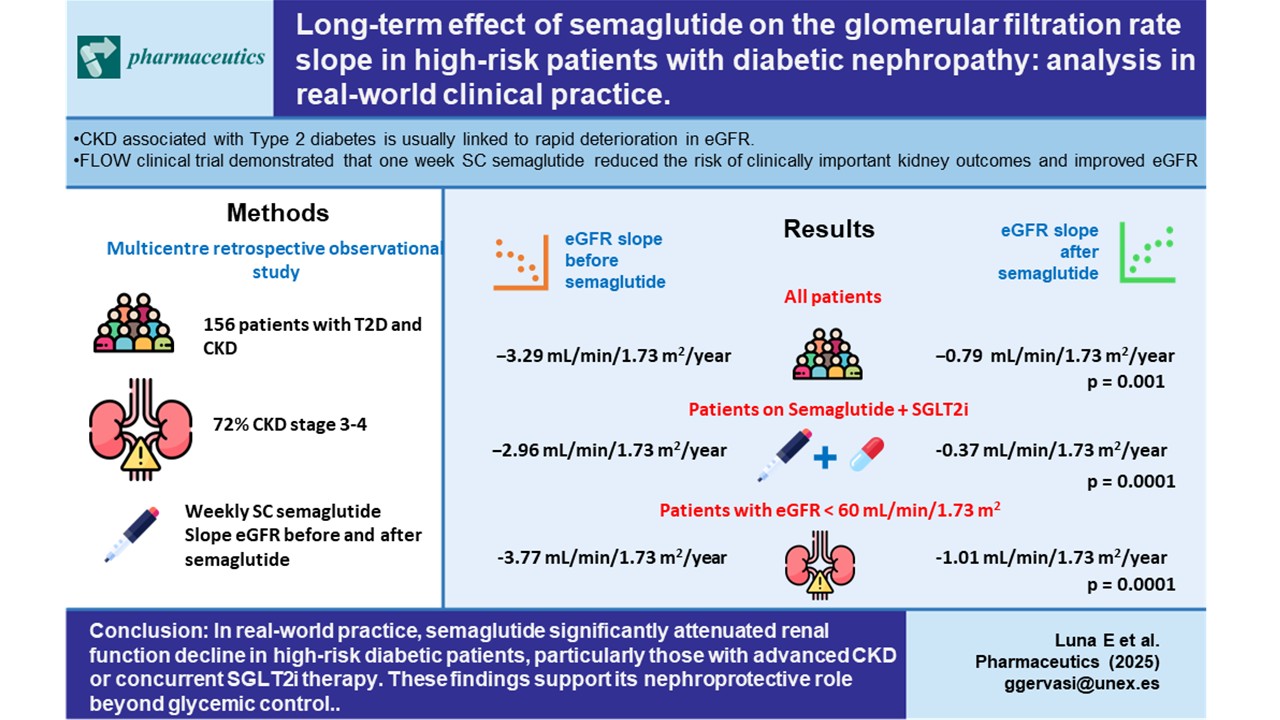

1. Introduction

Diabetic nephropathy (DN) is one of the main complications of diabetes mellitus and affects almost 40% of type 2 diabetic patients, causing a gradual deterioration of the estimated renal glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). It is known that diabetic nephropathy implies a high risk of deterioration of kidney function with a significant annual drop in eGFR. This deterioration is influenced by poor chronic glycemic control, high levels of albuminuria, inflammatory phenomena, hyperfiltration and poorly controlled hypertension. In this context, renin angiotensin aldosterone axis inhibitors (RAASi) have traditionally shown nephroprotective properties [

1,

2], as has also been reported for Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors [

3]. (SGLT2i), helping reduce the eGFR slope decline. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RA) have also been recently shown to be nephroprotective [

4,

5,

6].

Semaglutide, a GLP-1RA, has shown a beneficial impact on body mass index (BMI), abdominal fat, hepatic steatosis [

7] and inflammatory phenomena [

8,

9,

10] in the general population. In addition, its use may result in cardiovascular and renal protection in patients with kidney disease [

11,

12]. Semaglutide was first shown to display nephroprotective properties in the SUSTAIN trial [

13], a study primarily designed to evaluate protection against cardiovascular events, but that secondarily used robust criteria (reduction in the probability of requiring dialysis or the doubling of creatinine levels) to demonstrate nephroprotection. Unfortunately, the study was interrupted after 2 years and therefore long-term follow-up of these renal effects is still required.

Recent studies have concluded that to analyze a renal protective effect in a drug vs. placebo design using robust criteria requires expensive and very lengthy trials involving many patients [

14,

15]. Consequently, the evaluation of the eGFR slope with a follow-up of at least 3 years has been proposed as an adequate method to assess drug effects [

16,

17]. In this regard, post-hoc studies of semaglutide have found a significant reduction in the eGFR slope compared to placebo [

18]. Recently, the FLOW trial demonstrated a nephroprotective effect of semaglutide in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and type 2 diabetes on the eGFR slope, although only 15.6% of the recruited patients used SGLT2i [

19], and therefore the ability of the trial to assess the effect of the GLP-1AR / SGLT2i combination therapy was limited.

