated skin inflammation [

40].

The PRR-mediated response results in NLRP3 inflammasome, caspase-1 activation and finally in adaptive immune response. Inflammasome can be also directly activated by either muramyl dipeptide [

41] or porphyrins [

37], potentiating the

C. acnes recognition process by the host. PRR activation elicits different signaling pathways leading to the production of pro-inflammatory mediators; activation of TLR of monocytes produces Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF), IL-1β, IL-8, IL-12 and MMP-9 [

42] and a further differentiation of these monocytes into different subsets which in turn trigger the immune adaptive response [

43]. Cytokine production stimulation by keratinocytes was mediated either by viable bacteria [

44] or by

C. acnes extracellular vesicles [

45].

C. acnes can also evade the host response engaged to eliminate the pathogen attack, such as granuloma formation, extracellular traps, phagocytosis, autophagy and pyroptosis, although little is known about the evasion mechanisms set in motion by the bacterium [

46].

2.3. Association of Cutibacterium acnes with Sarcoidosis

In a Japanese study the isolation frequency of

C. acnes was 78% in a group of 40 sarcoidosis cases, and it increased to 92% when using high osmolarity culture media [

47,

48], and almost all

C. acnes cultures from patients with active sarcoidosis were successful. Compared with sarcoidosis patients, the isolation frequency of

C. acnes in biopsied lymph nodes from control patients without sarcoidosis was significantly lower (25% of 150 cases), and fewer isolated colonies were obtained.

In the bronchoalveolar (BAL) lavage the

C. acnes can be found in approximately 70% of patients with sarcoidosis, being associated with disease activity, though it can also be found in 23% of controls [

49,

50]. Moreover, the immunohistochemistry approach has been used to detect

C. acnes within the granuloma formation [

51] by commercially available

P. acnes-specific monoclonal antibody (PAB antibody). Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue samples from 94 sarcoidosis patients and 30 control patients with other granulomatous diseases were examined by the original manual IHC method:

C. acnes was detected in sarcoid granulomas of samples obtained by transbronchial lung biopsy (64%), video-associated thoracic surgery (67%), endobronchial-ultrasound-guided transbronchial-needle aspiration (32%), lymph node biopsy (80%), and skin biopsy (80%) from sarcoidosis patients, but not in any non-sarcoid granulomas of samples obtained from control subjects (with other granulomatous diseases).

C. acnes signals were observed more frequently in immature granulomas compared to mature granulomas [

52], suggesting that

C. acnes may be degraded and abolished during maturation of the granuloma. Therefore, sarcoidosis should be suspected when

C. acnes is detected in granulomas, but sarcoidosis cannot be ruled out when

C. acnes is not detected in granulomas.

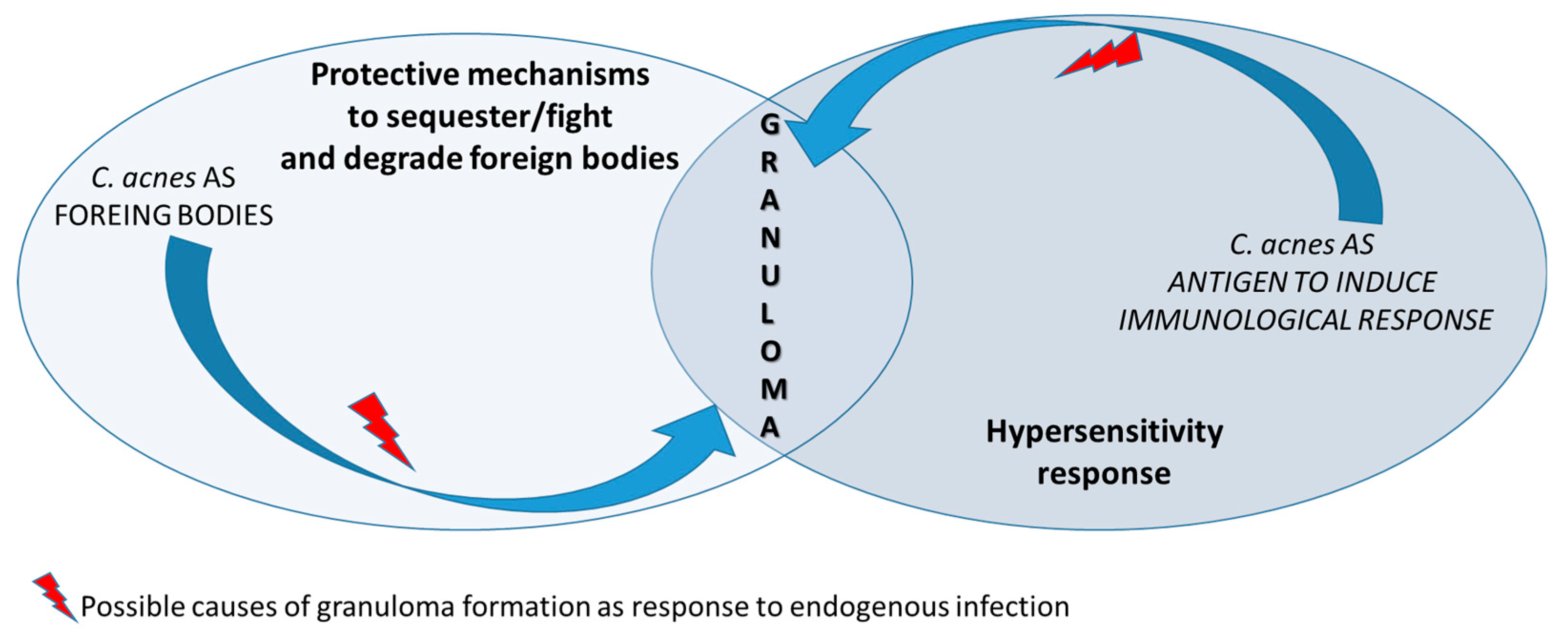

Nowadays, molecular methods (Sanger sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene) in the mediastinal lymph node of patients with sarcoidosis have shown the presence of strains of

Streptococcus gordonii (52 of 71 clones) and

C. acnes (19 of 71 clones) [

53]. Microorganisms usually trigger the sarcoid reaction either because they act as antigens producing the immunological response, or by representing a non-degradable product [

54] (

Figure 3).

3. Sarcoidosis

Sarcoidosis is an intriguing disease studied for decades and whose exact aetiology remains elusive [

55]. It would be useful to consider sarcoidosis as a syndrome comprising multiple genetic predisposing factors and many types of triggers. Recent hypotheses converge on the idea that different environmental triggers (infectious, occupational, etc) may induce a dysregulated inflammatory response in a genetically predisposed individual [

25,

56,

57].

3.1. Genetics

The heritability of sarcoidosis may vary according to ethnicity. About 20% of African Americans with sarcoidosis have a family member with this condition, whereas for European Americans it is about 5%; additionally, in African Americans, who seem to experience a more severe and chronic disease, siblings and parents of sarcoidosis cases have about a 2.5-fold increased risk for developing the disease [

58]. In Swedish individuals heritability was found to be 39% [

59]. In this group, if a first-degree member was affected, a person has a four-fold greater risk of becoming affected [

59].

