1. Introduction

The human pupil is a highly reactive anatomical structure whose size reflects the dynamic interplay between parasympathetic and sympathetic inputs. Its diameter is modulated by ambient luminance, accommodation, emotional state, cognitive load, and various pharmacological agents acting on the central and autonomic nervous systems. In living individuals, the pupillary light reflex (PLR) is a cornerstone of neuro-ophthalmologic assessment, but pupil size is also altered in the context of systemic and neurological pathologies. Notably, encephalopathies, traumatic brain injury, and infections such as neurosyphilis may interfere with the integrity of the Edinger–Westphal nucleus or its peripheral pathways, leading to persistent miosis, mydriasis, or irregular light responses. [1–5] Trauma and increased intracranial pressure may cause unilateral dilation or fixed pupils, while metabolic encephalopathies and poisoning are known to produce a variety of pupillary abnormalities. [6–10] Among pharmacological agents, opioids such as morphine, heroin, and codeine are well-documented to induce miosis through μ-opioid receptor activation, with rapid onset and dose-dependent effects. Conversely, stimulants (e.g., cocaine, amphetamines), anticholinergics, serotonergic agents, and cannabinoids may cause mydriasis to varying degrees. Pupil diameter has also been used experimentally as a non-invasive marker of central nervous system arousal, decision-making, and fatigue. [11–14] Despite the recognized clinical value of pupillometry, no studies to date have systematically investigated the persistence of drug-induced pupillary changes in the postmortem interval (PMI). The traditional assumption holds that after death, with the cessation of autonomic tone, the iris musculature relaxes and the pupil assumes a passive, mid-dilated position. However, recent forensic research has begun to question this paradigm, pointing to potential residual signs of pharmacological influence—particularly in the early to intermediate postmortem period. [15–22] The aim of this study is to evaluate whether postmortem pupil size, measured through a scale-independent pupil-to-iris ratio (PIR), may serve as a residual morphological marker of pharmacological influence, particularly in cases of opioid and psychoactive drug exposure. This objective is pursued through the implementation of an artificial intelligence-based method capable of analyzing postmortem ocular images, classifying pupillary states, and correlating them with toxicological findings. By doing so, we explore the possibility that the pupil, traditionally considered diagnostically inert after death, may in fact retain measurable traces of antemortem or perimortem neuropharmacological activity.

2. Materials and Methods

This retrospective observational study was conducted on a selected cohort of 30 deceased individuals (n = 60 eyes), examined during forensic autopsies performed between 24 and 36 hours after death. Only cases with intact ocular structures, preserved photographic documentation, and validated toxicological analyses were included. All procedures were performed in accordance with national forensic standards, and no identifying information was retained. High-resolution ocular photographs were acquired under standard morgue lighting conditions during external examination. Only images meeting predefined criteria for focus, anatomical orientation, and visibility of pupillary margins were processed. Eyes with post-traumatic injury, extensive decomposition, or corneal opacification were excluded. The core methodological innovation of this study lies in the use of a multimodal artificial intelligence platform (ChatGPT Plus, OpenAI) for semi-automated extraction of the pupil and iris diameters in pixel units. The Pupil-to-Iris Ratio (PIR) was calculated for each image as a dimensionless value to standardize pupillary measurements regardless of distance or magnification. Each PIR was then classified into three categories:

Miosis: PIR < 0.33;

Mid-range: 0.33 ≤ PIR ≤ 0.50;

Mydriasis: PIR > 0.50.

Toxicological results were used to classify subjects as “positive” or “negative” based on the detection of opioids, cannabinoids, stimulants, benzodiazepines, or other psychoactive compounds. Comparison of PIR values between toxicologically positive and negative individuals was performed.

