Submitted:

21 May 2025

Posted:

21 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

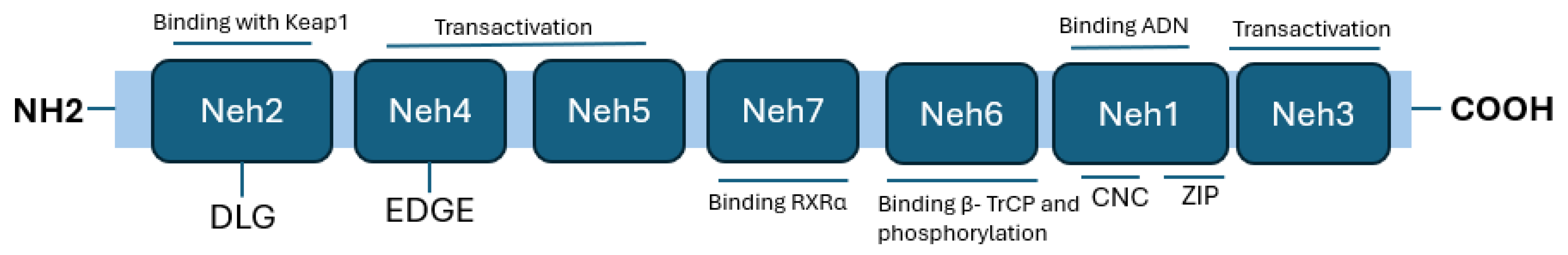

Nrf2 Structure

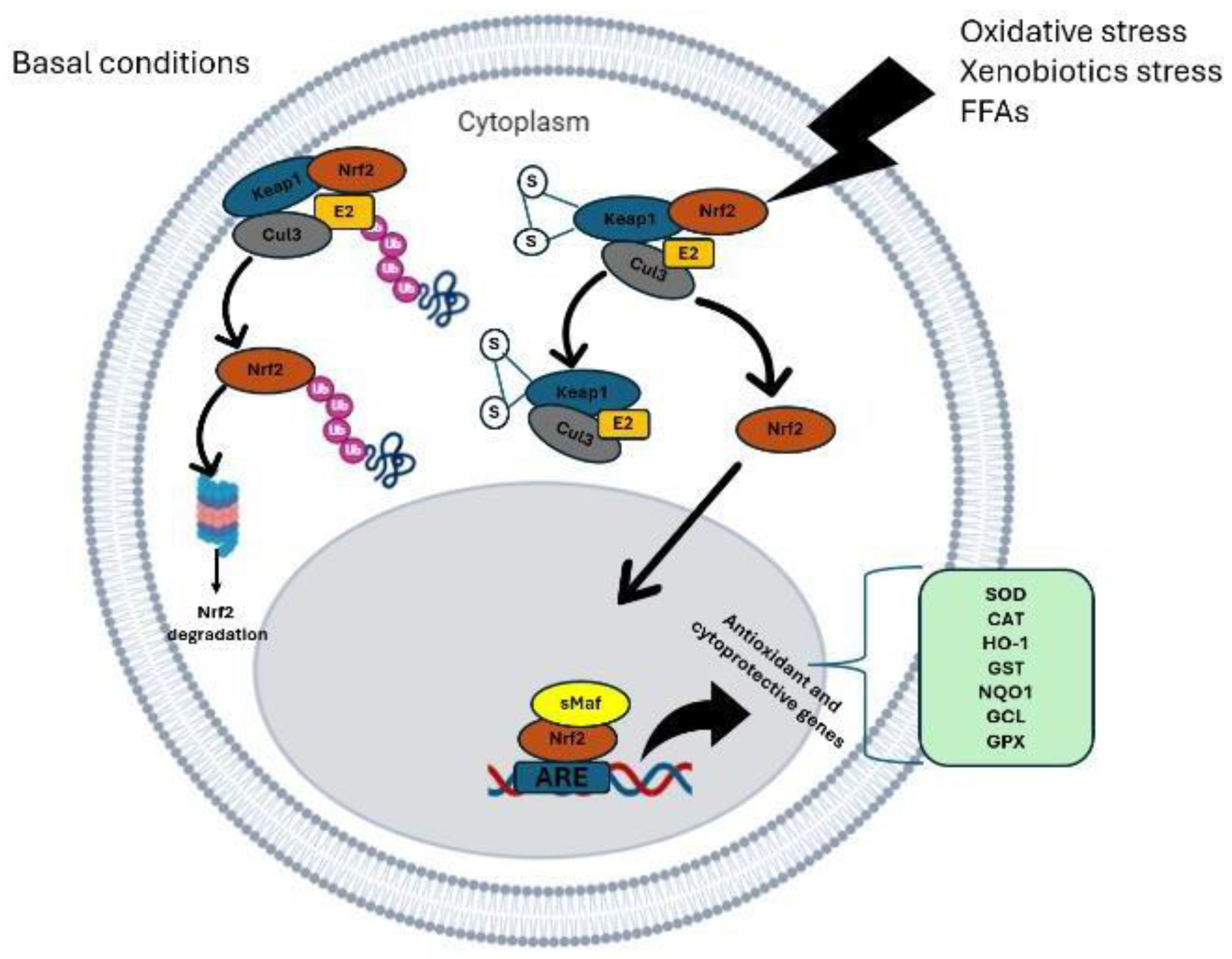

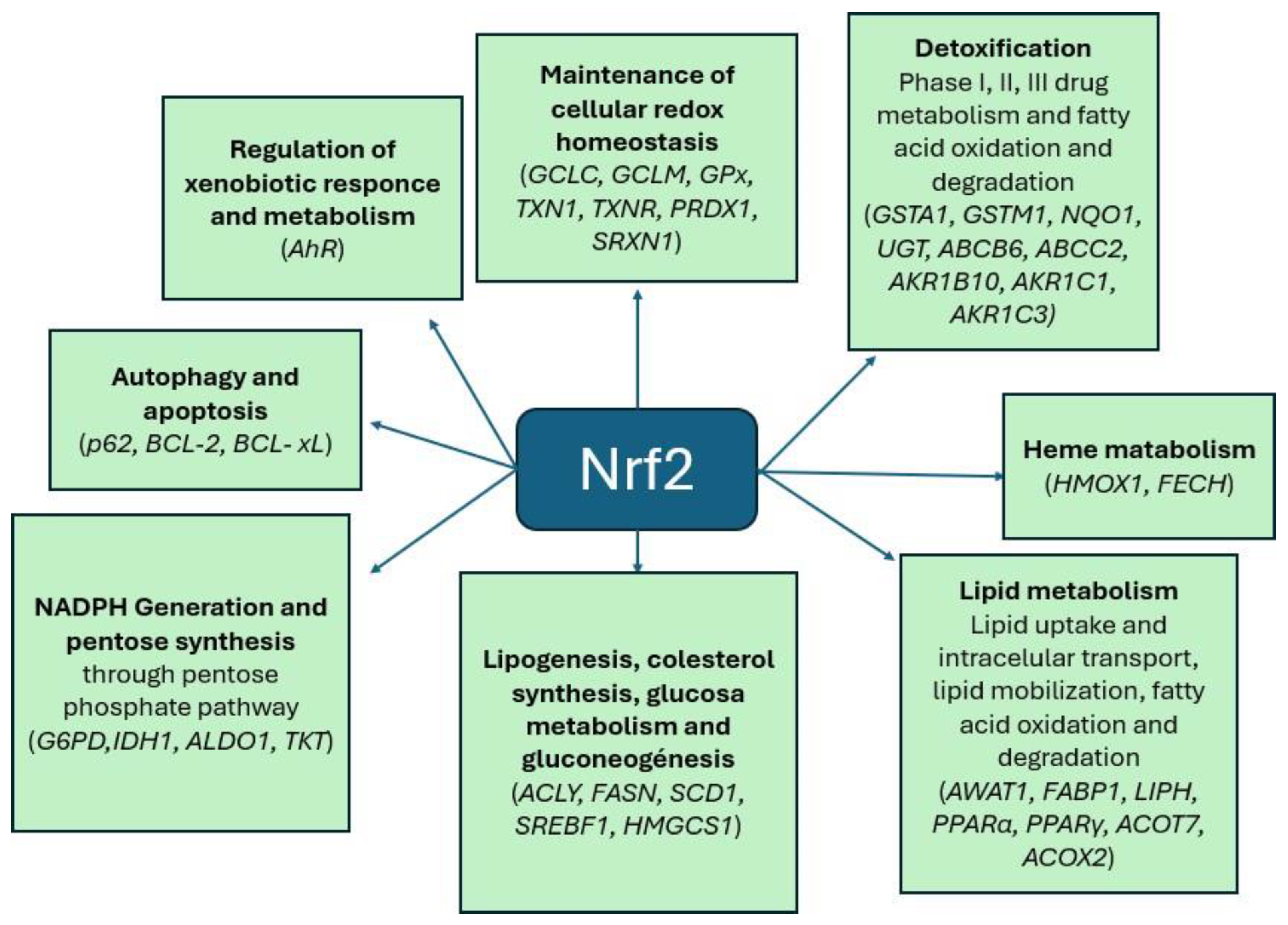

