1. Introduction

Archaeological feature detection plays a vital role in uncovering the secrets of the past, informing decision-makers to select more informed choices that balance development needs with the preservation of cultural heritage, advancing scientific knowledge, and engaging the public in exploring human history [

1]. Across millennia, ancient settlements, roads, fortifications, and agricultural systems have left lasting marks on the landscape, providing invaluable insights into past human behaviors, social structures, and technological advancements [

2]. By carefully detecting and analyzing these features, archaeologists can piece together the complex network of ancient civilizations, shedding light on their history and cultural dynamics. Moreover, archaeological research provides crucial data that help scholars refine historical chronologies, understand trade networks, and reconstruct environmental changes that shaped human societies over time.

Yet, the preservation of archaeological sites faces countless threats, ranging from urban development, looting and wars to erosion and climate change [

3]. Unregulated construction projects, mining activities, and expanding infrastructure often lead to the destruction of historically significant landscapes before their significance is even recognized [

1]. The timely detection and documentation of archaeological features not only aid in safeguarding cultural heritage sites but also inform crucial land use planning and resource management decisions [

4]. By identifying the locations of ancient settlements, burial sites, and other cultural features, potential damage from development projects can be mitigated, and conservation measures can be implemented to ensure the sustainable protection of heritage assets. Moreover, archaeological feature detection contributes significantly to interdisciplinary research, bridging fields such as anthropology, history, geography, and environmental science [

5]. The extensive dataset obtained from archaeological surveys and excavations helps test hypotheses, refine chronologies, and deepen our understanding of human-environment interactions over time. Furthermore, discoveries from archaeological feature detection enrich educational programs, museum exhibits, and public outreach initiatives, fostering curiosity and appreciation for cultural diversity among the general public [

6]. By sharing the stories of past civilizations and the methods used to uncover their secrets, archaeologists inspire a sense of wonder and respect for our shared human history.

In their effort to uncover hidden features of ancient landscapes, archaeologists are increasingly turning to advanced geomatics technologies. Geographic Information Systems (GIS), Remote Sensing (RS) techniques such as LiDAR and Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR), and Artificial Intelligence (AI) have become indispensable tools, enabling the analysis and interpretation of terrain features with unprecedented precision [

7]. For instance, SAR technology offers unique capabilities for identifying buried archaeological features; examples are the case of Ostia-Portus in Italy, Uyuk River Valley in Russia, and Apamea site in Syria , where multi-band SAR successfully identified shallow-buried paleochannels, burial mounds, and looting pits, respectively [

8]. To enhance the archaeological detection, SAR data can be fused to optical imagery. However, due to its complexity and need for further validation, its application is challenging [

9]. These technologies facilitate large-scale archaeological surveys, reducing the need for invasive excavation methods and allowing researchers to explore sites that are otherwise inaccessible due to dense vegetation or challenging terrain. Among these technologies, LiDAR data and AI have emerged as potent tools for detecting archaeological features efficiently and accurately, offering invaluable insights into preserving endangered sites and discovering new archaeological areas [

10]. Additionally, AI techniques such as Machine Learning (ML) and Deep Learning (DL) facilitate archaeological features' classification, identification, and segmentation, opening new avenues for archaeological research.

This technical note aims to critically examine recent archaeological studies that have employed derivatives of airborne (aerial) LiDAR point cloud data such as Digital Elevation Models (DEMs) and ML techniques for archaeological site detection, highlighting the significance of these approaches and identifying critical research gaps and future research prospects. While various studies have explored the role of AI in archaeology and cultural heritage, they have primarily focused on different methodologies applied to various RS datasets. For instance, [

10] concentrates solely on employing DL approaches on diverse RS data (e.g., aerial photogrammetry, SAR, multispectral satellite imagery, and LiDAR) for digital preservation and object detection. Similarly, the focus of [

1] is solely on one DL methodology (i.e., Convolutional Neural Network (CNN)) resulting in the review of six case studies using different RS data. [

11] focuses on state-of-the-art technologies related to AI and RS, while [

12] primarily centers on Semantic Segmentation (SS) of point cloud data derived from LiDAR and photogrammetry for digital orthophoto mapping, damage investigations, object recognition, Building Information Model (BIM) and historical BIM. Furthermore, several reviews have concentrated on the application of LiDAR as well as other unmanned aircraft systems in archaeology and cultural heritage [

13,

14]. Moreover, [

15] explicitly examines the airborne LiDAR data processing workflow. However, these reviews only partially focused on utilizing ML for archaeological feature detection from airborne LiDAR derivatives, which constitutes the primary focus of this study.

3. Airborne LiDAR Technology in Archaeological Feature Detection

The 21st century marks the initiation of using LiDAR data in archaeological exploration [

16]. One of the earliest notable applications has been carried out in the UK, where LiDAR was utilized to identify and document earthwork traces of a Roman Fort in West Yorkshire, which traditional detection methods had overlooked [

17]. Initially developed for terrain mapping and vegetation analysis, LiDAR's role has expanded to include the detection of hidden archaeological features, particularly in areas where traditional survey methods face limitations [

18]. This growing recognition of LiDAR’s capabilities has paved the way for its integration into archaeological research worldwide.

Airborne LiDAR technology is an active and non-invasive surveying method that utilizes laser scanning to generate highly detailed three-dimensional (3D) maps of the terrain surface, creating detailed 3D point clouds over vast areas. A standard airborne LiDAR setup comprises Airborne Laser Scanning (ALS), aircraft positioning by Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS), and an Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) [

7]. A laser scanner, typically mounted on an aircraft like a plane, helicopter or drone, emits pulses, generally in the Near-Infrared Range (NIR), at average frequencies of around one million pulses per second (1 MHz) in various directions along the flight path toward the ground [

19]. The initial commercial systems operated at 10 kHz and were bulky in size, while the contemporary systems are smaller, lighter, and can handle multiple laser returns [

20]. For each laser pulse that hits the surface, discrete return LiDAR systems [

19,

21] detect and record a limited number of returns, while full-waveform systems [

13,

18] record the entire backscattered energy profile (continuous signal). These pulses bounce off objects such as the ground surface, vegetation, and buildings, with their positions determined by calculating the time delay between emission and reception of each echo, along with the direction of the laser beam and the scanner's position [

22,

23]. In addition, bathymetric LiDAR has emerged as a specialized tool for underwater surveying. Unlike NIR LiDAR, which utilizes larger wavelengths, bathymetric LiDAR employs smaller wavelengths in the green spectrum to penetrate the water column effectively [

24]. While early iterations of bathymetric LiDAR faced limitations in return point density and spatial resolution, recent advancements have significantly improved instrument quality [

25]. This progress has enabled a wide range of archaeological applications, including documenting submerged sites.

