Submitted:

28 May 2025

Posted:

29 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

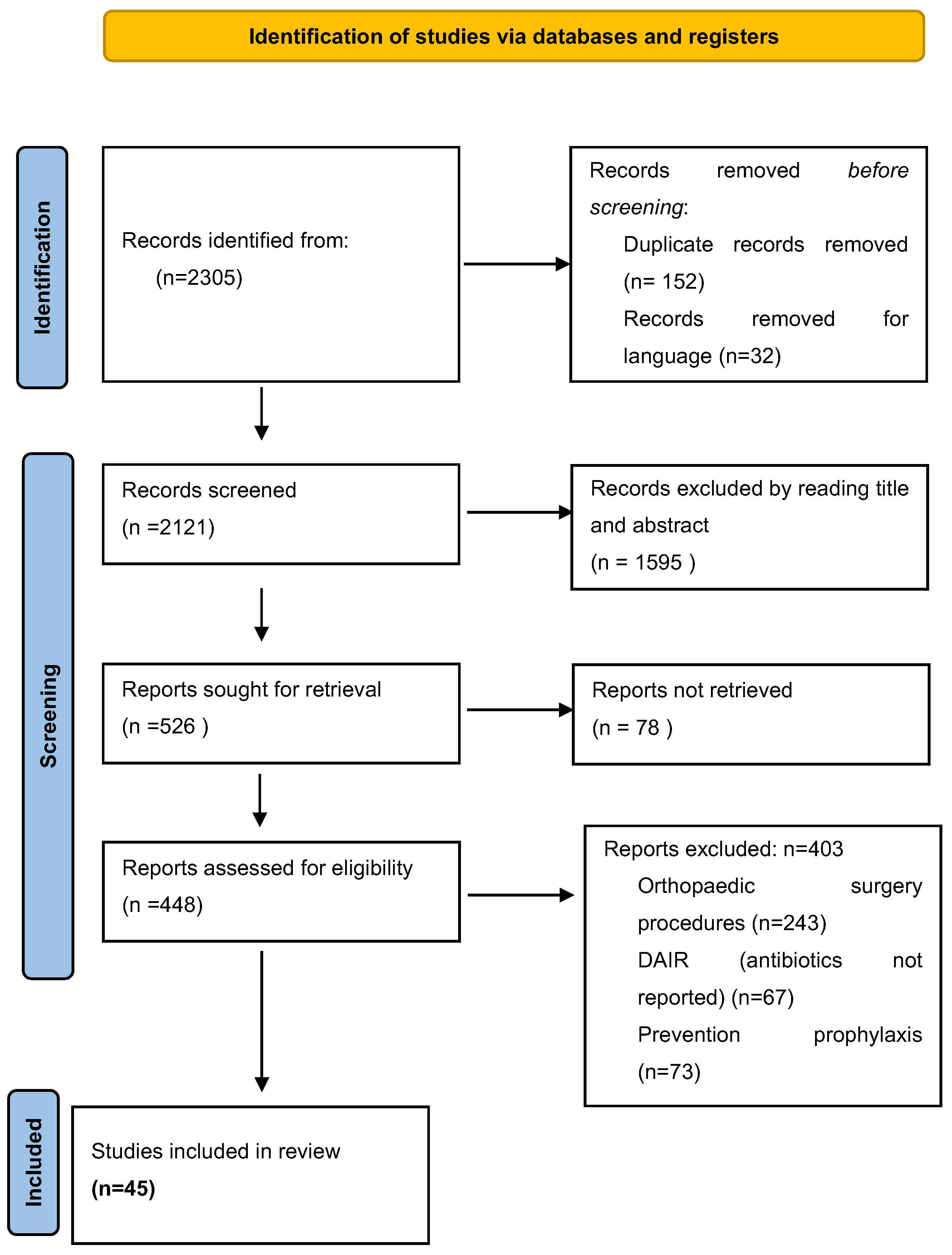

2.1. Literature Search Strategy

2.2. Selection Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction and Criteria Appraisal

3. Results

4. Definitions and Classifications

4.1. Defining Prosthetic Joint Infections and Clinical Presentation

4.2. Classification of Prosthetic Joint Infections

- T (Tissue & Implant) – Condition of the infected implant and periarticular soft tissues.

- N (Non-human Cell) – The causative microorganism.

- M (Morbidity of the Patient) – The host’s overall health and comorbidities.

5. Prosthetic Joint Infection Surgery Options

6. Antibiotic Duration of PJI According to the Surgery Options

6.1. Prosthetic Joint Infection Treated with DAIR

6.1.1. The Recommended Duration of Antibiotics

6.1.2. Comparative Studies to Shorten the Antibiotic Duration for PJI

Twelve Weeks Versus Eight Weeks

Twelve Weeks Versus Six Weeks

6.2. PJI Treated with Single-Step Exchange Procedure

6.3. PJI treated With Two-Step Exchange Procedure

6.4. PJI Treated with Total Removal Without Implantation

6.4.1. Permanent Resection Arthroplasty

6.4.3. Amputation

6.5. Discussion

7. The Role of Biofilms in PJI Treatment

8. Future Perspectives

9. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Patel, R. Periprosthetic Joint Infection. N Engl J Med 2023, 388, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaime Lora-Tamayo, Mikel Mancheno-Losa , María Ángeles Meléndez-Carmona , Pilar Hernández-Jiménez , Natividad Benito and Oscar Murillo. Appropriate Duration of Antimicrobial Treatment for Prosthetic Joint Infections: A Narrative Review. Antibiotics 2024, 13(4), 293. [CrossRef]

