1. Introduction

Karst spring discharge time series are known to exhibit highly irregular, heterogeneous, and multifractal dynamics [

5,

20]. These complex patterns reflect the underlying geologic heterogeneity, including the interaction between the porous matrix, fracture networks, and conduit systems [

7]. Traditional linear hydrological models, which often rely on simplified assumptions of stationarity and Gaussian-like fluctuations, fail to capture the intricacies inherent in karst hydrology, such as long-range dependence, sudden jumps in flow rates, and the influence of extreme events [

17].

The recession curves of karst spring hydrographs, frequently decomposed into distinct flow components (e.g., conduit-driven quick-flow and matrix-driven baseflow) serve as important indicators of aquifer properties, infiltration processes, and hydraulic connectivity [

5]. Although conceptual models such as those proposed by Mangin [

16] and Fiorillo [

5] provide useful insights by distinguishing various storage and drainage compartments, they often lack the ability to represent the non-linear and fractal or multifractal nature of observed discharge records [

16,

20]. Empirical studies have shown that karstic systems display scale-invariant behavior: the complexity of flow paths and conduit geometries induces fractal patterns in spring discharge time series [

23]. The fractal dimension

D characterizes the degree of roughness and complexity on multiple scales [

1,

21], and thus serves as a crucial quantitative measure to understand karst processes [

4,

10].

Motivated by these findings, it is imperative to develop stochastic modeling frameworks capable of reproducing both the fractal scaling and the jump-like features observed in karst spring discharges. In this study, we employ a fractional Ornstein–Uhlenbeck process (fOUp) enriched with jump components to model and simulate karst spring discharge dynamics. The fOUp is a continuous-time Gaussian process with long-range dependence, characterized by a Hurst exponent

H (with

), allowing it to capture persistent (

) and slowly decaying autocorrelations or anti-persistent (

) rough fluctuations inherent in karst systems [

3].

The usual, mean-reverting Ornstein–Uhlenbeck process, (OUp)

is defined by the stochastic differential equation (SDE):

where

is the mean-reversion parameter,

is the long-term mean,

is the volatility, and

is a classic Brownian motion. Extending the OUp to a fractional context involves replacing

with a fractional Brownian motion

of Hurst index

H. This introduces long-memory characteristics into the dynamics when

and rough fluctuation when

.

The ultimate source for renewing the karstic hydrogeological system is infiltration from precipitation or from melting snow. To address sudden discharge spikes originating from infiltration, we incorporate a jump component into the driving force of the fractional Ornstein–Uhlenbeck (fOU) equation, resulting in a hybrid model that can be schematically written as:

where

represents the jump component. In general modeling practice, often the jump component,

, follows a compound Poisson process. However, it has the shortcoming that the jump times and jump sizes are independent, and the process has the Markov property, enforcing exponential interarrival times (i.e., times between jumps, also called as sojourn times in renewal theory). This property is counterintuitive in our application, since a long delay between jumps – induced mainly by long delay in precipitation events – leaves the aquifer drained. Hence, the water from the next precipitation event - or a quick snowmelt for its turn - is kept back in the aquifer, filling up the porous matrix and the fracture networks, allowing for only lesser peaks in spring water discharge. Inspired by renewal theory and supported by statistical evidence (see

Section 6), we suggest using a semi-Markov jump process for

with Weibull-distributed interarrival times and also Weibull-distributed peaks [

24]. Contrary to Markov models, semi-Markov models allow interdependence of the process’ state and the interarrival time, and essentially place no restriction on the interarrival time distribution, see, e.g. [

24]. The proper correlation of the interarrival times and the jump sizes is secured by the probability integral transform and its inverse, along with the Gaussian copula. To the best of our knowledge, this model specification is novel in the literature. The jump component describes the abrupt short term, whereas the fractional component fine tunes the long-term behavior.

We apply this fractional jump Ornstein–Uhlenbeck framework to daily discharge data from karst springs in Northeast Hungary. The associated analysis illustrates the methodology’s capacity to replicate both the statistical and scaling features of the observed time series. By comparing simulated and observed discharge data, we demonstrate that this modeling strategy can reproduce essential empirical characteristics, such as fractal scaling, non-Gaussian tails, and sudden discharge extremes. Thus, the jump-fOUp approach provides new insights into the structure and complexity of karst aquifers and represents a promising avenue for understanding and predicting the non-linear, non-stationary, and fractal-like behavior of karstic spring discharges.

1.1. Outline of the Paper

The remainder of this article is organized as follows.

Section 2 introduces the modelling framework—a fractional Ornstein–Uhlenbeck process augmented by a renewal–reward jump term—together with its mathematical properties and a short proof of well-posedness, which can be found in Appendix A.

Section 3 reviews existing estimation techniques for the pure fOU process and adapts them into a two-tier procedure that later underpins our jump-fOUp inference.

Section 4 describes the geological setting, the 19-year daily discharge dataset from four Hungarian karst springs, and the exploratory analyses that motivate our model choices.

Section 5 presents the complete estimation–simulation workflow: detection of surges, copula-based generation of correlated jump pairs, fGn simulation for the fractional kernel, and the iterative scheme that couples both components.

Section 6 compares observed and simulated hydrographs, fractal dimensions, and cumulative discharges, demonstrating that the jump-fOUp reproduces key statistical and visual features markedly better than short-memory alternatives.

Section 7 discusses hydrological implications, the necessity of long-range dependence, and possible extensions such as time-varying parameters or precipitation-driven jump intensities. Finally,

Section 8 concludes with the main findings and outlines directions for future research.

