Submitted:

21 May 2025

Posted:

22 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

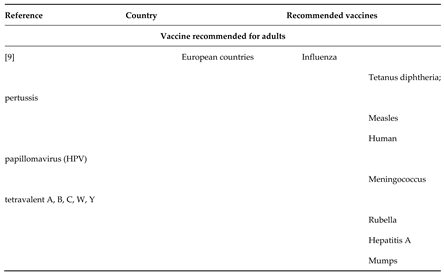

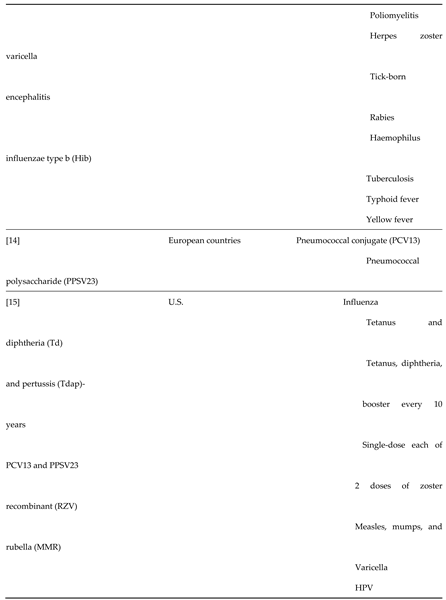

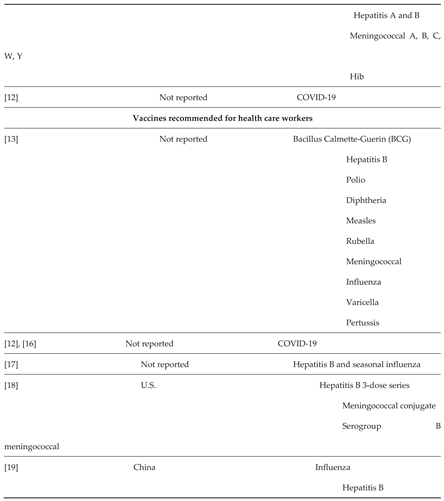

1.1. Recommended Vaccines

1.2. Vaccination Uptake Among Adults

1.3. Description of the Intervention

1.4. How the Intervention Might Work

1.5. Why It Is Important to Do This Review

1.6. Objectives

2. Methods

2.1. Criteria for Considering Studies for This Review

2.1.1. Types of Studies

2.1.2. Types of Participants

2.1.3. Types of Interventions

2.2. Recipient-Oriented Interventions.

- Interventions to inform or educate adults about vaccination.

- Advertising and promotional campaigns for adult vaccination.

- Recipient reminders [29].

- Recipient incentives.

- Communication strategies: presumptive communication approach; gain-framed versus loss-framed communication; use of science and anecdotes; motivational interviewing; health coaching; clinicians providing a strong recommendation to the adult; and other communication tactics to facilitate decision-making.

- Tailored interventions (e.g. the Medicare Annual Wellness Visit in the U.S., which aims to establish a five- to 10-year personalised prevention plan, including needed vaccinations).

2.3. Interventions Targeting Providers of Adult Vaccination Service

- Education or training of vaccinators.

- Audit and feedback for vaccinators or clinical practices.

- Provider reminders.

- Clinical decision support tools.

- Academic detailing.

- Supportive supervision of, or educational outreach visits to, vaccinators.

- Pay-for-performance.

- Provider incentives.

- Standing vaccination orders.

- Use of vaccination champions.

- Quality improvement processes.

2.4. Interventions Directed at the Broader Health System

- Reliable cold chain system.

- Vaccine stock management.

- Expanded services (e.g. extended hours for vaccination services).

- Increased vaccination budget.

- Integration of vaccinations with other services.

- Provision of vaccinations in non-traditional settings: inpatient units, emergency departments,

- workplaces, home visits, community, churches.

- Use of vaccination registries and other electronic health records.

- Public information programmes.

- Provision of transport for vaccination.

- Vaccine mandates (e.g. for employment, school, university matriculation).

- Provision of free vaccinations or reductions in out-of-pocket costs.

- Offer health insurance coverage of vaccinations.

2.5. Multi-Component Interventions

- 1.

- Those that included more than one type of tactic for increasing coverage.

