1. Introduction

Alopecia areata (AA) represents an inflammatory, non-cicatricial type of hair loss disorder, with a lifetime risk of approximate 2% worldwide. AA is considered the most prevalent autoimmune disorder and the second most prevalent hair loss disorder [

1]. In 75% of patients, the disease is limited to the scalp, even though it can affect every part of the body; typical lesions usually appear as single or multiple patches, but specific clinical patterns can be found, such as ophiasis, sisaipho, total scalp hair loss, alopecia totalis and alopecia universalis [

2]. AA represents a chronic relapsing condition that can have considerable effects on the patients’ quality of life, correlated with illness severity [

3].

Psoriasis is a long-term recurrent systemic inflammatory condition affecting the skin and/or joints, with a reported prevalence ranging from 0.09% to 11.4% [

4]. Dry and raised plaques on the skin are the most common sign of disease, while enthesitis and marginal bone erosions of peripheral and axial skeleton represent joint signs [

5]. Given the significantly debilitating nature resulting from joint involvement, especially if left untreated, and the considerable aesthetic impact that particularly severe cutaneous forms can provoke, psoriasis can often lead to a significant deterioration in the quality of life of affected patients.

Psoriasis disease can be associated with various comorbidities, including metabolic disorders, an increased risk of cardiovascular diseases, anxiety and/or depression, and other autoimmune conditions, such as AA, a chronic autoimmune and infiammatory disorder at the hair follicle level [

6].

As reported in a recent study, the pooled prevalence of AA among patients with psoriasis was 0.5%, whereas the pooled prevalence of psoriasis among patients with AA was 2.5%. Jung and colleagues considered the degree of bidirectional association in younger participants to be “noteworthy”, and found that patients with psoriasis, regardless of age, had significantly higher odds for AA and vice versa [

6].

The causal link between these two pathologies does not seem to be fully elucidated, but they certainly show clinical affinities, such as to cause a form of non-scarring cicatricial alopecia with preservation of hair follicle unit. Recent articles on patients with concurrent psoriasis and AA describe normal hair regrowth in areas of skin with plaque psoriasis, offering information on the immune factors underlying each disease [

7]. Furthermore, many of the same therapies, e.g. topical or intralesional, or systemic steroids, are used to treat both diseases emphasizes both their overlapping characteristics and the lack of targeted therapy.

Because traditional therapies are not sufficiently effective and are burdened by serious side effects, new therapeutic modalities must be explored. Janus kinase inhibitors (JAKi) represent a new class of medications that act by selectively or non-selectively inhibiting the Janus kinase (JAK) - signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) signaling pathway, involved in the pathogenesis of numerous inflammatory diseases. Baricitinib is a selective and reversible inhibitor of JAK1/JAK2, already used as a therapy for rheumatoid arthritis and recently approved by the FDA for the treatment of moderate-to-severe AA in adult patients, with satisfactory results reported in the literature [

8,

9].

The JAK-STAT signaling pathway regulates the activity of numerous cytokines, including interleukins (IL)-17 and -23, which play a central role in the pathogenesis of psoriasis [

10,

11], as consequence JAKi could also represent a valid therapeutic alternative in psoriasis disease. Currently, two JAKi are approved for psoriasis: Upadacitinib, indicated for the treatment of Psoriatic arthritis (PsA), and Deucravacitinib, indicated for moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis affecting the skin only. However, cases of paradoxical psoriasis induced by baricitinib have been reported in the literature, which makes it necessary to gain more experience in the use of these drugs in plaque psoriasis [

12].

We report our experience with patients affected by severe AA and concomitant psoriasis and/or psoriatic arthritis, treated with baricitinib 4 mg/day.

2. Materials and Methods

We enrolled 5 patients (2 males, 3 females; mean age 53.2 years) from the Dermatology Unit of Policlinico of Tor Vergata, Catholic University of the Sacred Heart and La Sapienza University of Rome, Italy. All patients were affected by a severe form of AA with concomitant cutaneous and/or articular psoriasis (1 patient with plaque psoriasis, 1 patient with guttate psoriasis, 3 patients with psoriatic arthritis, PsA). Reported comorbidities included arterial hypertension, type II diabetes mellitus, and hypothyroidism.