2. Fractional Ornstein–Uhlenbeck Process with Renewal Jumps

2.1. The Pure fOUp

The (mean reverting) fractional Ornstein–Uhlenbeck process (fOUp) extends the usual Ornstein–Uhlenbeck model by incorporating the fractional Brownian motion (fBm) as its driving noise term. To distinguish it from its jump-enriched counterpart, we refer to it as pure fOUp. The fractional Brownian motion generalizes the classic Brownian motion (

) to incorporate long-range dependence or rough paths. If

, the increments are positively correlated, leading to persistent behavior, i.e., long memory. If

, the increments are negatively correlated, resulting in rough paths and antipersistent behavior. Let

be a continuous-time stochastic process satisfying the stochastic differential equation (SDE)

where

is the mean-reversion rate,

is the long-term mean toward which

reverts,

is the volatility parameter,

is a fractional Brownian motion with Hurst parameter

. The solution of the fOU equation exists and is unique up to initial condition

. It can be given by [

3]:

For

, the fOUp reduces to the usual OUp driven by a classic Brownian motion. The long-memory or rough path behavior is inherited by the fOUp from fBm according to the Hurst parameter. Unlike Bm and fBm the fOUp has a stationary regime. In contrast to the usual OUp, the fOUp is non-Markovian for

. For more details on the fOUp see, e.g., [

3].

2.2. Adding Jumps to the fOUp

We extend the fOUp dynamics by including jumps in the driving force to capture the long-memory or rough behavior of hydrological processes alongside sporadic, strictly positive surges that can be extreme in magnitude. The fOUp component encodes persistent correlations or rough fluctuations observed in hydrology. The jump components are responsible for the shocks that arrive from extreme water infiltration. In the simplest analogue, the jump diffusion setting, one might add a compound Poisson process whose interarrival times are exponentially distributed and whose jump sizes can in principle have arbitrary distributions. However, in hydrological systems where only positive, heavy-tailed surges are relevant and where jump sizes and interarrival times can exhibit dependence, the assumption of a compound Poisson structure becomes too restrictive. Our approach uses an analogy to renewal theory and incorporates an additive renewal-reward term into the fOU equation.

We enrich fOUp with jumps by first specifying a renewal-reward process

. The process

is specified by a sequence of increasing jump times

with

. The interarrival times

are positive random variables, and the jump sizes

are positive random variables. We set

. With these

if

. Both interarrival times

and jump sizes

have a Weibull distribution in our application, and variables

and

are correlated. In this way,

is a point process, with a nondecreasing, right-continuous, step-function sample path structure, for which stochastic integrals can be defined in terms of standard Lebesgue-Stieltjes integration theory. As a result, its differential

can also be viewed as a stochastic measure that puts jump size weights

on jump time points

. Now we define our jump-fOUp process

as:

Theorem 1.

Let be defined by equation (16)

. Then satisfies the stochastic differential equation,

where, is the mean reversion rate, θ is the equilibrium level, is the volatility, is a fractional Brownian motion (same as used in appendix - standardized notation to ), and is the renewal-reward process defined above.

The jump term

accumulates at random times governed by Weibull-distributed interarrivals and delivers jump magnitudes that are also Weibull-distributed. This construction ensures that each surge contributes a strictly positive, heavy-tailed (as the Weibull shape is invariably less than one in these applications, see

Section 6) increment to

, and that the negative correlation of interarrival times and jump sizes is preserved. The semi-Markov property emerges because the distribution of waiting times until the next jump depends on previously realized jump sizes (and vice versa), thereby departing from the memoryless exponential interarrivals of a compound Poisson process.

The flexibility of the model, resulting from the semi-Markov construction, allows the simultaneous reproduction of heavy-tailed surges and their further spreading effect and long-memory fluctuations. This resolves a common challenge in hydrological modeling, where only positive, subexponential jumps with significant extremal impact can occur. By merging Weibull-based jump processes with fractional diffusion, one captures rare yet sizeable excursions on top of a persistently correlated or anti-persistent baseline.

3. Parameter Estimation Methods

Much effort has been devoted to the parameter estimation problem for fOU processes. Assuming that a continuous record of observations is available in the non-mean-reverting case (

), Kleptsina and Le Breton [

14] obtained first the formula for the drift parameter’s maximum likelihood (ML) estimation and proved almost sure convergence. Bercu, Courtin and Savy [

2] proved a central limit theorem for the MLE in the case of

. They claimed without proof that the above convergence is also valid for

. Finally, Tanaka et al. [

26] completed the case by studying the ML estimates when

and

.

Turning to mean reversion with

and keeping the assumption of continuous observation, Lohvinenko and Ralchenko [

19] obtained the ML estimates of

and

when

and

.

Estimating the parameter vector

of the fOUp in the more realistic case of discrete, time-equidistant observations

poses significant challenges due to the fractional nature of the driving noise. In the non-mean-reverting case specialized statistical methods were developed in [

12,

13], using the relationship between the Skorokhod (or divergence) and Stratonovich integrals. These works also provide limit theorems for the estimation as both the time horizon and the mesh size grow to infinity simultaneously, and the horizon increases faster than the mesh size. However, this condition is difficult to verify in a real application with finite sample size.

3.1. A Two–Tier Estimation Framework for the fOU Parameters

This section consolidates, in a single presentation, the continuous–record methodology of [

12,

13] and its exact, discrete–sample analogue due to [

29]. Both procedures target the parameter vector

of a fOUp

Tier I — continuous record ([13]).

Assuming full observation of the path

, the mean–reversion speed

can be consistently recovered by either

least squares

or the

energy–type statistic;

where

denotes Euler’s gamma function. Both estimators are strongly consistent and asymptotically normal as

.

Tier II — exact discrete record ([29]).

Let

be an equally spaced sample of size

N with the grid step

. Define second-order differences and their quadratic variations.