2.6. Exclusion

2.7. Comparison

2.8. Types of Outcome Measures

2.8.1. Primary Outcomes

2.8.2. Secondary Outcomes

2.9. Search methods for Identification of Studies

2.9.1. Electronic Searches

- Medline Ovid

- Embase Ovid

- PubMed

- Web of Science

- Conference Proceedings Citation Index – Science

- Global Index Medicus.

2.9.2. Searching Other Resources

- WHO ICTRP (International Clinical Trials Registry Platform; www.who.int/ictrp).

- US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov).

2.10. Grey Literature

- OpenGrey (www.opengrey.eu).

- Grey Literature Report (New York Academy of Medicine; www.greylit.org).

2.11. Other Resources

2.12. Data Collection and Analysis

2.12.1. Selection of Studies

2.12.2. Data Extraction and Management

- Methods: study design, number of study centres and location, study setting, withdrawals, date of study, and follow-up.

- Participants: number, mean age, age range, sex, inclusion criteria, exclusion criteria, and other relevant characteristics.

- Interventions: intervention components, and comparisons.

- Outcomes: main and other outcomes specified and collected, and time points reported.

- Notes: funding for trial, notable conflicts of interest of trial authors, and ethical approval.

2.12.3. Assessment of Risk of Bias in Included Studies

- Random sequence generation.

- Allocation concealment.

- Blinding of participants and personnel.

- Blinding of outcome assessment.

- Incomplete outcome data.

- Selective outcome reporting.

- Baseline outcomes measurement.

- Baseline characteristics.

- Other bias

2.12.4. Measures of Treatment Effect

2.12.5. Unit of Analysis Issues

2.12.6. Dealing with Missing Data

2.12.7. Assessment of Heterogeneity

2.12.8. Assessment of Reporting Biases

2.12.9. Data Synthesis

2.12.10. Summary of Findings and GRADE

2.12.11. Subgroup Analysis and Investigation of Heterogeneity

2.12.12. Sensitivity Analysis

- Restricting the analysis to published studies.

- Restricting the analysis to studies with a low risk of bias.

- Imputing missing data.

2.12.13. Stakeholder Consultation and Involvement

2.12.14. Summary of Findings and Assessment of the Certainty of the Evidence

2.13. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Description of Studies

3.1.1. Results of the Search

3.1.2. Included Studies

3.2. Effects of Interventions

3.2.1. Recipient-Oriented Interventions

Overall Reminders Versus Control or Standard Care

Different Types of Reminders on Vaccination Uptake

Education Versus Control or Standard Care

Tracking and Outreach Versus Control or Standard Care

Promotional Campaigns vs Control or Standard Care

Financial Incentives

3.2.2. Provider-Oriented Interventions

Letter Reminders Versus Control or Standard Care

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Main Results

4.2. Overall Completeness and Applicability of Evidence

4.3. Quality of the Evidence

4.4. Potential Biases in the Review Process

4.5. Agreements and Disagreements with Other Studies or Reviews

5. Authors' Conclusions

5.1. Implications for Practice

5.2. Implications for Research

Acknowledgments

References

- S. Vanderslott, “How is the world doing in its fight against vaccine preventable diseases?,” ourworldindata.org/vaccine-preventable-diseases.

- M. J. Chachou, F. K. M. J. Chachou, F. K. Mukinda, V. Motaze, and C. S. Wiysonge, “Electronic and postal reminders for improving immunisation coverage in children: protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis,” BMJ Open, vol. 5, no. 10, p. e008310. [CrossRef]

- “World Health Organization. Global immunization coverage 2019,” www.who.int/news-room/facts-in-pictures/detail/immunization.

- W. H. Organization, “Poliomyelitis Eradication Report by the Director‐General. 74th World Health Assembly. A74/19. 21 April 2021,” apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA74/A74_19‐en.pdf.

- C. S. Wiysonge, “How ending polio in Africa has had positive spinoffs for public health. The Conversation. 3 November 2020,” theconversation.com/africa.

- K. Ramanathan et al., “Since January 2020 Elsevier has created a COVID‐19 resource centre with free information in English and Mandarin on the novel coronavirus COVID‐ research that is available on the COVID‐19 resource centre ‐ including this for unrestricted research re‐use a,” no. January, pp. 19–21, 2020.

