Submitted:

06 June 2025

Posted:

12 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Study Selection

2.2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Data Synthesis

3.1.1. Barriers and Facilitators: Individual Level (Person with MCI / Dementia)

3.1.2. Barriers and Facilitators: Carer Level

3.1.3. Barriers and Facilitators: Deliverer Level

3.1.4. Barriers and Facilitators: Service Level

3.1.5. Barriers and Facilitators: Health System Level

3.1.6. Barriers and Facilitators: Societal System Level

3.2. Technology-Assisted Specific Findings

Barriers & Facilitators

4. Discussion

- -

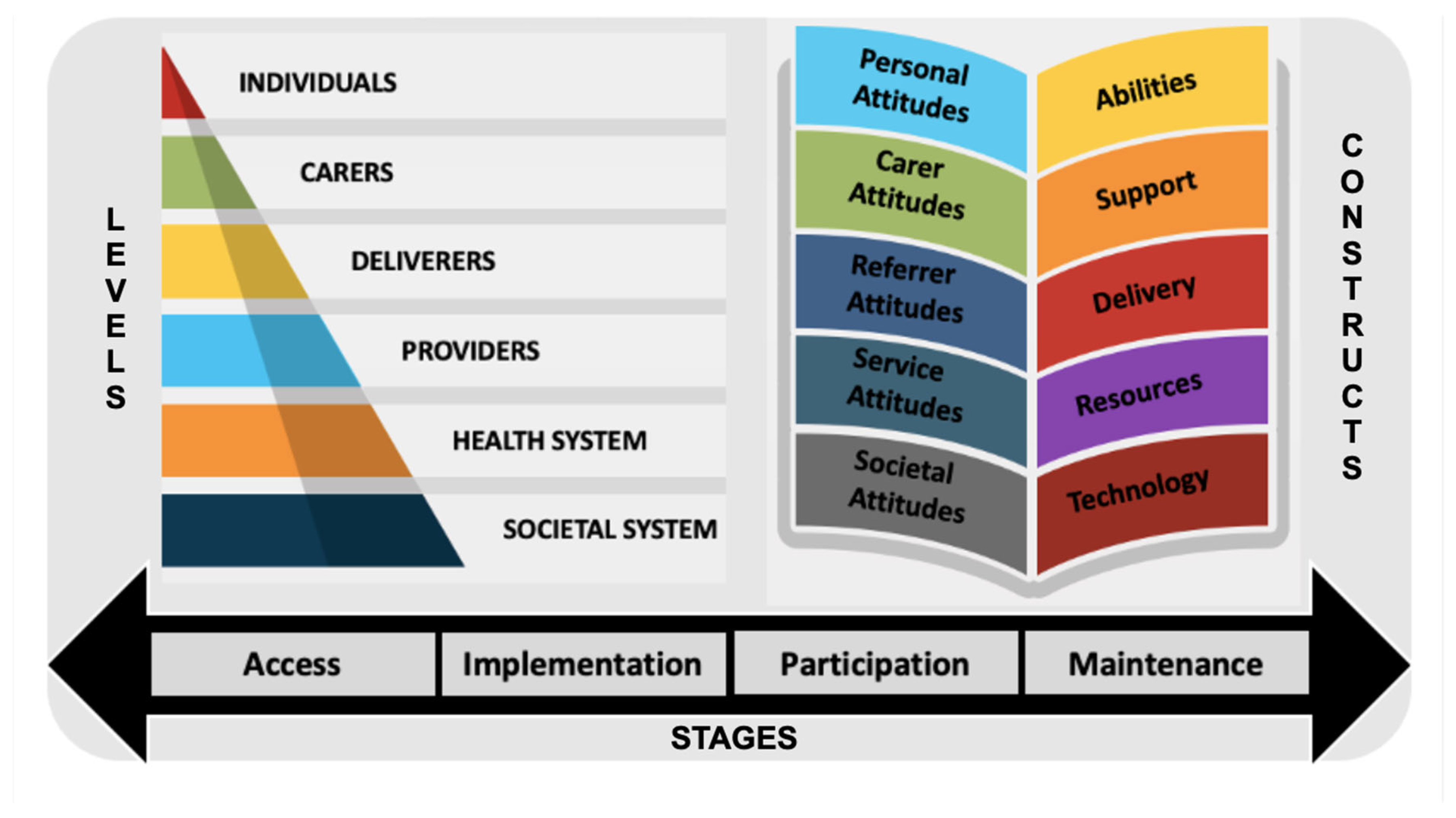

- For individuals, these factors could assist in choosing interventions appropriate to their personal attitudes, abilities, and resources.

- -

- For carers, these factors could assist in choosing interventions appropriate for the person they are assisting, as well as interventions that they themselves have the time, energy, and resources for.

- -

- For referrers and providers, these factors could guide the selection of client-appropriate interventions, increase awareness of skills and techniques required for effective delivery, and provide guidance on increasing client engagement.

- -

- For mental health services, these factors could be used when selecting interventions to procure and implement into different practices and settings, as well as provide guidance on the most effective training for staff for successful implementation and delivery.

- -

- For the designers and developers of interventions, these factors can be applied to tailor interventions to the needs of the target audience, in order to increase usability, uptake, user satisfaction, and increase intervention effectivity and engagement.

- -

- For researchers, these factors can be used to understand what might be important to measure, and to develop or include specific evaluation measures in future studies.

4.1. Access Stage

4.2. Implementation Stage

4.3. Participation Stage

4.4. Maintenance Stage

4.5. Technology Assisted Specific Trends

4.5.1. Accessibility

4.5.2. Connectivity

