2. Literature Review and Theoretical Background

Expected Utility Theory (EU) is the traditional framework for modeling investor behavior under risk. It assumes that rational agents choose among risky alternatives to maximize the expected value of a utility function, subject to axioms such as completeness, transitivity, continuity, and independence [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Despite its theoretical elegance and normative appeal, EU has limited empirical support. Systematic violations of its axioms have been observed, especially when individuals exhibit inconsistent attitudes toward risk. For example, preferences often reverse depending on whether outcomes are framed as gains or losses, and individuals frequently display risk aversion for gains and risk-seeking for losses, contrary to EU predictions [

8,

9,

10].

To address these violations, Kahneman and Tversky [

11] developed Prospect Theory (PT), which has become a cornerstone of behavioral economics. PT models decision-making under risk based on changes in wealth relative to a reference point rather than final outcomes. It introduces a value function that is concave for gains and convex for losses, and steeper for losses than for gains, capturing the phenomenon known as loss aversion—meaning that losses loom larger than equivalent gains. In addition, PT proposes a probability weighting function, in which small probabilities tend to be overweighted and large probabilities underweighted, further departing from the linear treatment of probabilities in EU. These features allow PT to explain several empirical anomalies, including the certainty effect, isolation effect, and framing effects [

12,

13,

14].

Loss aversion plays a central role in explaining behavioral anomalies such as the disposition effect, which refers to the tendency of investors to sell winning assets too early and hold on to losing ones for too long [

15,

16]. In the context of PT, this pattern arises because individuals evaluate outcomes relative to a reference point, often the purchase price, and become risk-averse when facing gains and risk-seeking when facing losses. A gain relative to the reference point feels satisfactory and motivates realization, while a loss feels painful and leads the investor to hold the asset in the hope of recovery. As a result, decisions are not based solely on expected utility or updated probabilities but are influenced by emotional responses to perceived gains and losses.

Empirical evidence for the disposition effect has been documented both in real trading environments and in laboratory experiments [

17,

18]. The literature suggests that this bias is robust across contexts and is associated with suboptimal portfolio performance, particularly in volatile markets. While PT provides a theoretical explanation for the disposition effect, it does not preclude the coexistence of other belief-driven behaviors that influence investment decisions. One such belief, which may interact or even conflict with loss aversion, is the hot-hand belief: the expectation that recent success is likely to continue, even in the absence of objective autocorrelation. Understanding how these behavioral forces operate together is essential to capture the complexity of investor behavior in dynamic financial environments.

Originally studied in the context of sports, the hot-hand belief is commonly interpreted as a cognitive illusion, resulting from representativeness heuristics, whereby people expect short random sequences to resemble the long-run properties of the process that generated them [

19,

20]. In this view, individuals tend to overinfer from small samples, treating recent outcomes as informative signals of ability or trend, even in purely random environments. As a result, they may form expectations of continued success based solely on prior streaks, regardless of the objective statistical structure of the situation.

This cognitive bias leads individuals to perceive patterns or momentum where none exists, particularly when the underlying process is governed by independent random draws. In this view, the hot-hand belief is closely related to the misperception of randomness, and it emerges from a broader tendency to overinfer from small samples [

19], anchoring judgments on recent outcomes and exhibiting overconfidence in perceived personal performance [

21]. These mechanisms are well documented in cognitive psychology and form the foundation for understanding how beliefs like the hot-hand can arise even in environments characterized by objective unpredictability. Importantly, they help explain why such beliefs persist despite contradictory evidence, especially when individuals receive performance feedback that appears to confirm their expectations.

The most influential empirical investigation of the hot-hand belief was conducted by Gilovich, Vallone, and Tversky [

22]. Using player statistics from professional basketball games and survey responses from fans and coaches, the authors tested whether success in prior shots increased the likelihood of subsequent success. Despite widespread belief among participants that players could become “hot,” their analysis found no evidence of actual positive autocorrelation in shooting performance. They concluded that the hot-hand was a cognitive illusion, a product of misperceiving random sequences, and introduced the concept of the “hot-hand fallacy” to describe this mismatch between belief and reality. Their findings became a cornerstone in the literature on judgment under uncertainty and were widely cited as evidence of systematic errors in human reasoning about chance.

