Highlights

Chronological age is a main factor for progressive phenotypes in multiple sclerosis (MS) patients, however there is a heterogeneity in prognosis that could be influenced by biological age.

Leukocyte telomere length and epigenetic clocks are well-recognized somatic markers for biological aging and seem to be associated with disability progression in MS.

Immunosenescence pathways could contribute to MS progressive course and loss of efficacy of disease treatments. Evidence with senomorphic and senolytic drugs is still scarce but is growing and it could be considering a potential therapy for MS in the future.

Lifestyle changes could modulate biological age and hypothetically impact on MS course. Research must go further on this possibility.

1. Introduction

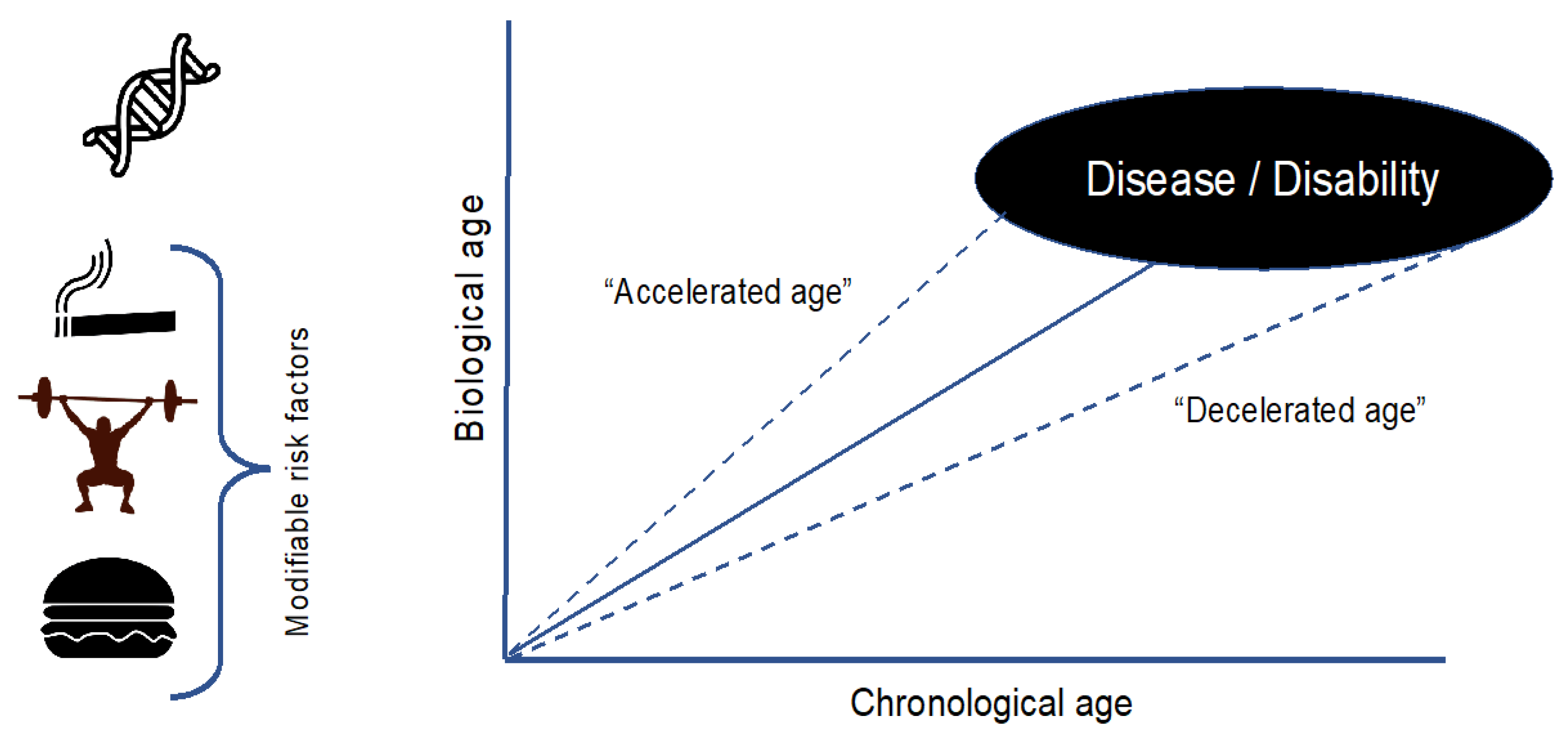

Chronological age (C-Age), determined by the time elapsed since the birth of an individual, is one of the main risk factors for the development of neurodegenerative diseases and for their prognosis [

1]. However, there is still a great heterogeneity in the clinical outcomes despite the classical concept of age [

2]. In this context, in the last years is gaining ground the concept of biological age (B-Age). B-Age is a less well-defined parameter that measures tissue damage, functional reserve capacity and regenerative potential [

3]. This aspect is determined by genetic factors but also, modifiable by lifestyle habits, which translate that aging is a “plastic” phenomenon (

Figure 1) [

4]. According to B-Age, an individual can show an “accelerated” or “decelerated” aging in comparison to C-Age which influences and modulates the risk of developing a disease or the disease course [

4].

