Submitted:

22 May 2025

Posted:

23 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

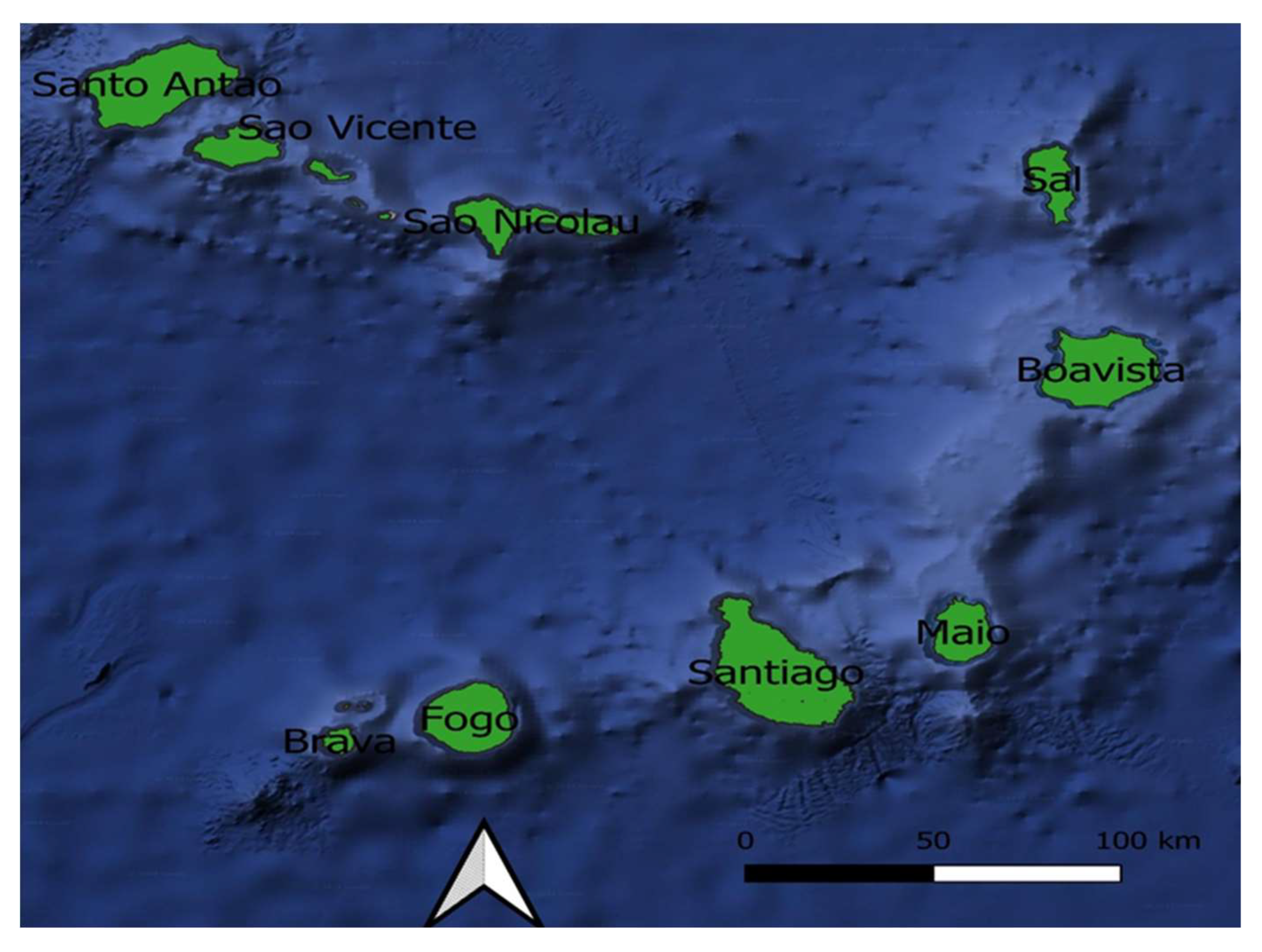

2.1. Studied Area

2.2 Data Collection

2.3. Climate data

Aridity Index

2.4. Water Use

- (i)

- Water withdrawal for agriculture as a percentage of total renewable water resources (%);

- (ii)

- Water use efficiency in irrigated agriculture, which is calculated as the agricultural value added per agricultural water use (US$/m³);

- (iii)

- =Contribution of the agricultural sector to water stress, which is calculated as the proportion of agricultural sectoral withdrawals over total freshwater withdrawals (%);

- (iv)

- Percentage of the area equipped for irrigation using groundwater (%);

- (v)

- Percentage of the area equipped for irrigation using surface water (%);

- (vi)

