1. Introduction

Percutaneous liver radiofrequency ablation (RFA) is a minimally invasive and effective treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma and metastatic liver tumors [

1]. By inducing thermal coagulative necrosis, ultrasound-guided RFA minimizes tissue trauma, avoids radiation exposure, and enables faster recovery compared to surgical resection [

2,

3]. However, this procedure can cause significant pain and discomfort, often necessitating deep sedation to achieve adequate analgesia [

4]. Deep sedation is commonly administered via monitored anesthesia care (MAC), which combines local anesthesia, sedatives, and analgesics, particularly in non-operating room settings [

5]. A well-recognized complication of MAC is oversedation-induced respiratory depression, which may result in hypoventilation, upper airway collapse, and subsequent hypoxia [

6,

7]. Therefore, adequate oxygenation is essential to ensure patient safety and procedural success.

Conventional oxygen delivery methods, such as nasal cannulae and simple facemasks, are limited in their ability to provide consistent oxygenation during deep sedation. In contrast, high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) delivers heated and humidified oxygen at high flow rates, offering high inspired oxygen fractions (FiO₂) and producing a mild positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP)-like effect [

8]. HFNC has shown promise in minimizing hypoxic events during procedural sedation and general anesthesia in various settings [

9,

10,

11]. However, its effectiveness during percutaneous liver RFA under MAC has not been well established.

This study aimed to evaluate whether HFNC improves arterial oxygenation, assessed by intra-procedural PaO₂, compared to a conventional facemask during percutaneous liver RFA under MAC. Secondary outcomes included the incidence of hypoxia, changes in P/F ratio and PaCO₂, respiratory rate, and patient satisfaction.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

This prospective, randomized, controlled study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Asan Medical Center (approval number: 2021-0714, 13/05/2021) and registered at the Clinical Research Information Service (registration number: KCT0006221, 17/05/2021). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to enrollment. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patients aged 20 to 80 years with an American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status of I or II and scheduled for ultrasound-guided percutaneous RFA under MAC between July and November 2021 were enrolled. Exclusion criteria included severe chronic pulmonary, cardiovascular, or cerebrovascular disease; a negative modified Allen test; and contraindications to remifentanil or propofol.

Eligible participants were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to either the HFNC or facemask group using a computer-generated block randomization (block size = 2) and sealed opaque envelopes. On the day of the procedure, an investigator (A) who was blinded to outcomes assigned the intervention. A separate investigator (B), also blinded, conducted all post-procedural assessments.

2.2. Anesthetic Management

All patients underwent continuous monitoring, including non-invasive blood pressure, electrocardiography, peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO₂), and bispectral index (BIS). Following confirmation of collateral circulation with a modified Allen’s test, a 20-G radial arterial catheter was inserted for arterial blood sampling.

Baseline arterial blood gas analysis (ABGA, T0) was performed before oxygen delivery. In the facemask group, 100% oxygen was delivered at 6 L/min via a simple facemask, which approximates an FiO₂ of 0.5. In the HFNC group, 100% heated and humidified oxygen was delivered at 30 L/min using an OptiFlow system (Fisher & Paykel®, New Zealand).

Sedation was maintained with a target-controlled infusion of propofol (Marsh model, effect-site concentration 0.8–1.5 μg/mL) and remifentanil (starting at 0.5 ng/mL, titrated as needed). Sedation depth was targeted to a BIS of 60–80 and a Modified Observer’s Assessment of Alertness/Sedation (MOAA/S) score ≤3 [

12]. ABGA was repeated 5 minutes after oxygen delivery (T1). Monitored hemodynamic parameters were recorded at T0 (pre-procedure), T1 (5 minutes after starting RFA), and T2 (end of procedure). When SpO₂ dropped below 95%, a triple airway maneuver (head tilt, jaw thrust, mouth opening) was applied, as oxygen reserve rapidly depletes below 94%, risking a swift drop to <90% [

13]. If SpO₂ further decreased below 90% despite intervention, an airway device was inserted and manual ventilation initiated. All patients were transferred to the post-anesthesia care unit (PACU) for monitoring after the procedure,.

2.3. Ablation Procedure

After planning sonography, percutaneous RFA or microwave ablation (MWA) was performed. Artificial ascites (500–1000 mL of 5% dextrose) were used when needed. The choice of ablation modality and electrode type (Cool-tip™, Jet-tip®, or Proteus®) was determined by the interventional radiologist. RFA was conducted using a 200-W generator (Mygen M-2004, RF Medical) with impedance control for 8 to 18 minutes. For microwave ablation (MWA), a single 13-G antenna was used with a 150-W generator (Emprint™ HP, Covidien) for 6 to 10 minutes. Additional time was provided for patients with multiple hepatic masses.

2.4. Outcome Measurements

The primary outcome was the intra-procedural arterial partial pressure of oxygen (PaO₂) measured at T1. Secondary outcomes included incidence of hypoxia, difference in the ratio of arterial partial pressure of oxygen to the fraction of inspired oxygen concentration between T0 and T1 (∆P/F ratio), difference in arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide between T0 and T1 (∆PaCO2), changes in respiratory rate (RR), and patient satisfaction.