To date, only one real-life study of semaglutide has been carried out in diabetic patients with CKD. This work studied the safety of semaglutide but found only a slight, non-significant eGFR increase at one-year follow-up [

20]. To the best of our knowledge, no real-life studies have yet analyzed the effect of semaglutide on the eGFR slope at mid-long term, nor has it been properly determined the effect of the combined semaglutide/SGLT2i treatment. Hence, in the present work, we have aimed to fill this research gap by examining the long-term impact of semaglutide on the eGFR slope, as well as to establish the effect of the addition of this drug to patients already being treated with SGLT2i.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This was a multicenter, retrospective, observational study carried out in the nephrology services of five Spanish hospitals. The recruitment period was from January 2019 to October 2023 and patients were enrolled after signing a written informed consent. This was an observational cohort study approved by the Bioethics Committee of the institution. The inclusion criteria were patients aged over 18 years with type 2 diabetes mellitus treated with subcutaneous (SC) semaglutide, who were followed up in nephrology consultations and presented with an eGFR (calculated with the CKD EPI formula) >15 mL/min/1.73 m2 or albuminuria >30 mg/g of creatinine in urine after at least 3 tests. A minimum of one annual determination of serum creatinine and eGFR was needed during the follow-up, which was required to be longer than 2 years. Patients aged under 18 years, renal transplant recipients, patients taking part in other clinical trials, and those with both eGFR >60 mL/min/1.73 m2 or albuminuria <30 mg/g were excluded from the study.

2.2. Procedures

All the patients had received at least two oral antidiabetic medications prior to the introduction of semaglutide. Their glycemic control was closely tracked during follow-up and their antihypertensive and lipid-lowering treatment was intensified. Data from medical records were retrieved up to 4 years before administering semaglutide to study eGFR slopes prior to the treatment. Semaglutide was started at a dose of 0.25 mg SC per week, for 4 weeks. The dose was then increased to 0.5 mg/week for another 4 weeks, and then 1 mg /week. After starting treatment with semaglutide, an array of anthropometric and clinical parameters were obtained at 6 months, 1, 2, 3, and 4 years, namely weight, BMI, glycosylated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), lipid profile, high-sensitivity C reactive protein (CRP), gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT), the urinary albuminuria/creatinine ratio (UACR), and eGFR, whose slope was considered the main outcome variable of the study, as we assumed that the introduction of semaglutide has low acute effects on eGFR [

21].

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Renal function trajectory over time and decline in renal function was estimated as the slope of the individual linear regression line (B coefficient) of eGFR over the follow-up time, expressed as ± mL/min/1.73 m2/year with 95% confidence intervals (CI) in parenthesis. Negative or positive values of this parameter indicated renal disease progression or renal function improvement, respectively.

Parametric and non-parametric tests were used for the comparisons of continuous variables depending on the data distribution, whilst the chi-squared test was used to compare categorical variables. Multiple linear regression models adjusted by relevant covariates were used to assess the effect of semaglutide on the eGFR slope. Descriptive statistics are presented as mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables and as count and percentages for categorical variables. Nonparametric variables are presented as median and interquartile range (IQR). Statistical significance was established at a two-sided p-value <0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 25.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

3. Results

A total of 156 patients were included in the study with a mean follow-up of 942.3±355.4 days. The average age of the enrolled patients was 64.3 ± 15.2 years, of whom 68% were men. Fifty-one per cent of the patients had an eGFR between 30–60 mL/min/1.73 m

2 and 72% had an eGFR between 60–15 mL/min/1.73 m

2 (median = 35.8 IQR 17.1 mL/min/1.73m2). Mean proteinuria was close to 1000 mg/g creatinine but presented a marked interindividual variability. Thirty-eight per cent of the patients had macroalbuminuria (UACR >300 mg/g), although values only exceeded 1,000 mg/g in 17% of the cases. At the beginning of treatment with semaglutide, some 90% of the patients were using RAASi and 70% had already been treated with SGLT2i. Twenty-nine per cent of the patients were also taking mineralocorticoids receptor antagonists (MRA) (

Table 1).