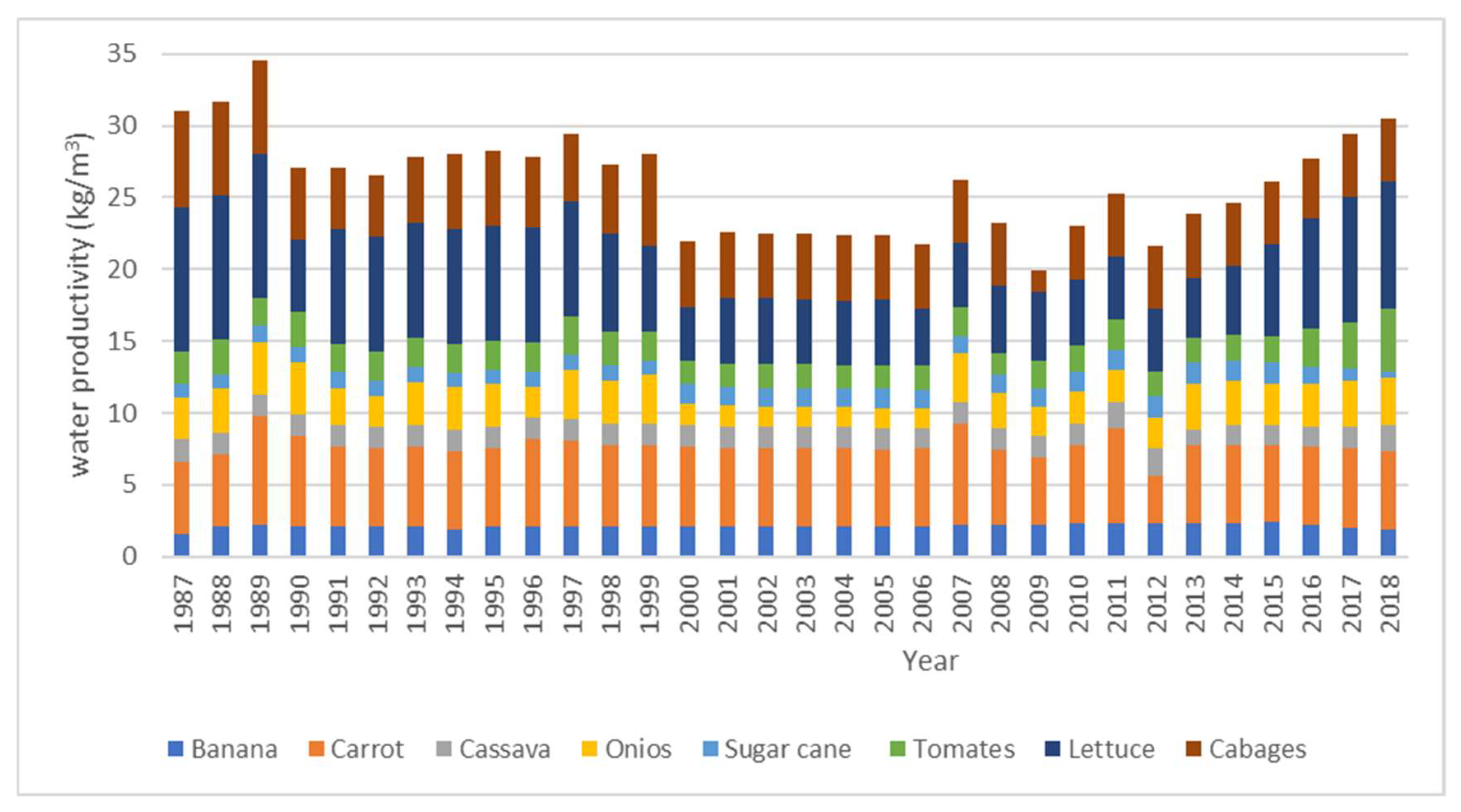

- Water productivity per agricultural crop (kg/m³), calculated using the following equation WP = Production obtained (kg) / water supplied to plants (m³).