Investigations of a genetic susceptibility yielded many candidate genes, but only few were confirmed by further investigations and no reliable genetic markers are currently known. The most interesting candidate gene is

BTNL2, [

60] coding for Butyrophilins which inhibit T cell activation and act as negative costimulatory molecules in several conditions such as sarcoidosis, autoimmune diseases, and cancer. Several HLA-DR risk alleles are also being investigated. In persistent sarcoidosis, the HLA haplotype HLA-B7-DR15 is associated with the disease, either directly cooperating in disease development or via another gene between the two loci. In nonpersistent disease, a strong genetic association exists with HLA DR3-DQ2 [

61]. Cardiac sarcoidosis (CS) has been connected to TNF variants, particularly in the promoter region of the TNFA, increasing susceptibility to and the severity of CS. Specifically, certain haplotypes including the A allele at position -308 and the T allele at position -857 have been found to be more prevalent in patients with CS [

62]. There is an individual predisposition to develop

C. acnes infection following a genetic pathway involving genes coding for innate immunity e.g. TLR2 and 4, MAPK, NF-kB, IL-1, IL-6, and IL-8, TNF, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) from keratinocytes, and other inflammatory signalling pathways in the host [

22,

63]. As NF-κB-dependent response to

C. acnes, toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) was shown to represent a critical receptor mediating the selective activation of innate immunity genes [

35]. Therefore, the susceptibility of the host to the latent infection of the bacterium plays an important role in deciding the final fate of the infectious process.

3.2. Sarcoidosis: Immune Pathways

The hypothetical infectious triggers do not make sarcoidosis a simple infectious disease. Among the different microorganisms investigated, the only one that received confirmation was

C. acnes, which has been isolated from sarcoid lesions by bacterial culture [

47].

Invasive

C. acnes can act as bacterial ligands to cause aberrant NOD receptor activation in certain individuals with long-lasting susceptibility to sarcoidosis [

64,

65]. NOD1 and NOD2 are intracellular pattern recognition receptors that can sense bacterial molecules such as peptidoglycan moieties [

66,

67,

68].

C. acnes-mediated aberrant NF-κB activation may induce granuloma formation in a NOD1/NOD2-dependent manner [

22].

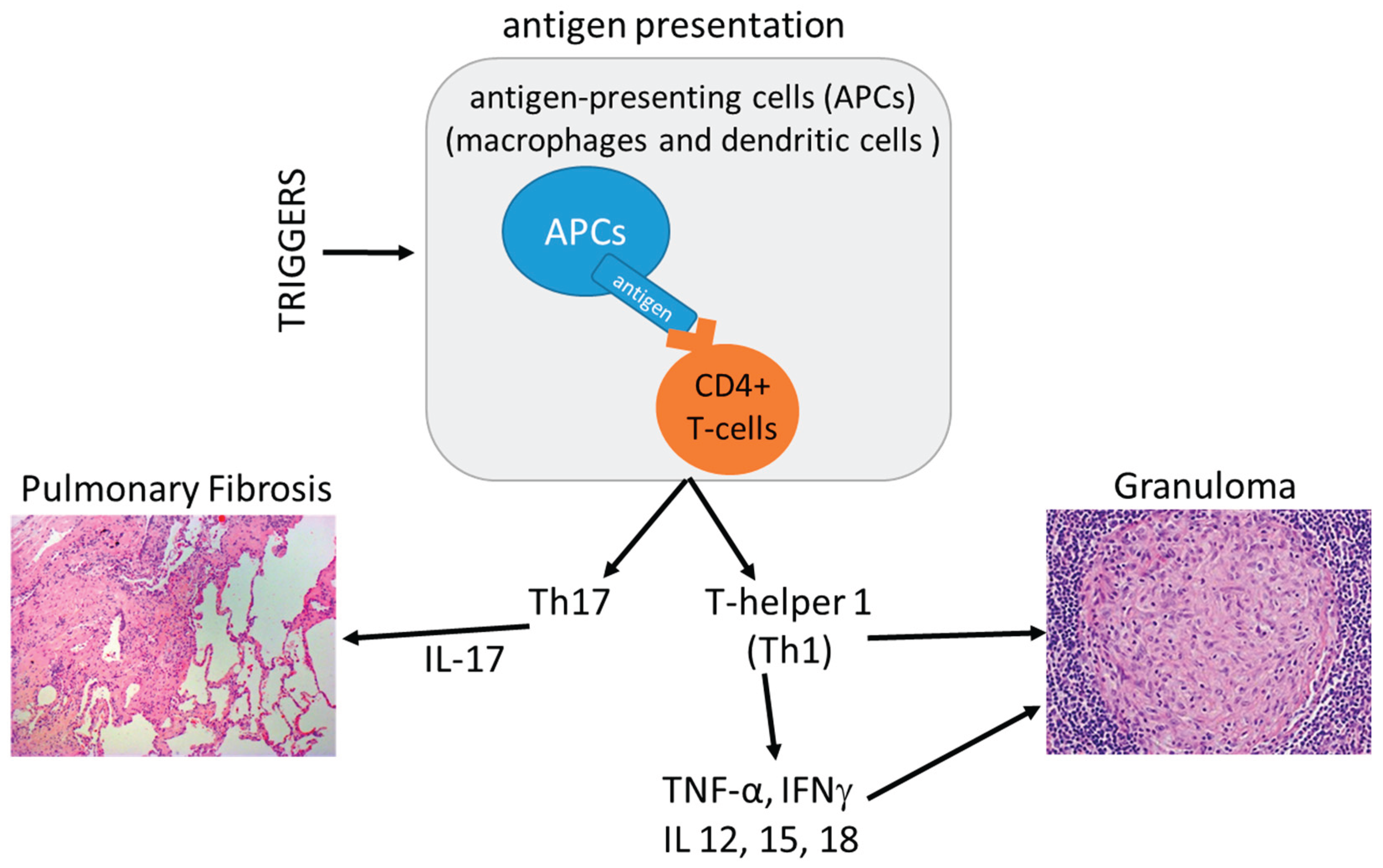

In recent years, evidence has suggested a role of T helper 17 (Th17) cells in sarcoidosis. Researchers have found that IL-17A-expressing CD4+ T lymphocytes or IL-17A+IFN-γ+ memory T cells and

RORγt, a nuclear receptor crucial for the differentiation of Th17 cells, are increased in both BAL and peripheral blood of patients with sarcoidosis [

69,

70]. IL-17A+ cells are also suggested to be persistently present in patients with sarcoidosis relapses [

71](

Figure 4).

In the model of IL-17A-knockout C57BL/6 mice, the heat-killed

C. acnes is able to induce sarcoidosis-like granulomas and pulmonary fibrosis. Wild-type mice with granulomatosis were treated with anti-IL-17A antibody and the administration of

C. acnes enhanced the expression of IL-17A, granulomatosis and fibrosis in mouse lungs after boost stimulation. Neither granuloma, nor fibrosis were observed in IL-17A-knockout mice, even in the presence of IFN-γ enhancement. Neutralizing IL-17A antibody reduced inflammatory cells in BAL fluid and ameliorated both granulomatosis and fibrosis in sarcoidosis mice. Then, IL-17A plays a critical role in

C. acnes-induced sarcoidosis-like inflammation in both granulomatosis inflammation and disease progression to pulmonary fibrosis [

72].

