Submitted:

19 June 2025

Posted:

20 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

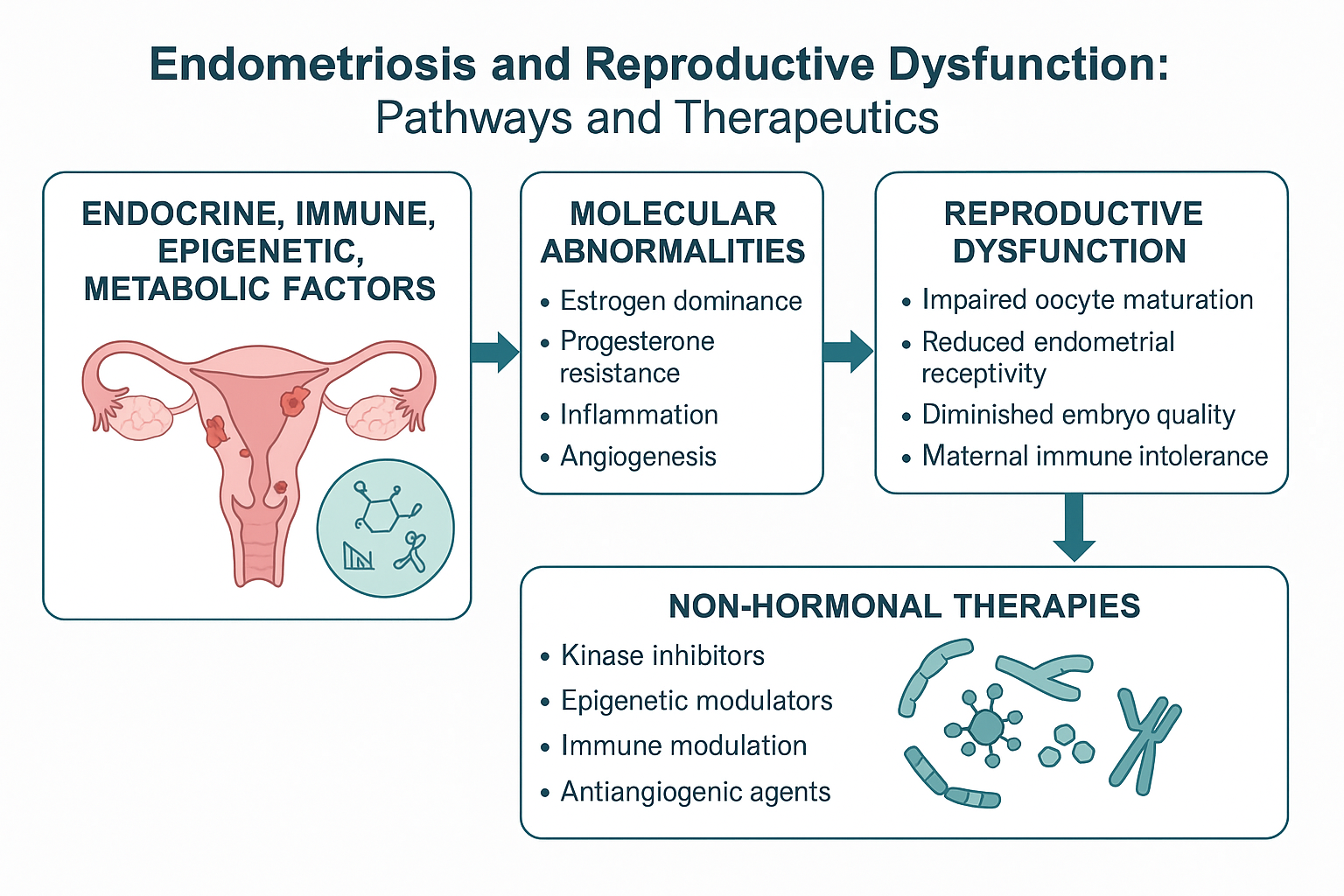

2. Molecular Mechanisms of Endometriosis

2.1. Hormonal Dysregulation

2.2. Epigenetic Reprogramming and Non-Coding RNAs

2.3. Intracellular Signaling Pathways

2.4. Inflammation, Immune Cell Recruitment, and Neuro-Immune Crosstalk

2.5. Oxidative Stress and Peritoneal Toxicity

2.6. Extracellular Matrix Remodeling, EMT, and Fibrogenesis

2.7. Aberrant Vascular Remodeling and Non-Canonical Angiogenic Pathways

3. Molecular Bridges Between Endometriosis and Infertility

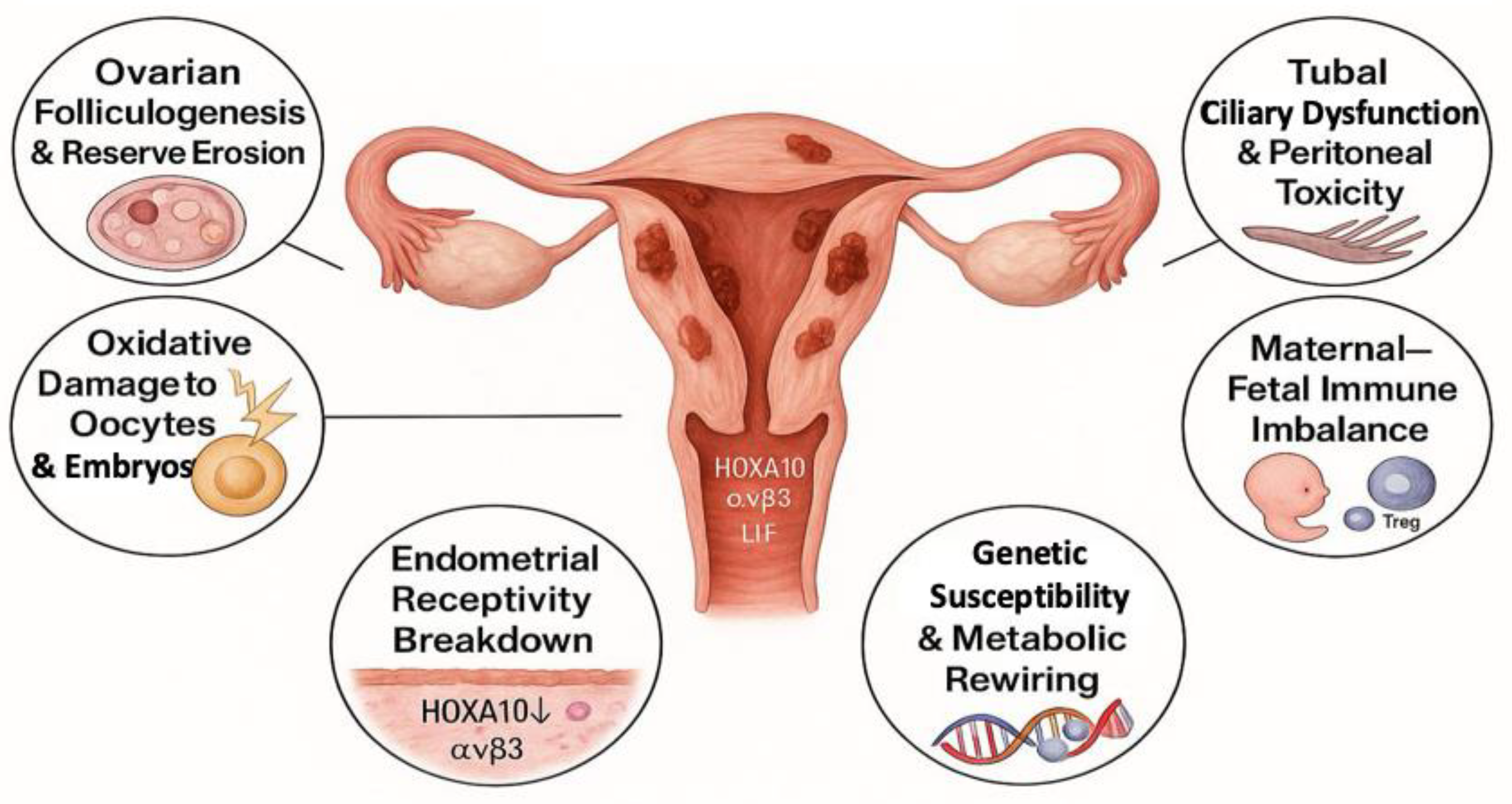

3.1. Ovarian Folliculogenesis and Reserve Erosion

3.2. Oxidative Damage to Oocytes and Early Embryos

3.3. Tubal Ciliary Dysfunction and Peritoneal Toxicity

3.4. Endometrial Receptivity Breakdown

3.5. Maternal–Fetal Immune Imbalance and Implantation Failure

3.6. Genetic Susceptibility and Metabolic Rewiring

4. Emerging Therapeutic Targets in Endometriosis-Associated Infertility

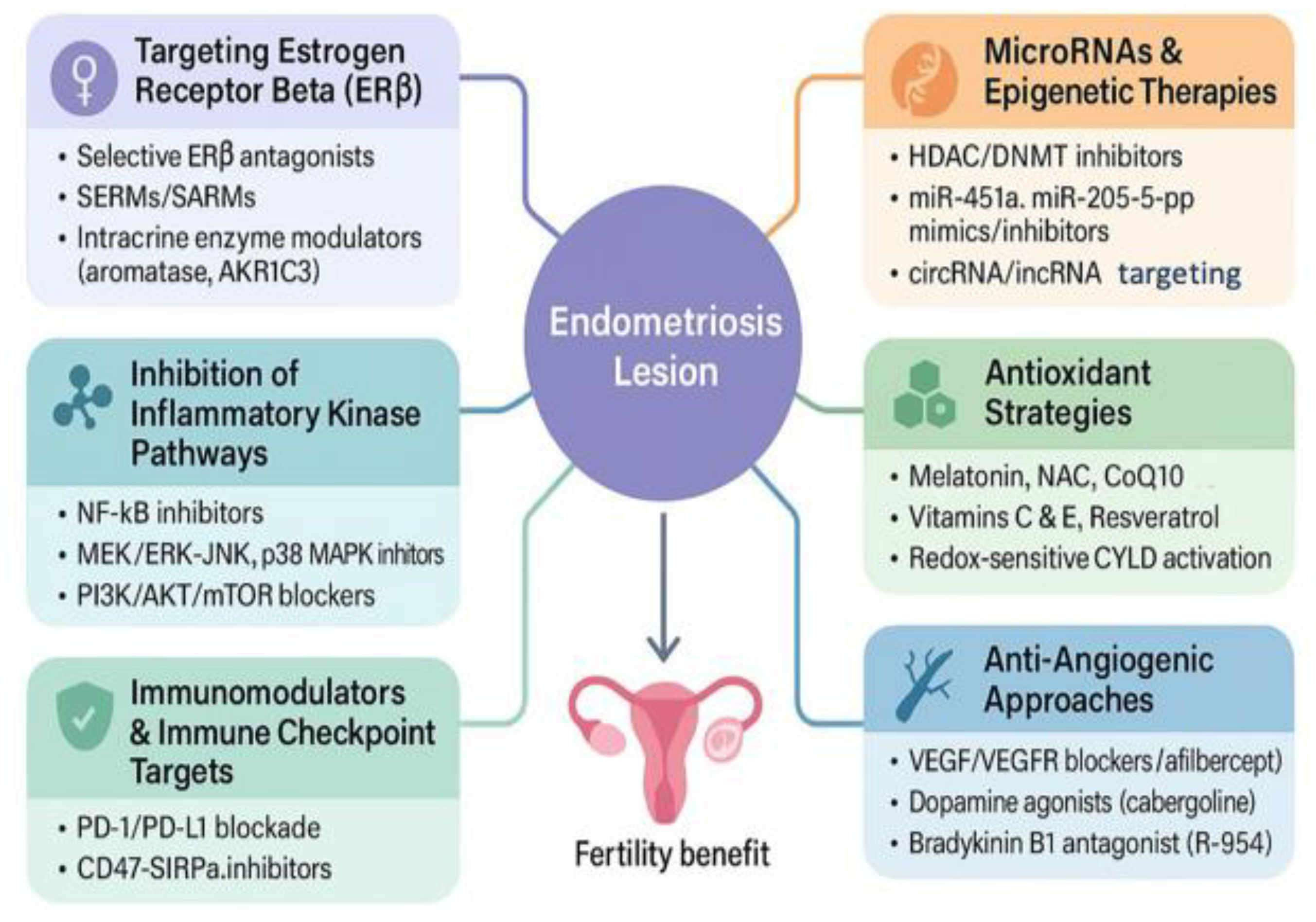

4.1. Targeting Estrogen Receptor Beta (ERβ) Signaling.

4.2. Inhibition of inflammatory Kinase Pathways

4.3. Non-Hormonal Immunomodulation and Immune Checkpoint Targets

4.4. Epigenetic Therapies and Non-Coding RNA Modulators

4.5. Antioxidant-based Strategies and Redox Modulation

4.6. Anti-Angiogenic and Vascular Normalization Therapies

5. From Risk Reduction to Fertility Preservation: Biomarker-Guided Strategies in Endometriosis Care

5.1. Primary Prevention: Risk Stratification and Early Identification

5.2. Secondary Prevention: Halting Disease Progression and Preserving Ovarian Function

5.3. Tertiary Prevention: Preventing Recurrence and Individualizing Long-Term Fertility Planning

6. Conclusions and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 17β-HSD2 | 17β-Hydroxysteroid Dehydrogenase Type 2 |