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a disease with a broad clinical phenotype, where some patients acquire an early disability and others remain progression free for the rest of their lives. There are well-known radiological and clinical prognostic factors that impact on the disease course, and C-Age seems to be also determinant. However, once again, individuals of the same age show a significant heterogeneity in the disease course despite sharing similar baseline prognostic factors. A hypothetical explanation to, at least part of this disparity, lies in the individual B-Age. This article reviews the significance of C-Age in MS and the growing relevance of B-Age in this neurodegenerative disease.

2. Impact of Chronological Age on Multiple Sclerosis

C-Age is a high impact factor on the incidence of MS. The highest incidence rate appears between 20 and 40 years of age, although the disease can onset at any age of lifespan [

5]. Approximately, 2-5% of patients have a pediatric disease (under 17 years) [

6] and an estimated 8-10% of patients debut over 50 years of age, which is called "late onset" [

7]. These two populations of MS patients show a significantly different clinical phenotype. In between these two extremes, there is a continuum of intermediate course trajectories.

Meanwhile pediatric MS patients evolves almost exclusively with a relapsing course, older patients carry a higher risk of developing progressive disease phenotypes with a lower annualized relapsing rate [

8,

9,

10]. Also, it is well known, that children with relapsing MS onset take longer to reach a progressive phase of disease in comparison to adults, however this occurs at a younger age [

8]. That means that patients with a history of pediatric MS accumulate physical and cognitive disability at a younger age than patients with adult MS onset [

11,

12]. In addition, the average age at diagnosis of progressive MS in adults is 10 years older than that of relapsing forms, and age at onset of progression is highly similar between primary progressive and secondary progressive disease [

13,

14,

15]. On the opposite, older patients experience shorter latency to progression and are more likely to experience incomplete disability recovery following relapses [

16]. These observations suggest a strong relationship between C-Age and disability progression. On the other hand, it is well known that some MS patients remain free of disability progression until older ages, or even progression free. This suggest that C-Age is just a key player but not the only one and that there are other aspects influencing progressive phenotypes.

3. Biological Age in Multiple Sclerosis: What We Know

Aging is a natural process primarily caused by a progressive accumulation of deleterious changes to the normal metabolism at a molecular, cellular, and tissue levels, exacerbated by environmental toxics and unhealthy lifestyles. These damages finally act on the tissue functions and tissue capacity of regeneration. The “functionality” of tissues and organs is what we name B-Age. Defining a patient's biological age may offer more precision in determining the role of aging process than C-Age. Scientific evidence supports this statement in different diseases such as breast cancer [

17]

but also in stroke and neurodegenerative disease like dementia [

18,

19]

.

A recent meta-analysis of 13 cohorts found that epigenetic changes in DNA, one of the main process that drives B-Age, predicts all-cause of mortality, independent of C-Age and even after adjusting for traditional risk factors [

20]. Another recent systematic review and meta-analysis have observed that epigenetic alterations were

significantly related to mortality of cardiovascular disease, cancer and diabetes [

21]

.

B-Age can be estimated through different measurement strategies. Biomarkers corresponding to metabolic activity or inflammation correlate with biological functions rather than C-Age and therefore might predict the functional capacity of a tissue or organ. Three main system measures have been proposed: telomere-length (TL), epigenetic-clocks and biomarker-composites. However, a single best measure of biological aging does not exist. Several authors have studied the correlation between these different techniques with not conclusive results [

22]. A possible explanation to this disparity it that TL, the diverse proposed epigenetic clocks and biomarker-composites reflect different molecular hallmarks of aging and each of them may have its own strengths in the analysis of disease-specific mechanisms [

23].

3.1. Telomere-Length

Telomeres are protein structures and nucleotide repeats (TTAGGG) localized at the edge of chromosomes. They shorten with each cell division and

are necessary for the stability and protection of genomic DNA [

24,

25].

