Submitted:

16 May 2025

Posted:

19 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Saudi Dairy Sector and Its Supply Chain

2.2. Traceability Technologies

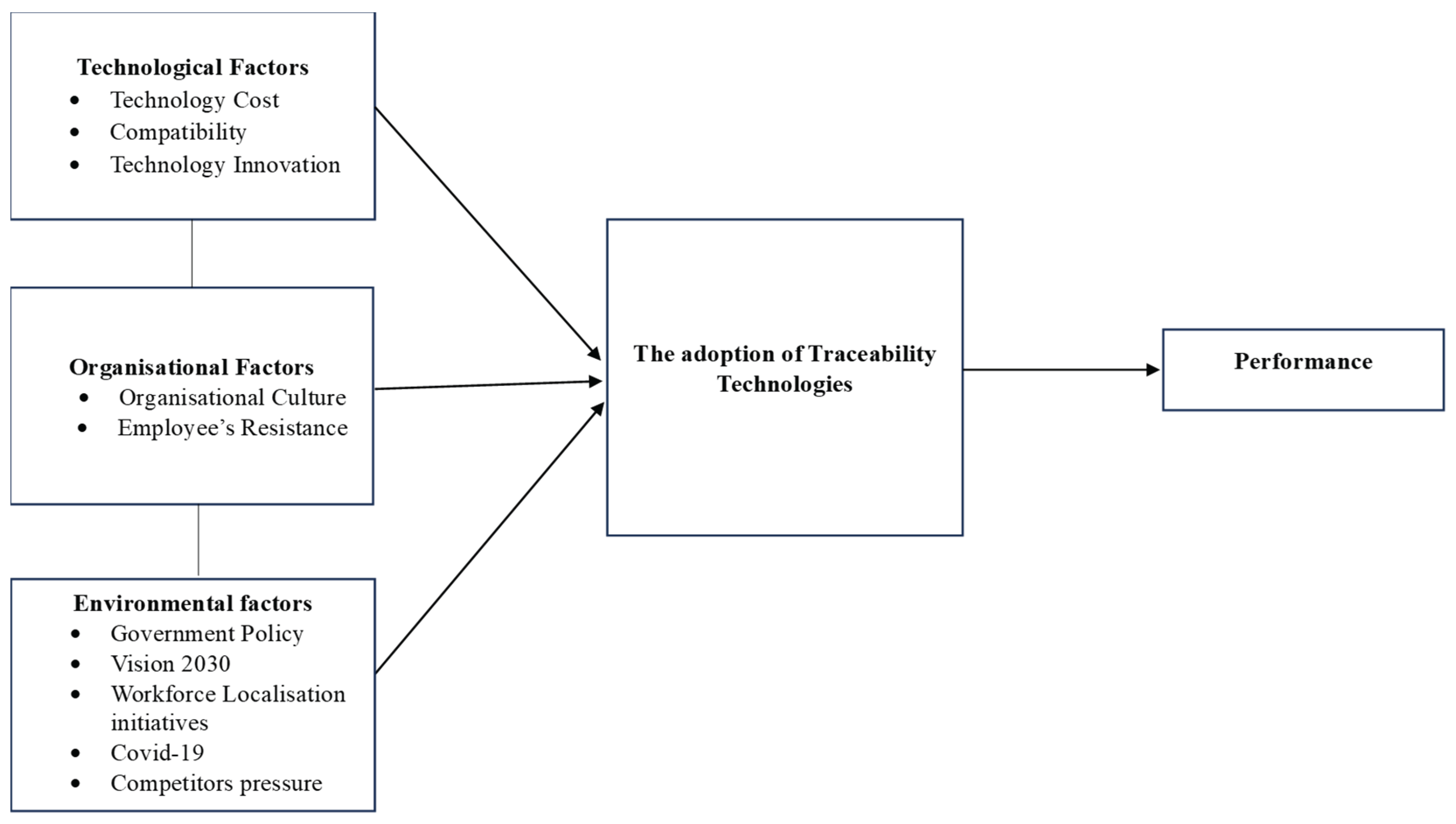

2.3. Technological, Organisational and Environmental (TOE) Dimensions

2.3.1. Technological Factors

2.3.2. Organisational Factors

2.3.3. Environmental Factors

3. Methodology

3.1. Sampling and Data Collection

3.2. Data Analysis

3.3. Findings

3.4. Reliability and Validity of the Findings

4. Discussion and Implications

4.1. Development of Study Proposition

4.2. Theoretical Contribution

4.3. Practical Implications

5. Conclusion and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abad, E.; Palacio, F.; Nuin, M.; De Zarate, A. G.; Juarros, A.; Gómez, J. M.; Marco, S. RFID smart tag for traceability and cold chain monitoring of foods: Demonstration in an intercontinental fresh fish logistic chain. Journal of food engineering 2009, 93(4), 394–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abunadi, I. Influence of culture on e-government acceptance in Saudi Arabia. PhD thesis, Griffith University, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, W. A. H.; MacCarthy, B. L. Blockchain-enabled supply chain traceability–How wide? How deep? International Journal of Production Economics 263 2023, 2023/09/01/, 108963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiyar, A.; Pingali, P. J. F. S. Pandemics and food systems-towards a proactive food safety approach to disease prevention & management. 2020, 12(4), 749–756. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Al-Ghaith, W. A. Applying decomposed theory of planned behaviour towards a comprehensive understanding of social network usage in Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Information Technology and Computer Science (IJITCS) 2016, 8(5), 52–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlBar, A. M.; Hoque, M. R. Factors affecting the adoption of information and communication technology in small and medium enterprises: A perspective from rural Saudi Arabia. Information Technology for Development 2019, 25(4), 715–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldraehim, M. S. A. Cultural impact on e-service use in Saudi Arabia Queensland University of Technology. 2013. Available online: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/60899/3/Majid_Saad_Aldraehim_Thesis.pdf.