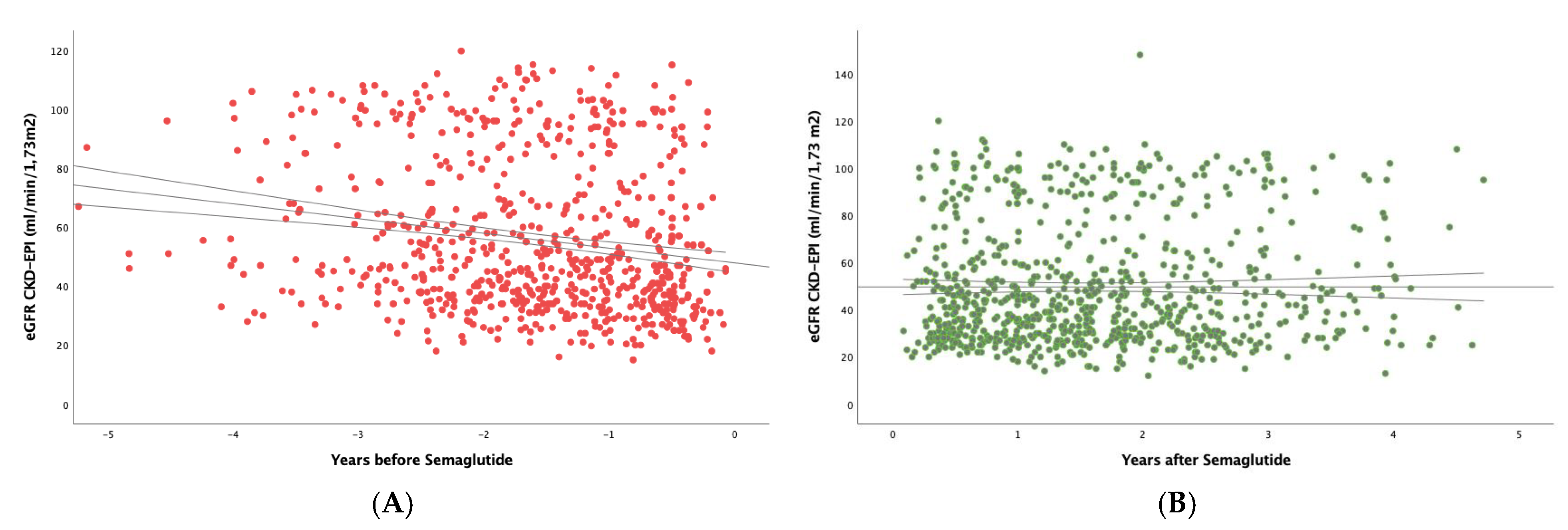

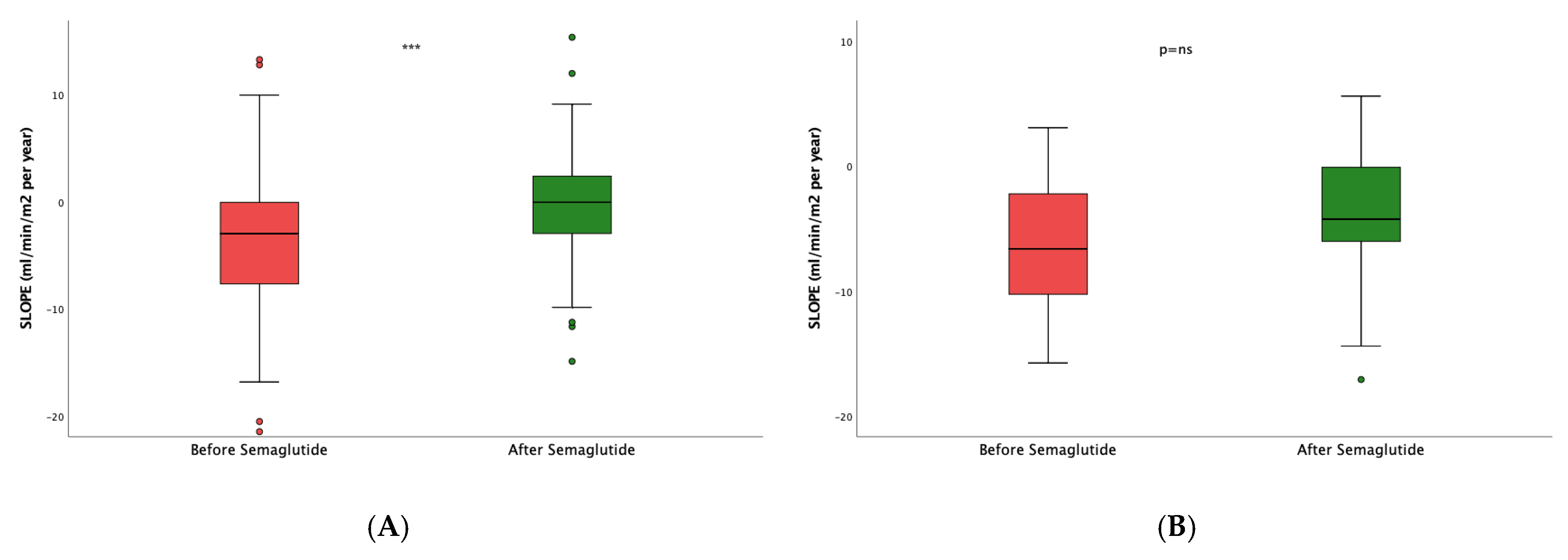

3.1. Impact of Semaglutide Treatment on eGFR Slope

To study the real effect of semaglutide on renal function, we first determined in the whole study population the eGFR slope before implementing treatment with semaglutide, obtaining a median (IQR) value of -3.29 (7.54) mL/min/1.73 m

2/year (

Figure 1A). After the administration of the drug (

Figure 1B), the eGFR slope significantly increased to -0.79 (6.01) mL/min/1.73 m

2 per year (p<0.001).

Multiple linear regression models adjusted by relevant covariates, namely use of SGLT2i, RAASi, MRA and albuminuria revealed that the effect of semaglutide on the eGFR slope showed a hazard ratio (HR) of 4.06 (2.43-5.68), p< 0.001.