- Zimmerli, W.; Trampuz, A.; Ochsner, P.E. Prosthetic-Joint Infections. New England Journal of Medicine 2004, 351, 1645–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osmon, D.R.; Berbari, E.F.; Berendt, A.R.; Lew, D.; Zimmerli, W.; Steckelberg, J.M.; Rao, N.; Hanssen, A.; Wilson, W.R. Diagnosis and Management of Prosthetic Joint Infection: Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA). Clinical Infectious Diseases 2013, 56, e1–e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parvizi J, Tan TL, Goswami K, et al. The 2018 definition of periprosthetic hip and knee infection: an evidence-based and validated criteria. J Arthroplasty. 2018, 33, 1309–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argenson, J.N.; Arndt, M.; Babis, G.; Battenberg, A.; Budhiparama, N.; Catani, F.; Chen, F.; de Beaubien, B.; Ebied, A.; Esposito, S.; et al. Hip and Knee Section, Treatment, Debridement and Retention of Implant: Proceedings of International Consensus on Orthopedic Infections. J. Arthroplast. 2019, 34, S399–S419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: Explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009, 339, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvizi, J.; Zmistowski, B.; Berbari, E.F.; Bauer, T.W.; Springer, B.D.; Della Valle, C.J.; Garvin, K.L.; Mont, M.A.; Wongworawat, M.D.; Zalavras, C.G. New Definition for Periprosthetic Joint Infection: From the Workgroup of the Musculoskeletal Infection Society. Clinical Orthopaedics & Related Research 2011, 469, 2992–2994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvizi, J.; Gehrke, T. Definition of Periprosthetic Joint Infection. The Journal of Arthroplasty 2014, 29, 1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Urena, E.O.; Tande, A.J.; Osmon, D.R.; Berbari, E.F. Diagnosis of Prosthetic Joint Infection. Infectious Disease Clinics of North America 2017, 31, 219–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coventry, M.B. Treatment of Infections Occurring in Total Hip Surgery. Orthop Clin North Am 1975, 6, 991–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukayama, D.T.; Estrada, R.; Gustilo, R.B. Infection after Total Hip Arthroplasty. A Study of the Treatment of One Hundred and Six Infections*: The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery 1996, 78, 512–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andre Lunz, Burkhard Lehner, Moritz N. Voss, Kevin Knappe, Sebastian Jaeger, Moritz M. Innmann, Tobias Renkawitz and Georg W. Omlor. Impact and Modification of the New PJI-TNM Classification for Periprosthetic Joint Infections. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arne Kienzle, Sandy Walter, Paul Kohli, Clemens Gwinner, Sebastian Hardt, Michael Muller, Carsten Perka, Stefanie Donner. Assessing the TNM Classification for Periprosthetic Joint Infections of the Knee: Predictive Validity for Functional and Subjective Outcomes. J. Pers. Med. 2025, 15, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabih, O. Darouiche, Treatment of Infections Associated with Surgical Implants. N Engl J Med 2004, 350, 1422–9. [Google Scholar]

- T. Gehrke, P. Alijanipour, J. Parvizi. The management of an infected total knee arthroplasty. Bone Joint J 2015, 97-B, 20–9.

- Ryan Miller, Carlos A. Higuera, Janet Wu, Pharm, Alison Klika, Maja Babic, Nicolas S. Piuzzi. Periprosthetic Joint Infection A Review of Antibiotic Treatment. JBJS REVIEWS 2020, 8, e19.00224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Don Bambino Geno Tai, Elie F. Berbari, Gina A. Suh, Brian D. Lahr, Matthew P. Abdel, and Aaron J Tande. Truth in DAIR: Duration of Therapy and the Use of Quinolone/Rifampin-Based Regimens After Debridement and Implant Retention for Periprosthetic Joint Infections. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2022 Jul 25;9, ofac363. [CrossRef]

- Li HK, Rombach I, Zambellas R, et al. Oral versus intravenous antibiotics for bone and joint infection. N Engl J Med. 2019, 380, 425–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Berdal J, Skramm I, Mowinckel P, Gulbrandsen P, Bjørnholt JV. Useof rifampicin and ciprofloxacin combination therapy after surgical debridement in the treatment of early manifestation prosthetic joint infections. Clin Microbiol Infect 2005, 11, 843–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano A, Garcıa S, Bori G et al. Treatment of acute post-surgical infection of joint arthroplasty. Clin Microbiol Infect 2006, 12, 930–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Pastor JC, Munoz-Mahamud E, Vilchez F et al. Outcome of acute prosthetic joint infections due to gram-negative bacilli treated with open debridement and retention of the prosthesis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2009, 53, 4772–4777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo J, Miguel LGS, Euba G et al. Early prosthetic joint infection: outcomes with debridement and implant retention followed by antibiotic therapy. Clin Microbiol Infect 2010, 17, 1632–1637. [Google Scholar]

- Vilchez F, Martı´nez-Pastor JC, Garcıa-Ramiro S et al. Outcome and predictors of treatment failure in early post-surgical prosthetic joint infections due to Staphylococcus aureus treated with debridement. Clin Microbiol Infect 2011, 17, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tornero, E.; Morata, L.; Martínez-Pastor, J.C.; Angulo, S.; Combalia, A.; Bori, G.; García-Ramiro, S.; Bosch, J.; Mensa, J.; Soriano, A. Importance of selection and duration of antibiotic regimen in prosthetic joint infections treated with debridement and implant retention. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2016, 71, 1395–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A.-P. Puhto, T. A.-P. Puhto, T. Puhto and H. Syrjala. Short-course antibiotics for prosthetic joint infections treated with prosthesis retention.

