6.1. Opportunities

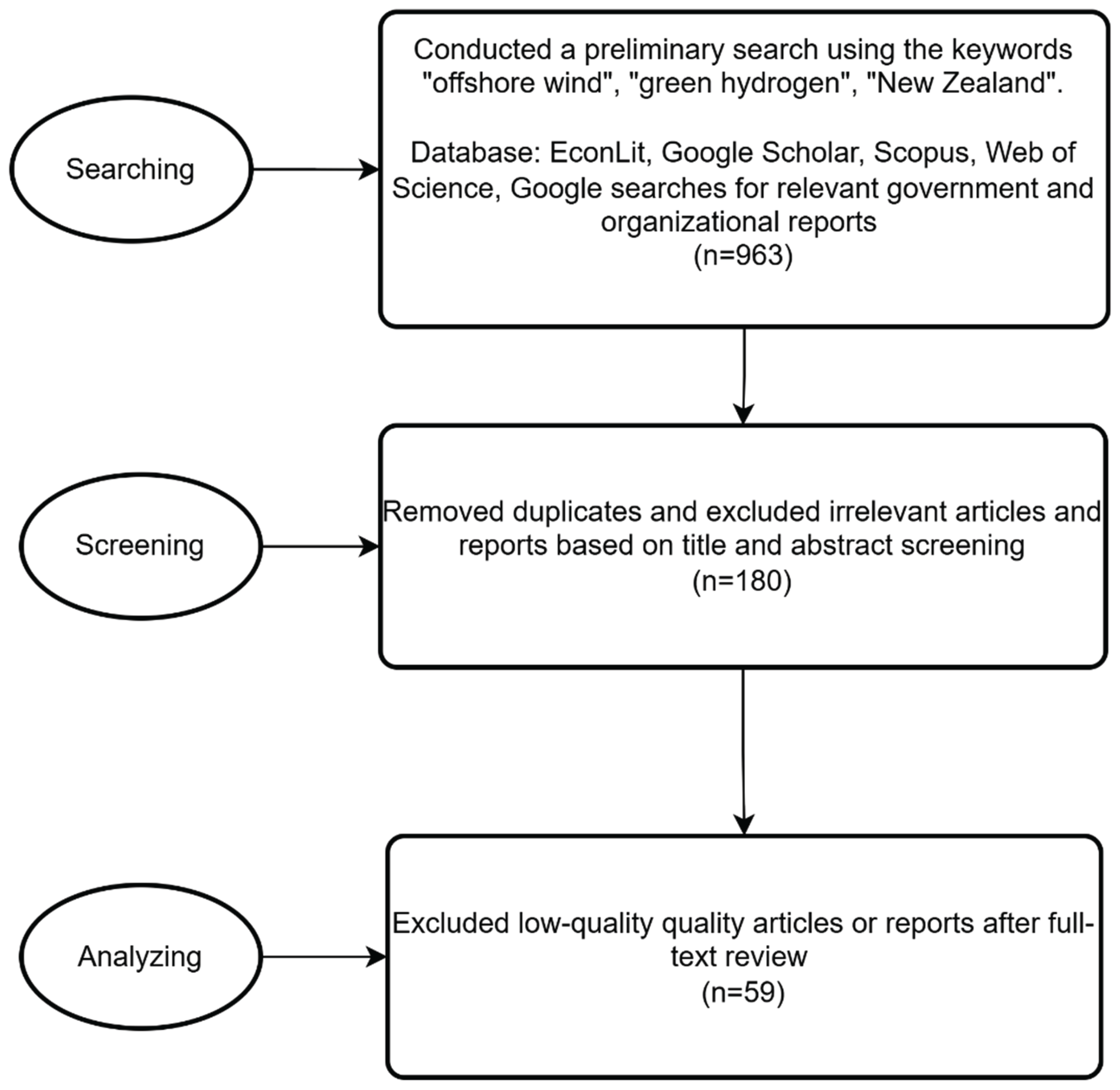

At 85%, New Zealand has the fourth highest renewable electricity percentage in the OECD and is looking to get to 100% by 2035 [

33]. Other targets include a greenhouse gas emissions reduction of 30% by 2030, relative to 2005 levels, and net zero emission by 2050 [

34]. Even though electricity is from mostly renewables, NZ’s total energy supply is only comprised of 40% renewables, with the rest from fossil fuels, to use during periods of peak and dry year demands [

34]. There is still significant untapped renewable energy potential in the country such as wind, solar, and biomass, and will be needed to meet their ambitious target by 2035. In March 2020 the Ministry of Business, Innovation, and Employment released a report which identified potential 8GW of offshore wind capacity in NZ but noted that development to harness this, was unlikely before 2050 due to vast amounts of onshore site potential that still exists [

35]. NZ notably has one of the best wind resources in the world due to its location where constant westerly winds travelling across the ocean are uninterrupted by other landforms [

35]. According to the World Bank data [

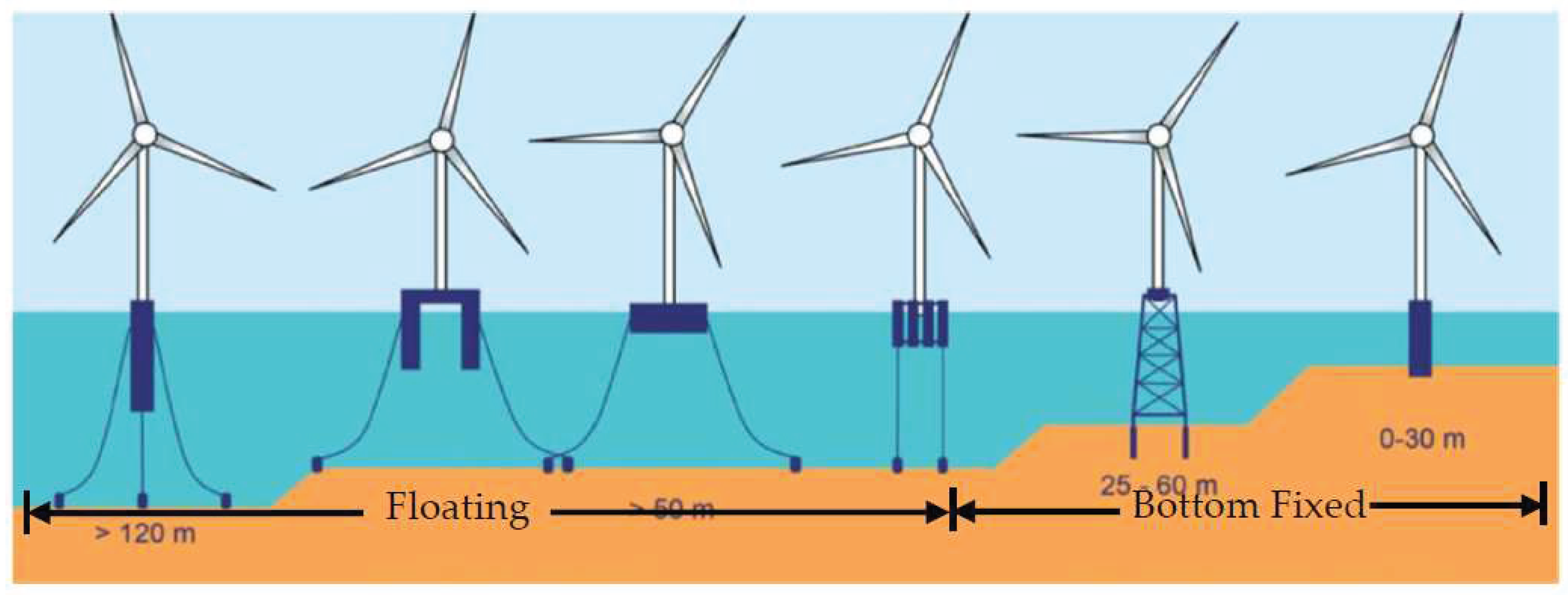

36], it is evident that NZ has extremely large potential for floating fixtures, relative to its potential for fixed foundations. It is also among the leaders of energy potential in the East Asian and Pacific region, just behind Australia and China.

Electricity demand in NZ is significantly increasing with Transpower, a state-owned electricity company, forecasting in 2018, that demand will grow from 43TWh/year to 88TWh/year by 2050 [

37]. This includes the assumptions that many sectors in NZ will be electrified, such as transport and some industrial processes, also accounting for the fact that energy systems will become more efficient in the future [

37]. As mentioned above, NZ experiences dry winters, which is where the energy output from hydro power plants (the majority of electricity generation) decreases during the winter whilst electricity demand for heating and lighting increases. With NZ scaling up to become 100% reliant on renewable electricity sources by 2035, the storage of excess electricity generation to counter seasonal shifts is important to give the country’s grid more reliability and not have to burn emergency fossil fuels as they have done before. Hydrogen is likely to be the answer to this problem.

In 2019, the NZ government released a green paper titled ‘A vision for hydrogen in New Zealand’ which looked into the potential for hydrogen production, export, and utilization in the economy. Like other countries that are looking into hydrogen, they envision hydrogen to act as a versatile energy carrier, using excess electricity from summer generation to produce hydrogen to be stored for use in winter, and also possibly using existing natural gas pipeline networks for transmission and distribution [

33]. In addition, they will use existing oil and gas rigs to construct electrolyzers and offshore wind farms to be used in conjunction with one another [

33]. With proximity to potential hydrogen importing countries such as Japan and South Korea, the government aims to develop green hydrogen as a potential export [

33]. These countries may be good partners as when NZ’s lower energy consumption occurs during its summer months, major north Asian markets experience high winter demand and therefore NZ can use surplus electricity to produce hydrogen for export. They have noted that further studies should be undertaken to identify how hydrogen can realize these potential export earnings whilst creating jobs in the process ([

33] “A vision for hydrogen in New Zealand”, 2019). A December 2021 Power-to-X report by Venture Taranaki, an economic development agency in New Plymouth, also explored using green hydrogen to produce green methane, to replace existing natural gas [

38]. It regarded this process as a ‘simple substitute’ as it can easily replace current non-renewable natural gas by using existing infrastructure such as storage in Ahuroa Gas Storage Field, with an easy transition by using the same appliances and gas fired power stations currently being utilized today [

38]. However, this report did not discuss the use of CCS, which is an important aspect of using natural gas and still achieving net zero emissions.