4.6. Limitations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Abbreviations

| Cognitive behavioural therapy | (CBT) |

| Modified CBT | (mCBT) |

| Mild cognitive impairment | (MCI) |

| Randomized controlled trials | (RCT) |

Appendices

Multimedia Appendices

References

- World Health Organisation. Dementia. Global action plan on the public health response to dementia 2017 – 2025. Updated 2023. Accessed June 2023. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia#:~:text=Key%20facts,nearly%2010%20million%20new%20cases.

- Hugo J, & Ganguli M. Dementia and cognitive impairment: epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Clinics in geriatric medicine, 2014, 30(3), 421–442. [CrossRef]

- Sousa S, Teixeira L, Paul C. Assessment of Major Neurocognitive Disorders in Primary Health Care: Predictors of Individual Risk Factors. Front. Psychol., Neuropsychology, 2020, 11(1). [CrossRef]

- UNC School of Medicine. Dementia: Identifying Mild, Moderate, and Severe. Depart of Neurology, UNC School Of Medicine. 2023. Accessed June 2023. https://www.med.unc.edu/neurology/divisions/memory-and-cognitive-disorders-1/family-concerns-1/normal-aging-mild-cognitive-impairment-and-dementia/.

- Alzheimer’s Society. The progression, signs and stages of dementia. Updated January 2024, Accessed June 2023. https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/about-dementia/symptoms-and-diagnosis/how-dementia-progresses/progression-stages-dementia.

- Kraus CA, Seignourel P, Balasubramanyam V, Snow AL, Wilson NL, Kunik ME, Schulz PE, & Stanley MA. Cognitive-behavioral treatment for anxiety in patients with dementia: two case studies. Journal of psychiatric practice, 2008, 14(3), 186–192. [CrossRef]

- Paukert AL, Kraus-Schuman C, Wilson N, Snow AL, Calleo J, Kunik ME, Stanley MA. The Peaceful Mind manual: a protocol for treating anxiety in persons with dementia. Behav Modif, 2013, 37(5), 631-664. [CrossRef]

- Tay KW, Subramaniam P, & Oei TP. Cognitive behavioural therapy can be effective in treating anxiety and depression in persons with dementia: a systematic review. Psychogeriatrics, 2019. 19(3), 264-275. [CrossRef]

