1. Introduction

Large Language Models (LLMs) are rapidly transitioning from research laboratories to become integral components of enterprise workflows, powering applications ranging from multilingual information retrieval systems to sophisticated corporate chatbots. Their capacity to process and generate human-like text across various languages holds immense potential for enhancing productivity and streamlining operations within global organizations. However, alongside this transformative power comes a critical concern: the potential for inherent biases within these models to generate inequitable or skewed outcomes [

41,

51].

While prior research has extensively cataloged various forms of bias in NLP systems, often focusing on singular bias types or employing controlled, monolingual settings [

41,

50], a comprehensive understanding of the multi-dimensional biases exhibited by LLMs in real-world, multilingual enterprise environments remains a significant challenge. As LLMs are increasingly deployed as decision influencers within workplaces, the need to rigorously evaluate and mitigate these biases across different operational facets becomes paramount [

48].

This study addresses this gap by providing a systematic empirical evaluation of four key bias dimensions prevalent in LLM-powered corporate chatbots: retrieval bias (encompassing recency, language, grammar, and length preferences) [

37], reinforcement bias (investigated through response drift over repeated queries), hallucination bias (the tendency to generate factually incorrect information) [

28], and language bias (differential processing of semantically equivalent queries in different languages) [

50].

Unlike existing work, our investigation leverages real-world multilingual corporate documents and over 250 targeted user queries to assess the intertwined nature of these biases in a genuine workplace context. Through a controlled Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) pipeline and robust statistical analyses on five prominent LLMs (GPT-4, Claude, Cohere, Mistral, and DeepSeek), we aim to uncover complex, model-specific bias patterns that can significantly impact fair knowledge access and equitable outcomes within global organizations.

The findings of this study reveal distinct and complex multi-dimensional bias patterns across the evaluated LLMs when operating in a multilingual enterprise context. This empirical comparison highlights the nuanced ways different models manifest biases in retrieval, reinforcement, hallucination, and language processing. The observed variations in bias profiles across these prominent models underscore the critical need for enterprises to perform rigorous, context-specific evaluations before deploying LLMs, particularly in multilingual settings where biases can compound or interact unexpectedly. By empirically evaluating and comparing the multi-faceted biases of prominent LLMs in a realistic enterprise setting, this work provides crucial insights for organizations seeking to deploy AI globally, ensuring knowledge systems remain accessible and trustworthy across diverse user populations.

2. Related Work

The increasing deployment of Large Language Models (LLMs) in enterprise settings has spurred significant research into their capabilities and limitations [

41]. A critical area of investigation focuses on the inherent biases that these models may exhibit, potentially leading to unfair or inconsistent outcomes across various natural language processing (NLP) tasks [

41]. Prior work has extensively explored different facets of bias in NLP and LLMs, including biases stemming from training data, such as gender and racial bias in text generation and sentiment analysis [

17,

18,

52].

In the context of Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) systems, "retrieval bias" can occur in several forms. It can manifest as a preference for newer content ("retrieval recency bias"). It can also occur when the LLM disproportionately favors certain documents or viewpoints during the retrieval process, leading to skewed information access [

32,

43]. Furthermore, "grammatical robustness" is a concern, as LLMs may deprioritize noisy text even when factually correct and relevant to information retrieval (as shown by findings that while LLMs generally maintain semantic sensitivity under noisy conditions, surface-level grammatical cues still influence their rankings). "Length bias" is also relevant, where LLMs might favor longer documents regardless of content quality (with findings suggesting that most models show this bias, especially at the top ranks). Furthermore, a critical aspect is "retrieval language bias," where LLMs exhibit systematic preferences for documents in certain languages over semantically equivalent documents in others. Studies have shown a consistent language hierarchy in LLM rerankers, with a strong preference for English at the top ranks [

23,

39].

The interaction between users and LLMs can also introduce or amplify biases. While Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF) aims to align LLMs with human preferences, the potential for "reinforcement bias" – where repeated interactions or specific feedback patterns lead to a drift in the model’s responses – demands careful examination [

21,

40]. Studies have shown that even state-of-the-art LLMs are not fully deterministic under repetition [

34].

The multilingual nature of global organizations introduces "language bias," where LLMs may exhibit performance disparities or varying responses based on the input language [

23,

30]. Prior research indicates that LLMs can exhibit a consistent internal language hierarchy when processing semantically equivalent queries in different languages, potentially due to training data imbalance, cross-lingual transfer limitations, and embedding space distortion [

16]. This can manifest as differences in the language of the response, as well as variations in metrics such as word count and lexical diversity. Understanding these language-specific behaviors is crucial for ensuring equitable access and effective communication across diverse user bases [

60].

Another significant concern is "hallucination bias," where LLMs generate plausible-sounding but factually incorrect information [

29]. The propensity for hallucination can vary across models and contexts, potentially leading to the dissemination of misinformation within enterprise environments [

27]. Evaluating the rate and nature of hallucinations is essential to ensure the reliability of LLM-powered chatbots [

13].

Unlike prior work that often focuses on singular bias types or employs static evaluations, this study provides a comprehensive empirical evaluation of four key bias dimensions-retrieval, reinforcement (investigated through repeated queries), language (investigated through identical queries in different languages), and hallucination in the context of real-world corporate documents and targeted user queries. Using a controlled RAG-based pipeline and robust statistical analysis, we systematically examine five prominent LLMs to uncover model-specific bias patterns that impact fairness, transparency, and trust in enterprise chatbot deployments. This work contributes to the field by offering a multi-dimensional framework for continuous bias auditing in AI-driven workplace assistants, addressing a critical need for ensuring responsible and equitable LLM integration in organizational settings [

34].

3. Methodology

Our experimental framework is designed to comprehensively evaluate multiple bias dimensions in LLM-powered corporate chatbots deployed within a multilingual enterprise environment. The evaluation is organized into four primary components: Retrieval Bias, Reinforcement Bias, Language Bias, and Hallucination Bias. Each component is addressed with a targeted dataset and experimental design, as described below.

3.1. Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) Pipeline

A Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) pipeline, orchestrated using the n8n automation platform (version 1.78.1) [

42], was implemented to retrieve and rank documents for the Retrieval Bias experiments. The n8n workflow comprised the following key steps:

Data Acquisition: Corporate documents were accessed from a Microsoft SharePoint site using the Microsoft Graph API. This involved an initial HTTP Request node to the SharePoint site, followed by subsequent requests and JavaScript code nodes to extract page content, including text and metadata.

Segmentation: The extracted text was segmented using the Recursive Character Text Splitter (LangChain node within n8n) [

19] with a chunk overlap of 10 characters to maintain contextual continuity. Text chunks were transformed into numerical vector representations using the OpenAI Embeddings model (LangChain node within n8n) [

44], specifically the text-embedding-3-large model. The generated embeddings, along with their corresponding text chunks and metadata, were stored in a Supabase Vector Store (LangChain node within n8n) [

56] for efficient similarity-based retrieval.

Retrieval Process: LLM queries were embedded using the same OpenAI Embeddings model. A similarity search was performed in the Supabase Vector Store to retrieve relevant document chunks. The retrieved chunks were provided as context to the LLM to generate a ranked list of documents.

Automation and Scheduling: The entire workflow was automated using n8n and scheduled to run periodically (frequency specified in the "Schedule Trigger" node) to ensure the vector store remained synchronized with updates to the SharePoint data source.

3.2. Dataset Creation and Augmentation

We began with the original company policy documents, which originally contained 66 pages related to company policies. After identifying and excluding 16 pages with missing content, we retained 50 original document rows. For each of these documents, we formulated a corresponding test query—covering topics such as accessing corporate systems, policy inquiries, and operational details.

To ensure the integrity and cultural relevance of our evaluations, all data augmentations were performed by human annotators.

Recency Bias: For every original document, three additional copies were manually created with identical content but with timestamps set from 0.5 to 5 years in the past. This approach ensured that only the temporal metadata varied, isolating the effect of recency on document retrieval.

Retrieval Language Bias: Documents were translated into four languages (English, French, Flemish/Dutch, and German) by professional translators. This manual translation process preserved semantic equivalency and accounted for cultural nuances, avoiding potential artifacts introduced by automated translation tools.

Retrieval Grammar Bias: Each document was duplicated into two versions—one containing intentional spelling and grammatical mistakes (e.g., ‘you will able to access’ (missing auxiliary verb), ‘the administrative documents has to be read’ (incorrect conjugation)), and one kept error-free. These modifications were introduced by human editors to simulate realistic grammatical or orthographical errors without altering the core content.

Retrieval Length Bias: Documents were categorized into short (<600 characters), medium (600–1300 characters), and long (>1300 characters) by manually editing the content to vary verbosity. Human editors ensured that the essential information remained consistent across versions, allowing for the assessment of length-based retrieval preferences.

3.3. Retrieval Bias

For the Retrieval Bias experiments, the RAG pipeline described in

Section 3.1 was used to retrieve and rank the manually augmented documents. The LLMs (GPT-4o [

44], Claude 3 Sonnet [

14], Mistral Large [

12], Cohere Command A [

9], and DeepSeek-V3 [

10]), hereafter referenced as GPT, Claude, Mistral, Cohere and Deepseek respectively, were tasked with ranking the available documents based solely on relevance, as determined by the RAG pipeline. The ranking was extracted from the LLM’s output using a regular expression. We statistically evaluated the ranking variations using Chi-Square tests [

25] and visualized the outcomes (e.g., bar charts, ranking distribution plots) to determine if metadata variations systematically influenced document ranking.

