Submitted:

22 June 2025

Posted:

24 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

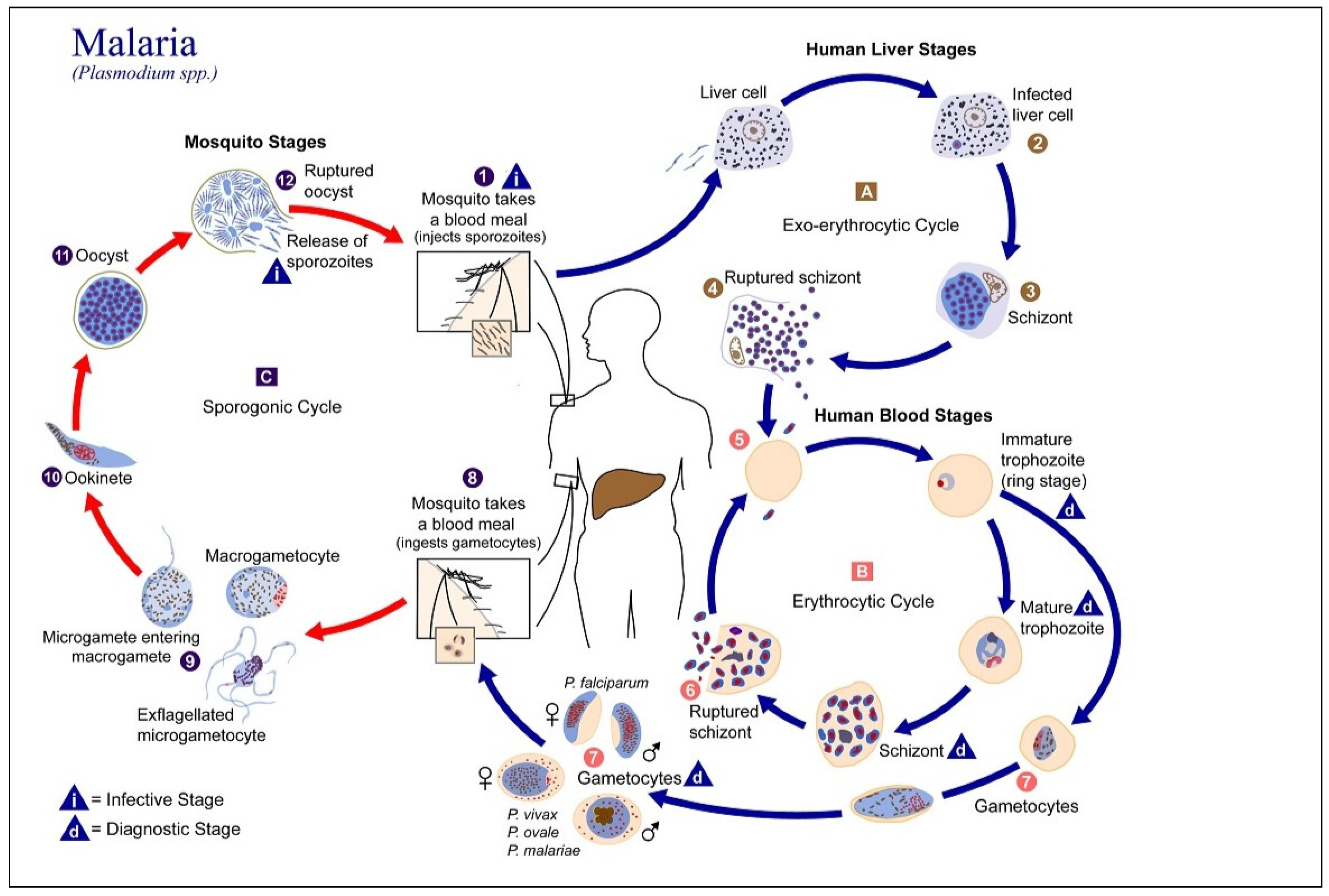