- Tay KW, Subramaniam P, & Oei TP. Cognitive behavioural therapy can be effective in treating anxiety and depression in persons with dementia: a systematic review. Psychogeriatrics, 2019. 19(3), 264-275. [CrossRef]

- Stanley MA, Calleo J, Bush AL, Wilson N, Snow AL, Kraus-Schuman C, Paukert AL, Petersen NJ, Brenes GA, Schulz PE, Williams SP, Kunik ME. The peaceful mind program: a pilot test of a cognitive-behavioral therapy-based intervention for anxious patients with dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013. 21(7):696-708. [CrossRef]

- Ozen LJ, Dubois S, English MM, Gibbons C, Maxwell H, Lowey J, Sawula E, Bédard M. The efficacy of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy to improve depression symptoms and quality of life in individuals with memory difficulties and caregivers: A short report. Alzheimers Dement. 2022, 8(1):12252. [CrossRef]

- McClive-Reed KP, Gellis, ZD. Anxiety and related symptoms in older persons with dementia: directions for practice. J Gerontol Social Work, 2011, 54(1), 6-28. [CrossRef]

- Christie HL, Bartels SL, Boots LM, Tange HJ, Verhey FR, & de Vugt ME. A systematic review on the implementation of eHealth interventions for informal caregivers of people with dementia. Internet interventions, 2018, 13, 51-59.

- Wade VA, Karnon J, Elshaug AG, Hiller J. A systematic review of economic analyses of telehealth services using real time video communication. BMC Health Services. Research. 2010, 10(1). [CrossRef]

- Topo P. Technology Studies to Meet the Needs of People With Dementia and Their Caregivers A Literature Review. Helsinki Journal of Applied Gerontology, 2009, 28(1): 5-37. [CrossRef]

- Park MJ, Kim DJ, Lee U, Na EJ, Jeon HJ. A Literature Overview of Virtual Reality (VR) in Treatment of Psychiatric Disorders: Recent Advances and Limitations. Front Psychiatry, 2019, 10(505). [CrossRef]

- Braun A, Trivedi DP, Dickinson A, Hamilton L, Goodman C, Gage H, Manthorpe J. Managing behavioural and psychological symptoms in community dwelling older people with dementia: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Dementia. 2019, 18(7-8), 2950-2970. [CrossRef]

- Cowie J, Nicoll A, Dimova ED. The barriers and facilitators influencing the sustainability of hospital-based interventions: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res 2020, 588. [CrossRef]

- Glasgow RE, Lichtenstein E, Marcus AC. Why don't we see more translation of health promotion research to practice? Rethinking the efficacy-to-effectiveness transition. Am J Public Health. 2003, 93(8):1261-7. [CrossRef]

- Graham ID, Kothari A, McCutcheon C. (2018) Moving knowledge into action for more effective practice, programmes and policy: protocol for a research programme on integrated knowledge translation. Implementation Science. 13. [CrossRef]

- Titler MG. The Evidence for Evidence-Based Practice Implementation. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2008, Chapter 7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK2659/.

- Covidence. Covidence Systematic Review Management. Melbourne, VIC. 2023. Accessed June 2023. https://www.covidence.org/.