Immunologic mediated Th1 response produces non-necrotizing granulomas which can localize anywhere in the body, making sarcoidosis a systemic disease [

1]. The term “

C. acnes-associated sarcoidosis” is applied to cases in which

C. acnes is detected in granulomas via immunohistochemistry using the anti-

Propionibacterium acnes monoclonal antibody (PAB antibody). This antibody reacts with a species-specific lipoteichoic acid (LTA) of

C. acnes in sarcoid granulomas and it has been developed by mice immunization with the whole bacterial lysate followed by immunohistochemical screening of

C. acnes-specific antibody-producing hybridoma clones using FFPE sarcoid lymph nodes [

52]. PAB-antibody-positive Hamazaki-Wesenberg (HW) bodies (hypothesised to be cell-wall deficient forms of

C. acnes) were detected by these

C. acnes-specific antibodies which are mainly located in sinus macrophages of the lymph nodes; although they are not specific for sarcoid subjects, they are detected at a higher frequency in sarcoid

versus non-sarcoid lesions (50% of 119 subjects

versus 15% of 165 cases, respectively [

52]. Furthermore, the sarcoid specimen were shown to contain

C. acnes DNA in different studies [

73,

74] and even in lymph node samples from European subjects in an international study [

67], supporting the hypothesis of a causative connection between the two conditions. Overall, sarcoidosis can be considered an endogenous hypersensitivity infection, which develop only after the following three factors are established: 1) a latent infection by

C. acnes; 2) a reactivation of latent

C. acnes triggered by environmental factors; 3) a hypersensitive Th1 immune response against the intracellular

C. acnes as host factors.

The

C. acnes is the sole microorganism ever isolated from sarcoid lesions and activation of Th1 immune responses by

C. acnes is generally higher in sarcoidosis patients than in healthy individuals [

34,

75]. Some sarcoidosis subjects have increased amounts of

C. acnes-derived circulating immune complexes, which suggest proliferation of this bacterium in multiple affected organs [

76] (

Figure 3). Indeed, current trials in subjects with cardiac sarcoidosis are evaluating combined treatment with corticosteroids and antimicrobials during active disease with continued antimicrobial therapy while tapering off steroids after the disease subsides [

77].

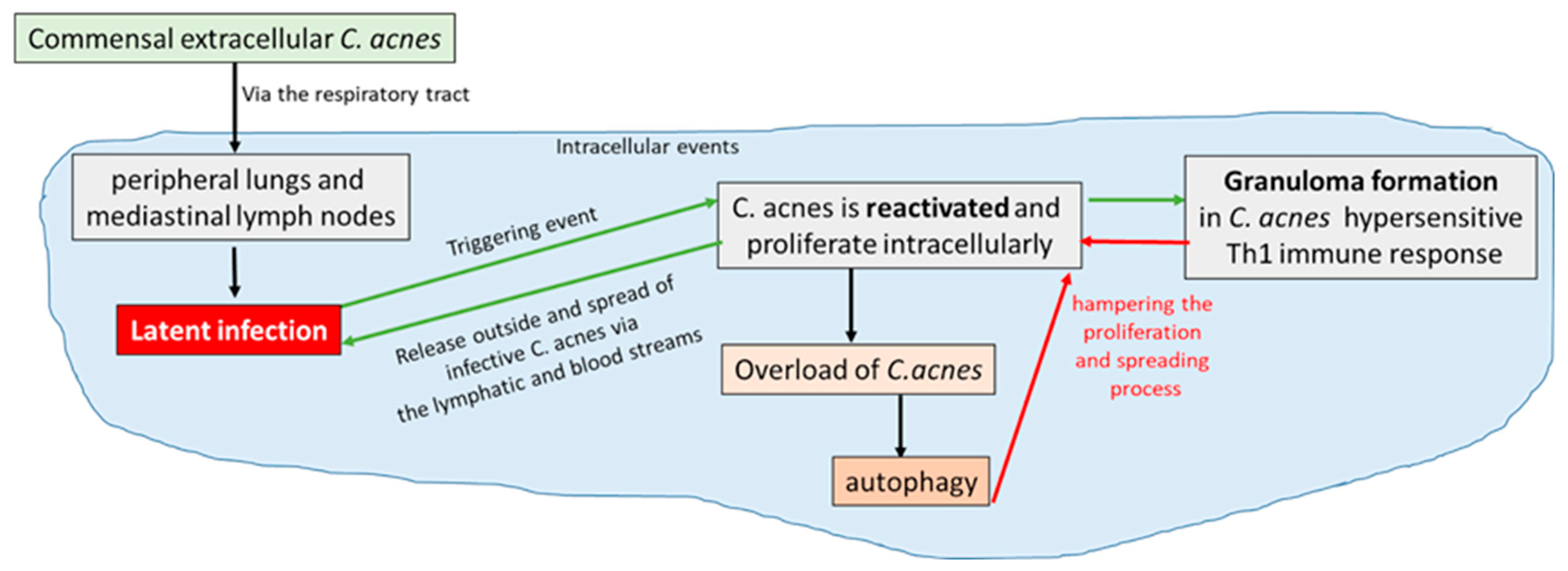

3.3. Aetiopathogenesis of Sarcoidosis: Which Role for Cutibacterium acnes?

C. acnes can be assumed to be one potential trigger of sarcoidosis. The pathogenesis of the process implies a first passage from being extracellular commensal to an intracellular latent infectious agent in peripheral lungs and mediastinal lymph nodes [

54]. The

in vitro model of persistence of

C. acnes in human blood cell phagocytes in a cellular and physiological environment can mimic the

in vivo situation [

78] in order to investigate the cellular processes during granuloma formation. In particular, the

C. acnes strain isolated from prosthetic joint infection (PJI) induced a higher recruitment of CD8+ lymphocytes inside the granuloma. In patients suffering from

C. acnes PJI, these lymphocytes, through their cytotoxic activity, may cause tissue damage leading to osteoclast activation and thereafter aseptic loosening of the prosthesis [

79], frequently observed during chronic and low-grade infections due to

C. acnes [

80]. In contrast, in acne-related sarcoidosis, a high recruitment of CD4+ lymphocytes is in accordance with previous studies, demonstrating the main role played by this specific lymphocyte subset [

81,

82]

. Interestingly, S8

C. acnes strain recovered from the lymph node of a sarcoidosis subject was particularly able to produce the highest number of granulomas. Moreover, the bacterial burden inside the granulomas was significantly higher with this strain. Based on its clinical origin, it has been supposed that strain S8 harbored several antigens leading to the formation of granulomatous structures [

83].

Indeed, the granuloma formation can be affected by

C. acnes catalase expression as this enzyme induces hypersensitive Th1 immune responses in sarcoidosis [

34,

84]. It has been reported that granuloma formation takes place only in predisposed individuals hypersensitive to

C. acnes through a Th1 immune response.

C acnes proliferating intracellularly can therefore be confined by the growing granuloma triggered by the bacterium and hampered by local autophagy processes, leading to a final resolution of the granulomatous inflammation and of the sarcoidosis process. The alternative fate occurs when

C. acnes escapes either the granulomatous confinement or the other host defence strategies, leading to the spreading of intracellular latent infection from the respiratory tract to other organs of the body through bloodstream, where reactivation by triggering events can cause systemic sarcoidosis [

54](

Figure 5).

4. Novel Therapeutic Options

C. acnes-related sarcoidosis has been treated with antimicrobial agents. There are several reports or small case-studies in which antibiotic treatment resulted in improved clinical symptoms [

86,

87]. When minocycline therapy was used, treatment discontinuation resulted in symptoms relapse; as tetracyclines have anti-inflammatory properties, these results have been interpreted as a consequence of an immunomodulatory effect rather than a true antimicrobial effect of the treatment [

86,

88]. In the same direction is the case-report of cutaneous sarcoidosis in a tattooed subject, showing improving symptoms after minocycline treatment [

89]. However, the immunohistochemistry detection of

C. acnes with PAB antibody on cutaneous sarcoidosis in a subject undergoing permanent makeup [

90], opens to the hypothesis that the antimicrobial action might play an important role in treating these

C.acnes-related sarcoidosis subjects.

The Japanese Antibacterial Drug Management for Cardiac Sarcoidosis (CS) (J-ACNES) trial showed interesting results of antimicrobial therapy

plus corticosteroid therapy compared to corticosteroid therapy alone in CS [

77]. The standard treatment of CS is lifelong corticosteroid therapy with the need to dose escalation in order to control inflammation worsening, with dose-dependent adverse effects. The use of corticosteroid sparing drugs such as methotrexate to contain adverse effects produced limited data so far [

91], making the use of antimicrobial an interesting option to be evaluated in these subjects.