| 8-OHdG | 8-Hydroxy-2′-Deoxyguanosine |

| ABCA1 | ATP-Binding Cassette Transporter A1 |

| ABCG1 | ATP-Binding Cassette Transporter G1 |

| AKR1C3 | Aldo-Keto Reductase Family 1 Member C3 |

| AKT | Protein Kinase B |

| AMH | Anti-Müllerian Hormone |

| ANGPT2 | Angiopoietin-2 |

| ASK1 | Apoptosis Signal-Regulating Kinase 1 |

| AT1R | Angiotensin II Type 1 Receptor |

| BPA | Bisphenol A |

| C5aR1 | Complement C5a Receptor 1 |

| CD5L | CD5 Molecule-Like |

| CDKN2B-AS1 | Cyclin-Dependent Kinase Inhibitor 2B Antisense RNA 1 |

| CDC42 | Cell Division Cycle 42 |

| ceRNA | Competing Endogenous RNA |

| CECs | Circulating Endometrial Cells |

| circRNA | Circular RNA |

| COL1A1 | Collagen Type I Alpha 1 Chain |

| COX-2 | Cyclo-Oxygenase-2 |

| CTGF | Connective Tissue Growth Factor |

| CTNNB1 | Catenin Beta 1 (β-Catenin) |

| CYLD | Cylindromatosis (Deubiquitinase) |

| CYP19A1 | Cytochrome P450 19A1 |

| DIPC2 | Disco-Interacting Protein 2 Homolog C |

| Dll4 | Delta-Like Ligand 4 |

| DNMT1 | DNA (Cytosine-5) Methyltransferase 1 |

| EDC | Endocrine-Disrupting Chemical |

| ER | Estrogen Receptor (generic) |

| Erα | Estrogen Receptor Alpha |

| ERβ | Estrogen Receptor Beta |

| ERK/ERK1/2 | Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase 1/2 |

| ESC | Endometrial Stromal Cell |

| FOXP3⁺ | Forkhead Box P3-Positive Regulatory T Cell |

| FSHR | Follicle-Stimulating Hormone Receptor |

| GnRH | Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone |

| GREB1 | Growth Regulation by Estrogen in Breast Cancer 1 |

| GPER | G-Protein-Coupled Estrogen Receptor |

| GPR30 | G-Protein-Coupled Receptor 30 |

| GSH | Glutathione (reduced) |

| GSSG | Glutathione Disulfide (oxidized) |

| GWAS | Genome-Wide Association Study |

| HIF-1α | Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1 Alpha |

| HOXA10 | Homeobox A10 |

| ICAM2 | Intercellular Adhesion Molecule 2 |

| IL | Interleukin |

| INSL3 | Insulin-Like Peptide 3 |

| IVF | In Vitro Fertilization |

| JNK | c-Jun N-Terminal Kinase |

| LIF | Leukemia Inhibitory Factor |

| LNG-IUS | Levonorgestrel-Releasing Intrauterine System |

| lncRNA | Long Non-Coding RNA |

| LOX | Lysyl Oxidase |

| LXR | Liver X Receptor |

| MAPK | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase |

| MAPK1 | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase 1 |

| MEK | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Kinase |

| miRNA | MicroRNA |

| mTOR | Mammalian Target of Rapamycin |

| MMP | Matrix Metalloproteinase |

| NAC | N-Acetyl-L-Cysteine |

| NLRP3 | NACHT, LRR and PYD Domains-Containing Protein 3 |

| NGF | Nerve Growth Factor |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor κ-Light-Chain-Enhancer of Activated B Cells |

| NK | Natural Killer (Cell) |

| PAR-2 | Protease-Activated Receptor 2 |

| PCB | Polychlorinated Biphenyl |

| PCNA | Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen |

| PD-1 | Programmed Cell Death Protein 1 |

| PD-L1 | Programmed Death-Ligand 1 |

| PI3K | Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase |

| PPAR | Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor |

| PPAR-α | Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Alpha |

| PR-B | Progesterone Receptor Isoform B |

| PROK1 | Prokineticin-1 |

| PROKR1 | Prokineticin Receptor 1 |

| PrPC | Cellular Prion Protein |

| PWAS | Proteome-Wide Association Study |

| r-hTBP1 | Recombinant Human TNFRSF1A |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| RRP1 | Ribosomal RNA-Processing Protein 1 |

| RSPO3 | R-Spondin 3 |

| RUNX3 | Runt-Related Transcription Factor 3 |

| S100A9 | S100 Calcium-Binding Protein A9 |

| SARM | Selective Androgen Receptor Modulator |

| SARD | Selective Androgen Receptor Degrader |

| SERM | Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulator |

| SF-1 | Steroidogenic Factor 1 |

| SIRPα | Signal-Regulatory Protein Alpha |

| Slit2 | Slit Guidance Ligand 2 |

| SMAD | (S)-Homologues of Mothers Against Decapentaplegic |

| SNAIL | Snail Family Transcriptional Repressor 1 |

| SNP | Single-Nucleotide Polymorphism |

| STAT3 | Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 |

| STRAP | Serine/Threonine Kinase Receptor-Associated Protein |

| TET | Ten-Eleven Translocation Dioxygenase |

| TET2 | Ten-Eleven Translocation Methylcytosine Dioxygenase 2 |

| TGF-β | Transforming Growth Factor Beta |

| TIMPs | Tissue Inhibitors of Metalloproteinases |

| TOP1 | DNA Topoisomerase I |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha |