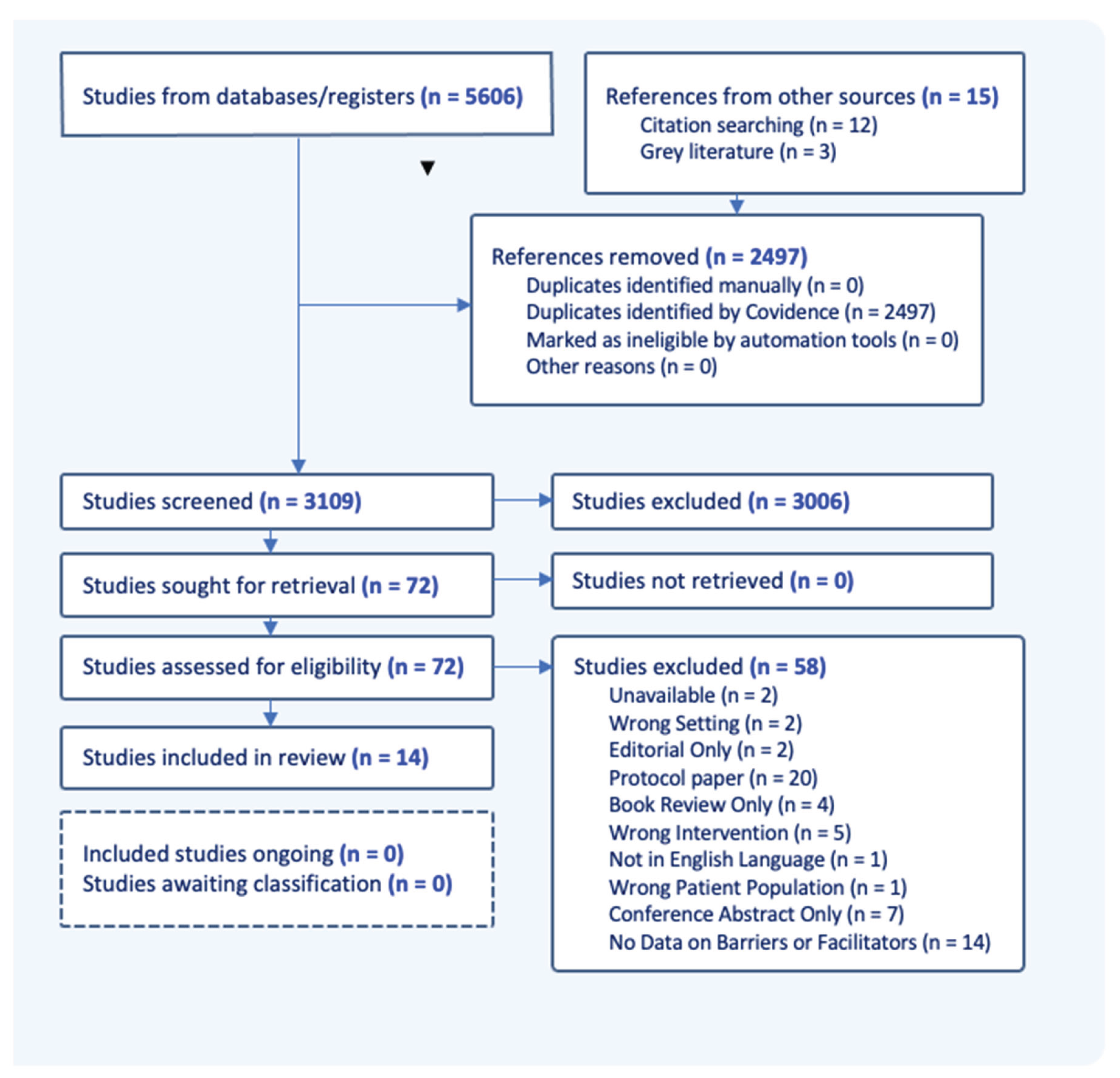

- PRISMA. (2023). Prisma Flow Diagram. Transparent Reporting of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. Accessed June 2023.

- Lienemann BA, Unger, JB, Cruz TB, Chu K. Methods for Coding Tobacco-Related Twitter Data: A Systematic Review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 2017, 19(3). [CrossRef]

- Carroll C, Booth A, Lloyd-Jones M. Should We Exclude Inadequately Reported Studies From Qualitative Systematic Reviews? An Evaluation of Sensitivity Analyses in Two Case Study Reviews. Qualitative Health Research Internet, 2012, 22(10), 1425-1434. [CrossRef]

- Luckman, S.(ed). Virginia Braun and Victoria Clarke, Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. Feminism & Psychology, 2016, 26(3), 387-391. [CrossRef]

- Delve HL, & Limpaecher A. How to Do Thematic Analysis. 2020. Essential Guide to Coding Qualitative Data. https://delvetool.com/blog/thematicanalysis.

- Gibbs GR. Coding part 2: Thematic coding. 2010. Accessed June 2023. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B_YXR9kp1_o.