3.4. Reinforcement Bias

To assess reinforcement bias, we selected 10 representative queries and asked each LLM to respond 50 times. We computed pairwise drift scores between consecutive responses using TF-IDF vectors generated with the scikit-learn library (version 1.6.1) [

46], with default parameters, and cosine similarity calculated using the standard formula. This generated a quantifiable drift metric that measures semantic divergence over repeated submissions. Human evaluators rated each set of 50 responses for each query. Evaluators assessed consistency based on a Likert scale of 1 to 5, where 1 indicated low inconsistency and 5 indicated high consistency. Evaluators also provided qualitative feedback on any observed changes in tone, focus, or factual accuracy.

The drift analysis was implemented as follows: for each base question, responses were grouped by LLM and ordered by repetition number. Drift between consecutive responses was calculated using the TF-IDF vectorizer and cosine similarity from scikit-learn [

46]. The resulting drift scores were aggregated for statistical analysis. To compare drift distributions across LLMs, we performed an ANOVA test using SciPy [

57], and, if significant, conducted post-hoc pairwise comparisons using Tukey’s HSD from statsmodels [

54].

3.5. Language Bias

For the Language Bias experiment, identical queries were formulated in four languages (English, French, Dutch, and German) regardless of the source document’s original language. We analyzed outputs in terms of response lengths and lexical diversity. Response length was measured in word count was determined using a tokenizer from the NLTK library (version 3.9.1) [

15]. Mann-Whitney U tests were performed to detect statistically significant differences among language outputs [

38], and human evaluators assessed the responses for each language in terms of clarity, output language, completeness, and cultural appropriateness using a rubric with specific criteria.

3.6. Hallucination Bias

To evaluate hallucination bias, we utilized the set of 50 vague or ambiguous questions developed by our experts. Each model’s response to these queries was collected and subsequently compared against verified company documents. Human evaluators were tasked with scoring each response based on its factual accuracy and identifying instances where the model fabricated or exaggerated information [

29]. The hallucination rate was computed as the percentage of responses containing unverifiable or fabricated content, and the confidence-accuracy mismatch was further analyzed to evaluate the reliability of the outputs [

13].

4. Results

4.1. Retrieval Bias

4.1.1. Retrieval Recency Bias

To assess recency bias, LLMs re-ranked four identical documents differing only in timestamps (newest, newer, older, oldest) without temporal cues in the prompt (see

Section 3.3).

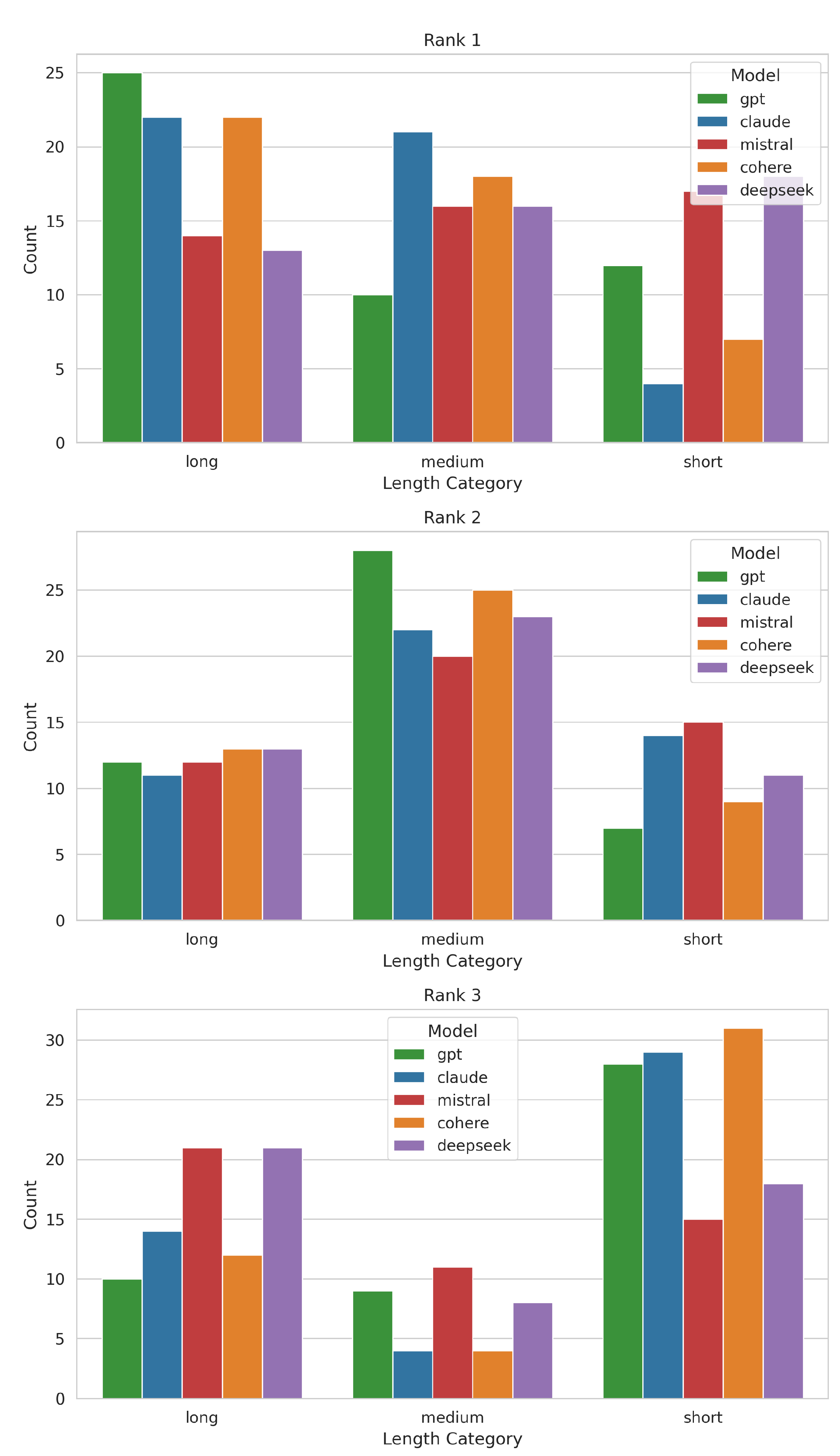

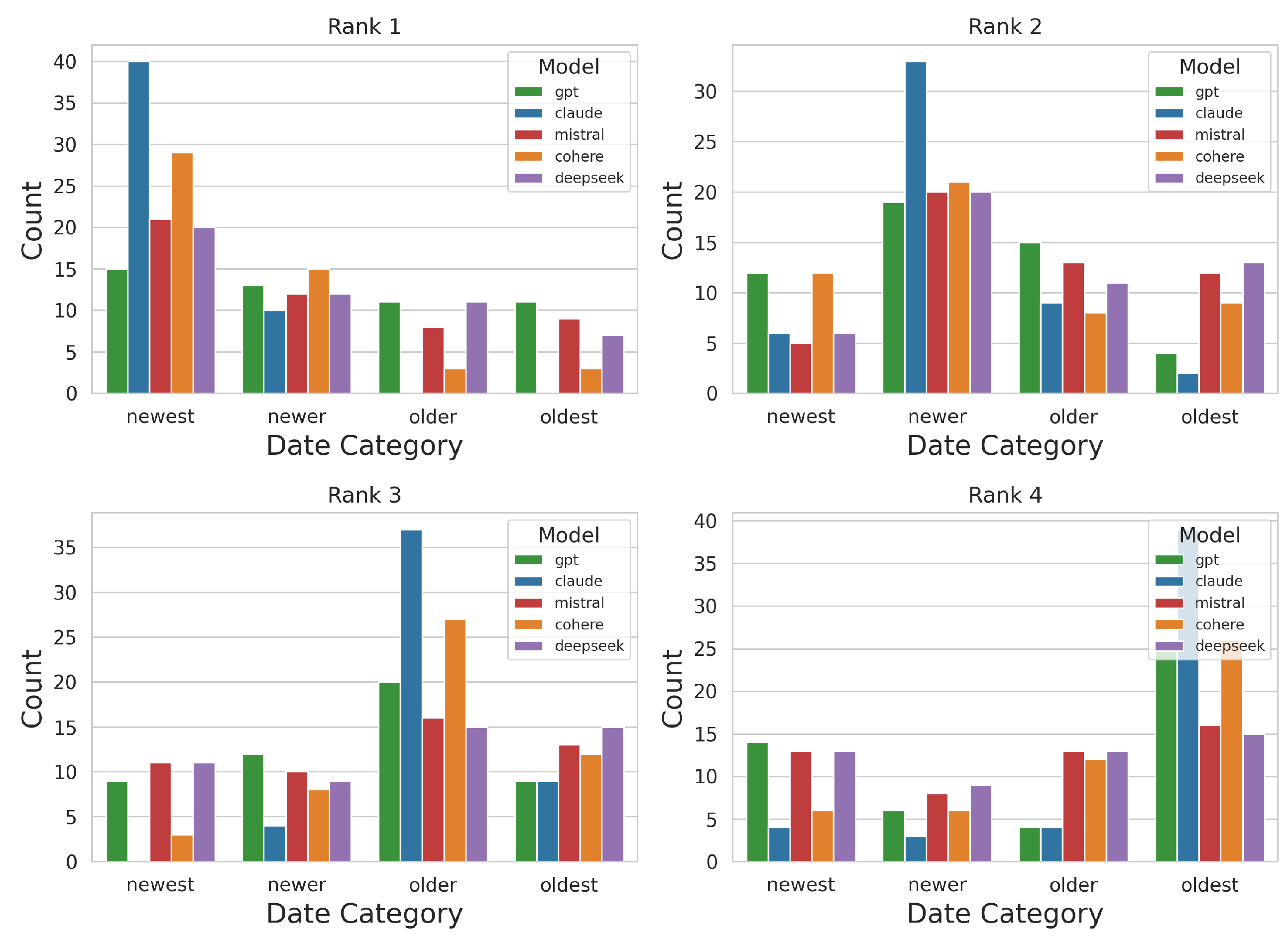

Figure 1 shows the distribution of date categories across top-4 ranks for each model.

