Submitted:

14 June 2025

Posted:

17 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

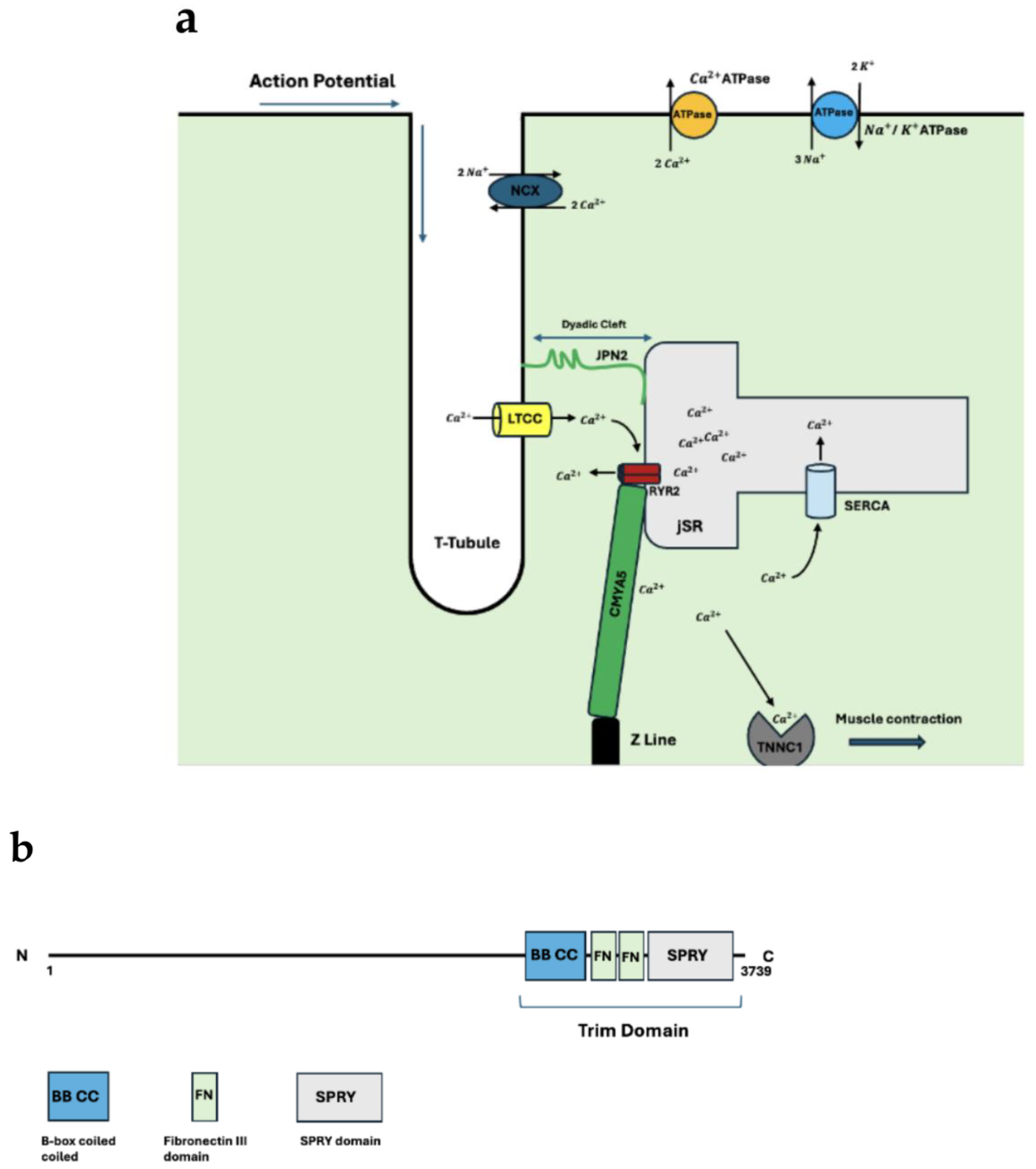

2. The Dyad

2.1. Structural Proteins of the Dyad

2.2. Functional Dyadic Proteins

2.3. Dyadic Protein Interactions

3. Mutations

3.1. Dyadic Mutations

4. Conclusion

References

- Gómez, A. M., Valdivia, H. H., Cheng, H., Lederer, M. R., Santana, L. F., Cannell, M. B., McCune, S. A., Altschuld, R. A., & Lederer, W. J. (1997). Defective excitation-contraction coupling in experimental cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. Science (New York, N.Y.), 276(5313), 800–806. [CrossRef]

