1. Introduction

As a core information extraction (IE) task, end-to-end relation extraction (E2ERE) can be split into named entity recognition (NER) subtask for entity identification and relation extraction (RE) subtask for capturing inter-entity relations from plain texts. As postulated by [

1], E2ERE is challenging for its difficulty in capturing affluent correlations between entities and relations. IE research has traditionally converted NER and RE tasks into span-based tasks [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Though these methodologies have incrementally advanced model performance from various perspectives, they are still impeded by two pivotal limitations: overdetached of sub-tasks leads to insufficient information exchange between entitiy and relation, and the disparity in modeling strategies between entity and relation result in semantic gaps. In this paper, we mainly focus on enhancing semantic interaction during modeling process to achieve enhanced span representation for E2ERE.

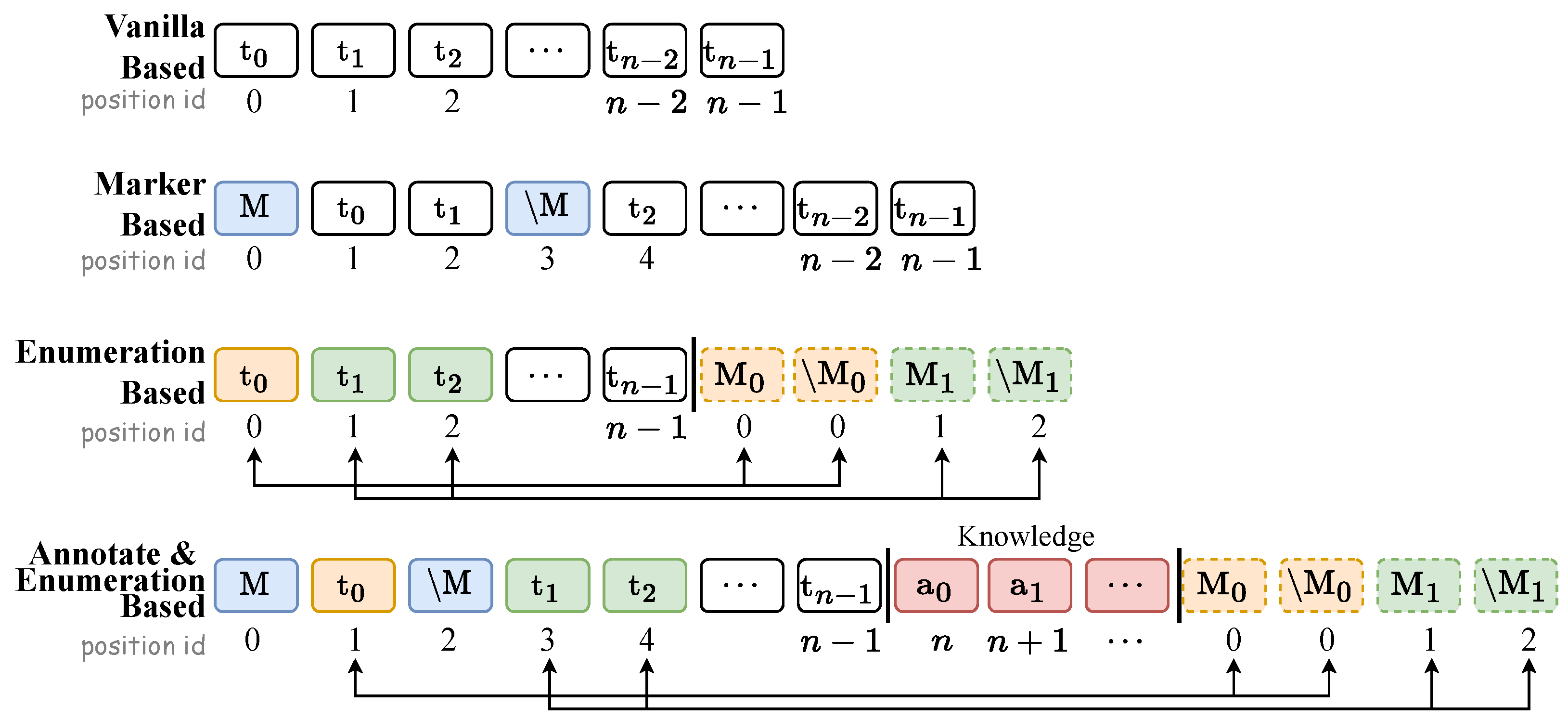

To address the challenges above, prevailing researches mainly focuses on reorganizing the input or intermediate network layers of pre-train language model (PLM), attempting to enhance the semantic information of representation through the integration of specialized symbols or extrinsic prior knowledge. We roughly divided into three types (as shown in

Figure 1):

Vanilla based method is a straightforward approach to acquiring a given span representation by feeding raw text tokens series into pre-trained encoder.

Marker based method inserts independent entity markers like

amidst text tokens to highlight the presence of entities, aims at attracting more model attention.

Enumerate based method enumerates all posible entity candidates from plain text and then concatenate them after text tokens, entity tokens share the position ids with candidates as well. For these methods above, the distinguished LSTM-CRF [

6] is a typical vanilla based sequence labeling method, and PURE [

7] is a combination of marker based method and enumeration based method, which adopts marker based method during NER phase and enumerate based method for RE phase, that achieved SOTA performance. PL-Marker [

8] is a typical enumeration based method that promoted the SOTA further.

In addition to the above three methods, what we develop in this paper can be classified as the fourth class named

annotate & enumeration based method. It’s an novel semantic enhancement approach with external knowledge, inspired by external knowledge based aproaches [

3,

9,

10]. We argue that a thorough comprehension of label semantics will significantly enhance the IE model abilities, what serves as a premise for our work.

As shown in

Figure 1, our principal improvement over preceding methods lies in the insertion of external prior knowledge (i.e., label annotations) into the PLM input sequence, aiming to leverage PLM’s internal layers to enhance semantic interaction between label and text. This represents the first round semantic interaction in LAI-Net framework.

Unlike the lexicon adapter-based methods [

11,

12] and lattice-based methods [

13,

14,

15], we manually expand the label information and embed it between text tokens and enumerated candidates then feed the series into a pre-trained model. We further enhance the representation by combining word vectors using downstream neural networks. Formally, the augmented representations derived from the aforementioned methods can be summarized as:

where

is an tensor operator, equipped to execute series of operations including tensor addition, tensor multiplication, tensor concatenation, etc., or even could be a neural network. And superscripts

denote the commencement and termination tokens of a span or annotation, while the subscripts

represent the disparate token types.

Based on the first round semantic interaction, we further meticulously crafted with selectively designed downstream network layers. The main innovations and improvements lie in the following aspects:

We explore a novel two-round semantic interaction approach for enhancing span representations, wherein the first round interaction reorganizes the PLM input with annotated information in what we term an annotation & enumeration-based method, and the second round interaction employs GCN built atop Gaussian Graph Generator modules to facilitate label semantic fusion.