- Guest G, MacQueen K, & Namey E. Applied Thematic Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.; 2011.

- Given L. The Sage Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods. 2008. Swinburne University, Charles Sturt University, Australia: SAGE Publications. Accessed June 2023. https://repository.bbg.ac.id/bitstream/515/1/The_Sage_Encyclopedia_of_Qualitative_Research_Methods.pdf.

- Manning J. In Vivo Coding. The International Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Dicle MF, & Dicle B. Content Analysis: Frequency Distribution of Words. The Stata Journal, 2018, 18(2), 379-386. [CrossRef]

- Saldana, J. (2009). The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications. Accessed in June 2023https://emotrab.ufba.br/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Saldana-2013-TheCodingManualforQualitativeResearchers.pdf.

- Baker S, Brede J, Cooper R, Charlesworth G, Stott J. Barriers and facilitators to providing CBT for people living with dementia: Perceptions of psychological therapists. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2022,29(3):950-961. [CrossRef]

- Berk L, Warmenhoven F, Stiekema APM, van Oorsouw K, van Os J, de Vugt M, van Boxtel M. Mindfulness-Based Intervention for People With Dementia and Their Partners: Results of a Mixed-Methods Study. Front Aging Neurosci. 2019, 11:92. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Douglas S, Stott J, Spector A, Brede J, Hanratty É, Charlesworth G, Noone D, Payne J, Patel M, Aguirre E. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression in people with dementia: A qualitative study on participant, carer and facilitator experiences. Dementia (London). 2022, 21(2):457-476. [CrossRef]

- Mattos MK, Manning CA, Quigg M, Davis EM, Barnes L, Sollinger A, Eckstein M, Ritterband LM. Feasibility and Preliminary Efficacy of an Internet-Delivered Intervention for Insomnia in Individuals with Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Alzheimers Dis. 2021;84(4):1539-1550. [CrossRef]

- McPhillips MV, Li J, Petrovsky DV, Brewster GS, Ward EJ 3rd, Hodgson N, Gooneratne NS. Assisted Relaxation Therapy for Insomnia in Older Adults With Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Pilot Study. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 2023, 97(1):65-80. [CrossRef]

- Robinson CM, Paukert A, Kraus-Schuman CA, Snow AL, Kunik ME, Wilson NL, Teri L, Stanley MA. The involvement of multiple caregivers in cognitive-behavior therapy for anxiety in persons with dementia. Aging & Mental Health, 2011 15:3, 291-298. [CrossRef]

- Staubo H, Misvaer N, Tonga JB, Kvigne K, Ulstein I. People with dementia may benefit from adapted cognitive behavioural therapy. Sykepleien Forskning 2017, 12(63874). [CrossRef]

- Tonga JB, Karlsoeen BB, Arnevik EA, Werheid K, Korsnes MS, Ulstein ID. Challenges With Manual-Based Multimodal Psychotherapy for People With Alzheimer's Disease: A Case Study. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2016 (4):311-7. [CrossRef]

- García-Alberca JM. Cognitive-behavioral treatment for depressed patients with Alzheimer’s disease. An open trial. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 2021, 71:1-8. [CrossRef]

- Kashimura M, Nomura T, Ishiwata A, Kitamura S, and Tateno A. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Improving Mood in an Older Adult with Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Case Report. J Nippon Med Sch, 2019,86(6). [CrossRef]

- Bauernschmidt D, Wittmann J, Hirt J, Meyer G, Bieber A. The Implementation Success of Technology-Based Counseling in Dementia Care: Scoping Review. JMIR Aging. 2024,7:515-44. [CrossRef]

- Borghouts J, Eikey E, Mark G, De Leon C, Schueller SM, Schneider M, Stadnick N, Zheng K, Mukamel D, Sorkin DH. Barriers to and Facilitators of User Engagement With Digital Mental Health Interventions: Systematic Review. J Med Internet Res. 2021, 23(3):24387. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fleming T, Bavin L, Lucassen M, Stasiak K, Hopkins S, & Merry S. Beyond the Trial: Systematic Review of Real-WorldUptake and Engagement With Digital Self-Help Interventions for Depression, Low Mood, or Anxiety. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 2018, 20(6), 199. [CrossRef]

