1. Introduction

Liver cirrhosis is a significant global public health issue, ranked as the eleventh leading cause of mortality, resulting in approximately 1 million deaths annually. It compromises typical liver architecture, histologically characterized by fibrosis and nodular regeneration [

1]. Approximately 90% of patients with hepatic cirrhosis develop portal hypertension, which is a primary cause of mortality in patients with liver diseases. In this context, the identification and management of clinically significant portal hypertension (CSPH) hold paramount importance in preventing the risk of hepatic decompensation and improving the quality of life of cirrhotic patients [

2]. The onset of CSPH not only increases the risk of complications such as ascites, variceal bleeding, and hepatic encephalopathy but also predisposes to the development of portal hypertensive gastropathy (PHG) and portal hypertensive polyps (PHPs), further compromising the prognosis of cirrhotic patients [

3,

4]. PHG prevalence in cirrhotic patients ranges from 20% to 98%, increasing with the severity of the disease [

5]. It is associated with portal hypertension, which leads to increased blood flow in the gastric mucosa, resulting in inflammation and susceptibility to damage, such as erosion and ulceration. Typically, it is asymptomatic, but in more severe forms, it is associated with gastrointestinal bleeding and anemia. On the other hand, PHPs are polyps of the upper gastrointestinal tract that arise from the proliferation of vessels within the gastric wall. Their prevalence in cirrhotic patients is between 0.9% and 2.2%, although one study indicates a prevalence of 33.5% [

6]. They do not exhibit malignant characteristics and are generally asymptomatic; however, they may bleed and cause anemia. Furthermore, there is a documented case in the literature of pyloric obstruction mediated by PHPs [

7].

In this context, beta-blockers, particularly carvedilol, effectively treat CSPH by reducing splanchnic vasodilation and cardiac output [

8]. An alternative to beta-blockers for managing variceal bleeding is endoscopic band ligation (EBL), which, while effective in preventing variceal bleeding, presents challenges due to the lack of action on portal hypertension and the possible development of upper gastrointestinal complications like PHG and PHPs [

9].

The aim of the present study is to evaluate the changes in PHG, PHPs, and gastric varices evaluated by upper endoscopy before and after the obliteration of esophageal varices, thus seeking to provide a comprehensive understanding of disease progression.

2. Materials and Methods

This retrospective study, performed in a tertiary care center hospital between January 2022 and July 2024, enrolled forty-four patients diagnosed with cirrhosis resulting from various etiologies. Following the Baveno VII guidelines, the patients underwent EBL of esophageal varices in emergency or elective settings [

3]. The exclusion criteria were previous variceal ligation, splenectomy, and portal thrombosis.

The patients’ clinical, laboratory, and instrumental data were collected. In particular, complications like ascites, hepatocarcinoma, and thrombosis in the spleno-portal-mesenteric axis were evaluated using ultrasound, while encephalopathy was assessed according to the West Haven criteria [

8]. Additionally, the degree of fibrosis was evaluated using the APRI and FIB-4 scores. Finally, the CHILD-PUGH and MELD scores were calculated for each patient.

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) was carried out using an Olympus GIF 160 video endoscope. Before the procedure, patients were given premedication, which consisted of topical anesthesia in the throat using lidocaine spray and intravenous sedation with midazolam. Esophageal varices were categorized using the Japanese Research Society for Portal Hypertension (JRSPH) criteria, while gastric varices were classified using the Sarin classification system. The presence of PHG was classified based on the Baveno III, NIEC, and McCormack criteria [

3,

8,

9]. Additionally, both evaluated the number and size of PHPs.

Ligation was performed by placing multiple rubber bands (Saeed’s multiband ligator, Wilson’s Cook) on the varices, starting from the gastroesophageal junction and proceeding helically for approximately 5-8 cm. Endoscopic ligations were repeated every 3-4 weeks until variceal eradication was achieved, defined as complete obliteration or reduction to grade 1 size, according to JRSPH criteria. Upon eradicating esophageal varices, we reevaluated the presence and severity of PHG, the status of gastric varices, and the number of PHPs.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) if normally distributed and as median with interquartile range (IQR) otherwise. Categorical data are shown as frequencies and percentages. Statistical analysis was conducted to evaluate differences between endoscopic characteristics pre and post EBL. The Kruskal–Wallis, with post-hoc pairwise test (Bonferroni correction), the Mann–Whitney U test, or the Chi-squared test were used to perform the analysis between groups and within groups, as appropriate. In addition, univariate binary logistic regression was performed in order to determine the variables associated with PHG worsening. Then, statistically significant variables in the univariate analysis were included in a multivariable logistic regression model to define independent risk factors. Logistic regression results are presented as odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI). Analysis was performed using IBM SPSS® Statistics (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA), Version 26; p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

