Submitted:

03 June 2025

Posted:

03 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction and Clinical Significance

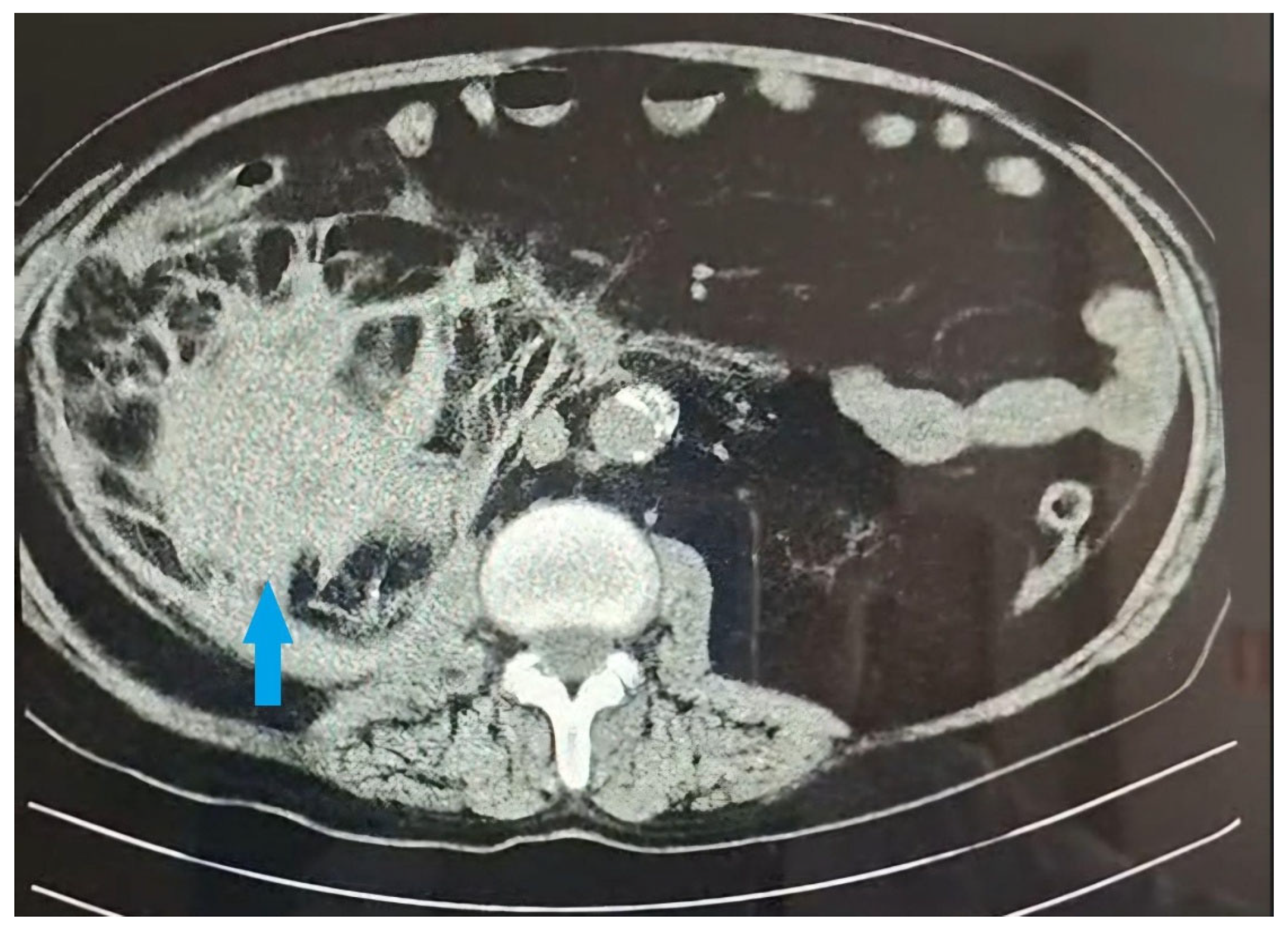

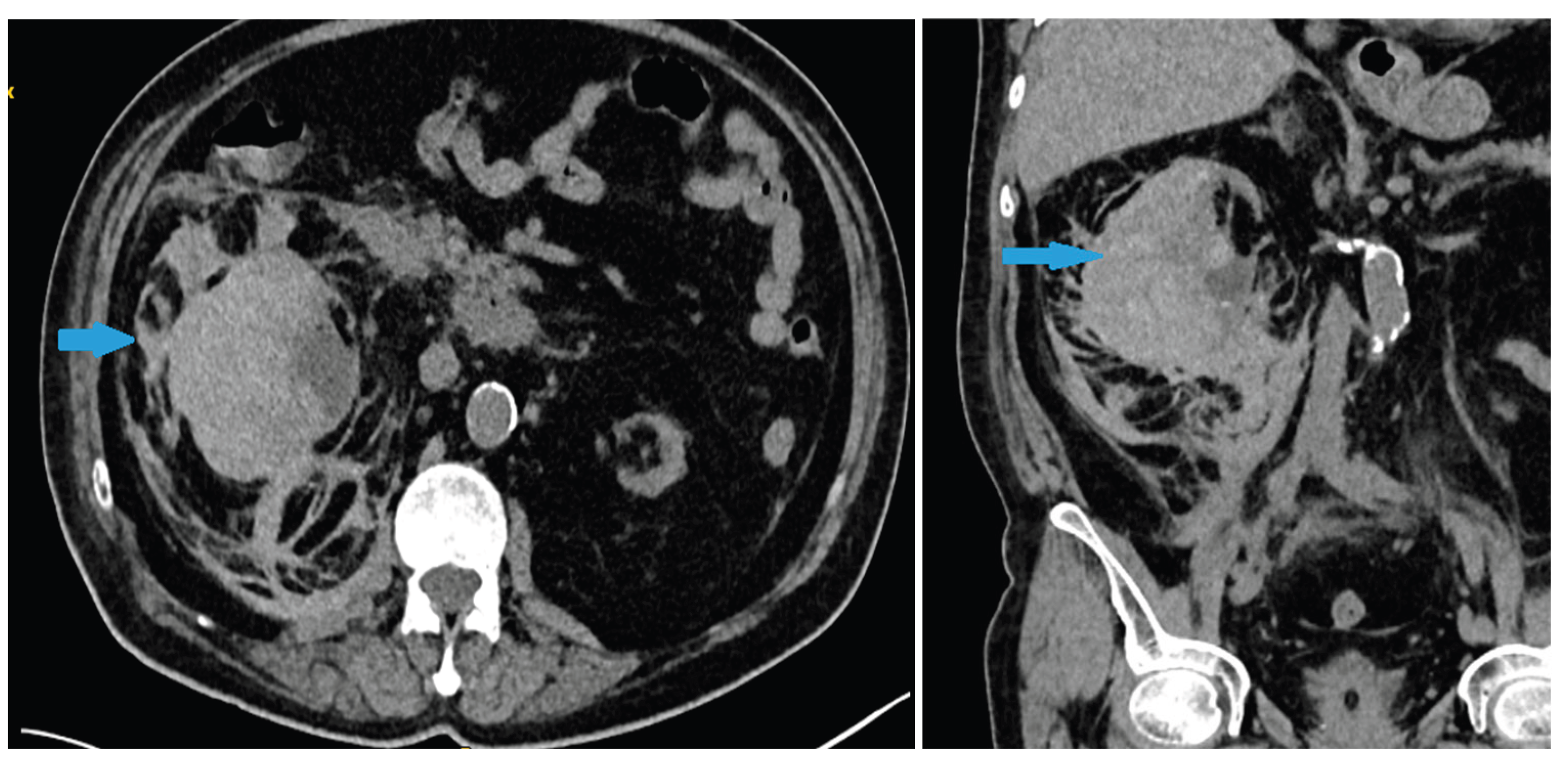

2. Case Presentation

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shah, J.N.; Gandhi, D.; Prasad, S.R.; Sandhu, P.K.; Banker, H.; Molina, R.; Khan, M.S.; Garg, T.; Katabathina, V.S. Wunderlich Syndrome: Comprehensive Review of Diagnosis and Management. Radiographics 2023, 43, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonolini, M.; Ierardi, A.M.; Carrafiello, G. Letter to the Editor: Spontaneous Renal Haemorrhage in End-Stage Renal Disease. Insights Imaging 2015, 6, 693–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynch, E.; Gaines, J.; James, J.; Aro, T.; Hoenig, D.; Okeke, Z.; et al. Informing an Approach to the Subcapsular Renal Hematoma (SRH): A Ten-Year Review of the Natural History and Progression of SRH. J. Urol. 2023, 209 (Suppl. 4), e111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, S.; Steinberg, P.; Denker, B.; et al. Spontaneous Renal Hemorrhage: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Res. Sq. 2022, Preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquez, M.M.A.; Lim, A.S.; Guiritan, A.T.R. Wunderlich Syndrome in a Patient with ESKD Diagnosed with COVID-19: A Case Report: TH-PO1150. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2024, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocak, G.; Rookmaaker, M.B.; Algra, A.; de Borst, G.J.; Doevendans, P.A.; Kappelle, L.J.; Verhaar, M.C.; Visseren, F.L.; van der Graaf, Y.; Grobbee, D.E.; et al. Chronic Kidney Disease and Bleeding Risk in Patients at High Cardiovascular Risk: A Cohort Study. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2018, 16, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunns, G.R.; Moore, E.E.; Chapman, M.P.; Moore, H.B.; Stettler, G.R.; Peltz, E.; Burlew, C.C.; Silliman, C.C.; Banerjee, A.; Sauaia, A. The Hypercoagulability Paradox of Chronic Kidney Disease: The Role of Fibrinogen. Am. J. Surg. 2017, 214, 1215–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.Y.; Oak, C.Y.; Kim, M.J.; Kim, C.S.; Choi, J.S.; Bae, E.H.; et al. Prevalence and Associations for Abnormal Bleeding Times in Patients with Renal Insufficiency. Platelets 2013, 24, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malek-Marín, T.; Arenas, D.; Gil, T.; Moledous, A.; Okubo, M.; Arenas, J.J.; Morales, A.; Cotilla, E. Spontaneous Retroperitoneal Hemorrhage in Dialysis: A Presentation of 5 Cases and Review of the Literature. Clin. Nephrol. 