All patients had previously received conventional therapies for AA, including topical and/or systemic corticosteroids and cyclosporine, without significant benefits. Among them, the three patients with PsA had undergone treatment with conventional synthetic and biological Disease-Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drugs (csDMARDs and bDMARDs), specifically Ixekizumab (two patients) and Brodalumab (one patient). While these treatments provided partial or complete control of joint symptoms, they had minimal impact on AA. The two patients with only cutaneous psoriasis had been managed with cycles of local corticosteroid therapy, achieving satisfactory disease control.

AA assessment was performed through clinical evaluation, using the Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT) score, and dermoscopy, with the Dermaview digital dermoscope and DL200 Hybrid dermoscope (Dermlite, San Juan Capistrano, CA, USA), at a magnification of x10. SALT score describes the percentage of scalp hair loss and ranges from 0 to 100. A SALT score of 100 means complete (or 100%) scalp hair loss, while limited (mild) hair loss representing 1-20% scalp involvement, moderate hair loss representing 21-49% scalp involvement and severe hair loss representing 50-100% scalp involvement [

13].

Psoriasis assessment was performed using the Psoriasis Area Severity Index (PASI), ranging from 0 (no psoriasis) to 72 (extremely severe psoriasis), for the cutaneous component and the Pain Visual Analogue Scale (pVAS), patient-reported pain level, measured on a visual analog scale ranging from 0 to 10 cm, for the articular component.

The three patients previously receiving biological therapy discontinued their treatment and completed an appropriate washout period before initiating baricitinib. Following instrumental and hematological screening, baricitinib was started at a dose of 4 mg/day. Patients were evaluated at baseline and subsequently at 1 month (Week 4), 6 months (Week 24), and 12 months (Week 52) of therapy.

3. Results

In our cohort two patients were affected by a severe form of AA with a SALT score >80 and 3 patients with a form of AU (SALT score>100). At baseline, mean SALT (mSALT) score was 83, while a good control of the psoriatic disease was observed, with a mean PASI (mPASI) of 1.4 and mean pVAS of 0.

At Week 4, 2 patients exhibited partial clinical remission of AA, while in 3 patients, clinical stability was observed with a marked improvement on trichoscopic evaluation, with vellus hair and other signs of regrowth in the affected areas. The mSALT after one month of treatment was 57. No significant changes were observed in cutaneous or articular psoriasis.

At Week 24, one of the patients with PsA spontaneously decided to discontinue therapy due to the lack of evident clinical results on AA, despite improvements observed on trichoscopy and despite no cutaneous or articular exacerbation of the psoriatic condition was observed. In the remaining 4 patients, clinical improvement of AA was observed (mSALT 22.5), with one of the AU group patients achieving a complete clinical remission (SALT 0). Psoriasis condition remained stable.

