1. Introduction

Modern neuroscience has fundamentally reevaluated the spinal cord, which was once thought of as merely a means of transmitting motor and sensory signals from the brain to the periphery. This component of the central nervous system has been reinterpreted as a dynamic computational hub, essential for complex sensorimotor coordination and adaptive motor control, by recent advances in spine connectomics and neural integration [

1]. This paradigm change recognizes the inherent ability of the spinal cord to process information, apply sophisticated algorithms like Bayesian inference and predictive coding, and carry out context-dependent routing strategies that dynamically modify motor output in response to behavioral states and environmental demands [

1]. This active computational role, rather than a passive relay function, has significant implications for understanding neurodegenerative diseases, developing next-generation neuroprosthetic technologies, and advancing precision rehabilitation approaches for spinal cord injuries and associated disorders [

1].

The outstanding developments in spinal connectomics and neural integration between 2015 and 2025 are summarized in this review. Computational neuroscience, precision neuromodulation, and cutting-edge neuroengineering technologies have all come together during this time. Clarifying the complex neural circuits governing sensorimotor integration, motor control, and adaptive plasticity within spinal networks has been made possible in large part by these interdisciplinary efforts [

1]. The methodological advances that have made this deeper understanding possible, the computational models that explain spinal function, and the emerging clinical applications that have the potential to revolutionize patient care will all be covered in detail in the sections that follow.

2. Methodology

This narrative review was conducted to synthesize the significant advancements in spinal connectomics and neuroengineering that occurred between January 1, 2015, and June 1, 2025, with a focus on the integration of high-resolution electrophysiology, neuroimaging, computational modeling, and machine learning in elucidating spinal circuit function. Our methodological framework prioritized interdisciplinary evidence, combining basic neuroscience, biomedical engineering, clinical studies, and computational innovations relevant to the structure and function of the spinal cord.

2.1. Literature Search Strategy

A structured literature search was performed using PubMed, Web of Science, IEEE Xplore, and Google Scholar, covering the period from 2015 to June 2025. Search terms included combinations of: “spinal connectomics”, “spinal cord circuitry”, “high-density electrophysiology”, “ultraflexible electrodes”, “Neuropixels spinal cord”, “optogenetics spinal circuits”, “spinal cord fMRI”, “7T spinal imaging”, “predictive coding spinal cord”, “Bayesian integration spinal networks”, “machine learning spinal cord”, and “neuroengineering spinal rehabilitation”.

Inclusion criteria were:

Peer-reviewed journal articles, conference proceedings, and technical reports.

English-language publications.

Relevance to the functional and structural mapping of spinal networks using advanced techniques.

Clinical studies or translational work relating to spinal cord injury (SCI), neuromodulation, or neuroprosthetic applications.

Exclusion criteria were:

Studies have been conducted solely on brain circuits without regard to their spinal relevance.

Preclinical studies not involving the spinal or neuromuscular systems.

Review articles unless they provided original meta-analytical insights or introduced novel conceptual frameworks.

2.2. Temporal and Thematic Categorization

The extracted literature was categorized into four principal domains reflecting thematic and technological advances:

Electrophysiological innovations, including ultraflexible neural probes (e.g., NETs [

2,

3,

4,

5]) and reusable Neuropixels systems (e.g., Apollo Implant [

5]).

Optogenetic circuit mapping, including causal modulation studies in SCI models (2018–2023) and the emergence of biodegradable electroceuticals (2025).

Advanced imaging, notably 7T axis-resolved fMRI and ADC-fMRI applications in spinal cord mapping (2023–2025).

Computational neuroscience, including predictive coding and Bayesian modeling (2017–2025), and AI/ML applications in spinal diagnostics and neuromodulation (2023–2025).

2.3. Evaluation of Evidence and Integration

The methodology rigor, technological novelty, sample size, and translational potential of each included study were evaluated critically. Long-term results, reproducibility, and controls were assessed in experimental studies [

2,

7]. Model architecture, training datasets, interpretability, and clinical deployment were evaluated in computational and machine learning studies [

24,

25]. Resolution, motion correction techniques, and laminar specificity were evaluated in imaging studies [

9,

13].

Following a convergent model, the synthesis integrated biological, computational, and therapeutic insights into a single framework while also aligning structural and functional findings across modalities. Translational readiness and interdisciplinary synergy were prioritized whenever feasible.

2.4. Timeline and Data Cutoff

The review includes data published and accessible through

June 15, 2025. Methodological and clinical trial data were included if peer-reviewed or posted in registered databases (e.g., ClinicalTrials.gov for Neuralink’s PRIME study, NCT06429735) [

30,

31]. For real-time validation of emerging trends, recent publications and preprints were cross-referenced with news releases from academic institutions and technical disclosures from industry partners.

3. Methodological Advances in Spinal Connectomics Elucidation

The ability to map and understand the complex circuitry of the spinal cord has been revolutionized by a suite of advanced methodologies. These innovations have provided unprecedented spatial and temporal resolution, moving beyond traditional approaches to offer a dynamic view of spinal neural activity. This section offers a comprehensive examination of these significant advancements.

3.1. High-Density Electrophysiology

Since high-density electrophysiology provides precise measurements of neuronal activity, it has become a fundamental tool for understanding how spinal circuits work. The considerable motion of the spinal cord in relation to the vertebral column during natural behaviors has long been a major problem in spinal cord electrophysiology [

2,

3]. These movements are frequently not supported by conventional, more rigid neural electrodes, which can result in excessive noise, position drifts, and possible long-term spinal damage or scarring [

2,

3].

The creation of ultraflexible electrodes, like 1-μm-thick polyimide nanoelectronic threads (NETs), is a crucial invention tackling this problem (

Table 1) [

4]. Because of their mechanical compliance, these incredibly thin probes can move and conform to the spinal tissue, preserving stable contact and reducing tissue damage [

4]. High-quality single-unit recordings from spinal neurons in awake, freely moving animals are directly correlated with this mechanical adaptability, which was previously challenging to accomplish [

2,

3]. With chronic in vivo recordings that lasted more than five months, researchers have shown that spike sorting can be used to track neuron populations steadily, even during a variety of active behaviors like locomotion [

2,

3]. This feature allows neuroscientists to bridge the gap between the functional roles of spinal cell types within circuits and their genetic and developmental characterizations by providing an unmatched opportunity to observe the function of individual spinal cells within the context of a wide range of natural behaviors [

2,

3].

This feature allows neuroscientists to bridge the gap between the functional roles of spinal cell types within circuits and their genetic and developmental characterizations by providing an unmatched opportunity to observe the function of individual spinal cells within the context of a wide range of natural behaviors [

2,

3]. From a translational standpoint, this technology establishes the foundation for creating intraspinal interfaces that are intended to treat ailments like stroke, spinal cord injury (SCI), and different types of movement disorders [

2,

3].

Neuropixels probes are an additional important advancement in high-density electrophysiology that complement these incredibly flexible designs. Although they were originally created for brain recordings, their dense recording-site density and high channel count (up to 384 recording channels addressing 960 sites on a single shank) have made them more and more applicable for spinal cord applications [

5]. With single-cell resolution, hundreds of neurons can be recorded simultaneously thanks to these probes [

5]. Innovations like the "Apollo Implant" have addressed the problem of chronic implantation and reusability, especially for smaller animals like mice [

5]. Crucially, this open-source, two-part implant (payload and docking modules) enables the recovery and reuse of pricey Neuropixels probes numerous times without appreciably lowering recording quality, in addition to enabling safe, portable, and flexible chronic recordings [

5].

Previously constrained by the acute nature or expense of other high-density systems, the capacity to conduct long-term, stable recordings in freely behaving animals is revolutionary, enabling researchers to examine intricate processes, like learning and memory formation, over prolonged periods of time [

5]. In order to convert high-resolution electrophysiology from controlled head-fixed brain studies to dynamic, physiologically relevant spinal cord models, high-channel-count probes must converge with materials science advancements like ultraflexible NETs and reusable implants. Achieving thorough functional mapping in a more realistic setting requires this integration.

