1. Introduction

Cellular Telecommunication Networks have been a huge part of public and private communications in the last few decades. The current standard for these networks is the Fifth-Generation (5G) networks, dealing with constantly changing patterns in user traffic as well as the different requirements of each user and application connected to the network. The huge amount of data in extremely dense networks causes congestion [

1]. This creates a need to optimize resource allocation in such networks to ensure Quality of Service (QoS). Resource allocation in 5G networks is a field with a significant research interest, while the capability to predict user traffic in such networks can assist any system of the former.

Machine and Deep Learning (ML/DL) have been proven useful for optimizing resource allocation and user traffic in 5G networks, along with tasks such as energy efficiency, network accuracy, and latency [

2,

3]. However, this requires the training of such algorithms through the use of large accurate datasets gathered from currently active 5G networks. The advantage of Machine Learning, when provided with quality large-scale data, is that it can provide fast and high-quality results with minimal loss of effectiveness.

This paper presents a novel approach for predicting user traffic and using these predictions to aid with the allocation of the users to Base Stations in a 5G environment. Thus, the resource allocation of the network can be performed in a proactive way that can be adapted in real-time to changing network conditions. The main strength of our framework lies in the ability to approximate long-term trends in time-series data, an open research question in the 5G communication field. Furthermore, the ML models comprising our framework offer a good balance between performance and usage of computational resources.

2. Related Work

2.1. Data-Driven User Resource Allocation and Traffic Prediction in 5G Networks

In recent years, data-driven methods for user resource allocation in 5G networks [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10] have started to appear more often in research than mathematical approaches [

11,

12,

13], with a variety of Machine Learning architectures being employed for this task.

Deep Neural networks have been utilized in [

7] and [

9] for user allocation in Non-Orthogonal Multiple Access (NOMA) 5G Networks and to minimize system delay in 5G Networks, respectively. In contrast, traditional Machine Learning techniques based on decision trees and K-means clustering show promising results over 5G resource allocation in [

14]. CNN-based architectures have also been employed to optimize user allocation [

5,

8]. In [

5], the problem of resource allocation in small- and large-scale base stations comes down to an image segmentation task, whereas in [

8], small-scale channel information, such as the status of the channel, is exploited to reduce time consumption. Furthermore, Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) demonstrate significant efficacy in facilitating 5G user allocation tasks. For example, in [

6], a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network, along with a Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) model combined with a convex optimization algorithm, was utilized for dynamically allocating user and power resources in 5G TV broadcasting services. Similarly, in [

10], a DRL algorithm was introduced to perform energy-efficient user allocation in edge computing and the Industrial Internet of Things in 5G networks, while an RL-based method for dynamic resource allocation to improve QoS of end-users, was proposed in [

4].

Akin to user resource allocation works, approaches to optimize 5G user traffic prediction use deep and machine learning methods to tackle the increasing demand for wireless access. Therefore, approaches span from traditional Machine Learning approaches [

15] and Deep Learning approaches such as RNNs (e.g., LSTMs [

16,

17,

18]) to leverage the temporal dependencies in user traffic data, to state-of-the-art Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) [

19,

20], which exploit spatiotemporal features (i.e., spatial data refer to base stations’ topology) to achieve accurate predictions.

Traffic prediction can also be utilized to facilitate user resource allocation [

6,

9]. For instance, in [

6], an LSTM network performed traffic prediction on multicast services, which was utilized for pre-resource allocation. Moreover, the authors of the work in [

21] propose a deep learning methodology to enable User-centric end-to-end Radio Access Network slicing.

In this study, we detail a framework that performs user traffic prediction that entails resource allocation by employing a fully data-driven approach based on sophisticated ML models. A problem underexplored in the aforementioned works, our framework explores the prediction of long-term trends in user data, while employing computationally inexpensive ML models. Moreover, our framework can also be utilized for dynamic network slicing, considering the impact of environmental factors and user behavior during the learning process of our models.

3. Datasets & Data Preprocessing

In this paper, we present a framework that has two main tasks, that of user traffic prediction for 5G networks and that of user allocation in 5G networks incorporating the predictions of the previous module. Our system consists of two modules: i) a Recurrent Neural Network or a Transformer-based model for user traffic prediction and ii) a Convolutional Neural Network model for user resource allocation. There is also an adaptive approach to handle the results of user traffic predictions to assist the user allocation module in its task based on future highs and lows of traffic at base stations.

The data used to train and evaluate the models were obtained from two distinct sources, one for each model. The user traffic prediction dataset consists of traffic collected from a 5G mobile terminal in a dense urban setting[

22]. The user allocation dataset is a synthetic dataset called DeepMIMO[

23] created with the express purpose of being used by large data models such as neural networks.

3.1. 5G Traffic Dataset

We utilized the 5G Traffic dataset presented in [

22] for the training of our user traffic prediction module. User traffic was collected via a Samsung Galaxy A90 5G mobile terminal in South Korea across various applications such as live streaming (e.g., Naver Now), stored streaming (e.g., YouTube, Netflix), video conferencing (e.g., Zoom), metaverse (e.g., Roblox), online gaming (e.g., Battlegrounds) and game streaming (e.g., GeForce Now) platforms. Thus, the dataset contains video traffic that imposes significant strain on 5G networks. More specifically, the dataset includes the time when the user started the 5G connection, their Internet Protocol (IP), the IP of the destination (the server to which the user is connected), the protocol used for the connection, the duration, and information regarding the connection. The dataset contains video traffic data with a total length of 328 hours, being collected over a period of 6 months (from May to October 2022).

To preprocess the 5G dataset, we first store the provided CSV files in an SQL database. The initial step is an optimized indexing and batch query execution, reducing memory requirements during the learning stages of the model. Due to the temporal indexing, the timeseries can be optimally segregated, which significantly improves performance in the training and testing stages. This use of databases significantly reduces the preprocessing time and assists with the batch processing of very large datasets. The data change from the initial form of user connection length entries to network traffic in the form of user traffic per time step. The data from this table were used to train our 5G traffic prediction module.