- Lora-Tamayo, J.; Murillo, O.; Iribarren, J.A.; Soriano, A.; Sánchez-Somolinos, M.; Baraia-Etxaburu, J.M.; Rico, A.; Palomino, J.; Rodríguez-Pardo, D.; Horcajada, J.P.; et al. A large multicenter study of methicillin-susceptible and methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus prosthetic joint infections managed with implant retention. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013, 56, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lora-Tamayo, J.; Euba, G.; Cobo, J.; Horcajada, J.P.; Soriano, A.; Sandoval, E.; Pigrau, C.; Benito, N.; Falgueras, L.; Palomino, J.; et al. Short- versus long-duration levofloxacin plus rifampicin for acute staphylococcal prosthetic joint infection managed with implant retention: A randomised clinical trial. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2016, 48, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Systematic Literature Review on the Management of Surgical Site Infections. Report No.: 9 June 2018. Available online: https://www.aaos.org/globalassets/quality-and-practice-resources/surgical-siteinfections/ssi-sr_8-29-19.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2024).

- Bernard, L.; Legout, L.; Zürcher-Pfund, L.; Stern, R.; Rohner, P.; Peter, R.; Assal, M.; Lew, D.; Hoffmeyer, P.; Six, I.U. Six weeks of antibiotic treatment is sufficient following surgery for septic arthroplasty. J. Infect. 2010, 61, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaussade, H.; Uçkay, I.; Vuagnat, A.; Druon, J.; Gras, G.; Rosset, P.; Lipsky, B.A.; Bernard, L. Antibiotic therapy duration for prosthetic joint infections treated by Debridement and Implant Retention (DAIR): Similar long-term remission for 6 weeks as compared to 12 weeks. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 63, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, L.; Arvieux, C.; Brunschweiler, B.; Touchais, S.; Ansart, S.; Bru, J.-P.; Oziol, E.; Boeri, C.; Gras, G.; Druon, J.; et al. Antibiotic Therapy for 6 or 12 Weeks for Prosthetic Joint Infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 1991–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaled, M. Yaghmour, Emanuele Chisari and Wasim S. Khan. Single-Stage Revision Surgery in Infected Total Knee Arthroplasty: A PRISMA Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowan, F.E.; Donaldson, M.J.; Pietrzak, J.R.; Haddad, F.S. The Role of One-Stage Exchange for Prosthetic Joint Infection. Curr. Rev. Musculoskelet. Med. 2018, 11, 370–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, F.S.; Sukeik, M.; Alazzawi, S. Is Single-stage Revision According to a Strict Protocol Effective in Treatment of Chronic Knee Arthroplasty Infections? Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2015, 473, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Castellani, L.; Daneman, N.; Mubareka, S.; Jenkinson, R. Factors Associated with Choice and Success of OneVersus Two-Stage Revision Arthroplasty for Infected Hip and Knee Prostheses. HSS J. 2017, 13, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Ni, M.; Li, X.X.; Zhang, Q.; Li, X.X.; Chen, J. Two-stage revisions for culture-negative infected total knee arthroplasties: A five-year outcome in comparison with one-stage and two-stage revisions for culture-positive cases. J. Orthop. Sci. 2017, 22, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenny, J.Y.; Barbe, B.; Gaudias, J.; Boeri, C.; Argenson, J.N. High infection control rate and function after routine one-stage exchange for chronically infected TKA. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2013, 471, 238–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cochran, A.R.; Ong, K.L.; Lau, E.; Mont, M.A.; Malkani, A.L. Risk of Reinfection After Treatment of Infected Total Knee Arthroplasty. J. Arthroplast. 2016, 31, 156–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massin, P.; Delory, T.; Lhotellier, L.; Pasquier, G.; Roche, O.; Cazenave, A.; Estellat, C.; Jenny, J.Y. Infection recurrence factors in one- and two-stage total knee prosthesis exchanges. Knee Surg. Sport Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2016, 24, 3131–3139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, J.; Merz, A.; Frommelt, L.; Fink, B. High rate of infection control with one-stage revision of septic knee prostheses excluding MRSA and MRSE. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2012, 470, 1461–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugasundaram, S.; Ricciardi, B.F.; Briggs, T.W.R.; Sussmann, P.S.; Bostrom, M.P. Evaluation and Management of Periprosthetic Joint Infection-an International, Multicenter Study. HSS J. 2014, 10, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenny, J.Y.; Barbe, B.; Cazenave, A.; Roche, O.; Massin, P. Patient selection does not improve the success rate of infected TKA one stage exchange. Knee 2016, 23, 1012–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setor, K. Kunutsor*, Michael R. Whitehouse, Ashley W. Blom, Andrew D. Beswick, INFORM Team. Patient-Related Risk Factors for Periprosthetic Joint Infection after Total Joint Arthroplasty: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLOS ONE |. [CrossRef]

- Tibrewal, S.; Malagelada, F.; Jeyaseelan, L.; Posch, F.; Scott, G. Single-stage revision for the infected total knee replacement: Results from a single centre. Bone Jt. J. 2014, 96, 759–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchholz HW, Elson RA, Engelbrecht E, Lodenkamper H, Rottger J, Siegel A. Management of deep infection of total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1981, 63-B, 342–353.

