1. Introduction

The deep-water sedimentation mainly includes the hydrostatic sedimentation, the gravity flow sedimentation, and the traction current sedimentation. The hydrostatic sediments are often impacted by the deep-water gravity flow and the deep-water traction current, and the deep-water gravity flow sediments and the deep-water traction current sediments are usually transformed into each other [

1,

2,

3,

4]. The deep-water traction current includes the internal wave, the internal tide, and the contour current. The internal wave is the underwater wave formed at the interface of two water layers with different densities or in a water body with a density gradient [

5]. The internal wave with the same tidal cycle as the sea surface is known as the internal tide [

6]. Meanwhile, the contour current is the bottom current flowing horizontally along the seafloor isobaths [

1]. The deep-water traction current generally has flow velocities of less than 50 cm/s and carries silt to fine sand particles, which forms large-scale, well-sorted clastic sediments with bedding structures [

1,

7,

8,

9].

Since the discovery of the deep-water traction current in the 1960s, research on its sedimentation has remained in its initial stage of discovering new examples and summarizing identification signs with more modern sediments and less ancient stratum, and the research objects are mainly coarse-grained clastic sediments and rocks [

1,

3,

4]. In recent years, the shale revolution in the United States has triggered global shale oil and gas exploration and development, which has led to many studies on the shale sedimentation. Based on geochemical data, the shale has been traditionally considered to develop in the hydrostatic environment [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. By observing the morphological and mineralogical characters through thin sections, the deep-water shale was discovered to be composed of the laminae from the hydrostatic sedimentation, the gravity flow sedimentation, the traction current sedimentation, and the microbial mat [

15,

16,

17]. The deep-water shale sedimentation remains inconsistent using different evidences without the nano-resolution petrological characterization.

Using the nano-resolution petrological evidence, the authors discovered the deep-water traction current sedimentation in some Longmaxi Formation siliceous shales, Zigong area, Sichuan Basin, China [

18]. Recently, we identified a new type of deep-water traction current sedimentation in some Longmaxi Formation siliceous shales, Weiyuan area, Sichuan Basin, China. In this study, we aimed to determine (1) the occurrences of minerals and organic matters (OMs), (2) the origins of minerals and OMs, and (3) the deep-water traction current sedimentation and burial diagenesis processes.

2. Geologic Background

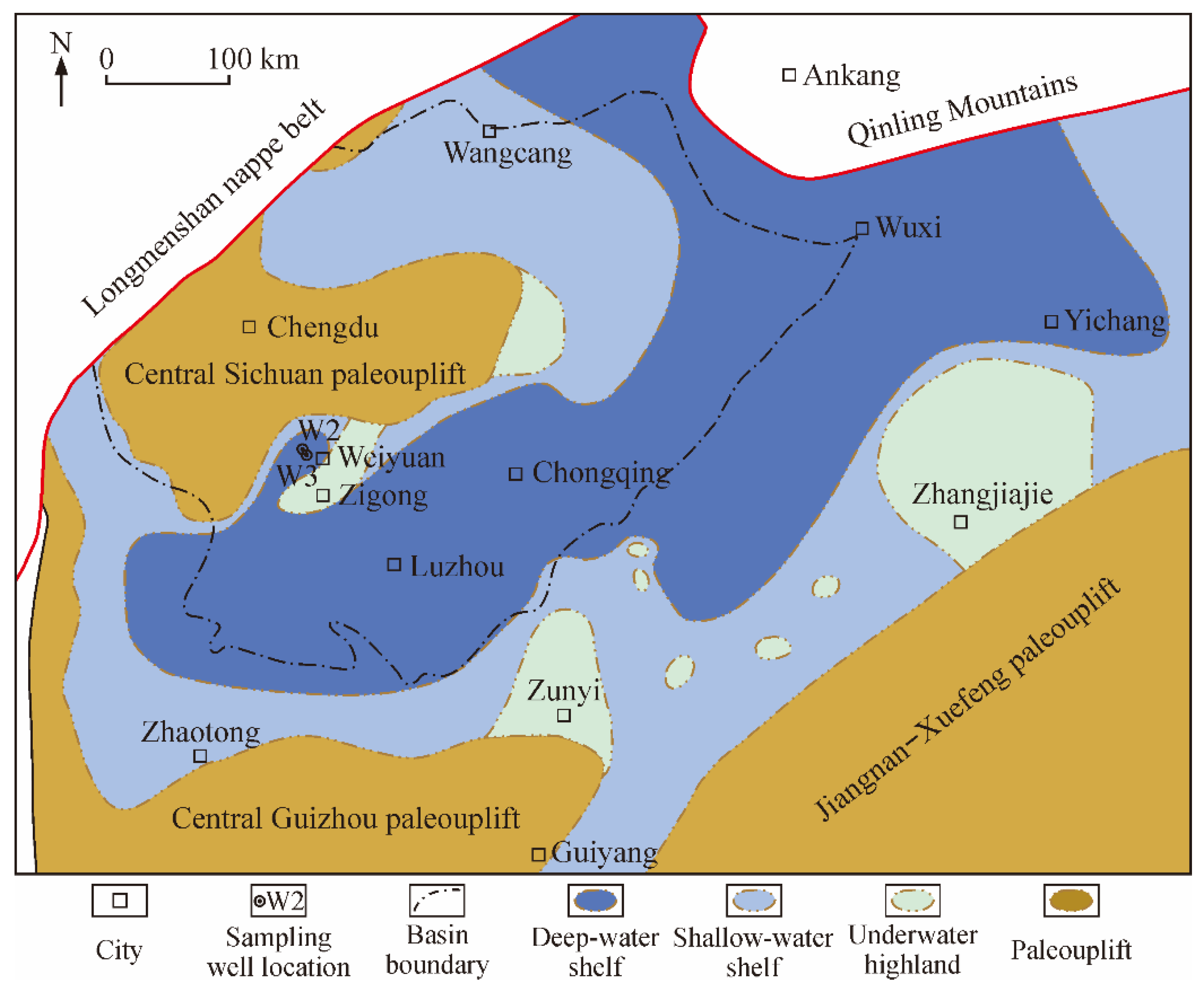

The Sichuan Basin in China is a multi-cycle sedimentary basin rich in oil and gas resources [

19,

20]. At the beginning of the Silurian, there was a deep-water shelf sedimentary system in the Sichuan Basin and its peripheral area (

Figure 1), and the black shale rich in graptolites and radiolarians was deposited and provided the material conditions for shale gas in the Longmaxi Formation [

21,

22].

Biostratigraphic correlations in outcrops and cores showed that a few of the underwater highlands occured in the Sichuan Basin and its peripheral area [

23]. These underwater highlands controlled the distribution of the sedimentary facies and lithofacies and influenced shale gas exploration and development [

25,

26]. In the Weiyuan area, there was a narrow NE–SW deep-water shelf sandwiched between the Central Sichuan paleouplift and the underwater highland (

Figure 1), and the siliceous shale was developed at the bottom of the Longmaxi Formation [

27,

28]. Research on the regional tectonic evolution has indicated that, at the beginning of the Silurian, the Guangxi movement expanded to include the Sichuan Basin and its peripheral area; this accelerated the switch from a shallow-water shelf to a deep-water shelf, forming a few of the underwater highlands [

23].