We conduct a coarse screening with a entity candidate filter to eliminate out spans that are clearly not real entities, which also promotes the saving of computing resources.

Experiments demonstrates that our method, while slightly lagging behind current SOTA in NER performance, takes the lead in the downstream RE task, surpassing the current SOTA performance.

2. Related Work

Recently, academic interest in span representation enhancement has surged, providing a substantial impetus to E2ERE. Traditional neural network based methods often ignore non-local and non-sequential context information from input text [

16], what is exactly GCNs [

17,

18] excel in. GCNs, what our discussion centered on, have been widely used to model the interaction between entities and relations in the text, and has been demonstrated as a typical and effective approach. GCN-based approaches typically leverage a predefined graph structure, which constructed from plain text, to facilitate information propagation among nodes, thus capturing text’s non-linear structure and enhancing NER and RE models’ capabilities to capture both global graph structures and representations of nodes and edges. Mostly GCN based methods [

2,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23] utilizes different approaches to define nodes (sentences, words, tokens, spans, labels, etc.), and these nodes can be connected by syntactic dependency edges [

24,

25,

26,

27], re-occurrence edges [

16], co-occurrence edges [

28,

29], adjacent word edges [

16,

27,

30], adjacent sentence edge [

27], etc. And then perform convolution operations on the graph to facilitate the flow of information between nodes, which enables nodes to efficiently acquire both local and global information. This further refines node representations and downstream network performance. Building on these advances, our work also adopt a GCN based method to design the interaction between entities and relations.

3. Methodology

3.1. Task Definition

Given a sentence formularized as

with

m words (or

n tokens,

naturally), the goal of E2ERE task is to recognize a set of entity spans and relationships of entity pairs automatically, which can be written as

. Every entity

e, which attaches specific type (e.g. person (

PER), organization (

ORG)), is a sequence of tokens. Every relation

represents the relationship between

and

, and also attaches a specific type (e.g. organization affiliation relation (

ORG-AFF))

1. Formularly, we define the set of possible entity types and relation types as

,

respectively.

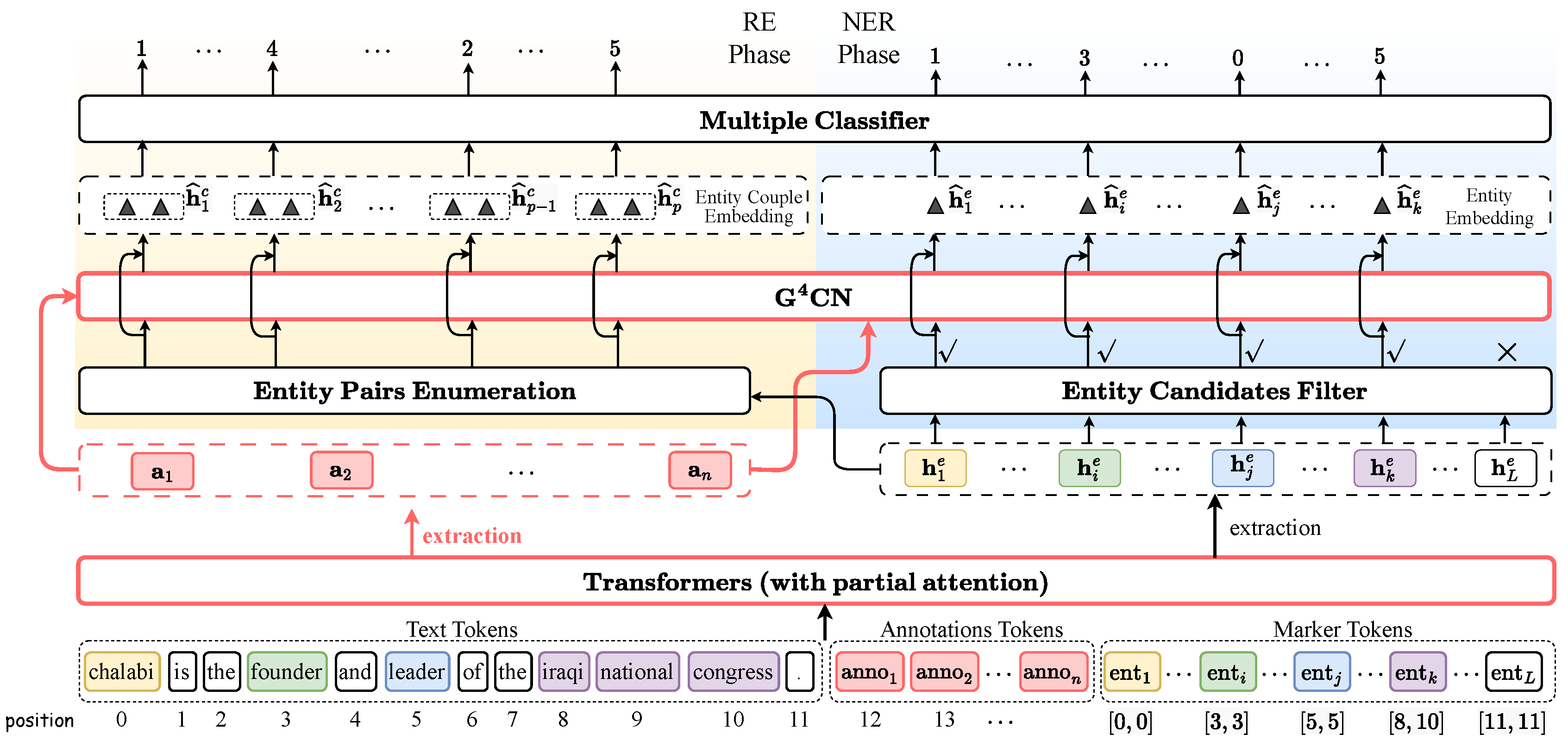

3.2. First Round Semantic Interaction

During data processing, we concatenate text tokens, annotation tokens, and marker tokens sequentially to formulate a unified input sequence (the bottom element of

Figure 2). The PLM encoder conducts the first round semantic interaction, then output the encoded representation, which is semantic amalgamation of the three types tokens.

Text Tokens Our approach breaks down the words from raw text into text token sequences as part of the model input.

Annotation Tokens Inspired by [

3,

31], we augment semantic information by manually annotating the entity (or relation) abbreviated label both in NER and RE phase. For example, the abbreviated entity type

GPE can be annotated as "geography political entity", a fully-semantic unbroken phrase. Correspondingly, the abbreviated relation type

ORG-AFF can be annotated as "organization affiliation". Each label is manually expanded to enrich semantic content and then tokenized into annotation tokens (highlighted by red rectangle in bottom of

Figure 2), which are appended to the text tokens sequentially.

Marker Tokens We enumerate all potential consecutive token sequences (i.e. entity candidates) not exceeding a predefined limitation of length

c (with

) within a sentence, labeling each with an entity type. If

, as shown in

Figure 2, the set of all the possible spans from sentence "

chalabi is the founder and leader of the iraqi national congress." can be written as

"chalabi", "chalabi is", "is", "is the", "the founder", "founder", "founder and", "and", "and leader"

. The

i-th span can be written as

, where

and

are indicative of start and end position id of entity span respectively. Therefore, entity candidate series can also be written as

given position id perspective. Thus, the number of candidate for a sentence with

m words:

.