Closed-form, strongly consistent estimators are then obtained as

4. Application to Karstic Spring Discharge Modeling

4.1. Geological and Hydrological Settings

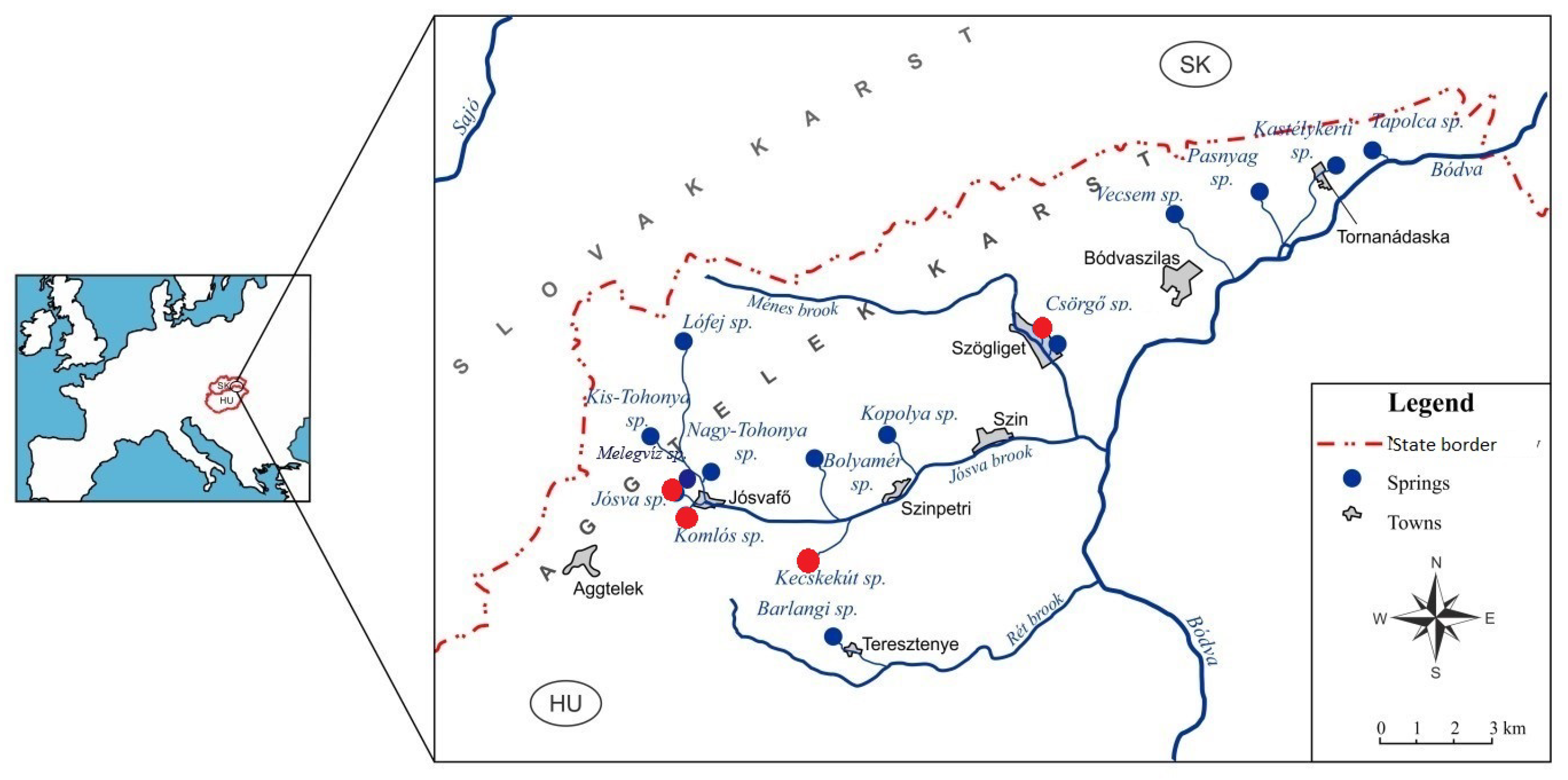

The Aggtelek Karst, part of the Gömör-Torna Karst region on the Hungarian-Slovakian border, is predominantly composed of Triassic carbonates, mainly Wetterstein limestone and dolomites [

27]. The Hungarian section comprises approximately 200 km

2 of east–west-oriented karst plateaus at elevations of 400–600 m a.s.l., dissected by valleys as low as 150–260 m. Karstification began in the Miocene under subtropical conditions, with significant Pliocene uplift that forms the present-day north-south topographic gradient [

9,

11]. The mean annual precipitation is about 600 mm, most of which infiltrates the plateau and resurfaces at karst springs. The area has a humid continental climate with a mean annual temperature of 9.1 °C, about 120–130 frost days, and 40 snow-covered days annually [

27].

These geological and climatic data originate from Telbisz et al. [

27]. The dataset, and descriptions therein are based on decades of multidisciplinary fieldwork and geological mapping [

8,

18], and are considered reliable and high-quality within the regional geoscientific community.

4.2. Data Description

The measurement of the daily spring discharge of the most significant karstic springs in the Aggtelek Karst was carried out by the Hungarian Water Resources Research Plc. (VITUKI) from the early 1960s to the 1990s [

22]. We selected four springs (Csörgő, Kecskekút, Komlós, Lófej) with non-missing daily observations for 6200 days in the period from 1 March 1974 to 18 February 1993. The basic descriptive statistics of these decades of uninterrupted hydrological data series are shown in

Table 1.

The springs are located within a relatively small area, close to each other (

Figure 1). However, significant scale differences can be observed in their daily discharges: the multiannual averages vary between 287 and 14508.5

, see

Table 1. Cave systems of varying lengths, are known to be connected with the springs [

15,

25]. In Jósva spring water comes to the surface from the 25 km long Baradla-Domica cave system. Komlós spring (Kom) is connected to Béke cave (approx. 7.2 km long). Szabadság cave (approx. 3.2 km) belongs to the aquifer of Kecskekút spring (Kec). Caves of much shorter confirmed lengths – typically a few hundred meters, as cave researchers put it to current knowledge - lie behind the Csörgő spring (Cso) [

15]. The cave systems direct quick flows to the mouth of the springs, taking essential role in shaping the surges in the hydrographs.