Claude strongly favored “newest” at Rank 1 (80% of trials), while GPT and Cohere showed weaker recency preference; Mistral and DeepSeek were the most balanced. At lower ranks, older document selection increased across all models.

Retrieval performance metrics (Accuracy, MAE, and Cohen’s Kappa) are summarized in Table S1 (supplementary). Claude achieved the highest accuracy and agreement, suggesting effective prioritization of recency-aligned relevance [

22,

58]. In contrast, GPT and DeepSeek had lower accuracy and higher MAE [

58]. A chi-square test (

,

,

) confirmed significant differences among models [

45]. Confusion matrix analysis showed Claude maintained higher F1, precision, and recall across temporal categories, while GPT and DeepSeek often misclassified older documents as recent [

49].

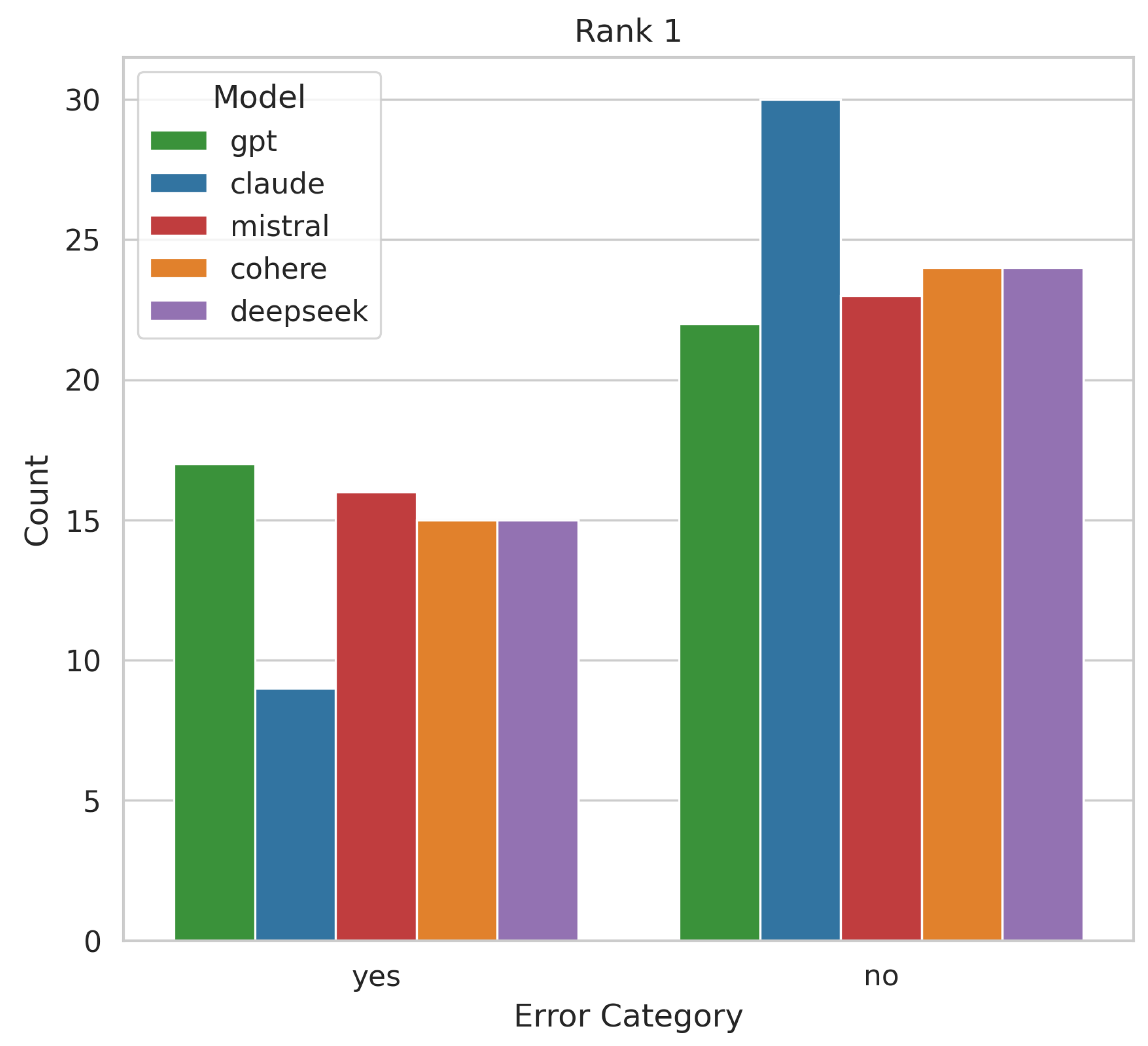

4.1.2. Retrieval Grammar Bias

Real-world documents often include orthographic and grammatical variations. While semantically irrelevant, such noise can affect LLM relevance judgments. We examined model response to grammatical errors using Accuracy, MAE, and Cohen’s Kappa across clean vs. noisy input variants [

22,

58].

Claude showed the strongest preference for clean text (Accuracy: 76.92%,

); GPT was most indifferent (Accuracy: 56.41%,

). Cohere and DeepSeek fell in between. Confusion matrix metrics confirmed Claude’s distinct preference pattern across clean and noisy inputs (F1: 0.77). A chi-square test on top-rank outputs (

,

,

) found no statistically significant differences.

Figure 2 visualizes document error category distribution at top rank per model.

Claude exhibited a stronger preference for grammatically clean documents at Rank 1, while other models showed more balance.

4.1.3. Retrieval Length Bias

Length bias refers to disproportionate preference for longer documents. Using semantically equivalent documents of varying lengths (long, medium, short), we evaluated length preferences across models (

Section 3.3).

At Rank 1, GPT, Claude, and Cohere preferred longer documents; Mistral was balanced; DeepSeek was evenly distributed. At Rank 3, all models shifted toward shorter selections. Chi-square results [

45] (

Table S4, Supplementary) revealed significant associations at Rank 1 (

,

) and Rank 3 (

,

), indicating model-specific biases. No significant difference was found at Rank 2 (

).

Figure 3.

Document length distribution across top-3 ranks.

Figure 3.

Document length distribution across top-3 ranks.

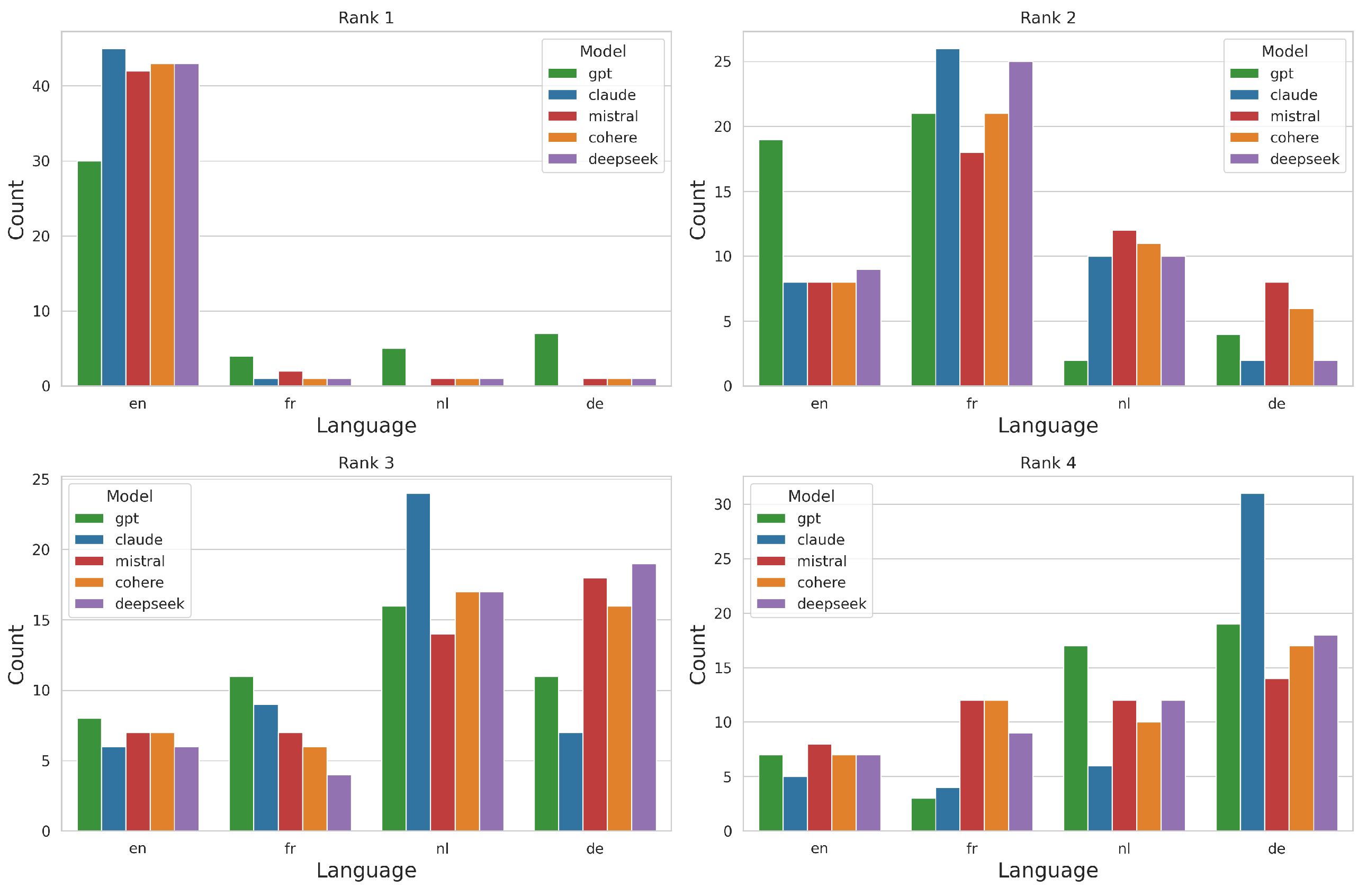

4.1.4. Retrieval Language Bias

To assess multilingual fairness, models re-ranked equivalent documents in English, French, Dutch, and German (

Section 3.3).