Hypoxia was defined as SpO2 <95% for procedural safety, and severe hypoxia was defined as SpO₂ <90% despite airway maneuvers, requiring mask ventilation. The 95% threshold was selected based on our institutional protocol to enable early recognition of airway compromise during deep sedation. Unlike procedures performed in the lateral or semi-lateral position, percutaneous liver RFA is conducted in the supine position, which significantly increases the risk of glossoptosis. Furthermore, concurrent opioid administration due to severe procedural pain elevates the risk of respiratory depression. Therefore, a conservative SpO₂ threshold was adopted to identify subtle ventilatory impairment at an early stage and enhance patient safety.

For the calculation of the P/F ratio, FiO₂ was assumed to be 1.0 in the HFNC group and 0.5 in the facemask group, based on estimated oxygen delivery via a simple facemask at 6 L/min. Patient satisfaction was assessed using a modified Iowa Satisfaction with Anesthesia Scale (ISAS) [

14]. The ISAS is composed of 11 items rated on a 6-point scale ranging from –3 to +3, with total scores ranging from –33 to +33. Higher scores indicate greater overall satisfaction. The scale has been validated in monitored anesthesia care and has been applied in procedural sedation settings [

15].

2.5. Sample Size Calculation

The sample size was calculated using G*Power 3.1 (α = 0.05, power = 0.8), based on a previous study by Heinrich et al., which reported PaO₂ values as median (IQR): 406 (362–446) mmHg for HFNC and 335 (292–389) mmHg for facemask [

16]. These were converted to mean ± SD using Meta-Converter (

https://meta-converter.com/conversions/mean-sd-iqr), yielding 405 ± 71.3 mmHg and 339 ± 82.3 mmHg, respectively. Based on this, a sample size of 23 per group was required; allowing for a 10% dropout, 26 participants per group (total n = 52) were enrolled.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation or median with interquartile range, and categorical variables as frequencies and percentages. Between-group comparisons were performed using Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney U test for continuous data, and chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical data, as appropriate.

To compare intra-procedural PaO₂ between groups, analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was performed with baseline PaO₂ as a covariate. Similarly, the ΔP/F ratio was adjusted for pre-procedural values using ANCOVA. Linear regression analysis was used to evaluate changes in PaCO₂, adjusting for potential confounders including age, body mass index (BMI), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma, and smoking status. Given the multiple secondary outcomes—including hypoxia incidence, ΔP/F ratio, ΔPaCO₂, respiratory rate, and patient satisfaction—Bonferroni correction was applied to control for type I error. For repeated measures of respiratory rate, a generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) with random intercepts was fitted. The model included group, time, and group × time interaction as fixed effects, and subject as a random effect. An unstructured covariance matrix was used without assuming homogeneity across groups. Model assumptions, including normality of residuals and homogeneity of variance, were assessed for all parametric tests. When assumptions were not fully met, a ranked ANCOVA was performed as a non-parametric alternative to confirm the robustness of the results. As the findings were consistent, the original parametric results were retained for reporting. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics version 29.0.2.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), and a two-sided p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