- AlGhamdi, R.; Drew, S.; Al-Ghaith, W. Factors Influencing e-commerce Adoption by Retailers in Saudi Arabia: a qualitative analysis. The Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries 2011, 47(1), 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqasir, A.; Ohtsuka, K. The Impact of Religio-Cultural Beliefs and Superstitions in Shaping the Understanding of Mental Disorders and Mental Health Treatment among Arab Muslims. Journal of Spirituality in Mental Health 2023, 26(3), 279–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, A. S.; Goodwin, R.; de Vries, D. Cultural factors influencing e-commerce usability in Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Advanced and Applied Sciences 2018, 5(6), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, S.; Wamba, S. F. Determinants of RFID technology adoption intention in the Saudi retail industry: an empirical study. 2012 45th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Alshuaibi, A. Technology as an important role in the implementation of Saudi Arabia’s vision 2030. International Journal of Business, Humanities and Tchnology 2017, 7(2), 52–62. [Google Scholar]

- Ameen, N.; Willis, R. The effect of cultural values on technology adoption in the Arab countries. International Journal of Information Systems 2 2015, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Andoni, M.; Robu, V.; Flynn, D.; Abram, S.; Geach, D.; Jenkins, D.; McCallum, P.; Peacock, A. Blockchain technology in the energy sector: A systematic review of challenges and opportunities. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 100 2019, 143–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asharq, A.-A. Saudi dairy industry produces 7 million liters per day. Saudi 24 News. 2021. Available online: https://www.saudi24news.com/2021/03/saudi-dairy-industry-to-produce-7-million-liters-per-day.html.

- Awa, H. O.; Ukoha, O.; Emecheta, B. C. Using TOE theoretical framework to study the adoption of ERP solution. Cogent Business & Management 2016, 3(1), 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Baralla, G.; Pinna, A.; Tonelli, R.; Marchesi, M.; Ibba, S. Ensuring transparency and traceability of food local products: A blockchain application to a Smart Tourism Region. Concurrency and Computation: Practice and Experience 2021, 33(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battini, D.; Berti, N.; Finco, S.; Zennaro, I.; Das, A. Towards industry 5.0: A multi-objective job rotation model for an inclusive workforce. International Journal of Production Economics 2022, 250, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnke, K.; Janssen, M. Boundary conditions for traceability in food supply chains using blockchain technology. International Journal of Information Management 2020, 52, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, M.; Wamba, S. F. A conceptual framework of RFID adoption in retail using TOE framework. In Technology adoption and social issues: Concepts, methodologies, tools, and applications; IGI global, 2018; pp. 69–102. [Google Scholar]

- Birt, L.; Scott, S.; Cavers, D.; Campbell, C.; Walter, F. Member checking: a tool to enhance trustworthiness or merely a nod to validation? Qualitative Health Research 2016, 26(13), 1802–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosona, T.; Gebresenbet, G. Food traceability as an integral part of logistics management in food and agricultural supply chain. Food Control 2013, 33(1), 32–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calisir, F.; Altin Gumussoy, C.; Bayram, A. Predicting the behavioral intention to use enterprise resource planning systems: An exploratory extension of the technology acceptance model. Management research news 2009, 32(7), 597–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caro, M. P.; Ali, M. S.; Vecchio, M.; Giaffreda, R. Blockchain-based traceability in Agri-Food supply chain management: A practical implementation. 2018 IoT Vertical and Topical Summit on Agriculture-Tuscany (IOT Tuscany), May 8-9; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Casino, F.; Kanakaris, V.; Dasaklis, T. K.; Moschuris, S.; Stachtiaris, S.; Pagoni, M.; Rachaniotis, N. P. Blockchain-based food supply chain traceability: a case study in the dairy sector. International journal of production research 2021, 59(19), 5758–5770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S. E.; Chen, Y.-C.; Lu, M.-F. Supply chain re-engineering using blockchain technology: A case of smart contract based tracking process. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 144 2019, 2019/07/01/, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlebois, S.; Haratifar, S. The perceived value of dairy product traceability in modern society: An exploratory study. Journal of dairy science 2015, 98(5), 3514–3525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chau, P. Y.; Hu, P. J. H. Information technology acceptance by individual professionals: A model comparison approach. Decision sciences 2001, 32(4), 699–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Tian, Z.; Xu, F. What are cost changes for produce implementing traceability systems in China? Evidence from enterprise A. Applied Economics 2019, 51(7), 687–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimmino, F.; Catapano, A.; Petrella, L.; Villano, I.; Tudisco, R.; Cavaliere, G. Role of Milk Micronutrients in Human Health. Frontiers in Bioscience-Landmark 2023, 28(2), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clohessy, T.; Acton, T. Investigating the influence of organizational factors on blockchain adoption. Industrial Management & Data Systems 2019a, 119(7), 1457–1491. [Google Scholar]