5. Methodology: Parameter Estimation and Simulation

The objective is to model the daily discharge time series

of several karst springs. The model assumes that the discharge dynamics results from the superposition of a continuous, persistent background process and discrete, sudden jump events, often triggered by precipitation. A jump fOUp as described in

Section 2 is employed. The analysis proceeds spring by spring; the following sections outline the methodology for a single representative time series

,

. The modeling process involves two main phases: estimating model parameters from the observed data and simulating the process using these parameters.

5.1. Phase 1: Parameter Estimation from Observed Data

5.1.1. Data Preparation and Initial Analysis

Let denote the observed discharge at day t. The differenced series, for , is calculated to highlight rapid changes or jumps (Algorithm A1, line 1).

5.1.2. Jump Component Identification and Characterization

Jump Detection: Jumps are identified where

exceeds a high quantile threshold,

, where

p is a high probability, chosen as 0.975 (Algorithm A1, line 2). Let

be the time index of the

j-th detected jump,

(Algorithm A1, line 3). (For heuristic explanation see

Section 6.1).

Jump Size Analysis: The jump sizes are (Algorithm A1, line 4). Their distribution is analyzed by fitting candidate distributions (Weibull and Gamma) to using Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) (Algorithm A1, lines 6). Goodness-of-fit is assessed using Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) tests. Let denote the estimated jump size parameters.

Jump Timing Analysis: The inter-arrival times (with ) are calculated (Algorithm A1, line 5). Their distribution is analyzed similarly, fitting a Weibull distribution to a slightly perturbed data, via MLE (Algorithm A1, line 8). Perturbation is necessary because being a continuous distribution, integers and ties do not fit the Weibull. Perturbation is created by adding a Uniform[0.01,0.5] variable to the jump sizes. The effect of the perturbation is then analyzed using 100 perturbations. Let denote the estimated jump time parameters.

Jump Dependence Structure: The dependence between jump sizes and preceding inter-arrival times is quantified by the sample correlation coefficient (Algorithm A1, line 9). Typically, is significantly less than 0.

5.1.3. Background Process Characterization

Hurst Parameter Estimation: The long-range dependence is quantified by the Hurst parameter

. For the background process, assuming the fOUp structure, it is estimated from (

9) (Algorithm A1, line 10). However, for the complete

process with jumps – when (

9) is not applicable – it is estimated using the madogram method via the fractal dimension:

. It also serves to remain compatible with the findings of [

4].

-

Fractional Ornstein-Uhlenbeck (fOU) Parameter Estimation: The background process is modeled as an fOUp, and its parameters are estimated from a truncated series

(Algorithm A1, lines 11-12, see also

Section 6).

- −

-

Volatility (): Estimated from the second differences of

using

:

(Algorithm A1, line 13).

- −

-

Mean Reversion Rate (): Estimated from the variance of

and

:

(Algorithm A1, line 14).

5.2. Phase 2: Simulation Setup

Jump Simulation via Gaussian Copula: To preserve the correlation between jump times and jump sizes, a Gaussian copula is used. To create a large sample from the Gaussian copula, pairs of correlated standard normal variables with correlation are generated and transformed to uniform via the normal CDF (Algorithm A1, line 15-16). Simulated inter-arrival times and raw jump sizes are generated using the inverse CDFs of the fitted Weibull distributions (Algorithm A1, lines 20-29). Since this transformation does not preserve the correlation, is chosen slightly larger than , the target one. Subsampling is then performed on these L pairs until we obtain a final sequence of pairs , so many that jump times cover the [0,T] time interval, and their correlation reaches the target (Algorithm A1, lines 19-25). An innovation array of length N is built by filling it up with the final jump increments at the simulated jump times , and with zeros elswhere. (Algorithm A1, lines 31-34).

Fractional Gaussian Noise (fGn) Simulation: A sequence of fGn increments with Hurst parameter is generated by differencing a simulated fBm (e.g., by using the somebm package of R) and scaled using the estimated volatility (Algorithm A1, lines 36-37).

5.3. Phase 3: Combined Process Simulation Loop

Writing

as

and integrating in (16) first from 0 to

and then from

to

t we obtain

The last integral is

if

for a jump time

, or zero otherwise. Since

is small in our case, we obtain an approximation

Using the approximation the final discharge series

is generated iteratively for

:

where

is the total innovation (

fGn + jump), and

is the initial value (Algorithm A1, lines 38-42):

This procedure generates a synthetic time series to replicate the statistical properties of the observed discharge.

6. Application: Jump Distribution Fitting and fOUp Parameter Estimation for Karstic Spring Discharges

6.1. Separating the Jumps

The surges in spring discharges are not merely isolated spikes; rather, they exert a dampening effect on the recession curve. Consequently, it is not sufficient to model these as simple jumps in the process itself — they must be incorporated into the driving force of the dynamics, specifically in the differential component of the stochastic differential equation (SDE). Therefore, to locate the jump positions and sizes, the differenced series has to be considered. The quantiles and maxima of the differenced spring discharge series are presented in

Table 2.

The comparison of quantiles, maxima, and their relative proportions in

Table 2 reveals the heavy-tailed nature of the underlying distribution. This observation rules out the adequacy of a pure fOUp for modeling. Replacing fractional Brownian motion (fBm) with a Lévy flight in the SDE could address heavy-tail behavior, but it would fail to capture the correlation between extreme values and their timing. This limitation motivated the development of our proposed approach.

To corroborate the jump threshold used,

Table 2 lists the empirical

,

and

quantiles. Across all springs, the largest observed surge is roughly 20 to 450 times the

-quantile and 10 to 200 times the

-quantile, while the

-quantile is only 2 to 3 times the

-quantile. So, choosing the

-quantile level as the cut-off effectively separates the extreme outliers, interpreted as hydrogeological ’jumps’, from the long-memory background. 155 values are observed above the

-quantile level, and it is still suitable to fit a distribution to them with sufficient accuracy. Hence, we choose this threshold to determine the jumps.