Telomeres are involved in signaling pathways that regulate cell proliferation, thus establishing the lifespan of a cell. Hence, they are considered biological clocks that determine the number of divisions that a cell undergoes [

26]

. In this process, it is essential the function of the telomerase enzyme, a ribonucleoprotein that helps in the maintenance of the telomere length. The activity of the telomerase enzyme is limited in most somatic cells, causing the telomeres to shorten, which finally leads to replicative senescence, an irreversible arrest of the cell cycle which is a main mechanism underlying aging. Evidence points out that besides C-Age, certain lifestyle factors such as smoking, obesity, inactivity, and unhealthy diet can increase the pace of telomere shortening [

27] as well as chronic inflammation and oxidative damage which may compromise the cellular functions [

28].

Several studies support the association between telomere length (TL) with cardiovascular diseases [

29], dementia [

30], and autoimmune diseases such as lupus or arthritis rheumatoid [

31]. Relation between telomere length and MS have also been explored. A systematic review [

32] analyzed 6 studies and found that four of them [

33,

34,

35,

36] reported significantly shorter leukocyte’s telomere length, and observed differences compared to healthy controls (

p=0.003 in meta-analysis). In this review, shorter telomeres in patients with MS were found to be associated, independently of age, with greater disability, lower brain volume, increased relapse rate and more rapid conversion from relapsing to progressive MS. This systematic review highlighted that people with MS typically have shorter telomeres in blood cells as compared to controls and it has been argued that the measurement of TL may serve as a potential biomarker for assessing and predicting clinical phenotypes of MS [

32].

In recent years, various articles have been published attempting to link telomere length with the risk of developing multiple sclerosis through Mendelian randomization analysis. To date, the results are controversial, as two of the studies have shown an association between shorter telomere length and a higher risk of MS [

37,

38], while a third study describes longer telomere length as being associated with an increased risk [

39]. It is necessary to delve deeper into the pathogenic mechanism of telomere length and its possible relationship with the risk of developing MS.

3.2. Epigenetic Clocks

Another biomarker of B-Age is related to the critical role that epigenetic changes play in aging. There are a huge number of B-Age measurements systems called “epigenetic clocks” based on methylation patterns in different DNA regions [

40]. This DNA methylation (DNAm) refers to heritable but modifiable mechanisms of genetic regulation that represent an interface for environmental and genetic factors to influence the genome. Multiple types of epigenetic clocks have been created to express B-age in healthy individuals and those living with chronic illness such as MS. The discrepancy between DNAm age and C- Age is determined by regressing the epigenetic age on C-age and is termed epigenetic age acceleration (EAA).

One of these epigenetic clocks called “PhenoAge” was compared with other 3 measures of epigenetic changes using blood samples from individuals diagnosed with MS [

41]. This study showed that the different measures reflect separate pathophysiological aspects of the disease and that people with MS have significantly higher EAA than healthy controls when evaluating DNAm PhenoAge in whole blood, independently of body mass index or smoking. Other study [

42] have observed that epigenetic age is accelerated in glial cells from brain tissue samples of MS participants compared with healthy controls.

The most recent epigenetic clock, the GrimAge clock, has been used to assess EAA in 583 MS patients in comparison to 643 non-MS controls. In this study The MS group exhibited an EAA increase of 5.1 years in cases with MS compared with controls [

43].

These collective data suggest that according to epigenetic changes aging is accelerated in MS and may contribute to the pathology and disability severity.

3.3. Biomarker-Composites

In contrast to TL or epigenetic clocks, multi-biomarker approaches have been shown to be easily available measures of B-Age. They capture the global effects related to aging processes in multiple organ systems [

44]. These multi-marker approaches have been successful in predicting mortality and estimating risk for aging related diseases, including cardiovascular disease [

44].

The 10-item US National Health and Nutritional Survey (NHANES) multimarker index of biological age is a composite measure based on the analysis from every patient of specific biological and clinical data: creatinine, C-reactive protein, blood-urea nitrogen, albumin, alkaline phosphatase, cholesterol, CMV IgG, hemoglobin A1c, Forced Expiratory Volume in 1-sec (FEV1) and blood pressure. This multimarker index has been tested in 51 MS patients [

45] finding that MS participants were biologically older than their age-matched controls.