The rationale for the J-ACNES trial was the identification of

C. acnes in sarcoid granulomas of myocardial tissues of CS subjects [

92] suggesting an etiologic role for

C. acnes in CS. The use of antimicrobial monotherapy was not effective against CS [

93]. In the J-ACNES trial a combination of antimicrobial drugs (clarithromycin 200-400 mg/day and doxycycline hydrochloride 100-200 mg/day) in addition to corticosteroid therapy was used for 6 months with a good safety profile, mimicking the clinical strategy of long-lasting drugs combination successfully used in other granulomatous diseases, such as tuberculosis and leprosy [

94]. The results of this trial are still under investigation and it will be interesting to evaluate them in the light of sarcoidosis pathogenesis. The PHENOSAR trial (use of antibiotics in treatment of sarcoidosis, NCT05291468) [

95] was initiated in the Netherlands during 2022 but the study has passed its completion date and study status has not been updated after two years. This trial represented the first based on a targeted therapy rationale in sarcoidosis, i.e. the presence of

C. acnes in the granulomatous tissues of sarcoidosis subjects. Two antibiotics were administered for 13-weeks, azithromycin and doxycycline, and the results were expected to be compared between placebo and treated groups; inflammation status was expected to be monitored by PET/CT-scan and serum biomarkers ACE and IL-2R. Unfortunately, nothing is known so far from this study and therefore the question whether the presence of

C. acnes in sarcoidosis patients might represent a successful strategy awaits further investigation.

5. Cutibacterium acnes, Sarcoidosis and Malignant Tumours

Chintalapati et al [

96] proposed that

C. acnes can be isolated from tumors, since the host-response to the microorganism resulted in an “immunologic hub” at the infected niches responsible for anti tumoral activity.

C. acnes has been used as immunostimulant adjuvant therapy for malignant tumors since the 70/80s; indeed, when injected as a heat- or formol-inactivated suspension, this bacterium induced immunomodulatory effects on both innate and adaptive immune responses. Its antitumoral activity has been demonstrated in murine models [

97];

C. acnes has also been used as a priming agent to enable host cells to respond efficiently to a pathogen attack [

98]. McCaskill et al. [

98] established an

in vivo model of

C. acnes-induced pulmonary inflammation, in which mice were intraperitoneally sensitized and intratracheally challenged with heat-killed

C. acnes. The study revealed a significant increase in leukocyte recruitment to the lung and cytokine production in comparison with both control and no sensitized but challenged mice.

This anti-tumor activity appears to be strain-specific, with certain C. acnes types exhibiting stronger effects than others. For example, C. acnes type I showed a higher survival rate in mice than type II [

99]

. Differences in the carbohydrate composition of the cell walls of different C. acnes strains may contribute to their varying immunological and biological activities, potentially influencing their anti-tumor properties [

100]

. Some C. acnes strains not only inhibit tumor growth but also inhibit the spread and growth of metastasized tumor cells [

101]

. Moreover, clinical trials have reported the use of

C. acnes in the treatment of various cancers (ovarian carcinoma, malignant melanoma, lung cancer, breast cancer), and the disease-free survival was shown to be significantly increased in patients who received this adjuvant therapy [

102]. Additionally, a recent study showed that tumor-isolated

C. acnes activated the immune system, and the immune cells effectively penetrated through the tumor tissue and formed an immunologic hub inside, explicitly targeting the tumor and destroying its cells [

103]. The anti-tumor activity was mainly attributed to a local stimulation of lymphokine production (IL-12, IFN-γ, TNF) resulting in T cells recruitment, proliferation, and their orientation toward a Th1 profile [

103,

104] as well as non-specific macrophage activation [

105] leading to tumor size regression.

These data are consistent with a recent investigation [

106] on 287 sarcoidosis outpatients assessed between 2000 and 2024; in this retrospective study the diagnosis of cancer was recorded in 36 subjects (12.5%). The cancer preceded sarcoidosis or sarcoid-like reactions in 63.8%, and the sarcoidosis accompanying the onset of malignancy was 27.8%, whereas the cancer arising after sarcoidosis diagnosis was only 8.3%. Only 2/36 subjects with sarcoidosis and cancer showed metastasis, and one of them was affected by lymphoma. These data suggest that granulomatous inflammation due to sarcoidosis represents a protective shield, preventing the formation of metastasis through the induction of immune surveillance against cancer, while, on the other hand, it can be a risk factor for lymphomagenesis due to the persistence of a chronic active inflammatory status [

106].

6. Future Directions of the Research and Treatment

A rational approach to treatment should include precision in etiologic and microbiological investigations with the ancillary aim of avoiding infectious complications of either corticosteroids or immunosuppressors; therefore, the use of a combination of antimicrobial agents and immune regulators in

C. acnes-related sarcoidosis subjects seems promising because of the clinical effects in limiting the use of corticosteroids. Indeed, as it is already a common practice in rheumatology to investigate the pre-existence of latent tuberculosis or persistent viral infections before steroid treatment or immunosuppression. Therefore, the coexistence or presence of

C. acnes as a trigger for sarcoidosis should recommend a preventive treatment before steroid treatment or immunosuppression. Since the nonspecific or multidrug therapy induces development of resistant strains (as rifampicin-resistant strains in leprosy treatment) [

107], according to personalized medicine, the typing of acne strains and the use of specific antibiograms should be used. This procedure has not yet become routinary, but reasonably it should be considered as a potentially fruitful clinical practice. Therefore, a combination of strategies that also take into account the etiology and pathogenesis could be the best approach to brake and restrain the granulomatous manifestations observed in subjects with sarcoidosis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.M. and A.M.D.F.; methodology, A.M.D.F.; software, A.M.D.F.; validation, A.M.D.F,; formal analysis, A.M.D.F.; investigation, G.P., E.V., L.L.S., L.G.; resources, R.M.; writing—original draft preparation, R.M. and A.M.D.F.; writing—review and editing, A.M.D.F.; visualization and supervision, D.R..; project administration, R.M.; funding acquisition, R.M.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

This research was funded by Fondazione Policlinico A. Gemelli IRCCS, grant number 5502162 and by the Research Center of Periodic Fevers of the Catholic University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank prof. A. Urbani and prof. L. Richeldi for their support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AMP |