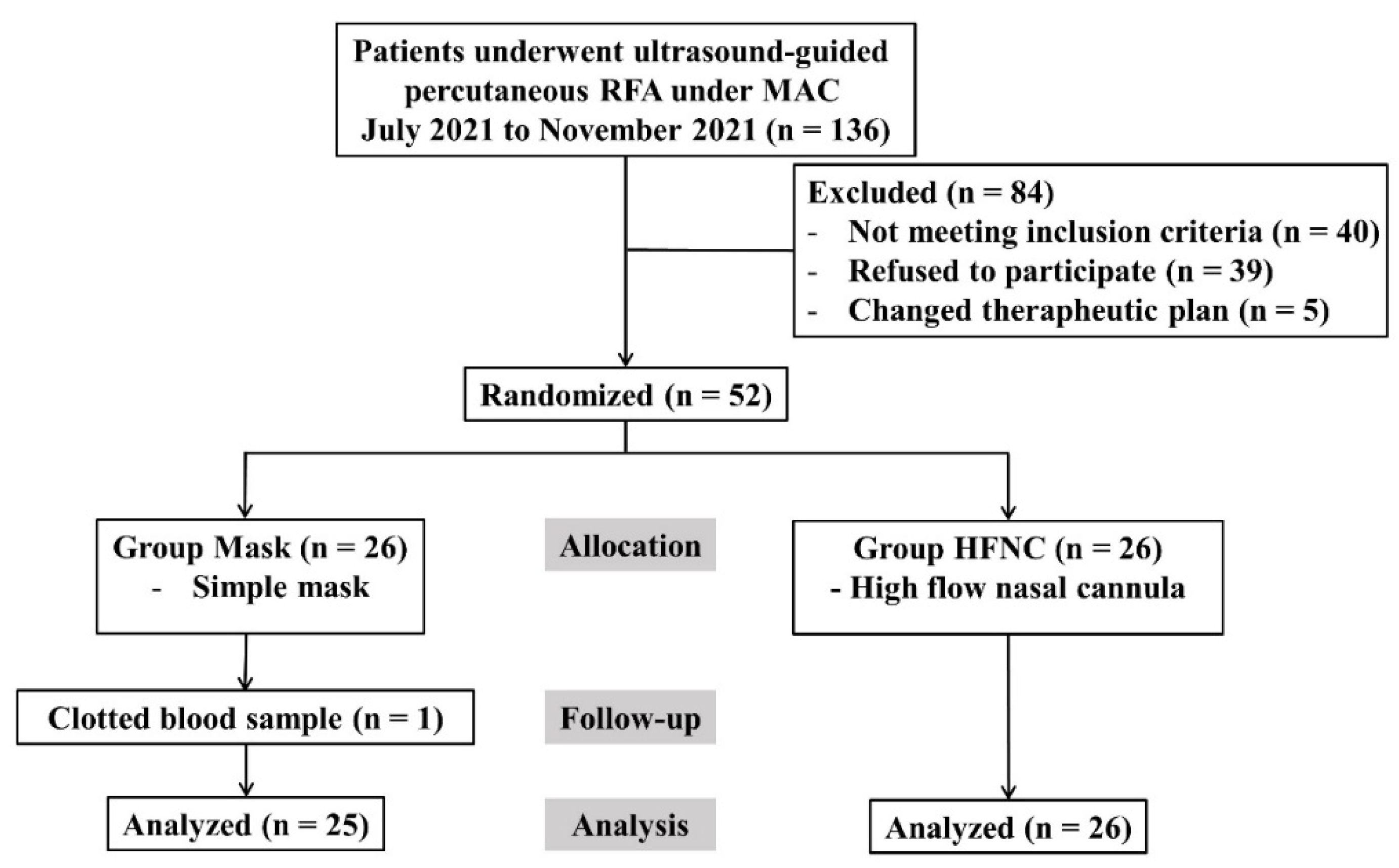

A total of 136 patients scheduled for RFA under MAC between July and November 2021 were screened. Of these, 40 did not meet the inclusion criteria, 39 declined to participate, and 5 were excluded due to changes in the therapeutic plan. Finally, 52 patients were randomized; however, one patient in the facemask group was excluded because of clotted blood samples. Therefore, 51 patients (25 in the facemask group and 26 in the HFNC group) were included in the final analysis (