- Ammon P, Stockley I. Allograft bone in two-stage revision of the hip for infection. Is it safe? J Bone Joint Surg Br 2004, 86, 962–965. [Google Scholar]

- Stockley I, Mockford BJ, Hoad-Reddick A, Norman P. The use of two-stage exchange arthroplasty with depot antibiotics in the absence of long-term antibiotic therapy in infected total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2008, 90, 145–148. [Google Scholar]

- Kendoff D, Gehrke T. Surgical management of periprosthetic joint infection: one-stage exchange. J Knee Surg. 2014, 27, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whiteside, L.A.; Peppers, M.; Nayfeh, T.A.; Roy, M.E. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in TKA treated with revision and direct intra-articular antibiotic infusion. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2011, 469, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, P.; Petheram, T.G.; Kurtz, S.; Konttinen, Y.T.; Gregg, P.; Deehan, D. Patient reported outcome measures after revision of the infected TKR: Comparison of single versus two-stage revision. Knee Surg. Sport Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2013, 21, 2713–2720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Paula Leite Cury, R.; Cinagawa, E.H.T.; Camargo, O.P.A.; Honda, E.K.; Klautau, G.B.; Salles, M.J.C. Treatment of infection after total knee arthroplasty. Acta Ortopédica Bras. 2015, 23, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahar, A.; Kendoff, D.O.; Klatte, T.O.; Gehrke, T.A. Can Good Infection Control Be Obtained in One-stage Exchange of the Infected TKA to a Rotating Hinge Design? 10–year Results. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2016, 474, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raut VV, Siney PD, Wroblewski BM. One-stage revision of infected total hip replacements with discharging sinuses. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1994, 76, 721–724. [Google Scholar]

- Buttaro MA, Pusso R, Piccaluga F. Vancomycin-supplemented impacted bone allografts in infected hip arthroplasty. Two-stage revision results. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2005, 87, 314–319. [Google Scholar]

- Hoad-Reddick DA, Evans CR, Norman P, Stockley I. Is there a role for extended antibiotic therapy in a two-stage revision of the infected knee arthroplasty? J Bone Joint Surg Br 2005, 87, 171–174. [Google Scholar]

- Stockley I, Mockford BJ, Hoad-Reddick A, Norman P. The use of two-stage exchange arthroplasty with depot antibiotics in the absence of long-term antibiotic therapy in infected total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2008, 90, 145–148.

- Paul, B. McKenna · Keiran O’Shea · Eric L. Masterson.Two-stage revision of infected hip arthroplasty using a shortened post-operative course of antibiotics. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2009, 129, 489–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anagnostakos, K. Therapeutic use of antibiotic-loaded bone cement in the treatment of hip and knee joint infections. J Bone Joint Infect. 2017, 2, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benkabouche, M.; Racloz, G.; Spechbach, H.; Lipsky, B.A.; Gaspoz, J.M.; Uçkay, I. Four versus six weeks of antibiotic therapy for osteoarticular infections after implant removal: A randomized trial. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2019, 74, 2394–2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilker Uçkay, Kheeldass Jugun, Axel Gamulin, Joe Wagener, Pierre Hoffmeyer, Daniel Lew. Chronic Osteomyelitis. Curr Infect Dis Rep 2012, 14, 566–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falahee MH, Matthews LS, Kaufer H. Resection arthroplasty as a salvage procedure for a knee with infection after a total arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1987, 69-A, 1013–1021.

- Wasielewski RC, Barden RM, Rosenberg AG. Results of different surgical procedures on total knee arthroplasty infections. J Arthroplasty 1996, 11, 931–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taggart, T.; Kerry, R.M.; Norman, P.; Stockley, I. The use of vancomycin-impregnated cement beads in the management of infection of prosthetic joints. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Br. 2002, 84, 70–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, W.J.; Jones, R.S. Two-stage revision of infected total knee replacements using articulating cement spacers and short-term antibiotic therapy. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Ser. B 2006, 88, 1011–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, J.P.; Warren, R.E.; Jones, R.S.; Gregson, P.A. Is prolonged systemic antibiotic treatment essential in two-stage revision hip replacement for chronic Gram-positive infection? J. Bone Jt. Surg. Ser. B 2009, 91, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, Y.; Fehring, T.K.; Hanssen, A.; Marculescu, C.; Odum, S.M.; Osmon, D. Two-stage reimplantation for periprosthetic knee infection involving resistant organisms. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 2007, 89, 1227–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, P.H.; Huang, K.C.; Lee, P.C.; Lee, M.S. Two-stage revision of infected hip arthroplasty using an antibiotic-loaded spacer: Retrospective comparison between short-term and prolonged antibiotic therapy. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2009, 64, 392–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Helou, O.C.; Berbari, E.F.; Lahr, B.D.; Marculescu, C.E.; Razonable, R.R.; Steckelberg, J.M.; Hanssen, A.D.; Osmon, D.R. Management of prosthetic joint infection treated with two-stage exchange: The impact of antimicrobial therapy duration. Curr. Orthop. Pract. 2011, 22, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.H.; Chou, T.F.A.; Tsai, S.W.; Chen, C.F.; Wu, P.K.; Chen, C.M.; Wu, P.-K.; Chen, C.-M.; Chen, W.-M. Is short-course systemic antibiotic therapy using an antibiotic-loaded cement spacer safe after resection for infected total knee arthroplasty? A comparative study. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2020, 119, 1070–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mabry TM, Jacofsky DJ, Haidukewych GJ, et al. Comparison of intramedullary nailing and external fixation knee arthrodesis for the infected knee replacement. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2007, 464, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutscha-Lissberg F, Hebler U, Esenwein SA, et al. Fusion of the septic knee with external hybrid fixator. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2006, 14, 968–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spina M, Gualdrini G, Fosco M, et al. Knee arthrodesis with the Ilizarov external fixator as treatment for septic failure of knee arthroplasty. J Orthop Traumatol 2010, 11, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin Le Vavasseur, Valérie Zeller. Antibiotic Therapy for Prosthetic Joint Infections: An Overview. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wouter Rottier, Jessica Seidelman and Marjan Wouthuyzen-Bakker. Antimicrobial treatment of patients with a periprosthetic joint infection: basic principles. l. Arthroplasty 2023, 5, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maria Dudareva, Michelle Kümin, Werner Vach, Klaus Kaier, Jamie Ferguson, Martin McNally and Matthew Scarborough. Short or Long Antibiotic Regimes in Orthopaedics (SOLARIO): a randomised controlled open-label non-inferiority trial of duration of systemic antibiotics in adults with orthopaedic infection treated operatively with local antibiotic therapy. Trials 2019, 20, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costerton, J.W.; Stewart, P.S.; Greenberg, E.P. Bacterial Biofilms: A Common Cause of Persistent Infections. Science 1999, 284, 1318–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, R.; Tiwari, M.; Donelli, G.; Tiwari, V. Strategies for Combating Bacterial Biofilms: A Focus on Anti-Biofilm Agents and Their Mechanisms of Action. Virulence 2018, 9, 522–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widmer, A.F.; Gaechter, A.; Ochsner, P.E.; Zimmerli, W. Antimicrobial Treatment of Orthopedic Implant-Related Infections with Rifampin Combinations. Clinical Infectious Diseases 1992, 14, 1251–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drancourt, M.; Stein, A.; Argenson, J.N.; Zannier, A.; Curvale, G.; Raoult, D. Oral Rifampin plus Ofloxacin for Treatment of Staphylococcus-Infected Orthopedic Implants. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1993, 37, 1214–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conway, J.; Delanois, R.E.; Mont, M.A.; Stavrakis, A.; McPherson, E.; Stolarski, E.; Incavo, S.; Oakes, D.; Salvagno, R.; Adams, J.S.; et al. Phase 1 Study of the Pharmacokinetics and Clinical Proof-of-Concept Activity of a Biofilm-Disrupting Human Monoclonal Antibody in Patients with Chronic Prosthetic Joint Infection of the Knee or Hip. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2024, 68, e00655–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stéphanie, Pascual; et al. Potential value of a rapid syndromic multiplex PCR for the diagnosis of native and prosthetic joint infections: a real-world evidence study. J. Bone Joint Infect. 2024, 9, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyo-Lim Hong. Targeted Versus Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing-based Detection of Microorganisms in Sonicate Fluid for Periprosthetic Joint Infection Diagnosis. e1456 CID 2023:76 (1 February).