Antimicrobial peptides |

| APC |

Antigen-presenting cell |

| CNS |

Central nervous system |

| D/PAMP |

Danger- or pathogen-associated molecular patterns |

| HA |

Hyaluronic acid |

| HYL |

Hyaluronate lyase |

| HW |

Hamazaki-Wesenberg |

| INF-γ |

Interferon-gamma |

| KAT |

Catalase |

| LTA |

Lipoteichoic acid |

| NLR |

NOD-like receptors |

| PAB |

P. acnes-specific monoclonal antibody |

| PRR |

Patterns recognition receptors |

| PCa |

Prostate cancer |

| PC |

Phosphatidylcholine |

| PG |

Prostaglandine |

| ROS |

Reactive oxygen species |

| SM |

Sphingomyelin |

| TLR |

Toll-like receptors |

| TNF |

Tumor necrosis factor |

References

- Brito-Zerón, P.; Pérez-Álvarez, R.; Ramos-Casals, M. Sarcoidosis. Med Clin 2022, 159, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekio, I.; Sugiura, Y.; Hamada-Tsutsumi, S.; Murakami, Y.; Tamura, H.; Suematsu, M. What Do We See in Spectra?: Assignment of High-Intensity Peaks of Cutibacterium and Staphylococcus Spectra of MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry by Interspecies Comparative Proteogenomics. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gajdács, M.; Spengler, G.; Urbán, E. Identification and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing of Anaerobic Bacteria: Rubik’s Cube of Clinical Microbiology? Antibiotics 2017, 6, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayslich, C.; Grange, P.A.; Dupin, N. Cutibacterium acnes as an Opportunistic Pathogen: An Update of Its Virulence-Associated Factors. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, G.S.; Pratt-Rippin, K.; Meisler, D.M.; Washington, J.A.; Roussel, T.J.; Miller, D. Growth Curve for Propionibacterium acnes. Curr Eye Res 1994, 13, 465–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.; Byrd, A. L.; Deming, C.; Conlan, S.; Kong, H.H.; Segre, J.A. Biogeography and individuality shape function in the human skin metagenome. Nature 2014, 514, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scharschmidt, T. C.; Vasquez, K. S.; Truong, H. A.; Gearty, S. V.; Pauli, M. L.; Nosbaum, A.; Gratz, I.K.; Otto, M.; Moon, J.J.; Liese, J.; Abbas, A.K.; Fischbach, M.A.; Rosenblum, M.D. A wave of regulatory t cells into neonatal skin mediates tolerance to commensal microbes. Immunity 2015, 43, 1011–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borkowski, A.W.; Gallo, R.L. The Coordinated Response of the Physical and Antimicrobial Peptide Barriers of the Skin. J Investig Dermatol 2011, 131, 285–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, J.B.; Assa, M.; Mruwat, N.; Sailer, M.; Regmi, S.; Kridin, K. Facultatively Anaerobic Staphylococci Enable Anaerobic Cutibacterium Species to Grow and Form Biofilms Under Aerobic Conditions. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell, A.; Valanne, S.; Ramage, G.; Tunney, M.M.; Glenn, J.V.; McLorinan, G.C.; Bhatia, A.; Maisonneuve, J.F.; Lodes, M.; Persing, D.H.; Patrick, S. Propionibacterium acnes types I and II represent phylogenetically distinct groups. J Clin Microbiol 2005, 43, 326–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidsson, S.; Soderquist, B.; Elgh, F.; Olsson, J.; Andren, O.; Unemo, M.; Mölling, P. Multilocus sequence typing and repetitive-sequence-based PCR (DiversiLab) for molecular epidemiological characterization of Propionibacterium acnes isolates of heterogeneous origin. Anaerobe 2012, 18, 392–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lomholt, H.B.; Kilian, M. Population genetic analysis of Propionibacterium acnes identifies a subpopulation and epidemic clones associated with acne. PLoS One 2010, 5, e12277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDowell, A.; Gao, A.; Barnard, E.; Fink, C.; Murray, P.I.; Dowson, C.G.; Nagy, I.; Lambert, P.A.; Patrick, S. A novel multilocus sequence typing scheme for the opportunistic pathogen Propionibacterium acnes and characterization of type I cell surface- associated antigens. Microbiology 2011, 157, 1990–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mak, T.N.; Yu, S.H.; De Marzo, A.M.; Bruggemann, H.; Sfanos, K.S. Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) analysis of Propionibacterium acnes isolates from radical prostatectomy specimens. Prostate 2013, 73, 770–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassi Fehri, L.; Mak, T.N.; Laube, B.; Brinkmann, V.; Ogilvie, L.A.; Mollenkopf, H.; Lein, M.; Schmidt, T.; Meyer, T.F.; Brüggemann, H. Prevalence of Propionibacterium acnes in diseased prostates and its inflammatory and transforming activity on prostate epithelial cells. Int J Med Microbiol 2011, 301, 69–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, M.; Wang, Y.; Yu, J.; Kuo, S.; Coda, A.; Jiang, Y.; Gallo, R.L.; Huang, C.M. Fermentation of Propionibacterium acnes, a commensal bacterium in the human skin microbiome, as skin probiotics against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS One 2013, 8, e55380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portillo, M. E.; Corvec, S.; Borens, O.; Trampuz, A. Propionibacterium acnes: an underestimated pathogen in implant-associated infections. Biomed Res Int 2013, 804391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidsson, S.; Molling, P.; Rider, J.R.; Unemo, M.; Karlsson, M.G.; Carlsson, J.; Andersson, S.O.; Elgh, F.; Söderquis, B.; Andrén, O. Frequency and typing of Propionibacterium acnes in prostate tissue obtained from men with and without prostate cancer. Infect Agent Cancer 2016, 11, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dréno, B.; Pécastaings, S.; Corvec, S.; Veraldi, S.; Khammari, A.; Roques, C. Cutibacterium acnes (Propionibacterium acnes) and Acne Vulgaris: A Brief Look at the Latest Updates. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2018, 32, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renz, N.; Mudrovcic, S.; Perka, C.; Trampuz, A. Orthopedic Implant-Associated Infections Caused by Cutibacterium spp.—A Remaining Diagnostic Challenge. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0202639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teramoto, K.; Okubo, T.; Yamada, Y.; Sekiya, S.; Iwamoto, S.; Tanaka, K. Classification of Cutibacterium acnes at phylotype level by MALDI-MS proteotyping. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B Phys Biol Sci 2019, 95, 612–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leheste, J.R.; Ruvolo, K.E.; Chrostowski, J.E.; Rivera, K.; Husko, C.; Miceli, A.; Selig, M.K.; Brüggemann, H.; Torres G., P. acnes-driven disease pathology: current knowledge and future directions. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2017, 7, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chudzik, A.; Bromke, M.A.; Gamian, A.; Paściak, M. Comprehensive lipidomic analysis of the genus Cutibacterium. mSphere 2024, 9, e0005424. [Google Scholar]