Forty-four patients were enrolled, including n.36 (82%) males and n.8 (18%) females, with a mean age of 64±12 years (

Table 1). All the patients described presented liver cirrhosis, with a viral etiology in 21% (n.9) of the patients, alcohol in 43% (n.19), and metabolic in 36% (n.16), respectively. The mean range of disease duration was 4±5 years. Regarding metabolic comorbidities, fifteen patients (34%) had type 2 diabetes mellitus and eighteen (41%) had arterial hypertension. At baseline, the mean MELD score of the patients was 15±6, and the Child-Pugh score was A in eighteen (41%), B in twenty (45%), and C in six (14%) patients. The APRI and FIB-4 scores were >1 and >3.25, respectively, in all patients. Concerning complications of liver cirrhosis, eighteen patients (41%) had ascites at the time of the initial EGD, although no evidence of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis or hepatorenal syndrome was observed. Additionally, eight patients (18%) showed radiological evidence of hepatocellular carcinoma. All patients exhibited minimal hepatic encephalopathy, but none showed signs of spatial-temporal disorientation.

The first EBL procedure was performed in emergency (due to upper gastrointestinal bleeding from esophageal varices) in sixteen patients (36%), and electively (following evidence of F3 varices with red signs per the JRSPH classification during a follow-up EGD) in twenty-eight patients (64%). In total, twenty-two patients (50%) were already receiving beta-blocker treatment before the first EBL; of these, twelve patients (27%) were on pharmacological treatment before the elective procedure, and ten patients (23%) were before the emergency procedure. Specifically, 75% of patients undergoing elective ligation were already taking beta-blockers, whereas only 35% of those undergoing emergency ligation were taking such treatment; this statistically significant difference (p-value 0.012) highlights beta-blockers' effectiveness in preventing variceal bleeding.

At the baseline EGD, twenty-six patients (59%) showed evidence of PHG, while eighteen (41%) did not present endoscopic signs of PHG. Among the patients with PHG at baseline, nineteen (73%) had a mild form according to the Baveno III, NIEC, and McCormack systems, while seven (27%) had a severe form. The correlation between baseline clinical and endoscopic characteristics and the presence of PHG was evaluated, finding that the presence of ascites correlates with the presence of PHG at baseline (

p-value 0.036) in a statistically significant manner. The correlation with other baseline clinical and endoscopic variables did not reach statistical significance. For example, in patients with PHG, the FIB-4 value was higher than in patients without PHG (with values of 11±8 and 8±9, respectively). However, this difference was not statistically significant (

Table 2).

Regarding gastric varices, at baseline EGD, three patients (7%) had gastric varices, all of type 2 gastroesophageal varices (GOV2). Of these three patients, all had a viral etiology. One (33%) was already on beta-blockers, and none showed the presence of ascites, PHG, or PHPs. Finally, all three underwent emergency EBL. At baseline EGD, two patients (5%) presented with PHPs: the first had two polyps measuring 10 and 6 mm, the second had multiple polyps, and the biggest measuring 15 mm. The etiology was viral in one patient and metabolic in the other. Both patients were on beta-blockers at baseline, and neither had ascites. PHG was also present and classified as mild in one of the two cases, while neither had gastric varices. Both underwent EBL for prophylaxis.