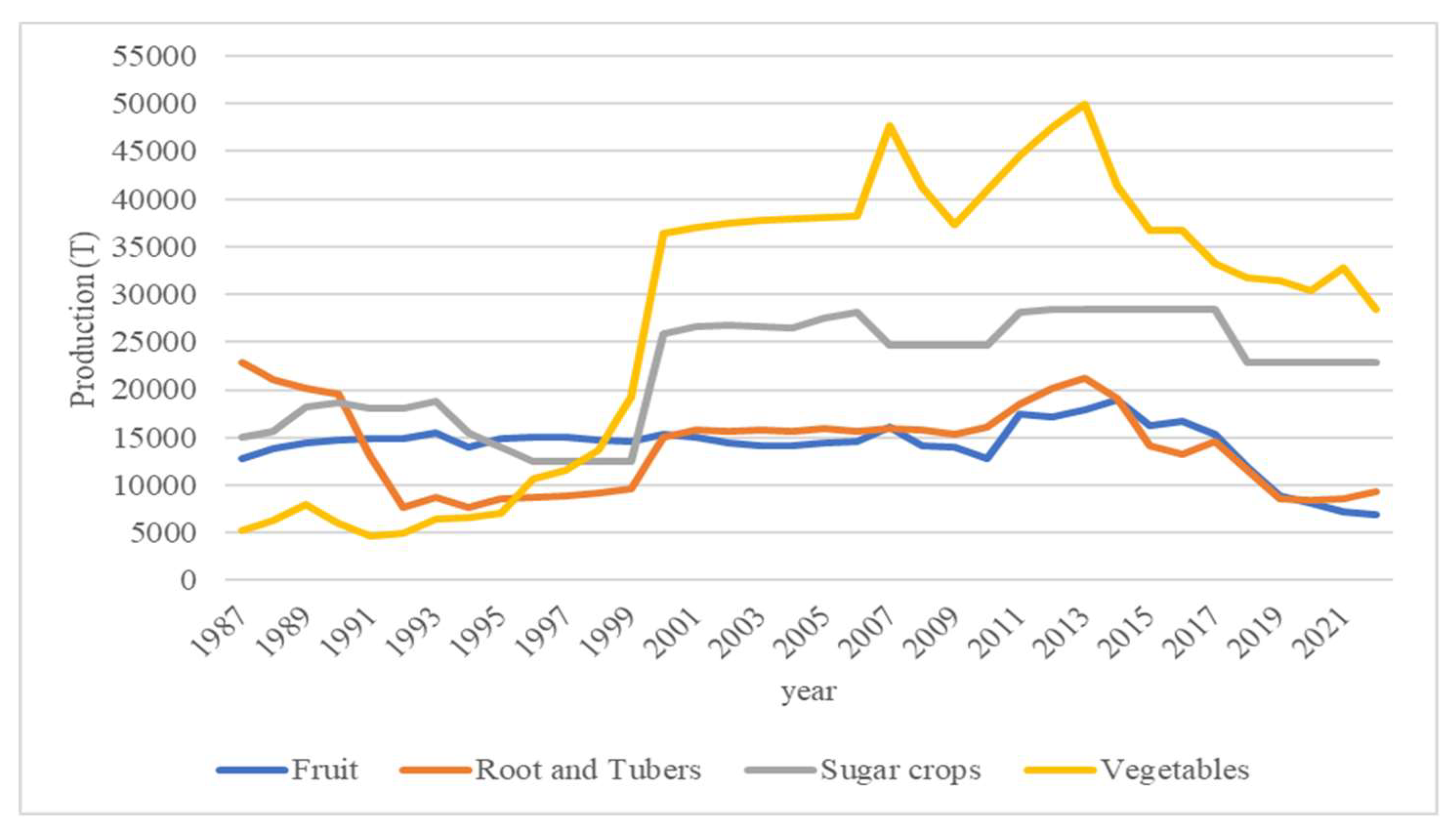

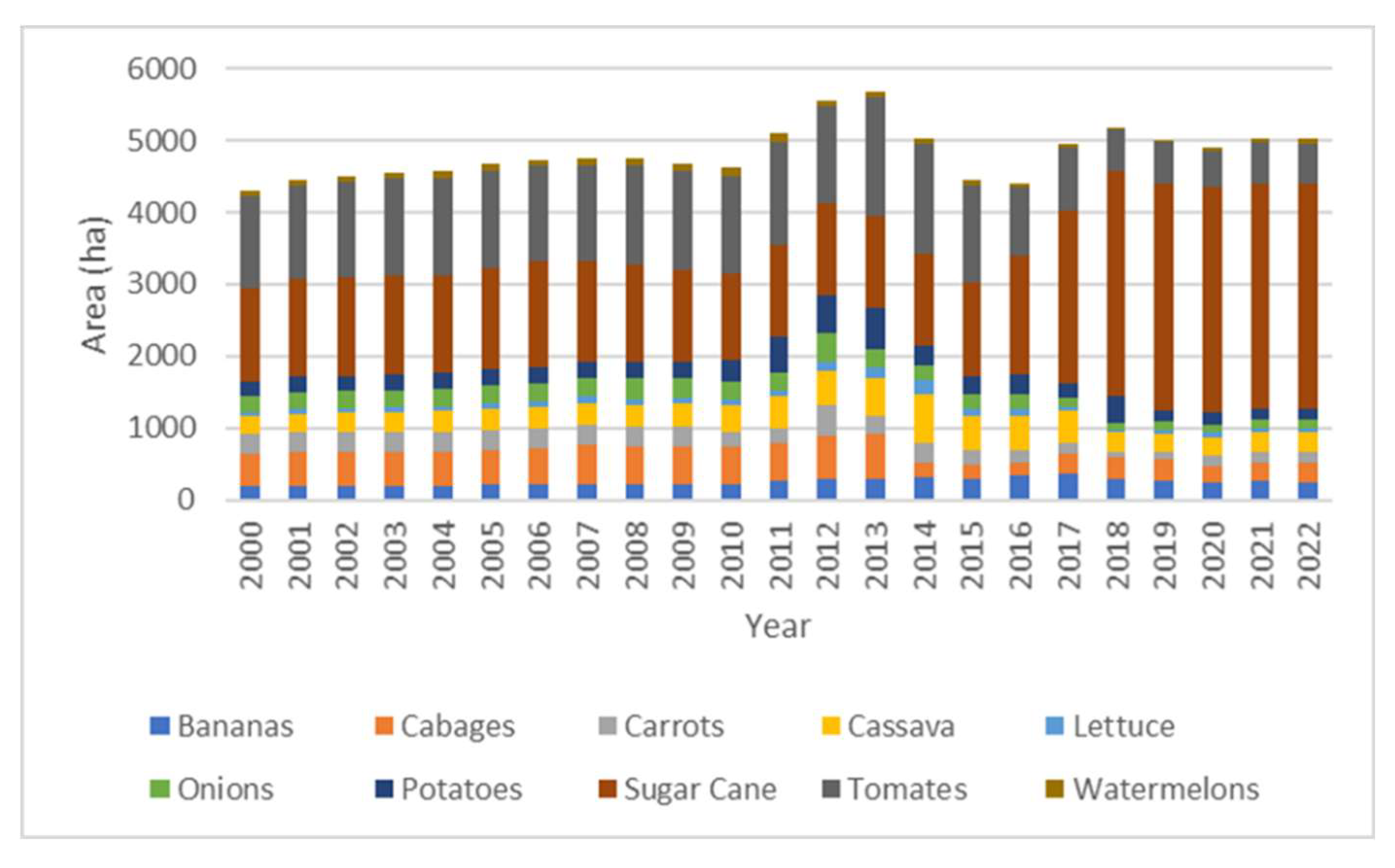

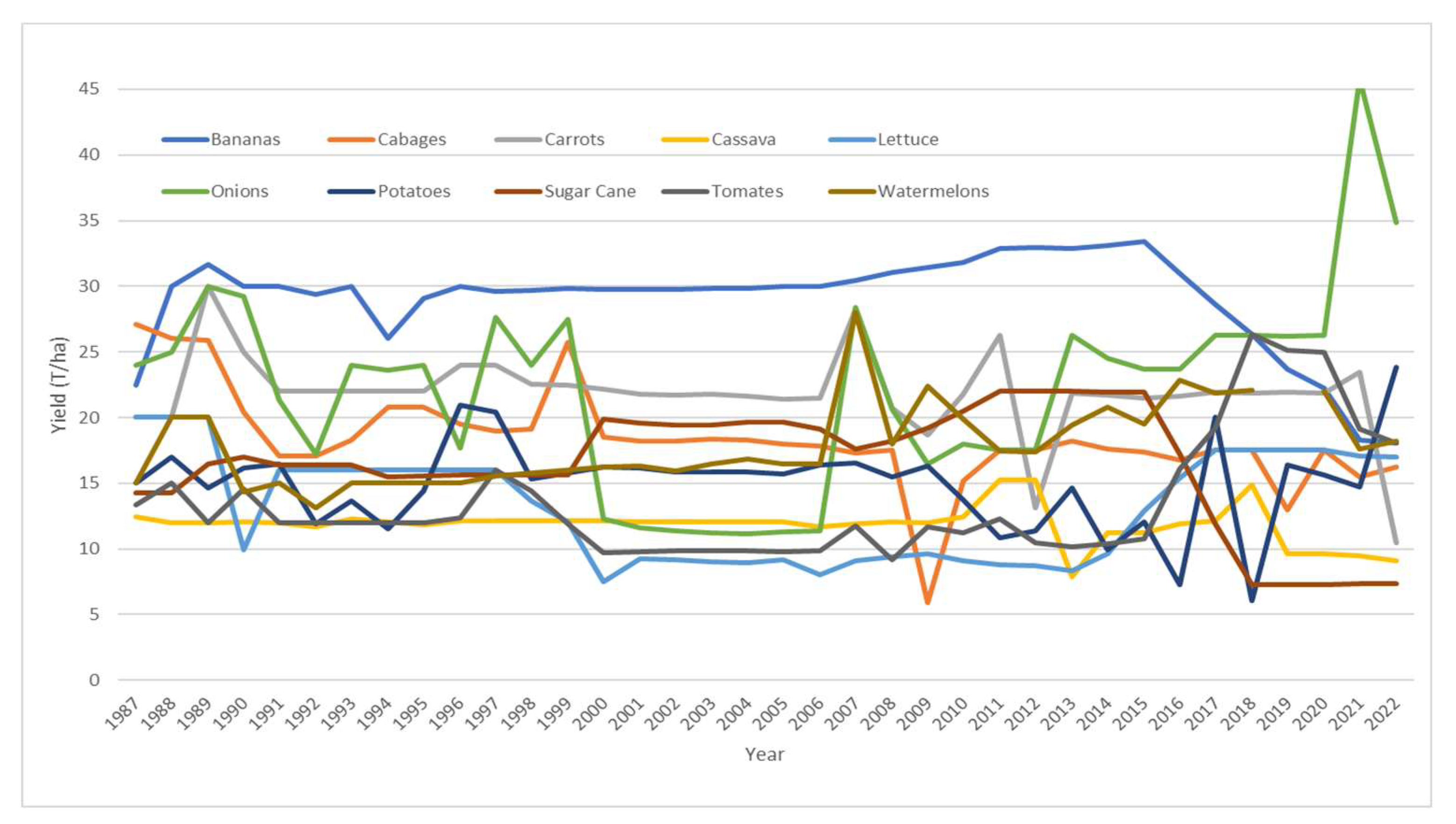

2.5. Crop Evolution and Production

3. Results & Discussion

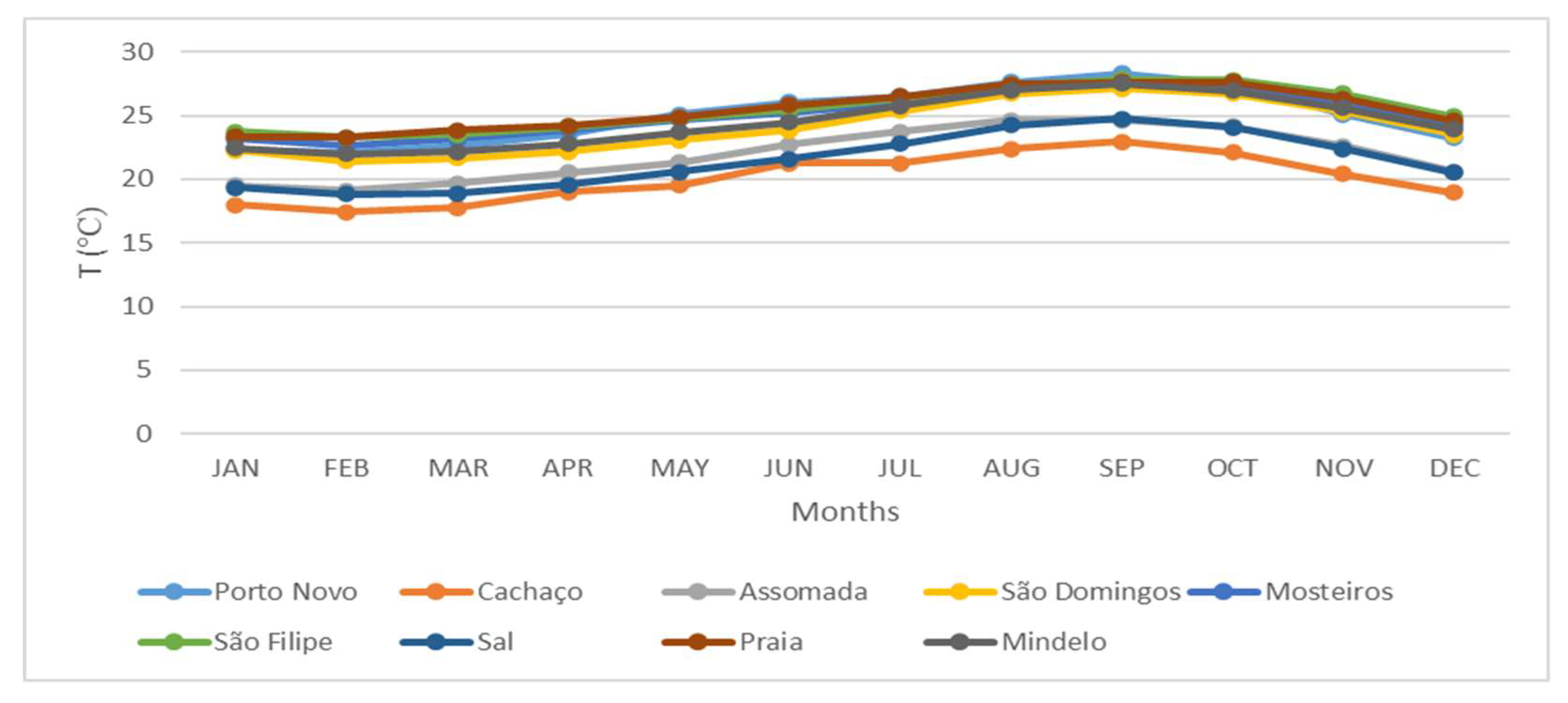

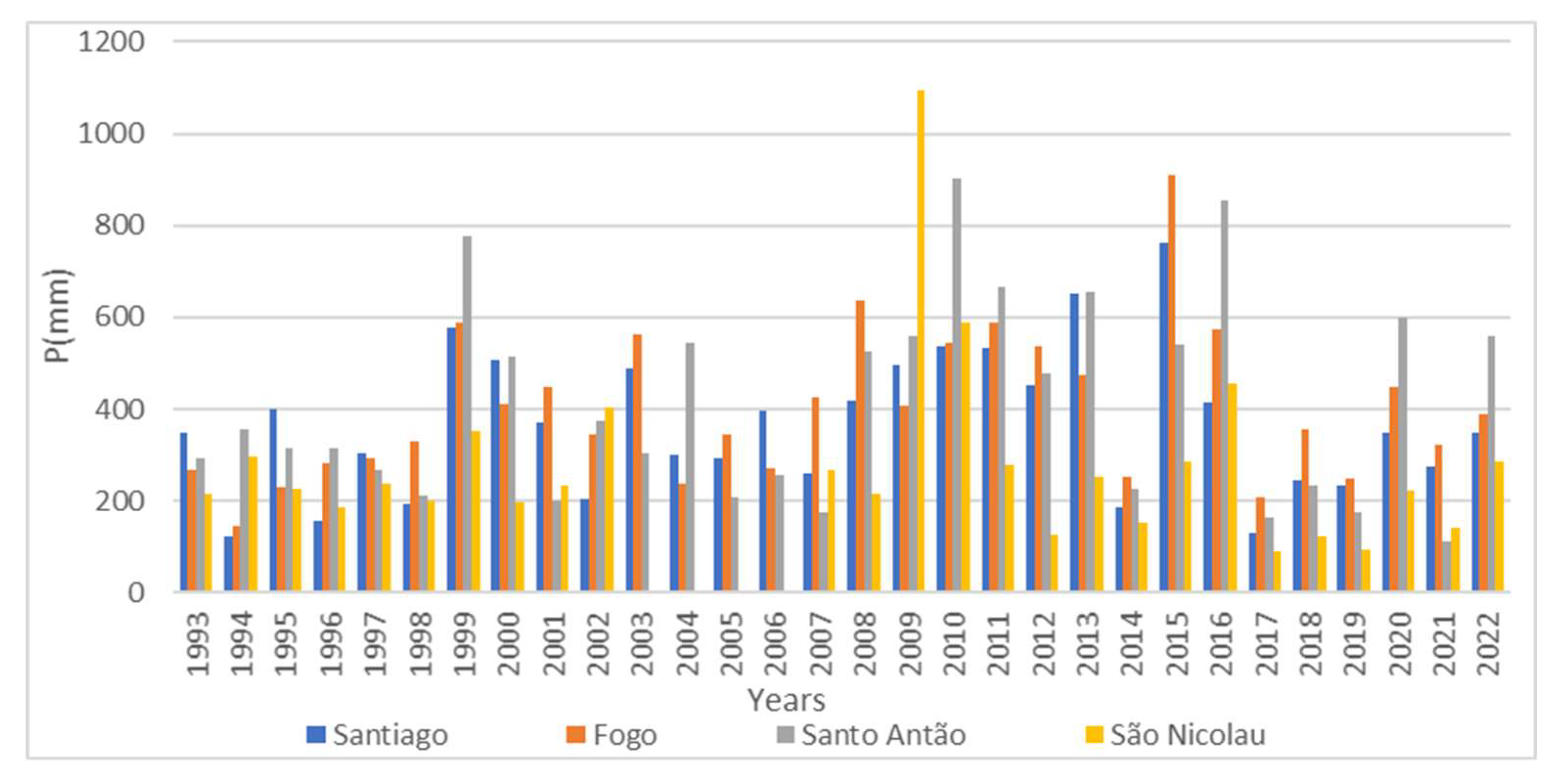

3.1. Climate Characterization

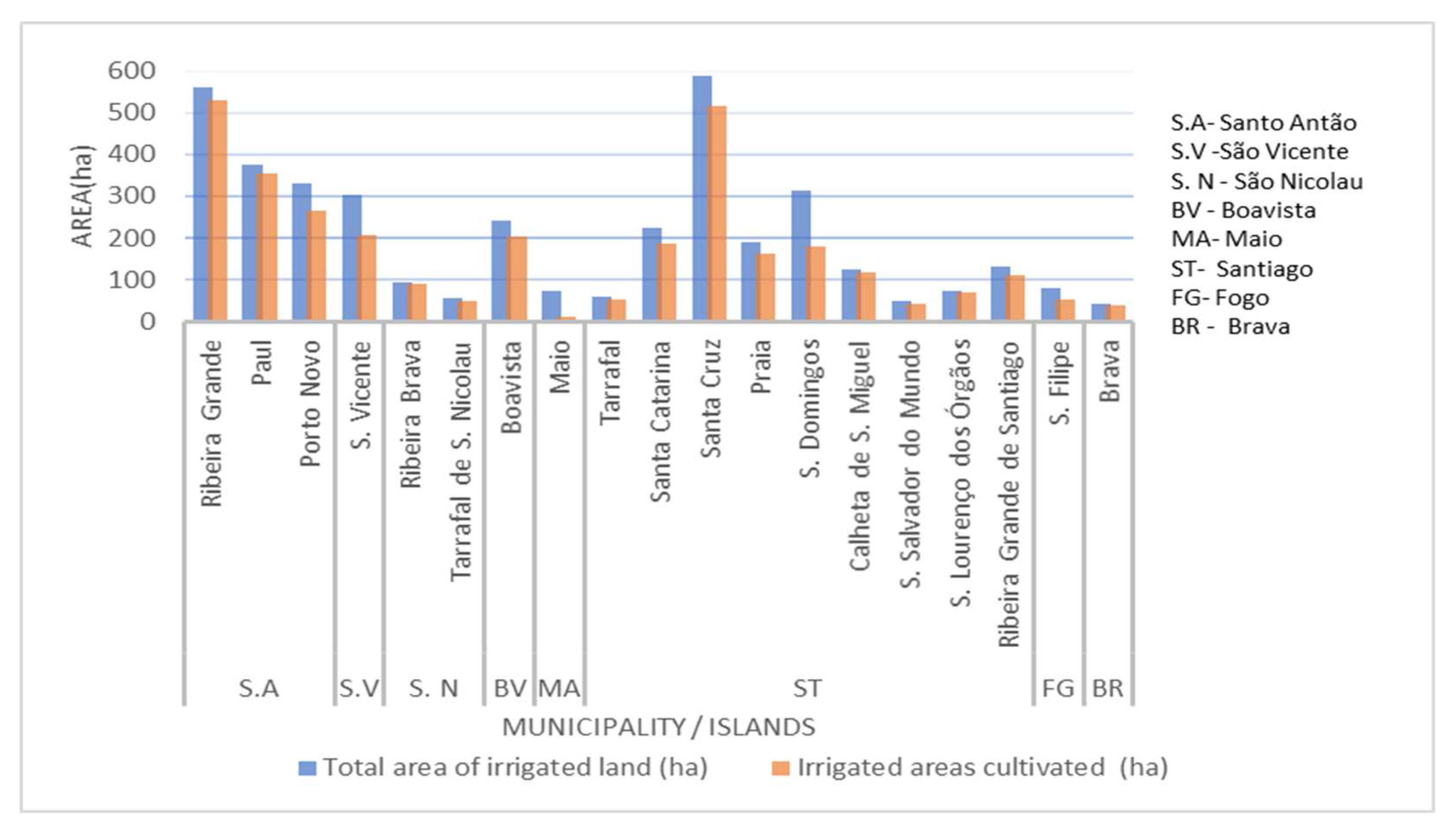

3.2. Characterization of Irrigated Agriculture in Cape Verde

3.3. Characterization of Irrigation Systems

3.4. Challenges in Water Management in Cape Verde and Strategies Adopted to Increase Water Availability and Efficient Water Use

- a)

- Mobilization of water

- b)

- Alternative water sources

- c)

- Irrigation management

3.5. Foreign Experiences That can be Adopted in Cape Verde