In model input, we define a start marker (

M) and an end marker (

), which form a pair of marker tokens, respectively represent the start and end of an entity span and are appended subsequent to annotation tokens. The start and end marker share the same position embedding with corresponding span’s start token and end token respectively, while keeping the position id of original text tokens unchanged. From an PLM encoder input perspective, every marker is a token element of tokens series, called marker token. As shown in

Figure 2, entity

chalabi is highlighted by light yellow bordered square, and its corresponding markers noted by a colorful non-bordered square with line frame differred in various entity labels (white means non-entity). In conclusion, the complete input sequence can be represented as Eq.(

5), where

is a token broken from label annotation,

represent start and end marker token respectively.

Partial Attention Although special tokens, such as

[CLS] and

[SEP] serve to isolate different types of tokens, there still exists semantic interference among them. The straightforward blend of annotation tokens and marker tokens with text tokens may disrupt semantic consistency of raw text. To mitigate this, we devise a partial attention mechanism, allowing selective semantic influence among the differ types of token. This mechanism can effectively control the information flow (could be regard as a kind of visibility) between different tokens, by adjusting the value of elements of the attention mechanism mask matrix. It suppresses the information interaction among tokens mutual invisible, while enhancing the information interaction among tokens mutual visible. Experimental results show that partial attention effectively improves model performance. See

Appendix B for more detail information about partial attention.

3.3. Second Round Semantic Interaction

To refine semantic integration, we introduce second round semantic interaction, employing a semantic integrator that explicitly model interactions between entity candidates and label annotations. The semantic integrator consists of multiple GCN layers with randomly generated adjacency matrix, treats both entity spans and label annotations as nodes, and establishs connections between nodes through the construction of a graph

. So that the interactions between nodes can be explicitly modeled. A GCN typically necessitates a manually predefined and fixed adjacency matrix to depict the inter-nodes connections. The fixed adjacency matrix fixes the perspective from which the model understands the semantics. However, it’s naturally to note that the inter-nodes connection cannot be predetermined accurately when considering our task. Otherwise, our task would be meaningless. Therefore, inspired by [

22,

32], we forgo a static adjacency matrix in favor of a multi-view graph, called

aussian

raph

enerator based

raph

onvolutional

etworks (

).

unlike vanilla GCN which takes a fixed adjacency matrix, it gives up fixing the edge weights and set the edge weights via trainable neural networks during the network initial stage, which allows model to assimilate semantic contexts from multiple perspectives.

First, we attach every node with a Gaussian distribution

, where both

are generated by trainable neural networks, formulated as in Eq.(

6), (7), and set the activation function

as the SoftPlus function, since the standard deviation of Gaussian distribution is bounded on

. Then, simulate edge weight through coumpute the KL divergence

between two Gaussian distribution of node, where

. So we can obtain a number of Gaussian distributions for the multi-view graph, each

here corresponds to a node representation

. Thus, a vanilla GCN’s value-fixed adjacency matrix

can be modified to be a

’s value-varied adjacency matrix

, where

k is number of nodes. The whole process can be formulated as Eq.(8), where

are matrixs formed by concatenating multiple nodes (span or annotation) in constructed heterogeneous graph

, and

is vanilla GCN, see detail formulas in

Appendix A.

3.4. Name Entity Recognition

Span and Annotation Representation We extract the contextualized representations

for individual token

s from PLM output, and naturally obtain the involved mathematical formulas for spans and annotatations as Eq.(

9) and Eq.(10), where

. And

is embedding of first and last token of a certain type of label annotatation, respectively.

is embedding of first token and last token of a entity candidate respectively, and

indicates the embedding of start and end token of marker respectively. Linear layer

used to harmonize dimensional space.

Entity Candidates Filter Before the development of the entity candidates filter module, we attempted to train the model, but it ended in failure. The reasons can be summarized as: 1) During the initialization phase of training, model parameters are randomly assigned values, leading to lots of candidate entities being randomly predicted as real entities in early phase. This further causes the adjacency matrix of the graph neural network to become excessively large in scale, resulting in extremely slow network training and significant resource consumption. 2) Among the numerous candidate entities enumerated, positive sample entities are extremely few while negative sample entities are abundant. This easily induces the model to tend towards classifying all entities as non-entities to achieve the minimum loss value, which is not the desired outcome. To overcome the aforementioned issues, we devise a binary classifier acts as a entity filter, performing coarse screening for all enumerated entities by discarding non-genuine entities, thus optimizing subsequent predictions.

As for loss function, the primary aim of entity filter is to maximize the likelihood function, what drove us follow [

2] to adopt likelihood loss function as Eq.(

11), where

indicates a set of real entity spans. In addition to intuitive time consumption optimization, experimental results indicate that entity filter successfully alleviates model weakening engendered by negative samples and enhances overall performance.

Span Classifier We conduct span representations classification through a linear classifier, utilizing cross-entropy loss to direct the learning process. The combined loss function

is optimized during training, using

from Eq.(

11)-(12), with dropout layers for regularization.

In addition, [

8] had proved that packing a series of related spans into a training instance can promote the NER model performance, that naturally prompt us to follow the effective measures when reorganize input.

3.5. Relation Extraction

Subject marker In RE phase, we design our Annotate & Enumeration Based method (as demonstrated in

Figure 1) to acquire the enhanced representation. Concretely, we adopt the marker based approach (shown in

Figure 1), and insert a pair of subject markers, called solid markers by [

8], into left and right of subject entity, and enumerated object candidate spans following on the heels of annotatation tokens to extract relations involving the subject entity.

Entity pairs Representation We match subject and object representations up pairwise to obtain a series of entity pairs (

). And the label semantic confused pair representation formulas can be written as Eq.(

13), where

are matrixs formed by concatenating entity pair or relation label annotation representations.

The loss function of RE phase is the cross-entropy loss.

4. Experiments

Datasets We utilize 3 widely used standard corpora: 1) ACE05 spans various domains (newswire, online forums), and contains 7 entity types and 6 relation types between entities. 2) SciERC [

33] is a scientific dataset built from AI conference/workshop proceedings across four communities. It includes 7 entity types and 7 relation types. 3) ADE [

34] consists of 4,272 sentences and 6,821 relations extracted from medical reports.

Metrics The model with best F1 performance on test set will be selected on a fixed number of epochs. Both micro and macro average metrics are used to evaluate the model performance, former for ACE05/SciERC and latter for ADE. For NER task, an entity prediction is correct if and only if its type and boundaries both match with those of a gold entity. For RE task, a relation prediction is considered correct if its relation type and the boundaries of the two entities match with those in the gold data. We also report the strict relation F1 (denoted RE+), where a relation prediction is considered correct if its relation type as well as the boundaries and types of the two entities all match with those in the gold data. We show detailed experimental settings in

Appendix B.

