1. Introduction

Yellow fever is endemic to or has endemic zones in thirteen Latin American countries [

1] and thirty-four African countries as of 2023 [

2]. A safe and inexpensive vaccine can prevent yellow fever [

3]. The yellow fever vaccination requires only one shot to protect against the disease for the rest of one's life. In 2013, there were an estimated 84,000 to 170,000 severe cases of yellow fever and 29,000 to 60,000 fatalities [

4,

5].

Yellow fever's first appearance in the Americas is uncertain due to a lack of early medical records and difficulty in retrospective diagnosis in 1648 [

6]. In 2013, an estimated 130,000 cases of yellow fever were reported in Africa. Considering the current vaccine coverage rate, there will be (95%CI 51,000-380,000) instances of jaundice, bleeding, and fever, with 78,000 (95%CI 19,000-180,000) fatalities [

7]. The tropical regions of ten Latin American nations and thirty-one African nations are endemic to the flavivirus known as yellow fever (YF). In Africa, the disease is transmitted by the

Aedes africanus mosquito, while in South America, it is spread mainly by the

Haemagogus and

Sabethes species [

2]. The most common hosts for this parasite are monkeys [

8]. It is believed that yellow fever (YF) originated in Africa, but the first recorded case was in 1648 in Yucatán, Mexico. Major cities, such as Montevideo, Uruguay; Tocopilla, Chile; and Quebec, Canada, were severely affected by disease outbreaks resulting from international trade. At least 25 epidemics occurred in New York between 1668 and 1870, and other cities were also severely affected. In Europe, YFV was also a problem; in 1821, an epidemic occurred in Barcelona, and the first recorded case was in Cadiz, Spain. Outbreaks throughout history are broken down by year and geographic region [

9]. The YFV-urban transmission cycle was significantly influenced by the mosquito Aedes aegypti, which successfully expanded its geographic distribution due to its ability to breed in small water, produce desiccation-resistant eggs, and prefer human interaction [

10].

Yellow fever is a severe acute illness characterized by fever, nausea, vomiting, and hepatitis, with 20-60% of cases resulting in death [

11]. Africa has a lower-case fatality rate. Yellow fever in the Americas primarily involves a sylvatic cycle between non-human primates and forest-dwelling mosquitoes (e.g.,

Haemagogus spp.), with occasional spillover into urban settings where

Aedes aegypti enables human-to-human transmission, while in Africa, transmission occurs via a sylvatic cycle, an intermediate (savannah) cycle involving humans and mosquitoes at forest edges, and an entirely urban cycle, making African transmission dynamics more complex and facilitating more frequent outbreaks due to overlapping ecological and social factors [

11].

The 1930s development of live, attenuated YF vaccines and their widespread deployment in the 1940s contributed to the decline of the disease; however, periodic YF activity persists in endemic regions [

12]. The 17D strain, a safe and effective vaccination, was produced in 1936. YF vaccines are produced by inoculating viral seeds into chicken embryos and subsequently collecting the infected embryos according to the World Health Organization (WHO) regulations [

13]. Since 1970, vaccine coverage has improved, but gaps persist in areas with a high risk of yellow fever. An estimated 393-472.9 million people still need vaccination to reach WHO's 80% population coverage threshold, compared to 66%-76% in 1970 [

14]. Prizes in Physiology or Medicine were bestowed upon Theiler in 1950 for his work in advancing scientific understanding of yellow fever vaccine development.

Although vaccination is sometimes underutilized, its importance as a preventive measure is underscored by the collaboration between the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization and the World Health Organization's initiatives for laboratory detection and vaccine delivery. Contemporary vaccines are not infallible, although they effectively mitigate and prevent yellow fever epidemics [

15]. Between 2000 and 2006, the majority of side effects reported to VAERS were mild and resolved spontaneously. Common symptoms included fever, pain, itching, headaches, redness at the injection site, urticaria, and rashes. Like with other vaccines, more adverse events and local inflammatory events were recorded by women. The higher rate of reporting serious adverse events among men and older people makes biological sense [

16]. This review paper highlights the journey of the yellow fever Vaccine and explores its history, development, immunology, safety, and prospects, educating readers on its multifaceted aspects and potential advancements.

2. Milestones in Yellow Fever Vaccine Development

High viral loads, jaundice, hepatic apoptosis, kidney failure, heart damage, bleeding, and shock characterize the severe systemic sickness known as yellow fever. Over 400 million people have been vaccinated with a live, attenuated (17D) vaccine since its development in 1936. Vaccination rates in the United States are around 250,000 per year. Both live attenuated vaccines are currently in the second round of clinical trials. One is weakened experimentally through cell culture, while the other is engineered to produce antibodies specific to dengue through genetic modification. It will go into phase 3 studies after being licensed to Sanofi Pasteur [

17]. Developed in 1937, the 17D vaccine is a tiny icosahedral virus that has three structural proteins and seven non-structural proteins. More than 500 million people have taken it since its release. The process of making the vaccine using embryonated chicken eggs has remained unchanged since 1945. So far, the chemical basis of 17D attenuation remains unknown. One dosage contains between 104 and 106 pfu of virus, and six producers create 30-60 million doses annually. To keep one's immune system strong, the World Health Organization recommends booster shots every ten years [

18]. In the early 20th century, yellow fever spread worldwide, causing devastating epidemics in coastal ports of the United States. Mosquito larvae carried the virus, and 10% to 15% of patients died from symptoms like fever, jaundice, and hemorrhages. There was no cure or palliative treatment, and medical authorities quarantined affected individuals under a premonitory yellow flag.

The disease's devastating impact on the United States has left a lasting legacy [

19]. A study analyzed CD8+ T cells responding to live yellow fever virus and smallpox vaccines. Results showed a significant primary effector response, high specificity, and memory differentiation. Vaccines also generated virus-specific CD8+ T cells, which decreased by more than 90% and transformed into long-lasting memory cells [

20]. Live-attenuated viral vaccines, shown by the yellow fever virus strain 17D, are both safe and efficacious, yet possess intricate attenuation mechanisms. This work examines the 17D attenuation mechanism and determines its resistance to ribavirin, suggesting a minimal likelihood of reversion or mutation, hence preserving a stable genotype despite external influences [

21]. The genome of the ARILVAX live attenuated yellow fever (YF) 17D vaccine was analyzed using consensus sequencing, revealing 12 nucleotide heterogeneities. These differences suggest a heterogeneous population, with some individuals indicating the presence of quasispecies. Some nts differed from some strains but coincided with others, possibly due to the consensus sequencing approach. Most heterogeneities were silent, and other YF 17D vaccines need further examination using consensus sequencing [

22]. Although these vaccinations are effective against viral infections, the processes that cause the attenuation of live attenuated viruses are yet unknown. Understanding the molecular processes that cause attenuation is crucial for utilizing the 17D live attenuated vaccination strain to deliver heterologous antigens. Type II interferon safeguarded mice against mortality and restricted the virus to lymphoid organs by inhibiting 17D replication by 1-2 days post-infection in murine models.

In vitro, IFN-γ treatment inhibited 17D replication more effectively than WT YFV [

23]. The study utilizes a Q anion-exchange membrane to extract YF virus from Vero cell supernatant. Adsorption assays and chromatographic studies are used to determine the optimal pH and elution technique. The Q membrane adsorber effectively captures the YF virus on a broad scale, achieving a viral recovery rate of 93%, satisfactory DNA concentrations, and notable dynamic capacity for viral particles. HCP levels surpass allowable thresholds, but can be mitigated during the polishing stage [

24].

The BEVS production technology has reached a point of maturity in commercial manufacture, as evidenced by the approval of vaccines like CERVARIX. Insect cell-based products could be developed more quickly in the future as a result of this lessening of product development uncertainty. This technology's "plug and play" feature might make it sustainable in underdeveloped nations by allowing vaccines tailored to individual needs to be mass-produced [

25]. Vaccines have evolved due to factors like safety, tolerability, and potency. Improved vaccines have led to more demanding manufacturing processes, while older vaccines, such as influenza, are still produced using outdated technologies. Modern manufacturing processes are essential for producing vaccines that are equivalent to or superior to their predecessors, while new technologies may be necessary for the development of innovative vaccines. Despite these advancements, challenges persist, including the need to adapt manufacturing procedures, address regulatory issues, and manage rising costs [

26]. This study employs a regression model in conjunction with serological data from 11 countries to estimate the yellow fever burden across 34 African nations.

Vaccinations administered after 2005 have the potential to avert 3–6 million fatalities in the lifetimes of those who have received them. The sylvatic and urban transmission cycles are likely where immunization will have the most significant impact. By allocating 37.7 million doses annually for PMVCs from 2018 to 2026, we can reduce the risk of global transmission and prevent 9.89 million YF infections. While discussing the problem of YF transmission shifting from the sylvatic cycle to urban inter-human transmission, the study highlights the significance of different vaccination levels in preventing outbreaks [

27]. Over the past four decades, the world has made significant progress in vaccine use, mainly due to global political commitment, effective program management, and quality control. Despite challenges in low-income countries, vaccination services are reaching an unprecedented number of people, underscoring the need for additional resources to ensure future success [

28].

3. Yellow Fever Vaccine Immunology

Mosquitoes transmit the viral illness known as yellow fever, and one of the most effective ways to prevent its spread has been through vaccination. The 17D live-attenuated yellow fever vaccine is used to prevent the disease. The 17D vaccine, a safe and effective live virus vaccine, is derived from chick embryos inoculated with a seed virus. It forms the basis for the 17D-204 and 17DD lineages, with 99.9% sequence homology [

29]. Nucleotide sequence analysis is used to determine YFV diversity, and the rates of evolution are constant across regions. There can be as much as a sixteen percent disparity between genotypes from South America and Africa.[

30]. Results from the 36 trials demonstrate that the yellow fever vaccine is highly effective in inducing an immune response and providing lifelong protection against the virus with a single dose. The following groups are given extra care: those with HIV, very young children, pregnant women, and those with severe malnutrition; hence, a booster dosage is not necessary [

31]. A single vaccination strategy based on YF-specific CD8+ T-cells profiles and neutralizing antibodies is suggested in yellow fever vaccination guidelines. It is possible to achieve long-term immunity with a single vaccination if there is an adequate supply of neutralizing antibodies and a functionally competent pool of memory T-cells [

32].