A particular site for potentially large projects in offshore wind and hydrogen is in Taranaki, located near the middle of the country, and its waters surrounding the area. Analysis from the Department of Civil and Natural Resources Engineering from the University of Canterbury showed that South Taranaki’s offshore wind is a very viable source of energy with 1065km

2 of suitable area for fixed foundation turbines, with additional space for floating ones also being identified [

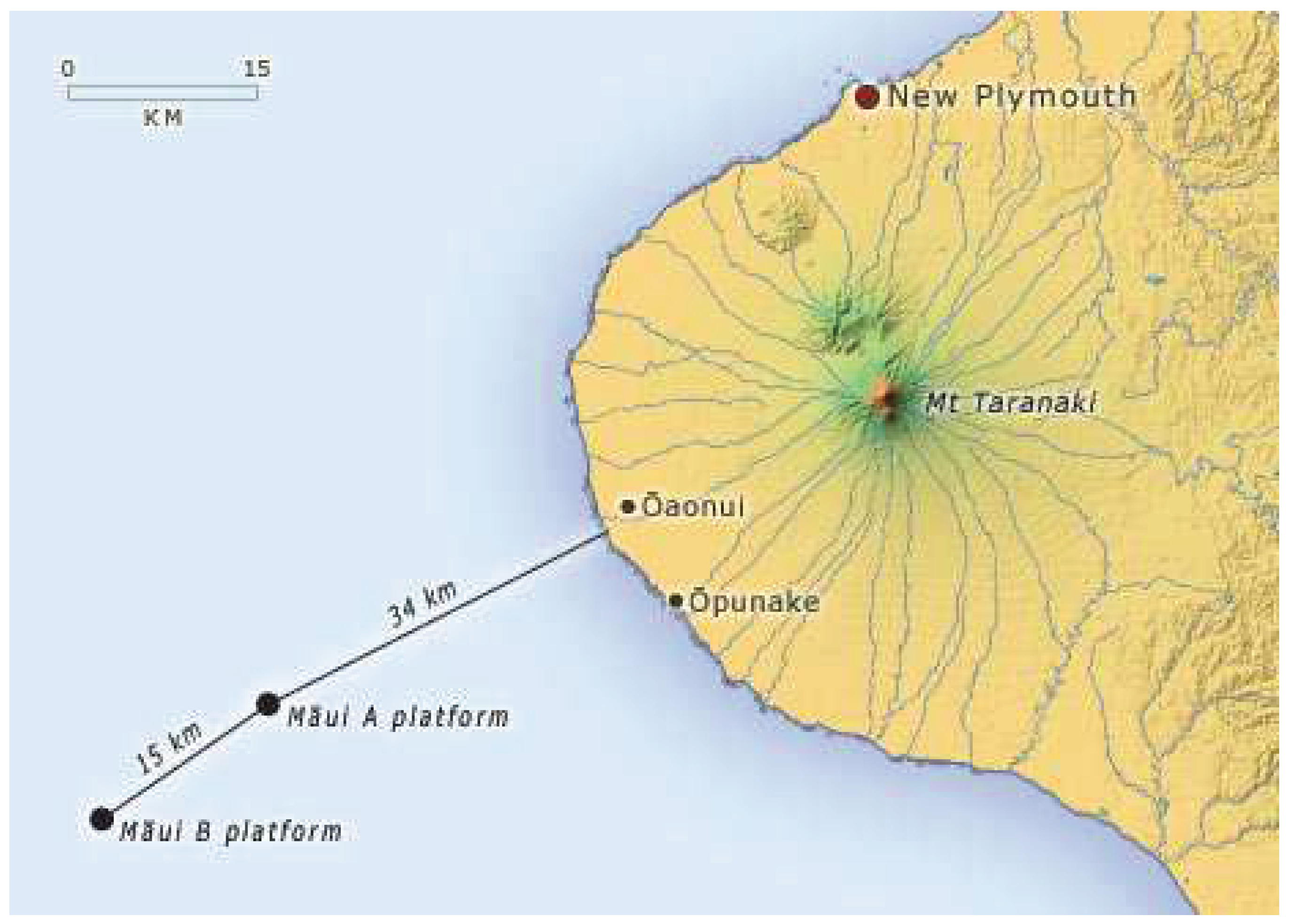

39]. At existing gas fields in the area, Māui A and Māui B as seen in

Figure 5, the mean 5-year wind speeds at these sites were 10.12 m/s and 10.73m/s, respectively, with Māui B being further offshore than A [

39]. Ishwar and Mason [

39] also expected capacity for offshore wind based on the wind speeds from Māui A to be 56.9% gross, and 46.3% accounting for downtime losses. This would mean that the site, accommodating a 7016MW wind farm using 877 x 8MW turbines, would produce approximately 28,456 GWh/year [

39].

This analysis is backed up by an offshore wind discussion paper from Venture Taranaki who add that the region has significant areas of water with less than 50m depth and a flat seabed, which are suitable for fixed turbines [

37]. Venture’s analysis suggests an even larger suitable area in South Taranaki for fixed turbines with 1,800km

2, adding that 370km

2 in North Taranaki are suitable as well [

37]. When fully developed, the wind capacity in these areas could reach 12GW and 2.4GW, possibly doubling NZ’s current electricity supply from these farms alone [

37]. Considering floating turbines, the report suggests another 14,000km

2 of suitable area for this method, possibly adding 90GW to NZ’s grid, far surpassing the energy demand forecast for 2050 [

37]. Whether or not it is feasible for offshore wind to meet its construction targets of 26,620 GWh/year between 2020 and 2050, Ishwar and Mason [

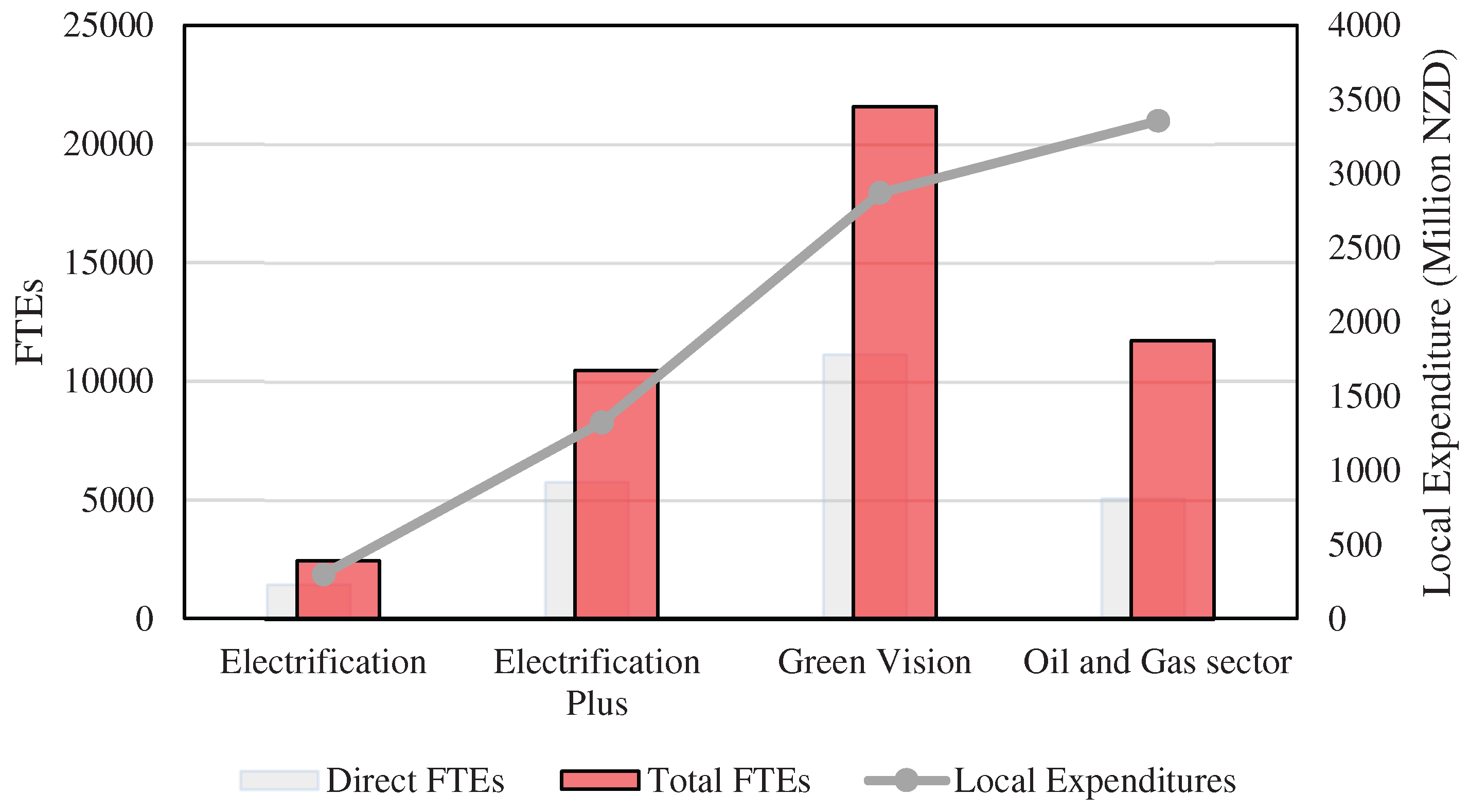

39] found that a build rate of 0.0046 years/MW would be required. With build rates of less than 0.005 years/MW currently in operation in Europe, it may be feasible for NZ to follow suit and achieve their targets. Venture Taranaki, is partnership with the New Plymouth District Council and Hiringa Energy, has also released a report called ‘H