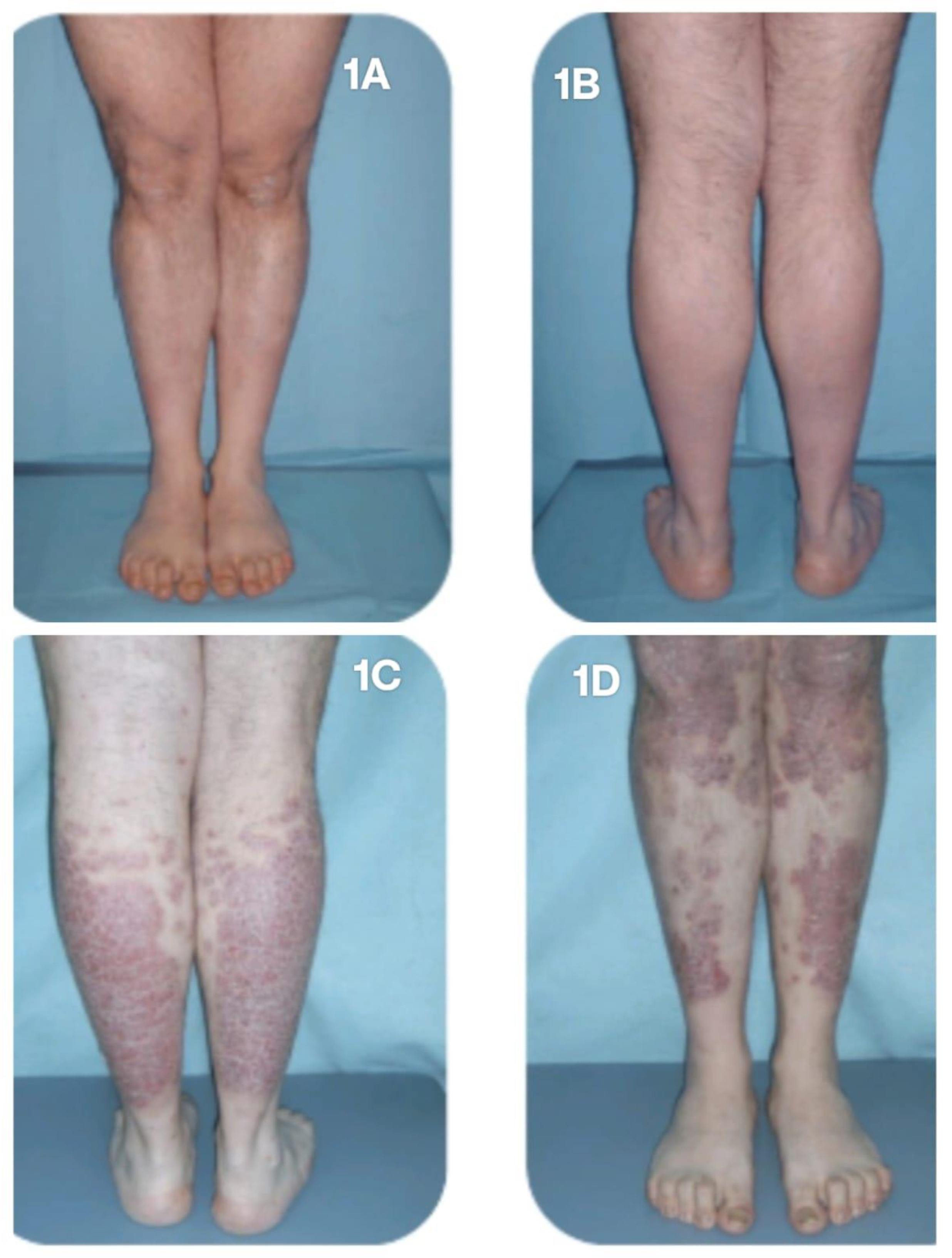

At Week 52, one patient achieved complete clinical remission of AA, while the other two improved to a mild stage of the condition, with a SALT score <20. The mSALT score was 8.75. Clinical improvement was also noted in cutaneous psoriasis, with a mPASI score of 0.5. None of the three patients reported joint pain. However, the fourth patient, affected by PsA, despite achieving complete clinical remission of AA (SALT 0 since Week 24), experienced significant worsening of joint disease, with a patient-reported pVAS score of 9, and a flare of the cutaneous manifestations, predominantly affecting the lower limbs, with a PASI score of 12 (

Figure 1A-D), and nail involvement. This patient subsequently discontinued baricitinib therapy and transitioned to alternative treatments.

4. Discussion

Together with previous studies about the constellation of autoimmune disorders, our case series presented the coexistence of psoriasis and AA in the same patient, suggesting shared pathogenetic mechanisms. Both AA and psoriasis are considered T-cell-mediated dermatoses. Among the various T-cell subsets associated with the diseases, T-helper (Th)1 and Th17 can be linked with AA and psoriasis [

14]. As demonstrated by Suarez Farinas et al., in comparative transcriptome analysis using lesional skins of patients with AA and psoriasis and non-lesional control skins, Th1/interferon-related makers were increased in both diseases [

15]. Moreover, IL-17, mainly produced by Th17, was reportedly involved in the pathogenesis of both psoriasis and AA [

16].

Furthermore, systemic treatments with tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitors, cyclosporine, phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor, and other biologics targeting IL-12/23 or IL-17 for psoriasis were also reported to be implicated in the development of AA [

6].