- X. Li et al., “Estimating the health impact of vaccination against ten pathogens in 98 low‐income and middle‐income countries from 2000 to 2030: a modelling study,” Lancet, vol. 397, no. 10272, pp. 398–408.

- E. I. Illnesses and M. Visits, “Estimated Influenza‐Related Illnesses , Medical Visits , Hospitalizations , and Deaths in the United States — 2019 – 2020 Influenza Season – Estimates represent data as of October 2021,” no. October, pp. 1–6, 2021.

- D. C. Cassimos, E. Effraimidou, S. Medic, T. Konstantinidis, M. Theodoridou, and H. C. Maltezou, “Vaccination programs for adults in Europe, 2019,” Vaccines, vol. 8, no. 1, p. 34. [CrossRef]

- W. H. Organization, “Table 1: summary of WHO position papers – recommendations for routine immunization; updated September 2020,” www.who.int/immunization/policy/Immunization_routine_table1.pdf.

- P. J. Lu, M. C. Hung, A. Srivastav, L. A. Grohskopf, M. Kobayashi, and A. M. Harris, “Surveillance of vaccination coverage among adult populations – United States, 2018,” MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Surveillance Summaries, vol. 70, no. 3, pp. 1–26, 2021.

- Christie, J. T. Brooks, L. A. Hicks, E. K. Sauber-Schatz, J. S. Yoder, and M. A. Honein, “Guidance for Implementing COVID-19 Prevention Strategies in the Context of Varying Community Transmission Levels and Vaccination Coverage,” MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, vol. 70, no. 30, pp. 1044–1047, 2021. [CrossRef]

- W. H. Organization, “Table 4: summary of WHO position papers – immunization of health care workers; updated September 2020,” www.who.int/immunization/policy/Immunization_routine_table4.pdf. 20 September.

- C. Bonnave, D. Mertens, W. Peetermans, K. Cobbaert, B. Ghesquiere, and M. Deschodt, “Adult vaccination for pneumococcal disease: a comparison of the national guidelines in Europe,” European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases, vol. 38, no. 4, pp. 785–791. [CrossRef]

- U. S. C. for D. C. and Prevention, “Recommended adult immunization schedule for ages 19 years or older. United States, 2021; updated 11 February 2021,” www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/downloads/adult/adult-combined-schedule.pdf.

- S. Cooper, H. van Rooyen, and C. S. Wiysonge, “COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in South Africa: how can we maximize uptake of COVID-19 vaccines?,” Expert Review of Vaccines, vol. July, pp. 1–13. [CrossRef]

- H. C. Maltezou et al., “Vaccination of healthcare personnel in Europe: update to current policies,” Vaccine, vol. 37, no. 52, pp. 7576–7584, 2019. [CrossRef]

- et al; C. for D. C. and P. (CDC), “Immunization of Health-Care Workers: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) and the Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC).” 1997.

- L. Wang, X. L. Wang, X. Zhang, and G. Chen, “Vaccination of Chinese health-care workers calls for more attention,” Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, vol. 16, no. 7, pp. 1498–1501. [CrossRef]

- E. C. for D. P. and Control, “Seasonal influenza vaccination and antiviral use in EU/EEA member states – overview of vaccine recommendations for 2017–2018 and vaccination coverage rates for 2015–2016 and 2016–2017 influenza seasons. Stockholm. ECDC. November 2018,” www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/seasonal-influenza-antiviral-use-2018.pdf.

- G. Solanki, M. G. Solanki, M. Cornell, and R. Lalloo, “Uptake and cost of influenza vaccines in a private health insured South African population.,” Southern African journal of infectious diseases, vol. 33, no. 5, 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Wu, J. Su, P. Yang, H. Zhang, H. Li, and Y. Chu, “Factors associated with the uptake of seasonal influenza vaccination in older and younger adults: a large, population-based survey in Beijing, China,” BMJ Open, vol. 7, no. 9, p. e017459, 2018.

- PneuV 2017, “Adult pneumonia vaccination understanding in Europe: 65 years and over. 17,” www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/ct/publication/documents/2017-10/ipsos-healthcare-pneu-vue-65s-and-over-report_0.pdf. 2017. 20 July.