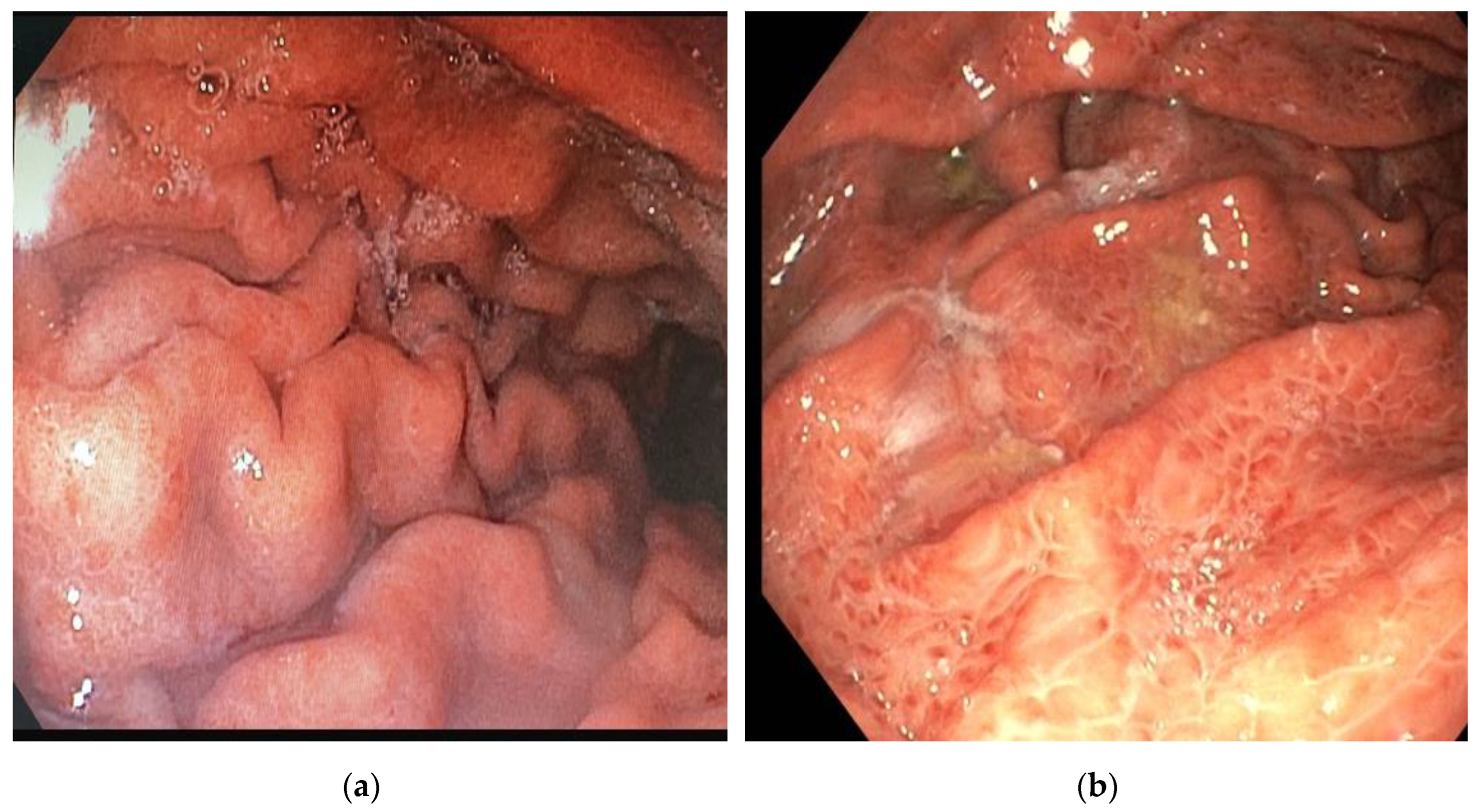

At the last upper endoscopic control, after an average observation period of 4.8 months and following the successful eradication of varices with a variable number of subsequent sessions ranging from 0 to 3, the clinical and endoscopic variables of the patients were re-evaluated, and a comparison was made between the variables at T0 and T1. Regarding the endoscopic variables, at T0, PHG was present in twenty-six patients (59%), while at T1, PHG was observed in forty-two patients (95%) (p < 0.05). Specifically, PHG worsened from mild to severe in twenty-eight patients (63%) (

Figure 1), remained stable in fourteen patients (31%), and improved in two patients (4.5%).

Subsequently, the correlation between other baseline clinical, laboratory, and endoscopic variables and the worsening of PHG at T1 was evaluated (

Table 3). Among the factors examined, the use of beta-blockers and the presence of ascites at T0 were found to be protective factors against the worsening of PHG, with odds ratios (OR) of 3.4 (CI 0.9-12.5, p-value 0.048) and 4.2 (CI: 1.1-15.3; p-value 0.036), respectively. However, upon analyzing the baseline clinical and endoscopic characteristics, it was noted that patients with ascites already had a severe degree of PHG at T0; therefore, the stability of PHG at control EGD resulted in a skewed calculation of the OR.