- Clohessy, T.; Acton, T. Investigating the influence of organizational factors on blockchain adoption: An innovation theory perspective. Industrial management & data systems 2019b, 119(7), 1457–1491. [Google Scholar]

- Compagnucci, L.; Lepore, D.; Spigarelli, F.; Frontoni, E.; Baldi, M.; Di Berardino, L. Uncovering the potential of blockchain in the agri-food supply chain: An interdisciplinary case study. Journal of Engineering and Technology Management 65 2022, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corallo, A.; Latino, M. E.; Menegoli, M.; Pontrandolfo, P. A systematic literature review to explore traceability and lifecycle relationship. International journal of production research 2020, 58(15), 4789–4807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, W. Research Design, Qualitative, Quantitave, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 4 ed.; Knight, V., Ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc., 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dandage, K.; Badia-Melis, R.; Ruiz-García, L. Indian perspective in food traceability: A review. Food Control 71 2017, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vass, T.; Shee, H.; Miah, S. J. The effect of “Internet of Things” on supply chain integration and performance: An organisational capability perspective. Australasian Journal of Information Systems 2018, 22(4), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vass, T.; Shee, H.; Miah, S. J. IoT in supply chain management: a narrative on retail sector sustainability. International Journal of Logistics Research and Applications 2021, 2021/11/02, 24(6), 605–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demestichas, K.; Peppes, N.; Alexakis, T.; Adamopoulou, E. Blockchain in Agriculture Traceability Systems: A Review. Applied Sciences 2020, 10(12), 4133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denzin, N.; Lincoln, Y. The landscape of qualitative research: theories and issues; Thousand Oaks: Sage, 1998; Vol. 1, Available online: https://library.wur.nl/WebQuery/titel/938654.

- dos Santos, R. B.; Torrisi, N. M.; Yamada, E. R. K.; Pantoni, R. P. IGR token-raw material and ingredient certification of recipe based foods using smart contracts. Informatics 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, M. I. Determinants of e-commerce customer satisfaction, trust, and loyalty in Saudi Arabia. Journal of Electronic Commerce Research 2011, 12(1), 78. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K. M. Building theories from case study research. Academy of management review 1989, 14(4), 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, P. (Ed.) RFID Near-field Communication (NFC)-Based Sensing Technology in Food Quality Control. In Biosensing and Micro-Nano Devices: Design Aspects and Implementation in Food Industries; Chandra, P. (Ed.) Springer Nature Singapore; Singapore, 2022; pp. 219–241. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, H.; Wang, X.; Duan, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X. Applying blockchain technology to improve agri-food traceability: A review of development methods, benefits and challenges. Journal of Cleaner Production 260 2020, 2020/07/01/, 121031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Fu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Xu, M.; Zhang, X. Development and evaluation on a RFID-based traceability system for cattle/beef quality safety in China. Food Control 2013, 31(2), 314–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fereday, J.; Muir-Cochrane, E. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. International journal of qualitative methods 2006, 5(1), 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanakis, C. M.; Rizou, M.; Aldawoud, T. M. S.; Ucak, I.; Rowan, N. J. Innovations and technology disruptions in the food sector within the COVID-19 pandemic and post-lockdown era. Trends in food science & technology 110 2021, 2021/04/01/, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvez, J. F.; Mejuto, J. C.; Simal-Gandara, J. Future challenges on the use of blockchain for food traceability analysis. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 107 2018, 2018/10/01/, 222–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangwar, H.; Date, H.; Ramaswamy, R. Understanding determinants of cloud computing adoption using an integrated TAM-TOE model. Journal of Enterprise Information Management 2015, 28(1), 107–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangwar, H.; Date, H.; Raoot, A. Review on IT adoption: insights from recent technologies. Journal of enterprise information management 2014, 27(4), 488–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Schroeder, T. C. Effects of label information on consumer willingness-to-pay for food attributes. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 2009, 91(3), 795–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharaibeh, M. K.; Gharaibeh, N. K.; De Villiers, M. V. A Qualitative Method to Explain Acceptance of Mobile Health Application: Using Innovation Diffusion Theory. International Journal of Advanced Science and Technology 2020, 29(4), 3426–3432. [Google Scholar]

- Gökalp, E.; Gökalp, M. O.; Çoban, S. Blockchain-based supply chain management: understanding the determinants of adoption in the context of organizations. Information systems management 2022, 39(2), 100–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, S. M. Pandemic Challenges Highlight the Importance of the New Era of Smarter Food Safety, 2020; Retrieved on 2 Jan 2025 from https://www.fda.gov/news-events/fda-voices/pandemic-challenges-highlight-importance-new-era-smarter-food-safety.