- B. A. Glenn, N. J. B. A. Glenn, N. J. Nonzee, L. Tieu, B. Pedone, B. O. Cowgill, and R. Bastani, “Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination in the transition between adolescence and adulthood,” Vaccine, vol. 39, no. 25, pp. 3435–3444, 2021. [CrossRef]

- W. W. Williams et al., “Vaccination coverage among adults, excluding influenza vaccination – United States, 2013,” MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, vol. 64, no. 4, pp. 95–102, 2015.

- D. Ndwandwe and C. S. Wiysonge, “COVID-19 vaccines,” Current Opinion in Immunology, vol. 71, pp. 97–104, 2021.

- H. Ritchie, E. Ortiz-Ospina, D. Beltekian, E. Mathieu, J. Hasell, and B. Macdonald, “Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19),” ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations. 2021.

- L. H. Abdullahi, B. M. Kagina, V. N. Ndze, G. D. Hussey, and C. S. Wiysonge, “Improving vaccination uptake among adolescents,” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, vol. 2020, no. 1, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011895.pub2 LK - http://resolver.lib.washington.edu/resserv?sid=EMBASE&issn=1469493X&id=10.1002%2F14651858.CD011895.pub2&atitle=Improving+vaccination+uptake+among+adolescents&stitle=Cochrane+Database+Syst.+Rev.&title=Cochrane+Database+of+Systematic+Reviews&volume=2020&issue=1&spage=&epage=&aulast=Abdullahi&aufirst=Leila+H&auinit=L.H.&aufull=Abdullahi+L.H.&coden=&isbn=&pages=-&date=2020&auinit1=L&auinitm=H.

- J. C. Jacobson Vann, R. M. Jacobson, T. Coyne-Beasley, J. K. Asafu-Adjei, and P. G. Szilagyi, “Patient reminder and recall interventions to improve immunization rates,” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, no. 1, 2018. [CrossRef]

- J. Kaufman et al., “Face to face interventions for informing or educating parents about early childhood vaccination,” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, no. 5, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Oyo-Ita; et al. , “Interventions for improving coverage of childhood immunisation in low- and middle-income countries (Review),” The Cochrane database of systematic reviews, no. 7, p. CD008145, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Saeterdal, S. Lewin, A. Austvoll-Dahlgren, C. Glenton, and S. Munabi-Babigumira, “Interventions aimed at communities to inform and/or educate about early childhood vaccination,” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, no. 11, 2014. [CrossRef]

- S. Wiysonge, T. Young, T. Kredo, M. McCaul, and J. Volmink, “Interventions for improving childhood vaccination coverage in low- and middle-income countries,” South African Medical Journal, vol. 105, no. 11, pp. 892–893, 2015. [CrossRef]

- K. B. Cartmell et al., “Barriers, facilitators, and potential strategies for increasing HPV vaccination: A statewide assessment to inform action,” Papillomavirus Research, vol. 5, pp. 21–31, 2018. [CrossRef]

- C. P. S. T. Force, “Increasing appropriate vaccination: reducing client out-of-pocket costs for vaccinations. Task Force finding and rationale statement,” www.thecommunityguide.org/findings/vaccination-programs-reducing-client-out-pocket-costs.

- E. J. Mavundza, C. J. Iwu‐Jaja, A. B. Wiyeh, B. Gausi, L. H. Abdullahi, and G. Halle‐Ekane, “A systematic review of interventions to improve HPV vaccination coverage,” Vaccines, vol. 9, no. 7, p. 687. [CrossRef]

- K. McKeirnan, K. Colorafi, Z. Sun, K. Daratha, D. Potyk, and J. McCarthy, “Improving pneumococcal vaccination rates among older adults through academic detailing: medicine, nursing and pharmacy partnership,” Vaccines, vol. 9, no. 4, p. 317.

- Oyo-Ita, C. S. Wiysonge, C. Oringanje, C. E. Nwachukwu, O. Oduwole, and M. M. Meremikwu, “Interventions for improving coverage of childhood immunisation in low- and middle-income countries,” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, no. 7. [CrossRef]

- J. Iwu, N. Ngcobo, A. Jaca, A. Wiyeh, E. Pienaar, and U. Chikte, “A systematic review of vaccine availability at the national, district, and health facility level in the WHO African Region,” Expert Review of Vaccines, vol. 19, no. 7, pp. 639–651.