| Tregs | Regulatory T Cells |

| TWAS | Transcriptome-Wide Association Study |

| uNK | Uterine Natural Killer Cell |

| uPA | Urokinase-Type Plasminogen Activator |

| uPAR | Urokinase-Type Plasminogen Activator Receptor |

| USP1 | Ubiquitin-Specific Peptidase 1 |

| VEGF | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor |

| VEZT | Vezatin Adherens Junctions Transmembrane Protein |

| WDR5 | WD Repeat Domain 5 |

| Wnt | Wingless-Related Integration Site (Wnt) Family |

| WNT4 | Wnt Family Member 4 |

| YWHAZ | 14-3-3 Protein Zeta/Delta |

| ZEB1/2 | Zinc Finger E-Box-Binding Homeobox 1 & 2 |

References

- Giudice, L.C. Endometriosis. New England Journal of Medicine 2010, 362, 2389–2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zondervan, K.T.; Becker, C.M.; Missmer, S.A. Endometriosis. New England Journal of Medicine 2020, 382, 1244–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasar, P.; Ozcan, P.; Terry, K.L. Endometriosis: Epidemiology, Diagnosis and Clinical Management. Curr Obstet Gynecol Rep 2017, 6, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bulun, S.E. Endometriosis. New England Journal of Medicine 2009, 360, 268–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vercellini, P.; Viganò, P.; Somigliana, E.; Fedele, L. Endometriosis: Pathogenesis and Treatment. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2014, 10, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Psilopatis, I.; Burghaus, S.; Au, K.; Hofbeck, L.; Windischbauer, L.; Lotz, L.; Beckmann, M.W. The Hallmarks of Endometriosis. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd 2024, 84, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanda, C.R.; Asmarinah; Hestiantoro, A.; Tulandi, T. Febriyeni Gene Expression of Aromatase, SF-1, and HSD17B2 in Menstrual Blood as Noninvasive Diagnostic Biomarkers for Endometriosis. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology 2024, 301, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulun, S.E.; Fang, Z.; Imir, G.; Gurates, B.; Tamura, M.; Yilmaz, B.; Langoi, D.; Amin, S.; Yang, S.; Deb, S. Aromatase and Endometriosis. Seminars in Reproductive Medicine 2004, 22, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chantalat, E.; Valera, M.-C.; Vaysse, C.; Noirrit, E.; Rusidze, M.; Weyl, A.; Vergriete, K.; Buscail, E.; Lluel, P.; Fontaine, C.; et al. Estrogen Receptors and Endometriosis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rižner, T.L.; Gjorgoska, M. Steroid Sulfatase and Sulfotransferases in the Estrogen and Androgen Action of Gynecological Cancers: Current Status and Perspectives. Essays in Biochemistry 2024, 68, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Costa, K. de A.; Malvezzi, H.; Dobo, C.; Neme, R.M.; Filippi, R.Z.; Aloia, T.P.A.; Prado, E.R.; Meola, J.; Piccinato, C. de A. Site-Specific Regulation of Sulfatase and Aromatase Pathways for Estrogen Production in Endometriosis. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secky, L.; Svoboda, M.; Klameth, L.; Bajna, E.; Hamilton, G.; Zeillinger, R.; Jäger, W.; Thalhammer, T. The Sulfatase Pathway for Estrogen Formation: Targets for the Treatment and Diagnosis of Hormone-Associated Tumors. Journal of Drug Delivery 2013, 2013, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Q.; Li, Y.; Chen, Z.; Luo, Z.; Zhou, T.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, S.; Wang, L. Update on the Pathogenesis of Endometriosis-Related Infertility Based on Contemporary Evidence. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens Brentjens, L.B.P.M.; Delvoux, B.; den Hartog, J.E.; Obukhova, D.; Xanthoulea, S.; Romano, A.; van Golde, R.J.T. Endometrial Metabolism of 17β-Estradiol during the Window of Implantation in Women with Recurrent Implantation Failure. Gynecologic and Obstetric Investigation 2025. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, H.; Kimura, M.; Maruyama, S.; Nagayasu, M.; Imanaka, S. Revisiting Estrogen-Dependent Signaling Pathways in Endometriosis: Potential Targets for Non-Hormonal Therapeutics. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology 2021, 258, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laganà, A.S.; Garzon, S.; Götte, M.; Viganò, P.; Franchi, M.; Ghezzi, F.; Martin, D.C. The Pathogenesis of Endometriosis: Molecular and Cell Biology Insights. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2019, 20, 5615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Zhang, J.; Lu, Y.; Fu, B.; Hu, W. Estrogen Receptor Beta Promotes Endometriosis Progression by Upregulating CD47 Expression in Ectopic Endometrial Stromal Cells. Journal of Reproductive Immunology 2022, 151, 103513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gou, Y.; Li, X.; Li, P.; Zhang, H.; Xu, T.; Wang, H.; Wang, B.; Ma, X.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, Z. Estrogen Receptor β Upregulates CCL2 via NF-κB Signaling in Endometriotic Stromal Cells and Recruits Macrophages to Promote the Pathogenesis of Endometriosis. Hum Reprod 2019, 34, 646–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szukiewicz, D. Insight into the Potential Mechanisms of Endocrine Disruption by Dietary Phytoestrogens in the Context of the Etiopathogenesis of Endometriosis. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 12195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Jo, M.; Lee, E.; Kim, S.E.; Lee, D.-Y.; Choi, D. Inhibition of the NLRP3 Inflammasome by Progesterone Is Attenuated by Abnormal Autophagy Induction in Endometriotic Cyst Stromal Cells: Implications for Endometriosis. Molecular Human Reproduction 2022, 28, gaac007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irandoost, E.; Najibi, S.; Talebbeigi, S.; Nassiri, S. Focus on the Role of NLRP3 Inflammasome in the Pathology of Endometriosis: A Review on Molecular Mechanisms and Possible Medical Applications. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch Pharmacol 2023, 396, 621–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.-G.; Wu, X.-X.; Hua, T.; Xin, X.-Y.; Feng, D.-L.; Chi, S.-Q.; Wang, X.-X.; Wang, H.-B. NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation by Estrogen Promotes the Progression of Human Endometrial Cancer. Onco Targets Ther 2019, 12, 6927–6936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leavy, O. Evading Immunosurveillance in Endometriosis. Nat Rev Immunol 2015, 15, 729–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Gómez, E.; Vázquez-Martínez, E.R.; Reyes-Mayoral, C.; Cruz-Orozco, O.P.; Camacho-Arroyo, I.; Cerbón, M. Regulation of Inflammation Pathways and Inflammasome by Sex Steroid Hormones in Endometriosis. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmen, R.C.M.; Kelley, A.S. Reversal of Fortune: Estrogen Receptor-β in Endometriosis. J Mol Endocrinol 2016, 57, F23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azuma, K.; Inoue, S. Genomic and Non-Genomic Actions of Estrogen: Recent Developments. BioMolecular Concepts 2012, 3, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greygoose, E.; Metharom, P.; Kula, H.; Seckin, T.K.; Seckin, T.A.; Ayhan, A.; Yu, Y. The Estrogen–Immune Interface in Endometriosis. Cells 2025, 14, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.C.; Suzawa, M.; Blind, R.D.; Tobias, S.C.; Bulun, S.E.; Scanlan, T.S.; Ingraham, H.A. Stimulating the GPR30 Estrogen Receptor with a Novel Tamoxifen Analogue Activates SF-1 and Promotes Endometrial Cell Proliferation. Cancer Res 2009, 69, 5415–5423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Xu, T.; Tong, D.; Li, S.; Yu, X.; Liu, B.; Jiang, L.; Liu, K. Research Advances in Endometriosis-Related Signaling Pathways: A Review. Biomed Pharmacother 2023, 164, 114909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Strawn, E.; Basir, Z.; Halverson, G.; Guo, S.-W. Promoter Hypermethylation of Progesterone Receptor Isoform B (PR-B) in Endometriosis. Epigenetics 2006, 1, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colón-Díaz, M.; Báez-Vega, P.; García, M.; Ruiz, A.; Monteiro, J.B.; Fourquet, J.; Bayona, M.; Alvarez-Garriga, C.; Achille, A.; Seto, E.; et al. HDAC1 and HDAC2 Are Differentially Expressed in Endometriosis. Reprod Sci 2012, 19, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szukiewicz, D. Aberrant Epigenetic Regulation of Estrogen and Progesterone Signaling at the Level of Endometrial/Endometriotic Tissue in the Pathomechanism of Endometriosis. Vitam Horm 2023, 122, 193–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Promoter Hypermethylation of Progesterone Receptor Isoform B (PR-B) in Adenomyosis and Its Rectification by a Histone Deacetylase Inhibitor and a Demethylation Agent. Reprod Sci 2010, 17, 995–1005. [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Guo, C.; Li, Y.; Zhou, M.; Wang, H.; Liu, J.; Chen, P. Oestrogen Up-Regulates DNMT1 and Leads to the Hypermethylation of RUNX3 in the Malignant Transformation of Ovarian Endometriosis. Reprod Biomed Online 2022, 44, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, W.; Yao, X.; Ting, G.; Ling, J.; Huimin, L.; Yuan, Q.; Chun, Z.; Ming, Z.; Yuanzhen, Z. BPA Modulates the WDR5/TET2 Complex to Regulate ERβ Expression in Eutopic Endometrium and Drives the Development of Endometriosis. Environmental Pollution 2021, 268, 115748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, N.-Z.; Wang, X.-M.; Jiao, X.-W.; Li, R.; Zeng, C.; Li, S.-N.; Guo, H.-S.; Wang, Z.-Y.; Huang, Z.; He, C.-Q. Cellular Prion Protein Is Involved in Decidualization of Mouse Uterus. Biol Reprod 2018, 99, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.-Y.; Lei, S.-T.; Hou, S.-H.; Weng, L.-C.; Yuan, Q.; Li, M.-Q.; Zhao, D. PrPC Promotes Endometriosis Progression by Reprogramming Cholesterol Metabolism and Estrogen Biosynthesis of Endometrial Stromal Cells through PPARα Pathway. Int J Biol Sci 2022, 18, 1755–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psilopatis, I.; Theocharis, S.; Beckmann, M.W. The Role of Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptors in Endometriosis. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1329406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Gu, P.; Tuo, L.; Wang, L.; Jiang, S.-W. Transgenic Mice Applications in the Study of Endometriosis Pathogenesis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 12, 1376414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducreux, B.; Patrat, C.; Firmin, J.; Ferreux, L.; Chapron, C.; Marcellin, L.; Parpex, G.; Bourdon, M.; Vaiman, D.; Santulli, P.; et al. Systematic Review on the DNA Methylation Role in Endometriosis: Current Evidence and Perspectives. Clin Epigenetics 2025, 17, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Halverson, G.; Basir, Z.; Strawn, E.; Yan, P.; Guo, S.-W. Aberrant Methylation at HOXA10 May Be Responsible for Its Aberrant Expression in the Endometrium of Patients with Endometriosis. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2005, 193, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elias, M.H.; Lazim, N.; Sutaji, Z.; Abu, M.A.; Abdul Karim, A.K.; Ugusman, A.; Syafruddin, S.E.; Mokhtar, M.H.; Ahmad, M.F. HOXA10 DNA Methylation Level in the Endometrium Women with Endometriosis: A Systematic Review. Biology (Basel) 2023, 12, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pîrlog, L.-M.; Pătrășcanu, A.-A.; Ona, M.-D.; Cătană, A.; Rotar, I.C. HOXA10 and HOXA11 in Human Endometrial Benign Disorders: Unraveling Molecular Pathways and Their Impact on Reproduction. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petracco, R.; Grechukhina, O.; Popkhadze, S.; Massasa, E.; Zhou, Y.; Taylor, H.S. MicroRNA 135 Regulates HOXA10 Expression in Endometriosis. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2011, 96, E1925–E1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirabutalebi, S.H.; Karami, N.; Montazeri, F.; Fesahat, F.; Sheikhha, M.H.; Hajimaqsoodi, E.; Karimi Zarchi, M.; Kalantar, S.M. The Relationship between the Expression Levels of miR-135a and HOXA10 Gene in the Eutopic and Ectopic Endometrium. Int J Reprod Biomed 2018, 16, 501–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Ni, T.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Yan, J.; Chen, Z.-J. circFAM120A Participates in Repeated Implantation Failure by Regulating Decidualization via the miR-29/ABHD5 Axis. FASEB J 2021, 35, e21872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, M.; Wan, X.; La, X.; Gong, X.; Cai, X. miR-29c Is Downregulated in the Ectopic Endometrium and Exerts Its Effects on Endometrial Cell Proliferation, Apoptosis and Invasion by Targeting c-Jun. International Journal of Molecular Medicine 2015, 35, 1119–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, T.; Liu, C.; Liu, T.; Xiao, L.; Luo, B.; Tan, J.; Li, X.; Zhou, G.; Duan, C.; Huang, W. miR-194-3p Represses the Progesterone Receptor and Decidualization in Eutopic Endometrium From Women With Endometriosis. Endocrinology 2018, 159, 2554–2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Han, B.; Zhang, Y.; Su, K.; Wang, C.; Hai, P.; Bian, A.; Guo, R. Effect of miR-194-5p Regulating STAT1/mTOR Signaling Pathway on the Biological Characteristics of Ectopic Endometrial Cells from Mice. Am J Transl Res 2020, 12, 6136–6148. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Lin, Y.; Li, S.; Yao, X.; Cheng, M.; Zhu, L.; Liu, H. microRNA-194 Is Increased in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Granulosa Cell and Induce KGN Cells Apoptosis by Direct Targeting Heparin-Binding EGF-like Growth Factor. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2021, 19, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.; Chang, H.; Heo, J.-H.; Yum, S.; Jo, E.; Kim, M.; Lee, S.-R. Expression Profiling of Coding and Noncoding RNAs in the Endometrium of Patients with Endometriosis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 10581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Xin, W.; Lu, Q.; Tang, X.; Wang, F.; Shao, W.; Zhang, Y.; Qiu, J.; Hua, K. Knockdown of lncRNA H19 Suppresses Endometriosis in Vivo. Braz J Med Biol Res 2021, 54, e10117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Xin, W.; Tang, X.; Qiu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Hua, K. LncRNA H19 Overexpression in Endometriosis and Its Utility as a Novel Biomarker for Predicting Recurrence. Reprod Sci 2020, 27, 1687–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, Q.J.; Proestling, K.; Perricos, A.; Kuessel, L.; Husslein, H.; Wenzl, R.; Yotova, I. The Role of Long Non-Coding RNAs in Endometriosis. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 11425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Gu, C.; Ye, M.; Zhang, Z.; Li, L.; Fan, W.; Meng, Y. Integration Analysis of microRNA and mRNA Paired Expression Profiling Identifies Deregulated microRNA-Transcription Factor-Gene Regulatory Networks in Ovarian Endometriosis. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2018, 16, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dana, P.M.; Taghavipour, M.; Mirzaei, H.; Yousefi, B.; Moazzami, B.; Chaichian, S.; Asemi, Z. Circular RNA as a Potential Diagnostic and/or Therapeutic Target for Endometriosis. Biomark Med 2020, 14, 1277–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuzaki, S.; Darcha, C. Co-Operation between the AKT and ERK Signaling Pathways May Support Growth of Deep Endometriosis in a Fibrotic Microenvironment in Vitro. Hum Reprod 2015, 30, 1606–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinar, O.; Seval, Y.; Uz, Y.H.; Cakmak, H.; Ulukus, M.; Kayisli, U.A.; Arici, A. Differential Regulation of Akt Phosphorylation in Endometriosis. Reproductive BioMedicine Online 2009, 19, 864–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, M.; Fu, X.; Meng, X.; Liu, H.; Ma, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, Q.; Chen, J. PI3K/AKT Signaling Pathway Associates with Pyroptosis and Inflammation in Patients with Endometriosis. Journal of Reproductive Immunology 2024, 162, 104213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuzaki, S.; Darcha, C. Involvement of the Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway in the Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Fibrosis in Endometriosis. PLoS One 2013, 8, e76808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, X.; Li, Z.; Han, X.; Wang, W.; Xu, P.; Liu, Y.; Xue, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xu, S.; et al. Interactions between miRNAs and the Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway in Endometriosis. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2024, 171, 116182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driva, T.S.; Schatz, C.; Sobočan, M.; Haybaeck, J. The Role of mTOR and eIF Signaling in Benign Endometrial Diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 3416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaf, L.; Eid, A.A.; Nassif, J. Role of AMPK/mTOR, Mitochondria, and ROS in the Pathogenesis of Endometriosis. Life Sciences 2022, 306, 120805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Liu, Y.; Zhong, Z.; Wei, C.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, X. Peritoneal Immune Microenvironment of Endometriosis: Role and Therapeutic Perspectives. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaton, J.L.; Unno, K.; Caraveo, M.; Lu, Z.; Kim, J.J. Increased AKT or MEK1/2 Activity Influences Progesterone Receptor Levels and Localization in Endometriosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013, 98, E1871–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, J.; Tian, Q.; Li, S.; Zhou, X.; Sun, Q.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Li, M.; Chang, K.; Yi, X. The IL-33-ST2 Axis Plays a Vital Role in Endometriosis via Promoting Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition by Phosphorylating β-Catenin. Cell Commun Signal 2024, 22, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui San, S.; Ching Ngai, S. E-Cadherin Re-Expression: Its Potential in Combating TRAIL Resistance and Reversing Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition. Gene 2024, 909, 148293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capobianco, A.; Rovere-Querini, P. Endometriosis, a Disease of the Macrophage. Front Immunol 2013, 4, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulke, L.; Berbic, M.; Manconi, F.; Tokushige, N.; Markham, R.; Fraser, I.S. Dendritic Cell Populations in the Eutopic and Ectopic Endometrium of Women with Endometriosis. Hum Reprod 2009, 24, 1695–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheerer, C.; Bauer, P.; Chiantera, V.; Sehouli, J.; Kaufmann, A.; Mechsner, S. Characterization of Endometriosis-Associated Immune Cell Infiltrates (EMaICI). Arch Gynecol Obstet 2016, 294, 657–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henlon, Y.; Panir, K.; McIntyre, I.; Hogg, C.; Dhami, P.; Cuff, A.O.; Senior, A.; Moolchandani-Adwani, N.; Courtois, E.T.; Horne, A.W.; et al. Single-Cell Analysis Identifies Distinct Macrophage Phenotypes Associated with Prodisease and Proresolving Functions in the Endometriotic Niche. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2024, 121, e2405474121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwabe, T.; Harada, T.; Tsudo, T.; Nagano, Y.; Yoshida, S.; Tanikawa, M.; Terakawa, N. Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha Promotes Proliferation of Endometriotic Stromal Cells by Inducing Interleukin-8 Gene and Protein Expression. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2000, 85, 824–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oală, I.E.; Mitranovici, M.-I.; Chiorean, D.M.; Irimia, T.; Crișan, A.I.; Melinte, I.M.; Cotruș, T.; Tudorache, V.; Moraru, L.; Moraru, R.; et al. Endometriosis and the Role of Pro-Inflammatory and Anti-Inflammatory Cytokines in Pathophysiology: A Narrative Review of the Literature. Diagnostics (Basel) 2024, 14, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kacem-Berjeb, K.; Braham, M.; Massoud, C.B.; Hannachi, H.; Hamdoun, M.; Chtourou, S.; Debbabi, L.; Bouyahia, M.; Fadhlaoui, A.; Zhioua, F.; et al. Does Endometriosis Impact the Composition of Follicular Fluid in IL6 and AMH? A Case-Control Study. JCM 2023, 12, 1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godin, S.K.; Wagner, J.; Huang, P.; Bree, D. The Role of Peripheral Nerve Signaling in Endometriosis. FASEB Bioadv 2021, 3, 802–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.H.; Edwards, A.K.; Singh, S.S.; Young, S.L.; Lessey, B.A.; Tayade, C. IL-17A Contributes to the Pathogenesis of Endometriosis by Triggering Proinflammatory Cytokines and Angiogenic Growth Factors. J Immunol 2015, 195, 2591–2600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirata, T.; Osuga, Y.; Hamasaki, K.; Yoshino, O.; Ito, M.; Hasegawa, A.; Takemura, Y.; Hirota, Y.; Nose, E.; Morimoto, C.; et al. Interleukin (IL)-17A Stimulates IL-8 Secretion, Cyclooxygensase-2 Expression, and Cell Proliferation of Endometriotic Stromal Cells. Endocrinology 2008, 149, 1260–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-M.; Yang, C.-C.; Hsiao, L.-D.; Yu, C.-Y.; Tseng, H.-C.; Hsu, C.-K.; Situmorang, J.H. Upregulation of COX-2 and PGE2 Induced by TNF-α Mediated Through TNFR1/MitoROS/PKCα/P38 MAPK, JNK1/2/FoxO1 Cascade in Human Cardiac Fibroblasts. J Inflamm Res 2021, 14, 2807–2824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titiz, M.; Landini, L.; Souza Monteiro De Araujo, D.; Marini, M.; Seravalli, V.; Chieca, M.; Pensieri, P.; Montini, M.; De Siena, G.; Pasquini, B.; et al. Schwann Cell C5aR1 Co-Opts Inflammasome NLRP1 to Sustain Pain in a Mouse Model of Endometriosis. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 10142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atiakshin, D.; Patsap, O.; Kostin, A.; Mikhalyova, L.; Buchwalow, I.; Tiemann, M. Mast Cell Tryptase and Carboxypeptidase A3 in the Formation of Ovarian Endometrioid Cysts. IJMS 2023, 24, 6498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.G.; Lim, Y.S.; Hwang, S.; Kim, H.-Y.; Moon, Y.; Song, Y.J.; Na, Y.-J.; Yoon, S. Di-(2-Ethylhexyl) Phthalate Triggers Proliferation, Migration, Stemness, and Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Human Endometrial and Endometriotic Epithelial Cells via the Transforming Growth Factor-β/Smad Signaling Pathway. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 3938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zubrzycka, A.; Migdalska-Sęk, M.; Jędrzejczyk, S.; Brzeziańska-Lasota, E. The Expression of TGF-Β1, SMAD3, ILK and miRNA-21 in the Ectopic and Eutopic Endometrium of Women with Endometriosis. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, V.J.; Brown, J.K.; Saunders, P.T.K.; Duncan, W.C.; Horne, A.W. The Peritoneum Is Both a Source and Target of TGF-β in Women with Endometriosis. PLoS One 2014, 9, e106773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanada, T.; Tsuji, S.; Nakayama, M.; Wakinoue, S.; Kasahara, K.; Kimura, F.; Mori, T.; Ogasawara, K.; Murakami, T. Suppressive Regulatory T Cells and Latent Transforming Growth Factor-β-Expressing Macrophages Are Altered in the Peritoneal Fluid of Patients with Endometriosis. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2018, 16, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostinis, C.; Balduit, A.; Mangogna, A.; Zito, G.; Romano, F.; Ricci, G.; Kishore, U.; Bulla, R. Immunological Basis of the Endometriosis: The Complement System as a Potential Therapeutic Target. Front Immunol 2021, 11, 599117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaninelli, T.H.; Fattori, V.; Heintz, O.K.; Wright, K.R.; Bennallack, P.R.; Sim, D.; Bukhari, H.; Terry, K.L.; Vitonis, A.F.; Missmer, S.A.; et al. Targeting NGF but Not VEGFR1 or BDNF Signaling Reduces Endometriosis-Associated Pain in Mice. Journal of Advanced Research 2024, S2090123224003606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansariniya, H.; Yavari, A.; Javaheri, A.; Zare, F. Oxidative Stress-Related Effects on Various Aspects of Endometriosis. Am J Reprod Immunol 2022, 88, e13593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scutiero, G.; Iannone, P.; Bernardi, G.; Bonaccorsi, G.; Spadaro, S.; Volta, C.A.; Greco, P.; Nappi, L. Oxidative Stress and Endometriosis: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2017, 2017, 7265238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, Q.; Fu, X.; Zhang, L.; Gao, F.; Jin, Z.; Wu, L.; Shu, C.; Zhang, X.; et al. Iron Overload in Endometriosis Peritoneal Fluid Induces Early Embryo Ferroptosis Mediated by HMOX1. Cell Death Discov 2021, 7, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyatt, J.; Fernando, S.M.; Powell, S.G.; Hill, C.J.; Arshad, I.; Probert, C.; Ahmed, S.; Hapangama, D.K. The Role of Iron in the Pathogenesis of Endometriosis: A Systematic Review. Human Reproduction Open 2023, 2023, hoad033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, L.; Xia, Q.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yan, D.; Yang, Z.; Li, J. Iron Overload Inhibits Cell Proliferation and Promotes Autophagy via PARP1/SIRT1 Signaling in Endometriosis and Adenomyosis. Toxicology 2022, 465, 153050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yan, H.; Han, P.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y. Deciphering the Role of Oxidative Stress in Male Infertility: Insights from Reactive Oxygen Species to Antioxidant Therapeutics. FBL 2025, 30, 27046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Cheng, M.; Lian, W.; Leng, Y.; Qin, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, P.; Liu, X.; Peng, T.; Wang, R.; et al. GPX4 Deficiency-Induced Ferroptosis Drives Endometrial Epithelial Fibrosis in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Redox Biology 2025, 83, 103615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Lu, C.; Lv, N.; Kong, W.; Liu, Y. Identification and Analysis of Oxidative Stress-Related Genes in Endometriosis. Front Immunol 2025, 16, 1515490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, B.H.; Chon, S.J.; Choi, Y.S.; Cho, S.; Lee, B.S.; Seo, S.K. Pathophysiology of Endometriosis: Role of High Mobility Group Box-1 and Toll-Like Receptor 4 Developing Inflammation in Endometrium. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0148165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, H.; Liu, B.; Dai, Y.; Li, F.; Bellone, S.; Zhou, Y.; Mamillapalli, R.; Zhao, D.; Venkatachalapathy, M.; Hu, Y.; et al. TET3-Overexpressing Macrophages Promote Endometriosis. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2024, 134, e181839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Limam, I.; Ghali, R.; Abdelkarim, M.; Ouni, A.; Araoud, M.; Abdelkarim, M.; Hedhili, A.; Ben-Aissa Fennira, F. Tunisian Artemisia Campestris L.: A Potential Therapeutic Agent against Myeloma - Phytochemical and Pharmacological Insights. Plant Methods 2024, 20, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campara, K.; Rodrigues, P.; Viero, F.T.; da Silva, B.; Trevisan, G. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Advanced Oxidative Protein Products Levels (AOPP) Levels in Endometriosis: Association with Disease Stage and Clinical Implications. European Journal of Pharmacology 2025, 996, 177434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arendt, W.; Kleszczyński, K.; Gagat, M.; Izdebska, M. Endometriosis and Cytoskeletal Remodeling: The Functional Role of Actin-Binding Proteins. Cells 2025, 14, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bałkowiec, M.; Maksym, R.B.; Włodarski, P.K. The Bimodal Role of Matrix Metalloproteinases and Their Inhibitors in Etiology and Pathogenesis of Endometriosis. Mol Med Rep 2018, 18, 3123–3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Song, Y.; Lei, X.; Huang, H.; Nong, W. MMP-9 as a Clinical Marker for Endometriosis: A Meta-Analysis and Bioinformatics Analysis. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1475531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalili-Tanha, G.; Radisky, E.S.; Radisky, D.C.; Shoari, A. Matrix Metalloproteinase-Driven Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition: Implications in Health and Disease. J Transl Med 2025, 23, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muharam, R.; Bowolaksono, A.; Maidarti, M.; Febri, R.; Mutia, K.; Iffanolida, P.; Ikhsan, M.; Sumapraja, K.; Pratama, G.; Harzif, A.; et al. Elevated MMP-9, Survivin, TGB1 and Downregulated Tissue Inhibitor of TIMP-1, Caspase-3 Activities Are Independent of the Low Levels miR-183 in Endometriosis. IJWH 2024, Volume 16, 1733–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luddi, A.; Marrocco, C.; Governini, L.; Semplici, B.; Pavone, V.; Luisi, S.; Petraglia, F.; Piomboni, P. Expression of Matrix Metalloproteinases and Their Inhibitors in Endometrium: High Levels in Endometriotic Lesions. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 2840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilabert-Estellés, J.; Estellés, A.; Gilabert, J.; Castelló, R.; España, F.; Falcó, C.; Romeu, A.; Chirivella, M.; Zorio, E.; Aznar, J. Expression of Several Components of the Plasminogen Activator and Matrix Metalloproteinase Systems in Endometriosis. Human Reproduction 2003, 18, 1516–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanon, P.; Terraciano, P.B.; Quandt, L.; Palma Kuhl, C.; Pandolfi Passos, E.; Berger, M. Angiotensin II – AT1 Receptor Signalling Regulates the Plasminogen-Plasmin System in Human Stromal Endometrial Cells Increasing Extracellular Matrix Degradation, Cell Migration and Inducing a Proinflammatory Profile. Biochemical Pharmacology 2024, 225, 116280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Limam, I.; Abdelkarim, M.; El Ayeb, M.; Crepin, M.; Marrakchi, N.; Di Benedetto, M. Disintegrin-like Protein Strategy to Inhibit Aggressive Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 12219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wang, J.; Pei, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, Z.; Ye, C.; Song, M.; Hu, Y.; Xue, P.; et al. Endothelial Senescence Induced by PAI-1 Promotes Endometrial Fibrosis. Cell Death Discov. 2025, 11, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazmi, I.; Alharbi, K.S.; Al-Abbasi, F.A.; Almalki, W.H.; G, S.K.; Yasmeen, A.; Khan, A.; Gupta, G. Role of Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition Markers in Different Stages of Endometriosis: Expression of the Snail, Slug, ZEB1, and Twist Genes. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr 2021, 31, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntzeros, K.; Mavrogianni, D.; Blontzos, N.; Soyhan, N.; Kathopoulis, N.; Papamentzelopoulou, M.-S.; Chatzipapas, I.; Protopapas, A. Expression of ZEB1 in Different Forms of Endometriosis: A Pilot Study. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology 2023, 286, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, L.A.; Báez-Vega, P.M.; Ruiz, A.; Peterse, D.P.; Monteiro, J.B.; Bracero, N.; Beauchamp, P.; Fazleabas, A.T.; Flores, I. Dysregulation of Lysyl Oxidase Expression in Lesions and Endometrium of Women With Endometriosis. Reprod. Sci. 2015, 22, 1496–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuzaki, S.; Canis, M.; Murakami, T.; Dechelotte, P.; Bruhat, M.A.; Okamura, K. Immunohistochemical Analysis of the Role of Angiogenic Status in the Vasculature of Peritoneal Endometriosis. Fertility and Sterility 2001, 76, 712–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Don, E.E.; Middelkoop, M.-A.; Hehenkamp, W.J.K.; Mijatovic, V.; Griffioen, A.W.; Huirne, J.A.F. Endometrial Angiogenesis of Abnormal Uterine Bleeding and Infertility in Patients with Uterine Fibroids-A Systematic Review. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 7011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.-W.; Zheng, Y.; Lu, Y.; Liu, X.; Geng, J.-G. Slit2 Overexpression Results in Increased Microvessel Density and Lesion Size in Mice with Induced Endometriosis. Reprod Sci 2013, 20, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Liu, J.; Gao, S.; Qiu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, L.; Qi, G.; Wu, Y.; Lash, G.E.; et al. Role of Slit2 Upregulation in Recurrent Miscarriage through Regulation of Stromal Decidualization. Placenta 2021, 103, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaer, A.; Tuncay, G.; Uysal, O.; Semerci Sevimli, T.; Sahin, N.; Karabulut, U.; Sariboyaci, A.E. The Role of Prokineticins in Recurrent Implantation Failure. Journal of Gynecology Obstetrics and Human Reproduction 2020, 49, 101835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Körbel, C.; Gerstner, M.D.; Menger, M.D.; Laschke, M.W. Notch Signaling Controls Sprouting Angiogenesis of Endometriotic Lesions. Angiogenesis 2018, 21, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, J.P.V.; Eulálio, E.C.; Oliveira, F. da C.; Ximenes, G.F.; Feitosa Filho, H.N.; de Souza, L.B.; Araujo Júnior, E.; Cavalcante, M.B. Endometriosis and Infertility: A Bibliometric Analysis of the 100 Most-Cited Articles from 2000 to 2023. Gynecologic and Obstetric Investigation 2024, 90, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, R.; Ouyang, N.; Dai, K.; Yuan, P.; Zheng, L.; Wang, W. Investigating the Impact of Local Inflammation on Granulosa Cells and Follicular Development in Women with Ovarian Endometriosis. Fertility and Sterility 2019, 112, 882–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.R.V.; Lima, F.E.O.; Souza, A.L.P.; Silva, A.W.B. Interleukin-1β and TNF-α Systems in Ovarian Follicles and Their Roles during Follicular Development, Oocyte Maturation and Ovulation. Zygote 2020, 28, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamczak, R.; Ukleja-Sokołowska, N.; Lis, K.; Dubiel, M. Function of Follicular Cytokines: Roles Played during Maturation, Development and Implantation of Embryo. Medicina (Kaunas) 2021, 57, 1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, A.M.; Somigliana, E.; Vercellini, P.; Pagliardini, L.; Candiani, M.; Vigano, P. Endometriosis as a Detrimental Condition for Granulosa Cell Steroidogenesis and Development: From Molecular Alterations to Clinical Impact. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 2016, 155, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, M.-T.; Cheng, W.; Zhu, R.; Wu, H.-H.; Ding, J.; Zhao, N.-N.; Li, H.; Wang, F.-X. The Cytokine Profiles in Follicular Fluid and Reproductive Outcomes in Women with Endometriosis. Am J Reprod Immunol 2023, 89, e13633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitagliano, A.; Saccardi, C.; Noventa, M.; Di Spiezio Sardo, A.; Saccone, G.; Cicinelli, E.; Pizzi, S.; Andrisani, A.; Litta, P.S. Effects of Chronic Endometritis Therapy on in Vitro Fertilization Outcome in Women with Repeated Implantation Failure: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Fertility and Sterility 2018, 110, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peoc’h, K.; Puy, V.; Fournier, T. Haem Oxygenases Play a Pivotal Role in Placental Physiology and Pathology. Human Reproduction Update 2020, 26, 634–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didziokaite, G.; Biliute, G.; Gudaite, J.; Kvedariene, V. Oxidative Stress as a Potential Underlying Cause of Minimal and Mild Endometriosis-Related Infertility. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 3809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Wang, Z.; Lv, L.; Liu, C.; Wang, L.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Shi, B.; Li, Q.; Hao, G. Molecular Regulation of DNA Damage and Repair in Female Infertility: A Systematic Review. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2024, 22, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Máté, G.; Bernstein, L.R.; Török, A.L. Endometriosis Is a Cause of Infertility. Does Reactive Oxygen Damage to Gametes and Embryos Play a Key Role in the Pathogenesis of Infertility Caused by Endometriosis? Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2018, 9, 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhou, Y.; Hu, C.; Wang, Y.; Yan, Z.; Li, Z.; Wu, R. Mitochondria and Oxidative Stress in Ovarian Endometriosis. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2019, 136, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, H.; Imanaka, S.; Nakamura, H.; Tsuji, A. Understanding the Role of Epigenomic, Genomic and Genetic Alterations in the Development of Endometriosis (Review). Molecular Medicine Reports 2014, 9, 1483–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajani, S.; Chattopadhyay, R.; Goswami, S.K.; Ghosh, S.; Sharma, S.; Chakravarty, B. Assessment of Oocyte Quality in Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome and Endometriosis by Spindle Imaging and Reactive Oxygen Species Levels in Follicular Fluid and Its Relationship with IVF-ET Outcome. Journal of Human Reproductive Sciences 2012, 5, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes Godinho, C.; Soares, S.R.; Nunes, S.G.; Martínez, J.M.M.; Santos-Ribeiro, S. Natural Proliferative Phase Frozen Embryo Transfer—a New Approach Which May Facilitate Scheduling without Hindering Pregnancy Outcomes. Human Reproduction 2024, 39, 1089–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simopoulou, M.; Rapani, A.; Grigoriadis, S.; Pantou, A.; Tsioulou, P.; Maziotis, E.; Tzanakaki, D.; Triantafyllidou, O.; Kalampokas, T.; Siristatidis, C.; et al. Getting to Know Endometriosis-Related Infertility Better: A Review on How Endometriosis Affects Oocyte Quality and Embryo Development. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallvé-Juanico, J.; Houshdaran, S.; Giudice, L.C. The Endometrial Immune Environment of Women with Endometriosis. Human Reproduction Update 2019, 25, 565–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGlade, E.A.; Miyamoto, A.; Winuthayanon, W. Progesterone and Inflammatory Response in the Oviduct during Physiological and Pathological Conditions. Cells 2022, 11, 1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Xu, H.; Liu, M.; Tan, Y.; Huang, S.; Yin, X.; Luo, X.; Chung, H.Y.; Gao, M.; Li, Y.; et al. The Ignored Structure in Female Fertility: Cilia in the Fallopian Tubes. Reproductive BioMedicine Online 2025, 50, 104346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nutu, M. The Role of Progesterone in the Regulation of Ciliary Activity in the Fallopian Tube. 2009; ISBN 978-91-628-7744-6. [Google Scholar]