Figure 1). Baseline characteristics were comparable between groups (

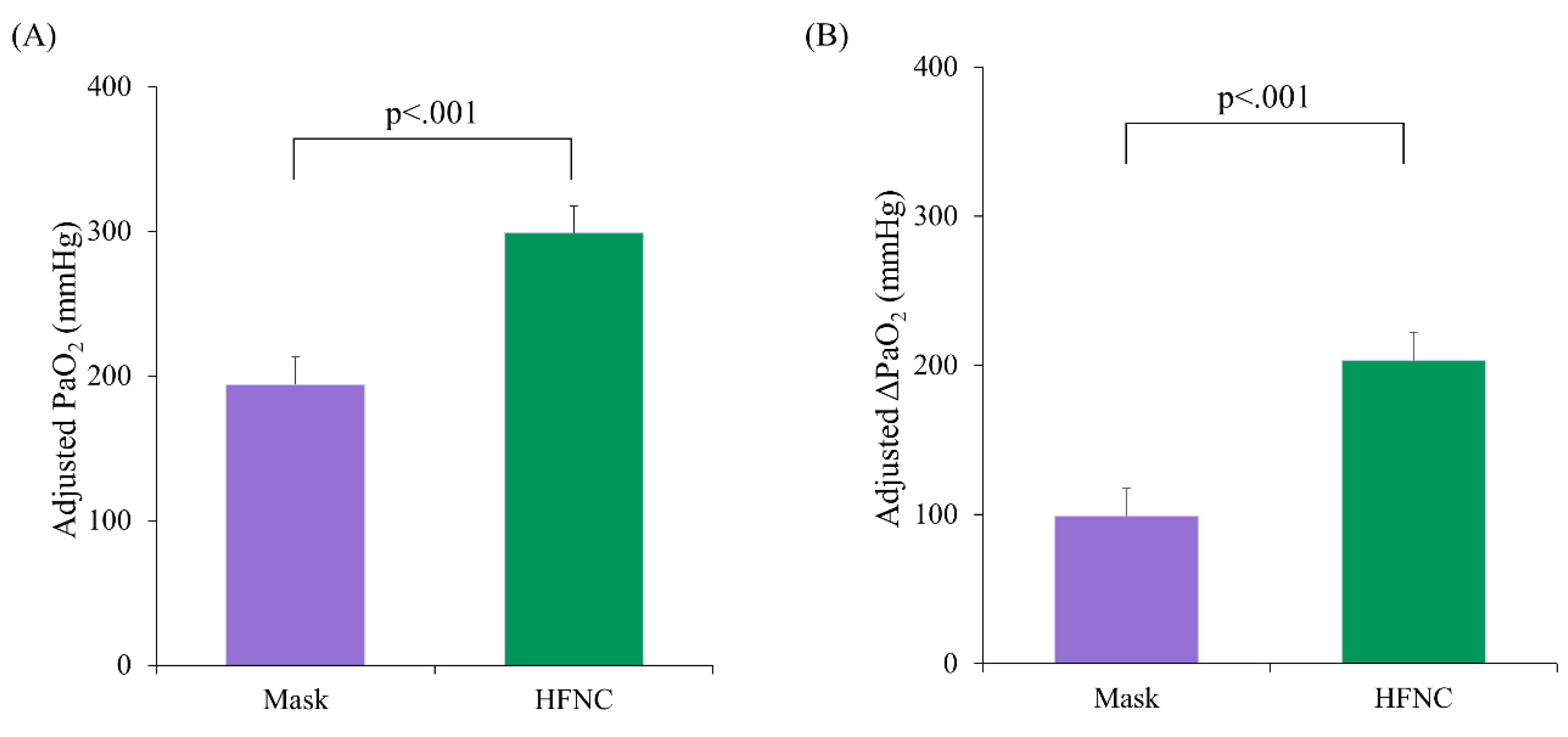

Table 1), despite significantly different pre-procedure PaO₂ levels (p = 0.037). Using ANCOVA with pre-procedure PaO₂ as a covariate, the adjusted mean PaO₂ during the procedure was significantly higher in the HFNC group (298.8 ± 18.6 mmHg; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 261.4–336.2) compared to the facemask group (194.2 ± 19.0 mmHg; 95% CI: 156.0–232.3, p < 0.001) (

Figure 2A). Similarly, the adjusted mean ΔPaO₂ (T₁ − T₀) was significantly greater in the HFNC group (203.4 ± 18.6 vs. 98.8 ± 19.0; difference = 104.6, p < 0.001) (

Figure 2B).

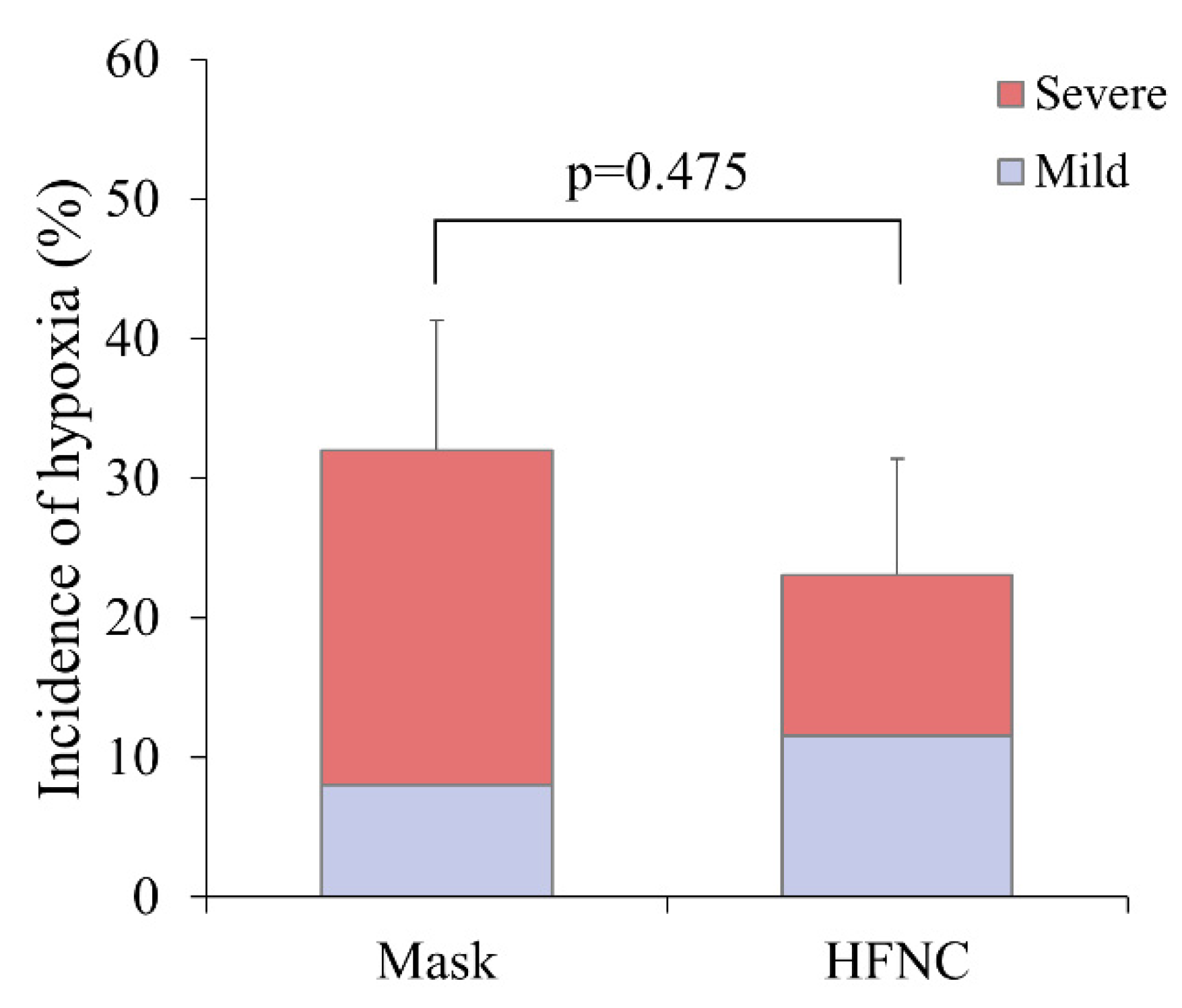

Hypoxia occurred in 14 patients (27.5%), including 8 (32.0%) in the facemask group and 6 (23.0%) in the HFNC group (p = 0.475) (

Figure 3). Severe hypoxia occurred more frequently in the facemask group (24.0% vs. 11.5%), corresponding to a risk ratio of 0.48 (95% CI: 0.13–1.72). However, the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.291). Other ABGA parameters, including ΔP/F ratio and ΔPaCO₂, did not differ significantly between groups (

Table 2). Patient satisfaction, as assessed by the ISAS, was also similar between groups (

Table 2).