- Basit, H., Brito, D., & Sharma, S. (2020). Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. PubMed; StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430788/.

- Weintraub, R. G., Semsarian, C., & Macdonald, P. (2017). Dilated cardiomyopathy. The Lancet, 390(10092), 400-414. [CrossRef]

- Lu, F., Ma, Q., Xie, W., Liou, C. L., Zhang, D., Sweat, M. E., Jardin, B. D., Naya, F. J., Guo, Y., Cheng, H., & Pu, W. T. (2022). CMYA5 establishes cardiac dyad architecture and positioning. Nature Communications.

- Poulet, C., Sanchez-Alonso, J., Swiatlowska, P., Mouy, F., Lucarelli, C., Alvarez-Laviada, A., Gross, P., Terracciano, C., Houser, S., & Gorelik, J. (2021). Junctophilin-2 tethers T-tubules and recruits functional L-type calcium channels to lipid rafts in adult cardiomyocytes. Cardiovascular research, 117(1), 149–161.

- Takeshima, H., Komazaki, S., Nishi, M., Iino, M., & Kangawa, K. (2000). Junctophilins: A Novel Family of Junctional Membrane Complex Proteins. Molecular Cell, 6(1), 11-22. [CrossRef]

- Garbino, A., & Wehrens, X. H. T. (2010). Emerging role of junctophilin-2 as a regulator of calcium handling in the heart. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica, 31(9), 1019-1021. [CrossRef]

- van Oort, R. J., Garbino, A., Wang, W., Dixit, S. S., Landstrom, A. P., Gaur, N., De Almeida, A. C., Skapura, D. G., Rudy, Y., Burns, A. R., Ackerman, M. J., & Wehrens, X. H. (2011). Disrupted junctional membrane complexes and hyperactive ryanodine receptors after acute junctophilin knockdown in mice. Circulation, 123(9), 979–988. [CrossRef]

- Casal, E., Federici, L., Zhang, W., Fernandez-Recio, J., Priego, E. M., Miguel, R. N., DuHadaway, J. B., Prendergast, G. C., Luisi, B. F., & Laue, E. D. (2006). The crystal structure of the BAR domain from human Bin1/amphiphysin II and its implications for molecular recognition. Biochemistry, 45(43), 12917–12928. [CrossRef]

- Peter, B. J., Kent, H. M., Mills, I. G., Vallis, Y., Butler, P. J., Evans, P. R., & McMahon, H. T. (2004). BAR domains as sensors of membrane curvature: the amphiphysin BAR structure. Science (New York, N.Y.), 303(5657), 495–499. [CrossRef]

- Zambo Boglarka, Edelweiss Evelina, Morlet Bastien, Negroni Luc, Pajkos Mátyás, Dosztányi Zsuzsanna, Ostergaard Soren, Trave Gilles, Laporte Jocelyn, Gogl Gergo (2024) Uncovering the BIN1-SH3 interactome underpinning centronuclear myopathy eLife 13:RP95397.

