1. Introduction

Acute aortic dissection presents with a wide spectrum of clinical manifestations, ranging from sudden death at onset to asymptomatic cases. The diversity in symptoms and time course highlights the critical importance of tailoring appropriate treatment strategies for each patient. While Stanford type A dissections often result in early catastrophic events involving the heart and typically require emergency surgery, Stanford type B dissections may also necessitate urgent intervention due to complications, such as rupture or malperfusion of visceral organs or limbs. The traditional treatment approach introduced over 55 years ago remains limited by assigning surgical interventions for type A dissections and medical interventions for type B dissections [

1].

In the past, surgical options for aortic dissection were mainly limited to open aortic repair (OAR), which often led to poor outcomes for type B dissection in emergencies. This reinforced the reliance on the original Stanford classification (1970)-based treatment strategies. However, with the advent of thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR) in 1994 [

2] and subsequent technological advancements, a third treatment option emerged, providing precise, minimally invasive management and has become a standard modality alongside optimal medical treatment (OMT) and OAR. Despite improvements in early outcomes, management of late-phase false lumen expansion has become a primary concern. Globally, treatment strategies still lack consensus, with varied approaches still coexisting in an uncoordinated manner.

Our department adopted TEVAR as a third-line strategy for acute aortic dissection in 2013, establishing a comprehensive management approach for type A and B dissections. Long-term outcomes of this strategy were subsequently reported in 2022 and 2024 for type A and type B dissections, respectively [

3,

4]. For the first time in 55 years since the Stanford classification was proposed, this strategy enabled a unified approach for both types. Consequently, we have named this comprehensive approach “the Oda strategy”.

Consistent with the principles outlined in

Crossing the Quality Chasm [

5], advocacy for the six aims of 21st-century healthcare remains strong, which are also embodied in the Oda strategy. Healthcare must be:

Safe—avoiding injuries to patients resulting from the care that is intended to benefit them.

Effective—delivering scientifically grounded services to those likely to benefit while refraining from providing services to those unlikely to benefit, thus addressing both underuse and overuse.

Patient-centered—providing care that aligns with individual preferences, needs, and values, and ensuring with all clinical decisions guided by patient priorities.

Timely—reducing wait times and harmful delays for both patients and their caregivers.

Efficient—minimizing waste, particularly in the use of equipment, supplies, ideas, and energy.

Equitable —providing care of consistent quality regardless of sex, ethnicity, geographic location, or socio-economic status.

The history of treatment strategies for acute aortic dissection is unraveled, presenting the Oda strategy as the optimal solution.

2. Evolution of Aortic Dissection Treatment: Lessons from the Past

Treatment strategies for this disease over the past 90 years have been summarized, emphasizing what was deemed appropriate and identifying shortcomings in practice from the perspectives of patient selection, anatomical feasibility, and long-term outcomes.

2.1. OMT-Only Era: Before the Advent of Surgical Options

During an era when surgical treatment for aortic dissection was unavailable, patient outcomes were dictated by chance. Data from the International Registry of Aortic Dissection (IRAD) revealed mortality rates for type A dissection: 20%, 30%, 40%, and 50% within 24 h, 48 h, 1 week, and 1 month, respectively, and the patients often continued to succumb as the false lumen expanded or ruptured [

6]. At the time, surgeons probably witnessed patients succumbing to the disease, and assumed that mortality rates, including those for type B dissection, approached 100%. Although the progression of the disease varied, this assumption was ultimately incorrect [

7]. The absence of computed tomography (CT) scans, the challenges associated with diagnosis, and the tendency of patients with milder symptoms not to seek medical attention made it difficult for surgeons to recognize that some individuals survived. These circumstances made it logical to rely entirely on surgical intervention as the next therapeutic strategy. The world’s first surgical intervention for acute aortic dissection was reported in 1935; however, it was not until 30 years later that the first successful rescue surgery was reported [

8].

2.2. Universal OAR Approach: The DeBakey Era

The DeBakey classification proposed that all aortic dissections should be treated surgically, regardless of whether they were in the acute or chronic phase [

9]. At the time, “surgical treatment” specifically referred to OAR without the use of the frozen elephant trunk (FET) technique. This classification was proposed because the surgical techniques varied based on the type of dissection. The authors assumed that, even in type III aortic dissection, all patients would ultimately die if treated with OMT-alone; therefore, it was considered logical at the time to advocate for surgical intervention for all cases. However, this assumption proved incorrect. While their results were considered groundbreaking at the time, it later became apparent that the type III surgical outcomes were suboptimal in many centers. Moreover, only surgical outcomes were reported, while non-intervention outcomes were referenced from another study [

7], casting doubt on the reliability of type III evaluations. However, their contribution as pioneers in this field is enormous. This era marked substantial progress in cardioplegia techniques [

10,

11] and cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) [

12], which collectively contributed to improved cardiac surgery outcomes.

2.3. Stanford Classification and its Enduring Influence

The Stanford classification of aortic dissection categorizes dissections into type A and B. A study reported for the first time that certain patients could survive without surgery [

1], although it included only 35 patients. For 55 years, this disease has been treated in many facilities with straightforward strategies, such as OAR and OMT for type A and B dissections, respectively. This report, despite its limited sample size, underscores the need to reconsider the use of OAR in type B aortic dissection cases. This classification has undoubtedly brought significant benefits to the field, contributing to improved outcomes. The preference for OMT-alone in type B dissections was not because future interventions were deemed unnecessary, but rather because the surgical techniques available at the time yielded poor results, making non-surgical treatment the preferred option for managing the acute phase. However, this classification may have led to the misconception that OMT-alone was the best treatment strategy for type B dissections, which potentially delayed the widespread use of TEVAR intervention.

Prior to introduction of TEVAR, type B aortic dissection was generally managed with OMT-alone. Although OAR was occasionally performed in severe cases, the outcomes remained suboptimal for a considerable period.

Overtime, it became apparent that the remaining false lumen expanded. To address this phenomenon, the placement of an “original elephant trunk” during the initial arch replacement for type A aortic dissections was proposed in 1983, intended to facilitate future thoracic descending or thoracoabdominal replacement procedures [

13].

2.4. Modernization of OAR: Technological Advances and New Challenges

During this period, the evolution of treatment was primarily driven by improvements in the outcomes of OAR for type A dissections. Advancements such as the development of multi-detector CT [

14,

15], trans-thoracic and trans-esophageal echocardiography [

16], selective cerebral perfusion (SCP) [

17,

18], sophisticated prosthetic grafts [

19], various adhesives [

20,

21], improved anastomosis techniques [

22,

23], and the introduction of platelet transfusion [

24], significantly contributed to better outcomes in patients presenting with type A aortic dissections.

As a result of improvements in early outcomes for patients with acute aortic dissection, it has become increasingly clear that the residual false lumen in patients with post type A aortic dissection and in those with type B aortic dissection confers potential risks of thoracoabdominal replacement in the future. The dilemma was, though ascending aortic replacement had a relatively low mortality rate, it was more prone to distant false lumen expansion. In contrast, replacement up to the aortic arch increased the mortality rate but was less likely to result in distant false lumen expansion [

25,

26].

2.5. The Rise of Stent Grafts: TEVAR and FET

The first clinical application of a stent graft for abdominal aortic aneurysm was performed in 1991 [

27]. Two types of stent grafts were developed for the thoracic aortic region and were reported nearly simultaneously. These include TEVAR, which uses a catheter-based delivery system (first reported in 1994) [

2], and FET, which employs a manual-based delivery system (initially referred to as “open stent graft” in the first report in 1996) [

28]. FET has been actively used, particularly in Germany [

29], China [

30], and Japan [

31], owing to its ability to be visually inserted during surgery, its simple handmade structure, and its ease of placement for OAR surgeons. However, globally, including in the aforementioned countries, OAR and TEVAR surgeons have gradually become separate teams, making it challenging to understand the advantages and disadvantages of each technique, as well as their optimal applications in different situations.

2.6. Clinical Acceptance of TEVAR for Complicated Type B Dissection

In the early stages, many centers were skeptical about the use of TEVAR for acute aortic dissections. Early stent grafts were primitive in design, predominantly handmade at individual facilities, with delivery systems that were thick, inflexible, and non-hydrophilic. At this stage, its use was considered a high-risk procedure. However, the use of TEVAR gained justification due to poor outcomes of OAR for complicated type B aortic dissections. Some facilities took on the challenge of employing TEVAR, and overtime, its effectiveness was reported [

32]. Although the initial mortality rates were relatively high, some life-saving cases were reported. Therefore, combined with revolutionary advancements in commercial device technology, TEVAR has currently evolved into the preferred first-line treatment approach for Class I indications in complicated type B acute aortic dissections [

33].

2.7. FET: Limitations, Complications, and Ethical Concerns

There are three points to consider when evaluating stent grafts including TEVAR and FET for aortic dissection:

Can stent grafts prevent false lumen expansion in cases with false lumen expansion?

Are not unnecessary stent grafts used in cases with no false lumen expansion?

Is the frequency of complications from stent grafts acceptable?