- S. Tankwanchi, B. Bowman, M. Garrison, H. Larson, and C. S. Wiysonge, “Vaccine hesitancy in migrant communities: a rapid review of latest evidence,” Current Opinion in Immunology, vol. 71, pp. 62–68. [CrossRef]

- S. Wiysonge, P. W. Mahasha, D. E. Ndwandwe, N. Ngcobo, K. Grimmer, and J. Dizon, “Contextualised strategies to increase childhood and adolescent vaccination coverage in South Africa: a mixed-methods study,” BMJ Open, vol. 10, no. 6, p. e028476.

- E. Alici et al., “Facilitators and barriers to adult vaccination in South East Asia and Latin America,” Available from epoc.cochrane.org/epoc-specific-resources-review-authors, vol. 74, no. 1, pp. 398–408, 2017. [CrossRef]

- R. Johnson, K. L. Nichol, and K. Lipczynski, “Barriers to adult immunization,” American Journal of Medicine, vol. 12, no. 7 Suppl 2, pp. S28-35, 2008.

- J. Neufeind, C. Betsch, K. B. Habersaat, M. Eckardt, P. Schmid, and O. Wichmann, “Barriers and drivers to adult vaccination among family physicians – insights for tailoring the immunization program in Germany,” Vaccine, vol. 38, no. 27, pp. 4252–4262. [CrossRef]

- M. McNamara, P. O. Buck, S. Yan, L. R. Friedland, K. Lerch, and A. Murphy, “Is patient insurance type related to physician recommendation, administration and referral for adult vaccination? A survey of US physicians,” Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, vol. 15, no. 9, pp. 2217–2226, 2019. [CrossRef]

- B. M. Davis and D. Black, “Facilitators and barriers to adult vaccination in South East Asia and Latin America,” Value in Health, vol. 20, no. 9, p. PA934. [CrossRef]

- C. M. Weyand and J. J. Goronzy, “Aging of the immune system. Mechanisms and therapeutic targets,” Annals of the American Thoracic Society, vol. 13, no. Suppl 5, pp. S422-8.

- R. Masters, A. Hall, J. M. Bartley, S. R. Keilich, E. C. Lorenzo, and E. R. Jellison, “Assessment of lymph node stromal cells as an underlying factor in age-related immune impairment,” Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, vol. 74, no. 11, pp. 1734–1743, 2019. [CrossRef]

- H. L. Thompson, M. J. Smithey, C. D. Surh, and J. Nikolich-Žugich, “Functional and homeostatic impact of age-related changes in lymph node stroma,” Frontiers in Immunology, vol. 8, p. 706, 2017. [CrossRef]

- L. Tan, “Adult vaccination: now is the time to realize an unfulfilled potential,” Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, vol. 11, no. 9, pp. 2158–2166, 2015. [CrossRef]

- S. Cooper, B. M. Schmidt, E. Z. Sambala, A. Swartz, C. J. Colvin, and N. Leon, “Factors that influence parents’ and informal caregivers’ acceptance of routine childhood vaccination: a qualitative evidence synthesis,” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, no. 2. [CrossRef]

- S. Cooper et al., “Factors that influence acceptance of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination for adolescents: A qualitative evidence synthesis,” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, vol. 2019, no. 9, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD013430 LK - http://resolver.lib.washington.edu/resserv?sid=EMBASE&issn=1469493X&id=10.1002%2F14651858.CD013430&atitle=Factors+that+influence+acceptance+of+human+papillomavirus+%28HPV%29+vaccination+for+adolescents%3A+A+qualitative+evidence+synthesis&stitle=Cochrane+Database+Syst.+Rev.&title=Cochrane+Database+of+Systematic+Reviews&volume=2019&issue=9&spage=&epage=&aulast=Cooper&aufirst=Sara&auinit=S.&aufull=Cooper+S.&coden=&isbn=&pages=-&date=2019&auinit1=S&auinitm=.

- C. Lefebvre, J. C. Lefebvre, J. Glanville, S. Briscoe, A. Littlewood, C. Marshall, and M. M-I, “Chapter 4: Searching for and selecting studies. In: Higgins JP, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA, editor(s). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.0 (updated 19). Cochrane, 2019,” Available from training.cochrane.org/handbook/archive/v6. 20 July.