- Bodi, I., Mikala, G., Koch, S. E., Akhter, S. A., & Schwartz, A. (2005). The L-type calcium channel in the heart: the beat goes on. The Journal of clinical investigation, 115(12), 3306–3317. [CrossRef]

- Catterall, W. A., Perez-Reyes, E., Snutch, T. P., & Striessnig, J. (2005). International Union of Pharmacology. XLVIII. nomenclature and structure-function relationships of voltage-gated calcium channels. Pharmacological Reviews, 57(4), 411–425. [CrossRef]

- Lipscombe, D., Helton, T. D., & Xu, W. (2004). L-Type Calcium Channels: The Low Down. Journal of Neurophysiology, 92(5), 2633–2641. [CrossRef]

- Wahl-Schott, C., Baumann, L., Cuny, H., Eckert, C., Griessmeier, K., & Biel, M. (2006). Switching off calcium-dependent inactivation in L-type calcium channels by an autoinhibitory domain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 103(42), 15657–15662. [CrossRef]

- Striessnig, J., Pinggera, A., Kaur, G., Bock, G., & Tuluc, P. (2014). L-type Ca2+ channels in heart and brain. Wiley interdisciplinary reviews. Membrane transport and signaling, 3(2), 15–38. [CrossRef]

- Tikhonov, D. B., & Zhorov, B. S. (2009). Structural model for dihydropyridine binding to L-type calcium channels. The Journal of biological chemistry, 284(28), 19006–19017. [CrossRef]

- Bauerová-Hlinková, V., Hajdúchová, D., & Bauer, J. A. (2020). Structure and Function of the Human Ryanodine Receptors and Their Association with Myopathies-Present State, Challenges, and Perspectives. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland), 25(18), 4040. [CrossRef]

- Potenza, D. M., Janicek, R., Fernandez-Tenorio, M., Camors, E., Ramos-Mondragón, R., Valdivia, H. H., & Niggli, E. (2019). Phosphorylation of the ryanodine receptor 2 at serine 2030 is required for a complete β-adrenergic response. The Journal of general physiology, 151(2), 131–145. [CrossRef]

- Brohus, M., Søndergaard, M. T., Wayne Chen, S. R., van Petegem, F., & Overgaard, M. T. (2019). Ca2+-dependent calmodulin binding to cardiac ryanodine receptor (RyR2) calmodulin-binding domains. The Biochemical journal, 476(2), 193–209. [CrossRef]

- Sacchetto, R., Bertipaglia, I., Giannetti, S., Cendron, L., Mascarello, F., Damiani, E., Carafoli, E., & Zanotti, G. (2012). Crystal structure of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) from bovine muscle. Journal of structural biology, 178(1), 38–44. [CrossRef]

- Tsunekawa, N., Ogawa, H., Tsueda, J., Akiba, T., & Toyoshima, C. (2018). Mechanism of the E2 to E1 transition in Ca2+ pump revealed by crystal structures of gating residue mutants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(50), 12722-12727. [CrossRef]

- Periasamy, M., Bhupathy, P., & Babu, G. J. (2007). Regulation of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase pump expression and its relevance to cardiac muscle physiology and pathology. Cardiovascular Research, 77(2), 265-273. [CrossRef]

- Bal, N. C., Maurya, S. K., Sopariwala, D. H., Sahoo, S. K., Gupta, S. C., Shaikh, S. A., Pant, M., Rowland, L. A., Bombardier, E., Goonasekera, S. A., Tupling, A. R., Molkentin, J. D., & Periasamy, M. (2012). Sarcolipin is a newly identified regulator of muscle-based thermogenesis in mammals. Nature Medicine, 18(10), 1575-1579. [CrossRef]

- Bal, N. C., & Periasamy, M. (2020). Uncoupling of sarcoendoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase pump activity by sarcolipin as the basis for muscle non-shivering thermogenesis. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences, 375(1793), 20190135. [CrossRef]

- MacLennan, D. H., & Kranias, E. G. (2003). Phospholamban: a crucial regulator of cardiac contractility. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 4(7), 566-577. [CrossRef]

- Sato, D., Uchinoumi, H., & Bers, D. M. (2021). Increasing SERCA function promotes initiation of calcium sparks and breakup of calcium waves. The Journal of physiology, 599(13), 3267–3278. [CrossRef]

- Yu, S. P., & Choi, D. W. (1997). Na+-Ca2+Exchange Currents in Cortical Neurons: Concomitant Forward and Reverse Operation and Effect of Glutamate. European Journal of Neuroscience, 9(6), 1273–1281.

