Findings by Category (Interpretative Analysis)

“Strategies” was the most frequently mentioned category in both the testimonies and the coding process. Stakeholders from insurance companies and territorial entities described different actions and plans aimed at identifying and following up with individuals at high risk for cardiovascular disease. These included efforts in health education and information dissemination to encourage engagement with healthcare providers. Community-based initiatives were also highlighted as key tools for raising public awareness. Several participants shared successful experiences involving the implementation and monitoring of strategies in collaboration with national and international organizations, which contributed to capacity building and strengthened intersectoral coordination within the department.

“In previous years, information and education strategies have been developed so that people become involved with institutions. The department (government) generates some activities so that in X municipality they work with the community and that information reaches them.” Woman, 41 years old, territorial entities.

“There were community groups, they had educators or physical activity facilitators [...] So we started and worked on the experience at the departmental level, Santander en Movimiento worked for about four, six years… for more than 10 years we worked first on Carmen and then Santander en Movimiento.” Woman, 57 years old, territorial entities.

Stakeholders involved in population-level cardiovascular risk management recognized fragmentation across primary, secondary, and tertiary care levels. This fragmentation is characterized by difficulties in transferring information about high-risk populations, underscoring the need for improved coordination and more integrated approaches. The negative impact of these barriers is exacerbated not only by the lack of community-based interventions but also by the failure of existing efforts to align with the objectives of the Collective Intervention Plans (PIC) implemented in the territories. Participants emphasized the crucial role of community leaders in implementing effective health strategies. They underlined the importance of enhancing information flow between entities, particularly from healthcare insurers to health providers. This concern was reflected in the focus group discussions as follows:

“That is where the identification of the risk of these patients begins. The commitment was for 2023, when it was over, to be able to have and deliver this very important information that the insurers must consolidate or make a collective intervention plan that is effective for the population.” Woman, 39 years old, EAPB.

“The EPS door-to-door service seems very good to me, because they tell us how many there are or send them, and of course, we are percipient and we attend to them, it is difficult for us to go and get them, the most we can do is call, and many times it is lost, but the insurer's door-to-door service, I think is important, and it seems to me the most effective because people get motivated to bring the elderly, when they are visited, give them a piece of paper with the appointment, to guide them.” Woman, 50 years old, IPS.

“It would be necessary for community leaders to provide support through a loudspeaker, for the leader to make a loudspeaker in the health brigades.” Woman, 26 years old, IPS.

Health providers and territorial entities stakeholders referred to the importance of implementing more effective strategies to reduce cardiovascular risk, particularly in individuals who resume healthy lifestyles and habits, combined with community-based actions, as shown below:

“Above all, promoting healthy lifestyles, that is the most important thing, encouraging exercise, proper nutritional habits.” Woman, 36 years old, IPS.

“In this case, it would be necessary for community leaders to provide support through a public address system, for the leader to make public address systems in the health brigades.” Woman, 31 years old, IPS.

Within the “resources” category, stakeholders from insurance companies highlighted their responsibility for managing resources at the individual level, which poses barriers due to the need for effective optimization and allocation across diverse territories. In contrast, resources at the population level are managed by territorial entities. Territorial entities support health promotion activities, risk control, and demand generation. Persistent resource shortages constitute a major barrier to inter-institutional collaboration. This often results in misalignments, as some stakeholders focus on individualized care while others prioritize collective interventions—each shaped by the imperative to respond to population health needs.

“There is something super important that plays a role and is called the optimization of the UPC (Per Capitation Payment Unit – “Unidad de Pago por Capitación”) is how much the ministry gives me to be able to execute the risk of the entire population, so with that UPC, I must optimize it. It is not that it is worth more to me, I will do it for you, it is that there is no more money from the ministry and here we all must adapt to that resource that there is.” Woman, 39 years old, EAPB.