Nrf2 Signaling Pathway

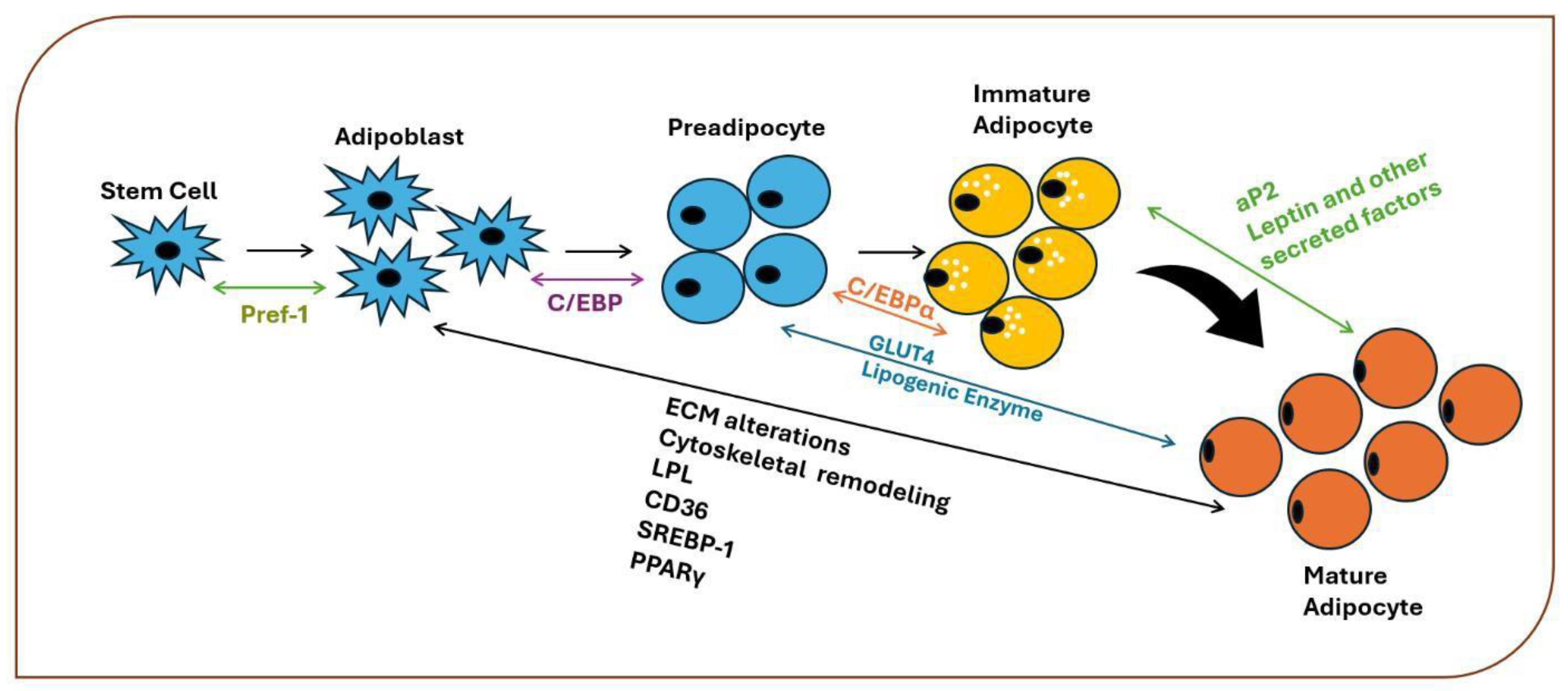

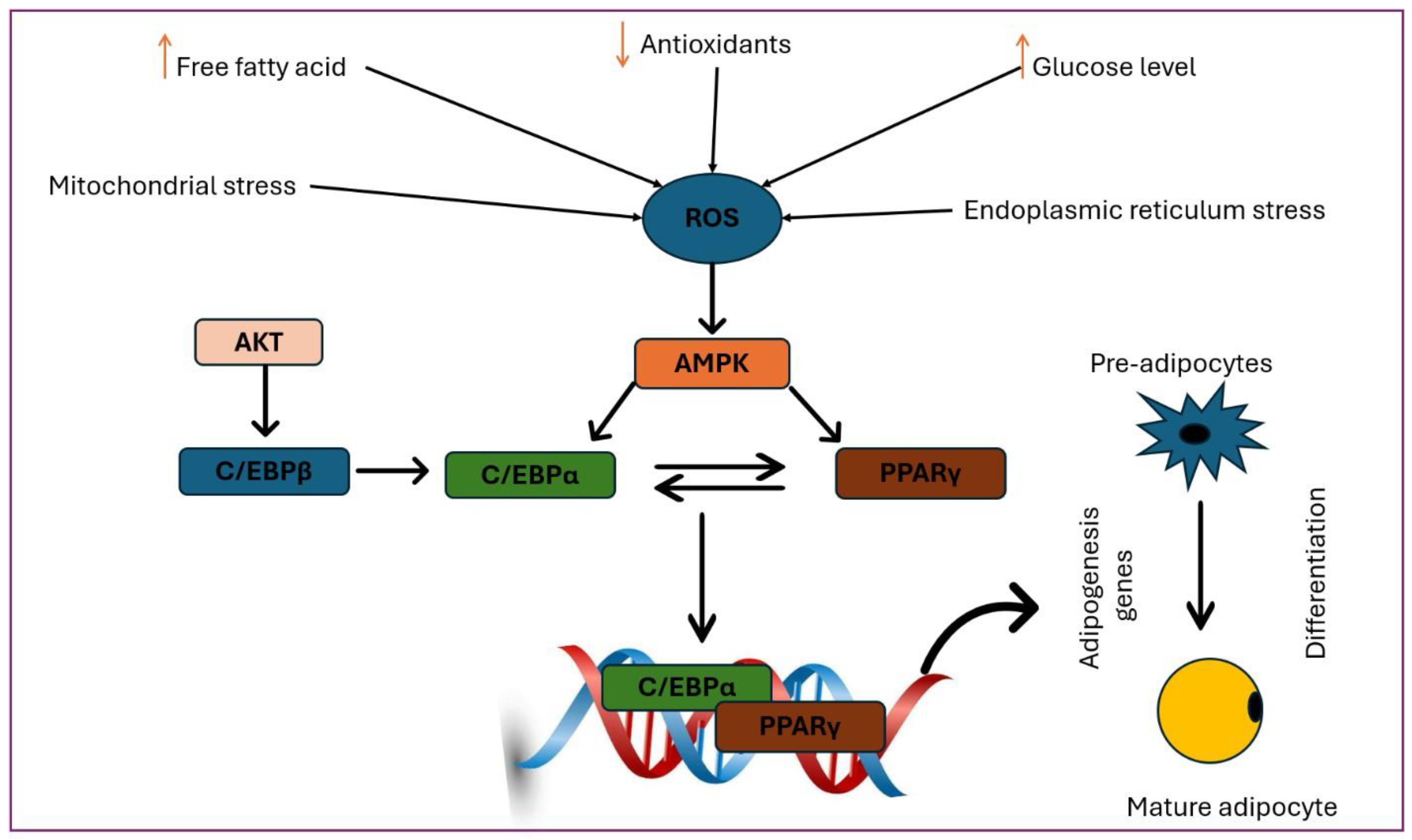

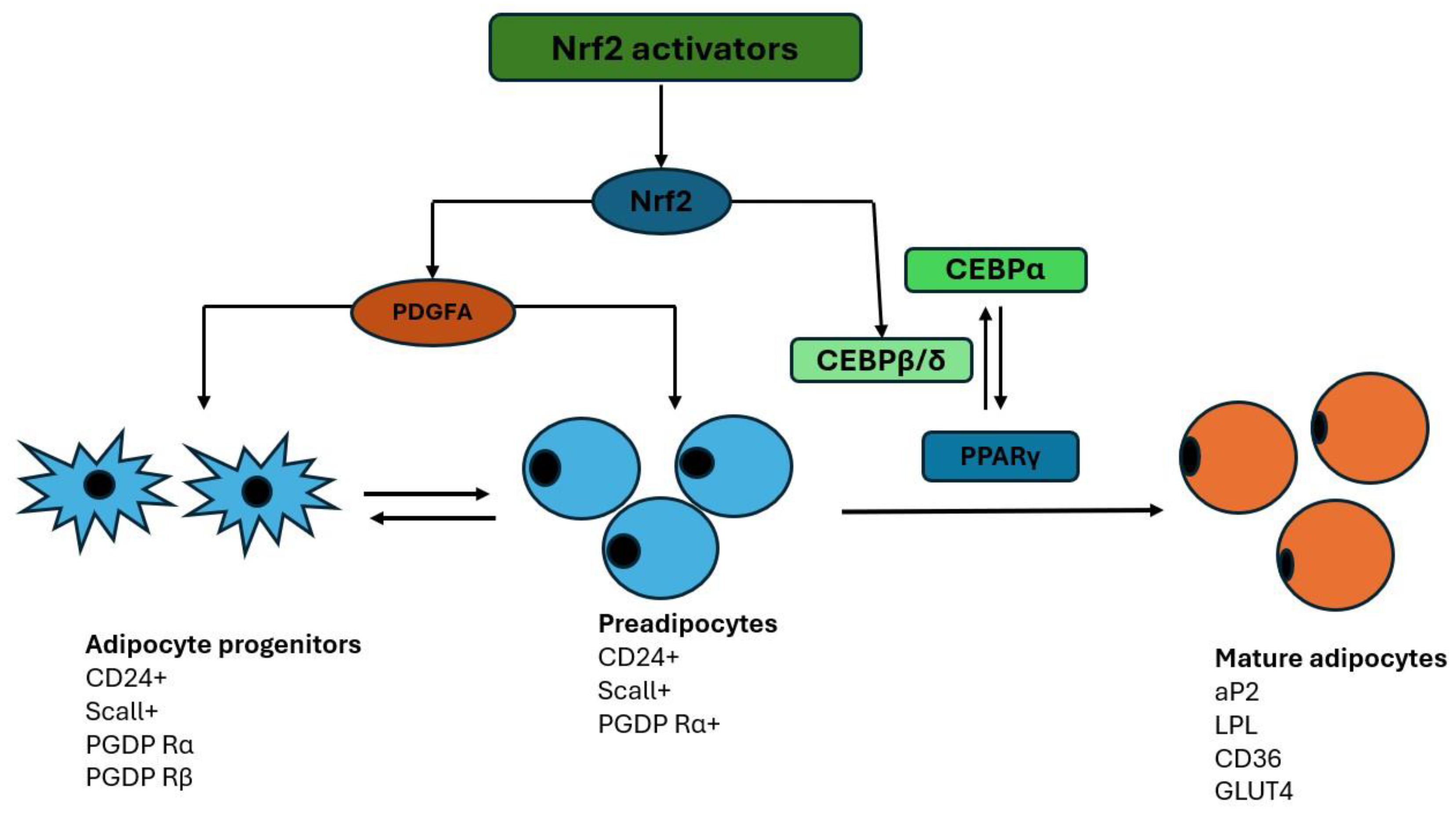

The Role of Nrf2 in the Adipogenesis Process

Nrf2 in the Process of s

Adipose Tissue: Hyperplasia and Hypertrophy

The Adipocyte as an Endocrine Cell

Inflammation of Adipose Tissue and Insulin Resistance Associated with Obesity

Activation of the Nrf2 Signaling Pathway and Metabolic Risk Associated with Obesity