3.2. Optogenetics for Circuit Dissection

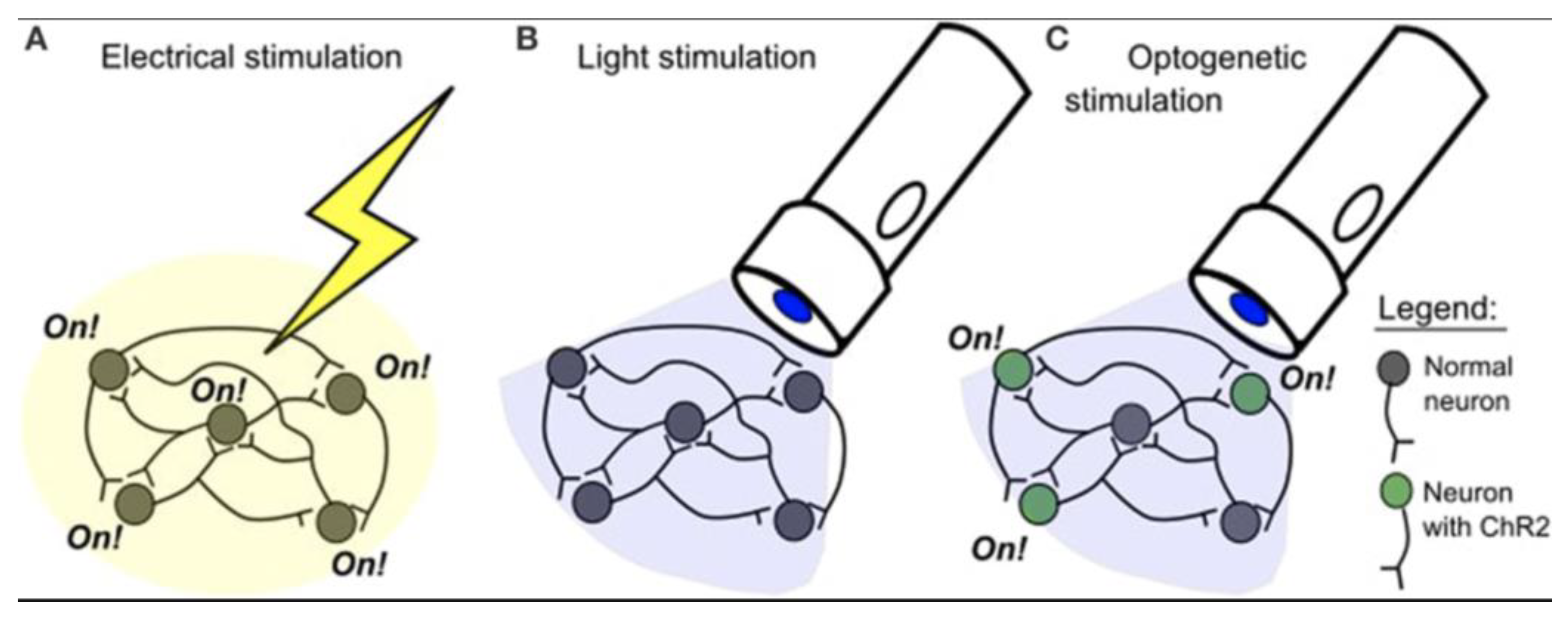

Optogenetics has emerged as a powerful tool for dissecting spinal circuit function due to its unparalleled ability to achieve cell-type-specific activation or inhibition of neural pathways. Unlike traditional electrical stimulation, which broadly activates all nearby neurons and glial cells, optogenetics allows for the precise targeting of specific neuronal populations expressing light-sensitive proteins (

Figure 1) [

5,

6,

61]. This specificity is crucial for understanding the causal roles of distinct cell types and pathways within complex spinal networks.

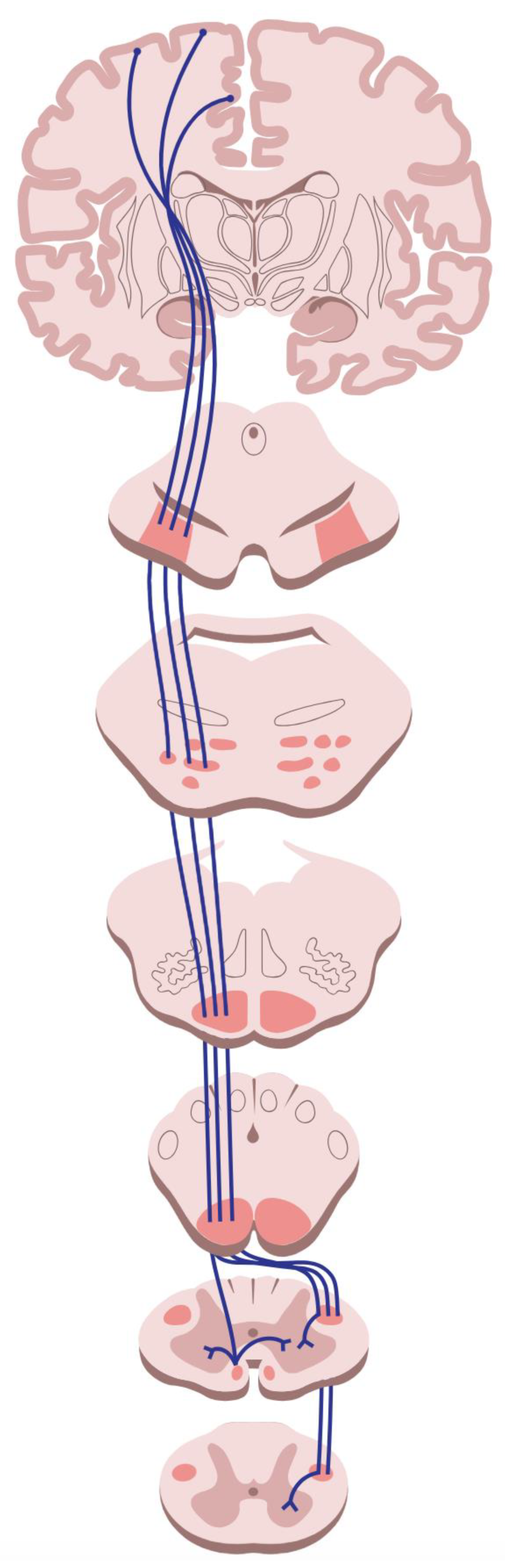

In spinal cord research, encouraging functional recovery following injury is a crucial use of optogenetic stimulation. Neuron-specific optogenetic spinal stimulation dramatically improves the recovery of skilled forelimb reaching, according to studies conducted in rat models of cervical SCI (

Figure 2) (

Table 1) [

5,

6,

7,

62]. Strong biological alterations, such as increased axonal growth (shown by elevated GAP-43 and laminin labeling) and enhanced angiogenesis (the formation of new blood vessels) within the injured spinal cord, support this functional improvement. In order to restore function, the induced axonal growth may spread caudally around the lesion and possibly create new connections with downstream neurons. One of the main causes of this increased axonal growth is the neuronal activation brought on by optogenetic stimulation, which may increase neurotrophic factors and foster neuroprotection. When paired with rehabilitation, this targeted stimulation can promote the formation of new, functionally relevant circuitry through Hebbian plasticity, where synchronized neural activity strengthens connections [

5,

6,

7].

However, it's not always easy to go from structural repair to functional recovery. While optogenetic activation can confirm the formation of functional synapses, studies examining the functional integration of regenerated axons, such as Sox11-stimulated corticospinal tract (CST) axons in injured spinal cord, have shown that this structural reconnection does not always result in a significant improvement in behavior (

Figure 3) [

5,

6,

7,

63]. This finding highlights a crucial problem: meaningful behavioral outcomes depend on the precise functional targeting and suitable integration of newly formed synapses into preexisting or reorganized circuits; simple anatomical reconnection is insufficient. Instead of concentrating only on encouraging axonal growth, this discovery guides future research towards comprehending the fundamentals of functional circuit re-integration.

A promising, less invasive method of nerve regeneration is provided by biodegradable semiconductor-based electroceuticals, which further advance the field [

8]. After their therapeutic purpose is finished, these devices are made to naturally decompose within the body and provide precise electrical stimulation to damaged motor pathways. This improves long-term patient outcomes and device longevity by reducing the risk of chronic inflammation and doing away with the need for invasive removal surgeries, which is a major advantage over conventional implants [

8]. A new class of bioresorbable technology with wide-ranging applications beyond SCI, including other neurological disorders, has been created by this innovation, which combines materials science and neuroengineering [

8].