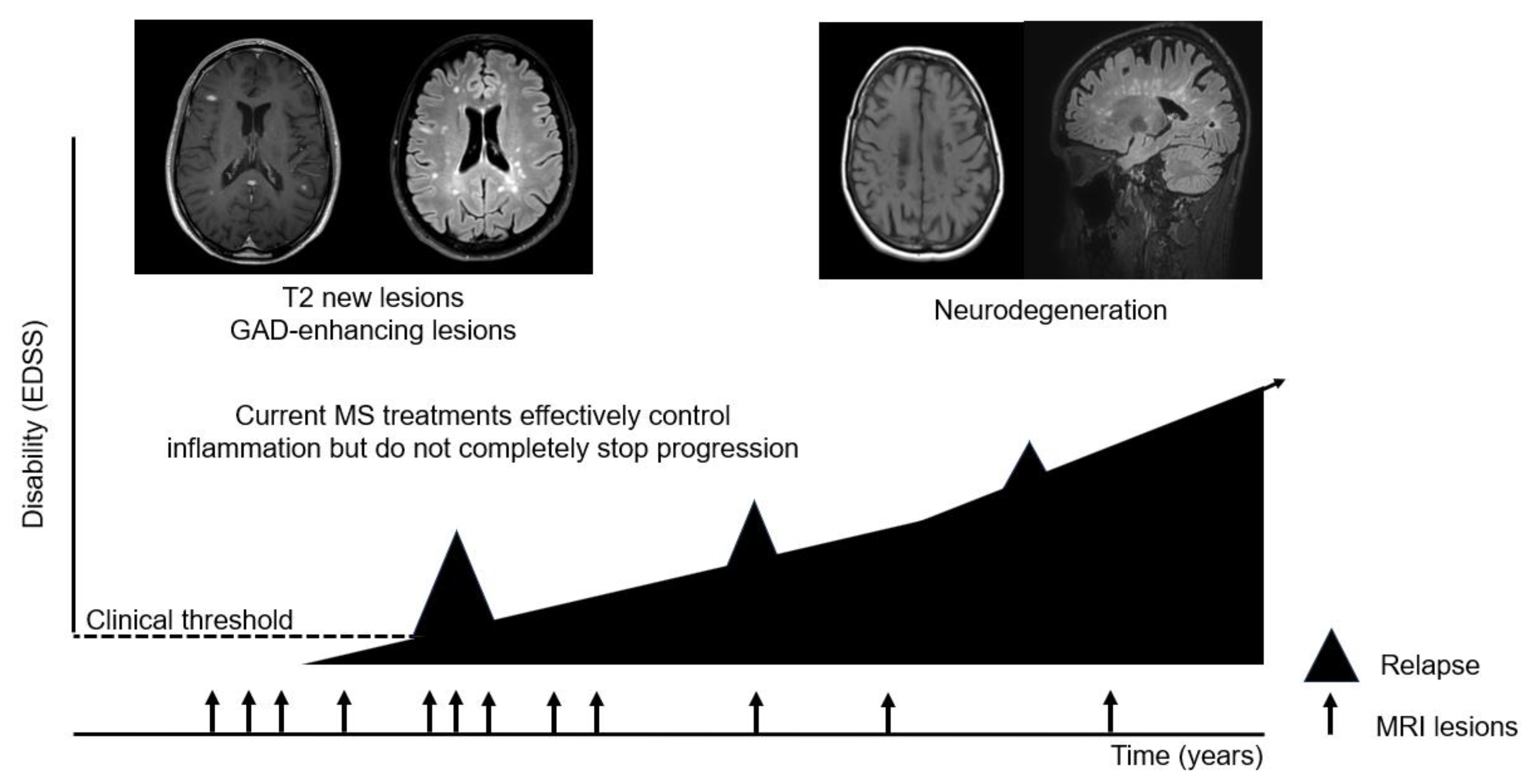

4. MS Progression and Aging

Although clinical progression often manifests later in life and with longer disease MS duration, there is a growing body of evidence demonstrating that neurodegeneration and progression occurs from disease onset [

46]. This means that neurodegenerative mechanisms are active much before the occurrence of the clinical progressive course and gradually become more evident by growing older (

Figure 2). From a clinical point of view, and to date, the main aspects that clinicians take into account when evaluating the prognostic risk of a given patient are radiological parameters and some biological and demographic baseline data [

47]. They are useful, but not enough to well classify patients and understand the heterogenic trajectories of progression. There should be additional aspects that influence the disease progression phenomenon, a fact that run in parallel with the fact of turning years.