The preprocessing operations that we used on the dataset are typical preprocessing operations suitable for RNN models that we fine-tuned to obtain better results. The first operation is a min-max normalization to the range of 0 to 1. The next operation is a sliding window of size 10 to produce a rolling mean of the values with the aim of capturing the feature of local mean network traffic. A rolling standard deviation is used to help with local value volatility. Moreover a first-order difference is used to help with extracting the "momentum" of the values within the rolling window. Finally the raw values as recorded are also used without the previous preprocessing steps as the core dataset of the input in the network. The experiments were done with an input of 120 values, each representing the user traffic at the start of a given clock time step and the prediction outputs the next 60 time steps as 60 values one for each time step in the future.

3.2. Deep MIMO Dataset

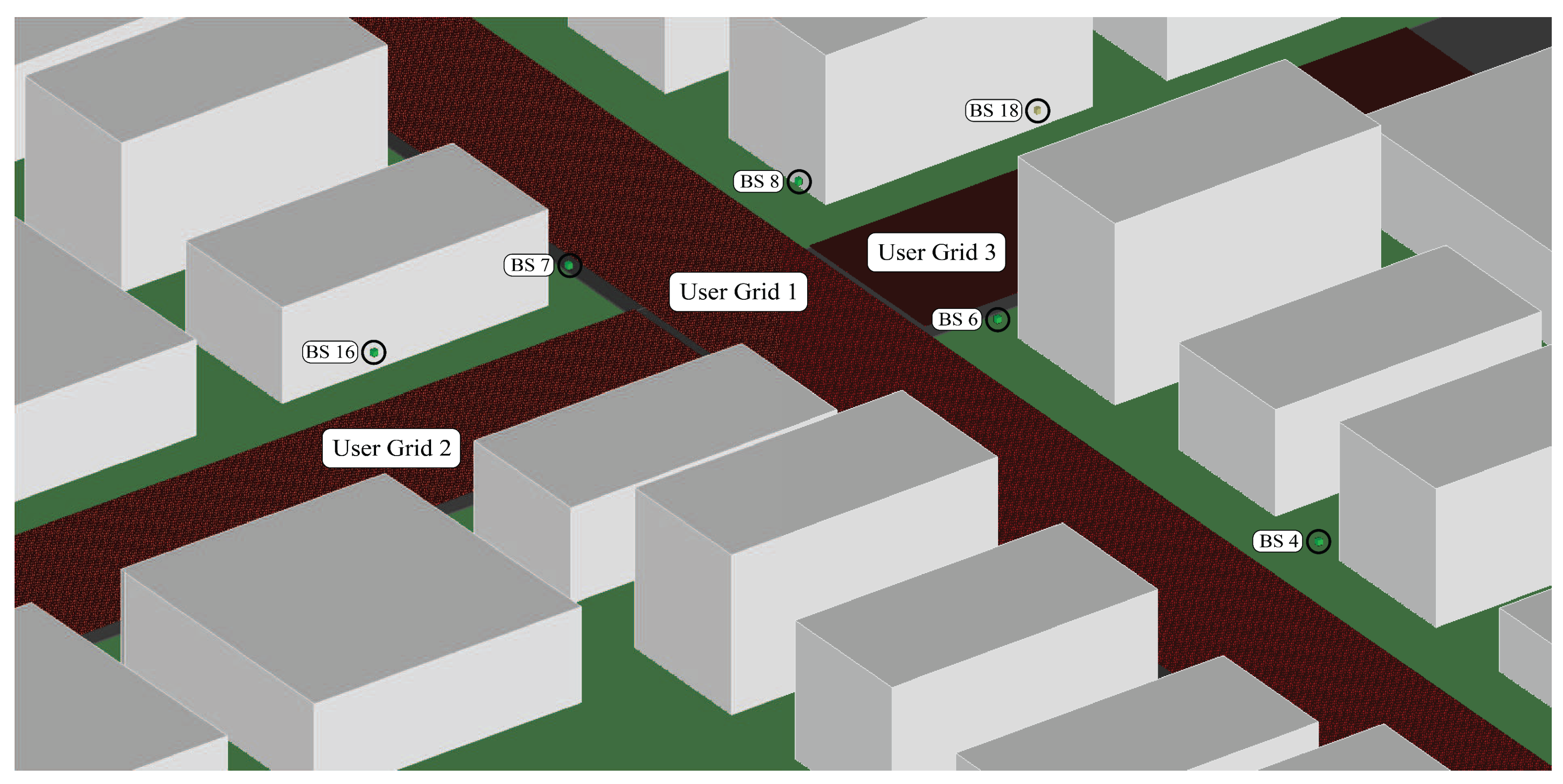

To train our user resource allocation module, we leveraged a synthetic dataset generated via DeepMIMO [

23], a versatile deep learning dataset specifically designed for millimeter wave and massive Multiple Input Multiple Output (MIMO) systems. DeepMIMO offers a diverse range of scenarios enriched with three-dimensional geometries, realistic user distributions, and detailed wireless network demands. DeepMIMO utilizes precise 3D ray-tracing simulations, and accommodates a myriad of scenarios tailored to 5G wireless models, thus facilitating the creation of extensive MIMO datasets. For the evaluation of our systems, we employed an outdoor scenario

1 set within a city block, populated with users as illustrated in

Figure 1.

This scenario includes 18 base stations with a height of 6 meters, with each station being an isotropic antenna array element. The main street contains 12 base stations evenly placed on either side of the road. Consecutive stations are separated by 52 meters. The remaining base stations are allocated along the secondary street, which runs perpendicular to the main street (as illustrated in

Figure 1). The users within the scenario are organized into three uniform grids, culminating in a total user count of 1,184,923. Overall, this dataset is used to perform user resource allocation in 18 stations.