Figure 4 shows language preferences across top-4 ranks.

All models preferred English at Rank 1, with Claude and DeepSeek leading. Subsequent ranks showed a consistent shift: French (Rank 2), Dutch (Rank 3), and German (Rank 4), especially pronounced in Claude.

Chi-square results [

45] confirmed significant associations between model and language at Ranks 1 (

), 2 (

), and 4 (

). No significant association was observed at Rank 3 (

), suggesting relative consistency across models at that position.

4.2. Reinforcement Bias

A reliable chatbot should exhibit consistent behavior when presented with identical queries over time. However, LLMs, being inherently stochastic systems, may be susceptible to

reinforcement bias - a phenomenon characterized by response drift, where outputs gradually shift across repeated exposures to the same prompt [

21,

41]. This subtle form of instability can have significant implications for the reproducibility and reliability of LLM-based systems, particularly in user-facing or regulatory-sensitive applications such as legal search and medical question answering [

17,

52]. Therefore, understanding and quantifying this drift is crucial for ensuring the robustness and trustworthiness of LLM chatbots in real-world deployments.

We analyzed semantic drift across 50 responses to 10 repeatedly presented prompts for all five LLMs. Using a TF-IDF/cosine similarity-based metric computed with scikit-learn [

46], we calculated pairwise drift scores for each repetition sequence. A one-way ANOVA showed a statistically significant effect of model type on drift (

F = 15.12,

0.0001) [

57]. Tukey’s HSD test further identified model pairs with significant differences in mean drift scores [

54]. Full results are provided in the Supplementary Materials (Table S6).

Notably, Cohere exhibited significantly higher average drift than Claude, GPT, and Mistral. Claude showed significantly lower drift than GPT. DeepSeek and Mistral had intermediate drift, not significantly different from Claude or GPT. These findings suggest that some LLMs are more prone to semantic variation than others under repeated identical queries.

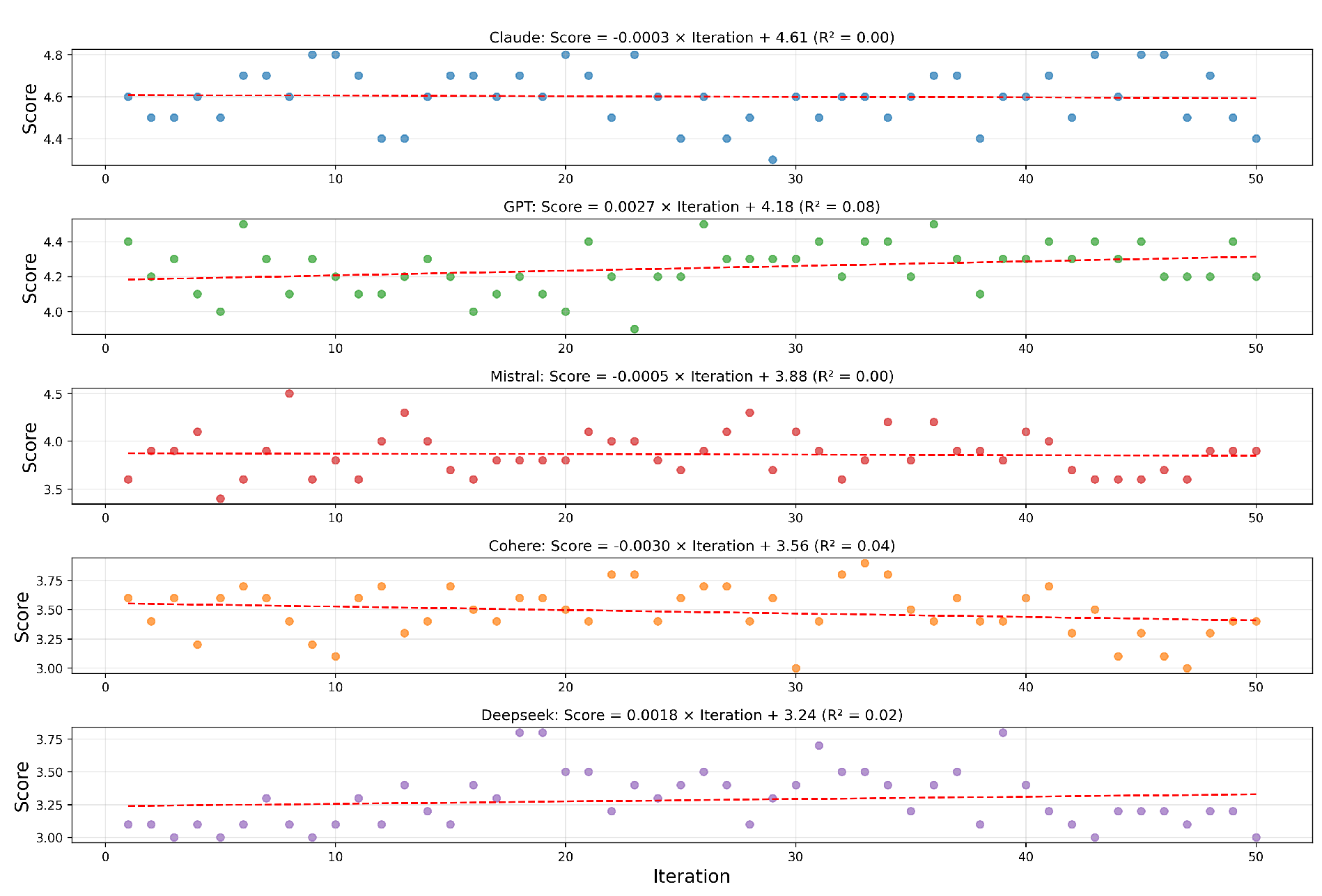

To assess whether these drift patterns were noticeable or impactful to humans, we conducted a parallel human evaluation. Human raters scored response quality over 50 repetitions for each model using a 1–5 scale, considering relevance, completeness, and tone stability.

Figure 5 shows that average scores remained mostly stable across iterations for all models. While Cohere and Mistral showed more fluctuation, no model displayed a steady downward trend in quality.

Regression and Kendall’s Tau analyses (Table S7, supplementary material) found no statistically significant trends across repetitions (

), confirming visual impressions of temporal stability [

31].

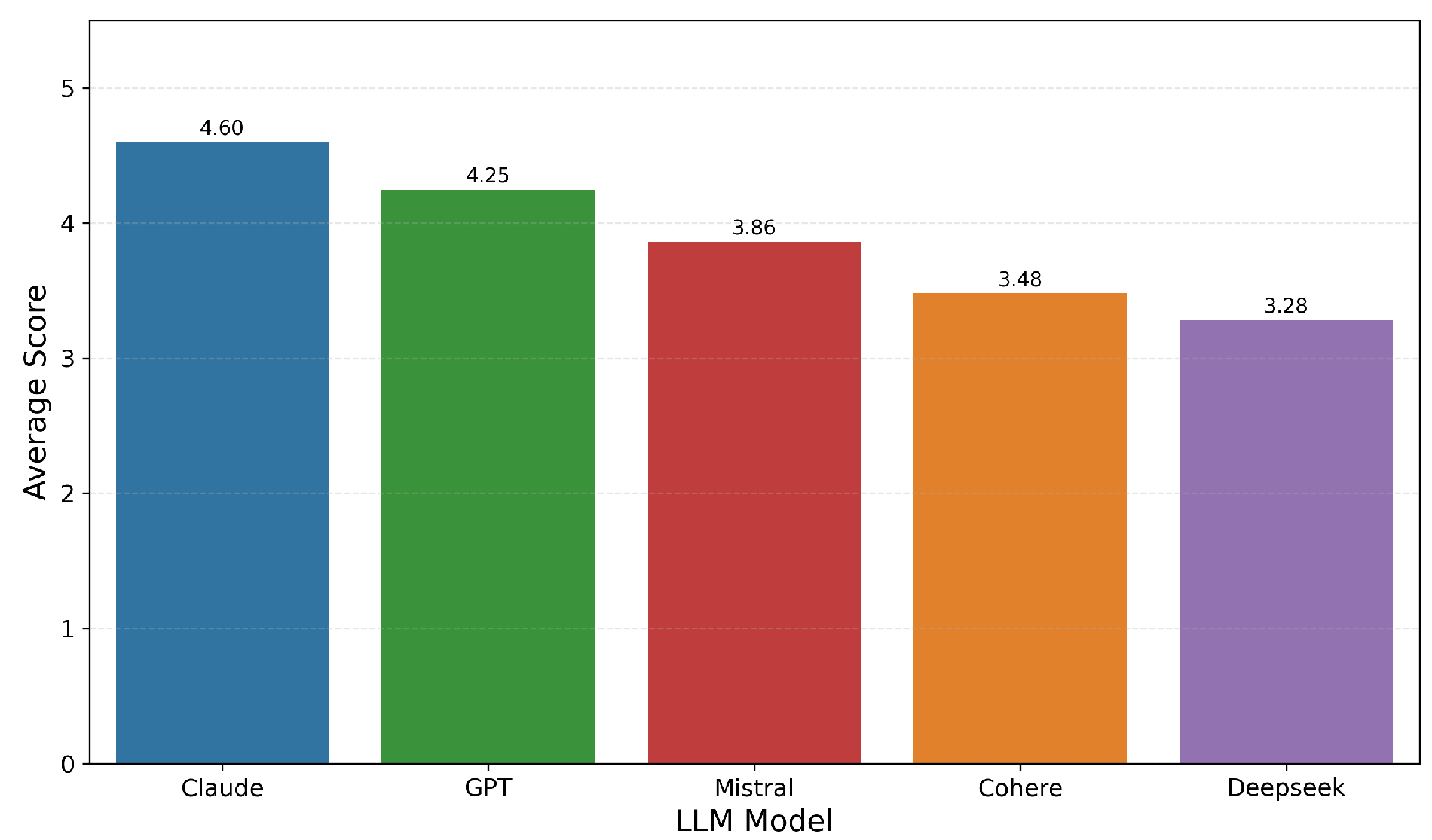

As shown in

Figure 6, average quality scores differed by model. Claude ranked highest (4.60), followed by GPT (4.25). Mistral, Cohere, and DeepSeek scored lower, at 3.86, 3.48, and 3.28, respectively.