1. Introduction

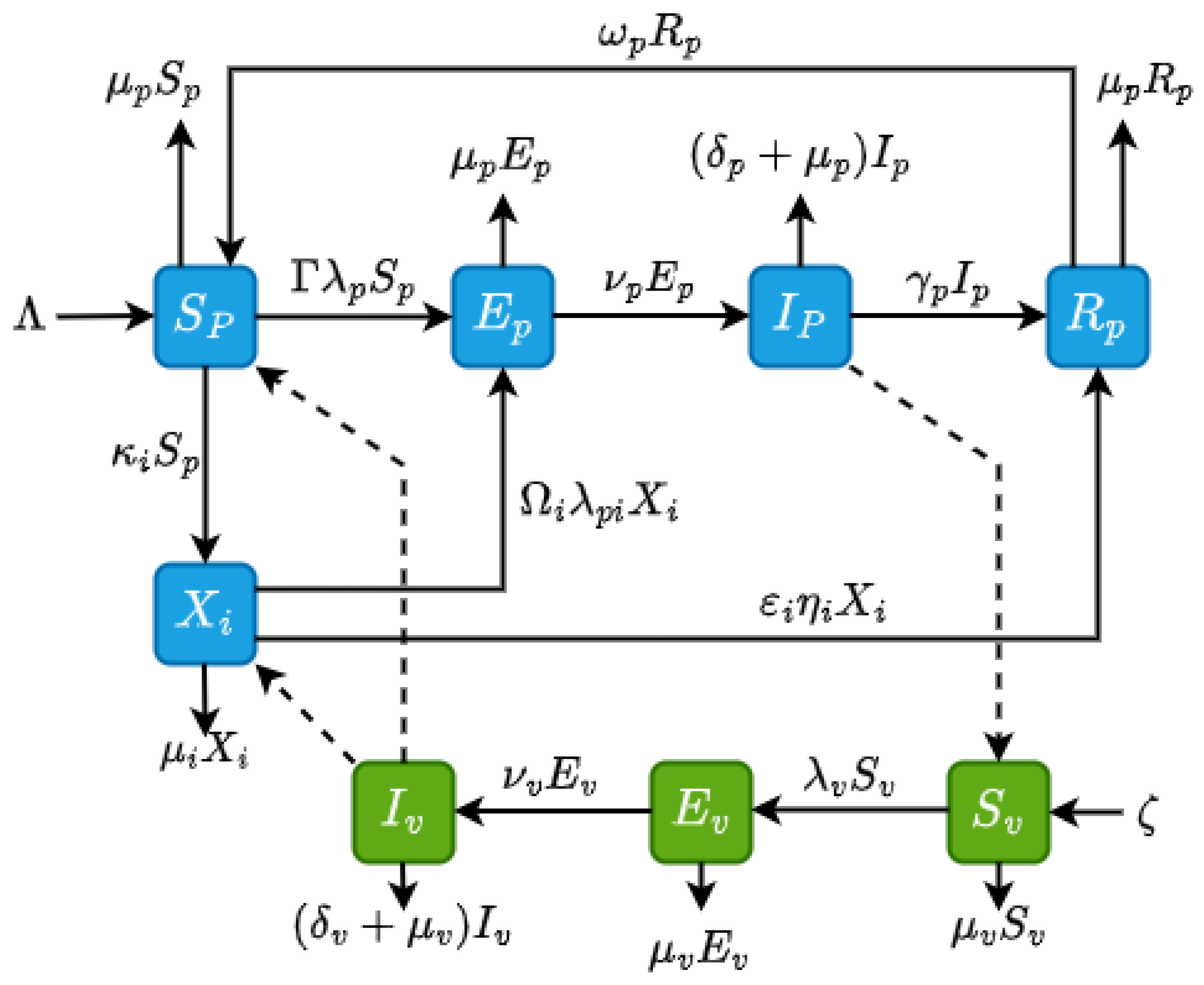

2. Methods: Model Formulation and Description

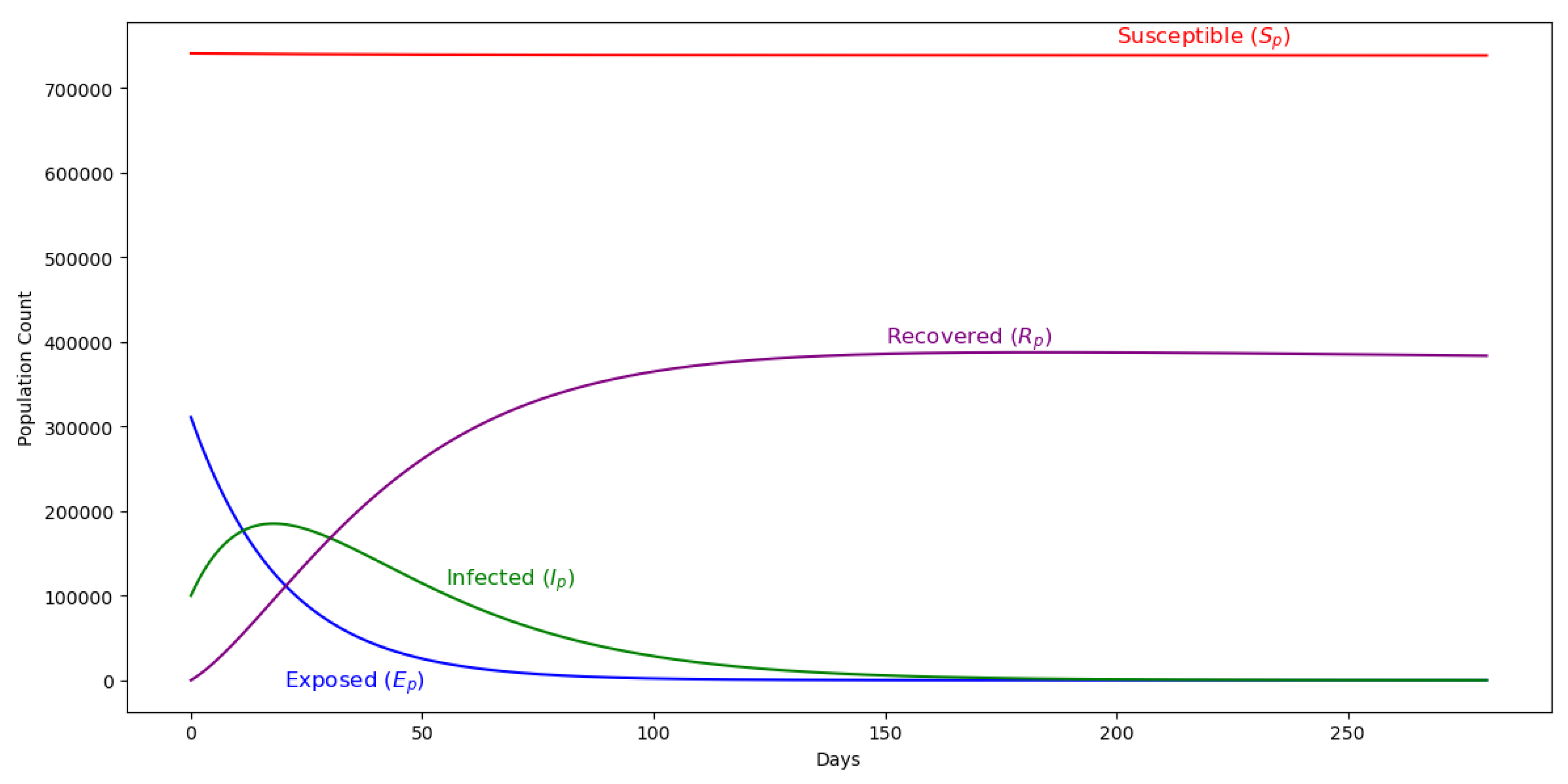

