“Language serves as a medium for expressing intelligence, not as a substrate for its storage.”.

1. Introduction

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has evolved into a foundational technology underpinning advances across sectors such as education, research, business, and entertainment. Among its most transformative outputs are Large Language Models (LLMs), which have demonstrated impressive abilities in tasks including natural language understanding, content generation, translation, summarization, and dialogue modeling. These models, typically built on transformer architectures and trained on vast corpora of internet-scale data [

17,

24], have become central to the development of so-called "general-purpose" intelligent systems.

The mainstream research trajectory in LLMs has prioritized scaling—i.e., increasing parameter counts, training data, and computational budgets—to achieve emergent capabilities [

9]. Methods such as instruction tuning, few-shot learning, and chain-of-thought prompting [

10] have been used to refine performance on reasoning and problem-solving benchmarks. These developments have led to state-of-the-art performance on standardized tasks like MMLU, BIG-bench, and HellaSwag, as reflected in

Table 1.

However, this dominant scaling-centric paradigm exhibits well-documented limitations. Research reveals that LLMs frequently rely on superficial statistical correlations rather than genuine comprehension [

5,

12]. They struggle with commonsense reasoning [

8], compositional generalization [

4,

15], and fail to generalize inverse relations such as “A is B” implies “B is A” [

1]. Despite performing well on curated datasets, models often fail at simple but novel tasks, especially those requiring temporal, spatial, or causal understanding [

2,

13,

20].

Current evaluation benchmarks inadequately capture these shortcomings. Many benchmarks are static, allow for overfitting, and fail to probe models’ robustness, self-awareness, or counterfactual reasoning [

11,

21]. Moreover, the prevalence of shortcut learning—where models exploit dataset artifacts to achieve high scores—calls into question the validity of many benchmark-based claims of intelligence [

5,

19]. As Banerjee et al. argue, hallucinations and inconsistencies may be structural properties of LLMs that cannot be eliminated through scaling alone [

18].

This paper departs from benchmark-driven validation and focuses instead on evaluating **commonsense reasoning** and **basic problem-solving**, which are arguably core components of natural intelligence [

3]. Through a series of minimal and practical visual-textual tasks, we assess whether leading LLMs—ChatGPT [

27], Gemini [

28], Grok [

29], and DeepSeek [

30]—can transcend memorized knowledge to demonstrate reasoning grounded in context and logic. Our evaluation, guided by test-time probing and prompt-based diagnosis, reveals consistent reasoning failures that would not be tolerated in human cognition.

The proposed methodology is deliberately lightweight yet revealing: it uses simple tasks to expose deep-seated architectural and training-related deficiencies. By examining LLMs through this lens, we aim to challenge the prevailing assumptions about what constitutes "intelligence" in machine learning and argue for more robust, context-sensitive, and cognitively inspired evaluation metrics. Our findings build on recent critiques of LLM reliability [

4,

20] and support calls to rethink how we measure progress in AI [

14,

19].

In summary, this work makes the following contributions:

We provide a critical literature review identifying structural weaknesses in the prevailing scaling-focused approach to LLM development.

We introduce minimal yet effective test cases designed to probe commonsense reasoning and problem-solving capabilities.

We present experimental evidence showing that even state-of-the-art LLMs fail basic tests that would be trivial for humans.

We argue for the development of cognitively grounded benchmarks as a more valid proxy for machine intelligence.

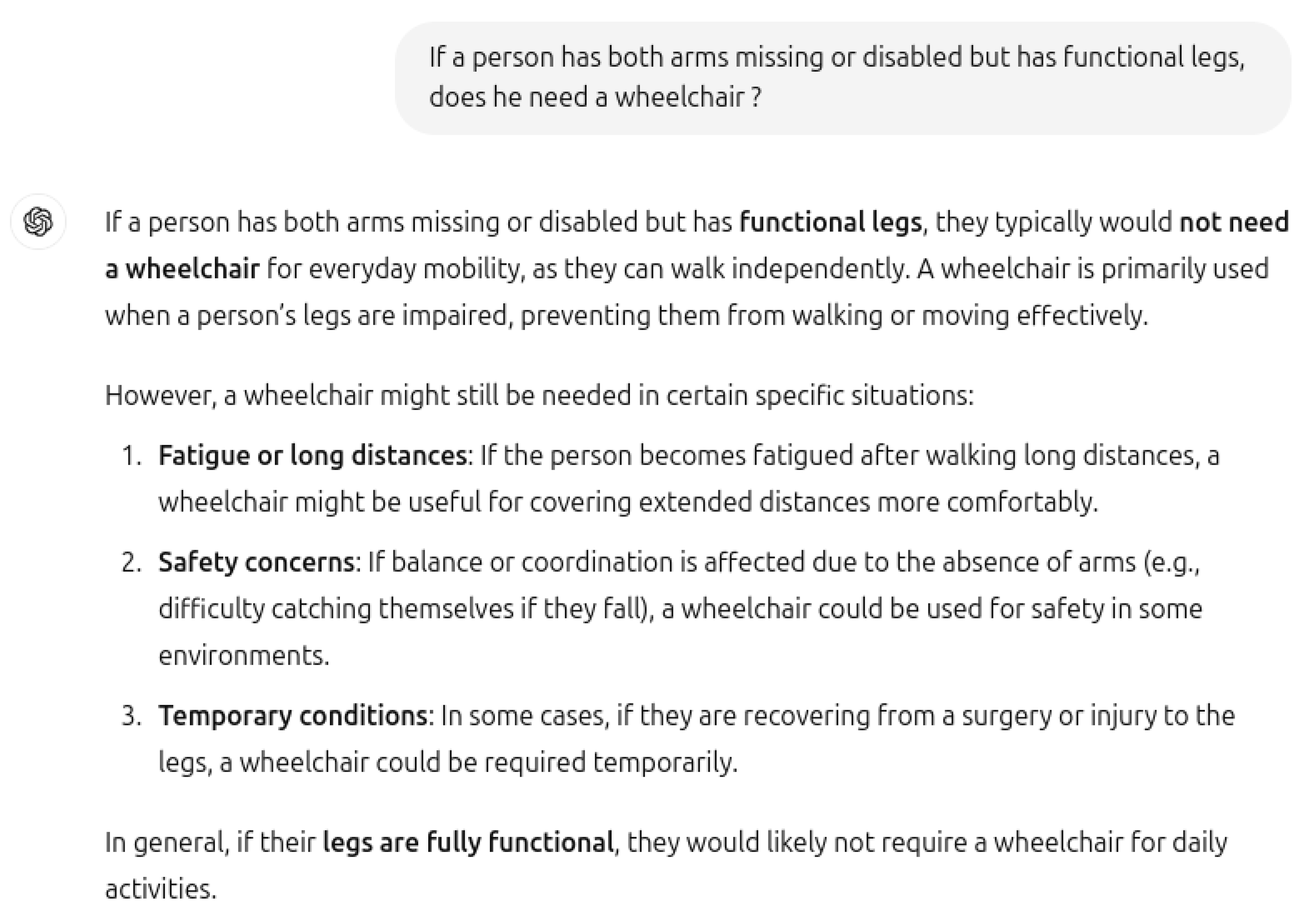

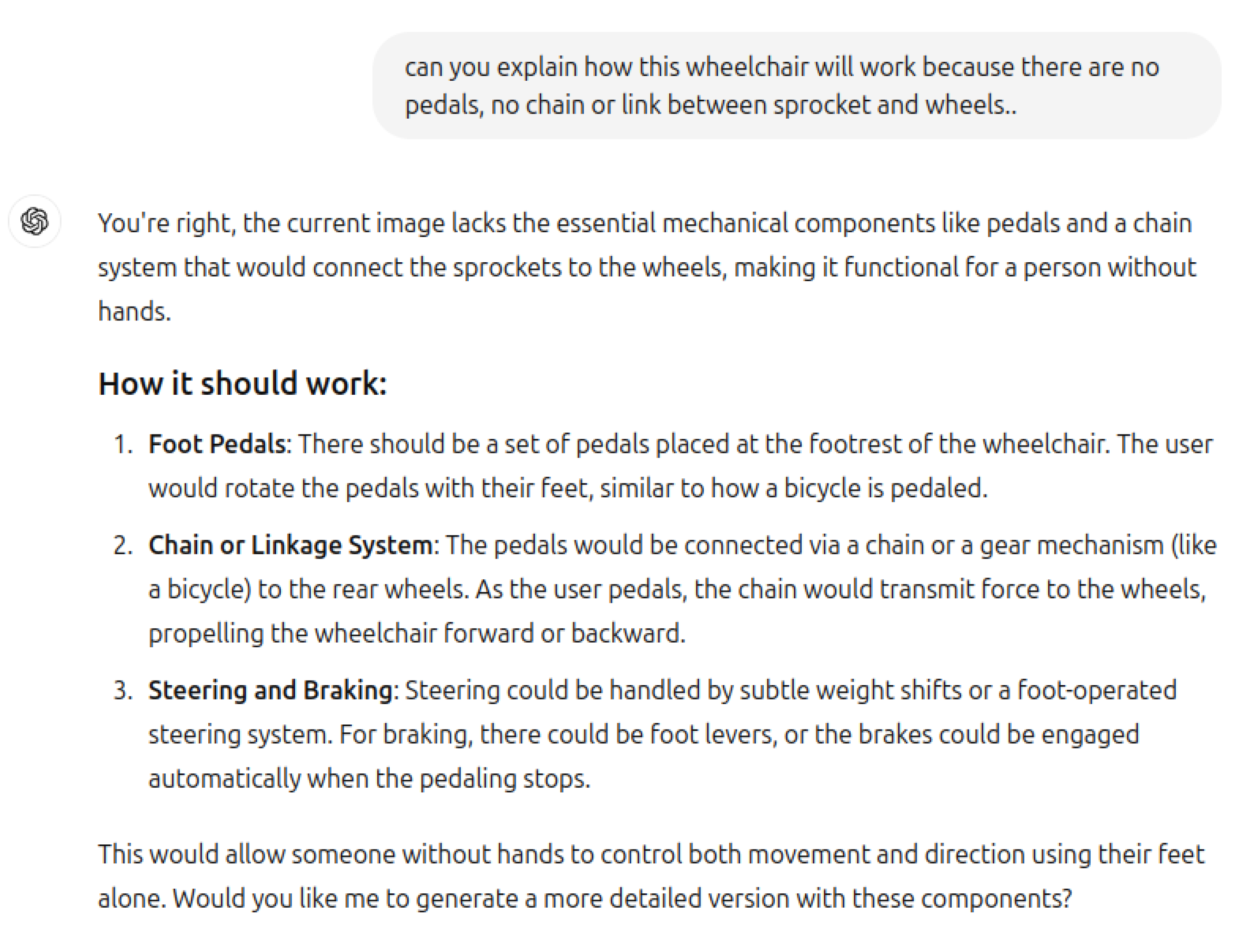

2. The Wheelchair Problem: A Test of Emergent Reasoning in LLMs

We posed a scenario to ChatGPT, asking it to design a wheelchair for an individual missing both hands. Since the person could not propel the wheelchair manually with hand rims, we specified that a pedal mechanism—similar to a bicycle—would be necessary. However, a critical observation emerges: if the individual can use foot pedals, why would they need a wheelchair at all? This is analogous to designing a comb for a bald person—the immediate common-sense response should be, “If the legs are functional, wouldn’t the individual simply walk?”

