Submitted:

30 May 2025

Posted:

04 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Clinical Follow-Up

2.2. Ethics

2.3. Human Genome Microarray Assay for In-Vitro Treated Fibroblasts and Monocytes with Collagen-PVP

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

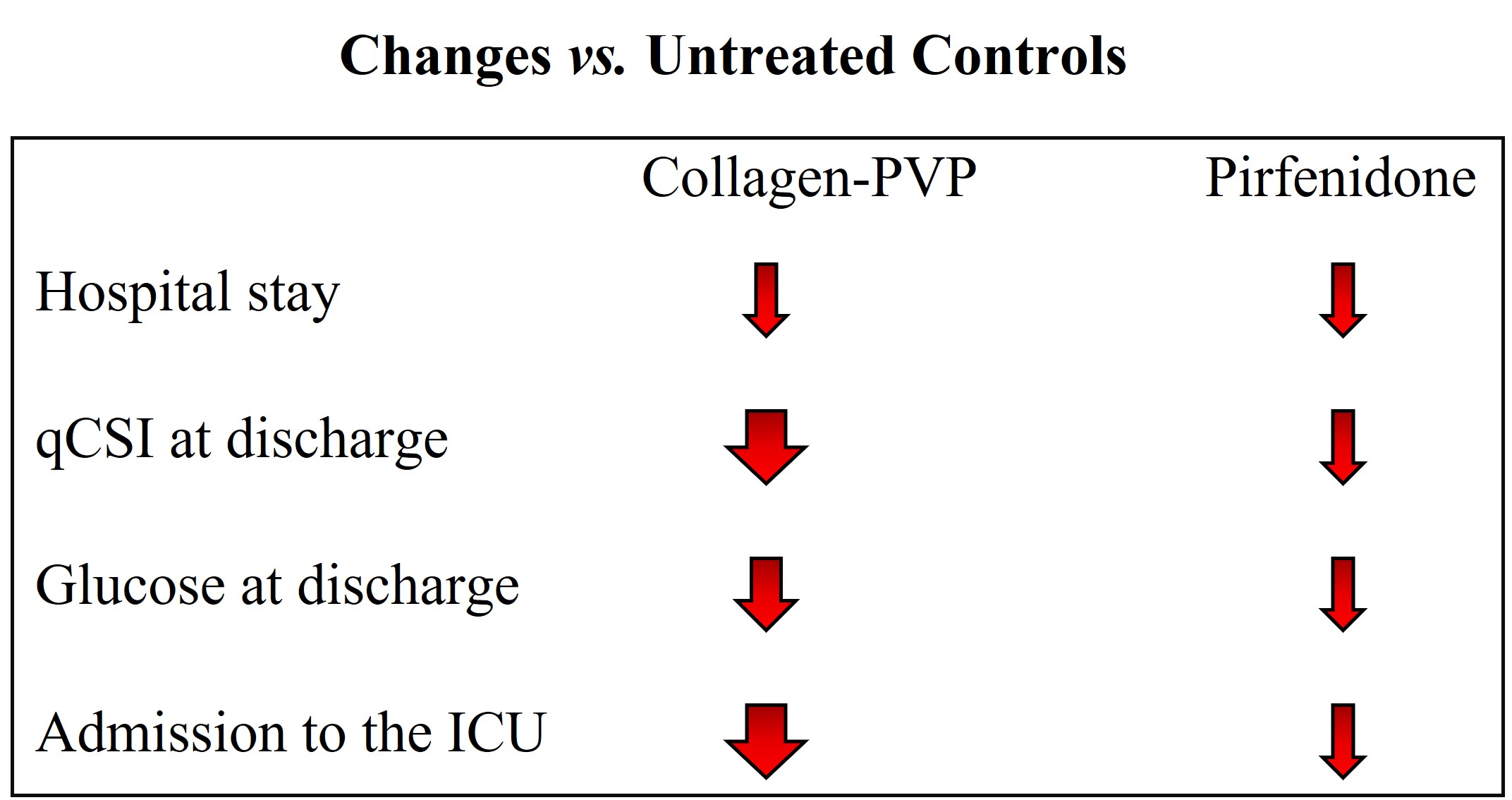