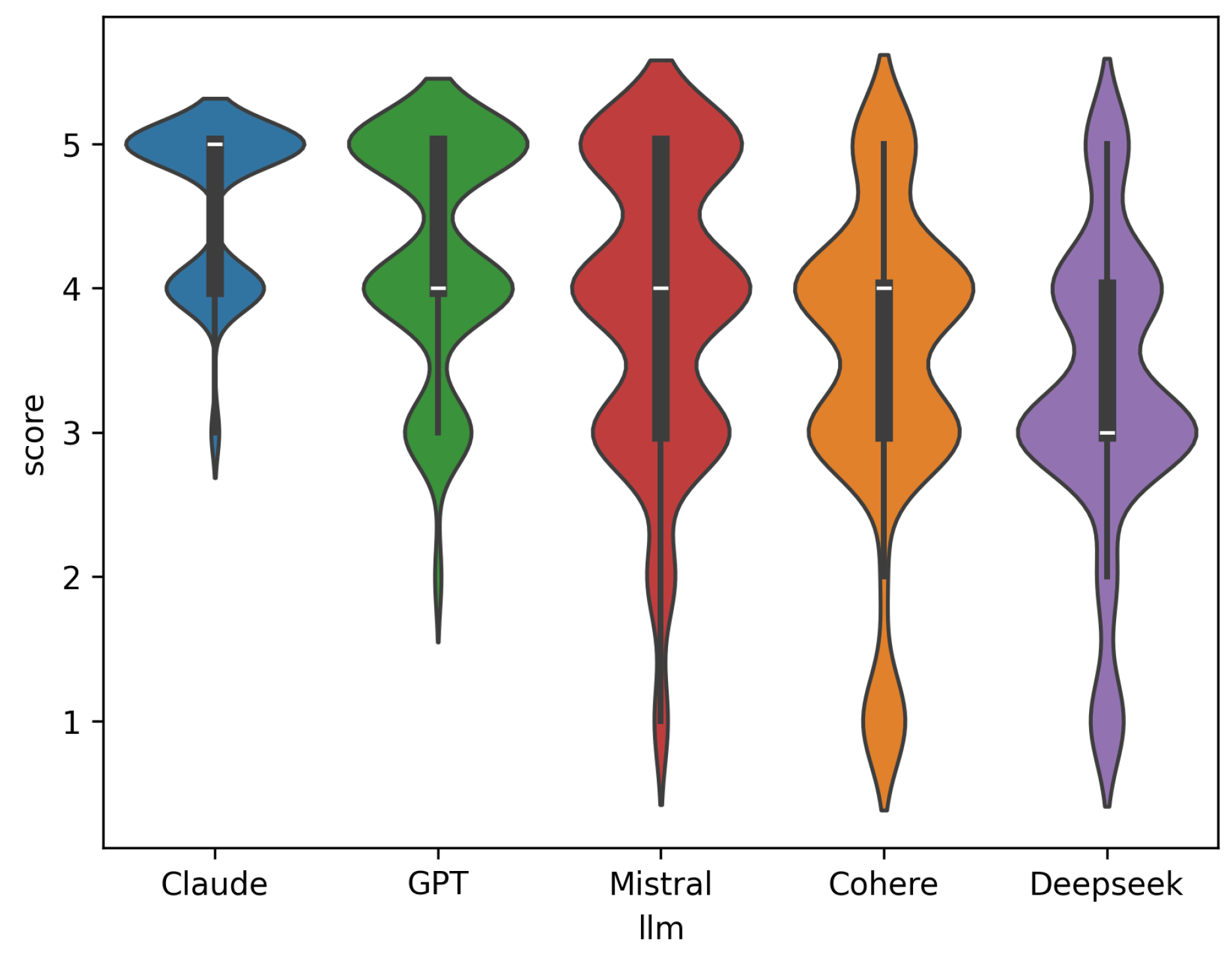

Score variability (

Figure 7) reinforces these differences: Claude responses were consistently rated highly, while Cohere and DeepSeek showed wider distribution and lower medians.

In sum, while semantic drift is detectable computationally, its perceptual impact over 50 repetitions appears limited. However, differences in mean scores and variability indicate that models like Claude and GPT maintain more consistent quality, reinforcing their robustness in repeated-query contexts. Full pairwise drift statistics are available in Table S6 of Supplementary Materials.

4.3. Language Bias

The widespread use of multilingual LLMs necessitates robust evaluation of their linguistic consistency and fairness [

16,

23,

30]. Ideally, LLMs should perform uniformly across languages, particularly for semantically equivalent prompts. However, uneven training data and multilingual modeling challenges can introduce "language bias"-systematic output differences based solely on the response language [

16,

41]. These disparities may affect quality, tone, and verbosity, with ethical and UX implications in sensitive domains such as education, healthcare, and global customer service.

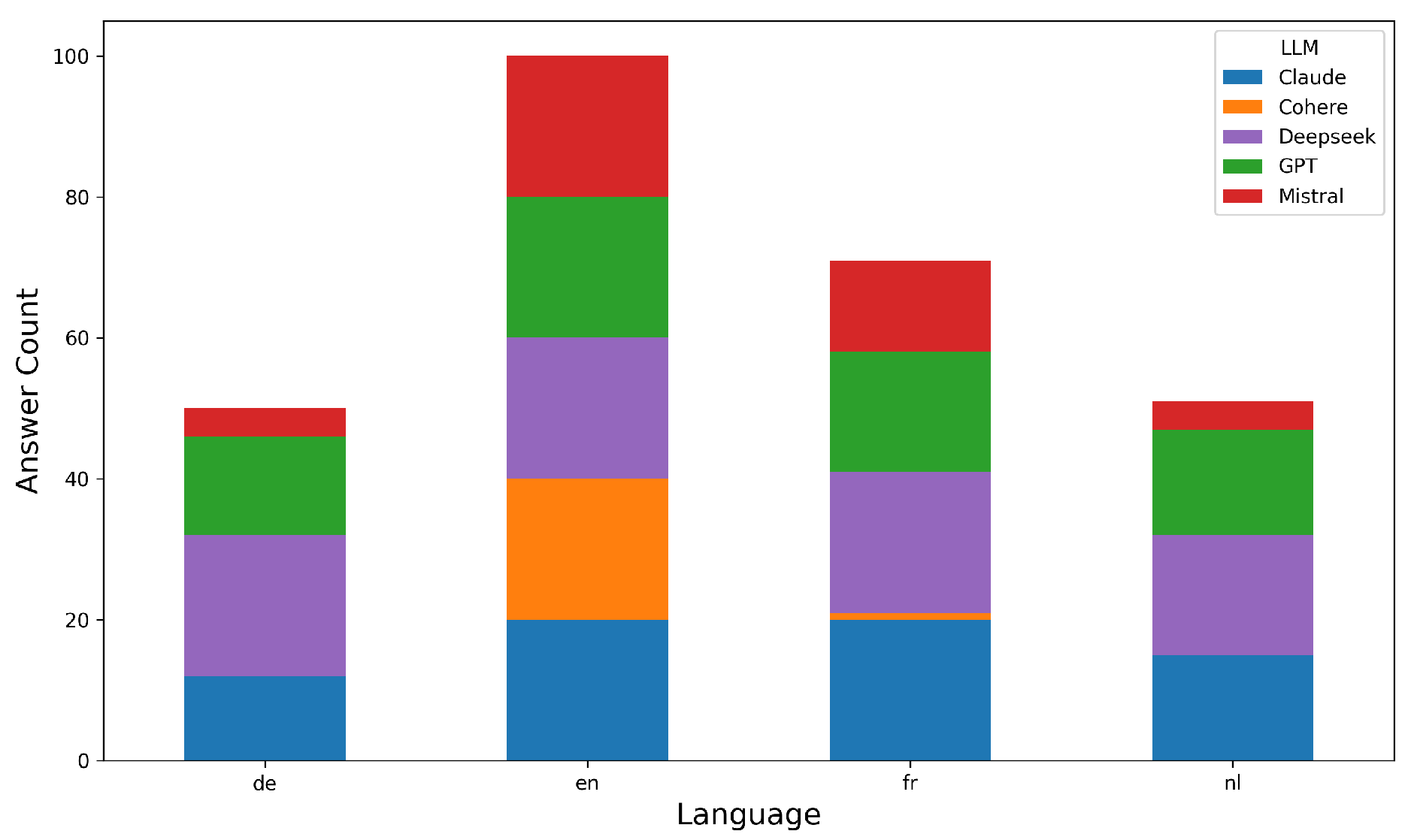

This study investigates the language adherence behavior of all five LLMs across four languages: English (en), French (fr), Dutch (nl), and German (de). For each model, we analyzed responses to 20 prompts per language and measured whether replies matched the prompt language.