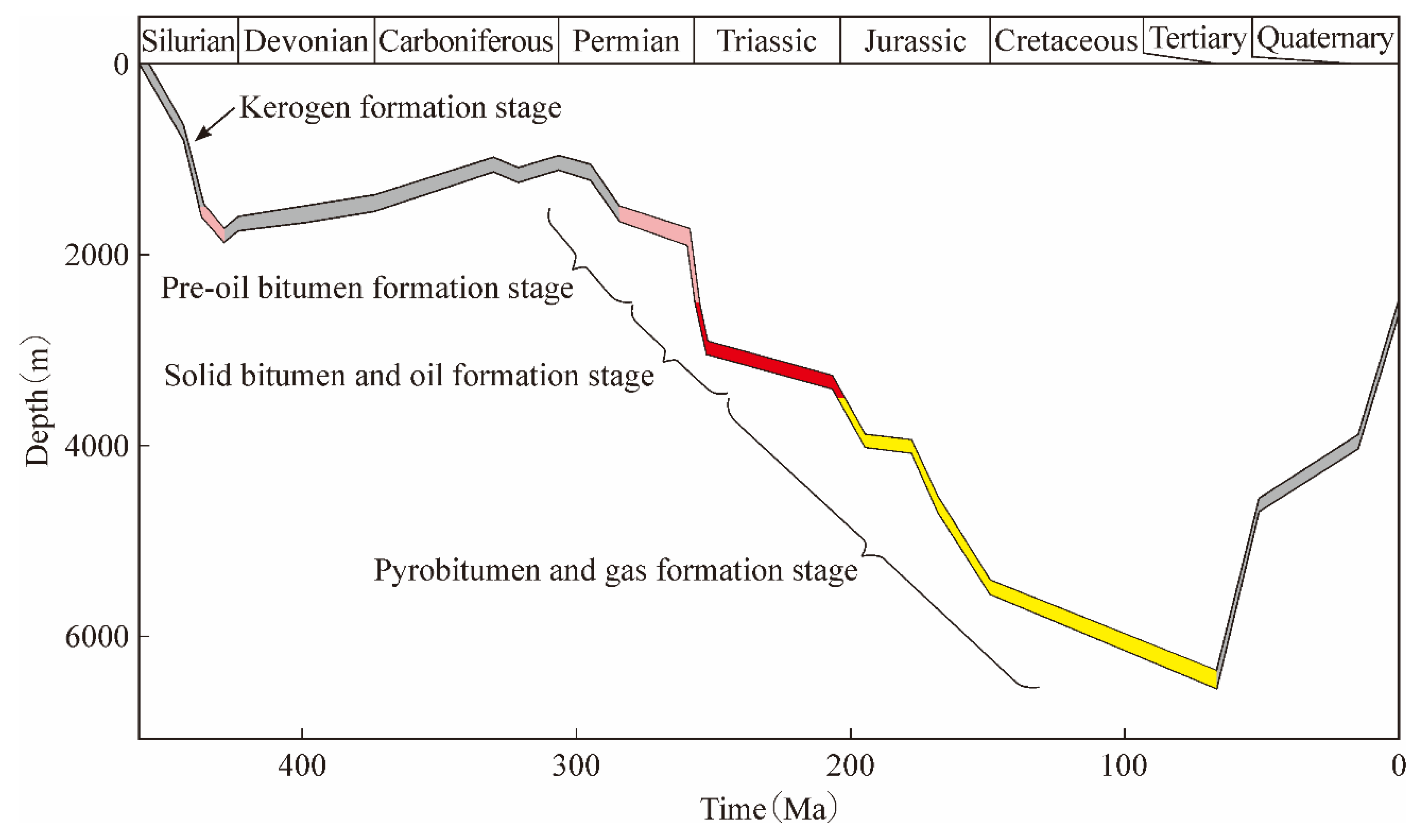

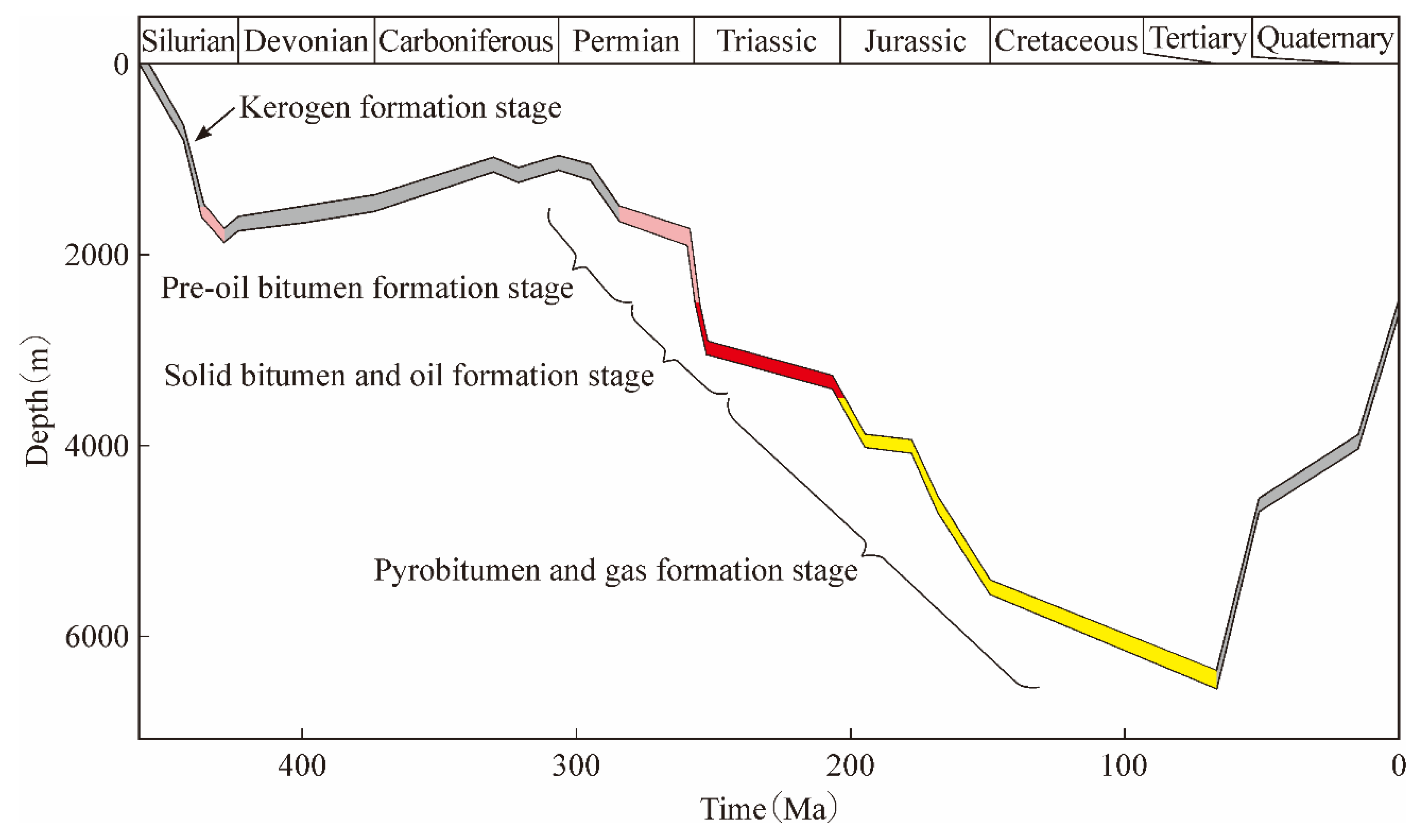

The Longmaxi Formation in the Sichuan Basin underwent two uplift events and one subsidence event (

Figure 2). In the Cretaceous, the maximum burial depth of the Longmaxi Formation was approximately 6500 m [

19], and the sedimentary organic matter (SOM) was turned into the porous pyrobitumen and the hydrocarbon gas, forming shale gas [

29]. Since the Cenozoic, the thickness eroded was generally 2000–4000 m. At present, the burial depth of the Longmaxi Formation is generally 2000–5500 m, and the structural pattern of alternating faults, folds, uplifts, and depressions leds to the differential enrichment of shale gas [

19,

30,

31,

32]. The annual gas production (m

3) of the shallow shale gas above 3500 m has reached more than 250×10

8 m

3. The deep shale gas below 3500 m is the key to increasing production in China [

33,

34].

3. Research Methods

Sampling Wells W2 and W3 were located in the narrow deep-water shelf sandwiched between the Central Sichuan paleouplift and the underwater highland (

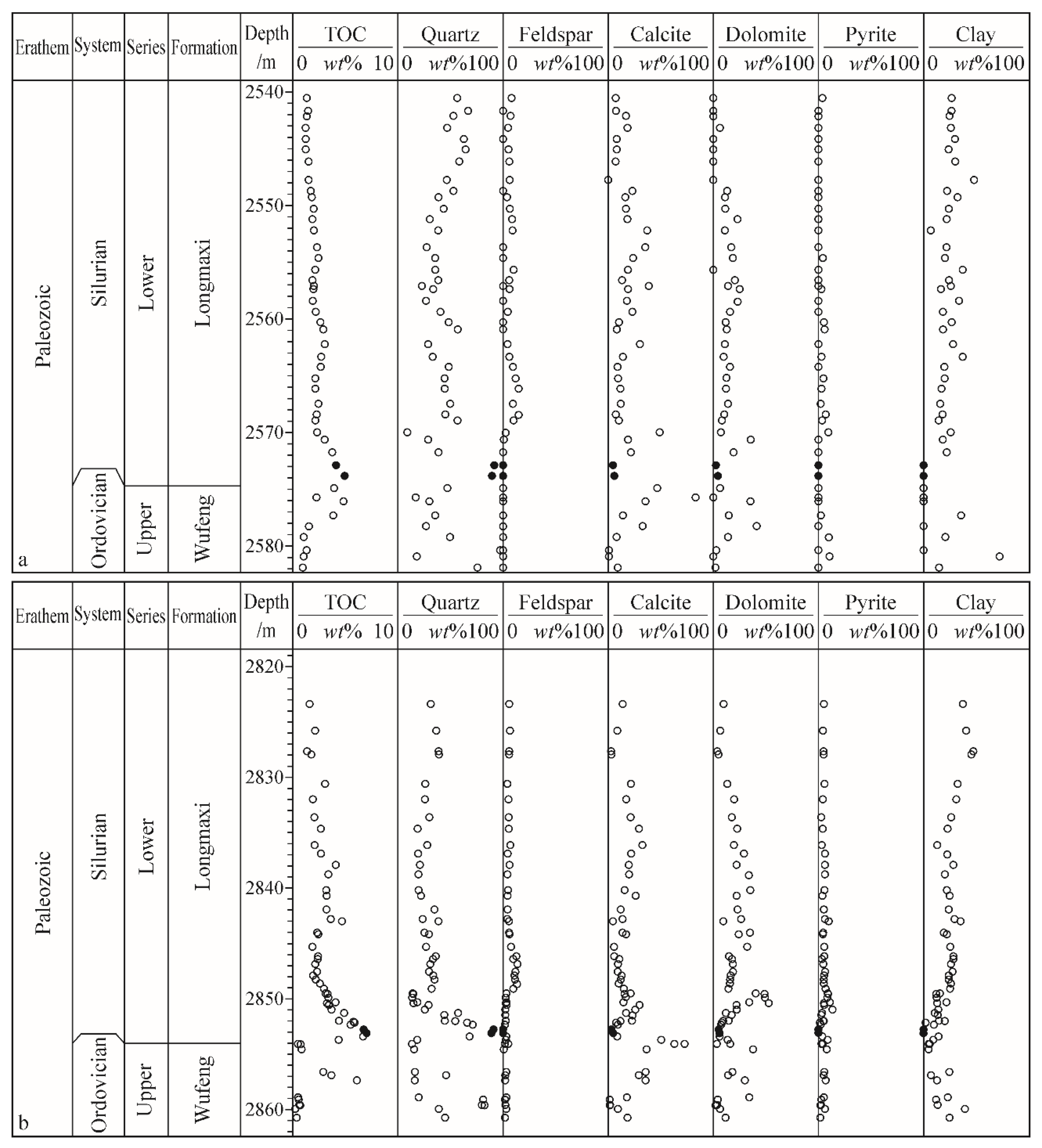

Figure 1). Based on the collect data, the profiles of the total organic carbon (TOC) data and the bulk rock analysis data were compiled for the Wufeng–Longmaxi Formations of Wells W2 and W3 (

Figure 3). At depths of 2572.87 m and 2573.82 m of Well W2 and 2852.76 m and 2853.10 m of Well W3, the contents of quartz are all approximately 90

wt%. One sample was collected from each depth (

Figure 3, black solid circles).

Four samples were cut into 1 × 1 cm argon-ion-polished slices for the nano-resolution petrological image datasets by Modular Automated Processing System (MAPS). The MAPS technology is an effective means of obtaining high-resolution, large-view petrological image datasets; this provides first-hand information for the nano-resolution petrological characterization of shale [

18,

29,

38,

39]. This technology divides the argon-ion-polished surface into a series of regular grids, obtains secondary electron scanning images with a resolution of 4 nm on each grid, concatenates all the images, and obtains a two-dimensional large-view image dataset. An offline version of the image editor (ATLAS

TM Browser-Based Viewer) is used to obtain petrological images. The preparation of argon-ion-polished slices and the acquisition of nano-resolution MAPS petrological image datasets were completed at the National Energy Shale Gas Research and Development (Experiment) Center, Langfang Branch, Research Institute of Petroleum Exploration and Development, China. The argon ion polishing instrument model is a Fischione Model 1060, the scanning electron microscope model is a Fei Helios 650, and the mineral scanner model is an Apreo 2S. Argon ion-polished slices were cut into the slices oriented perpendicular to the bedding plane. These slices were placed on an objective table according to the natural state of the samples. The acquired 4 nm resolution petrological image datasets were used to obtain continuous nano-resolution images (

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6), in order to observing and describing the occurrences of minerals and OMs and their compaction information in the siliceous shales. Using the offline image editor's measurement function, the dip angles of 100 elliptical and elongated silt-grade particles were measured in every nano-resolution petrological image dataset of the siliceous shales studied. The dip angle rose diagrams were compiled (

Figure 7).