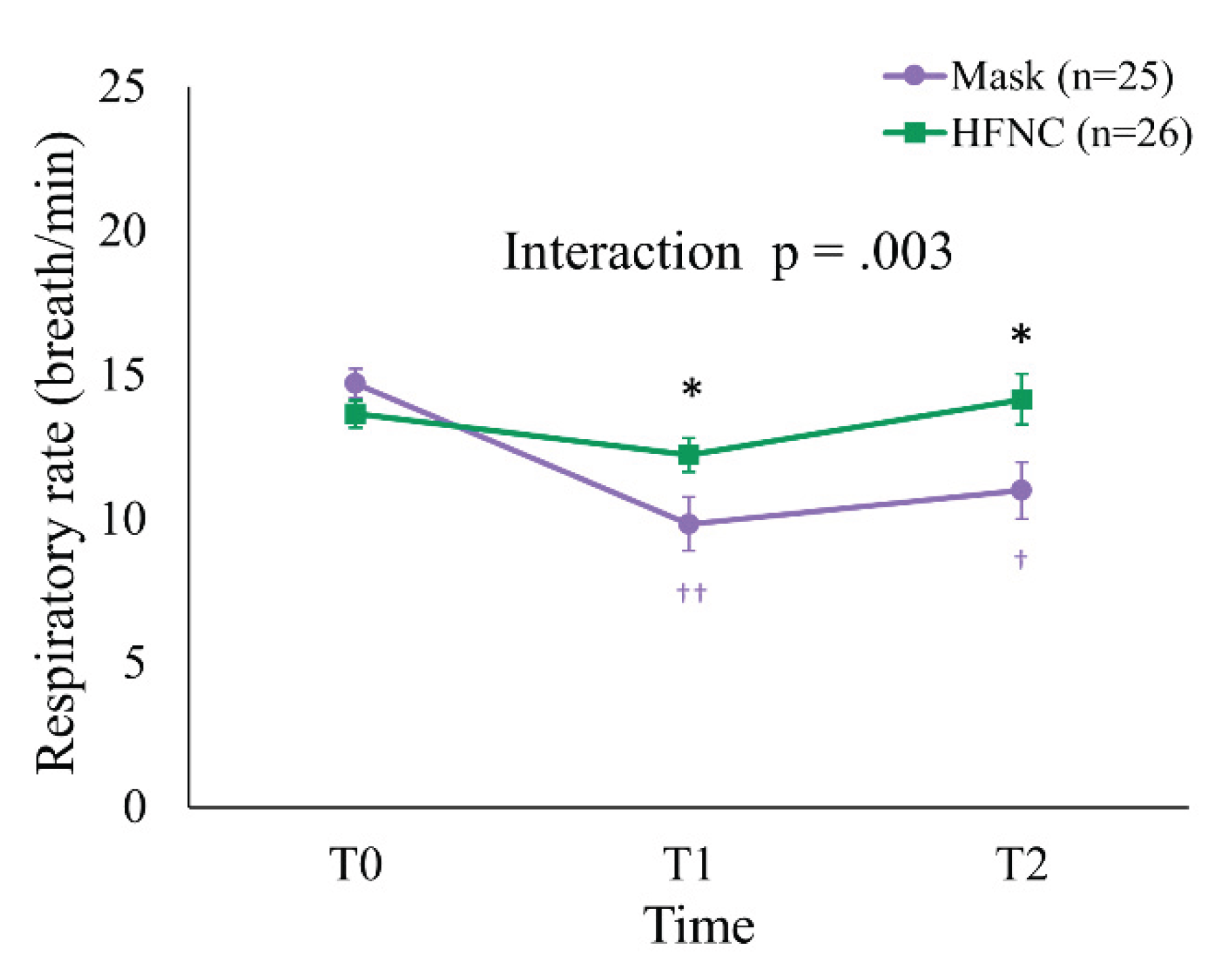

At T0, the mean RR was 13.7 ± 2.4 and 14.7 ± 2.5 breaths/min in the HFNC and facemask groups, respectively (p = 0.131). At T1 and T2, the mean RR was significantly higher in the HFNC group (T1: 12.2 ± 3.0 vs. 9.8 ± 4.7 breaths/min, p = 0.036; T2: 14.2 ± 4.5 vs. 11.0 ± 4.9 breaths/min, p = 0.031). A generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) revealed a significant Group × Time interaction (p = 0.003) and a main effect of Time (p = 0.024). Within-group analysis demonstrated significant RR reductions in the facemask group from T0 to T1 (p < 0.001) and from T0 to T2 (p = 0.002), whereas RR in the HFNC group remained stable (

Figure 4).

Table 3.

Time-course changes of Respiratory rate (breath/min). (Value: Mean±SD).

Table 3.