Airborne LiDAR's primary application in archaeology has been identifying archaeological structures visible as topographic imprints on the ground surface [

17]. This technology has revolutionized archaeological surveying, enabling researchers to identify and analyze features such as ancient structures, roads, and burial mounds with improved accuracy. Airborne LiDAR offers a significant increase in spatial resolution compared to photogrammetric and satellite-derived products obtained from stereo or tristereo imagery [

26]. On the other hand, UAV photogrammetric surveys can be severely limited by the presence of vegetation and by georeferencing challenges, especially when establishing ground control points in hard-to-reach areas [

27]. LiDAR allows for the filtering of vegetation, buildings, and other man-made structures to create high-resolution bare-soil Digital Terrain Models (DTMs), which can aid in the detection of archaeological remains. However, in areas with sparse ground returns, such as dense vegetation or urban settings, the ground surface must be interpolated which can reduce the quality of DTMs [

4,

15] and as a result, the accuracy of archaeological feature detection. The combination of LiDAR-based DTMs and visualization techniques has contributed to important discoveries in both well studied archaeological areas and previously overlooked regions due to dense vegetation cover [

7]. Besides its efficiency in data acquisition, airborne LiDAR can support the identification of buried or partially buried archaeological features such as ancient trenches, roadways, and agricultural fields [

28,

29,

30,

31], as well as geoarchaeological features in low-relief alluvial landscapes [

32]. Additionally, for some countries, airborne LiDAR data is already accessible online immediately or upon request, offering economic benefits as it is more cost-effective and efficient than traditional methods [

33]. However, the quality of LiDAR data is crucial for accurate and reliable results in various applications, with point density as a key parameter to assess quality. Point density, representing the number of LiDAR points per unit area, which can directly influence the level of detail and precision of derived products [

33,

34]. Ensuring adequate point density and transparency in reporting are essential for maximizing the utility and trustworthiness of LiDAR-derived information across diverse applications [

35]. Regular updates and monitoring of surveyed and mapped areas are also necessary [

19]. Other challenges and limitations to this technology include high initial investment costs, managing and interpreting large data volumes, vulnerability to weather and environmental conditions affecting data collection, as well as logistical obstacles related to site access, permissions, and data privacy [

36]. It furthermore requires collaborations between archaeologists and RS experts, ensuring a more comprehensive and deeper data analysis.

Airborne LiDAR technology can reveal not only visible archaeological structures but also hidden features that are often difficult to detect using traditional methods. These hidden features, such as buried structures, roads, and agricultural fields, are of great significance in archaeological research [

36]. By revealing well preserved sites obscured by natural factors such as dense vegetation or soil erosion, LiDAR enables archaeologists to explore previously overlooked regions and gain a deeper understanding of human history and culture [

37]. This aspect of LiDAR technology highlights its potential to revolutionize the study of civilizations that have long since disappeared, offering new interpretations of their social, economic, and environmental systems [

36,

38]. Some of the most significant findings facilitated by airborne LiDAR technology in archaeology include the mapping of hidden cities and vast urban complexes, such as the expansive Maya civilization in Central America [

21] and the elaborate network of Angkor in Cambodia [

34,

39], as well as evidence of the architectural sophistication of ancient civilizations, showcasing elaborate structures like earthworks [

40], complex road networks [

28] used for trade and communication, hidden agricultural fields [

2], and defensive structures [

10]. Airborne LiDAR has significantly enhanced the visualization and mapping of ancient cities and extensive landscapes previously obscured by dense vegetation or sediment accumulation.

4. Machine Learning in Archaeological Feature Detection

Methods for detecting archaeological features have evolved from subjective approaches, which rely primarily on personal interpretation without clear and standardized criteria [

41], to more scientific ones, aided by computing technology. Archaeological feature detection involves field surveys, RS, and integrating RS with AI [

7,

11]. The fusion of RS data with AI marks a new era in archaeology. ML algorithms, a subset of AI, have become indispensable tools for processing and analyzing large volumes of data in archaeological contexts. Traditional techniques often suffer from limited coverage, subjective interpretation, and unquantified error rates, leading to false positives (detecting features that are not actually archaeological) and false negatives (missing actual archaeological features) [

6,

38,

42,

43], which ML blended with RS can overcome by creating a systematic solution [

11]. ML is broadly defined as the capacity of intelligent systems to learn and improve from prior data [

1]. It involves optimizing a model to transform input into a desired output with increasing efficiency [

44,

45]. This optimization process, known as training, is performed using a relevant set of training data. ML algorithms are trained to derive mathematical classifiers or feature vectors and apply them to extract, sort, classify, and interpret new data [

44]. AI uses such ML models to automate decision-making and data analysis. ML has been successfully applied in various domains of computer science, including computer vision, data classification, knowledge extraction, and speech recognition [

1,

44,

45]. They can be applied to a range of digital data, with the most common types being numerical/categorical data, images, and geospatial data [

6,

44,

46].

ML methods are categorized into supervised learning, unsupervised learning, and reinforcement learning. A fourth category, semi-supervised, is also sometimes mentioned [

1,

45]. The fundamental difference often lies in the type of training data and whether these data have known outputs or labels [

47]. Supervised learning involves training models using data with known labels to learn a mapping function that can accurately predict the output for new, unseen inputs [

1,

45]. This process involves iteratively refining the model based on the provided training data. Common supervised learning tasks are divided into two main groups, regression and classification. Regression tasks aim to learn a real-valued function for continuous outputs, while a classification task assigns input elements to a predefined set of discrete categories or labels [

45]. Examples of common supervised algorithms include decision trees, maximum likelihood, Random Forests (RF), Support Vector Machine (SVM), Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), and DL models like CNNs [

29,

30,

42,

48,

49]. SVM, maximum likelihood, and ANNs are commonly used for classifying raster and images with training data that are created by drawing polygons around known objects [

29,

48]. Conversely, in unsupervised learning the objective is to find structure, patterns, and inherent groupings within the unlabeled data autonomously [

1,

45]. Unlabeled data helps the model learn and gain familiarity by attempting to make predictions without knowing the true targets [

47], and it can be optimal when features of interest are not previously known [

39]. Clustering algorithms are among the most widely used methods in archaeology and cultural heritage for discovering patterns and structures in unlabeled datasets [

50]. The simplest and most commonly used clustering algorithm is K-mean [

50], which is also integrated into advanced architectures

1 like PointNet++ for hierarchical point grouping [

51]. Reinforcement learning, with its common Q-learning algorithm, trains models through rewards and penalties [

1,

52].

DL is an advanced form of ML originated in the 1940s with the goal of mimicking human brain functions [

53]. After facing challenges like overfitting and limited data, DL regained popularity in 2006 due to its significant advancements achieved in speech recognition [

10]. The term

deep refers to the development of neural networks with more than one hidden layer [

1,

47,

49,

53]. Deep Neural Networks (DNNs) facilitate automated learning by iterating through massive amounts of data in images, text, or videos [

30]. They seek to exploit the unknown structure in the input data distribution to discover good representations, often at multiple levels [

53]. In other words, DL models build understanding in a hierarchical way, where complex features are composed of simpler ones learned in earlier layers and without human needs to define those features explicitly [

1,

49,

53]. DNNs are composed of simple, highly interrelated processing units called neurons, organized in multiple layers [

53]. There is an input layer, one or more intermediate or hidden layers, and a final output layer [

49]. The connections between neurons are represented mathematically by trainable parameters called weights [

53,

54]. The training process begins with the input of raw data, such as images, text, video, or spatial datasets like DTMs, Local Relief Models (LRMs), or 3D point clouds [

20,

30,

40,

55,

56,

57,

58]. During forward propagation, this data is passed through multiple layers of the network where each neuron computes a non-linear activation on the weighted sum of its inputs and transmits the signal forward [

21,

43,

46,

49,

53,

59]. The most common used activation function is Rectified Linear Units (ReLU

2) [

21,

46,

59]. As the data progresses through the hidden layers, the network performs feature extraction and automatically learns to detect increasingly complex patterns [

1,

47,

49]. This is a key distinction of DL from classical ML. The final output layer generates predictions depending on the task: this may include class probabilities [

3,

31], classifications [

3,

31], or segmentations [

60]. The goal of training is to adjust the model's weights to minimize the difference between the model's output and the desired output for a given task [

3,

53,

56]. After each forward pass, a loss function measures prediction error [

53,

59]. Then, back propagation propagates the loss information backward through the network and computes gradients which indicates the contribution of each weight to the error [

21,

53]. An optimizer then uses these gradients to adjust the trainable weights, aiming to minimize the loss function [

53,

56,

59]. Training runs in steps called epochs where each one involves a full forward and backward pass of all training data through the network [

2,

53]. After each epoch or a set of epochs, model performance is validated using unseen data to ensure generalization and prevent overfitting [

2,

47].