- Ren, X., & Philipson, K. D. (2013). The topology of the cardiac Na⁺/Ca²⁺ exchanger, NCX1. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology, 57, 68–71. [CrossRef]

- Repke, K. R., Schön, R., Henke, W., Schönfeld, W., Streckenbach, B., & Dittrick, F. (1974). Experimental and theoretical examination of the flip-flop model of (Na, K)-ATPase function. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 242(0), 203–219. [CrossRef]

- Liao, J., Li, H., Zeng, W., Sauer, D. B., Belmares, R., & Jiang, Y. (2012). Structural insight into the ion-exchange mechanism of the sodium/calcium exchanger. Science (New York, N.Y.), 335(6069), 686–690. [CrossRef]

- Xue, J., Zeng, W., Han, Y., John, S., Ottolia, M., & Jiang, Y. (2023). Structural mechanisms of the human cardiac sodium-calcium exchanger NCX1. Nature Communications, 14(1), 6181. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y. C., & Kao, L. S. (2013). Regulation of sodium-calcium exchanger activity by creatine kinase. Advances in experimental medicine and biology, 961, 163–173. [CrossRef]

- Bossuyt, J., Taylor, B. E., James-Kracke, M., & Hale, C. C. (2002). Evidence for cardiac sodium-calcium exchanger association with caveolin-3. FEBS Letters, 511(1-3), 113–117. [CrossRef]

- Lu, F., Liou, C., Ma, Q., Wu, Z., Xue, B., Xia, Y., Xia, S., Trembley, M. A., Ponek, A., Xie, W., Shani, K., Bortolin, R. H., Prondzynski, M., Berkson, P., Zhang, X., Naya, F. J., Bedi, K. C., Margulies, K. B., Zhang, D.,…Pu, W. T. (2024). Virally delivered CMYA5 enhances the assembly of cardiac dyads. Nature Biomedical Engineering.

- Hall, D. D., Hiroshi Takeshima, & Song, L.-S. (2023). Structure, Function, and Regulation of the Junctophilin Family. Annual Review of Physiology, 86(1). [CrossRef]

- Gross, P., Johnson, J., Romero, C. M., Eaton, D. M., Poulet, C., Sanchez-Alonso, J., Lucarelli, C., Ross, J., Gibb, A. A., Garbincius, J. F., Lambert, J., Varol, E., Yang, Y., Wallner, M., Feldsott, E. A., Kubo, H., Berretta, R. M., Yu, D., Rizzo, V., & Elrod, J. (2021). Interaction of the Joining Region in Junctophilin-2 With the L-Type Ca 2+ Channel Is Pivotal for Cardiac Dyad Assembly and Intracellular Ca 2+ Dynamics. Circulation Research, 128(1), 92–114. [CrossRef]

- Hong, T. T., Smyth, J. W., Gao, D., Chu, K. Y., Vogan, J. M., Fong, T. S., Jensen, B. C., Colecraft, H. M., & Shaw, R. M. (2010). BIN1 localizes the L-type calcium channel to cardiac T-tubules. PLoS biology, 8(2), e1000312. [CrossRef]

- LaitinenP. J., Brown, K. M., Piippo, K., Swan, H., Devaney, J. M., Brahmbhatt, B., Donarum, E. A., Marino, M., Tiso, N., Viitasalo, M., Toivonen, L., Stephan, D. A., & Kontula, K. (2001). Mutations of the Cardiac Ryanodine Receptor (RyR2) Gene in Familial Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia. Circulation, 103(4), 485–490. [CrossRef]

- Dulhunty A. F. (2022). Molecular Changes in the Cardiac RyR2 With Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia (CPVT). Frontiers in physiology, 13, 830367. [CrossRef]