More than three decades after the original study, Miller and Sanjurjo [

23] revisited the statistical methodology used by Gilovich, Vallone, and Tversky and demonstrated that their conclusions were affected by a subtle but systematic bias. The original analysis underestimated the likelihood of success following streaks due to a selection bias that arises when computing conditional probabilities in finite sequences. Specifically, they showed that in a sequence of random outcomes, the empirical probability of success following previous successes is expected to be lower than the true probability, even when outcomes are independent. After correcting for this bias, Miller and Sanjurjo found statistically significant evidence of a hot-hand effect in the same basketball data previously analyzed. Their findings reignited the debate and prompted a broader reexamination of how the hot-hand belief is measured and interpreted in empirical studies.

In the field of finance, the hot-hand belief has also been studied as a factor influencing investor behavior, particularly in contexts where individuals evaluate the recent performance of third parties such as fund managers or financial “experts.” Several studies have documented that investors tend to allocate more resources to mutual funds that have performed well in the recent past, a behavior interpreted as evidence of hot-hand belief [

1,

2]. In these cases, the belief is modeled as exogenous to the decision-maker. That is, the investor does not believe in their own streakiness, but rather attributes skill or predictive power to the recent success of others. This framework is conceptually similar to the hot-hand belief in sports, where spectators believe that a player who has made several successful shots is more likely to continue performing well. Experimental studies such as Huber et al. [

3] further support this interpretation by showing that participants favor options associated with recent success, even when outcomes are generated by randomized processes.

While prior research has typically treated the hot-hand belief as an exogenous perception about others, our study investigates whether this belief can emerge endogenously from the investor’s own experience. Instead of observing the past performance of external agents, participants in our experiment make repeated portfolio decisions and receive direct feedback on their outcomes. This setup allows us to test whether personal streaks of success lead individuals to expect continued favorable results, even when asset prices follow a purely random process. This approach provides a unique opportunity to isolate the formation of the belief and observe its persistence or attenuation over time, particularly in interaction with other behavioral forces such as loss aversion.

4. Results and Discussion

To test Hypothesis 1, we analyzed the average values of the two indices, and , which measure participants’ propensity to increase purchases following previous gains in price or performance. The Shapiro-Wilk normality test indicated that the distributions of both indices significantly deviated from normality (). As a result, we applied the Wilcoxon signed-rank test with continuity correction to assess whether their mean values differed from zero.

The analysis was conducted across five time blocks. The first block included all decisions made during the initial (pre-incentive) stage, labeled as “<1.” The following three blocks corresponded to sequential three-round intervals in the second stage (1–4, 4–7, and 7–10). The final block (1–10) aggregated the full second stage. Results are reported in

Table 2.

In the first stage, both indices exhibited positive average values that were statistically different from zero. The mean for was 0.27, and for , 0.28. These results indicate that participants were more likely to increase their purchases following either a price increase or a prior gain, compared to after a decrease or a loss. Such behavior is consistent with the presence of hot-hand belief in portfolio decisions during the early phase of the experiment.

The results suggest that participants’ propensity to buy was moderately influenced by recent price changes, showing a positive correlation with past outcomes regardless of direction. A higher frequency of success appeared to reinforce the hot-hand belief, especially in the early stages. However, this effect weakened when participants were exposed to persistent negative price trends. In those situations, loss aversion increasingly shaped portfolio decisions, overriding the hot-hand pattern. These shifts in behavior, driven by evolving market feedback and performance perception, reflect an endogenous process of portfolio rebalancing over time.

Our approach to measuring the hot-hand effect differs substantially from those used in prior studies such as Hendricks et al. [

1], Sundali and Croson [

37], and Huber et al. [

3]. These works typically assess the belief in streaks by observing participants’ preferences for third-party agents, such as investment fund managers or randomized “experts,” following a sequence of successful outcomes. In contrast, our experiment was designed to evaluate whether participants form hot-hand beliefs based on their own performance in a multi-asset portfolio environment. This conceptual shift, from belief attribution about others to belief formation through personal feedback, required a different empirical strategy.