The development of yellow fever vaccines using bioinformatics-predicted antigens represents a promising approach to enhance vaccine efficacy and safety. Through computational analyses, researchers can identify conserved, immunodominant epitopes within the yellow fever virus (YFV) genome, particularly targeting structural proteins such as the envelope (E) protein and non-structural proteins like NS1 [

33]. These

in silico methods enable the prediction of B-cell and T-cell epitopes with high immunogenic potential, reducing the reliance on traditional empirical approaches. Epitope-based vaccines can be designed to elicit targeted immune responses while minimizing adverse effects associated with live-attenuated vaccines, such as the 17D strain [

34]. This strategy holds significant promise for next-generation vaccines, especially in populations with contraindications to live vaccines and in preparing rapid responses to future outbreaks [

35,

36].

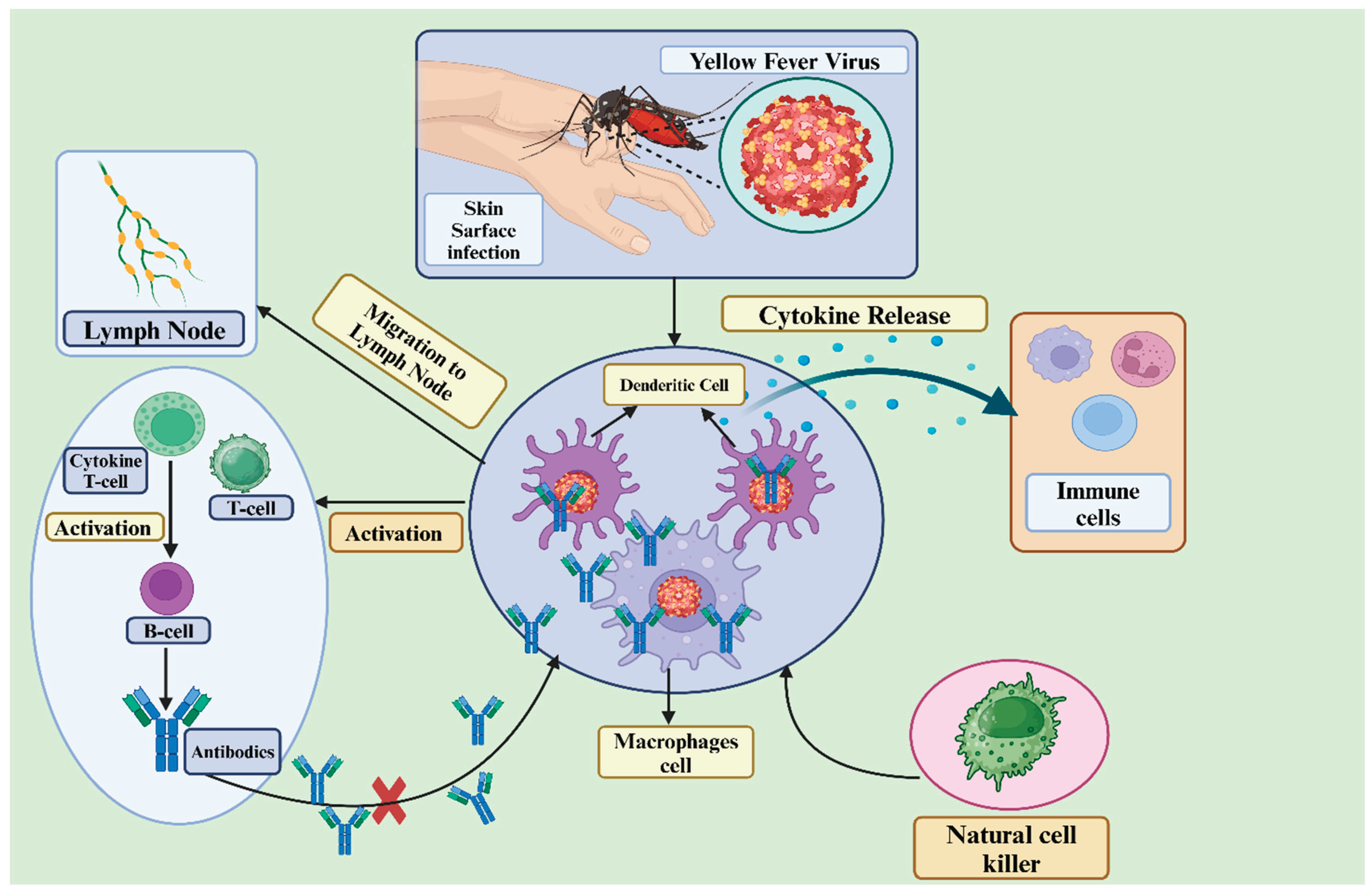

3.1. Mechanisms of Immune Response to Yellow Fever Virus

The immune response to the yellow fever virus involves the cooperation of both innate and adaptive immune systems to identify, combat, and eradicate the virus.

Figure 1 illustrates the immune response to the yellow fever virus as a coordinated defense mechanism that involves both innate and adaptive immunity. It begins with innate recognition, cytokine release, and the activation of natural killer cells, followed by a T-cell response and the production of neutralizing antibodies.

3.1.1. Innate Immune Responses to Vaccination with 17D:

The yellow fever vaccine provides 10 years of protection with a single injection. NK cell status after vaccination shows increased expression of TLR-3 and nine markers, suggesting NK cells play a role in protective memory [

32]. The study explores the immune response to yellow fever vaccination, revealing the significant role of innate immunity. It highlights increased TNF+ neutrophils, IFN+ NK cells, and IL-10+ monocytes, and identifies primary sources of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines that contribute to protective immunity [

37]. A 17-day yellow fever vaccine triggered an innate immune response in peripheral blood, as demonstrated by elevated monocytes, NK cell subpopulations, granulocyte activation status, Fc-R and IL-10-R expression, and the results of the study [

28]. Children vaccinated with either YF-17DD or YF-17D-231/77 yellow fever strain exhibited a well-regulated inflammatory and regulatory immune response, as indicated by the study's analysis of cytokine-mediated immune responses [

38]. Attenuated live yellow fever virus 17D primary immunization stimulates innate immunity, decreases peripheral blood T and B cells, and promotes robust adaptive immunity, according to the study [

39]. Live attenuated yellow fever vaccines are effective and safe worldwide. PRNT antibodies exhibit a harmonious innate and adaptive immune response, a proinflammatory and regulatory profile, and a polarized regulatory reaction, with PV-PRNTMEDIUM1 serving as the hallmark [

40].

3.1.2. Adaptive Immune Response

The adaptive immune response, including cellular and humoral immunity, becomes prominent within a few days after infection or vaccination.

(a). Humoral (antibody) response

In a trial conducted in locations without YFV circulation, 288 children and adults were studied to determine the effect of age and pre-existing flavivirus humoral immunity on vaccination immunity against 17DD-YF [

41]. A Swiss experiment evaluated the efficacy of the live-attenuated yellow fever vaccine YF-17D in both the first and subsequent doses. Because baseline neutralizing antibodies impacted both the immunological response and the multiplication of the vaccine virus, the booster dose reduced the immune response [

42]. A Special Immunizations Program study found that re-vaccination increases antibody levels in patients with low pre-vaccination serologies, and booster vaccination should be considered if persistently high[

43]. This study examines the effectiveness of the 17D live attenuated yellow fever vaccine in individuals with a compromised immune system. They found a memory-like phenotype that is linked to good expansion upon re-encounter with the antigen [

44]. The 17D vaccine induces early and viremia-dependent immune system involvement, particularly by CD8+ T cells, and efficient neutralizing antibody production. The study found a significant increase in CD8+ and CD4+ T cells, paralleling viremia, especially in the first-time vaccines [

45].

(b). Cellular response:

The cellular immune response involves T cells attacking infected cells directly to combat the yellow fever virus. A study on yellow fever vaccination responses identified 92 and 50 epitopes, with many causing strong immunodominant responses, providing broad coverage for academic, diagnostic, and therapeutic purposes [

46]. Serious consequences from the yellow fever virus (YFV) can be prevented with vaccination. The 17D YFV strain is an excellent resource for investigating human immunity due to its ability to provoke strong T cell responses and neutralizing antibodies.Researchers used HLA-DR tetramers to investigate how CD4 T cells from vaccinated individuals responded to YFV. According to the results, YFV-specific T cells remain in the body for up to two weeks following vaccination, with frequencies ranging from zero to one hundred cells per million [

47]. High-throughput single B-cell cloning is used in the study to track how people's B cells respond to the 17D vaccine for yellow fever. The study discovered that both conventional and switched immunoglobulin MBC groups were able to influence B cell reactivity. Affinity maturation persisted for 6-9 months after vaccination, suggesting that germinal center activity persisted. B-cell responses can be better understood with the help of the results [

48]. Two different antigen formulations based on non-viral DNA for attenuated yellow fever (YF) virus are presented in the study. The full-length envelope protein and the lysosomal-associated membrane protein signal, LAMP-1, were combined in the pL/YFE formulation so that it could elicit robust T-cell responses against nearly all of the epitopes produced by the YF 17DD vaccination. Overall, the pL/YFE formulation was more effective than the 17DD vaccine, as it produced higher titers of anti-YF neutralizing antibodies. Mice subjected to intracerebral inoculation with the YF virus exhibited total resistance following administration [

49]. Early gene signatures that predict immune responses in patients immunized with the yellow fever vaccine YF-17D were elucidated using a systems biology approach. Scientists were able to associate and anticipate YF-17D CD8+ T cell responses with 90% accuracy using a gene profile that included C1qB and TNFRS17 [

50]. The study analyzes CD8+ T cells responding to live yellow fever and smallpox vaccines. Results show a significant primary effector response, high specificity, and memory differentiation. The vaccines also produce virus-specific CD8+ T cells, which are functional and distinct from human CD8+ T cells specific for persistent viruses [

51].