- Both, A.; Huang, J.; Hentschke, M.; Tobys, D.; Christner, M.; Klatte, T.O.; Seifert, H.; Aepfelbacher, M.; Rohde, H. Genomics of Invasive Cutibacterium acnes Isolates from Deep-Seated Infections. Microbiol Spectr 2023, 11, e0474022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersson, F.; Kilsgård, O.; Shannon, O.; Lood, R. Platelet activation and aggregation by the opportunistic pathogen Cutibacterium (Propionibacterium) acnes. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0192051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell, A.; Perry, A.L.; Lambert, P.A.; Patrick, S. A new phylogenetic group of Propionibacterium acnes. J Med Microbiol 2008, 57, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, O.; López-Lara, I.M; Sohlenkamp, C. Phosphatidylcholine biosynthesis and function in bacteria. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids 2013, 1831, 503–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozas, M.; Hart de Ruijter, A.; Fabrega, M.J.; Zorgani, A.; Guell, M.; Paetzold, B.; Brillet, F. From Dysbiosis to Healthy Skin: Major Contributions of Cutibacterium acnes to Skin Homeostasis. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heung, L.J.; Luberto, C.; Del Poeta, M. Role of Sphingolipids in Microbial Pathogenesis. Infect Immun 2006, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazipi, S.; Stødkilde, K.; Scavenius, C.; Brüggemann, H. The Skin Bacterium Propionibacterium acnes Employs Two Variants of Hyaluronate Lyase with Distinct Properties. Microorganisms 2017, 5, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell, A.; Nagy, I.; Magyari, M.; Barnard, E.; Patrick, S. The Opportunistic Pathogen Propionibacterium acnes: Insights into Typing, Human Disease, Clonal Diversification and CAMP Factor Evolution. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e70897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marion CStewart, J.M.; Tazi, M.F.; Burnaugh, A.M.; Linke, C.M.; Woodiga, S.A.; King, S.J. Streptococcus pneumoniae Can Utilize Multiple Sources of Hyaluronic Acid for Growth. Infect Immun 2012, 80, 1390–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schommer, N.N.; Muto, J.; Nizet, V.; Gallo, R.L. Hyaluronan Breakdown Contributes to Immune Defense against Group A Streptococcus. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2014, 289, 26914–26921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yorozu, P.; Furukawa, A.; Uchida, K.; Akashi, T.; Kakegawa, T.; Ogawa, T.; Minami, J.; Suzuki, Y.; Awano, N.; Furusawa, H.; Miyazaki, Y.; Inase, N.; Eishi, Y. Propionibacterium acnes catalase induces increased Th1 immune response in sarcoidosis patients. Respir Investig 2015, 3, 161–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayslich, C.; Grange, P.A.; Castela, M.; Marcelin, A.G.; Calvez, V.; Dupin, N. Characterization of a Cutibacterium acnes Camp Factor 1-Related Peptide as a New TLR-2 Modulator in In Vitro and Ex Vivo Models of Inflammation. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 5065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCaskill, J.G.; Chason, K.D.; Hua, X.; Neuringer, I.P.; Ghio, A.J.; Funkhouser, W.K.; Tilley, S.L. Pulmonary immune responses to propionibacterium acnes in C57bl/6 and BALB/ c mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2006, 35, 347–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spittaels, K.-J.; Van Uytfanghe, K.; Zouboulis, C.C.; Stove, C.; Crabb´e, A.; Coenye, T. Porphyrins produced by acneic Cutibacterium acnes strains activate the inflammasome by inducing K+ leakage. iScience 2021, 24, 102575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chronnell, C.M.; Ghali, L.R.; Ali, R.S.; Quinn, A.G.; Holland, D.B.; Bull, J.J.; Cunliffe, W.J.; McKay, I.A.; Philpott, M.P.; Müller-Röver, S. Human beta defensin-1 and -2 expression in human pilosebaceous units: upregulation in acne vulgaris lesions. J Invest Dermatol 2001, 117, 1120–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalis, C.; Gumenscheimer, M.; Freudenberg, N.; Tchaptchet, S.; Fejer, G.; Heit, A.; Akira, S.; Galanos, C. Freudenberg MA.Requirement for TLR9 in the immunomodulatory activity of Propionibacterium acnes. J Immunol 2005, 174, 4295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grange, P.A.; Chéreau, C.; Raingeaud, J.; Nicco, C.; Weill, B.; Dupin, N.; Batteux, F. Production of superoxide anions by keratinocytes initiates P. acnes-induced inflammation of the skin. PLoS Pathog 2009, 5, e1000527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girvan, R.C.; Knight, D.A.; O’loughlin, C.J.; Hayman, C.M.; Hermans, I.F.; Webster, G.A. MIS416, a non-toxic microparticle adjuvant derived from Propionibacterium acnes comprising immunostimulatory muramyl dipeptide and bacterial DNA promotes cross-priming and Th1 immunity. Vaccine 2011, 29, 545–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Ochoa, M.-T.; Krutzik, S.R.; Takeuchi, O.; Uematsu, S.; Legaspi, A.J.; Brightbill, H.D.; Holland, D.; Cunliffe, W.J.; Akira, S.; Sieling, P.A.; Godowski, P.J.; Modlin, R.L. Activation of toll-like receptor 2 in acne triggers inflammatory cytokine responses. J Immunol 2002, 169, 1535–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krutzik, S.R.; Tan, B.; Li, H.; Ochoa, M.T.; Liu, P.T.; Sharfstein, S.E.; Graeber, T.G.; Sieling, P.A.; Liu, Y.J.; Rea, T.H.; Bloom, B.R.; Modlin, R.L. TLR activation triggers the rapid differentiation of monocytes into macrophages and dendritic cells. Nat Med 2005, 11, 653–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, G.M.; Farrar, M.D.; Cruse-Sawyer, J.E.; Holland, K.T.; Ingham, E. Proinflammatory cytokine production by human keratinocytes stimulated with Propionibacterium acnes and P. acnes GroEL. Br J Dermatol 2004, 150, 421–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, E.-J.; Lee, H.G.; Bae, I-H.; Kim, W.; Park, J.; Lee, T.R.; Cho, E.G. Propionibacterium acnes-derived extracellular vesicles promote acne-like phenotypes in human epidermis. J Invest Dermatol 2018, 138, 1371–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoraval, L.; Varin-Simon, J.; Ohl, X.; Velard, F.; Reffuveille, F.; Tang-Fichaux, M. Cutibacterium acnes and its complex host interaction in prosthetic joint infection: Current insights and future directions. Res Microbiol 2025, 17, 104265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, C.; Iwai, K.; Mikami, R.; Hosoda, Y. Frequent isolation of Propionibacterium acnes from sarcoidosis lymph nodes. Zentralbl Bakteriol Mikrobiol Hyg A 1984, 256, 541–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homma, J.Y.; Abe, C.; Chosa, H.; Ueda, K.; Saegusa, J.; Nakayama, M.; Homma, H.; Washizaki, M, Okano. Bacteriological investigation on biopsy specimens from patients with sarcoidosis. Jpn J Exp Med 1978, 48, 251–5. [Google Scholar]

- Hiramatsu, J.; Kataoka, M.; Nakata, Y.; Okazaki, K.; Tada, S.; Tanimoto, M.; Eishi, Y. Propionibacterium acnes DNA detected in bronchoalveolar lavage cells from patients with sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 2003, 20, 197–203. [Google Scholar]

- Inoue, Y.; Suga, M. Granulomatous diseases and pathogenic microorganism. Kekkaku. 2008, 83, 115–30. [Google Scholar]