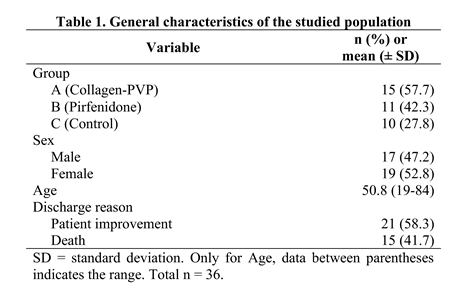

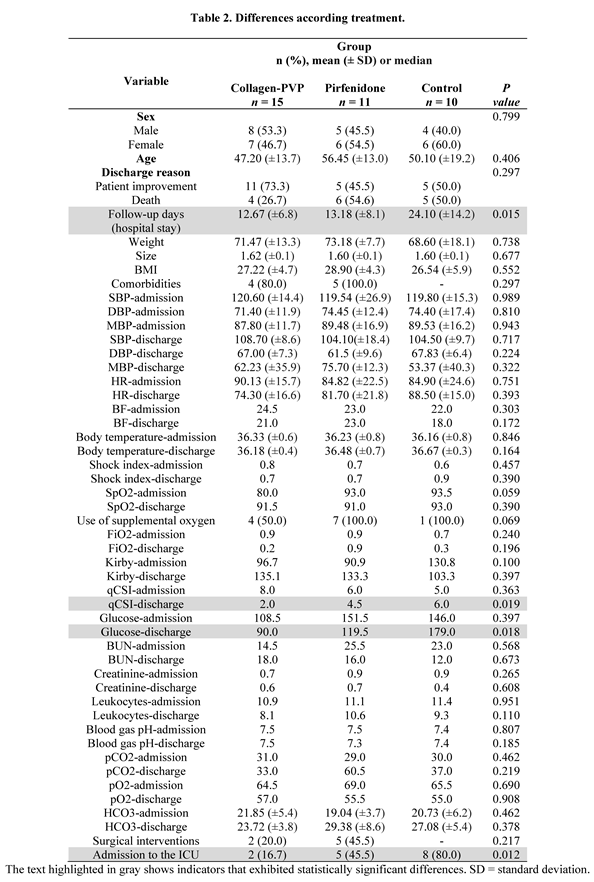

3.1. Treatment of Patients with COVID-19 with Collagen-PVP or Pirfenidone Improves Some of the Disease Indicators

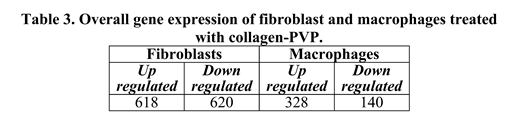

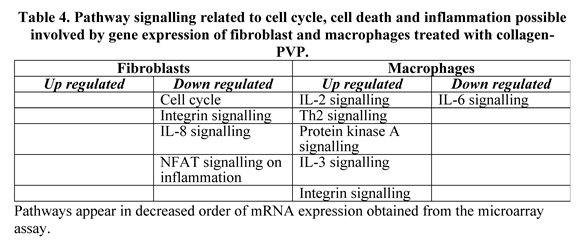