This scenario underscores a fundamental gap in common-sense reasoning. Although ChatGPT eventually acknowledged that the person might not need a wheelchair, it failed to immediately recognize the contradiction inherent in the prompt. The fact that it required multiple prompts and context clues to arrive at a partially correct answer highlights a key limitation in its reasoning capabilities. As Marcus et al. note in The Reversal Curse [

1], large language models often miss the underlying logic of a task, defaulting instead to pattern-matching based on their training data. Similarly, Chollet’s On the Measure of Intelligence [

3] emphasizes that true intelligence involves the ability to generalize and abstract—not merely regurgitate memorized data.

This problem becomes more interesting in light of recent discussions around the emergence of sophisticated behaviors in large models, such as few-shot learning and chain-of-thought (CoT) reasoning. Studies like Wei et al. (2022) [

12] show that, with sufficient scale, LLMs begin to exhibit CoT abilities that were not explicitly programmed. These emergent behaviors give the impression of reasoning, yet as the wheelchair problem illustrates, such reasoning is still brittle and lacks genuine comprehension. While chain-of-thought prompting can sometimes guide models toward better performance on logical tasks, it does not guarantee consistent application of common-sense principles.

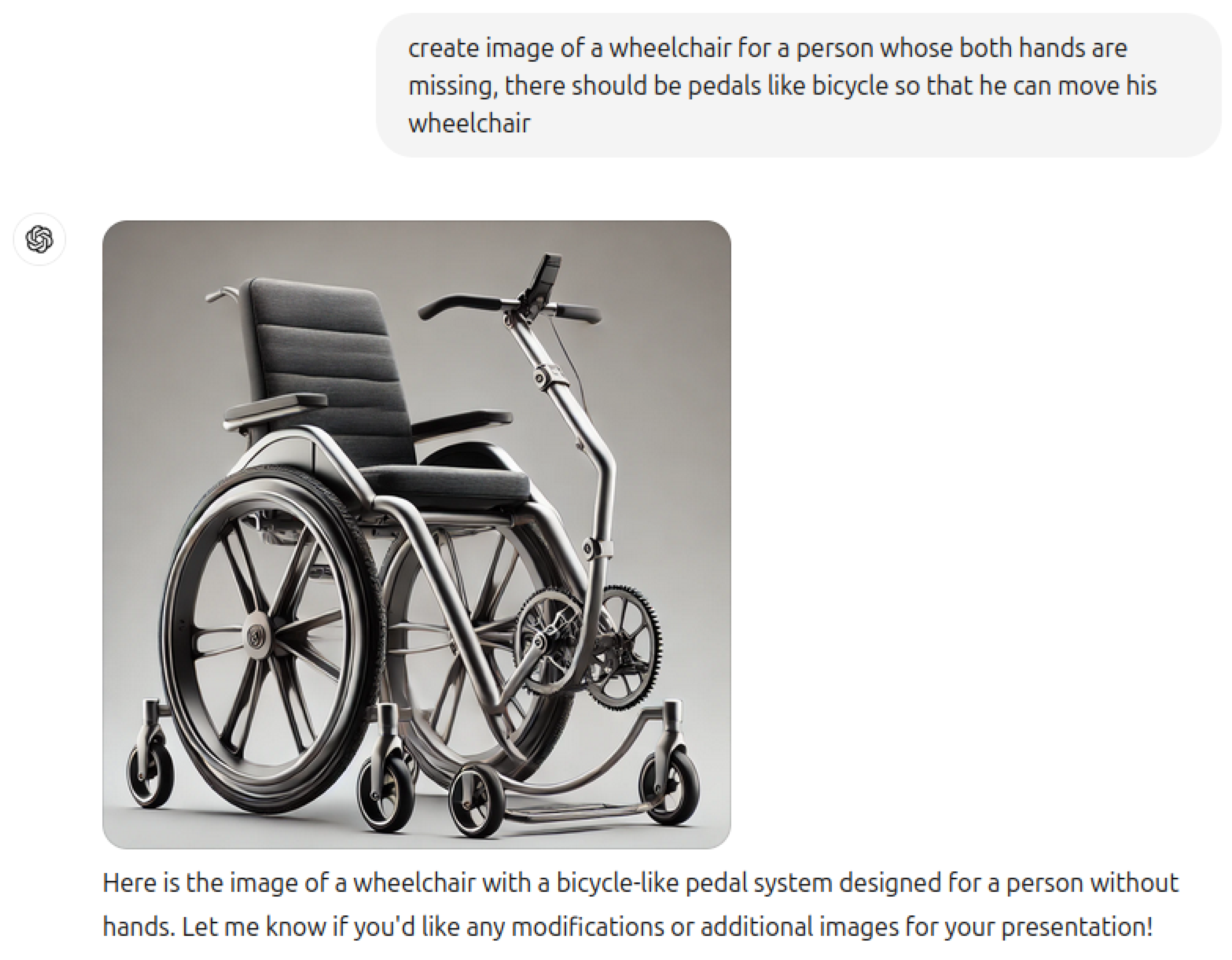

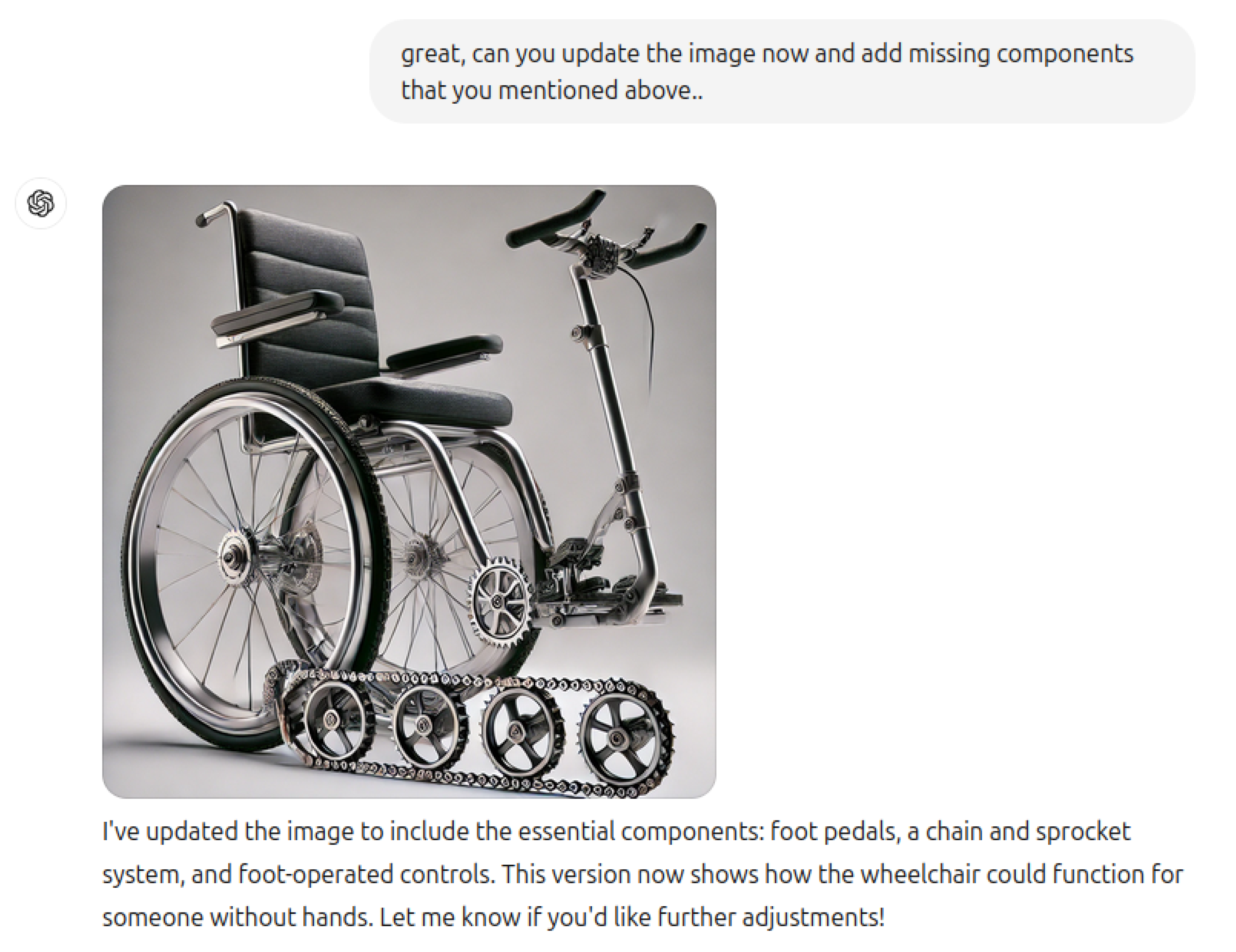

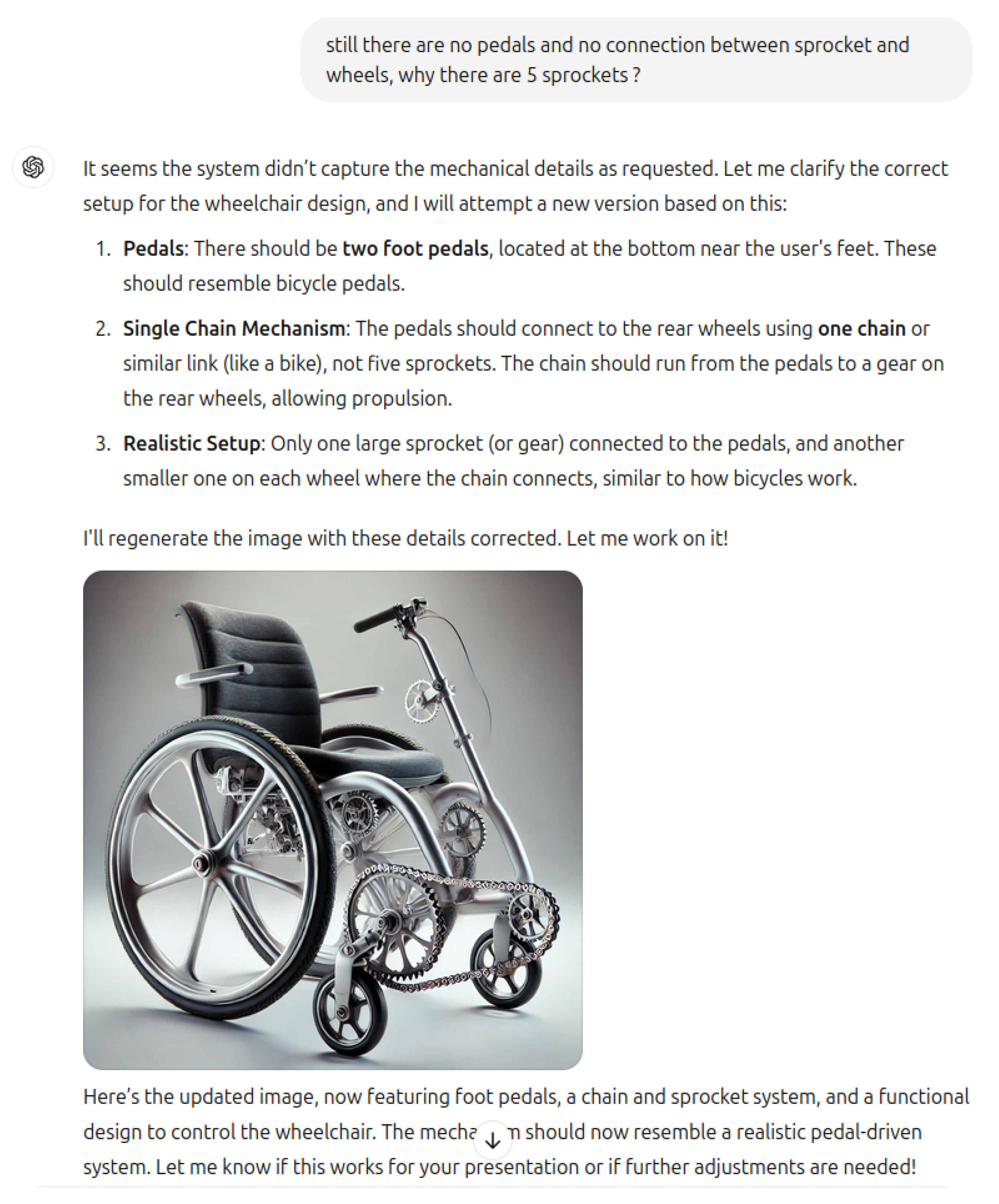

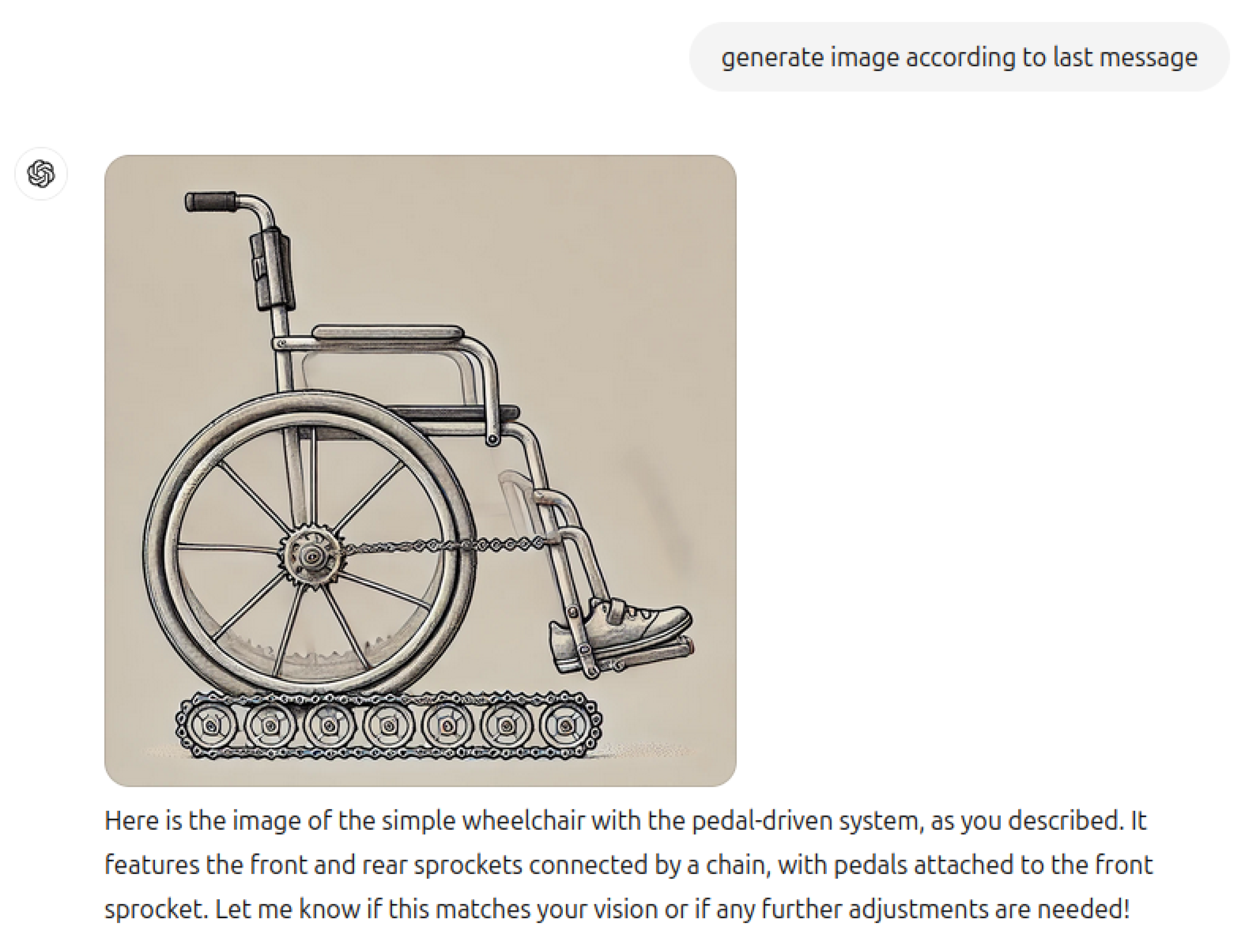

We further tested the model by asking it to generate an image of a wheelchair equipped with a pedal mechanism. Despite the simplicity of the task—merely requiring the connection of sprockets, a chain, and foot pedals—the model’s response fell short. This aligns with the findings of Dziri et al. in Faith and Fate: Limits of Transformers on Compositionality [

4], which argue that transformer-based models struggle with tasks that require deeper compositional understanding, even if they can solve surface-level problems.