6.2. Jump Distributions and Waiting–Time Dependence

We analyze karst spring discharges through two complementary layers. First, we model the jump component by semi-Markov dynamics, whose inter-arrival times and magnitudes follow Weibull laws. Second, after excising these jumps, the residual series is represented by a fractional Ornstein–Uhlenbeck baseline whose parameters are inferred from second–order differences as set out in

Section 3. All statistical decisions (choice of distribution, selection of the jump threshold, and verification of long–memory parameters) are supported by formal goodness-of-fit tests and by the scaling diagnostics summarized below.

6.3. fOU Background: Continuous Versus Truncated Records

After removing every surge that exceeds the

empirical quantile, a fractional–Ornstein–Uhlenbeck (fOU) model is fitted to the resulting

jump-filtered series.

Table 3 lists the estimated volatility

, damping coefficient

, memory scale

and Hurst exponent

.

Across all springs is small, so the background discharge reverts slowly to its mean; the associated memory indicates pronounced persistence, while the conditional variance is far lower than in the raw data. The Hurst exponents fall between and , confirming long-range dependence in the smooth baseline component.

6.4. Scaling Check via Fractal Dimension

To verify that the combined model—semi-Markov jumps plus fOU baseline—captures the multiscale roughness of the data, the fractal dimension

D of each observed record is compared with the mean

D from 100 simulated paths (

Table 4). The close match confirms that the model reproduces the measured texture across scales.

The

values in

Table 4 describe the full jump + fOU process, so they are systematically lower than the background

in

Table 3: high-frequency jump spikes shorten the effective memory, whereas the jump-filtered baseline retains the longer-range dependence quantified in the first subsection.

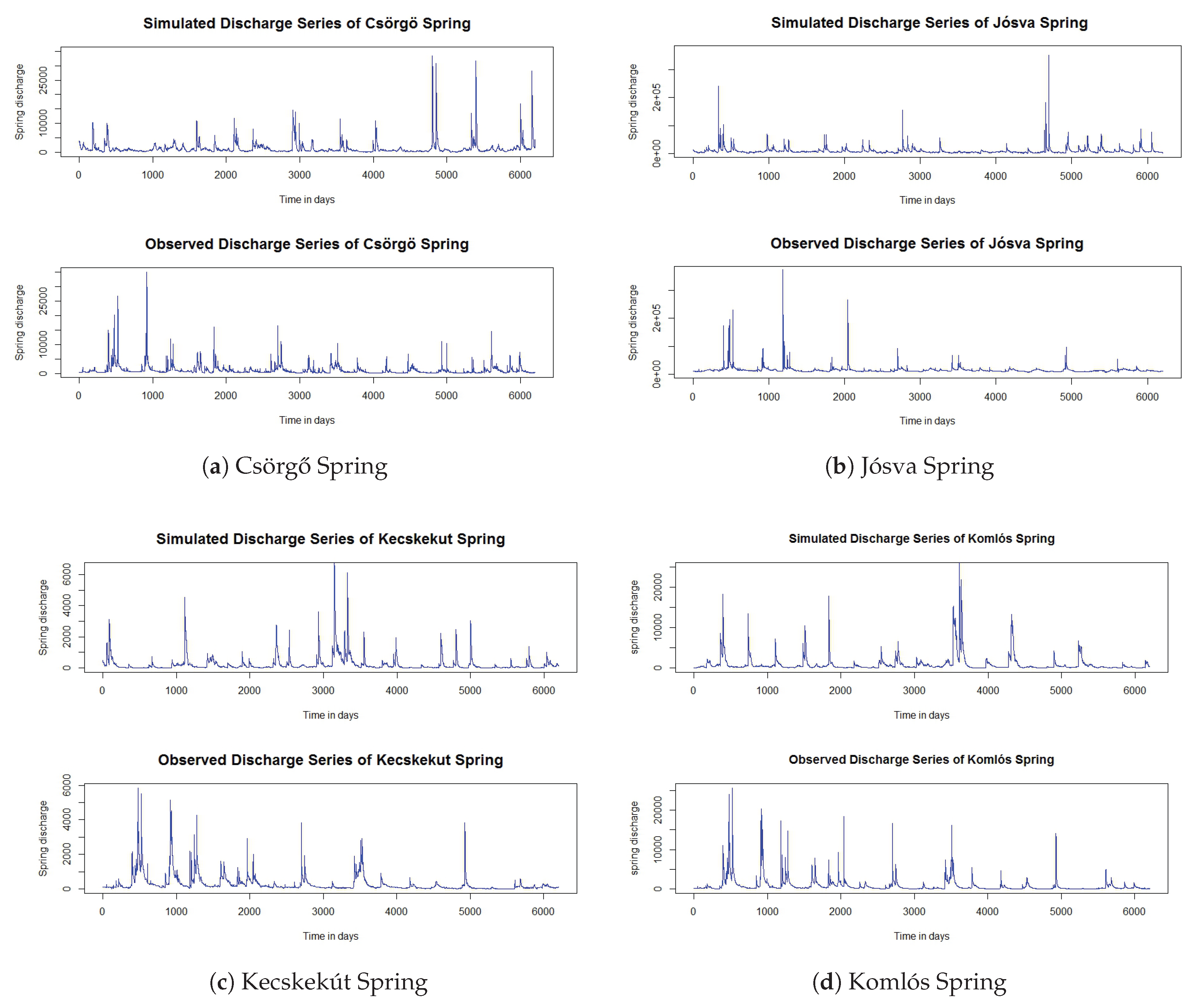

Figure 2 displays the simulated and observed hydrographs of the four springs and demonstrates that simulations, based on the fitted model, exhibit strong visual agreement with the observed time series. This directly addresses a common criticism from hydrological and hydrogeological experts, who often contend that mathematical models—despite achieving good statistical fits in certain aspects—fail to produce realistic-looking hydrographs.