- Hill, C. E.; Straub, D. W.; Loch, K. D.; Cotterman, W.; El-Sheshai, K. The impact of Arab culture on the diffusion of information technology: a culture-centered model. Proceedings of The Impact of Informatics on Society: Key Issues for Developing Countries, IFIP, 9; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, J.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, M. Sustainable supply chain management practices, supply chain dynamic capabilities, and enterprise performance. Journal of Cleaner Production 172 2018, 2018/01/20/, 3508–3519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, P.-F.; Ray, S.; Li-Hsieh, Y.-Y. Examining cloud computing adoption intention, pricing mechanism, and deployment model. International Journal of Information Management 2014, 34(4), 474–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H. f.; Hu, P. J.-H.; Al-Gahtani, S. S. User acceptance of computer technology at work in Arabian culture: A model comparison approach. In Technology Adoption and Social Issues: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications; IGI Global, 2018; pp. 1521–1544. [Google Scholar]

- IFIF/FAO. Manual on Good Practices for the Feed Sector—Implementing the Codex Alimentarius Code of Practice on Good Animal Feeding, retrieved from https://ifif.org/our-work/project/ifif-fao-feed-manual/ on 2 Dec 2024. FAO Rome, Italy. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ifinedo, P. Internet/e-business technologies acceptance in Canada’s SMEs: an exploratory investigation. Internet research 2011, 21(3), 255–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.; Cullen, J. M. Food traceability: A generic theoretical framework. Food Control 123 2021, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO. ISO 12875 Traceability of finfish products—Specification on the information to be recorded in captured finfish distribution chains. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, L.; Bhardwaj, S. Enterprise cloud computing: key considerations for adoption. International Journal of Engineering and Information Technology for Development 2010, 2(2), 113–117. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, S.-H. An empirical study on the factors influencing RFID adoption and implementation. Management Review: An International Journal 2010, 5(2), 55–73. [Google Scholar]

- Jayashankar, P.; Nilakanta, S.; Johnston Wesley, J.; Gill, P.; Burres, R. IoT adoption in agriculture: the role of trust, perceived value and risk. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing 2018, 33(6), 804–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Feng, Q.; Fan, T.; Lei, Q. RFID technology and its applications in Internet of Things (IoT). 2012 2nd International Conference on Consumer Electronics, Communications and Networks (CECNet); 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, S.; Zhou, L. Consumer interest in information provided by food traceability systems in Japan. Food Quality and Preference 2014, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kai-ming Au, A.; Enderwick, P. A cognitive model on attitude towards technology adoption. Journal of Managerial Psychology 2000, 15(4), 266–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaitzi, D.; Jesus, V.; Campelos, I. DETERMINANTS OF BLOCKCHAIN ADOPTION AND PERCEIVED BENEFITS IN FOOD SUPPLY CHAINS. In Logistics Research Network (LRN); University of Northampton, 2019, 6 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kallio, H.; Pietilä, A. M.; Johnson, M.; Kangasniemi, M. Systematic methodological review: developing a framework for a qualitative semi-structured interview guide. Journal of advanced nursing 2016, 72(12), 2954–2965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamilaris, A.; Fonts, A.; Prenafeta-Boldύ, F. X. The rise of blockchain technology in agriculture and food supply chains. Trends in food science & technology 91 2019, 640–652. [Google Scholar]

- Ketokivi, M.; Choi, T. Renaissance of case research as a scientific method. Journal of Operations management 2014, 32(5), 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W. R.; Aung, M. M.; Chang, Y. S.; Makatsoris, C. Freshness Gauge based cold storage management: A method for adjusting temperature and humidity levels for food quality. Food Control 47 2015, 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechler, S.; Canzaniello, A.; Roßmann, B.; von der Gracht, H. A.; Hartmann, E. Real-time data processing in supply chain management: revealing the uncertainty dilemma. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management 2019, 49(10), 1003–1019. [Google Scholar]

- Legenvre, H.; Hameri, A.-P. The emergence of data sharing along complex supply chains. International Journal of Operations & Production Management 2024, 44(1), 292–297. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard-Barton, D. A dual methodology for case studies: Synergistic use of a longitudinal single site with replicated multiple sites. Organization science 1990, 1(3), 248–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Bhutto, T. A.; Nasiri, A. R.; Shaikh, H. A.; Samo, F. A. Organizational innovation: the role of leadership and organizational culture. International Journal of Public Leadership 2018, 14(1), 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, J.-W. Critical factors for cloud based e-invoice service adoption in Taiwan: An empirical study. International Journal of Information Management 2015, 35(1), 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Chang, S.-C.; Chou, T.-H.; Chen, S.-C.; Ruangkanjanases, A. Consumers’ Intention to Adopt Blockchain Food Traceability Technology towards Organic Food Products. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public health 2021, 18(3), 912–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Gao, Z.; Nayga, R. M., Jr.; Snell, H. A.; Ma, H. Consumers’ valuation for food traceability in China: Does trust matter? Food Policy 2019, 88, 101768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, B.; Falcão, L.; Canellas, T. Supply-Side: Mapping High Capacity Suppliers of Goods and Services. In Supply Chain and Logistics Management: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications; Management Association , I. R., Ed.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 1246–1264. [Google Scholar]

- Low, C.; Chen, Y.; Wu, M. Understanding the determinants of cloud computing adoption. Industrial management & data systems 2011, 111(7), 1006–1023. [Google Scholar]