As shown in

Figure 8, adherence varied widely: DeepSeek (96.25%), Claude (83.75%), GPT (82.50%), Mistral (51.25%), and Cohere (26.25%). All models consistently maintained English responses, but significant variation across other languages was observed for all except GPT (

,

). Cohere (

,

) and Mistral (

,

) showed the strongest divergence. Claude (

,

) and DeepSeek (

,

) exhibited smaller but significant variation. See Tables S8–9 in the Supplementary Material for detailed statistics [

45].

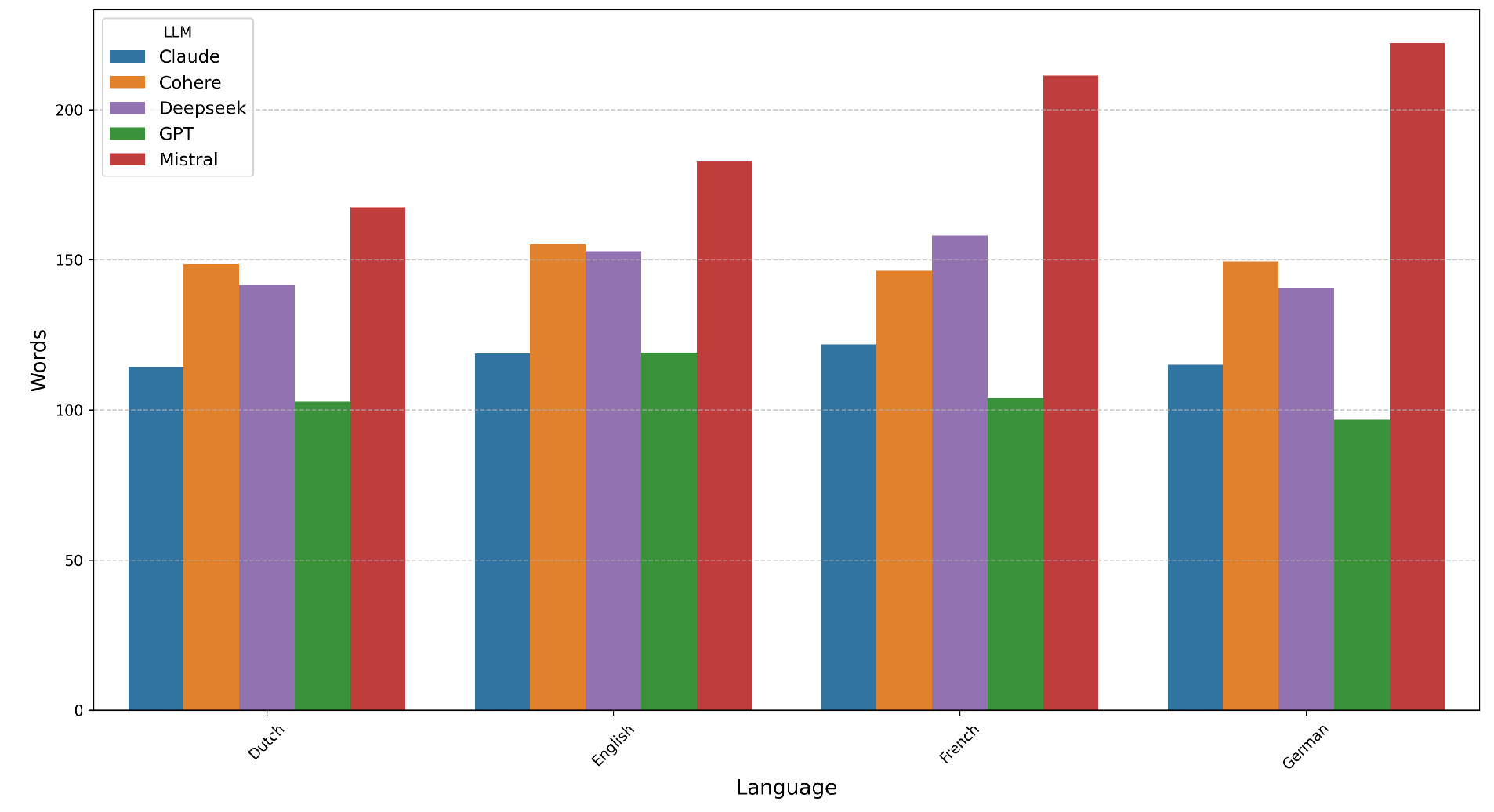

We also analyzed response verbosity (

Figure 9). Mistral produced the longest outputs across all languages, especially for French and German. GPT generated the shortest, while Claude, Cohere, and DeepSeek fell between, with average lengths of 115–160 words.

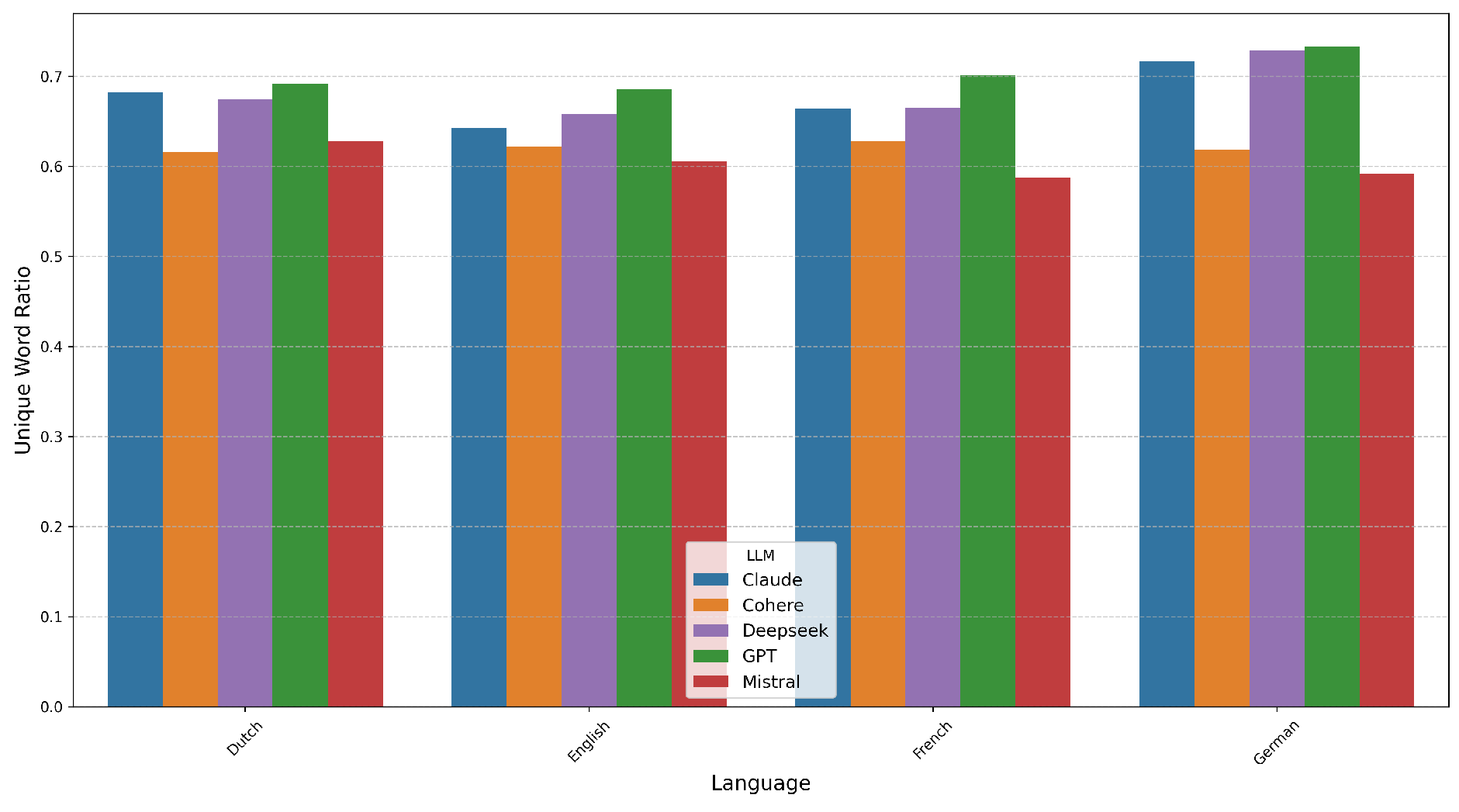

Lexical diversity was evaluated using the Unique Word Ratio (UWR), defined as the number of unique words divided by total word count (

Figure 10). GPT, DeepSeek, and Claude achieved the highest diversity (typically

), especially in German and French. Cohere and Mistral had the lowest diversity (

). Notably, verbosity did not predict diversity: Mistral’s long outputs had low UWR, while GPT’s concise responses maintained high diversity. Word counts and tokenization were performed using the NLTK library [

15].