DL is a step further within ML, with models that follow the same methodologies (such as classification and regression) but are based on ANNs, and can significantly improve accuracy with increased data availability [

1,

3,

49,

61]. However, it requires more extended training but shorter inference times than traditional ML algorithms, relying on large datasets for better accuracy [

44]. A key difference between classical ML techniques and DL is that while the former often need feature engineering (i.e., selecting, transforming, or creating new features from raw data), human experts to carefully select input features (such as spectral indices), and the prior calculation and determination of a range of possible statistically significant input features [

40], the later performs feature extraction by itself [

1]. In other words, DL algorithms can identify and extract meaningful patterns or features directly from raw data, which can be particularly time-saving and advantageous when working with complex and high-dimensional datasets [

1,

49]. Similar to ML, DL encompasses different types of learning (i.e., supervised, unsupervised, reinforcement learning) [

1,

45]. However, DL models generally require considerable computational resources [

40] and large amounts of data to achieve higher accuracy [

3,

61]. Traditional ML methods might be more applicable or sufficient when dealing with limited datasets or specific cases where targets have limited spectral and geometric variations [

49].

Based on the task, DL models can be categorized by their output. First are object detection models that identify and locate specific objects within an image, typically drawing a bounding box around them and providing a probability of the object's presence [

3,

62]. Examples of object detection architectures include R-CNN, Faster R-CNN, YOLOv5, and YOLOv4 [

3,

57,

62,

63]. In addition, SS models classify each pixel of an image with a corresponding class, defining semantic regions and segmenting them [

21,

62]. This provides both the classification and position of archaeological structures [

3]. Examples of SS architectures include Faster R-CNN, U-Net, Mask R-CNN, ResUnet, and FCN [

3,

62]. CNNs are among the most studied architectures, especially when the input data are images and videos [

1,

3,

43,

61]. They have been successfully used in various image applications, including image classification, object recognition, video classification, and scene labeling [

3,

61]. Different CNN architectures exist with variation in their layer organization [

21].

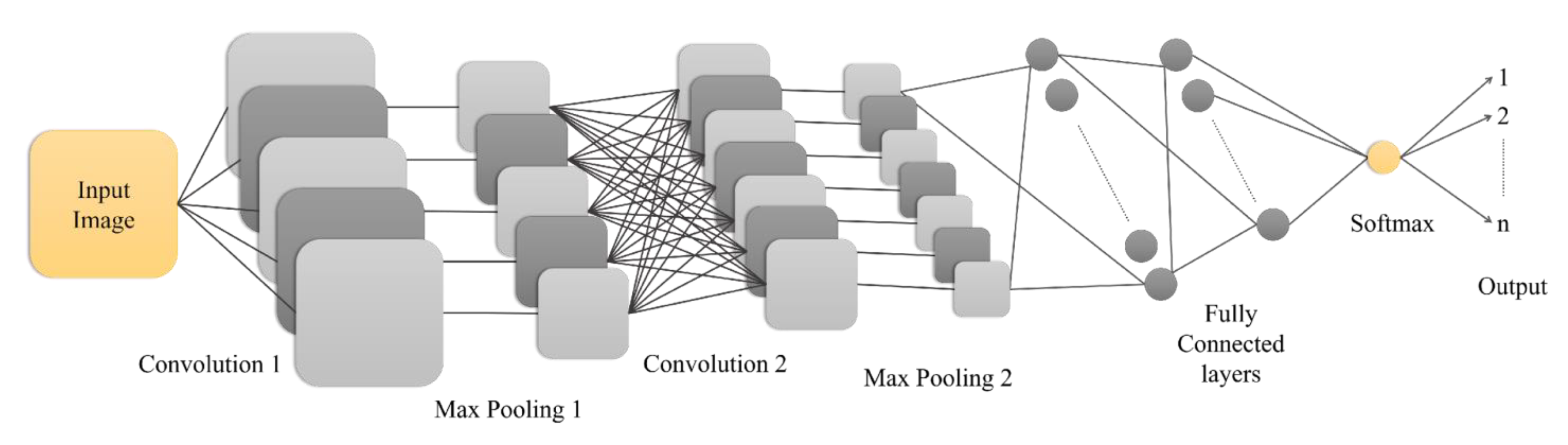

Figure 1 demonstrates an example of a simple CNN architecture, in which the input image passes through multiple convolutional layers that extract local features such as edges and textures [

3,

61]. The pooling layers help reduce spatial dimensions and control overfitting by preserving the most relevant features. The extracted features are then fed into fully connected layers that interpret the information for classification. Finally, an activation function called SoftMax

3 is applied to the classes. This assigns probabilities to different classes, enabling the network to learn hierarchical representations of data automatically [

47,

61].

Figure 1.

Structure of a simple Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) architecture for n-class classification. The input image undergoes two convolutional and pooling operations, extracting hierarchical features. The resulting feature map is flattened and passed through two fully connected layers. Finally, a Softmax activation function is applied to the output of the last fully connected layer, converting it into a vector of n probabilities corresponding to the classification classes.

Figure 1.

Structure of a simple Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) architecture for n-class classification. The input image undergoes two convolutional and pooling operations, extracting hierarchical features. The resulting feature map is flattened and passed through two fully connected layers. Finally, a Softmax activation function is applied to the output of the last fully connected layer, converting it into a vector of n probabilities corresponding to the classification classes.

Although CNNs typically perform best with large amounts of labeled data, in many real-world scenarios, such data may be limited. In these cases, Transfer Learning (TL) can offer an effective approach to mitigate this challenge. TL is a technique that applies the knowledge gained from solving one problem to a different but related problem [

3]. The core idea is to reuse a model that has been pre-trained on a large amount of data (for instance on ImageNet dataset) for a source problem to solve a target problem where only limited data is available [

3]. However, differences between the characteristics of the original training data (for instance, standard computer vision images) and the new data (such as aerial LiDAR-derived images with different scale and rotation properties) need to be considered [

43]. TL is typically achieved by retraining only a few selected layers of the pre-trained model on the new dataset [

3,

43]. Common strategies for applying TL include removing the final layer of the pre-trained network and replacing it with a new layer suited for the target classification categories, or fine-tuning the model by adding new training parameters [

43]. In fine-tuning, either all model weights can be updated, or the weights in the lower layers can be frozen while only updating the upper layers [

43]. Studies indicate that TL can significantly improve model accuracy in situations where the available data for training is limited [

2,

3,

61,

64]. This technique directly addresses a major challenge in DL, which is the requirement for vast amounts of labeled training data to achieve higher accuracy [

1,

3,

61]. While commonly associated with CNNs, TL can be applied to various ML paradigms, including supervised and unsupervised learning [

24]. Its advantages include reduced training time and data requirements, improved generalization, and the ability to address domain shift [

54]. However, its effectiveness depends on the similarity between the source and target domains, and there is a risk of overfitting especially when the target dataset is small or significantly different from the source dataset [

43,

54,

65]. Despite these limitations, TL remains a valuable technique for accelerating model development, improving performance, and addressing challenges in diverse ML applications, particularly in archaeological contexts with data limitations and small sample sizes [

24,

43,

54,

65].

Building on the capabilities of RS data, ML aims to train algorithms to learn from these data to make predictions or decisions. It has shown potential in automating archaeological feature detection, such as the use of RF algorithms for the detection of burial mounds in France and Spain [

55], Viking ring fortresses throughout Denmark [

66], ancient canals in Belize, Central America [

67], and the use of CNN to detect ancient Maya structures in Guatemala [

21]. These advancements hold significant potential for revolutionizing archaeological research by offering efficient, accurate, and scalable feature detection and analysis methods.