“… well, all the activities that are in the collective intervention plan have been developing and taking advantage of that, to do these complementarities in its municipalities that do not have sufficient resources, then let's say that it comes in there to attend and support this search, the early diagnosis of people with cardiovascular risk.” Woman, 41 years old, territorial entities.

“It is necessary to assign personnel to these activities, because we within the health personnel, have assigned some responsibilities, which demand time, and the responsibilities are very high for us to be taking charge of that.” Woman, 41 years old, Nurse, IPS.

“Articulation” was the third most frequently discussed category across the focus groups. Its importance was widely acknowledged; yet, participants also emphasized its fragility among territorial entities, healthcare insurers, and both public and private healthcare providers at primary and secondary levels. Weak articulation among stakeholders was identified as a central barrier affecting the delivery of comprehensive care within cardiovascular risk management programs:

“Yes, there must be comprehensiveness and there must be an articulation between providers. Who makes that articulation? The insurer through contracts, because we do not hire providers, we hire comprehensive routes. If then, within that exercise it is very complicated to work, join the public and private network… so, it is quite complicated to unite them” Woman, 39 years old, EAPB.

“It is necessary to synchronize with the EAPB, because the patient is recruited, but then they do not give the appointment, the patient gets tired, that internal medicine package is almost always lost, … it is necessary to manage with the EAPB, because the internists do not manage the health centers. We do the laboratories, we give them the medicines, but the specialists are not reached by the patient, they are lost.” Woman, 36 years old, Nurse, IPS.

Several successful experiences of coordination between territorial entities, healthcare insurers, and healthcare providers, as well as between insurers and providers, were described. These cases demonstrated the potential to facilitate interaction, dialogue, and feedback across primary and complementary care services through professionals or analysts specifically assigned to the program. The importance of information documented in clinical records was reaffirmed, particularly regarding indicators used to monitor risk management (precursor conditions) and program adherence. These data serve as valuable inputs for evidence-based decision-making, including the development of comprehensive care pathways and strategies to reduce service fragmentation.

“As far as the plan for collective interventions and the provision of services is concerned, let's say, several activities have been articulated with the municipal entity and with the providers in the territory, citing the insurers.” Woman, 41 years old, territorial entities.

“So, what is the advantage we have with this actor in our model? And it is that they permanently articulate with the primary provider and here within the EAPB there is a professional for these municipalities in charge of cardiovascular risk. So, let's say that it allows for this articulation between the three, between the three EAPB stakeholders, primary and complementary, then it allows this route to flow more. Yes, and the results, well, we are really seeing them. So, we provide training at the first level from that complementary component and this, I think, is one of the greatest, as well as successful experiences that we have currently regarding this cohort.” Woman, 39 years old, EAPB.

“Yes, there are the analysts, for example, who are with the IMAP (information system), so there is also a professional in charge there and there are the analysts, who are in charge of doing those follow-ups, whether they gave you the medicine or not, and they notify us of those developments and we, well, as we are the ones who ultimately hire the provider.” Woman, 36 years old, EAPB.