- Artimovič, P.; Badovská, Z.; Toporcerová, S.; Špaková, I.; Smolko, L.; Sabolová, G.; Kriváková, E.; Rabajdová, M. Oxidative Stress and the Nrf2/PPARγ Axis in the Endometrium: Insights into Female Fertility. Cells 2024, 13, 1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, E.; Wang, X.; Chen, L. Regulated Cell Death in Endometriosis. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustakli, E.; Stavros, S.; Katopodis, P.; Skentou, C.; Potiris, A.; Panagopoulos, P.; Domali, E.; Arkoulis, I.; Karampitsakos, T.; Sarafi, E.; et al. Oxidative Stress and the NLRP3 Inflammasome: Focus on Female Fertility and Reproductive Health. Cells 2025, 14, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Li, B.; Matsuo, M.; Dewar, A.; Mustafaraj, A.; Dey, S.K.; Yuan, J.; Sun, X. Foxa2-Dependent Uterine Glandular Cell Differentiation Is Essential for Successful Implantation. Nat Commun 2025, 16, 2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Huang, X.; Mor, G.; Liao, A. Epigenetic Modifications Working in the Decidualization and Endometrial Receptivity. Cell Mol Life Sci 2019, 77, 2091–2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamczyk, M.; Wender-Ozegowska, E.; Kedzia, M. Epigenetic Factors in Eutopic Endometrium in Women with Endometriosis and Infertility. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 3804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daftary, G.S.; Troy, P.J.; Bagot, C.N.; Young, S.L.; Taylor, H.S. Direct Regulation of Β3-Integrin Subunit Gene Expression by HOXA10 in Endometrial Cells. Molecular Endocrinology 2002, 16, 571–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Taylor, H.S. The Role of Hox Genes in Female Reproductive Tract Development, Adult Function, and Fertility. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2016, 6, a023002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, H.S.; Hantak, A.M.; Stubbs, L.J.; Taylor, R.N.; Bagchi, I.C.; Bagchi, M.K. Roles of Progesterone Receptor A and B Isoforms during Human Endometrial Decidualization. Mol Endocrinol 2015, 29, 882–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Franken, A.; Bielfeld, A.P.; Fehm, T.; Niederacher, D.; Cheng, Z.; Neubauer, H.; Stamm, N. Progesterone-Induced Progesterone Receptor Membrane Component 1 Rise-to-Decline Changes Are Essential for Decidualization. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2024, 22, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabi, F.; Grenier, K.; Parent, S.; Adam, P.; Tardif, L.; Leblanc, V.; Asselin, E. Regulation of the PI3K/Akt Pathway during Decidualization of Endometrial Stromal Cells. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0177387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, D.N.; Hwang, Y.J.; Kim, K.C.; Li, R.; Marquardt, R.M.; Chen, C.; Young, S.L.; Lessey, B.A.; Kim, T.H.; Cheon, Y.-P.; et al. GRB2 Regulation of Essential Signaling Pathways in the Endometrium Is Critical for Implantation and Decidualization. Nat Commun 2025, 16, 2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhou, J.; Fang, M.; Yu, B. Pregnancy Immune Tolerance at the Maternal-Fetal Interface. Int Rev Immunol 2020, 39, 247–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucher, A.; Brichant, G.; Gridelet, V.; Nisolle, M.; Ravet, S.; Timmermans, M.; Henry, L. Implantation Failure in Endometriosis Patients: Etiopathogenesis. J Clin Med 2022, 11, 5366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.; Li, Y.; Meng, Y.-Z.; Xu, P.; Yang, Y.-G.; Dong, S.; He, J.; Hu, Z. Uterine Natural Killer Cells: A Rising Star in Human Pregnancy Regulation. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 918550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, N.; Chi, H.; Qiao, J. Role of Regulatory T Cells in Regulating Fetal-Maternal Immune Tolerance in Healthy Pregnancies and Reproductive Diseases. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Si, P.; Meng, T.; Zhao, X.; Zhu, C.; Zhang, D.; Meng, S.; Li, N.; Liu, R.; Ni, T.; et al. CCR8+ Decidual Regulatory T Cells Maintain Maternal-Fetal Immune Tolerance during Early Pregnancy. Sci Immunol 2025, 10, eado2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisnett, D.J.; Zutautas, K.B.; Miller, J.E.; Lingegowda, H.; Ahn, S.H.; McCallion, A.; Bougie, O.; Lessey, B.A.; Tayade, C. The Dysregulated IL-23/TH17 Axis in Endometriosis Pathophysiology. The Journal of Immunology 2024, 212, 1428–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berdiaki, A.; Vergadi, E.; Makrygiannakis, F.; Vrekoussis, T.; Makrigiannakis, A. Title: Repeated Implantation Failure Is Associated with Increased Th17/Treg Cell Ratio, during the Secretory Phase of the Human Endometrium. Journal of Reproductive Immunology 2024, 161, 104170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vassilopoulou, L.; Matalliotakis, M.; Zervou, M.I.; Matalliotaki, C.; Krithinakis, K.; Matalliotakis, I.; Spandidos, D.A.; Goulielmos, G.N. Defining the Genetic Profile of Endometriosis (Review). Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine 2019, 17, 3267–3281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagliardini, L.; Gentilini, D.; Sanchez, A.M.; Candiani, M.; Viganò, P.; Di Blasio, A.M. Replication and Meta-Analysis of Previous Genome-Wide Association Studies Confirm Vezatin as the Locus with the Strongest Evidence for Association with Endometriosis. Human Reproduction 2015, 30, 987–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalami, I.; Abo, C.; Borghese, B.; Chapron, C.; Vaiman, D. Genomics of Endometriosis: From Genome Wide Association Studies to Exome Sequencing. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 7297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheu, J.J.-C.; Lin, W.-Y.; Liu, T.-Y.; Chang, C.Y.-Y.; Cheng, J.; Li, Y.-H.; Chen, C.-M.; Tseng, C.-C.; Ding, W.Y.; Chung, C.; et al. Ethnic-Specific Genetic Susceptibility Loci for Endometriosis in Taiwanese-Han Population: A Genome-Wide Association Study. J Hum Genet 2024, 69, 573–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasvandik, S.; Samuel, K.; Peters, M.; Eimre, M.; Peet, N.; Roost, A.M.; Padrik, L.; Paju, K.; Peil, L.; Salumets, A. Deep Quantitative Proteomics Reveals Extensive Metabolic Reprogramming and Cancer-Like Changes of Ectopic Endometriotic Stromal Cells. J. Proteome Res. 2016, 15, 572–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, V.J.; Brown, J.K.; Maybin, J.; Saunders, P.T.K.; Duncan, W.C.; Horne, A.W. Transforming Growth Factor-β Induced Warburg-Like Metabolic Reprogramming May Underpin the Development of Peritoneal Endometriosis. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2014, 99, 3450–3459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Xu, J.; Li, K.; Wang, J.; Dai, Y.; Chen, Y.; Chai, R.; Xu, C.; Kang, Y. Chronic Stress Blocks the Endometriosis Immune Response by Metabolic Reprogramming. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 25, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karaer, A.; Tuncay, G.; Mumcu, A.; Dogan, B. Metabolomics Analysis of Follicular Fluid in Women with Ovarian Endometriosis Undergoing in Vitro Fertilization. Systems Biology in Reproductive Medicine 2019, 65, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.; Kim, H.-R.; Lim, E.J.; Park, M.; Yoon, J.A.; Kim, Y.S.; Kim, E.-K.; Shin, J.-E.; Kim, J.H.; Kwon, H.; et al. Integrative Analyses of Uterine Transcriptome and MicroRNAome Reveal Compromised LIF-STAT3 Signaling and Progesterone Response in the Endometrium of Patients with Recurrent/Repeated Implantation Failure (RIF). PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0157696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadłocha, M.; Toczek, J.; Major, K.; Staniczek, J.; Stojko, R. Endometriosis: Molecular Pathophysiology and Recent Treatment Strategies—Comprehensive Literature Review. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2024, 17, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemenza, S.; Vannuccini, S.; Ruotolo, A.; Capezzuoli, T.; Petraglia, F. Advances in Targeting Estrogen Synthesis and Receptors in Patients with Endometriosis. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2022, 31, 1227–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, H.A.; Bruner-Tran, K.L.; Zhang, X.; Osteen, K.G.; Lyttle, C.R. A Selective Estrogen Receptor-β Agonist Causes Lesion Regression in an Experimentally Induced Model of Endometriosis. Human Reproduction 2005, 20, 936–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, D.A.; Simitsidellis, I.; Collins, F.; Saunders, P.T.K. Androgens, Oestrogens and Endometrium: A Fine Balance between Perfection and Pathology. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Wang, S.; Xia, X.; Zhang, T.; Wang, X.; Zeng, F.; Ma, J.; Fang, X. Novel Diagnostic Biomarker BST2 Identified by Integrated Transcriptomics Promotes the Development of Endometriosis via the TNF-α/NF-κB Signaling Pathway. Biochemical Genetics 2025, 63, 354–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Mei, J.; Zhang, B.; Jiang, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, A.; Li, J.; Chen, S.; He, Y.; Fang, Y.; et al. Association Between Circulating Cytokines and Endometriosis: A Mendelian Randomization Study. J Cell Mol Med 2025, 29, e70532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bora, G.; Yaba, A. The Role of Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Signaling Pathway in Endometriosis. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2021, 47, 1610–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Gao, M.; Yao, Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, X. Focusing on the Role of Protein Kinase mTOR in Endometrial Physiology and Pathology: Insights for Therapeutic Interventions. Molecular Biology Reports 2024, 51, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Li, Y.M.; Li, R.Y.; Yang, Y.E.; Wei, M.; Ha, C. U0126 and BAY11-7082 Inhibit the Progression of Endometriosis in a Rat Model by Suppressing the MEK/ERK/NF-κB Pathway. Womens Health Rep (New Rochelle) 2023, 4, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, A.; Tanaka, Y.; Amano, T.; Takebayashi, A.; Takahashi, A.; Hanada, T.; Tsuji, S.; Murakami, T. mTOR Inhibitors as Potential Therapeutics for Endometriosis: A Narrative Review. Mol Hum Reprod 2024, 30, gaae041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Tan, Y. The Potential of Cylindromatosis (CYLD) as a Therapeutic Target in Oxidative Stress-Associated Pathologies: A Comprehensive Evaluation. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 8368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, K. Immunotoxicological Disruption of Pregnancy as a New Research Area in Immunotoxicology. J Immunotoxicol 2025, 22, 2475772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Xu, Q.; Yu, S.; Zhang, T. Perturbations of the Endometrial Immune Microenvironment in Endometriosis and Adenomyosis: Their Impact on Reproduction and Pregnancy. Seminars in Immunopathology 2025, 47, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yan, S.; Li, Q.; Huang, Y.; Ji, M.; Jiao, X.; Yuan, M.; Wang, G. Macrophage-Associated Immune Checkpoint CD47 Blocking Ameliorates Endometriosis. Molecular Human Reproduction 2022, 28, gaac010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keleş, C.D.; Vural, B.; Filiz, S.; Vural, F.; Gacar, G.; Eraldemir, F.C.; Kurnaz, S. THE EFFECTS OF ETANERCEPT AND CABERGOLINE ON ENDOMETRIOTIC IMPLANTS, UTERUS AND OVARIES IN RAT ENDOMETRIOSIS MODEL. J Reprod Immunol 2021, 146, 103340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Song, H.; Shi, G. Anti-TNF-α Treatment for Pelvic Pain Associated with Endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013, 2013, CD008088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Hooghe, T.M.; Nugent, N.P.; Cuneo, S.; Chai, D.C.; Deer, F.; Debrock, S.; Kyama, C.M.; Mihalyi, A.; Mwenda, J.M. Recombinant Human TNFRSF1A (r-hTBP1) Inhibits the Development of Endometriosis in Baboons: A Prospective, Randomized, Placebo- and Drug-Controlled Study. Biol Reprod 2006, 74, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.-H.; Hsiao, S.-M.; Matsuki, S.; Hanada, R.; Chen, C.-A.; Nishimoto-Kakiuchi, A.; Sekiya, M.; Nakai, K.; Matsushima, J.; Sawada, M. Safety and Pharmacology of AMY109, a Long-Acting Anti-Interleukin-8 Antibody, for Endometriosis: A Double-Blind, Randomized Phase 1 Trial. F&S Reports, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acién, P.; Quereda, F.; Campos, A.; Gomez-Torres, M.-J.; Velasco, I.; Gutierrez, M. Use of Intraperitoneal Interferon α-2b Therapy after Conservative Surgery for Endometriosis and Postoperative Medical Treatment with Depot Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Analog: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Fertility and Sterility 2002, 78, 705–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Z.; Yan, Q.; Zhang, M.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, J.; Jiang, Y.; Zhen, X.; Xu, M.; Yue, Q.; Zhou, J.; et al. FHL1 Mediates HOXA10 Deacetylation via SIRT2 to Enhance Blastocyst-Epithelial Adhesion. Cell Death Discov 2022, 8, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zubrzycka, A.; Zubrzycki, M.; Perdas, E.; Zubrzycka, M. Genetic, Epigenetic, and Steroidogenic Modulation Mechanisms in Endometriosis. J Clin Med 2020, 9, 1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Psilopatis, I.; Vrettou, K.; Fleckenstein, F.N.; Theocharis, S. The Impact of Histone Modifications in Endometriosis Highlights New Therapeutic Opportunities. Cells 2023, 12, 1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Yang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, R.; Wang, X. Epigenetic Disorder May Cause Downregulation of HOXA10 in the Eutopic Endometrium of Fertile Women with Endometriosis. Reprod Sci 2013, 20, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrakanth, A.; Firdous, S.; Vasantharekha, R.; Santosh, W.; Seetharaman, B. Exploring the Effects of Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals and miRNA Expression in the Pathogenesis of Endometriosis by Unveiling the Pathways: A Systematic Review. Reproductive Sciences 2024, 31, 932–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhou, Y.; Taylor, H.S. miR-451a Inhibition Reduces Established Endometriosis Lesions in Mice. Reprod Sci 2019, 26, 1506–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Zhang, L.; Liu, H.; Xie, M.; Gao, J.; Zhou, X.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, S.; Yang, J. Circ_0007331 Knock-down Suppresses the Progression of Endometriosis via miR-200c-3p/HiF-1α Axis. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine 2020, 24, 12656–12666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Lu, P.; Mi, X.; Miao, J. Exosomal miR-214 from Endometrial Stromal Cells Inhibits Endometriosis Fibrosis. Molecular Human Reproduction 2018, 24, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.-F.; Liu, M.-J.; Wang, W.; Wu, S.; Huang, Y.-X.; Chen, G.-B.; Liu, L.-M.; Peng, D.-X.; Wang, X.-F.; Cai, X.-Z.; et al. miR-205-5p Inhibits Human Endometriosis Progression by Targeting ANGPT2 in Endometrial Stromal Cells. Stem Cell Res Ther 2019, 10, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budani, M.C.; Tiboni, G.M. Effects of Supplementation with Natural Antioxidants on Oocytes and Preimplantation Embryos. Antioxidants (Basel) 2020, 9, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jara-Palacios, M.J.; Gonçalves, S.; Heredia, F.J.; Hernanz, D.; Romano, A. Extraction of Antioxidants from Winemaking Byproducts: Effect of the Solvent on Phenolic Composition, Antioxidant and Anti-Cholinesterase Activities, and Electrochemical Behaviour. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, M.; Rajabpoor Nikoo, N.; Badehnoosh, B.; Shafabakhsh, R.; Asemi, R.; Reiter, R.J.; Asemi, Z. Therapeutic Effects of Melatonin on Endometriosis, Targeting Molecular Pathways: Current Knowledge and Future Perspective. Pathology - Research and Practice 2023, 243, 154368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Hung, S.-W.; Zhang, R.; Man, G.C.-W.; Zhang, T.; Chung, J.P.-W.; Fang, L.; Wang, C.-C. Melatonin in Endometriosis: Mechanistic Understanding and Clinical Insight. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Ham, J.; Yang, C.; Park, W.; Park, H.; An, G.; Song, J.; Hong, T.; Park, S.J.; Kim, H.S.; et al. Melatonin Inhibits Endometriosis Development by Disrupting Mitochondrial Function and Regulating tiRNAs. Journal of Pineal Research 2023, 74, e12842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasi, E.; Scaramuzzino, S.; Viscardi, M.F.; Viggiani, V.; Piccioni, M.G.; Cacciamani, L.; Merlino, L.; Angeloni, A.; Muzii, L.; Porpora, M.G. Efficacy of N-Acetylcysteine on Endometriosis-Related Pain, Size Reduction of Ovarian Endometriomas, and Fertility Outcomes. IJERPH 2023, 20, 4686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limam, I.; Ben Aissa-Fennira, F.; Essid, R.; Chahbi, A.; Kefi, S.; Mkadmini, K.; Elkahoui, S.; Abdelkarim, M. Hydromethanolic Root and Aerial Part Extracts from Echium Arenarium Guss Suppress Proliferation and Induce Apoptosis of Multiple Myeloma Cells through Mitochondrial Pathway. Environ Toxicol 2021, 36, 874–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Limam, I.; Abdelkarim, M.; Essid, R.; Chahbi, A.; Fathallah, M.; Elkahoui, S.; Ben Aissa-Fennira, F. Olea Europaea L. Cv. Chetoui Leaf and Stem Hydromethanolic Extracts Suppress Proliferation and Promote Apoptosis via Caspase Signaling on Human Multiple Myeloma Cells. European Journal of Integrative Medicine 2020, 37, 101145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gołąbek-Grenda, A.; Kaczmarek, M.; Juzwa, W.; Olejnik, A. Natural Resveratrol Analogs Differentially Target Endometriotic Cells into Apoptosis Pathways. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 11468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podgrajsek, R.; Ban Frangez, H.; Stimpfel, M. Molecular Mechanism of Resveratrol and Its Therapeutic Potential on Female Infertility. IJMS 2024, 25, 3613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gołąbek-Grenda, A.; Juzwa, W.; Kaczmarek, M.; Olejnik, A. Resveratrol and Its Natural Analogs Mitigate Immune Dysregulation and Oxidative Imbalance in the Endometriosis Niche Simulated in a Co-Culture System of Endometriotic Cells and Macrophages. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Chen, C.; Zhong, Y. A Cohort Study on IVF Outcomes in Infertile Endometriosis Patients: The Effects of Rapamycin Treatment. Reprod Biomed Online 2024, 48, 103319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Wang, J.; Ding, X.; Zhang, Q.; Duan, P. Emerging Strategies for the Treatment of Endometriosis. Biomedical Technology 2024, 7, 46–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanamiri, K.; Mahdian, S.; Moini, A.; Shahhoseini, M. Non-Hormonal Therapy for Endometriosis Based on Angiogenesis, Oxidative Stress and Inflammation. Int J Fertil Steril 2024, 18, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ates, C.; Dilbaz, B.; Ergani, S.Y.; Atabay, F.; Ates, C.; Dilbaz, B.; Ergani, S.Y.; Atabay, F. The Effect of Antiangiogenic Agent Aflibercept on Surgically Induced Endometriosis in a Rat Model. Cirugía y cirujanos 2024, 92, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- França, P.R. de C.; Paiva, J.P.B. de; Carvalho, R.R. de; Figueiredo, C.P.; Sirois, P.; Fernandes, P.D. R-954, a Bradykinin B1 Receptor Antagonist, as a Potential Therapy in a Preclinical Endometriosis Model. Peptides 2024, 181, 171294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahgholi, N.; Noormohammadi, Z.; Moieni, A.; Karimipoor, M. Cabergoline’s Promise in Endometriosis: Restoring Molecular Balance to Improve Reproductive Potential. Gynecologic and Obstetric Investigation 2025. [CrossRef]