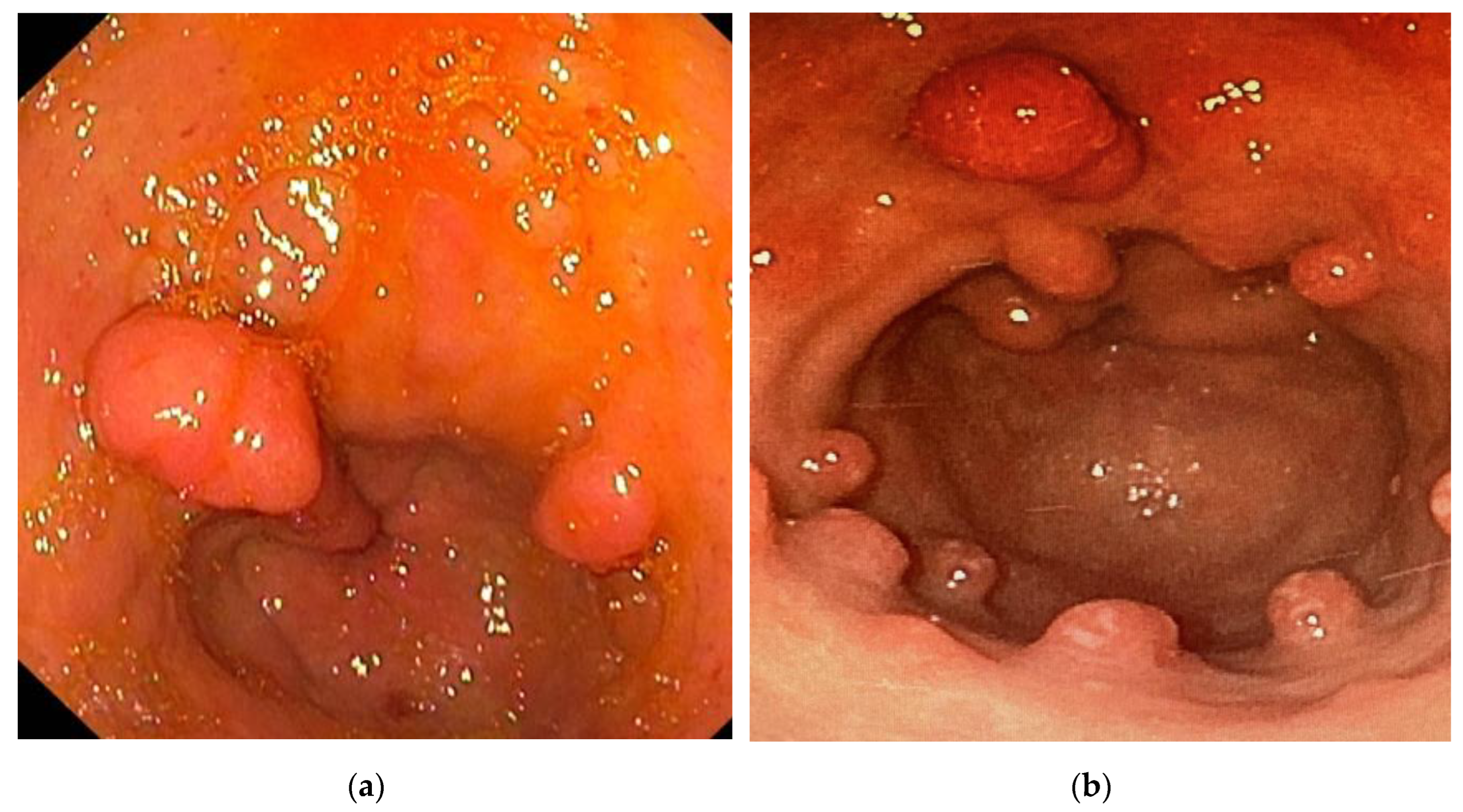

On the other hand, regarding other gastric consequences of portal hypertension following the EBL procedure, the formation of gastric varices was recorded in 2 patients, all of type GOV2; both subjects exhibited a worsening of PHG at T1, and PHPs were identified in one of the two. At T0, neither patient was taking beta-blockers, and one of them had ascites. Finally, one of the patients had a metabolic etiology, while the other was affected by viral cirrhosis. The presence of PHPs was observed in three patients at T1. In one of these patients, the number of polyps increased compared to baseline; in one, it remained stable, while in the third, no gastric polyps were present at T0 (