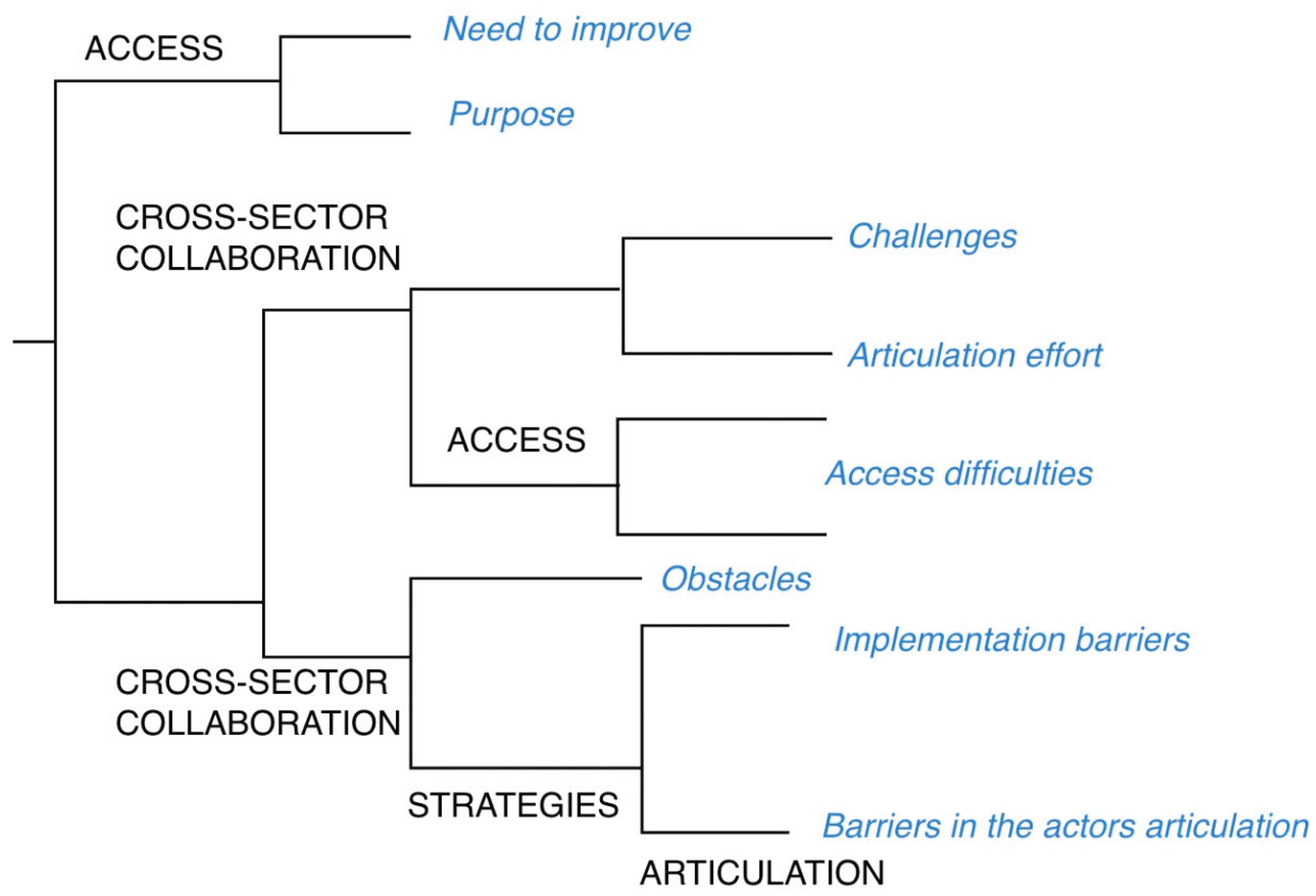

“Access” to services was conceptualized as the actual potential for entry into and utilization of essential healthcare services, based on insightful interpretations offered by institutional stakeholders. Overall, the narratives highlighted access barriers related to sociodemographic characteristics, limitations in social support networks, and logistical challenges faced by service providers, particularly in the distribution of medications for cardiovascular risk management.

“… those who come from rural areas or dispersed rural areas are even worse. The difficulties there are many and what would be needed because there are many… many adjustments, because even if the individual plan includes promotion and maintenance within the route, everything that has to be done for a person and the complementary interventions, it does fall short, the resources are few for the dispersion that exists here, it is complex” Woman, 41 years old, territorial entities.

“Age, the population is almost always or most commonly elderly, most people at risk (cardiovascular risk program) do not have a support network, and the level of education is very low, so they do not even know what they are taking, age is important, the support network, education, is what affects the most among other things.” Woman, 52 years old, Physician, IPS.