4. Results

4.1. Occurrence of Minerals

The bulk rock analysis data showed that the quartz content in the four siliceous shales studied was approximately 90%. The calcite and dolomite contents were approximately 10%. Pyrite, feldspar, and clay were not detected (

Figure 3). However, sporadic clays (

Figure 4f, h, j–l and

Figure 5g, h, j and

Figure 6g, h) and pyrites (

Figure 5b, d–f, j and

Figure 7h) were observed in every nano-resolution petrological image dataset.

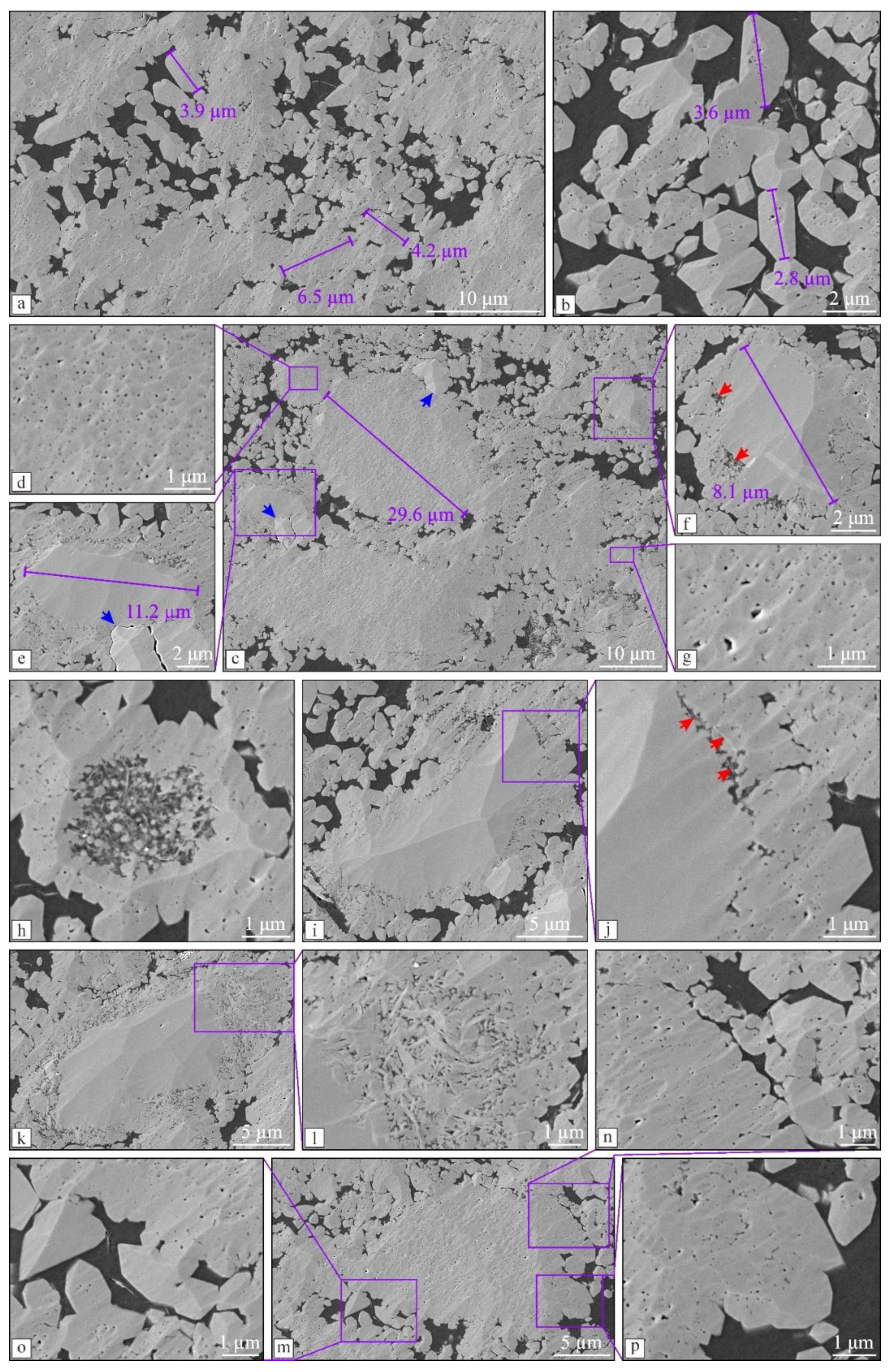

4.1.1. Quartz

Based on size, quartzs were divided into the mud-grade quartz particles and the silt-grade quartz particles, both of which constitute the main part of the siliceous shales studied (

Figure 4a, c and

Figure 5g and

Figure 6a). The sizes of the mud-grade particles are concentrated in the range of 1 nm to 4 nm, and the sizes of the silt grade particles are concentrated in the range of 6 to 30 μm. The mud-grade quartz particles occur in the form of the euhedral crystal and the anhedral crystal, with many pores in their core and no pores at their edges (

Figure 4b and

Figure 6a). Silt-grade quartz particles are circular, elliptical, and elongated (

Figure 4c). The dip angles of the long axes of the elliptical and elongated quartz particles are similar, but their dip directions are the opposite (

Figure 7). According to the degree of intragranular pore development, the silt-grade quartz particles were further subdivided into the nonporous quartz particles (

Figure 4c, e, f) and the porous quartz particles (

Figure 4c, d, g). In the siliceous shales studied, the porous mud-grade quartz particles and the porous silt-grade quartz particles dominate, whereas the nonporous silt-grade quartz particles sporadically scatter (

Figure 4a, c).

Except for a few particles in the carbonate dissolution pores (

Figure 5a), the porous mud-grade quartz particles are mainly fused through the nonporous edge to form the aggregate (

Figure 4b and

Figure 5a, b). In the siliceous shales studied, the aggregate exists in the form of three occurrences, that is, in the voids among the silt-grade quartz aggregates (

Figure 4a, c), on the surfaces of the silt-grade quartz particles (

Figure 4a, c, e, f) and the fecal pellets (

Figure 4h and

Figure 6g, h), and in the carbonate dissolution pores (

Figure 5a, b).

A mineral rim whose is composed of the porous mud-grade quartz aggregate appears on the surface of each silt-grade quartz particle. However, there is a significant difference in the mineral rims on the surfaces of quartz particles with no or rich pores. Some clays exist between the nonporous silt-grade quartz particle and its mud-grade quartz rim (

Figure 4i, j). Sometimes, a clay rim separates the nonporous silt-grade particle from the mud-grade quartz rim (

Figure 4k, l). The porous silt-grade quartz particle is completely fused with mud-grade quartz rim which usually manifests as the nonporous edge with the uneven surface (

Figure 4m–p). In the studied siliceous shales, the nonporous edges of the mud-grade quartz particles serve as hubs, connecting all the quartz particles to form a strong framework; this indicates that these siliceous shales are strong resistance to compaction.

4.1.2. Other Minerals

Other minerals included calcite, dolomite, pyrite, and clay. The calcite is in the form of the irregular morphology and the intense dissolution, and the porous mud-grade quartz particles fill in its dissolution pores (

Figure 5a). The dolomite is in the form of the rhombic morphology with the size generally greater than 10 μm and the intense dissolution, and pyrite, mud-grade quartz aggregate and nonporous OM fill in its dissolution pores (

Figure 6b, c).

Pyrite appears in two forms, namely, the overgrowth pyrite framboid and the deformed pyrite framboid. The overgrowth pyrite framboid, with the sizes between 3 and 18 μm, fills in the carbonate dissolution pore (

Figure 5b) and scatters among the quartz aggregate (

Figure 5d). The deformed pyrite framboid, is composed of dozens of the nano-grade pyrite crystals with the sizes between 300 and 500 nm, and the porous OMs fill in its intercrystalline pores (

Figure 5e, f). Typically, the deformed pyrite framboid with irregular morphology is the mixture of pyrite crystals and mud-grade quartz particles (

Figure 5e, f).

Multiple clay occurrences were observed. Flaky clays (mica) occur among the quartz aggregate (

Figure 5g). Clay rim or sporadic clays adhere on the surface of the nonporous silt-grade quartz particle (

Figure 5i–l). Flocculent clays appear in the fecal pellets (

Figure 4h and

Figure 6h). Sporadic clays scatter in the porous OM (

Figure 5h) and the nonporous OM (

Figure 5i).

4.2. Occurrence of OM

According to the development degree of pores, the OMs were divided into the porous OMs and the nonporous OMs. The porous OM only fills in the voids among the mineral particles (

Figure 6a). the nonporous OM occur in the voids among the mineral particles (

Figure 6b), in the fecal pellet (

Figure 4h), in carbonate dissolution pores (

Figure 5b), in the secondary pores in the fecal pellets (

Figure 6g and h), and in the secondary pore in a mud-grade quartz aggregate (

Figure 6i).

When the porous OMs fills in the voids among the porous quartz particles, the nonporous edges of the quartz particles are thin and rarely develop into complete crystal prisms (Figur 6a, b). When the nonporous OMs appear in the voids among the porous quartz particles, the nonporous edges of the quartz particles are thick and show the prominent crystal prisms (

Figure 6c, d). When both the porous OM and the nonporous OM coexist in the same pore, the development of quartz edges in contact with the porous OM is weak (

Figure 6e, f) and that in contact with the nonporous OM is relatively prominent (

Figure 6e, f).

The nonporous OMs fill in the secondary pores in the fecal pellets (

Figure 6g, h) and the mud-grade quartz aggregate (

Figure 6i). These secondary pores whose opposing walls well piece together manifest as the split features of the mud-grade quartz aggregate and the fecal pellets. The secondary pores and voids among the mineral particles usually interconnect and are filled with the nonporous OMs (

Figure 7h, i); this indicates that the nonporous OMs in these two occurrences are homologous.

4.3. Occurrence of Fecal Pellet

Flocculent blocks that are composed of nano-grade silicons, clays, and nonporous OMs sporadically scatter in the siliceous shale studied. They significantly differ from the background of the lack of clay in their surroundings. It is preliminarily inferred that they are the fecal pellets produced by the microbial metabolism. The fecal pellets are encased in the mud-grade quartz rims to form the silt-grade fossil particles (

Figure 4h and

Figure 7g, h). The secondary pores formed by the splitting of the fecal pellets are filled with the nonporous OM (

Figure 6g, h).