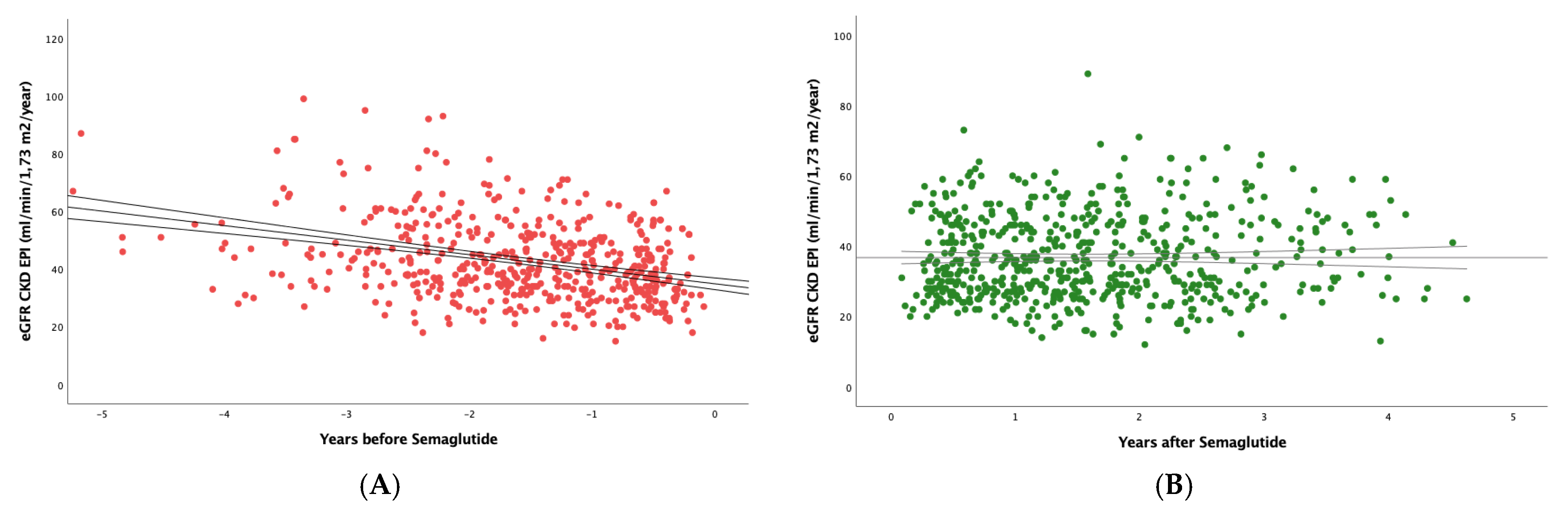

Figure 2 shows that, in the subset of patients with eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2, semaglutide had an even greater effect, as the slope went from -3.77(6.88) to -1.01(5.29) mL/min/1.73 m

2/year; (p<0.0001).

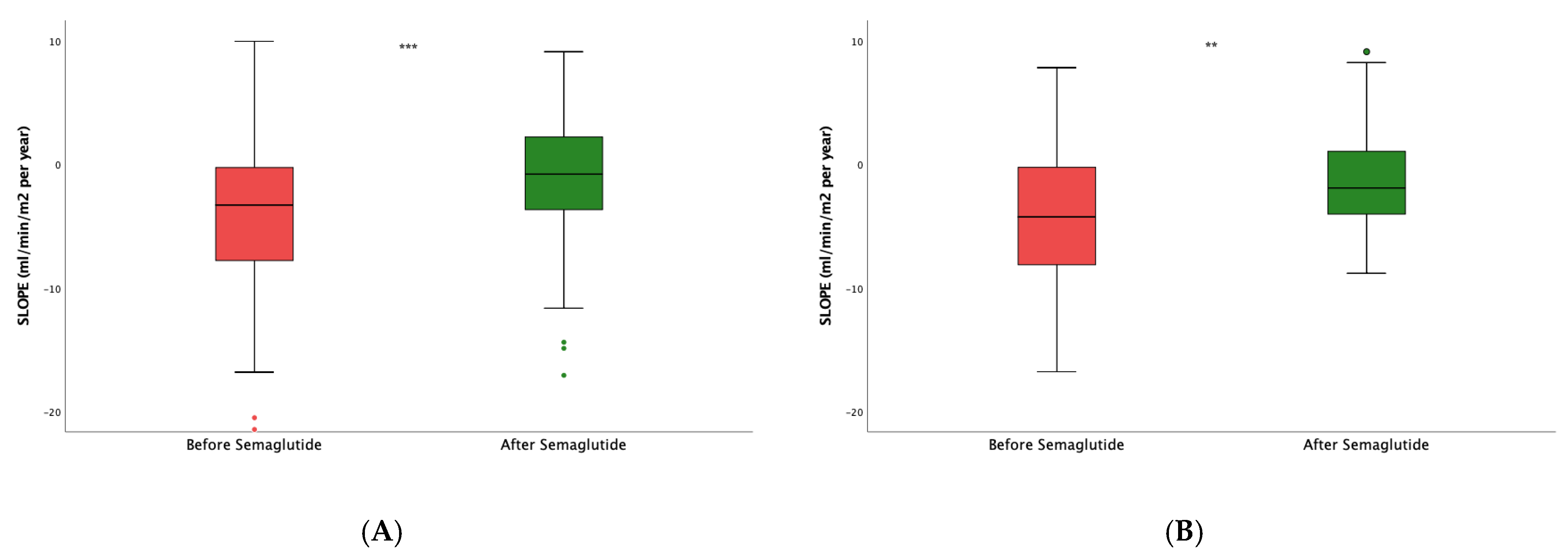

Next, to assess the impact of the dual semaglutide/SLGT2i therapy, we then restrained the analysis to patients already taking SGLT2i. After the introduction of semaglutide, the slope varied from -2.96 (7.27) to -0.37 (5.87) mL/min/1.73 m