2 Taranaki Roadmap’ which looks at a series of potential business scenarios for adopting hydrogen in the region. They envision Port Taranaki to become a hub for hydrogen export, with the port experienced in handling industrial chemicals [

34]. They would use existing gas networks to cost-effectively transport hydrogen generated elsewhere back to the port, to be ready for export, with potential for integration with international supply chains established through the fossil fuel industry [

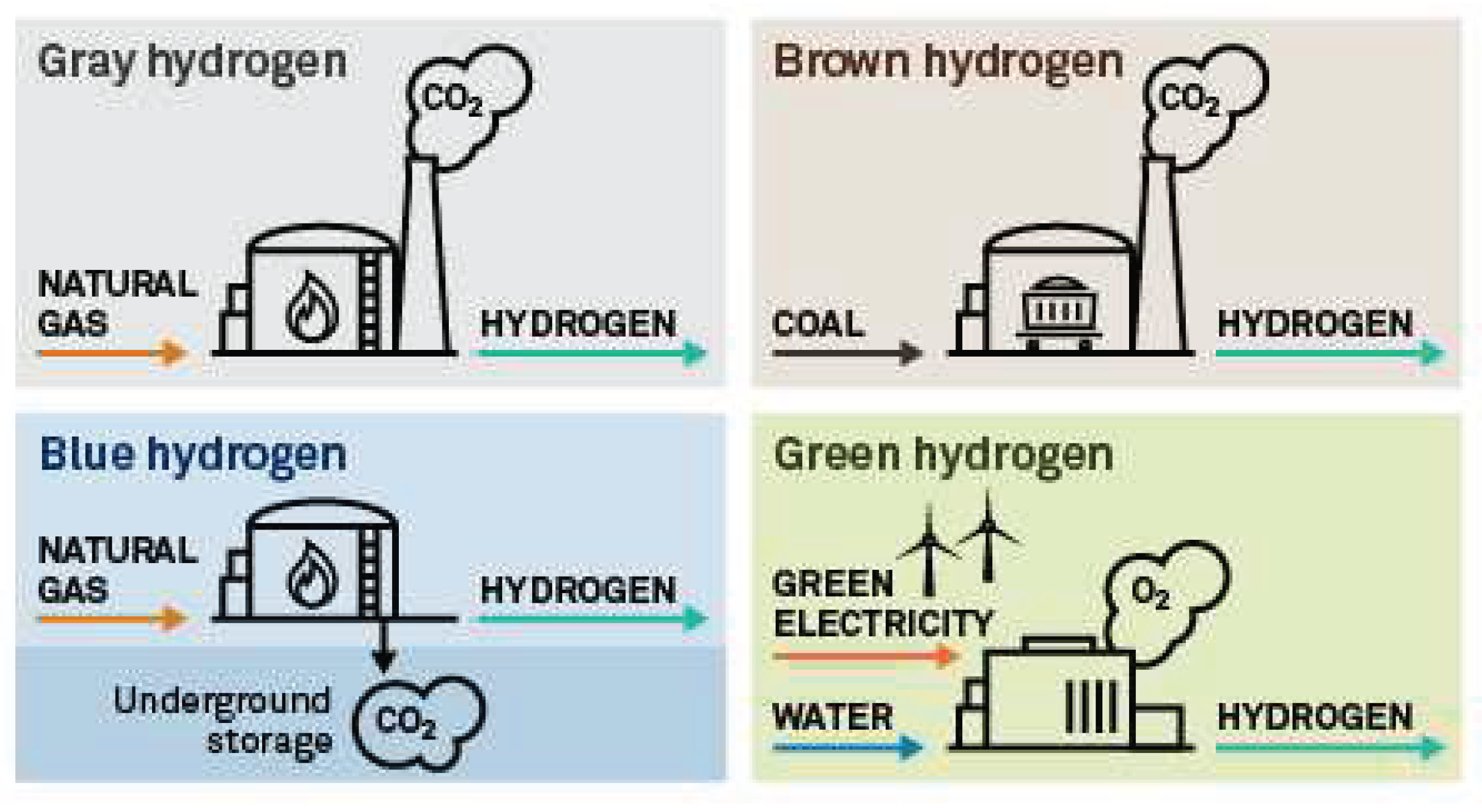

34]. Current hydrogen production in Taranaki is 100% brown hydrogen, which is hydrogen generated from burning coal, but the report acknowledges the potential for large scale blue and green hydrogen [

34]. Currently, with the position of natural gas reserves in NZ, one of the main purposes for the initial production of blue or green hydrogen would be to decarbonize the existing natural gas network but can also be applied to transport, remote or backup energy, export, and much more [

34]. Lastly, the report projects the cost of green hydrogen electrolysis to fall to parity with installing new brown hydrogen generators due to economies of scale and the reduced cost of renewable energy, particularly from offshore wind in Taranaki [

34].

Another large-scale project taking place in NZ regarding green hydrogen is First Gas’ plan to supply the gas through their existing natural gas network. First Gas Limited focuses on natural gas transmission and distribution in NZ and has over 2,500km of high-pressure gas transmission lines, receiving natural gas from Taranaki and supplying it all around the North Island [

41]. They are currently undertaking a three-phase feasibility study, investigating whether they can use their existing pipes alongside the conversion of current equipment. From this study, they aim to have the first commercial pilot project of green hydrogen in NZ which will incorporate the full supply chain, from production to distribution and finally to end users [

41]. The report outlines many benefits of incorporating hydrogen such as avoiding needing to compress the gas for transport, avoiding energy losses and additional costs, and also avoiding truck movement which has multiple safety and environmental implications [

42]. In addition, like Australia, the company wants to create multi-use hydrogen ‘hubs’ which will enable demand across different sectors [

42]. First Gas’s initial target is a 20% blend of hydrogen, then ramping it up to 100% starting in 2035 [

42]. Early findings of the study found that their existing high-pressure, long distance transmission system has the capacity to transport the expected energy demand either blended or pure hydrogen, without significant capacity reinforcement [

42]. Modification costs are estimated to be around NZ

$270 million over the 30-year period to 2050, assuming the electrolyzers will inject hydrogen at high pressures into the network, requiring existing compressors to have to do less, saving on operating costs [

42].

In terms of government support, the Power-to-X report also stated that offshore energy generate currently has no framework that enables or inhibits it, but consideration should be given to develop one to provide stakeholders with certainty, especially when dealing with such large-scale and long-term developments [

38]. To help boost offshore wind and hydrogen in NZ it would require central government support and funding through legislation, targeted projects (green methane), feasibility studies and demonstrations, and more [

38]. Many articles also recommend partnering with international specialized experts to solve logistical issues and apply their experience with more developed projects to ensure that NZ can implement these renewable energy sources in a timely manner to meet their international obligations.

6.1.1. Export

A factor which would pique interest from various parties, and subsequently further develop and invest in projects regarding hydrogen, is its export opportunities. As stated above, NZ, due to its geographical location and favorable negatively correlated seasonal patterns, can possibly be a large exporter of H

2 to Asian countries that do not have adequate renewable potential to satisfy their green hydrogen demands. Countries around the world are looking into producing hydrogen, of which an international spot market is needed in order to truly see if exporting is economically feasible or what the associated opportunity costs from engaging in such activities [

43]. Current H

2 export initiatives are being explored by Brunei and Australia and Japan, but these countries are still using grey hydrogen to test their supply chains, and, in the future, green hydrogen should be used as a replacement to achieve carbon emission goals [

43]. However, some studies have investigated the costs and methods of green H

2 export potential, specifically for NZ, and have provided estimates and scenarios for interpretation.

A study in 2021 from Victoria University of Wellington reviewed the development of an export market of green hydrogen to Japan looking into difference between exports as ammonia or exports as liquid hydrogen. The paper looked into potential for two of the major electricity generators in NZ, Contact and Meridian, to build the world’s largest green hydrogen plant. This opportunity would arise in 2024 with the closure of the Tiwai Point aluminum smelter of which 600 MW of high-capacity energy previously used to produce the metal would be redirected into producing green hydrogen [

44]. It was concluded that large scale imports in Japan would be unlikely before the late 2020s considering that the supply chain that Japan proposes is in very early stages of development with only one LH

2 carrier protype (Suiso Frontier) constructed [

44]. Looking into whether ammonia or LH

2 would be the main type of export, it was noted that each has their own merits. LH

2’s advantages include increased supply chain efficiency, easily meeting the purity levels required for fuel cell applications, lowest energy consumption for formation, and possibly the lowest shipping losses if a supply chain from Bluff, NZ to Yokohama, Japan were to arise [

44]. Conversely, ammonia has the advantage in the short to medium term as there is already existing infrastructure for export of which many parties are familiar with, but the efficiency losses may be extensive if the end-user is to convert it back to hydrogen and not for agricultural purposes as fertilizer [

44].