- Jaca, M. Sishuba, J. C. Jacobson Vann, C. S. Wiysonge, and D. Ndwandwe, “Interventions to improve vaccination uptake among adults,” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, vol. 2021, no. 11, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Liberati, D. G. Altman, J. Tetzlaff, C. Mulrow, P. C. Gotzsche, and J. P. Ioannidis, “The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration,” PLoS Medicine, vol. 6, no. 7, p. e1000100, 2009.

- C. E. P. and O. of Care, “Data collection form. EPOC resources for review authors, 2017,” Available from epoc.cochrane.org/epoc-specific-resources-review-authors.

- J. P. Higgins et al., “Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.0 (updated July 2019). Cochrane, 2019,” Available from training.cochrane.org/handbook/archive/v6. 2019.

- E. P. and O. of Care, “Suggested risk of bias criteria for EPOC reviews. EPOC resources for review authors, 2017,” Available from epoc.cochrane.org/epoc-specific-resources-review-authors.

- M. Borenstein, L. V Hedges, J. P. Higgins, and H. R. Rothstein, “When does it make sense to perform a meta-analysis?,” in Introduction to Meta-Analysis, Chichester (UK): John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

- G. H. Guyatt, “GRADE : an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations,” vol. 336, no. April, 2008. [CrossRef]

- C. E. P. and O. of Care, “EPOC worksheets for preparing a ‘Summary of findings’ table using GRADE. EPOC resources for review authors, 2017,” Available from epoc.cochrane.org/epoc-specific-resources-review-authors.

- P. G. Szilagyi et al., “Effect of Personalized Messages Sent by a Health System’sPatient Portal on Influenza Vaccination Rates:a Randomized Clinical Trial.,” J Gen Intern Med, vol. x, no. x, p. x NS-Szilagyi 2021, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Doratotaj, M. L. Macknin, and and S. Worley, “A novel approach to improve influenzavaccination rates among health careprofessionals: A prospectiverandomized controlled trial.,” Am J Infect Control, vol. 36, pp. 301-3 NS-Doratotj 2008, 2008.

- Cochrane Handbok, “Cochrane Handbook,” pp. 25–26, 2024, [Online]. Available: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/PDF/v6.4.

- M. Baker, B. McCaarthy, V. F. Gurley, and M. U. Yood, “Influenza immunization in a managed care organization.,” J Gen Intern Med, vol. 1998, no. 13, pp. 469-475 NS-Baker 1998, 1998. [CrossRef]

- S. L. Cutrona et al., “Improving Rates of Outpatient Influenza Vaccination Through EHRPortal Messages and Interactive Automated Calls: A RandomizedControlled Trial,” J Gen Intern Med, vol. 33, no. 5, pp. 659–67 NS-Cultrona 2018, 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. G. Humiston et al., “Increasing Inner-City Adult InfluenzaVaccination Rates: A RandomizedControlled Trial.,” Public Health Reports, vol. 126, no. 2, pp. 39-47 NS-Humiston 2011, 2011.

- L. P. Hurley et al., “RCT of Centralized Vaccine Reminder/Recall for Adults,” Am J Prev Med, vol. 55, no. 2, pp. 231–239 NS-Hurley 2018, 2018. [CrossRef]

- T. A. Jacobson, D. M. Thomas, F. J. Morton, G. Offutt, J. Shevlin, and S. Ray, “Use of a low-literacy patient education tool to enhance pneumococcal vaccination rates.,” JAMA, vol. 282, pp. 646-650 NS-Jacobson 1999, 1999. [CrossRef]

- H.-S. Juon, C. Strong, F. Kim, E. Park, and S. Lee, “Lay HealthWorker Intervention ImprovedCompliance with Hepatitis B Vaccination inAsian Americans: Randomized ControlledTrial.,” PLOS ONE, vol. xx, no. x, pp. 1-14 NS-Juon 2016, 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. E. Kim, B. J. Turner, J. Steinberg, L. Solano, E. Hoffman, and S. Saluja, “Partners in vaccination: A community-based intervention to promote COVID-19 vaccination among low-income homebound and disabled adults,” Disability and Health Journal, vol. 17, no. 3, p. 101589, 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. S. Klein and N. Adachi, “Pneumococcal Vaccine in the Hospital Improved Use and Implications for High-Risk Patients.,” Arch Intern Med, vol. 143, pp. 1878-1881 NS-Klein 1983, 1983.