- Luomala, H.; Jokitalo, M.; Karhu, H.; Hietaranta-Luoma, H.-L.; Hopia, A.; Hietamäki, S. Perceived health and taste ambivalence in food consumption. Journal of Consumer Marketing 2015, 32(4), 290–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusk, J. L.; Tonsor, G. T.; Schroeder, T. C.; Hayes, D. J. Effect of government quality grade labels on consumer demand for pork chops in the short and long run. Food Policy 77 2018, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainetti, L.; Patrono, L.; Stefanizzi, M. L.; Vergallo, R. An innovative and low-cost gapless traceability system of fresh vegetable products using RF technologies and EPCglobal standard. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2013, 98, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchant-Forde, J. N.; Boyle, L. A. COVID-19 effects on livestock production: a one welfare issue. Frontiers in veterinary science 7 2020, 585787. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, C.; Rossman, G. B. Designing qualitative research; Sage publications, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Matias, J. B.; Hernandez, A. A. Cloud computing adoption intention by MSMEs in the Philippines. Global Business Review 2021, 22(3), 612–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattevi, Mattia and Jones, & Alun, J. Traceability in the food supply chain: awareness and attitudes of UK small and medium-sized enterprises. Food control 2016, 64, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattevi, M.; Jones, J. A. Food supply chain: are UK SMEs aware of concept, drivers, benefits and barriers, and frameworks of traceability? British Food Journal 2016, 118(5). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melatu Samsi, S. Z.; Ibrahim, A. P. D. O.; Tasnim, R. Review on Knowledge Management as a Tool for Effective Traceability System in Halal Food Industry Supply Chain. Journal of research and innovation in information systems 1 2012, 78–85. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M. B.; Huberman, A. M. Qualitative data analysis: A sourcebook of new methods; Sage, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, D.; Muduli, K.; Raut, R.; Narkhede, B. E.; Shee, H.; Jana, S. K. Challenges Facing Artificial Intelligence Adoption during COVID-19 Pandemic: An Investigation into the Agriculture and Agri-Food Supply Chain in India. Sustainability 2023, 15(8), 318–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muduli, K.; Raut, R.; Narkhede, B. E.; Shee, H. (Eds.) Blockchain technology for enhancing supply chain performance and reducing the threats arising from the COVID-19 pandemic (14); MDPI, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Nam, K.; Dutt, C. S.; Chathoth, P.; Daghfous, A.; Khan, M. S. The adoption of artificial intelligence and robotics in the hotel industry: prospects and challenges. Electronic Markets 2021, 2021/09/01, 31(3), 553–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NILDP. National Industrial Development and Logistics Program; 2025. Available online: https://www.vision2030.gov.sa/en/programs/NIDLP (accessed on 2 Jan 2025).

- Nitaqat. Nitaqat Mutawar Program, accessed on 5 Jan 2025 in https://www.hrsd.gov.sa/en/knowledge-centre/decisions-and-regulations/regulation-and-procedures/832742. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ubacht, S.; Ubacht, J.; Janssen, M. Blockchain in government: Benefits and implications of distributed ledger technology for information sharing. Government Information Quarterly 2017, 2017/09/01/, 34(3), 355–364. [Google Scholar]

- Orji, I. J.; Kusi-Sarpong, S.; Huang, S.; Vazquez-Brust, D. Evaluating the factors that influence blockchain adoption in the freight logistics industry. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review 141 2020, 102025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parveen, F.; Sulaiman, A. Technology complexity, personal innovativeness and intention to use wireless internet using mobile devices in Malaysia. International Review of Business Research Papers 2008, 4(5), 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, R.; Xiong, L.; Yang, Z. Exploring Tourist Adoption of Tourism Mobile Payment: An Empirical Analysis. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 2012, 7(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigini, D.; Conti, M. NFC-based traceability in the food chain. Sustainability 2017, 9(10), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramdani, B.; Kawalek, P.; Lorenzo, O. Predicting SMEs’ adoption of enterprise systems. Journal of enterprise information management 2009, 22(1/2), 10–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, G.; O’Beirne, N.; Gibson, N. How companies can reshape results and plan for a COVID-19 recovery. EY. 2020. Available online: https://www.ey.com/en_ie/strategy-transactions/companies-can-reshape-results-and-plan-for-covid-19-recovery.