4.1. Main Results

To ensure the credibility of experimental results, we conducted multiple experiments with different random seeds on all datasets (relevant settings are detailed in

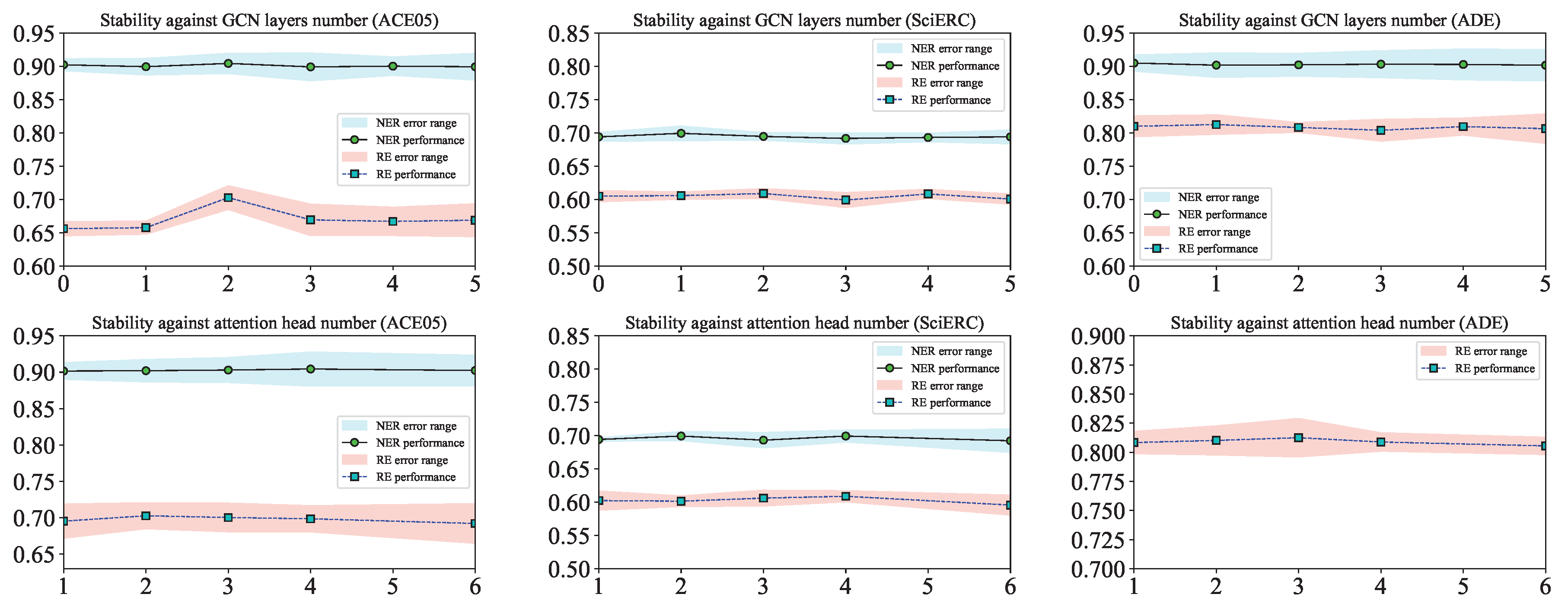

Appendix B.1), and the stability of running are presented in

Appendix B.10.

4.1.1. Results Against Horizontal Comparison

Table 1 presents a horizontal comparison with baselines, focusing on comparing excellent models developed in recent years, including several previous SOTA models (detail in

Appendix B.2). In terms of NER task, our method is on par with the current SOTA, with the discrepancy across three datasets ranging from 0.39% to 0.1%, which achieves sub-optimal performance. Starting from a slightly lower NER performance compared to the SOTA, our method still achieved a performance gain of 2-10% on relation F1 and strict relation F1, consistently outperforming all selected baselines, even with the error propagation between NER and RE task. For example, on ACE05, our method exhibits a 0.24% disadvantage in NER phase, but takes the lead in the downstream RE phase, surpassing the current SOTA by 0.41%, setting a new SOTA record. Similarly, our method, despite having a 0.39% and 0.1% disadvantage in NER performance respectively on SciERC and ADE, achieved performance improvements of 10% and 0.52%. All these improvements demonstrate that two-rounds semantic interactions indeed further utilizes the predicted entities from the NER phase, significantly improving the performance of relation recognition with slightly compromising NER performance.

4.1.2. Results Against Significant Hyperparameters

Table 2 delineates the impact of varying significant hyperparameter of

on the performance of LAI-Net. For the number of GCN layers, we consider a range from 0 to 5, with zero indicating the absence of GCN for semantic interaction and more layers corresponding to increased communication times among nodes within the graph. As for the number of attention heads, we opt for values of 1, 2, 3, 4, and 6. The deliberate exclusion of the value 5 is attributed to the fact that the encoder’s hidden dimension is not divisible by 5, a constraint inherent to the multi-head attention mechanism.

The table permits an intuitive observation that: (1) an increase in the GCN layers number does not linearly translate to enhanced performance; an excessive GCN layers number can exert a deleterious effect on the model, with the more optimal layers number identified as either 1 or 2; (2) concerning the number of attention heads, the more optimal solution exhibits some variation across different datasets, yet it is unequivocally clear that neither an excessively high (e.g. 6) nor a disproportionately low (e.g. 1) number of attention heads can fully capitalize on the GCN’s capabilities.

4.2. Inference Speed

There is justification to assess whether the adoption of GCNs to enhance F1 performance has made trade-offs respect to inference efficiency, for the reason that GCNs have certain efficiency disadvantages typically. Hence, We conducted a comparison between PL-Marker and LAI-Net in terms of inference speed, that experiment was evaluated on a GeForce RTX 3090 24GB GPU with a evaluate batch size of 16. We use Bert-base model for ACE05 and SciBert for SciERC.

As shwon in

Table 3, we indeed sacrificed varying degrees of inference efficiency in exchange for varying degrees of improvement in F1 performance. Overall, the greater the sacrifice, the greater the benefit.

4.3. Ablation Study

4.3.1. Ablations Against Entity Filter

Considering the binomial surge in candidate entity quantity accompanying increased entity length in NER phase, the relatively paltry positive examples can be easily overwhelmed by a vast array of negative samples, thereby instilling the network a strong propensity to categorize all samples as negative, leading to difficulty in accurately identifying genuine entities. To mitigate this, LAI-Net incorporates a deliberately inserted filter prior to the entity classifier to preliminarily sieve out spans that are clearly non-entity. To validate whether said filter genuinely facilitates the NER process, we devised associated ablation experiments. As depicted in the two rightmost columns of

Table 2, the presence of the filter effectively improves NER performance, with advantages most conspicuous on the ACE05 dataset (surpassing no-filter models by 1.74% in terms of F1 scores) and improvements of varying degrees are also observed on other datasets.