Role of Nrf2 Pathway Agonists

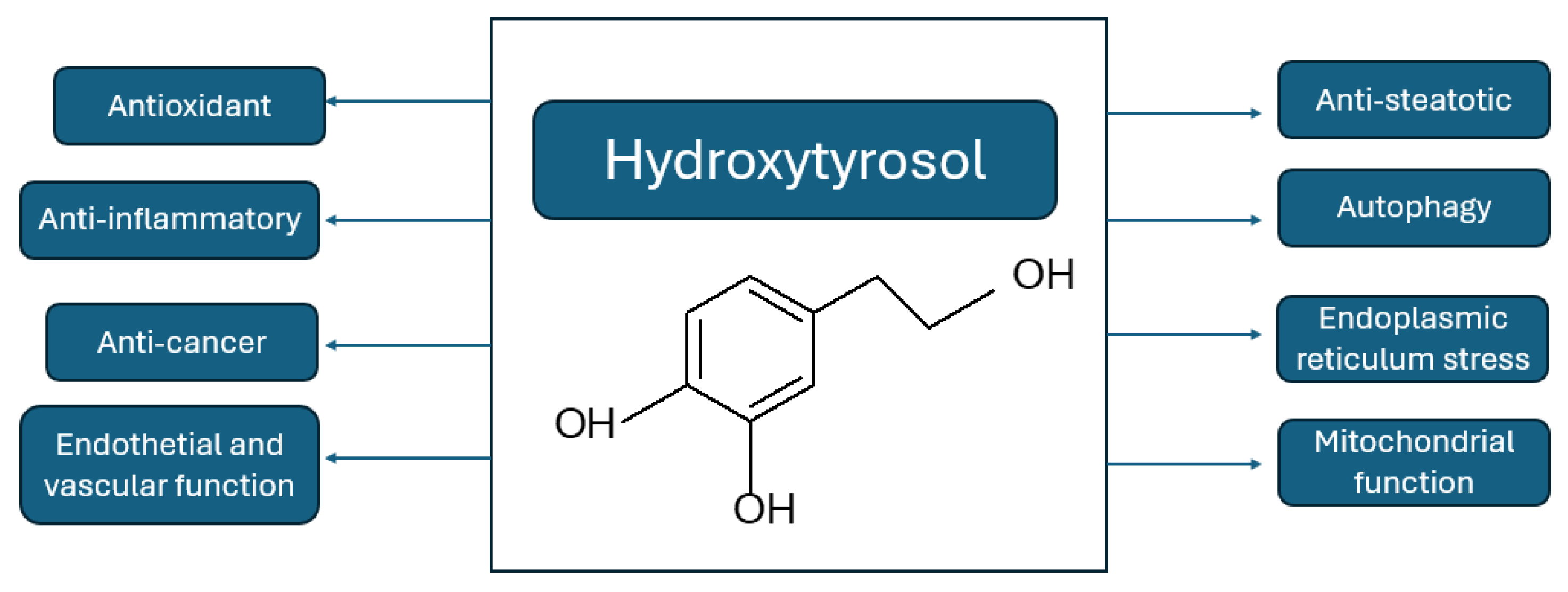

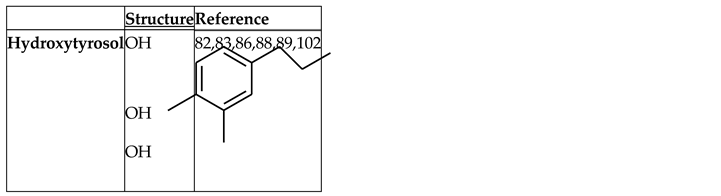

Hydroxytyrosol

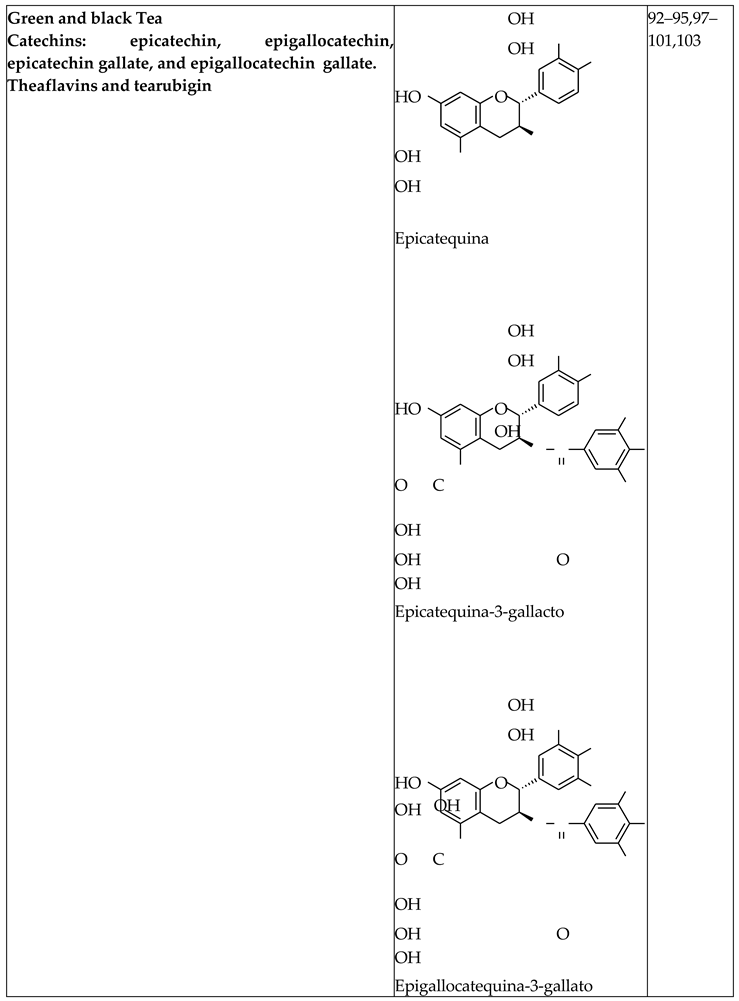

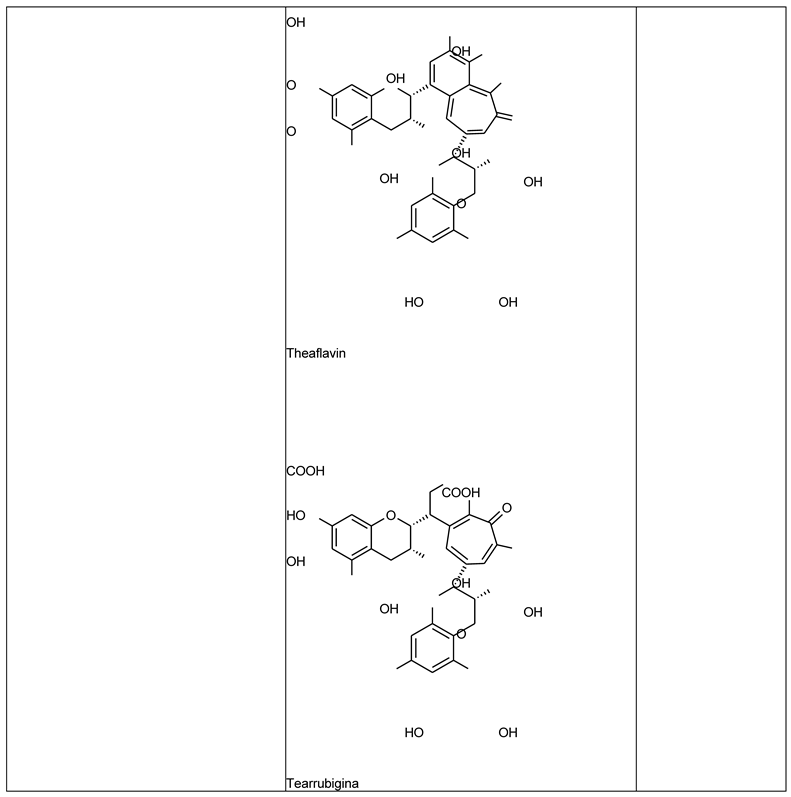

Green and Black Tea Extract

Concluding Remarks

Acknowledgments

References

- AR, J. et al. Health Effects of Overweight and Obesity in.

- 195 Countries over 25 Years. Yearbook of Pediatric Endocrinology (2018). [CrossRef]

- Halpern, B. et al. Obesity and COVID-19 in Latin America: A tragedy of two pandemics—Official document of the Latin American Federation of Obesity Societies. Obesity Reviews vol. 22 Preprint at (2021). [CrossRef]

- Filozof, C., Gonzalez, C., Sereday, M., Mazza, C. & Braguinsky, J. Obesity prevalence and trends in Latin- American countries. Obesity Reviews 2, (2001). [CrossRef]

- Vasileva, L. V., Savova, M. S., Amirova, K. M., Dinkova- Kostova, A. T. & Georgiev, M. I. Obesity and NRF2- mediated cytoprotection: Where is the missing link? Pharmacological Research vol. 156 Preprint at (2020). [CrossRef]

- Lin, X. & Li, H. Obesity: Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, and Therapeutics. Frontiers in Endocrinology vol. 12 Preprint at (2021). [CrossRef]

- Barazzoni, R., Gortan Cappellari, G., Ragni, M. & Nisoli,.

- E. Insulin resistance in obesity: an overview of fundamental alterations. Eating and Weight Disorders vol. 23 Preprint at (2018). [CrossRef]