During the natural aging process, the immune system undergoes drastic changes in composition and functionality. This process, called immune senesce, results in reduced adaptive immune response, increased susceptibility to infections and increased non organ-specific autoantibody production [

48]. Senescent cells are broadly characterized by cell cycle arrest and apoptotic resistance. Most cells undergoing senescence develop a senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) characterized by the production of catabolic factors [

49]. Independent of age, senescence can be induced in response to a variety of stimuli, including telomere attrition, oncogenes, and cell stress (e.g., oxidative, genotoxic, cytokines), which can contribute to SASP activation and senescence transformation [

49]. These phenotypic changes culminate in systemic inflammation, loss of regenerative capacity, favoring an ultimately tissue degeneration. In MS patients senescence have a doble effect, in the periphery and in the central nervous system, resulting in reduced adaptive immune response, reduced capacity of remyelination and tissue reparation, reduced efficacy of disease modyfing treatments and increase the risk of treatment side effects such as infections [

50,

51].

5. Senomorphic and Senolityc Drugs in Multiple Sclerosis

Improving the understanding of relationship between aging and MS progression is important because targeting aging-related mechanisms could be a potential therapeutic strategy for MS.

Senotherapy is an emerging field of research for the development of possible treatments and strategies specifically targeting cellular senescence. There are currently more than 30 compounds that target senescence pathways [

52]. One of them, the senomorphics, modulate cellular senescence through suppression of SASP without causing apoptosis. Senomorphics can be divided into several subtypes based on mechanism of action including mitochondrial antioxidants, Wnt/B-catenin inhibitors, JAK inhibitors, sirtuin regulators, mTOR inhibitors, or AMPK activators [

53]. There are multiple studies in EAE, the experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis mouse model of MS, that show that these compounds alleviated clinical disease and decreased demyelination [

51,

52,

53,

54]. In MS patients there are few early-phase clinical trials with senomorphics drugs, most of them with unreported data and just some in progressive forms without clear conclusions [

54].

Another class of therapeutics commonly used to target senescence pathways are senolytics. Senolityc are drugs that selectively initiated apoptosis in senescent cells by inhibiting the pro-survival mechanisms upregulated during senescence. These upregulated pathways were discovered by bioinformatics and transcriptomics of senescent cells developing different generations of senolytic drugs [

58]. Currently there are not senolityc clinical trials in MS. To the best of our knowledge, there are 2 ongoing recruiting phase II clinical trials in other neurodegenerative disease such an Alzheimer disease with the drug combination of dasatinib and quercetin [

59]. In EAE, there is just one report [

60] with a senolytic called BCL2 inhibitor, Navitoclax, that significantly reduced the presence of senescent microglia in the EAE model. This treatment had an effect on EAE mice, decreasing motor symptoms severity, improving visual acuity, promoting neuronal survival, and decreasing white matter inflammation.

Disease-modifying treatments currently in use for MS are immunomodulatory and immunosuppressive medications aiming to protect the CNS from immune-mediated damage. There is an urgent unmet need for neuroprotective strategies. Emerging in vitro and preclinical data in other disease suggest that targeting cellular senescence may promote repair, remyelination and neuroprotection and this also could work for MS and other demyelinating disease. However, evidence of its effectiveness is still in its infancy, as is evidence of its potential toxicity. For example, dasatinib, is a senolytic EMA approved drug [

61] for treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia and lymphoblastic leukemia, which has been related to the development of adverse effects such as cytopenias or pleural effusion. The toxicity of this drugs in MS needs to be stablished.

6. Lifestyle Habits and Biological Age

As we have previously described, B-Age is influenced by genetic factors and, what is more valuable, by modifiable factors such as lifestyle (

Figure 1).

Among these factors, there is scientific evidence on how physical exercise, smoking or obesity impact biological age markers in healthy people.

Studies of the relationship between telomeres and exercise have described a high telomerase activity and a reduced rate of telomere attrition in endurance athletes, compared to inactive controls [

62]. Also, it is reported that telomere length shortening can be reduced with moderate levels of physical activity, compared to inactivity in healthy people [

60]. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis suggested that the type of exercise is relevant and found that a high-intensity interval training have a higher positive effect on telomere length compared with other types of exercise such as resistance training or aerobic exercise in a healthy population [

64]. The positive effect of exercise have also been observed on other B-Age markers as epigenetic clocks [

65].

Smoking increases oxidative DNA damage and thus influences telomere shortening. A meta-analysis including 30 studies confirmed significantly shorter TL in peripheral blood cells among ever smokers compared to never smokers and among current smokers compared to former smokers in people without other pathology [

66].

Obesity in childhood and adolescence is a significant risk factor for MS and is partly a consequence of unhealthy eating behavior and sedentary lifestyle. A recent systematic review of 16 articles [

67] found a

negative association between childhood obesity and TL.

However, the interplay of physical activity, smoking or obesity and B-Age among patients with MS has not been elucidated. Additional prospective research is needed to clearly define how lifestyle changes can slow down disease progression.