5. Past Research Applying Machine Learning on Airborne LiDAR Derivatives for Archaeological Feature Detection

Over the past four decades, advancements in RS, ML, and cloud computing have revolutionized our ability to explore ancient landscapes, with airborne LiDAR technology playing a pivotal role in improving spatial resolution for surveys of previously inaccessible forested areas [

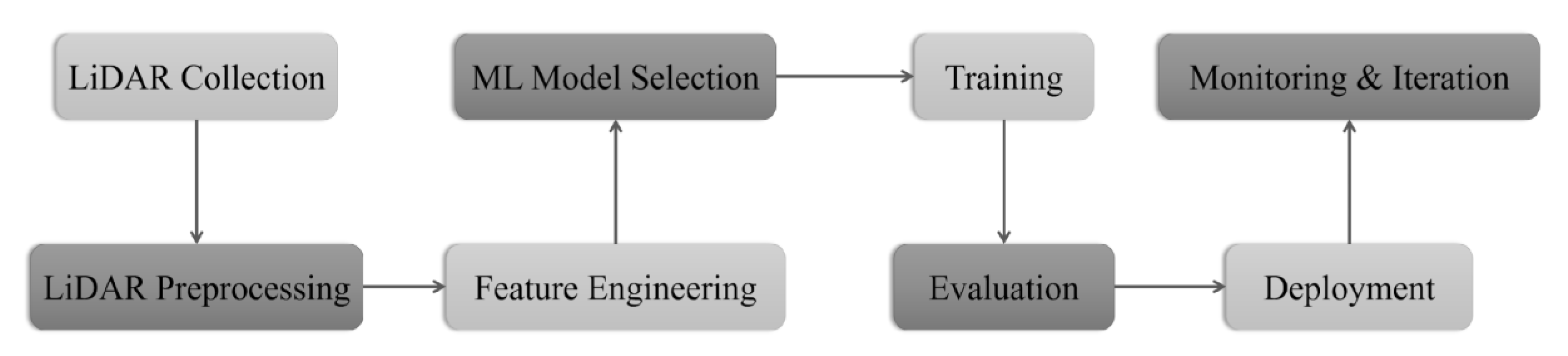

67]. The systematic approach for applying ML techniques to airborne LiDAR data for archaeological feature detection starts with carefully collecting and preprocessing LiDAR and archaeological datasets, ensuring data quality and compatibility. Feature engineering follows, wherein relevant attributes are extracted and engineered to enhance the model's ability to identify archaeological features from the LiDAR derivatives. A critical decision point arises in model selection, where the choice between traditional ML algorithms and DL architectures is made, with the possibility of including TL on pre-trained models. The subsequent steps involve rigorous training and evaluation of the selected model, ensuring its robustness and generalization to unseen data. Once validated, the model is deployed for archaeological feature detection on new airborne LiDAR datasets. Continuous monitoring of the model's performance in real-world applications enables improvements as necessary, thereby ensuring the efficacy of the archaeological research efforts (

Figure 2).

The core idea of each ML/DL model is the ability to perform well on data that has not been seen during training [

6,

47]. Ensuring and evaluating this ability, known as

generalization, involves several techniques. The foundation of good generalization lies in having a sufficient amount of high-quality, representative training data [

21,

33,

68]. However, collecting large, labeled datasets can be challenging, particularly in specialized domains like archaeology [

1,

20,

43,

44,

69,

70]. Furthermore, using a separate validation dataset [

19] as well as appropriate evaluation strategies [

71] could ensure generalization. Standard evaluation measures developed for general object detection tasks may not be suitable for archaeological applications due to the unique characteristics of archaeological objects and the importance of geospatial information for archaeologists [

71]. Another strategy to increase the robustness of the model is applying data augmentation [

3,

19,

55,

64]. This involves creating artificial training samples by applying various transformations (such as cropping, flipping, rotation, scaling, shifting) to the original data [

55]. Applying multi-directional hillshade or other visualization techniques to DEMs can also augment the training data [

3,

68]. For 3D point clouds, combining different augmentation methods, such as Gaussian noise and random rotation, has shown potential for improving DL models with small datasets [

3]. TL also can help with generalization [

43,

44,

54]. For instance, [

43] successfully reapplied TL of a deep CNN, initially trained on Lunar LiDAR datasets, for detecting historic mining pits [

43]. Choosing an architecture that can handle the multi-scale nature of archaeological features or integrate multiple data sources [

19,

35,

42,

69] and optimizing the model’s hyperparameters (such as the number of epochs) also enhances the model’s ability to generalize to unseen data [

2,

71,

72].

Integrating airborne LiDAR derivatives with ML algorithms for archaeological feature detection has been the subject of 45 case studies (locations of the studied area are demonstrated in

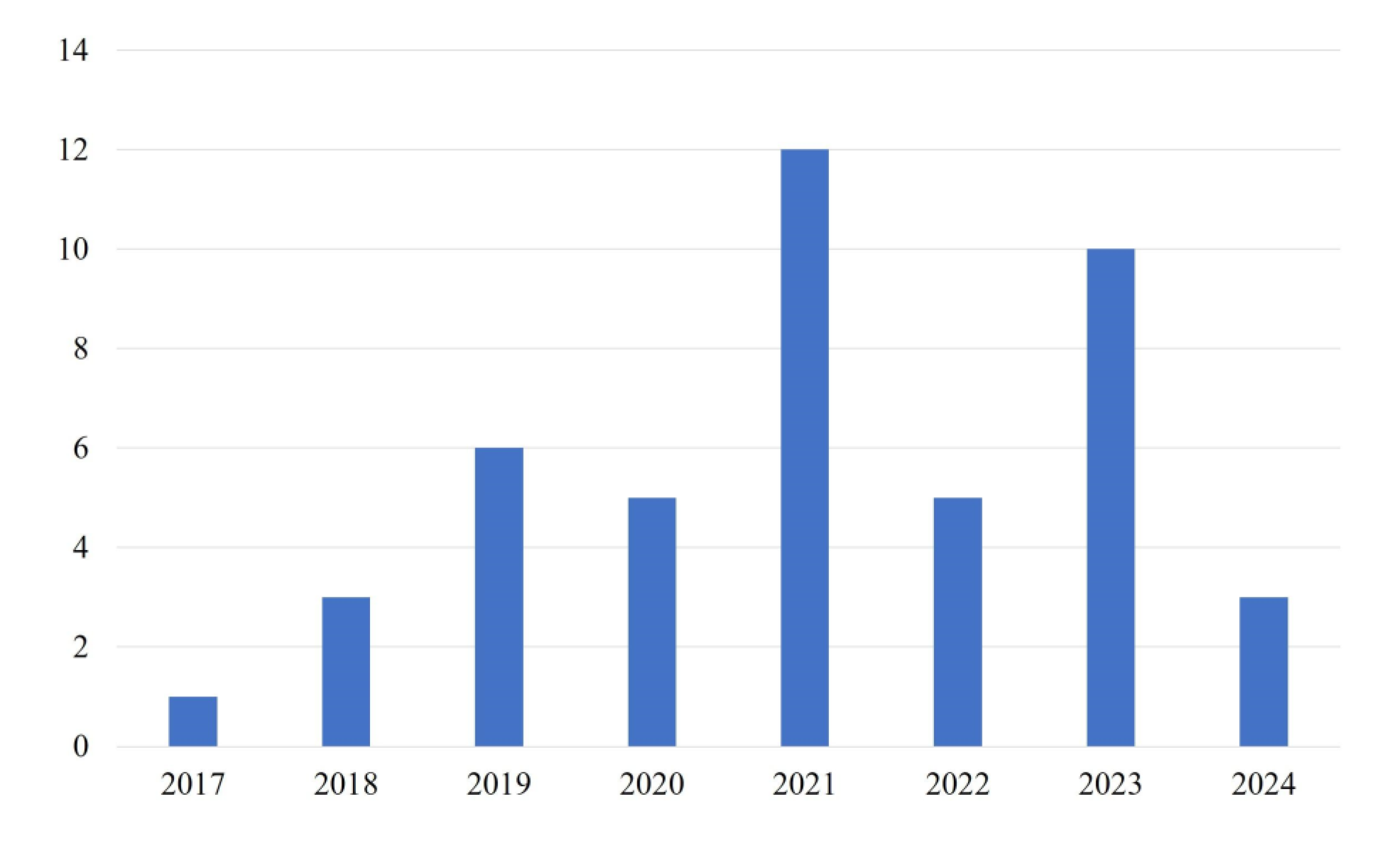

Figure 3), found after internet research.