4.3.2. Ablation Against Two Rounds of Interaction

We conducted ablation experiment specifically targeting the two-round semantic interaction. Drawing upon the outcomes of the experiment, we can directly evaluate the extent to which our devised dual semantic interaction genuinely augments the model’s performance. What should be noted is that the second round interaction is built upon the annotated label information (that’s what the first round interaction do), so the second round interaction ceases to exist once the label annotation information is no longer injected. However, the existence of the second round interaction does not affect the first round interaction. As shown in

Table 4, no matter which round of semantic interaction is eliminated, it invariably leads to adverse effects of varying magnitudes on the newly SOTA we have developed, encompassing the precision, recall, and F1-score metrics. From the perspective of performance degradation, the detrimental effect of eliminating the second round interaction on the basis of LAI-Net is significantly more pronounced than the impact of further removing the first round of interaction on the basis of w/o 2nd round interaction, with the discrepancy peaking at over 21-fold (

for RE+ in ACE05).

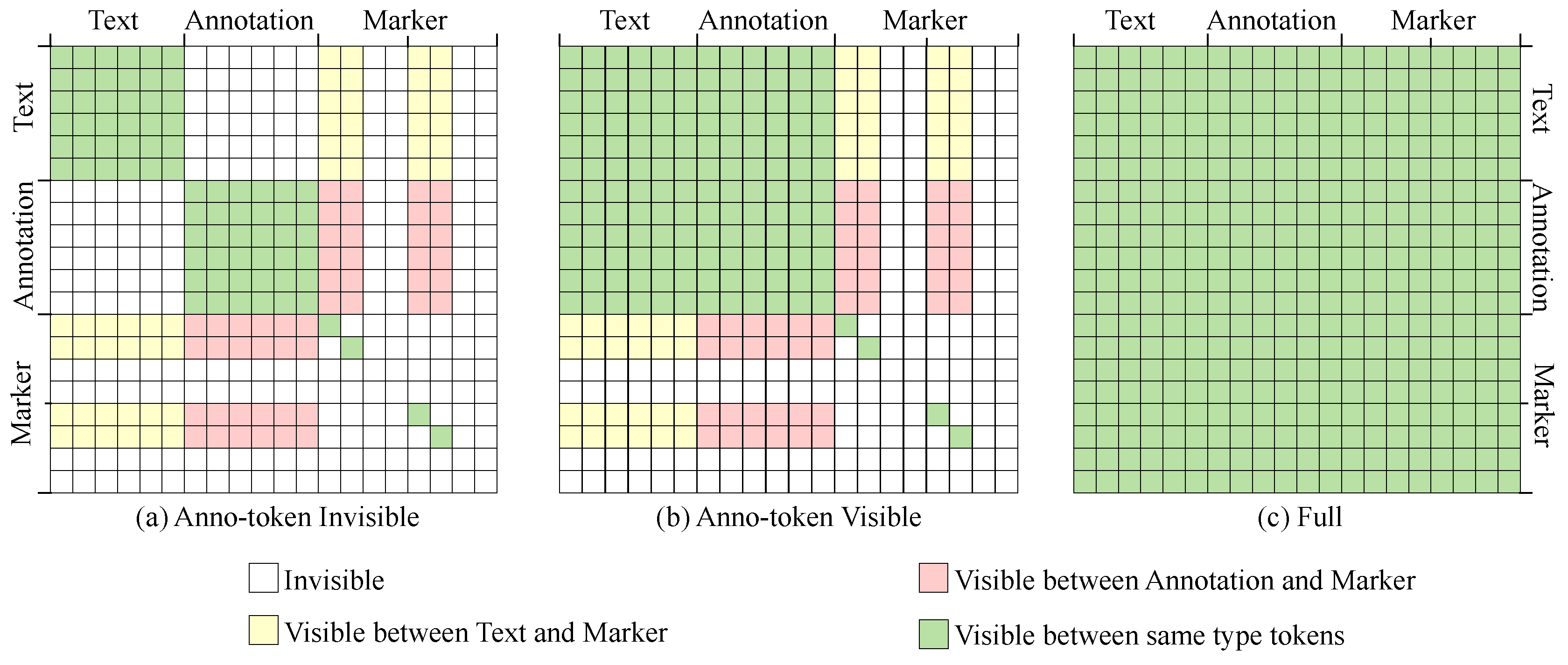

4.3.3. Ablations Against Attention Mask Matrix

In order to evaluate the efficacy of partial attention matrices, we selected three distinct attention mask matrices for ablation (detail explaned in

Appendix B.11), namely: the full attention matrix, wherein all tokens are mutually visible; the anno-token visible attention matrix, where annotation tokens and text tokens are intervisible; and the anno-token invisible attention matrix, with annotation tokens and text tokens also being intervisible. Irrespective of the attention masking matrix employed, tokens of the same type remain mutually visible during the computation of attention scores.

As

Table 5 elucidates, across all three datasets, the anno-token invisible attention matrix exhibits a markedly superior performance with strict F1 metrics compared to the other attention matrice types. The anno-token visible attention matrix comes in second place, with its largest deficit compared to the top-performing technique capping out at 4.7% across the varied tasks encapsulated within the trio of benchmarks. Meanwhile, the fully attention matrix acts a performance lagging behind the peak achieved score on each respective dataset (max up to 6.28%), indicative of appreciably inferior capabilities amongst the range of workloads tested.

We attempt to analyze the underlying reasons, which may lie in the following points: (1) the mutual visibility mechanism between annotation tokens and text tokens establishes a conduit for semantic communication, thereby enhancing the semantic richness of the embeddings for both annotations and text. On the one hand, this enables annotation tokens to fully comprehend background information of text, which directly impacts their high-dimensional semantic representation. On the other hand, text tokens can also fully integrate the information from annotations, which directly facilitates the screening and categorization of candidate entities. (2) conversely, the full attention matrix allows for the intermingling of semantic information among annotation tokens, text tokens, and entity candidate tokens, which may lead to an excessive infusion of additional semantics, resulting in semantic redundancy, and ultimately causing a decline in model performance.

5. Conclusion

Faced with the challenges posed by sub-task excessive separation and modeling gaps between entities and relations, we propose LAI-Net, which leverages a two-phase semantic interaction and attains SOTA performance in both NER and RE tasks. The key novelty is the multi-phase semantic interaction framework to effectively inject external knowledge and unify representations for entities and relations. We manually annotate label abbreviations to fully-semantic unbroken phrase for expand lexical semantic, and then leverages to fuse information from latent multi-view. And an entity candidate filter is embed to coarse screening of candidate spans for NER. Experiments on several datasets show that our LAI-Net allows high-level semantic information flow and facilitates the E2ERE task, successfully achieves the SOTA performance.