Figure 2). In patients with increased polyps, beta-blocker use was already present at T0, PHG showed no signs of worsening at T1, and gastric varices did not form at T1. In the patient with a polyp only found at T1, there was no history of beta-blocker use at T0, PHG worsened at T1, and gastric varices formed at T1. Lastly, both patients at T0 did not have ascites, and the etiology of their liver cirrhosis was metabolic.

4. Discussion

The management of primary prophylaxis of esophageal variceal bleeding in liver cirrhotic patients remains a currently debated topic. According to current guidelines, beta-blockers, particularly carvedilol, are considered first-line agents for preventing decompensation in patients with esophageal or gastric varices and/or CSPH [

3]. These medications aim to reduce portal hypertension and to prevent variceal bleeding, and to reduce the risk of the onset of other cirrhotic complications, such as ascites and hepatic encephalopathy [

2]. However, in patients with intolerance or contraindications to beta-blocker administration, and with high-risk varices (e.g., grade F2 or F3 or with red signs), EBL represents a valid option to prevent variceal bleeding [

3]. In this context, the therapeutic management of patients with ascites undergoes certain modifications. Specifically, in patients with ascites and high-risk varices, beta-blockers are considered a first-line therapy alongside EBL [

8]. Therefore, the choice between beta-blockers and EBL in this population depends on the referral center’s expertise and the patient’s overall clinical condition [

8]. The different therapeutic approaches between ascitic and non-ascitic patients are based on the hypothesis that beta-blockers may induce, particularly in the setting of decompensation, systemic hypotension and a reduction in cardiac reserve [

10]. This condition could potentially impair hemodynamic function and exacerbate the clinical status of the ascitic patient. However, this theory is challenged by study findings demonstrating a protective effect of beta-blockers even in patients with ascites [

11,

12]. Conversely, EBL acts exclusively on esophageal varices and may have potential negative effects on other gastric complications related to portal hypertension, including PHG, gastric varices, and PHPs [

13,

14,

15].

The prevalence of PHG in cirrhotic patients ranges from 20% to 98% and increases with the severity of the disease [

5]. It is linked to portal hypertension, which causes increased blood flow to the gastric mucosa, leading to inflammation and vulnerability to injury, such as erosions and ulcers. Typically, asymptomatic, severe cases tend to be associated with gastrointestinal bleeding and anemia. Various studies showed the correlation between EBL and the development or worsening of PHG. The exacerbation of PHG following the obliteration of esophageal varices may be related to changes in gastric hemodynamics caused by the sudden and significant blockage of blood flow in the involved vessels [

16,

17]. In a prospective study of 50 cirrhotic patients, mild and severe PHG were present in 74% and 22% of cases, respectively. Four weeks after variceal eradication, 38% exhibited mild PHG and 62% severe [

13]. In a randomized clinical trial, PHG was found in 17% of patients before EBL and 85% after six months. Lo et al. suggested that using beta-blockers in combination with EBL could improve outcomes [

15]. In a retrospective study, PHG was absent, mild, and severe in 31.8%, 32.9%, and 35.3% of cases, respectively; after EBL, mild and severe PHG increased to 35.3% and 48.2% [

18]. Lahbabi

et al. highlighted the efficacy of EBL in eradicating varices and its association with the development of PHG [

19]. Hou et al. observed a worsening of PHG in 17 out of 30 patients after EBL, but this change was temporary. A prolonged follow-up of approximately 18 months showed that, in most cases, PHG returned to baseline levels [

20].