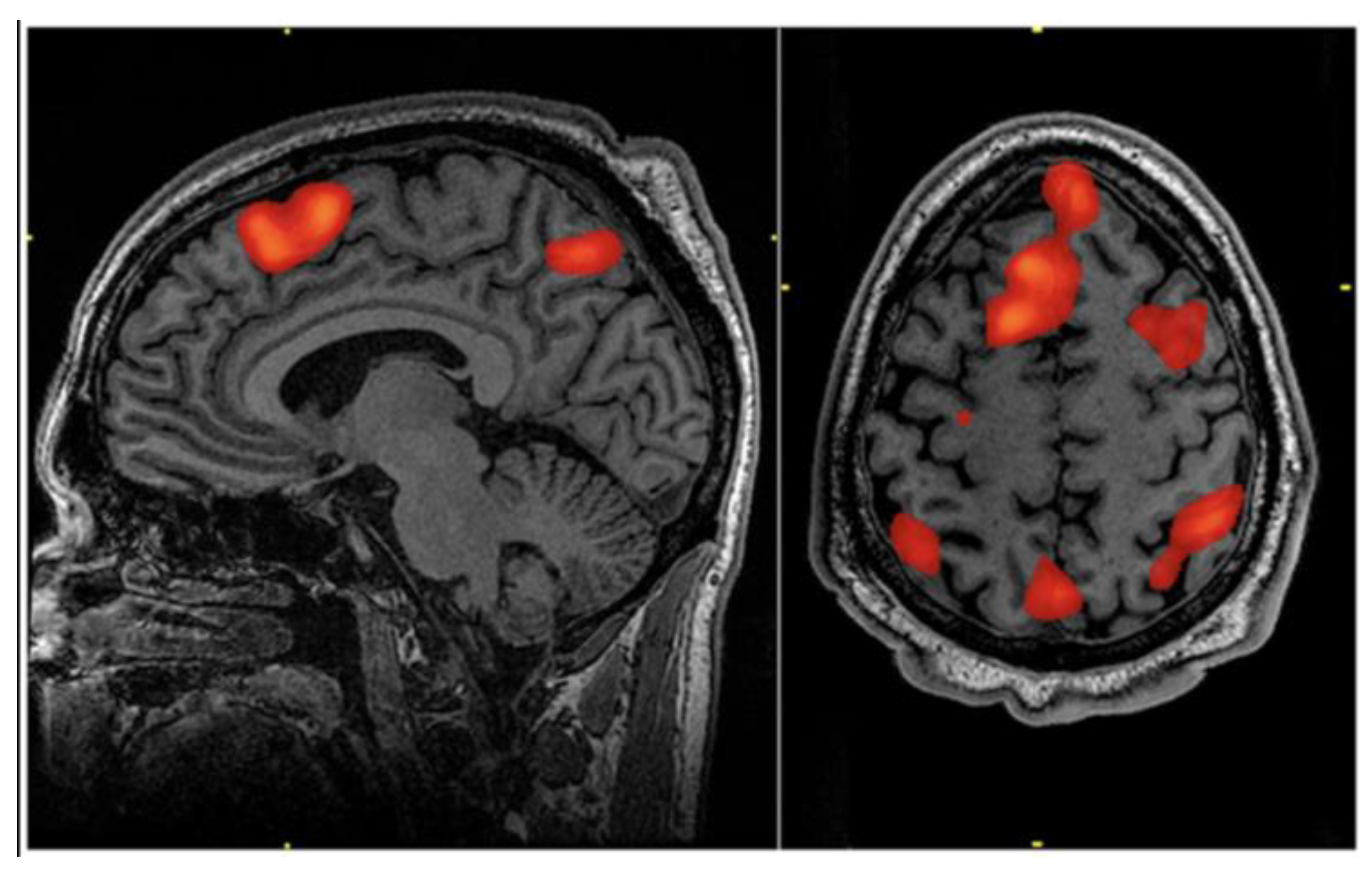

3.3. Advanced Neuroimaging Techniques

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) has long been a cornerstone of brain research, but its application to the spinal cord presents unique and significant technical challenges (

Table 1) (

Figure 4) [

64]. The spinal cord's small cross-section, its proximity to the vertebral column, and the physiological noise from surrounding organs, such as the lungs, introduce strong spatial inhomogeneity and temporal fluctuations in the magnetic field [

9,

64]. Despite these hurdles, remarkable progress has been made, particularly with the advent of ultra-high field systems.

An important advancement in spinal cord imaging is 7 Tesla (7T) axis-resolved fMRI [

1]. In order to resolve fine-grained functional organization within the spinal cord, including laminar-specific mapping, this higher field strength allows for improved sensitivity to the blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD) signal and superior spatial resolution [

9]. Using both single-shot and multi-shot 2D echo-planar imaging (EPI) protocols, early research has effectively shown that group-level sensory task fMRI in the cervical spinal cord at 7T is feasible [

9]. Depending on the needs of the experiment, multi-shot EPI (0.60 mm) offers a trade-off between sensitivity and spatial precision, while single-shot EPI (0.75 mm in-plane resolution) typically produces the highest mean z-statistic. Multi-shot EPI also offers better-localized activation clusters and less geometric distortion [

9].

The drive towards ultra-high field fMRI for spinal cord imaging reflects a critical need for higher spatial and laminar resolution. This advancement is vital for moving beyond macro-level observations to a detailed, circuit-level understanding of spinal function

in vivo. The ability to map activity across Rexed laminae, defined by their cellular structure and function, is crucial for unraveling the complex processing of sensory and motor information within the spinal gray matter [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15].

In addition to BOLD-fMRI, Apparent Diffusion Coefficient (ADC)-fMRI has the potential to identify gray and white matter neural activity, circumventing some of the drawbacks of traditional BOLD signals [

13]. Particularly in white matter, where BOLD signals can be unclear because of passive signal spread, ADC-fMRI provides a more direct measure of neuronal firing and better temporal specificity than BOLD-fMRI because it is sensitive to temporary cellular deformations during neural activity [

13]. By detecting white matter activity regardless of fiber direction, this method creates new opportunities to study gray and white matter functional connectivity throughout the entire brain [

13]. Furthermore, the development of high-resolution multi-contrast templates for the cervical spinal cord at 80 µm resolution is enhancing anatomical and microstructural analysis, allowing for precise identification of subtle changes in gray matter motoneuron pools due to degeneration or injury [

13,

15]. These imaging advancements are crucial for both fundamental connectomics research and for improving diagnostic and prognostic capabilities in various spinal cord pathologies.

3.4. Comparative Analysis of Spinal Connectomics Mapping Techniques

The diverse array of advanced techniques for spinal connectomics each offers unique strengths and limitations, making a multi-modal approach essential for a comprehensive understanding of spinal circuit architecture and function. The choice of methodology often depends on the specific research question, the desired resolution (spatial or temporal), and the level of invasiveness acceptable for the study.

Table 1.

Comparison of Advanced Spinal Connectomics Mapping Techniques (2015-2025).

Table 1.

Comparison of Advanced Spinal Connectomics Mapping Techniques (2015-2025).

| Technique |

Key Innovation |

Strengths |

Limitations |

Primary Application |

| High-Density Electrophysiology (e.g., Ultraflexible NETs, Neuropixels) [2,3,4,5] |

Ultraflexible materials (NETs) for motion compensation; High channel count & reusability (Neuropixels/Apollo) |

High temporal resolution; Single-unit resolution; Chronic recording in behaving animals; Direct neural activity measurement |

Invasive; Risk of tissue damage/scarring (reduced with NETs); Complex data analysis (spike sorting) |

Detailed circuit function; Neuron population dynamics; Behavior-activity correlation; Intra-spinal interfaces |

| Optogenetics [5,6,7,8] |

Cell-type-specific neural activation/inhibition; Biodegradable electroceuticals |

Precise causal manipulation of specific cell types; Promotes axonal growth & angiogenesis; Reduced inflammation (biodegradable) |

Invasive (viral delivery, light fiber implantation); Requires genetic modification; Potential for off-target effects; Behavioral improvements not guaranteed by structural reconnection alone |

Dissecting causal roles of specific circuits, Promoting regeneration, Targeted neurorehabilitation |

| 7 Tesla Axis-Resolved fMRI [10,11,12,13,14,15] |

Ultra-high field strength for enhanced resolution; ADC-fMRI for gray/white matter |

Non-invasive; High spatial resolution (laminar-specific); Detects activity in gray & white matter; Provides anatomical and functional context |

Technically demanding (motion artifacts, B0 inhomogeneity); Lower temporal resolution than electrophysiology; Indirect measure of neural activity (BOLD signal) |

Laminar mapping; Functional connectivity; Whole-cord imaging; Diagnosis of pathologies; Understanding neural correlates of behavior |

The comparison above highlights how these techniques are complementary rather than mutually exclusive. For instance, while high-density electrophysiology provides unparalleled temporal resolution and direct measurement of neuronal spikes, its invasiveness limits its widespread clinical application and long-term studies in humans. Optogenetics offers exquisite cell-type specificity, allowing for causal investigations of circuit function and targeted therapeutic interventions, but it also requires invasive genetic manipulation. On the other hand, 7T fMRI provides a non-invasive means to map functional activity across the entire spinal cord with increasing spatial detail, including laminar organization and white matter pathways, though with lower temporal resolution and an indirect measure of neural activity [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15].

The benefits of each approach over another are clear: electrophysiology excels in capturing the precise timing of neural events and individual neuron contributions, optogenetics in establishing causal relationships and cell-specific therapeutic modulation, and fMRI in non-invasively mapping large-scale functional networks and anatomical changes. The future of spinal connectomics lies in the synergistic integration of these diverse methodologies. Combining the high-resolution functional mapping capabilities of fMRI with the cellular precision of optogenetics and the dynamic recording power of high-density electrophysiology, further enhanced by computational modeling, will provide a truly comprehensive understanding of spinal circuit function in health and disease [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. This multimodal strategy enables researchers to overcome the individual limitations of each technique, resulting in a more comprehensive understanding of the spinal cord's complex computational role.