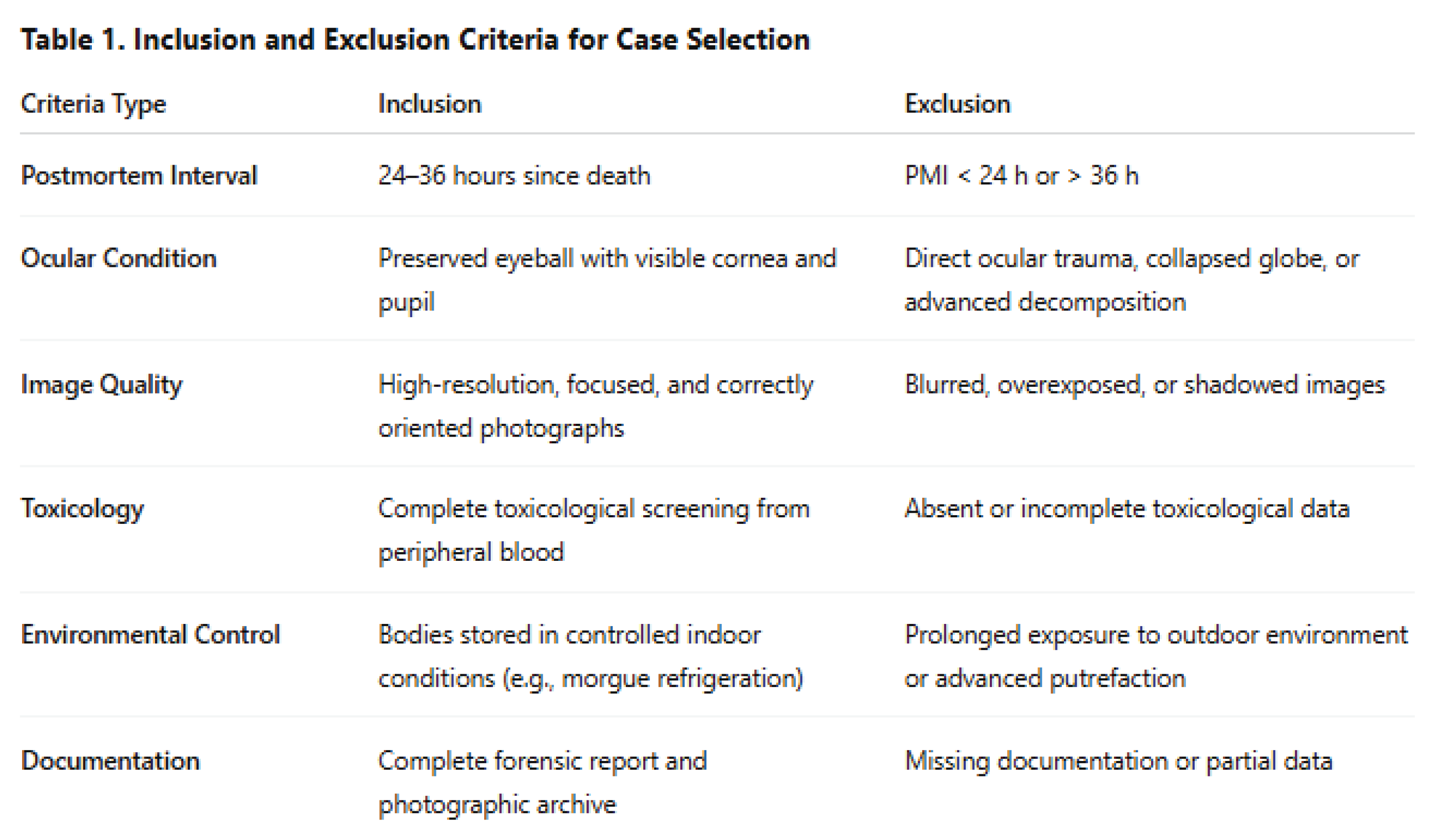

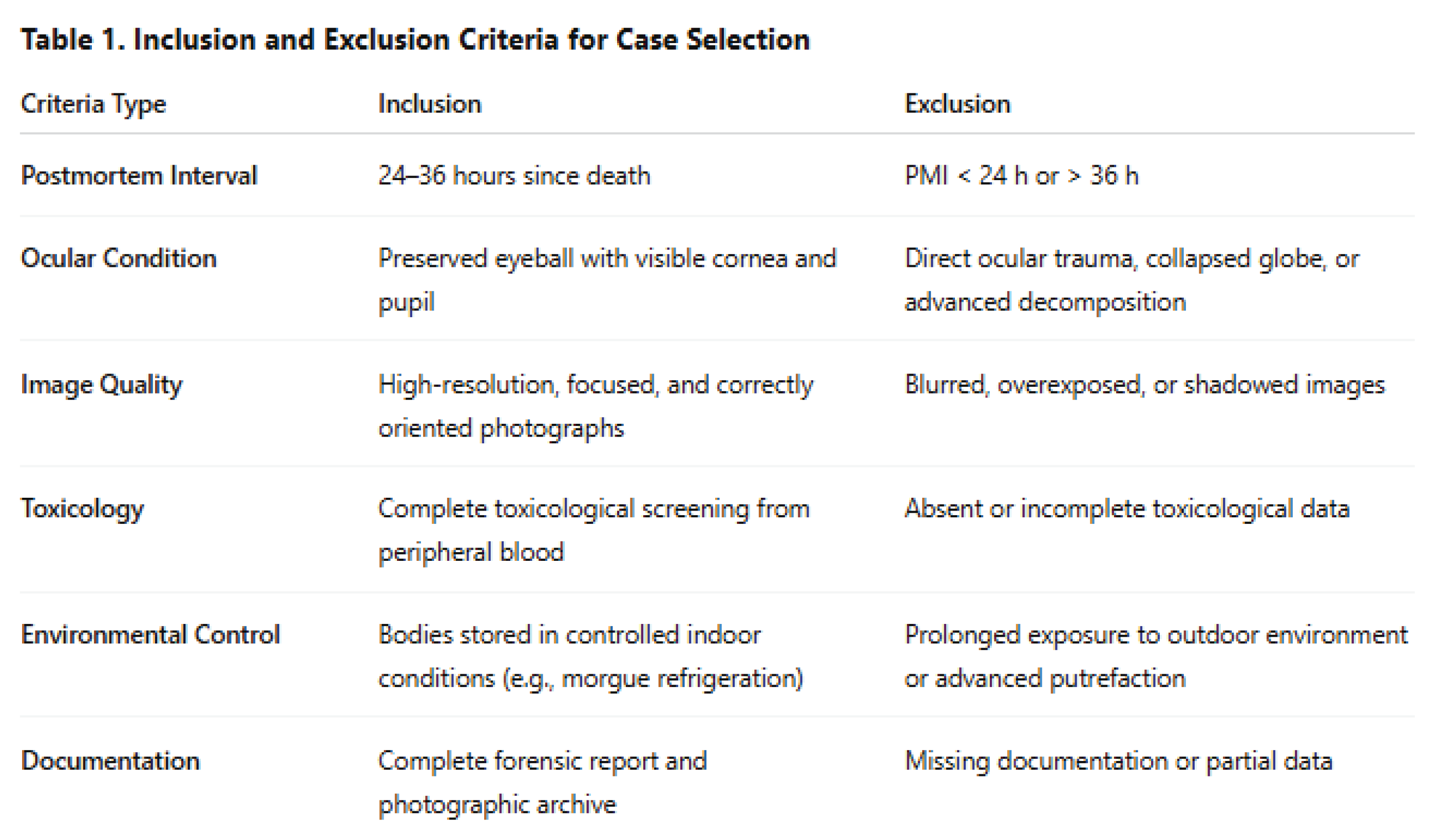

Table 1 summarizes the inclusion and exclusion criteria used for selecting cases in this study. Only individuals with intact ocular anatomy, high-quality imaging, and complete toxicological data were included to ensure consistency and reliability of the pupil-to-iris ratio (PIR) measurements.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize PIR values across the full sample and by toxicological subgroup. Normality was assessed using visual inspection and distribution indices. Depending on data distribution, group comparisons were performed using parametric tests (e.g., Student’s t-test) or non-parametric tests (e.g., Mann–Whitney U test). PIR categories (miosis, mid-range, mydriasis) were analyzed using chi-square tests for independence. Effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were calculated to evaluate the magnitude of observed differences. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 (two-tailed). Analyses were exploratory in nature, without correction for multiple comparisons. Given the proof-of-concept nature of the study, no a priori sample size calculation was performed. Data processing and statistics were executed using standard open-source libraries in a Python-based environment.