2/year, p<0.0001 (

Figure 3A). In patients who were not on SGLT2i (

Figure 3B), the slope also stabilized with respect to the values before the intervention -4.25(8.07) vs. -1.91 (5.37) mL/min/1.73 m

2/year (p=0.01). However, the difference in the slope increment between both groups, i.e., patients on dual therapy and those only on semaglutide, was not statistically significant (p=0.805).

We finally analyzed changes in the eGFR slope according to the different degrees of albuminuria. Patients with UACR = 30–1,000 mg/g had a median slope of -2.96 (7.22) before semaglutide and -0.04 (5.34) mL/min/1.73 m

2/year after semaglutide (p<0.0001;

Figure 4A). For those patients with UACR > 1,000 mg/g (

Figure 4 B) the increase was much smaller, as eGFR values went from -6.61 (9.09) to -4.24 (6.07) mL/min/1.73 m

2/year (p=0.184). As in the case of dual vs. monotherapy, there were no significant differences when we compared the slope increments obtained with the treatment for patients with low and high UACR values (p=0.274).

3.2. Effect of Semaglutide on Other Clinical Parameters

Table 2 shows that BMI values decreased significantly during the follow-up (from 29.1±4.8 to 27.3±4.4, p=0.04), as did HBA1c levels (from 7.3 (2.1) to 6.6(1.9) %, p=0.002). An improvement in triglyceride levels was also evident (from 219.2±142.7 to 162.2±9.5). In the same manner, there were subclinical inflammatory phenomena at baseline, as measured by CRP, which were significantly reduced at the end of the study (p=0.003). The degree of hepatic steatosis, monitored by determining the plasma GGT [

22,

23], also showed a significant reduction (p=0.004). In contrast, no significant changes were observed in proteinuria or albuminuria, although it should be noted that patients at baseline presented with an extremely high variability, and that most patients had low albuminuria at the beginning of the study.

4. Discussion

CKD associated with type II diabetes mellitus causes significant cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. It is also associated with a high risk of progressive worsening of kidney function and a high risk of end-stage kidney disease and dialysis. In turn, this decline in renal function leads to a greater risk of cardiovascular disease and death [

24]. This is basically the reason why therapies that lead to stability or improvement in kidney function also improve the general prognosis of these patients.

The SUSTAIN-6 trial demonstrated that SC semaglutide reduces the risk of major renal events, when considered as a composite variable, by reducing macroalbuminuria [

13]. However, the study did not show significant differences compared with placebo regarding the need for dialysis or the doubling of serum creatinine. These studies, whose primary objective is cardiovascular safety, are generally too short to assess renal protection using robust and longer-term endpoints such as doubling of creatinine or initiation of dialysis. The dynamic study of the eGFR slope, such as that reported herein and elsewhere [

25] has been proposed to be better suited to achieve significant results in the midterm.

On the other hand, a meta-analysis by Sattar et al. on the nephro and cardioprotective effects of GLP-1RA12 reported a neutral effect on the overall kidney function4. It should be noted, however, that the potency and pharmacokinetic characteristics of the different GLP-1-AR used in the trials differed significantly [

26], which could have generated some bias. In this regard, we exclusively used SC semaglutide in our study to avoid variations in bioavailability, which are inherent to oral formulations. Recently, the FLOW trial demonstrated a nephroprotective effect of semaglutide in patients with CKD and type 2 diabetes, as the risk of a primary outcome event was 24% lower, and the mean annual eGFR slope was less steep in the semaglutide group [

19]. However, SGLT2i and MRA agents were not yet approved when the trial began and hence the ability of the study to assess the effect of combination therapy with semaglutide was very limited. In our analysis, we studied patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and CKD with a marked decline in kidney function and high risk of kidney function deterioration. After starting semaglutide, we found that the eGFR slope improved significantly in the mid/long-term. These findings agree with post-hoc studies from the SUSTAIN trial demonstrating that SC semaglutide had a particularly beneficial effect on the eGFR slope decline when compared to placebo, an effect that was greater than that of oral semaglutide or liraglutide [

18].

To the best of our knowledge, there are no previous reports studying the effect of SC semaglutide on the eGFR slope in real-life practice, let alone with a mean follow-up of 3 years and in a sizeable cohort of patients with reduced renal function. Remarkably, in our study, it was precisely the patients with more compromised renal function who benefited the most from the introduction of semaglutide, which highlights the potential of this drug to improve cardiovascular function in a high-risk population such as CKD patients by stabilizing (and even improving) their kidney function.