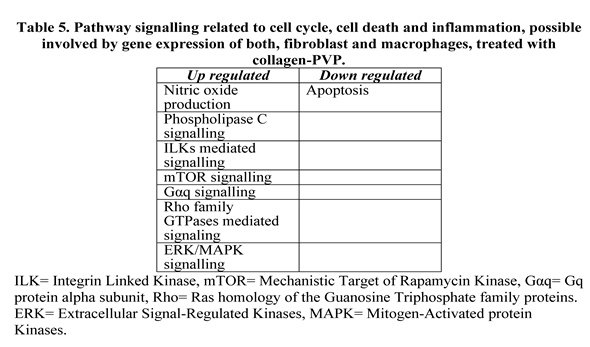

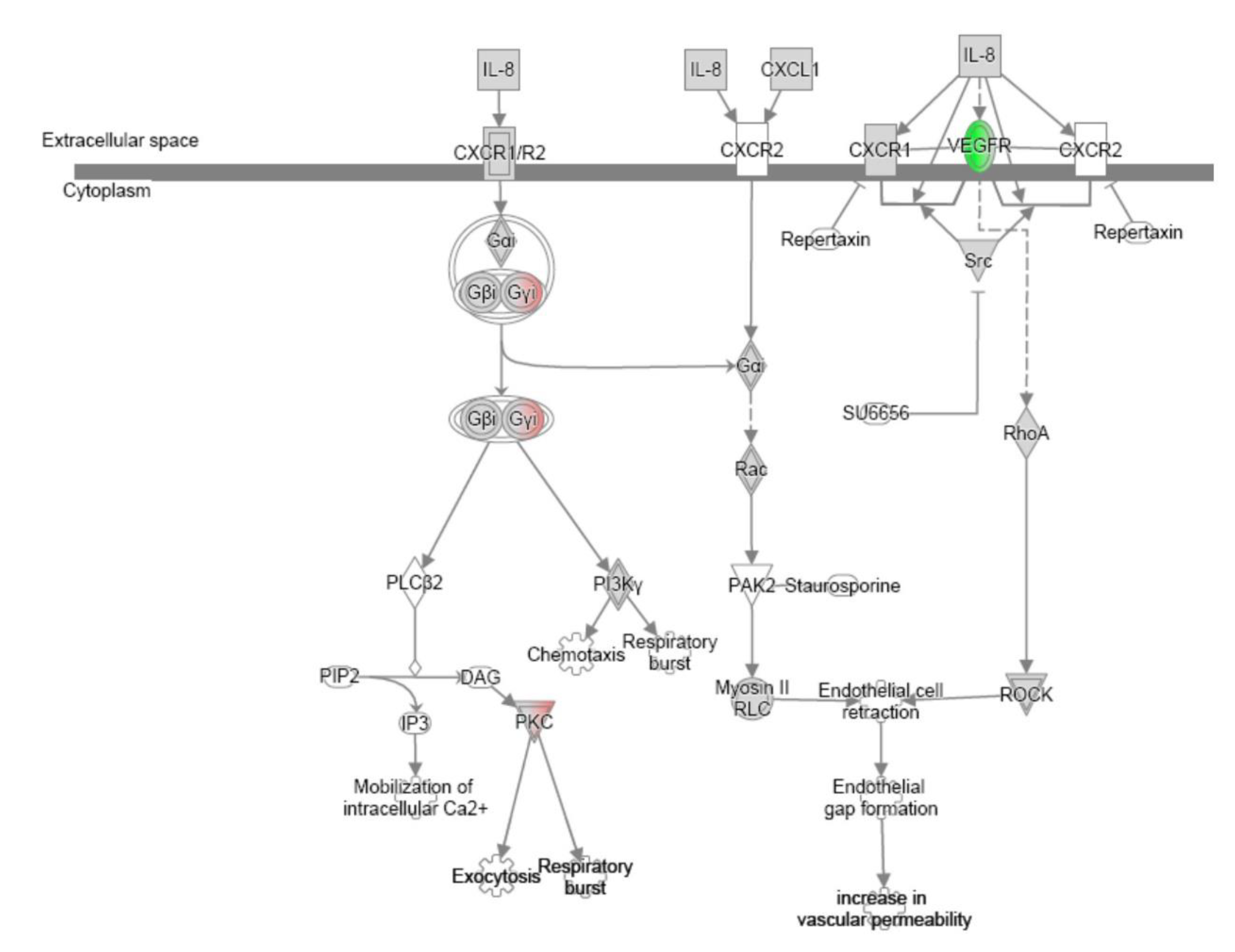

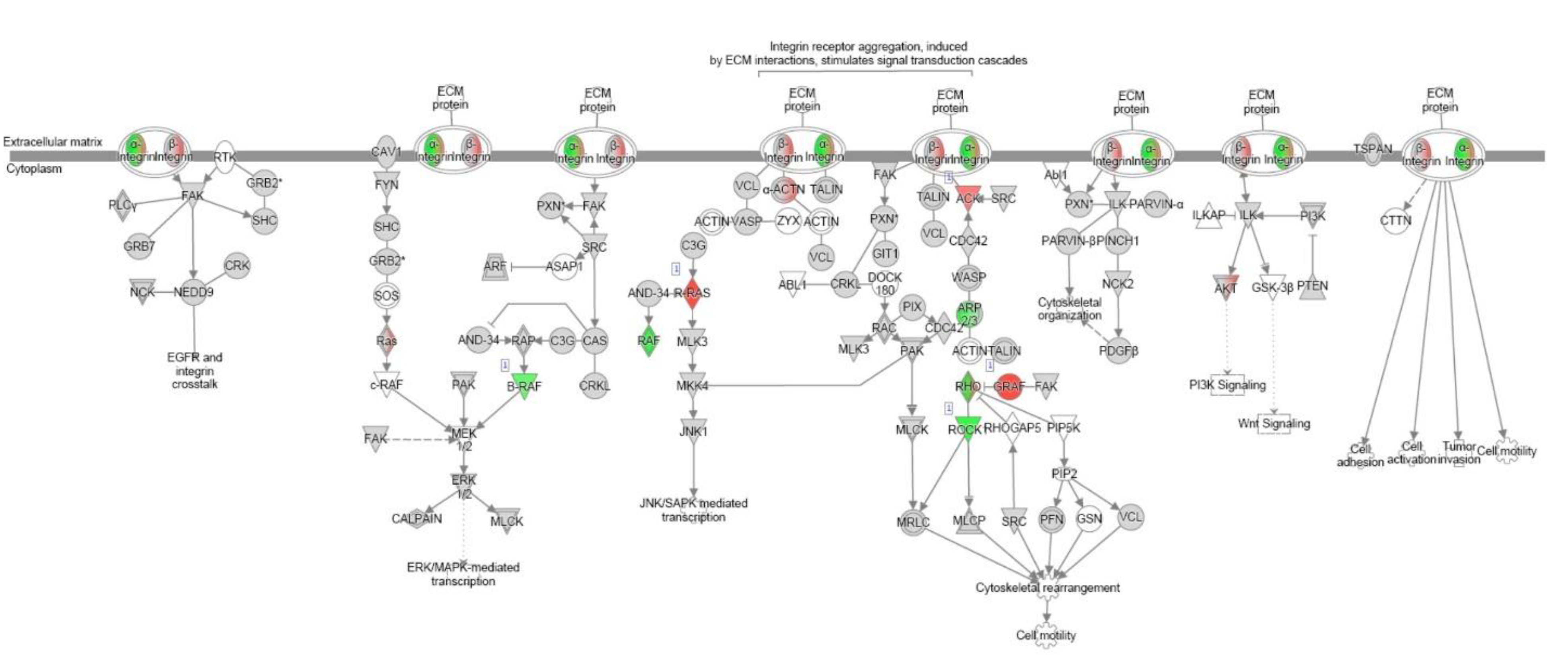

3.2. Human Genome Microarray Assay for In-Vitro Treated Fibroblasts and Monocytes with Collagen-PVP.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Collagen-PVP | Collagen-polyvinylpyrrolidone |

