Submitted:

19 June 2025

Posted:

23 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Review

2.1. Brief Characterisation of the Non-Alcoholic Beverage Industry in Brazil

2.2. Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises and Sustainability

2.3. Sustainability Indicators and SMEs in the Beverage Industry

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Typology, Techniques, and Data Collection

3.2. Analysis of Responses and Consensus Level

4. Results and Analyses

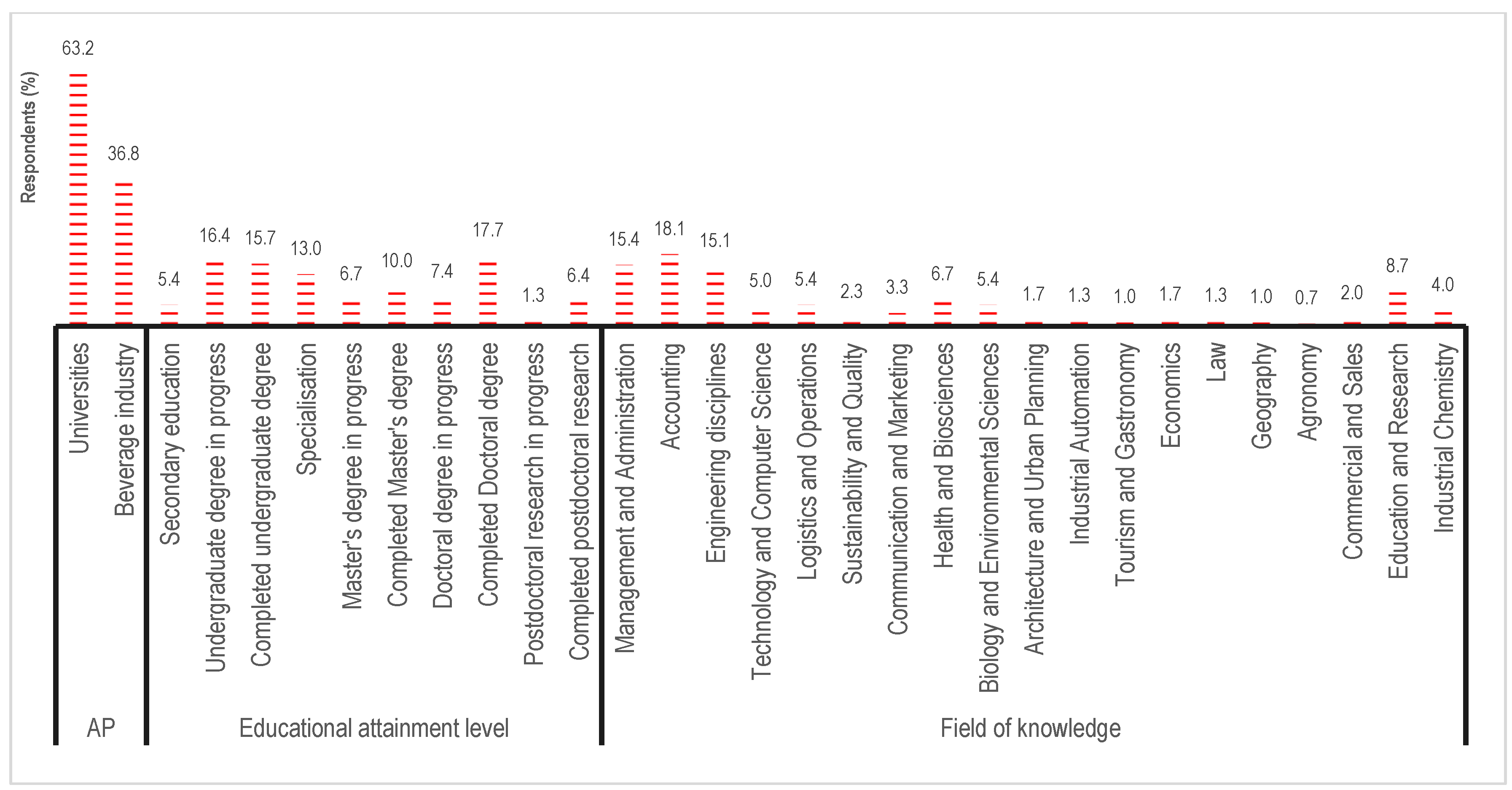

4.1. Analysis of Respondents’ Profile

4.2. Analysis of Reliability and Consensus Level

4.3. Set of Indicators for the Non-Alcoholic Beverage Industry

5. Final Considerations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variable | Company | Education Level | Knowledge Area |