In the context of dynamic portfolio decisions involving multiple assets and automatic liquidation, participants do not simply choose among predefined alternatives. Instead, they continuously adjust their allocations in response to perceived asset patterns and prior outcomes. To reflect this behavior, we constructed indices that measure proportional differences in asset purchases following gains or losses, or after price increases or decreases. These indices align with the experimental structure and capture how participants incorporate personal histories into their decision-making. Although this method diverges from traditional formulations, it produces consistent and interpretable results. For example, our first-stage estimates of

and

were higher than the disposition effect observed by Weber and Camerer [

16], which was 0.155. This comparison reinforces the relevance and robustness of our approach.

At the beginning of the second stage, the hot-hand effect remained statistically significant, suggesting a continuation of the behavioral pattern observed earlier. This effect, however, reversed between rounds 4 and 7, with both indices becoming negative on average. In the final block (rounds 7-10), the indices returned to positive values, although at lower levels than those recorded at the start of the stage. When aggregated across the entire second stage (rounds 1-10), the average indices converged to zero, indicating that the hot-hand pattern had dissipated over time.

These results suggest that the hot-hand effect was not sustained throughout the experiment. While participants initially adjusted their portfolios in pursuit of positive return patterns, prior successes did not continue to shape their expectations over time. The decline in the hot-hand indices appears to reflect a decreasing propensity to buy after gains. This behavioral shift is consistent with predictions from Prospect Theory, which posits that individuals are reluctant to realize losses and tend to hold onto losing assets while prematurely selling winning ones. The following analyses support this interpretation, particularly in light of the persistent negative trend in the price of asset B during the second stage, which appears to have triggered loss-averse rebalancing behaviors.

Hypothesis 2 posits that participants are more likely to retain or repurchase assets when the current price is above the original purchase price. In the context of automatic liquidation, this behavior translates into a higher likelihood of repurchasing assets after a gain than after a loss, using the purchase price as a natural reference point.

Table 3 presents the total number of shares repurchased under both conditions. The results are broadly consistent with those observed under Hypothesis 1, reinforcing the presence of hot-hand-consistent behavior in the early rounds.