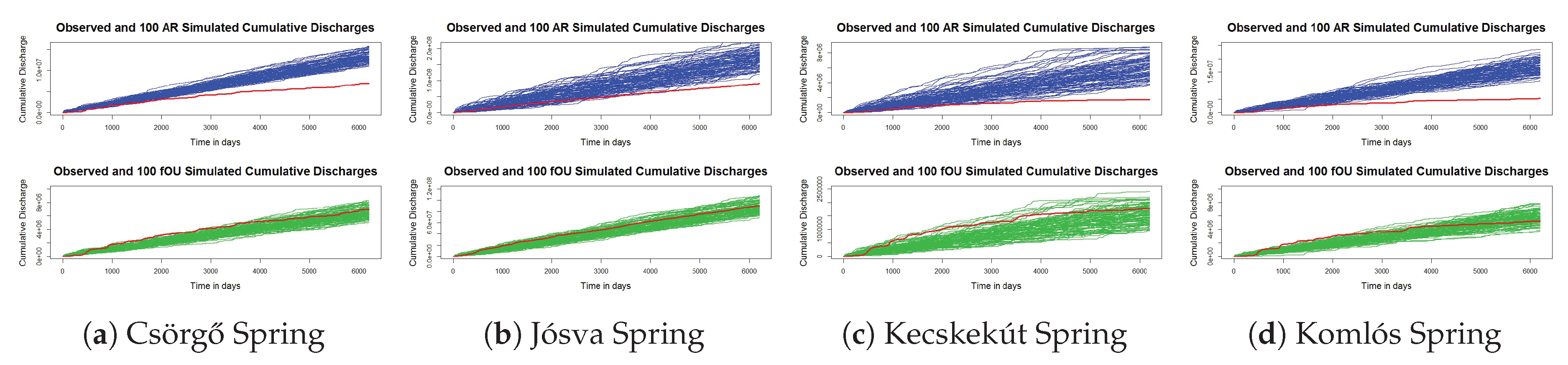

From a water resources management perspective, cumulative discharge is of paramount importance, as it directly reflects the volume of water available for various uses over a given period. Therefore, its accurate estimation is a key objective in hydrological modeling.

Figure 3 demonstrates the performance of our model in this regard. To highlight the critical role of long-range dependence, we replace the background flow component with an autoregressive (AR) process, while retaining the same jump sequence used in the jump-fOUp simulation. The outcome is striking: the 100 cumulative discharge trajectories generated by the AR model (blue lines) significantly overshoot the observed discharge (red line), in some cases more than doubling it by the end of the period. In contrast, simulations based on the fOUp model closely track the empirical data, underscoring the model’s accuracy. Moreover, the variability among the jump-AR simulations is substantially higher than that of the jump-fOUp simulations, reflecting the latter’s smoother trajectories. These results illustrate that the jump-fOUp model yields more reliable cumulative discharge estimates, enhancing its utility for water resource planning and management.

7. Discussion

The jump-fOUp model integrates within a single stochastic framework the two primary controls of karst discharge: the long-range dependent background flow—comprising multiple hydrogeological components—captured via the fractional Ornstein-Uhlenbeck process, and the heavy-tailed recharge surges, modeled through a renewal-reward jump process with correlated, heavy-tailed inter-arrival times and magnitudes.

Figure 2 illustrates that simulated and observed hydrographs exhibit strong visual agreement, while

Table 4 confirms that the model replicates the observed fractal dimension within the limits of sampling error. This demonstrates that the jump-fOUp model provides a generative mechanism capable of faithfully

reproducing these key features.

In comparison to short-memory AR baselines [

16], the jump-fOUp model offers significantly improved tracking of cumulative discharge volumes (

Figure 3). This highlights that omitting long-range dependence—governed by the Hurst parameter

H— can lead to potentially flawed assessments of water resources. When the background flow, represented by the truncated process, is instead modeled with a short-memory AR(1) process, a single AR parameter must account for all temporal dependencies. This results in systematically higher AR parameter estimates compared to the memory parameter in the fOUp model. Moreover, because this parameter acts not only on the driving noise but also on the jumps, it dampens the jump effects more slowly than in the fOUp case, thereby forecasting elevated discharges in the following days. The cumulative result—total discharged water volume—becomes unrealistically high, yielding an overly optimistic outlook for water resource management.

The improved accuracy in cumulative discharge estimation provided by our model arises from two key components:

- (i)

a fractional kernel that propagates hydrological memory across months to years, and

- (ii)

Weibull–Weibull jump pairs, whose negative correlation between size and waiting time reflects the natural depletion–recharge dynamics of the aquifer (

Table 5).

Unlike Poisson jump-diffusions [

28] or Lévy flights, the semi-Markov specification preserves both the heavy tail and the empirically observed dependence between surge size and lead time, a combination that classical multifractal surrogates describe but cannot generate mechanistically.

Parameter identification remains demanding, and further research into (e.g., iterative, likelihood-based, or Bayesian approaches for discretely observed jump-fOU processes would be beneficial. However, the current method yields parameters that produce simulations consistent with key empirical observations, including the crucial fractal dimension. Finally, extensions like time-varying or precipitation-driven jump intensities—offer an avenue to embed climate signals directly into the discharge generator.

8. Conclusions

In the presented analysis a jump-fOUp with Weibull–Weibull semi-Markov surges reproduces the amplitude distribution, fractal dimension and cumulative discharge of four Hungarian karst springs. Long-range dependence () is indispensable: replacing the fractional kernel with short-memory noise inflates the accumulated volume by up to 50 %. Surge size and waiting time are negatively correlated; modelling them jointly is crucial for realistic flood peaks.