- Rizou, M.; Galanakis, I. M.; Aldawoud, T. M.; Galanakis, C. M. Safety of foods, food supply chain and environment within the COVID-19 pandemic. Trends in food science & technology 102 2020, 293–299. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, E. M. Diffusion of innovations; The Free Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Garcia, L.; Lunadei, L.; Barreiro, P.; Robla, I. A review of wireless sensor technologies and applications in agriculture and food industry: state of the art and current trends. sensors 2009, 9(6), 4728–4750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salwani, M. I.; Marthandan, G.; Norzaidi, M. D.; Chong, S. C. J. I. M.; Security, C. E-commerce usage and business performance in the Malaysian tourism sector: empirical analysis. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Saurabh, S.; Dey, K. Blockchain technology adoption, architecture, and sustainable agri-food supply chains. Journal of Cleaner Production 284 2021, 2021/02/15/, 124731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schillewaert, N.; Ahearne, M. J.; Frambach, R. T.; Moenaert, R. K. The adoption of information technology in the sales force. Industrial marketing management 2005, 34(4), 323–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shee, H.; Miah, S.; De Vass, T. Impact of smart logistics on smart city sustainable performance: an empirical investigation. The International Journal of Logistics Management 2021, 32(3), 821–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shee, H.; Miah, S.; Fairfield, L.; Pujawan, N. The impact of cloud-enabled process integration on supply chain performance and firm sustainability: the moderating role of top management. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 2018, 23(6), 500–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, P.; Yan, B. Factors affecting RFID adoption in the agricultural product distribution industry: empirical evidence from China. SpringerPlus 5 2016, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siew, E.-G.; Rosli, K.; Yeow, P. H. Organizational and environmental influences in the adoption of computer-assisted audit tools and techniques (CAATTs) by audit firms in Malaysia. International journal of accounting information systems 36 2020, 100445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, D.; Segrave, M.; Quarshie, A.; Kach, A.; Handfield, R.; Panas, G.; Moore, H. The role of psychological distance in organizational responses to modern slavery risk in supply chains. Journal of Operations management 2021, 67(8), 989–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnenwald, D. H.; Maglaughlin, K. L.; Whitton, M. C. Using innovation diffusion theory to guide collaboration technology evaluation: work in progress. Paper presented at the Proceedings Tenth IEEE International Workshop on Enabling Technologies: Infrastructure for Collaborative Enterprises. WET ICE in 20-22 June; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Surasak, T.; Wattanavichean, N.; Preuksakarn, C.; Huang, S. C. Thai agriculture products traceability system using blockchain and Internet of Things. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications 2019, 10(9), 578–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taboada, I.; Shee, H. Understanding 5G technology for future supply chain management. International Journal of Logistics Research & Applications 2020, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, T. S.; Lin, S.; Lai, K.-h. Adopters and non-adopters of e-procurement in Singapore: An empirical study. Omega 2009, 37(5), 972–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, H. Traceability in the food industry: An overview. Journal of Food Science 2009, 74(8), 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornatzky, L. G.; Fleischer, M. The processes of technological innovation; Lexington, D.C. Heath & Company, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Tornatzky, L. G.; Fleischer, M.; Chakrabarti, A. K. Processes of technological innovation; Lexington books, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Tóth, Z.; Sklyar, A.; Kowalkowski, C.; Sörhammar, D.; Tronvoll, B.; Wirths, O. Tensions in digital servitization through a paradox lens. Industrial marketing management 102 2022, 438–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdouw, C.; Robbemond, R. M.; Wolfert, J. ERP in agriculture: Lessons learned from the Dutch horticulture. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 114 2015, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; Bhattacharyya, S. S. Perceived strategic value-based adoption of Big Data Analytics in emerging economy. Journal of Enterprise Information Management 2017, 30(3), 354–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishvakarma, N. K.; Singh, R. K.; Sharma, R. Cluster and DEMATEL analysis of key RFID implementation factors across different organizational strategies. Global Business Review 2022, 23(1), 176–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, D. G. (Ed.) Wireless sensor networks (WSNs) in the agricultural and food industries. Caldwell, D. G. (Ed.) In Robotics and Automation in the Food Industry; Woodhead Publishing, 2013; pp. 171–199. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Li, D.; O’brien, C. Optimisation of traceability and operations planning: an integrated model for perishable food production. International journal of production research 2009, 47(11), 2865–2886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-M.; Wang, Y.-S.; Yang, Y.-F. Understanding the determinants of RFID adoption in the manufacturing industry. Technological forecasting and social change 2010, 77(5), 803–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, L.-W.; Leong, L.-Y.; Hew, J.-J.; Tan, G. W.-H.; Ooi, K.-B. Time to seize the digital evolution: Adoption of blockchain in operations and supply chain management among Malaysian SMEs. International Journal of Information Management 52 2020, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongprawmas, R.; Canavari, M. Consumers’ willingness-to-pay for food safety labels in an emerging market: The case of fresh produce in Thailand. Food Policy 69 2017, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Wang, H.; Zhu, D.; Hu, W.; Wang, S. Chinese consumers’ willingness to pay for pork traceability information—The case of Wuxi. Agricultural Economics 2016, 47(1), 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; He, Q.; Li, Z.; Antoce, A. O.; Zhang, X. Improving traceability and transparency of table grapes cold chain logistics by integrating WSN and correlation analysis. Food Control 73 2017, 1556–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R. K. Case study research: Design and methods fourth edition. In SAGE; Los Angeles, London, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R. K. Case study research and Applications Design and methods, 6 ed.; Thousand Oaks, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zadeh, A.; Akinyemi, B.; Jeyaraj, A.; M Zolbanin, H. Cloud ERP Systems for Small-and-Medium Enterprises: A Case Study in the Food Industry. Journal of Cases on Information Technology 2018, 20, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Moon, H. C. Investigating the impact of Industry 4.0 technology through a TOE-based innovation model. Systems 2023, 11(6), 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Pullman, M.; Xu, Z. The impact of food supply chain traceability on sustainability performance. Operations Management Research 2022, 15(1), 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Xu, Z. Traceability in food supply chains: a systematic literature review and future research directions. International Food and Agribusiness Management Review 2022, 25(2), 173–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žurbi, T.; Gregor-Svetec, D. Use of qr code in dairy sector in slovenia. SAGE open 2023, 13(2), 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Technologies | Purpose | Example | Features & Observations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Near Field Communication (NFC) | Identification | (Pigini & Conti, 2017) |