Figure 4 displays a histogram representing the yearly distribution of these articles. This trend suggests a growing interest in the research topic, particularly around 2021 and 2023. On the Scopus website, a set of keywords was searched within the title, abstract, and keywords of review and scientific articles using the following advanced query:

TITLE-ABS-KEY ( "deep learning" OR "machine learning" OR "artificial intelligence" OR "AI" OR "semantic segmentation" OR "computer vision" )

AND TITLE-ABS-KEY ( "archaeolog*" OR "historical " OR "cultural" OR "heritage" )

AND TITLE-ABS-KEY ( ( "airborne" OR "aerial" ) AND ( "LiDAR" OR "laser" OR "point cloud" ) )

AND TITLE-ABS-KEY ( ( "object" OR "site" OR "pattern" OR "feature" ) AND ( "detection" OR "extraction" OR "recognition" ) )

AND ( LIMIT-TO ( DOCTYPE , "ar" ) OR LIMIT-TO ( DOCTYPE , "re" ) )

AND ( LIMIT-TO ( LANGUAGE , "English" ) ).

This search resulted in 41 articles. After a detailed screening, 15 were excluded for reasons such as duplicate records, irrelevant use of AI or ML, and absence of feature detection/extraction methods or insufficient methodological detail relevant to the scope of this work. The remaining 26 articles were presented in

Table 1. The same keywords were used to search Google Scholar within the same timeline (between 2017 and 2024) as the previous search. This search yielded 34 articles, 15 overlapping those on the Scopus website. The remaining 19 new articles were also added to

Table 1, resulting in a total of 45 articles. Of these, 32 used deep CNNs for automatic object detection, applying different architectures such as U-Net, YOLO, CarcassonNet, WODAN, VGG, Deeplab, and DeepMoon. However, as highlighted in some papers, their application in large-scale archaeological mapping may require further evaluation and extension, including the development of optimal training sample selection methods and evaluation of LiDAR-derived data as inputs [

16,

54,

71]. One article applied a DL model known as CMX mode, a fusion of SS with Transformers [

69]. Another study conducted a comparison between ML (RF) and DL (fully connected networks) [

35]. The remaining 11 case studies apply different ML algorithms such as SVM, unsupervised ISODATA, RF, and template matching classifiers to detect the archeological features in airborne LiDAR data (

Table 1).

Various studies have leveraged airborne LiDAR data and ML techniques to identify ancient structures and landscapes. For instance, Chinese ancient city walls were delineated using SS applied to DEMs derived from ALS data [

56]. Similarly, other studies have employed CNNs to detect walls and houses from derivatives of noisy airborne LiDAR data, with applications that extend to mapping ancient walls in different countries [

30,

40,

46,

48,

73,

74]. Additionally, deep semantic models have been proposed for predicting the locations of ancient agricultural terraces and walls, highlighting the potential of cost-effective raster data in transforming archaeological research [

29,

31,

35,

48,

75]. Such studies provide valuable references for ancient site detection and monitoring, offering insights into cultural heritage preservation and aiding in reconstructing urban structures and their functions.

Detection of burial mounds has been another focus, with ML and DL methods applied to elevation models derived from airborne LiDAR data [

20,

42,

55,

57,

76,

77]. Similarly, segmentation models trained from scratch have been used to detect clearance cairns in forested areas, enhancing understanding of historical agricultural activity and settlement organization [

2]. Innovative approaches employing ML-based detection have also been applied to Celtic fields, barrows, and charcoal kilns in airborne LiDAR data, showcasing the potential of automatic measures for archaeological research evaluation [

6,

22,

23,

62,

63,

65,

71,

78,

79,

80,

81]. Moreover, mapping Maya archaeological sites has been difficult due to their location in dense forests and rugged landscapes. Combining LiDAR data and CNNs can make it easier and more efficient to analyze these sites [

67,

68,

82]. Also, terrain and topographical features, such as hillforts, have been the focus of various studies [

50,

69,

70] employing different ML methods. Despite challenges such as the complexity of LiDAR data, these studies demonstrate encouraging potential, with proposed models freely available for other users to adapt to their needs.

In addition, TL has also been employed to reduce the cost and hazards of underwater archaeology using bathymetric LiDAR data [

24]. Techniques like Mask Regional based CNN (R-CNN) and segmentation have also been utilized to detect relict charcoal hearths and kilns, achieving impressive results in object detection and instance segmentation [

58,

77,

83]. Other innovative approaches, such as TL for detecting historic mining pits, have shown strong potential for broader archaeological tasks, which can demonstrate efficient semi-automated object detection and can distinguish between natural and manmade features [

43]. Similarly, ML approaches have been employed to detect Viking ring fortresses in Denmark and hollow roads using DL and image processing methods [

28,

61,

66]. Furthermore, DL and airborne LiDAR derivatives have been studied to detect archaeological shell rings, providing insights into native inhabitants and their socioeconomic networks [

64].

Table 1.

Case studies that applied different artificial intelligence methods on airborne LiDAR derivatives to detect archaeological features.

Table 1.

Case studies that applied different artificial intelligence methods on airborne LiDAR derivatives to detect archaeological features.

| Authors |

Archaeological Sites/Objects |

Study’s Location (Extent) |

LiDAR Derivative and Resolution |

Detection Method (Architecture/Algorithm) |

Quality Evaluation |

| [56] |

Ancient City Walls |

Jinancheng, China (16 km2) |

0.5m DEM1

|

CNN2 (U-Net segmentation) |

Precision 94.12% |

| [69] |

Hillforts |

England (130,000 km2), Alto Minho, Portugal (2,220 km2), Galicia, Spain (30,000 km2) |

1m DTM3; 0.5 and 2 points/m2

|

CMX4 (Semantic Segmentation) |

F1-score 66% |

| [68] |

Maya Structures |

Tabasco, Mexico (885 km2), Petén, Guatemala (615 km2) |

1m DEM; 2.07 points/m2 (ground) |

CNN (YOLOv3) |

F1-score 80% |

| [57] |

Burial Mounds |

Alto Minho, Portugal (2,220 km2) |

1m DTM |

Regional based-CNN (YOLOv3) |

Detection Rate 72.53% |

| [30] |

Ancient Agricultural Water Harvesting Systems (Terrace and Sidewall) |

Central Negev Desert, Israel (1,800 km2) |

0.125m DTM; 2 points/m2

|

CNN (modified U-Net) |

IoU5 53% |

| [70] |

Historical Terrain Anomalies |

Eifel Region, Germany (0.01 km2) |

DTM; 200-300 points/m2

|

ML6 (Support Vector Machine) |

Recall 76-80%

Precision 55-72%

F1-score 57-81% |

| [22] |

Pitfall Systems |

Suomenselka, Finland (6,778.9 km2) |

0.25m DEM; 5 points/m2

|

CNN (-) |

Reliability 80% |

| [23] |

Tar Production Kilns |

Kuivaniemi (2,760 km2), Hossa (2,004 km2), and Näljänkä (2,304 km2), Finland |

0.25m DEM; 5 points/m2

|

CNN (U-Net) |

Accuracy 93-95%

Precision 82-97%

Recall 72-99%

F1-score 77-97% |

| [74] |

Stone Walls |

Northeastern CT, USA (-) |

1m DEM |

CNN (U-Net) |

Recall 89%

Precision 93%

F1-score 91% |

| [29] |

Precolonial Stone-Walled Structures (Circular Homestead, Agricultural Terrace and Road) |