3.6. Crop Irrigation Requirements and Water Management

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Godfray, H.C.J.; Crute, I.R.; Haddad, L.; Lawrence, D.; Muir, J.F.; Pretty, J.; Robinson, S.; Thomas, S.M.; Toulmin, C. Food security: The challenge of feeding 9 billion people. Science 2010, 327, 812–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paz, V.P. da S.; Teodoro, R.E.F.; Mendonça, F.C.. Recursos hídricos, agricultura irrigada e meio ambiente. Revista Brasileira de Engenharia Agrícola e Ambiental, 2000, 4(3), 465–473. Campina Grande, PB: DEAg/UFPB.

- Carter, R.; Kay, M.; Weatherhead, K. Water Losses in Smallholder Irrigation Schemes. Agricultural Water Management 1999, 40, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.C. Importância da Horticultura para a Segurança Alimentar em Cabo Verde – Estudo de Caso na Ilha do Fogo. Dissertação para a obtenção do Grau de Mestre em Engenharia Agronómica, Universidade Técnica de Lisboa, Instituto Superior de Agronomia: Lisboa, 2009. https://www.repository.utl.pt/handle/10400.5/617.

- Monteiro, M.F. Segurança Alimentar em Cabo Verde – Estudo de Caso do Concelho de Ribeira Grande, Ilha de Santo Antão. Master’s Thesis, Instituto Superior de Agronomia, Universidade Técnica de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal, 2012. Available online: https://www.repository.utl.pt/handle/10400.5/5314.