A report by Contact Energy and Meridian in July 2021 also looked into the two different options of export above and stated that it is currently not clear whether ammonia or LH

2 will be preferred but added onto ammonia’s advantages [

45]. These advantages include that over hydrogen, ammonia’s volumetric density is much better, with a liter of ammonia carrying 50% more energy than a liter of LH

2, or 2.8 times the energy of compressed hydrogen [

45]. Additionally, ammonia has an easier means of storage and transportation, with more versatility for its end-users [

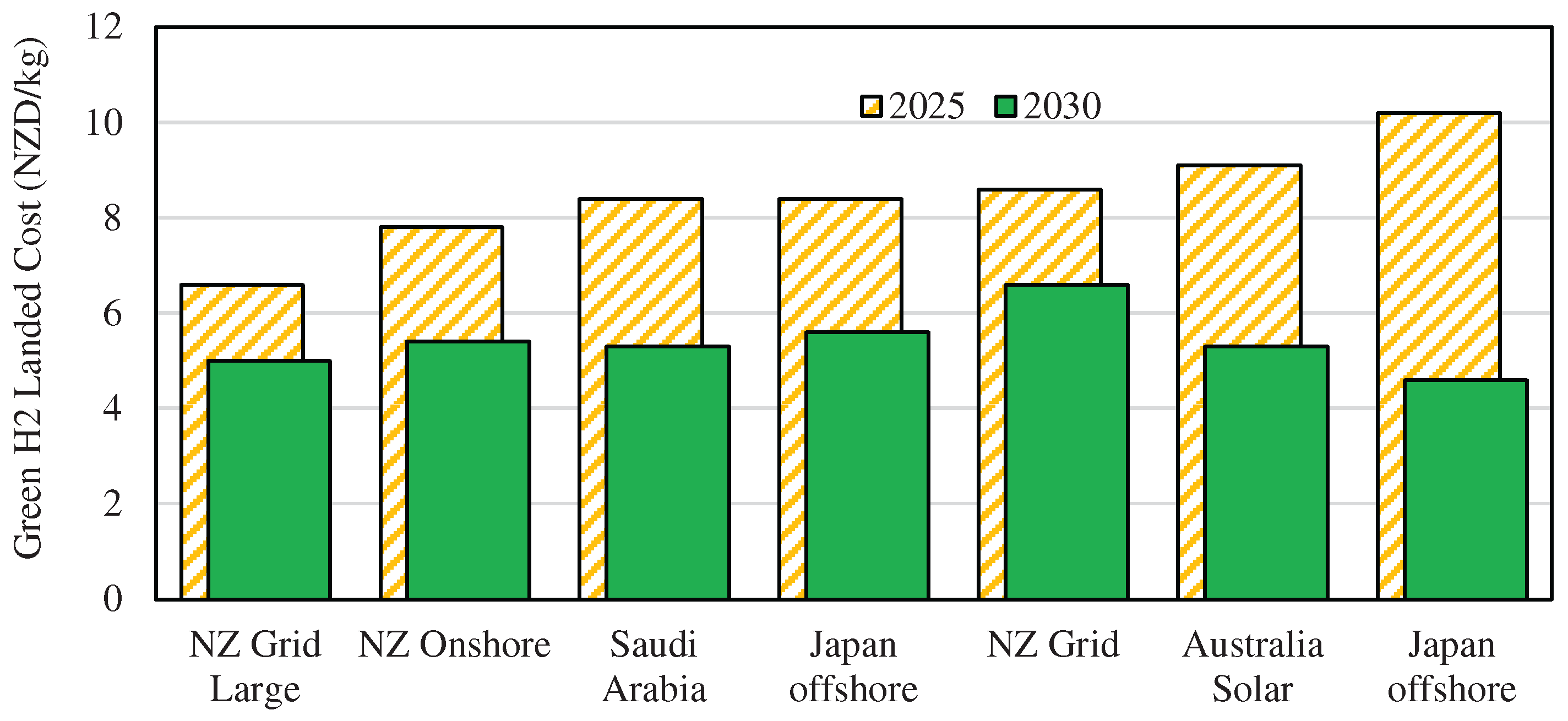

45]. 2030 cost estimates suggest NZ could achieve landed costs of NZ

$5-6/kg (US

$3.34-4.01) of green H

2, with green ammonia costing NZ

$800-830/ton [

45]. Modelling provided in this report show that exports of NZ produced green hydrogen to, for example, Japan would be worth US

$4.30-5.60/kg (NZ

$6.60-8.60) by 2025 [

45]. The report also suggests that at this cost, it would remain competitive against blue hydrogen produced in the Middle East up to 2030 or longer, depending on carbon capture technology and storage costs in that region [

45]. In the long-term, green H

2 from countries such as Chile or Australia from large domestic renewable sources would be internationally competitive, and NZ would need to reduce the cost of its own renewable generation and developments if competitiveness in the export market was desired.

Figure 6 shows the landed (all-inclusive) costs of green hydrogen from multiple sources, of which the graph aims to show that an NZ supply of hydrogen is cost competitive with potential international producers, therefore being an exporter may be feasible.

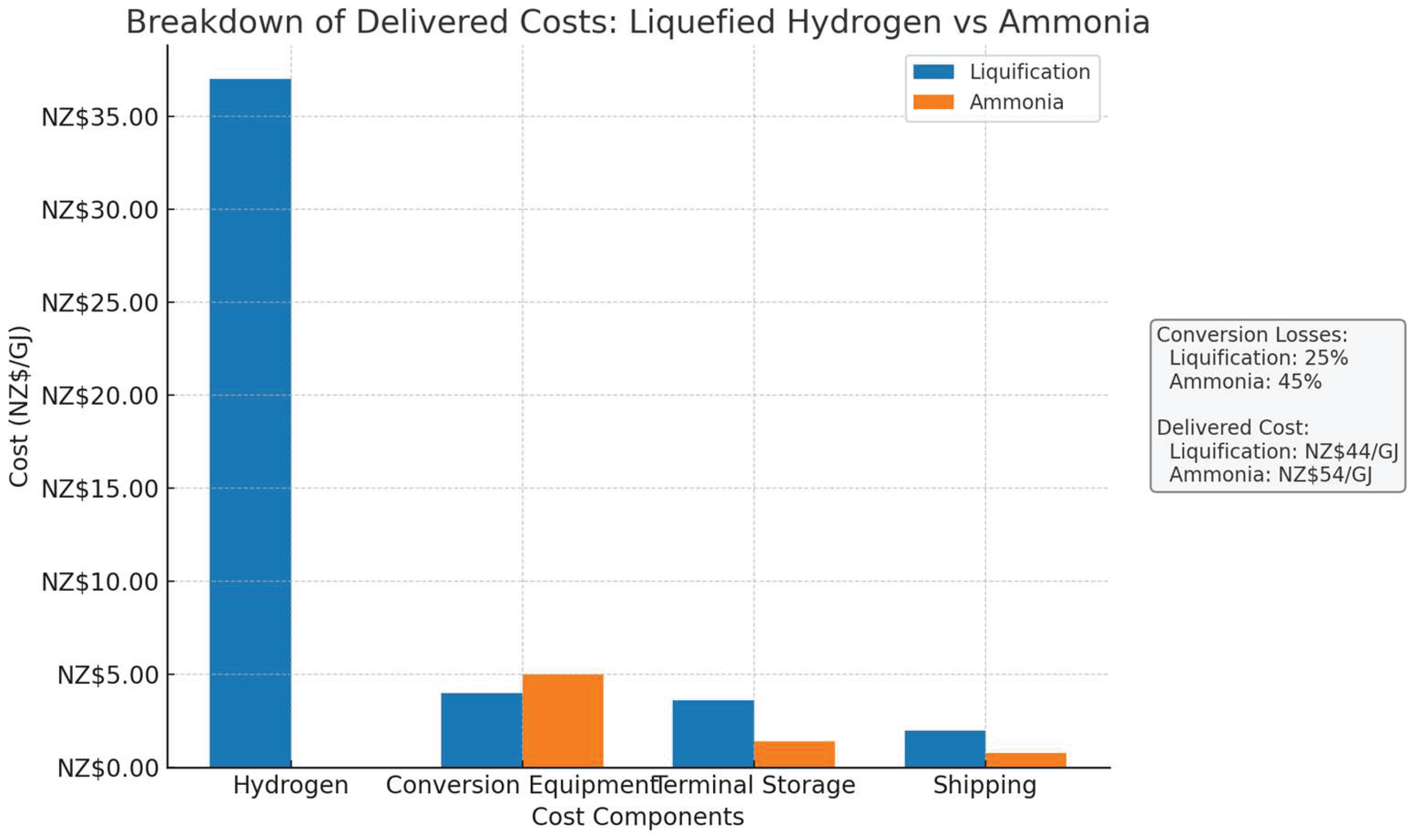

Concept Consulting’s H

2 report shows estimates for hydrogen production after being converted to either liquid H

2 or ammonia.

Figure 7 presents estimates for various contributing factors. LH

2 delivered costs would be NZ

$44/GJ (NZ

$5.3/kg H

2 [US

$3.54]), and ammonia’s delivered cost would be NZ

$54/GJ (NZ

$6.48/kg H

2 [US

$4.33]) [

43]. The economic feasibility of this price depends on alternative sources of these commodities and their respective input prices. Kawasaki Heavy Industries in Japan states that importing hydrogen would be commercially viable if landed costs would be around NZ

$35/GJ (NZ

$4.2/kg H

2 [US

$2.81]), of which Concept notes that their estimate price is comparable with this figure [

43]. Also, current landed costs of liquified natural gas to Japan is approximately NZ

$14/GJ and for NZ

$44/GJ of LH

2 to be economic, a NZ

$550/tCO

2 carbon price would have to be imposed in Japan [

43]. NZ’s current carbon spot price is around NZ

$76/tCO

2 [

46]. The report stipulates that to meet its own decarbonization requirements, before looking at exports, NZ would need to double its electricity generation [

43]. On the other hand, Japan would need foreign renewable generation 125 times greater than the extra generation NZ would need, in order to decarbonize using imported green hydrogen [

43]. Therefore, even with the potential for other nations to be large suppliers of green H

2 to Japan, with lower costs as well, the scale of their decarbonization goals suggests that there would be a market for NZ produced hydrogen. As NZ already has significant penetration into renewable electricity generation, Concept states that NZ could be an ‘attractive partner’ for proof-of-concept trials in potential supply chain and export projects [

43].

6.1.2. Storage

Preliminary studies have assessed the geostorage options of green hydrogen in NZ as the country already has an extensive petroleum infrastructure already installed. There are approximately 2500km of high-pressure gas pipelines, with 17,960km of gas distribution networks, and multiple depleted petroleum fields such as Ahuroa, Kapuni, and Maui [

47]. Geological storage, technology being utilized since the 1970’s, is considered the best large-scale option for hydrogen storage globally, with four types being considered [

47]. These types include: the construction of artificial rock caves, injection into sedimentary rocks, utilization of depleted natural oil and gas caves, and even a study looking at storage in porous and permeable volcanic rocks [

47].