7. Conclusion and Final Remarks: Unveiling the Future Directions

The influence of age and aging on the MS course has been highlighted since the early epidemiological studies. Notably in the last years a growing evidence suggest that the speed and way of aging could modulate the speed of MS progression and the relevance of biological age is growing in MS and other age-related diseases.

The measurement of biological age, however, faces several problems. Firstly, the techniques used are not easily accessible and there is a low agreement between their results. Secondly, the use of drugs whose objective is to reverse senescence is very far from showing significant efficacy in patients with MS and other neurodegenerative diseases.

The speed of aging can be influenced, at least in part, by our lifestyle, a modifiable issue. On the other hand, current approved therapies for MS do not stop progression, and the elderly MS population is increased in our centers. We need to generate evidence about the impact that a healthy lifestyle, an affordable “add-on therapy” for all patients, has on biological age, aging and hypothetically on disability progression in MS patients.

References

- Jylhävä J, Pedersen NL, Hägg S. Biological Age Predictors. EBioMedicine. 2017 Jul;21:29-36. [CrossRef]

- Lowsky DJ, Olshansky SJ, Bhattacharya J, Goldman DP. Heterogeneity in healthy aging. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2014;69:640–649. [CrossRef]

- Khan SS, Singer BD, Vaughan et DE. Molecular and physiological manifestations and measurement of aging in humans. Aging Cell 2017, 16, 624–633. [CrossRef]

- Rae MJ, Butler RN, Campisi J et al. The demographic and biomedical case for late-life interventions in aging. Sci Transl Med. 2010 Jul 14;2(40):40cm21. [CrossRef]

- Browne P, Chandraratna D, Angood C, et al.Atlas of Multiple Sclerosis 2013: A growing global problem with widespread inequity. Neurology2014; 83: 1022–4. [CrossRef]

- Krupp LB, Tardieu M, Amato MP, et al.International Pediatric Multiple Sclerosis Study Group criteria for pediatric multiple sclerosis and immune-mediated central nervous system demyelinating disorders: revisions to the 2007 definitions. Mult Scler2013; 19: 1261–7. [CrossRef]

- Solaro C, Ponzio M, Moran E, et al. The changing face of multiple sclerosis: prevalence and incidence in an aging population. Mult Scler 2015;21:1244–50. [CrossRef]

- Renoux C, Vukusic S, Mikaeloff Y, Edan G, Clanet M, Dubois B, et al. Natural history of multiple sclerosis with childhood onset. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2603–13. [CrossRef]

- Stankoff B, Mrejen S, Tourbah A et al. Age at onset determines the occurrence of the progressive phase of multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2007 Mar 6;68(10):779-81. [CrossRef]

- Scalfari A, Lederer C, Daumer M, et al. The relationship of age with the clinical phenotype in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2016; 22: 1750–1758. [CrossRef]

- Ghezzi A, Deplano V, Faroni J et al. Multiple sclerosis in childhood: clinical features of 149 cases. Mult Scler. 1997 Feb;3(1):43-6. [CrossRef]

- Simone IL, Carrara D, Tortorella C et al. Course and prognosis in early-onset MS: comparison with adult-onset forms. Neurology. 2002 Dec 24;59(12):1922-8.

- Sanai SA, Saini V, Benedict RH et al. Aging and multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2016 May;22(6):717-25.

- Trojano M, Liguori M, Bosco Zimatore G, et al. Age-related disability in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol 2002;51:475–480. [CrossRef]

- Martinelli V, Rodegher M, Moiola L, Comi G. Late onset multiple sclerosis: clinical characteristics, prognostic factors and differential diagnosis. Neurol Sci 2004;25(suppl 4):S350–S355.

- Kalincik T, Buzzard K, Jokubaitis V, et al. Risk of relapse phenotype recurrence in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2014; 20: 1511–1522. [CrossRef]

- Kresovich JK, Xu Z, O'Brien KM, et al. Based Biological Age and Breast Cancer Risk. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019 Oct 1;111(10):1051-1058.

- McMurran CE, Wang Y, Mak JKL et al. Advanced biological ageing predicts future risk for neurological diagnoses and clinical examination findings. Brain. 2023 Dec 1;146(12):4891-4902). [CrossRef]

- Soriano-Tárraga C, Giralt-Steinhauer E, Mola-Caminal et al. Biological Age is a predictor of mortality in Ischemic Stroke. Sci Rep. 2018 Mar 7;8(1):4148.