- Coreia, A.M.N.G. A Água como um dos Fatores de Desenvolvimento do Continente Africano no Próximo Milênio. In População, Ambiente e Desenvolvimento em África; Instituto Superior de Ciências Sociais e Políticas, Universidade Técnica de Lisboa, Lisboa, 2001; pp. 159–174. https://abrir.link/AYOeX.

- Gomes, A.M. Hidrogeologia e Recursos Hídricos da Ilha de Santiago (Cabo Verde). Ph.D. Dissertation, Universidade de Aveiro, Aveiro, Portugal, 2007. Available online: https://ria.ua.pt/handle/10773/2743.

- Shanahan, T.M.; Overpeck, J.T.; Anchukaitis, K.J.; Beck, J.W.; Cole, J.E.; Dettman, D.L.; Peck, J.A.; Scholz, C.A.; King, J.W. Atlantic Forcing of Persistent Drought in West Africa. Science 2009, 324, 377–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mannaerts, C.M.; Gabriels, D. Rainfall erosivity in Cape Verde. Soil Tillage Res. 2000, 55, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonso, M.B. Rentabilidade Financeira de Culturas Hortícolas nos Sistemas de Rega Gota-a-gota e Tradicional no Conselho de Santa Cruz. Relatório para Obtenção do Grau de Bacharel em Produção e Proteção das Culturas, INIDA, Cabo Verde, 2002.

- Shahidian, S.; Serralheiro, R.P.; Serrano, J.; Sousa, A. O Desafio dos Recursos Hídricos em Cabo Verde. 2014. Available online: https://rdpc.uevora.pt/handle/10174/12489.

- Gornall, J.; Betts, R.; Burke, E.; Clark, R.; Camp, J.; Willett, K.; Wiltshire, A. Implications of climate change for agricultural productivity in the early twenty-first century. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2010, 365, 2973–2989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolters, W. Influences on the Efficiency of Irrigation Water Use; International Institute of Land Reclamation and Improvement: Wageningen, Netherlands, 1992; pp. 150–150. ISBN 90-70754-290. [Google Scholar]

- Bos, M.G. Performance Indicators for Irrigation and Drainage. Irrig. Drain. Syst. 1997, 11, 119–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oweis, T.; Pala, M.; Ryan, J. Stabilizing Rainfed Wheat Yields with Supplemental Irrigation and Nitrogen in a Mediterranean Climate. Agron. J. 1998, 90(5), 672–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Oweis, T.Y.; Garabet, S.; Pala, M. Water-use efficiency and transpiration efficiency of wheat under rain-fed conditions and supplemental irrigation in a Mediterranean-type environment. Plant Soil 1998, 201, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.S.; Qweis, T.; Zairi, A. Irrigation management under water scarcity. Agricultural Water Management 2002, 57, 175–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semedo, J.M. A Ilha de Santiago (Cabo Verde) Génese de um Ecossistema e Identidade Cultural Numa Ilha de Escala Marítima Entre a África, a Europa e as Américas. Palaver 2012, n.1, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MAA—Ministério de Agricultura e Ambiente. Programa Nacional de Investimento Agrícola, Segurança Alimentar e Nutricional; MAA: Praia, Cabo Verde, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Peel, M.C. , Finlayson, B.L., & McMahon, T.A. (2007). Updated world map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification. Hydrology and earth system sciences, 11(5), 1633-1644.

- Instituto Nacional de Meteorologia e Geofísica (INMG). Climatic data for Cabo Verde; Data provided via personal communication, 2023.

- Shahidian, S.; Serralheiro, R.; Teixeira, J.; Serrano, J. Parametric Calibration of the Hargreaves-Samani Equation for Use at New Locations. Hydrol. Process. 2013, 27, 605–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sequeira, E.; de Sousa, P.L.; Russo, A. Assessment of Water Requirements for Horticultural Crops in Arid Regions. Nutrition & Food Science 2020, 10(2). [CrossRef]

- Lopes, I.; Leal, B.G. Índice de aridez e tendência à desertificação para estações meteorológicas nos estados de Bahia e Pernambuco. Revista Brasileira de Climatologia 2015, 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. WaPOR—FAO’s Portal to Monitor Water Productivity through Open Access of Remotely Sensed Derived Data. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Available online: https://data.apps.fao.org/wapor/?lang=en (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- MAA—Ministério de Agricultura e Ambiente. Recenseamento Geral da Agricultura 2015; Dados Gerais; MAA: Praia, Cabo Verde, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- INGRH—Instituto Nacional de Gestão dos Recursos Hídricos. Plano de ação Nacional Para a Gestão Integrada dos Recursos Hídricos (PAGIRE); Série—N° 45 2° SUP; «B. O.» Da República de Cabo Verde: Praia, Cabo Verde. 2010.

- MAA/INMG—Ministério de Agricultura e Ambiente, Instituto Nacional de Meteorologia e Geofísica. Estudos Sectoriais Vulnerabilidade e Adaptação às Mudanças Climáticas em Cabo Verde; MAA: Praia, Cabo Verde, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. AQUASTAT Dissemination System. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2025. Available online: https://data.apps.fao.org/aquastat/?lang=en&share=f-17792a7a-a61e-4725-891a-7b910e401d04 (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- FAO & UN-Water. 2024. Progress on the level of water stress – Mid-term status of SDG Indicator 6.4.2 and acceleration needs, with special focus on food security - 2024. Rome, FAO. [CrossRef]

- Organização das Nações Unidas para Agricultura e Alimentação (FAO). FAOSTAT.; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2024; Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#compare.

- INE- Instituto Nacional de Estatística. Anuário Estatístico Cabo Verde 2017; Instituto Nacional de Estatística: Praia, Cape Verde, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, V.S. The Impacts of School Closures on Small Family Farmers due to Covid-19 in Cabo Verde. Young African Researchers in Agriculture (YARA) Working Paper 2021, 25, 1–10.

- Mendes, A.A.F. Análise Comparativa de Rentabilidade de Algumas Culturas de Regadio na Ilha de Santiago em Cabo Verde. Master’s Thesis, Instituto Superior de Agronomia, Universidade Técnica de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal, 2009. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/38680545.pdf.

- Ministério de Agricultura e Ambiente de Cabo Verde. Governo aprova o programa de subvenção aos agricultores para instalação de sistema de rega gota-a-gota. Notícias do MAA, 21 Mar. 2023. Available online: https://maa.gov.cv/index.php/noticias/366-governo-aprova-o-programa-subvencao-aos-agricultores-para-instalacao-de-sistema-de-rega-gota-a-gota (accessed on 14 May 2024).