3.2. Immune Memory and Duration of Protection

Memory B cells can provide more antibody-producing cells and maintain LLPC numbers. CD8 T lymphocytes eliminate cells that are contaminated. Scientists used effective live vaccinations to study the immunological responses of humans to viruses, specifically yellow fever and smallpox [

52]. The primary goal of studying human CD8+ T cells is to identify subsets and the mechanisms of differentiation, with a focus on chronic viral infections. We examine the various reactions, variability, and differences between antigen-experienced and naïve CD8+ T cells. The study found that, in addition to having broad specificity, it is large, polyfunctional, has a great proliferative capacity, and persists over time [

53]. Developing a live-attenuated vaccine, vYF, has demonstrated minimal safety issues and is well-tolerated. It promotes early innate immunity, YFV-specific antibodies, and effective resistance to virulent challenge. This vaccine is designed to address the global shortage of yellow fever vaccinations [

54]. The live attenuated virus vaccination provides lifelong protection against yellow fever by inducing a robust CD8+ T cell response. An analysis of 41 vaccinees revealed a decline in the frequency of naïve-like YF-specific CD8+ T cells over time. Almost all donors had these cells. In contrast to naïve cells from uninfected donors, these cells exhibited characteristics similar to those of the Tscm portion of stem cell-like memory. The findings indicate that YF vaccination serves as the optimal model for investigating memory CD8+ T cells with an extended half-life in humans [

55]. A meta-analysis of 36 studies from 20 countries found that seroprotection rates after a single yellow fever vaccine were near 100% by 3 months, remaining high in adults for 5-10 years [

56]. The study emphasizes the need for booster YFV doses to maintain protective antibody levels, particularly in areas with ongoing epidemics or epizootics, and prioritizes those who have not received vaccination [

57]. To establish vaccination requirements, the study examined the geometric mean titers and seropositivity rates of adults vaccinated at various intervals. The study recommended a booster dosage for prolonged protection in infants and toddlers and observed decreased immunogenicity under normal conditions [

58].

4. Vaccine Safety and Adverse Events

There is a small but real possibility of bad reactions and side effects from the yellow fever vaccination, while it is usually safe and relatively effective. Individuals with compromised immune systems may be more susceptible to side effects following a yellow fever vaccine than those with healthy immune systems. Replication of the attenuated vaccine strain poses a rare but real danger of severe illness or death [

59]. There have been safe and effective yellow fever (YF) vaccinations on the market since the 1930s. However, there are now more precautions and contraindications than ever before, due to the limited number of reports of major adverse events (SAEs). Nearly all (938 out of 1,938) recorded adverse events were safety-related (SAEs) between 2007 and 2013. Reporting rates increased with age, with anaphylaxis reporting highest in 18-year-olds. Continued education for physicians and travelers is crucial for older travelers [

60].

Table 1.

Yellow fever vaccine safety and adverse events.

Table 1.

Yellow fever vaccine safety and adverse events.

| # |

Category |

Description |

Frequency |

Management |

Reference |

| 1 |

Severe and rare adverse events, |

YEL-AVD or YEL AND |

Rare |

Inactivated YF 17D virus |

[61] |

| 2 |

Serious adverse events |

Hypersensitivity events, anaphylactic shock, Viscerotropic disease and neurologic syndrome |

25 in 35 people |

17D and 17DD yellow fever Vaccine |

[62] |

| 3 |

Allergic Reactions |

Anaphylactic reaction |

40 in 5,236,820 |

Yellow fever vaccine |

[63] |

| 4 |

Severe adverse reactions |

YEL-AVD, YEL-AEs and YEL-AND |

6 patients |

17D-derived yellow fever vaccine |

[64] |

| 5 |

adverse events |

Fever, myalgia, and headache |

43 in 68 Adult |

yellow fever live-attenuated vaccine |

[65] |

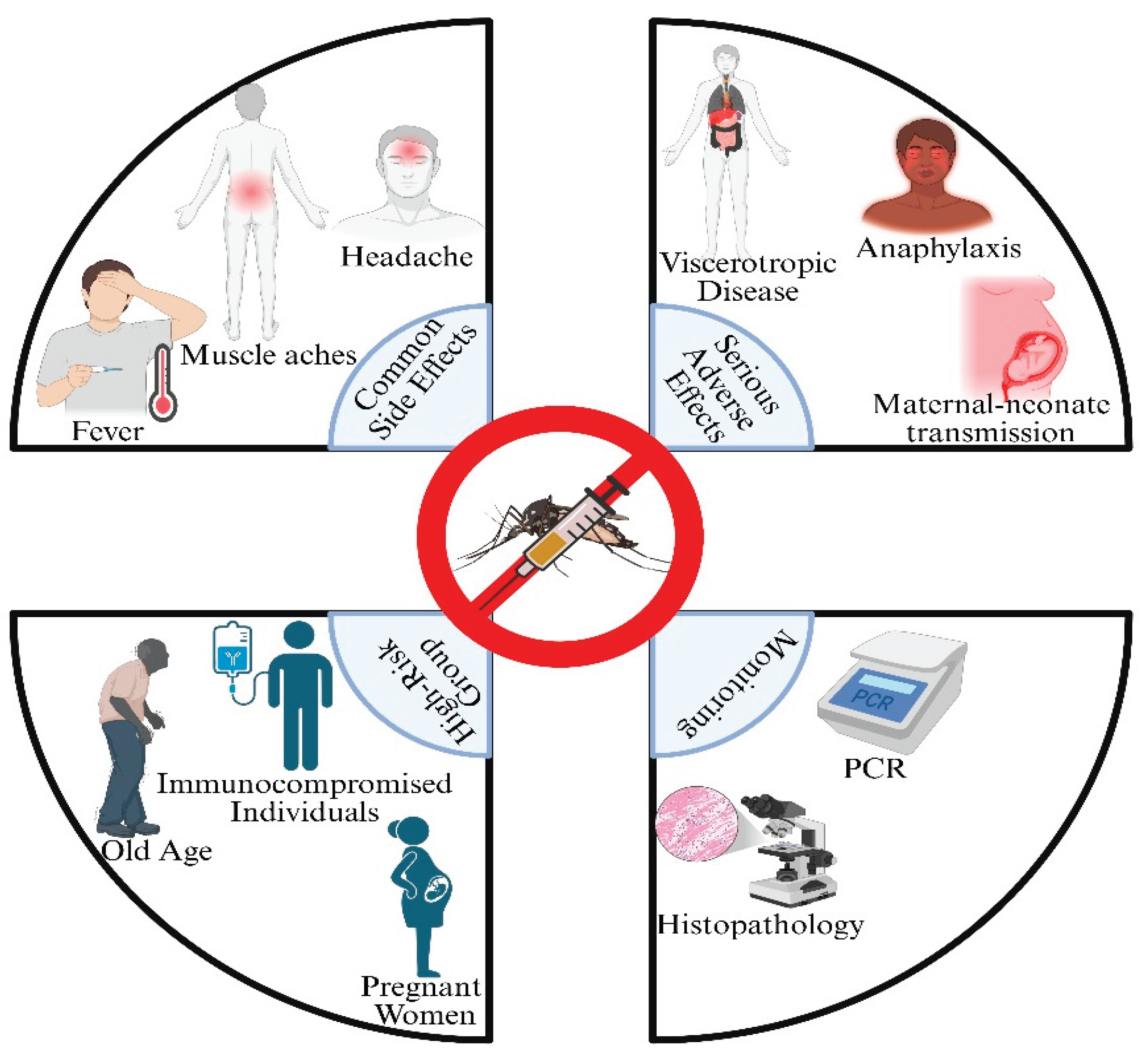

4.1. Common Adverse Events: Insights from Post-Marketing Surveillance

Minor adverse effects, including fever and upper respiratory symptoms, were observed in a systematic assessment of events related to yellow fever vaccination in at-risk populations. There were two examples of significant adverse outcomes resulting from maternal-neonate transfer, and older persons were detected in passive monitoring databases as having modest cases of viscerotropic disease, neurotropic disease, and allergy. The number of cases of serious side effects may be lower than the total number of people who got the vaccine [

66]. Two cases of hemorrhagic fever have been recorded in Brazil, both linked to the 17DD substrain of the yellow fever vaccine. A 22-year-old African American lady died six days after contracting jaundice, renal failure, and hemorrhagic diathesis; another case included a 5-year-old Caucasian girl who passed away after five days of illness. Both C6/36 cells and nursing mice tested positive for the yellow fever virus [

67].

The yellow fever vaccine is considered safe, according to a study that utilized data from the US Department of Defense and the Vaccine Safety Datalink; however, there have been reports of severe illness and death associated with its use. Subjects exposed to the YF vaccination or not were not shown to have significantly different rates of allergic, local, or moderate systemic responses [

68]. Viscerotropic disease, a high-mortality yellow fever vaccine-related disease, has been reported in 26 cases, potentially linked to autoimmune diseases. Bio-Manguinhos/Fiocruz is working on vaccine improvements [

69]. Researchers identified 66 studies that met these criteria; 25 of these studies employed passive monitoring methods, 24 used active surveillance methods, and 17 utilized a combination of the two. No cases of viscerotropic or neurotropic disease were observed in 2,660,929 patients in the general population who were actively monitored. With estimations for Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and Australia, a total of 107,621,154 patients' data were sourced from pharmacovigilance databases. Passive surveillance included 94,500,528 individuals, with no serious adverse events proven. When it came to clinical and laboratory follow-up, each country's database had its own distinct set of regulations, processes, and monitoring instruments.

Data from Brazil and Australia yield a lower estimate, data from the United States, obtained through VAERS, yield a medium estimate, and data from the United Kingdom and Switzerland yield a higher estimate, according to the pharmacovigilance databases. It is crucial to refine diagnostic techniques, such as PCR amplicon sequencing, pathology, and histology, to determine if the yellow fever vaccine causes serious adverse events [

70]. The ARILVAXTM vaccination achieved a greater percentage of seroconversion (94.9%) than YF-VAX (90.6%), according to a phase III randomised, double-masked study conducted in northern Peru. The majority of side effects were moderate and resolved on their own after receiving either vaccination, and both were highly immunogenic. Two YF vaccinations have never been compared in a pediatric population before in a randomized, double-masked study [

71] (

Figure 2)

.