However, our resource allocation module was trained over different versions of this scenario, meaning that not all users and base stations were selected for each training epoch.

The ground-truth dataset for our user allocation model based on the Deep MIMO scenarios contains the following information: i) the spatial position of users, ii) the spatial position of base stations, iii) the specific scenario from which the data are derived (that implies a 3D geometry to be "learned" by the user allocation model), and iv) the allocation of each user with a corresponding base station. As for the dataset preprocessing procedure, linear normalization was applied, along with the implementation of an outlier detection and trimming algorithm in Python.

4. Methodology

Our framework consists of two modules, the user allocation and the traffic prediction one. Each of our models can be either deployed separately or as an end-to-end framework, where user traffic prediction can facilitate resource allocation in 5G environments.

4.1. User Traffic Prediction Module

For the user traffic prediction module, we use two different architectures; a Recurrent Neural Network, namely a Long Short-Term Memory model, and a hybrid model consisting of a Transformer and a Temporal Convolutional Network (TCN) model. These two architectures produce different in nature but similar in performance results.

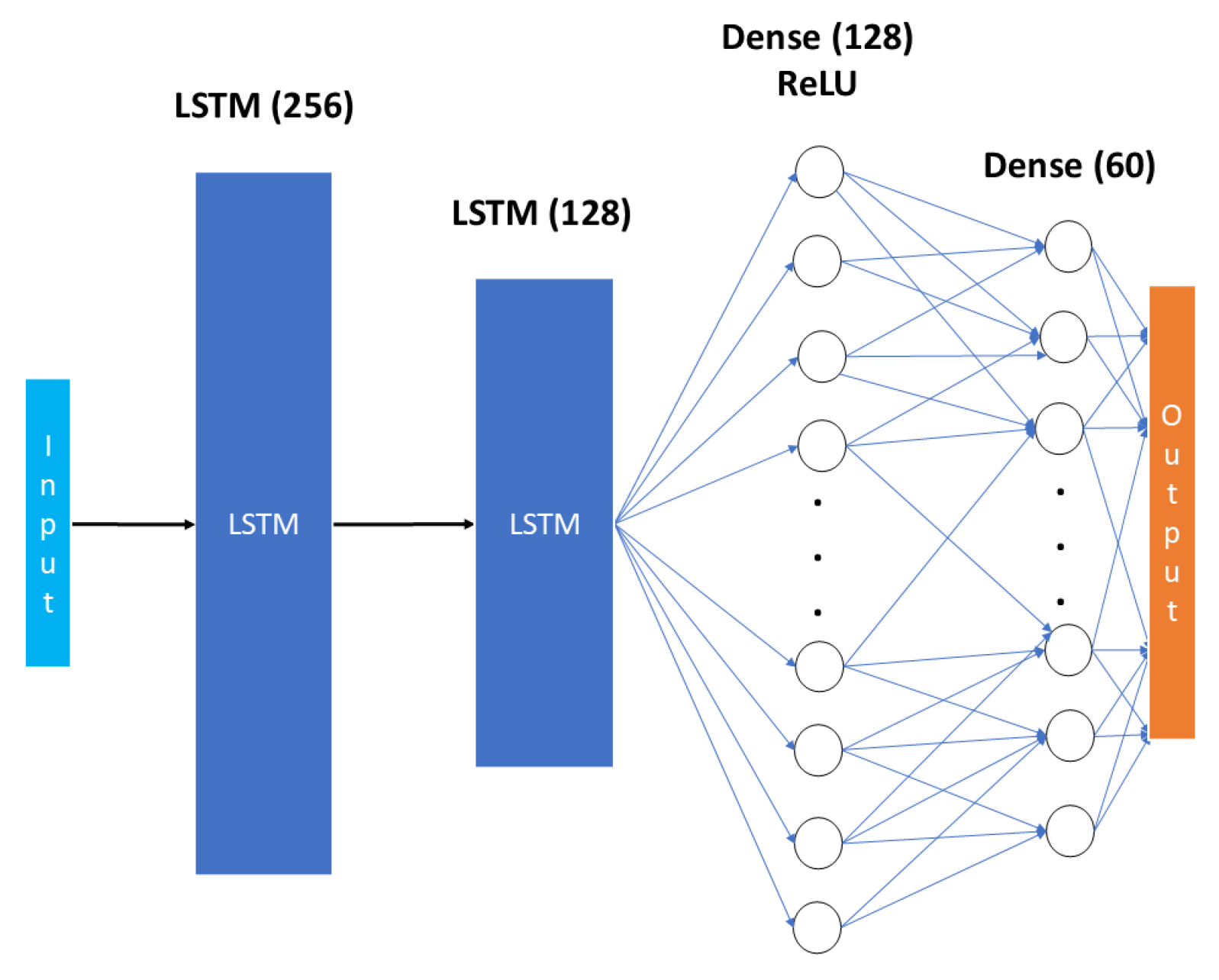

4.1.1. Long Short Term Memory Variant

Long Short-Term Memory networks can effectively capture temporal relationships in time-series data, which is essential for prediction problems, as the one explored in this work. As depicted in

Figure 2, the Long Short-Term Memory Neural Network is comprised of two LSTM layers, one with 256 units that does the initial hierarchical feature extraction and a second with 128 units that captures the higher-level temporal patterns. These layers are followed by a Dense (fully-connected) layer of 128 units with an activation Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) activation layer. The final layer is again a fully connected output layer of 60 units representing the next 60 predicted timesteps. The first LSTM layer is used to identify immediate sequential relationships such as traffic fluctuations and seasonal variations. The second LSTM layer then operates on those relationships identifying patterns and higher order temporal relations. [

24]. This hierarchical process allows the architecture to capture more than one order of temporal patterns which is particularly useful in traffic prediction where both immediate changes and long-term patterns can be found in the data. The input is a set of 120 timesteps with 5 features each; i) the actual value of user traffic of that timestep, ii) the rolling mean of the last 10 timesteps, iii) a rolling standard deviation of the last 10 timesteps, iv) a first-order difference that represents the momentum of the user traffic, and finally v) the percentage change of the current timestep compared to the first of the rolling window.