Thaba-Chweu, South Africa (31.25 km2) |

- |

ML (Support Vector Machine) |

Accuracy 95% |

| [67] |

Ancient Canals (Maya Wetland) |

Rio Bravo, Belize (~ 5 km2) |

0.5m DEM |

ML (Random Forest) |

Accuracy 66% |

| [31] |

Linear Structures (Embankment, Ditch, Hollow Path, etc.) |

Blois, France (270 km2) |

0.5m DTM |

ML (Support Vector Machine) |

- |

| [2] |

Clearance Cairns |

Söderåsen, Sweden (-) |

DTM;

0.5-1 points/m2

|

CNN (U-Net segmentation) |

Dice coefficient 84% |

| [71] |

Barrows and Celtic Fields |

Gelderland, The Netherlands (2,200 km2) |

0.5m DTM;

6-10 points/m2

|

Faster Regional based-CNN |

- |

| [46] |

Historic Stone Walls |

Aro, Denmark (88 km2) |

0.4m DTM |

CNN (U-Net segmentation) |

Accuracy 93% |

| [50] |

Archaeological Topography |

Perticara, Italy (106.45 km2) |

DEM;

142 points/m2

|

ML (Unsupervised ISODATA) |

- |

| [75] |

Ancient Agricultural Terraces and Walls |

Negev, Israel (-) |

- |

CNN (U-Net segmentation) |

Precision (Terrace 87%, Wall 60%) |

| [20] |

Celtic Fields and Burial Mounds |

The Białowieza Forest, Poland (697.8 km2) |

0.5m DTM; 11 points/m2

|

CNN (U-Net) |

F1-score 58%

IoU 50% |

| [24] |

Shipwreck |

Alaska, and Puerto Rico, USA (-) |

1m DEM |

TL7 CNN (YOLOv3) |

F1-score 92% |

| [54] |

Topographic Anomalies |

Brittany, France (200 km2) |

0.5m DTM;

14 points/m2

|

TL Mask Regional based-CNN (ResNet-101) |

Detection Accuracy

< 77% |

| [77] |

Grave mound, Pitfall trap, Charcoal Kiln |

Norway (937 km2) |

0.5m DTM;

5 points/m2

|

Faster Regional based-CNN |

Accuracy

~70% |

| [40] |

Earthwork Sites (Pit, Terrace, Sod Wall, Ditch) |

Northland, New Zealand (-) |

- |

Faster Regional based-CNN (ResNet-101) |

- |

| [48] |

Stone Wall, Pottery |

Chun Castle, UK (-) |

1m DSM |

ML (Support Vector Machine) |

Accuracy

>70% |

| [55] |

Burial Mounds |

Galicia, Spain (29,574 km2) |

1m DTM |

Regional based-CNN (YOLOv3) |

Detection Rate 89.5%, Precision 66.75% |

| [28] |

Trace Hollow Roads |

Veluwe, The Netherlands (93.75 km2) |

0.5m DTM |

CNN (CarcassonNet) |

Accuracy 89%, F1-score 42% |

| [63] |

Barrow, Celtic Field, Charcoal Kiln |

Veluwe, The Netherlands (2,200 km2) |

DTM;

6-10 points/m2

|

CNN (YOLOv4) |

Precision 64%, F1-score 76% |

| [64] |

Shell Rings |

South Carolina, USA (6,712 km2) |

1.5m DEM |

Mask Regional based-CNN |

Detection Accuracy ~75% |

| [35] |

Field Systems (Medieval Terraced Slopes, and Ridges and Furrows) |

Southern Vosges, France (1,462 km2) |

1m DEM;

5 points/m2

|

ML (Random Forest) and DL (Fully Connected Networks) |

F-score 64-91% (ML) and 55-77% (DL) |

| [62] |

Relict Charcoal Hearths |

New England, USA (493 km2) |

1m DEM;

2 points/m2

|

CNN (U-Net) |

F1-score 86% |

| [83] |

Relict Charcoal Hearth Sites |

Germany (3.4 km2) |

0.5m DEM

|

Modified Mask Regional based-CNN |

Recall 83%, Precision 87% |

| [79] |

Barrow, Celtic Field, Charcoal kiln |

Veluwe, The Netherlands (2200 km2) |

0.5m DTM;

6-10 points/m2

|

Faster Regional based-CNN (WODAN 2.0) |

F1-score 70% |

| [21] |

Maya Structures |

Petén, Guatemala (2144 km2) |

1m DEM |

Mask Regional based-CNN (U-Net) |

Classification Accuracy 95% |

| [82] |

Maya Settlements (Aguada, Building, Platform) |

Campeche, Mexico (230 km2) |

0.5m DEM;

14.7 points/m2 (ground) |

CNN (VGG-19) |

Accuracy 95% |

| [58] |

Bomb Crater, Charcoal Kiln, Barrow |

Harz mountains, Germany (47,000 km2) |

0.5m DTM |

CNN (Deeplab v3+) |

IoU6 76.8% |

| [76] |

Burial Mounds |

Romania (200 km2) |

0.5m DEM;

2-6 points/m2

|

ML (Random Forest) |

Identifying Accuracy 96% |

| [73] |

House, Wall, Pyramid, etc. |

Mexico (-) |

0.3m DEM |

CNN (VGG) |

Precision 97% |

| [43] |

Historic Mining Pits |

Dartmoor National Park, UK (-) |

0.25m and 0.5m DSM8

|

TL CNN (DeepMoon) |

Recall 80% (0.5m DSM) and 83% (0.25m DSM) |

| [78] |

Barrows and Celtic Fields |

Veluwe, The Netherlands (440 km2) |

LiDAR images;

6-10 points/m2

|

Regional based-CNN (WODAN) |

F1-score ~ 70% |

| [66] |

Viking Age Fortress |

Bornholm, Denmark (42,036 km2) |

1.6m DTM |

ML (Random Forest) |

- |

| [6] |

Barrow, Celtic Field, Charcoal Kiln |

Veluwe, The Netherlands (437.5 km2) |

LiDAR images;

6-10 points/m2

|

CNN (WODAN) |

- |

| [65] |

Prehistoric Roundhouses, Shieling Huts, Clearance Cairns |

Arran, Scotland (432 km2) |

0.25m DTM;

2.75 points/m2 (ground) |

TL CNN (ResNet-18) |

Detection Accuracy (Roundhouse 73%, Huts 26%, Cairns 20%) |

| [61] |

Hollow Way, Stream, Pathway, Lake, Street, Ditch, etc. |

Lower Saxony,

Germany (-) |

1m DTM |

Hierarchical CNN |

Classification Accuracy 91% |

| [42] |

Burial Mounds |

Brittany, France (246.7 km2) |

0.25m DTM;

14 points/m2

|

ML (Random Forest) |

- |

| [80] |

Grave, Mound, Pitfall Trap, Charcoal Burning Pit, Charcoal Kiln |

Oppland, Norway (29 km2) |

- |

ML (Template Matching) |

- |

| [81] |

Maori Storage Pits |

New Zealand (-) |

1m DEM |

ML (Template Matching) |

- |

Table 1 highlights the lack of consistency in evaluation metrics across studies. Various metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, IoU, and detection rate have been computed, which make direct comparisons between studies difficult. This inconsistency can limit the ability to assess how well ML methods are performing on a global scale and across different archaeological contexts. Calculating a unified and consistent metric would enable a standardized comparison, providing deeper insights into the effectiveness and reliability of these methods in archaeological applications.