| ICU | Intensive care unit |

| qCSI | quick COVID-19 severity index |

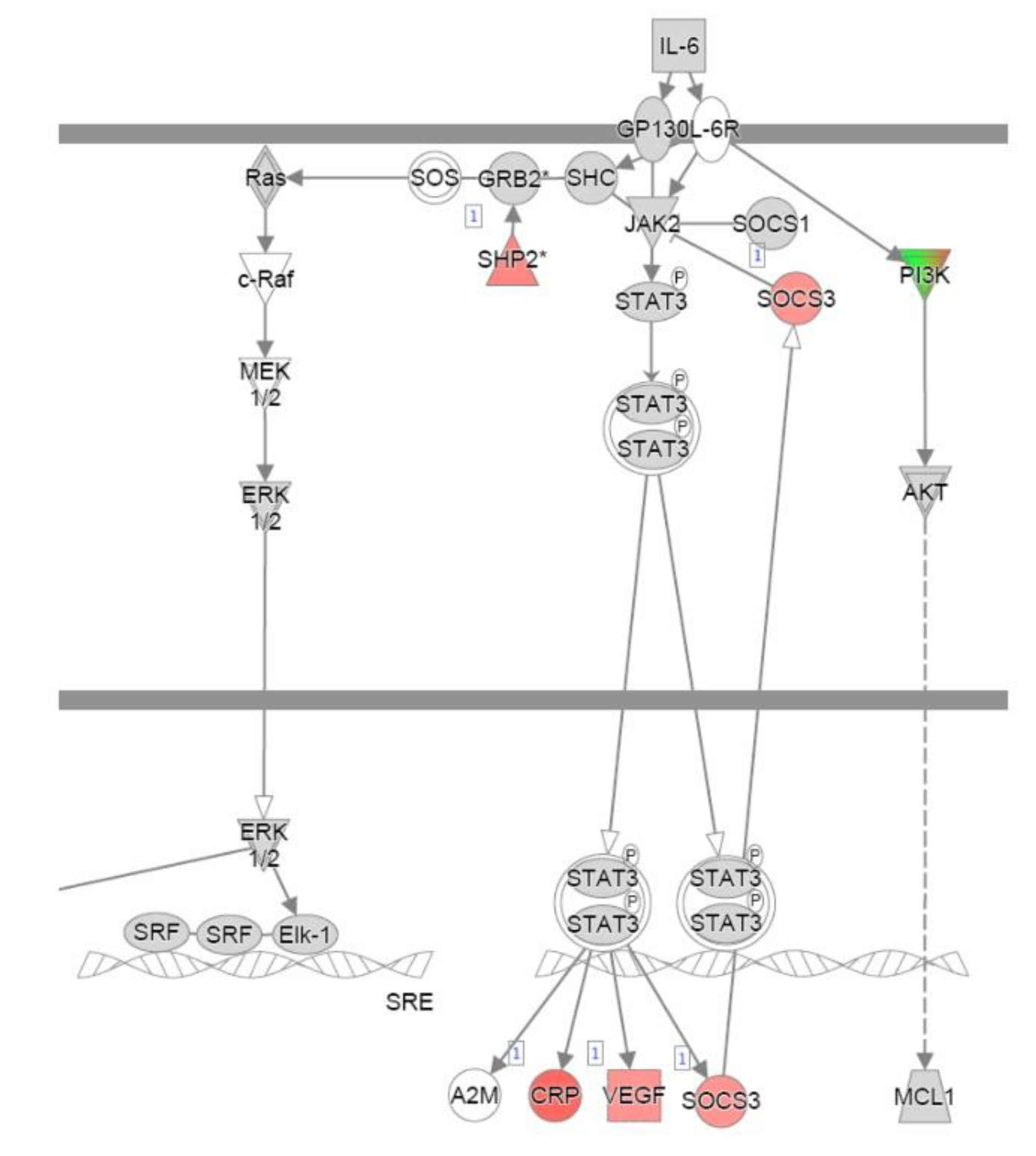

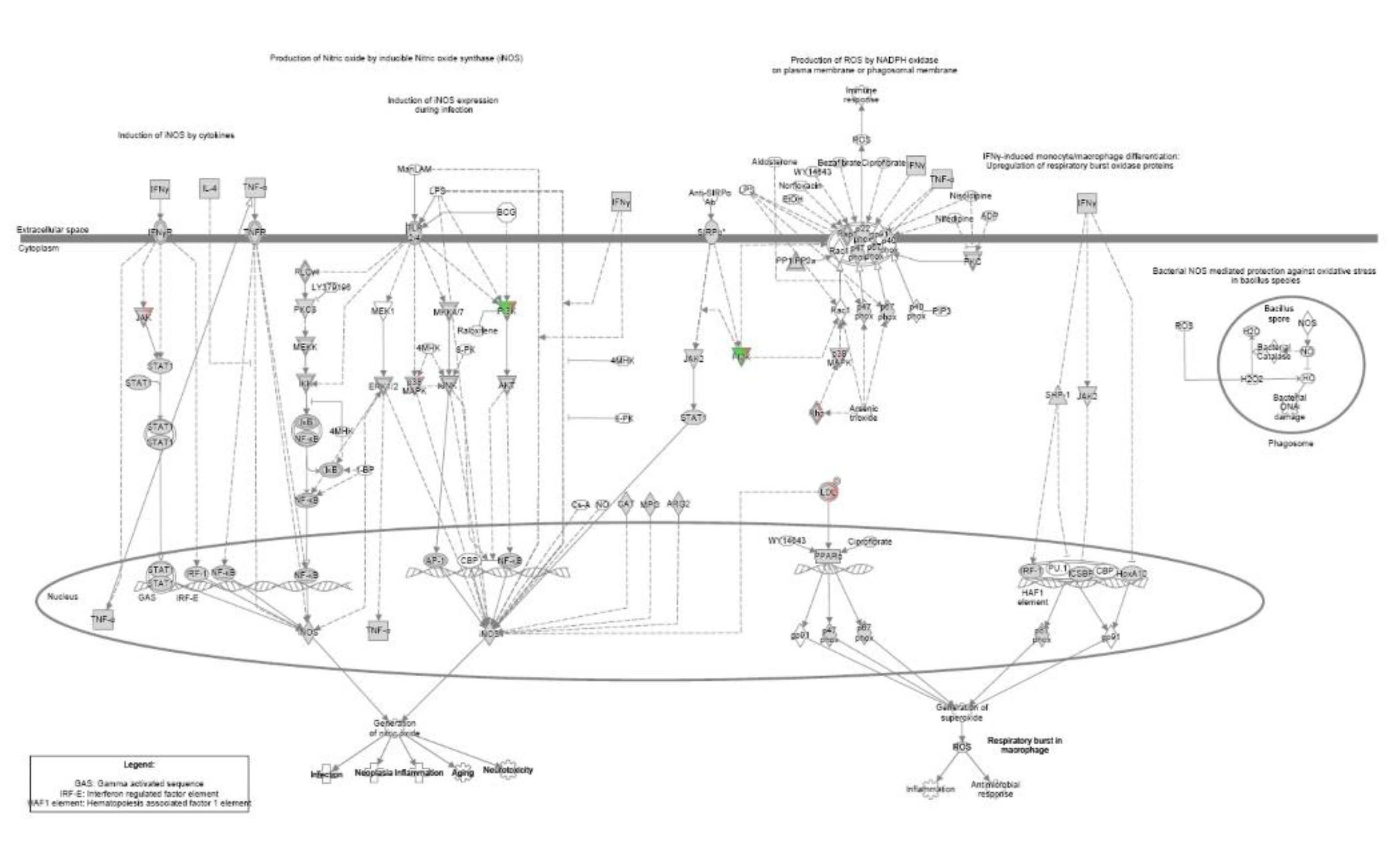

| JAK | Janus kinase |

| STAT | signal transducers and activators of transcription |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| ILK | Integrin Linked Kinase |