The Ahuroa Gas Storage facility located in central Taranaki stores natural gas from offshore sources until it is needed. Discovered in the 1980s, it was a natural gas reservoir which was largely depleted in 2008, then subsequently converted into a storage facility owned by Firstgas [

48]. Currently, with specific valves and compressors, natural gas is injected and stored until required. Firstgas recently upgraded the capacity at Ahuroa but to make the gas reservoir capacble of storing hydrogen, more investment would be needed, including new compressors which are capable of injecting and extracting hydrogen rather than natural gas [

43]. It is noted in a report by Concept Consulting that Ahuroa is not large enough to meet current demand for dry-year reserves, along with the fact that hydrogen is less energy dense than natural gas, therefore approximately only 1/3 of the energy would be stored by fully filling Ahuroa with hydrogen [

43]. A study by Elemental Group and the NZ MBIE shows potential locations of geological storage in NZ and potential uses for each as shown in

Table 1. These locations were chosen given their proximity to high voltage transmission cables and existing infrastructure for an efficient transition to inject electricity into the grid when needed through fuel cell technology.

Other studies overseas state that there is also potential reservoir leakage due to hydrogen being a smaller molecule than natural gas, adding onto energy losses [

43]. Therefore, using this specific reservoir would only be a partial solution and more options would be needed for that future.

Other means of storage and transportation of hydrogen include:

Ammonia (material-based storage), as the costs of storing and transporting this chemical are much cheaper than storing H

2 itself. However, there are significant efficiency losses associated with this process as electrolyzer generated hydrogen would be converted into ammonia, then back to hydrogen when it is needed for power generation [

43]. Whilst electrolyzer energy losses could be as low as 25%, the conversion and reversion will increase energy losses to 59% [

43]. Therefore, storage and transportation of hydrogen as ammonia may present higher costs relative to using a natural gas reservoir such as Ahuroa. Currently, NZ only has one ammonia-urea manufacturing plant located in Taranaki, converting atmospheric nitrogen and hydrogen into ammonia, then subsequently to urea, both of which still have carbon emissions due to natural gas usage in the process [

33]. There is an established export market for ammonia, and it could be essential as a near-term means of storage and transportation as established processes make it easier for a transition into a hydrogen economy.

Compressed H2, by using specific compressors and stored in tanks. The volume of hydrogen is almost four times as large as natural gas, therefore, H2 needs to be compressed for practical purposes [50]. Also, FCEV uses highly compressed hydrogen and therefore if this was the main end-user application, then it will be beneficial to have the gas compressed and stored in this form after production [50].

Liquified H2, if further compression of the gas is required. The current Japan-Australia hydrogen supply chain tests are using liquified hydrogen as the carrier method for overseas shipment but the process of liquifying and storing it is very complex and costly. As mentioned above, hydrogen liquifies at -253°C and needs to be stored in insulated tanks for minimal temperature and evaporation losses [50]. Economies of scale may make liquefaction more feasible in the future.

Overall, to combat dry-years and include inter-seasonal hydrogen storage, further research is required for potential sites of geological reservoirs in NZ, and some studies have focused on areas around proposed renewable energy and hydrogen generation, but it may be needed to expand this criterion to sites nationwide. It is evident that for a wide range of purposes, different means of storage and transportation may be required, and it will be imperative to know which is most efficient for specific purposes.

6.3. Costs

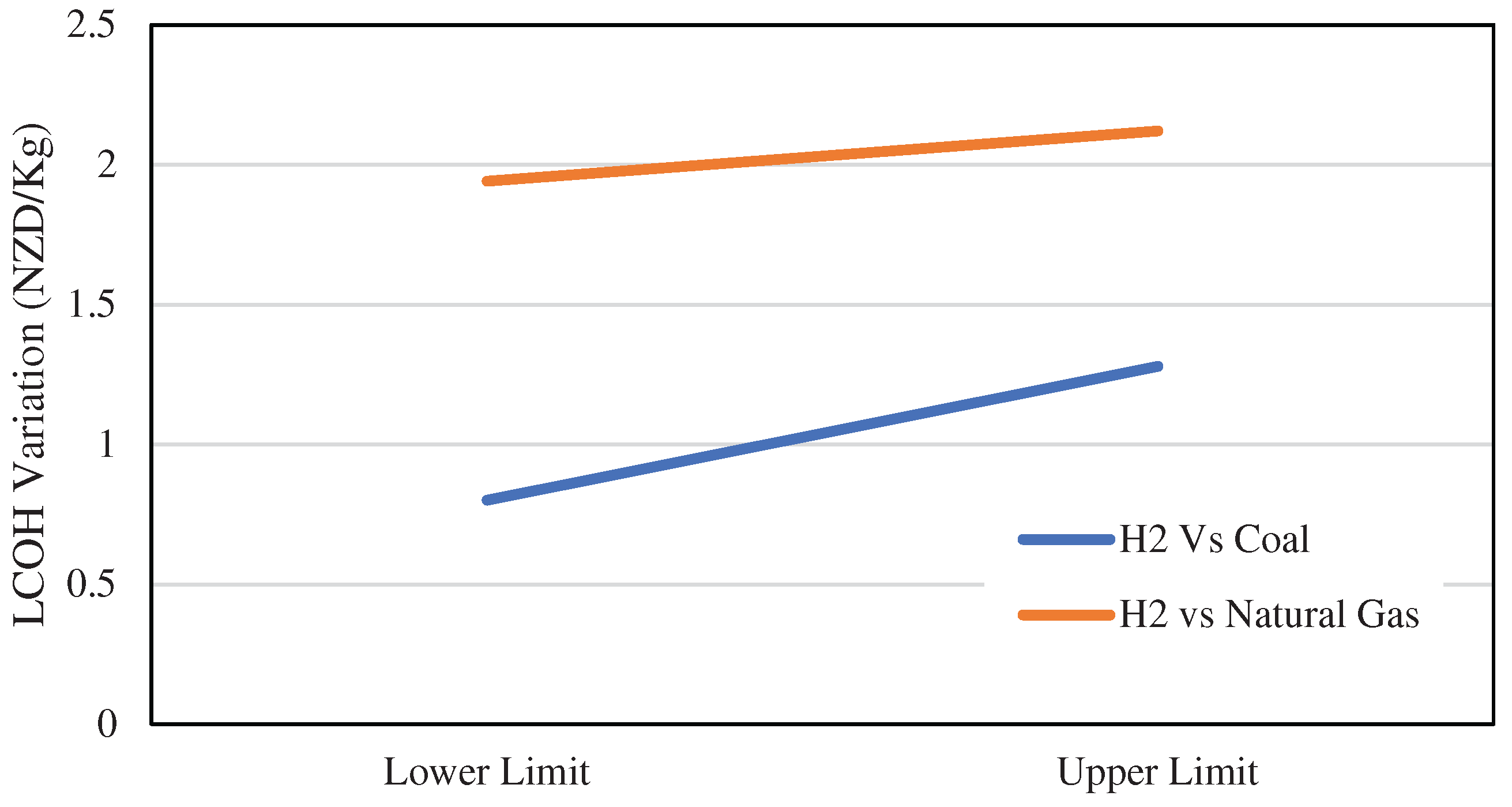

An ideal scenario for using renewable energy for green hydrogen in NZ is to connect electrolyzers to the electricity distribution grid for peak utilization as grid power is not intermittent unlike most renewable sources. An assumption for this, however, is that renewable electricity will reach a certain capacity, where it is certain that the hydrogen produced from the grid will still be green. The aim is to produce hydrogen in times of low industry and household demand to take advantage of surpluses in electricity supply. This way, the minimum electricity input costs (of which has the most impact on H2 production costs) are effectively close to zero because otherwise the excess electricity generated from renewables would just go unused. At a maximum, a hypothesis for the cost estimation of electricity input would be how much it costs to add new electricity capacity to the grid as mass produced hydrogen would likely only be feasible once costs and economies of scale of renewable energy are prevalent. This section analyzes modelling done by Concept Consulting that investigates the cost estimates of a similar plan, including other scenarios. In addition, these figures will be compared with other pieces of literature, including modelling done by NZ’s Ministry of Business, Innovation, and Employment (MBIE) and Castalia, for the future hydrogen supply and demand. As each piece of modelling assumes different scenarios and accounts for different variables, it would be unfair to simply compare them side-by-side. However, it is interesting to compare and note estimated variables such as wholesale electricity costs and the range of final cost projections produced by each model.

Concept’s core model assumes that green hydrogen will be produced through a grid electricity distribution network using electrolyzers, then compressed, and lastly, stored in bulk. The model looks at the all-inclusive costs of doing so, including components such as wholesale electricity, network costs, efficiency losses throughout the process, CAPEX, storage, and OPEX costs. The electrolyzer utilization factor estimated is 85%, and is relatively high when compared to Castalia’s modelling as its base case in 2020 shows an electrolyzer utilization factor of 41.5% ([

43];[53]). The electrolyzer utilization factor is the ratio of the demand that the electrolyzer is in use relative to the total time that it could be in use [52].

Castalia’s model identifies key variables that affect the estimated future levelized cost of green hydrogen production, demands for the gas, CO

2 emissions reductions, and includes an indicator of what role hydrogen is likely to play in the NZ economy. This model accounts for variables such as electricity costs and electrolyzer utilization factors in NZ and internationally, natural gas and diesel price changes, and even the percentage that hydrogen can be blended into the existing gas network, among others. Given all these variables, the model agrees that the levelized cost of hydrogen is most sensitive to wholesale electricity costs [53]. Some figures represented in the base case are a NZ

$61/MWh electricity cost for 2020 with a -0.25% expected annual decrease in prices both in NZ and internationally, whereas Concept estimates a NZ

$75/MWh current (2019) and future (2039) electricity cost [

43,53]. A separate report by MBIE in 2019 on electricity demand and generation scenarios projects wholesale prices in 2050 to stay the same in real terms, incorporating the assumption that majority of new electricity generation is from wind power, with its long-run marginal cost projected to fall over the projected period [54].