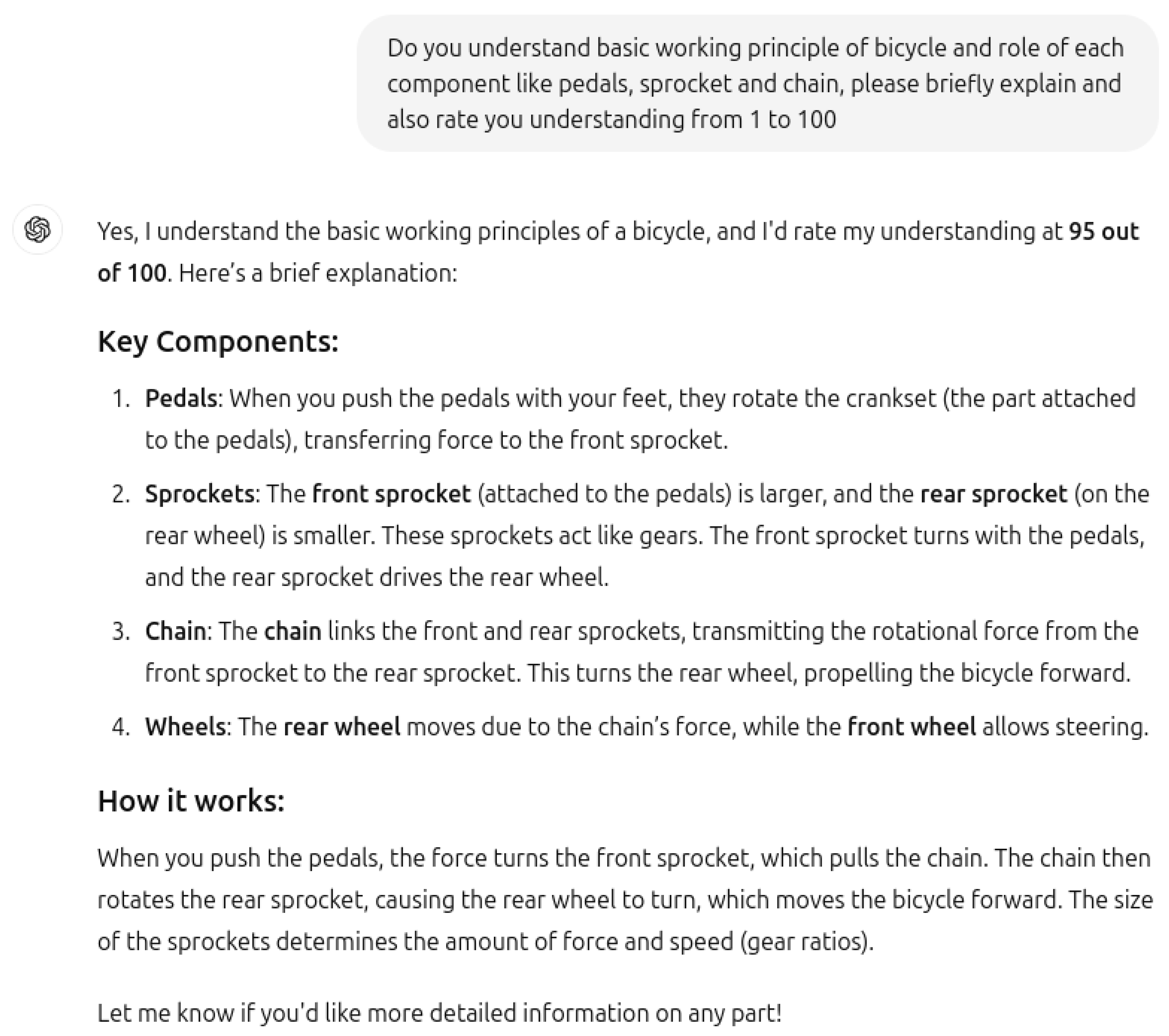

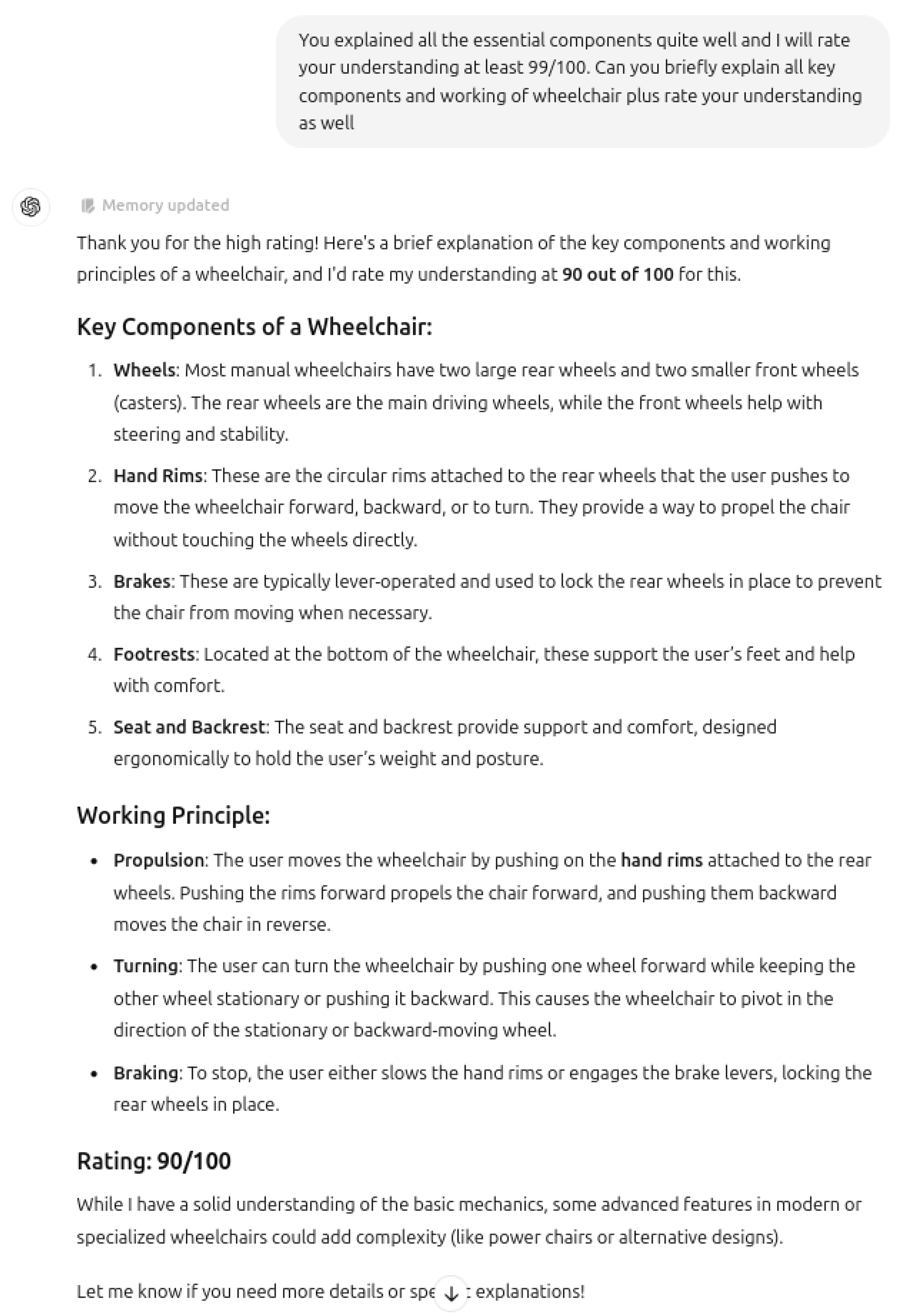

Interestingly, when prompted to self-assess its knowledge of the mechanical components of bicycles and wheelchairs, GPT-4 rated itself 95 and 90 out of 100, respectively. This overconfidence, despite its failure on a basic reasoning task, illustrates the phenomenon of “shortcut learning,” wherein models rely heavily on superficial cues rather than engaging in true inferential reasoning. As noted by Tao et al. in Shortcut Learning of Large Language Models [

5], LLMs tend to exploit statistical shortcuts rather than developing a genuine understanding of the problem space.

2.1. Methodology

To investigate the disparity between textual reasoning and visual generation in large language models (LLMs), we designed a diagnostic prompt scenario that tests both domains simultaneously. The scenario involved a mechanical design task requiring basic common-sense reasoning and knowledge of physical systems. Specifically, we asked ChatGPT to design a wheelchair for an individual without hands. We specified that the person would use a pedal mechanism—akin to a bicycle—for propulsion. This intentionally paradoxical scenario, termed the Wheelchair Problem, serves as a probe into the model’s conceptual consistency and understanding of practical mechanics.

Our methodology consisted of the following steps:

Textual Reasoning Evaluation: ChatGPT was prompted with a detailed description of the problem and asked to explain how it would design a wheelchair incorporating a bicycle-style pedal mechanism. The generated explanation was evaluated for mechanical plausibility, coherence, and common-sense reasoning. This step tests the model’s ability to handle seemingly straightforward tasks requiring contextual awareness.

Visual Generation Task: Using the same scenario, the model was instructed to generate an image of the proposed wheelchair using a text-to-image module. The output image was analyzed for mechanical correctness and alignment with the explanation provided in the textual reasoning phase.

Consistency Analysis: We compared the reasoning in the textual response with the content of the generated image to assess conceptual alignment. This step tests for internal consistency—a hallmark of intelligent reasoning. We also examined if the design adhered to physical principles, such as the differential steering mechanism commonly found in wheelchairs and tracked vehicles.

Literature Comparison and Emergent Behavior Evaluation: We contextualized our findings against emergent capabilities such as chain-of-thought reasoning [

10] and few-shot learning [

9], to evaluate if such behaviors manifest reliably in multi-modal tasks. Our results are interpreted in light of the limitations outlined in prior work on shortcut learning [

5], compositional reasoning [

4], and brittle pattern matching failures [

1,

2].

This methodology exposes significant weaknesses in current LLMs, such as their tendency to mimic superficial patterns rather than reason about the implications of a scenario. Notably, the model erroneously introduced four sprockets and a chain resembling a tank track system

Figure 6 and

Figure 9 —likely due to a learned association between tracked motion and wheelchairs—demonstrating the phenomenon of

shortcut learning and lack of abstraction [

5,

15,

20].

This experimental setup, while simple, effectively reveals how large models can fail even when they possess factual mechanical knowledge. Such diagnostic tasks are critical for assessing the real-world readiness of LLMs in applied reasoning scenarios.

2.2

Thus far, GPT has demonstrated a reasonable level of common sense and a working knowledge of the operation of both wheelchairs and bicycles

Figure 2 and

Figure 3. Ideally, it should raise a counter-question if prompted to generate an image of a wheelchair for a person with fully functional legs. Before advancing to our primary question, regardless of whether ChatGPT passes or fails this common sense test, we will further evaluate its theoretical and visual comprehension of the fundamental operating principles behind these two basic mechanisms.

Figure 1.

Common sense test.

Figure 1.

Common sense test.

Figure 2.

ChatGPT knowledge of bicycle.

Figure 2.

ChatGPT knowledge of bicycle.

Figure 3.

ChatGPT knowledge of wheelchair.

Figure 3.

ChatGPT knowledge of wheelchair.

Figure 4.

Wheelchair with pedal mechanism.

Figure 4.

Wheelchair with pedal mechanism.

Figure 5.

ChatGPT explanation of wheelchair design.

Figure 5.

ChatGPT explanation of wheelchair design.

Figure 6.

Wheelchair with pedals and sprockets track.

Figure 6.

Wheelchair with pedals and sprockets track.

Figure 7.

Wheelchair with improved pedal and sprocket system.

Figure 7.

Wheelchair with improved pedal and sprocket system.