4. Computational Models and Neural Integration

The redefinition of the spinal cord as a dynamic computational hub is deeply rooted in the advancements of computational neuroscience. Biologically realistic computational models have become indispensable tools for understanding the complex functions and integration mechanisms within spinal networks. These models allow researchers to investigate the effects of various connectivity patterns on network behavior and test hypotheses that would be experimentally intractable [

1].

4.1. Predictive Coding and Bayesian Integration

Recent research has shown that complex computational algorithms, such as Bayesian inference mechanisms and predictive coding, are actively implemented in spinal circuits [

1]. According to a well-known theory in cognitive and computational neuroscience called predictive coding, the brain continuously makes predictions about sensory inputs and modifies its internal models in response to prediction errors, or the differences between expected and actual sensory feedback [

14]. According to this framework, the brain tries to reduce uncertainty by coordinating top-down predictions with bottom-up sensory data, which underpins perception, cognition, and behavior [

14].

This translates to a dynamic role in processing multimodal sensory inputs and regulating motor outputs within spinal networks. Higher-order motor areas produce predictions regarding the anticipated sensory effects of motor commands, while spinal circuits calculate prediction errors and update motor programs. This positions spinal networks as active participants in predictive motor control, rather than passive receivers of descending commands [

1].

By elucidating how the nervous system optimally integrates imperfect information from various sensory modalities with prior knowledge to form the most probable estimate of a state, Bayesian integration further refines this understanding [

1]. In sensorimotor control, this means that the spinal cord uses neuromodulatory mechanisms to dynamically reconfigure its network properties in response to supraspinal inputs [

1]. This makes it possible to adapt spinal processing to different behavioral contexts, including skilled motor performance, postural control, and locomotion [

1]. Similar to the Kalman gain in control theory, the brain's ongoing estimation of sensory precision determines the weight given to new sensory information versus preexisting beliefs, which is necessary for this adjustment to be effective [

14]. Disruptions in these inference processes can underlie symptoms in neurological disorders, highlighting the importance of understanding these computational principles for therapeutic design [

14]. Evidence suggests that even in the spinal cord, sensory processing is under top-down cognitive control, with prior knowledge modulating early sensory processing [

16,

17].

4.2. Network Properties and Hierarchical Organization

The basic organizational principles of spinal networks have been uncovered thanks in large part to computational models, which also reveal intricate topological features that facilitate effective information processing. The existence of small-world network characteristics in spinal connectivity is a significant discovery [

1]. Small-world networks are distinguished by short average path lengths between distant nodes, which are similar to those found in random networks, and a high degree of local clustering, which is similar to regular networks [

18]. For complex biological computations, this architecture is thought to be an effective way to maximize the trade-off between local specialization and global integration while achieving both modular and global processing [

1,

2].

Graph-theoretical analyses of spinal connectivity data consistently indicate small-world properties and hierarchical modular organization [

1], despite some research on rat spinal cord connectomes suggesting that small-world attributes are absent in the intrinsic spinal network [

19,

20]. This suggests that the structure of spinal networks is designed to support efficient information transfer while preserving resistance to disturbances [

1,

2]. Graph theory analysis has demonstrated alterations in network metrics in the context of spinal cord injury (SCI), with patients with complete SCI (CSCI) exhibiting reduced structural connectivity efficiency (longer paths, lower global and local efficiency). On the other hand, patients with incomplete SCI (ICSCI) have less structural-functional coupling and more small-worldness and local connections [

21]. These differences in network topology between injury types underscore the potential of graph theory metrics as objective biomarkers for diagnosis and treatment strategies [

21].

Computational models also shed light on the hierarchical structure of spinal processing [

1]. Higher-order motor areas make predictions about anticipated sensory outcomes, and spinal circuits update motor programs based on prediction errors in descending control systems from higher brain regions that employ hierarchical predictive coding techniques [

1]. Spinal networks can execute sophisticated motor control algorithms, including adaptive filtering and optimal feedback control, thanks to this hierarchical structure, which also facilitates adaptive control and learning [

1,

2]. For example, computational models of spinal locomotor circuits show how interactions between rhythm generators for each limb, mediated by commissural interneurons (CINs) and long propriospinal neurons (LPNs), which are in turn regulated by brainstem drives, govern interlimb coordination and gait expression [

22]. These models can reproduce speed-dependent gait transitions and the effects of specific interneuron deletions, providing a mechanistic understanding of motor control and its disruption in injury [

22].

4.3. Machine Learning in Spinal Connectomics

Machine learning (ML) has become an indispensable tool in advancing spinal connectomics, offering novel approaches for data analysis, circuit reconstruction, and the development of adaptive therapies. Modern computational models of spinal networks often employ

artificial neural network architectures and machine learning algorithms to replicate the intricate, nonlinear dynamics observed in experimental preparations [

1].

Deep learning techniques are particularly useful for simulating the hierarchical organization of spinal processing, enabling the creation of models capable of learning optimal control policies for various motor tasks [

1,

2]. By incorporating reinforcement learning principles into spinal network models, researchers can gain insights into how spinal circuits adapt their connectivity patterns based on experience and how maladaptive learning processes might contribute to pathological conditions [

1,

2].

Beyond theoretical modeling, ML is directly impacting clinical applications, especially in spinal cord stimulation (SCS) for chronic pain management. Predicting which patients will respond to SCS has historically been challenging due to a lack of objective biomarkers [

23]. Machine learning algorithms are now being applied to intraoperative electroencephalogram (EEG) data and patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) to build predictive models for SCS outcomes [

24]. For example, decision tree models have achieved high accuracy (88.2%) in distinguishing responders from non-responders based on spectral EEG features and clinical characteristics, offering a promising avenue for refined patient selection and improved outcomes [

24].

Additionally, AI systems trained on large datasets of MRI spine scans are being developed for autonomous detection of MRI spine pathology [

25]. By combining cutting-edge architectures like Vision Transformers and U-Net, these systems are able to detect multiple pathologies and distinguish between normal and abnormal scans with high accuracy (up to 97.9%) [

25]. These AI tools show the scalability and adaptability of deep learning in clinical settings by improving radiology workflows and diagnostic efficiency [

25]. In order to comprehend how different parts of the brain interact and regulate muscle activity, which is pertinent to a number of neurological disorders, interpretable machine learning techniques are also essential [

26].

5. Brain-Machine Interfaces and Neuroengineering

The convergence of neuroscience and engineering has led to the rapid development of Brain-Machine Interfaces (BMIs) and other neuroengineering solutions that hold immense promise for restoring lost neurological function and enhancing human capabilities (

Figure 5) [

65]. These technologies directly interact with the nervous system, offering unprecedented control and feedback mechanisms.

5.1. Neuralink’s High-Resolution Neural Arrays and Bidirectional BMIs

Neuralink, a prominent neurotechnology company, is at the forefront of developing high-resolution neural arrays and bidirectional BMIs. Their N1 Implant, an intracortical BCI implant, establishes a wireless, digital link between the brain and external devices [

27,

28,

29,

30]. This technology aims to restore autonomy to individuals with paralysis by enabling them to control external devices, such as computers and virtual hands, using only their thoughts, without the need for physical movement or wires [

27,

28,

29,

30].

The Neuralink PRIME Study (NCT06429735) is an early feasibility clinical trial assessing the safety and functionality of the N1 Implant and the R1 Robot, a surgical robot designed for precise and rapid placement of the ultra-fine electrode threads near targeted neurons [

30,

31]. Initial trials have shown promising results, with patients able to communicate their intended speech with high accuracy (up to 97%) and control digital devices to perform activities such as playing video games and browsing the internet [

30,

31,

32].

The potential of Neuralink's bidirectional BMIs extends to restoring both motor and sensory functions post-spinal cord injury (SCI) [

1,

2]. The ability to sense and evoke compound action potentials (CAPs) via electrode implantation in spinal cord axonal bundles is a crucial prerequisite for advancing spinal cord-machine interfaces (SCMIs) [

33]. Research is demonstrating the feasibility of recording CAPs from dorsal columns with high spatial precision corresponding to known dermatomal somatotopy, and modulating discharge frequency in dorsal column axons based on proprioceptive changes [

33]. Furthermore, electrical pulses can be directed down descending corticospinal tracts to specifically activate lower limb muscles, and propagated up ascending fibers to be intercepted by rostrally placed electrodes, highlighting the bidirectional potential [

33].

Significant obstacles still exist in spite of these advancements, especially with regard to electrode stability and long-term biocompatibility [

1,

2]. Another chronically implanted microelectrode array BCI, the BrainGate Neural Interface system, has shown a safety record similar to other implanted medical devices. The most frequent adverse event associated with the device is skin irritation around the percutaneous pedestal [

34,

35]. However, more research is needed to determine the long-term risks, which may include surgical or device-related complications [

30]. In the upcoming years, these technologies may revolutionize the everyday lives of people with paralysis, according to the quick speed of innovation in businesses like Neuralink [

30].

5.2. Other Advanced Neuroengineering Applications

Beyond Neuralink, the field of neuroengineering is witnessing a broad array of advancements aimed at restoring and enhancing neurological function.