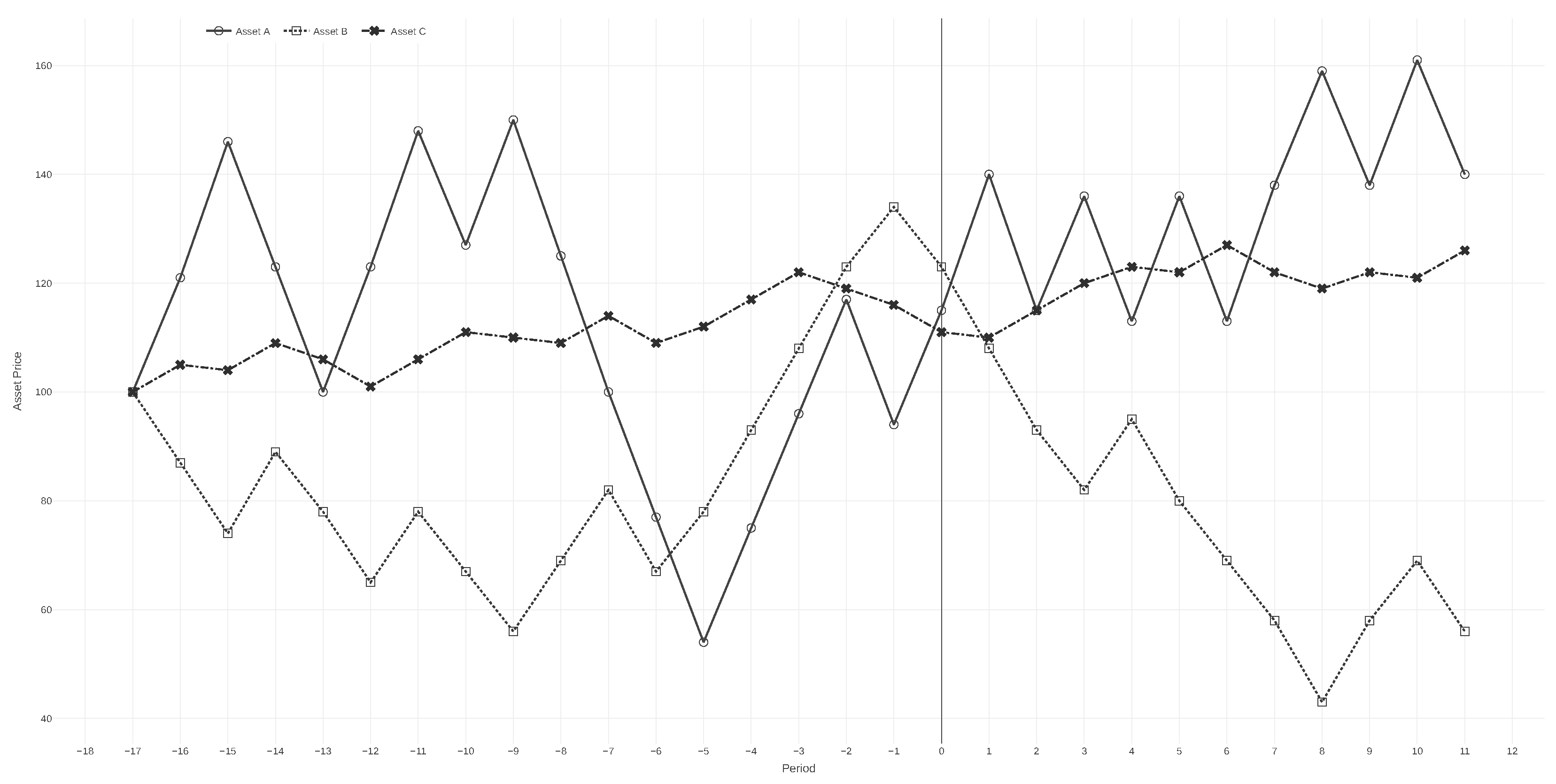

During the first stage and the initial block of the second stage, participants repurchased more than 60% of assets following gains, compared to just under 40% following losses. This asymmetry supports the presence of hot-hand-consistent behavior, in which favorable outcomes reinforce the expectation of continued success. However, stronger evidence of this pattern emerged only for the lower-risk asset (C), where approximately 90% of acquisitions occurred after a gain. Asset C maintained a predominantly positive price trajectory throughout the first stage, with only a minor decline observed in an early round, as shown in

Figure 1. In contrast, asset B experienced a downward trend in the early rounds but recovered later, while asset A exhibited the highest degree of price variability across the experiment.

The distribution of purchases after gains and losses reflects the differing volatility profiles of the three assets. Asset C, which exhibited the lowest price variation and the most frequent gains, accounted for the highest aggregate purchase volume. This was followed by asset B, and then asset A, which had the highest volatility. The pattern suggests that price stability and the recurrence of positive outcomes reinforced participants’ willingness to buy.

The data in

Table 3 further illustrate how the hot-hand effect interacted with loss aversion across different assets. Although the hot-hand effect did not persist across all stages of the experiment, the observed behavior remains consistent with a broader pattern predicted by Prospect Theory: a reluctance to realize losses. This tendency became evident when comparing repurchases following gains and losses. Participants generally exhibited hot-hand-consistent behavior for assets A and C, repurchasing more frequently after favorable outcomes. In contrast, asset B showed an opposite pattern, with acquisitions increasing even as prices declined, suggesting that participants were unwilling to realize losses in the face of a persistent negative trend.

This dynamic became even clearer when examining participants’ selling behavior and the associated profits. Analyses of sales at prices above or below key benchmarks, such as the last observed price or the average price, revealed that participants were more likely to sell profitable assets. Similarly, comparisons between assets kept until the end and those sold earlier showed a greater tendency to hold onto loss-making assets. These findings align with the behavior of a loss-averse investor who prefers to defer losses rather than realize them.