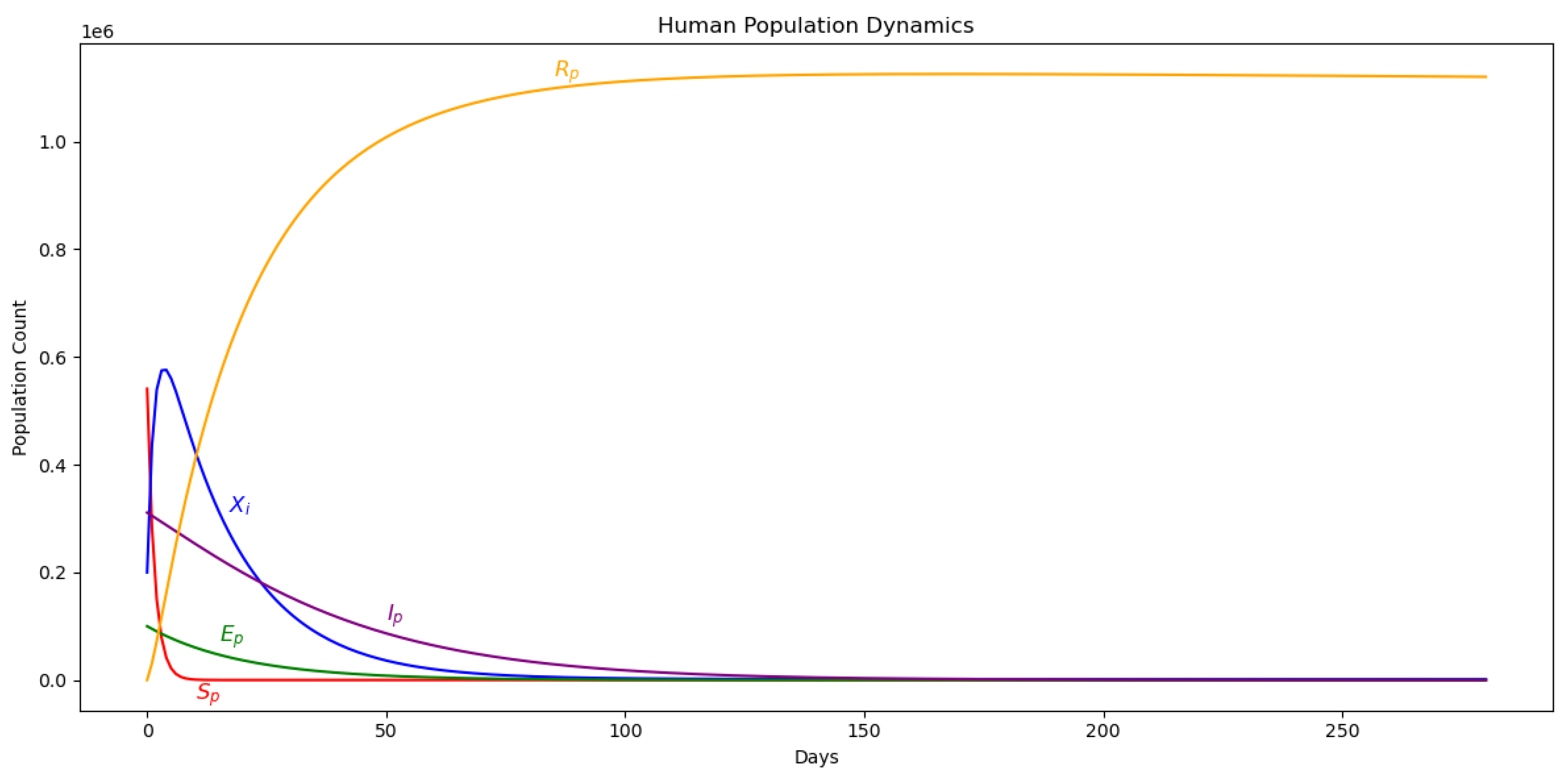

3. Results

3.1. Invariant Region

3.2. Positivity of the State Variables