It has also been shown that a combined SGLT2i / GLP-1AR therapy in a diabetic population with CKD stage 3/4 (eGFR=15-60 mL/min/1.73 m

2) and high risk of rapid deterioration of kidney function, may have a synergistic cardio- and nephroprotective effect [

27]. Our study, which included patients with a steeply negative eGFR slope, and that therefore had higher morbidity levels and a greater risk of kidney failure [

24], confirms that nephroprotection was evident in patients on dual therapy. Even though in absolute numbers this group finished with a far lower eGFR slope than patients on semaglutide alone, nonparametric tests yielded no statistical differences between both populations. In any case, it is remarkable that patients on dual therapy reached an annual decline of only -0.37 mL/min, when the average decline in healthy subjects from 40 years of age onwards is approximately -1 ml/min/year [

28,

29]. The effect of this combined SGLT2i / GLP-1AR treatment could not be assessed in former seminal trials such as the SUSTAIN 6 study (with only 2% of the patients treated with SGLT2i) [

13] or the FLOW study (15.6% patients on dual treatment) [

19]. In any case, it should be noted that, in our study, patients who were not treated with SGLT2i also presented a significant improvement in the negative slope of eGFR after being administered semaglutide.

With regard to the role of albuminuria, our data showed that patients with lower levels of albuminuria (<1,000 mg/g) presented better slopes than those with UACR values above 1,000 mg/g. However, only 17% of our patients presented with UACR > 1000 mg/g and hence, drawing conclusions for this specific subgroup is adventurous. This selection bias could also explain why we did not observe a significant improvement in albuminuria values during the follow-up, as opposed to the data reported by the SUSTAIN trial.

Finally, we observed a significant reduction in the BMI values of our patients after the introduction of semaglutide. Weight loss in the population with diabetic nephropathy is extremely beneficial, not only because it reduces cardiovascular risk inherent to obesity, but also because it decreases hyperfiltration by the remaining functional nephrons in patients with kidney failure, which protects them against the development of further sclerosis of the glomeruli, therefore reducing the risk of progression of kidney damage [

30]. In addition, the reduction of adipose tissue produced by semaglutide decreases its capacity to generate potentially harmful cytokines and hormones [

31,

32,

33,

34]. Moreover, we observed several other additional beneficial effects after the long-term treatment with semaglutide, such as a decrease in inflammatory markers and improvement in hepatic steatosis, which are involved in insulin resistance and the poor cardiovascular prognosis that these patients present [

8,

10,

35,

36].

This study has several limitations. First, because of its observational and retrospective nature, a causal relationship cannot be formally established based on our findings; second, follow-up data for the time SGLT2i had been used prior to starting semaglutide were not available, which could have provided more context for the interpretation of the eGFR slope before the introduction of semaglutide; third, the improvement in eGFR could also be the result of an unquantified loss of lean mass after weight loss and, finally, we did not used cystatin C to calculate eGFR, which could have been rendered more accurate values.

In conclusion, the findings of this real-life study indicate that the use of semaglutide in diabetic patients with a high risk of CKD can prevent the progressive decline in renal function they would otherwise invariably experience. Renal protection was especially marked in patients with more compromised renal function (CKD stages 3 and 4), and in those with a dual semaglutide / SGLT2i therapy. Further studies including larger cohorts are anyway warranted to confirm the results presented herein.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Enrique Luna and Guillermo Gervasini; Data curation, Álvaro Álvarez, Jorge Rodriguez-Sabiñón, Juan Villa, Teresa Giraldo, Maria Victoria Martín, Eva Vázquez, Noemi Fernández, Belén Ruiz, Guadalupe Garcia-Pino, Coral Martínez, Lilia Azevedo and Rosa María Diaz; Formal analysis, Enrique Luna; Funding acquisition, Guillermo Gervasini; Investigation, Álvaro Álvarez, Jorge Rodriguez-Sabiñón, Juan Villa, Teresa Giraldo, Maria Victoria Martín, Eva Vázquez, Noemi Fernández, Belén Ruiz, Guadalupe Garcia-Pino, Coral Martínez, Lilia Azevedo and Rosa María Diaz; Writing—original draft, Enrique Luna and Guillermo Gervasini; Writing—review & editing, Nicolas Roberto Robles.

Funding

This research was funded by grant PI22/00181 and RD24/0004/0012 from Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid (Spain), financed by the European Union—NextGeneration UE, Recovery and Resilience Mechanism, and grant GR24027 from Junta de Extremadura, Mérida (Spain) and Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER) “Una manera de hacer Europa”. Funding sources did not have any involvement in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committees of the Badajoz University Hospital with registry number 2025010.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Caravaca Magariños for his help with statistical analyses and Mrs. Josefa Emilia Cruz with the collation of data.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Enrique Luna has received speaker honoraria and financial support for attending symposia from Novo Nordisk, Lilly, GSK and Esteve. The other authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CKD |