| Company | 1 | 0.471** | -0.034 |

| Education Level | 0.471** | 1 | -0.105 |

| Knowledge Area | -0.034 | -0.105 | 1 |

| Sales Revenue | -0.049 | 0.023 | 0.01 |

| Operating Costs | -0.014 | 0.102 | -0.007 |

| Employee Wages and Benefits | 0.033 | 0.049 | 0.151** |

| Dividends and Interest on Equity Paid | 0.096 | -0.041 | 0.083 |

| Taxes and Levies Paid to Government | 0.085 | 0.073 | 0.081 |

| Community Investment | 0.135* | 0.058 | 0.164** |

| Private Employee Pension Plans | 0.095 | 0.015 | 0.183** |

| Government Incentives (Tax Credits0. Subsidies0. and others) | 0.028 | -0.114* | 0.102 |

| Lowest Wage Compared to Local Minimum Wage for the Category | 0.013 | -0.056 | -0.016 |

| Senior Management Hired from Local Community | 0.160** | 0.016 | 0.152** |

| Local Supplier Purchases and Contracts | 0.150** | 0.004 | 0.140* |

| Infrastructure Development Investment (Society) | 0.103 | -0.002 | 0.140* |

| Technological Changes in Productivity and Distribution | 0.049 | -0.093 | 0.057 |

| Economic Development in High-Poverty Areas (Society) | 0.195** | 0.055 | 0.091 |

| Availability of Products and Services for Low-Income Individuals | 0.075 | -0.127* | 0.064 |

| Indirect Jobs in Supplier or Distribution Chain | 0.112 | -0.023 | 0.098 |

| Non-Renewable and Renewable Materials | 0.035 | 0.089 | 0.054 |

| Recycled Materials | 0.064 | 0.008 | 0.011 |

| Energy from Non-Renewable and Renewable Sources | 0.052 | 0.118* | 0.007 |

| Surface and Groundwater | -0.002 | 0.015 | 0.088 |

| Water Recycled and Reused by the Organisation | 0.082 | 0.115* | 0.063 |

| Geographical Location of the Company | 0.066 | -0.087 | 0.097 |

| Size of Operational Unit | 0.018 | -0.117* | 0.143* |

| Introduction of Polluting Substances | 0.037 | 0.003 | 0.087 |

| Introduction of Invasive0. Harmful0. and Pathogenic Species | 0.038 | 0.013 | -0.01 |

| Species Reduction | 0.051 | 0.004 | 0.006 |

| Protected or Restored Habitat | 0.237** | 0.087 | 0.139* |

| Emissions of Ozone-Depleting Substances (ODS) | 0.029 | -0.02 | 0.022 |

| Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) | 0.048 | 0.004 | 0.057 |

| Particulate Matter (PM) | 0.062 | -0.015 | 0.029 |

| Hazardous Air Pollutants (HAPs) | 0.054 | 0.03 | 0.006 |

| Reused and Recycled Waste | 0.061 | 0.092 | 0.016 |

| Incineration Waste | 0.124* | 0.031 | 0.06 |

| Waste Sent to Landfills | 0.077 | 0.042 | 0.018 |

| Waste Stored On-Site | 0.091 | -0.012 | 0.073 |

| Environmental Impacts Caused by Products | 0.055 | 0.084 | 0.063 |

| Recovered Products and Packaging | 0.085 | 0.048 | 0.053 |

| Fines and Sanctions for Environmental Non-Compliance | 0.074 | 0.041 | 0.041 |

| Complaints Related to Environmental Impacts | 0.103 | -0.054 | 0.092 |

| Environmental Prevention and Management Expenditure | 0.145* | 0.057 | 0.011 |

| Suppliers Selected Based on Environmental Criteria | 0.099 | 0.037 | 0.027 |

| Number of Employees | 0.047 | -0.07 | 0.033 |

| Employee Turnover | -0.047 | -0.097 | -0.039 |

| Statutory Benefits Granted to Employees | 0.009 | -0.026 | 0.095 |

| Employees with Occupational Illnesses | 0.037 | -0.05 | 0.031 |

| Employee Training | -0.007 | -0.043 | 0.057 |

| Retirement or Redundancy Programs | 0.088 | 0.003 | 0.077 |

| Employee Performance Reviews | -0.03 | -0.101 | 0.039 |

| Employees by Functional Category | 0.102 | -0.031 | 0.129* |

| Suppliers Selected Based on Labour Practices | 0.096 | 0.031 | 0.133* |

| Complaints Related to Labour Practices | 0.131* | 0.038 | 0.027 |

| Complaints Related to Human Rights | 0.083 | 0.012 | -0.019 |

| Operations with Human Rights Violations | -0.025 | 0.019 | 0.022 |

| Discrimination Practices | 0.012 | 0.05 | -0.006 |

| Operations and Suppliers with Child Labour Risks | 0.049 | 0.099 | -0.025 |

| Occurrence of Forced or Slave Labour | 0.004 | 0.073 | -0.018 |

| Employee Training on Human Rights Policies | 0.121* | 0.037 | -0.096 |

| Violation of Indigenous and Traditional Peoples’ Rights | -0.008 | 0.046 | -0.005 |

| Social Impact Assessments via Participatory Processes | 0.119* | -0.017 | 0.047 |