5. Discussions

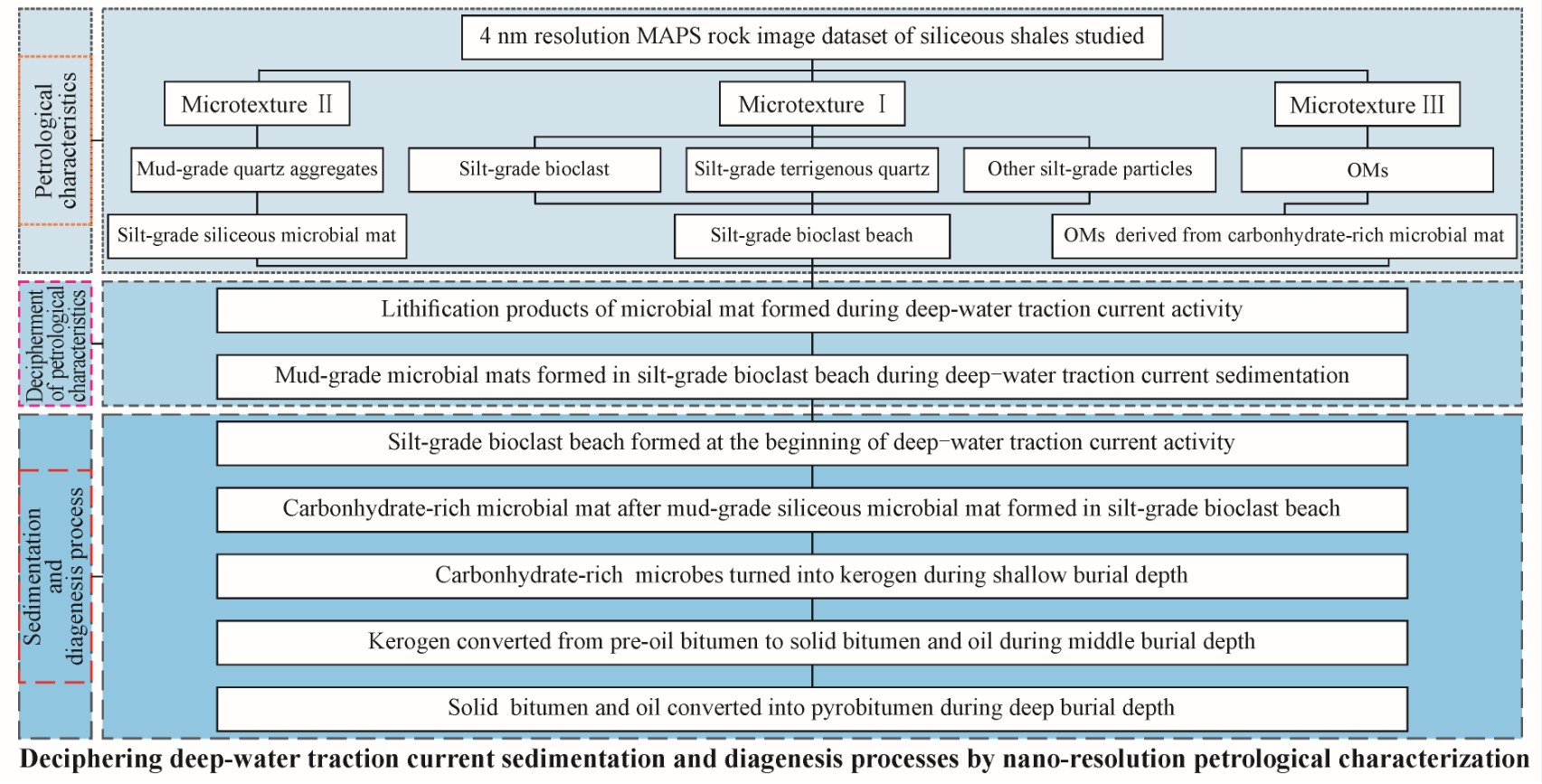

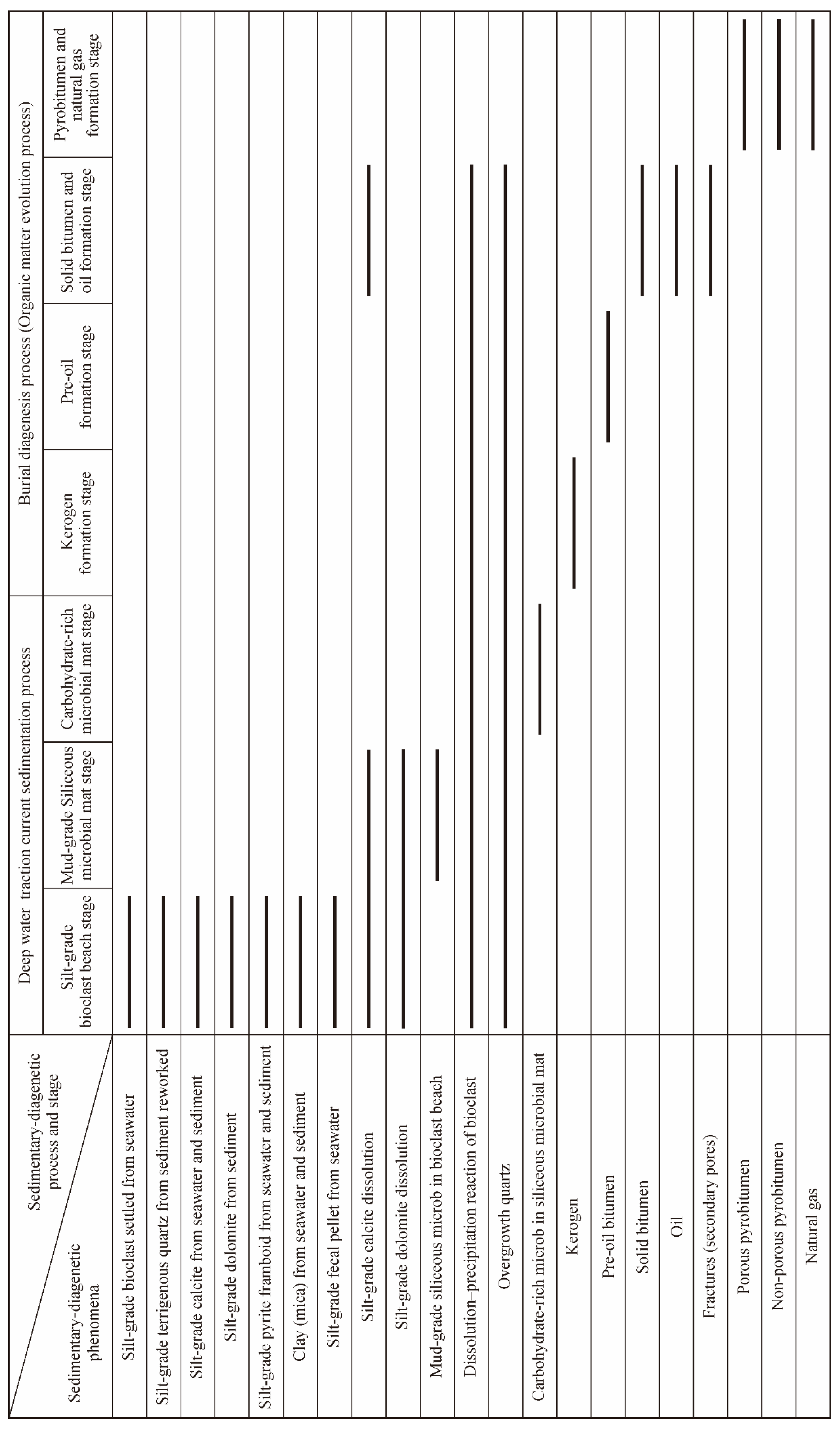

Using MAPS technology, we showed that the siliceous shales studied were the lithification of the microbial mats formed by the deep-water traction current sedimentation (

Figure 8). The formation process of the microbial mats was divided into three stages, elucidating the growth sequences of the siliceous microbial mats and the carbohydrate-rich microbial mats. Subsequently, the petrogenetic process of the microbial mats was delineated into four stages, highlighting the transformation of biogenic silica and SOM into the various forms of quartz and pyrobitumen.

5.1. Origin of Minerals and OMs

Minerals mainly include quartz, carbonate, pyrite. OMs consist of the porous OM and the nonporous OM.

The quartz occurs in the forms of porous mud-grade quartz, porous silt-grade quartz and nonporous silt-grade quartz. The porous mud-grade and silt-grade quartzs originate from microbial silica [

18,

40,

41], and the nonporous silt-grade quartz is the terrigenous clast [

18]. Carbonate minerals occur in the forms of irregular calcite and rhombic dolomite. The irregular calcite is the byproduct of photosynthesis by microbes that secrete calcium carbonate [

42], and the phenomenon that the porous mud-grade quartz particles fill in its dissolution pores indicate that siliceous microbes lived in the pores. The rhomboid dolomite is an authigenic mineral near the water―sediment interface [

42], and the phenomenon that the porous mud-grade quartz aggregate fills in the incomplete rhomboid dolomite dissolution pores imply that the dolomite underwent the strong chemical weathering and weak physical weathering and siliceous microbes lived in its dissolution pores. The pyrite framboid in the Longmaxi Formation of the Sichuan Basin developed near the interface of aerobic and anoxic water bodies [

43,

44], and the phenomenon that some porous mud-grade quartzs fill in the irregular pyrite framboids indicate that the framboids were transformed into different shapes during the microbial activity.

SOM went through four stages of evolution [

18,

29]. In the shallow burial diagenesis stage, SOM turned into the Type I and II kerogens [

35,

36,

37]. In the early diagenesis stage of the moderate burial, the kerogens transformed into the pre-oil bitumen. In the late diagenesis stage of the moderate burial, the pre-oil bitumen converted into the solid bitumen and the oil. In the deep burial diagenesis stage, the solid bitumen evolved into the porous pyrobitumen and the oil turned into the nonporous pyrobitumen. In the siliceous shale studied, the porous pyrobitumen (the porous OM) from the solid bitumen fills in the voids among the quartz aggregate, and the nonporous pyrobitumen (the nonporous OM) from the oil fills in the voids among the quartz aggregate and in the secondary pores.

The phenomenon that the porous mud-grade quartz rim lacks between the silt-grade quartz particle and the calcite particle indicate that the activity time of the siliceous microbes was later than the deposit time of the silt-grade quartz and calcite particles.