The adoption of FET during the initial OAR for acute type A dissection was driven by the hope of achieving a more extensive one-stage surgery for the thoracic aorta and improving long-term outcomes. However, this approach lacked a solid pathological rationale from the outset. Blindly deploying a stent in a fragile, dissected aorta during the acute phase is inherently risky and has led to severe early and late complications overtime. These include paraplegia [

34,

35], distal stent graft-induced new entry (dSINE) [

36,

37], and kinking [

38,

39] caused by spring-back force [

40], malalignment, or oversizing. Furthermore, false lumen expansion requiring intervention occurs in <30% of patients following tear-oriented surgery [

3,

41,

42]. This indicates that FETs are often implanted in patients who may not have needed them, raising significant ethical concerns. Consequently, the routine use of FET in such cases constitutes overtreatment, unnecessarily exposing patients to potential risks. Despite these issues, certain treatment guidelines have continued to endorse these strategies, exacerbating confusion in clinical practice [

33]. Further concerns arise when TEVAR is performed for complications such as dSINE following FET. Specifically, the placement of an exoskeletal stent graft inside an endoskeletal FET can result in structural mismatches and dangerous gaps. The persistent endorsement of such technically flawed and ethically questionable approaches reveals a lack of critical evaluation in the development of these strategies.

2.8. Reassessing the INSTEAD-XL Trial: Insights into Preemptive TEVAR

Shortly after the turn of the 21st century, challenging research on preemptive TEVAR, specifically the INSTEAD-XL trial, was conducted using relatively primitive devices for patients with uncomplicated type B aortic dissection [

43]. These first-generation TEVAR devices lacked adequate flexibility and compliance, which increased the risk of severe complications, including death, when applied to the fragile aortic walls in the acute or subacute phase. Furthermore, a major ethical concern was that, at the time of enrollment, it was impossible to distinguish between patients who would develop false lumen expansion and those who would not. Based on the findings reported in 2024 [

4], among patients with uncomplicated type B aortic dissection, approximately 30% of patients had progressive false lumen expansion, while 70%, remained stable without requiring intervention.

In this trial, 140 patients were randomized into two groups: OMT + TEVAR (72 patients), and OMT-alone (68 patients). Statistically, this meant that TEVAR was performed on patients who would eventually need it (30%) and was performed on those who would not (70%). Conversely, 30% of patients in the OMT-alone group did not undergo TEVAR despite requiring it, whereas 70% were appropriately managed without intervention. Consequently, appropriate treatment was administered in only 30% of patients in the OMT + TEVAR group, and 70% in the OMT-alone group (

Figure 1). Therefore, the trial design was structurally biased against the OMT + TEVAR arm. Predictably, the OMT + TEVAR group showed worse outcomes during the first 2 years.

However, at 5 years, the survival benefit of OMT + TEVAR became apparent. This reversal strongly suggests that TEVAR is effective when performed on the right patients at the appropriate time. The implication is clear: had TEVAR been performed in only 30% of patients who genuinely required it—based on documented false lumen expansion—and using modern, flexible, and safe devices, the results would likely have been significantly more favorable. Despite its limitations, the INSTEAD-XL trial provides valuable evidence supporting the selective use of TEVAR in cases of false lumen expansion. A common misconception is that the poorer prognosis of the OMT-alone group, compared to the TEVAR group, was due to the subpar quality of OMT. Even if the quality of OMT had been inadequate, its effects would have been consistent across both groups, indicating that the treatment methodology itself was not flawed.

Furthermore, the aforementioned trial highlights a critical challenge in conducting randomized controlled trials (RCTs) for acute aortic dissection. Disease progression can deteriorate considerably over time, even in patients initially diagnosed with uncomplicated type B aortic dissection. Since randomization was conducted based on each patient’s predicted prognosis at enrollment, individuals with intrinsically different prognoses were assigned to the same treatment arm. This design flaw can result in ethically and clinically inappropriate treatment allocation, as exemplified in this trial. Given the diversity of outcomes in acute aortic dissection, RCT research is unlikely to be suitable for this disease. Instead, it would be more clinically meaningful to demonstrate outcomes of many consecutive cases wherein a consistent strategy is applied, including those in which a treatment was applied as well as those in which it was not. In this aspect, our research is also highly valuable [

3,

4].

2.9. When to Intervene: Challenges in Timing TEVAR

With the exception of our studies [

3,

4], almost all published reports have exclusively focused on patients who underwent TEVAR, neglecting the outcomes of those who did not. Notably, these studies fail to explain how patients without false lumen expansion were identified and excluded, thereby limiting the clinical relevance of their findings. Despite these methodological shortcomings, several reports have concluded that TEVAR yields better outcomes when performed during the subacute phase compared to the acute or chronic phases [

44,

45,

46]. Current guidelines have also adopted this perspective [

33]. For example, the VIRTUE Registry highlights that TEVAR performed in the subacute phase (15–92 days from onset) was linked to the best prognosis, while interventions performed during the acute (< 14 days), or chronic (>92 days) phase were linked to poorer outcomes [

44]. However, TEVAR is unnecessary in the absence of false lumen expansion. Therefore, the key clinical question is whether false lumen expansion occurs in patients without acute complications. In this context, whether a case is classified as a subacute or chronic category becomes a secondary consideration. Even if the subacute phase is deemed optimal, performing TEVAR during this window without confirmed false lumen expansion is inappropriate. Therefore, intervention is justified only when clear signs of expansion are present, even if more than 92 days have passed since the onset.

2.10. Advances in TEVAR Technology: The GORE CTAG System

In 2017, the conventional GORE

® Thoracic Endoprosthesis was significantly improved and reinforced in Europe, followed by US and Japan in 2019, as the GORE

® TAG

® Conformable Thoracic Stent Graft with ACTIVE CONTROL System (GORE

® CTAG, W.L. Gore & Associates, Inc., Flagstaff, AZ, USA) [

47,

48]. Compared to conventional unsheathe-type devices, this sleeve-type device features enhanced flexibility and conformability, allowing it to adapt to the aortic curvature. The CTAG employs a staged deployment system: the primary deployment expands the device from the leading to trailing ends to an intermediate diameter, followed by the secondary deployment, which expands it from the trailing to leading ends to its full diameter.

The primary advantage of this system is that it avoids fully occluding the aorta during deployment, thereby minimizing the risk of retrograde type A aortic dissection (RTAD) due to transient hypertension in the upper body, a complication commonly associated with traditional unsheathe-type devices. Particularly, for arch TEVAR, the proximal angulation control feature is essential for achieving a highly coaxial deployment, and the CTAG is currently the only device equipped with this functionality.

This technologically advanced and highly controllable device significantly outperforms FET in terms of precision and safety. Unlike FET, which is inserted blindly during OAR and is prone to being positioned in suboptimal locations, such as curved segments or near distal tears, thereby increasing the risk of complications. However, the CTAG facilitates accurate and intentional placement, making it an essential device in the Oda strategy.

3. The Oda Strategy: A Selective, Evidence-Based Paradigm

3.1. The Core Principle and Treatment Algorithm of the Oda Strategy

Careful interpretation of the INSTEAD-XL trial has laid the foundation for a rational and selective treatment approach that has been developed and refined since 2013 [

3,

4]. In line with the six aims of 21st-century healthcare [

5], the emphasis was on providing necessary medical care to patients who need it, while avoiding providing excessive medical care to patients who do not need it. The basic premise is that OMT is performed appropriately for all patients.

The core principle of the Oda strategy is based on the observation that late-phase false lumen expansion occurs in only 20–30% [

3,

41,

42] and 20–50% [

4,

49] of post-type A and B dissections, respectively. Therefore, patient selection is crucial for improving outcomes. For both initial OAR and TEVAR in type A and B dissections, respectively, the focus was on minimizing the extent of replacement or sealing to reduce the invasiveness and complications. All cases were carefully monitored for false lumen expansion using enhanced CT imaging; TEVAR was selectively performed in patients with progressive expansion, thereby avoiding unnecessary interventions in stable patients. This rational and patient-centered approach improved clinical outcomes compared to existing literature and eliminated the need for subsequent thoraco-abdominal replacement, which once considered inevitable, in almost all patients (

Figure 2) [

3,

4].

3.2. Definition of False Lumen Expansion and How to Measure it

Although several risk factors associated with an increased likelihood of false lumen expansion have been reported [

33], these primarily include quantifiable measurements such as tear size, number, and single-point diameter measurements. However, these factors are considered as reference information only, as the fragility of the adventitia and lifestyle management, which are the most important factors influencing false lumen expansion cannot be quantified. Ultimately there is no alternative to directly measuring and confirming false lumen expansion over time through enhanced CT imaging.

TEVAR is performed exclusively in patients with confirmed false lumen expansion, defined as >5 mm over 6 months [

3,

4]. Since intimal tears can occur at any location unexpectedly, expansion should be assessed across the entire thoracic aorta and in all directions (axial, sagittal, or coronal). Specifically, the appropriate location and view for evaluating false lumen expansion differ between patients (

Figure 3). False lumen expansion is often only visible in the long diameter direction, and thus, measuring the maximum short diameter is meaningless, because this condition is completely different from true aneurysms. Furthermore, even if there is no difference in the outer diameter, it is important to be careful in cases where the proportion of false lumen increases, and true lumen becomes narrower.