Chronic kidney disease |

| DN |

Diabetic nephropathy |

| eGFR |

Estimated glomerular filtration rate |

| GLP-1AR |

Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist |

| RAASi |

Renin angiotensin aldosterone axis inhibitors |

| SGLT2i |

Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors |

| UACR |

Urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio |

References

- Currie, G. Biomarkers in diabetic nephropathy: Present and future. World J. Diabetes 2014, 5, 763–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, E.J.; Hunsicker, L.G.; Clarke, W.R.; Berl, T.; Pohl, M.A.; Lewis, J.B.; Ritz, E.; Atkins, R.C.; Rohde, R.; Raz, I.; et al. Renoprotective Effect of the Angiotensin-Receptor Antagonist Irbesartan in Patients with Nephropathy Due to Type 2 Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 345, 851–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heerspink, H.J.L.; Jongs, N.; Chertow, G.M.; Langkilde, A.M.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Correa-Rotter, R.; Rossing, P.; Sjöström, C.D.; Stefansson, B.V.; Toto, R.D.; et al. Effect of dapagliflozin on the rate of decline in kidney function in patients with chronic kidney disease with and without type 2 diabetes: a prespecified analysis from the DAPA-CKD trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021, 9, 743–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Song, Y.; Guo, T.; Xiao, G.; Li, Q. Effect of glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists on the renal protection in patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab. 2022, 48, 101366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.K.; Sperati, C.J.; Thavarajah, S.; Grams, M.E. Reducing Kidney Function Decline in Patients With CKD: Core Curriculum 2021. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2021, 77, 969–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lui, D.T.W.; Au, I.C.H.; Tang, E.H.M.; Cheung, C.L.; Lee, C.H.; Woo, Y.C.; Wu, T.; Tan, K.C.B.; Wong, C.K.H. Kidney outcomes associated with sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors versus glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists: A real-world population-based analysis. eClinicalMedicine 2022, 50, 101510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsome, P.N.; Buchholtz, K.; Cusi, K.; Linder, M.; Okanoue, T.; Ratziu, V.; Sanyal, A.J.; Sejling, A.-S.; Harrison, S.A. A Placebo-Controlled Trial of Subcutaneous Semaglutide in Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. New Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 1113–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosenzon, O.; Capehorn, M.S.; De Remigis, A.; Rasmussen, S.; Weimers, P.; Rosenstock, J. Impact of semaglutide on high-sensitivity C-reactive protein: exploratory patient-level analyses of SUSTAIN and PIONEER randomized clinical trials. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2022, 21, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reppo, I.; Jakobson, M.; Volke, V. Effects of Semaglutide and Empagliflozin on Inflammatory Markers in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsome, P.; Francque, S.; Harrison, S.; Ratziu, V.; Van Gaal, L.; Calanna, S.; Hansen, M.; Linder, M.; Sanyal, A. Effect of semaglutide on liver enzymes and markers of inflammation in subjects with type 2 diabetes and/or obesity. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 50, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Chen, S.; Ren, Q.; Niu, S.; Pan, X.; Yue, L.; Li, Z.; Zhu, R.; Jia, Z.; Chen, X.; et al. Metabolomics Provides Insights into Renoprotective Effects of Semaglutide in Obese Mice. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2022, ume 16, 3893–3913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattar, N.; Lee, M.M.Y.; Kristensen, S.L.; Branch, K.R.H.; Del Prato, S.; Khurmi, N.S.; Lam, C.S.P.; Lopes, R.D.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Pratley, R.E.; et al. Cardiovascular, mortality, and kidney outcomes with GLP-1 receptor agonists in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021, 9, 653–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marso, S.P.; Bain, S.C.; Consoli, A.; Eliaschewitz, F.G.; Jódar, E.; Leiter, L.A.; Lingvay, I.; Rosenstock, J.; Seufert, J.; Warren, M.L.; et al. Semaglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1834–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greene, T.; Ying, J.; Vonesh, E.F.; Tighiouart, H.; Levey, A.S.; Coresh, J.; Herrick, J.S.; Imai, E.; Jafar, T.H.; Maes, B.D.; et al. Performance of GFR Slope as a Surrogate End Point for Kidney Disease Progression in Clinical Trials: A Statistical Simulation. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2019, 30, 1756–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.S.; Bakris, G.L.; Shahid, I.; Weir, M.R.; Butler, J. Potential Role and Limitations of Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate Slope Assessment in Cardiovascular Trials. JAMA Cardiol. 2022, 7, 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inker, L.A.; Heerspink, H.J.L.; Tighiouart, H.; Levey, A.S.; Coresh, J.; Gansevoort, R.T.; Simon, A.L.; Ying, J.; Beck, G.J.; Wanner, C.; et al. GFR Slope as a Surrogate End Point for Kidney Disease Progression in Clinical Trials: A Meta-Analysis of Treatment Effects of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2019, 30, 1735–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, W.; Inker, L.A.; Haaland, B.; Appel, G.B.; Badve, S.V.; Caravaca-Fontán, F.; Chalmers, J.; Floege, J.; Goicoechea, M.; Imai, E.; et al. Evaluation of Variation in the Performance of GFR Slope as a Surrogate End Point for Kidney Failure in Clinical Trials that Differ by Severity of CKD. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2023, 18, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaman, A.M.; Bain, S.C.; Bakris, G.L.; Buse, J.B.; Idorn, T.; Mahaffey, K.W.; Mann, J.F.; Nauck, M.A.; Rasmussen, S.; Rossing, P.; et al. Effect of the Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists Semaglutide and Liraglutide on Kidney Outcomes in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes: Pooled Analysis of SUSTAIN 6 and LEADER. Circulation 2022, 145, 575–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkovic, V.; Tuttle, K.R.; Rossing, P.; Mahaffey, K.W.; Mann, J.F.; Bakris, G.; Baeres, F.M.; Idorn, T.; Bosch-Traberg, H.; Lausvig, N.L.; et al. Effects of Semaglutide on Chronic Kidney Disease in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. New Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, B.A.; Soler, M.J.; Perez-Belmonte, L.; Millan, A.J.; Ruiz, F.R.; de Lucas, M.D.G. Semaglutide in type 2 diabetes with chronic kidney disease at high risk progression—real-world clinical practice. Clin. Kidney J. 2022, 15, 1593–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E Mann, J.F.; Hansen, T.; Idorn, T.; A Leiter, L.; Marso, S.P.; Rossing, P.; Seufert, J.; Tadayon, S.; Vilsbøll, T. Effects of once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide on kidney function and safety in patients with type 2 diabetes: a post-hoc analysis of the SUSTAIN 1–7 randomised controlled trials. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020, 8, 880–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Huang, M.; Shyu, Y.; Chien, R. Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase elevation is associated with metabolic syndrome, hepatic steatosis, and fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A community-based cross-sectional study. Kaohsiung J. Med Sci. 2021, 37, 819–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haring, R.; Wallaschofski, H.; Nauck, M.; Dörr, M.; Baumeister, S.E.; Völzke, H. Ultrasonographic hepatic steatosis increases prediction of mortality risk from elevated serum gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase levels # †. Hepatology 2009, 50, 1403–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Hauske, S.; Ono, Y.; Kyaw, M.H.; Steubl, D.; Naito, Y.; Kanasaki, K. Analysis of eGFR index category and annual eGFR slope association with adverse clinical outcomes using real-world Japanese data: a retrospective database study. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e052246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuttle, K.R.; Bosch-Traberg, H.; Cherney, D.Z.; Hadjadj, S.; Lawson, J.; Mosenzon, O.; Rasmussen, S.; Bain, S.C. Post hoc analysis of SUSTAIN 6 and PIONEER 6 trials suggests that people with type 2 diabetes at high cardiovascular risk treated with semaglutide experience more stable kidney function compared with placebo. Kidney Int. 2023, 103, 772–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klen, J.; Dolžan, V. Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists in the Management of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Obesity: The Impact of Pharmacological Properties and Genetic Factors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnott, C.; Neuen, B.L.; Heerspink, H.J.; Figtree, G.A.; Kosiborod, M.; Lam, C.S.; Cannon, C.P.; Rosenthal, N.; Shaw, W.; Mahaffey, K.W.; et al. The effects of combination canagliflozin and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist therapy on intermediate markers of cardiovascular risk in the CANVAS program. Int. J. Cardiol. 2020, 318, 126–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E.; Nardi, Y.; Krause, I.; Goldberg, E.; Milo, G.; Garty, M.; Krause, I. A longitudinal assessment of the natural rate of decline in renal function with age. J. Nephrol. 2014, 27, 635–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, M.; Shimbo, T.; Horio, M.; Ando, M.; Yasuda, Y.; Komatsu, Y.; Masuda, K.; Matsuo, S.; Maruyama, S.; Abe, H. Longitudinal Study of the Decline in Renal Function in Healthy Subjects. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0129036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Look AHEAD Research Group Effect of a long-term behavioural weight loss intervention on nephropathy in overweight or obese adults with type 2 diabetes: a secondary analysis of the Look AHEAD randomised clinical trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014, 2, 801–809. [CrossRef]