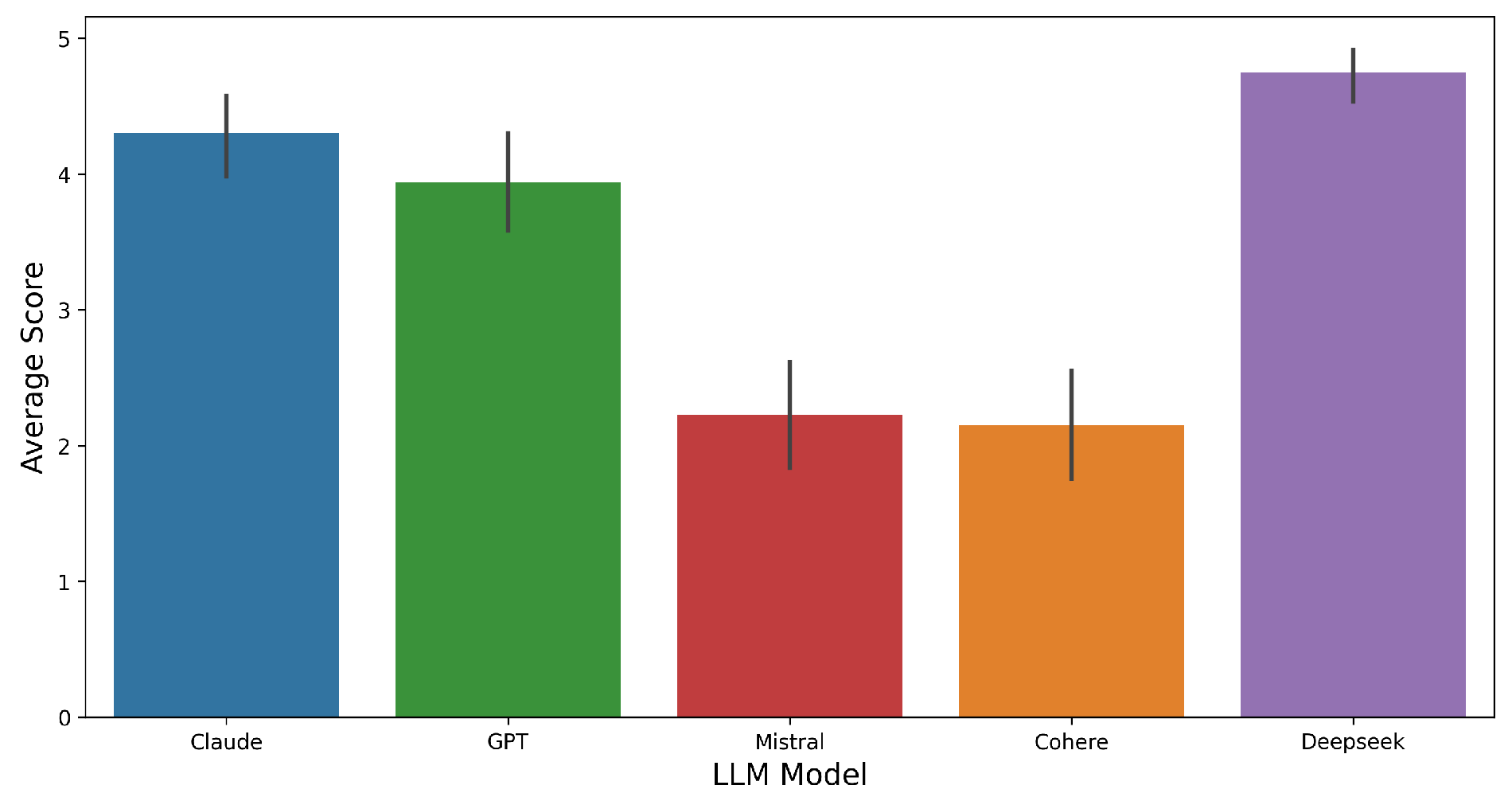

To complement quantitative metrics, we conducted a human evaluation of the generated responses.

Figure 11 presents the average scores (1–5 scale) assigned by human raters across models. DeepSeek received the highest overall rating (

), indicating strong perceived response quality. Claude and GPT also performed well, with averages around 4.3 and 3.95, respectively. Mistral (

) and Cohere (

) were rated significantly lower.

These subjective assessments corroborate earlier findings: models with high language adherence and lexical diversity (e.g., DeepSeek, Claude) tend to be rated more favorably, while models that diverged from the prompt language or produced verbose yet less diverse outputs (e.g., Mistral) received lower scores. The alignment between quantitative indicators and human judgments strengthens the validity of our evaluation framework.

4.4. Hallucination Bias

To evaluate hallucination bias, we utilized a set of 50 vague or ambiguous questions. The responses were compared against verified company documents, and human evaluators identified instances of fabricated or exaggerated information [

13,

29].

Contrary to the expectation that ambiguous prompts might elicit hallucinations, our analysis revealed that none of the evaluated large language models exhibited any instances of hallucination in their responses to the 50 ambiguous questions. All information provided was verifiable against the company documents, resulting in a 0% hallucination rate across all models. Consequently, an analysis of confidence-accuracy mismatch was not applicable. This finding suggests that for the specific type of ambiguous queries and the provided knowledge source, these models demonstrated a strong ability to avoid generating unverified information.

5. Discussions

We observed distinct biases across the systems. Claude’s outputs heavily favored recently retrieved passages (a strong recency effect), paralleling known primacy/recency biases in long-context models [

33,

36]. This aligns with findings that LLMs tend to focus on the start and end of long documents, potentially overlooking information in the middle [

3]. Claude was also sensitive to minor perturbations such as grammatical errors, suggesting that information might be undervalued due to textual errors. [

20,

35]. This finding calls for caution, especially considering the employment of LLMs in environments where information should be treated irrespective of its linguistic quality. In contrast to Claude, both GPT and Cohere displayed more indifference when confronted with irregularities such as typos or grammatical errors. However, the same models exhibited higher instability when repeated queries were presented, reflecting that such small input noise can degrade LLM performance [

26,

47]. This instability can manifest as output drift over repeated queries [

5]. DeepSeek’s retriever maintained high fidelity to the query language (minimal cross-language drift) [

11,

59] but showed variable semantic drift: it sometimes returned topically related but semantically off-target documents [

6,

20]. This might be due to DeepSeek being primarily designed as a reasoning engine rather than for generating embeddings for retrieval [

20]. All systems performed best on English documents; in our tests, French, Dutch, and German queries yielded significantly lower accuracy, consistent with prior evidence that LLMs often underperform on lower-resource languages [

30]. This English-centric behavior is observed even in multilingual LLMs, where internal processing often occurs in a representation space closer to English [

24,

53].

Crucially, we did not observe any hallucinated outputs. Because our pipeline grounded generation in retrieved documents (a retrieval-augmented setup), answers were always based on provided content. This aligns with reports that RAG architectures substantially reduce hallucinations and improve factual accuracy [

29,

55]. RAG ensures that the model has access to accurate and up-to-date information, reducing the likelihood of generating incorrect or outdated content [

1,

7,

8]. These findings have important implications for enterprise deployment. A strong recency bias means that knowledge management systems should explicitly index and surface older but relevant documents to avoid favoring only recent information [

3]. Grammar-sensitive models like Claude suggest the need for input sanitization or correction to accommodate varied writing styles [

35]. The fragility of LLMs to noise highlights the importance of robust prompt engineering and output validation in mission-critical applications [

2,

4]. The English-language preference implies that global deployments cannot assume equal performance across languages; practitioners should verify LLM accuracy for each target language or employ multilingual retrieval strategies [

30]. Importantly, the absence of hallucinations under RAG grounding demonstrates the benefit of integrating retrieval: grounding answers in real documents drastically improves factual reliability [

8,

55]. Consistent with our observations, recent work stresses that deploying RAG-based LLMs at scale requires strong governance (e.g., modular design, continuous evaluation) to detect and mitigate biases or misinformation [

34,

41].

Our study has several limitations. We relied on synthetic documents and controlled prompt variants to isolate specific biases, which may not capture the full complexity of real-world enterprise data or adversarial queries. We focused on a narrow domain (enterprise knowledge bases) and a few languages, so our findings may not generalize to other sectors or truly low-resource settings. We also evaluated only particular commercial models; different architectures or fine-tunings might exhibit different bias patterns. These constraints suggest caution in extrapolating our results beyond the tested conditions.

Future work should address these gaps.

Multilingual bias mitigation:Developing retrieval or training methods (e.g., language-agnostic embeddings or fairness-aware reranking) can help equalize performance across languages [

59]. Techniques like cross-lingual debiasing have shown promise in reducing bias across languages.

Drift detection tools: Implementing monitoring that measures semantic consistency between queries and retrieved documents over time could flag when the model starts diverging from intended topics [

34]. Public dashboards are being developed to track model drift over time, providing valuable insights into the stability of LLMs.

Realistic evaluation: Extending this analysis to live enterprise traffic and additional low-resource languages will verify whether the observed biases persist in practice and will refine guidelines for robust deployment. Further research could also explore the impact of different RAG configurations and knowledge sources on mitigating these biases [

29,

55].

6. Conclusion

Based on the analysis of the bias profiles of the five evaluated LLMs, the following conclusions and recommendations can be made for enterprises considering their deployment:

Claude: Its strong recency preference makes it potentially suitable for applications where the most up-to-date information is critical, and where the quality of input (grammar) can be controlled or is generally high. However, it might be less ideal for scenarios that require accessing older information or processing noisy user input. GPT-4: While highly capable, its susceptibility to output drift under repeated queries necessitates careful management for applications involving multiple interactions. The observed language bias also needs to be taken into account for multilingual deployments. Cohere: Its lower adherence to non-English prompt languages makes it less suitable for multilingual applications requiring strict language matching. It is also prone to output drift, which should be considered for consistency-critical use cases. Mistral: Offers a balanced approach to recency in retrieval, which can be advantageous in many scenarios. However, its limitations in language adherence for multilingual applications need to be addressed through careful evaluation and potential fine-tuning. DeepSeek: Emerges as a strong candidate for multilingual enterprise environments due to its high fidelity to the query language and balanced recency preference. While some language bias was still observed, it appears to be less pronounced compared to other models.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their gratitude to DT Services and Consulting SRL for funding this project.