- Yuk Yee Chong, Ping Keung Chan1, Vincent Wai Kwan Chan, Amy Cheung, Michelle Hilda Luk, Man Hong Cheung, Henry Fu1 and Kwong Yuen Chiu. Application of machine learning in the prevention of periprosthetic joint infection following total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review. Arthroplasty 2023, 5, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNally M, Sousa R, Wouthuyzen-Bakker M, Chen AF, Soriano A, Vogely HC, et al. The EBJIS defnition of periprosthetic joint infection. Bone Joint J. 2021, 103-B, 18–25.

- Chen, W.; Hu, X.; Gu, C.; Zhang, Z.; Zheng, L.; Pan, B.; Wu, X.; Sun, W.; Sheng, P. A machine learning-based model for “In-time” prediction of periprosthetic joint infection. DIGITAL HEALTH Volume 10: 1–15 : sagepub.com/journals-permissions. https://doi.org/10.1177/20552076241253531 journals.sagepub.com/home/dhj. [CrossRef]

| Musculoskeletal Infection Society (MSIS) 2011 [8] |

International Consensus Meeting 2013 [9] |

IDSA 2013 [4] | Musculoskeletal Infection Society (MSIS) 2018 [5] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infected if at least one major criteria is present: - Two positive periprosthetic cultures with phenotypically identical organisms - A sinus tract communicating with the joint - Presence of purulence in the affected joint - Positive histologic analysis of periprosthetic tissue - A single positive culture |

Infected if at least one major criteria is present: - Two positive periprosthetic cultures with phenotypically identical organisms - A sinus tract communicating with the joint |

Infected if one of the following criteria is present: - Sinus tract communicating with prosthesis - Presence of purulence - Acute inflammation on histopathologic evaluation of periprosthetic tissue - Two or more positive cultures with the same organism (intra-operatively and/or pre-operatively) - Single positive culture with virulent organism |

Infected if at least one major criteria is present: - Two positive cultures of the same organism - Sinus tract with evidence of communication to the joint or visualization of the prosthesis |

| Infected if at least four out of six minor criteria exist: - Elevated CRP and ESR - Elevated synovial fluid PMN% |

Infected if three out of five minor criteria exist: - Elevated CRP and ESR - Elevated synovial fluid WBC count or ++ change on leukocyte esterase test strip -Elevated synovial fluid PMN% -Positive histologic analysis of periprosthetic tissue -A single positive culture |

Infected if preoperative diagnosis score ≥ 6 / Possibly infected if preoperative diagnosis score between 2 and 5: - Elevated CRP or D-Dimer (Serum): 2 - Elevated ESR (Serum): 1 - Elevated synovial WBC count or LE (Synovial): 3 - Positive alpha-defensin (Synovial): 3 - Elevated synovial PMN (%): 2 - Elevated synovial CRP: 1 Infected if intraoperative diagnosis score ≥ 6 / Possibly infected if intraoperative diagnosis score between 4 and 5: - Positive histology: 3 - Positive purulence: 3 - Single positive culture: 2 |

| Type of Infection |

Time of presentation | Mechanism of infection | Clinical Presentation | Organisms | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early | < 3 months | Intraoperative contamination |