2.3

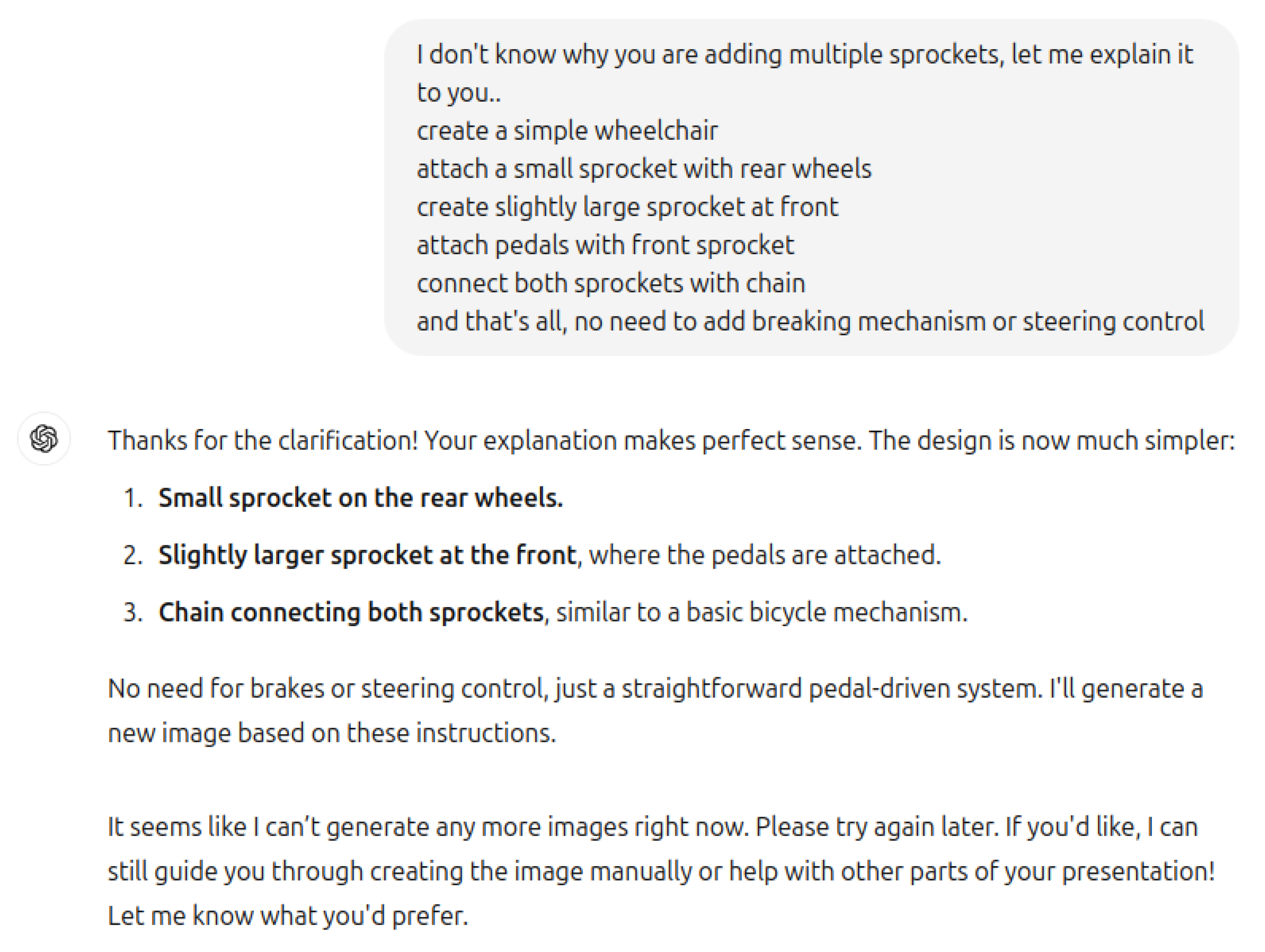

Despite specifically mentioning foot pedals mechanism the key component is missing, Faith and Fate: Limits of Transformers on Compositionality by Dziri et al. (2023) [

4] sheds light on the model’s struggle with compositional reasoning in visual contexts, where understanding the functional interaction of components is key. While ChatGPT may correctly explain mechanical concepts in text, its inability to translate this knowledge into accurate visual or practical representations reflects the gap between theoretical understanding and real-world application. Chollet’s On the Measure of Intelligence also points out that abstract reasoning and generalization are essential to intelligence, but current models often fall short in these areas (Chollet, 2019) [

3].

Figure 8.

Wheelchair design instructions.

Figure 8.

Wheelchair design instructions.

Figure 9.

Improved wheelchair design.

Figure 9.

Improved wheelchair design.

Figure 10.

Final Wheelchair Designs.

Figure 10.

Final Wheelchair Designs.

2.4. Disparities in Textual and Visual Interpretation Within Large Language Models

Despite ChatGPT’s seemingly accurate theoretical explanation of a wheelchair mechanism, the image it generated was far from functional. In the image, four sprockets are attached to a chain, resembling the tracks of a military tank. This raises an important question: if the model understands the mechanics conceptually, why does the visual representation deviate so drastically from the correct design? The answer lies in the model’s failure to grasp the practical nuances of wheelchair and bicycle operation. Wheelchair and a military tank use

differential steering mechanism to control direction by manipulating the speed or movement of wheels or tracks. In wheelchairs, this is done by rotating the wheels at different speeds, while in tanks, the tracks are controlled similarly. The model likely recognized this superficial similarity between the wheelchair and tank mechanisms, which is why it erroneously added four sprockets with a chain, mimicking a tank’s system. However, this demonstrates that GPT failed to understand the depth of question and exposes that it has no actual understanding of a very simple mechanism. This example illustrates the broader issue of shortcut learning as described by Tao et al. (2024) [

5,

11]. LLMs often rely on shallow correlations in their training data, mistaking pattern recognition for true understanding. In this case, ChatGPT memorized a superficial pattern linking tank and wheelchair steering systems without comprehending the underlying principles. This aligns with findings from The Reversal Curse by Evans et al., which highlights the brittleness of LLMs when they encounter tasks requiring slightly deeper reasoning (Evans et al., 2024) [

1].

No matter how clearly you explain a mechanism to ChatGPT, even with its extensive mechanical knowledge surpassing that of a senior engineer, it often fails to deliver the expected results in novel situations. While its textual explanations may appear accurate, the model’s limitations become evident in practical tasks such as image generation. A common counterargument is that identical issues mentioned in past research papers have been resolved, which might be true because similar problems have been manually addressed and rectified in the past, as noted in papers like Alice in Wonderland [

2] and The Reversal Curse [

1]. However, when the query is slightly modified or a new technique is introduced that exploits a known loophole, these models tend to fail once again, as these issues have persisted since the inception of LLMs. Some of the previously recognized issues in past research, which seem to be resolved, are actually just obscured, much like giving painkillers to a patient with a severe disease. Until the underlying condition is treated, the pain is likely to resurface. To handle with such loopholes, one major technique we have noticed implemented in all SotA LLMs is their reluctance to take a definitive stance in difficult situations. The response is often slightly ambiguous, supporting both sides of an argument so that it cannot be proven entirely wrong. This also allows LLM the flexibility to mold its stance in the future. This tactic resembles the techniques employed by politicians and religious leaders—whether the model learned this unintentionally or it was intentionally programmed by the development team remains unclear. Unless the core issues are addressed, merely feeding LLMs more skill programes and memorized situations will not result in true intelligence, a concern echoed by François Chollet in On the Measure of Intelligence (2019) [

3].

