Submitted:

05 June 2025

Posted:

05 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Background Work

3. Methods

3.1. Algorithm Description

|

|

4. Results

5. Conclusions and Future Work

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | |

| 2 | |

| 3 | |

| 4 |

References

- Bardas, G.; Astaras, S.; Diamantas, S.; Pnevmatikakis, A. 3D tracking and classification system using a monocular camera. Wireless Personal Communications 2017, 92, 63–85.

- Diamantas, S.; Alexis, K. Optical Flow Based Background Subtraction with a Moving Camera: Application to Autonomous Driving. In Advances in Visual Computing. ISVC 2020. Lecture Notes in Computer Science; et al, G.B., Ed.; Springer Nature Switzerland, 2020.

- KaewTraKulPong, P.; Bowden, R. An Improved Adaptive Background Mixture Model for Real-time Tracking with Shadow Detection. In Video-Based Surveillance Systems; Springer US, 2002; chapter 11, pp. 135–144.

- Chen, M.; Yang, Q.; Li, Q.; Wang, G.; Yang, M.H. Spatiotemporal Background Subtraction Using Minimum Spanning Tree and Optical Flow. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), 2014.

- NVIDIA. https://www.nvidia.com/en-gb/graphics-cards/, 2021.

- CUDA. https://developer.nvidia.com/cuda-toolkit, 2021.

- Diamantas, S.; Alexis, K. Modeling Pixel Intensities with Log-Normal Distributions for Background Subtraction. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Imaging Systems and Techniques, Beijing, China, 2017; pp. 1–6.

- Stauffer, C.; Grimson, W.E.L. Adaptive Background Mixture Models for Real-Time Tracking. In Proceedings of the 1999 Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR ’99), 23-25 June 1999, Ft. Collins, CO, USA, 1999, pp. 2246–2252. [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Ellis, T. Illumination-invariant motion detection using colour mixture models. In Proceedings of the British Machine Vision Conference (BMVC 2001), 2001, pp. 163–172.

- Zivkovic, Z. Improved Adaptive Gaussian Mixture Model for Background Subtraction. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Pattern Recognition, ICPR 2004, Cambridge, UK, August 23-26, 2004., 2004, pp. 28–31. [CrossRef]

- Zivkovic, Z.; van der Heijden, F. Efficient adaptive density estimation per image pixel for the task of background subtraction. Pattern Recognition Letters 2006, 27, 773–780.

- Elgammal, A.; Duraiswami, R.; Harwood, D.; Davis, L.S. Background and Foreground Modeling Using Nonparametric Kernel Density Estimation for Visual Surveillance. In Proceedings of the Proceeding of the IEEE, November 2002, Vol. 90, pp. 1151–1163.

- Heikkilä, M.; Pietikäinen, M. A Texture-Based Method for Modeling the Background and Detecting Moving Objects. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2006, 28, 657–662. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Park, M. An Adaptive Background Subtraction Method Based on Kernel Density Estimation. Sensors 2012, 12, 12279–12300.

- Barnich, O.; Droogenbroeck, M.V. ViBe: A Universal Background Subtraction Algorithm for Video Sequences. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2011, 20, 1709–1724. [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Hu, W.; Liu, J.; Yang, M.; Wei, B.; Chou, C.T. Efficient background subtraction for real-time tracking in embedded camera networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 10th ACM Conference on Embedded Network Sensor Systems, 2012, pp. 295–308.

- Tabkhi, H.; Bushey, R.; Schirner, G. Algorithm and architecture co-design of Mixture of Gaussian (MoG) background subtraction for embedded vision. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of Asilomar Conference on Signals, Systems and Computers, Pacific Grove, CA, USA, 2013.

- Godbehere, A.B.; Matsukawa, A.; Goldberg, K.Y. Visual tracking of human visitors under variable-lighting conditions for a responsive audio art installation. In Proceedings of the American Control Conference, ACC 2012, Montreal, QC, Canada, June 27-29, 2012, 2012, pp. 4305–4312.