Acute | Acute Sudden onset erythema, edema, warmth, and tenderness |

Virulent bacteria (i.e., Staphylococcus aureus) |

| Delayed | 3-12 months | Intraoperative contamination |

Chronic | Joint pain and stiffness |

Low virulent bacteria (coagulase-negative staphylococci) |

| Late | >12 months | Hematogenous Seeding Intraoperative contamination |

Acute Chronic |

Sudden-onset erythema, edema, tenderness and warmth, Joint pain, sinus tract |

Virulent bacteria (i.e., S.aureus) Low virulent bacteria (i.e., Propionibacterium acnes) |

| T/N/M | Classification | Subclassification | Descriptive |

|---|---|---|---|

| T: Tissue and Implant Conditions | T0 T1 T2 |

a b a b a b |

Stable standard implant without important soft tissue defect Stable revision implant without important soft tissue defect Loosened standard implant without important soft tissue defect Loosened revision implant without important soft tissue defect Severe soft tissue defect with standard implant Severe soft tissue defect with revision implant |

| N: Non-human Cells (Bacteria and Fungi) | NO N1 N2 |

a b a b a b c |

No mature biofilm formation (former: acute), directly postoperatively No mature biofilm formation (former: acute), late hematogenous Mature biofilm formation (former: chronic) without ‘difficult to treat bacteria’ Mature biofilm formation (former: chronic) with culture-negative infection Mature biofilm formation (former: chronic) with ‘difficult to treat bacteria’ Mature biofilm formation (former: chronic) with polymicrobial infection Mature biofilm formation (former: chronic) with fungi |

| M: Morbidity of the Patient | M0 M1 M2 M3 |

a b c |

Not or only mildly compromised (Charlson Comorbidity Index: 0–1) Moderately compromised patient (Charlson Comorbidity Index: 2–3) Severely compromised patient (Charlson Comorbidity Index: 4–5) Patient refuses surgical treatment Patient does not benefit from surgical treatment Patient does not survive surgical treatment |

| Author Year Reference | Study design | Patients N | Bacteria Major strains isolated | Antibiotics | Antibiotic duration (mean) | Follow-up (mean) Months | Success treatment rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berdal et al. 2005 [20] | Prospective | 29 | Staphylococcus aureus | Rifampicin plus Cirpofloxacin | 3 Months | 22.5 | 83 |

| Soriano et al. 2006 [21] | Prospective | 39 | Gram positive Cocci | Levofloxacin plus Rifampicin | 2.7 +/-1 Months | 24 | 76.6 |

| Martínez-Pastor et al. 2009 [22] | Prospective | 47 | Enterobacteriaceae family | Bata-lactam for IVFluoroquinolones for oral | Intraveinous 14 days Oral 2.6 months |

15.4 | 74.5 |

| Cobo et al. 2010 [23] | Prospective | 117 | Gram negative strains Gram positive cocci |

Not reported | 2.5 Months | 25 | 57.3 |

| Vilchez et al. 2011 [24] | Prospective | 53 | Staphylococcus aureus | IV: 11 ± 7 days and oral 88 ± 46 days |

24 | 75.5 | |

| Tornero et al. 2015 [25] | Prospective | 143 | Gram negative strains Gram positive cocci |

Fluoroquinolones Rifampicin in combination |

IV: 8 days Oral 69 days |

48 | 88.2 |

| Author Year (Reference) | Study design | Bacteria (Major Strains Isolated) | Antibiotics (Major prescribed) | Antibiotic duration | Patients in each arm | Outcome & Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bernard et al. 2010 [30] |

Prospective observational, non-randomized monocentric |

Staphylococci (66%) |

Rifampicin (n=58, always in combination and only for staphylococcal infections), Ciprofloxacin (n=42), vancomycin (n=40), and amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (n=25). |

6 weeks vs 12 weeks |

144 episodes -6 weeks: 70 episodes (70/144, 49%) -12 weeks: 74 episodes(74/144, 51%) |

Overall cure in 115 episodes (80%) -6 weeks: 90% cure vs. -12 weeks: 55% Failure 29 (20%) antibiotic therapy might be able to be limited to a 6-week course Randomized trials are needed |

|

Puhto et al., 2012 [26] |

Retrospective observational, pre-post-design monocentric |

Staphylococcus aureus (42%) |

Rifampicin and fluoroquinolones for GP strains |

2-3 months vs 3-6 months |

ITT: long n= 60 Short n= 72 PP: long n=38 Short n=48 |

Non-inferiority of short treatments. Cure rates: ITT—Long 57%, Short 58% (p = 0.85) PP—Long 89%, Short 87% (p = 0.78) Short antibiotic treatment seems to be a good alternative for patients treated with DAIR prospective randomized controlled trials are urgently needed |

|

Lora-Tamayo. et al., 2013 [27] |

Retrospective observational, multicenter |

Staphylococcus aureus |

(>75% rifampin-based combinations) |

<61 days 61–90 days >90 days |

231 patients n=52 n=52 n=127 |

Cure rate: <61 days—75% 60–90 days—77% >90 days—77% (p = 0.434) |

|

Lora-Tamayo. et al., 2016 [28] |

Randomized, open clinical trial, multicenter |

Staphylococci |

Levofloxacin and Rifampicin |

8 weeks vs 3–6 months 3 months for hip prostheses and 6 months for knee prostheses |