4.2. Managing Vaccine-Associated Complications

High fever, hepatic dysfunction, renal failure, hypercoagulability, and platelet dysfunction are manifestations of yellow fever (YF), an exceedingly rare but serious adverse event (SAE) after vaccination. An infrequent adverse effect, termed YEL-AND, manifested after a YF vaccination. When 53 case reports were examined, 38 were found to have meningoencephalitis, 7 to have Guillain-Barré Syndrome, 6 to have Acute Disseminated Encephalomyelitis, and 5 to have myelitis. Patients diagnosed with YEL-AND who also had GBS, ADEM, or myelitis had a terrible prognosis [

72]. Five occurrences of encephalitis and one case of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis were identified as being caused by the attenuated vaccination (YEL), according to the study's examination of neurologic adverse effects following immunization. YEL rarely causes encephalitis post-vaccination, and recovery is common in healthy adults. The relationship between ADEM and GBS is uncertain. YEL is indicated for wild-type YFV exposure, low reporting rates, and no fatalities[

73]. In high-risk regions, the YF vaccine is recommended since its benefits outweigh its risks; it is also safe and effective. There have been reports of significant adverse effects, even though YFV infection is more fatal than SAEs. Early detection and management, communication of immunization benefits and hazards, and prevention of misinformation are all responsibilities of healthcare staff [

74].

4.3. Balancing Risk and Benefit: The Yellow Fever Vaccination Dilemma

The severity of the disease and the vaccine's effectiveness make it challenging to get the yellow fever vaccine, particularly for individuals who are more likely to experience adverse reactions. Until a safer vaccine is developed, doctors need to consider the pros and cons of YF 17D vaccinations for travelers. When formulating plans for endemic areas, policymakers should prioritize vaccination safety. Although the vaccine poses a lesser threat of death than infection with the wild-type virus, the common denominator among immunologically sensitive travelers remains uncertain. Most cases of yellow fever are in tropical America, where wild migrant workers carry the disease as they travel through the continent's forested interior and edges.

Between 1999 and 2009, Brazil reported 392 occurrences, with 90% of those infections occurring among unvaccinated individuals. The vaccine was not often administered in some areas of southern Brazil during an outbreak in 2008 and 2009 that caused substantial mortality in monkeys and humans. The study examined the hazards and benefits of the YF vaccine at this time [

75]. Brazil's endemic yellow fever (YF) vaccine, the 17DD, has been linked to four fatal adverse events, highlighting the need for adequate vaccine coverage and surveillance data. The study suggests cautious prevention, with a risk of 1 death per million doses [

76].

5. Yellow Fever Outbreaks and Control Measures

The mosquito-borne virus known as yellow fever can cause devastating epidemics in the tropical regions of South America and Africa. The fast spread of the YF virus through aircraft is a significant concern for public health, as mosquitoes mainly carry the infection. Climate, ecology, socioeconomic status, and politics are among the factors that influence the emergence of the virus. Through rapid reaction and urban development, the World Health Organization seeks to safeguard populations, stop the global spread of diseases, and limit epidemics [

77]. Yellow fever outbreaks threaten large populations in South America and Africa, affecting local mosquito populations, virus strain, and sociopolitical factors. The WHO EYE plan aims to control YF from 2017 to 2026, but limited vaccine supplies and increasing global travel pose risks. Resources, political will, and leadership are needed to control YF [

78].

5.1. Recent Yellow Fever Outbreaks: Lessons Learned and Challenges Faced

The yellow fever virus, which causes yellow fever, is a significant public health concern worldwide. In 2016, Brazil experienced a significant epidemic, causing widespread deaths in previously unaffected areas. The epidemic increased significantly from 2016 to 2019, causing economic burdens on health authorities and public health [

79]. Yellow fever epidemics have all had a severe impact on the healthcare system, people, and the economy. Eliminating worldwide outbreaks, particularly in African countries like Nigeria, requires the EYE strategy. Intermittent outbreaks occurred in Nigeria from 2017 to 2019, but better preparedness, faster responses, and more accurate reporting are required to reduce illness and death [

80]. In regions such as Africa and South America, where resources are scarce, diseases like yellow fever persist despite the availability of an effective vaccine. A pandemic in eastern Senegal was monitored by the Senegalese Ministry of Health, the WHO, the 4S network, and the Institut Pasteur de Dakar in 2020 and 2021 [

81]. Urban epidemics of yellow fever are expected to occur in South America, where the disease is currently spreading. Sylvatic cycles, vector control initiatives, immunization, monitoring, and case management have not been effective in preventing or controlling recent epidemics. Although urban

Aedes-human YF outbreaks are unlikely to occur, they nevertheless necessitate well-planned public health interventions [

82].

5.2. Role of Vaccination in Controlling Epidemics

Yellow fever vaccines control global epidemics by stimulating the immune system to recognize and combat pathogens, providing individual protection and contributing to herd immunity, thereby halting the transmission of the disease. In this study, controlling infection is crucial, as Angola is experiencing an emerging yellow fever outbreak, with cases reported in other African countries and China. A greater number of Chinese workers in Angola may not have had the opportunity to receive the yellow fever vaccine, which raises concerns about the potential spread of the disease in Asia. The area is likely to experience dengue fever outbreaks due to the large number of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, which are the primary carriers of the disease.

Table 2.

Main recent yellow fever epidemics.

Table 2.

Main recent yellow fever epidemics.

| # |

Outbreak and location |

Year |

Result |

Reference |

| 1. |

Angola and Brazil |

1970-2016 |

Yellow fever risk zones still have 393–472.9 million individuals who need to be vaccinated to fulfill the World Health Organization’s 80% coverage goal, despite substantial growth in vaccine coverage since 1970. |

[14] |

| 2. |

Angola and Brazil |

2015-2016 |

The 2016 YF outbreak in Luanda, Angola, was analysed using a vector-host epidemic model, revealing that timely vaccination and behavioural changes can reduce deaths and prevent future outbreaks. |

[83] |

| 3. |

Uganda (East Africa) |

2019-2022 |

The proposal suggests the establishment of a YF elimination task force to coordinate surveillance, vaccination campaigns, mosquito management strategies, and risk communication to reduce YF incidence and outbreaks. |

[84] |

| 4. |

Brazil |

2016-2017 |

Due to the presence of animal reservoirs, human susceptibility, and the presence of vectors, unvaccinated travelers in the affected states of Brazil are at risk of contracting the virus. A potential pandemic could be triggered by ecological conditions and enzootics, potentially leading to spillover. |

[85] |

| 5. |

Brazil |

2017–2018 |

In 2016, Brazil experienced the largest yellow fever outbreak in the Americas, primarily in densely populated areas like São Paulo, originating from three South American genotype variants. |

[86] |

| 6. |

West African and South American |

2001-2003 |

Yellow fever, a tropical ailment responsible for 200,000 cases and 30,000 fatalities each year, is spread by humans, mosquitoes, and monkeys, with the possibility of preventative and chimeric vaccines. |

[87] |

| 7. |

Brazil |

2016-2017 |

The YFV outbreak in Brazil necessitates prompt discovery and control via epidemiological and genetic surveillance, accompanied by a global plan aimed at eradicating epidemics by 2026. |

[88] |

| 8 |

Brazil |

2016-2018 |

UYF prevention relies on insect control measures, resistance to insecticides, behavioral measures, and health surveillance; however, recent outbreaks in Brazil have shown the ineffectiveness of these measures. |

[89] |

| 9. |

Angola |

2015-2016 |

Despite multiple vaccination campaigns, the Angola YFV outbreak reached its peak in February 2016, with 4,347 suspected cases and 377 deaths, leading to an emergency campaign in August 2016. |

[90] |

| 10. |

Angola |

2015 |

Yellow fever rapidly spreads from Luanda, Angola, with 49 districts reporting cases within three months. Prioritizing vaccination is recommended; however, constraints such as vaccine supply and delivery logistics must also be considered. |

[91] |

| 11. |

Brazil and Venezuela |

1990 to 2022 |

Nine patients with YF-compatible symptoms in French Guiana, Venezuela, Suriname, and Brazil died within 8 days, requiring stronger vaccination coverage due to the likely persisting sylvatic cycle. |

[92] |

| 12 |

South American countries |

2024-2025 |

Current epidemics with more than 200 cases and more than 100 deaths are associated with a lack of vaccinations in certain age groups in Colombia and Brazil, which have concentrated most of the cases. |

https://shiny.paho-phe.org/yellowfever/ |

Our emergency supply of vaccines is dwindling, and our monitoring systems are still relatively new. This is a significant threat to global health [

93]. Researchers developed a spatiotemporal model of yellow fever to predict the likelihood of outbreaks worldwide and the number of vaccinations required to eradicate them. The study indicated that the risk is very variable, with the Equatorial region of Latin America and West Africa being the primary regions with high-risk transmission. The study found that to eradicate YF outbreaks worldwide, a higher degree of population immunity is needed than what the WHO recommends (80%), and that each endemic country should have its vaccination plan based on its risk profile [

94]. Based on the provided data, two types of ecological niche models were created to assess the severity of yellow fever in sub-Saharan Africa. These models were used to predict future mass vaccination programs for health reasons, the demand for vaccines, and the rates of illness and death in different areas. In light of this data, international efforts to combat the rising threat of yellow fever can be better planned [

95]. The study reveals a decrease in yellow fever vaccine doses in Brazil before and during the pandemic, with stationary behavior in five regions, but an increasing trend in Alagoas State and Roraima State [

96].