Next, we accurately identify where the tears contribute to false lumen expansion. During the acute phase, it is difficult to precisely identify the tear location because the intimal flap flutters; however, this location gradually becomes clearer from the subacute phase onwards. Once the tear contributing to false lumen expansion has been identified, TEVAR is planned so that the tear can be reliably closed and both ends are positioned appropriately. The need for debranching of the left common carotid and the left subclavian arteries and for coiling of the left subclavian artery are also considered.

Furthermore, the rate of false lumen expansion (>5mm/6 months) is important. This does not mean that we should wait 6 months before evaluation; if there is an expansion of >2.5 mm in 3 months or >1 mm in 1 month, it should be noted that there is a tendency of false lumen expansion. This information should be shared with the patient, and OMT should be performed thoroughly. Once the condition for false lumen expansion is met, TEVAR should be performed promptly; however, it is also important to share information on the tendency of false lumen expansion with patients and to encourage them to make efforts to avoid TEVAR.

It is also important to recognize that TEVAR is not necessary in patients without false lumen expansion, whose proportion reaches 70–80% [

3,

41,

42] in uncomplicated post type A and 50–80% [

4,

49] in uncomplicated type B patients.

3.3. The Role of the Aortic Hiatus and Timing TEVAR

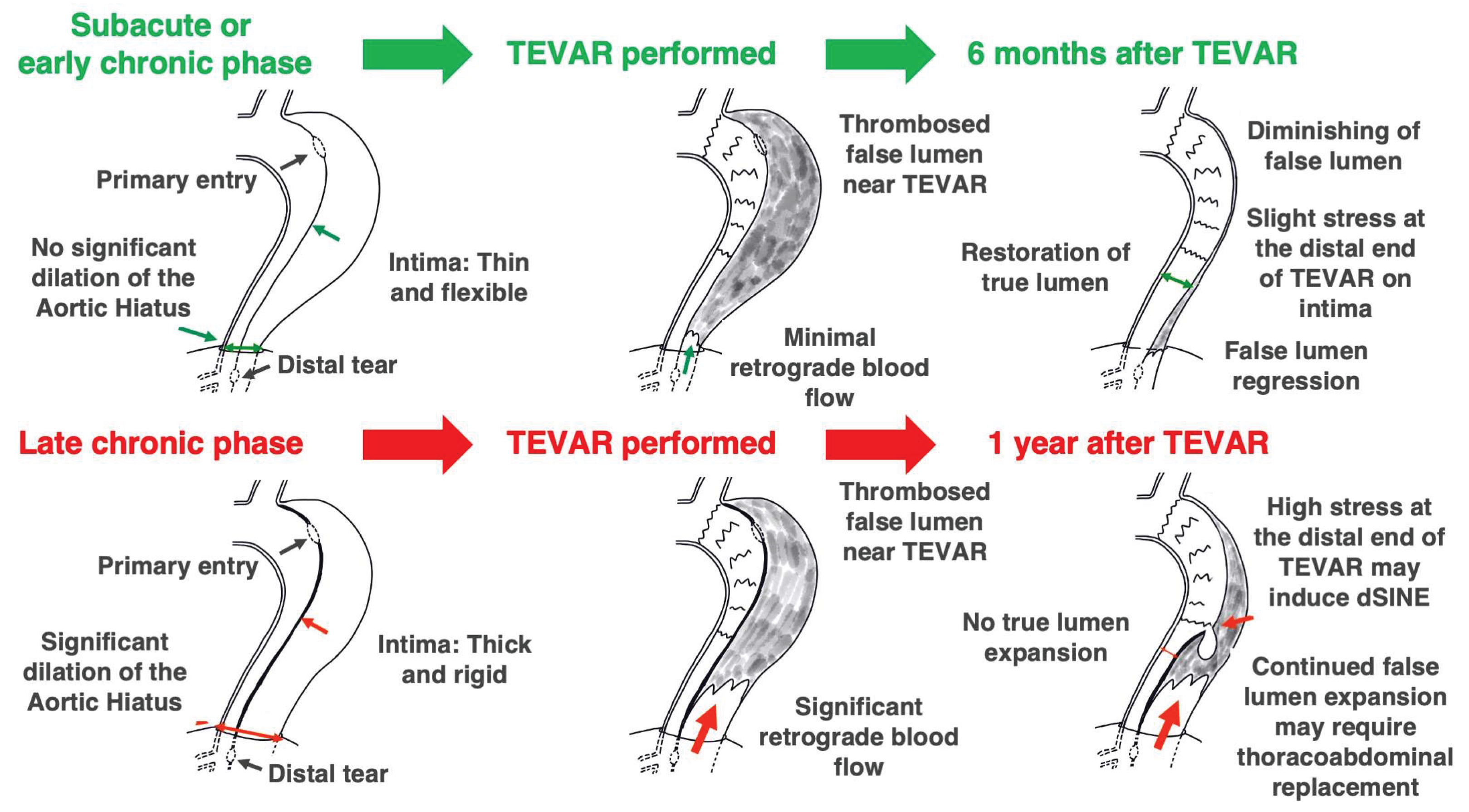

One puzzling aspect of the INSTEAD-XL trial was that TEVAR was only performed on the thoracic descending aorta, yet there was little need for subsequent interventions on the abdominal aorta. Certain reports [

3,

4], were among the earliest to highlight the anatomic role of the aortic hiatus, through which the aorta passes the diaphragm, as a key factor affecting the long-term prognosis of acute aortic dissection (

Figure 4). This important observation gives us confidence in the validity of the Oda strategy. If the false lumen pressure above the aortic hiatus does not decrease owing to patent tears, the false lumen of the thoracic descending aorta continues to expand. If the tear is properly closed in a timely manner and the false lumen pressure decreases, the true lumen pressure may increase accordingly and the lumen size naturally normalized.

We have previously reported the differences in the feasibility of false lumen expansion between the thoracic descending aorta and abdominal aorta [

3,

4]. When tears were present only in the thoracic descending aorta, TEVAR was performed in 93% cases; however, when tears were present only in the abdominal aorta, TEVAR was not necessary. The previous study speculated that the mechanism behind this phenomenon may be a difference in the surrounding structures. There is almost no tissue around the thoracic descending aorta; on the contrary, the abdominal aorta, especially its upper part, is entangled with lymph nodes and plexus, and it has large branches, such as the celiac trunk and superior mesenteric artery. The study also speculated that blood flow from the tear flows into the branches originating from the false lumen, making it difficult for the false lumen pressure to increase. Further research into this hypothesis is expected.

3.4. Creating a System for Timely Therapeutic Intervention

Type A and B aortic dissections are managed from onset by cardiovascular surgeons who oversees the case from diagnosis and determines the optimal timing for intervention. To enable this approach effectively, proficiency in both OAR and TEVAR is essential. Surgeons skilled in both procedures can make informed decisions and tailor the treatment plans to each patient’s unique pathology. If OAR and TEVAR are performed by different teams, close coordination between the teams becomes necessary. Future generations of thoracic aortic specialists must be trained in both skillsets to uphold the highest standards of care.

In outpatient and emergency settings, the ability to examine patients with aortic dissection is vital. The cardiovascular surgery team should share a rapid decision-making process from diagnosis to treatment. In our department, the division of roles within the team is clearly defined [

50].

Additionally, a regional network has been established to ensure timely referrals. In Iwate Prefecture, the institution has established formal communication with over 1,600 primary care and cardiology centers, emphasizing the importance of promptly transferring both type A and type B cases to the surgical team. This systematic outreach has contributed to optimized patient outcomes and reduced delays in care.

3.5. Building an In-Facility Database for Acute Aortic Dissection and Data Analysis

Every institution usually has and maintains a database of patients with type A aortic dissection who have undergone surgery. However, patients with type A or B aortic dissection who did not undergo surgery, are often not registered; such patients should be registered. It is necessary to register all patients with this disease, including those who did not undergo OAR or TEVAR, and to evaluate the appropriateness of treatment choices in both patients who underwent surgery and those who did not. One of the most important aspects of our past study [

4] is that it showed that the long-term prognosis was equally good for both patients who underwent TEVAR and those for whom it was not necessary.

We use Claris FileMaker Pro, latest version (Claris international Inc., CA, USA) to build the database; after receiving approval from the Institutional Review Board, all statistical analyses are performed using JMP, latest version (SAS Institute, Inc., NC, USA) and on consultation with statistical experts.

3.6. Importance of Anti-Hypertension and Lifestyle Management

OMT includes both pharmacological treatments, primarily antihypertensives, and lifestyle modifications. Enduring patient adherence to blood pressure control and healthy habits is vital in preventing false lumen expansion. Patients with a tendency for false lumen expansion, even during the subacute phase, often experience cessation of this progression after adopting improved lifestyle practices, such as avoiding heavy lifting (>10 kg), reducing their workload, and addressing constipation. These anti-hypertension and lifestyle improvements are especially important if there is a tear in the lower part of the thoracic descending aorta or shaggy aorta [

51] and there is a risk of paraplegia with TEVAR intervention.

3.7. Respect for the Patient’s Right to Self-Determination

In accordance with the six aims of 21st-century healthcare [

5], when patients make decisions regarding treatment, they are given a full explanation of the disease and treatment methods, including OAR, TEVAR, OMT and their combination, and are presented with treatment options, including information on not treating the disease and the necessity and importance of each treatment for each individual patient. Families of patients are also entitled to a full explanation.