- Lin, D. J., Lee, W. S., Chien, Y. C., Chen, T. Y., & Yang, K. T. (2021). The link between abnormalities of calcium handling proteins and catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Tzu chi medical journal, 33(4), 323–331. [CrossRef]

- Baltogiannis, G. G., Lysitsas, D. N., di Giovanni, G., Ciconte, G., Sieira, J., Conte, G., Kolettis, T. M., Chierchia, G. B., de Asmundis, C., & Brugada, P. (2019). CPVT: Arrhythmogenesis, Therapeutic Management, and Future Perspectives. A Brief Review of the Literature. Frontiers in cardiovascular medicine, 6, 92. [CrossRef]

- Bezzerides, V. J., Caballero, A., Wang, S., Ai, Y., Hylind, R. J., Lu, F., Heims-Waldron, D. A., Chambers, K. D., Zhang, D., Abrams, D. J., & Pu, W. T. (2019). Gene Therapy for Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia by Inhibition of Ca2+Calmodulin-Dependent Kinase II. Circulation, 140(5), 405-419. [CrossRef]

- Balcazar, D., Regge, V., Santalla, M., Meyer, H., Paululat, A., Mattiazzi, A., & Ferrero, P. (2018). SERCA is critical to control the Bowditch effect in the heart. Scientific Reports, 8(1). [CrossRef]

- Lyon, A. R., Bannister, M. L., Collins, T., Pearce, E., Sepehripour, A. H., Dubb, S. S., Garcia, E., O’Gara, P., Liang, L., Kohlbrenner, E., Hajjar, R. J., Peters, N. S., Poole-Wilson, P. A., Macleod, K. T., & Harding, S. E. (2011). SERCA2a Gene Transfer Decreases Sarcoplasmic Reticulum Calcium Leak and Reduces Ventricular Arrhythmias in a Model of Chronic Heart Failure. Circulation: Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology, 4(3), 362–372. [CrossRef]

- Greenberg B, Butler J, Felker GM, Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Desai AS, Barnard D, Bouchard A, Jaski B, Lyon AR, Pogoda JM, Rudy JJ, Zsebo KM. Calcium upregulation by percutaneous administration of gene therapy in patients with cardiac disease (CUPID 2): a randomised, multinational, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2b trial. Lancet. 2016 Mar 19;387(10024):1178-86. Epub 2016 Jan 21. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landstrom, A. P., Weisleder, N., Batalden, K. B., Bos, J. M., Tester, D. J., Ommen, S. R., Wehrens, X. H., Claycomb, W. C., Ko, J. K., Hwang, M., Pan, Z., Ma, J., & Ackerman, M. J. (2007). Mutations in JPH2-encoded junctophilin-2 associated with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in humans. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology, 42(6), 1026–1035.

- Reynolds, J. O., Chiang, D. Y., Wang, W., Beavers, D. L., Dixit, S. S., Skapura, D. G., Landstrom, A. P., Song, L. S., Ackerman, M. J., & Wehrens, X. H. (2013). Junctophilin-2 is necessary for T-tubule maturation during mouse heart development. Cardiovascular research, 100(1), 44–53. [CrossRef]

- Schultheiss, Heinz-Peter et al. “Dilated cardiomyopathy.” Nature reviews. Disease primers vol. 5,1 32. 9 May. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Laury-Kleintop, L. D., Mulgrew, J. R., Ido Heletz, Radu Alexandru Nedelcoviciu, Chang, M. Y., Harris, D. M., Koch, W. J., Schneider, M. D., Muller, A. J., & Prendergast, G. C. (2015). Cardiac-Specific Disruption of Bin1 in Mice Enables a Model of Stress- and Age-Associated Dilated Cardiomyopathy. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry, 116(11), 2541–2551. [CrossRef]

- Gambardella, J., Wang, X. J., Ferrara, J., Morelli, M. B., & Santulli, G. (2020). Cardiac BIN1 Replacement Therapy Ameliorates Inotropy and Lusitropy in Heart Failure by Regulating Calcium Handling. JACC. Basic to translational science, 5(6), 579–581. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).