2010, 74, 229–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawahara, T.; Kawahara, K.; Ito, H.; Yamaguchi, S.; Mitsuhashi, H.; Makiyama, K.; Uemura, H.; Sakai, M.; Kubota, Y. Spontaneous Renal Hemorrhage in Hemodialysis Patients. Case Rep. Nephrol. Urol. 2011, 1, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Abidi, H.; Ibrahimi, A.; El Aboudi, A.; Mikou, M.A.; Boualaoui, I.; Labbi, Z.; El Aoufir, O.; Fikri, M.; El Sayegh, H.; Nouini, Y. Management of Spontaneous Subscapular Renal Hemorrhage: A Multidisciplinary and Hybrid Approach to Wunderlich Syndrome. Radiol. Case Rep. 2025, 20, 3106–3110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fouda, D.; Lionel, F.; Elimby, E.; Dongmo, N.; Bitoungui, A.; Te, V.; Ngouadjeu. Evaluation of Bleeding Risk by Hemostatic Parameters in Hemodialysis at the Douala General Hospital. Open J. Nephrol. 2023, 13, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-K.; Ha, S.; Lee, J.W. Bilateral Spontaneous Perirenal Haemorrhage in a Patient on Haemodialysis. NDT Plus. 2009, 2, 412–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baishya, R.K.; Dhawan, D.R.; Sabnis, R.B.; Desai, M.R. Spontaneous Subcapsular Renal Hematoma: A Case Report and Review of Literature. Urol. Ann. 2011, 3, 44–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).