References

- Reducing hallucinations in large language models with custom intervention using amazon bedrock agents | aws machine learning blog. AWS Machine Learning Blog, Nov 2024.

- Understanding and mitigating bias in large language models (llms). DataCamp Blog, Jan 2024.

- Ai’s recency bias problem - the neuron. The Neuron, Aug 2024.

- Ensuring consistent llm outputs using structured prompts. Ubiai Tools Blog, 2024.

- Does anyone know why instruction precision degrades over time? - gpt builders. OpenAI Developer Community, Apr 2025.

- Deepseek r1 semantic relevance issues. GitHub Issue, Mar 2025.

- Reducing llm hallucinations using retrieval augmented generation (rag). Digital Alpha Blog, Jan 2025.

- Rag hallucination: What is it and how to avoid it. K2View Blog, Apr 2025.

- C. AI. Command a: An enterprise-ready large language model, 2025a. URL https://cohere.com/research/papers/command-a-an-enterprise-ready-family-of-large-language-models-2025-03-27. Technical report.

- D. AI. Deepseek-v3 technical report, 2024a. URL https://deepseek.com/blog/deepseek-v3-release. Unpublished technical documentation.

- D. AI. Deepseek r1. 2025b.

- M. AI. Mixtral 8x22b and mistral large models, 2024b. URL https://mistral.ai/news/.

- An, H.; Li, Z.; Zhao, J.; Rudinger, R. Sodapop: Open-ended discovery of social biases in social commonsense reasoning models. In Proceedings of the 17th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics; 2023; pp. 1573–1596. [Google Scholar]

- Anthropic. Claude 3 model family, 2023. URL https://www.anthropic.com/news/claude-3-family.

- Bird, S.; Klein, E.; Loper, E. Natural Language Processing with Python; O’Reilly Media, Inc., 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Blodgett, S.L.; Barocas, S.; Daumé, H., III; Wallach, H. Language (technology) is power: A critical survey of "bias" in nlp. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; 2020; pp. 5454–5476. [Google Scholar]

- Bolukbasi, T.; Chang, K.-W.; Zou, J.; Saligrama, V.; Kalai, A. Man is to computer programmer as woman is to homemaker? In debiasing word embeddings. In Proceedings of the 30th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems; 2016; pp. 4356–4364. [Google Scholar]

- Caliskan, A.; Bryson, J.J.; Narayanan, A. Semantics derived automatically from language corpora contain human-like biases. Science 2017, 356, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chase, H. Langchain: Framework for llm applications, 2023. URL https://www.langchain.com.

- Chen, K.E. Using deepseek r1 for rag: Do’s and don’ts. SkyPilot Blog, Feb 2025.

- Christiano, P.; Amodei, D.; Brown, T.B.; Clark, J.; McCandlish, S.; Leike, J. Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2023, 24, 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1960, 20, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conneau, A.; Rinott, R.; Lample, G.; Williams, A.; Bowman, S.R.; Schwenk, H.; Stoyanov, V. Xnli: Evaluating cross-lingual sentence representations. In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; 2018; pp. 2475–2485. [Google Scholar]

- Etxaniz, J.; Goikoetxea, A.; Uria, A.; Perez-de Viñaspre, O.; Agirre, E. Do multilingual language models think better in english? arXiv arXiv:2308.01223, 2023.

- Finch, W.H. An introduction to the analysis of ranked response data. Pract. Assessment, Res. Eval. 2022, 27, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Garg, S.; et al. Robustness of language models to input perturbations: A survey. In Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Gonen, H.; Goldberg, Y. Lipstick on a pig: Debiasing methods cover up systematic gender biases in word embeddings but do not remove them. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies; 2019; pp. 609–614. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, S.; Lee, N.; Fries, L.; Yu, T.; Su, Y.; Xu, Y.; Chang, E. Survey of hallucination in large language models. ACM Comput. Surv. 2024, 56, 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Z.; Lee, H.; Freitag, D.; Kalai, A.; Ma, Y.; West, P.; Liang, P. A survey on knowledge-enhanced pre-trained language models. ACM Computing Surveys 2023, 56, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, P.; Santy, S.; Budhiraja, A.; Bali, K.; Choudhury, M. The state and fate of linguistic diversity and inclusion in the nlp world. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; 2020; pp. 6282–6293. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall, M.G. A new measure of rank correlation. Biometrika 1938, 30, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulshrestha, J.; Eslami, M.; Messias, J.; Zafar, M.B.; Ghosh, S.; Gummadi, K.P.; Karahalios, K. Search bias quantification: Investigating political bias in social media and web search. Inf. Retr. J. 2019, 22, 188–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; et al. Long-context large language models: A survey. arXiv arXiv:2402.00000, 2024.

- Liang, P.; Bommasani, R.; Lee, T.; Tsipras, D.; Soylu, D.; Yasunaga, M.; Zhang, Y.; Narayanan, D.; Wu, Y.; Kumar, A.; et al. Holistic evaluation of language models. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; 2022; Volume 35, pp. 34014–34037. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, P.; et al. Prompting is programming: A survey of prompt engineering. Foundations and Trends in Information Retrieval, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; et al. Primacy and recency effects in large language models. arXiv arXiv:2402.12345, 2024.

- Mallen, S.; Sanh, V.; Lasocki, N.; Archambault, C.; Bavard, B.L.; Perez, G. Making retrieval-augmented language models more reliable. In International Conference on Learning Representations, May 2023. URL https://openreview.net/forum?id=u5z31A2v9a.

- Mann, H.B.; Whitney, D.R. On a test of whether one of two random variables is stochastically larger than the other. Ann. Math. Stat. 1947, 18, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCurdy, K.; Serbetci, O. Are we consistently biased? multidimensional analysis of biases in distributional word vectors. In Proceedings of the Eighth Workshop on Cognitive Aspects of Computational Language Learning and Processing; 2017; pp. 110–120. [Google Scholar]

- Meade, N.; Adel, L.; Buehler, M.T.; Nejad, K.; Kong, L.; Zhang, D.; Christiano, P.F.; Burns, C. A survey of reinforcement learning from human feedback. arXiv arXiv:2312.14925, 2024.

- Mehrabi, N.; Morstatter, F.; Saxena, N.; Lerman, K.; Galstyan, A. A survey on bias and fairness in machine learning. ACM Comput. Surv. 2021, 54, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- n8n Technologies. n8n: Workflow automation tool, 2023. URL https://n8n.io.

- Noble, S.U. Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism; NYU Press, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- OpenAI. Gpt-4 technical report, 2023. URL https://cdn.openai.com/papers/gpt-4.pdf.

- Pearson, K. On the criterion that a given system of deviations from the probable in the case of a correlated system of variables is such that it can be reasonably supposed to have arisen from random sampling. London, Edinburgh, Dublin Philos. Mag. J. Sci. 1900, 50, 157–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; Vanderplas, J.; Passos, A.; Cournapeau, D.; Brucher, M.; Perrot, M.; Duchesnay, E. Scikit-learn: Machine learning in python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Perez, E.; et al. Discovering language model behaviors with model-written evaluations. arXiv arXiv:2212.09251, 2022.

- Perrig, P.; Zhang, S.; Li, S.-E.; Ji, Y. Towards responsible deployment of large language models: A survey. arXiv arXiv:2312.00762, 2023.

- Powers, D.M.W. Evaluation: From precision, recall and f-measure to roc, informedness, markedness & correlation. J. Mach. Learn. Technol. 2011, 2, 37–63. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, M.T.; Singh, N.; Guestrin, C.; Singh, S. Beyond accuracy: Behavioral testing of nlp models with checklist. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, pages 4902–4912. Association for Computational Linguistics, July 2020. URL https://aclanthology.org/2020.acl-main.444.

- Safdari, I.; Ramesh, A.V.; Zhao, T.; Zhang, D.; Ribeiro, M.T.; Dubhashi, D.V.R.; Gupta, A.; Singla, M. Is your model biased? exploring biases in large language models. arXiv arXiv:2303.11621, 2023.

- Sap, M.; Gabriel, S.; Qin, L.; Jurafsky, D.; Smith, N.A.; Choi, Y. Social bias frames: Reasoning about social and power implications of language. In Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; 2019; pp. 2338–2352. [Google Scholar]

- Schut, L.; Gal, Y.; Farquhar, S. Do multilingual llms think in english? arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.15603. [Google Scholar]

- Seabold, S.; Perktold, J. Statsmodels: Econometric and statistical modeling with python. In Proceedings of the 9th Python in Science Conference; 2010; pp. 57–61. [Google Scholar]

- Shuster, K.; et al. Rag at scale: How retrieval augmentation reduces hallucination in large language models. arXiv arXiv:2401.00001, 2024.

- Supabase. Supabase: Open source firebase alternative, 2023. URL https://supabase.com.

- Virtanen, P.; Gommers, R.; Oliphant, T.E.; Haberland, M.; Reddy, T.; Cournapeau, D.; Burovski, E.; Peterson, P.; Weckesser, W.; Bright, J.; et al. Scipy 1.0: Fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in python. Nat. Methods 2020, 17, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willmott, C.J.; Matsuura, K. Mean absolute error: A robust measure of average error. Int. J. Climatol. 1986, 6, 516–519. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, W.; et al. Cross-lingual retrieval-augmented generation: Challenges and solutions. arXiv arXiv:2403.00001, 2024.

- Zhao, J.; Wang, T.; Yatskar, M.; Ordonez, V.; Chang, K.-W. Gender bias in coreference resolution: Evaluation and debiasing methods. In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies; 2018; pp. 15–20. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).