An important therapeutic advancement for SCI rehabilitation is closed-loop epidural stimulation. By monitoring evoked compound action potentials (ECAPs), closed-loop systems continuously adjust stimulation intensity in real-time, in contrast to conventional open-loop systems that provide fixed-output stimulation [

36]. In clinical trials, this adaptive approach has shown better pain relief, improved function, and decreased opioid dependence, and it guarantees more stable and effective pain management [

36]. Even in patients with motor-complete SCI, the combination of intense locomotor training and epidural electrical stimulation (EES) has demonstrated remarkable success in restoring volitional movement, such as standing, stepping, and cycling [

37]. With proven durability of improvements even in the absence of constant stimulation, this method can enhance the intrinsic stepping capacity of spinal locomotor centers [

37,

38,

39,

40]. Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) in a closed-loop paradigm has also shown groundbreaking results in improving arm and hand function in individuals with incomplete cervical SCI, by strengthening synaptic connectivity from remaining motor networks [

38,

39,

40].

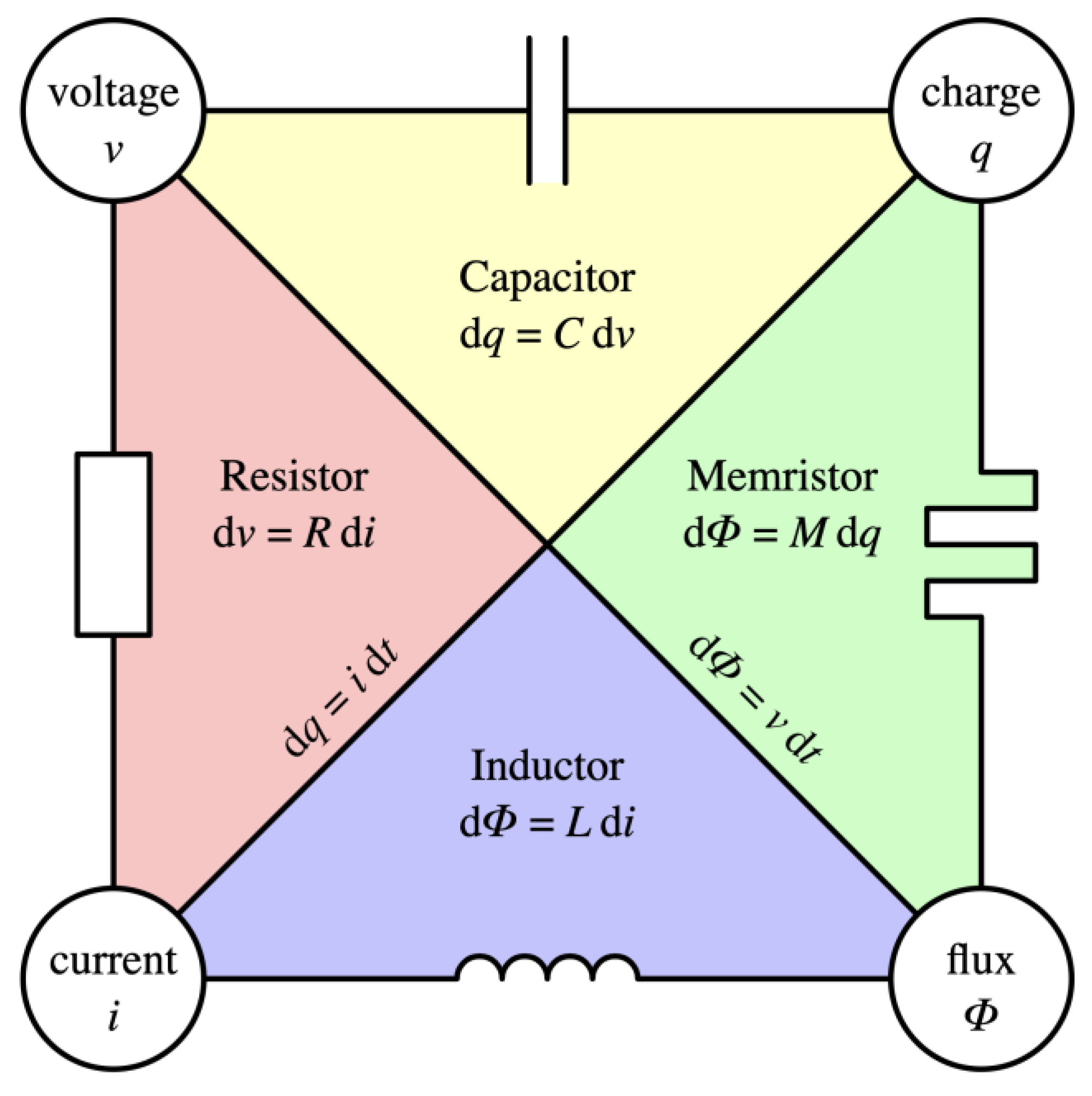

By simulating the operation of biological sensory systems, memristive sensors for prosthetic feedback are transforming the design of neuroprosthetics. The real-time detection, encoding, and processing of environmental information with high operational speed and low power consumption is made possible by memristors' special non-linear resistive memory properties, which allow them to act as artificial receptors, neurons, and synapses (

Figure 6) [

40,

41,

42,

66]. This technology is essential for giving prosthetic users realistic tactile feedback, which improves control over prosthetic limbs and restores the sense of touch [

42,

43,

44]. Biomimetic tactile feedback is being further improved by developments in electronic skins (e-skins) with 3D architectures and sensing components that resemble human mechanoreceptors. This enables decoupled force and strain sensing with spatial resolution similar to that of human skin [

44,

45,

46,

47].

By shifting toward patient-specific, adaptive interventions, personalized neuromodulation is revolutionizing the treatment of chronic pain and diseases like scoliosis [

1,

2]. In order to address the variation in therapeutic results seen with traditional neurostimulation, this method uses biomarkers and real-time brain dynamics to modify stimulation parameters [

48,

49]. AI-driven closed-loop systems for chronic pain are improving stimulation parameters and patient selection, resulting in longer-lasting pain relief and longer device lifespans [

23]. Although research on early-stage neurophysiological, balance, and gait changes in patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS) is still in its infancy, neurodevelopmental theories point to a temporal imbalance in sensorimotor integration processes [

50]. Clinical trials are underway to assess the efficacy of interventions, such as core strength training and sensorimotor training, in addressing these imbalances [

51,

52]. The integration of AI into neurostimulation, for example, through wireless spinal implants and 3D-printed custom devices, is driving innovation towards truly personalized and adaptive treatments [

52,

53].

6. Ethical Considerations

As neurotechnologies advance at an unprecedented pace, critical ethical considerations surrounding their development and application become paramount. Ensuring responsible innovation requires careful attention to equitable access and the protection of neurodata privacy.

Neurodata privacy is a significant concern given the highly sensitive nature of brain activity data. Neurotechnologies, whether implantable or non-implantable, record and can even alter brain activity, generating "neurodata" that not only identifies individuals but also offers an unprecedented depth of understanding into their cognitive state, unique personal experiences, and emotions [

54]. The ability of artificial intelligence algorithms and data-aggregation tools to decode and analyze this sensitive information poses a substantial risk to personal neuroprivacy [

55]. There is a concern that this data could be misused, manipulated, or lead to violations of mental privacy and decision-making autonomy [

54].

To address these risks, experts advocate for robust regulatory frameworks and the implementation of ethical and human rights guidelines [

54]. Key principles include the protection of human dignity, recognition of neurodata as highly sensitive personal data, and the requirement of informed consent for its processing [

54].

Privacy-preserving technologies such as data encryption, differential privacy, and federated learning are becoming integral to maintaining data confidentiality while still enabling expansive research and clinical applications [

55]. The reusability of neural data also presents a new ethical consideration, as its context (mood, health, environment) can change over time [

55]. Integrating ethical values into the design and use of neurotechnologies is essential to ensure non-discriminatory implementation and effective protection of individuals' right to privacy [

53].

Equitable access to these advanced neurotechnologies is another critical ethical challenge. As innovations like Neuralink's implants demonstrate transformative potential for individuals with severe neurological impairments, questions arise regarding the accessibility and affordability of such cutting-edge solutions [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32]. Ensuring that these groundbreaking innovations are available to all who need them, regardless of socioeconomic status, will be a significant hurdle moving forward [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32]. The societal implications of disparities in access to technologies that can restore fundamental motor and sensory functions necessitate proactive policy development and interdisciplinary collaboration to prevent exacerbating existing health inequalities.

7. Future Directions

The rapid advancements in spinal connectomics and neural integration lay a robust foundation for transformative future developments. Three key areas are poised to drive the next decade of innovation: AI-driven discovery, multi-omics integration, and non-invasive neuromodulation.