| Environmental Impact Assessments | 0.125* | 0.078 | 0.031 |

| Public Disclosure of Environmental and Social Impact Assessments | 0.263** | 0.11 | 0.035 |

| Development Programs Based on Local Needs | 0.172** | 0.058 | 0.062 |

| Operations Subject to Corruption Risk Assessments | 0.11 | 0.107 | 0.094 |

| Anti-Corruption Policies and Procedures | 0.149* | 0.118* | 0.014 |

| Employees Trained in Anti-Corruption Measures | 0.140* | 0.051 | 0.036 |

| Corruption Cases and Measures Taken | 0.046 | 0.043 | 0.06 |

| Contributions to Political Parties | 0.094 | -0.019 | -0.029 |

| Legal Actions for Unfair Competition | 0.103 | 0.022 | -0.089 |

| Fines and Sanctions for Legal Non-Compliance | 0.195** | 0.073 | -0.05 |

| Products with Certification and Labelling | -0.005 | -0.088 | 0.147* |

| Customer Satisfaction Surveys | 0.02 | -0.057 | 0.065 |

| Sale of Banned or Controversial Products | -0.029 | -0.002 | -0.004 |

| Non-Compliant Marketing Communications | -0.002 | -0.034 | -0.004 |

| Complaints Regarding Privacy Violations and Customer Data Loss | 0.041 | -0.03 | 0.014 |

Appendix B

| Likert Scale | |||||||||

| Indicators | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | (µx) | SD | CV | Cns (X) |

| Sales Revenue | 0 | 7 | 18 | 79 | 195 | 4.5 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.8 |

| Operating Expenditure | 1 | 2 | 13 | 79 | 204 | 4.6 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.8 |

| Employee Wages and Benefits | 0 | 6 | 25 | 91 | 177 | 4.5 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.7 |

| Dividends and Interest on Equity | 2 | 18 | 58 | 125 | 96 | 4.0 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.7 |

| Taxes and Levies Paid to Government | 4 | 11 | 49 | 128 | 107 | 4.1 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.7 |

| Community Investment | 4 | 13 | 58 | 88 | 136 | 4.1 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 0.7 |

| Private Pension Plans | 8 | 30 | 90 | 97 | 74 | 3.7 | 1.0 | 0.3 | 0.6 |

| Government Incentives | 6 | 20 | 60 | 103 | 110 | 4.0 | 1.0 | 0.3 | 0.7 |

| Wage vs. Local Minimum Wage | 66 | 49 | 55 | 81 | 48 | 3.0 | 1.4 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| Senior Management from Local Community | 6 | 36 | 68 | 100 | 89 | 3.8 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 0.6 |

| Purchases from Local Suppliers | 2 | 14 | 66 | 119 | 98 | 4.0 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.7 |

| Infrastructure Investment in Society | 0 | 6 | 48 | 118 | 127 | 4.2 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0.7 |

| Technological Innovations (Production & Distribution) | 2 | 15 | 32 | 130 | 120 | 4.2 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.7 |

| Regional Development | 3 | 6 | 45 | 97 | 148 | 4.3 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.7 |

| Products and Services for Low-Income Individuals | 2 | 10 | 51 | 92 | 144 | 4.2 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.7 |

| Indirect Job Creation | 2 | 10 | 51 | 110 | 126 | 4.2 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.7 |

| Non-Renewable and Renewable Materials | 8 | 8 | 27 | 100 | 156 | 4.3 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.7 |

| Recycled Materials | 1 | 4 | 11 | 76 | 207 | 4.6 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 0.8 |

| Energy from Non-Renewable and Renewable Sources | 8 | 3 | 21 | 84 | 183 | 4.4 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.7 |

| Surface and Groundwater | 3 | 9 | 32 | 96 | 159 | 4.3 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.7 |

| Recycled and Reused Water | 1 | 4 | 16 | 74 | 204 | 4.6 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 0.8 |

| Geographical Location of the Company | 4 | 8 | 33 | 122 | 132 | 4.2 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.7 |

| Size of Operational Unit | 5 | 17 | 46 | 135 | 96 | 4.0 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.7 |

| Consumption of Polluting Substances | 48 | 14 | 31 | 69 | 137 | 3.8 | 1.5 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| Use of Invasive, Harmful, and Pathogenic Species | 53 | 22 | 29 | 57 | 138 | 3.7 | 1.5 | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| Species Reduction | 54 | 27 | 27 | 61 | 130 | 3.6 | 1.5 | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| Protected or Restored Habitat | 7 | 12 | 25 | 60 | 195 | 4.4 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 0.6 |

| Emissions of Ozone-Depleting Substances (ODS) | 42 | 9 | 15 | 47 | 186 | 4.1 | 1.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) | 36 | 12 | 18 | 60 | 173 | 4.1 | 1.4 | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| Particulate Matter (PM) Generation | 35 | 14 | 27 | 79 | 144 | 3.9 | 1.3 | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| Hazardous Air Pollutants (HAPs) | 40 | 6 | 23 | 59 | 171 | 4.1 | 1.4 | 0.3 | 0.4 |