- Chen BH, Marioni RE, Colicino E. DNA methylation-based measures of biological age: meta-analysis predicting time to death. Aging (Albany NY). 2016 Sep 28;8(9):1844-1865. [CrossRef]

- Oblak L, van der Zaag J, Higgins-Chen AT et al. A systematic review of biological, social and environmental factors associated with epigenetic clock acceleration. Ageing Res Rev. 2021 Aug;69:101348. [CrossRef]

- Marioni RE, Harris SE, Shah S et al. The epigenetic clock and telomere length are independently associated with chronological age and mortality. Int J Epidemiol. 2018 Feb 1;47(1):356.

- Belsky DW, Moffitt TE, Cohen AA et al. Eleven Telomere, Epigenetic Clock, and Biomarker-Composite Quantifications of Biological Aging: Do They Measure the Same Thing? Am J Epidemiol. 2018 Jun 1;187(6):1220-1230.

- Shay, J.W. Telomeres and aging. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2018, 52, 1–7.

- Blackburn, E. Structure and function of telomeres. Nature 1991, 350, 569–573.

- Rubtsova, M.P.; Vasilkova, D.P.; Malyavko, A.N.; Naraikina, Y.V.; Zvereva, M.I.; Dontsova, O.A. Telomere lengthening and other functions of telomerase. Acta Nat. 2012, 4, 44–61.

- Shammas MA. Telomeres, lifestyle, cancer, and aging. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2011 Jan;14(1):28-34.

- Kirchner, H.; Shaheen, F.; Kalscheuer, H. et al. F. Association of telomere length in older men with mortality and midlife body mass index and smoking. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2011, 66, 815–820.

- Haycock PC, Heydon EE, Kaptoge S, Leucocyte telomere length and risk of cardiovascular disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2014 Jul 8;349:g4227.

- Cao Z, Hou Y, Xu C. Leucocyte telomere length, brain volume and risk of dementia: a prospective cohort study. Gen Psychiatr. 2023 Sep 11;36(4):e101120. [CrossRef]

- Georgin-Lavialle S, Aouba A, Mouthon L. The telomere/telomerase system in autoimmune and systemic immune-mediated diseases. Autoimmun Rev. 2010 Aug;9(10):646-51). [CrossRef]

- Bühring J, Hecker M, Fitzner B et al. Review of Studies on Telomere Length in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis. Aging Dis. 2021 Aug 1;12(5):1272-1286.

- Guan JZ, Guan WP, Maeda T et al. Patients with multiple sclerosis show increased oxidative stress markers and somatic telomere length shortening. Mol Cell Biochem. 2015 Feb;400(1-2):183-7.

- Krysko KM, Henry RG, Cree BAC et al. Telomere Length Is Associated with Disability Progression in Multiple Sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2019 Nov;86(5):671-682. [CrossRef]

- Hecker M, Bühring J, Fitzner B et al. Genetic, Environmental and Lifestyle Determinants of Accelerated Telomere Attrition as Contributors to Risk and Severity of Multiple Sclerosis. Biomolecules. 2021 Oct 13;11(10):1510. [CrossRef]

- Habib R, Ocklenburg S, Hoffjan S et al. Association between shorter leukocyte telomeres and multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol. 2020 Apr 15;341:577187.

- Liao Q, He J, Tian FF, Bi FF, Huang K. A causal relationship between leukocyte telomere length and multiple sclerosis: A Mendelian randomization study. Front Immunol. 2022 Jul 15;13:922922.

- Ma Y, Wang M, Chen X, Ruan W, Yao J, Lian X. Telomere length and multiple sclerosis: a Mendelian randomization study. Int J Neurosci. 2024 Jun;134(3):229-233.

- Shu MJ, Li J, Zhu YC. Genetically predicted telomere length and multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2022 Apr;60:103731.

-

Horvath S , Raj K . DNA methylation-based biomarkers and the epigenetic clock theory of ageing. Nat. Rev. Genet. 19(6), 371–384 (2018).

- Theodoropoulou E, Alfredsson L, Piehl F et al. Different epigenetic clocks reflect distinct pathophysiological features of multiple sclerosis. Epigenomics. 2019 Sep;11(12):1429-1439. [CrossRef]

- Kular L, Klose D, Urdánoz-Casado A et al. Epigenetic clock indicates accelerated aging in glial cells of progressive multiple sclerosis patients. Front Aging Neurosci. 2022 Aug 24;14:926468.

- Maltby V, Xavier A, Ewing E et al. Evaluation of Cell-Specific Epigenetic Age Acceleration in People With Multiple Sclerosis. Neurology. 2023 Aug 15;101(7):e679-e689. [CrossRef]

- Cohen A, Milot E, Li Q et al. Detection of a novel, integrative aging process suggests complex physiological integration. PLoS One. 2015; 10e0116489.