N= 63 ITT: long n= 33 Short n= 30 PP: long n=20 Short n=24 |

Non-inferiority. Cure rates: ITT—Long 58%, Short 73% (Δ = −15.7 95% CI −39.2% to +7.8%) PP—Long 95%, Short 92% (Δ = +3.3% 95% CI −11.7%to +18.3%) 8 weeks of L+R could be non-inferior to longer standard treatments for acute staphylococcal PJI managed with DAIR |

| Chaussade et al. 2017 [31] | Retrospective observational, multicenter |

Staphylococci (40%) |

Rifampin-based combinations for GP and fluoroquinolones |

6 weeks vs. 12 weeks |

N= 87 -6 weeks n=44 -12 weeks n=43 |

Cure rates: 67.4% in the long treatment group 70.5% in the short treatment group (aOR 0.76, 95%CI 0.27–2.10) Prospective randomized trials are required |

|

Bernard et al. 2021 DATIPO [32] |

Randomized, open clinical trial, multicenter |

Staphylococcus aureus (30-40%) |

Rifampin-based combinations and fluoroquinolones |

6 weeks vs. 12 weeks |

N= 151 -6 weeks n=75 -12 weeks n=76 |

Failure rate for 6 weeks: 30.7% Failure rate for 12 weeks: 14.5% Difference: 16.2% (95% CI: 2.9% to 29.5%) Non inferiority was not shown |

| Author (year, reference) | Patients N | Study design | Antibiotics (major prescribed) | Antibiotic duration | Local antibiotics or suppressive | Follow-up (mean) Years | Outcome | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whiteside et al. (2011) [50] | 18 | Retrospective Cohort | Not reported | Intravenous 2-4 weeks |

Local Vancomycin : intraaticular |

5.1 |

RR = 5.5% FO: Mean KSS was 78 ± 8 at 1year, 83 ± 9 at 2 years, 84 ± 8 at 5years, 85 ± 10 at 6 years, and 84 at 8 years |

A single-stage revision total TKA for MRSA infection, managed with six weeks of intra-articular vancomycin administration, effectively controlled the infection |

|

Singer at al. (2012) [41] |

57 | Retrospective | Rifampicin fluoro-quinolones Combination : 50.8% |

Overall duration : 6 weeks -2 weeks IV after surgery – 4 weeks : oral antibiotics |

Local Gentamicin | 3 | RR = 15% FO: KSS after surgery was 72 points (range, 20–98 points), the Knee Society function score was 71 points (range, 10–100 points), and the Oxford–12 knee score was 27 points (range, 13–44 points). |

One-stage revision of knee PJI leads to a high rate of infection control of 95% and reasonable patient function when the pathogen is identifiable and when MRSA and MRSE infections are excluded. Recurrence is about 15% in hinged prothesis |

| Jenny et al. (2013) [38] | 47 | Observational Cohort Prospective | -IV : vancomycin, teicoplanin -Oral Rifampicin Levofloaxcin |

-IV : 3.5 (1–16 weeks), -Oral : 12 (3–16 weeks) |

Suppressive ATB : not reported | 3 | RR = 12% FO: The median preoperative KSS function score was 42 points. 56% of the patients had a KSS of >150 points postoperatively | Single-stage exchange may offer a viable alternative for managing chronically infected TKA, providing a more convenient approach for patients by avoiding the risks associated with two separate surgeries and hospitalizations, while also reducing overall healthcare costs. |

| Baker et al (2013) [51] | 33 | Prospective | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 0.5 (7 months) |

RR = 21% FO: The mean pre– and post–operative OKS were 15 (95% CI, 13–18) and 25 (95% CI, 21–29), respectively, giving a mean improvement of 10 (95% CI, 5–14) | No difference between single-stage and two-stage revision of the infected knee replacement |

| Shanmugasundaram et al. (2014) [42] | 5 | Retrospective | Not reported | Not reported | Antibiotic spacers | 2 | RR = 17.2% FO: Not reported | In hip prosthetic joint infections (PJI), the initial success rate was 60% for one-stage exchange and 70% for two-stage exchange. For knee PJI, success rates were higher—80% for one-stage exchange and 75% for two-stage exchange. Future advances in microbiological diagnosis are needed |

| Tibrewal et al. (2014) [45] | 50 | Prospective | Not reported | -IV : 2 weeks -Oral : 3 months |

Antibiotic-impregnated cement | 10 | RR = 2% FO: the mean OKS increased by a factor of 2.4 from 14.5 (6 to 25) pre–operatively to 34.5 (26 to 38) one year after surgery. This represents a mean absolute improvement of 20.0 points (95% CI: 17.8 to 22.2, p < 0.001). | Single-stage revision may achieve clinical outcomes comparable to those of two-stage revision. Additionally, the single-stage approach is associated with reduced healthcare costs, lower patient morbidity, and decreased overall inconvenience. |

| Cury Rde P et al. (2015) [52] | 6 | Retrospective | Not reported | -IV : 2-4 weeks -Oral : 6 months |

Suppressive : 4 patients | 3 | RR = 16.7% FO: WOMAC score 49.5 (47–55) |

The DAIR, one-stage revision and two-stage revision success rates were 75%, 83.3%, and 100%, respectively |

| Haddad et al. (2015) [35] | 28 | Retrospective | Not reported | -6 Weeks (IV and/or Oral) | antibiotic-loaded cement Gentamicin Vancomycin | 2 | RR = 0% FO: KSS was higher in the single–stage group than in the two–stage group (mean, 88; range, 38–97 versus 76; range, 29–93; p < 0.001) Preoperative mean KSS was 32 in the single–stage group (range, 18–65) |

Single-stage approach can be an alternative to the two-stage procedure in carefully selected patients with chronically infected TKA. Prospective trials are needed. |

| Zahar et al. (2016) [53] | 46 | Retrospective | Not reported | 14.2 ( 10–17 days) | Antibiotic-loaded cement Gentamicin ClindamycinVancomycin |

10 | RR = 7% FO: HSS score improved significantly from a mean preoperative value of 35 (±24.2 SD; range, 13–99) to an average of 69.6 (±22.5 SD; range, 22–100) |