- Yao, J.; Odobez, J.M. Multi-Layer Background Subtraction Based on Color and Texture. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR 2007), 18-23 June 2007, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA, 2007. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Tabkhi, H.; Schirner, G. A GPU-Based Algorithm-Specific Optimization for High-Performance Background Subtraction. In Proceedings of the 2014 43rd International Conference on Parallel Processing, 2014, pp. 182–191. [CrossRef]

- Szwoch, G.; Ellwart, D.; Czyżewski, A. Parallel implementation of background subtraction algorithms for real-time video processing on a supercomputer platform. Journal of Real-Time Image Processing 2016, 11, 111–125.

- Braham, M.; Droogenbroeck, M.V. Deep Background Subtraction with Scene-Specific Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the The 23rd International Conference on Systems, Signals and Image Processing, 2016.

- Rai, N.K.; Chourasia, S.; Sethi, A. An Efficient Neural Network Based Background Subtraction Method. In Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Bansal, J.; Singh, P.; Deep, K.; Nagar, M.P.A., Eds.; Springer, 2013; pp. 453–460.

- Radke, R.J.; Andra, S.; Al-Kofahi, O.; Roysam, B. Image Change Detection Algorithms: A Systematic Survey. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2005, 14, 294–307. [CrossRef]

- Candès, E.J.; Li, X.; Ma, Y.; Wright, J. Robust Principal Component Analysis? Journal of the ACM 2011, 58, 11:1–11:37. [CrossRef]

- Bouwmans, T.; Sobral, A.; Javed, S.; Jung, S.K.; Zahzah, E. Decomposition into Low-Rank plus Additive Matrices for Background/Foreground Separation: A Review for a comparative evaluation with a large-scale dataset. Computer Science Review 2017, 23, 1–71. [CrossRef]

- Yong, H.; Meng, D.; Zuo, W.; Zhang, L. Robust Online Matrix Factorization for Dynamic Background Subtraction. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2018, 40, 1726–1740. [CrossRef]

- Giraldo, J.H.; Bouwmans, T. GraphBGS: Background Subtraction via Recovery of Graph Signals. In Proceedings of the 2020 25th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR), 2021, pp. 6881–6888. [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, M.; Tiefenbacher, P.; Rigoll, G. Background Segmentation with Feedback: The Pixel-Based Adaptive Segmenter. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, 2012, pp. 38–43. [CrossRef]

- Sobral, A.; Vacavant, A. A Comprehensive Review of Background Subtraction Algorithms Evaluated with Synthetic and Real Videos. Computer Vision and Image Understanding 2014, 122, 4–21. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jodoin, P.M.; Porikli, F.; Konrad, J.; Benezeth, Y.; Ishwar, P. CDnet 2014: An Expanded Change Detection Benchmark Dataset. In Proceedings of the Proc. IEEE CVPR Workshops, 2014, pp. 393–400.

- Bouwmans, T.; Javed, S.; Sultana, M.; Jung, S.K. Deep Neural Network Concepts for Background Subtraction: A Systematic Review and Comparative Evaluation. Neural Networks 2019, 117, 8–66. [CrossRef]

- Braham, M.; Van Droogenbroeck, M. Deep Background Subtraction with Scene-Specific Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the Proc. Intl. Conf. on Systems, Signals and Image Processing (IWSSIP), 2016, pp. 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Babaee, M.; Dinh, D.T.; Rigoll, G. A Deep Convolutional Neural Network for Video Sequence Background Subtraction. Pattern Recognition 2018, 76, 635–649. [CrossRef]

- Lim, L.A.; Keleş, H.Y. Learning Multi-Scale Features for Foreground Segmentation. Pattern Analysis and Applications 2020, 23, 1369–1380. [CrossRef]

- Cioppa, A.; Van Droogenbroeck, M.; Braham, M. Real-Time Semantic Background Subtraction. In Proceedings of the Proc. IEEE Intl. Conf. on Image Processing (ICIP), 2020, pp. 3214–3218. [CrossRef]