The use of fractionated doses of yellow fever vaccine has emerged as a critical strategy to address vaccine shortages during epidemics. Administering one-fifth of the standard dose intramuscularly has demonstrated sufficient immunogenicity to confer short-term protection, as evidenced during the 2016 Angola outbreak and later campaigns in Brazil and the Democratic Republic of the Congo [

97,

98,

99,

100]. The WHO currently supports this approach for emergency use, especially when full-dose supplies are constrained. However, challenges remain: the duration of protection from fractionated doses is not fully established, especially in children and immunocompromised populations [

97,

98,

99,

100]. Additionally, this approach is not yet licensed for routine immunization or travel-related prophylaxis. Despite these limitations, fractionated dosing remains a valuable tool for rapid mass immunization, reducing transmission during urban outbreaks and enhancing preparedness for outbreaks. Its continued assessment and potential formal integration into immunization strategies require further clinical studies and regulatory consensus [

97,

98,

99,

100,

101].

5.3. Integrating Vaccination Strategies with Vector Control

A comprehensive approach that combines vaccination and vector control measures is essential for controlling vector-borne diseases, such as yellow fever, dengue, malaria, and Zika, targeting both human and environmental factors [

102]. YFV is transmitted through three cycles: sylvatic, intermediate, and urban, with the sylvatic cycle occurring between rainforest primates, the intermediate cycle in isolated rural communities, and the urban cycle facilitated by invasive, domesticated mosquitoes [

103]. After a time of low vaccination coverage, the vector-borne disease known as yellow fever has made a comeback in tropical Africa and South America. To curb future epidemics, recent mass vaccination initiatives have achieved a 27% decrease in both cases and deaths.[

104]. A deterministic model for vector-borne diseases with vaccines identifies mosquito fertility reduction as the most effective measure, with the highest vaccination rate resulting in the least mortality [

105].

6. Future Directions in Yellow Fever Vaccination

Yellow fever vaccination strategies must evolve to address global health changes, focusing on improving efficacy, expanding access, and integrating innovative technologies for stronger disease control. The need for new YF vaccine candidates is increasing due to limited seed lot systems, limited manufacturing capabilities, climate change, and the rapid spread of epidemics. Current YF vaccine candidates include inactivated, recombinant, plasmid-vectored, virus-like particle, mRNA, and plant-produced subunit vaccines, utilizing the 17D genetic backbone [

106].

6.1. Advancements in Vaccine Technology: Novel Approaches and Platforms

Advancements in vaccine technology have significantly improved safety, efficacy, speed, and adaptability, paving the way for addressing future global health challenges, such as pandemics and infectious diseases that lack effective vaccines. Researchers in the UK discovered that mRNA vaccine candidates protected mice and rhesus macaques from the deadly YF virus by inducing protective immune responses. Based on these results, these mRNA vaccines may be a suitable option for the permitted YF vaccine supply, which could aid in future epidemic prevention efforts by reducing vaccine shortages [

107]. The V3SWG, which stands for the Brighton Collaboration Viral Vector vaccines Safety Working Group, conducts risk assessments of live, recombinant viral vaccines that contain heterologous viral genes. An authorized vaccine against Japanese encephalitis was one of several that used genes from dengue and West Nile viruses [

108]. Engineered nanoparticles show potential as vaccine delivery platforms, enhancing mucosal and systemic immunity. However, clinical translation and the development of broad-spectrum vaccines are crucial due to cost and antigenic drift [

109].

6.2. Targeting Vulnerable Populations: Vaccination Equity and Accessibility

To control diseases like yellow fever, it is essential to have equitable vaccination coverage. However, there are hurdles to vaccine access for vulnerable people; thus, a holistic approach is needed. The research uses environmental factors to assess the susceptibility of Brazilian communities to a heavy YF load. Mild, low, and high levels of vulnerability were used for classification. Using a cumulative logit model, the North and Central-West regions were identified as the most vulnerable. Prioritizing YF surveillance and prevention is made easier by the results [

110]. The EYE strategy targets 40 high-risk countries to increase yellow fever vaccine coverage. However, coverage rates vary widely, with significant differences in America and Africa. This may be due to different target populations and vaccine availability[

111]. The WHO is employing dose-sparing strategies for its immunization initiative in Kinshasa, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, in response to the yellow fever epidemic in Angola. The 5-fold fractional-dose vaccination, evaluated for efficacy but not yet tested, can diminish infectious attack rates if efficacy surpasses 20% [

112].

6.3. Strengthening Surveillance and Monitoring for Vaccine-Preventable Diseases

Surveillance systems are crucial for preventing, controlling, and eradicating vaccine-preventable diseases, particularly in a globalized world where outbreaks can spread rapidly and quickly. Between 1999 and 2001, 67 confirmed cases and 42% of vaccinations occurred in Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, primarily due to the use of the yellow fever vaccine in monkey surveillance. The distribution of vaccines and the prevention of YF in susceptible human populations are both greatly assisted by epizootic surveillance [

113]. Brazil experienced a 33.6% yellow fever case fatality rate, primarily in southern states with low vaccination coverage, highlighting the need for the World Health Organisation's "Global Strategy to Eliminate Epidemic" [

114]. A surveillance network in Minas Gerais, Brazil, confirmed the first YFV case in non-human primates in 2021, highlighting the need for coordinated surveillance and contingency measures to prevent YFV spillover to humans[

115]. The objective of the 2007 GFIMS was to consolidate surveillance systems to enhance national monitoring of vaccine-preventable illnesses (VPDs). Conversely, the establishment of integrated VPD monitoring has proven to be a formidable undertaking [

116].

7. Yellow Fever in the Context of Emerging Infectious Diseases

Yellow fever, a mosquito-borne disease, poses a significant public health concern due to its sporadic outbreaks and rapid spread, particularly in urban areas. Despite the effectiveness of vaccines, it highlights the risks of emerging infectious diseases. Yellow fever, a feared infectious disease, is re-emerging due to increased human migration and low vaccination rates, necessitating stricter regulation, border checks, alternative vaccine research, and global efforts [

117].

7.1. Yellow Fever as a Model for Preparedness and Response

Yellow fever offers valuable lessons for public health systems in disease surveillance, vaccination strategies, and global collaboration, thereby enhancing response capabilities and preventing large-scale outbreaks, making it a critical model for addressing future public health threats. Brazil's YFV surveillance relies heavily on entomovirological monitoring, which facilitates the connection between human and non-human primate transmission. Finding unique or prospective vectors can shed light on their function in the propagation and maintenance of sylvatic YFV. Because of this, vector control, vaccination rates, and monitoring all need to be stepped up [

118]. Yellow fever, a mosquito-transmitted disease, is spreading in previously unaffected areas due to enzootic cycles in the Amazon basin of South America and Brazil, as well as its westward spread in Africa [

119]. A multidisciplinary study conducted in Colombia examined the transmission of arboviruses and found that both

Aedes aegypti mosquitoes in cities and sylvatic mosquitoes near cities had significant infection rates. The study found that early risk factors for transmission in rural areas include climate, socioeconomic status, and human activities [

120].

7.2. Potential Cross-Protection with Other Flaviviruses

Flaviviruses are a group of viruses that include yellow fever, dengue, Japanese encephalitis, West Nile, Murray Valley encephalitis, Saint Louis encephalitis, and Zika. They belong to the Flavivirus family and are classified into three categories: tick-borne, mosquito-borne, and those with no known vectors. JEV is the most critical flavivirus pathogen in swine, while WNV and MVEV infect pigs [

121]. Early research on cellular immunity to dengue virus (DENV) showed easily detectable T cell responses and serotype cross-reactivity in both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Serotype cross-reactivity is influenced by targeting immunodominant responses, with the most cross-reactive responses being directed against tetravalent DENV vaccines, including NS proteins [

122]. It is common for travelers, particularly those taking VFRs, to contract typhoid and paratyphoid fever, which are worldwide health concerns. A greater emphasis on preventative actions, including immunizations, is warranted in light of the increasing prevalence of antimicrobial resistance [

123]. A study highlights the need to assess the protective scope of live attenuated viruses (LAVs) against African swine fever (ASF), as their effectiveness is limited due to the diverse ASF isolates [

124].

7.3. One Health Approach: Integrating Animal and Human Health

The interconnectedness of human, animal, and environmental health is highlighted by the yellow fever case study, which exemplifies the One Health principle. The sylvatic transmission cycle of yellow fever involves a variety of insects, non-human primates, and mosquitoes, particularly those belonging to the genera Haemagogus and Sabethes. When infected mosquitoes bite people in or near forests, the disease can spread to humans. Monitoring monkey fatalities, or epizootics, can help predict when a human pandemic may occur. One country that has effectively utilized monkey population monitoring to prevent and respond to yellow fever epidemics is Brazil [

125]. Deforestation, urban expansion, and climate change further complicate control efforts by altering vector habitats and increasing human exposure to sylvatic transmission cycles [

126]. A coordinated One Health strategy involves integrating wildlife surveillance, vector control, environmental management, and human vaccination efforts to prevent and control yellow fever outbreaks effectively. This holistic model is essential not only for yellow fever but also for addressing other emerging zoonotic threats.

8. Limitations

This review has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, while we aimed to provide a comprehensive and up-to-date synthesis of the literature on yellow fever vaccination, the rapidly evolving nature of the field means that newly emerging data may not be included. Second, the review primarily draws from published literature in English, Portuguese, and Spanish, which may exclude relevant studies in other languages, especially those from endemic regions. Third, data on certain aspects—such as the long-term immunogenicity of fractionated doses and vaccine efficacy in immunocompromised populations—remain limited or inconclusive, which impacts the depth of analysis in these areas. Additionally, although this review encompasses both historical and recent findings, it does not conduct a formal systematic review or meta-analysis, which limits its ability to assess outcomes quantitatively. These limitations underscore the need for continued research and more robust, multicentric clinical studies to inform vaccination policies and outbreak preparedness strategies.