Our study confirmed these findings. The worsening of PHG following EBL was statistically significant. At T1, in 63% of patients, PHG had worsened, 31% had remained stable, and in 4.5% it had improved. It is important to note that patients whose PHG remained stable had severe-stage PHG at T0, and thus, any subsequent worsening could not be quantifiable using the available endoscopic criteria. To explain these results, Kanke et al. analyzed changes in gastric mucosal hemodynamics after EBL using reflectance spectrophotometry. This study highlighted that EBL causes increased mucosal congestion, decreased hemoglobin saturation, and increased gastric blood volume. However, not all patients exhibited exacerbation of PHG after EBL, likely due to varying hemodynamic dynamics of esophagogastric flow [

21]. Indeed, in some patients, venous drainage from the esophagogastric junction occurs in a caudal direction; therefore, blocking flow at this level may contribute to reducing gastric congestion. Furthermore, portal venous hemodynamics and portal venous pressure also depend on the type of extrahepatic collaterals present [

22,

23]. This may explain the improvement in PHG observed in 4.5% of patients treated with EBL in our study. Additionally, our study analyzed the correlation between clinical/endoscopic variables and the worsening of PHG at T1. Among the factors examined, the use of beta-blockers and the presence of ascites at T0 emerged as protective factors against the deterioration of PHG, with an OR of 3.4 (95% CI 0.9-12.5, p-value 0.048) and 4.2 (95% CI: 1.1-15.3; p-value 0.036), respectively. Also, patients with ascites already exhibited maximum severity of PHG at T0, and consequently, using the available endoscopic criteria, it is not possible to assess worsening at T1. For this reason, ascites may falsely appear as a protective factor against the development and deterioration of PHG. In contrast, the protective effect of beta-blockers on portal hypertension and its complications is confirmed. Several studies indicate that EBL is associated with the development of gastric varices. Still, no significant hemorrhages have been recorded in monitored patients, suggesting that EBL does not impact overall prognosis [

14,

15,

18,

19]. Our study confirmed these results. In addition to the worsening of PHG, an association between EBL and the development of gastric varices was observed. Indeed, in 5% of patients, gastric varices developed, all the GOV2 type, but none experienced bleeding.

Another complication of portal hypertension in the upper digestive tract is represented by PHPs, which are polyps of the upper gastrointestinal tract arising from the proliferation of vessels within the gastric wall [

24,

25]. Their prevalence in cirrhotic patients ranges from 0.9% to 2.2%, although one study reports a prevalence of 33.5% [

6]. PHPs do not have malignant characteristics and are typically asymptomatic; however, they can bleed and cause anemia. Additionally, there is a documented case in the literature of pyloric obstruction mediated by PHP [

7,

26]. Regarding PHPs, there are no direct studies on their number and severity before and after EBL. However, Kara et al. showed a higher prevalence of PHPs in cirrhotic patients undergoing EBL compared to untreated individuals, indicating a potential link between variceal treatment and the proliferation of gastric polyps, which warrants further investigation to clarify long-term implications [

27]. Our study highlighted the development of PHPs in 5% of patients undergoing EBL.

Our study confirms the findings reported in the literature regarding the negative impact of EBL on PHG, highlighting the protective role of beta-blockers in preventing such complications. Additionally, our data underline the association between EBL and the development of gastric varices, particularly of the GOV2 type, which did not exhibit signs of rupture during the follow-up period analyzed.

An innovative aspect identified in our study, which had not been previously described, concerns the correlation between EBL and the development of PHPs. Although these polyps are generally asymptomatic, it is essential to consider that they may be associated with clinical manifestations such as anemia and other related symptoms.

The main limitations of our study are its retrospective design and the number of analyzed patients. For this reason, prospective studies involving a larger patient cohort are necessary to better assess the real correlation between elastic ligation of esophageal varices and the development or worsening of other portal hypertension-related gastric complications. An extended follow-up period could also allow for evaluation of the impact of these complications on the prognosis of cirrhotic patients. Another limitation is the absence of diagnostic tests to quantify portal pressure and to evaluate its changes following variceal eradication. Finally, in patients who underwent emergency elastic ligation, there may have been an underestimation of baseline PHG due to massive bleeding, which could have impeded complete visualization of the underlying gastric mucosa.