In the literature, there are case reports of patients with AA treated with JAKi approved for certain forms of arthritis. Todberg et al. described a complex case of a male patient affected by psoriasis, PsA, and AA, who achieved significant improvement in both rheumatological and dermatological conditions with tofacitinib [

17]. More recently, in 2023, Kolcz et al. reported a case involving a 14-year-old adolescent with atopic dermatitis and AU successfully treated with upadacitinib, a JAKi already approved for PsA treatment [

18]. In contrast, apart from a RCT investigating its use in juvenile idiopathic arthritis, there are no studies in the literature describing the application of baricitinib in other forms of arthritis [

19].

Baricitinib has been widely used in dermatology as a new molecular-targeted therapy. Increasing evidence suggests that baricitinib is effective against AD, AA, psoriasis, and vitiligo. Many inflammatory dermatoses are driven by inflammatory mediators that rely on JAK/STAT signals, and the use of JAK inhibitors has become a new strategy for the treatment of diseases for which conventional drugs have not been effective [

20]

Our experience has highlighted that baricitinib, the first JAKi approved for AA, is not indicated for psoriasis, but could represent a valid alternative therapeutic treatment in patients affected by both conditions. In our sample, 3 out of 5 patients had already undergone biological therapies with anti-TNF-alpha, anti-IL-17, and anti-IL-23, often discontinued despite good control over psoriasis due to the lack of efficacy, or even worsening, on AA. Our data not only suggest, in accordance with the literature, the efficacy of baricitinib on alopecia, but also a potential efficacy in controlling psoriatic pathology, with maintenance of joint stability and improvement of PASI. Only one patient experienced worsening of PsA following the switch from bDMARD (Ixekizumab) to Baricitinib, indicating the need to further investigate the efficacy of this drug on the joint component.

The main limitations of this study include the small sample size, which restricts the generalizability of our findings, and the absence of biologic-naïve PsA patients, limiting the assessment of baricitinib as a first-line treatment in this population. Additionally, all patients had already achieved adequate control of their psoriatic disease with prior therapies before transitioning to baricitinib, making it difficult to evaluate its efficacy on active, uncontrolled psoriasis. Moreover, no patients presented with particularly extensive cutaneous involvement, reducing the ability to assess the drug’s impact on severe plaque psoriasis.

5. Conclusions

Our experience, although limited to a small group of individuals, highlights the importance of treating multiple concomitant diseases with a single drug, to minimize the onset of side effects and increase the quality of life of affected patients. Larger, prospective studies including biologic-naïve patients and those with more extensive skin involvement are needed to better define the role of baricitinib in psoriasis and PsA management.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.D. and E.M..; data curation, Ga.Co., L.D., Gi.Ca. and A.R.; writing—original draft preparation, E.M. and L.D.; writing—review and editing, F.A., Gi.Ca., L.M.P. and A.R.; visualization, L.D., Gi.Ca., L.M.P. and A.R; supervision, E.C. and L.B.; project administration, L.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the consent of local ethical committee was not required in Italy for the real-life clinical study.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further enquiries can be directed in the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AA |