AI-driven discovery is expected to accelerate the elucidation of comprehensive spinal connectomes. Artificial intelligence, particularly machine learning and deep learning, will move beyond data analysis to become a primary engine for generating new hypotheses and identifying novel circuit mechanisms [

1,

2]. This will involve developing more sophisticated AI models capable of processing vast, multi-modal datasets from electrophysiology, imaging, and omics to identify subtle patterns, predict network behaviors, and even propose new experimental designs. The goal is to move towards individualized spinal interventions that consider both structural connectivity patterns and dynamic functional relationships [

1,

2].

Multi-omics integration will provide a deeper, more holistic understanding of spinal cord biology. By combining genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and lipidomic data with connectomic information, researchers can unravel the complex molecular changes associated with spinal cord injury and disease progression [

56,

57]. This integrated approach can reveal critical insights into pathological mechanisms, such as chronic inflammation and lipid accumulation in myeloid cells post-SCI, and identify novel therapeutic targets [

58]. For instance, single-cell multi-omics assessments are already revealing the heterogeneity of spinal cord tissue after injury and treatment, identifying increases in myelinating oligodendrocytes and myelination-related gene expression, which are crucial for functional recovery [

57,

58]. This comprehensive molecular profiling will enable the development of precision therapies tailored to the specific biological profiles of individual patients.

Non-invasive neuromodulation holds immense promise for expanding therapeutic accessibility and reducing the risks associated with invasive procedures. While epidural stimulation has shown remarkable success in restoring motor function after SCI, its invasive nature remains a barrier for widespread clinical adoption [

59,

60]. Future efforts will focus on optimizing and expanding non-invasive techniques, such as transcutaneous spinal stimulation (scTS), which has already demonstrated the ability to promote stepping in children with motor-complete SCI and yield durable enhancements [

40]. The development of advanced non-invasive brain stimulation (NIBS) modalities, coupled with personalized strategies based on real-time neural dynamics, aims to improve therapeutic outcomes across a wide range of neurological conditions, including chronic pain and potentially scoliosis [

49]. The integration of AI with non-invasive neuromodulation could lead to highly adaptive and patient-tailored therapies, further enhancing their efficacy and reach.

Together, these future directions aim to achieve truly comprehensive spinal connectomes, moving beyond static anatomical maps to dynamic, multi-scale representations that integrate functional, molecular, and behavioral data. This holistic understanding is crucial for developing precision therapies that target specific neural circuits and molecular pathways, ultimately promising enhanced musculoskeletal health and improved functional outcomes for individuals with neurological disorders.

8. Conclusions

The period from 2015 to 2025 has marked a pivotal era in neuroscience, fundamentally transforming the understanding of the spinal cord from a passive neural conduit to a dynamic computational hub. This redefinition, driven by the synergistic advancements in machine learning and neuroengineering, has unveiled the spinal cord's intrinsic capacity for complex information processing, including predictive coding and Bayesian integration, which are essential for adaptive sensorimotor control.

Methodological breakthroughs, such as the development of ultraflexible, high-density electrophysiology probes (e.g., NETs and adaptable Neuropixels implants), have overcome the long-standing challenges of spinal cord motion, enabling unprecedentedly stable, chronic, and high-resolution recordings of neural activity in behaving animals. Optogenetics has provided the critical ability to causally dissect circuit function with cell-type specificity, although findings highlight that mere structural reconnection after injury is insufficient without precise functional integration. Advanced neuroimaging, particularly 7T axis-resolved fMRI and novel ADC-fMRI techniques, has pushed the boundaries of non-invasive mapping, offering laminar-specific and gray/white matter resolution crucial for in vivo connectomics. The complementary nature of these techniques underscores the necessity of multi-modal approaches for a holistic understanding.

Computational models, increasingly powered by machine learning and deep learning, have been instrumental in revealing the small-world network properties and hierarchical organization of spinal circuits, elucidating how these architectures support efficient information transfer and resilience. These models are also directly translating to clinical practice, improving patient selection for spinal cord stimulation and enhancing diagnostic accuracy for spinal pathologies.

In clinical applications, closed-loop epidural stimulation, memristive sensors for biomimetic prosthetic feedback, and personalized neuromodulation strategies exemplify the transformative potential of neuroengineering. Neuralink's high-resolution bidirectional BMIs, despite current challenges in electrode stability, represent a bold frontier in restoring motor and sensory functions post-SCI.

Looking forward, the integration of AI-driven discovery platforms with multi-omics data promises to unlock new biological insights and accelerate the development of individualized spinal interventions. Concurrently, the advancement of non-invasive neuromodulation techniques aims to broaden therapeutic accessibility and minimize procedural risks. These future directions collectively point towards a future where comprehensive spinal connectomes guide precision therapies, offering renewed hope for individuals affected by neurological disorders and paving the way for enhanced musculoskeletal health. The continued collaborative efforts across engineering, neuroscience, and clinical domains will be paramount in realizing the full potential of these groundbreaking advancements.

References

- Kumar R, Sporn K, Gowda C, Khanna A, Prabhakar P, Paladugu P, Jagadeesan R, Clarkson L, Chandrahasegowda S, Kumar T, et al. Advancing Spine Connectomics and Neural Integration through Machine Learning and Neuroengineering. Published online June 6, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Wu Y, Temple BA, Sevilla N, Zhang J, Zhu H, Zolotavin P, Jin Y, Duarte D, Sanders E, Azim E, Nimmerjahn A, Pfaff SL, Luan L, Xie C. Ultraflexible electrodes for recording neural activity in the mouse spinal cord during motor behavior. Cell Rep. 2024 May 28;43(5):114199. Epub 2024 May 9. PMID: 38728138; PMCID: PMC11233142. [CrossRef]

- Xie C, Luan L. RePORT 〉 RePORTER. Nih.gov. Published August 15, 2023. Accessed June 22, 2025. https://reporter.nih.gov/project-details/10900562.

- Jun JJ, Steinmetz NA, Siegle JH, Denman DJ, Bauza M, Barbarits B, Lee AK, Anastassiou CA, Andrei A, Aydın Ç, Barbic M, Blanche TJ, Bonin V, Couto J, Dutta B, Gratiy SL, Gutnisky DA, Häusser M, Karsh B, Ledochowitsch P, Lopez CM, Mitelut C, Musa S, Okun M, Pachitariu M, Putzeys J, Rich PD, Rossant C, Sun WL, Svoboda K, Carandini M, Harris KD, Koch C, O'Keefe J, Harris TD. Fully integrated silicon probes for high-density recording of neural activity. Nature. 2017 Nov 8;551(7679):232-236. PMID: 29120427; PMCID: PMC5955206. [CrossRef]

- Bimbard C, Takács F, Catarino JA, Fabre JMJ, Gupta S, Lenzi SC, Melin MD, O'Neill N, Orsolic I, Robacha M, Street JS, Gomes Teixeira JM, Townsend S, van Beest EH, Zhang AM, Churchland AK, Duan CA, Harris KD, Kullmann DM, Lignani G, Mainen ZF, Margrie TW, Rochefort NL, Wikenheiser A, Carandini M, Coen P. An adaptable, reusable, and light implant for chronic Neuropixels probes. Elife. 2025 Feb 18;13:RP98522. PMID: 39964835; PMCID: PMC11835385. [CrossRef]

- Song Z, Alpers A, Warner K, Iacobucci F, Hoskins E, Disterhoft JF, Voss JL, Widge AS. Chronic, Reusable, Multiday Neuropixels Recordings during Free-Moving Operant Behavior. eNeuro. 2024 Jan 22;11(1):ENEURO.0245-23.2023. PMID: 38253540; PMCID: PMC10849027. [CrossRef]

- Mondello SE, Young L, Dang V, Fischedick AE, Tolley NM, Wang T, Bravo MA, Lee D, Tucker B, Knoernschild M, Pedigo BD, Horner PJ, Moritz CT. Optogenetic spinal stimulation promotes new axonal growth and skilled forelimb recovery in rats with sub-chronic cervical spinal cord injury. J Neural Eng. 2023 Sep 12;20(5):056005. PMID: 37524080; PMCID: PMC10496592. [CrossRef]

- Purdue University. Chi Hwan Lee Leads Revolution in Spinal Cord Injury Recovery with Groundbreaking Electroceuticals for Nerve Regeneration. Weldon School of Biomedical Engineering | West Lafayette & Indianapolis - Purdue University. Published 2025. Accessed June 22, 2025. https://engineering.purdue.edu/BME/AboutUs/News/2025/chi-hwan-lee-leads-revolution-in-spinal-cord-injury-recovery-with-groundbreaking-electroceuticals-for-nerve-regeneration.