A custom solution that combines the loss from Mean Squared Error, a Trend Direction loss calculation to assist the consistency of the directionality of the time-series, and a Volatility-based loss to reduce patterns of statistical dispersion, was implemented as the loss function. This combined loss strategy improves consistency by taking into account the volatility of the data as well as the magnitude and penalizes model parameters that would just optimize for one or the other. This way we overcome the natural limitation of optimizing for magnitude prediction by just using Mean Squared Error. Adam[

25] with decay rate and early stopping was used as the optimizer to exploit the adaptive learning mechanism in the root mean squared error propagation method and the momentum mechanism employed in the gradient descent process.

4.1.2. Transformer and Temporal Convolutional Network Variant

The Transformer Neural Network is a Hybrid model consisting of a Transformer and a Temporal Convolutional Network model. The transformer component is effective at capturing long-term temporal dependencies and seasonal patterns [

26] due to its self-attention mechanism, which enables focusing on crucial information regardless of its position in the time-series data. Hence, the transformer processes all time steps of a time-series sequence simultaneously, unlike traditional RNN-based models, which process time-series data sequentially. On the contrary, the Temporal Convolutional Network is aimed at extracting local short-term patterns [

27], since convolutions are performed on windows of data.The TCN model is comprised of 4 attention heads and a 64-dimensional key space. Furthermore, the model also incorporates a normalization layer and a 256-unit feed-forward layer with a ReLU activation function for stability during training. The encoding used is a Positional Encoding so that the sequence of temporal information is retained. Finally, 4 sequential transformer blocks for hierarchical feature extraction, are added. The TCN model is comprised of Dilated Convolutions with Causal Padding and dilation rates that are exponentially increasing. This ensures that only past information is used for predictions. Moreover, it consists of Residual Connections for gradient flow and two 1D Convolutional Layers each with its own ReLU activation function. The integration between the two models is achieved with 2 fully connected layers of 128 and 64 units each, followed by a Rectified Linear Unit activation layer and an output of 60 for the 60 predicted timesteps. In the output layer, an average pooling is applied.

For this network, the same loss function and optimizer (Adam [

25]) that were used to train our LSTM model, were utilized.

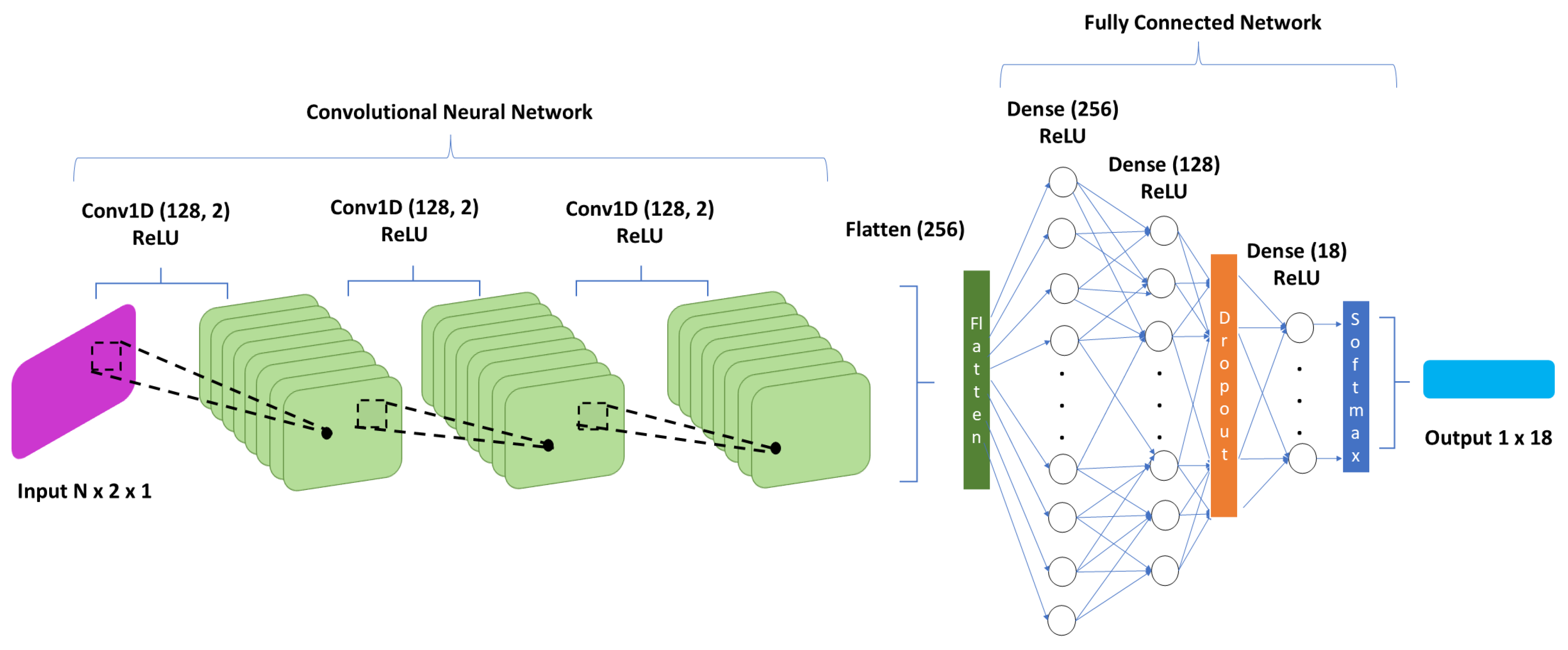

4.2. User Allocation Module

The user allocation module is influenced by the model presented in [

28]. As depicted in

Figure 3, we created a CNN-based model consisting of three convolutional 128-unit layers with ReLU activations and three Dense layers with widths of 256, 128, and 18, respectively. CNNs succeed in extracting spatial features from geospatial data such as base station positions, as well as processing multi-dimensional data. The input of this model is the geographical longitude and latitude of each user as derived from the DeepMIMO dataset, while the output is an 18 one-hot encoded output, corresponding to 18 stations where the users are allocated. This model was trained over a maximum of 1000 epochs with a batch size of 32. An early stopping mechanism with a patience of 25 was employed, thus, the 1000 epochs were never reached. Adam [