The overall infection control rate was of 93% and good clinical results Further research into one-stage exchange techniques for PJI in TKA are needed |

| Cochran et al. (2016) [39] | 3069 | Retrospective Observational Database | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 6 | RR = 24.6% at 1 year and 38.25% at 6 years FO: Not reported |

Two-stage reimplantation, despite 19% recurrence, had the highest success rateover single-stage and DAIR. |

| Jenny et al. (2016) [43] | Intervention group = 54, Control group = 77, | Retrospective case-control | Not reported | 3 months | Not reported | 2 | RR = Intervention group: 15% Control group: 22% FO: KSS over 160 points (80%). No significant difference between the two groups | When a single-stage exchange is performed, patient selection does not appear to influence the outcome. |

| Massin et al. (2016) [40] | 108 | Retrospective | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 2 | RR = 24% FO: IKS 88.6 ± 9.4 |

One-stage procedures are preferable in women, because they offer greater comfort without increasing the risk of recurrence. Routine one-stage procedures may be a reasonable option in the treatment of infected TKR |

| Li et al. (2017) [37] | 22 | Retrospective | Vnacomycin | 4-6 weeks | Not reported | 5 | RR = 9.1% FO: Not reported |

No significant difference between single–stage and two–stage revision in terms of satisfaction rates, and overall infection control rates. |

| Castellani et al. (2017) [36] | 14 | Retrospective | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 1 | RR = 7.2% FO: Not reported |

Superiority of one- versus two-stage revision and the value of antibiotic-free periods prior to definitive revision remain unclear. Large prospective studies or randomized controlled trials are needed |

| Author year Reference | Study design | Patients/ Prothesis site | Bacteria (major strains isolated) | Systemic antibiotics |

Systemic antibiotics duration (days) |

Local antibiotics | Mean follow up (Months) |

Outcome Additional Intra operative positive Persistence/Relapse debridement cultures at reimplantation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Taggart et al., 2003 [64] |

Prospective observational, single-center, non-comparative |

33/Hip & Knee | 93% Gram-positives 71% staphylococci |

Not reported | 5 | Vancomycin | 67 | 0% 9% 3% |

|

Hoad-Reddick et al., 2005 [56] |

Prospective observational, single-center, non-comparative |

52/knee |

63% staphylococci |

None Cefuroxime as prophylaxis |

1 |

Various | 56 | 12% 16% 9% |

|

Hart & Jones, 2006 [65] |

Prospective observational, single-center, non-comparative |

48/knee | 96% Gram-positives 76% staphylococci |

Vancomycin | 14 | Vancomycin+ gentamicin | 49 | 13% 23% 13% |

|

Stockley et al., 2008 [57] |

Prospective observational, single-center, non-comparative |

114/hip |

61% staphylococci |

NoneCephalosporin as prophylaxis | 1 | Various | 74 | 4% 16% 12% |

|

Whittaker et al., 2009 [66] |

Prospective observational, single-center, non-comparative |

44/Hip | All Gram-positives 72% staphylococci |

Vancomycin | 14 | Vancomycin+ gentamicin | 49 | 7% 2% 7% |

|

McKenna et al., 2009 [58] |

Retrospective, observational, single-center, non-comparative |

31/Hip | All Gram-positives 77% staphylococci |

Vancomycin | 5 | Various | 35 | 0% 0% 0% |

|

Mittal et al., 2007 [67] |

Retrospective, observational, multicenter, comparative |

37/knee | Methicillin-resistant staphylococci |

Not reported | ≥6 weeks IV vs. <6 weeks IV |

Various | 51 | - 0% Short: 2/15 (13%) Long: 2/22: (9%) (p = 0.07) |

|

Hsieh et al., 2009 [68] |

Retrospective, observational, single-center, comparative |

99/knee | 67% Gram-positives 53% staphylococci |

A first-generation cephalosporin and gentamicin | 4–6 weeks vs. 7 days |

Various | 43 | Long 2/46 (4%) - Long: 2/46 (4%) Short 1/53 (2%) Short: 3/53 (6%) |

|

El Helou et al., 2011 [69] |

Retrospective, observational, single-center, comparative, propensity score-adjusted |

208/hip and knee | Mainly Gram-positives. 62% staphylococci |

Not reported |

4 weeks +/-7 d vs. 6 weeks +/-7 d |

Vancomycin +/- Tobramycin |

60 | - Short: 6.1% Short: 16% Long: 8.7% Long: 27% |

|

Benkabouche et al., 2019 [60] |

Single-center, open, randomized clinical trial |

39 /Hip & Knee | Various | Vancomycin IV Fluoroquinolones Oral |

6 weeks (39-45 days) Vs 4 weeks (27–30 days) |

Only 2 cases (5%); tobramycin |

26 | No significant difference was observed in the PJI group |

|

Ma et al, 2020 [70] |

Retrospective, observational, single-center, comparative |

64/knee |

69% staphylococci |

Not reported | 4–6 weeks vs.≤7 days | Vancomycin (} aminoglycosides) |

75 | Need for salvage antimicrobials or surgery Long: 11/43 (26%); Short: 3/21 (14%) |

|

Bernard et al., 2021 [32] |

Multicenter, open, randomized clinical trial |

81/Hip & knee | 40% S. aureus | Rifampicin Fluoroquinolones |

6 weeks vs. 12 weeks |

Not reported | ≥24 | Failure: 6 w: 6/40 (15%); 12 w: 2/41 (5%) (p > 0.05) Difference: 10.1% (95%CI −0.9–22.2), longer antibiotic duration is recommended |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).