| Reused and Recycled Waste | 0 | 1 | 9 | 72 | 217 | 4.7 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.8 |

| Incineration Waste | 7 | 21 | 34 | 107 | 130 | 4.1 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 0.6 |

| Waste Sent to Landfills | 10 | 14 | 22 | 99 | 154 | 4.2 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 0.6 |

| On-Site Waste Storage | 8 | 14 | 32 | 104 | 141 | 4.2 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 0.7 |

| Environmental Impact of Products | 17 | 9 | 9 | 54 | 210 | 4.4 | 1.1 | 0.2 | 0.6 |

| Recovered Product Packaging | 4 | 2 | 15 | 89 | 189 | 4.5 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.7 |

| Environmental Fines and Sanctions | 7 | 5 | 17 | 80 | 190 | 4.5 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.7 |

| Environmental Complaints | 6 | 5 | 20 | 88 | 180 | 4.4 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.7 |

| Environmental Prevention and Management Expenditure | 1 | 2 | 27 | 91 | 178 | 4.5 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.7 |

| Supplier Environmental Policies | 2 | 4 | 34 | 85 | 174 | 4.4 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0.7 |

| Number of Employees | 3 | 16 | 28 | 123 | 129 | 4.2 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.7 |

| Employee Turnover | 14 | 19 | 43 | 88 | 135 | 4.0 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 0.6 |

| Statutory Employee Benefits | 1 | 3 | 30 | 93 | 172 | 4.4 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.7 |

| Employees with Occupational Illnesses | 16 | 12 | 36 | 100 | 135 | 4.1 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 0.6 |

| Employee Training | 2 | 1 | 22 | 80 | 194 | 4.5 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.8 |

| Retirement or Redundancy Programs | 3 | 6 | 56 | 94 | 140 | 4.2 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.7 |

| Employee Performance | 4 | 2 | 32 | 103 | 158 | 4.4 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0.7 |

| Employees by Functional Category | 5 | 10 | 46 | 115 | 123 | 4.1 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.7 |

| Suppliers Selected Based on Labour Practices | 4 | 5 | 38 | 100 | 152 | 4.3 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.7 |

| Labour Practice Complaints | 11 | 8 | 29 | 106 | 145 | 4.2 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 0.7 |

| Human Rights Complaints | 8 | 6 | 27 | 86 | 172 | 4.4 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.7 |

| Operations with Human Rights Violations | 30 | 7 | 21 | 58 | 183 | 4.2 | 1.3 | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| Discrimination Practices | 31 | 5 | 19 | 56 | 188 | 4.2 | 1.3 | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| Supplier Operations with Child Labour Risks | 32 | 6 | 13 | 53 | 195 | 4.2 | 1.3 | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| Occurrence of Forced/Slave Labour | 35 | 4 | 15 | 39 | 206 | 4.3 | 1.3 | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| Employee Training on Human Rights Policies | 7 | 1 | 27 | 81 | 183 | 4.4 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.7 |

| Violation of Indigenous and Traditional Peoples’ Rights | 38 | 6 | 24 | 58 | 173 | 4.1 | 1.4 | 0.3 | 0.4 |

| Social Impact Assessments via Participatory Processes | 3 | 4 | 33 | 95 | 164 | 4.4 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0.7 |

| Environmental Impact Assessments | 0 | 3 | 16 | 72 | 208 | 4.6 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.8 |

| Public Disclosure of Environmental and Social Impacts | 1 | 5 | 33 | 82 | 178 | 4.4 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0.7 |

| Local Development Programs | 2 | 5 | 30 | 95 | 167 | 4.4 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0.7 |

| Operations Assessed for Corruption Risks | 3 | 6 | 27 | 71 | 192 | 4.5 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0.7 |

| Anti-Corruption Policies and Procedures | 1 | 4 | 18 | 68 | 208 | 4.6 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.8 |

| Employees Trained in Anti-Corruption Measures | 2 | 6 | 30 | 82 | 179 | 4.4 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0.7 |

| Corruption Cases and Measures Taken | 7 | 9 | 22 | 72 | 189 | 4.4 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.7 |

| Contributions to Political Parties | 70 | 56 | 50 | 49 | 74 | 3.0 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| Legal Actions for Unfair Competition | 25 | 29 | 44 | 84 | 117 | 3.8 | 1.3 | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| Fines and Sanctions for Legal Non-Compliance | 22 | 15 | 32 | 80 | 150 | 4.1 | 1.2 | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| Products with Certification and Labelling | 2 | 1 | 14 | 71 | 211 | 4.6 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 0.8 |

| Customer Satisfaction | 1 | 3 | 24 | 83 | 188 | 4.5 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.7 |

| Sale of Banned or Controversial Products | 41 | 12 | 27 | 69 | 150 | 3.9 | 1.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| Non-Compliant Marketing Communications | 20 | 11 | 41 | 94 | 133 | 4.0 | 1.2 | 0.3 | 0.6 |

| Complaints Regarding Privacy and Data Loss | 13 | 5 | 36 | 70 | 175 | 4.3 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 0.6 |