Another insight is that CNN-based methods, especially with high resolution airborne LiDAR derivatives and for localized studies with detailed archaeological features (for instance, the Netherlands and Mexico [

71,

73,

79,

82]), demonstrate superior detection accuracy and precision compared to traditional ML methods. While higher resolution LiDAR tends to achieve better detection performances, as seen in cases like tar production kilns [

23] and burial mounds [

76], coarser resolutions are used for larger study extents but often result in moderate detection rates. CNN-based methods are the most commonly used, demonstrating versatility by detecting a wide range of archaeological features, including walls [

30,

40,

46,

73,

74], mounds [

20,

55,

57,

77], and Maya structures [

21,

68,

82]. However, ML methods are effective for more straightforward feature types (like canals and linear structures) but less robust for complex features.

Techniques such as filtering and applying enhancement methods on LiDAR data help overcome challenges like vegetation obstruction and erosion effects [

50]. While specific LiDAR guidelines are still evolving (both for data acquisition and for data validation), expertise in landscape analysis remains crucial for accurate assessments, with LiDAR technology enriching our understanding of landscapes over time [

33]. In summary, integrating airborne LiDAR derivatives with ML techniques appears to offer promising avenues for supporting archaeological research and cultural heritage preservation, with various studies showcasing the effectiveness of these approaches across diverse archaeological tasks. Furthermore, collaboration between archaeologists and ML experts may contribute to the refinement of detection methods, and adopting standard evaluation measures can facilitate cross-study comparisons, fostering the development of human-centered ML methods for archaeological feature detection. Finally, archaeological sites remain vulnerable to a range of threats, including environmental factors (such as natural disasters or climate change) and human activities (such as urban development or looting). Despite these challenges, the mentioned studies (

Table 1) provide meaningful insights aiding the interpretation of archaeological sites and planning management strategies to protect and preserve them.

6. Discussion

LiDAR is particularly valuable in archaeological research because of its ability to penetrate dense vegetation, such as forest canopies, and capture detailed measurements of the ground surface. This capability is crucial for discovering unknown archaeological features in heavily vegetated areas which are often challenging to investigate through traditional framework or optical imagery. LiDAR data are often processed into DTMs or other visualization products like hillshades or local relief models, allowing archaeologists to visualize topographical changes that may indicate the presence of archaeological remains such as earthworks, mounds, or ditches. The increasing availability of LiDAR datasets reinforces the potential for automated analysis.

The application of ML/DL to derivatives of aerial LiDAR data represents a transformative shift in archaeology, especially for subtle feature detection over expansive areas. Traditional archaeological methods, including manual analysis of remotely sensed data, are often time consuming and labor intensive. Therefore, the integration of ML/DL techniques offers promising solutions to automate the detection process, enhancing efficiency and potentially reducing costs associated with extensive manual surveys. DL models, particularly CNNs, have demonstrated state-of-the-art performance in object recognition tasks and are well suited for analyzing raster images derived from aerial LiDAR. Various ML/DL approaches such as object detection, segmentation, and classification have been applied to identify diverse archaeological features. Examples include the detection of burial mounds using DL or RF [

33,

42,

55,

57,

76,

84], qanat shaft using CNNs [

1], tar production kilns using U-Net based algorithm [

23], hollow roads [

28], stone walls and farmsteads [

74,

85], and hillforts [

15,

69]. These automated methods can assist archaeologists to quickly identify potential areas of interest across large regions which then can guide subsequent fieldworks and can reduce the need for exhaustive manual analysis. This study showed that ML/DL approaches can achieve high detection rates and accuracy in identifying known features, while also discovering previously unrecorded sites.

Despite the significant potential and early successes, the application of ML/DL to LiDAR derivatives for archaeological detection faces several critical challenges that need careful consideration and ongoing research. First challenge is the availability and preparation of training data. DL models typically require large amounts of data to achieve high accuracy [

1,

71], and such extensive datasets are often scarce in the archaeological field. Insufficient interpretation has been shown to lead to limitations in training experiments [

19]. Analyzing archaeological features in LiDAR derivatives is a task that requires archaeological expertise. This makes the creation of large, well-labeled datasets expensive and time-consuming. Furthermore, the quality and consistency of expert interpretation can vary which potentially introduces bias and error into the training data. This can degrade classifier accuracy. The entire process, from data acquisition to interpretation, involves assumptions and decisions by the operator, which can introduce subjectivity and compromise validity if not properly reported. This underscores the crucial need for standardized documentation, including metadata (data about data) and paradata (documentation of process), to ensure scientific transparency, replicability, and reflexivity. Beyond training data volume, challenges also exist in working with LiDAR data of varying point densities and intrinsic precision. Particularly detecting features in low-density data is difficult. While higher point density LiDAR coverages may become available in the future, researchers currently face issues with available data quality and quantity. Another issue is the lack of publicly available archaeological data due to ethical concerns regarding site protection. Standardized, open-access, and large datasets are lacking, which makes the evaluation and comparison of the performance of different ML/DL models across various archaeological contexts difficult. Fairly comparing different detection methods is challenging because their performance heavily depends on the datasets, metrics, and evaluation methods used. This highlights the need for adopting standard evaluation measures within the archaeological community. There is also a gap in providing efficient and automatic data structuring pipelines for existing datasets that were not originally acquired for heritage detection purposes.

Another significant issue is the prevalence of false positives when applying ML/DL models to LiDAR data. Archaeological features, especially those that are subtle or degraded, often have similar morphologies to natural or artificial non-archaeological shapes in the landscape. This

bird's-eye perspective challenge in LiDAR data means that objects with similar forms (e.g., small mounds, pits) can be difficult for ML models to be distinguished without additional context or validation [

15,

33,

57,

69]. While post-processing validation steps such as analyzing the 3D shape of potential detections can help reduce false positives, a persisting high rate of false positives can require significant effort for subsequent ground truthing. Conversely, false negatives are also a concern. Although, in some applications, maximizing detection (completeness) is prioritized over minimizing false positives (correctness) [

70]. This ensures that no actual features are overlooked. Further investigation can later confirm or reject the findings.

The variability in archaeological feature characteristics and landscape contexts such as the ambiguous boundaries of ancient features [

75] presents further challenges and requires further dedicated studies. Archaeological remains are in diverse sizes, shapes, and levels of preservation. Moreover, their appearance in LiDAR data can be influenced by factors like erosion, vegetation density, and the specific LiDAR processing techniques used. Developing models that can effectively detect this wide range of features across topographically varied landscapes is complex. Model transferability between different geographic regions and archaeological sites is not guaranteed and often requires fine-tuning or retraining [

14,

19]. The necessary resolution and point density of LiDAR data also vary depending on the size and detail of the archaeological features being sought. Lower densities might miss smaller or less distinct features. Deriving suitable raster products (like DTMs or other visualizations) from raw aerial LiDAR involves numerous decisions and algorithms. Therefore, the choice of processing steps can significantly impact the performance of ML/DL models and as a result the visibility of archaeological features. Documenting this complex workflow is crucial for scientific transparency and replicability which is not yet standardized.