Alopecia Areata |

| AU |

Alopecia Universalis |

| JAKi |

Janus kinase inhibitors |

| PsA |

Psoriatic arthritis |

| STAT |

Signal transducer and activator of transcription |

| SALT |

Severity of Alopecia Tool |

| PASI |

Psoriasis Area Severity Index |

| pVAS |

Pain Visual Analogue Scale |

| DMARDs |

Disease-Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drugs |

References

- Rehan, S.T.; Khan, Z.; Mansoor, H.; Shuja, S.H.; Hasan, M.M. Two-way association between alopecia areata and sleep disorders: A systematic review of observational studies. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2022, 84, 104820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diluvio, L.; Matteini, E.; Lambiase, S.; Cioni, A.; Gaeta Shumak, R.; Dattola, A.; Bianchi, L.; Campione, E. Effect of baricitinib in patients with alopecia areata: Usefulness of trichoscopic evaluation. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2024, 38, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abedini, R.; Hallaji, Z.; Lajevardi, V.; Nasimi, M.; Karimi Khaledi, M.; Tohidinik, H.R. Quality of life in mild and severe alopecia areata patients. Int J Womens Dermatol 2017, 4, 91–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Global report on psoriasis; WHO: Geneva, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Belasco, J.; Wei, N. Psoriatic Arthritis: What is Happening at the Joint? Rheumatol Ther 2019, 6, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, J.M.; Yang, H.J.; Lee, W.J.; Won, C.H.; Lee, M.W.; Chang, S.E. Association between psoriasis and alopecia areata: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dermatol 2022, 49, 912–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anastasiou, C.; Goh, C.; Holland, V. Recovery of hair in the psoriatic plaques of a patient with coexistent alopecia universalis. Cutis 2017, 99, E9–E12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- King, B.; Ohyama, M.; Kwon, O.; et al. BRAVE-AA Investigators. Two Phase 3 Trials of Baricitinib for Alopecia Areata. N Engl J Med 2022, 18, 1687–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freitas, E.; Guttman-Yassky, E.; Torres, T. Baricitinib for the Treatment of Alopecia Areata. Drugs 2023, 83, 761–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Guo, L.; Wang, L.; Jiang, X. The efficacy and safety of tofacitinib, peficitinib, solcitinib, baricitinib, abrocitinib and deucravacitinib in plaque psoriasis - A network meta-analysis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2022, 36, 1937–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loo, W.J.; Turchin, I.; Prajapati, V.H.; Gooderham, M.J.; Grewal, P.; Hong, C.H.; Sauder, M.; Vender, R.B.; Maari, C.; Papp, K.A. Clinical Implications of Targeting the JAK-STAT Pathway in Psoriatic Disease: Emphasis on the TYK2 Pathway. J Cutan Med Surg 2023, 27 (Suppl 1), 3S–24S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Domizio, J.; Castagna, J.; Algros, M.P.; Prati, C.; Conrad, C.; Gilliet, M.; Wendling, D.; Aubin, F. Baricitinib-induced paradoxical psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020, 34, e391–e393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, B.A.; Senna, M.M.; Ohyama, M.; Tosti, A.; Sinclair, R.D.; Ball, S.; Ko, J.M.; Glashofer, M.; Pirmez, R.; Shapiro, J. Defining Severity in Alopecia Areata: Current Perspectives and a Multidimensional Framework. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2022, 12, 825–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bain, K.A.; Nichols, B.; Moffat, F.; Kerbiriou, C.; Ijaz, U.Z.; Gerasimidis, K.; McInnes, I.B.; Åstrand, A.; Holmes, S.; Milling, S.W.F. Stratification of alopecia areata reveals involvement of CD4 T cell populations and altered faecal microbiota. Clin Exp Immunol 2022, 210, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suárez-Fariñas, M.; Ungar, B.; Noda, S.; Shroff, A.; Mansouri, Y.; Fuentes-Duculan, J.; Czernik, A.; Zheng, X.; Estrada, Y.D.; Xu, H.; Peng, X.; Shemer, A.; Krueger, J.G.; Lebwohl, M.G.; Guttman-Yassky, E. Alopecia areata profiling shows TH1, TH2, and IL-23 cytokine activation without parallel TH17/TH22 skewing. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015, 136, 1277–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Li, S.; Ying, S.; Tang, S.; Ding, Y.; Li, Y.; Qiao, J.; Fang, H. The IL-23/IL-17 Pathway in Inflammatory Skin Diseases: From Bench to Bedside. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 594735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todberg, T.; Loft, N.D.; Zachariae, C. Improvement of Psoriasis, Psoriatic Arthritis, and Alopecia Universalis during Treatment with Tofacitinib: A Case Report. Case Rep Dermatol 2020, 12, 150–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kołcz, K.; Żychowska, M.; Sawińska, E.; Reich, A. Alopecia Universalis in an Adolescent Successfully Treated with Upadacitinib—A Case Report and Review of the Literature on the Use of JAK Inhibitors in Pediatric Alopecia Areata. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2023, 13, 843–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramanan, A.V.; Quartier, P.; Okamoto, N.; Foeldvari, I.; Spindler, A.; Fingerhutová, Š.; Antón, J.; Wang, Z.; Meszaros, G.; Araújo, J.; Liao, R.; Keller, S.; Brunner, H.I.; Ruperto, N.; JUVE-BASIS investigators; Paediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organisation. Baricitinib in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: An international, phase 3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, withdrawal, efficacy, and safety trial. Lancet 2023, 402, 555–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Qi, F.; Dong, J.; Tan, Y.; Gao, L.; Liu, F. Application of Baricitinib in Dermatology. J Inflamm Res 2022, 15, 1935–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).