Author Contributions

Rongxuan Lai participated in and led all aspects of the research, including but not limited to data analysis and preprocessing, algorithm design, code implementation, experimental procedure formulation, analysis of experimental results, writing and reviewing of the paper. Zhenyi Wang and Haibo Mi contributed to the algorithm design, conducted the data analysis, and critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. Wenhui Wu and Li Zou was responsible for the statistical analysis and interpretation of data, and also helped in revising the manuscript for better clarity and coherence. Feifan Liao participated in the data collection and contributed to the writing of the sections related to methodology and results. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript and have agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used during the current study in this article are available publicly in

Appendix B.1. Access to these data is open to all interested researchers, and any restrictions on data availability, such as those related to participant privacy or confidentiality can be found in the websites mentioned in

Appendix B.1. The processing of the data and the associated code will be completely transparent after the paper is accepted.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Key R&D Program of China (Grant No.2024ZD01NL00100). The authors declare no other relevant financial or non-financial interests related to the content of this manuscript that could be perceived as influencing the work reported.

Conflicts of Interest

This research was funded by the project with the grant numbers 2024ZD01NL00100. The authors declare no other relevant financial or non-financial interests related to the content of this manuscript that could be perceived as influencing the work reported. This statement is provided to ensure a transparent and unbiased evaluation of the research.

Appendix A Vanilla Graph Convolutional Network

Typically, a good text representation is a prerequisite for achieving superior model efficacy, which has motivated numerous researchers to try to leverage contextual features through diverse model architectures to better comprehend textual semantics, thereby enhancing the representation of text. Among all these architectural choices, Graph Convolutional Network (GCN), whose goal is to learn structure-aware node representations on the graph, is a widely utilized framework for encoding information within graphs, where in each GCN layer, every node engages in information exchange and communication with neighboring nodes through their connections (called edges). The efficacy of the GCN model in encoding contextual information on a graph of input sentences has been demonstrated by numerous prior studies.

Now, we briefly describe the vanilla graph convolutional networks in mathematical form. The first step in utilizing GCNs is to build a graph from plain text, where represents a node of , and represents the edge between nodes and , respectively. The structural information that GCN can comprehend is concretely manifested in sentences as the dependencies between words, which is represented by an adjacency matrix . In vanilla GCN, if or there is a dependency connection (arc) between two words/tokens and , and otherwise. However, in our work, we adopt a newly method to initiates the with neural networks.

Based on the graph with adjacency matrix

, for each node

, the

th GCN layer gathers the information carried by its neighbor node and computes the output representation

for

by:

where

is the activation function, and

denotes the output representation of

from the

-th GCN layer,

and

are trainable matrices and the bias for the

l-th GCN layer, respectively.

In the other words, the

l-th layer in a vanilla GCN can be written in the form of matrices as follows:

with

is the combination of all initial node representations, where

is the normalized symmetric adjacency matrix and

is a parameter matrix for the

l-th GCN layer,

is the diagonal node degree matrix, where

,

is a non-linear activation function like

.

Finally, the entire

L-layer vanilla GCN modeling process can be formulated as:

Figure A1.

Statistical analysis diagram of algorithm stability, in which each data point represents the averaged F1 performance with various random seeds, and the shaded area surrounding the data line indicates the error range under the specified hyperparameters (GCN layer number or attention head number), which we measure with standard deviation.

Figure A1.

Statistical analysis diagram of algorithm stability, in which each data point represents the averaged F1 performance with various random seeds, and the shaded area surrounding the data line indicates the error range under the specified hyperparameters (GCN layer number or attention head number), which we measure with standard deviation.

Appendix B Implement Details

Appendix B.1. Datasets and Preprocess

We selected two standard corpus (ACE05, SciERC) in terms of E2ERE task.

1) ACE05

2 is collected from a variety of domains (such as newswire and online forums). It includes 7 entity types, and include 6 relation types between entities. For data processing, we use the same entity and relation types, data splits

3, and pre-processing as [

38,

39] (351 training, 80 development and 80 testing).

2) SciERC [

33] is a scientific-oriented dataset, which is built from 12 AI conference/workshop proceedings in four AI communities, and includs 7 entity types and 7 relation types.

In terms of experiment, we run our model 10 times with different random seeds, and report averaged results of all the runs.

Appendix B.2. Chosen of Baselines

To ensure fairness and comprehensiveness in performance comparison as much as possible, we have established several principles for selecting baselines The first is to select well-recognized baselines from those cited in the SOTA works published in recent years. The second principle is to cover models of encoder-only, decoder-only and encoder-decoder architectures as comprehensively as possible, and what the priority is given to models that have similar or comparable parameter scales to our PLM during the selection process for encoder-only based baselines. Thirdly, one or more datasets should be the same as those used in our work. Lastly, we tend to select methods that formally published in relatively authoritative conferences or journals, which is not mandatory.

Appendix B.3. PLMs and Hardware Devices

For fair comparison with previous works, we employ bert-base-uncased [

40] as the encoders for ACE05, and use the in-domain scibert-scivocab-uncased

4 [

41] as the encoder for SciERC, and all the experiments are executed using three GeForce RTX 3090 24GB GPUs.

Appendix B.4. Optimizer and Learning Rate Settings

We use AdamW optimizer during training. We set the learning rate as 4e-4 for both NER and RE task. We had tried to set different learning rate for different layers, and experiment results show that it’s useless.

Appendix B.5. Maximum Length Settings

We respectively set the maximum length of reorganized sentence C as 150, 150 on ACE05, SciERC. As enumerating possible spans, we set the maximum span length L as 8 for all datasets, and limit the number of entity candidates as 220 for every train/eval sample.

Appendix B.6. Batch Size and Epoch Settings

In NER phase, we respectively set batch size as 16 per GPU for SciERC, 20 per GPU for ACE05. And in RE phase, we set the batch size as 40 per GPU for SciERC, 50 per GPU for ACE05. We set the epoch as 80 for all Datasets in NER phase, and 60 for all dataset in RE phase.

Appendix B.7. Avoidance the Negative Influence of Annotation

Considering that our method increases the length of the training instances, which could impact the model’s performance, we strive to alleviate this negative impact as much as possible. Firstly, avoid using overly long annotation information, but simply restore label abbreviations(such as restoring the PER tag to "person" and the PER-ORG tag to "person-organization"), and the length of the annotations used in the experiments does not exceed 10 words. Secondly, using adjusted attention mask matrices to minimize semantic confusion caused by the insertion of annotations.

Figure A2.

Diagrams of three types attention mask matrix with an assumption that there is two entity candidates.

Figure A2.

Diagrams of three types attention mask matrix with an assumption that there is two entity candidates.

Appendix B.8. Cold Start Settings for NER

It should be noted that, due to the enumeration of a large number of non-entity spans as negative samples in NER pahse, which extremely likely to lead to unable-convergence train, or the phenomenon that the model directly predicts all spans as non-entities. Therefore, we set up a specific cold start process for training. In the first half of training, we use the true labels as the filter result for next entity classification in order to calculate the loss to update the parameters. This guides the model during early learning before exposing it to negatively labeled non-entity spans. In actual training, we set the cold boot epoch number as 15, 40 for ACE05, SciERC respectively. Moreover, according to unpublished experimental results, experiments without cold start configuration were utterly incapable of acquiring any knowledge whatsoever, with all performance metrics equaling zero throughout the training phase.