- Tezcan, M.O.; Ishwar, P.; Konrad, J. BSUV-Net: A Fully-Convolutional Neural Network for Background Subtraction of Unseen Videos. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), 2020, pp. 2763–2772. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Tabkhi, H.; Schirner, G. A GPU-Based Algorithm-Specific Optimization for High-Performance Background Subtraction. In Proceedings of the Proc. Intl. Conf. on Parallel Processing (ICPP), 2014, pp. 182–191. [CrossRef]

- Karagöz, M.F.; Aktas, M.; Akgün, T. CUDA implementation of ViBe background subtraction algorithm on jetson TX1/TX2 modules. In Proceedings of the 2018 26th Signal Processing and Communications Applications Conference (SIU), 2018, pp. 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Kryjak, T.; Gorgon, M. Real-Time Implementation of Background Modelling Algorithms in FPGA Devices. In New Trends in Image Analysis and Processing – ICIAP 2015 Workshops; Springer, 2015; Vol. 9281, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, pp. 519–526. [CrossRef]

- Sehairi, K.; Chouireb, F. Implementation of Motion Detection Methods on Embedded Systems: A Performance Comparison. International Journal of Technology 2023, 14, 510–521. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Zhu, L.; Qin, S.; Yu, Y.; Ju, R.; Li, Q. Road Surface Defect Detection Algorithm Based on YOLOv8. Electronics 2024, 13, 2413. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Meng, R.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, L.; Huo, L.; Qiao, Z.; Niu, C. Road Defect Detection Based on Improved YOLOv8s Model. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 16758. [CrossRef]

- Deebgaze Computer Vision library. https://github.com/mpatacchiola/deepgaze, 2017.

- OpenCV. http://opencv.willowgarage.com/wiki/, 2017.

- MARE’s Computer Vision Study. http://study.marearts.com/, 2017.

- Diamantas, S. Biological and Metric Maps Applied to Robot Homing. PhD thesis, School of Electronics and Computer Science, University of Southampton, 2010.

- Diamantas, S.C.; Oikonomidis, A.; Crowder, R.M. Towards Optical Flow-Based Robotic Homing. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IEEE World Congress on Computational Intelligence), Barcelona, Spain, 2010.

- Diamantas, S.C.; Oikonomidis, A.; Crowder, R.M. Depth Computation Using Optical Flow and Least Squares. In Proceedings of the IEEE/SICE International Symposium on System Integration, Sendai, Japan, 2010; pp. 7–12.