- Miner AE, Yang JH, Kinkel RP, Graves JS. The NHANES Biological Age Index demonstrates accelerated aging in MS patients. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2023 Sep;77:104859.

- Tur C, Carbonell-Mirabent P, Cobo-Calvo Á. Association of Early Progression Independent of Relapse Activity With Long-term Disability After a First Demyelinating Event in Multiple Sclerosis. JAMA Neurol. 2023 Feb 1;80(2):151-160.

- Tintoré M, Rovira À, Río J et al. Defining high, medium and low impact prognostic factors for developing multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2015 Jul;138(Pt 7):1863-74.

- Ma S, Wang C, Mao X. B cell dysfunction associated with aging and autoimmune diseases. Front Immunol. 2019;10:318.

- Papadopoulos D, Magliozzi R, Mitsikostas DD et al. Aging, Cellular Senescence, and Progressive Multiple Sclerosis. Front Cell Neurosci. 2020 Jun 30;14:178.

- Nicaise AM, Wagstaff LJ, Willis CM et al. Cellular senescence in progenitor cells contributes to diminished remyelination potential in progressive multiple sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019 Apr 30;116(18):9030-9039. [CrossRef]

- Scalfari A, Neuhaus A, Daumer M, et al. Age and disability accumulation in multiple sclerosis.Neurology 2011; 77: 1246–1252.

- Zhu M, Meng P, Ling X, Zhou L. Advancements in therapeutic drugs targeting of senescence. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2020 Oct 13;11:2040622320964125).

- Sutter PA, McKenna MG, Imitola J. Therapeutic opportunities for targeting cellular senescence in progressive multiple sclerosis. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2022 Apr;63:102184.

- Mao P, Manczak M, Shirendeb UP. MitoQ, a mitochondria-targeted antioxidant, delays disease progression and alleviates pathogenesis in an experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis mouse model of multiple sclerosis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013 Dec;1832(12):2322-31.

- Fetisova EK, et al.: Therapeutic effect of the mitochondria targeted antioxidant SkQ1 on the culture model of multiple sclerosis. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2019, 2019:208256.

- Abo Taleb HA, Alghamdi BS: Neuroprotective effects of melatonin during demyelination and remyelination stages in a mouse model of multiple sclerosis. J Mol Neurosci 2020, 70:386–402.

- Sanadgol N, et al.: Metformin accelerates myelin recovery and ameliorates behavioral deficits in the animal model of multiple sclerosis via adjustment of AMPK/Nrf2/mTOR signaling and maintenance of endogenous oligodendrogenesis during brain self-repairing period. Pharmacol Rep 2020, 72:641–658.

- Chaib S, Tchkonia T, Kirkland JL. Cellular senescence and senolytics: the path to the clinic. Nat Med. 2022 Aug;28(8):1556-1568. [CrossRef]

- https://clinicaltrials.gov (NCT04063124, NCT04685590).

- Drake S, Zaman A, Gianfelice C, et al. Senolytic treatment depletes microglia and decreases severity of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. bioRxiv 2024.02.05.5790.

-

https://www.ema.europa.eu/es/documents/product-information/sprycel-epar-productinformation_

es.pdf.

- Werner C., Fürster T., Widmann T et al. Physical exercise prevents cellular senescence in circulating leukocytes and in the vessel wall. Circulation. 2009;120:2438–2447.

- Ludlow A.T., Ludlow L.W., Roth S.M. Do telomeres adapt to physiological stress? Exploring the effect of exercise on telomere length and telomere-related proteins. Biomed. Res. Int. 2013;2013:601368.

- Sánchez-González JL, Sánchez-Rodríguez JL, Varela-Rodríguez S et al. Effects of Physical Exercise on Telomere Length in Healthy Adults: Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Meta-Regression. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2024 Jan 9;10:e46019.

- Xu M, Zhu J, Liu XD el al. Roles of physical exercise in neurodegeneration: reversal of epigenetic clock. Transl Neurodegener. 2021 Aug 13;10(1):30).

- Astuti Y, Wardhana A, Watkins J, Wulaningsih W; PILAR Research Network. Cigarette smoking and telomere length: A systematic review of 84 studies and meta-analysis. Environ Res. 2017 Oct;158:480-489.

- Raftopoulou C, Paltoglou G, Charmandari E. Association between Telomere Length and Pediatric Obesity: A Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2022 Mar 15;14(6):1244. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).