25] was selected as the optimizer with a learning rate of

to improve the convergence of training and reduce the risk of gradient descent being stuck in local minima. The way this is achieved is through the adaptive learning mechanism in the root mean squared error propagation method and the momentum mechanism employed in the gradient descent process [

25]. Multi-class cross-entropy [

29] was employed as the loss function for this multi-class task. The above architecture and hyperparameters are optimal as arises from the analysis carried out in [

28].

In order to allocate users to base stations based on user traffic predictions, we rank the base stations based on their perceived future traffic. Base stations with very high traffic have a virtual increase in user distance to that base station relevant to the intensity of the predicted high traffic. That distance is analogous to the percentage of total base station allocated users compared to the user capacity of that base station. So if we would want the users of a base station to fall by some percentage point, we would virtually position them relatively that much farther away from the high traffic station than they are. Hence, user traffic predictions are used in an adjusted virtual position mechanism to the user allocation module. With this approach the models for allocating users take into account the future traffic of base stations.

5. Results

The results presented in this section come from two datasets that are detailed in sub

Section 3. The machine used for training and running the models was an AMD Ryzen 5600X 6-Core 3.7GHz CPU with a GeForce RTX 3060 GPU with 12GB memory. The models show an increase in accuracy and capacity to digest larger datasets as the hardware scales up, but at a diminished rate the more it scales. As discussed in [

30] artificial neural networks of increased size and complexity yield stronger results but seem to be governed by laws of scaling that mandate diminishing returns in the logarithmic scale relevant to the increase in computation.

The metrics utilized to assess the performance of our framework are the Absolute Error metric and its percentage. By performing evaluations on variations of our selected models, we account for ablation studies.

5.1. User Traffic Prediction Module Results

The user traffic prediction dataset is processed into a time-series of user traffic on the network per 1 time step. In this way, features and trends in time can be extracted through machine learning, and make future predictions.

5.1.1. Long Short Term Memory Results

The architecture described in

Section 4.1.1 resulted from trials done with different configurations of Long Short-Term Memory-based architectures. The models were trained to a maximum of 100 epochs with a mechanism for early stopping (i.e., the 100 epochs were usually not reached due to early stopping).

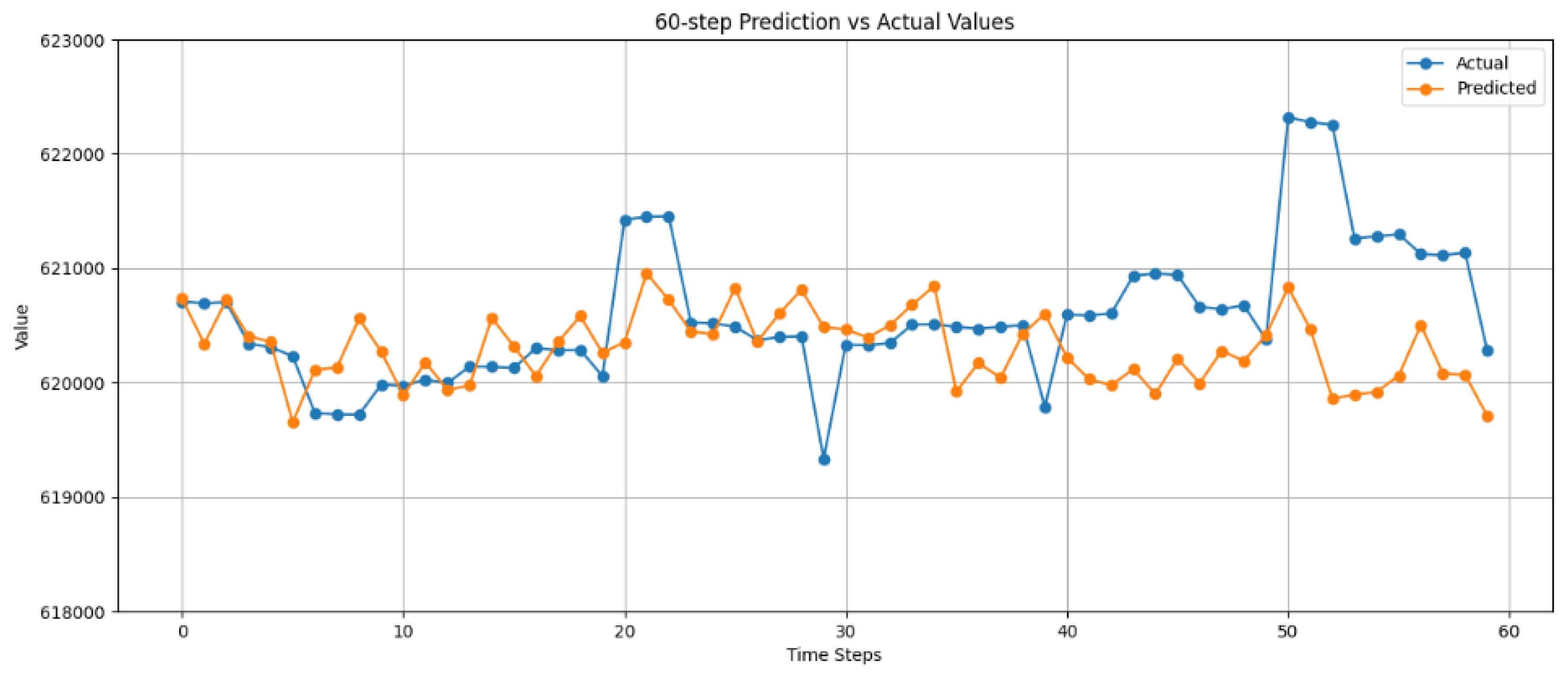

In

Table 1, the tests carried out to select the number of LSTM layers, which are the core part of any LSTM model, are recorded. The results show that a 2-layer LSTM is better and that seems to align with fundamental principles of deep learning regarding the complexity and bias-variance trade-off of models [

31]. An observation of the results is that the 1-layer LSTM is slightly underfitting and more than 2 layers are slightly overfitting the dataset with the current hardware.