3.8. Technical Aspects of Initial OAR

We selected the tear-oriented surgery to minimize the mortality and morbidity rate. By minimizing risks of the initial OAR and performing subsequent TEVAR only in patients with residual false lumen expansion, we are able to rationally avoid overtreatment in the initial OAR (

Figure 2). As shown in the report [

3], mortality rate of initial OAR for acute type A aortic dissection was 8.3% (15–18% in EACTS/STS guideline) [

33]. Another notable feature is that various considerations are made during the initial OAR to enable TEVAR, which may subsequently be performed.

3.8.1. Preoperative Planning and Preparation

Important check points in CT imaging include the location of the primary entry, identifying arteries capable of reliably supplying blood to the true lumen (mainly right axillary and femoral arteries), and locating the arch branches from a technical perspective. Clinically, it is essential to confirm the presence or absence of cerebral infarction and cardiac tamponade. Patients in a coma are generally considered unsuitable for surgery. Additionally, transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography play a vital role in assessing cardiac contractility, valvular function, and cardiac tamponade. If a coronary artery occlusion is suspected, especially involving the left coronary artery, cardiologists should be consulted to promptly perform percutaneous coronary intervention for restoring coronary blood flow.

If necessary, coronary artery bypass grafting is prepared. Considering future intervention in the distal aorta, the left internal thoracic artery should not be used for avoiding a potential risk of paraplegia, and free grafts such as the great saphenous veins should be used instead. In the initial OAR for type A dissection, we routinely use the frog leg position because there is a possibility of coronary artery bypass grafting, including unforeseen circumstances.

3.8.2. Setting of CPB and SCP

If cardiac tamponade is present, it is necessary to decide whether to relieve it first or to secure the sites for arterial return. An appropriately sized prosthetic grafts (J-Graft®, Japan lifeline Co., Ltd. Tokyo, Japan) are anastomosed to arteries that reliably supply blood to the true lumen, ensuring at least one for both upper and lower body, and then cannulated. To prevent retrograde dissection, the artery is not cannulated directly. If lower limb ischemia is suspected, blood infusion should be directed to secure the true lumen while also delivering blood to the ischemic side to address lower limb ischemia when CPB is established. A venous drainage is usually established using two-stage cannula via right atrial appendage. The cardiopulmonary bypass system utilized is Stockert S5® (LivaNova Deutschland GmbH, Munich, Germany). Heparinization during CPB is 0.35 mL/kg bolus, and activated clotting time is maintained at >480 sec.

Additionally, because the common femoral arteries can potentially be used as an access site for TEVAR, we attempt to preserve and not expose the area immediately below the inguinal ligament.

For the right SCP, the SP-GRIPFLOW

TM (12Fr, Fuji Systems Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) cannula is inserted via a prosthetic graft anastomosed to the right axillary artery, and the brachiocephalic artery is clamped before the open distal anastomosis to establish the SCP. For the left SCP, 12 Fr SP-GRIPFLOW

TM cannulas are inserted into the left common carotid artery and left subclavian arteries during the open distal anastomosis. Bilateral SCPs were managed using independent roller pumps to maintain a constant flow rate (right: 5 ml/kg/min, left: 6.5 ml/kg/min), aiming to prevent watershed cerebral infarction [

18]. Cerebral blood flow is monitored using regional oxygen saturation with NIRO-200NX (Hamamatsu Photonics K.K., Hamamatsu, Japan) and cannula tip pressure.

3.8.3. Considerations for Clamping the Ascending Aorta

If the false lumen in the ascending aorta is thrombosed, the ascending aorta is not clamped, and the procedure begins with open distal anastomosis. Conversely, if the false lumen is patent, the ascending aorta is clamped, and the procedure begins with proximal anastomosis. If the false lumen is thrombosed and clamped, there is a risk of thrombus dislodgement, potentially migrating through the tear into the left coronary artery. When the proximal anastomosis is prioritized, the stump is created followed by prosthetic graft anastomosis, allowing subsequent myocardial preservation through the graft (J-Graft®), minimizing the need for direct coronary artery cannulation.

3.8.4. Proximal Aortic Anastomosis

It is important to ensure there is acceptable aortic valve function and no residual false lumen at the aortic root following the initial OAR procedure. Injection of adhesive between the intima and adventitia is not performed or is kept to a minimum. The original anastomotic technique that we adopted involves cuffed anastomosis [

22]. Preventing tear formation due to needle holes during stump preparation is of paramount importance. To address this, a specialized felt (Feltina Pro

®, Kono Seisakusho Co., Ltd, Chiba, Japan) has been developed to facilitate a safe stump preparation method. A 1cm-wide aortic stump is created using the aortic wall with the sino-tubular junction at the lower end using a ring of Feltina Pro, and the left and right coronary artery ostia are confirmed to be open. The results of this approach will be reported in the future. This proximal stump formation method can control the aortic valve regurgitation caused by aortic dissection; however, because significant aortic valve regurgitation that existed before disease onset often remains, the replacement of the valve with a prosthetic one is performed without hesitation. If necessary, an aortic root replacement is also performed.

3.8.5. Distal Aortic Anastomosis

The distal anastomosis is performed under hypothermia with ascending and arch replacement performed at 22 °C, ascending replacement at 25 °C, measured by tympanic membrane temperature, alongside low distal perfusion (300–500 ml/min). The extent of replacement is determined by the location of the primary entry tear (tear-oriented surgery). If it is in the ascending aorta, an ascending replacement is performed. When preoperative CT imaging estimates tears that are not visible during surgery, an ascending and partial arch replacement is performed with reconstruction of brachiocephalic artery to prepare for future TEVAR. If a visible tear is identified in the arch, an ascending and total arch replacement is performed.

In addition, we do not use FET at all to prevent overtreatment because it is impossible to identify patients who will develop false lumen expansion during the initial OAR. For arch branch reconstructions, a distance of 4 cm is maintained from the site of the most peripheral side branch to the distal anastomosis site to ensure a landing zone for TEVAR.

Recently, even when performing total arch replacement, the original elephant trunk is no longer used because it may interfere with subsequent TEVAR.

After the distal aortic anastomosis is completed, the arterial return is switched from the common femoral artery to the most distal of the four branches of the prosthetic graft (J-Graft®). The volume of arterial return should be 500 mL/min during air evacuation and connection of the arterial return cannula with the branch. If it is higher than this value, there is a risk of rupture if false lumen perfusion occurs via the distal tears; thus, care must be taken. This graft branch is finally ligated; this side branch is not included in the measurement to ensure a distance of 4 cm from the distal aortic anastomosis. The arch branches are reconstructed with the three more proximally positioned graft branches.

3.8.6. Reconstruction of Arch Branches and Brachiocephalic Flap Technique

Usually, reconstruction of the arch branches is performed after aortic reconstruction is completed and the heart is reperfused; however, reconstruction of the deep left subclavian artery is performed at the same time as open distal aortic anastomosis. A 5-mm wide Feltina® (Kono Seisakusho Co., Ltd, Chiba, Japan), which was developed based on an idea from our department, is used to reinforce the anastomosis in outer fashion.

In partial arch replacement reconstructing only the brachiocephalic artery, the brachiocephalic artery and the left common carotid artery are often in close proximity, requiring ingenuity during reconstruction. In such cases, the subclavian flap technique used in congenital surgery for coarctation of the aorta is adapted [

52]. Reconstruction is performed using the brachiocephalic flap technique and 2-branched prosthetic graft (J-Graft

®). The outcomes of this approach are planned to be reported in the future.

3.8.7. Weaning from CPB and Hemostasis Technique

Once the tympanic temperature has returned to 35 °C, weaning from CPB begins. Air evacuation and venting from the left ventricle is important during weaning from CPB. When weaning from CPB begins, the head-down position should be assumed, and when the amount of arterial return is reduced by half, the bed should be flattened. If the bed is flattened after removal of the CPB, the remaining air may enter the right coronary artery and cause fatal arrhythmia. Once there is no air inside the heart (confirmed by transesophageal echocardiography) and sufficient cardiac function has recovered, the patient is weaned from CPB.

If the cardiac function is good, there is no particular difficulty. If the cardiac function is impaired, we consider Impella® (ABIOMED®, Danvers, MA, USA) support. The standardized hemostasis technique in the department was established in 2011, and the outcomes are currently being submitted for publication in a medical safety journal. The re-exploration rate for bleeding was <1% for the past decade.

3.9. Technical Aspects of TEVAR for Post Type A and B

We aimed to minimize the extent of TEVAR sealing to reduce the invasiveness and complications. For patients with false lumen expansion, TEVAR should be performed in a timely manner to avoid undertreatment, which would result in missing the opportunity to treat patients who need it. According to a previous report [

4], the mortality rate during hospitalization at the onset of acute type B was 3.1% (14.1% in EACTS/STS guideline) [

33]. At the institution, the mortality rate of TEVAR was as follows: 0% for post-type A, 3.7% for acute complicated type B, and 0% for uncomplicated type B during subacute and chronic phases [

3,

4].