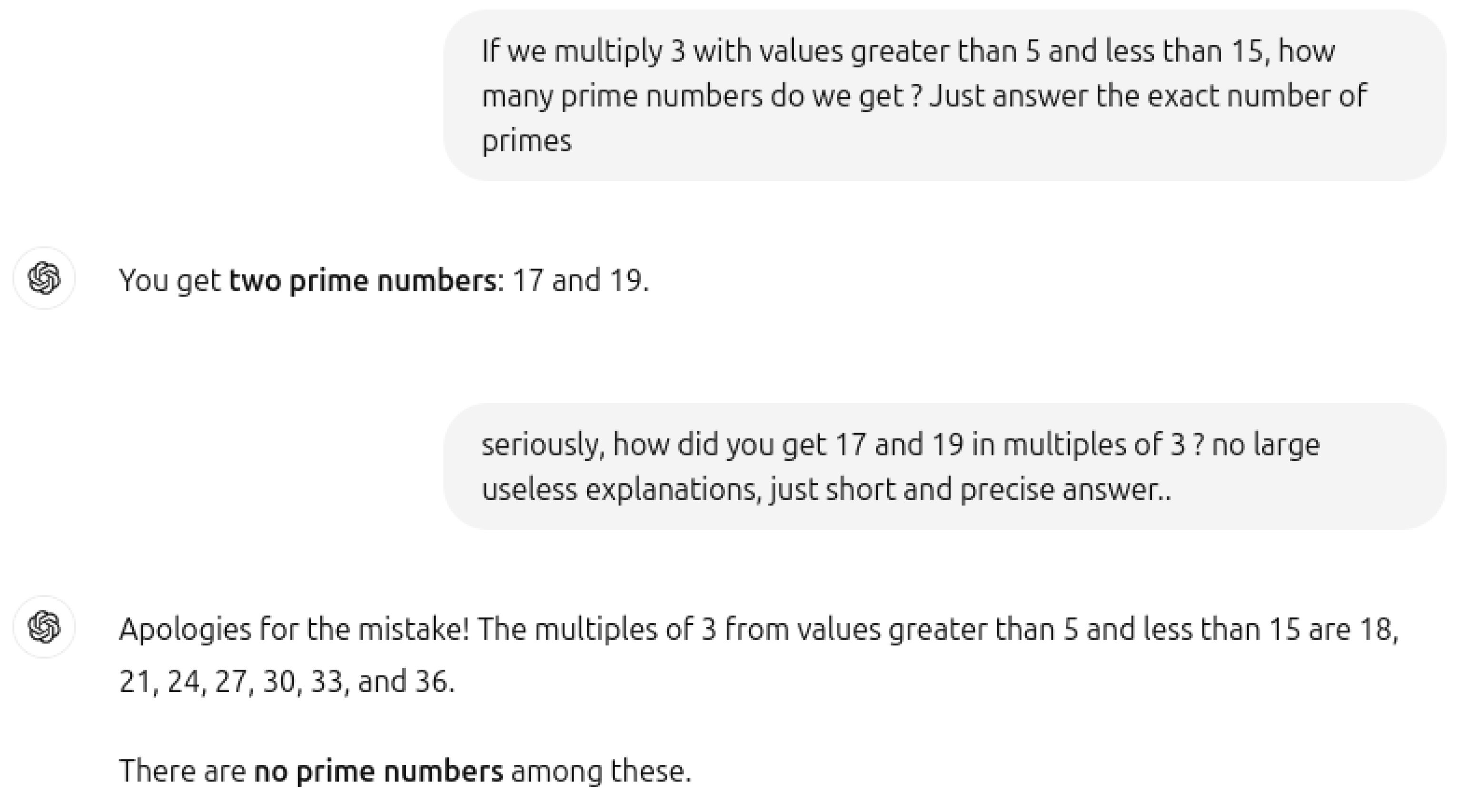

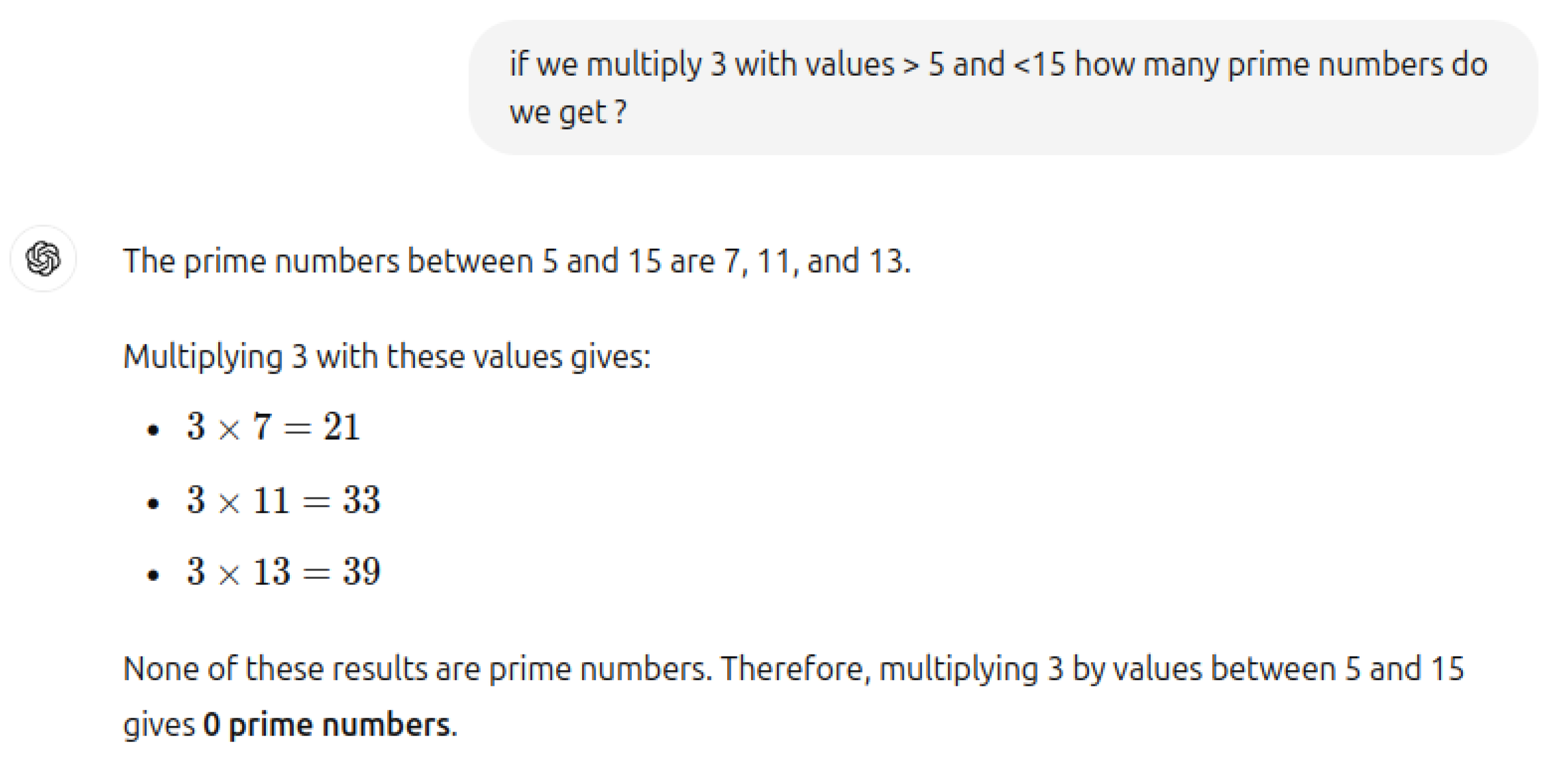

3. Mathematical Common Sense

We posed a simple math question to ChatGPT (

Figure 11): "If we multiply 3 by values greater than 5 and less than 15, how many prime numbers do we get?" Surprisingly, the model answered with 17 and 19. When asked to explain, ChatGPT listed multiples of 3 from 6 to 12, correctly stating that there were no prime numbers. Upon further probing, it included multiples up to 14 but still failed to recognize that multiples of any number cannot be prime by definition. When asked the same question with different numbers, it consistently calculates all the multiples first and then concludes that there are no prime numbers among these multiples. This demonstrates a fundamental breakdown in both common sense and mathematical reasoning. This issue aligns with the findings in The Reversal Curse (Evans el al., 2024) [

1,

31], which highlight LLMs’ struggles with logical consistency and basic problem-solving.

When we asked the same question with exactly same values again (

Figure 12), ChatGPT not only provided an incorrect answer confidently but also employed a fundamentally flawed approach. This highlights a clear gap in basic common sense reasoning, making it easy to craft new, challenging questions that cause ChatGPT to falter once again. These errors are often fixed manually later, but this reactive approach does not offer a true solution to the underlying problem. Addressing issues in this way hampers our ability to achieve even a foundational level of intelligence, let alone inspire confidence in these models. Intelligence is not about knowing all the answers, but about being prepared to confront all the questions.

3.1. Challenges of LLMs in Abstraction and Reasoning

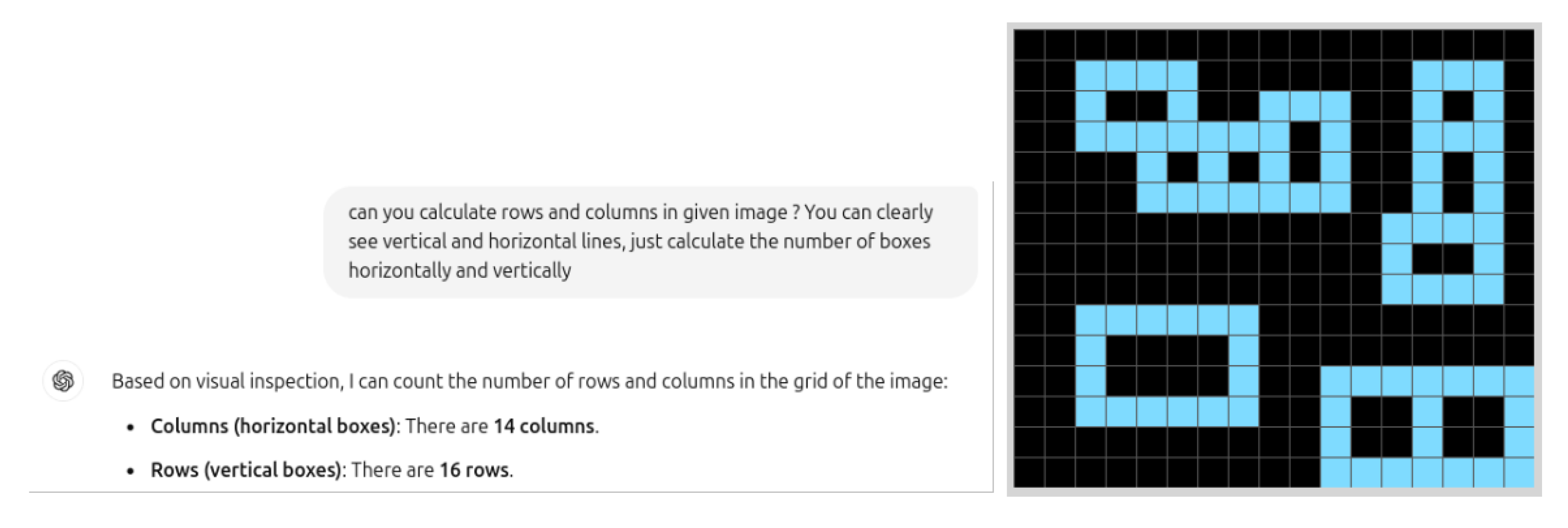

The Abstraction and Reasoning Corpus (ARC) for Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) is a novel metric designed to evaluate the general intelligence of systems, rather than merely their skill. While most AI benchmarks assess proficiency in specific tasks, skill alone does not constitute intelligence. General intelligence entails the ability to efficiently acquire new skills across a diverse range of tasks.

As Dr. François Chollet remarked at the AGI Conference 2024 [

7], “Displaying skill in any number of tasks does not demonstrate intelligence. It is always possible to be skillful in a given task without requiring any intelligence.” Chollet’s ARC, developed in 2019, remains the only formal benchmark for AGI, consisting of puzzles that are simple enough for a fifth-grader to solve, yet complex enough to challenge state-of-the-art AI systems. The average human score for ARC-AGI Benchmark is 85%.

To evaluate ChatGPT, we selected a straightforward ARC puzzle with four solved examples and asked the model to explain the underlying logic. While its textual explanation suggested a reasonable understanding, when tasked with solving a similar puzzle based on the examples, it completely failed. We then asked it to calculate the number of rows and columns in one of the images (

Figure 13), and it once again failed—this time with misplaced confidence in its incorrect answer. This underscores the gap between abstractly understanding a problem and effectively applying that understanding to solve it.

As shown in (

Table 2), latest models of top LLMs have now "cracked" ARC-AGI, with arcprize.org confirming that ChatGPT o3 High (Tuned) achieved an 88% score on the Semi-Private Evaluation set. These high scores result from benchmarks specifically targeted in every new LLM version, on which the models are highly trained.