9. Conclusions

Yellow fever vaccine development has made significant progress, but challenges remain in comprehensive disease control. Addressing gaps in vaccination coverage, managing urban outbreaks, and balancing vaccine availability during emergencies requires novel vaccine technologies, integrated strategies, and strengthened surveillance efforts. The YF-17D live-attenuated vaccine, developed in 1937, revolutionized yellow fever control by offering adequate protection with a single dose. Vaccination drives in South America and Africa have significantly reduced the number of yellow fever cases worldwide. Global initiatives, such as the World Health Organization's stockpiles, have enhanced preparedness for outbreaks. Challenges for global yellow fever control include ensuring adequate vaccine supply, improving distribution networks, and addressing logistical challenges in urban areas. Novel vaccine platforms, including DNA, mRNA, and vector-based vaccines, offer opportunities to enhance efficacy and accessibility. The roadmap for a yellow fever-free future involves integrating vector control and vaccination strategies, strengthening global surveillance systems, and achieving universal vaccination coverage. This includes preventing mosquito breeding, using insecticides, and expanding laboratory networks to enhance disease control. Vaccination equity must also be prioritized, ensuring vulnerable populations receive protection through routine immunization and emergency campaigns. Yellow fever control is progressing, but challenges such as vaccine availability, urban outbreaks, and vector control persist. New vaccine technologies, global surveillance, and sustained commitment from governments, public health agencies, and international organizations are crucial for eradicating the disease.

Funding

The authors received no specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors for the development of this article. This research was developed thanks to the support of Universidad Internacional SEK del Ecuador and Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador. We are especially grateful to the research department at UISEK for covering the APC, which ensures the open access of this manuscript.

Declaration of Competing Interest

AJRM has served as a speaker and consultant for the following industries involved in dengue and arbovirus vaccines over the last decade: Sanofi Pasteur, Takeda, Abbott, MSD, Moderna, and Valneva. The remaining authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

This article has been registered in the Research Proposal Registration of the Coordination of Scientific Integrity and Surveillance of Universidad Cientifica del Sur, Lima, Peru.

References

- Angerami RN, Socorro Souza Chaves TD, Rodríguez-Morales AJ. Yellow fever outbreaks in South America: Current epidemiology, legacies of the recent past and perspectives for the near future. New Microbes New Infect 2025;65:101580. [CrossRef]

- Srivastava S, Dhoundiyal S, Kumar S, Kaur A, Khatib MN, Gaidhane S, et al. Yellow Fever: Global Impact, Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, and Integrated Prevention Approaches. Infez Med 2024;32:434-50.

- Reno E, Quan NG, Franco-Paredes C, Chastain DB, Chauhan L, Rodriguez-Morales AJ, et al. Prevention of yellow fever in travellers: an update. Lancet Infect Dis 2020;20:e129-e37. [CrossRef]

- Bassey BE, Braka F, Onyibe R, Kolude OO, Oluwadare M, Oluwabukola A, et al. Changing epidemiology of yellow fever virus in Oyo State, Nigeria. BMC Public Health 2022;22:467. [CrossRef]

- Kallas EG, D'Elia Zanella L, Moreira CHV, Buccheri R, Diniz GBF, Castiñeiras ACP, et al. Predictors of mortality in patients with yellow fever: an observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2019;19:750-8.

- Blake JB. Yellow fever in eighteenth century America. Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine 1968;44:673.

- Garske T, Van Kerkhove MD, Yactayo S, Ronveaux O, Lewis RF, Staples JE, et al. Yellow fever in Africa: estimating the burden of disease and impact of mass vaccination from outbreak and serological data. PLoS medicine 2014;11:e1001638. [CrossRef]

- Thomas RE. Yellow fever vaccine-associated viscerotropic disease: current perspectives. Drug design, development and therapy 2016;3345-53. [CrossRef]

- Barrett AD, Higgs S. Yellow fever: a disease that has yet to be conquered. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2007;52:209-29. [CrossRef]

- PETERSEN JL. BEHAVIORAL DIFFERENCES IN TWO SUBSPECIES OF AEDES AEGYPTI (L.)(DIPTERA: CULICIDAE) IN EAST AFRICA. University of Notre Dame, 1977.

- Sanchez-Rojas IC, Solarte-Jimenez CL, Chamorro-Velazco EC, Diaz-Llerena GE, Arevalo CD, Cuasquer-Posos OL, et al. Yellow fever in Putumayo, Colombia, 2024. New Microbes New Infect 2025;64:101572.

- Tuboi SH, Costa ZGA, da Costa Vasconcelos PF, Hatch D. Clinical and epidemiological characteristics of yellow fever in Brazil: analysis of reported cases 1998–2002. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 2007;101:169-75. [CrossRef]

- Monath TP, Nichols R, Archambault WT, Moore L, Marchesani R, Tian J, et al. Comparative safety and immunogenicity of two yellow fever 17D vaccines (ARILVAX and YF-VAX) in a phase III multicenter, double-blind clinical trial. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene 2002;66:533-41. [CrossRef]

- Shearer FM, Moyes CL, Pigott DM, Brady OJ, Marinho F, Deshpande A, et al. Global yellow fever vaccination coverage from 1970 to 2016: an adjusted retrospective analysis. The Lancet infectious diseases 2017;17:1209-17. [CrossRef]

- Frierson JG. The yellow fever vaccine: a history. The Yale journal of biology and medicine 2010;83:77.

- Lindsey NP, Schroeder BA, Miller ER, Braun MM, Hinckley AF, Marano N, et al. Adverse event reports following yellow fever vaccination. Vaccine 2008;26:6077-82. [CrossRef]

- Monath TP. Dengue and yellow fever—challenges for the development and use of vaccines. New England Journal of Medicine 2007;357:2222-5. [CrossRef]

- Barrett AD, Teuwen DE. Yellow fever vaccine—how does it work and why do rare cases of serious adverse events take place? Current opinion in immunology 2009;21:308-13.

- Bendiner E. Max Theiler: Yellow jack and the jackpot. Hospital Practice 1988;23:211-44. [CrossRef]

- Miller JD, van der Most RG, Akondy RS, Glidewell JT, Albott S, Masopust D, et al. Human effector and memory CD8+ T cell responses to smallpox and yellow fever vaccines. Immunity 2008;28:710-22. [CrossRef]

- Davis EH, Beck AS, Strother AE, Thompson JK, Widen SG, Higgs S, et al. Attenuation of live-attenuated yellow fever 17D vaccine virus is localized to a high-fidelity replication complex. Mbio 2019;10:10.1128/mbio. 02294-19. [CrossRef]

- Pugachev KV, Ocran SW, Guirakhoo F, Furby D, Monath TP. Heterogeneous nature of the genome of the ARILVAX yellow fever 17D vaccine revealed by consensus sequencing. Vaccine 2002;20:996-9. [CrossRef]

- Lam LM, Watson AM, Ryman KD, Klimstra WB. Gamma-interferon exerts a critical early restriction on replication and dissemination of yellow fever virus vaccine strain 17D-204. Npj Vaccines 2018;3:5. [CrossRef]

- Pato TP, Souza MCO, Silva AN, Pereira RC, Silva MV, Caride E, et al. Development of a membrane adsorber based capture step for the purification of yellow fever virus. Vaccine 2014;32:2789-93. [CrossRef]

- Cox MM. Recombinant protein vaccines produced in insect cells. Vaccine 2012;30:1759-66. [CrossRef]

- Ulmer JB, Valley U, Rappuoli R. Vaccine manufacturing: challenges and solutions. Nature biotechnology 2006;24:1377-83. [CrossRef]

- Jean K, Hamlet A, Benzler J, Cibrelus L, Gaythorpe KA, Sall A, et al. Eliminating yellow fever epidemics in Africa: vaccine demand forecast and impact modelling. PLoS neglected tropical diseases 2020;14:e0008304. [CrossRef]

- Okwo-Bele J-M, Cherian T. The expanded programme on immunization: a lasting legacy of smallpox eradication. Vaccine 2011;29:D74-D9. [CrossRef]

- Cetron MS, Marfin AA, Julian KG, Gubler DJ, Sharp DJ, Barwick RS, et al. Yellow fever vaccine recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2002. MORBIDITY AND MORTALITY WEEKLY REPORT RECOMMENDATIONS AND REPORTS RR 2002;51.

- Mokaya J, Kimathi D, Lambe T, Warimwe GM. What Constitutes Protective Immunity Following Yellow Fever Vaccination? Vaccines (Basel) 2021;9.

- Gotuzzo E, Yactayo S, Cordova E. Efficacy and duration of immunity after yellow fever vaccination: systematic review on the need for a booster every 10 years. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2013;89:434-44. [CrossRef]

- Wieten RW, Jonker EF, van Leeuwen EM, Remmerswaal EB, Ten Berge IJ, de Visser AW, et al. A Single 17D Yellow Fever Vaccination Provides Lifelong Immunity; Characterization of Yellow-Fever-Specific Neutralizing Antibody and T-Cell Responses after Vaccination. PLoS One 2016;11:e0149871. [CrossRef]

- Mishra N, Boudewijns R, Schmid MA, Marques RE, Sharma S, Neyts J, et al. A Chimeric Japanese Encephalitis Vaccine Protects against Lethal Yellow Fever Virus Infection without Inducing Neutralizing Antibodies. mBio 2020;11. [CrossRef]

- Mateus J, Grifoni A, Voic H, Angelo MA, Phillips E, Mallal S, et al. Identification of Novel Yellow Fever Class II Epitopes in YF-17D Vaccinees. Viruses 2020;12. [CrossRef]

- Lim HX, Lim J, Poh CL. Identification and selection of immunodominant B and T cell epitopes for dengue multi-epitope-based vaccine. Med Microbiol Immunol 2021;210:1-11. [CrossRef]

- da Silva OLT, da Silva MK, Rodrigues-Neto JF, Santos Lima JPM, Manzoni V, Akash S, et al. Advancing molecular modeling and reverse vaccinology in broad-spectrum yellow fever virus vaccine development. Sci Rep 2024;14:10842. [CrossRef]

- Silva ML, Martins MA, Espírito-Santo LR, Campi-Azevedo AC, Silveira-Lemos D, Ribeiro JGL, et al. Characterization of main cytokine sources from the innate and adaptive immune responses following primary 17DD yellow fever vaccination in adults. Vaccine 2011;29:583-92. [CrossRef]

- Campi-Azevedo AC, de Araujo-Porto LP, Luiza-Silva M, Batista MA, Martins MA, Sathler-Avelar R, et al. 17DD and 17D-213/77 yellow fever substrains trigger a balanced cytokine profile in primary vaccinated children. PLoS One 2012;7:e49828.