Interestingly, the most recent IRAD report showed that implementation rate of TEVAR for type B patients was 37.2% over the past 5 years (September 2017–August 2022) [

53]. In this study [

4], which clearly defined the indications for TEVAR based on complicated type B cases and progressive false lumen expansion (>5 mm/6 months), the corresponding rate was 40%. Although certain variations in TEVAR indications across IRAD participating institutions are to be expected, this finding strongly suggests that the proportion of type B patients genuinely requiring TEVAR may align at approximately 40%.

3.9.1. Preoperative Planning

Identifying patients with complicated type B is relatively straightforward, as most present with severe symptoms, such as hypotension, aggressive back pain, abdominal or lower limb pain. However, accurately identifying patients with significant false lumen expansion among uncomplicated post type A and type B cases remain challenging. The need for TEVAR varies depending on the morphological characteristics of type B, and the findings on this topic are planned to be reported in the future.

It is essential to identify the site and direction where false lumen expansion is most evident, as this can vary between patients (

Figure 3). In addition to appropriate size (identical to longitudinal diameter of true lumen, 100% oversizing rate to native aorta) and length, the important thing when planning TEVAR is to place the proximal end in a position that does not receive blood flow from the outside of the graft that is one of the reasons for RTAD, and the distal end should not be placed in a curved region that might cause dSINE. TEVAR planning is conducted using OsiriX

® MD (Pixmeo SARL, Geneva, Switzerland).

3.9.2. Details of TEVAR Timing

In the case of complicated type B aortic dissection, TEVAR should be performed promptly; however, TEVAR during the acute phase should be avoided as much as possible for uncomplicated post type A and B aortic dissection [

54]. After the initial OAR for DeBakey III retrograde, even if a primary entry tear remains, TEVAR is not performed during the acute phase and is instead performed in the subacute phase or later if false lumen expansion is confirmed. In cases of uncomplicated post type A, we believe that TEVAR should be avoided in the acute phase to promote recovery from minor organ damage caused by open distal anastomosis.

On the other hand, we avoid performing TEVAR too late (>3 years from onset), because at this time the aortic hiatus has often already dilated and the thoracoabdominal replacement is often inevitable. As a general rule, we aim to complete the identification of patients with or without false lumen expansion within 1 year from the onset of acute aortic dissection. Furthermore, ulcer-like projection, initially described in Japan, represents a localized re-expansion of the thrombosed false lumen. In this lesion, even 3 years after onset, the aortic hiatus does not enlarge and expands the false lumen locally; thus, TEVAR is performed if false lumen expansion is confirmed.

3.9.3. Debranching

Debranching is selected from following three bypass options: the right axillary artery-left axillary artery bypass, the left common carotid artery-left subclavian artery bypass, and the right axillary artery-left common carotid artery-right axillary artery bypass. The first two options are for Zone 2 landing, and the third option is for Zone 1 landing.

In cases of complicated type B, due to emergency, the tear may be closed using TEVAR before debranching; however, in most cases, debranching using 7 or 8 mm GORE

® PROPATEN

® (W.L. Gore & Associates, Inc., Flagstaff, AZ, USA) and CV-6 (needle-to-thread ratio 1:1, W.L. Gore & Associates, Inc., Flagstaff, AZ, USA) is performed first if necessary under heparinization (0.15 mL/kg bolus; maintaining activated clotting time at >250 sec), followed by TEVAR. Although maintaining blood flow in the left common carotid artery is of clear importance, ensuring sufficient blood flow in the left subclavian artery is equally critical. This is necessary to prevent paraplegia by sustaining collateral circulation from the left internal thoracic artery, as well as to prevent thrombus formation by maintaining antegrade blood flow to the left vertebral artery [

55,

56,

57]. To achieve this, the graft anastomosis to the axillary artery must be performed vertically. In addition, after debranching prior to TEVAR, heparin is administered to prevent occlusion of graft due to flow competition towards the antegrade flow of debranched vessels.

When anastomosis is performed between the left common carotid artery and the prosthetic graft, it is necessary to clamp the left common carotid artery. While monitoring regional oxygen saturation, a clamp test for the left common carotid artery is performed. If there is no sudden drop in left regional oxygen saturation, the anastomosis is continued. However, if left regional oxygen saturation immediately drops, the clamp is released, and blood flow is resumed. Next, a 12 Fr SP-GRIPFLOWTM cannula is connected to the branch for the left axillary artery that has already been anastomosed to the right axillary artery, and the anastomosis is performed under distal perfusion of the left common carotid artery. The frequency of need for distal perfusion into the left common carotid artery is 7% in our series.

In post type A, a landing zone of approximately 4 cm is created in the prosthetic graft just before the distal anastomosis; thus, the frequency of debranching during TEVAR is low.

Furthermore, to maintain focus during procedures, operators perform this step without radiation-protective equipment. For precise surgery, tools such as the Castroviejo needle holder and 2.8-mm puncher for coronary anastomosis are utilized. Following the completion of debranching, the TEVAR operator and assistants wear radiation-protective equipment; additionally, the operator wears lower leg shielding [

58].

3.9.4. Access Site

The femoral and iliac arteries in patients with this disease are fragile, making it essential to strictly avoid inserting devices that are too large. If the external iliac artery is small, the common iliac artery is exposed via retroperitoneal approach. In such a case, SurgiSleeveTM (size S or M, Medtronic plc, Galway, Ireland) is used as a wound retractor that has radiolucency.

3.9.5. Guide Wires and Digital Subtraction Angiography System

Wire handling is performed with great care. After switching from Angled Radifocus® Guide Wire M (TERUMO CORPORATION, Tokyo, Japan) to Lunderquist® Extra-Stiff Wire Guide (Cook Medical Inc., Bloomington, IN, USA), violent methods such as pushing the wire into the greater curvature of the arch, which may cause unexpected vascular or left ventricular injury and RTAD are strictly avoided. Digital subtraction angiography system (DSA, ARTIS icono biplane angiography system, SIEMENS, Erlangen Germany) is employed in the hybrid operating room.

Furthermore, to prevent deviation or dislodgement during delivery, relatively soft wires, which pose safety risks, are avoided. Instead, the Lunderquist® Extra-Stiff Wire Guide is routinely used for TEVAR in aortic dissection cases to ensure patient safety.

3.9.6. Searching for the True Lumen Using Intravascular Ultrasound (IVUS)

The optimal method for exploring the true lumen involves using the Angled Radifocus

® GuideWire M in combination with IVUS (Vision PV .035, IntraSight Mobile, Royal Philips, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) [

59]. Even a short length of the guidewire passing through the false lumen can lead to a major disastrous accident; thus, all members of the surgical field carefully examine the IVUS images to make sure that the guidewire is in the true lumen along its entire length in patient’s body.

3.9.7. Delivery and Deployment

GORE

® CTAG is a revolutionary device that reduces blood flow resistance during deployment [

47]. Typically, when the device is folded, it offers little resistance to blood flow, however as it begins to unfold, the device usually creates greater resistance to blood flow and is washed away. We fully understand the fluid mechanics and are careful in deploying the device in the correct position. In the arch, blood flow runs horizontally, and the delivery system has a vertical portion; therefore, unless the resistance of the device is reduced during deployment or the delivery system has high rigidity, the device tends to flow to the periphery.

As a general rule, the first piece inserted should close the target tear [

4]. If the target tear remains open and the first piece is placed distally, the false lumen at that site will be temporarily compressed, increasing blood flow resistance. This raises the risk of the dissection progressing proximally, known to lead to RTAD. In addition, if the true lumen is narrowed to the same size as the device during delivery, there is a risk of the true lumen being closed, causing a sudden increase in the upper body blood pressure, which can lead to RTAD. In such cases, prompt retraction of the device is performed, and delivery is carried out slowly at a rate that allows the anesthesiologist to manage any increase respond in blood pressure effectively. Devices like the GORE

® CTAG are desirable as they allow adjustment of the proximal end’s angle during the initial deployment; adjusting the angle afterward could increase the risk of RTAD and should be avoided. Furthermore, it is critical to ensure the device is not exposed to external blood flow after placement (avoiding the so-called bird beak), as this could lead to new tears on the opposite side of the area exposed to external blood flow. Additionally, transient balloon occlusion of the left subclavian artery during the delivery and deployment of TEVAR is performed to prevent embolism in patients with shaggy aorta [

60].

3.9.8. Checking Access Route after Procedure

After completing the main procedures, angiography is performed to assess for damage to RTAD at the ascending aorta and access route. It also examines the state of backward flow in the false lumen through the aortic hiatus, and the perfusion status of the abdominal branches and lower extremities.

Due to the potential risk of injury to the iliac arteries, the sheath is kept within the wire rather than being fully removed during its withdrawal from the common femoral artery. In the event of a sudden drop in blood pressure, the sheath is promptly reinserted into the abdominal aorta. This action seals the damaged area of the iliac arteries, providing time to prepare the necessary equipment for repair.

3.10. Predictable and Unpredictable Additional Interventions

As indicated in the report [

3], additional arch replacement was performed following initial OAR for type A aortic dissection in patients presented with tears in the arch branches, such as the brachiocephalic and left subclavian arteries. Recently, if there is a tear in the arch branch by CT imaging has enabled the identification of tears in the arch branches, leading to partial or total arch replacement being performed to prevent blood flow into the false lumen of the aorta through the branches.