Time-course changes of Respiratory rate (breath/min). (Value: Mean±SD).

| Variable |

|

Group |

|

Analysis for repeated

measures |

Overall

(n=51) |

Mask

(n = 25) |

HFNC

(n = 26) |

p |

Source |

p*

|

Respiratory rate

(breath/min)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| T0 |

14.2±2.5 |

14.7±2.5a |

13.7±2.4a |

.1312

|

Group |

.090 |

| T1 |

11.1±4.1 |

9.8±4.7b |

12.2±3.0a |

.0362

|

Time |

.024 |

| T2 |

12.6±4.9 |

11.0±4.9b |

14.2±4.5a |

.0313

|

Group x Time |

.003 |

4. Discussion

This randomized controlled trial demonstrated that HFNC significantly improved intra-procedural arterial oxygenation compared to a simple facemask during percutaneous liver RFA under MAC. The marked difference in ΔPaO₂ highlights the dynamic effect of HFNC in enhancing alveolar oxygenation beyond baseline levels. However, despite this physiological improvement, the incidence of hypoxia (SpO₂ <95%) did not differ significantly between groups, raising questions about the clinical translation of improved oxygenation.

The lack of difference in hypoxia incidence likely reflects the multifactorial nature of oxygen desaturation during deep sedation. Notably, our institutional protocol mandated predefined interventions when SpO₂ dropped below 95%, which included a triple airway maneuver to rapidly restore oxygen saturation. These early responses may have mitigated desaturation severity and reduced between-group differences. In fact, most desaturation events resolved promptly without escalation to invasive support; only two patients required manual ventilation, and none required intubation. Taken together, these observations imply that upper airway obstruction, rather than inadequate oxygen delivery, may be a dominant cause of hypoxia during MAC. Glossoptosis induced by sedation, especially in the supine position with opioid co-administration, can precipitate airway collapse and compromise ventilation despite high FiO₂ delivery [

18,

19]. This is consistent with previous observations that HFNC improves oxygenation but may not prevent desaturation when upper airway patency is lost [

6,

7].

Although HFNC theoretically offers continuous positive airway pressure (PEEP)-like effects through high flow rates, the flow setting of 30 L/min in our study was likely insufficient to generate clinically meaningful airway pressure. Prior studies indicate that flow rates ≥40–60 L/min are required to produce measurable PEEP and facilitate alveolar recruitment [

20,

21]. However, higher flows were not feasible during RFA due to patient discomfort and interference with procedural accuracy. Therefore, while this moderate flow setting reflects real-world procedural constraints, it may have limited the physiological potential of HFNC. Still, the significant PaO₂ improvement observed in the HFNC group suggests enhanced oxygenation even without optimal PEEP. Another consideration is the role of gas reabsorption atelectasis associated with high FiO₂ delivery. Deep sedation and supine positioning predispose patients to alveolar collapse, and the administration of 100% oxygen via HFNC may exacerbate this through nitrogen washout and resorption. This phenomenon may counteract the benefits of increased FiO₂ and help explain the unchanged incidence of hypoxia [

22].

Although the observed difference in severe hypoxia (11.5% in the HFNC group vs. 24.0% in the facemask group) corresponds to a risk ratio of 0.48, the wide 95% CI (0.13–1.72) reflects substantial uncertainty. While not statistically significant, the trend toward reduced severe hypoxia in the HFNC group may be clinically relevant and warrants further evaluation in larger, adequately powered studies.

Moreover, the FiO₂ delivered via HFNC is theoretically fixed but may be diluted by ambient air due to mouth breathing or irregular respiratory patterns, particularly under sedation. Studies have shown that FiO₂ dilution increases with open-mouth breathing and high inspiratory flow demands, potentially limiting effective oxygen delivery [

20,

23]. In our study, although we assumed FiO₂ values of 1.0 (HFNC) and 0.5 (facemask) for P/F ratio calculations, these estimates are subject to variability and should be interpreted cautiously.

Interestingly, RR remained more stable in the HFNC group throughout the procedure. This contrasts with the facemask group, which exhibited a reduction in RR that persisted post-procedurally. A stable RR is clinically meaningful, as irregular or suppressed respiratory patterns may lead to hypoventilation and hypoxemia. While sedation level and opioid dosing were equivalent across groups, the observed difference may reflect the physiological benefits of HFNC, such as reduced inspiratory workload and improved comfort [

24,

25,

26].

Despite this, we observed no significant difference in arterial PaCO₂ levels between groups. This aligns with previous reports in settings such as bronchoscopy, thoracic surgery, and COPD care, where HFNC had minimal impact on PaCO₂ due to its limited effect on minute ventilation [

11,

13,

23,

27,

28,

29,

30]. While HFNC can flush out nasopharyngeal dead space and aid CO₂ elimination, deep sedation-induced hypoventilation likely blunts its effectiveness in this context [

26,

31]. Patient satisfaction, assessed using the validated ISAS, was similarly high in both groups, suggesting that the method of oxygen delivery did not negatively affect patient experience under deep sedation. The lack of difference in satisfaction may be explained by several factors. Although previous studies have demonstrated improved comfort with HFNC compared to noninvasive ventilation or other oxygen delivery methods [

31,

32], the large-bore nasal cannula may have caused mild discomfort in our patients. Moreover, the relatively short procedural duration and the use of deep sedation likely reduced patients’ awareness of external stimuli, making it difficult for them to perceive differences between oxygen delivery methods. These factors, in combination, may have contributed to the absence of a measurable difference in satisfaction between groups.