5.2. Sedimentary Environment of Siliceous Shales Studied: Deep-Water Traction Current Sedimentation

At the beginning of the Silurian, a deep-water shelf opened northward in the Sichuan Basin [

22]. During the wave-like push of the Guangxi movement from south to north, there were a few of the underwater highlands in the Sichuan Basin and its peripheral area [

23]. A northeast-trending underwater highland existed in the Weiyuan area, and it connected to the Central Sichuan paleo-uplift toward the north and submerged in the deep-water shelf toward the south [

27,

28,

45]. Under the sandwiching between the underwater highland and the Central Sichuan paleo-uplift, there was a narrow, deep-water bay in the Weiyuan area (

Figure 1), preparing the favorable topographic condition for the formation of the deep-water traction current [

1,

3,

4].

The deep-water traction current on seafloor sediments has a certain flow velocity [

7,

9], which has two functions. on the one hand, the vertically settling clays and OMs are carried away while the vertically settling silt-grade microbial silica and calcite particles are deposited. On the other hand, unconsolidated sediments are reworked, and clays and OMs are carried away while the silt-grade terrigenous quartz with the residual clays on its surface, irregular calcite particles and rhomboid dolomite particles are deposited. Under the influence of the two functions, both the vertically settling silt-grade particles and the

in situ silt-grade particles are mixed together and the microbial silica content is much higher than other mineral content, forming the silt-grade bioclastic beach in which the deep-water traction current flows. the calcite content is less than 10% in each sample point (

Figure 3), which indicates that the beach lies under the carbonate compensation depth (CCD) and calcite and dolomite particles strongly dissolve [

42].

The deep-water traction current is rich in oxygen and nutrients [

15,

16,

46], so mud-grade siliceous microbes become active in the bioclastic beach. Microbes aggregate and inhabit on the surfaces of grains and in the carbonate dissolution pores to resist erosion by the deep-water traction current, forming a microbial mat. In the siliceous microbial mat, an increasing number of microbes grow; this leads to a decrease in the flow velocity of the deep-water traction current and is unsuitable for mud-grade siliceous microbes because of lack of oxygen and nutrients. This provides favorable conditions for carbohydrate-rich microbes to flourish, and the carbohydrate-rich microbial mat replaces the siliceous microbial mat. The predecessor of the siliceous shales studied, siliceous soft mud, is formed at this point.

The occurrences of the particles reworked by the deep-water traction current vary significantly. Almost all the clays were carried away, resulting in sporadic residue in the siliceous rock, which was not detected in the whole rock data (

Figure 3). Based on the presence of clays or the clay rim on the surface of the silt-grade terrigenous quartz, this quartz was inferred from the reworked sediments. The absence of clays on the silt-grade microbial silica indicates that the silica is from the siliceous microbes in seawater and that the fecal pellet is the metabolic material of the microbes. The calcite particles and pyrite framboids may be either from the endogenous clasts deposited in seawater or from the reworked sediments.

It is difficult to conclude whether the deep-water traction current is an internal wave, an internal tide or an contour current. However, the potential for it being an internal wave or tide is more likely based on the following evidence. The sedimentary background of a deep-water slope increases the potential for internal waves and internal tides [

1,

47,

48]. The phenomenon that long axes of the elliptical and elongated silt-grade particles have opposite directions is consistent with the characteristics of the bi-directional currents of the internal wave and the internal tide [

1,

47,

48]. The ability to rework loose sediments is consistent with the characteristics of internal waves and internal tides [

9,

49].

5.3. Burial Diagenesis Process of Microbial Mat

The microbial mats in the burial diagenesis process were converted into the siliceous shales studied through a series of physical and chemical changes. Of these, the most important changes include the conversion of SOM into pyrobitumen in various forms and the conversion of the siliceous silica into the porous quartz. In this study, based on the main line of the thermal evolution of SOM, the burial diagenesis process of the microbial mat was divided into four stages, that is, kerogen, pre-oil bitumen, solid bitumen and oil, and pyrobitumen and gas formation stages (

Figure 8).

In the kerogen formation stage, SOM underwent a condensation reaction to form the kerogen. The biogenic silica clast underwent a dissolution–precipitation reaction with a large amount of Si discharged [

18,

50]. Here, the fluid environment is more favorable for quartz overgrowth. During the pre-oil bitumen formation stage, the kerogen is converted into the pre-oil bitumen, and the quartz overgrowth continues on the walls of the remaining intergranular pore space. In the solid bitumen and oil formation stage, the pre-oil bitumen is converted to the solid bitumen and the oil, which caused the volume expansion of the fluid and produced an abnormally high fluid pressure. Under the action of the abnormally high fluid pressure, the secondary pores and fractures were formed, which became channels for the primary migration of oil. The dissolution–precipitation reaction of biogenic silica was halted. In the pyrobitumen and gas formation stage, the solid bitumen is converted to the porous pyrobitumen (the porous OM), whereas the oil is converted to the nonporous pyrobitumen (the nonporous OM).

6. Overview

Integrating the sedimentation and diagenesis processes, a coupled pattern of deep-water traction current sedimentation–diagenesis processes was established for the siliceous shales studied (

Figure 8). This pattern can explain all the observed nano-resolution petrological phenomena. As shown in

Figure 8, the dissolution of carbonate minerals mainly occurs in the deep-water traction current sedimentation. The quartz overgrowth develops from the sedimentation process to the solid bitumen and oil formation stage. Therefore, the study of the formation mechanism of shale reservoirs requires an integrating analysis of sedimentation and diagenesis, and nano-resolution petrological characterization is one way to realize the analysis.

There have been three views on the formation of the mud-grade quartz aggregate in the siliceous shales. one view suggests that it is the authigenic mineral aggregate [

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62], other view suggests it is the floating microbial aggregate or mats in deep-water sulfate-reducing environments [

63,

64,

65], and the third view suggests that it is the recrystallization of microbial silica [

66,

67,

68,

69]. This paper found that the mud-grade quartz particle has a bilayer structure with the core and the edge. The core is the porous quartz converted from the microbial silica and the edge is the secondary quartz overgrowth by the dissolution–precipitation reaction of microbial silica, which proves that the mud-grade quartz aggregate is the siliceous microbial aggregate rather than the authigenic mineral aggregate. The following five nano-resolution petrological evidences do not support that the mud-grade quartz aggregate is from the floating microbial aggregate or mat: (1) The similar dip angles and the opposite dip directions of the long axes of the elliptical and elongated quartz particles indicate that these particles are the result of the traction current sedimentation, (2) The clay rim occurs on the surface of the terrigenous quartz rather than the surface of the microbial silica, (3) The pyrite framboid is transformed into the irregular nano-grade pyrite and quartz aggregate, (4) The clay and the OM-clay aggregate lack, (5) the overgrowth pyrite framboid and the mud-grade microbial silica fill in the dissolution pores of the rhomboid dolomite particles. However, the petrogenesis of the microbial mats formed by deep-water traction current sedimentation systematically explain these features.

Although the Weiyuan and Zigong areas in the Sichuan Basin are not far apart (

Figure 1), the deep-water traction flow sedimentation is significantly different [

18]. In the Zigong area, the siliceous shales lithified from the deep-water traction current sediments are composed of three microtextures. Microtexture I mainly consists of a micro-quartz and nano-quartz skeleton and the voids contain porous organic matter. Microtexture II is comprised of clay-rich patches. Microtexture III is composed of non-porous dendritic organic matter. Microtexture I constitutes the main part of the siliceous shale, and both Microtexture II and Microtexture III are sporadically encased in Microtexture I. By deciphering the microtextures, in Microtexture I the porous micro-quartz and the porous nano-quartz are from the siliceous microbial mats and the porous OM is from the carbohydrate-rich microbial mat, and Microtexture II is composed of residual clay-rich sediments that are not damaged by the deep-water tracton current, and Microtexture III is composed of the pyrobitumen derived from the oil in hydrocarbon-generating pressurized dendritic fractures. Microtexture II may be the reason for the appearance of Microtexture III in Microtexture I. In the Weiyuan area, the porous silt-grade quartz aggregate is the main bogy of the bioclastic beach, and the porous mud-grade quartz aggregate is from the siliceous microbial mat, and the porous OM is from the carbohydrate-rich microbial mat. Due to the weak heterogeneity of the rock structure, the hydrocarbon-generating pressurized dendritic fractures do not develop, and the oil is migrated out through the pore network that consists of the secondary pores and the primary voids among the mineral particles.

The results of this study improve our understanding of the environment and processes that produced the siliceous shale in the Longmaxi Formation and can be extended to other areas such as other underwater highlands in the Sichuan Basin and similar reservoirs worldwide. The siliceous shales formed by the deep-water traction current sedimentation are the high-quality reservoir because of their high content of quartz and porous OM. With increased shale oil and gas exploration and development, as well as the continuous application and promotion of nano-resolution petrological characterization techniques, more and more deep-water traction current sediments will be discovered worldwide.

7. Conclusions

The application of MAPS technology to acquire a nano-resolution petrological image dataset was used to observe and describe the occurrences of minerals and OMs and then to carry out nano-resolution petrological characterization and achieved the following results.

(1) The siliceous shales studied at the bottom of the Longmaxi Formation in the Weiyuan area, Sichuan Basin, were proposed to be the lithified products of the microbial mats formed by the deep-water traction current sedimentation. This understanding can systematically explain all the nano-resolution petrological phenomenon observed.

(2) The microbial mat formation process was divided into three stages. The first stage is the formation stage of the silt-grade bioclast beach. The second stage is the formation stage of the mud-grade siliceous microbial mat. The third stage is the formation stage of the carbohydrate-rich microbial mat.

(3) The petrogenetic process of the microbial mats was divided into four stages. During the kerogen formation stage, SOM is turned into the Type I and II kerogens. In the pre-oil bitumen formation stage, the kerogens are converted into the pre-oil bitumen. In the solid bitumen and oil formation stage, the pre-oil bitumen is transformed into the solid bitumen and the oil; this produces anomalously high pressure and thus generates the secondary pores. In the pyrobitumen formation stage, the solid bitumen is evolved into the porous pyrobitumen, and the oil is derived into the nonporous pyrobitumen.