For cases involving multiple tears in the thoracic descending aorta [

4], the initial TEVAR focuses on closing the largest tear, resulting in a minimal sealing area to prevent paraplegia. Additional TEVAR is undertaken only if false lumen expansion persists due to another tear, which is considered a predictable intervention. Conversely, after TEVAR performed in the acute phase, the extremely narrow true lumen may be drastically normalized, leading to stent graft migration. This necessitates additional OAR or TEVAR several months later due to complications such as RTAD and dSINE. Such interventions are unpredictable. Following TEVAR, particularly for complicated type B dissections during the acute phase, close follow-up and timely intervention remain essential [

54].

3.11. Finally, Almost All Patients are Managed with OMT-Alone

In the Oda strategy, the three treatment modalities, OAR, TEVAR, and OMT, are rationally combined, and only patients who need them are given the necessary treatment in a timely manner, without overtreatment or undertreatment. In almost all cases, thoraco-abdominal aortic replacement is unnecessary, and almost all patients are finally managed with OMT-alone (

Figure 2) [

3,

4]. Careful annual CT follow-up is also continued.

4. Future Perspectives in Aortic Dissection Management

4.1. OAR in the Future

OAR for acute type A aortic dissection is performed under strict time constraints, making it impractical to use prosthetic grafts that require prior preparation, such as tissue-engineered vascular grafts [

61]. It was originally developed for small-caliber vessels and lacks the durability required for high-pressure regions such as the thoracic aorta. Among the three treatment options, namely OAR, TEVAR, and OMT, OAR remains the most technically mature. Further innovation is expected.

In the future, population declines in many developed nations may pose challenges in maintaining a stable blood supply for transfusions [

62]. The Oda strategy, which focuses on minimal tear-oriented surgery and avoids extensive aortic replacement, is expected to gain increased relevance in resource-constrained environments.

4.2. Next-Generation TEVAR: Opportunities and Limitations

Currently, the GORE CTAG remains the most suitable TEVAR device for this condition. Although further refinements such as reducing the device profile to facilitate accessibility, could be beneficial. Branched devices, such as Thoracic Branch Endoprosthesis (TBE

®, W.L. Gore & Associates, Inc., Flagstaff, AZ, USA), are emerging as alternatives that may reduce the need for surgical debranching [

63]. However, device enhancements often come with trade-offs. The TBE

® lacks the proximal angulation control mechanism found in CTAG. Additionally, all unsheathe-type devices currently face the critical drawback of completely occluding the aortic lumen upon deployment, which remains a pressing issue that requires immediate attention.

In the Oda strategy, TEVAR is immediately performed without OAR for ruptured DeBakey III retrograde cases, despite their classification as type A. This exception is due to the extreme urgency of such cases and OAR is often not possible in time. However, TEVAR for type A aortic dissections poses significant technical and physiological challenges. A particularly critical issue is the considerable variation in the diameter of the ascending aorta between the systolic and diastolic phases. Therefore, any future TEVAR device designed for this region must accommodate these dynamic changes in vessel size. Although global efforts to develop TEVAR for type A aortic dissections are ongoing, clinical application remains a distant prospect [

64,

65].

4.3. Emerging Therapies in OMT: Pharmacologic and Cellular Innovations

The foundation of drug therapy in OMT involves antihypertensive medication; however, new agents, such as zilebesiran, which act via novel mechanisms, may emerge in the future [

66]. Since the fragility of the aortic wall, particularly the intima, is considered a key factor in primary entry formation, efforts are underway to develop pharmacological therapies aimed at reinforcing the structural integrity of the aortic wall. For example, the transforming growth factor-beta signaling pathway and matrix metalloproteinase activity have been identified as promising therapeutic targets [

67,

68]. To prevent rupture, new approaches that specifically act on the adventitia to enhance tissue strength, such as the use of multilineage-differentiating stress enduring cells [

69], and nanocarrier-based delivery systems [

70], are being explored. The efficacy of these treatments has been reported in experimental animal models.

5. Conclusions

Ultimately, the future of aortic dissection treatment depends on scientifically sound and ethically justified strategies. The Oda strategy, rooted in clinical evidence and technical refinement, highlights the benefits of selective intervention, particularly in reducing the need for thoracoabdominal replacement. While emphasizing tear-oriented open aortic repair and false lumen-guided thoracic endovascular aortic repair, broader validation is required. The Oda strategy established the foundation for a unified, patient-centered standard of care.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Oda K.; methodology, Katahira S.; validation, Katahira S., and Takahashi M.; investigation, Taketomi R., Akanuma R., and Hasegawa T.; writing—original draft preparation, Oda K.; writing—review and editing, Katahira S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

This review is dedicated, as the first author, to the memory of my late father and mother. Gratitude is also extended to Editage (

www.editage.com) for the assistance provided in English language editing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CPB |

Cardiopulmonary bypass |

| CT |

Computed tomography |

| CTAG |

Conformable thoracic aortic graft |

| dSINE |

Distal stent graft-induced new entry |

| FET |

Frozen elephant trunk |

| FLE |

False lumen expansion |

| IRAD |

International Registry of Aortic Dissection |

| IVUS |

Intravascular ultrasound |

| OAR |

Open aortic repair |

| OMT |

Optimal medical treatment |

| |

|

| RCT |

Randomized controlled trial |

| RTAD |

Retrograde type A aortic dissection |

| SCP |

Selective cerebral perfusion |

| TBE |

Thoracic Branch Endoprosthesis |

| TEVAR |

Thoracic endovascular aortic repair |

References

- Daily, P.O.; Trueblood, H.W.; Stinson, E.B.; Wuerflein, R.D.; Shumway, N.E. Management of acute aortic dissections. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1970, 10(3), 237–247. [CrossRef]

- Dake, M.D.; Miller, D.C.; Semba, C.P.; Mitchell, R.S.; Walker, P.J.; Liddell, R.P. Transluminal placement of endovascular stent-grafts for the treatment of descending thoracic aortic aneurysms. N. Engl. J. Med. 1994, 331(26), 1729–1734. [CrossRef]

- Oda, K.; Kanda, K.; Takahashi, M.; Terao, N.; Akanuma, R.; Hasegawa, T.; Kawatsu, S. Closing of a patent tear above the aortic hiatus and type A aortic dissection outcomes. Ann. Thorac. Surg. Short Rep. 2023, 1(3), 375–378. [CrossRef]

- Oda, K.; Takahashi, M.; Taketomi, R.; Akanuma, R.; Hasegawa, T.; Kawatsu, S. Expert management of type B aortic dissection from onset with thoracic endovascular aortic repair. Ann. Thorac. Surg. Short Rep. 2025, 3(1), 6–10. [CrossRef]

- Committee on Quality of Health Care in America; Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm. A new health system for the 21st. Century; National Academies Press: Washington, USA, 2001. [CrossRef]

- Hagan, P.G.; Nienaber, C.A.; Isselbacher, E.M.; Bruckman, D.; Karavite, D.J.; Russman, P.L.; Evangelista, A.; Fattori, R.; Suzuki, T.; Oh, J.K.; Moore, A.G.; Malouf, J.F.; Pape, L.A.; Gaca, C.; Sechtem, U.; Lenferink, S.; Deutsch, H.J.; Diedrichs, H.; Marcos y Robles, J.; Llovet, A.; Gilon, D.; Das, S.K.; Armstrong, W.F.; Deeb, G.M.; Eagle, K.A. The international registry of acute aortic dissection (IRAD): new insights into an old disease. JAMA 2000, 283(7), 897–903. [CrossRef]

- Hirst, A.E.; Johns, V.J.; Kime, S.W. Dissecting aneurysm of the aorta: a review of 505 cases. Medicine 1958, 37(3), 217–279. [CrossRef]

- De Bakey, M.E.; Cooley, D.A.; Creech, O. Surgical considerations of dissecting aneurysm of the aorta. Ann. Surg. 1955, 142(4), 586–610. [CrossRef]

- DeBakey, M.E.; Henly, W.S.; Cooley, D.A.; Morris, G.C.; Crawford, E.S.; Beall, A.C. Surgical management of dissecting aneu-rysms of the aorta. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 1965, 49, 130–149. [CrossRef]

- Francica, A.; Tonelli, F.; Rossetti, C.; Tropea, I.; Luciani, G.B.; Faggian, G.; Dobson, G.P.; Onorati, F. Cardioplegia between Evolution and Revolusion: From Depolarized to Polarized Cardiac Arrest in Adult Cardiac Surgery. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10(19), 4485. [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, A.; Aboughdir, M.; Mahbub, S.; Ahmed, A.; Harky, A. Myocardial protection in cardiac surgery: how limited are the options? a comprehensive literature review. Perfusion 2021, 36(4), 338–351. [CrossRef]

- Mainwaring, E.; Patel, R.; Desai, C.; Acharya, R.; Raveshia, D.; Shah, S.; Panesar, H.; Patel, N.; Singh, R. Five historical innovations that have shaped modern cardiothoracic surgery. J. Perioper. Pract. 2024, 34(9), 282–292. [CrossRef]

- Borst, H.G.; Walterbusch, G.; Schaps, D. Extensive aortic replacement using ‘Elephant Trunk’ prosthesis. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 1983, 31(1), 37–40. [CrossRef]

- Faby, S.; Flohr, T. Multidetector-row CT basis, technological evolution, and current technology. In Body MDCT in Small Animals; Bertolini, G., Ed.; Springer: Berlin, 2017; pp. 3–33.