- Pellicer, A.; Taylor, H.S.; Alberich-Bayarri, A.; Liu, Y.; Gamborg, M.; Barletta, K.E.; Pinton, P.; Heiser, P.W.; Bagger, Y.Z. Quinagolide Vaginal Ring for Reduction of Endometriotic Lesions: Results from the QLARITY Trial. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology 2025, 310, 113946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estole-Casanova, L.A. A Comprehensive Review of the Efficacy and Safety of Dopamine Agonists for Women with Endometriosis-Associated Infertility from Inception to July 31, 2022. Acta Med Philipp 2024, 58, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dymanowska-Dyjak, I.; Frankowska, K.; Abramiuk, M.; Polak, G. Oxidative Imbalance in Endometriosis-Related Infertility—The Therapeutic Role of Antioxidants. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 6298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneghetti, J.K.; Pedrotti, M.T.; Coimbra, I.M.; da Cunha-Filho, J.S.L. Effect of Dietary Interventions on Endometriosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Reprod Sci 2024, 31, 3613–3623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acharya, B.; Behera, A.; Behera, S.; Moharana, S. Recent Advances in Nanotechnology-Based Drug Delivery Systems for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Reproductive Disorders. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2024, 7, 1336–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taghavipour, M.; Sadoughi, F.; Mirzaei, H.; Yousefi, B.; Moazzami, B.; Chaichian, S.; Mansournia, M.A.; Asemi, Z. Apoptotic Functions of microRNAs in Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Endometriosis. Cell Biosci 2020, 10, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akkaya-Ulum, Y.Z.; Sen, B.; Akbaba, T.H.; Balci-Peynircioglu, B. InflammamiRs in Focus: Delivery Strategies and Therapeutic Approaches. The FASEB Journal 2024, 38, e23528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.; Maghsoudloo, M.; Kaboli, P.J.; Babaeizad, A.; Cui, Y.; Fu, J.; Wang, Q.; Imani, S. Decoding the Promise and Challenges of miRNA-Based Cancer Therapies: An Essential Update on miR-21, miR-34, and miR-155. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2024, 21, 2781–2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monnaka, V.U.; Hernandes, C.; Heller, D.; Podgaec, S. Overview of miRNAs for the Non-Invasive Diagnosis of Endometriosis: Evidence, Challenges and Strategies. A Systematic Review. Einstein (São Paulo) 2021, 19, eRW5704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nshimiyimana, P.; Major, I.; Colbert, D.M.; Buckley, C. Progress in the Biomedical Application of Biopolymers: An Overview of the Status Quo and Outlook in Managing Intrauterine Adhesions. Macromol 2025, 5, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, K.; Munro, D.; Clarke, J. Endometriosis Is Undervalued: A Call to Action. Front. Glob. Womens Health 2022, 3, 902371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuspa, R. Economic Burden of Endometriosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. a-jhr 2024, 3, 304–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, P.T.K.; Horne, A.W. Endometriosis: Etiology, Pathobiology, and Therapeutic Prospects. Cell 2021, 184, 2807–2824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brulport, A.; Bourdon, M.; Vaiman, D.; Drouet, C.; Pocate-Cheriet, K.; Bouzid, K.; Marcellin, L.; Santulli, P.; Abo, C.; Jeljeli, M.; et al. An Integrated Multi-Tissue Approach for Endometriosis Candidate Biomarkers: A Systematic Review. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2024, 22, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schäfer, S.D. Prevention of Endometriosis: Is It Possible? In Endometriosis and Adenomyosis: Global Perspectives Across the Lifespan; Oral, E., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2022; pp. 353–360. ISBN 978-3-030-97236-3. [Google Scholar]