(4) The siliceous shales formed by the deep-water traction current sedimentation are the high-quality reservoir because of their high content of quartz and porous OM. With increased shale oil and gas exploration and development, as well as the continuous application and promotion of nano-resolution petrological characterization techniques, more and more deep-water traction current sedimentation will be discovered in the Sichuan Basin and worldwide.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing-original draft, Writing-review and editing, Xiaofeng Zhou; Writing-original draft, Fund acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration and Resources, Pingping Liang; Fund acquisition, Investigation, Project administration and Resources, Wei Guo; Data curation, Writing-original draft, Jun Zhao and Baonian Yan; Investigation, Data curation, editing all Figures, Zeyu Zhu and Nan Yang. All the authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the 14th Five-Year Plan of the Ministry of Science and Technology of PetroChina, grant: 2021DJ1901, and by the National Science and Technology Major Project of the Ministry of Science and Technology of China Project, grant: 2016ZX05037006.

Data Availability Statement

All used data are included in this publication as a digital supplement.

Acknowledgments

The authors give special thanks to the State Key Laboratory of Petroleum Resources and Prospecting, China University of Petroleum (Beijing) and the National Energy Shale Gas Research and Development (Experiment) Center, Langfang Branch, Research Institute of Petroleum Exploration and Development, China, for their assistance in the preparation of argon ion polished slices, nano-resolution petrological observations, and mineral quantitative analysis. In addition, the authors thank the editors and reviewers for their help in revising and improving the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Gao, Z.Z.; He, Y.B.; Luo, S.S. Deep-water tractive current deposits——The study of internal-tide, internal wave and contour current deposits. Beijing: Science Press, 1996, 1-107. (In Chinese).

- Alonso, B.; Ercilla, G.; Casas, D.; Stow, D.A.V.; Rodríguez-Tovar, F.J.; Dorador, J.; Hernández-Molina, F.J. Contourite vs gravity-flow deposits of the Pleistocene faro drift (Gulf of Cadiz): Sedimentological and mineralogical approaches. Marine Geology 2016, 377, 77-94. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.margeo.2015.12.016.

- Li, X.D. Current situation of combined-flow deposition for sedimentary characteristic series and its theory frame work. Advances in Earth Science 2021, 36(4), 375-389. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; He, M.W.; Qiu, C.G.; Wang, Y.M.; He, Y.B.; Xu, Y.X.; He, R.W. Research processes on deep-water interaction between contour current and gravity flow deposits, 2000 to 2022. Acta Sedimentologica Sinica 2023, 41(1), 18-36. [CrossRef]

- Lafond, E.C. Internal waves. In: Fairbridge, R.W. (edit). The Encyclopedia of Oceangraphy. NewYork: Reinhold, 1966, 402-408.

- Rattray, M. On the coastal generation of internal tides. Tellus 1960, 12(1), 54-62.

- Mullins, H.T.; Keller, G.H.; Kofoed, J.W.; Lambert, D.N.; Stubblefield, W.L.; Warme, J.E. Geology of great Abaco submarine canyon (Blake Plateau): Observations from the research submersible “Alvin”. Marine Geology 1982, 48(3–4), 239-257. [CrossRef]

- Reeder, D.B.; Ma, B.B.; Yang, Y.J. Very large subaqueous sand dunes on the upper continental slope in the South China Sea generated by episodic, shoaling deep-water internal solitary waves. Marine Geology 2011, 279, 12-18. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, W.; Alves, T.M.; Rebesco, M.; Wu, S. Different origins of seafloor undulations in a submarine canyon system, northern South China Sea, based on their seismic character and relative location. Marine Geology 2019, 413, 99-111.

- Hancock, L.G.; Hardisty, D.S.; Beh, R.J.; Lyons, T.W. A multi-basin redox reconstruction for the Miocene Monterey Formation, California, USA. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 2019, 520, 114-127. [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.; Hu, W.; Cai, Q.; Wei, S.; She, J.; Wang, X.; Liu, X. Sedimentary environment and organic accumulation of the Ordovician–Silurian Black Shale in Weiyuan, Sichuan Basin, China. Minerals 2023, 13, 1161. [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Huang, S.; Sun, M.; Wen, Y.; Chen, W.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, F.; Zhang, H. Palaeoenvironmental evolution based on elemental geochemistry of the Wufeng-Longmaxi shales in Western Hubei, Middle Yangtze, China. Minerals 2023, 13, 502. [CrossRef]

- Arfaoui, I.; Hamdi, O.; Boulvain, F. Geochemical and mineralogical characterizations of Silurian ‘Hot’ shales: Implications for shale gas/oil reservoir potential in Jeffara basin-southeastern Tunisia, North Africa. Journal of African Earth Sciences 2024, 212, 105213. [CrossRef]

- Fu, C.; Feng, Z.; Xu, C.; Zhao, X.; Du, Y. Geochemical characteristics of organic-enriched shales in the Upper Ordovician–Lower Silurian in Southeast Chongqing. Minerals 2025, 15, 447. [CrossRef]

- Knapp, L.J.; McMillan, J.M.; Harris, N.B. A depositional model for organic-rich Duvernay Formation mudstones. Sedimentary Geology 2017, 347, 160-182. [CrossRef]

- Leonowicz, P.; Bienkowska-Wasiluk, M.; Ochmanski, T. Benthic microbial mats from deep-marine flysch deposits (Oligocene Menilite Formation from S Poland): Palaeoenvironmental controls on the MISS types. Sedimentary Geology 2021, 417, 105881. [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.S.; Zhao, S.X.; Zhou, T.Q.; Sun, S.S.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, C.L.; Li, B.; Qi, L. Types and genesis of horizontal bedding of marine gas-bearing shale and its significance for shale gas: A case study of the Wufeng–Longmaxi shale in southern Sichuan Basin, China. Oil & Gas Geology 2023, 44(6), 1499-1514. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.F.; Guo, W.; Li, X.Z.; Liang, P.P.; Yu, J.M.; Zhang, C.L. Deciphering nano-resolution petrological characteristics of the siliceous shale at the bottom of the Longmaxi Formation in the Zigong area, Sichuan basin, China: Deep-water microbialites. Minerals 2024, 14(10), 1020. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.G.; Deng, B.; Zhong, Y.; Ran, B.; Yong, Z.Q.; Sun, W.; Yang, D.; Jiang, L.; Ye, Y.H. Unique geological features of burial and superimposition of the Lower Paleozoic shale gas across the Sichuan Basin and its periphery. Earth Science Frontier 2016, 23(1), 11-28. [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.L.; Han, J.H.; Luo, C.; Luo, Q.H.; Han, K.Y. The discovery, characteristics and prospects of commercial oil and gas layers/reservoirs in Sichuan Basin. Xinjiang Petroleum Geology 2013, 34(5), 504-514, 495.

- Nie, H.K.; He, Z.L.; Liu, G.X.; Du, W.; Wang, R.Y.; Zhang, G.R. Genetic mechanism of high-quality shale gas reservoirs in the Wufeng–Longmaxi Fms in the Sichuan Basin. Natural Gas Industry 2020, 40(6), 31-41. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.M.; Li, X.J.; Dong, D.Z.; Zhang, C.C.; Wang, S.F. Main factors controlling the sedimentation of high-quality shale in Wufeng–Longmaxi Fm, Upper Yangtze Region. Natural Gas Industry 2017, 37(4), 9-20. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Chen, Q.; Zhen, Y.Y.; Wang, H.Y.; Zhang, L.N.; Zhang, J.P.; Wang, W.H.; Xiao, Z.H. Circumjacent distribution pattern of the Lungmachian graptolitic black shale (early Silurian) on the Yichang Uplift and its peripheral region. Science China Earth Sciences 2018, 48(9), 1198-1206. [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.H.; Xie, J. The progress and prospects of shale gas exploration and exploitation in southern Sichuan Basin, NW China. Petroleum Exploration and Development, 2018, 45(1), 161-169. [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Li, X.Z.; Zhang, X.W.; Lan, C.L.; Liang, P.P.; Shen, W.J.; Zheng, M.J. Sedimentary microfacies and microrelief of organic-rich shale in deep-water shelf and their control on reservoirs: a case study of shale from Wufeng–Longmaxi formations in southern Sichuan Basin. Acta Petrolei Sinica 2022, 43(8), 1089-1106.

- Shi, Z.S.; Yuan, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Sun, S.S.; Zhou, T.Q.; Cheng, F. Paleogeomorphology and oil-bearing shale characteristics of the Wufeng–Longmaxi shale in southern Sichuan Basin, China. Natural Gas Geoscience 2022, 33(12), 1969-1985.

- Liang, F.; Wang, H.Y.; Bai, W.H.; Guo, W.; Zhao, Q.; Sun, S.S.; Zhang, Q.; Wu, J.; Ma, C.; Lei, Z.A. Graptolite correlation and sedimentary characteristics of Wufeng–Longmaxi shale in southern Sichuan Basin. Natural Gas Industry 2017, 37(7), 20-26. [CrossRef]

- Liang, F.; Zhang, Q.; Lu, B.; Jiang, W.; Xiong, X.L.; Chen, P.; Jiang, R.; Liang, P.P.; Ma, C. Lithofacies and distribution of Wufeng Formation–Longmaxi Formation organic-rich shale and its impact on shale gas production in Weiyuan Shale Gas Play, Southern Sichuan Basin, China. Acta Sedimentologica Sinica 2022, 40(4), 1019-1029. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.F.; Guo, W.; Li, X.Z.; Zhang, X.W.; Liang, P.P.; Yu, J.M. Mutual relation between organic matter types and pores with petrological evidence of radiolarian siliceous shale in Wufeng–Longmaxi Formation, Sichuan Basin. Journal of China University of Petroleum (Edition of Natural Science) 2022, 46(5), 12-22. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.F.; Zhang, C.L.; Zhao, S.X.; Zhang, J.; Feng, J.R.; Xia, Z.Q.; Fang, Y.; Li, B.; Yin, M.X.; Zhang, D.K. Typical types of shale gas reservoirs in southern Sichuan Basin and enlightenment of exploration and development. Natural Gas Geoscience 2023, 34(8), 1385-1400. http://doi.org/10.1 1764/j.issn.1672-1926.2023.04.006.

- Bai, W.H.; Xv, S.H.; Liu, Z.Q.; Mei, L.F.; Cheng, F. Classification of shale gas enrichment patterns based on structural styles: a case study of the Wufeng Formation and Longmaxi Formation in Sichuan Basin, China. North China Geology, 2024, 47(1), 52-65. http://doi.org/10.19948/j.12-1471/P.2024.01.05.

- Zhang, M.L.; Li, G.Q.; Kou, Y.L.; Li, K.; Chen, J.; Xu, J.L.; He, J.; Liang, X.; Fan, Q.H. Differential enrichment of shale gas in anticline and syncline tectonic units in fold deformation area. Geological Review 2024, 70(Supp.1), 272-274.