- W.-N. Lee et al., “Large-scale influenza vaccination promotion on a mobile app platform: Arandomized controlled trial.,” Vaccine, vol. xxxx, no. xxx, pp. 1-7 NS-Lee 2020, 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. L. Masson et al., “A Randomized Trial of a Hepatitis Care CoordinationModel in Methadone Maintenance Treatment.,” American Journal of Public Health, vol. 103, no. 10, pp. 81-88 NS-Masson 2013, 2013. [CrossRef]

- W. P. Moran, K. Nelson, J. L. Wofford, and R. Velez, “Computer-generated Mailed Remindersfor Influenza Immunization:A Clinical Trial.,” J Gen Intern Med, vol. 7, no. 5, pp. 535-537 NS-Moran 1992, 1992.

- K. Nehme, M. Delphia, E. M. Cha, M. Thomas, and and D. Lakey, “Promoting Influenza Vaccination Amongan ACA Health Plan Subscriber Population:A Randomized Trial.,” American Journal of Health Promotion, vol. 33, no. 6, pp. 916-920 NS-Nehme 2019, 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. T. O’Leary, K. J. Narwaney, N. M. Wagner, C. R. Kraus, S. B. Omer, and J. M. Glanz, “Efficacy of a Web-Based Intervention to IncreaseUptake of Maternal Vaccines: An RCT.,” Am J Prev Med, vol. 57, no. 4, p. e125−e133 NS-O’Leary 2019, 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. H. Otsuka, N. H. Tayal, K. Porter, P. J. Embi, and and S. J. Beatty, “Improving Herpes Zoster Vaccination Rates Through Use of aClinical Pharmacist and a Personal Health Record,” Am J Med., vol. 126, no. 9, pp. 832.e1–832.e6 NS-Otsuka 2013, 2013. [CrossRef]

- A. Reddy et al., “Behaviorally Informed Text Message Nudges to Schedule COVID-19 Vaccinations: A Randomized Controlled Trial,” Journal of General Internal Medicine, no. 012345 6789, 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. Richman, L. Maddy, E. Torres, and and E. J. Goldberg, “A randomized intervention study to evaluate whether electronic messaging canincrease human papillomavirus vaccine completion and knowledge amongcollege students.,” Journal of American College Health, vol. 64, no. 4, pp. 269-78 NS-Richman 2016, 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Siebers and and V. B. Hun, “Increasing the Pneumococcal Vaccination Rate of Elderly Patients in a General Internal Medicine Clinic.,” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, vol. 33, no. 3, pp. 175-178 NS-Siebers 1985, 1985.

- M. S. Stockwell et al., “Influenza Vaccine Text Message Reminders for Urban,Low-Income Pregnant Women: A Randomized Controlled Trial.,” American Journal of Public Health, vol. 104, no. S1, pp. 7-12 NS-Stockwell 2014, 2014. [CrossRef]

- S. Stolpe and and N. K. Choudhry, “Effect of Automated Immunization Registry-BasedTelephonic Interventions on Adult Vaccination Rates inCommunity Pharmacies: A Randomized Controlled Trial,” J Manag Care Spec Pharm., vol. 25, no. 9, pp. 989-94 NS-Stolpe 2019, 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Thomas et al., “Patient education strategies to improve pneumococcal vaccination rates: randomized trial. TT - Journal of Investigational medicine,” J Investig Med, vol. 51, no. 3, pp. 141-148 NS-Thomas 2003, 2003.

- E. Ueberroth, H. R. Labonte, and and M. R. Wallace, “Impact of Patient Portal Messaging Reminderswith Self-Scheduling Option on Influenza Vaccination Rates:a Prospective, Randomized Trial.,” J Gen Intern Med, vol. x, no. x, p. x NS-Ueberroth 2021, 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. Yokum1, J. C. Lauffenburger2, and R. G. and N. K. Choudhr, “Letters designed with behavioural science increase influenza vaccination in Medicare beneficiaries.,” Nature Human Behaviour, vol. 2, no. 10, pp. 743–749 NS-Yokum 2018, 2018.