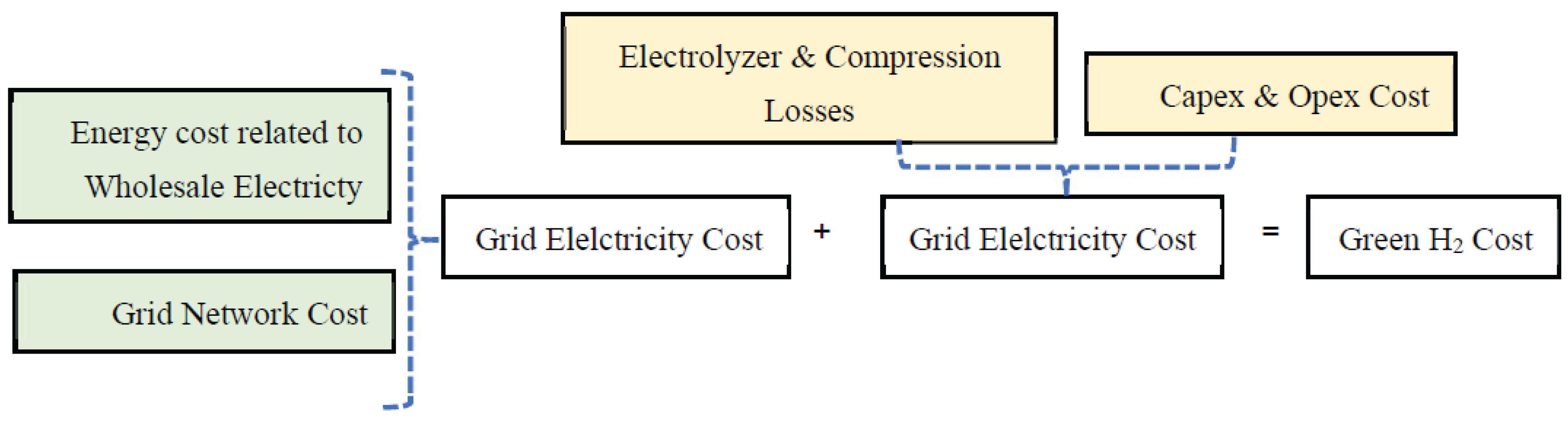

Figure 9 breaks down the factors considered in calculating the cost of green hydrogen.

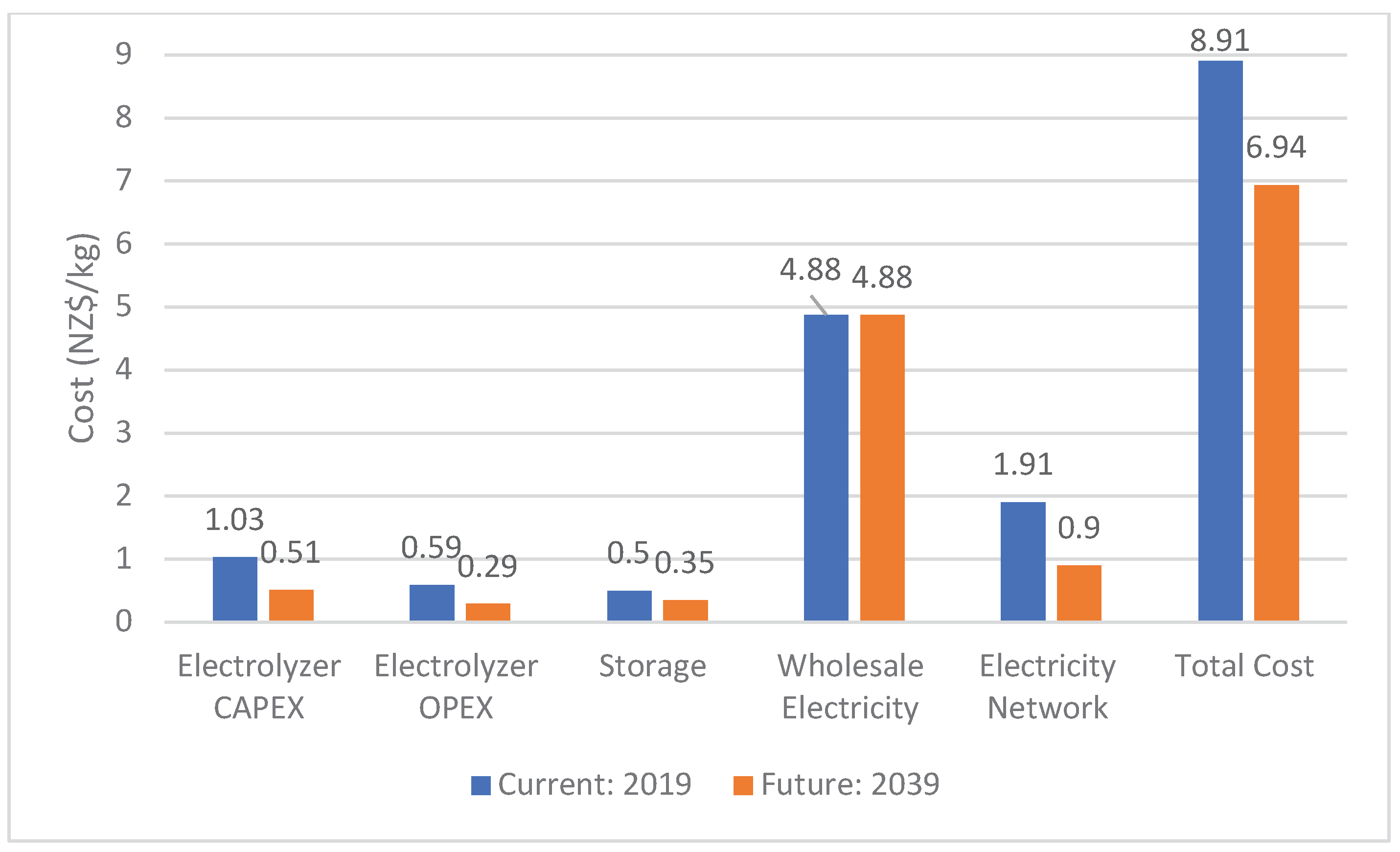

Figure 10 further shows the breakdown cost of current (2019) and future (2039) hydrogen production. Concept reports an estimated NZ

$8.91/kg H

2 (US

$5.95) current production costs and NZ

$6.94/kg H

2 (US

$4.64) in 2039 of which is relatively high, compared with estimates from other literature. Castalia’s base case estimates that the levelized cost of hydrogen currently (2020) is US

$3.83/kg H

2 (NZ

$5.72) and in 2039, around US

$2.68/kg H

2 (NZ

$4) [53].

It is not clear whether Castalia had accounted for some of the costs that Concept had, but the difference is significant given the fact that for hydrogen to be an economical fuel source for the future, the cost needs to be driven as low as existing widespread fuel sources such as fossil fuels.

Concept Consulting also provided modelling for alternative uses of hydrogen potentially to alleviate some of the larger costs stemming from hydrogen storage.