The framework therefore bridges descriptive multifractal analysis and process-based simulation, and can be extended with time-varying parameters or rainfall covariates for predictive use.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.M. and J.K.; Methodology, L.M. D.B. and E.B.; Software, D.B.; Validation, D.B., E.B. and A.D.; Formal Analysis, D.B. and L.M.; Investigation, E.B. and A.D.; Resources, J.K.; Data Curation, E.B. and J.K.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, D.B. and L.M.; Writing—Review and Editing, L.M., J.K., D.B., E.B. and A.D.; Visualization, D.B. and L.M.; Supervision, L.M.; Project Administration, L.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. This study involved the analysis of publicly available historical hydrological data and did not involve human subjects or live animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The daily discharge data for the Aggtelek karst springs used in this study were originally collected by the Hungarian Water Resources Research Plc. (VITUKI) and are described in [

22]. The processed data used for the analysis are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the National Research, Development and Innovation Office for the support within the framework of the Thematic Excellence Program 2021 – National Research Sub programme: “Artificial intelligence, Large Networks, data security: mathematical foundation and applications" and the Artificial Intelligence National Laboratory Program (MILAB). We appreciate the support provided by neptune.ai. We are also incredibly thankful for the Ministry of Innovation and Technology of Hungary from the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund, that took part in financing this research under the Eötvös Loránd University TKP 2021- NKTA-62 funding scheme.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AIC |

Akaike Information Criterion |

| AR |

Autoregressive |

| ARMA |

Autoregressive Moving Average |

| Bm |

Brownian motion |

| CDF |

Cumulative Distribution Function |

| ET |

Energy-Type (statistic) |

| fBm |

Fractional Brownian motion |

| fGn |

Fractional Gaussian noise |

| FD |

Fractal Dimension |

| fOU |

Fractional Ornstein–Uhlenbeck |

| fOUp |

Fractional Ornstein–Uhlenbeck process |

| Jump-fOUp |

Jump Fractional Ornstein–Uhlenbeck process |

| K–S |

Kolmogorov–Smirnov |

| LF |

Linear Filter |

| LSE |

Least Squares Estimator |

| MLE |

Maximum Likelihood Estimation |

| OUp |

Ornstein–Uhlenbeck process |

| PDF |

Probability Density Function |

| SD |

Second Difference |

| SDE |

Stochastic Differential Equation |

| VITUKI |

Vízgazdálkodási Tudományos Kutató Intézet (Water Resources Research Institute) |

Appendix A. Proof of Theorem 1

Problem Setup

We are given a stochastic process

defined in (16) as:

Here

is a fractional Brownian motion (fBm) with Hurst parameter

,

is a càdlàg, non-decreasing

renewal-reward process (implying

J has only finitely many jumps on any compact time interval

), and

is the initial condition, independent of

and

J. The constants

,

,

are given.

If

,

has sample paths that are almost surely Hölder continuous of any order

. Since

can be chosen such that

, and the kernel

is Lipschitz continuous (hence, of bounded 1-variation) on

, the integral exists pathwise as a

Young integral [

30]. The condition for existence is

where

p is the variation exponent of the kernel and

q is the variation exponent of the integrator. Here

(bounded variation) and

has finite

q-variation for any

. So

requires

, which is always true. Thus, the Young integral exists.

If

, the paths of

are rougher (infinite

q-variation for

). Although the standard Young theory might not directly apply based solely on Hölder exponents, the integral is still well defined pathwise using extended frameworks like

fractional calculus integration developed by Zähle [

31]. This approach defines

when

f possesses a certain fractional smoothness related to the roughness of

g. Since our kernel

is

in

s, the necessary conditions are met for all

.

We denote this integral simply by

, understanding its pathwise nature (consistent with frameworks like Rough Paths [

6]).

The term is a Riemann-Stieltjes integral. Since is a renewal-reward process, its sample paths are càdlàg, non-decreasing, and piecewise constant (step functions). Consequently, has almost surely bounded variation on any compact interval . The kernel is continuous on . Therefore, the classical Riemann-Stieltjes integral exists pathwise for each realization . It can be explicitly written as a finite sum over the jump times of J:

where

is the jump size

at time

.

Our objective is to rigorously prove, using pathwise differentiation techniques, that

defined by (16) satisfies the stochastic differential equation (SDE):

The term

should be interpreted in the context of the pathwise integral theory, and

represents the increments of the jump process.

The arguments above establish that both stochastic integrals in the definition (16) of are well defined pathwise for almost every realization , for all . The integral relies on the Young/Zähle theory, while uses the classical Riemann-Stieltjes theory for integrators of finite variation.

Differentiating the Terms of X ˜(t)

We differentiate with respect to t by considering each term in (16). We employ appropriate Leibniz rules for pathwise Stieltjes integrals. Let , where , , are the deterministic, fractional, and jump parts respectively.

Deterministic Terms

The first two terms

are deterministic and smooth. Therefore,

Fractional Brownian Motion Term

Let

. We need to compute

. Since the integral is pathwise (Young/Zähle), we can apply a suitable Leibniz rule. For an integral

, where

k is sufficiently smooth in

t and the integral exists pathwise, the rule is formally:

This rule is rigorously justified in the context of Young integration [

30] and its extensions [

6,

31] when

.

We apply the rule to

. Here,

. Thus

and

. We have:

Multiplying by

we arrive at:

Jump Term

Let

. Since

is a step function with bounded variation and

is smooth, we can apply the Leibniz rule (

A2) for Stieltjes integrals with

replacing

. Using

and

again:

Here,

represents the Stieltjes differential of

J. If

t is not a jump time,

. If

is a jump time,

corresponds to a measure with mass

at

. This formula correctly captures both the continuous evolution between jumps (where only the

term is active) and the discrete jumps (where

is active and equals

).

Combining the Differentials

Now we sum the differentials of all parts of

:

Substituting from (

A1), (

A3), and (

A4):

Simplify the coefficient of the

term, by using (16) rearranged as:

Substitute this into the

coefficient:

Thus, the combined differential is:

This is precisely the target SDE (

6).