References

- Gazzola, P.; Pavione, E.; Amelio, S.; Mauri, M. Sustainable Strategies and Value Creation in the Food and Beverage Sector: The Case of Large Listed European Companies. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- Fatunnisa, H.; Hamdani, A.; Permana, I. Exploring the Relationship Between Corporate Social Responsibility and Corporate Sustainability within the Food and Beverage Industry. In Proceedings of the The 6th International Conference on Business, Economics, Social Sciences, and Humanities 2023; 2023; pp. 1085–1090. [CrossRef]

- Halawa, A. Prospective Health Outcomes of Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Consumption Patterns Associated with Sociodemographic and Ethnic Factors among Chinese Adults. Food Science and Engineering 2024, 63–79. [CrossRef]

- Marrucci, L.; Daddi, T.; Iraldo, F. Identifying the Most Sustainable Beer Packaging through a Life Cycle Assessment. Science of the Total Environment 2024, 948. [CrossRef]

- Küchler, R.; Nicolai, B.M.; Herzig, C. Towards a Sustainability Management Tool for Food Manufacturing Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises—Insights from a Delphi Study. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 2023, 30, 589–604. [CrossRef]

- Natalie, H.C.; Bangsawan, S.; Husna, N. Driving Sustainable Business Performance: The Impact of Green Innovation on Food & Beverage SMEs in Bandar Lampung City. International Journal of Business and Applied Economics 2024, 3, 371–384. [CrossRef]

- Mwanaumo, E.T.; Mwanza, B.G. Assessment of the Drivers and Barriers to Adoption of Green Supply Chain Management Practices: A Case of the Beverage Manufacturing Industry. International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science (IJRISS) 2024, 8. [CrossRef]

- Tyler, B.B.; Lahneman, B.; Cerrato, D.; Cruz, A.D.; Beukel, K.; Spielmann, N.; Minciullo, M. Environmental Practice Adoption in SMEs: The Effects of Firm Proactive Orientation and Regulatory Pressure. Journal of Small Business Management 2024, 62, 2211–2246. [CrossRef]

- Zain, R.M.; Ramli, A.; Zain, M.Z.M.; Yekini, L.S.; Musa, A.; Rahim, M.N.A.; Dirie, A.N.; Aziz, N.I.C. An Investigation of the Barriers and Drivers for Implementing Green Supply Chain in Malaysian Food and Beverage SMEs: A Qualitative Perspective. WSEAS Transactions on Business and Economics 2024, 21, 2169–2189. [CrossRef]

- Dey, P.K.; Yang, G. liang; Malesios, C.; De, D.; Evangelinos, K. Performance Management of Supply Chain Sustainability in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises Using a Combined Structural Equation Modelling and Data Envelopment Analysis. Comput Econ 2021, 58, 573–613. [CrossRef]

- Feil, A.; Traesel, E.G. indicadores de sustentabilidade empregados na avaliação do desempenho da indústria de bebidas no Brasil. Revista de Estudos Interdisciplinares 2024, 6, 01–23. [CrossRef]

- Ministério da Agricultura e Pecuária. Anuário das bebidas não alcoólicas 2024 ano referência 2023; MAPA/SDA: Brasília, 2024; ISBN 978-85-7991-239-9.

- Foodconnection. Tendências Em Bebidas Não Alcoólicas: 7 Novidades Para Conhecer e Se Inspirar. Available online: https://www.foodconnection.com.br/alimentosebebidas/bebidas/fique-por-dentro-do-setor-de-bebidas-nao-alcoolicas-veja-dados-sobre-o-mercado-inovacoes-e/ (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Statista. Bebidas Não Alcoólicas No Brasil. Available online: https://www.statista.com/topics/10588/non-alcoholic-beverages-in-brazil/ (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Portal da industria. Perfil Setorial Da Indústria Available online: https://perfilsetorialdaindustria.portaldaindustria.com.br/listar/11-bebidas/producao (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Abu-Reidah, I.M. Carbonated Beverages. In GALANAKIS, Charis M. Trends in non-alcoholic beverages; Academic Press: Austria, 2020. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/351707747_Market_ Trend_in_ Beverage_Industry (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Kumar, S.; Chand, K. Market Trend in Beverage Industry; 2021; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/351707747_Market_ Trend_in_ Beverage_Industry (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Brownbill, A.L.; Braunack-Mayer, A.J.; Miller, C.L. What Makes a Beverage Healthy? A Qualitative Study of Young Adults’ Conceptualisation of Sugar-Containing Beverage Healthfulness. Appetite 2020, 150. [CrossRef]