- Lowe, A.S.; Kay, C.L. Recent developments in CT: a review of the clinical applications and advantages of multidetector computed tomography. Imaging 2006, 18(2), 62–67. [CrossRef]

- Fraser, A.G.; Monaghan, M.J.; van der Steen, A.F.W.; Sutherland, G.R. A concise history of echocardiography: timeline, pioneers, and landmark publications. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2022, 23(9), 1130–1143. [CrossRef]

- Kazui, T.; Inoue, N.; Yamada, O.; Komatsu, S. Selective cerebral perfusion during operation for aneurysms of the aortic arch: a reassessment. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1992, 53(1), 109–114. [CrossRef]

- Tabayashi, K.; Ohmi, M.; Togo, T.; Miura, M.; Yokoyama, H.; Akimoto, H.; Murata, S.; Ohsaka, K.; Mohri, H. Aortic arch aneurysm repair using selective cerebral perfusion. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1994, 57(5), 1305–1310. [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; Li, Y.; Ke, Z.; Yang, H.; Lu, C.; Li, Y.; Guo, Y.; Wang, W. History, progress and future challenges of artificial blood vessels: a narrative review. Biomater. Transl. 2022, 3(1), 81–98. [CrossRef]

- Allotey, J.K.; King, A.H.; Kumins, N.H.; Wong, V.L.; Harth, K.C.; Cho, J.S.; Kashyap, V.S. Systematic review of hemostatic agents used in vascular surgery. J. Vasc. Surg. 2021, 73(6), 2189–2197. [CrossRef]

- Daud, A.; Kaur, B.; McClure, G.R.; Belley-Cote, E.P.; Harlock, J.; Crowther, M.; Whitlock, R.P. Fibrin and thrombin sealants in vascular and cardiac surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2020, 60(3), 469–478. [CrossRef]

- Oda, K.; Akimoto, H.; Hata, M.; Akasaka, J.; Yamaya, K.; Iguchi, A.; Tabayashi, K. Use of cuffed anastomosis in total aortic arch replacement. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2003, 76(3), 952–953. [CrossRef]

- Coselli, J.S.; LeMaire, S.A.; Köksoy, C. Thoracic aortic anastomoses. Oper. Tech. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2000, 5(4), 259–276. [CrossRef]

- Stanworth, S.J.; Shah, A. How I use platelet transfusions. Blood 2022, 140(18), 1925–1936. [CrossRef]

- Rylski, B.; Beyersdorf, F.; Kari, F.A.; Schlosser, J.; Blanke, P.; Siepe, M. Acute type A aortic dissection extending beyond ascending aorta: Limited or extensive distal repair. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2014, 148(3), 949–54; discussion 954. [CrossRef]

- Hage, F.; Atarere, J.; Anteby, R.; Hage, A.; Malik, M.I.; Boodhwani, M.; Ouzounian, M.; Chu, M.W.A. Total arch vs hemiarch repair in acute type A aortic dissection: systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative studies. CJC Open 2024, 6(9), 1075–1086. [CrossRef]

- Parodi, J.C.; Palmaz, J.C.; Barone, H.D. Transfemoral intraluminal graft implantation for abdominal aortic aneurysms. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 1991, 5(6), 491–499. [CrossRef]

- Kato, M.; Ohnishi, K.; Kaneko, M.; Ueda, T.; Kishi, D.; Mizushima, T.; Matsuda, H. New graft-implanting method for thoracic aortic aneurysm or dissection with a stented graft. Circulation 1996, 94(9) (Suppl.), II188–II193.

- Karck, M.; Chavan, A.; Khaladj, N.; Friedrich, H.; Hagl, C.; Haverich, A. The frozen elephant trunk technique for the treatment of extensive thoracic aortic aneurysms: operative results and follow-up. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2005, 28(2), 286–90; discussion 290. [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Qi, R.; Zhu, J.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, J. Total arch replacement combined with stented elephant trunk implantation: a new ‘standard’ therapy for type a dissection involving repair of the aortic arch? Circulation 2011, 123(9), 971–978. [CrossRef]

- Inoue, Y.; Matsuda, H.; Omura, A.; Seike, Y.; Uehara, K.; Sasaki, H.; Kobayashi, J. Comparative study of the frozen elephant trunk and classical elephant trunk techniques to supplement total arch replacement for acute type A aortic dissection†. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2019, 56(3), 579–586. [CrossRef]

- Dake, M.D.; Kato, N.; Mitchell, R.S.; Semba, C.P.; Razavi, M.K.; Shimono, T.; Hirano, T.; Takeda, K.; Yada, I.; Miller, D.C. Endovascular stent-graft placement for the treatment of acute aortic dissection. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 340(20), 1546–1552. [CrossRef]

- Authors/Task Force Members; Czerny, M.; Grabenwöger, M.; Berger, T.; Aboyans, V.; Della Corte, A.; Chen, E.P.; Desai, N.D.; Dumfarth, J.; Elefteriades, J.A.; Etz, C.D.; Kim, K.M.; Kreibich, M.; Lescan, M.; Di Marco, L.; Martens, A.; Mestres, C.A.; Milojevic, M.; Nienaber, C.A.; Piffaretti, G.; Preventza, O.; Quintana, E.; Rylski, B.; Schlett, C.L.; Schoenhoff, F.; Trimarchi, S.; Tsagakis, K.; EACTS/STS Scientific Document Group; Siepe, M.; Estrera, A.L.; Bavaria, J.E.; Pacini, D.; Okita, Y.; Evangelista, A.; Harrington, K.B.; Kachroo, P.; Hughes, G.C. EACTS/STS Guidelines for diagnosing and treating acute and chronic syndromes of the aortic organ. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2024, 118(1), 5–115. [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, M.; Bachet, J.; Bavaria, J.; Carrel, T.P.; De Paulis, R.D.; Di Bartolomeo, R.; Etz, C.D.; Grabenwöger, M.; Grimm, M.; Haverich, A.; Jakob, H.; Martens, A.; Mestres, C.A.; Pacini, D.; Resch, T.; Schepens, M.; Urbanski, P.P.; Czerny, M. Current status and recommendations for use of the frozen elephant trunk technique: a position paper by the Vascular Domain of EACTS. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2015, 47(5), 759–769. [CrossRef]

- Preventza, O.; Liao, J.L.; Olive, J.K.; Simpson, K.; Critsinelis, A.C.; Price, M.D.; Galati, M.; Cornwell, L.D.; Orozco-Sevilla, V.; Omer, S.; Jimenez, E.; LeMaire, S.A.; Coselli, J.S. Neurologic complications after the frozen elephant trunk procedure: A meta-analysis of more than 3000 patients. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2020, 160(1), 20–33.e4. [CrossRef]

- Hiraoka, T.; Furukawa, T.; Imai, K.; Takahashi, S. Distal stent graft-induced new entry after frozen elephant trunk procedure for aortic dissection. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2023, 97, 340–350. [CrossRef]

- Kreibich, M.; Bünte, D.; Berger, T.; Vötsch, A.; Rylski, B.; Krombholz-Reindl, P.; Chen, Z.; Morlock, J.; Beyersdorf, F.; Winkler, A.; Rolauffs, B.; Siepe, M.; Gottardi, R.; Czerny, M. Distal stent graft-induced new entries after the frozen elephant trunk procedure. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2020, 110(4), 1271–1279. [CrossRef]

- Okita, Y. Kinking of frozen elephant trunk: reality versus myth–a case report and literature reported. Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 2022, 12(4), 545–551. [CrossRef]

- Kayali, F.; Qutaishat, S.; Jubouri, M.; Chikhal, R.; Tan, S.Z.C.P.; Bashir, M. Kinking of frozen elephant trunk hybrid prostheses: incidence, mechanism, and management. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 912071. [CrossRef]

- Takagaki, M.; Midorikawa, H.; Yamaguchi, H.; Nakamura, H.; Kadowaki, T.; Ueno, Y.; Uchida, T.; Aoki, T. Rapidly progressed distal arch aneurysm with distal open stent graft-induced new entry caused by ‘spring-back’ force. Ann. Vasc. Dis. 2020, 13(3), 343–346. [CrossRef]

- Geirsson, A.; Bavaria, J.E.; Swarr, D.; Keane, M.G.; Woo, Y.J.; Szeto, W.Y.; Pochettino A. Fate of the residual and proximal aorta after acute type A dissection repair using a contemporary surgical reconstruction algorithm. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2007, 84(6), 1955–1964; discussion 1955. [CrossRef]

- Halstead, J.C.; Meier, M.; Etz, C.; Spielvogel, D.; Bodian, C.; Wurm, M.; Shahani, R.; Griepp, R.B. The fate of the distal aorta after repair of acute type A aortic dissection. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2007, 133(1),127–135. [CrossRef]