|

| Bar code | Identification | (Žurbi & Gregor-Svetec, 2023) |

|

| Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) | Identification | (Shi & Yan, 2016) |

|

| Blockchain | Data Integration | (Saurabh & Dey, 2021) |

|

| Internet of Things (IoT) | Data Integration | (de Vass et al., 2021) |

|

| Wireless Sensor Network (WSN) | Data Integration | (Wang & Li, 2013) |

|

| Sl. No |

Authors | Study Focus | Technological Factors | Organisational Factors | Environmental Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | (Zhong & Moon, 2023) | Industry 4.0 Technology: | compatibility, cost | Top management support, employee capability | Competitive pressure |

| 2 | Gökalp et al. (2022) | Blockchain technology | Complexity, relative advantage compatibility, trust standardisation, and scalability. |

Organisations’ IT resources, top management support, organisation size, financial resources | Competitive pressure, trading partner pressure, government policy and regulations, inter-organisational trust |

| 3 | Nam et al. (2021) |

Artificial intelligence and robotics | External IT expertise, relative advantage, complexity, internal IT expertise. | Market position, financial justification, resistance by employees | Customer readiness, customer expectation, competition, legal issues |

| 4 | Orji et al. (2020) | Blockchain technology | Infrastructural facility, complexity, availability of specific blockchain tools perceived benefits, privacy, compatibility, security | Presence of training facilities, top management support, firm size, capability of human resources, perceived costs, organisational culture | Government policies, competitive pressure, institutional-based trust, market turbulence, stakeholder pressure |

| 5 | Siew et al. (2020) | Computer-assisted audit tools and techniques (CAATTs) | n/a | Firm size, top management commitment, employee IT competency | Complexity of clients’ accounting information systems, perceived level of support of professional accounting bodies |

| 6 | (Clohessy & Acton, 2019a) | Blockchain technology | n/a | Top management support, organisational readiness, organisation size | n/a. |

| 7 | (Zadeh et al., 2018) | Cloud computing | Compatibility, relative advantage, complexity, ease of use, trialability, technology integration | Firm size | Competitive intensity, regulatory support |

| 8 | Verma and Bhattacharyya (2017) | Big data analytics | Complexity, compatibility, IT assets. | Top management support, organisation data environment, perceived costs | External pressure, industry type |

| 9 | Awa et al. (2016) | Enterprise resource planning (ERP) software | Technical know-how, perceived compatibility, perceived value, security, technology (ICT) infrastructure | Organisation-demographic composition, size, scope of business operations, subjective norms | Competitive pressure, external support, trading partners’ readiness |

| Code | Work Exp. | Job title | Firm size | First adopted FTT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 32 | Head of quality | Large | 2002 |

| B | 14 | Supply chain manager | Large | 2011 |

| C | 21 | Senior director of manufacturing | Large | 2010 |

| D | 19 | Head of Production | Large | 2013 |

| E | 26 | Supply chain manager | Medium | 2019 |

| F | 21 | The CEO | Medium | Not yet- adopting |

| G | 20 | Supply chain manager | Medium | 2014 |

| H | 17 | Plant manager | Small | Not yet |

| J | 18 | Manufacturing Manager | Small | Not yet |

| Code | Age | Gender | Citizenship | job role | Experience (years) |

Firm size | Location | Traceability technologies adopted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 52 | Male | Non- citizen | Head of quality | 32 | Large | Riyadh | 2002 |

| P2 | 37 | Male | Citizen | Supply chain manager | 14 | Large | Alahsa | 2011 |

| P3 | 46 | Male | Citizen | Senior director of manufacturing | 21 | Large | Riyadh | 2010 |

| P4 | 45 | Male | Citizen | Head of production | 19 | Large | Jeddah | 2013 |

| P5 | 50 | Male | Non-citizen | Supply chain manager | 26 | Medium | Alahsa | 2019 |

| P6 | 46 | Male | Citizen | The CEO | 21 | Medium | Alqassim | Not yet-adopting |

| P7 | 47 | Male | Non-citizen | Supply chain manager | 20 | Medium | Alahsa | 2014 |

| P8 | 43 | Male | Non-citizen | Plant manager | 17 | Small | Alqassim | Not yet-adopting |

| P9 | 41 | Male | Citizen | Manufacturing manager | 18 | Small | Jeddah | Not yet-adopting |

| Themes | P2 | P9 | P5 | P3 | P4 | P6 | P8 | P7 | P1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technology adoption | 21.06% | 12.06% | 10.96% | 13.67% | 9.1% | 7.97% | 7.19% | 8.39% | 9.6% |

| Environment | 29.53% | 13.32% | 12.68% | 16.85% | 8.99% | 2.73% | 4.65% | 4.98% | 6.26% |

| Competitors | 4.25% | 20.4% | 15.01% | 27.2% | 3.4% | 4.82% | 8.22% | 5.67% | 11.05% |