- Kohler S, Bethke N, Böthe M, Sommerick S, Frentsch M, Romagnani C, et al. The early cellular signatures of protective immunity induced by live viral vaccination. European journal of immunology 2012;42:2363-73. [CrossRef]

- Luiza-Silva M, Campi-Azevedo AC, Batista MA, Martins MA, Avelar RS, da Silveira Lemos D, et al. Cytokine signatures of innate and adaptive immunity in 17DD yellow fever vaccinated children and its association with the level of neutralizing antibody. Journal of Infectious Diseases 2011;204:873-83. [CrossRef]

- Reis LR, da Costa-Rocha IA, Campi-Azevedo AC, Peruhype-Magalhães V, Coelho-dos-Reis JG, Costa-Pereira C, et al. Exploratory study of humoral and cellular immunity to 17DD yellow fever vaccination in children and adults residents of areas without circulation of yellow fever virus. Vaccine 2022;40:798-810. [CrossRef]

- Bovay A, Nassiri S, Maby-El Hajjami H, Marcos Mondejar P, Akondy RS, Ahmed R, et al. Minimal immune response to booster vaccination against Yellow Fever associated with pre-existing antibodies. Vaccine 2020;38:2172-82. [CrossRef]

- Hepburn MJ, Kortepeter MG, Pittman PR, Boudreau EF, Mangiafico JA, Buck PA, et al. Neutralizing antibody response to booster vaccination with the 17d yellow fever vaccine. Vaccine 2006;24:2843-9. [CrossRef]

- Wieten RW, Goorhuis A, Jonker EFF, de Bree GJ, de Visser AW, van Genderen PJJ, et al. 17D yellow fever vaccine elicits comparable long-term immune responses in healthy individuals and immune-compromised patients. J Infect 2016;72:713-22. [CrossRef]

- Reinhardt B, Jaspert R, Niedrig M, Kostner C, L'age-Stehr J. Development of viremia and humoral and cellular parameters of immune activation after vaccination with yellow fever virus strain 17D: a model of human flavivirus infection. Journal of medical virology 1998;56:159-67.

- Stryhn A, Kongsgaard M, Rasmussen M, Harndahl MN, Osterbye T, Bassi MR, et al. A Systematic, Unbiased Mapping of CD8(+) and CD4(+) T Cell Epitopes in Yellow Fever Vaccinees. Front Immunol 2020;11:1836.

- James EA, LaFond RE, Gates TJ, Mai DT, Malhotra U, Kwok WW. Yellow fever vaccination elicits broad functional CD4+ T cell responses that recognize structural and nonstructural proteins. J Virol 2013;87:12794-804. [CrossRef]

- Wec AZ, Haslwanter D, Abdiche YN, Shehata L, Pedreno-Lopez N, Moyer CL, et al. Longitudinal dynamics of the human B cell response to the yellow fever 17D vaccine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020;117:6675-85. [CrossRef]

- Maciel Jr M, Cruz FdSP, Cordeiro MT, da Motta MA, Cassemiro KMSdM, Maia RdCC, et al. A DNA vaccine against yellow fever virus: development and evaluation. PLoS neglected tropical diseases 2015;9:e0003693.

- Querec TD, Akondy RS, Lee EK, Cao W, Nakaya HI, Teuwen D, et al. Systems biology approach predicts immunogenicity of the yellow fever vaccine in humans. Nat Immunol 2009;10:116-25. [CrossRef]

- Miller JD, van der Most RG, Akondy RS, Glidewell JT, Albott S, Masopust D, et al. Human effector and memory CD8+ T cell responses to smallpox and yellow fever vaccines. Immunity 2008;28:710-22. [CrossRef]

- Wrammert J, Miller J, Akondy R, Ahmed R. Human immune memory to yellow fever and smallpox vaccination. J Clin Immunol 2009;29:151-7. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed R, Akondy RS. Insights into human CD8(+) T-cell memory using the yellow fever and smallpox vaccines. Immunol Cell Biol 2011;89:340-5.

- Piras-Douce F, Broudic K, Chautard E, Raynal F, Courtois V, Gautheron S, et al. Evaluation of safety and immuno-efficacy of a next generation live-attenuated yellow fever vaccine in cynomolgus macaques. Vaccine 2023;41:1457-70. [CrossRef]

- Fuertes Marraco SA, Soneson C, Cagnon L, Gannon PO, Allard M, Maillard SA, et al. Long-lasting stem cell–like memory CD8+ T cells with a naïve-like profile upon yellow fever vaccination. Science translational medicine 2015;7:282ra48-ra48.

- Kling K, Domingo C, Bogdan C, Duffy S, Harder T, Howick J, et al. Duration of Protection After Vaccination Against Yellow Fever: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2022;75:2266-74. [CrossRef]

- Vaccines CGfSoYF. Duration of immunity in recipients of two doses of 17DD yellow fever vaccine. Vaccine 2019;37:5129-35.

- Collaborative group for studies on yellow fever v. Duration of post-vaccination immunity against yellow fever in adults. Vaccine 2014;32:4977-84.

- Wigg de Araujo Lagos L, de Jesus Lopes de Abreu A, Caetano R, Braga JU. Yellow fever vaccine safety in immunocompromised individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Travel Med 2023;30. [CrossRef]

- Lindsey NP, Rabe IB, Miller ER, Fischer M, Staples JE. Adverse event reports following yellow fever vaccination, 2007-13. J Travel Med 2016;23. [CrossRef]

- de Menezes Martins R, da Luz Fernandes Leal M, Homma A. Serious adverse events associated with yellow fever vaccine. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics 2015;11:2183-7. [CrossRef]

- E. Thomas R, L. Lorenzetti D, Spragins W, Jackson D, Williamson T. Reporting rates of yellow fever vaccine 17D or 17DD-associated serious adverse events in pharmacovigilance data bases: systematic review. Current Drug Safety 2011;6:145-54. [CrossRef]

- Kelso JM, Mootrey GT, Tsai TF. Anaphylaxis from yellow fever vaccine. Journal of allergy and clinical immunology 1999;103:698-701.

- Bae H-G, Domingo C, Tenorio A, de Ory F, Muñoz J, Weber P, et al. Immune response during adverse events after 17D-derived yellow fever vaccination in Europe. The Journal of infectious diseases 2008;197:1577-84. [CrossRef]

- Chan CY, Chan KR, Chua CJ, Nur Hazirah S, Ghosh S, Ooi EE, et al. Early molecular correlates of adverse events following yellow fever vaccination. JCI Insight 2017;2. [CrossRef]

- Thomas RE, Lorenzetti DL, Spragins W, Jackson D, Williamson T. The safety of yellow fever vaccine 17D or 17DD in children, pregnant women, HIV+ individuals, and older persons: systematic review. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2012;86:359-72. [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos PFC, Luna EJ, Galler R, Silva LJ, Coimbra TL, Barros VLRS, et al. Serious adverse events associated with yellow fever 17DD vaccine in Brazil: a report of two cases. The Lancet 2001;358:91-7. [CrossRef]

- Nordin JD, Parker ED, Vazquez-Benitez G, Kharbanda EO, Naleway A, Marcy SM, et al. Safety of the yellow fever vaccine: a retrospective study. Journal Of Travel Medicine 2013;20:368-73. [CrossRef]

- Martins RdM, Maia MdLdS, Santos EMd, Cruz RLdS, dos Santos PRG, Carvalho SMD, et al. Yellow Fever Vaccine Post-marketing Surveillance in Brazil. Procedia in Vaccinology 2010;2:178-83.

- Thomas RE, Lorenzetti DL, Spragins W, Jackson D, Williamson T. Active and passive surveillance of yellow fever vaccine 17D or 17DD-associated serious adverse events: systematic review. Vaccine 2011;29:4544-55. [CrossRef]

- Belmusto-Worn VE, Sanchez JL, McCARTHY K, Nichols R, Bautista CT, Magill AJ, et al. Randomized, double-blind, phase III, pivotal field trial of the comparative immunogenicity, safety, and tolerability of two yellow fever 17D vaccines (ARILVAXTM and YF-VAX (R)) in healthy infants and. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 2005;72:189-97.

- Lecomte E, Laureys G, Verbeke F, Domingo Carrasco C, Van Esbroeck M, Huits R. A clinician’s perspective on yellow fever vaccine-associated neurotropic disease. Journal of Travel Medicine 2020;27. [CrossRef]

- McMahon AW, Eidex RB, Marfin AA, Russell M, Sejvar JJ, Markoff L, et al. Neurologic disease associated with 17D-204 yellow fever vaccination: a report of 15 cases. Vaccine 2007;25:1727-34. [CrossRef]

- de Andrade Gandolfi F, Estofolete CF, Wakai MC, Negri AF, Barcelos MD, Vasilakis N, et al. Yellow Fever Vaccine-Related Neurotropic Disease in Brazil Following Immunization with 17DD. Vaccines (Basel) 2023;11. [CrossRef]

- Monath TP. Review of the risks and benefits of yellow fever vaccination including some new analyses. Expert review of vaccines 2012;11:427-48. [CrossRef]

- Struchiner CJ, Luz PM, Dourado I, Sato HK, Aguiar SG, Ribeiro JG, et al. Risk of fatal adverse events associated with 17DD yellow fever vaccine. Epidemiol Infect 2004;132:939-46. [CrossRef]

- Chippaux JP, Chippaux A. Yellow fever in Africa and the Americas: a historical and epidemiological perspective. J Venom Anim Toxins Incl Trop Dis 2018;24:20. [CrossRef]

- Chen LH, Wilson ME. Yellow fever control: current epidemiology and vaccination strategies. Trop Dis Travel Med Vaccines 2020;6:1. [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Figueiredo P, Stoffella-Dutra AG, Barbosa Costa G, Silva de Oliveira J, Dourado Amaral C, Duarte Santos J, et al. Re-Emergence of Yellow Fever in Brazil during 2016-2019: Challenges, Lessons Learned, and Perspectives. Viruses 2020;12.