- Nienaber, C.A.; Kische, S.; Rousseau, H.; Eggebrecht, H.; Rehders, T.C.; Kundt, G.; Glass, A.; Scheinert, D.; Czerny, M.; Kleinfeldt, T.; Zipfel, B.; Labrousse, L.; Fattori, R.; Ince, H.; INSTEAD-XL trial. Endovascular repair of type B aortic dissection: long-term results of the randomized investigation of stent grafts in aortic dissection trial. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2013, 6(4), 407–416. [CrossRef]

- VIRTUE Registry Investigators. Mid-term outcomes and aortic remodelling after thoracic endovascular repair for acute, subacute, and chronic aortic dissection: the VIRTUE Registry. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2014, 48(4), 363–371. [CrossRef]

- Naito, N.; Takagi, H. Optimal Timing of Pre-emptive Thoracic Endovascular Aortic Repair in Uncomplicated Type B Aortic Dissection: a Network Meta-Analysis. J. Endovasc. Ther. 2024, 15266028241245282. [CrossRef]

- Xiang, D.; Wu, F.; Chen, L.; Liang, H.; Xiong, B.; Liang, B.; Yang, F.; Zheng, C. Timing of endovascular repair impacts long-term outcomes of uncomplicated acute type B aortic dissection. J. Vasc. Surg. 2022, 75(3), 851–860.e3. [CrossRef]

- Mariani, C.; van der Weijde, E.; Smith, T.; Smeenk, H.G.; Vos, J.A.; Heijmen, R.H. The Gore TAG conformable thoracic stent graft with the new ACTIVE CONTROL deployment system. J. Vasc. Surg. 2019, 70(2), 432–437. [CrossRef]

- Tjaden, B.L.; Sandhu, H.; Miller, C.; Gable, D.; Trimarchi, S.; Weaver F.; Azizzadeh, A. Outcomes from the Gore Global Registry for Endovascular Aortic Treatment in patients undergoing thoracic endovascular aortic repair for type B dissection. J. Vasc. Surg. 2018, 68(5), 1314–1323. [CrossRef]

- van Bogerijen, G.H.W.; Tolenaar, J.L.; Rampoldi, V.; Moll, F.L.; van Herwaarden, J.A.; Jonker, F.H.W.; Eagle, K.A.; Trimarchi, S. Predictors of aortic growth in uncomplicated type B aortic dissection. J. Vasc. Surg. 2014, 59(4), 1134–1143. [CrossRef]

- Oda, K.; Takahashi, M.; Itagaki, K.; Akanuma, R.; Hasegawa, T.; Kawatsu, S. Eight key structures of cardiovascular surgical teams required for patient safety and work style reforming. J. Med. Saf. 2024, 19, 5–11.

- Mori, K.; Wada, T.; Shuto, T.; Kodera, A.; Kawashima; T.; Anai, H.; Miyamoto, S. Postoperative paraplegia after transapical transcatheter aortic valve implantation. J Cardiol Cases 2019, 20(1), 23–26. [CrossRef]

- Barreiro, C.J.; Ellison, T.A.; Williams, J.A.; Durr, M.L.; Cameron, D.E.; Vricella, L.A. Subclavian flap aortoplasty: still a safe, reproducible, and effective treatment for infant coarctation. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2007, 31(4), 649–653. [CrossRef]

- Trimarchi, S.; Gleason, T.G.; Brinster, D.R.; Bismuth, J.; Bossone, E.; Sundt, T.M.; Montgomery, D.G.; Pai, C.W.; Bissacco, D.; de Beaufort, H.W.L.; Bavaria, J.E.; Mussa, F.; Bekeredjian, R.; Schermerhorn, M.; Pacini, D.; Myrmel, T.; Ouzounian, M.; Korach, A.; Chen, E.P.; Coselli, J.S.; Eagle, K.A.; Patel, H.J. Editor’s Choice – trends in management and outcomes of type B aortic dissection: a report from the international registry of aortic dissection. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2023, 66(6), 775–782. [CrossRef]

- Torrent, D.J.; McFarland, G.E.; Wang, G.; Malas, M.; Pearce B.J.; Aucoin, V.; Neal, D.; Spangler, E.L.; Novak, Z.; Scali, S.T.; Beck, A.W. Timing of thoracic endovascular aortic repair for uncomplicated acute type B aortic dissection and the association with complications. J. Vasc. Surg. 2021, 73(3), 826–835. [CrossRef]

- Miranda, M.; Hossne, N.A.; de Vilela, A.T.; Buffolo, E. Paraplegia after off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2014, 97(1), 326–327. [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, R.J.; Ahanchi, S.S.; Powell, O.; Larion, S.; Brandt, C.; Soult, M.C.; Panneton, J.M. Left subclavian artery revascularization in zone 2 thoracic endovascular aortic repair is associated with lower stroke risk across all aortic diseases. J. Vasc. Surg. 2017, 65(5), 1270–1279. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Pozzoli, A.; von Segesser, L.K.; Berdajs, D.; Tozzi, P.; Ferrari, E. Management of left subclavian artery in type B aortic dissection treated with thoracic endovascular aorta repair. J. Vasc. Surg. 2023, 77(5), 1553–1561.e2. [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed, T.; Patel, A.S.; Cho, J.S.; Kelly, J.A.; Ludwinski, F.E.; Saha, P.; Lyons, O.T.; Smith, A.; Modarai, B.; Guy’s and St Thomas’ Cardiovascular Research Collaborative. Radiation-induced DNA damage in operators performing endovascular aortic repair. Circulation 2017, 136(25), 2406–2416. [CrossRef]

- Ciccone, M.M.; Dentamaro, I.; Masi, F.; Carbonara, S.; Ricci, G. Advances in the diagnosis of acute aortic syndromes: role of imaging techniques. Vasc. Med. 2016, 21(3), 239–250. [CrossRef]

- Seike, Y.; Matsuda, H.; Inoue, Y.; Omura, A.; Uehara, K.; Fukuda, T.; Kobayashi, J. Balloon protection of the left subclavian artery in debranching thoracic endovascular aortic repair. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2019, 157(4), 1336–1345.e1. [CrossRef]

- Durán-Rey, D.; Crisóstomo, V.; Sánchez-Margallo, J.A.; Sánchez-Margallo, F.M. Systematic Review of Tissue-Engineered Vascular Grafts. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, Article 771400. [CrossRef]

- Greinacher, A.; Fendrich, K.; Hoffmann, W. Demographic changes: the impact for safe blood supply. Transfus. Med. Hemother. 2010, 37(3), 141–148. [CrossRef]

- Desai, N.D.; Wang, G.J.; Brinkman, W.; Coselli, J.; Taylor, B.; Patel, H.; Dake, M.; Fleischman, F.; Panneton, J.; Matsumura, J.; Sweet, M.; DeMartino, R.; Leshnower, B.; Sanchez, L.; Bavaria, J.E. Outcomes of a novel single-branched aortic stent graft for treatment of type B aortic dissection. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2025, 119(4), 826–834. [CrossRef]

- Mylonas, K.S.; Zoupas, I.; Tasoudis, P.T.; Vitkos, E.; Stavridis, G.T.; Avgerinos, D.V. Endovascular treatment of type A aortic dissection: a systematic review and meta-analysis using reconstructed time-to-event data. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12(22), 7051. [CrossRef]

- De Freitas, S.D.; Rossi, M.J.; Abramowitz, S.D.; Fatima, J.; Kiguchi, M.M.; Vallabhaneni, R.; Walsh, S.R.; Woo, E.Y. Systematic review and meta-analysis of endovascular interventions for Stanford type A aortic dissection. J. Vasc. Surg. 2021, 74(5), 1721–1731.e4. [CrossRef]

- Desai, A.S.; Webb, D.J.; Taubel, J.; Casey, S.; Cheng, Y.; Robbie, G.J.; Foster, D.; Huang, S.A.; Rhyee, S.; Sweetser, M.T.; Bakris, G.L. Zilebesiran, an RNA Interference therapeutic agent for hypertension. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389(3), 228–238. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Sun, M.; Wu, N.; Liu, B.; Liu, Q.; Fan, X. TGF-β/Smads signaling pathway, Hippo-YAP/TAZ signaling pathway, and VEGF: their mechanisms and roles in vascular remodeling related diseases. Immun. Inflamm. Dis. 2023, 11(11), e1060. [CrossRef]

- Kurihara, T.; Shimizu-Hirota, R.; Shimoda, M.; Adachi, T.; Shimizu, H.; Weiss, S.J.; Itoh, H.; Hori, S.; Aikawa, N.; Okada, Y. Neutrophil-derived matrix metalloproteinase 9 triggers acute aortic dissection. Circulation 2012, 126(25), 3070–3080. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, M.; Kushida, Y.; Kuroda, Y.; Wakao, S.; Horibata, Y.; Sugimoto, H.; Dezawa, M.; Saiki, Y. Structural reconstruction of mouse acute aortic dissection by intravenously administered human Muse cells without immunosuppression. Commun. Med. (Lond) 2024, 4(1), 174. [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, K.; Nie, J.J.; Yu, B.; Li, S.; Cheng, G.; Li, Y.; Du, J.; Xu, F.J. Multifunctional cationic nanosystems for nucleic acid therapy of thoracic aortic dissection. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10(1), 3184. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).