3. Results

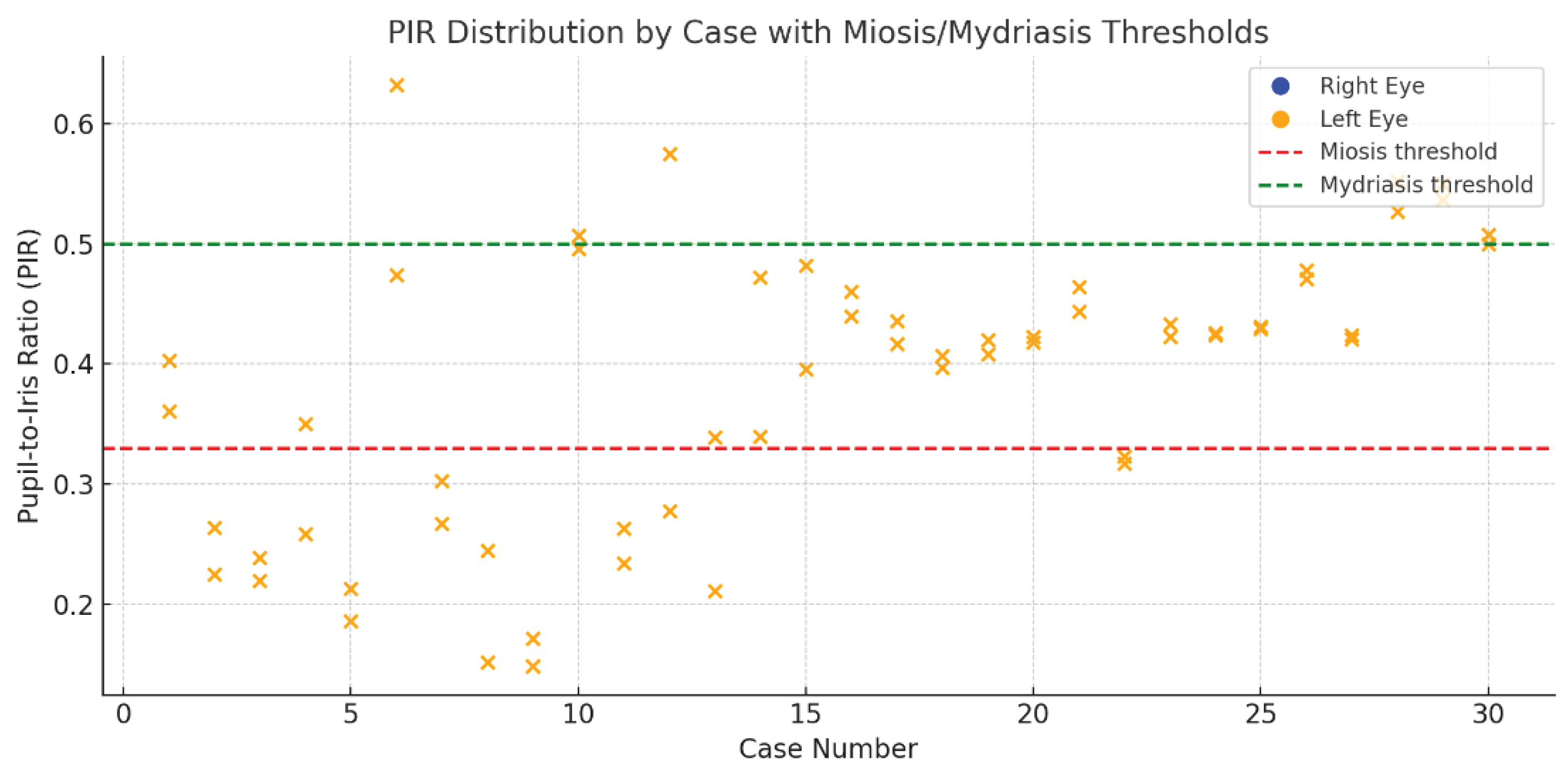

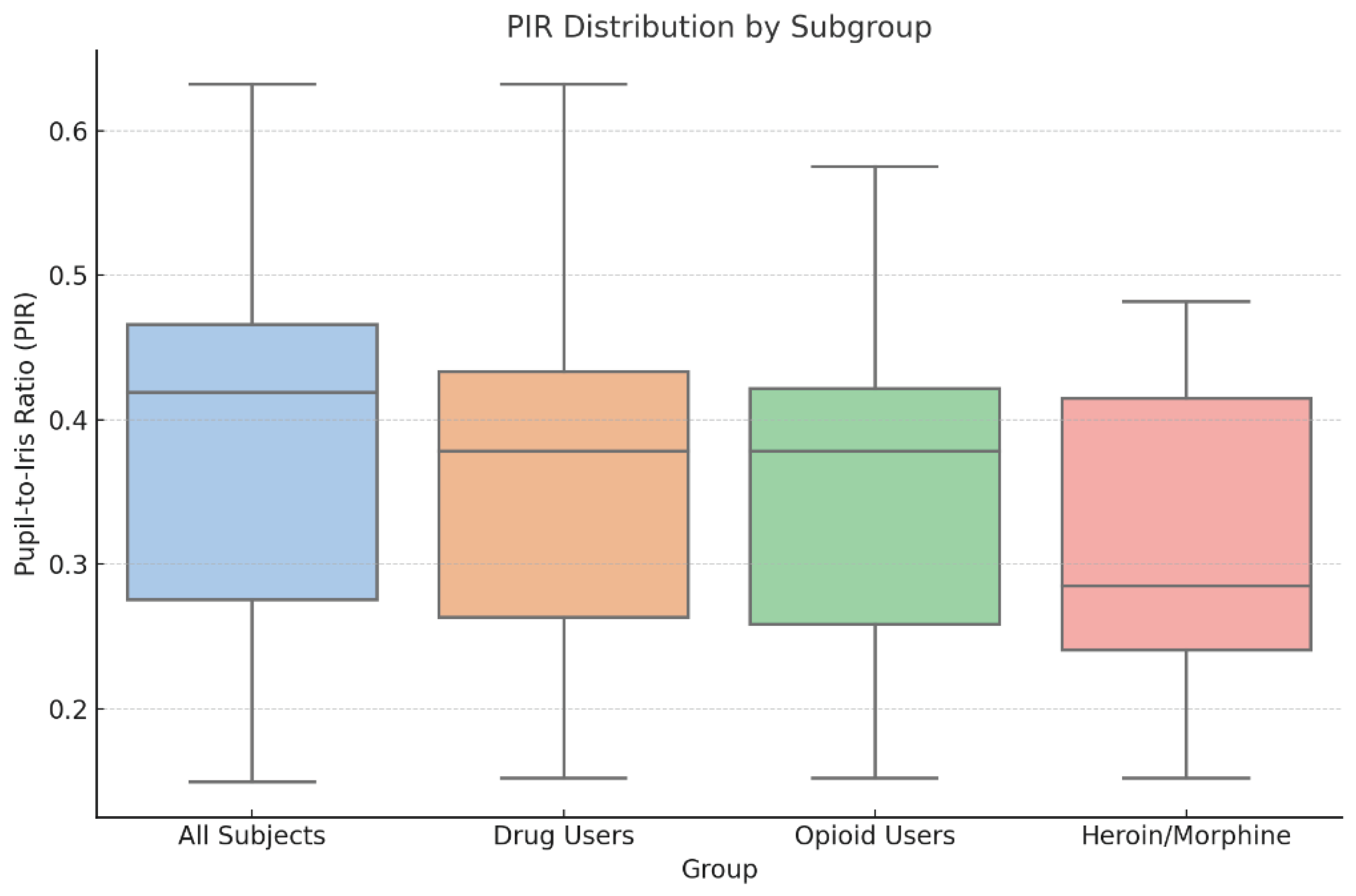

The final sample included 30 cadavers, corresponding to 60 eyes analyzed within a postmortem interval of 24 to 36 hours (mean 28.7 h). The mean age of the decedents was 41.9 years (SD: 13.2), with a predominance of males. Toxicological screening identified 18 subjects (60%) as positive for at least one psychoactive substance. Among these, 11 cases involved opioids—primarily heroin and morphine, with one subject positive only for tramadol. The remaining cases showed cannabinoids, stimulants, or benzodiazepines, alone or in combination. The pupil-to-iris ratio (PIR) was calculated for each eye, ranging from 0.149 to 0.632. PIR values were categorized as miotic (< 0.33), intermediate (0.33–0.50), or mydriatic (> 0.50). Across the full sample, most eyes fell into the intermediate range. However, a distinct shift toward lower PIR values was observed in opioid-positive cases, particularly those with heroin or morphine. This pattern is clearly visualized in

Figure 1, which compares PIR values across major toxicological subgroups. The heroin/morphine group shows a markedly lower median PIR and narrower interquartile range compared to all other categories. Importantly, this group was the only one to demonstrate statistically significant PIR reduction compared to controls (p < 0.05), with a large effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.85) and estimated power of 0.70. No significant differences were observed in subjects exposed to cannabinoids, stimulants, or benzodiazepines.

A closer case-by-case view is provided in

Figure 2, where each point represents the PIR value of a single eye. A dense clustering of values below the miotic threshold (PIR = 0.33) can be seen in the left-most portion of the graph, corresponding to individuals positive for heroin or morphine. In contrast, control subjects and non-opioid cases display a more heterogeneous distribution, primarily centered in the intermediate range. No substantial anisocoria was detected.