- As-Sanie, S.; Mackenzie, S.C.; Morrison, L.; Schrepf, A.; Zondervan, K.T.; Horne, A.W.; Missmer, S.A. Endometriosis: A Review. JAMA 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smolarz, B.; Szyłło, K.; Romanowicz, H. Endometriosis: Epidemiology, Classification, Pathogenesis, Treatment and Genetics (Review of Literature). Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 10554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Encalada Soto, D.; Rassier, S.; Green, I.C.; Burnett, T.; Khan, Z.; Cope, A. Endometriosis Biomarkers of the Disease: An Update. Current Opinion in Obstetrics & Gynecology 2022, 34, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, A.; Moar, K.; K. Arora, T.; Maurya, P.K. Biomarkers of Endometriosis. Clinica Chimica Acta 2023, 549, 117563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, J.V.; Perini, J.A.; Machado, D.E.; Pinto, R.; Medeiros, R. Systematic Review of Genome-Wide Association Studies on Susceptibility to Endometriosis. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology 2020, 255, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, P.T.K. Insights from Genomic Studies on the Role of Sex Steroids in the Aetiology of Endometriosis. Reproduction and Fertility 2022, 3, R51–R65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; Guare, L.; Humphrey, L.A.; Rush, M.; Pollie, M.; Jaworski, J.; Akerele, A.; Luo, Y.; Weng, C.; Wei, W.-Q.; et al. Enhancing Genetic Association Power in Endometriosis through Unsupervised Clustering of Clinical Subtypes Identified from Electronic Health Records 2024.

- Pujol Gualdo, N.; Džigurski, J.; Rukins, V.; Pajuste, F.-D.; Wolford, B.N.; Võsa, M.; Golob, M.; Haug, L.; Alver, M.; Läll, K.; et al. Atlas of Genetic and Phenotypic Associations across 42 Female Reproductive Health Diagnoses. Nat Med 2025, 31, 1626–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guare, L.A.; Das, J.; Caruth, L.; Rajagopalan, A.; Akerele, A.T.; Brumpton, B.M.; Chen, T.-T.; Kottyan, L.; Lin, Y.-F.; Moreno, E.; et al. Expanding the Genetic Landscape of Endometriosis: Integrative -Omics Analyses Uncover Key Pathways from a Multi-Ancestry Study of over 900,000 Women 2024.