3.3. Existence and Stability of Steady-State Solutions

3.4. Local Stability of the Disease-Free Equilibrium

3.5. Existence of Endemic Equilibria

3.6. Global Stability of the Endemic Equilibrium

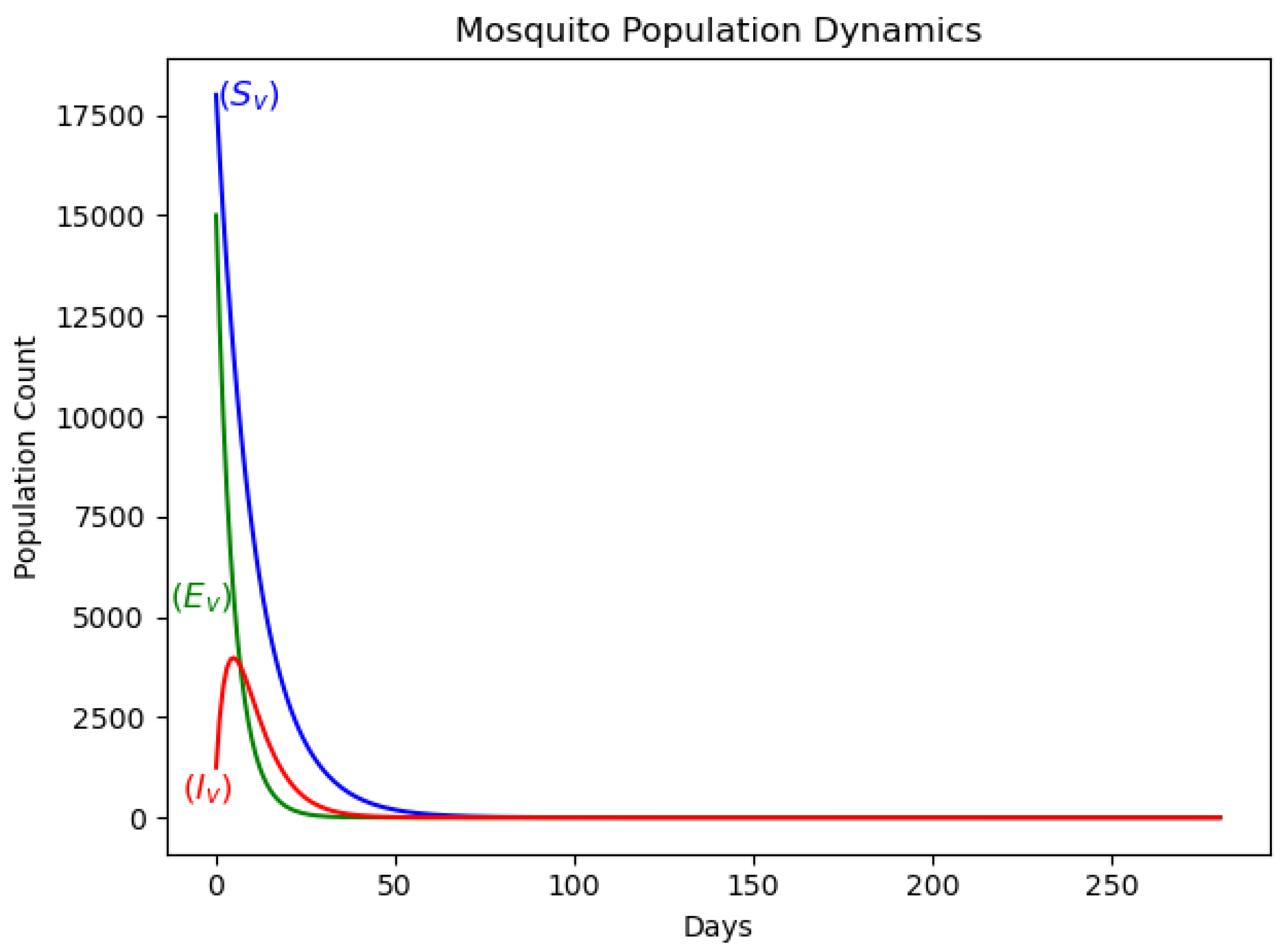