4. Discussion

The influence of pharmacological agents on pupil size is a well-established clinical observation. In emergency medicine and toxicology, the size and reactivity of the pupil are often used as immediate diagnostic clues, with opioid-induced miosis and stimulant-induced mydriasis serving as textbook examples. However, this link—so readily invoked in the living—has until now been largely ignored in the postmortem setting. Several reasons likely explain this gap in the literature. First and foremost is the practical difficulty of obtaining accurate and reproducible pupillary measurements after death. The ocular globe is particularly sensitive to postmortem changes: corneal opacity, intraocular pressure fluctuations, eyelid positioning, and the onset of decomposition all interfere with the ability to visually assess pupillary diameter with any confidence. Moreover, most forensic practitioners tend to prioritize toxicological testing over morphometric indicators, assuming that the loss of autonomic control renders the pupil diagnostically irrelevant. Additionally, in modern forensic practice, substance-related deaths frequently involve complex polypharmacy, often including combinations of opioids, benzodiazepines, stimulants, alcohol, and therapeutic agents. In such cases, the expected pharmacological effect on pupil size may be attenuated, masked, or even reversed by the opposing actions of different substances. This confounding factor further discourages reliance on any single visible sign—especially one as dynamic and delicate as the pupil. Despite these limitations, our study demonstrates that a statistically significant postmortem signature of opioid-induced miosis can still be detected and quantified. Subjects with confirmed morphine or heroin exposure exhibited a consistent reduction in the pupil-to-iris ratio (PIR), even 24 to 36 hours after death. This is particularly noteworthy given that the postmortem interval itself tends to favor passive mid-dilation due to loss of muscle tone. The fact that a miotic signal remains detectable suggests that certain pharmacodynamic effects may outlast death’s generalizing processes, particularly when the substance involved acts directly on smooth muscle tone via μ-opioid receptors. The success of this approach was enabled by a novel methodological innovation: the use of ChatGPT Plus as a multimodal artificial intelligence platform capable of extracting morphometric data from standard digital photographs. This allowed us to apply a scale-independent, reproducible PIR metric without relying on physical measurement or image standardization. This is, to our knowledge, the first forensic study to apply this type of AI-driven methodology to postmortem ocular imaging. The simplicity and accessibility of this tool make it especially attractive: a single photograph of the eye, taken at autopsy or even at the death scene, could be processed by an AI-supported mobile app to provide real-time PIR analysis. This could supplement preliminary diagnostic impressions or guide toxicological prioritization. Nevertheless, several limitations must be acknowledged. Most importantly, the sample size, while sufficient to demonstrate statistical significance in the heroin/morphine subgroup, remains too limited to draw conclusions about other categories. Specifically, while PIR values appeared slightly elevated in some stimulant-positive cases (suggesting possible mydriatic effect), the number of such cases was insufficient to establish significance. Future studies with larger cohorts will be needed to investigate whether postmortem mydriasis associated with stimulant use can be reliably detected. Another limitation lies in the variability of postmortem intervals, even within the restricted 24–36 hour window. While efforts were made to standardize imaging and anatomical selection, environmental conditions, decomposition rates, and time since last drug intake could not be fully controlled. Moreover, as this was a retrospective analysis, polydrug interactions were present in many cases, limiting the ability to isolate pure pharmacological effects. Lastly, our measurements were performed under photographic rather than direct optical conditions, and although the PIR provides a normalized metric, image quality, lighting, and perspective may still introduce subtle biases. Interobserver reliability was not evaluated, although the use of AI likely reduces manual error and improves reproducibility across institutions.

5. Conclusions

This study represents the first attempt to objectively measure and validate the persistence of drug-induced pupillary changes after death, specifically miosis associated with opioid use. By applying a multimodal artificial intelligence platform to standard postmortem photographs, we demonstrated that the pupil-to-iris ratio (PIR) can detect a statistically significant reduction in pupil size in subjects exposed to heroin and morphine. This observation, long assumed in clinical practice, now receives its first evidence-based confirmation in the forensic domain. Importantly, this method is not intended to replace traditional toxicological investigations, which remain the gold standard for postmortem substance detection. However, PIR analysis may offer a valuable adjunct tool—particularly in cases where the history of drug use is unknown, contradictory, or difficult to establish. A simple eye photograph, processed through a validated algorithm, could help raise early suspicion of opioid involvement and guide the decision to perform toxicological testing in ambiguous cases. Given the accessibility of the technology and the minimal cost involved, this approach could be easily replicated across forensic institutions. Further studies with larger samples will be necessary to validate its applicability to other substance classes and to refine its integration into routine forensic workflows. As such, this research offers both a methodological innovation and a practical contribution to the evolving interface between digital tools and forensic science.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.N., E.d’A., P.E.N. and D.N.; methodology, M.N, P.E.N.; software, M.N.; validation, M.N., D.N., E.L., A.C. and G.T.; formal analysis, M.N.; investigation, M.N., E.L., A.C.; resources, M.N.; data curation, M.N.; writing—original draft preparation, M.N.; writing—review and editing, M.N., D.N., and E.d’A.; visualization, M.N.; supervision, E.D.A.; project administration, E.d’A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because the postmortem ocular photographs were acquired as part of standard forensic procedures. Their use for research purposes, following full anonymization, was authorized by the competent Public Prosecutor's Office.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author. Some data are not publicly available due to medico-legal confidentiality constraints.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Smith, P.G. Neural regulation of the pupil. In: Binder MD, Hirokawa N, Windhorst U, editors. Encyclopedia of Neuroscience. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2009. [CrossRef]