Although deep CNN models hold significant potential, they are still not commonly used in detecting archaeological remains [

10]. To our knowledge, there has been limited evaluation of CNNs' object-segmentation capabilities. Most CNN-based object detection techniques in this domain rely on two-stage detectors, such as R-CNNs, Faster R-CNNs, and Mask R-CNNs. While these approaches are robust and often highly accurate, they can face challenges related to slower processing speeds than one-stage detectors. Two-stage CNN detectors first generate region proposals (i.e., areas in the image that might contain objects) and then classify each proposed region and refine its bounding box, while one-stage detectors predict object locations and classes directly in a single step, making them faster but sometimes less accurate [

6,

51,

61]. Additionally, difficulties persist in selecting suitable DL approaches, generating training datasets, and accurately labeling data. Furthermore, adaptable ML methods applied for the segmentation of unstructured 3D data are still under discussion and are not yet consolidated [

19]. Three notable contributions include the Multi-Level Multi-Resolution (MLMR) SS approach, which utilizes RF algorithms for classification [

84], the implementation of the PointConv architecture for high-accuracy classification of 3D point clouds [

3], and the application of DL on 3D airborne LiDAR data for SS and object detection of historical defensive architectures [

19]. These approaches can offer innovative solutions for analyzing LiDAR-generated datasets and detecting archaeological structures with improved accuracy and efficiency. However, most existing DL approaches for point clouds are primarily focused on other fields, like robotics, autonomous driving, and indoor modeling [

19]. Adapting these methods for use in cultural heritage and landscape contexts requires significant modifications. Model generalization and adaptability are in fact challenging when applying systems developed in one region or for one type of feature to areas with different site typologies and landscapes, and normally requiring fine-tuning [

69].

Integrating information from various sensors, such as combining airborne LiDAR data with photogrammetric data [

10], aerial imagery, multispectral/hyperspectral imaging, geophysical surveys, and ground-based LiDAR scans [

86,

87,

88] or utilizing multispectral LiDAR [

67,

89], offers the opportunity to overcome the limitations of single data sources by extracting richer and more detailed information about the potential archaeological features. However, challenges remain in effectively integrating these diverse datasets considering variations in resolution, penetration, texture, color, accuracy, and the dynamic nature of the environment. Therefore, these techniques are not commonly used, and there is limited evidence of their effectively detecting hidden remains. Moreover, the development of hybrid ML/DL models that fuse predictions from different models, combine DL with traditional methods, or integrate ML/DL with external knowledge sources or processes [

75,

78] could further enhance the accuracy and interpretability of archaeological feature detection algorithms. The application of these hybrid approaches can lead to high detection and segmentation performance even with relatively small training datasets. It could address a common limitation in archaeological contexts where large training datasets are scarce. By combining the strengths of different methods, these hybrid models can potentially achieve higher accuracy and reduce false positives compared to using a single method. However, challenges exist. Implementing such combined approaches can require substantial computational resources and processing time [

69]. While hybrid detection methods can be fast, the process often requires significant human expertise for creating and refining training datasets, validating results, and interpreting findings, especially when dealing with complex or heterogeneous archaeological features [

23]. Also, managing various data types introduces storage challenges. Important practical aspects could be excluding negative zones (i.e., areas where archaeological information cannot be obtained, such as built-up areas or areas with insufficient data quality) [

15], and establishing specific arrangements for the long-term storage and archiving of digital data products, considering the necessary storage space [

23]. Therefore, their successful implementation needs careful consideration of data requirements, computational resources, and the critical role of human expertise in the workflow.

Last but not least, the successful implementation of ML/DL in archaeology requires close interdisciplinary collaboration and knowledge integration between archaeologists, computer scientists, and remote sensing experts. Applying complex computer algorithms remains uncommon for many archaeologists, because it often requires the expertise of computer science specialists. Additionally, a

barrier of meaning [

11] exists which represents the gap between the expert archaeologist's knowledge and the knowledge learned by the machine. To address this, it is fundamental to enhance the involvement of archaeologists in the learning process. This enables them to contribute their expertise and to provide domain knowledge to the machine [

71]. Archaeologists provide the expertise necessary for identifying and interpreting potential features, defining target classes for ML/DL models, and validating results through ground truthing. Computer scientists develop and refine the ML/DL algorithms. And, remote sensing specialists handle data acquisition and processing. Integrating archaeological knowledge into the ML/DL workflow, such as using location-based ranking or incorporating specific archaeological object patterns, can improve model performance and reduce false positives [

4,

33,

57]. Moreover, international collaboration and establishing standardized datasets [

71] are essential for facilitating the evaluation of ML and DL models in feature detection and classification within the archaeological field. By leveraging technological innovations and fostering collaboration among archaeological teams, we can accelerate the pace and improve the quality of archaeological investigations, ultimately contributing to a deeper understanding of ancient civilizations and the preservation of cultural heritage.

Future research directions may focus on addressing the identified challenges. Finding ways to deal with the lack of labeled training data is very important. This could be done using methods like active learning, weakly supervised learning, or more effective data augmentation techniques such as generating synthetic point cloud data and 3D bounding box labels [

19]. Furthermore, creating and sharing standardized, open-access datasets with high-quality annotations and ground truth validation would significantly facilitate the development and comparison of ML/DL models. Moreover, further investigation is needed to understand: how different LiDAR processing techniques impact the visibility of various archaeological features? how to optimize these techniques for automated detection? Developing transferable methodological approaches that can adapt to varying primary data densities, particularly addressing low-density applications, is needed. It is also important to develop more robust models that can deal with the inherent differences in archaeological features, can work well across various landscapes and data types, are able to leverage higher point density LiDAR data as it becomes available and can incorporate new data sources like LiDAR intensity values. Besides, exploring the fusion of LiDAR with other remote sensing data, such as multispectral imagery or photogrammetry, and exploring the potential opportunities of hyperspectral LiDAR may provide additional information to improve detection accuracy and reduce false positives. Therefore, future work should include ablation studies to quantitatively assess how much each individual data source (or the combination of them) contributes to the model's performance. This helps prove whether using multiple data sources actually improves the results. Likewise, refining post-processing validation methods such as using 3D information from the point cloud or incorporating spatial context analysis could help filter out non-archaeological features. Finally, fostering interdisciplinary and international collaboration and knowledge integration is crucial. Collaboration among surveyors, archaeologists, and software engineers for method development is encouraged. Moreover, future research should also place site findings within their broader regional and temporal context [

22] and consider investigating archaeological features that extend over national borders by combining LiDAR data and AI.

7. Conclusion

Our work serves as a valuable bridge between traditionally separate disciplines by demonstrating how AI-driven object detection using CNNs and LiDAR can be effectively applied to archaeological research. By clearly mentioning underutilized technical operations, such as direct 3D point cloud analysis, broad-scale model generalization, and human-AI collaborative workflow, this study promotes meaningful collaboration across archaeology, geosciences/RS, computer science/engineering, heritage management, and public engagement. It can support the growing interdisciplinary momentum in landscape archaeology and can contribute to the development of sustainable, scalable, and scientifically robust methodologies for both academic research and heritage practices.

Integrating airborne LiDAR derivatives with ML techniques represents a notable advancement in archaeological research. The combination of LiDAR's high-resolution terrain mapping capabilities with the automation capabilities of ML algorithms has the potential to enhance current methodologies, enabling more efficient and systematic detection of hidden archaeological landscapes and structures.

Through this literature review, we have explored the diverse applications of ML-based approaches in archaeological feature detection, ranging from identifying ancient settlements to detecting burial mounds and urban complexes. These studies demonstrate the potential of ML techniques, particularly DL models, in augmenting traditional archaeological methods and facilitating a deeper understanding of past civilizations.

Despite the significant progress, several challenges and opportunities for future research remain. Addressing issues such as data accessibility, algorithm interpretability, and interdisciplinary collaboration will be essential for advancing the field further. Moreover, exploring DL-based processes for classifying 3D point cloud datasets and establishing standardized evaluation measures are critical steps toward enhancing the reliability and applicability of ML models in archaeological research.

Ultimately, by drawing on technological innovations and encouraging collaboration among interdisciplinary teams, there is potential to enhance the pace and quality of archaeological investigations. Continued exploration and innovation may help deepen our understanding of ancient civilizations, support cultural heritage preservation, and inspire future generations to engage with the rich diversity of human history.