In summary, we have rigorously shown that the process

defined by (16) satisfies the stochastic differential equation (

6). The derivation relies on the pathwise interpretation of the stochastic integrals and standard rules of calculus applied to the deterministic part, combined with the Leibniz rule for pathwise Stieltjes integrals for the fractional and jump components. The calculation confirms that

is the unique strong solution to the SDE (

6). □

Appendix B. Algorithm Pseudocode

|

Algorithm A1 Simulation of Karst Spring Discharge using Jump-Diffusion fOU Model |

|

References

- Addison, P. Fractals and Chaos: An Illustrated Course; Institute of Physics Publishing: Bristol, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bercu, B.; Courtin, S.; Savy, N. MLE for the drift parameter of the fractional Ornstein-Uhlenbeck process. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1604.04030. [Google Scholar]

- Biagini, F.; Hu, Y.; Øksendal, B.; Zhang, T. Stochastic Calculus for Fractional Brownian Motion and Applications; Springer Science and Business Media: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Borbás, E.; Márkus, L.; Darougi, A.; Kovács, J. Characterization of karstic aquifer complexity using fractal dimensions. GEM - International Journal on Geomathematics 2021, 12:4, 1–27. [CrossRef]

- Fiorillo, F. The Recession of Spring Hydrographs, Focused on Karst Aquifers. Water Resour. Manag. 2014, 28, 1781–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friz, P.K.; Hairer, M. A Course on Rough Paths: With an Introduction to Regularity Structures; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Goldscheider, N.; Mádl-Szőnyi, J.; Erőss, A.; Schill, E. Thermal water resources in carbonate rock aquifers. Hydrogeol. J. 2010, 18, 1303–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grill, J.; Kovács, S.; Less, Gy.; Réti, Zs.; Róth, L.; Szentpétery, I. Az Aggtelek-Rudabányai-hegység főtektonikai felépítése és fejlődéstörténete. (Main tectonic structure and evolution of the Aggtelek-Rudabánya Mountains). Földt. Kut. 1984, 27, 49–56. (In Hungarian) [Google Scholar]

- Haas, J. Geology of Hungary; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hergarten, S.; Birk, S. A fractal approach to the recession of spring hydrographs. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2007, 34, L11401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hevesi, A. Magyarország karsztvidékeinek kialakulása és formakincse I-II. (The origin and landforms of the karst terrains of Hungary). Földr. Közl. 1991, 115, 25–35, 99–120. (In Hungarian) [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; Nualart, D. Parameter estimation for fractional Ornstein-Uhlenbeck processes. Stat. Probab. Lett. 2010, 80, 1030–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Nualart, D.; Zhou, H. Parameter estimation for fractional Ornstein-Uhlenbeck processes of general Hurst parameter. Stat. Inference Stoch. Process. 2017, 22, 111–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleptsina, M.L.; Le Breton, A. Statistical analysis of the fractional Ornstein-Uhlenbeck type process. Stat. Inference Stoch. Process. 2002, 5, 229–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordos, L. Magyarország barlangjai. (Caves of Hungary); Gondolat Kiadó: Budapest, Hungary, 1984. (In Hungarian) [Google Scholar]

- Labat, D.; Mangin, A.; Ababou, R. Rainfall-runoff relations for karstic springs: multifractal analyses. J. Hydrol. 2002, 256, 176–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labat, D.; Hoang, C.T.; Masbou, J.; Mangin, A.; Tchiguirinskaia, I.; Lovejoy, S.; Schertzer, D. Multifractal behaviour of long-term karstic discharge fluctuations. Hydrol. Process. 2012, 26, 1072–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Less, G. Polyphase evolution of the structure of the Aggtelek-Rudabanya Mountains (NE Hungary), the southern element of the inner Western Carpathians a review. Slovak Geol. Mag. 2000, 6, 260–268. [Google Scholar]

- Lohvinenko, T.; Ralchenko, K. Parameter estimation for the fractional Ornstein–Uhlenbeck process with periodic mean. Mod. Stoch. Theory Appl. 2019, 6, 337–355. [Google Scholar]

- Majone, B.; Bellin, A.; Borsato, A. Runoff generation in karst catchments: multifractal analysis. J. Hydrol. 2004, 294, 176–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandelbrot, B.B. Fractals: Form, Chance, and Dimension, Revised ed.; W. H. Freeman and Co.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1977.

- Maucha, L. Az Aggtelek-hegység karszthidrológiai kutatásai eredményei és zavartalan hidrológiai adatsorai 1958-1993. (Results of the karst hydrological research in Aggtelek Mts and its unbiased hydrological data 1958-1993); Water Resources Research Institute VITUKI Rt., Hydrological Institute: Budapest, Hungary, 1998. (In Hungarian).

- Pardo-Igúzquiza, E.; Dowd, P.A.; Durán, J.J.; Robledo-Ardila, P. A review of fractals in karst. Int. J. Speleol. 2019, 48, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, S.M. Stochastic Processes, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Székely, K. (Ed.) Magyarország fokozottan védett barlangjai. (Strictly Protected Caves of Hungary); Mezőgazda Kiadó: Budapest, Hungary, 2003. (In Hungarian) [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, K.; Xiao, W.; Yu, J. Maximum likelihood estimation for the fractional Ornstein-Uhlenbeck process with discrete observations. Econom. Theory 2020, 36, 929–962. [Google Scholar]

- Telbisz, T.; Gruber, P.; Mari, L.; Kőszeghi, M.; Bottlik, Zs.; Standovár, T. Geological Heritage, Geotourism and Local Development in Aggtelek National Park (NE Hungary). Geoheritage 2020, 12, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veneziano, D.; Essiam, A.K. Flow through porous media with multifractal hydraulic conductivity. Water Resour. Res. 2003, 39, 1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.; Wang, X.; Yu, J. Estimation and inference in fractional Ornstein–Uhlenbeck model with discrete-sampled data. Unpublished manuscript, 2018. Available online: https://www.stern.nyu.edu/sites/default/files/assets/documents/TwostagefVm09.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Young, L.C. An inequality of the Hölder type, connected with Stieltjes integration. Acta Math. 1936, 67, 251–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zähle, M. Integration with respect to fractal functions and stochastic calculus I. Probab. Theory Relat. Fields 1998, 111, 333–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).