In

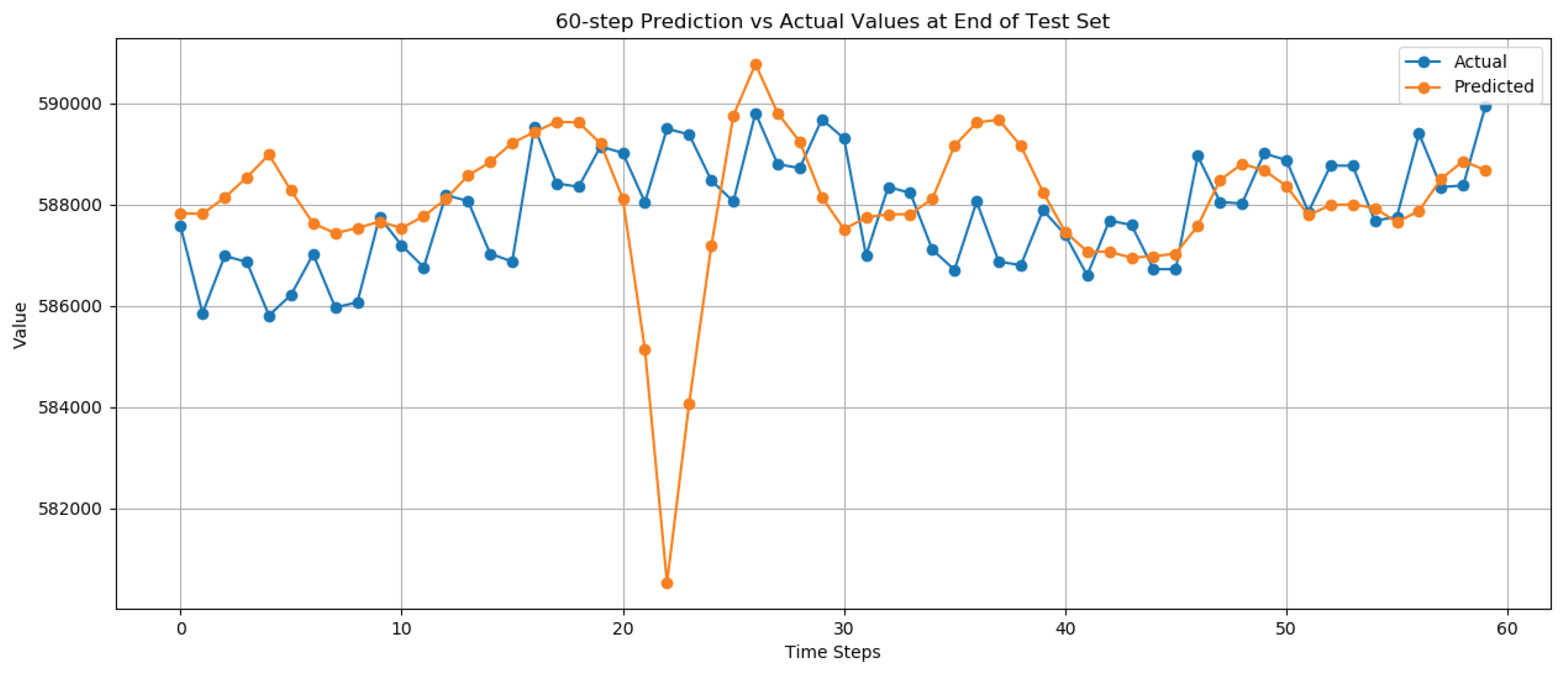

Figure 4, the predicted next 60 time steps of user traffic of an instance of the dataset, is depicted. As shown in

Figure 4, the first few time steps have very high accuracy and the further the predictions move from these time steps, the chance of inaccurate predictions increases, as can be seen in the time step 50 and thereafter. Though the general trend of the traffic seems to be predicted correctly, the actual value of the users is miscalculated. Another interesting detail is that some 1-time step spikes in traffic are usually not predicted as they are not part of some trend and seem to be accidents in the general trend of the traffic caused by some external factor.

The results are satisfactory and show a very promising inclination to improve with just simple hardware upgrades, as the dataset is large enough to support stronger and larger training trials. More specifically, the error in predictions is significantly less than and the absolute error being at about 1000 users is a great result. The latter might suggest the ability to predict even further in time with insignificant inaccuracies.

5.1.2. Transformer and Temporal Convolutional Network Results

The architecture chosen for the Transformer and Temporal Convolutional Network hybrid approach resulted from trials done with both Transformer models, Temporal Convolutional Networks, and each one separately. Just as in the case of our LSTM model, these models were also trained to a maximum of 100 epochs with a mechanism for early stopping, meaning that 100 epochs were not reached during the learning process.

Table 2 illustrates the calculated error of the Transformer and Temporal Convolutional Network hybrid approach. Even though the error seems to be larger than the one of our LSTM model, there is a qualitative distinction that makes the hybrid approach more promising. That distinction is that the latter architecture captures better the directionality and trends of the time-series of the user traffic.