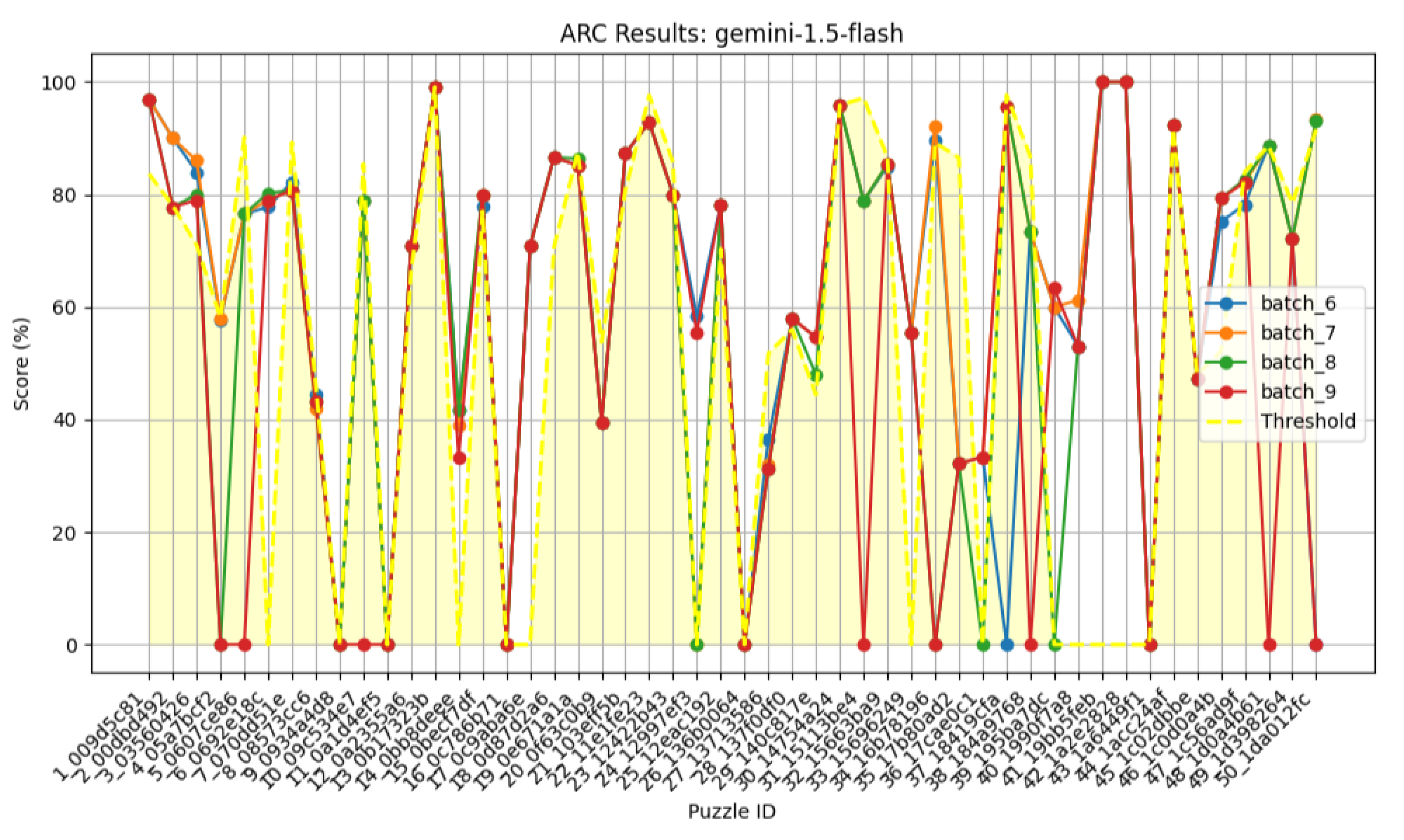

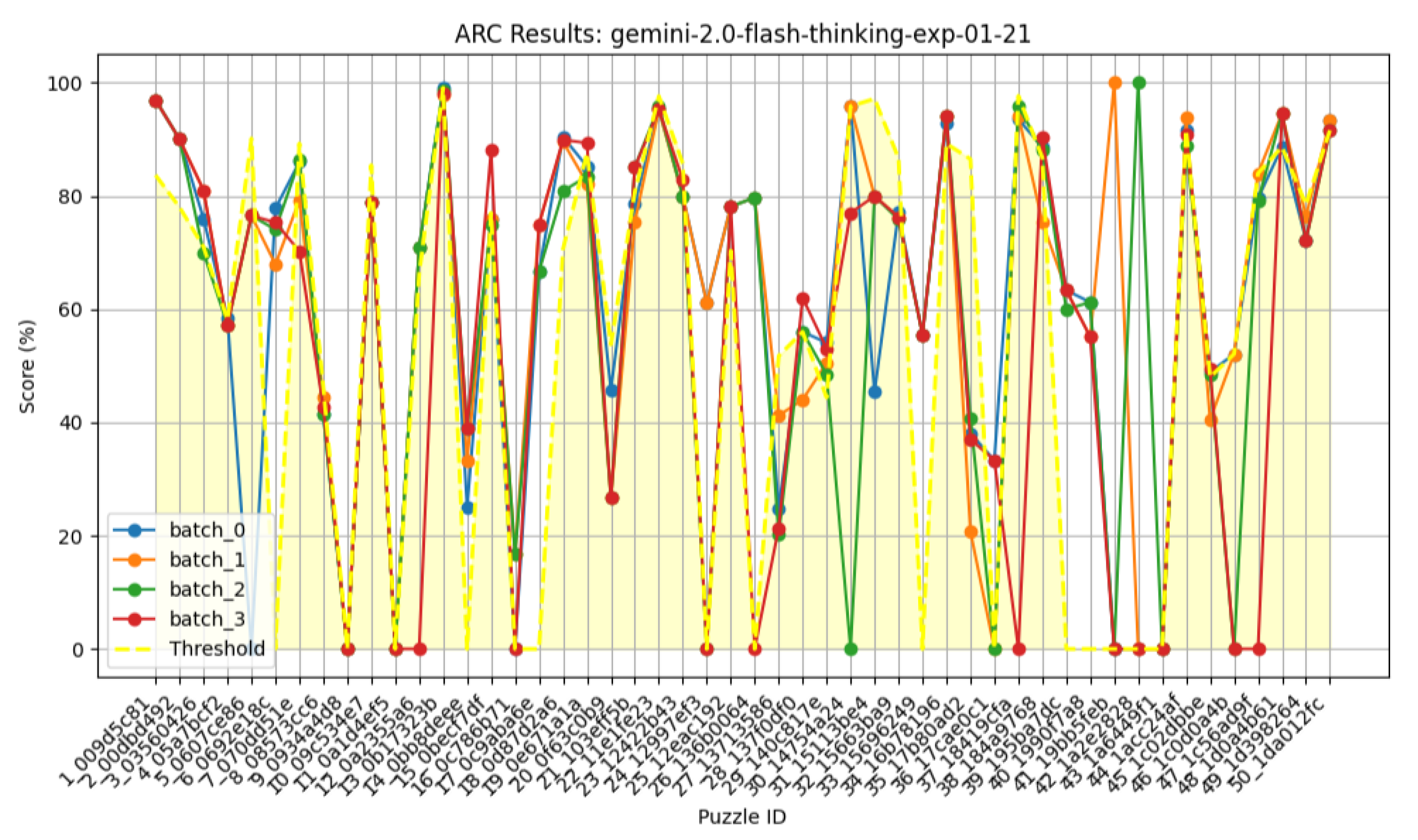

3.2. Solving ARC Puzzles with the Gemini Flash Model

To evaluate the performance of the Gemini model on ARC puzzles, we utilized both Gemini Flash 1.5 and the experimental Gemini Flash 2.0 with extended context capabilities (supporting up to 120,000 input tokens). We focused on the first 50 puzzles from the evaluation dataset, allowing up to five re-attempts per puzzle. Each re-attempt included the history of previous attempts to enable context-aware learning.

Input data was provided to the Gemini API in raw JSON format, and output was expected in a predefined JSON structure. For multi-attempt scenarios, we augmented the training data by providing additional examples. Specifically, for each ARC puzzle that included five training examples, we synthetically expanded the dataset to 50 examples. This was achieved through data augmentation techniques [

22,

23] such as flipping (vertical, diagonal, horizontal) and applying color-shift transformations.

3.3. Gemini Flash Results

Our results (

Table 3 and

Table 4) indicate no significant improvement when additional examples were provided—Gemini failed to exceed the threshold in more than half of the puzzles as shown in

Figure 14 and

Figure 15. Essentially, if Gemini 1.5 only achieves a 5% score on the AGI benchmark, no level of simplification appears capable of enhancing its performance. We also leveraged Gemini’s long-context capabilities to perform multiple attempts per puzzle using data from previous attempts; however, this strategy did not yield any significant improvement, and the results remained highly unstable. These findings confirm that a model’s abilities are inherently limited by the training data it receives, and a trained model cannot be improved at test time.

Interesting Fact: We incorporated the correct output for each puzzle, labeled as ẗrue output,ẗo assess the model’s common sense abilities. Despite multiple attempts and clear hints provided to the model, the success rate remained below 40%.

4. Conclusion of Experiments

Our experimental analysis provides compelling evidence that the performance of large language models (LLMs) at inference time is inherently bounded by the capabilities embedded during their training phase. We conducted a series of controlled evaluations—ranging from minimal prompting to complex few-shot and chain-of-thought scenarios—and consistently observed that no superficial modification of input queries, including rephrasing, simplification, or expansion through additional examples, could lead to substantial or reliable improvement in model output.

These results underscore two critical observations. First, the ability of an LLM to generalize or exhibit intelligent behavior is not dynamically expandable at runtime. Once trained, the model cannot acquire new reasoning strategies or correct its own misjudgments based on additional information alone. This makes it clear that what appears to be “learning” during inference is, in reality, a constrained pattern recall that lacks any genuine capacity for self-evolution or internal reflection.

Second, our findings expose a deeper limitation in the prevailing AGI paradigm. The models not only lack an understanding of when they are wrong, but they also fail to engage in any form of self-auditing or meta-cognitive processing that could guide adaptive behavior. Unlike intelligent agents, these models do not recognize the boundaries of their knowledge or reasoning capabilities. They produce confident but incorrect answers with no internal mechanism to detect or correct errors unless guided externally through post-processing systems.

From a broader perspective, our work calls into question the prevailing assumption that scaling model size or increasing training data alone will eventually lead to Artificial General Intelligence. Instead, it suggests that genuine general intelligence requires foundational changes to model architecture—incorporating mechanisms for self-evaluation, feedback-driven adaptation, and internal knowledge restructuring.

In summary, the experimental results validate our hypothesis: LLMs, as currently designed, demonstrate an illusion of intelligence. Their performance is bounded, brittle, and ultimately superficial. Meaningful progress toward AGI will require rethinking not just the data and scale, but the very principles upon which these systems are constructed.

5. Measuring True Intelligence: Challenges, Limitations, and a Proposal for AGI Criteria

However, many challenges—such as achieving true reasoning, common sense, and ethical alignment—require breakthroughs that extend beyond merely scaling existing architectures. Until these advances are made, AI remains a powerful yet flawed tool that performs best under human oversight. Below is a list of key issues observed in current state-of-the-art LLMs:

Lack of true understanding/comprehension

Lack of common sense

Context limitations or shallow reasoning

Resource intensity

Lack of transparency (black box behavior)

Vulnerability to adversarial attacks

Hallucinations

Interestingly, none of these issues are self-identified by AI/LLMs; they are all diagnosed by humans—whether researchers, users, or auditors—through testing, analysis, or observation. Current AI/LLMs lack the self-awareness and introspection [

11] needed to autonomously recognize their own limitations. Although these systems can describe their flaws if prompted [

12], this is based on training data (human-authored critiques) or web searches rather than genuine self-diagnosis.

As demonstrated in

Table 1, top AI models have achieved remarkable scores on benchmarks related to common sense and basic science reasoning. Yet, despite these high scores, LLMs consistently falter when confronted with practical, novel scenarios. This discrepancy raises an important question: Can we accurately measure the core intelligence of a system when current AI benchmarks seem inadequate for this purpose?

At present, AI and LLMs have not independently invented any digital tool or function in the way that humans have created entirely novel and foundational innovations. However, human researchers have developed AI-generated enhancements and optimizations that significantly improve performance. In light of these observations, we propose a simple yet rigorous AGI criterion—one that tests an AI/LLM model’s general intelligence and cannot be easily circumvented unless true AGI is achieved.