5. Conclusions

Our study showed that EBL is associated with an increased incidence of gastric complications related to portal hypertension. Specifically, we observed a statistically significant increase in the degree of PHG among patients undergoing this procedure. Additionally, gastric variceal formation was identified in 5% of patients, all classified as GOV2 type. Furthermore, PHPs were adversely affected post-EBL, impacting 5% of the cohort. Conversely, using beta-blockers appeared to confer a protective effect against developing gastric complications following EBL. These findings underscore the significance of beta-blockers compared to EBL as the primary prophylactic strategy for variceal bleeding in both compensated and decompensated cirrhotic patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.L.G. and G.F (Giulia Fabiano); methodology, M.L.G. and R.S.; software, R.S.; validation, R.S., L.A. and M.V.; formal analysis, M.L.G. and R.S..; investigation, G.F (Giulia Fabiano), R.D.M., I.L., G.F (Giusi Franco). and F.R.; resources, G.F (Giulia Fabiano), R.D.M., I.L., G.F. (Giusi Franco) and F.R.; data curation, G.F (Giulia Fabiano). and M.L.G.; writing—original draft preparation, L.A. and M.L.G.; writing—review and editing, R.S. and F.L.; visualization, M.V., F.L. and L.A.; supervision, L.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of “Magna Graecia” University of Catanzaro (approval no. 14/28.01.2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was not required, as the study was conducted retrospectively.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would also like to thank Simone Scarlata for his critical review of the English language.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CSPH |

Clinically Significant Portal Hypertension |

| EGD |

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy |

| GOV2 |

Type 2 Gastroesophageal Varices |

| JRSH |

Japanese Research Society for Portal Hypertension |

| OR |

Odds Ratios |

| PHG |

Portal Hypertension Gastrophaty |

| PHPs |

Portal Hypertension Polyps |

References

- Asrani, S.K.; Devarbhavi, H.; Eaton, J.; Kamath, P.S. The burden of liver diseases in the world. J Hepatol 2019, 70:151-171. [CrossRef]

- Turco, L.; Villanueva, C.; Albillos, A.; Genescà, J.; Garcia-Pagan, J.C.; Calleja, J.L.; et al. β blockers to prevent decompensation of cirrhosis in patients with clinically significant portal hypertension (PREDESCI): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet 2019, 393:1597-1608.

- de Franchis, R.; Bosch, J.; Garcia-Tsao, G.; Reiberger, T.; Ripoll, C. Baveno VII Faculty. Baveno VII - Renewing consensus in portal hypertension. J Hepatol 2022, 76:959-974.

- Scarlata, G.G.M.; Ismaiel, A.; Gambardella, M.L.; Leucuta, D.C.; Luzza, F.; Dumitrascu D.L.; Abenavoli, L. Use of Non-Invasive Biomarkers and Clinical Scores to Predict the Complications of Liver Cirrhosis: A Bicentric Experience. Medicina (Kaunas) 2024, 12;60:1854. [CrossRef]

- Urrunaga, N.H.; Rockey, D.C. Portal hypertensive gastropathy and colopathy. Clin Liver Dis 2014, 18:389-406. [CrossRef]

- Topal, F.; Akbulut, S.; Karahan, C.; Günav, S.; Saritas Yüksel, E.; Topal, FE. Portal Hypertensive Polyps as a Gastroscopic Finding in Liver Cirrhosis. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2020, 2020:9058909.

- Seleem, W.M.; Hanafy, A.S. Management of a Portal Hypertensive Polyp: Case Report of a Rare Entity. Gastrointest Tumors 2019, 6:137-141. [CrossRef]

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of patients with decompensated cirrhosis. J Hepatol 2018, 69:406-460.

- Gambardella, M.L.; Luigiano, C.; La Torre, G.; Scarlata, G.G.M.; Luzza, F.; Abenavoli, L. Portal hypertension-associated gastric pathology: role of endoscopic banding ligation. Minerva Gastroenterol 2025. [CrossRef]

- Sersté, T.; Melot, C.; Francoz, C.; Durand, F.; Rautou, P.E.; Valla, D.; Moreau, R.; Lebrec, D. Deleterious effects of beta-blockers on survival in patients with cirrhosis and refractory ascites. Hepatology 2010, 52:1017-22. [CrossRef]

- Bossen, L.; Krag, A.; Vilstrup, H.; Watson, H.; Jepsen, P. Non-selective betablockers do not affect mortality in cirrhosis patients with ascites: Post hoc analysis of three RCTs with 1198 patients. Hepatology 2016, 63:1968–1976.