- Isshiki, T.; Homma, S.; Eishi, Y.; Yabe, M.; Koyama, K.; Nishioka, Y.; Yamaguchi, T.; Uchida, K.; Yamamoto, K.; Ohashi, K.; Arakawa, A.; Shibuya, K.; Sakamoto, S.; Kishi, K. Immunohistochemical Detection of Propionibacterium acnes in Granulomas for Differentiating Sarcoidosis from Other Granulomatous Diseases Utilizing an Automated System with a Commercially Available PAB Antibody. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negi, M.; Takemura, T.; Guzman, J.; Uchida, K.; Furukawa, A.; Suzuki, Y.; Iida, T.; Ishige, I.; Minami, J.; Yamada, T.; Kawachi, H.; Costabel, U.; Eishi, Y. Localization of propionibacterium acnes in granulomas supports a possible etiologic link between sarcoidosis and the bacterium. Mod Pathol 2012, 25, 1284–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akata, K.; Yamasaki, K.; Nemoto, K.; Ikegami, H.; Kawaguchi, T.; Noguchi, S.; Kawanami, T.; Fukuda, K.; Mukae, H.; Yatera, K. Sarcoidosis Associated with Enlarged Mediastinal Lymph Nodes with the Detection of Streptococcus gordonii and Cutibacterium acnes Using a Clone Library Method. Intern Med 2024, 63, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eishi, Y. Potential Association of Cutibacterium Acnes with Sarcoidosis as an Endogenous Hypersensitivity Infection. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungprasert, P.; Ryu, J.H.; Matteson, E.L. Clinical Manifestations, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Sarcoidosis. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes 2019, 3, 358–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inaoka, P.T.; Shono, M.; Kamada, M.; Espinoza, J.L. Host-microbe interactions in the pathogenesis and clinical course of sarcoidosis. J Biomed Sci 2019, 26, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grunewald, J.; Grutters, J.C.; Arkema, E.V.; Saketkoo, L.A.; Moller, D.R.; Müller-Quernheim, J. Sarcoidosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2019, 5, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybicki, B.A.; Iannuzzi, M.C.; Frederick, M.M.; Thompson, B.W.; Rossman, M.D.; Bresnitz, E.A.; Terrin, M.L.; Moller, D.R.; Barnard, J.; Baughman, R.P.; DePalo, L.; Hunninghake, G.; Johns, C.; Judson, M.A.; Knatterud, G.L.; McLennan, G.; Newman, L.S.; Rabin, D.L.; Rose, C.; Teirstein, A.S.; Weinberger, S.E.; Yeager, H.; Cherniack, R. ACCESS Research Group. Familial aggregation of sarcoidosis. A case-control etiologic study of sarcoidosis (ACCESS). Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001, 164, 2085–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossides, M.; Grunewald, J.; Eklund, A. Familial aggregation and heritability of sarcoidosis: a Swedish nested case−control study. Eur Respir J 2018, 52, 1800385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijnen, P.A.; Voorter, C.E.; Nelemans, P.J.; Verschakelen, J.A.; Bekers, O.; Drent, M. Butyrophilin-like 2 in pulmonary sarcoidosis: a factor for susceptibility and progression? Hum Immunol 2011, 72, 342–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolin, A.; Lahtela, E.L.; Anttila, V.; Petrek, M.; Grunewald, J.; van Moorsel, C.H.M.; Eklund, A.; Grutters, J.C.; Kolek, V.; Mrazek, F.; Kishore, A.; Padyukov, L.; Pietinalho, A.; Ronninger, M.; Seppänen, M.; Selroos, O.; Lokki, M.L. SNP Variants in Major Histocompatibility Complex Are Associated with Sarcoidosis Susceptibility-A Joint Analysis in Four European Populations. Front Immunol 2017, 8, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamilloux, Y.; Cohen-Aubart, F.; Chapelon-Abric, C.; Maucort-Boulch, D.; Marquet, A.; Pérard, L.; Bouillet, L.; Deroux, A.; Abad, S.; Bielefeld, P.; Bouvry, D.; André, M.; Noel, N.; Bienvenu, B.; Proux, A.; Vukusic, S.; Bodaghi, B.; Sarrot-Reynauld, F.; Iwaz, J.; Amoura, Z.; Broussolle, C.; Cacoub, P.; Saadoun, D.; Valeyre, D.; Sève, P. Groupe Sarcoïdose Francophone. Efficacy and safety of tumor necrosis factor antagonists in refractory sarcoidosis: A multicenter study of 132 patients. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2017, 47, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.B.; Byun, E.J.; Kim, H.S. Potential role of the microbiome in acne: a comprehensive review. J Clin Med 2019, 8, 987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inohara, N.; Nuñez, G. The NOD: a signaling module that regulates apoptosis and host defense against pathogens. Oncogene 2001, 20, 6473–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreira, L.O.; Zamboni, D.S. NOD1 and NOD2 Signaling in Infection and Inflammation. Front Immunol 2012, 3, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moller, D.R.; Rybicki, B.A.; Hamzeh, N.Y.; Montgomery, C.G.; Chen, E.S.; Drake, W.; Fontenot, A.P. Genetic, immunologic, and environmental basis of sarcoidosis. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2017, 14, S429–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eishi, Y.; Suga, M.; Ishige, I.; Kobayashi, D.; Yamada, T.; Takemura, T.; Takizawa, T.; Koike, M.; Kudoh, S.; Costabel, U.; Guzman, J.; Rizzato, G.; Gambacorta, M.; du Bois, R.; Nicholson, A.G.; Sharma, O.P.; Ando, M. Quantitative analysis of mycobacterial and propionibacterial DNA in lymph nodes of Japanese and European patients with sarcoidosis. J Clin Microbiol 2002, 40, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanabe, T.; Ishige, I.; Suzuki, Y.; Aita, Y.; Furukawa, A.; Ishige, Y.; Uchida, K.; Suzuki, T.; Takemura, T.; Ikushima, S.; Oritsu, M.; Yokoyama, T.; Fujimoto, Y.; Fukase, K.; Inohara, N.; Nunez, G.; Eishi, Y. Sarcoidosis and NOD1 variation with impaired recognition of intracellular Propionibacterium acnes. Biochim Biophys Acta 2006, 1762, 794–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragusa, F. Sarcoidosis and Th1 chemokines. Clin Ter 2015, 166, e72–6. [Google Scholar]