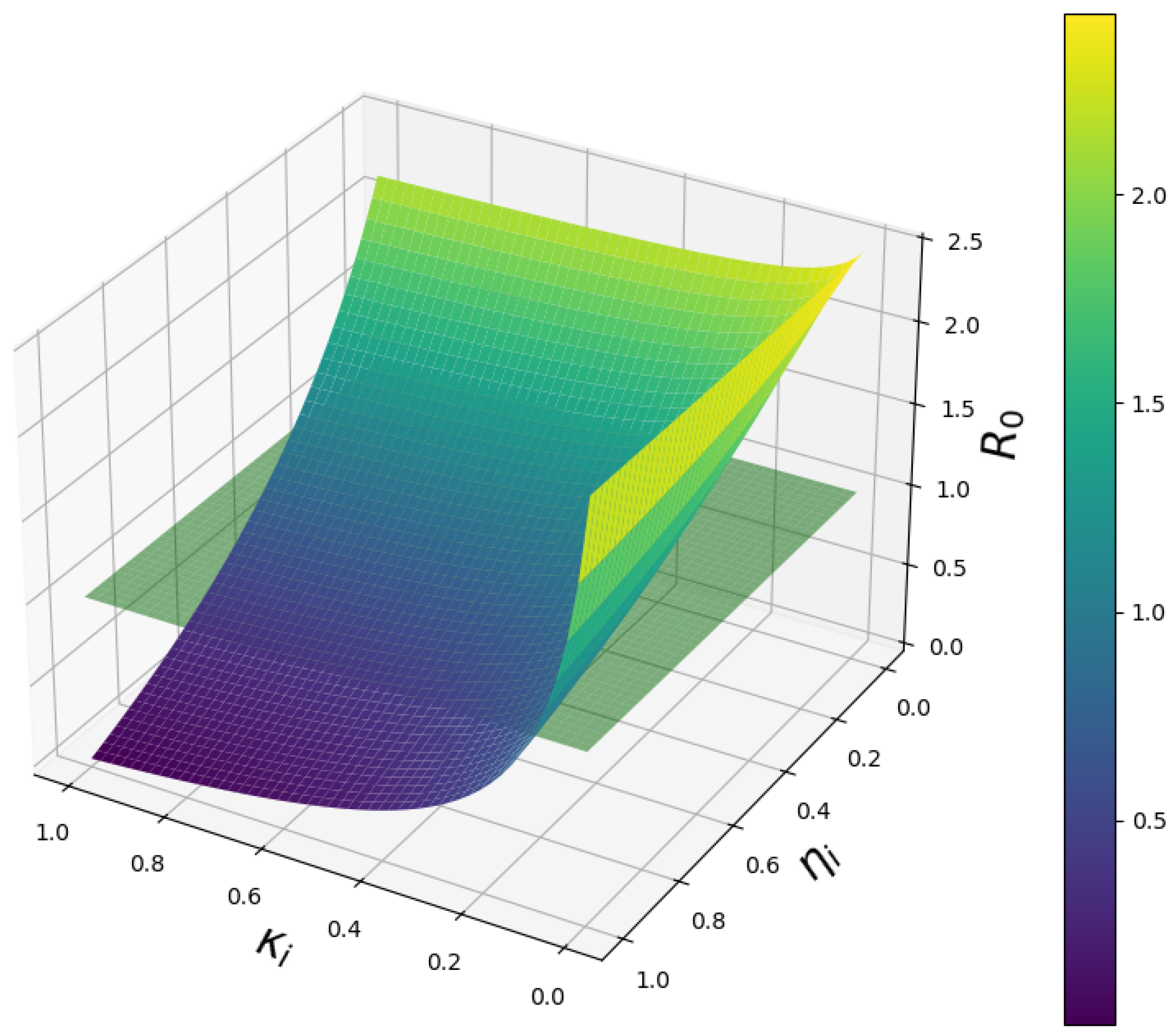

4. Model simulations and Discussions

5. Discussion and Conclusions

References

- WHO. Malaria, 2024.