- Bang, U.C.; Benfield, T.; Hyldstrup, L.; Jensen, J.E.; Bendtsen, F. Effect of propranolol on survival in patients with decompensated cirrhosis: a nationwide study based Danish patient registers. Liver Int 2016, 36:1304–1312. [CrossRef]

- Elwakil, R.; Al Breedy, A.M.; Gabal, H.H. Effect of endoscopic variceal abliteration by band ligation on portal hypertensive gastro-duadenopathy: endoscopic and pathological study. Hepatol Int 2016, 10:965-973. [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, D.; Ferguson, J.W.; Kochar, N.; Leithead, J.A.; Therapondos, G.; McAvoy, N.C.; et al. Randomized controlled trial of carvedilol versus variceal band ligation for the prevention of the first variceal bleed. Hepatology 2009, 50:825-833. [CrossRef]

- Lo, G.H.; Lai, K.H.; Cheng, J.S.; Hsu, P.I.; Chen, T.A.; Wang, E.M.; et al. The effects of endoscopic variceal ligation and propranolol on portal hypertensive gastropathy: a prospective, controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc 2001, 53:579-84. [CrossRef]

- Elnaser, S.S.; El-Ebiary, S.; Bastawi, M.B.; Shafei, A.L.; Abd-Elhafee, A. Effect of endoscopic injection sclerotherapy and variceal ligation on development of portal hypertensive gastropathy and duodenopathy. J Egypt Soc Parasitol 2005, 35:253-64.

- McCormack, T.T.; Rose, J.D.; Smith, P.M.; Johnson, A.G. Perforating veins and blood flow in oesophageal varices. Lancet 1983, 2:1442-4. [CrossRef]

- Yüksel, O.; Köklü, S.; Arhan, M.; Yolcu, O.F.; Ertuğrul, I.; Odemiş, B.; et al. Effects of esophageal varice eradication on portal hypertensive gastropathy and fundal varices: a retrospective and comparative study. Dig Dis Sci 2006, 51:27-30. [CrossRef]

- Lahbabi, M.; Mellouki, I.; Aqodad, N.; Elabkari, M.; Elyousfi, M.; Ibrahimi, S.A.; et al. Esophageal variceal ligation in the secondary prevention of variceal bleeding: Result of long term follow-up. Pan Afr Med J 2013, 15:3. [CrossRef]

- Hou, M.C.; Lin, H.C.; Chen, C.H.; Kuo, B.I.; Perng, C.L.; Lee, F.Y.; et al. Changes in portal hypertensive gastropathy after endoscopic variceal sclerotherapy or ligation: an endoscopic observation. Gastrointest Endosc 1995, 42:139-44. [CrossRef]

- Kanke, K.; Ishida, M.; Yajima, N.; Saito, M.; Suzuki, Y.; Masuyama, H.; et al. Gastric mucosal congestion following endoscopic variceal ligation--analysis using reflectance spectrophotometry. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi 1996, 93:701-6.

- Vianna, A.; Hayes, P.C.; Moscoso, G.; Driver, M.; Portmann, B.; Westaby, D.; et al. Normal venous circulation of the gastroesophageal junction: A route to understanding varices. Gastroenterology 1987, 93:876-89.

- Yamamoto, Y.; Sezai, S.; Sakurabayashi, S.; Hirano, M.; Oka, H. Effect of hepatic collateral hemodynamics on gastric mucosal blood flow in patients with liver cirrhosis. Dig Dis Sci 1992, 37:1319-23. [CrossRef]

- Lemmers, A.; Evrard, S.; Demetter, P.; Verset, G.; Gossum, A.V.; Adler, M.; et al. Gastrointestinal polypoid lesions: a poorly known endoscopic feature of portal hypertension. United European Gastroenterol J 2014, 2:189-96. [CrossRef]

- Panackel, C.; Joshy, H.; Sebastian, B.; Thomas, R.; Mathai, S.K. Gastric antral polyps: a manifestation of portal hypertensive gastropathy. Indian J Gastroenterol 2013, 32:206-7. [CrossRef]

- Livovsky, D.M.; Pappo, O.; Skarzhinsky, G.; Peretz, A.; Turvall, E.; Ackerman, Z. Gastric Polyp Growth during Endoscopic Surveillance for Esophageal Varices or Barrett's Esophagus. Isr Med Assoc J 2016, 18:267-71.

- Kara, D.; Hüsing-Kabar, A.; Schmidt, H.; Grünewald, I.; Chandhok, G.; Maschmeier, M.; et al. Portal Hypertensive Polyposis in Advanced Liver Cirrhosis: The Unknown Entity? Can J. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018, 2018:2182784.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).