| mTOR | Mechanistic Target of Rapamycin Kinase |

| Gαq | Gq protein alpha subunit |

| Rho | Ras homology of the Guanosine Triphosphate family proteins |

| ERK | Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinases |

| MAPK | Mitogen-Activated protein Kinases |

Appendix A

References

- Kinross P, Suetens C, Dias JG, Alexakis L, Wijermans A, Colzani E, et al. Rapidly increasing cumulative incidence of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in the European Union/European Economic Area and the United Kingdom, 1 January to . Euro Surveill. 2020;25(11):2000285. 15 March. [CrossRef]

- The novel Chinese coronavirus (2019nCoV) infections: Challenges for fighting the storm. Eur J Clin Invest [Internet]. 2020 Mar [cited 2020 Mar 20];50(3). Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/eci.13209.

- Rothan HA, Byrareddy SN. The epidemiology and pathogenesis of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. J Autoimmun. 2020;109:102433. [CrossRef]

- Pang J, Wang MX, Ang IYH, Tan SHX, Lewis RF, Chen JI, et al. Potential Rapid Diagnostics, Vaccine and Therapeutics for 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV): A Systematic Review. J Clin Med. 2020;9(3):623. [CrossRef]

- Ng Y, Li Z, Chua YX, Chaw WL, Zhao Z, Er B, et al. Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Surveillance and Containment Measures for the First 100 Patients with COVID-19 in Singapore - -February 29, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(11):307-311. 2 January. [CrossRef]

- Applegate WB, Ouslander JG. COVID-19 Presents High Risk to Older Persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(4):681. [CrossRef]

- Liang H, Acharya G. Novel corona virus disease (COVID-19) in pregnancy: What clinical recommendations to follow? Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2020;99(4):439-442. [CrossRef]

- Sevillano Pires L, Andrino B, Llaneras K, Grasso D. El mapa del coronavirus: así crecen los casos día a día y país por país. 2020 Mar 19; Available from: https://elpais.com/sociedad/2020/03/16/actualidad/1584360628_538486.html.

- Sette A, Crotty S. Adaptive immunity to SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Cell. 2021 Feb 18;184(4):861-880. [CrossRef]

- Ye Q, Wang B, Mao J. The pathogenesis and treatment of the `Cytokine Storm' in COVID-19. J Infect. 2020;80(6):607-613. [CrossRef]

- Flaumenhaft R, Enjyoji K, Schmaier AA. Vasculopathy in COVID-19. Blood. 2022;140(3):222-235. [CrossRef]

- Yalcin AD, Yalcin AN. Future perspective: biologic agents in patients with severe COVID-19. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 2021;43(1):1-7. [CrossRef]

- Tale S, Ghosh S, Meitei SP, Kolli M, Garbhapu AK, Pudi S. Post-COVID-19 pneumonia pulmonary fibrosis. QJM. 2020;113(11):837-838. [CrossRef]

- Vasarmidi E, Tsitoura E, Spandidos DA, Tzanakis N, Antoniou KM. Pulmonary fibrosis in the aftermath of the COVID-19 era (Review). Exp Ther Med. 2020;20(3):2557-2560. [CrossRef]

- Soy M, Keser G, Atagündüz P, Tabak F, Atagündüz I, Kayhan S. Cytokine storm in COVID-19: pathogenesis and overview of anti-inflammatory agents used in treatment. Clin Rheumatol. 2020;39(7):2085-2094. [CrossRef]

- George PM, Wells AU, Jenkins RG. Pulmonary fibrosis and COVID-19: the potential role for antifibrotic therapy. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(8):807-815. [CrossRef]

- Krötzsch-Gómez FE, Furuzawa-Carballeda J, Reyes-Márquez R, Quiróz-Hernández E, Díaz de León L. Cytokine expression is downregulated by collagen-polyvinylpyrrolidone in hypertrophic scars. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;111(5):828-834. [CrossRef]