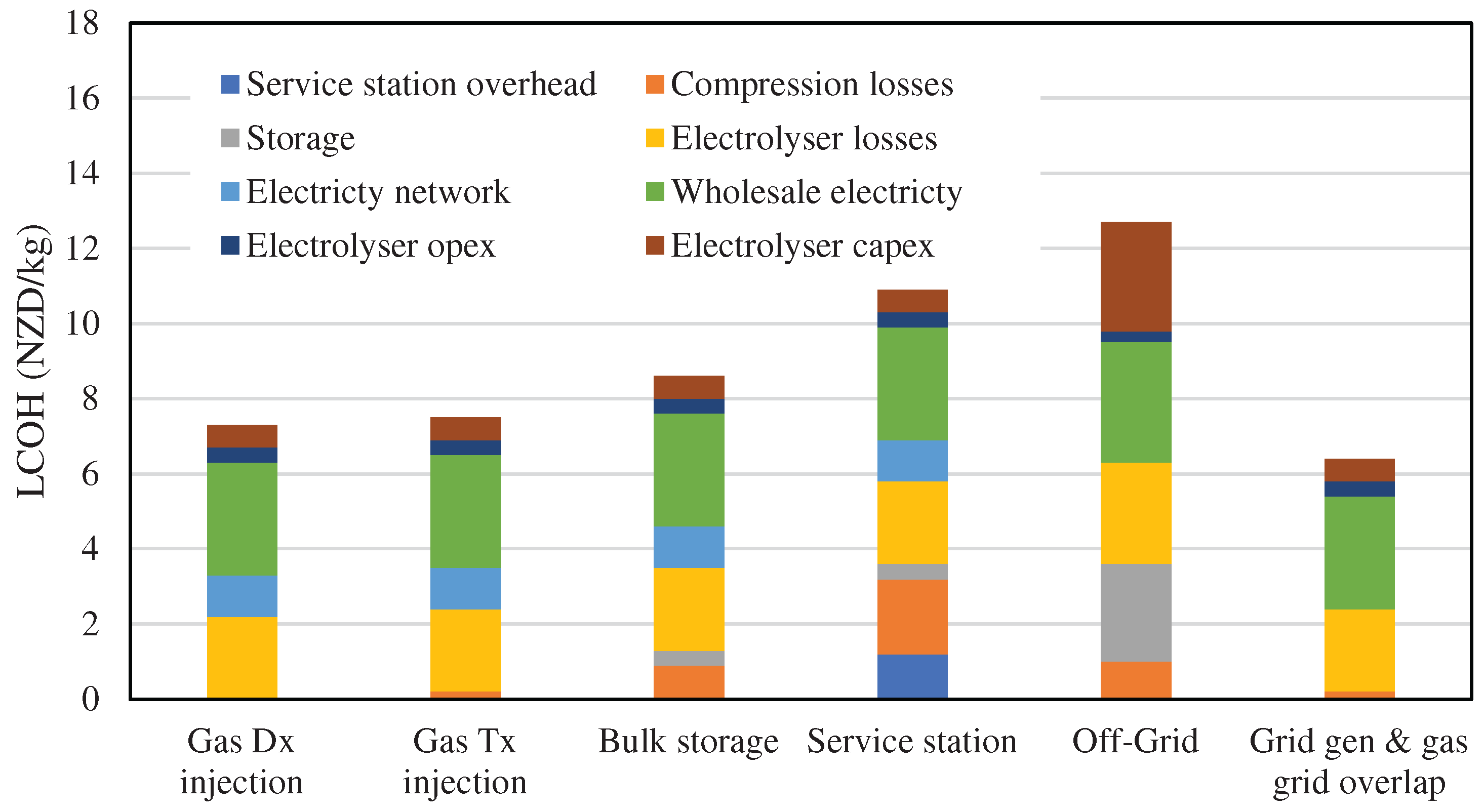

Figure 11 shows the key variables influencing hydrogen production costs and includes justifications for why certain costs are relatively large or small. One example that avoids storage costs is P2G. However, it is worth noting that the model does not account for end-user transportation costs, which may increase total costs.

Two types of P2G scenarios include Gas Dx injection and Gas Tx injection. The differences between the two are that Dx injection goes directly to the gas distribution network, avoiding compression losses, whilst Tx injection going to the gas transmission network and has compression losses [

43]. Compared to the bulk storage scenario, compression losses are halved, including other assumptions such as lower electricity network costs, less electricity distribution losses, and lower electrolyzer costs from an assumed larger scale production facility. A caveat with Tx injections is that it may be hard to control hydrogen concentrations to a regulated and safe level if the large scale H

2 production is being injected at a single point [

43]. This problem may be alleviated by co-locating natural gas and hydrogen production, which could be done in, for example, in Taranaki, or by using dedicated pure hydrogen pipelines. Other options include:

Service stations: For uses in fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEV), where high compression is needed, leading to double compression losses compared to bulk storage. This also includes service station overhead costs, similar to building a petrol station.

Off-grid: Similar to the bulk storage case but avoids network costs as hydrogen is produced with an off-grid energy supply. A caveat to this, however, is that it will incur large storage costs and lower electrolyzer utilization factors. Lower utilization factors are due to the intermittent nature of renewable electricity supplied compared to using grid electricity, leading to larger capital recovery costs per kg of produced H

2. In

Figure 10, an assumed utilization factor for this scenario is based off solar generation which is much lower than that of offshore or onshore wind. Also, this scenario may lead to higher wholesale electricity costs if local renewable generation is not able to achieve the same economies of scale and grid generation. Currently, if we were to apply the cost of generating more MWs from offshore wind as the electricity cost variable, it would be uneconomical as offshore wind is very expensive. However, in the future if projections for lower offshore wind costs are to be realized, this method may become more cost effective, given the higher electrolyzer utilization factors associated with this type of renewable generation. Concept’s assessment, however, is that the cost effectiveness of off-grid method is only realized when the electricity network costs from connecting to the grid are higher than what is shown in

Figure 11 [

43].

Grid-gen & gas-grid overlap: Similar scenario to Gas Tx injection, however, in this case the grid connected renewable energy generators are located close to a gas transmission line. Additionally, with an electrolyzer placed behind the renewable generation plant, incremental electricity network costs can be avoided. This scenario is cost effective and is evident as in

Figure 10 this gives the lowest hydrogen production costs compared to the other scenarios. Possibilities for this method in NZ would be in, for example, Taranaki, where established gas transmission lines and potential for large renewable generation is in the same proximity.

Other studies have looked specifically into the economic viability of combing hydrogen production specifically with onshore and offshore wind energy, and produced cost estimates based off case studies, of which would be most similar to the off-grid scenario:

One study investigated the potential of green hydrogen production from wind-generated electricity in Pakistan using 660kW wind turbines and results concluded that production costs of green hydrogen were US$4.304/kg H2 (NZ$6.48), with supply costs withing a range of US$5.30-5.80kg/H2 (NZ$7.98-8.73) [55]. These estimates included costs such as CAPEX, storage, configuration, OPEX, water supply, and even considered the selling price of oxygen to offset some of the costs. They reported that at the four sites the examined in Pakistan, 10.5 tonnes/day of hydrogen can be produced, with potential for optimization in summer when country wide electricity demand is lower [55].

A study conducted in Ireland looked specifically at offshore wind in their country with their case study comprising of a hypothetical 101.3 MW total capacity on Ireland’s East coast. Their model considers a specific type of electrolyzer (PEM), varying wind speeds in the area, electrolysis plant size, wind power out, and includes cost-effective underground means of storage. They concluded that the farm would be profitable at €5/kg H2 (NZ$8.48 [US$6.76]) (with all estimated variables using 2030 costs from various literatures), with underground storage potential ranging from 2 to 45 days with the latter becoming less economical due to the larger capital costs associated with underground storage [56].

Referring back to

Figure 11, to achieve lower costs in each scenario, wholesale electricity prices must decrease in order to be competitive with existing fuel options. This may be possible with high penetrations of wind, solar, and geothermal energy in the future, which will lead to periods of surplus energy in order to collapse electricity prices. Concept also incorporates electricity network costs and suggests that to lower these costs, end-users who can avoid peak time consumption should be rewarded with lower costs to achieve lower network bills [

43]. However, with these costs falling, other ones arise. With the level of demand for hydrogen to increase one it becomes economical; production facilities would require larger electrolyzers and storage to meet this demand. These higher capital costs are spread over a smaller amount of hydrogen produced, which means that per-unit costs will be higher [

43]. This effect may be mitigated if technological advancements reduce CAPEX costs of both electrolyzers and storage.

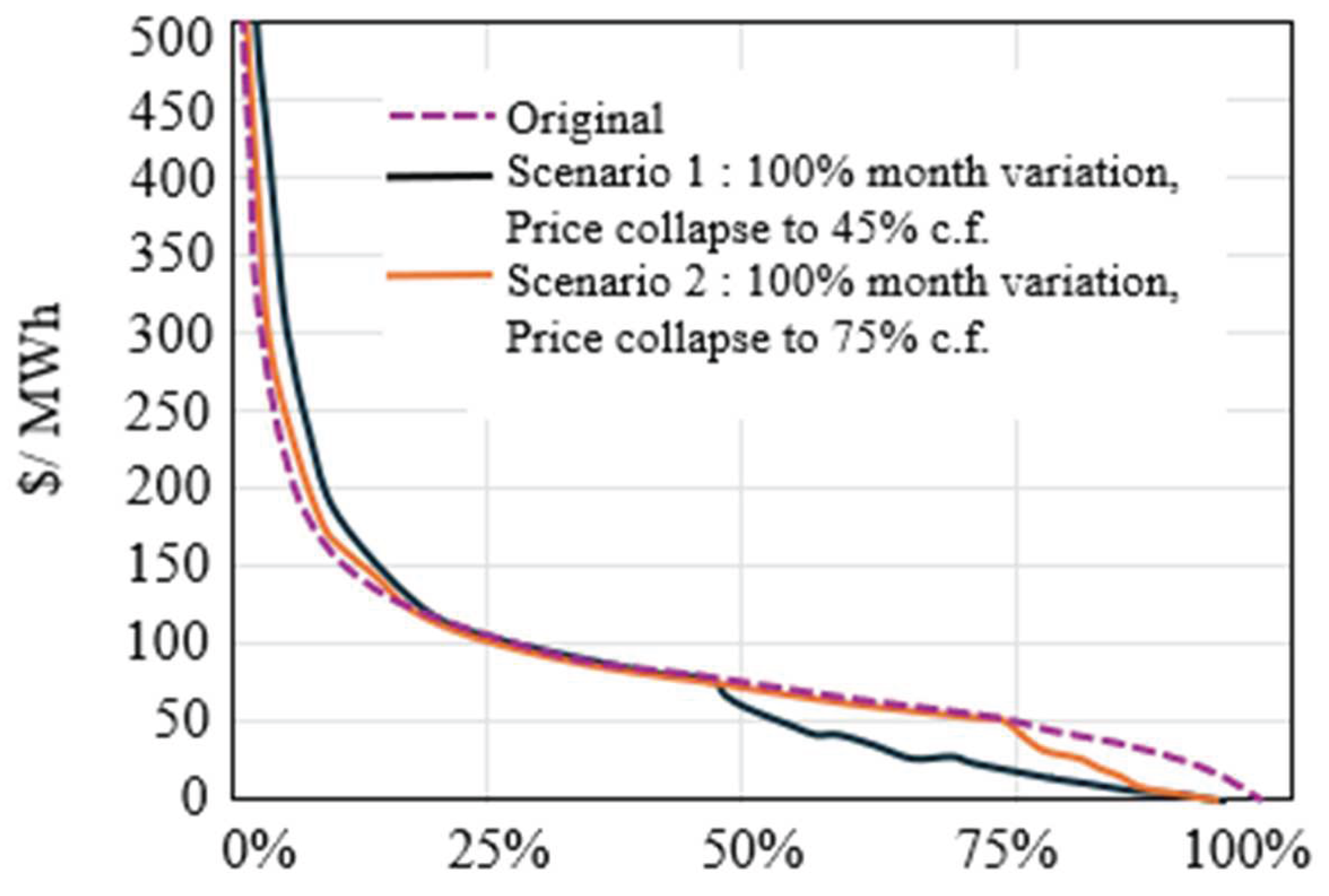

The report by Concept also analyzes the impact that renewable penetration has on wholesale electricity prices and how they arrived at their cost estimate in

Figure 12. The model provided in

Figure 11 shows potential future electricity prices given NZ’s current renewables mix and a change to higher proportions of renewables, accompanied by high carbon prices in the future. With higher penetration of renewables there may be periods of lower wholesale electricity prices due to surplus production, which are also offset by times of scarce supply, which is how Concept reached their time weighted average wholesale cost of NZ

$75/MWh, stating that this is the level that is ‘required to support new baseload generation’ [

43]. The reduction in electricity prices can be attributed to the merit order effect, which suggests that integrating large-scale renewable energy sources such as wind and solar into the grid lowers electricity prices by prioritizing these low-cost generation options [57].