In

Figure 5 we can see the predicted next 60 time steps of user traffic of an instance of the dataset. This

Figure 5 shows that the first time steps are not accurately predicted as it was with the Long Short-Term Memory model. The main advantage of this approach is the trends that are being predicted as it can predict trends as deep as the predicted 40

th to 60

th time step as seen in

Figure 5. These trend captures can be seen across

Figure 5 for instance in time steps 7 to 18 and time steps 24 to 30. This is a very promising result due to the fact that if the erroneous artifacts are eliminated, the results can become by far superior to the Long Short Term Memory model. An example of the erroneous artifacts would be the one in time step 20 to 24 of the graph in

Figure 5.

5.2. User Allocation Module Results

The architecture of the model used for user allocation is the one inspired by [

28]. The Convolutional Neural Network model was trained to a maximum of 1000 epochs with a mechanism for early stopping.

In

Table 3 the performance of the Convolutional Neural Network model with and without using the predictions of the user traffic prediction models, is illustrated. Multi-class cross-entropy was utilized as the loss of this model as mentioned in

Section 4.2. It is observed that by using the adjusted virtual position mechanism (i.e., user prediction preceding resource allocation) the results become more accurate in allocating users to base stations as discussed in [

28].

6. Evaluation and Discussion

The approach shows very promising results in both predicting user traffic and allocating to base stations based on the predicted traffic. The combination of machine learning-based traffic prediction and our adaptive user allocation strategy shows the potential of the model to be applied to operational 5G networks, with the aim to improve the QoS and reduce network congestion in densely populated urban centers.

The capability to combine the capture of temporal features in user traffic and spatial features from our previous work in user allocation is a significant step towards a holistic approach in data-driven resource allocation for 5G networks. Moreover, the ability to anticipate network demands through the user traffic prediction module can also be used separately with all user allocation systems that can integrate future predictive resource demand into their strategy. The most significant advantage of the framework is the incorporation of historical trends in real-time data, which creates the ability to quickly adapt to changing conditions of the network.

Capturing long-term trends in user traffic data is underexplored in current literature with most works focusing in short-range predictions [

16] or predictions depending on the previous frame [

17].

In [

19], the authors present their Graph Neural Network approach and other frameworks for user traffic prediction in the literature comparing the results of their datasets. They report a performance of at best

accuracy, while previous methods go up to

. The dataset is of cellular network traffic in the city of Milan and seems to be more sensitive to data volatility. This could be due to the difference in network requirements of the users and the fact that it is just cellular network traffic instead of complete internet traffic, that the 5G Traffic dataset consists of. Moreover, the LSTM presented in [

6] indicates a better performance up to

accuracy for long-term user traffic prediction. This method shows a performance very similar to ours. Our method shows more than

accuracy, but this is due to the dense nature of the data stemming from a very large dataset.

The main limitation of the system is its dataset. As with most data-oriented approaches, the data is the most important part of any such system. The data used to train the models is gathered in dense urban environments, which creates strong statistical features through the very large number of users and common patterns between them. So, a question arises about the efficiency of the system in more sparse rural environments. Another limitation is the hardware used to run and train the models of the system, as the main hardware used was an office machine which can be said to be a rather weak processing unit to calculate the kind of operations that neural networks do. This limitation though can be said to be a strength of the approach as it shows very strong results despite the weak processing power.

In terms of results, our traffic prediction model tends to approximate the long-term trends in data (e.g., in the span of 60 time steps), however lacking in point-by-point predictions. To address this issue, more experiments in large datasets and employing larger Transformer-TCN models are to be conducted. The latter entails more computational resources. One more limitation involves the training of the user allocation module on synthetic data, which may not capture the entirety of real-world complexities.

In future work, we would like to address the main limitation being the data. We aim to train our system with more diverse and larger real-world datasets hoping for both better performance and accurate predictions into further time windows. This aim though would also need stronger hardware and a more sophisticated approach to absorb the amount of data that we aim for. Another goal is the deployment of this system in an active 5G network to test its capabilities with real-time data so we can study and understand the challenges of user traffic prediction in a live 5G environment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.K., I.L., D.T., K.S., A.G. and C.B.; methodology, I.K., I.L. and D.T.; investigation, I.K., I.L. and D.T.; data curation, I.K., I.L. and D.T.; writing—original draft preparation, I.K., I.L. and D.T.; writing—review and editing, I.K., I.L., D.T., K.S., A.G. and C.B.; supervision, K.S., A.G. and C.B.; project administration, K.S., A.G. and C.B.; funding acquisition, K.S., A.G. and C.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research project was supported by the Hellenic Foundation for Research and Innovation (H.F.R.I.) under the “2nd Call for H.F.R.I. Research Projects to support Faculty Members & Researchers” (Project Number: 02440).