- Seifert AC, Xu J, Kong Y, Eippert F, Miller KL, Tracey I, Vannesjo SJ. Thermal stimulus task fMRI in the cervical spinal cord at 7 Tesla. Hum Brain Mapp. 2024 Feb 15;45(3):e26597. PMID: 38375948; PMCID: PMC10877664. [CrossRef]

- Shao X, Guo F, Kim J, et al. Laminar multi-contrast fMRI at 7T allows differentiation of neuronal excitation and inhibition underlying positive and negative BOLD responses. Imaging Neuroscience. 2024;2:1-19. [CrossRef]

- Huber L, Handwerker DA, Jangraw DC, Chen G, Hall A, Stüber C, Gonzalez-Castillo J, Ivanov D, Marrett S, Guidi M, Goense J, Poser BA, Bandettini PA. High-Resolution CBV-fMRI Allows Mapping of Laminar Activity and Connectivity of Cortical Input and Output in Human M1. Neuron. 2017 Dec 20;96(6):1253-1263.e7. Epub 2017 Dec 7. PMID: 29224727; PMCID: PMC5739950. [CrossRef]

- Kinany N, Pirondini E, Micera S, Van De Ville D. Spinal Cord fMRI: A New Window into the Central Nervous System. Neuroscientist. 2023 Dec;29(6):715-731. Epub 2022 Jul 13. PMID: 35822665; PMCID: PMC10623605. [CrossRef]

- Spencer APC, Nguyen-Duc J, de Riedmatten I, Szczepankiewicz F, Jelescu IO. Mapping grey and white matter activity in the human brain with isotropic ADC-fMRI. Nat Commun. 2025 May 30;16(1):5036. PMID: 40447634; PMCID: PMC12125227. [CrossRef]

- Dutta A. Neurocomputational Mechanisms of Sense of Agency: Literature Review for Integrating Predictive Coding and Adaptive Control in Human-Machine Interfaces. Brain Sci. 2025 Apr 14;15(4):396. PMID: 40309878; PMCID: PMC12025756. [CrossRef]

- Tschantz A, Koudahl M, Linander H, Da Costa L, Heins C, Beck J, Buckley C. BAYESIAN PREDICTIVE CODING. arXiv.org. Published March 31, 2025. Accessed June 21, 2025. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2503.24016.

- Körding KP, Wolpert DM. Bayesian integration in sensorimotor learning. Nature. 2004 Jan 15;427(6971):244-7. PMID: 14724638. [CrossRef]

- Stenner MP, Nossa CM, Zaehle T, Azañón E, Heinze HJ, Deliano M, Büntjen L. Prior knowledge changes initial sensory processing in the human spinal cord. Sci Adv. 2025 Jan 17;11(3):eadl5602. Epub 2025 Jan 15. PMID: 39813342; PMCID: PMC11734707. [CrossRef]

- Yu S, Huang D, Singer W, Nikolic D. A small world of neuronal synchrony. Cereb Cortex. 2008 Dec;18(12):2891-901. Epub 2008 Apr 9. PMID: 18400792; PMCID: PMC2583154. [CrossRef]

- Bassett DS, Bullmore ET. Small-World Brain Networks Revisited. Neuroscientist. 2017 Oct;23(5):499-516. Epub 2016 Sep 21. PMID: 27655008; PMCID: PMC5603984. [CrossRef]

- Swanson LW, Hahn JD, Sporns O. Network architecture of intrinsic connectivity in a mammalian spinal cord (the central nervous system’s caudal sector). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2024;121(5). [CrossRef]

- Yang B, Xin H, Wang L, Qi Q, Wang Y, Jia Y, Zheng W, Sun C, Chen X, Du J, Hu Y, Lu J, Chen N. Distinct brain network patterns in complete and incomplete spinal cord injury patients based on graph theory analysis. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2024 Aug;30(8):e14910. PMID: 39185854; PMCID: PMC11345750. [CrossRef]

- Danner SM, Shevtsova NA, Frigon A, Rybak IA. Computational modeling of spinal circuits controlling limb coordination and gaits in quadrupeds. Elife. 2017 Nov 22;6:e31050. PMID: 29165245; PMCID: PMC5726855. [CrossRef]

- Prunskis JV, Masys T, Pyles ST, Abd-Elsayed A, Deer TR, Beall DP, Gheith R, Patel S, Sayed D, Moten H, Hagle T, Yaacoub CI, Anijar L, Gupta M, Dallas-Prunskis T. The Application of Artificial Intelligence to Enhance Spinal Cord Stimulation Efficacy for Chronic Pain Management: Current Evidence and Future Directions. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2025 May 20;29(1):85. PMID: 40394275. [CrossRef]

- Gopal J, Bao J, Harland T, Pilitsis JG, Paniccioli S, Grey R, Briotte M, McCarthy K, Telkes I. Machine learning predicts spinal cord stimulation surgery outcomes and reveals novel neural markers for chronic pain. Sci Rep. 2025 Mar 18;15(1):9279. PMID: 40102462; PMCID: PMC11920397. [CrossRef]

- Subramanian B, Kumarasami N, Shastry P, Sripadraj R, Sivasailam K, D A, Ramachandran A, MP S, G G, Prasath K, et al. AI-Driven MRI Spine Pathology Detection: A Comprehensive Deep Learning Approach for Automated Diagnosis in Diverse Clinical Settings. arXiv.org. Published March 28, 2025. Accessed June 22, 2025. https://www.arxiv.org/abs/2503.20316.

- Glaser J. RePORT 〉 RePORTER. Nih.gov. Published January 20, 2020. Accessed June 22, 2025. https://reporter.nih.gov/project-details/10874470.

- Scott. The Miami Project to Cure Paralysis at University of Miami Miller School of Medicine Selected as a U.S. Site for Neuralink Clinical Trial. The Miami Project. Published January 27, 2025. Accessed June 21, 2025. https://www.themiamiproject.org/neuralink/.

- Kumar R, Waisberg E, Ong J, Lee AG. Response to letter to the editor on 'the potential power of Neuralink - how brain-machine interfaces can revolutionize medicine'. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2025 Jun 17:1-2. Epub ahead of print. Update in: Expert Rev Med Devices. 2025 Jun 17:1-2. doi: 10.1080/17434440.2025.2521393. PMID: 40519178. [CrossRef]

- Kumar R, Waisberg E, Ong J, Lee AG. The potential power of Neuralink – how brain-machine interfaces can revolutionize medicine. Expert Review of Medical Devices. Published online April 28, 2025:1-4. [CrossRef]

- Maldonado M. Can Elon Musk’s brain chip help cure paralysis? Miami study aims to find out. Cbsnews.com. Published January 27, 2025. Accessed June 21, 2025. https://www.cbsnews.com/miami/news/can-elon-musks-brain-chip-help-cure-paralysis-heres-what-you-need-to-know/.

- Yehya N. Brain-computer interface study wins 2025 Top Ten Clinical Research Achievement Award. news. Published February 11, 2025. Accessed June 21, 2025. https://health.ucdavis.edu/news/headlines/brain-computer-interface-study-wins-2025-top-ten-clinical-research-achievement-award-/2025/02.

- Rahmati F. Neuralink’s Groundbreaking implant lets spinal injury patients control devices with their minds - Khaama Press. Khaama Press. Published April 24, 2025. Accessed June 21, 2025. https://www.khaama.com/neuralinks-groundbreaking-implant-lets-spinal-injury-patients-control-devices-with-their-minds/.

- Lo YT, Maggi A, Wu K, Zhong H, Choi W, Nguyen TD, Abedi A, Agyeman K, Sakellaridi S, Reggie Edgerton V, Kreydin E, Lee D, Sideris C, Liu CY, Christopoulos VN. Exploring the Feasibility of Bidirectional Spinal Cord Machine Interface Through Sensing and Stimulation of Axonal Bundles. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. 2025;33:2004-2012. PMID: 40372852. [CrossRef]

- Moxon KA, Foffani G. Brain-machine interfaces beyond neuroprosthetics. Neuron. 2015 Apr 8;86(1):55-67. PMID: 25856486. [CrossRef]

- Rubin DB, Ajiboye AB, Barefoot L, Bowker M, Cash SS, Chen D, Donoghue JP, Eskandar EN, Friehs G, Grant C, et al. Interim Safety Profile From the Feasibility Study of the BrainGate Neural Interface System. Neurology. 2023;100(11):e1177-e1192. [CrossRef]

- Mangano N, Torpey A, Devitt C, Wen GA, Doh C, Gupta A. Closed-Loop Spinal Cord Stimulation in Chronic Pain Management: Mechanisms, Clinical Evidence, and Emerging Perspectives. Biomedicines. 2025 Apr 30;13(5):1091. PMID: 40426918; PMCID: PMC12108722. [CrossRef]

- Albano L, Emedoli D, Agnesi F, Romeni S, Losanno E, Toni L, Fossati V, Ciucci C, Gasperotti F, Cociani L, Zucco G, Pompeo E, Mura C, Carpaneto J, Tettamanti A, Castelnovo V, Padul JD, Mandelli C, Barzaghi LR, Alemanno F, Caravati H, Butera C, Del Carro U, Castellano A, Falini A, Agosta F, Filippi M, Iannaccone S, Mortini P, Micera S. Epidural electrical stimulation facilitates motor recovery in spinal cord injury involving the conus medullaris: A case study. Med. 2025 May 17:100706. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 40436013. [CrossRef]

- Fontenot S. VNS Clinical Trial Shows Improvements for Spinal Cord Injuries. News Center. Published May 21, 2025. Accessed June 22, 2025. https://news.utdallas.edu/health-medicine/vns-human-trial-spinal-cord-injuries-2025/.