- Li, S., Eguchi, N., Lau, H. & Ichii, H. The role of the nrf2 signaling in obesity and insulin resistance. International Journal of Molecular Sciences vol. 21 Preprint at (2020). [CrossRef]

- Wondmkun, Y. T. Obesity, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes: Associations and therapeutic implications. Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity vol. 13 Preprint at (2020). [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y., Zhai, X., Qiu, Y., Lu, X. & Jiao, Y. The Nrf2 in Obesity: A Friend or Foe? Antioxidants vol. 11 Preprint at (2022). [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-J. & Jeon, J.-H. Recent Advances in Understanding Nrf2 Agonism and Its Potential Clinical Application to Metabolic and Inflammatory Diseases. Int J Mol Sci 23, 2846 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Ulasov, A. V., Rosenkranz, A. A., Georgiev, G. P. & Sobolev, A. S. Nrf2/Keap1/ARE signaling: Toward specific regulation. Life Sciences vol. 291 Preprint at (2022). [CrossRef]

- Namani, A., Li, Y., Wang, X. J. & Tang, X. Modulation of NRF2 signaling pathway by nuclear receptors: Implications for cancer. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta - Molecular Cell Research vol. 1843 Preprint at (2014). [CrossRef]

- Bruneska Gondim Martins, D., Walleria Aragão Santos, T., Helena Menezes Estevam Alves, M. & Ferreira Frade de Araújo, R. The Role of NRF2 Transcription Factor in Metabolic Syndrome. in The Role of NRF2 Transcription Factor [Working Title] (IntechOpen, 2024). [CrossRef]

- Romano-Lozano, V., Cruz-Avelar, A. & Peralta Pedrero,.