- Moreno, A.M.P. P. Modelação Hidrológica e de Rega para Condições de Escassez Visando a Gestão da Água em Santiago Cabo Verde. Ph.D. Dissertation, Instituto Superior de Agronomia, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal, 2013. Available online: https://www.repository.utl.pt/handle/10400.5/6149.

- Pina, A.F.L. L. Hidroquímica e Qualidade das Águas da Ilha de Santiago—Cabo Verde. Ph.D. Dissertation, Universidade de Aveiro, Aveiro, Portugal, 2009; p. 232. Available online: https://ria.ua.pt/handle/10773/4840.

- Mendoza-Grimón, V.; Amorós, R.; Fernández-Vera, J.R.; Hernádez-Moreno, J.M.; Palacios-Díaz, M. d. P. Effect of Different Water Quality on the Nutritive Value and Chemical Composition of Sorghum bicolor Payenne in Cape Verde. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sequeira, E.A.C.; Baptista, I.; Ferreira, V.S. Otimização da Produtividade da Água e da Fertilização Azotada na Cultura do Tomate em Cabo Verde. Brazilian Journal of Animal and Environmental Research 2024, 7(1), 633–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, M.; Penha, A.M.; Novais, M.H.; Landim, L.; Victória, S.S.; Morales, E.A.; Barbosa, L.G. Some Observations on Phytoplankton Community Structure, Dynamics and Their Relationship to Water Quality in Five Santiago Island Reservoirs, Cape Verde. Water 2021, 13, 2888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landim, L.; António, F.; Silva, S.V.; Morales, E.A.; Novais, M.H.; Penha, A.; Morais, M. Caracterização Físico-Química e Biológica de Cinco Albufeiras da Ilha de Santiago, Cabo Verde. Repositório da Universidade de Évora, 2018.

- Araujo, A.A.; Hernandez, R.; Fonseca, R.; Matos, J. Estimating Sedimentation Rate on Poilão Dam (Santiago Island, Cape Verde). Comunicações Geológicas 2014, 101(3). Available online: https://dspace.uevora.pt/rdpc/handle/10174/17491.

- Ramos, K.R. Mudanças Climáticas e os Desafios do Setor dos Recursos Hídricos em Cabo Verde. Revista Ibero-Americana de Ciências Ambientais 2014, 5, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Grimón, V.; Fernández-Vera, J.R.; Hernández-Moreno, J.M.; Palacios-Díaz, M.d.P. Sustainable Irrigation Using Non-Conventional Resources: What Has Happened after 30 Years Regarding Boron Phytotoxicity? Agronomy 2021, 11, 1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MAA—Ministério de Agricultura e Ambiente. Plano Nacional de Adaptação de Cabo Verde; Direção Nacional do Ambiente: Praia, Cabo Verde, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- FAO (2025). Drought within an ocean. Food and Agriculture Organization, Rome. Available online: https://www.fao.org/newsroom/story/drought-within-an-ocean/en (accessed on 13 March 2025).

- Sjöstedt, M.; Povitkina, M. Vulnerability of Small Island Developing States to Natural Disasters: How Much Difference Can Effective Governments Make? Environ. Dev. 2016, 16, 82–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romeiras, M.M.; Catarino, S.; Gomes, I.; Fernandes, C.; Costa, J.C.; Caujapé-Castells, J.; Duarte, M.C. IUCN Red List Assessment of the Cape Verde Endemic Flora: Towards a Global Strategy for Plant Conservation in Macaronesia. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2016, 180, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, S.; Felemban, A.; Abdelrahim, A.; Al-Dakhil, M. Agricultural and Technology-Based Strategies to Improve Water-Use Efficiency in Arid and Semiarid Areas. Water 2024, 16, 1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Trinidad, J.; Júnez-Ferreira, H.E.; Bautista-Capetillo, C.; Ávila Dávila, L.; Robles Rovelo, C.O. Melhorando a Eficiência do Uso da Água e a Produtividade Agrícola: Um Caso de Aplicação em uma Região Semiárida Modernizada no Centro-Norte do México. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbat, G.; Masseroni, D. The Use and Management of Agricultural Irrigation Systems and Technologies. Agriculture 2024, 14, 236. [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Grimón, V.; Hernández-Moreno, J.M.; Palacios-Díaz, M.D.P. Improving Water Use in Fodder Production. Water 2015, 7, 2612–2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvez-Méndez, S.J.; Padrón-Armas, I.; Mahouachi, J. Irrigation Management Strategies through the Combination of Fresh Water and Desalinated Sea Water for Banana Crops in El Hierro, Canary Islands. Water Reuse 2021, 11(3), 464–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do Nascimento, N.R.; Salvado, L.R.B.S.; Borges, F.F. Low Cost System Based on Textile and Plastic Waste for Underground Irrigation in the Brazilian Semi-Arid Region. In Machado, J.; Soares, F.; Veiga, G. (Eds.) Innovation, Engineering and Entrepreneurship. HELIX 2018. Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering, vol. 505. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Gallo, A. Jr.; Odokonyero, K.; Mousa, M.A.A.; Reihmer, J.; Al-Mashharawi, S.; Marasco, R.; Manalastas, E.; Morton, M.J.L.; Daffonchio, D.; McCabe, M.F.; Tester, M.; Mishra, H. Nature-Inspired Superhydrophobic Sand Mulches Increase Agricultural Productivity and Water-Use Efficiency in Arid Regions. ACS Agric. Sci. Technol. 2022, 2(2), 276–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Latitude (º) |

Longitude (º) |

Elevation (m) |

Localities | Island |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17.02 | -25.08 | 22 | Porto Novo | Santo Antão |

| 16.62 | -24.33 | 715 | Cachaço | São Nicolau |

| 15.13 | -23.13 | 482 | Assomada | Santiago |

| 15.04 | -23.47 | 73 | São Domingos | Santiago |

| 15.02 | -24.31 | 81 | Mosteiros | Fogo |

| 14.88 | -24.48 | 174 | São Filipe | Fogo |

| 16.72 | -22.94 | 53.8 | Sal | Sal |

| 14.95 | -23.48 | 94.5 | Praia | Santiago |

| 16.53 | -24.59 | 32 | Mindelo | São Vicente |

| Classification | Aridity Index |

|---|---|

| Humid | AIu ≥1,00 |

| Sub-humid | 0,65<AIu <1,00 |

| Dry sub-humid | 0,50<AIu <0,65 |

| Semi-arid | 0,20<AIu <0,50 |

| Arid | 0,05<AIu <0,20 |

| Hyper-arid | AIu ≤ 0,50 |

| Latitude (º) |

Longitude (º) |

Elevation (m) |

Localities | Island | Termal Amplitude(°C) | PET (mm) |

P (mm) | AIu | Classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17.02 | -25.08 | 22 | Porto Novo | Santo Antão | 6.0 | 1425 | 263 | 0.18 | Arid |