“When they go to the pharmacy, they ask for medicine and there is no medicine, so they have to go back to the doctor, and he changes the medicine, if there is, if not, they have to wait, so that he calls the EAPB pharmacy to deliver it, even the user gets lost because of this.” Woman, 26 years old, Nursing Assistant, IPS.

“Cross-sector collaboration” emerged as a critical category requiring coordinated efforts across the health system to effectively overcome key barriers and ensure the delivery of comprehensive care and services. Participants identified several challenges, including a lack of alignment among stakeholders, the absence of governance frameworks for resource management and allocation, and limited institutional capacity to coordinate and implement the diverse actions necessary to achieve integrated and effective care.

“There are challenges that involve these other areas, the challenge of articulation with other sectors such as infrastructure, sports, and education; In other words, if there is a big challenge, it is the issue of achieving articulation between all sectors to achieve a goal. Specifically, for example, the CERS (Healthy Cities, Environments and Ruralities – “Ciudades, Entornos y Ruralidades Saludables”) strategy that comes from the Ministry that includes infrastructure of sports sites that are not the responsibility of the Ministry of Health, which makes it more difficult to achieve this articulation” Woman, 57 years old, territorial entities.

“But we are falling short, there are things, because there are many actions from different fronts that must be worked on, from industry, from education, from everywhere.” Woman, 41 years old, territorial entities.

“We need to improve a lot to reduce these cardiovascular risks, but it does not only depend on us, but on other people and other circumstances, things outside of us, but there are many needs and things to improve.” Woman, 31 years old, Nurse, IPS.

In the “risk measurement” category, the role of data flow and information exchange among system stakeholders was highlighted as essential for planning both individual and population-level activities. Participants emphasized the importance of validating and enriching this information during the collection and analysis processes. Testimonies from representatives of territorial entities and healthcare insurers underscored the value placed on strengthening information systems to support continuous monitoring and evaluation of cardiovascular risk management at both individual and collective levels.

“Within the cardiovascular risk database, all the interventions that are established within the route are contemplated, such as taking laboratory tests in its control, according to the stratification that the user has, all the diagnostic aids and all the consultations, whether by general medicine, specialized medicine and paramedics, nutrition, psychology. So, this information is captured within the database, which also allows us to see how this evolution occurs.” Woman, 39 years old, EAPB.

“…the indicators: I think that the most successful thing that one can show are the indicators.” Woman, 39 years old, territorial entities.

In contrast, some successful experiences were highlighted, including previous projects conducted in Santander that enabled the evaluation, analysis, and validation of cardiovascular risk measurement among key population stakeholders. For territorial entities, resuming such initiatives was deemed pertinent and potentially feasible through joint efforts and sustained implementation. However, healthcare providers did not offer specific insights or narratives related to this category.

“The STEPWise 1 and 2 study, those studies were successful and if you notice, those studies are the result of all the work that was done over those years,… so it is a successful experience that Santander had, which has suddenly been abandoned a little, but I know that with collective interventions and giving it, let’s say, support to the dimension (dimension 2 of Public Health) it can be rescued again, that we do not need to suddenly invest so much, but rather help the municipality to organize what it has at home” Woman, 57 years old, territorial entities.

“Stewardship” was a category that emerged exclusively among stakeholders from territorial entities. Several barriers to effective state governance need to be addressed to foster collaboration and coordination in the implementation of public policies. While participants acknowledged the adequacy and clarity of existing legislation, regulations, and government strategies, they also emphasized a lack of personnel with the capacity to advocate for intersectoral agreements, monitor the organization of strategic plans, and manage cardiovascular risk and related interventions within the framework of the current Comprehensive Health Care Routes (RIAS).

“And the other thing is that there is also a barrier at the state level” Woman, 57 years old, territorial entities.

“People are needed, people with clear policies, there are many policies. There are many strategies, there are many, but get your teeth into it, sit down as a territorial entity and say let's work on this” Woman, 57 years old, territorial entities.

“This must be a government policy, so that it is not the same” Woman, 41 years old, territorial entities.