| Consumer pressure | 62.59% | 4.07% | 9.63% | 3.33% | 16.3% | 0% | 0% | 4.07% | 0% |

| Consumer Awareness | 62.59% | 4.07% | 9.63% | 3.33% | 16.3% | 0% | 0% | 4.07% | 0% |

| Government Support | 24.04% | 11.86% | 16.67% | 10.26% | 8.97% | 11.54% | 8.01% | 4.49% | 4.17% |

| Mandatory SFDA | 17.49% | 4.96% | 12.29% | 23.4% | 28.84% | 5.91% | 0% | 0% | 7.09% |

| Vision 2030 | 50% | 0% | 0% | 23.08% | 0% | 21.37% | 0% | 0% | 5.56% |

| Future challenges | 12.96% | 14.2% | 5.86% | 13.27% | 7.41% | 27.47% | 6.17% | 3.4% | 9.26% |

| Organisation | 10.33% | 13.09% | 8.01% | 20.84% | 14.87% | 7.39% | 14.16% | 4.81% | 6.5% |

| Organisational culture | 0% | 0% | 11.11% | 64.05% | 11.11% | 0% | 13.73% | 0% | 0% |

| Saudization-OC | 10.99% | 10.64% | 17.38% | 10.28% | 12.77% | 7.8% | 11.35% | 5.32% | 13.48% |

| Top Management support | 16.25% | 19.11% | 9.29% | 14.11% | 7.5% | 9.11% | 13.39% | 0.71% | 10.54% |

| Training and development | 18.29% | 7.62% | 4% | 10.86% | 20.57% | 6.1% | 15.43% | 9.52% | 7.62% |

| Technology factors | 22.07% | 10.71% | 11.72% | 12.29% | 8.07% | 7.93% | 6.25% | 10.57% | 10.4% |

| Compatibility | 16.26% | 21.54% | 10.16% | 0% | 9.35% | 3.66% | 26.02% | 8.54% | 4.47% |

| Complexity | 9.12% | 20.85% | 14.33% | 9.12% | 11.73% | 14.66% | 15.31% | 4.89% | 0% |

| Employees’ resistance | 14.94% | 20.12% | 17.84% | 19.09% | 7.88% | 5.19% | 7.88% | 7.05% | 0% |

| Future technology | 23.62% | 20.09% | 7.95% | 9.05% | 8.39% | 16.56% | 5.52% | 6.62% | 2.21% |

| Technology advantages | 32.28% | 2.11% | 13.18% | 14.76% | 10.41% | 5.67% | 4.61% | 3.69% | 13.31% |

| SC performance | 9.33% | 18.48% | 23.43% | 5.71% | 7.62% | 12.57% | 8.95% | 6.48% | 7.43% |

| Current traceability technologies | 20.51% | 5.9% | 9.2% | 10.32% | 6.59% | 6.96% | 3.92% | 18.46% | 18.15% |

| Traceability technologies adoption motivation | 33.8% | 7.18% | 16.2% | 17.13% | 3.94% | 5.09% | 8.33% | 3.7% | 4.63% |

| COVID-19 | 21.73% | 8.25% | 14.08% | 10.26% | 9.96% | 12.37% | 5.23% | 2.31% | 15.79% |

| TOE factors | Main Theme | Subtheme 1 | Subtheme 2 | Subtheme 3 | Subtheme 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technology | Existence of traceability technologies in Saudi dairy sector (p1,p2,p3,p4,p5,p8) | - | - | - | - |

| Technology and organisation | Traceability technology adoption challenges and barriers (p1,p2, p3, p6, p8,p9). | Employee’s Resistance (P2,P6,P3) | Compatibility Considerations (P2,P4,P6,P7) |

Complexity in the Adoption Process (P6,P1,P7,P2,P3) |

- |

| Organisation | Role of organisational culture and top management support in the adoption process (p2,p3,p6). | Role of Organisational Culture(P2, P6) | Role of Top Management Support (P3,P2,P6) | - | - |

| Technology and organisation | Impact of food traceability technologies on supply chain performance (p1,p2,p3,p4,p5,p6,p7,p8,p9) | Efficiency: Cost, Profit, Time, Effort (P1,P2,P3,P5,P7,P8) |

Flexibility (P5) | Food Quality (P1,P2,P5) | Transparency, Information Availability, and Accuracy(P7) |

| Environment | Impact of covid-19 and post-covid-19 period on technology investment (p1,p2,p3,p5,p7,p8) | - | - | - | - |

| Environment | Impact of consumer pressure on food traceability technology adoption. (p1,p2,p3,p9) |

Consumer Awareness (P2) | - | - | - |

| Environment | Influence of competitor pressure (p1,p2,p3,p4,p5,p6, p7,p8,p8) | - | - | - | - |

| Environment, technology | Role of Government Policy in Influencing FTT Adoption(P1,P2,P3,P4,P7,P8) | Vision 2030 Initiative (P1,P2,P3) | Technology Investment (P1,P4,P7,P8) | - | - |

| Organisation | Importance of Employee Training in Technology Adoption (P1,P2,P4) | - | - | - | - |

| Environment | Workforce localisation initiative (Saudization) (P1,P2P6,P9) | - | - | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).