| 16.62 | -24.33 | 715 | Cachaço | São Nicolau | 5.6 | 1069 | 448 | 0.41 | Semi-arid |

| 15.13 | -23.13 | 482 | Assomada | Santiago | 5.5 | 1223 | 282 | 0.23 | Semi-arid |

| 15.04 | -23.47 | 73 | São Domingos | Santiago | 5.5 | 973 | 227 | 0.23 | Semi-arid |

| 15.02 | -24.31 | 81 | Mosteiros | Fogo | 5.0 | 1146 | 366 | 0.32 | Semi-arid |

| 14.88 | -24.48 | 174 | São Filipe | Fogo | 4.5 | 1363 | 154 | 0.11 | Arid |

| 16.72 | -22.94 | 53.8 | Sal | Sal | 5.6 | 1194 | 80 | 0.07 | Arid |

| 14.95 | -23.48 | 94.5 | Praia | Santiago | 4.3 | 1375 | 185 | 0.13 | Arid |

| 16.53 | -24.59 | 32 | Mindelo | São Vicente | 5.5 | 1009 | 134 | 0.13 | Arid |

| Islands | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Santiago | Fogo | Brava | Boavista | Maio | Sal | São Vicente | São Nicolau | Santo Antaão |

| 2018 | 232.48 | 103.65 | 361.69 | 136.7 | 96.12 | 146.38 | 168.56 | 310.39 | 98.27 |

| 2019 | 199.91 | 101.82 | 301.75 | 136.45 | 72.31 | 137.42 | 160.99 | 279.1 | 79.97 |

| 2020 | 286.56 | 150.35 | 384.09 | 139.7 | 128.87 | 143.95 | 194.76 | 317.49 | 127.39 |

| 2021 | 270.22 | 95.21 | 292.97 | 129.96 | 128.05 | 136.58 | 161.69 | 277.32 | 88.02 |

| 2022 | 328.4 | 153.36 | 421.42 | 170.89 | 108.95 | 141.11 | 172.94 | 328.09 | 117.19 |

| 2023 | 351.17 | 195.73 | 498.75 | 124.91 | 131.18 | 136.51 | 170.54 | 301.59 | 129.67 |

| 2024 | 411.03 | 219.55 | 493.5 | 132.6 | 149.81 | 137.39 | 175.18 | 325.91 | 135.55 |

| Islands | Total Agriculture (ha) | Irrigated (ha) | Rainfed (ha) | Mixed Agricultural - Irrigated and Rainfed (ha) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| São Antão | 5246 | 1268 | 3770 | 207 |

| São Vicente | 942 | 302 | 597 | 44 |

| São Nicolau | 1030 | 146 | 854 | 30 |

| Sal | 74 | 2 | 72 | 0 |

| Boavista | 276 | 242 | 34 | 0 |

| Maio | 466 | 73 | 316 | 77 |

| Santiago | 21076 | 1747 | 18880 | 443 |

| Fogo | 6827 | 90 | 6694 | 43 |

| Brava | 520 | 43 | 476 | 1 |

| Cape Verde | 36456 | 3913 | 31692 | 845 |

| Year | Agricultural Water Withdrawal as % of Total Renewable Water Resources (%) | Irrigated Agriculture Water Use Efficiency (US$/m3) | Agricultural Sector Contribution to Water Stress (%) | % of Area Equipped for Irrigation by Groundwater | % of Area Equipped for Irrigation by Surface Water |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 37,73 | 0,071 | 26,64 | 10,35 | 63,26 |

| 2021 | 36,42 | 0,075 | 24,32 | 10,35 | 63,26 |

| 2022 | 34,41 | 0,076 | 23,27 | 10,35 | 63,26 |

| Island | Surface Water (Average Period) |

Groundwater | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gross (Average Period) |

Explorable (Average Period) |

Explorable (Dry Period) |

||

| Santo Antão | 27.0 | 28.6 | 21.3 | 14.3 |

| São Vicente | 2.3 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.2 |

| São Nicolau | 5.9 | 4.2 | 2.5 | 1.5 |

| Sal | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.05 |

| Boa Vista | 2.5 | 1.6 | 0.7 | 0.3 |

| Maio | 4.7 | 2.1 | 0.9 | 0.5 |

| Santiago | 56.6 | 42.4 | 26.0 | 16.5 |

| Fogo | 79 | 42 | 12.0 | 9.3 |

| Brava | 2.3 | 1.9 | 1.6 | 1 |

| Crops | Climate Demand | Precipitation (mm) | ETm (mm) | NIR (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carrot | Severe | 17.1 | 365 | 383 |

| Extreme | 1.9 | 375 | 420 | |

| Onion | Severe | 7.1 | 829 | 824 |

| Extreme | 4.3 | 706 | 883 | |

| Tomato | Severe | 7.1 | 584 | 564 |

| Extreme | 1.9 | 544 | 630 | |

| Cassava | Severe | 340.0 | 1048 | 840 |

| Extreme | 111.0 | 1057 | 907 | |

| Sweet potato | Severe | 156.1 | 459 | 380 |

| Extreme | 55.6 | 523 | 442 | |

| Corn | Severe | 0.0 | 754 | 728 |

| Extreme | 0.0 | 757 | 731 | |

| Banana | Severe | 524.7 | 1525 | 1366 |

| Extreme | 348.0 | 1440 | 1500 | |

| Peppers | Severe | 7.1 | 521 | 509 |

| Extreme | 1.9 | 487 | 560 | |

| Sugarcane | Severe | 342.5 | 1512 | 1421 |

| Extreme | 304.2 | 1626 | 1638 |

| Crops | Climate Scenarios | NIR (mm) |

|---|---|---|

| Banana | Dry year | 950 |

| Scenario2 | 1045 | |

| Rainy year | 1061 | |

| Onion | Dry year | 678 |

| scenario2 | 660 | |

| Rainy year | 678 | |

| Cabbage | Dry year | 391 |

| Scenario2 | 410 | |

| Rainy year | 380 | |

| Potato | Dry year | 518 |

| Scenario2 | 528 | |

| Rainy year | 488 | |

| Carrot | Dry year | 440 |

| Scenario2 | 406 | |

| Rainy year | 335 | |

| Tomato | Dry year | 517 |

| Scenario2 | 420 | |

| Rainy year | 312 | |

| Lettuce | Dry year | 225 |

| Scenario2 | 207 | |

| Rainy year | 208 | |

| Sweet potato | Dry year | 655 |

| Scenario2 | 605 | |

| Rainy year | 595 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).