The data in

Table 4 provide further insight into how participants adjusted their purchases based on recent price trends. Overall, individuals tended to increase their buying activity after positive trends and reduce it after negative ones. However, this behavior was not purely reactive. Participants appeared to require repeated favorable signals before reinforcing their belief in trend continuation, revealing a cautious and selective application of the hot-hand belief.

This pattern is particularly evident for asset B during rounds 1 to 8, where purchases following losses dominated the portfolio composition. Such behavior is consistent with loss aversion, as participants may have been reluctant to realize losses despite unfavorable price trends. Although the percentage of purchases following gains increased slightly in the final block (rounds 7-10), the high concentration of losses from asset B likely suppressed the overall effect. For asset B, 33% of purchases followed gains and 67% followed losses, compared to 51% and 49% for asset A, and 59% and 41% for asset C, respectively. Among the three, asset C offered the clearest evidence of hot-hand behavior, particularly through its consistent purchase pattern after gains.

A more nuanced pattern emerged when analyzing the total number of shares repurchased in relation to recent price trends, as reported in

Table 4. The results confirm the continued predominance of asset B in the portfolio composition, particularly in purchases following price declines. Specifically, 67% of purchases of asset B occurred after a price decrease, compared to 33% after an increase. Asset A showed a similar, though slightly more pronounced, pattern, with 72% of purchases following declines and only 28% after increases.

We also compared the average profit of assets that were purchased in any round but never repurchased (referred to as sold assets) with those that were repurchased in every subsequent period until the end of the experiment (kept assets). According to Hypothesis 2, a hot-hand investor would be more likely to keep assets that had generated gains and sell those that had produced losses, while loss aversion would imply the opposite pattern.

Table 5 shows that the average profit for sold assets was R

$ 3.6, whereas the average for kept assets was negative, at negative R

$ 6.0.

This result is largely driven by the behavior surrounding asset B. Its average profit was negative R$ 21 when kept and negative R$ 12 when sold, indicating that participants who held onto the asset experienced substantially greater losses. The magnitude of these losses, and their frequency, likely intensified participants’ aversion to realizing them. Instead of cutting losses, many chose to continue holding the asset, hoping for a reversal. This behavior is consistent with loss aversion rather than hot-hand belief. In contrast, assets A and C exhibited positive average returns in both kept and sold categories, supporting the idea that asset-specific price trends influenced the expression of behavioral biases.

To further explore the relationship between loss aversion and the hot-hand effect, we examined assets that were sold in period

t and not repurchased within the following one or two rounds. These sales reveal how participants responded to short-term price trends.

Table 6 reports the number of net sales in period

t as a function of price movements in the two preceding periods (

and

). Specifically, we classified price sequences into four categories: two consecutive increases (UU), a decrease followed by an increase (DU), an increase followed by a decrease (UD), and two consecutive decreases (DD).

According to Hypothesis 2, if participants follow the hot-hand belief, sales should be less frequent following sequences that signal upward momentum, such as UU or DU.

The results for the second stage indicate that participants’ willingness to sell was sensitive to recent price patterns. Sales were more frequent when a price increase in the most recent period was preceded by a decline (DU), with 43.46% of assets sold in such cases, compared to only 23.46% following an increase then a decrease (UD). Aggregating the data, sequences ending in a price increase (UU and DU) accounted for 58.95% of all sales, while those ending in a decrease (UD and DD) accounted for 41.05

Interestingly, when isolating strictly consistent trends, participants sold less after two consecutive increases (UU: 15.49%) than after two consecutive decreases (DD: 17.59%). This suggests that while positive trends may initially trigger sales, persistent upward sequences are less likely to do so. The pattern partially aligns with the behavior expected of a hot-hand investor, who reacts more strongly to recent gains than to losses, but it also reveals caution in interpreting short streaks as reliable signals.

The results above suggest that the last observed price may act as an inverted reference point in participants’ decisions. Rather than reinforcing the hot-hand effect, this reference may activate loss aversion, making participants more likely to hold onto assets after losses and sell after gains. This behavior effectively attenuates hot-hand-consistent patterns and highlights the influence of emotional biases such as reluctance to realize losses.