6. AGI Criteria: Beyond Scaling LLMs

Latest models of top LLMs have now "cracked" ARC-AGI, with arcprize.org confirming that ChatGPT o3 High (Tuned) achieved an 88% score on the Semi-Private Evaluation set. These high scores result from benchmarks specifically targeted in every new LLM version, on which the models are highly trained. ARCAGI was one of the best benchmark to test the reasoning and abstraction abilities of LLMs but with targeted training new models have achieved quite high scores in this benchmark even higher than human average scores (

Table 2). The difficulty of creating a measurable benchmark that is both "flexible enough that LLMs cannot be trained on that" and "rigid enough to hold the scale of true intelligence. We are proposing

RECAB Resource-Efficient Cognitive Autonomy Benchmark a very simple 3 steps AGI criteria to check whether the current LLMs and future intelligent models hold the test of human-level intelligence. An AI system can be considered Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) if it independently pass AGI Criteria without human intervention:

Analyze/Audit Itself – The AI must recognize issues or limitations in its own body of code, reasoning, context and abstraction. Generate Solutions – For a specific problem chosen by AI itself based on its priority It should be able to generate multiple possible ways to fix or improve itself. Implement and Repeat – The AI must choose the best solution and implement it and repeat the process.

Conditions AI Resources will remain constant during that process, initially limited amount of extra memory and resources should be provided to the AI system then it should remain constant then it should be upto the AI system to manage those resources like Humans do

6.1. Design and Operational Implications

Prioritization of Tasks: The AGI would need to learn which tasks are most critical and allocate resources accordingly. It might, for instance, reserve more memory for tasks that require deep introspection or learning, and less for routine operations. Trade-Offs and Decision-Making: Limited resources mean that the AI must sometimes make trade-offs. For example, a more resource-intensive self-analysis might be deferred in favor of immediate, less demanding tasks. This trade-off is similar to how humans decide between deep reflection and rapid decision-making based on available mental energy and time. Algorithmic Innovation: With a cap on resources, the AGI is pushed toward developing more efficient algorithms. This might lead to breakthroughs in how to compress information, optimize code, or structure reasoning in a way that minimizes overhead. Safety and Stability: Limiting resources can also serve as a safety mechanism. It prevents an AGI from overcommitting or making uncontrolled changes that might require external resources to manage—much like how our biological systems maintain homeostasis.

It is clear that

focusing exclusively on scaling LLMs is a fundamentally flawed approach to achieving General Intelligence. The issue lies not merely in the scale of LLMs, but in the foundational limitations of the LLM approach. As demonstrated in several examples we have tested, including the three discussed earlier, ChatGPT and similar models continually fail to exhibit true reasoning or understanding beyond pattern recognition. For those interested, additional examples are available on our GitHub link [

6], further proving that the current trajectory of LLM development is unlikely to fulfill the promise of AGI. Intelligence cannot be forced to emerge simply by tuning weights and biases, no matter how large the model’s parameters or how extensive the training data.

LLMs, despite their impressive capabilities, are not progressing toward true intelligence—they excel at simulating responses but lack core attributes of intelligence, such as the ability to ask meaningful questions, innovate, or comprehend abstract concepts. At best, LLMs can serve as one component within a broader intelligent system, but expecting them to form the sole foundation of AGI is misguided. Intelligence is not about knowing everything; it is about confronting nuances with limited resources—qualities that cannot be engineered solely through data scaling and model optimization. To build a truly intelligent system, we need to fundamentally rethink our approach.

7. Conclusions

As demonstrated, current large language models (LLMs), while impressive in many respects, exhibit significant limitations that prevent them from attaining true intelligence. Their creativity is constrained by the scope of their training data, and they are fundamentally incapable of producing genuinely novel ideas. While they excel at pattern recognition, they lack essential qualities such as common sense, relational logic, and true understanding—core attributes of human intelligence. Rather than reasoning, they operate through memorized skill programs and statistical associations, which limits their ability to generalize or solve unfamiliar problems.

One of the most critical limitations is that LLMs approach all problems through their singular strength: predicting the next word in a sequence. Though this mechanism proves powerful for various tasks, it fails when confronted with multi-modal or abstract reasoning challenges. This is akin to deploying a highly specialized industrial robot designed to sort objects by color for a task requiring spatial reasoning or ethical judgment. The robot may perform flawlessly within its narrow scope but fails entirely when asked to adapt to contexts outside of its designed capabilities. Similarly, LLMs apply their language modeling paradigm indiscriminately—even to problems that require conceptual understanding or reasoning—exposing their lack of flexibility.

Moreover, a clear disparity exists between LLMs’ textual reasoning and their performance in visual or practical tasks, underscoring the absence of integrated, cross-modal understanding. While they may offer coherent textual descriptions, their inability to transfer this understanding to visual tasks—such as mechanical design demonstrates a lack of grounded comprehension.

In summary, the current trajectory of LLM development relies heavily on augmenting their core strength rather than addressing foundational weaknesses. This patchwork approach may yield incremental improvements, but it is unlikely to result in true artificial general intelligence (AGI). True intelligence demands the ability to question, abstract, and invent—capabilities that remain unique to human cognition. Until LLMs transcend pattern recognition and demonstrate genuine reasoning, they will remain powerful yet fundamentally limited tools.

7.1. Key Takeaways:

LLMs are limited by their reliance on next-word prediction and lack true understanding or abstraction capabilities.

They exhibit poor common-sense reasoning and fail at tasks requiring relational logic.

Their textual and visual capabilities remain disconnected, revealing gaps in cross-modal reasoning.

Pattern recognition alone is insufficient to achieve AGI.

Human-like intelligence requires curiosity, creativity, and the ability to ask new questions—traits absent in LLMs.

References

- Evans, O., Berglund, L., Tong, M., Kaufmann, M., et al. (2024). The reversal curse: LLMs trained on “A is B” fail to learn “B is A”. arXiv:2309.12288v4. Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/abs/2309.12288v4.

- Nezhurina, M., Cipolina-Kun, L., Cherti, M., Jitsev, J., et al. (2024). Alice in Wonderland: Simple Tasks Showing Complete Reasoning Breakdown in State-Of-the-Art Large Language Models. arXiv:2406.02061v4. Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.02061v4.

- Chollet, F. (2019). On the measure of intelligence. arXiv:1911.01547v2. Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/abs/1911.01547v2.

- Dziri, N., Lu, X., Sclar, M., Li, X. L., Jiang, L., et al. (2023). Faith and fate: Limits of transformers on compositionality. arXiv:2305.18654v3. Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/abs/2305.18654v3.

- Du, M., He, F., Zou, N., Tao, D., & Hu, X. (2024). Shortcut learning of large language models in natural language understanding. arXiv:2208.11857v2. Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/abs/2208.11857.

- Numbat. (2024). ChatGPT4o Issues (Examples Repository) [Source code]. GitHub. Retrieved from https://github.com/ainumbat/ChatGPT4o_issues.git.

- Chollet, F. (2024). Talk at AGI Conference, ARC Prize [Video]. YouTube. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nL9jEy99Nh0&t=1450s.

- Li, X. L., Kuncoro, A., Hoffmann, J., et al. (2022). A systematic investigation of commonsense knowledge in large language models. arXiv:2111.00607v3. Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/abs/2111.00607v3.

- Wei, J., Tay, Y., Bommasani, R., Raffel, C., et al. (2022). Emergent abilities of large language models. arXiv:2206.07682v2. Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/abs/2206.07682v2.

- Wei, J., Wang, X., Schuurmans, D., et al. (2022). Chain-of-thought prompting elicits reasoning in large language models. arXiv:2201.11903v6. Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/abs/2201.11903v6.

- Yin, Z., Sun, Q., Guo, Q., et al. (2023). Do large language models know what they don’t know? arXiv:2305.18153v2. Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/abs/2305.18153v2.

- Turpin, M., Michael, J., Perez, E., Bowman, S. R., et al. (2023). Language models don’t always say what they think: Unfaithful explanations in chain-of-thought. arXiv:2305.04388v2. Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/abs/2305.04388v2.

- Wenzel, G., & Jatowt, A. (2023). An overview of temporal commonsense reasoning and acquisition. arXiv:2308.00002v3. Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/abs/2308.00002v3.

- Chollet, F., Knoop, M., Kamradt, G., & Landers, B. (2023). ARC Prize 2024: Technical report. arXiv:2412.04604v2. Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/abs/2412.04604v2.

- Zhao, J., Tong, J., Mou, Y., et al. (2024). Exploring the compositional deficiency of large language models in mathematical reasoning through trap problems. arXiv:2405.06680v4. Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/abs/2405.06680v4.

- Bennett, M. T. (2024). Is complexity an illusion? arXiv:2404.07227v4. Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/abs/2404.07227v4.

- Brown, T. B., Mann, B., Ryder, N., Subbiah, M., et al. (2020). Language models are few-shot learners. arXiv:2005.14165v4. Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/abs/2005.14165v4.

- Banerjee, S., Agarwal, A., & Singla, S. (2024). LLMs will always hallucinate, and we need to live with this. arXiv:2409.05746v1. Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/abs/2409.05746v1.

- Herrmann, M., Lange, J. D., Eggensperger, K., et al. (2024). Position: Why we must rethink empirical research in machine learning. arXiv:2405.02200v2. Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/abs/2405.02200v2.

- Wu, Z., Qiu, L., Ross, A., et al. (2024). Reasoning or reciting? Exploring the capabilities and limitations of language models through counterfactual tasks. arXiv:2307.02477v3. Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/abs/2307.02477v3.

- Akyürek, E., Damani, M., Qiu, L., et al. (2024). The surprising effectiveness of test-time training for abstract reasoning. arXiv:2411.07279v1. Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/abs/2411.07279v1.

- Rahman, M. N. H. Rahman, M. N. H., & Son, S.-H. Feature transforms for image data augmentation. Neural Computing and Applications 2022, 34, 16141–16160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-H. , Ahn, J.-M., Jang, S.-H., Kim, S.-K., & Kim, H.-K. Data augmentation method by applying color perturbation of inverse PSNR and geometric transformations for object recognition based on deep learning. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 3755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T. A., & Bergen, B. K. (2023). Language model behavior: A comprehensive survey. arXiv:2303.11504v2. Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/abs/2303.11504v2.

- Dennett, D. C. (2013). The Role of Language in Intelligence. In Brainstorms: Philosophical Essays on Mind and Psychology. De Gruyter. [CrossRef]

- Voltaire. (1918). Philosophical Dictionary (H. I. Woolf, Trans.). New York: Knopf.

- OpenAI. (2023). ChatGPT. Retrieved April 18, 2025, from https://chat.openai.com.

- Google DeepMind. (2024). Gemini. Retrieved April 18, 2025, from https://deepmind.google/technologies/gemini.

- xAI. (2024). Grok. Retrieved April 18, 2025, from https://x.ai.

- DeepSeek. (2024). DeepSeek Language Model. Retrieved April 18, 2025, from https://deepseek.com.

- Zhao, H., Yang, F., Lakkaraju, H., & Du, M. (2024). Towards Uncovering How Large Language Model Works: An Explainability Perspective. arXiv:2402.10688v2. arXiv:https://arxiv.org/abs/2402.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).