This study has several limitations. First, the small sample size was powered only for the primary outcome (PaO₂) and not for secondary outcomes such as hypoxia, ΔP/F ratio, ΔPaCO₂ or satisfaction. Post-hoc power analysis indicated that the statistical power for these variables was insufficient (e.g., 11.1% for hypoxia, 5.1% for ΔPaCO₂), introducing the possibility of type II error and limiting definitive conclusions. Second, ABGA was collected at a fixed intra-procedural time point rather than during actual desaturation events. This limits its utility in assessing real-time respiratory compromise and weakens correlation with SpO₂-based hypoxia. Future studies should consider transcutaneous gas monitoring or real-time ABG sampling during desaturation episodes to better capture dynamic gas exchange. Lastly, although we assumed an FiO₂ of 0.5 for the facemask and 1.0 for the HFNC group based on conventional estimates, interindividual variability in FiO₂ delivery remains a limitation. Our study aimed to evaluate whether HFNC, which generally provides higher and more consistent FiO2, improves oxygenation compared to standard oxygen therapy commonly used during deep sedation. However, given the practical limitations of HFNC application during liver RFA, future studies comparing HFNC with other high-flow oxygen delivery methods, such as non-rebreather masks, may help identify more effective alternatives.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, HFNC improved intra-procedural arterial oxygenation and stabilized respiratory rate in patients undergoing liver RFA under MAC, despite no observed differences in clinical endpoints such as hypoxia incidence or patient satisfaction. These findings support the physiological utility of HFNC in this setting and highlight the need for further studies examining optimized flow rates, individualized FiO₂ delivery, and patient subgroups at higher risk of desaturation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.-W.J. and J.-P.Y.; methodology, K.-W.J.; software, H.P.; validation, J.-U.Y. and H.P.; formal analysis, K.-W.J. and J.-P.Y.; investigation, J.-P.Y. and G.W.K.; resources, J.-U.Y.; data curation, G.W.K.; writing—original draft preparation, J.-P.Y.; writing—review and editing, K.-W.J.; visualization, K.-W.J. and J.-P.Y.; supervision, K.-W.J.; project administration, J.-P.Y.; funding acquisition, J.-P.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the 2024 research grant from Pusan National University Yangsan Hospital. No external funding was received.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This prospective, randomized, controlled study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Asan Medical Center (approval number: 2021-0714, 13/05/2021) and registered at the Clinical Research Information Service (registration number: KCT0006221, 17/05/2021). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to enrollment. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Editage (

www.editage.co.kr) for editing and reviewing this manuscript for the English language.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| RFA |

Radiofrequency ablation |

| MAC |

Monitored anesthesia care |

| HFNC |

High-flow nasal cannula |

| FiO2

|

Fraction of inspired oxygen |

| PEEP |

Positive end-expiratory pressure |

| SpO2

|

Peripheral oxygen saturation |

| PaO2

|

Arterial oxygen partial pressure |

| PaCO2

|

Arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide |

| RR |

Respiratory rate |

| BIS |

Bispectral index |

| ABGA |

Arterial blood gas analysis |

| P/F |

Ratio of arterial partial pressure of oxygen to the fraction of inspired oxygen |

| ISAS |

Iowa Satisfaction with Anesthesia Scale |

| ANCOVA |

Analysis of covariance |

| COPD |

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| CI |

Confidence interval |

References

- Tatli, S.; Tapan, U.; Morrison, P.R.; Silverman, S.G. Radiofrequency ablation: Technique and clinical applications. Diagn Interv Radiol 2012, 18, 508–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGhana, J.P.; Dodd, G.D., 3rd. Radiofrequency ablation of the liver: Current status. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2001, 176, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, H.; Kim, D.; Kim, D.K.; Chung, I.S.; Bang, Y.J.; Kim, K.; Kim, M.; Choi, J.W. Comparison of respiratory effects between dexmedetomidine and propofol sedation for ultrasound-guided radiofrequency ablation of hepatic neoplasm: A randomized controlled trial. J Clin Med 2021, 10, 3040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, K.; Taniki, N.; Kanazawa, R.; Shimizu, M.; Ishii, S.; Ohama, H.; Takawa, M.; Nagamatsu, H.; Imai, Y.; Shiina, S. Efficacy and safety of deep sedation in percutaneous radiofrequency ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Adv Ther 2019, 36, 344–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisi, D.; Fanelli, A.; Tosi, M.; Nuzzi, M.; Fanelli, G. Monitored anesthesia care. Minerva Anestesiol 2005, 71, 533–538. [Google Scholar]