- Maheu, M.; Donner, T.H.; Wiegert, J.S. Serotonergic and noradrenergic interactions in pupil-linked arousal. bioRxiv. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.; Gold, J.I. Pupil size as a window on neural substrates of cognition. Trends Cogn Sci. 2020, 24, 466–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winn, B.; Whitaker, D.; Elliott, D.B.; Phillips, N.J. Factors affecting light-adapted pupil size in normal human subjects. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1994, 35, 1132–1137. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Watson, A.B.; Yellott, J.I. A unified formula for light-adapted pupil size. J Vis. 2012, 12, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieberman, J.D.; Pasquale, M.D.; Garcia, R.; Cipolle, M.D.; Li, P.; Wasser, T.E. Use of admission Glasgow Coma Score, pupil size, and pupil reactivity to determine outcome for trauma patients. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2003, 55, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adoni, A.; McNett, M. The pupillary response in traumatic brain injury: a guide for trauma nurses. J Trauma Nurs. 2007, 14, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura, S.; Uji, M.; Watanabe, H.; Kido, T.; Ito, T.; Nakano, Y.; et al. A case of Wernicke's encephalopathy with objective evaluation of pupil findings using a pupillometer. Cureus 2025, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menozzi, M.; Cattadori, E.; Comelli, I.; et al. The use of automated pupillometry in critically ill cirrhotic patients with hepatic encephalopathy. J Crit Care 2021, 62, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaffe, N.S. The pupil in syphilis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1953, 36, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novitskaya, E.S.; Watts, P.; Abdul-Rahim, A.; et al. Effects of some ophthalmic medications on pupil size: a literature review. Can J Ophthalmol. 2009, 44, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, R.B.; Adler, M.W.; Korczyn, A.D. The pupillary effects of opioids. Life Sci. 1983, 33, 495–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campobasso, C.P.; Laviola, P.; Pascale, N.; Dell’Anna, A.; Fineschi, V. Pupillary effects in habitual cannabis consumers quantified with pupillography. Forensic Sci Int 2020, 317, 110559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickworth, W.B.; Murillo, R. Pupillometry and eye tracking as predictive measures of drug abuse. In: Karch SB, editor. Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Abused Drugs. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2008. p.127–41.

- Fleischer, L.; Klotz, A.; Graw, M.; Hess, C. Measurement of postmortem pupil size: a new method with excellent reliability and its application to pupil changes in the early postmortem period. J Forensic Sci. 2017, 62, 791–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwivedi, S.; Srivastava, A.K.; Sharma, A.K.; Singh, S. Determining pupillary reaction time using pilocarpine eye drop: A postmortem study. J Indian Acad Forensic Med 2022, 44, 2–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trokielewicz, M.; Czajka, A.; Maciejewicz, P. Postmortem human iris recognition. In: 2016 International Conference on Biometrics (ICB). IEEE; 2016.

- Yoshimiya, M.; Shimbashi, S.; Hyodoh, H. Postmortem changes in the eye on computed tomography images. Leg Med (Tokyo) 2024, 70, 102477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nioi, M.; Locci, E.; D’aloja, E.; Chighine, A.; Napoli, P.E. Postmortem ocular findings in the optical coherence tomography era: a proof of concept study based on six forensic cases. Diagnostics. 2021, 11, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nioi, M.; Napoli, P.E.; Chighine, A.; Locci, E.; D’aloja, E. The influence of eyelid position and environmental conditions on the corneal changes in early postmortem interval: a prospective, multicentric OCT study. Diagnostics. 2022, 12, 2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nioi, M.; Locci, E.; Tanda, G.; Nieddu, D.; D’aloja, E. Creation of an experimental animal model for the study of postmortem dark scleral spots. Forensic Sci. 2024, 4, 487–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trokielewicz, M.; Czajka, A.; Maciejewicz, P. Postmortem iris decomposition and its dynamics in morgue conditions. J Forensic Sci. 2020, 65, 1530–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).