- M. L. Factor nuclear eritroide similar al factor 2 en el vitíligo. Actas Dermosifiliogr 113, 705–711 (2022).

- Da Costa, R. M. et al. Nrf2 as a potential mediator of cardiovascular risk in metabolic diseases. Frontiers in Pharmacology vol. 10 Preprint at (2019). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. et al. The role of the Nrf2/Keap1 pathway in obesity and metabolic syndrome. Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders vol. 16 Preprint at (2015). [CrossRef]

- Annie-Mathew, A. S. et al. The pivotal role of Nrf2 activators in adipocyte biology. Pharmacological Research vol. 173 Preprint at (2021). [CrossRef]

- Menegon, S., Columbano, A. & Giordano, S. The Dual Roles of NRF2 in Cancer. Trends in Molecular Medicine vol. 22 Preprint at (2016). [CrossRef]

- GREGOIRE, F. M., SMAS, C. M. & SUL, H. S.

- Understanding Adipocyte Differentiation. Physiol Rev 78, 783–809 (1998).

- Ambele, M. A., Dhanraj, P., Giles, R. & Pepper, M. S. Adipogenesis: A complex interplay of multiple molecular determinants and pathways. International Journal of Molecular Sciences vol. 21 Preprint at (2020). [CrossRef]

- Huang, C. J. & Choo, K. B. Circular RNA- and microRNA-Mediated Post-Transcriptional Regulation of Preadipocyte Differentiation in Adipogenesis: From Expression Profiling to Signaling Pathway. International Journal of Molecular Sciences vol. 24 Preprint at (2023). [CrossRef]

- Rosen, E. D. & Spiegelman, B. M. Molecular regulation of adipogenesis. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology vol. 16 Preprint at (2000). [CrossRef]

- Moseti, D., Regassa, A. & Kim, W. K. Molecular regulation of adipogenesis and potential anti-adipogenic bioactive molecules. International Journal of Molecular Sciences vol. 17 Preprint at https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms17010124 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Romieu, I. et al. Energy balance and obesity: what are the main drivers? Cancer Causes and Control 28, (2017).

- Su, K. et al. Liraglutide attenuates renal tubular ectopic lipid deposition in rats with diabetic nephropathy by inhibiting lipid synthesis and promoting lipolysis. Pharmacol Res 156, (2020).

- Jia, Y. et al. Increased FGF-21 Improves Ectopic Lipid Deposition in the Liver and Skeletal Muscle. Nutrients 16, 1254 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Vishvanath, L. Vishvanath, L. & Gupta, R. K. Contribution of adipogenesis to healthy adipose tissue expansion in obesity. Journal of Clinical Investigation vol. 129 Preprint at (2019). [CrossRef]

- Lee, K. Y. et al. Developmental and functional heterogeneity of white adipocytes within a single fat depot. EMBO J 38, (2019).

- Cristancho, A. G. & Lazar, M. A. Forming functional fat: A growing understanding of adipocyte differentiation. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology vol. 12 Preprint at (2011). [CrossRef]

- Ambele, M. A., Dhanraj, P., Giles, R. & Pepper, M. S. Adipogenesis: A Complex Interplay of Multiple Molecular Determinants and Pathways. Int J Mol Sci 21, 4283 (2020). [CrossRef]

- MacDougald, O. A. & Lane, M. D. Transcriptional regulation of gene expression during adipocyte differentiation. Annu Rev Biochem 64, (1995).

- Zhang, H. et al. Insulin-like growth factor-1/insulin bypasses Pref-1/FA1-mediated inhibition of adipocyte differentiation. Journal of Biological Chemistry 278, (2003).

- Ailhaud, G. Early adipocyte differentiation. Biochem Soc Trans 24, 400–402 (1996).

- Kumar, R. et al. Association of Leptin With Obesity and Insulin Resistance. Cureus (2020). [CrossRef]

- Al-Mansoori, L., Al-Jaber, H., Prince, M. S. & Elrayess,.

- M. A. Role of Inflammatory Cytokines, Growth Factors and Adipokines in Adipogenesis and Insulin Resistance.

- Inflammation vol. 45 Preprint at (2022). [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. H. et al. The role of adipose tissue mitochondria: Regulation of mitochondrial function for the treatment of metabolic diseases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences vol. 20 Preprint at (2019). [CrossRef]

- Matsushita, K. & Dzau, V. J. Mesenchymal stem cells in obesity: Insights for translational applications. Laboratory Investigation vol. 97 Preprint at (2017). [CrossRef]

- Guo, L., Li, X. & Tang, Q. Q. Transcriptional regulation of adipocyte differentiation: A central role for CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein (C/EBP) β. Journal of Biological Chemistry vol. 290 Preprint at (2015). [CrossRef]

- Haider, N. & Larose, L. Activation of the PDGFRα-Nrf2 pathway mediates impaired adipocyte differentiation in bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells lacking Nck1. Cell Communication and Signaling 18, (2020). [CrossRef]

- Sun, X. et al. Nuclear Factor E2-Related Factor 2 Mediates Oxidative Stress-Induced Lipid Accumulation in Adipocytes by Increasing Adipogenesis and Decreasing Lipolysis. Antioxid Redox Signal 32, (2020).

- Pi, J. et al. Deficiency in the nuclear factor E2-related factor-2 transcription factor results in impaired adipogenesis and protects against diet-induced obesity. Journal of Biological Chemistry 285, (2010).

- Kim, B. R. et al. Suppression of Nrf2 attenuates adipogenesis and decreases FGF21 expression through PPAR gamma in 3T3-L1 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 497, (2018).