- Georas, S.N.; Chapman, T.J.; Crouser, E.D. Sarcoidosis and T-helper cells. Th1, Th17, or Th17.1? Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016, 193, 1198–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Qiu, L.; Wang, Y.; Aimurola, H.; Zhao, Y.; Li, S.; Xu, Z. The Circulating Treg/Th17 Cell Ratio Is Correlated with Relapse and Treatment Response in Pulmonary Sarcoidosis Patients after Corticosteroid Withdrawal. PLoS One 2016, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Zhao, M.; Li, Q.; Lu, L.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, T.; Tang, D.; Zhou, N.; Yin, C.; Weng, D.; Li, H. IL-17A Can Promote Propionibacterium acnes-Induced Sarcoidosis-Like Granulomatosis in Mice. Front Immunol 2019, 10, 1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishige, I.; Usui, Y.; Takemura, T.; Eishi, Y. Quantitative PCR of mycobacterial and propionibacterial DNA in lymph nodes of Japanese patients with sarcoidosis. Lancet 1999, 354, 120–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wei, Y.R.; Zhang, Y.; Du, S.S.; Baughman, R.P.; Li, H.P. Real-time quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction to detect propionibacterial ribosomal RNA in the lymph nodes of Chinese patients with sarcoidosis. Clin Exp Immunol 2015, 181, 511–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furusawa, H.; Suzuki, Y.; Miyazaki, Y.; Inase, N.; Eishi, Y. Th1 and Th17 immune responses to viable Propionibacterium acnes in patients with sarcoidosis. Respir Investig 2012, 50, 104–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchida, K.; Furukawa, A.; Yoneyama, A.; Furusawa, H.; Kobayashi, D.; Ito, T.; Yamamoto, K.; Sekine, M.; Miura, K.; Akashi, T.; Eishi, Y.; Ohashi, K. Propionibacterium acnes-Derived Circulating Immune Complexes in Sarcoidosis Patients. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishibashi, K.; Eishi, Y.; Tahara, N.; Asakura, M.; Sakamoto, N.; Nakamura, K.; Takaya, Y.; Nakamura, T.; Yazaki, Y.; Yamaguchi, T.; Asakura, K.; Anzai, T.; Noguchi, T.; Yasuda, S.; Terasaki, F.; Hamasaki, T.; Kusano, K. Japanese antibacterial drug management for cardiac sarcoidosis (J-ACNES): A multicenter, open-label, randomized, controlled study. J Arrhythmia 2018, 34, 520–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deknuydt, F.; Roquilly, A.; Cinotti, R.; Altare, F.; Asehnoune, K. An in vitro model of mycobacterial granuloma to investigate the immune response in brain- injured patients. Crit. Care Med 2013, 41, e254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landgraeber, S.; von Knoch, M.; Löer, F.; Brankamp, J.; Tsokos, M.; Grabellus, F.; Schmid, K.W.; Totsch, M. Association between apoptosis and CD4(+)/CD8(+) T-lymphocyte ratio in aseptic loosening after total hip replacement. Int J Biol Sci 2009, 5, 182–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portillo, M.E.; Salvadó, M.; Alier, A.; Sorli, L.; Martínez, S.; Horcajada, J.P.; Puig, L. Prosthesis failure within 2 years of implantation is highly predictive of infection. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2013, 471, 3672–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loke, W.S.; Herbert, C.; Thomas, P.S. Sarcoidosis: Immunopathogenesis and Immunological Markers. Int J Chronic Dis 2013, 2013, 928601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kistowska, M.; Meier, B.; Proust, T.; Feldmeyer, L.; Cozzio, A.; Kuendig, T.; Contassot, E.; French, L.E. Propionibacterium acnes promotes Th17 and Th17/Th1 responses in acne patients. J Invest Dermatol 2015, 135, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubin, G.G.; Ada Da Silva, G.; Eishi, Y.; Jacqueline, C.; Altare, F.; Corvec, S.; Asehnoune, K. Immune discrepancies during in vitro granuloma formation in response to Cutibacterium (formerly Propionibacterium) acnes infection. Anaerobe 2017, 48, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, K.; Uchida, K.; Furukawa, A.; Tamura, T.; Ishige, Y.; Negi, M.; Kobayashi, D.; Ito, T.; Kakegawa, T.; Hebisawa, A.; Awano, N.; Takemura, T.; Amano, T.; Akashi, T.; Eishi, Y. Catalase expression of Propionibacterium acnes may contribute to intracellular persistence of the bacterium in sinus macrophages of lymph nodes affected by sarcoidosis. Immunol Res 2019, 67, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakhamuru, S.; Kambampati, S.; Wasim, S.; Kukkar, V.; Malik, B.H. The Role of Propionibacterium acnes in the Pathogenesis of Sarcoidosis and Ulcerative Colitis: How This Connection May Inspire Novel Management of These Conditions. Cureus 2020, 2020 12, e10812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, E.; Ando, M.; Fukami, T.; Nureki, S.I.; Eishi, Y.; Kumamoto, T. Minocycline for the treatment of sarcoidosis: Is the mechanism of action immunomodulating or antimicrobial effect? Clin Rheumatol 2008, 27, 1195–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takemori, N.; Nakamura, M.; Kojima, M.; Eishi, Y. Successful treatment in a case of Propionibacterium acnes-associated sarcoidosis with clarithromycin administration: A case report. J Med Case Rep 2014, 8, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachelez, H.; Senet, P.; Candranel, J.; Kaoukhov, A.; Dubertret, L. The use of tetracyclines for the treatment of sarcoidosis. Arch Dermatol 2001, 137, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheu, J.; Saavedra, A.P.; Mostaghimi, A. Rapid response of tattoo-associated cutaneous sarcoidosis to minocycline: case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Online J 2014, 20, 13030/qt6dd1m2j9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirai, Y.; Hamada, Y.; Sasaki, S.; Suzuki, M.; Ito, Y.; Katayama, K.; Uno, H.; Nakada, T.; Kitami, Y.; Uchida, K.; Eishi, Y.; Sueki, H. Sarcoidosis and sarcoidal foreign body reaction after permanent eye makeup application: Analysis by immunohistochemistry with commercially available antibodies specific to Cutibacterium acnes and Mycobacteria. J Cutan Pathol 2022, 49, 651–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagai, S.; Yokomatsu, T.; Tanizawa, K.; Ikezoe, K.; Handa, T.; Ito, Y.; Ogino, S.; Izumi, T. Treatment with methotrexate and low-dose corticosteroids in sarcoidosis patients with cardiac lesions. Intern Med 2014, 53, 427–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asakawa, N.; Uchida, K.; Sakakibara, M.; Omote, K.; Noguchi, K.; Tokuda, Y.; Kamiya, K.; Hatanaka, K.C.; Matsuno, Y.; Yamada, S.; Asakawa, K.; Fukasawa, Y.; Nagai, T.; Anzai, T.; Ikeda, Y.; Ishibashi-Ueda, H.; Hirota, M.; Orii, M.; Akasaka, T.; Uto, K.; Shingu, Y.; Matsui, Y.; Morimoto, S.I.; Tsutsui, H.; Eishi, Y. Immunohistochemical identification of Propionibacterium acnes in granuloma and inflammatory cells of myocardial tissues obtained from cardiac sarcoidosis patients. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0179980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiraga, Y.; Omichi, M.; Yamada, G. The effect of antibacterial drug for sarcoidosis. Ministry of Health and Welfare specific disease diffuse lung disease research team research report. 1995, 174–5. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, C.S.; Aerts, A.; Saunderson, P.; Kawuma, J.; Kita, E.; Virmond, M. Multidrug therapy for leprosy: a game changer on the path to elimination. Lancet Infect Dis 2017, 17, e293–e297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraaijvanger, R.; Veltkamp, M. The Role of Cutibacterium acnes in Sarcoidosis: From Antigen to Treatable Trait? Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chintalapati, S.S.V.V.; Iwata, S.; Miyahara, M.; Miyako, E. Tumor-isolated Cutibacterium acnes as an effective tumor suppressive living drug. Biomed Pharmacother 2024, 170, 116041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, J.D.; Sutton, R.C.; Conley, F.K. Effect of intracerebrally injected Corynebacterium parvum on the development and growth of metastatic brain tumor in mice. Neurosurgery 1989, 25, 709–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCaskill, J.G.; Chason, K.D.; Hua, X.; Neuringer, I.P.; Ghio, A.J.; Funkhouser, W.K.; Tilley, S.L. Pulmonary immune responses to propionibacterium acnes in C57bl/6 and BALB/ c mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2006, 35, 347–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berek, J.S.; Cantrell, J.L.; Lichtenstein, A.K.; Hacker, N.F.; Knox, R.M.; Nieberg, R.K.; Poth, T.; Elashoff, R.M.; Lagasse, L.D.; Zighelboim, J. Immunotherapy with biochemically dissociated fractions of Propionibacterium acnes in a murine ovarian cancer model. Cancer Res 1984, 44, 1871–1875. [Google Scholar]

- Roszkowski, W.; Ko, H.L.; Szmigielski, S.; Jeljaszewicz, J.; Pulverer, G. The correlation of susceptibility of different Propionibacterium strains to macrophage killing and antitumor activity. Med. Microbiol. Immunol 1980, 169, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, H.; Tsuchida, T.; Tsuji, Y.; Hamaoka, T. Preventive effect of Propionibacterium acnes on metastasis in mice rendered tolerant to tumor-associated transplantation antigens. GANN Jpn. J. Cancer Res 1980, 71, 692–698). [Google Scholar]

- Chintalapati, S.S.V.V.; Iwata, S.; Miyahara, M.; Miyako, E. Tumor-isolated Cutibacterium acnes as an effective tumor suppressive living drug. Biomed Pharmacother 2024, 170, 116041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuda, K.; Yamanaka, K.; Linan, W.; Miyahara, Y.; Akeda, T.; Nakanishi, T.; Kitagawa, H.; Kakeda, M.; Kurokawa, I.; Shiku, H.; Gabazza, E.C. , Mizutani, H. Intratumoral injection of Propionibacterium acnes suppresses malignant melanoma by enhancing Th1 immune responses. PLoS One 2011, 6, e29020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talib, W.H.; Saleh, S. Propionibacterium acnes Augments Antitumor, Anti-Angiogenesis and Immunomodulatory Effects of Melatonin on Breast Cancer Implanted in Mice. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0124384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanning, M.M.; Kazura, J.W. Lack of biological significance of in vitro Brugia malayi microfilarial cytotoxicity mediated by Propionibacterium acnes ("Corynebacterium parvum")-and Mycobacterium bovis BCG-activated macrophages. Infect Immun 1986, 52, 534–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Francesco, A.M.; Pasciuto, G.; Verrecchia, E.; Sicignano, L.L.; Gerardino, L.; Massaro, M.G.; Urbani, A.; Manna, R. Sarcoidosis and Cancer: The Role of the Granulomatous Reaction as a Double-Edged Sword. J Clin Med 2024, 13, 5232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ma, Y.; Li, G.; Jin, G.; Xu, L.; Li, Y.; Wei, P.; Zhang, L. Leprosy: treatment, prevention, immune response and gene function. Front Immunol 2024, 15, 1298749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).