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 5G |

Fifth-Generation |

| CNN |

Convolutional Neural Network |

| DL |

Deep Learning |

| DRL |

Deep Reinforcement Learning |

| GNN |

Graph Neural Network |

| IP |

Internet Protocol |

| LSTM |

Long Short-Term Memory Network |

| MAE |

Mean Absolute Error |

| MIMO |

Multiple Input Multiple Output |

| ML |

Machine Learning |

| NOMA |

Non-Orthogonal Multiple Access |

| QoS |

Quality of Service |

| ReLU |

Rectified Linear Unit |

| RNN |

Recurrent Neural Networks |

| TCN |

Temporal Convolutional Network |

References

- Umar, A.; Khalid, Z.; Ali, M.; Abazeed, M.; Alqahtani, A.; Ullah, R.; Safdar, H. A Review on Congestion Mitigation Techniques in Ultra-Dense Wireless Sensor Networks: State-of-the-Art Future Emerging Artificial Intelligence-Based Solutions. Applied Sciences 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowdur, T.P.; Doorgakant, B. A review of machine learning techniques for enhanced energy efficient 5G and 6G communications. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2023, 122, 106032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Pérez, D.; Domenico, A.D.; Piovesan, N.; Bao, H.; Xinli, G.; Qitao, S.; Debbah, M. A Survey on 5G Radio Access Network Energy Efficiency: Massive MIMO, Lean Carrier Design, Sleep Modes, and Machine Learning. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2021, 24, 653–697. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.; Kim, S.; Lim, H. Reinforcement Learning Based Resource Management for Network Slicing. Applied Sciences 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xiong, L.; Yu, J. Deep learning based user association in heterogeneous wireless networks. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 197439–197447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.; Zhou, F.; Zhang, X.; Qiu, X.; Kadoch, M.; Cheriet, M. Deep learning-based resource allocation for 5G broadband TV service. IEEE Transactions on Broadcasting 2020, 66, 800–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumaresan, S.P.; Tan, C.K.; Ng, Y.H. Deep neural network (DNN) for efficient user clustering and power allocation in downlink non-orthogonal multiple access (NOMA) 5G networks. Symmetry 2021, 13, 1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Gao, Y.; Li, Y.; Hou, M.; Tang, W.; Cheng, S.; Li, X.; Sun, Y. Deep learning based cooperative resource allocation in 5G wireless networks. Mobile Networks and Applications 2022, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamba, R.; Bhandari, R.; Asha, A.; Bist, A. An Optimal Resource Allocation in 5G Environment Using Novel Deep Learning Approach. Journal of Mobile Multimedia 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S. Energy efficient resource allocation method for 5G access network based on reinforcement learning algorithm. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments 2023, 56, 103020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouras, C.; Caragiannis, I.; Gkamas, A.; Protopapas, N.; Sardelis, T.; Sgarbas, K. State of the Art Analysis of Resource Allocation Techniques in 5G MIMO Networks. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Information Networking (ICOIN); 2023; pp. 632–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouras, C.; Diasakos, D.; Gkamas, A.; Kokkinos, V.; Pouyioutas, P.; Prodromos, N. Evaluation of User Allocation Techniques in Massive MIMO 5G Networks. In Proceedings of the 2023 10th International Conference on Wireless Networks and Mobile Communications (WINCOM). IEEE; 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.S.; Lin, C.H.R.; Hu, Y.C. Joint resource allocation, user association, and power control for 5G LTE-based heterogeneous networks. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 122654–122672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouras, C.; Kalogeropoulos, R. User Allocation in 5G Networks Using Machine Learning Methods for Clustering. In Proceedings of the Advanced Information Networking and Applications; Cham; Barolli, L., Woungang, I., Enokido, T., Eds.; 2021; pp. 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Selvamanju, E.; Shalini, V.B. Machine learning based mobile data traffic prediction in 5G cellular networks. In Proceedings of the 2021 5th international conference on electronics, communication and aerospace technology (ICECA). IEEE; 2021; pp. 1318–1324. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Z. 5G traffic prediction based on deep learning. Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience 2022, 2022, 3174530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavehmadavani, F.; Nguyen, V.D.; Vu, T.X.; Chatzinotas, S. Intelligent traffic steering in beyond 5G open RAN based on LSTM traffic prediction. IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications 2023, 22, 7727–7742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, A.; Sharma, V.; Hussein, L.; Aishwarya, M.; Satyanarayana, A.; Saimanohar, T. User Mobility Prediction in 5G Networks Using Recurrent Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Communication, Computing and Signal Processing (IICCCS). IEEE; 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Hu, J.; Min, G.; Zhao, Z.; Chang, Z.; Wang, Z. Spatial-temporal cellular traffic prediction for 5G and beyond: A graph neural networks-based approach. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2022, 19, 5722–5731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamshidiha, S.; Pourahmadi, V.; Mohammadi, A. A Traffic-Aware Graph Neural Network for User Association in Cellular Networks. IEEE Transactions on Mobile Computing 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matoussi, S.; Fajjari, I.; Aitsaadi, N.; Langar, R. Deep Learning based User Slice Allocation in 5G Radio Access Networks. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 45th Conference on Local Computer Networks (LCN); 2020; pp. 286–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.H.; Kim, D.; Ko, M.; Cheon, K.y.; Park, S.; Kim, Y.; Yoon, H. Ml-based 5g traffic generation for practical simulations using open datasets. IEEE communications magazine 2023, 61, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DEEPMIMO. https://www.deepmimo.net/.

- Pascanu, R.; Gulcehre, C.; Cho, K.; Bengio, Y. How to Construct Deep Recurrent Neural Networks. 2014, arXiv:cs.NE/1312.6026. [Google Scholar]

- Kingma, D.; Ba, J. Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization. International Conference on Learning Representations 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. 2023, arXiv:cs.CL/1706.03762. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, S.; Kolter, J.Z.; Koltun, V. An Empirical Evaluation of Generic Convolutional and Recurrent Networks for Sequence Modeling. 2018, arXiv:cs.LG/1803.01271]. [Google Scholar]

- Konstantoulas, I.; Loi, I.; Sgarbas, K.; Gkamas, A.; Bouras, C. A.; Bouras, C. A Deep Learning Approach to User Allocation in a 5th Generation Network. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 28th Pan-Hellenic Conference on Progress in Computing and Informatics, New York, NY, USA, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Mao, A.; Mohri, M.; Zhong, Y. Cross-Entropy Loss Functions: Theoretical Analysis and Applications. 2023, arXiv:cs.LG/2304.07288. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, J.; McCandlish, S.; Henighan, T.; Brown, T.B.; Chess, B.; Child, R.; Gray, S.; Radford, A.; Wu, J.; Amodei, D. Scaling Laws for Neural Language Models. 2020, arXiv:cs.LG/2001.08361. [Google Scholar]

- Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R.; Friedman, J.; Franklin, J. The Elements of Statistical Learning: Data Mining, Inference, and Prediction. Math. Intell. 2004, 27, 83–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).