- Arroque, C.; Hoppe, L.; Alvim, A.M.; Vitt, F. Análise dos indicadores ambientais na indústria de bebidas do grupo VONPAR SA sob a ótica da NBR ISO 14001. In Proceedings of the 8o Encontro de Economia Gaúcha; 2016. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10923/10457 (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Lorena, E.M.G.; Santos, Í.G.S. dos; Gabriel, F.Ã.; Bezerra, A.P.X. de G.; Rodriguez, M.A.M.; Moraes, A.S. Analysis of the Procedural and Wastewater Treatment at a beverage Bottling Industry in the State of Pernambuco, Brazil. GEAMA Journal 2016, 2, 466–472. Available online: https://www.journals.ufrpe.br/index.php/geama/article/view/948 (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Giroto Rebelato, M.; Lucas Madaleno, L.; Marize Rodrigues, A. Avaliação do desempenho ambiental dos processos industriais de usinas sucroenergéticas: um estudo na bacia hidrográfica do Rio Mogi Guaçu. Revista de Administração da UNIMEP 2014, 12. Available online: https://biblat.unam.mx/hevila/RevistadeadministracaodaUNIMEP/2014/vol12/no3/6.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Santini, E.; Caputo, A. PMEs e Responsabilidade Social. In Concise Encyclopedia of Corporate Social Responsibility; Edward Elgar Publishing, 2024; pp. 146–150.

- Penjišević, A.; Somborac, B.; Anufrijev, A.; Aničić, D. Achieved results and perspectives for further development of small and medium-sized enterprises: statistical findings and analysis. Oditor 2024, 10, 313–329. [CrossRef]

- Andriyani, F.; Rochayatun, S. Corporate social responsibility in small medium enterprises: a scoping literature review. Jurnal Ekonomi Akuntansi Dan Manajemen 2023, 22. [CrossRef]

- Bamidele Micheal Omowole; Amarachi Queen Olufemi-Phillips; Onyeka Chrisanctus Ofodile; Nsisong Louis Eyo-Udo; Somto Emmanuel Ewim Conceptualizing Green Business Practices in SMEs for Sustainable Development. International Journal of Management & Entrepreneurship Research 2024, 6, 3778–3805. [CrossRef]

- Hörisch, J.; Johnson, M.P.; Schaltegger, S. Implementation of Sustainability Management and Company Size: A Knowledge-Based View. Bus Strategy Environ 2015, 24, 765–779. [CrossRef]

- Prasanna, R.P.I.R.; Jayasundara, J.M.S.B.; Gamage, S.K.N.; Ekanayake, E.M.S.; Rajapakshe, P.S.K.; Abeyrathne, G.A.K.N.J. Sustainability of SMEs in the Competition: A Systemic Review on Technological Challenges and SME Performance. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 2019, 5. [CrossRef]

- Moursellas, A.; De, D.; Wurzer, T.; Skouloudis, A.; Reiner, G.; Chaudhuri, A.; Manousidis, T.; Malesios, C.; Evangelinos, K.; Dey, P.K. Sustainability Practices and Performance in European Small-and-Medium Enterprises: Insights from Multiple Case Studies. Circular Economy and Sustainability 2023, 3, 835–860. [CrossRef]

- Chong, S.C.; Kaliappen, N. Antecedents and Consequences for Sustainability in Malaysian Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs). Social Responsibility Journal 2025, 21, 987–1008. [CrossRef]

- Indriastuty, N.; Made, N.; Priliandani, I.; Sutadji, I.M.; Setiyaningsih, T.A.; Gunawan, A. Opportunities and Challenges: Implementation of Sustainable Business Practices in MSME’s. In Proceedings of the 1st Al Banjari Postgraduate International Conference: Multidisciplinary Perspective on Sustainable Development 2024; 2024; pp. 31–37. [CrossRef]

- Kurtanović, M.; Kadušić, E. Catalysts of Sustainability: The Transformative Role of Small and Medium Enterprises in ESG Practices of EU Candidate Countries. Journal of Forensic Accounting Profession 2024, 4, 34–51. [CrossRef]

- Binaluyo, J.P. Exploring the Challenges and Opportunities for Sustainability Reporting Adoption among Small and Medium Enterprises: A Case in a Developing Country in Asia. Journal of Infrastructure, Policy and Development 2024, 8, 8736. [CrossRef]

- Carlsson, R.; Nevzorova, T. Measuring Sustainable Transformation of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises Using Management Systems Standards. Bus Strategy Environ 2024. [CrossRef]

- Álvarez Jaramillo, J.; Zartha Sossa, J.W.; Orozco Mendoza, G.L. Barriers to Sustainability for Small and Medium Enterprises in the Framework of Sustainable Development—Literature Review. Bus Strategy Environ 2019, 28, 512–524. [CrossRef]