Appendix B.9. Symmetry of Relation for RE

We formulate the directed relation as , with the subject entity always pointing to object entity . Therefore, a triplet with positive relation canbe written as , and its reverse formula is . may refer to different relation types. In RE phase, we consider the subject be left and the object be right by default. Either () or () will be predicted if it’s a really relaiton. Only when they are both predicted to be true (that is, the probability value is greater than the threshold), the triplet () and triplet () will be established.

Appendix B.10. Stability of Training

To ensure the reliability of the experimental data, we repeated the experiments multiple times for each hyperparameter combination, each time initializing the network with a different random seed, and then calculated the mean and standard deviation of the experimental results, as shown in the

Figure A1. The first row of chart in the

Figure A1 represents the fluctuations in NER and RE performance across three datasets for different numbers of GCN layers, The second row of chart in the

Figure A1 represents the fluctuations in NER and RE performance across three datasets for different numbers of attention heads.

Appendix B.11. Parital Attention Mask

Obviously, the series of annotation tokens and marker tokens manually attached after the text tokens does not form a coherent and semantically complete sentence. It inevitably affects the semantic construction from text tokens, and impair the representational ability of word vectors during the PLM encoding process.

To address this potential issue, we adopt a specialized partial attention mechanism to selectively mitigate or enhance the semantic impact of tokens from differed types. In details, by adjusting the value of elements of the attention mechanism mask matrix, we can control the visibility among three types of tokens.

Partial attention can effectively control the information flow between different tokens. It suppresses the information interaction between text and annotations (i.e. invisible) while enhancing the information interaction between text and candidates (i.e. visible).

We show three different masking matrices in

Figure A2, for which we conduct some ablation experiments. In conjunction with

Figure A2, we further elucidate the meaning of the discrete elements within mask matrix. Train our gaze upon the first row of

Figure A2 (a), which delineates the tokens discernible by the text token. The pale green region signifies it can see corresponding tokens, the white space those it cannot see, and the faint yellow elements the marker tokens within its purview. Notably, the two faint yellow squares on the left denote the start marker tokens, while the two on the right denote the end marker tokens.

References

- Tang, W.; Xu, B.; Zhao, Y.; Mao, Z.; Liu, Y.; Liao, Y.; Xie, H. UniRel: Unified Representation and Interaction for Joint Relational Triple Extraction. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2022 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; Goldberg, Y.; Kozareva, Z.; Zhang, Y., Eds., Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2022; pp. 7087–7099. [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Gong, Y.; Wu, Y.; Gong, M.; Jiang, D.; Lan, M.; Sun, S.; Duan, N. Joint Type Inference on Entities and Relations via Graph Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; Korhonen, A.; Traum, D.; Màrquez, L., Eds., Florence, Italy, 2019; pp. 1361–1370. [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Cong, X.; Sun, Z.; Liu, X. Enhanced Language Representation with Label Knowledge for Span Extraction. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; Moens, M.F.; Huang, X.; Specia, L.; Yih, S.W.t., Eds., Online and Punta Cana, Dominican Republic, 2021; pp. 4623–4635. [CrossRef]

- Ji, B.; Li, S.; Xu, H.; Yu, J.; Ma, J.; Liu, H.; Yang, J. Span-based joint entity and relation extraction augmented with sequence tagging mechanism. arXiv preprint arXiv:2210.12720 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Y.M.; Huang, H.; Sun, X.; Wei, W.; Mao, X.L. Relational Triple Extraction: One Step is Enough. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Thirty-First International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, IJCAI-22; Raedt, L.D., Ed. International Joint Conferences on Artificial Intelligence Organization, 7 2022, pp. 4360–4366. Main Track. [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.; Wang, X.; Ni, P.; Li, Y.; Li, G.; Bai, X. Named entity recognition using BERT BiLSTM CRF for Chinese electronic health records. In Proceedings of the 2019 12th international congress on image and signal processing, biomedical engineering and informatics (cisp-bmei). IEEE, 2019, pp. 1–5.

- Zhong, Z.; Chen, D. A Frustratingly Easy Approach for Entity and Relation Extraction. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies; Toutanova, K.; Rumshisky, A.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Hakkani-Tur, D.; Beltagy, I.; Bethard, S.; Cotterell, R.; Chakraborty, T.; Zhou, Y., Eds., Online, 2021; pp. 50–61. [CrossRef]

- Ye, D.; Lin, Y.; Li, P.; Sun, M. Packed Levitated Marker for Entity and Relation Extraction. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers); Muresan, S.; Nakov, P.; Villavicencio, A., Eds., Dublin, Ireland, 2022; pp. 4904–4917. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Han, X.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, X.; Sun, M.; Liu, Q. ERNIE: Enhanced Language Representation with Informative Entities. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; Korhonen, A.; Traum, D.; Màrquez, L., Eds., Florence, Italy, 2019; pp. 1441–1451. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, S.; Li, Y.; Feng, S.; Tian, H.; Wu, H.; Wang, H. Ernie 2.0: A continual pre-training framework for language understanding. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, 2020, Vol. 34, pp. 8968–8975.

- Houlsby, N.; Giurgiu, A.; Jastrzebski, S.; Morrone, B.; De Laroussilhe, Q.; Gesmundo, A.; Attariyan, M.; Gelly, S. Parameter-Efficient Transfer Learning for NLP. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning; Chaudhuri, K.; Salakhutdinov, R., Eds. PMLR, 09–15 Jun 2019, Vol. 97, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, pp. 2790–2799.

- Liu, W.; Fu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, W. Lexicon Enhanced Chinese Sequence Labeling Using BERT Adapter. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers); Zong, C.; Xia, F.; Li, W.; Navigli, R., Eds., Online, 2021; pp. 5847–5858. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, J. Chinese NER Using Lattice LSTM. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers); Gurevych, I.; Miyao, Y., Eds., Melbourne, Australia, 2018; pp. 1554–1564. [CrossRef]

- Sui, D.; Chen, Y.; Liu, K.; Zhao, J.; Liu, S. Leverage Lexical Knowledge for Chinese Named Entity Recognition via Collaborative Graph Network. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (EMNLP-IJCNLP); Inui, K.; Jiang, J.; Ng, V.; Wan, X., Eds., Hong Kong, China, 2019; pp. 3830–3840. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yan, H.; Qiu, X.; Huang, X. FLAT: Chinese NER Using Flat-Lattice Transformer. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; Jurafsky, D.; Chai, J.; Schluter, N.; Tetreault, J., Eds., Online, 2020; pp. 6836–6842. [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Santus, E.; Jin, Z.; Guo, J.; Barzilay, R. GraphIE: A Graph-Based Framework for Information Extraction. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers); Burstein, J.; Doran, C.; Solorio, T., Eds., Minneapolis, Minnesota, 2019; pp. 751–761. [CrossRef]

- Daigavane, A.; Ravindran, B.; Aggarwal, G. Understanding Convolutions on Graphs, Understanding the building blocks and design choices of graph neural networks., 2021. https://distill.pub/2021/understanding-gnns/Published in 2021-9-2.