- Furuzawa-Carballeda J, Krötzsch E, Barile-Fabris L, Alcalá M, Espinosa-Morales R. Subcutaneous administration of collagen-polyvinylpyrrolidone down regulates IL-1beta, TNF-alpha, TGF-beta1, ELAM-1 and VCAM-1 expression in scleroderma skin lesions. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30(1):83-86. [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi H, Ebina M, Kondoh Y, Ogura T, Azuma A, Suga M, et al. Pirfenidone in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir J. 2010;35(4):821-829. [CrossRef]

- Leyva-Gómez G, Lima E, Krötzsch G, Pacheco-Marín R, Rodríguez-Fuentes N, Quintanar-Guerrero D, et al. Physicochemical and functional characterization of the collagen-polyvinylpyrrolidone copolymer. J Phys Chem B. 2014;118(31):9272-9283. [CrossRef]

- Furuzawa-Carballeda J, Rodríquez-Calderón R, Díaz de León L, Alcocer-Varela J. Mediators of inflammation are down-regulated while apoptosis is up-regulated in rheumatoid arthritis synovial tissue by polymerized collagen. Clin Exp Immunol. 2002;130(1):140-149. [CrossRef]

- Krämer A, Green J, Pollard J, Tugendreich S. Causal analysis approaches in Ingenuity Pathway Analysis. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(4):523-530. [CrossRef]

- Goker Bagca B, Biray Avci C. The potential inhibition of the JAK/STAT pathway by ruxolitinib in the treatment of COVID-19. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2020;54:51-62. [CrossRef]

- Al-Kuraishy HM, Batiha GE, Faidah H, Al-Gareeb AI, Saad HM, Simal-Gandara J. Pirfenidone and post-Covid-19 pulmonary fibrosis: invoked again for realistic goals. Inflammopharmacology. 2022;30(6):2017-2026. [CrossRef]

- Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y, Xia J, Zhou X, Xu S, et al. Risk Factors Associated With Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome and Death in Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(7):934. [CrossRef]

- Fadel R, Morrison AR, Vahia A, Smith ZR, Chaudhry Z, Bhargava P, et al. Early Short-Course Corticosteroids in Hospitalized Patients With COVID-19. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 Nov 19;71(16):2114–20. [CrossRef]

- Mehta P, Cron RQ, Hartwell J, Manson JJ, Tattersall RS. Silencing the cytokine storm: the use of intravenous anakinra in haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis or macrophage activation syndrome. Lancet Rheumatol. 2020;2(6):e358–67. [CrossRef]

- Geng J, Wang F, Huang Z, Chen X, Wang Y. Perspectives on anti-IL-1 inhibitors as potential therapeutic interventions for severe COVID-19. Cytokine. 2021;143:155544. [CrossRef]

- Xu X, Han M, Li T, Sun W, Wang D, Fu B, et al. Effective treatment of severe COVID-19 patients with tocilizumab. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2020;117(20):10970–5. [CrossRef]

- on behalf of the Gemelli-ICU Study Group, Montini L, De Pascale G, Bello G, Grieco DL, Grasselli G, et al. Compassionate use of anti-IL6 receptor antibodies in critically ill patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome due to SARS-CoV-2. Minerva Anestesiol [Internet]. 2021 Oct [cited 2021 Nov 25];87(10). Available from: https://www.minervamedica.it/index2.php?show=R02Y2021N10A1080.

- Ranieri VM, Pettilä V, Karvonen MK, Jalkanen J, Nightingale P, Brealey D, et al. Effect of Intravenous Interferon β-1a on Death and Days Free From Mechanical Ventilation Among Patients With Moderate to Severe Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2020;323(8):725.

- Callejas Rubio JL, Aomar Millán I, Moreno Higueras M, Muñoz Medina L, López López M, Ceballos Torres Á. Tratamiento y evolución del síndrome de tormenta de citoquinas asociados a infección por SARS-CoV-2 en pacientes octogenarios. Rev Esp Geriatría Gerontol. 2020;55(5):286–8.

- Hu B, Huang S, Yin L. The cytokine storm and COVID-19. J Med Virol. 2021;93(1):250-6.