- Kimura, S.; Sone, M.; Sugawara, S.; Itou, C.; Ozawa, M.; Sato, T.; Matsui, Y.; Arai, Y.; Kusumoto, M. Safety of propofol sedation administered by interventional radiologists for radiofrequency ablation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Jpn J Radiol 2024, 42, 1290–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhananker, S.M.; Posner, K.L.; Cheney, F.W.; Caplan, R.A.; Lee, L.A.; Domino, K.B. Injury and liability associated with monitored anesthesia care: A closed claims analysis. Anesthesiology 2006, 104, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spoletini, G.; Alotaibi, M.; Blasi, F.; Hill, N.S. Heated humidified high-flow nasal oxygen in adults: Mechanisms of action and clinical implications. Chest 2015, 148, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, L.; Wei, M.; Zhao, B.; Wang, X.; Pan, Z.; Tian, J.; Yu, W.; Su, D. High-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy and hypoxia during gastroscopy with propofol sedation: A randomized multicenter clinical trial. Gastrointest Endosc 2019, 90, 591–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renda, T.; Corrado, A.; Iskandar, G.; Pelaia, G.; Abdalla, K.; Navalesi, P. High-flow nasal oxygen therapy in intensive care and anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth 2018, 120, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, N.; Ng, I.; Nazeem, F.; Lee, K.; Mezzavia, P.; Krieser, R.; Steinfort, D.; Irving, L.; Segal, R. A randomised controlled trial comparing high-flow nasal oxygen with standard management for conscious sedation during bronchoscopy. Anaesthesia 2018, 73, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheahan, C.G.; Mathews, D.M. Monitoring and delivery of sedation. Br J Anaesth 2014, 113 Suppl 2, ii37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Lee, C.Y.; Lee, K.; Kim, N.; Lee, S.; Oh, Y.J. Comparison of high-flow nasal oxygenation and standard low-flow nasal oxygenation during rigid bronchoscopy: A randomized controlled trial. Korean J Anesthesiol 2025, 78, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dexter, F. Iowa satisfaction with anesthesia scale. Korean J Anesthesiol 2012, 62, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohn HM, Ryu JH. Monitored anesthesia care in and outside the operating room. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2016;69(4):319-26.

- Heinrich, S.; Horbach, T., BS; Prottengeier, J. AI, Schmidt J. Benefits of heated and humidified high flow nasal oxygen for preoxygenation in morbidly obese patients undergoing bariatric surgery: A randomized controlled study. J Obes Bariatrics 2014, 1, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Ghoshal, A.G. Hypoxemia and oxygen therapy. J Assoc Chest Physicians 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, D.R.; Platt, P.R.; Eastwood, P.R. The upper airway during anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth 2003, 91, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishimura, M. High-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy in adults: Physiological benefits, indication, clinical benefits, and adverse effects. Respir Care 2016, 61, 529–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parke, R.L.; Eccleston, M.L.; McGuinness, S.P. The effects of flow on airway pressure during nasal high-flow oxygen therapy. Respir Care 2011, 56, 1151–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucangelo, U.; Vassallo, F.G.; Marras, E.; Ferluga, M.; Beziza, E.; Comuzzi, L.; Berlot, G.; Zin, W.A. High-flow nasal interface improves oxygenation in patients undergoing bronchoscopy. Crit Care Res Pract 2012, 2012, 506382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, C.C.; Liang, P.C.; Chuang, Y.H.; Huang, Y.J.; Lin, P.J.; Wu, C.Y. Effects of high-flow nasal oxygen during prolonged deep sedation on postprocedural atelectasis: A randomised controlled trial. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2020, 37, 1025–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Huang, D.; Luo, J.; Liang, Z.; Li, J. The use of high-flow nasal cannula in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease under exacerbation and stable phases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart Lung 2023, 60, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mündel, T.; Feng, S.; Tatkov, S.; Schneider, H. Mechanisms of nasal high flow on ventilation during wakefulness and sleep. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2013, 114, 1058–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rittayamai, N.; Tscheikuna, J.; Rujiwit, P. High-flow nasal cannula versus conventional oxygen therapy after endotracheal extubation: A randomized crossover physiologic study. Respir Care 2014, 59, 485–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauri, T.; Turrini, C.; Eronia, N.; Grasselli, G.; Volta, C.A.; Bellani, G.; Pesenti, A. Physiologic effects of high-flow nasal cannula in acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017, 195, 1207–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.L.; Hung, M.H.; Chen, J.S.; Hsu, H.H.; Cheng, Y.J. Nasal high-flow oxygen therapy improves arterial oxygenation during one-lung ventilation in non-intubated thoracoscopic surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2018, 53, 1001–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Du, Y.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, H.; Jun, L.; Wang, Z.; Lin, M.; Ni, F.; Li, X.; Tan, H.; et al. High-flow nasal cannula oxygen versus conventional oxygen for hypercapnic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Respir J 2021, 15, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, L.; Xie, C.; Zhao, N. Effect of high-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A meta-analysis. J Clin Nurs 2022, 31, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.; Khanna, P.; Chowdhury, S.R.; Haritha, D.; Sarkar, S. The impact of high-flow nasal cannula vs other oxygen delivery devices during bronchoscopy under sedation: A systematic review and meta-analyses. Indian J Crit Care Med 2022, 26, 1131–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roca, O.; Hernández, G.; Díaz-Lobato, S.; Carratalá, J.M.; Gutiérrez, R.M.; Masclans, J.R. ; Spanish Multidisciplinary Group of High Flow Supportive Therapy in Adults (HiSpaFlow). Current evidence for the effectiveness of heated and humidified high flow nasal cannula supportive therapy in adult patients with respiratory failure. Crit Care 2016, 20, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitra, S.; Som, A.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Arora, M.K.; Baidya, D.K. Comparison of high-flow nasal oxygen therapy with conventional oxygen therapy and noninvasive ventilation in adult patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure: A meta-analysis and systematic review. J Crit Care 2016, 35, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).