- WHO. WHO guidelines for malaria; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2024; pp. 33–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. About Malaria, 2024.

- Schantz-Dunn, J.; Nour, N. Malaria and Pregnancy: A Global Health Perspective. REVIEWS IN OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY 2009, 2, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. World malaria report 2024, 2024.

- Guilbert, L.J.; Abbasi, M.; Mosmann, T.R. The immunology of pregnancy: Maternal defenses against infectious diseases; Malaria in Pregnancy Deadly Parasite, Susceptible Host; Taylor & Francis: London, 2001; pp. 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doritchamou, J.Y.A.; Aitken, E.H.; Luty, A.J.F. Editorial: Immunity to Parasitic Infections in Pregnancy. Frontiers in Immunology 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauserman, M.; Conroy, A.L.; North, K.; Patterson, J.; Bose, C.; Meshnick, S. An overview of malaria in pregnancy. Seminars in Perinatology 2019, 43, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apinjoh, T.O.; Ntui, V.N.; Chi, H.F.; Moyeh, M.N.; Toussi, C.T.; Mayaba, J.M.; Tangi, L.N.; Kwi, P.N.; Anchang-Kimbi, J.K.; Dionne-Odom, J.; et al. Intermittent preventive treatment with Sulphadoxine-Pyrimethamine (IPTp-SP) is associated with protection against sub-microscopic P. falciparum infection in pregnant women during the low transmission dry season in southwestern Cameroon: A Semi - longitudinal study. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0275370–e0275370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyeman, Y.N.; Newton, S.K.; Annor, R.B.; Owusu-Dabo, E. The Effectiveness of the Revised Intermittent Preventive Treatment with Sulphadoxine Pyrimethamine (IPTp-SP) in the Prevention of Malaria among Pregnant Women in Northern Ghana. Journal of Tropical Medicine 2020, 2020, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutman, J.; Kalilani, L.; Taylor, S.; Zhou, Z.; Wiegand, R.E.; Thwai, K.L.; Mwandama, D.; Khairallah, C.; Madanitsa, M.; Chaluluka, E.; et al. The A581G Mutation in the Gene Encoding Plasmodium falciparum Dihydropteroate Synthetase Reduces the Effectiveness of Sulfadoxine-Pyrimethamine Preventive Therapy in Malawian Pregnant Women. Journal of Infectious Diseases 2015, 211, 1997–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anchang-Kimbi, J.K.; Kalaji, L.N.; Mbacham, H.F.; Wepnje, G.B.; Apinjoh, T.O.; Ngole Sumbele, I.U.; Dionne-Odom, J.; Tita, A.T.N.; Achidi, E.A. Coverage and effectiveness of intermittent preventive treatment in pregnancy with sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine (IPTp-SP) on adverse pregnancy outcomes in the Mount Cameroon area, South West Cameroon. Malaria Journal 2020, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, S.; Sarkar, R.R.; Sinha, S. Mathematical models of malaria - a review. Malaria Journal 2011, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.L.; Battle, K.E.; Hay, S.I.; Barker, C.M.; Scott, T.W.; McKenzie, F.E. Ross, Macdonald, and a Theory for the Dynamics and Control of Mosquito-Transmitted Pathogens. PLoS Pathogens 2012, 8, e1002588–e1002588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, D.I.; Southworth, B.S.; Shi, X.; Chipman, J.W.; Githeko, A.K. A comparison of five malaria transmission models: benchmark tests and implications for disease control. Malaria Journal 2014, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pande, V.; Bahal, M.; Dua, J.; Gupta, A. Ronald Ross: Pioneer of Malaria Research and Nobel Laureate. Cureus 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngwa, G.A.; Shu, W.S. A mathematical model for endemic malaria with variable human and mosquito populations. Mathematical and Computer Modelling 2000, 32, 747–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitnis, N.; Cushing, J.M.; Hyman, J.M. Bifurcation Analysis of a Mathematical Model for Malaria Transmission. SIAM Journal on Applied Mathematics 2006, 67, 24–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danquah, B.A.; Chirove, F.; Banasiak, J. Effective and ineffective treatment in a malaria model for humans in an endemic region. Afrika Matematika 2019, 30, 1181–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayalew, A.; Molla, Y.; Woldegbreal, A. Modeling and Stability Analysis of the Dynamics of Malaria Disease Transmission with Some Control Strategies. Abstract and Applied Analysis 2024, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, M.; Lashari, A.A.; Li, X.Z. Biological control of malaria: A mathematical model. Applied Mathematics and Computation 2025, 2013, 7923–7939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwamtobe, P.M.; Abelman, S.; Tchuenche, M.J.; Kasambara, A. Optimal (Control of) Intervention Strategies for Malaria Epidemic in Karonga District, Malawi. Abstract and Applied Analysis 2014, 2014, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkhoff, G.; Rota, G.C. Ordinary Differential Equations, 4 ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Driessche, P.v.d.; Watmough, J. Reproduction numbers and sub-threshold endemic equilibria for compartmental models of disease transmission. Mathematical Biosciences 2002, 180, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adom-Konadu, A.; Lanor Sackitey, A.; Anokye, M. Local Stability Analysis Of Epidemic Models Using A Corollary Of Gershgorin’s Circle Theorem. Applied Mathematics E-Notes 2023, 23, 159–174. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, L.J. An Introduction to Mathematical Biology; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, 2007; pp. 162–163. [Google Scholar]