- Zou, C.N.; Zhao, Q.; Cong, L.Z.; Wang, H.Y.; Shi, Z.S.; Wu, J.; Pan, S.Q. Development progress, potential and prospect of shale gas in China. Natural Gas Industry 2021, 41(1), 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Zou, C.N.; Dong, D.Z.; Xiong, W.; Fu, G.Y.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, W.; Kong, W.L.; Zhang, Q.; Cai, G.Y.; Wang, Y.M.; Liang, F.; Liu, H.l.; Qiu, Z. Advances,challenges,and countermeasures in shale gas exploration of underexplored plays,sequences and new types in China. Oil & Gas Geology,2024,45(2), 309-326.

- Qin, J.Z.; Li, Z.M.; Liu, B.Q.; Zhang, Q. The potential of generating heavy oil and solid bitumen of excellent marine source rocks. Petroleum Geology & Experiment 2007, 29(3), 280-285, 291. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.Y.; Gao, P.; Xiao, X.M.; Liu, R.B.; Qin, J.; Yuan, T.; Wang, X. Study on organic petrology characteristics of the Wufeng-Longmaxi Formation black shale, Sichuan Basin. Geoscience 2022,36(5), 1281-1291. [CrossRef]

- Liu, B. Organic matter in shales: types, thermal evolution, and organic pores. Earth Science 2023, 48(12), 4641-4657. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.F.; Guo, W.; Li, X.Z.; Zhang, X.W.; Liang, P.P.; Yu, J.M. Occurrence characteristics, genesis and petroleum geological significance of micro-nano silica-organic matter aggregate in radiolarian siliceous shell cavity: a case study of Wufeng–Longmaxi Formation in Sichuan Basin, SW China. Journal of Northeast Petroleum University 2021, 45(6), 68-79. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.F.; Liang, P.P.; Li, X.Z.; Guo, W.; Zhang, X.W.; Yu, J.M. Filling characteristics of radiolarian siliceous shell cavities at Wufeng–Longmaxi Shale in Sichuan basin, Southwest China. Minerals 2022, 12, 1545. [CrossRef]

- Jones, B.; Renaut, R.W. Microstructural changes accompanying the opal-A to opal-CT transition: New evidence from the siliceous sinters of Geysir, Haukadalur, Iceland. Sedimentology 2007, 54, 921-948. [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.C. Research progress in early diagenesis of biogenic silica. Geological Review 2010, 56(1), 89-98. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.F.; Li, X.Z.; Guo, W.; Zhang, X.W.; Liang, P.P.; Yu, J.M. Characteristics, formation mechanism and influence on physical properties of carbonate minerals in shale reservoir of Wufeng–Longmaxi formations, Sichuan Basin. Natural Gas Geoscience 2022, 33(5), 775-788.

- Han, S.B.; Li, W. Study on the genesis of pyrite in the Longmaxi Formation shale in the Upper Yangtz earea. Natural Gas Geoscience 2019, 30(11), 1608-1618.

- Duan, X.G.; Xian, Y.K.; Yuan, B.G.; Dai, X.; Cao, J.J.; Liu, Z.Y.; Liu, X. Formation mechanism and formation environment of framboidal pyrite in Wufeng Formation–Longmaxi Formation shale and its influence on shale reservoir in the southeastern Chongqing, China. Journal of Chengdu University of Technology (Science and Technology Edition) 2020, 47(5), 513-521. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.Y.; Guo, W.; Liang, F.; Zhao, Q. Biostratigraphy characteristics and scientific meaning of the Wufeng and Longmaxi Formation black shales at Well Wei 202 of the Weiyuan shale gas field, Sichuan basin. Journal of Stratigraphy 2015, 39(3), 289-293. [CrossRef]

- Thistle, D.; Yingst, J.Y.; Fauchald, K. A deep-sea benthic community exposed to strong near-bottom currents on the Scotian Rise (western Atlantic). Marine Geology 1985, 66(1–4), 91-112. [CrossRef]

- Bádenas, B.; Pomar, L.; Aurell, M.; Morsilli, M. A facies model for internalites (internal wave deposits) on a gently sloping carbonate ramp (Upper Jurassic, Ricla, NE Spain). Sedimentary Geology 2012, 271-272, 44-57. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.D. Proposed classification of internal-wave and internal-tide deposits in deep-water environment. Geological Review 2013, 59(6), 1097-1109. [CrossRef]

- Mercier, M.J.; Garnier, N.B.; Dauxois, T. Reflection and diffraction of internal waves analyzed with the Hilbert transform. Physics of Fluids 2008, 20, 6601-6610. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.C.; Li, B.; Jiang, S.; Xiao, D.S.; Lu, S.F.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Gong, C.; Chen, L. Heterogeneity characterization of the lower Silurian Longmaxi marine shale in the Pengshui area, South China. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2018, 195, 250-266.

- Loucks, R.G. and Reed, R.M. Scanning-electron-microscope petrographic evidence for distinguishing organic- matter pores associated with depositional organic matter versus migrated organic matter in mudrocks. Gulf Coast Association of Geological Societies Journal 2014, 3, 51-60.

- Luan, G.Q.; Dong, C.M.; Ma, C.F.; Lin, C.Y.; Zhang, J.Y.; Lv, X.F.; Muhammad, A.Z. Pyrolysis simulation experiment study on diagenesis and evolution of organic-rich shale. Acta Sedimentologica Sinica 2016, 34(6), 1208-1216. [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.M.; Wan, M.X.; Yan, Y.X.; Zou, C.Y.; Liu, W.P.; Tian, C.; Yi, L.; Zhang, J. Reservoir diagenesis research of Silurian Longmaxi Formation in Sichuan Basin. Natural Gas Geoscience 2015, 26(8), 1547-1555.

- Zhao, D.F.; Guo, Y.H.; Yang, Y.J.; Wang, S.Y.; Mao, X.X.; Li, M. Shale reservoir diagenesis and its impacts on pores of the Lower Silurian Longmaxi Formation in southeastern Chongqing. Journal of Palaeogeography 2016, 18(5), 843-856. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.F.; Jiao, W.W.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, H.J.; Li, L.G.; Guo, Y.H.; Wang, G. Diagenesis of a shale reservoir and its influence on reservoir brittleness: Taking the deep shale of the Wufeng-Longmaxi Formation in western Chongqing as an example. Acta Sedimentologica Sinic 2021, 39(4), 811-825. [CrossRef]

- Cai, J. Study of shale reservoir diagenesis of the Wufeng—Longmaxi Formations in the Jiaoshiba area, Sichuan Basin. Jour. Mineral Petrol 2017, 37(4), 103-109. [CrossRef]

- Yi, T.; Zhou, W.; Yang, F.; Chen, W.L.; Zhang, H.T.; Xu, H.; Liu, R.Y.; Zhao, X.; Jiang, K. Types and characteristics of quartz in shale gas reservoirs of the Longmaxi Formation, Sichuan Basin, China. Acta Mineralogica Sinica 2020, 40(2), 127-136. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.H.; Jin, Z.J. Mudstone diagenesis: Research advances and prospects. Acta Sedimentologica Sinica 2021, 39(1), 58-72. [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.Y.; Hu, Z.Q.; Bao, H.Y.; Wu, J.; Du, W.; Wang, P.W.; Peng, Z.Y.; Lu, T. Diagenetic evolution of key minerals and its controls on reservoir quality of Upper Ordovician Wufeng-Lower Silurian Longmaxi shale of Sichuan Basin. Petroleum Geology & Experiment 2021, 43(6), 996-1005.

- Li, Y.; Shi, X.W.; Luo, C.; Wu, W.; Yang, X.; Zhu, Y.Q.; Tian, C.; Zhong, K.S.; Li, Y.Y.; Xv, H.; Ran, B. Impact of different diagenetic minerals on shale reservoirs in Wufeng-Longmaxi Formation in southern Sichuan Basin. Journal of Chengdu University of Technology (Science & Technology Edition) 2024, 51(5), 745-757+771. [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.X.; Zhang, P.H.; Liang, J.; Chen, J.W.; Meng, X.H.; Fu, Y.L.; Bao, Y.J. Biogenic microcrystalline quartz and its influence on pore development in marine shale reservoirs. Acta Sedimentologica Sinica 2024, 42(5), 1738-1752. [CrossRef]

- Mei, J.F.; Liang, C.; Cao, Y.C.; Han, Y. Types, genesis and significance of quartz in shales. Journal of Palaeogeography (Chinese Edition) 2024, 26(2), 487-501. [CrossRef]

- Ramseyer, K.; Amthor, J.E.; Matter, A.; Pettke, T.; Wille, M.; Fallick, A.E. Primary silica precipitate at the Precambrian/Cambrian boundary in the South Oman Salt Basin, sultanate of Oman. Marine and Petroleum Geology 2013, 39(1), 187-197. [CrossRef]

- Rajaibi, I.M.A.; Hollis, C.; Macquaker, J.H. Origin and variability of a terminal Proterozoic primary silica precipitate, Athel Silicilyte, South Oman Salt Basin, sultanate of Oman. Sedimentology 2015, 62(3), 793-825.

- Longman, M.; Drake, W.R.; Milliken, K.L.; Olson, T. A comparison of silica diagenesis in the Devonian Woodford shale (Central Basin Platform, West Texas) and Cretaceous Mowry shale (Powder River Basin, Wyoming) // Camp W K, Milliken K L, Taylor K. Mudstone diagenesis: research perspectives for shale hydrocarbon reservoirs, seals, and source rocks. Tulsa, Oklahoma, USA and Broken Arrow, Oklahoma, USA: AAPG and SEPM 2019, 49-67.

- Zhao, J.H.; Jin, Z.J.; Jin, Z.K.; Wen, X.; Geng, Y.K.; Yan, C.N. The genesis of quartz in Wufeng-Longmaxi gas shales, Sichuan Basin. Natural Gas Geoscience 2016, 27(2), 377-386.

- Chen, H.Y.; Lu, L.F.; Liu, W.X.; Shen, B.J.; Yu, L.J.; Yang, Y.F. Pore network changes in opaline siliceous shale during diagenesis. Petroleum Geology & Experiment 2017, 39(3), 341-347. [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Dong, D.Z.; Li, M.; Sun, S.S.; Guan, Q.Z.; Zhang, S.R. Quartz genesis in organic-rich shale and its indicative significance to reservoir quality: A case study on the first submember of the first Member of Lower Silurian Longmaxi Formation in the southeastern Sichuan Basin and its periphery. Natural Gas Industry 2021, 41(2), 65-74. [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.F.; Liu, W.X.; Wei, Z.H.; Pan, A.Y.; Zhang, Q.Z.; Tenger. Diagenesis of the Silurian Shale, Sichuan Basin: Focus on pore development and preservation. Acta Sedimentologica Sinica 2022, 40(1), 73-87. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Sedimentary environment of the Longmaxi Formation in the Sichuan Basin and its peripheral area modified from [

18]. A bay opened northward and was enclosed by the Central Sichuan paleouplift, Central Guizhou paleouplift, and Jiangnan–Xuefeng paleouplift; this consisted of a shallow-water shelf, a deep-water shelf, and a few of underwater highlands [

23]. Approximately 20 m to 80 m of black shale was deposited in the deep-water shelf [

24]. Sampling Wells W2 and W3 were located in the narrow deep-water shelf between the Central Sichuan paleouplift and an underwater highland.