- Gervasini, G.; García-Pino, G.; Mota-Zamorano, S.; Luna, E.; García-Cerrada, M.; Tormo, M.Á.; Cubero, J.J. Association of polymorphisms in leptin and adiponectin genes with long-term outcomes in renal transplant recipients. Pharmacogenomics J. 2019, 20, 388–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Pino, G.; Luna, E.; Blanco, L.; Tormo, M.Á.; Mota-Zamorano, S.; González, L.M.; Azevedo, L.; Robles, N.R.; Gervasini, G. Body Fat Distribution, Adipocytokines Levels and Variability in Associated Genes and Kidney Transplant Outcomes. Prog. Transplant. 2022, 32, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mota-Zamorano, S.; Luna, E.; Garcia-Pino, G.; González, L.M.; Gervasini, G. Combined donor-recipient genotypes of leptin receptor and adiponectin gene polymorphisms affect the incidence of complications after renal transplantation. Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mota-Zamorano, S.; Luna, E.; Garcia-Pino, G.; González, L.M.; Gervasini, G. Variability in the leptin receptor gene and other risk factors for post-transplant diabetes mellitus in renal transplant recipients. Ann. Med. 2019, 51, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkovic, M.C.; Rezic, T.; Bilic-Curcic, I.; Mrzljak, A. Semaglutide might be a key for breaking the vicious cycle of metabolically associated fatty liver disease spectrum? World J. Clin. Cases 2022, 10, 6759–6768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barritt, A.S.; Marshman, E.; Noureddin, M. Review article: role of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, obesity and diabetes—what hepatologists need to know. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 55, 944–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).