- LaSalle, J. Some Extensions of Liapunov’s Second Method. IRE Transactions on Circuit Theory 1960, 7, 520–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNFPA. Malawi, 2022.

- UNFPA. The State of the World’s Midwifery 2014 | United Nations Population Fund, 2022.

- Konlan, M. Modeling the Inflow of Exposed and Infected Migrants on the Dynamics of Malaria. European Journal of Mathematical Analysis 2024, 4, 7–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niger, A.M.; Gumel, A.B. Mathematical analysis of the role of repeated exposure on malaria transmission dynamics. Differential Equations and Dynamical Systems 2008, 16, 251–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Description |

|---|---|

| The rate of conception of pregnant women | |

| The rate of recruitment of mosquitoes through natural birth | |

| Natural death rate of pregnant women per capita | |

| The natural death rate of mosquitoes per capita | |

| Transfer rate of pregnant women from the exposed state to the infectious state | |

| The rate of transfer of mosquitoes from the exposed state to the infectious state | |

| The infectivity of mosquitoes | |

| The infectivity of pregnant women | |

| The man-biting rate of mosquitoes. | |

| The disease induced death rate per capita for pregnant women | |

| The disease induced death rate per capita for mosquitoes | |

| Recovery rate of pregnant women with partial immunity | |

| The rate of losing immunity and going back to the susceptible | |

| Treatment success rate of doses of IPTp-SP | |

| Fraction of pregnant women protected from malaria by IPTp-SP | |

| Fraction of pregnant women taking IPTp-SP |

| Parameter | Base Value | Source | Estimated Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0005948 | [28] | 0.188 | |

| 0.071 | [31] | 0.335 | |

| 0.07 | Assumed | 0.111 | |

| 0.94 | [30] | 0.977 | |

| [29] | 0.0984 | ||

| 0.00021 | [30] | 0.634 | |

| [30] | 0.490 | ||

| 0.00021 | [30] | 0.789 | |

| 0.001 | [30] | 0.223 | |

| 0.11346 | [30] | 0.257 | |

| [30] | 0.0555 | ||

| 0.091 | [30] | 0.223 | |

| [30] | 0.5000 | ||

| 0.64 | [5] | 0.159 | |

| 0.25 | Assumed | 0.133 | |

| 0.25 | Assumed | 0.633 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).