- Chen, Y. et al. Isoniazid suppresses antioxidant response element activities and impairs adipogenesis in mouse and human preadipocytes. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 273, (2013).

- Xue, P. et al. Adipose deficiency of Nrf2 in ob/ob mice results in severe metabolic syndrome. Diabetes 62, (2013).

- Chartoumpekis, D. V. et al. Nrf2 deletion from adipocytes, but not hepatocytes, potentiates systemic metabolic dysfunction after long-term high-fat diet-induced obesity in mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 315, (2018).

- Cho, Y. K. et al. Lipid remodeling of adipose tissue in metabolic health and disease. Experimental and Molecular Medicine vol. 55 Preprint at (2023). [CrossRef]

- Khandekar, M. et al. Beige Adipocytes are a Distinct Type of Thermogenic Fat Cell in Mouse and Human. Cell 150, (2013).

- Petito, G. et al. Adipose Tissue Remodeling in Obesity: An Overview of the Actions of Thyroid Hormones and Their Derivatives. Pharmaceuticals vol. 16 Preprint at (2023). [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L. et al. Brown and beige adipose tissue: a novel therapeutic strategy for obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Adipocyte vol. 10 Preprint at (2021). [CrossRef]

- Horwitz, A. & Birk, R. Adipose Tissue Hyperplasia and Hypertrophy in Common and Syndromic Obesity—The Case of BBS Obesity. Nutrients vol. 15 Preprint at (2023). [CrossRef]

- Engin, A. Adipose tissue hypoxia in obesity and its impact on preadipocytes and macrophages: Hypoxia hypothesis. in Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology vol. 960 (2017).

- Al-Sari, N. et al. Lipidomics of human adipose tissue reveals diversity between body areas. PLoS One 15, (2020).

- Meikle, P. J. & Summers, S. A. Sphingolipids and phospholipids in insulin resistance and related metabolic disorders. Nature Reviews Endocrinology vol. 13 Preprint at (2017). [CrossRef]

- Palau-Rodriguez, M. et al. Visceral Adipose Tissue Phospholipid Signature of Insulin Sensitivity and Obesity. J Proteome Res 20, (2021).

- White, U. Adipose tissue expansion in obesity, health, and disease. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology vol. 11 Preprint at (2023). [CrossRef]

- Gu, X., Wang, X., Wang, S., Shen, Y. & Lu, L. Nonlinear association between visceral adipose tissue area and remnant cholesterol in US adults: a cross-sectional study. Lipids Health Dis 23, 228 (2024).

- Cypess, A. M. Reassessing Human Adipose Tissue. New England Journal of Medicine 386, (2022).

- Zhang, Y. et al. Positional cloning of the mouse obese gene and its human homolog. Nature 372, (1994).

- Scheja, L. & Heeren, J. The endocrine function of adipose tissues in health and cardiometabolic disease. Nature Reviews Endocrinology vol. 15 Preprint at (2019). [CrossRef]

- Marseglia, L. et al. Oxidative stress in obesity: A critical component in human diseases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences vol. 16 Preprint at (2015). [CrossRef]

- Małkowska, P. Positive Effects of Physical Activity on Insulin Signaling. Curr Issues Mol Biol 46, 5467–5487 (2024).

- Zatterale, F. et al. Chronic Adipose Tissue Inflammation Linking Obesity to Insulin Resistance and Type 2 Diabetes. Frontiers in Physiology vol. 10 Preprint at (2020). [CrossRef]

- Ormazabal, V. et al. Association between insulin resistance and the development of cardiovascular disease. Cardiovascular Diabetology vol. 17 Preprint at (2018). [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, H. K. R. & Zierath, J. R. Insulin signaling and glucose transport in insulin resistant human skeletal muscle. Cell Biochemistry and Biophysics vol. 48 Preprint at (2007). [CrossRef]

- Samuel, V. T. & Shulman, G. I. The pathogenesis of insulin resistance: integrating signaling pathways and substrate flux. Journal of Clinical Investigation 126, 12– 22 (2016).

- Santoro, A., McGraw, T. E. & Kahn, B. B. Insulin action in adipocytes, adipose remodeling, and systemic effects. Cell Metabolism vol. 33 Preprint at (2021). [CrossRef]

- Patel, R., Varghese, J. F. & Yadav, U. C. S. Crosstalk between adipose tissue, macrophages, and other immune cells: Development of obesity and inflammation-induced metabolic diseases. in Obesity and Diabetes: Scientific Advances and Best Practice (2020).

- Malenica, M. & Meseldžić, N. Oxidative stress and obesity. Arhiv za Farmaciju vol. 72 Preprint at (2022). [CrossRef]

- Capece, D. et al. NF-κB: blending metabolism, immunity, and inflammation. Trends in Immunology vol. 43 Preprint at (2022). [CrossRef]

- Milhem, F., Skates, E., Wilson, M. & Komarnytsky, S. Obesity-Resistant Mice on a High-Fat Diet Display a Distinct Phenotype Linked to Enhanced Lipid Metabolism. Nutrients 16, (2024).

- Di Francesco, A. et al. NQO1 protects obese mice through improvements in glucose and lipid metabolism. NPJ Aging Mech Dis 6, (2020).

- Zhan, X., Li, J. & Zhou, T. Targeting Nrf2-Mediated Oxidative Stress Response Signaling Pathways as New Therapeutic Strategy for Pituitary Adenomas. Front Pharmacol 12, (2021).

- Gutiérrez-Cuevas, J. et al. The Role of NRF2 in Obesity- Associated Cardiovascular Risk Factors. Antioxidants vol.

- 11 Preprint at (2022). [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z. et al. Deletion of Nrf2 leads to hepatic insulin resistance via the activation of NF-κB in mice fed a high- fat diet. Mol Med Rep 14, (2016).

- Chanas, S. A. et al. Loss of the Nrf2 transcription factor causes a marked reduction in constitutive and inducible expression of the glutathione S-transferase Gsta1, Gsta2, Gstm1, Gstm2, Gstm3 and Gstm4 genes in the livers of male and female mice. Biochemical Journal 365, (2002).

- Schneider, K. et al. Increased energy expenditure, ucp1 expression, and resistance to diet-induced obesity in mice lacking nuclear factor-erythroid-2-related transcription factor-2 (nrf2). Journal of Biological Chemistry 291, (2016).