- M. P. and J. Ward, “Postcard reminders from GPs for influenza vaccine: Are they more effective than an ad hoc approach?,” Journal of Public Health, vol. 22, no. 2, pp. 254-256 NS-Puech 1998, 1998.

- L. K. Mccosker, R. S. Ware, H. Seale, D. Hooshmand, R. O. Leary, and M. J. Downes, “The effect of a financial incentive on COVID-19 vaccination uptake, and predictors of uptake, in people experiencing homelessness : A randomized controlled trial,” Vaccine, vol. 42, no. 10, pp. 2578–2584, 2024. [CrossRef]

- L. Topp et al., “A randomised controlled trial of financial incentives to increase hepatitis B vaccination completion among people who inject drugs in Australia,” Preventive Medicine, vol. 57, no. 4, pp. 297–303, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Q. Ju, H. Xiao, H. Peng, and Y. Gan, “How to Improve People’s Intentions Regarding COVID‐19 Vaccination in China: A Randomized Controlled Trial,” International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, no. 0123456789, 2024, doi: 10.1007/s12529‐024‐10258‐6. [CrossRef]

- S. Coenen et al., “Effects of Education and Information on Vaccination Behavior inPatients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease.,” Inflamm Bowel Dis, vol. 23, pp. 318-324 NS-Coenen 2016, 2016.

- M. Currat and C. L.-B. and G. Zanetti, “Promotion of the influenza vaccination tohospital staff during pre-employmenthealth check: a prospective, randomised,controlled trial.,” Journal of Occupational Medicine and Toxicology, vol. 15, pp. 34 NS-Currat 2020, 2020.

- K. C. Leung et al., “Impact of patient education on influenza vaccine uptake among community-dwelling elderly: a randomized controlled trial.,” Health Education Research, vol. 32, no. 5, pp. 455-464 NS-Leung 2017, 2017.

- Jør. Nexøe and J. K. & T. Rønne, “Impact of postal invitations and user fee oninfluenza vaccination rates among the elderly: Arandomized controlled trial in general practice,” Scand J Prim Health Care, vol. 15, pp. 109-112 NS-Nexeo 1997, 1997.

- K. A. Schmidtke et al., “Randomised controlled trial of atheory-basedintervention to promptfront-linestaff to take up theseasonal influenza vaccine.,” BMJ Qual Saf, vol. 29, pp. 189–197 NS-Schmidtke 2020, 2020.

- S. M. D. Terrell-Perica, P. V Effler, P. M. Houck, L. Lee, and G. H. Crosthwaite, “The Effect of a Combined Influenza/PneumococcalImmunization Reminder Letter.,” Am J Prev Med, vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 256-260 NS-Terrell-Perica 2001, 2001.

- P. L. Hu, E. Y. L. Koh, J. S. H. Tay, V. X.-B. Chan, S. S. M. Goh, and S. Z. Wang, “Assessing the impact of educational methods on influenza vaccine uptake and patient knowledge and attitudes: a randomised controlled trial.,” Singapore Medical Journal, vol. 64, no. 2, pp. 98-104 NS-Pei-Lin 2021, 2023.

- L. Topp et al., “A randomised controlled trial of financial incentives to increase hepatitis B vaccination completion among people who inject drugs in Australia,” Prev Med, vol. 57, no. 4, pp. 297-303 NS-Topp 2013.

- S. (Cindy) S. and V. Dubey, “Addressing vaccine hesitancy Clinical guidance for primary care physicians working with parents.,” Can Fam Physician, vol. 65, no. 3, pp. 175–181, 2019.

- A. Fuller; et al. , “Barriers and facilitators to vaccination uptake against COVID-19, influenza, andpneumococcal pneumonia inimmunosuppressed adults with immune mediated inflammatory diseases: A qualitative interview study during the COVID-19pandemic.,” PLOS ONE, vol. xx, no. xx, pp. 1–14, 2022.

- E. Batteux, F. Mills, L. F. Jones, and C. S. and DaleWeston, “The Effectiveness of Interventions for Increasing COVID-19Vaccine Uptake: A Systematic Review.,” Vaccines, vol. 10, no. 3, p. 386, 2022.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).