- Radzi, A.I.N.; Jasni, N.S. Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs) Advancing Business Sustainability Toward SDGs: A New Force Driving Positive Change. International Journal of Academic Research in Accounting, Finance and Management Sciences 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Parastatidou, G.; Chatzis, V. A Meta-Indicator for the Assessment of Misleading Sustainability Claims. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.E.; Drozdov, D.O. Sustainability Indicators of Regional Industrial Systems. Herald of Omsk University. Series: Economics 2024, 22, 14–24. [CrossRef]

- Saygili, E.; Uye Akcan, E.; Ozturkoglu, Y. An Exploratory Analysis of Sustainability Indicators in Turkish Small- and Medium-Sized Industrial Enterprises. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Bechir, M.H.; Martinez, D.F.-; Aguera, A.L.- Sustainability Indicators Correlation Matrix. Int J Res Appl Sci Eng Technol 2024, 12, 616–627. [CrossRef]

- Muniz, R.N.; da Costa Júnior, C.T.; Buratto, W.G.; Nied, A.; González, G.V. The Sustainability Concept: A Review Focusing on Energy. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- D’Angiò, A.; Acampora, A.; Merli, R.; Lucchetti, M.C. ESG Indicators and SME: Towards a Simplified Framework for Sustainability Reporting. In Innovation, Quality and Sustainability for a Resilient Circular Economy; Springer Nature, 2022; pp. 325–331. [CrossRef]

- Mengistu, A.T.; Panizzolo, R. Tailoring Sustainability Indicators to Small and Medium Enterprises for Measuring Industrial Sustainability Performance. Measuring Business Excellence 2023, 27, 54–70. [CrossRef]

- Amienyo, D. Life cycle sustainability assessment in the uk beverage sector, University of Manchester, 2012. Available online: https://pure.manchester.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/54527550/FULL_TEXT.PDF(accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Haseli, G.; Nazarian-Jashnabadi, J.; Shirazi, B.; Hajiaghaei-Keshteli, M.; Moslem, S. Sustainable Strategies Based on the Social Responsibility of the Beverage Industry Companies for the Circular Supply Chain. Eng Appl Artif Intell 2024, 133. [CrossRef]

- Ugrinov, S.; Ćoćkalo, D.; Bakator, M. Optimization and Sustainability of Supply Chains in the Food and Beverage Industry. Ekonomika 2024, 70, 59–78. [CrossRef]

- Budianto, R.; Isnalita Controlling Social Problems and Environmental Changes through Sustainability: Evidence from Indonesian Beverage Companies. International Journal of Management and Sustainability 2024, 13, 232–252. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Sanchez, C.; Sellers-Rubio, R. Sustainability in the Beverage Industry: A Research Agenda from the Demand Side. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2021, 13, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- DEMO, P. Avaliação Qualitativa; 1st ed.; Autores Associados: Campinas, 2022; ISBN 9786588717691.

- Marconi, M. de A.; Lakatos, E.M. Fundamentos de Metodologia Científica; 8th ed.; Atlas: São Paulo, 2017; ISBN 9788597010121.

- Hair, J.F.; Wolfinbarger, M.F.; Ortinau, D.J.; Bush, R.P. Fundamentos de Pesquisa de Marketing; Bookman: Porto Alegre, RS, 2010; ISBN 9788577806249.

- Marrucci, L.; Daddi, T.; Iraldo, F. Creating Environmental Performance Indicators to Assess Corporate Sustainability and Reward Employees. Ecol Indic 2024, 158. [CrossRef]

- GRI Standart Consolidated GRI Standards. Available online: https://www.globalreporting.org/how-to-use-the-gri-standards/gri-standards-portuguese-translations/ (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Tastle, W.J.; Wierman, M.J. Consensus and Dissention: A Measure of Ordinal Dispersion. International Journal of Approximate Reasoning 2007, 45, 531–545. [CrossRef]

- Giannarou, L.; Zervas, E. Using Delphi Technique to Build Consensus in Practice; International Journal of Business Science & Applied Management (IJBSAM) 2014, 9, 65-82. Available online: https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/190657/1/09_2_p65-82.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Keeney, S.; Hasson, F.; McKenna, H. A Modified Delphi Case Study. In The Delphi Technique in Nursing and Health Research; Keeney, S., Hasson, F.H., McKenna, H., Eds.; Wiley: Oxford, 2011; pp. 125–141.