To further investigate this mechanism, we tested Hypotheses 3 and 4, which introduce alternative reference points based on historical price benchmarks. Specifically, these hypotheses examine whether participants are more likely to hold assets when the current price is above either the recent average price (Hypothesis 3) or the maximum price observed so far (Hypothesis 4).

Table 7 presents the number of sales in period

t depending on whether the current price was above or below these benchmarks.

These results reveal a pattern consistent with an inverted reference point for the recent average price: participants sold more frequently when the current price exceeded the average. In most blocks, over 56% of sales occurred after the price rose above the average, compared to 44% when it was below. However, this asymmetry was not observed with respect to the maximum price. When the current price was below the maximum, sales were concentrated after recent declines. In the second stage alone, more than 90% of these sales occurred after a price decrease, suggesting that the maximum price did not operate as an inverted reference but possibly as a psychological ceiling or anchor.

Finally, we tested whether participants were more likely to maintain a specific portfolio composition following a streak of favorable outcomes compared to unfavorable ones. According to the hot-hand hypothesis, an investor influenced by recent success would adjust their portfolio by favoring assets with upward trends and low price variability, while avoiding or reducing exposure to volatile assets with declining prices. In this framework, the investor behaves as if past success signals future success, and past failure signals future failure.

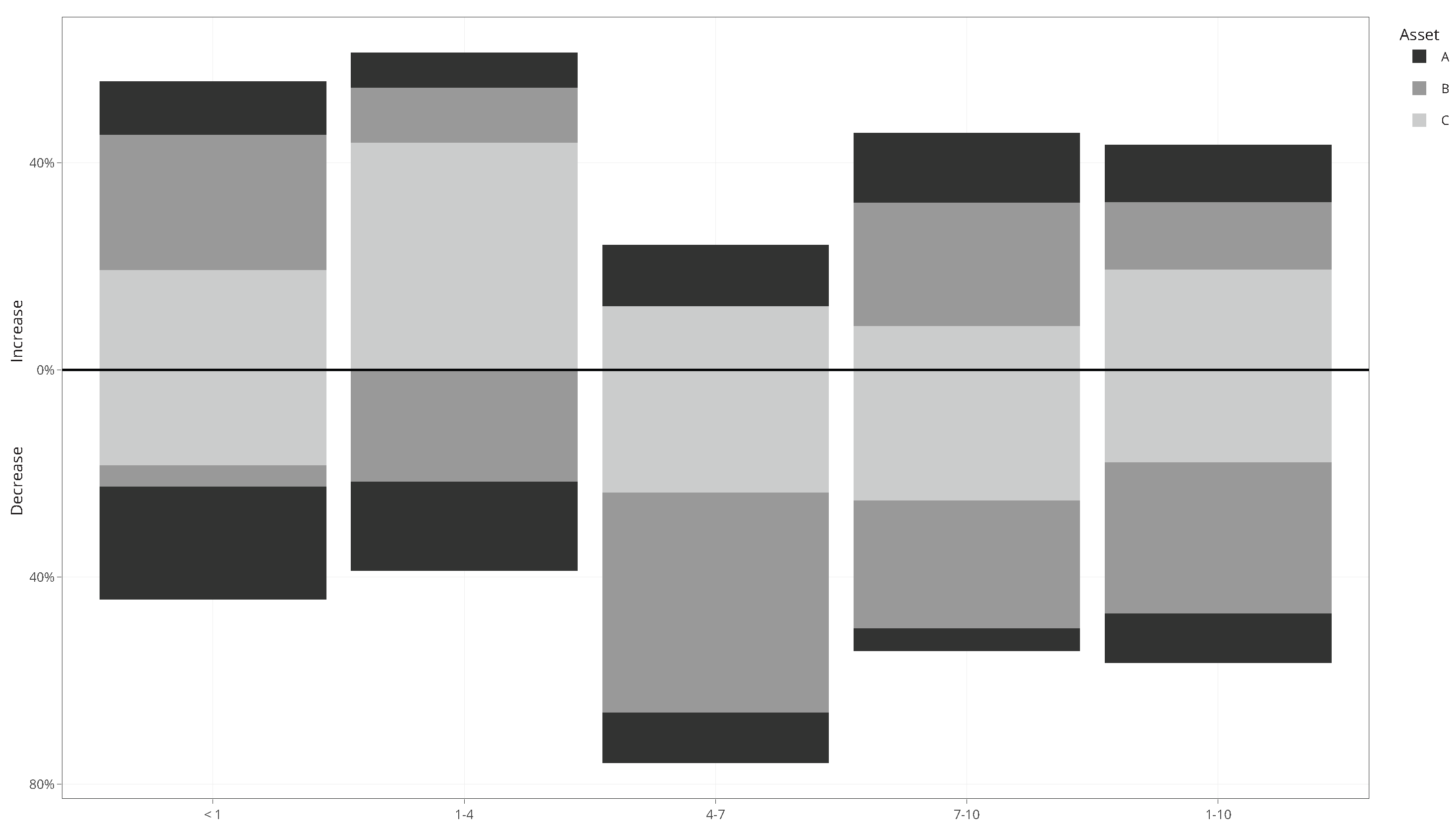

Figure 2 illustrates how the portfolio composition evolved over time, showing the proportion of each asset in purchases made after price increases or decreases. The data are grouped by blocks of rounds, allowing us to compare behavioral patterns across different phases of the experiment.

In the first stage (

) and in the first block of the second stage (rounds 1–4), participants’ choices aligned with the hot-hand effect. Most purchases occurred after price increases, as indicated by bars above the zero line in

Figure 2. In this early phase, asset C accounted for 43.8% of all purchases, coinciding with its positively autocorrelated price path. In contrast, asset B showed a negative trend, and asset A exhibited high variability. Purchases of assets B and A during this block were considerably lower, at 10.7% and 6.7%, respectively.