- Hoover C, Schuerger W, Balser D, et al. Neuromodulation Through Spinal Cord Stimulation Restores Ability to Voluntarily Cycle After Motor Complete Paraplegia. Journal of Neurotrauma. 2024;41(9-10). [CrossRef]

- Lucas K, Singh G, Alvarado LR, King M, Stepp N, Parikh P, Ugiliweneza B, Gerasimenko Y, Behrman AL. Non-invasive spinal neuromodulation enables stepping in children with complete spinal cord injury. Brain. 2025 Apr 4:awaf115. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 40184166. [CrossRef]

- Patrick D Ganzer, Michael J Darrow, Eric C Meyers, Bleyda R Solorzano, Andrea D Ruiz, Nicole M Robertson, Katherine S Adcock, Justin T James, Han S Jeong, April M Becker, Mark P Goldberg, David T Pruitt, Seth A Hays, Michael P Kilgard, Robert L Rennaker II (2018) Closed-loop neuromodulation restores network connectivity and motor control after spinal cord injury eLife 7:e32058. [CrossRef]

- Kwon JY, Kim JE, Kim JS, Chun SY, Soh K, Yoon JH. Artificial sensory system based on memristive devices. Exploration (Beijing). 2023 Nov 20;4(1):20220162. PMID: 38854486; PMCID: PMC10867403. [CrossRef]

- Mikhaylov A, Pimashkin A, Pigareva Y, Gerasimova S, Gryaznov E, Shchanikov S, Zuev A, Talanov M, Lavrov I, Demin V, Erokhin V, Lobov S, Mukhina I, Kazantsev V, Wu H, Spagnolo B. Neurohybrid Memristive CMOS-Integrated Systems for Biosensors and Neuroprosthetics. Front Neurosci. 2020 Apr 28;14:358. PMID: 32410943; PMCID: PMC7199501. [CrossRef]

- Tyler DJ. Neural interfaces for somatosensory feedback: bringing life to a prosthesis. Curr Opin Neurol. 2015 Dec;28(6):574-81. PMID: 26544029; PMCID: PMC5517303. [CrossRef]

- Peyton R. Young, Kihun Hong, Eden J. Winslow, Giancarlo K. Sagastume, Marcus A. Battraw, Richard S. Whittle, Jonathon S. Schofield. The effects of limb position and grasped load on hand gesture classification using electromyography, force myography, and their combination. PLOS ONE, 2025; 20 (4): e0321319. [CrossRef]

- University of California - Davis. Combining signals could make for better control of prosthetics. ScienceDaily. April 24, 2025. Accessed June 21, 2025. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2025/04/250424121656.htm.

- Tian Y, Valle G, Cederna PS, Kemp SWP. The Next Frontier in Neuroprosthetics: Integration of Biomimetic Somatosensory Feedback. Biomimetics (Basel). 2025 Feb 21;10(3):130. PMID: 40136784; PMCID: PMC11940524. [CrossRef]

- Green M, Hayley A, Gunnersen JM, Nazemian V, Cabble A, Thompson S, Chakravarthy K. Transforming Chronic Pain Management: Integrating Neuromodulation with Advanced Technologies to Tackle Cognitive Dysfunction - A Narrative Review. J Pain Res. 2025 May 16;18:2497-2507. PMID: 40395938; PMCID: PMC12091054. [CrossRef]

- Carè M, Michela Chiappalone, Vinícius Rosa Cota. Personalized strategies of neurostimulation: from static biomarkers to dynamic closed-loop assessment of neural function. Frontiers in neuroscience. 2024;18. [CrossRef]

- Paramento M, Passarotto E, Maccarone MC, Agostini M, Contessa P, Rubega M, Formaggio E, Masiero S. Neurophysiological, balance and motion evidence in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2024 May 22;19(5):e0303086. PMID: 38776317; PMCID: PMC11111046. [CrossRef]

- Neurovations. A Review of Spine Neuromodulation Therapies: Indications, Efficacy, and What (if any) influence SCS Has Upon the Tapering of Opioids (Preview). Neurovations.com. Published 2021. Accessed June 22, 2025. https://education.neurovations.com/p/s/a-review-of-spine-neuromodulation-therapies-indications-efficacy-and-what-if-any-influence-scs-has-upon-the-tapering-of-opioids-2325.

- Zhou X, Li X, Chen N, Chen Z, Yu H, Liang J, Fan Q, Zhu X, Zhang T, Zhou X, Du Q. Efficacy of sensorimotor training combined with core strength training for low back pain in adult idiopathic scoliosis: a study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2025 May 23;15(5):e091476. PMID: 40409968; PMCID: PMC12104929. [CrossRef]

- Brylkov M. Spinal Implants Are Evolving: What’s Next in 2025? - iData Research. iData Research. Published March 14, 2025. Accessed June 21, 2025. https://idataresearch.com/spinal-implants-are-evolving-whats-next-in-2025/.

- Nougrères AB. UN expert calls for regulation of neurotechnologies to protect right to privacy. OHCHR. Published March 12, 2025. Accessed June 21, 2025. https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2025/03/un-expert-calls-regulation-neurotechnologies-protect-right-privacy.

- Yuste, R. Advocating for neurodata privacy and neurotechnology regulation. Nat Protoc 18, 2869–2875 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Gill SS, Ponniah HS, Giersztein S, Anantharaj RM, Namireddy SR, Killilea J, Ramsay DC, Salih A, Thavarajasingam A, Scurtu D, Jankovic D, Russo S, Kramer A, Thavarajasingam SG. The diagnostic and prognostic capability of artificial intelligence in spinal cord injury: A systematic review. Brain Spine. 2025 Feb 5;5:104208. PMID: 40027293; PMCID: PMC11871462. [CrossRef]

- Yao XQ, Chen JY, Garcia-Segura ME, Wen ZH, Yu ZH, Huang ZC, Hamel R, Liu JH, Shen X, Huang ZP, Lu YM, Zhou ZT, Liu CT, Shi JM, Zhu QA, Peruzzotti-Jametti L, Chen JT. Integrated multi-omics analysis reveals molecular changes associated with chronic lipid accumulation following contusive spinal cord injury. Exp Neurol. 2024 Oct;380:114909. Epub 2024 Aug 5. PMID: 39097074. [CrossRef]

- Wang K, Zheng J, Li R, Chen T, Ma Y, Wu P, Luo J, Zhu J, Lin W, Zhao M, Yuan Y, Ma W, Lin X, Wang Y, Liu L, Gao P, Lin H, Liu C, Liao Y, Ji Z. Single-Cell Multi-omics Assessment of Spinal Cord Injury Blocking via Cerium-doped Upconversion Antioxidant Nanoenzymes. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2025 Feb;12(8):e2412526. Epub 2025 Jan 9. PMID: 39783786; PMCID: PMC11848599. [CrossRef]

- 2025; Kathryn Lucas, Goutam Singh, Luis R Alvarado, Molly King, Nicole Stepp, Parth Parikh, Beatrice Ugiliweneza, Yury Gerasimenko, Andrea L Behrman, Non-invasive spinal neuromodulation enables stepping in children with complete spinal cord injury, Brain, 2025;, awaf115. [CrossRef]

- Elliott T, Shao M, George DD, Goudman L, Morris DR, Pilitsis JG. Spinal Cord Stimulation Guidelines and Consensus Statements: Systematic Review and Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation II Assessment. Neuromodulation. 2025 May 16:S1094-7159(25)00139-4. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 40380961. [CrossRef]

- File:Blausen 0870 TypesofNeuroglia.png. Wikimedia Commons. Published March 10, 2024. Updated March 10, 2024. Accessed June 22, 2025. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Blausen_0870_TypesofNeuroglia.png&oldid=859366013.

- File:Figure-1.jpg. Wikimedia Commons. Published December 27, 2024. Accessed June 22, 2025. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Figure-1.jpg&oldid=976076959.

- File:202105 Corticospinal tract.svg. Wikimedia Commons. Published May 28, 2025. Accessed June 22, 2025. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:202105_Corticospinal_tract.svg&oldid=1037281446.

- File:FMRI scan during working memory tasks.jpg. Wikimedia Commons. Published August 26, 2024. Accessed June 22, 2025. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:FMRI_scan_during_working_memory_tasks.jpg&oldid=916104563.

- File:Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) - FET09 Prague.jpg. Wikimedia Commons. Published May 8, 2024. Accessed June 22, 2025. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Brain-Computer_Interface_(BCI)_-_FET09_Prague.jpg&oldid=874998787.

- File:Two-terminal non-linear circuit elements.svg. Wikimedia Commons. Published September 24, 2024. Accessed June 22, 2025. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Two-terminal_non-linear_circuit_elements.svg&oldid=928340808.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).