- Benkhalifa, M.; Menoud, P.A.; Piquemal, D.; Hazout, J.Y.; Mahjoub, S.; Zarquaoui, M.; Louanjli, N.; Cabry, R.; Hazout, A. Quantification of Free Circulating DNA and Differential Methylation Profiling of Selected Genes as Novel Non-Invasive Biomarkers for Endometriosis Diagnosis. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papari, E.; Noruzinia, M.; Kashani, L.; Foster, W.G. Identification of Candidate microRNA Markers of Endometriosis with the Use of Next-Generation Sequencing and Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction. Fertility and Sterility 2020, 113, 1232–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustafa, S.; Burn, M.; Mamillapalli, R.; Nematian, S.; Flores, V.; Taylor, H.S. Accurate Diagnosis of Endometriosis Using Serum microRNAs. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2020, 223, 557.e1–557.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravaggi, A.; Bergamaschi, C.; Galbiati, C.; Zanotti, L.; Fabricio, A.S.C.; Gion, M.; Cappelletto, E.; Leon, A.E.; Gennarelli, M.; Romagnolo, C.; et al. Circulating Serum Micro-RNA as Non-Invasive Diagnostic Biomarkers of Endometriosis. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, S.D.; Moeini, A.; Rastegar, T.; Amidi, F.; Saffari, M.; Zhaeentan, S.; Akhavan, S.; Moradi, B.; Heydarikhah, F.; Takzare, N. Diagnostic Accuracy of Plasma microRNA as a Potential Biomarker for Detection of Endometriosis. Systems Biology in Reproductive Medicine 2025, 71, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoeman, E.M.; Bringans, S.; Peters, K.; Casey, T.; Andronis, C.; Chen, L.; Duong, M.; Girling, J.E.; Healey, M.; Boughton, B.A.; et al. Identification of Plasma Protein Biomarkers for Endometriosis and the Development of Statistical Models for Disease Diagnosis. Human Reproduction 2025, 40, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasamoto, N.; Ngo, L.H.; Vitonis, A.F.; Dillon, S.T.; Aziz, M.; Shafrir, A.L.; Missmer, S.A.; Libermann, T.A.; Terry, K.L. Prospective Evaluation of Plasma Proteins in Relation to Surgical Endometriosis Diagnosis in the Nurses’ Health Study II. eBioMedicine 2025, 115, 105688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominoni, M.; Pasquali, M.F.; Musacchi, V.; De Silvestri, A.; Mauri, M.; Ferretti, V.V.; Gardella, B. Neutrophil to Lymphocytes Ratio in Deep Infiltrating Endometriosis as a New Toll for Clinical Management. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 7575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wójtowicz, M.; Zdun, D.; Owczarek, A.J.; Skrzypulec-Plinta, V.; Olszanecka-Glinianowicz, M. Evaluation of Proinflammatory Cytokines Concentrations in Plasma, Peritoneal, and Endometrioma Fluids in Women Operated on for Ovarian Endometriosis—A Pilot Study. IJMS 2025, 26, 5117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimber-Trojnar, Ż.; Pilszyk, A.; Niebrzydowska, M.; Pilszyk, Z.; Ruszała, M.; Leszczyńska-Gorzelak, B. The Potential of Non-Invasive Biomarkers for Early Diagnosis of Asymptomatic Patients with Endometriosis. JCM 2021, 10, 2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petr Klezl; Pavla Svobodova; Eliska Pospisilova; Vilem Maly; Vladimir Bobek; Katarina Kolostova Morphology of Mitochondrial Network in Disseminated Endometriosis Cellsin Spontaneous Pneumothorax Diagnostic Process. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 2024, 70, 25–29. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Cheng, H.; Zhu, H.; Yu, X.; Ye, X.; Chang, X. Precise Capture of Circulating Endometrial Cells in Endometriosis. Chinese Medical Journal 2024, 137, 1715–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhu, H.-L.; Tang, Z.-W.; Neoh, K.H.; Ouyang, D.-F.; Cui, H.; Cheng, H.-Y.; Ma, R.-Q.; Ye, X.; Han, R.P.S.; et al. Evaluation of Circulating Endometrial Cells as a Biomarker for Endometriosis. Chin Med J (Engl) 2017, 130, 2339–2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guder, C.; Heinrich, S.; Seifert-Klauss, V.; Kiechle, M.; Bauer, L.; Öllinger, R.; Pichlmair, A.; Theodoraki, M.-N.; Ramesh, V.; Bashiri Dezfouli, A.; et al. Extracellular Hsp70 and Circulating Endometriotic Cells as Novel Biomarkers for Endometriosis. IJMS 2024, 25, 11643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Lu, Q.; Chen, M.; Zhao, X.; Chu, C.; Zhang, C.; Yuan, J.; Liu, H.; Lash, G.E. Impact of Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals (EDCs) on Epigenetic Regulation in the Uterus: A Narrative Review. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology 2025, 23, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromer, J.G.; Wu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Taylor, H.S. Hypermethylation of Homeobox A10 by in Utero Diethylstilbestrol Exposure: An Epigenetic Mechanism for Altered Developmental Programming. Endocrinology 2009, 150, 3376–3382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bromer, J.G.; Zhou, Y.; Taylor, M.B.; Doherty, L.; Taylor, H.S. Bisphenol-A Exposure in Utero Leads to Epigenetic Alterations in the Developmental Programming of Uterine Estrogen Response. FASEB J 2010, 24, 2273–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallée, A.; Ceccaldi, P.-F.; Carbonnel, M.; Feki, A.; Ayoubi, J.-M. Pollution and Endometriosis: A Deep Dive into the Environmental Impacts on Women’s Health. BJOG 2024, 131, 401–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Renzo, G.C.; Conry, J.A.; Blake, J.; DeFrancesco, M.S.; DeNicola, N.; Martin, J.N.; McCue, K.A.; Richmond, D.; Shah, A.; Sutton, P.; et al. International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics Opinion on Reproductive Health Impacts of Exposure to Toxic Environmental Chemicals. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2015, 131, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S.; Banu, S.K.; Arosh, J.A. Endocrine Disruptors and Endometriosis. Reprod Toxicol 2023, 115, 56–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumph, J.T.; Stephens, V.R.; Archibong, A.E.; Osteen, K.G.; Bruner-Tran, K.L. Environmental Endocrine Disruptors and Endometriosis. Adv Anat Embryol Cell Biol 2020, 232, 57–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruder, E.H.; Hartman, T.J.; Goldman, M.B. Impact of Oxidative Stress on Female Fertility. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2009, 21, 219–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Agarwal, A.; Krajcir, N.; Alvarez, J.G. Role of Oxidative Stress in Endometriosis. Reprod Biomed Online 2006, 13, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giudice, L.C.; Oskotsky, T.T.; Falako, S.; Opoku-Anane, J.; Sirota, M. Endometriosis in the Era of Precision Medicine and Impact on Sexual and Reproductive Health across the Lifespan and in Diverse Populations. FASEB J 2023, 37, e23130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coccia, M.E.; Nardone, L.; Rizzello, F. Endometriosis and Infertility: A Long-Life Approach to Preserve Reproductive Integrity. IJERPH 2022, 19, 6162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casalechi, M.; Di Stefano, G.; Fornelli, G.; Somigliana, E.; Viganò, P. Impact of Endometriosis on the Ovarian Follicles. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology 2024, 92, 102430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, H.-L. Antral Follicle Count Is Reduced in the Presence of Endometriosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Reproductive BioMedicine Online 2021, 42, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanski, P.A.; Brady, P.C.; Farland, L.V.; Thomas, A.M.; Hornstein, M.D. The Effect of Endometriosis on the Antimüllerian Hormone Level in the Infertile Population. J Assist Reprod Genet 2019, 36, 1179–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozcan, P.; Sezer, F.; Altun, A.; Yildiz, C.; Timur, H.T.; Keles, E.C.; Dural, O.; Taha, H.S.; Saridogan, E. Potential Ability of Circulating INSL3 Level for the Prediction of Ovarian Reserve and IVF Success as a Novel Theca Cell–Specific Biomarker in Women with Unexplained Infertility and Diminished Ovarian Reserve. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2025, 23, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walasik, I.; Klicka, K.; Grzywa, T.M.; Szymusik, I.; Włodarski, P.; Wielgoś, M.; Pietrzak, B.; Ludwin, A. Circulating miR-3613-5p but Not miR-125b-5p, miR-199a-3p, and miR-451a Are Biomarkers of Endometriosis. Reproductive Biology 2023, 23, 100796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marí-Alexandre, J.; Barceló-Molina, M.; Belmonte-López, E.; García-Oms, J.; Estellés, A.; Braza-Boïls, A.; Gilabert-Estellés, J. Micro-RNA Profile and Proteins in Peritoneal Fluid from Women with Endometriosis: Their Relationship with Sterility. Fertility and Sterility 2018, 109, 675–684.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nothnick, W.B.; Peterson, R.; Minchella, P.; Falcone, T.; Graham, A.; Findley, A. The Relationship and Expression of miR-451a, miR-25-3p and PTEN in Early Peritoneal Endometriotic Lesions and Their Modulation In Vitro. IJMS 2022, 23, 5862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muraoka, A.; Yokoi, A.; Yoshida, K.; Kitagawa, M.; Bayasula; Murakami, M.; Miyake, N.; Sonehara, R.; Nakamura, T.; Osuka, S.; et al. Serum-Derived Small Extracellular Vesicles as Biomarkers for Predicting Pregnancy and Delivery on Assisted Reproductive Technology in Patients with Endometriosis. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 15, 1442684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salmasi, S.; Heidar, M.S.; Khaksary Mahabady, M.; Rashidi, B.; Mirzaei, H. MicroRNAs, Endometrial Receptivity and Molecular Pathways. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2024, 22, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dabi, Y.; Suisse, S.; Puchar, A.; Delbos, L.; Poilblanc, M.; Descamps, P.; Haury, J.; Golfier, F.; Jornea, L.; Bouteiller, D.; et al. Endometriosis-Associated Infertility Diagnosis Based on Saliva microRNA Signatures. Reproductive BioMedicine Online 2023, 46, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, M.; Xia, Y.; Chen, X.; Xian, Y.; Lin, D.; Xie, S.; Guo, X. Oxidative Stress and Inflammatory Markers in Ovarian Follicular Fluid of Women with Diminished Ovarian Reserve during in Vitro Fertilization. J Ovarian Res 2023, 16, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voros, C.; Varthaliti, A.; Athanasiou, D.; Mavrogianni, D.; Papahliou, A.-M.; Bananis, K.; Koulakmanidis, A.-M.; Athanasiou, A.; Athanasiou, A.; Zografos, C.G.; et al. The Whisper of the Follicle: A Systematic Review of Micro Ribonucleic Acids as Predictors of Oocyte Quality and In Vitro Fertilization Outcomes. Cells 2025, 14, 787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadbhajne, P.; More, A.; Dzoagbe, H.Y. The Role of Endometrial Microbiota in Fertility and Reproductive Health: A Narrative Review. Cureus 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enciso, M.; Medina-Ruiz, L.; Ferrández-Rives, M.; Jurado-García, I.; Rogel-Cayetano, S.; Aizpurua, J.; Sarasa, J. P-293 Influence of the Endometrial Microbiota Composition on the Clinical Outcomes of Egg Donation PGT-A Cycles with Controlled Endometrial Receptivity. Human Reproduction 2024, 39, deae108.660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Wang, M.; Zhong, J.; Xue, H. Altered Endometrial Microbiota Profile Is Associated With Poor Endometrial Receptivity of Repeated Implantation Failure. American J Rep Immunol 2024, 92, e70005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Chen, H.; Zou, H.; Zhang, H.; Liu, S.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, S.; Hu, L. Impact of Vaginal Microecological Differences on Pregnancy Outcomes and Endometrial Microbiota in Frozen Embryo Transfer Cycles. J Assist Reprod Genet 2024, 41, 929–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh, H.; Sashihara, T.; Hosono, A.; Kaminogawa, S.; Uchida, M. Lactobacillus Gasseri OLL2809 Inhibits Development of Ectopic Endometrial Cell in Peritoneal Cavity via Activation of NK Cells in a Murine Endometriosis Model. Cytotechnology 2011, 63, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ser, H.-L.; Au Yong, S.-J.; Shafiee, M.N.; Mokhtar, N.M.; Ali, R.A.R. Current Updates on the Role of Microbiome in Endometriosis: A Narrative Review. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Huang, S.; Ma, S.; Chen, Y.; Cao, Y.; Ma, Y. Gut Microbiome in Patients with Early-Stage and Late-Stage Endometriosis. BMC Women’s Health 2025, 25, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]