| Variable | Description |

|---|---|

| Total number of pixels per frame, | |

| calculated as frame width × frame height. | |

| Current pixel index. | |

| Total number of frames in the buffer. | |

| Sum of all pixel intensities | |

| across frames for given coordinates . | |

| Mean pixel intensity at over all frames. | |

| Log-normal Buffer | |

| Sum of all pixel intensities across . | |

| Median of | |

| Standard deviation of . |

| Variable | Description |

|---|---|

| Total number of pixels per frame, | |

| calculated as frame width × frame height. | |

| latest frame to be processed. | |

| log-normalized buffer frame | |

| (i.e. equation 5) | |

| input variability amount | |

| background subtracted image |

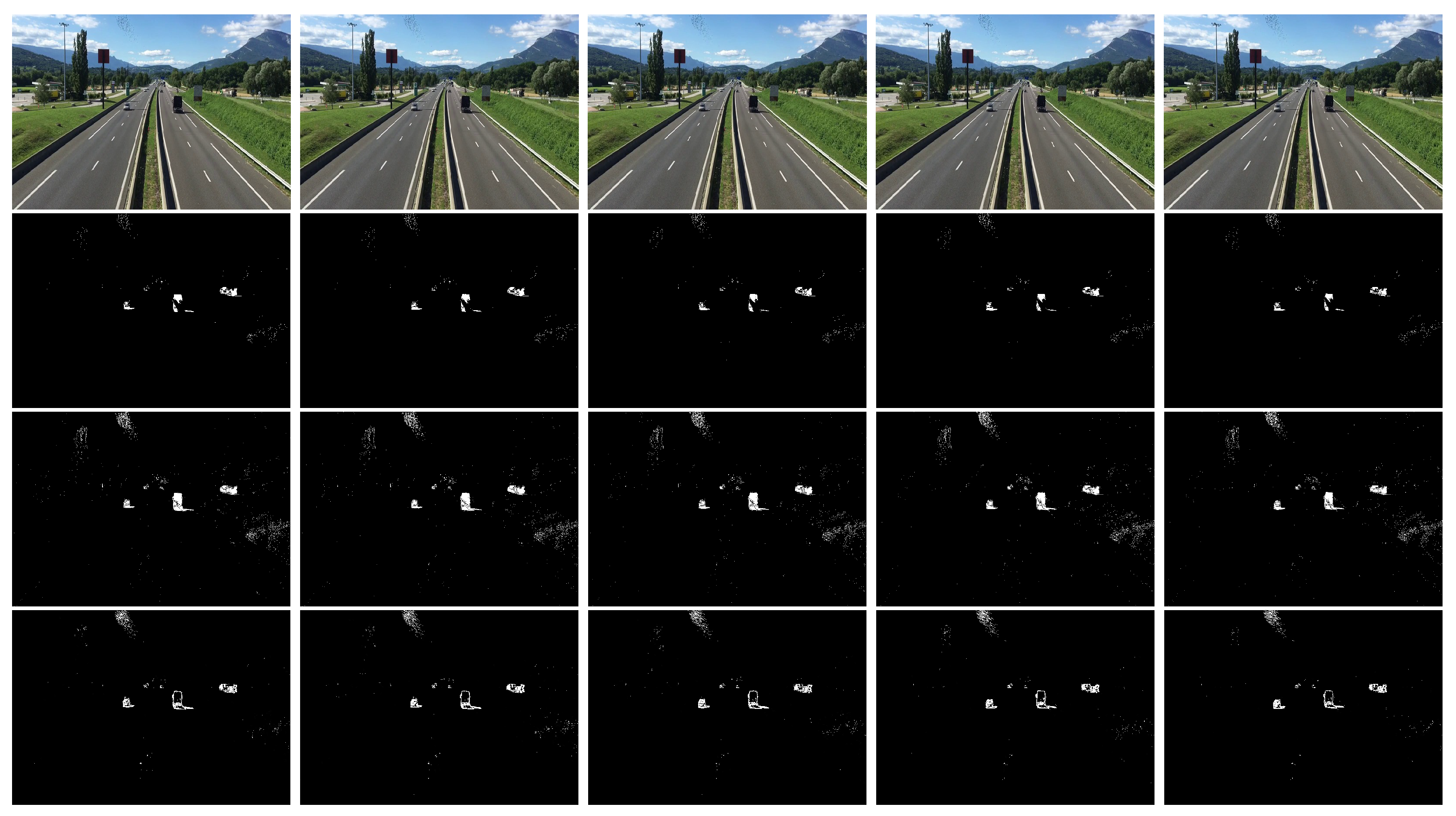

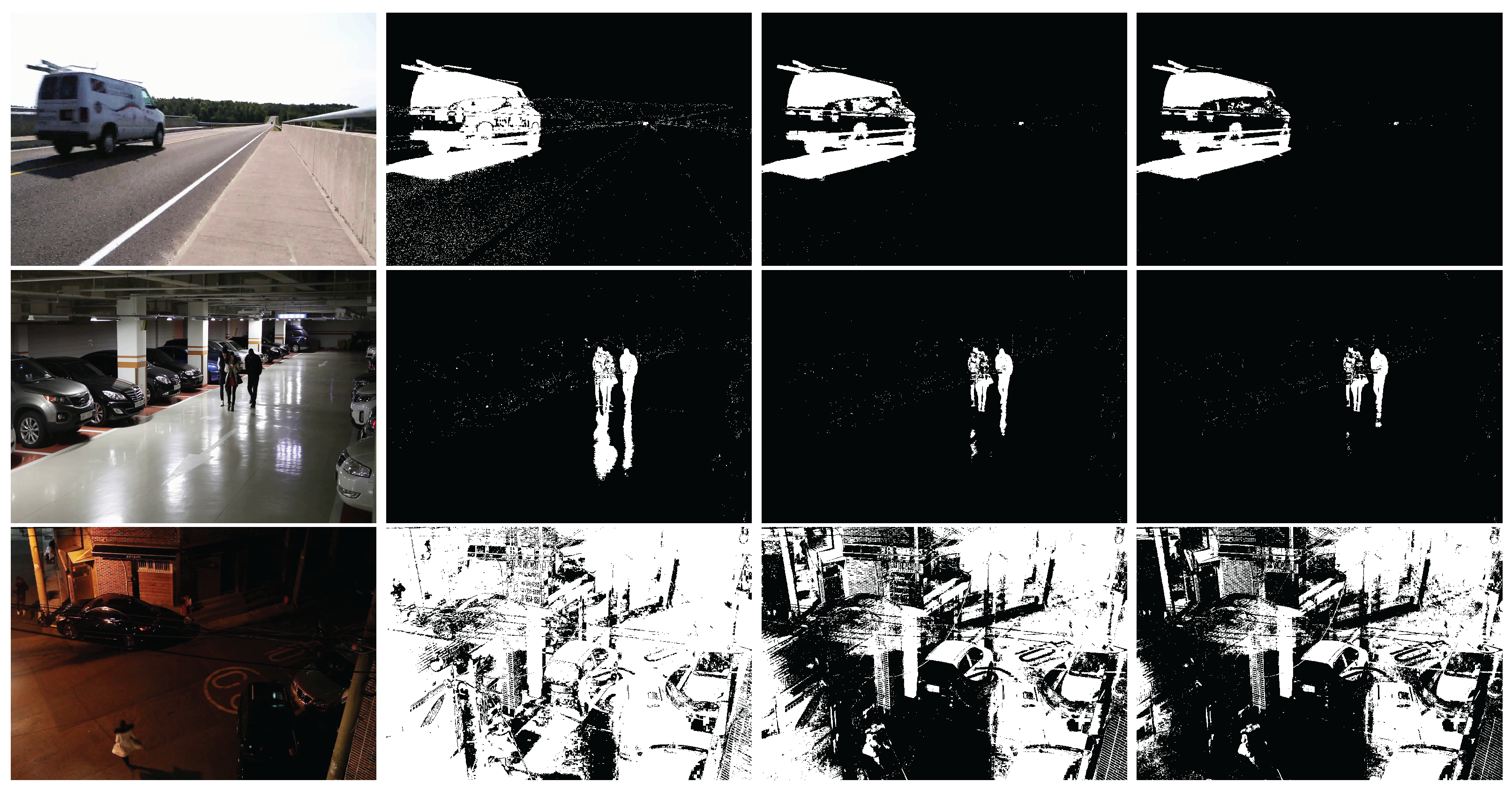

| Dataset (resolution) | 3-frame buffer | 8-frame buffer | 10-frame buffer | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time [ms] | fps | Time [ms] | fps | Time [ms] | fps | |

| cars (1920 × 1080) | 19.61 | 51.0 | 23.64 | 42.3 | 23.96 | 41.7 |

| cctv1 (1920 × 1080) | 19.85 | 50.4 | 23.89 | 41.9 | 24.26 | 41.2 |

| cctv5 (1920 × 1080) | 20.26 | 49.4 | 25.82 | 38.7 | 27.69 | 36.1 |

| highway (1280 × 720) | 10.80 | 92.6 | 13.63 | 73.3 | 14.20 | 70.4 |

| Buffer size = number of previous frames kept in memory for temporal reasoning. | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).