- Sugimoto, H. et al. Deletion of nuclear factor-E2-related factor-2 leads to rapid onset and progression of nutritional steatohepatitis in mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 298, (2010).

- Wakabayashi, N., Yagishita, Y., Joshi, T. & Kensler, T. W. Forced Hepatic Expression of NRF2 or NQO1 Impedes Hepatocyte Lipid Accumulation in a Lipodystrophy Mouse Model. Int J Mol Sci 24, (2023).

- Shin, S. M., Yang, J. H. & Ki, S. H. Role of the Nrf2-are pathway in liver diseases. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity Preprint at (2013). [CrossRef]

- Li, L. et al. Hepatocyte-specific Nrf2 deficiency mitigates high-fat diet-induced hepatic steatosis: Involvement of reduced PPARγ expression. Redox Biol 30, (2020).

- Yi, M. et al. Nrf2 Pathway and Oxidative Stress as a Common Target for Treatment of Diabetes and Its Comorbidities. International Journal of Molecular Sciences vol. 25 Preprint at (2024). [CrossRef]

- Martínez, L., Ros, G. & Nieto, G. Hydroxytyrosol: Health Benefits and Use as Functional Ingredient in Meat. Medicines 5, (2018).

- Micheli, L. et al. Role of Hydroxytyrosol and Oleuropein in the Prevention of Aging and Related Disorders: Focus on Neurodegeneration, Skeletal Muscle Dysfunction and Gut Microbiota. Nutrients vol. 15 Preprint at (2023). [CrossRef]

- Sabatini, N. Recent Patents in Olive Oil Industry: New Technologies for the Recovery of Phenols Compounds from Olive Oil, Olive Oil Industrial by-Products and Waste Waters. Recent Patents on Food, Nutrition & Agriculturee 2, (2012).

- Franconi, F., Campesi, I. & Romani, A. Is Extra Virgin Olive Oil an Ally for Women’s and Men’s Cardiovascular Health? Cardiovascular Therapeutics vol. 2020 Preprint at (2020). [CrossRef]

- Echeverría, F., Ortiz, M., Valenzuela, R. & Videla, L. A. Hydroxytyrosol and cytoprotection: A projection for clinical interventions. International Journal of Molecular Sciences vol. 18 Preprint at (2017). [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-García, C., Sánchez-Quesada, C., Algarra, I. & Gaforio, J. J. Differential Immunometabolic Effects of High-Fat Diets Containing Coconut, Sunflower, and Extra Virgin Olive Oils in Female Mice. Mol Nutr Food Res 66, (2022).

- Cao, K. et al. Hydroxytyrosol prevents diet-induced metabolic syndrome and attenuates mitochondrial.

- abnormalities in obese mice. Free Radic Biol Med 67, (2014).

- Liu, Z., Wang, N., Ma2, Y. & Wen, D. Hydroxytyrosol improves obesity and insulin resistance by modulating gut microbiota in high-fat diet-induced obese mice. Front Microbiol 10, (2019).

- Del Rio, D. et al. Dietary (poly)phenolics in human health: Structures, bioavailability, and evidence of protective effects against chronic diseases. Antioxidants and Redox Signaling vol. 18 Preprint at (2013). [CrossRef]

- Benzie, I. F. F. & Wachtel-Galor, S. Herbal Medicine: Biomolecular and Clinical Aspects: Second Edition. Herbal Medicine: Biomolecular and Clinical Aspects: Second Edition (2011).

- Peluso, I. & Serafini, M. Antioxidants from black and green tea: from dietary modulation of oxidative stress to pharmacological mechanisms. British Journal of Pharmacology vol. 174 Preprint at (2017). [CrossRef]

- Na, H. K. & Surh, Y. J. Modulation of Nrf2-mediated antioxidant and detoxifying enzyme induction by the green tea polyphenol EGCG. Food and Chemical Toxicology 46, (2008).

- Oz, H. S. Chronic inflammatory diseases and green tea polyphenols. Nutrients vol. 9 Preprint at (2017). [CrossRef]

- Wang, D. et al. Green tea polyphenols mitigate the plant lectins-induced liver inflammation and immunological reaction in C57BL/6 mice via NLRP3 and Nrf2 signaling pathways. Food and Chemical Toxicology 144, (2020).

- Surma, S., Sahebkar, A. & Banach, M. Coffee or tea: Anti- inflammatory properties in the context of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease prevention. Pharmacological Research vol. 187 Preprint at (2023). [CrossRef]

- James, A., Wang, K. & Wang, Y. Therapeutic Activity of Green Tea Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate on Metabolic Diseases and Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Diseases: The Current Updates. Nutrients vol. 15 Preprint at (2023). [CrossRef]

- Liu, C. Y. et al. Effects of green tea extract on insulin resistance and glucagon-like peptide 1 in patients with type 2 diabetes and lipid abnormalities: A randomized, double-blinded, and placebo-controlled trial. PLoS One 9, (2014).

- Yu, J., Song, P., Perry, R., Penfold, C. & Cooper, A. R. The effectiveness of green tea or green tea extract on insulin resistance and glycemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus: A meta-analysis. Diabetes and Metabolism Journal vol. 41 Preprint at (2017). [CrossRef]

- De la Fuente-Muñoz, M. et al. Supplementation with a New Standardized Extract of Green and Black Tea Exerts Antiadipogenic Effects and Prevents Insulin Resistance in Mice with Metabolic Syndrome. Int J Mol Sci 24, (2023).

- de Oliveira Assis, F. S., Vasconcellos, G. L., Lopes, D. J. P., de Macedo, L. R. & Silva, M. Effect of Green Tea Supplementation on Inflammatory Markers among Patients with Metabolic Syndrome and Related Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Prev Nutr Food Sci 29, 106–117 (2024).

- Martínez-Zamora, L., Peñalver, R., Ros, G. & Nieto, G. Olive tree derivatives and hydroxytyrosol: Their potential effects on human health and its use as functional ingredient in meat. Foods vol. 10 Preprint at (2021). [CrossRef]

- Wang, D., Wang, T., Li, Z., Guo, Y. & Granato, D. Green Tea Polyphenols Upregulate the Nrf2 Signaling Pathway and Suppress Oxidative Stress and Inflammation Markers in D-Galactose-Induced Liver Aging in Mice. Front Nutr 9, (2022).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).