- Nomhwange T, Jean Baptiste AE, Ezebilo O, Oteri J, Olajide L, Emelife K, et al. The resurgence of yellow fever outbreaks in Nigeria: a 2-year review 2017-2019. BMC Infect Dis 2021;21:1054. [CrossRef]

- Diagne MM, Ndione MHD, Gaye A, Barry MA, Diallo D, Diallo A, et al. Yellow Fever Outbreak in Eastern Senegal, 2020-2021. Viruses 2021;13. [CrossRef]

- Salomon OD, Arias AR. The second coming of urban yellow fever in the Americas: looking the past to see the future. An Acad Bras Cienc 2022;94:e20201252.

- Zhao S, Stone L, Gao D, He D. Modelling the large-scale yellow fever outbreak in Luanda, Angola, and the impact of vaccination. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2018;12:e0006158. [CrossRef]

- Mensah EA, Gyasi SO, Nsubuga F, Alali WQ. A proposed One Health approach to control yellow fever outbreaks in Uganda. One Health Outlook 2024;6:9. [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Martínez Y, Patiño-Barbosa AM, Rodriguez-Morales AJ. Yellow fever in the Americas: the growing concern about new epidemics. F1000Research 2017;6. [CrossRef]

- Cunha MdP, Duarte-Neto AN, Pour SZ, Ortiz-Baez AS, Černý J, Pereira BBdS, et al. Origin of the São Paulo Yellow Fever epidemic of 2017–2018 revealed through molecular epidemiological analysis of fatal cases. Scientific Reports 2019;9.

- Tomori O. Yellow fever: the recurring plague. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci 2004;41:391-427.

- Faria NR, Kraemer MU, Hill SC, Góes de Jesus J, Aguiar Rd, Iani FC, et al. Genomic and epidemiological monitoring of yellow fever virus transmission potential. Science 2018;361:894-9. [CrossRef]

- do Carmo Cupertino M, Garcia R, Gomes AP, de Paula SO, Mayers N, Siqueira-Batista R. Epidemiological, prevention and control updates of yellow fever outbreak in Brazil. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine 2019;12:49-59. [CrossRef]

- Collins ND, Barrett AD. Live Attenuated Yellow Fever 17D Vaccine: A Legacy Vaccine Still Controlling Outbreaks In Modern Day. Curr Infect Dis Rep 2017;19:14. [CrossRef]

- Kraemer MU, Faria NR, Reiner RC, Golding N, Nikolay B, Stasse S, et al. Spread of yellow fever virus outbreak in Angola and the Democratic Republic of the Congo 2015–16: a modelling study. The Lancet infectious diseases 2017;17:330-8. [CrossRef]

- Thomas C, Michaud C, Gaillet M, Carrión-Nessi FS, Forero-Peña DA, Lacerda MVG, et al. Yellow Fever Reemergence Risk in the Guiana Shield: a Comprehensive Review of Cases Between 1990 and 2022. Current Tropical Medicine Reports 2023;10:138-45. [CrossRef]

- Wasserman S, Tambyah PA, Lim PL. Yellow fever cases in Asia: primed for an epidemic. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2016;48:98-103.

- Ndeffo-Mbah ML, Pandey A. Global Risk and Elimination of Yellow Fever Epidemics. J Infect Dis 2020;221:2026-34. [CrossRef]

- Jean K, Hamlet A, Benzler J, Cibrelus L, Gaythorpe KAM, Sall A, et al. Eliminating yellow fever epidemics in Africa: Vaccine demand forecast and impact modelling. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2020;14:e0008304. [CrossRef]

- Silva T, Nogueira de Sa A, Prates EJS, Rodrigues DE, Silva T, Matozinhos FP, et al. Yellow fever vaccination before and during the covid-19 pandemic in Brazil. Rev Saude Publica 2022;56:45.

- Casey RM, Harris JB, Ahuka-Mundeke S, Dixon MG, Kizito GM, Nsele PM, et al. Immunogenicity of Fractional-Dose Vaccine during a Yellow Fever Outbreak - Final Report. N Engl J Med 2019;381:444-54. [CrossRef]

- Doshi RH, Mukadi PK, Casey RM, Kizito GM, Gao H, Nguete UB, et al. Immunological response to fractional-dose yellow fever vaccine administered during an outbreak in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo: results 5 years after vaccination from a prospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2024;24:611-8. [CrossRef]

- Nnaji CA, Shey MS, Adetokunboh OO, Wiysonge CS. Immunogenicity and safety of fractional dose yellow fever vaccination: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccine 2020;38:1291-301. [CrossRef]

- Vannice K, Wilder-Smith A, Hombach J. Fractional-Dose Yellow Fever Vaccination - Advancing the Evidence Base. N Engl J Med 2018;379:603-5. [CrossRef]

- Roukens AHE, Visser LG. Fractional-dose yellow fever vaccination: an expert review. J Travel Med 2019;26. [CrossRef]

- Manikandan S, Mathivanan A, Bora B, Hemaladkshmi P, Abhisubesh V, Poopathi S. A review on vector borne disease transmission: Current strategies of mosquito vector control. Indian Journal of Entomology 2023;503-13. [CrossRef]

- Kleinert RDV, Montoya-Diaz E, Khera T, Welsch K, Tegtmeyer B, Hoehl S, et al. Yellow Fever: Integrating Current Knowledge with Technological Innovations to Identify Strategies for Controlling a Re-Emerging Virus. Viruses 2019;11. [CrossRef]

- Garske T, Van Kerkhove MD, Yactayo S, Ronveaux O, Lewis RF, Staples JE, et al. Yellow Fever in Africa: estimating the burden of disease and impact of mass vaccination from outbreak and serological data. PLoS Med 2014;11:e1001638. [CrossRef]

- Raimundo SM, Yang HM, Massad E. Modeling Vaccine Preventable Vector-Borne Infections: Yellow Fever as a Case Study. Journal of Biological Systems 2016;24:193-216. [CrossRef]

- Hansen CA, Barrett ADT. The Present and Future of Yellow Fever Vaccines. Pharmaceuticals 2021;14. [CrossRef]

- Medina-Magues LG, Muhe J, Jasny E, Medina-Magues ES, Roth N, Lopera-Madrid J, et al. Immunogenicity and protective activity of mRNA vaccine candidates against yellow fever virus in animal models. NPJ Vaccines 2023;8:31. [CrossRef]

- Monath TP, Seligman SJ, Robertson JS, Guy B, Hayes EB, Condit RC, et al. Live virus vaccines based on a yellow fever vaccine backbone: standardized template with key considerations for a risk/benefit assessment. Vaccine 2015;33:62-72. [CrossRef]

- Al-Halifa S, Gauthier L, Arpin D, Bourgault S, Archambault D. Nanoparticle-Based Vaccines Against Respiratory Viruses. Front Immunol 2019;10:22. [CrossRef]

- Servadio JL, Munoz-Zanzi C, Convertino M. Environmental determinants predicting population vulnerability to high yellow fever incidence. R Soc Open Sci 2022;9:220086. [CrossRef]

- Adrien N, Hyde TB, Gacic-Dobo M, Hombach J, Krishnaswamy A, Lambach P. Differences between coverage of yellow fever vaccine and the first dose of measles-containing vaccine: A desk review of global data sources. Vaccine 2019;37:4511-7. [CrossRef]

- Wu JT, Peak CM, Leung GM, Lipsitch M. Fractional dosing of yellow fever vaccine to extend supply: a modelling study. The Lancet 2016;388:2904-11. [CrossRef]

- Gubler DJ, Almeida MAB, Cardoso JdC, dos Santos E, da Fonseca DF, Cruz LL, et al. Surveillance for Yellow Fever Virus in Non-Human Primates in Southern Brazil, 2001–2011: A Tool for Prioritizing Human Populations for Vaccination. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2014;8.

- Selemane I. Epidemiological monitoring of the last outbreak of yellow fever in Brazil - An outlook from Portugal. Travel Med Infect Dis 2019;28:46-51. [CrossRef]

- Andrade MS, Campos FS, Oliveira CH, Oliveira RS, Campos AAS, Almeida MAB, et al. Fast surveillance response reveals the introduction of a new yellow fever virus sub-lineage in 2021, in Minas Gerais, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2022;117:e220127. [CrossRef]

- Hyde TB, Andrus JK, Dietz VJ, Integrated All VPDSWG, Andrus JK, Hyde TB, et al. Critical issues in implementing a national integrated all-vaccine preventable disease surveillance system. Vaccine 2013;31 Suppl 3:C94-8. [CrossRef]

- Zhao Y, Zhang X, Shu S, Sun Y, Feng X, Zhang S. Yellow Fever: A Re-Emerging Threat. Health 2018;10:1431-48. [CrossRef]

- Cruz ACR, Hernandez LHA, Aragao CF, da Paz TYB, da Silva SP, da Silva FS, et al. The Importance of Entomo-Virological Investigation of Yellow Fever Virus to Strengthen Surveillance in Brazil. Trop Med Infect Dis 2023;8.

- Aliaga-Samanez A, Real R, Segura M, Marfil-Daza C, Olivero J. Yellow fever surveillance suggests zoonotic and anthroponotic emergent potential. Commun Biol 2022;5:530. [CrossRef]

- Mantilla-Granados JS, Sarmiento-Senior D, Manzano J, Calderon-Pelaez MA, Velandia-Romero ML, Buitrago LS, et al. Multidisciplinary approach for surveillance and risk identification of yellow fever and other arboviruses in Colombia. One Health 2022;15:100438. [CrossRef]

- Williams DT, Mackenzie JS, Bingham J. Flaviviruses. Diseases of swine 2019;530-43.

- Subramaniam KS, Lant S, Goodwin L, Grifoni A, Weiskopf D, Turtle L. Two Is Better Than One: Evidence for T-Cell Cross-Protection Between Dengue and Zika and Implications on Vaccine Design. Front Immunol 2020;11:517. [CrossRef]

- Zuckerman JN, Hatz C, Kantele A. Review of current typhoid fever vaccines, cross-protection against paratyphoid fever, and the European guidelines. Expert Rev Vaccines 2017;16:1029-43. [CrossRef]