- Groot Kormelinck CM, Janus SIM, Smalbrugge M, Gerritsen DL, Zuidema SU. Systematic review on barriers and facilitators of complex interventions for residents with dementia in long-term care. Int Psychogeriatr. 2021 Sep;33(9):873-889. [CrossRef]

- Marks E, Moghaddam N, De Boos D, Malins, S. A systematic review of the barriers and facilitators to adherence to mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for those with chronic conditions. British Journal of Health Psychology, 2022, 28(2):338-365. [CrossRef]

- Ng MM, Firth J, Minen, M., & Torous, J. (2019). User Engagement in Mental Health Apps: A Review of Measurement, Reporting, and Validity. Psychiatric Services, 70(7), 538-544. [CrossRef]

- Orgeta V, Qazi A, Spector A, Orrell M. Psychological treatments for depression and anxiety in dementia and mild cognitive impairment: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry, 2015 207(4), 293-298. [CrossRef]

- Ringle VA, Read KL, Edmunds JM, Brodman DM, Kendall PC, Barg F, Beidas RS. Barriers to and Facilitators in the Implementation of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Youth Anxiety in the Community. Psychiatr Serv. 2015, 66(9):938-45. [CrossRef]

- Faija CL, Connell J, Gellatly J, Rushton K, Lovell K, Brooks H, Armitage C, Bower P, & Bee P. Enhancing the quality of psychological interventions delivered by telephone in mental health services: increasing the likelihood of successful implementation using a theory of change. BMC Psychiatry, 2023, 23(1):405. [CrossRef]

- Gitlin LN. Introducing a new intervention: an overview of research phases and common challenges. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2013, 67(2):177-84. [CrossRef]

- Marchand E, Stice E, Rohde P, Becker CB. Moving from efficacy to effectiveness trials in prevention research. Behav Res Ther, 2011, 49(1):32-41. [CrossRef]

- XaCroix C. Security vs Access. Classroom, EdTech. Updated 2006. Accessed June 2023. https://edtechmagazine.com/k12/article/2006/10/security-vs-acces.

| Study Design | Values, n (%) | Tech Type | Values, n (%) | Participants | Values, n (%) |

| RCT* | 6 (42.8) | Non-Tech | 5 (35.7) | Dyad | 9 (64.3) |

| NR ExpTrial** | 2 (14.3) | Tech | 3 (28.6) | Individual | 4 (28.6) |

| Mixed Methods | 1 (7.1) | Both*** | 6 (35.7) | Therapists | 1 (7.1) |

| Case Report | 3 (21.4) | ||||

| Qual Research | 2 (14.3) |

| Focus | Values, n (%) | Method | Values, n (%) | Setting | Values, n (%) |

| Anxiety | 5 (35.7) | In Person Only | 5 (35.7) | At Home Only | 3 (21.4) |

| Depression | 3 (21.4) | IP and Phone | 6 (42.8) | Community | 9 (35.7) |

| Insomnia | 2 (14.3) | Internet-Based | 2 (14.3) | Hospital Clinic | 1 (7.1) |

| Increase in QoL | 3 (21.4) |

| Resources | Values, n (%) | Practice Supports | Values, n (%) | Technology Types | Values, n (%) |

| HW Tasks | 13 (100) | Reminder Cues | 6 (46.2) | Telephone | 5 (38.5) |

| Worksheets | 4 (30.8) | Reminder Calls | 5 (38.5) | Non-Wireless* | 3 (23.1) |

| Workbook | 2 (15.4) | Audio Recording | 4 (30.8) | WirelessInternet** | 3 (23.1) |

| Video Recording | 1 (7.7) | - Smart Devices | 1 (7.7) | ||

| - Web Portal | 1 (7.7) | ||||

| - Application | 1 (7.7) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).