Figure 12 shows the price-duration curves for current mix (Original), high renewable penetration causing a price collapse of 25% of the time (Scen 2) and high renewable penetration causing a price collapse 55% of the time (Scen 1). Price collapses occur with major surpluses in electricity supply, so it is pivotal for renewable generation to exceed projected electricity demands in the future.

Figure 12 shows that in both scenarios with high renewable penetration, price collapses allow wholesale prices to fall below NZ

$50/MWh. This is significant as Lazard estimates that the unsubsidized LCOE for gas combined cycle generation is between US

$44-73/MWh (NZ

$65.85-109.26) ([

29] Lazard, 2020). This shows that a future with high renewable penetration can be potentially cheaper and will be environmentally friendlier than using natural gas in NZ. It is important to note that this modelling assumes small scale hydrogen production, potentially for use in decarbonizing certain sectors (not for export), as it assumes that the increased electricity demand from using the cheaper electricity to produce hydrogen does not reduce the surplus to the extent that the price collapse does not occur. If a future strategy is to use the surplus electricity to minimize H

2 production costs, then there should be an incentive to dramatically increase new renewable generation for a large surplus to occur, for larger scale production purposes.

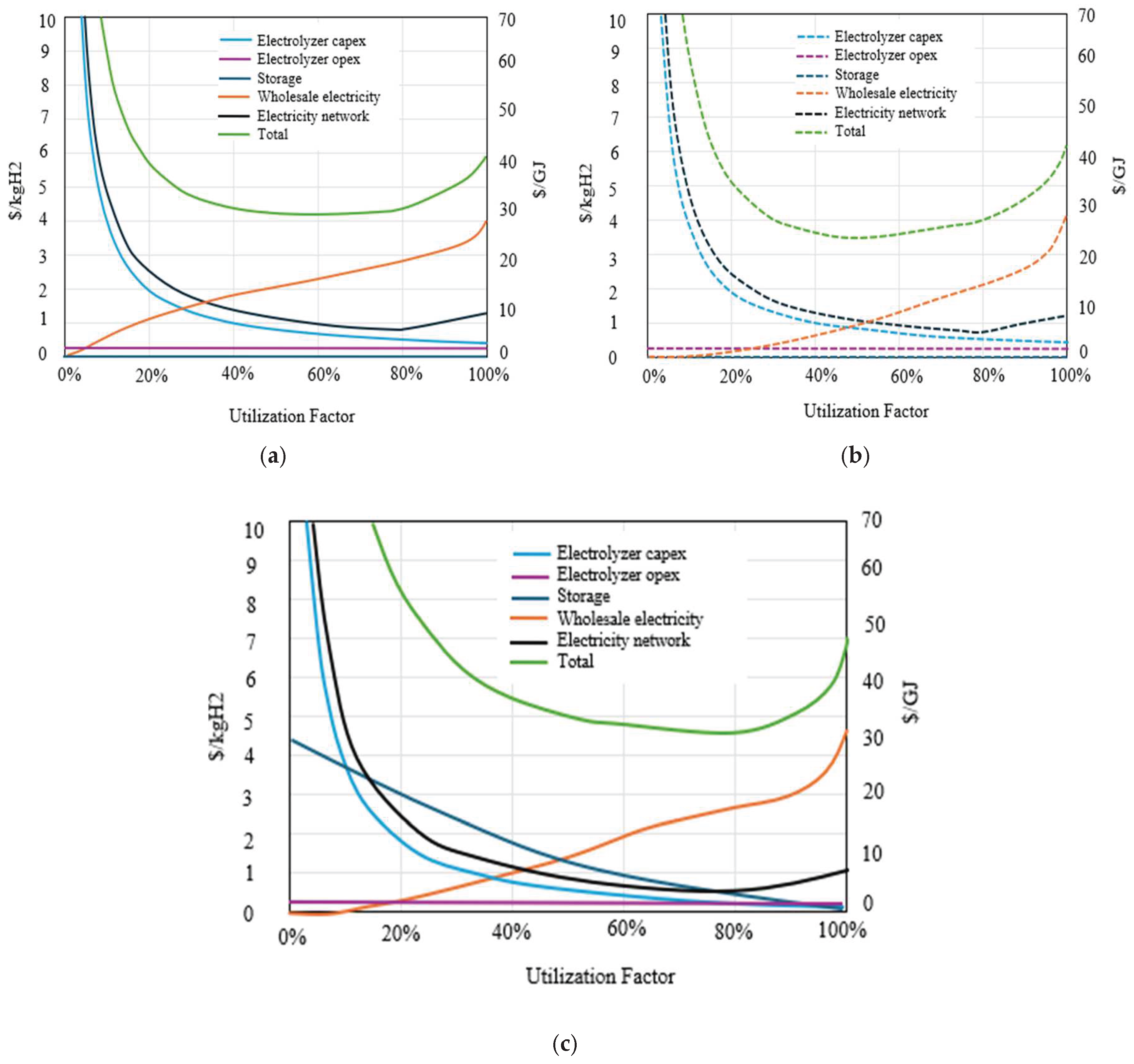

The case of high renewables penetration is reiterated with modelling comparing P2G scenarios with varying levels of renewable energy. The two P2G scenarios in

Figure 11 (Dx and Tx injection) are two of the least costing strategies as storage costs are eliminated. Figures 13a,b show the modelled future hydrogen production costs for P2G, with

Figure 11 showing costs with current levels of renewables, and

Figure 13b showing an opportunistic high renewables penetration. From these graphs, it is evident that the average per unit cost of hydrogen production is lower at sites operating with higher renewable energy utilization. Specifically, the cost is approximately NZ

$1/kg cheaper—about NZ

$4/kg as shown in

Figure 13a compared to NZ

$3/kg in

Figure 13b. This shows that renewable penetration has a significant impact on the H

2 production costs. Due to trade-offs between wholesale electricity costs and higher capital and network costs, results in the shape of the total cost curve showing little cost variation between operating at a wide range of electrolyzer utilization factors. Concept notes that the price for opportunistic P2G production is similar to an estimate provided by the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization (CSIRO) for future estimates for H

2 production in Australia [

41]. When looking into large-scale hydrogen uptake and production, costs will increase significantly. This scenario is where the assumption for small-scale production is likely to collapse and wholesale electricity price collapses might happen less frequently or not at all, leading to higher costs. This is also on top of the added storage costs if the goal was to provide intra-day or inter-seasonal storage to alleviate dry-year demand.

Figure 13c shows how storage costs play an important role in this cost estimation and it is interesting to see how the wholesale electricity cost component curve increases more than

Figure 13b at still relatively low utilization factors. This suggests that the trade-offs between lower wholesale prices with higher capital, storage, and network costs lead to an optimal utilization of around 80%, at which the average per unit cost of hydrogen production is approximately NZ

$5/kg.

Minimum costs are approximately almost NZ$2/kg H2 more than P2G with high renewables, however, this price is similar to other cost estimates in other studies and whether this future price will be economical depends on multiple variables such as the future prices of natural gas and carbon taxes.

Hydrogen should be deployed strategically, prioritizing sectors where it offers the greatest decarbonization benefits. Otherwise, the energy system will face significantly higher renewable generation requirements due to the substantial energy losses associated with using hydrogen for transport or heating, compared to direct electrification options [

43]. These losses arise from firstly converting electricity to hydrogen, and secondly from FCEV, hydrogen fueled boilers and heaters having lower efficiencies that electric powered ones. Due to hydrogen’s energy density, almost three and two times as much renewable energy is required to power a FCEV and industrial process heat, respectively, relative to its electrical versions [

43]. It is also stated that building more generations with have a positively correlated effect on wholesale electricity prices. Concept projects an average price increase of almost 10% in a scenario where hydrogen-based decarbonization is the driver for renewable development [

43]. This emphasizes that hydrogen alone will not fix dry-year and electricity demand problems, but to decarbonize the NZ economy, there needs to be a careful combination of direct electric-based and for some sectors, hydrogen-based, depending on optimal efficiencies sustainable practices.

From a regulatory perspective, the New Zealand government has actively engaged in designing a framework that addresses the specific needs and challenges associated with offshore wind and hydrogen production. The Offshore Renewable Energy Bill in New Zealand establishes a legislative regime to govern the construction, operation, and decommissioning of offshore renewable energy projects, including wind farms [58]. Introduced to Parliament in December 2024, the Bill aims to fill gaps in the existing legislative framework by providing the necessary certainty for potential developers to invest in offshore renewable energy. This includes setting standards for environmental protection, stakeholder engagement, and ensuring that these projects align with New Zealand’s long-term energy needs and its commitment to transitioning to net-zero carbon emissions by 2050. The Bill is part of a broader strategy to harness New Zealand’s significant offshore wind resources and enhance the country’s energy security and sustainability. Concurrently, the Hydrogen Action Plan, released by the Ministry of Business, Innovation, and Employment in December 2024, outlines the steps the government is taking to support the development and integration of hydrogen technologies into the country’s energy system [59]. This plan is part of New Zealand’s broader goal to transition to a low-emissions economy and highlights hydrogen’s role in decarbonizing hard-to-abate sectors, enhancing energy security, and supporting economic growth through innovative energy solutions. However, this framework should also consider the integration of both emerging technologies.