- Hasson, F.; Keeney, S.; McKenna, H. Research Guidelines for the Delphi Survey Technique. J Adv Nurs 2000, 32, 1008–1015. [CrossRef]

- Doria, M. de F.; Boyd, E.; Tompkins, E.L.; Adger, W.N. Using Expert Elicitation to Define Successful Adaptation to Climate Change. Environ Sci Policy 2009, 12, 810–819. [CrossRef]

- Brenner, M.; Browne, C.; Gallen, A.; Byrne, S.; White, C.; Nolan, M. Development of a Suite of Metrics and Indicators for Children’s Nursing Using Consensus Methodology. J Clin Nurs 2019, 28, 2589–2598. [CrossRef]

- Scarparo, A.F.; Laus, A.M.; Azevedo, A.L. de C.S.; Freitas, M.R.I. de; Gabriel, C.S.; Chaves, L.D.P. Reflexões sobre o uso da técnica delphi em pesquisas na enfermagem. Revista da Rede de Enfermagem do Nordeste 2012, 13, 242–251. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/3240/324027980026.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Gebara, C.H.; Thammaraksa, C.; Hauschild, M.; Laurent, A. Selecting Indicators for Measuring Progress towards Sustainable Development Goals at the Global, National and Corporate Levels. Sustain Prod Consum 2024, 44, 151–165. [CrossRef]

- Gunnarsdóttir, I.; Davíðsdóttir, B.; Worrell, E.; Sigurgeirsdottir, S. It Is Best to Ask: Designing a Stakeholder-Centric Approach to Selecting Sustainable Energy Development Indicators. Energy Res Soc Sci 2021, 74. [CrossRef]

- Trucillo, P.; Erto, A. Sustainability Indicators for Materials and Processes. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Taber, K.S. The Use of Cronbach’s Alpha When Developing and Reporting Research Instruments in Science Education. Res Sci Educ 2018, 48, 1273–1296. [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics; 5th ed.; SAGE, 2018. Available online: http://repo.darmajaya.ac.id/5678/1/Discovering%20Statistics%20Using%20IBM%20SPSS%20Statistics%20(%20PDFDrive%20).pdf (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Schober, P.; Schwarte, L.A. Correlation Coefficients: Appropriate Use and Interpretation. Anesth Analg 2018, 126, 1763–1768. [CrossRef]

- Pimentel-Gomes, F. Curso de Estatística Experimental; 15th ed.; FEALQ: Piracicaba, 2009.

- Sangwan, K.S.; Bhakar, V.; Digalwar, A.K. A Sustainability Assessment Framework for Cement Industry – a Case Study. Benchmarking: An International Journal 2019, 26, 470–497. [CrossRef]

- Loza-Aguirre, E.; Segura Morales, M.; Roa, H.N.; Montenegro Armas, C. Unveiling Unbalance on Sustainable Supply Chain Research: Did We Forget Something? In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Technology & Systems (ICITS 2018); Springer Nature, 2018; pp. 264–274. [CrossRef]

- Isabel Sanchez-Hernandez, M.; Hourneaux, F.; Dias, B.G. Sustainability Disclosure Imbalances. A Qualitative Case-Study Analysis. World Review of Entrepreneurship Management and Sustainable Development 2019, 15, 42–59. [CrossRef]

- Ismael Barugahare; Benjamin Ombok Advancing Sustainability: A Systematic Review of Supply Chain Management Practices. The International Journal of Business & Management 2024. [CrossRef]

- Maász, C.; Kroll, L.; Lingenfelder, M. Requirements of Environmentally-Aware Consumers on the Implementation and Communication of Sustainability Measures in the Beverage Industry: A Qualitative Kano-Model Approach. Journal of Food Products Marketing 2024, 30, 118–133. [CrossRef]

| Dimension | Priority Areas | Citations |

| Environmental | Carbon footprint reduction, water resource management, waste management | [43,44,45] |

| Social | Labour rights, human rights, community development, consumer awareness | [43,46,47] |

| Economic | Cost management, market competitiveness, supply chain efficiency | [1,43,45] |

| Dimension/Indicators | Cns (X) |

| Economic Dimension | |

| Sales revenue | 0,75 |

| Operational expenditures | 0,78 |

| Employee salaries and benefits | 0,74 |

| Dividends and interest on equity | 0,71 |

| Taxes and government contributions | 0,71 |

| Purchases from local suppliers | 0,71 |

| Infrastructure investments in society | 0,73 |

| Technological innovations (production and distribution) | 0,71 |

| Indirect job creation | 0,70 |

| Environmental Dimension | |

| Recycled materials | 0,78 |

| Recycled and reused water | 0,77 |

| Company’s geographical location | 0,71 |

| Energy from non-renewable and renewable sources | 0,71 |

| Reused and recycled waste | 0,82 |

| Recovered product packaging | 0,74 |

| Environmental complaints | 0,70 |

| Environmental prevention and management costs | 0,74 |

| Environmental supplier policies | 0,71 |

| Environmental impact assessments | 0,79 |

| Social Dimension | |

| Number of employees | 0,70 |

| Legal employee benefits | 0,74 |

| Employee training | 0,75 |

| Employee performance | 0,71 |

| Social impact assessments through participatory processes | 0,71 |

| Public disclosure of environmental and social impacts | 0,72 |

| Local development programmes | 0,72 |

| Operations evaluated for corruption risks | 0,71 |

| Anti-corruption policies and procedures | 0,77 |

| Employees trained in anti-corruption measures | 0,71 |

| Products with certification and labelling | 0,78 |

| Customer satisfaction | 0,75 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).