- Wu, L.; Chen, Y.; Shen, K.; Guo, X.; Gao, H.; Li, S.; Pei, J.; Long, B.; et al. Graph neural networks for natural language processing: A survey. Foundations and Trends® in Machine Learning 2023, 16, 119–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quirk, C.; Poon, H. Distant Supervision for Relation Extraction beyond the Sentence Boundary. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 15th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Volume 1, Long Papers; Lapata, M.; Blunsom, P.; Koller, A., Eds., Valencia, Spain, 2017; pp. 1171–1182.

- Luo, Y.; Zhao, H. Bipartite Flat-Graph Network for Nested Named Entity Recognition. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; Jurafsky, D.; Chai, J.; Schluter, N.; Tetreault, J., Eds., Online, 2020; pp. 6408–6418. [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Zhang, R.; Mao, Y.; Mensah, S.; Liu, X. Relation extraction with convolutional network over learnable syntax-transport graph. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2020, Vol. 34, pp. 8928–8935.

- Xue, F.; Sun, A.; Zhang, H.; Chng, E.S. Gdpnet: Refining latent multi-view graph for relation extraction. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2021, Vol. 35, pp. 14194–14202.

- Shang, Y.M.; Huang, H.; Sun, X.; Wei, W.; Mao, X.L. Relational Triple Extraction: One Step is Enough. arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.05270, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Qi, P.; Manning, C.D. Graph Convolution over Pruned Dependency Trees Improves Relation Extraction. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; Riloff, E.; Chiang, D.; Hockenmaier, J.; Tsujii, J., Eds., Brussels, Belgium, - 2018; pp. 2205–2215. [CrossRef]

- Fu, T.J.; Li, P.H.; Ma, W.Y. GraphRel: Modeling Text as Relational Graphs for Joint Entity and Relation Extraction. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; Korhonen, A.; Traum, D.; Màrquez, L., Eds., Florence, Italy, 2019; pp. 1409–1418. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, W. Attention Guided Graph Convolutional Networks for Relation Extraction. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; Korhonen, A.; Traum, D.; Màrquez, L., Eds., Florence, Italy, 2019; pp. 241–251. [CrossRef]

- Sahu, S.K.; Christopoulou, F.; Miwa, M.; Ananiadou, S. Inter-sentence Relation Extraction with Document-level Graph Convolutional Neural Network. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; Korhonen, A.; Traum, D.; Màrquez, L., Eds., Florence, Italy, 2019; pp. 4309–4316. [CrossRef]

- Christopoulou, F.; Miwa, M.; Ananiadou, S. Connecting the Dots: Document-level Neural Relation Extraction with Edge-oriented Graphs. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (EMNLP-IJCNLP); Inui, K.; Jiang, J.; Ng, V.; Wan, X., Eds., Hong Kong, China, 2019; pp. 4925–4936. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.; Xu, R.; Chang, B.; Li, L. Double Graph Based Reasoning for Document-level Relation Extraction. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP); Webber, B.; Cohn, T.; He, Y.; Liu, Y., Eds., Online, 2020; pp. 1630–1640. [CrossRef]

- Luan, Y.; Wadden, D.; He, L.; Shah, A.; Ostendorf, M.; Hajishirzi, H. A general framework for information extraction using dynamic span graphs. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers); Burstein, J.; Doran, C.; Solorio, T., Eds., Minneapolis, Minnesota, 2019; pp. 3036–3046. [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Ballesteros, M.; Doss, S.; Anubhai, R.; Mallya, S.; Al-Onaizan, Y.; Roth, D. Label Semantics for Few Shot Named Entity Recognition. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2022; Muresan, S.; Nakov, P.; Villavicencio, A., Eds., Dublin, Ireland, 2022; pp. 1956–1971. [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Liu, K.; Ji, G.; Zhao, J. Learning to Represent Knowledge Graphs with Gaussian Embedding. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 24th ACM International on Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, New York, NY, USA, 2015; CIKM ’15, p. 623–632. [CrossRef]

- Luan, Y.; He, L.; Ostendorf, M.; Hajishirzi, H. Multi-Task Identification of Entities, Relations, and Coreference for Scientific Knowledge Graph Construction. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; Riloff, E.; Chiang, D.; Hockenmaier, J.; Tsujii, J., Eds., Brussels, Belgium, - 2018; pp. 3219–3232. [CrossRef]

- Gurulingappa, H.; Rajput, A.M.; Roberts, A.; Fluck, J.; Hofmann-Apitius, M.; Toldo, L. Development of a benchmark corpus to support the automatic extraction of drug-related adverse effects from medical case reports. Journal of Biomedical Informatics 2012, 45, 885–892, Text Mining and Natural Language Processing in Pharmacogenomics. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eberts, M.; Ulges, A. Span-based Joint Entity and Relation Extraction with Transformer Pre-training. ArXiv, 1909; abs/1909.07755. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Lu, W. Two are Better than One: Joint Entity and Relation Extraction with Table-Sequence Encoders. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP); Webber, B.; Cohn, T.; He, Y.; Liu, Y., Eds., Online, 2020; pp. 1706–1721. [CrossRef]

- Ji, B.; Yu, J.; Li, S.; Ma, J.; Wu, Q.; Tan, Y.; Liu, H. Span-based Joint Entity and Relation Extraction with Attention-based Span-specific and Contextual Semantic Representations. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on Computational Linguistics; Scott, D.; Bel, N.; Zong, C., Eds., Barcelona, Spain (Online), 2020; pp. 88–99. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Ji, H. Incremental Joint Extraction of Entity Mentions and Relations. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 52nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers); Toutanova, K.; Wu, H., Eds., Baltimore, Maryland, 2014; pp. 402–412. [CrossRef]

- Miwa, M.; Bansal, M. End-to-End Relation Extraction using LSTMs on Sequences and Tree Structures. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 54th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), Berlin, Germany, August 2016; pp. 1105–1116.

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers); Burstein, J.; Doran, C.; Solorio, T., Eds., Minneapolis, Minnesota, 2019; pp. 4171–4186. [CrossRef]

- Beltagy, I.; Lo, K.; Cohan, A. SciBERT: A Pretrained Language Model for Scientific Text. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (EMNLP-IJCNLP); Inui, K.; Jiang, J.; Ng, V.; Wan, X., Eds., Hong Kong, China, 2019; pp. 3615–3620. [CrossRef]

| 1 |

Both entity type sample and relation type sample mentioned above are quoted from ACE05. |

| 2 |

|

| 3 |

|

| 4 |

SciBERT is a BERT model trained on scientific text, whose corpus includes the full text of 1.14 million scientific papers (82% in biomedical and 12% in computer science), and may be more suitable for natural language processing tasks on SciERC dataset |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).