Figure 1.

Sedimentary environment of the Longmaxi Formation in the Sichuan Basin and its peripheral area modified from [

18]. A bay opened northward and was enclosed by the Central Sichuan paleouplift, Central Guizhou paleouplift, and Jiangnan–Xuefeng paleouplift; this consisted of a shallow-water shelf, a deep-water shelf, and a few of underwater highlands [

23]. Approximately 20 m to 80 m of black shale was deposited in the deep-water shelf [

24]. Sampling Wells W2 and W3 were located in the narrow deep-water shelf between the Central Sichuan paleouplift and an underwater highland.

Figure 2.

Burial history of the Longmaxi Formation in the Weiyuan area, Sichuan Basin modified from [

18]. When the Longmaxi Formation had a burial depth of less than 1500 m and a geothermal temperature of less than 60 ℃, SOM was converted into Type Ⅰ–Ⅱ kerogen [

35,

36,

37]. When the Longmaxi Formation had burial depths of 1500–2500 m and geothermal temperatures of 60–90 ℃, the kerogens were converted into the amorphous pre-oil bitumen. When the Longmaxi Formation had 2500–3500 m burial depths and geothermal temperatures of 90–120 ℃, the pre-oil bitumen was converted into the solid bitumen and the oil. When the Longmaxi Formation had burial depths of 3500–6500 m and geothermal temperatures of 120–210 ℃, the solid bitumen and the oil were converted into the pyrobitumen and the hydrocarbon gas. In the Cretaceous, the maximum burial depth of the Longmaxi Formation was approximately 6500 m [

19]. Since the Cenozoic, the thickness that eroded during the uplift process was generally 2000–4000 m. At present, the burial depth of the Longmaxi Formation is generally 2000–5500 m [

19].

Figure 2.

Burial history of the Longmaxi Formation in the Weiyuan area, Sichuan Basin modified from [

18]. When the Longmaxi Formation had a burial depth of less than 1500 m and a geothermal temperature of less than 60 ℃, SOM was converted into Type Ⅰ–Ⅱ kerogen [

35,

36,

37]. When the Longmaxi Formation had burial depths of 1500–2500 m and geothermal temperatures of 60–90 ℃, the kerogens were converted into the amorphous pre-oil bitumen. When the Longmaxi Formation had 2500–3500 m burial depths and geothermal temperatures of 90–120 ℃, the pre-oil bitumen was converted into the solid bitumen and the oil. When the Longmaxi Formation had burial depths of 3500–6500 m and geothermal temperatures of 120–210 ℃, the solid bitumen and the oil were converted into the pyrobitumen and the hydrocarbon gas. In the Cretaceous, the maximum burial depth of the Longmaxi Formation was approximately 6500 m [

19]. Since the Cenozoic, the thickness that eroded during the uplift process was generally 2000–4000 m. At present, the burial depth of the Longmaxi Formation is generally 2000–5500 m [

19].

Figure 3.

TOC and the bulk rock analysis data profiles of the Wufeng–Longmaxi Formations of sampling wells. (a) Sampling Well W2. (b) Sampling Well W3.

Figure 3.

TOC and the bulk rock analysis data profiles of the Wufeng–Longmaxi Formations of sampling wells. (a) Sampling Well W2. (b) Sampling Well W3.

Figure 4.

Nano-resolution images of quartz. (a) The framework of the siliceous shale studied is mainly composed of the porous mud-grade quartz particles and the porous silt-grade quartz particles. The porous mud-grade quartz particles and the porous silt-grade quartz particles both appear in the form of aggregate, and the the porous mud-grade quartz aggregate are nested within the porous silt-grade quartz aggregate. The OMs fill in the voids among these aggregates. (b) The OMs fill in the voids among the porous mud-grade quartz aggregate whose particle diameters range from 1 μm to 4 μm. (c–g) The silt-grade quartz particles with the largest size of 30 μm appear in the form of the porous quartz particels and the nonporous quartz particles. A mud-grade quartz rim exists on the surface of each silt-grade quartz particle, but the rim at the contact locations between the calcite particles and the silt-grade quartz particles (blue arrows) lack. Sporadic clays (bluered arrows) are between the nonporous silt-grade quartz particle and the mud-grade quartz rim. (h) The porous mud-grade quartz particles rim the fecal pellet. (i, j) Sporadic clays (red arrows) are between the nonporous silt-grade quartz particle and the porous mud-grade quartz rim. (k, l) The clay rim is between the nonporous silt-grade quartz particle and its porous mud-grade quartz rim. (m–p) The porous mud-grade quartz rim with no clay develops on the surface of the porous silt-grade quartz particle.

Figure 4.

Nano-resolution images of quartz. (a) The framework of the siliceous shale studied is mainly composed of the porous mud-grade quartz particles and the porous silt-grade quartz particles. The porous mud-grade quartz particles and the porous silt-grade quartz particles both appear in the form of aggregate, and the the porous mud-grade quartz aggregate are nested within the porous silt-grade quartz aggregate. The OMs fill in the voids among these aggregates. (b) The OMs fill in the voids among the porous mud-grade quartz aggregate whose particle diameters range from 1 μm to 4 μm. (c–g) The silt-grade quartz particles with the largest size of 30 μm appear in the form of the porous quartz particels and the nonporous quartz particles. A mud-grade quartz rim exists on the surface of each silt-grade quartz particle, but the rim at the contact locations between the calcite particles and the silt-grade quartz particles (blue arrows) lack. Sporadic clays (bluered arrows) are between the nonporous silt-grade quartz particle and the mud-grade quartz rim. (h) The porous mud-grade quartz particles rim the fecal pellet. (i, j) Sporadic clays (red arrows) are between the nonporous silt-grade quartz particle and the porous mud-grade quartz rim. (k, l) The clay rim is between the nonporous silt-grade quartz particle and its porous mud-grade quartz rim. (m–p) The porous mud-grade quartz rim with no clay develops on the surface of the porous silt-grade quartz particle.

Figure 5.

Nano-resolution images of calcite, dolomite, pyrite, and clay. (a) Porous mud-grade quartzs (red arrows) fill in the dissolution pores of the calcite. (b, c) An overgrowth pyrite framboid, nonporous OM, and porous mud-grade quartz aggregate (blue arrows) occurs in the dissolution pores of the rhombic dolomite. (d) An overgrowth pyrite framboid exists among the porous mud-quartz aggregate. (e, f) Sporadic porous mud-grade quartz particles (red arrows) are in the irregular pyrite framboids. (g) Sporadic flaky clays occur among the quartz aggregate. (h, i) A flaky clay is encased in the porous OM. (j) Sporadic flaky clays are in the nonporous OM.

Figure 5.

Nano-resolution images of calcite, dolomite, pyrite, and clay. (a) Porous mud-grade quartzs (red arrows) fill in the dissolution pores of the calcite. (b, c) An overgrowth pyrite framboid, nonporous OM, and porous mud-grade quartz aggregate (blue arrows) occurs in the dissolution pores of the rhombic dolomite. (d) An overgrowth pyrite framboid exists among the porous mud-quartz aggregate. (e, f) Sporadic porous mud-grade quartz particles (red arrows) are in the irregular pyrite framboids. (g) Sporadic flaky clays occur among the quartz aggregate. (h, i) A flaky clay is encased in the porous OM. (j) Sporadic flaky clays are in the nonporous OM.

Figure 6.

Nano-resolution images of OMs. (a, b) Porous OMs occur in voids among the porous quartz aggregate. (c, d) Nonporous OMs are in voids among the porous quartz aggregate. (e, f) The porous (red arrows) and nonporous (blue arrows) OMs coexist in in a void among the porous aggregate. The thickness of the quartz overgrowth contacting with the nonporous OM is bigger than that of the quartz overgrowth contacting with the porous OM. (g) A nonporous OM fills in the secondary pore in the fecal pellet. (h) A porous OM, coming into direct contact with that in the void among the porous quartz aggregate, fills in in the secondary pore in the fecal pellet. (i) A nonporous OM, coming into direct contact with that in the void among the mud-grade quartz aggregate, fills in the secondary pore of the mud-grade quartz aggregate.

Figure 6.

Nano-resolution images of OMs. (a, b) Porous OMs occur in voids among the porous quartz aggregate. (c, d) Nonporous OMs are in voids among the porous quartz aggregate. (e, f) The porous (red arrows) and nonporous (blue arrows) OMs coexist in in a void among the porous aggregate. The thickness of the quartz overgrowth contacting with the nonporous OM is bigger than that of the quartz overgrowth contacting with the porous OM. (g) A nonporous OM fills in the secondary pore in the fecal pellet. (h) A porous OM, coming into direct contact with that in the void among the porous quartz aggregate, fills in in the secondary pore in the fecal pellet. (i) A nonporous OM, coming into direct contact with that in the void among the mud-grade quartz aggregate, fills in the secondary pore of the mud-grade quartz aggregate.

Figure 7.

Dip angle rose diagrams of elliptical and elongated silt-grade quartz particles in each shale sample. In each sample, the dip angles of these quartz clastics are generally less than 30°, but their dip directions are the opposite. (a) Well W2, 2572.87 m. (b) Well W2, 2573.82 m. (c) Well W2, 2852.76 m; and (d) Well W2, 2853.10 m.

Figure 7.

Dip angle rose diagrams of elliptical and elongated silt-grade quartz particles in each shale sample. In each sample, the dip angles of these quartz clastics are generally less than 30°, but their dip directions are the opposite. (a) Well W2, 2572.87 m. (b) Well W2, 2573.82 m. (c) Well W2, 2852.76 m; and (d) Well W2, 2853.10 m.

Figure 8.

Pattern of the sedimentation–diagenetic processes of some siliceous shales studied of the Longmaxi Formation in the Weiyuan area, Sichuan Basin.

Figure 8.

Pattern of the sedimentation–diagenetic processes of some siliceous shales studied of the Longmaxi Formation in the Weiyuan area, Sichuan Basin.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).