- Gonzales-Zamora JA, Quiroz T, Vega AD. Successful treatment with Remdesivir and corticosteroids in a patient with COVID-19-associated pneumonia: A case report. Tratamiento exitoso con Remdesivir y corticoides en un paciente con neumonía asociada a COVID-19: reporte de un caso. Medwave. 2020;20(7):e7998. [CrossRef]

- Aygün İ, Kaya M, Alhajj R. Identifying side effects of commonly used drugs in the treatment of Covid 19. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):21508. [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Flores S, Priego-Ranero Á, Azamar-Llamas D, Olvera-Prado H, Rivas-Redonda KI, Ochoa-Hein E, et al. Effect of polymerised type I collagen on hyperinflammation of adult outpatients with symptomatic COVID-19. Clin Transl Med. 2022;12(3):e763. [CrossRef]

- Carpio-Orantes LD, García-Méndez S, Sánchez-Díaz JS, Aguilar-Silva A, Contreras-Sánchez ER, Hernández SNH. Use of Fibroquel® (Polymerized type I collagen) in patients with hypoxemic inflammatory pneumonia secondary to COVID-19 in Veracruz, Mexico. J Anesth Crit Care Open Access. 2021;13(1):69‒73. [CrossRef]

- Acat M, Yildiz Gulhan P, Oner S, Turan MK. Comparison of pirfenidone and corticosteroid treatments at the COVID-19 pneumonia with the guide of artificial intelligence supported thoracic computed tomography. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75(12):e14961. [CrossRef]

- Seifirad, S. Pirfenidone: A novel hypothetical treatment for COVID-19. Med Hypotheses. 2020;144:110005. [CrossRef]

- Rizvi AA, Kathuria A, Al Mahmeed W, Al-Rasadi K, Al-Alawi K, Banach M, et al. Post-COVID syndrome, inflammation, and diabetes. J Diabetes Complica-tions. 2022;36(11):108336. [CrossRef]

- Ye Q, Wang B, Mao J. The pathogenesis and treatment of the `Cytokine Storm' in COVID-19. J Infect. 2020;80(6):607-613. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y, Wang J, Liu C, Su L, Zhang D, Fan J, et al. IP-10 and MCP-1 as biomarkers associated with the severity of the disease of COVID-19. Mol Med. 2020;26(1):97. [CrossRef]

- Ghazavi A, Ganji A, Keshavarzian N, Rabiemajd S, Mosayebi G. Cytokine profile and disease severity in patients with COVID-19. Cytokine. 2021;137:155323. [CrossRef]

- Cao ZJ, Liu Y, Zhang Z, Yang PR, Li ZG, Song MY, et al. Pirfenidone ameliorates silica-induced lung inflammation and fibrosis in mice by inhibiting the secretion of interleukin-17A. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2022;43(4):908-918. [CrossRef]

- Finnerty JP, Ponnuswamy A, Dutta P, Abdelaziz A, Kamil H. Efficacy of antifibrotic drugs, nintedanib and pirfenidone, in treatment of progressive pulmonary fibrosis in both idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) and non-IPF: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pulm Med. 2021;21(1):411. [CrossRef]

- Chen Z, Zhou H, Huang X, Wang S, Ouyang X, Wang Y, et al. Pirfenidone attenuates cardiac hypertrophy against isoproterenol by inhibiting activation of the janus tyrosine kinase-2/signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (JAK-2/STAT3) signaling pathway. Bioengineered. 2022;13(5):12772-12782. [CrossRef]

- Borja-Flores A, Macías-Hernández SI, Hernández-Molina G, Perez-Ortiz A, Reyes-Martínez E, Belzazar-Castillo de la Torre J, et al. Long-Term Effectiveness of Polymerized-Type I Collagen Intra-Articular Injections in Patients with Symptomatic Knee Osteoarthritis: Clinical and Radiographic Evaluation in a Cohort Study. Adv Orthop. 2020;2020:9398274. [CrossRef]

- Furuzawa-Carballeda J, Cabral AR, Zapata-Zuñiga M, Alcocer-Varela J. Subcutaneous administration of polymerized-type I collagen for the treatment of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. An open-label pilot trial. J Rheumatol. 2003;30(2):256-259.

- Olivares-Martínez E, Hernández-Ramírez DF, Núñez-Álvarez CA, Meza-Sánchez DE, Chapa M, Méndez-Flores S, et al. Polymerized Type I Collagen Downregulates STAT-1 Phosphorylation Through Engagement with LAIR-1 in Circulating Monocytes, Avoiding Long COVID. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26(3):1018. [CrossRef]

- Sarode AY, Jha MK, Zutshi S, Ghosh SK, Mahor H, Sarma U, Saha B. Residue-Specific Message Encoding in CD40-Ligand. iScience. 2020 Aug 6;23(9):101441. [CrossRef]

- Olmos-Zuñiga JR, Silva-Martínez M, Jasso-Victoria R, Baltazares-Lipp M, Hernández-Jiménez C, Buendía-Roldan I, et al. Effects of Pirfenidone and Collagen-Polyvinylpyrrolidone on Macroscopic and Microscopic Changes, TGF-β1 Expression, and Collagen Deposition in an Experimental Model of Tracheal Wound Healing. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:6471071. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).