However, this pattern changed substantially in the middle and final blocks. Between rounds 4 and 7, nearly 43% of all purchases were directed toward asset B, despite its continued negative trend. During this phase, the majority of acquisitions of assets B and C occurred after losses, representing two-thirds of total purchases. This pattern persisted in the final block (rounds 7-10), where post-loss purchases of asset B remained frequent. Overall, asset B accounted for 29.2% of acquisitions throughout the second stage, despite its higher variance and poor performance. This persistent preference suggests a reluctance to realize losses, characteristic of loss aversion, and helps explain the diminishing expression of hot-hand behavior in the later rounds.

The average portfolio composition further highlights a shift away from hot-hand behavior, particularly in response to the performance of asset B. When facing repeated losses and increased price volatility, participants tended to increase their holdings in asset B, despite its negative outlook. This pattern suggests that loss aversion played a dominant role, as investors appeared reluctant to realize losses and instead doubled down in the hope of a recovery.

In contrast, portfolio adjustments for assets A and C followed the pattern expected from hot-hand behavior. Participants increased their holdings in these assets when price trends were positive and reduced their positions when variance rose. These differences help explain the contrasting portfolio trajectories observed for asset B compared to the more consistent behavior seen with assets A and C.

To further validate these patterns, we applied the Wilcoxon rank-sum test to analyze the average number of purchases made after price increases and decreases. The results revealed statistically significant differences in most rounds, confirming that price trends influenced participants’ buying behavior. The exception occurred in the aggregated block covering rounds 1–10, where only asset C showed a significant effect. This finding reinforces the idea that hot-hand behavior was more evident for asset C, whose price dynamics were more stable and upward-trending.

Overall, the composition of participants’ portfolios increased in response to positive price trends and decreased when asset variance was higher. This dynamic helps explain the contrasting behavior between assets A and C, whose proportions moved in opposite directions depending on price conditions, and the persistence of asset B in portfolios despite its poor performance. These patterns support the interpretation that hot-hand behavior influenced investment decisions for some assets, while loss aversion played a stronger role in the continued allocation to asset B. Together, these results provide a nuanced picture of how different behavioral biases interact in dynamic portfolio settings, a theme we return to in the final discussion.