I. Introduction

With the rapid development of information technology, social networking platforms have become essential mediums for daily communication, information sharing, and opinion expression [

1]. These platforms carry vast amounts of unstructured text data with potential value. Social texts are rich in entity information and often closely follow social events, reflecting public sentiment. Therefore, they hold great application value in areas such as opinion monitoring, information recommendation, and intelligent customer service. However, compared to traditional news or encyclopedic texts, social texts are more colloquial and informal [

2]. They contain many abbreviations, emojis, and spelling errors, which pose significant challenges to text understanding and processing, especially for the task of Named Entity Recognition (NER).

Named Entity Recognition, as a fundamental task in natural language processing, aims to identify entities with specific semantic categories from texts, such as person names, locations, and organization names [

3]. In traditional text processing, rule-based and statistical learning methods were once dominant. With the evolution of deep learning, especially the widespread adoption of Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and their variants, NER has achieved notable progress. Among them, the Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory network (BiLSTM), which captures contextual semantics, combined with Conditional Random Fields (CRF) for optimal sequence labeling, has become a mainstream modeling framework. However, this model still suffers from performance instability and limited robustness when dealing with informal language and complex context dependencies in social texts. Therefore, improving the performance of BiLSTM-CRF models under the context of social texts remains a key research issue [

4].

Social text mining, as an emerging research direction, focuses on extracting structured information, semantic patterns, and user behavior features from social media. By integrating social context, user interaction networks, and topic aggregation features, it is possible to compensate for semantic gaps in raw text and enhance the performance of downstream tasks. Introducing social text mining into NER helps build more context-aware representation models. It also strengthens the model’s ability to handle informal expressions and domain-specific language, providing new perspectives for improving generalization and stability. Hence, the integration of BiLSTM-CRF models with social text mining has both theoretical significance and practical value.

From a practical perspective, improving the accuracy of NER in social texts not only enhances fine-grained information extraction in opinion analysis systems but also has direct implications for disaster warning, emergency response, and public safety monitoring. For example, during disease outbreaks, accurate identification of locations, transmission nodes, and related persons can significantly impact data modeling and policy-making efficiency. Similarly, in scenarios such as financial risk control and content regulation, timely recognition of high-risk entities is a crucial part of risk alert mechanisms. Therefore, developing a robust and domain-adaptive NER method for social text scenarios is essential for advancing intelligent information processing systems.

In summary, as social media increasingly permeates various aspects of society, exploring NER methods that integrate deep sequential models and social semantic mining mechanisms is aligned with cutting-edge trends in natural language processing. It also addresses the urgent needs of intelligent social applications. This paper investigates the modeling mechanisms of BiLSTM-CRF and its integration with social text mining. The goal is to build an NER framework with both semantic understanding and social context awareness, providing theoretical support and methodological reference for deep social data mining and intelligent applications.

II. Prior Studies and Technical Foundations

In recent years, the integration of deep learning architectures has significantly advanced the performance of Named Entity Recognition (NER) tasks, particularly when adapting to informal and noisy social text environments. Foundational works on pre-trained language models and fine-tuning mechanisms have inspired more adaptive approaches to sequence labeling. For instance, methods such as model distillation and efficient fine-tuning [

5] provide insights into how lighter models can maintain robust contextual understanding—a principle that informs the scalability and efficiency considerations in our proposed BiLSTM-CRF framework.

Deep contextual models, especially those augmented with few-shot learning strategies, have shown great promise in extracting entities from sparse or noisy data. These techniques align closely with our study’s goal of enhancing recognition under data constraints and ambiguity, particularly in social media contexts [

6]. Meanwhile, explorations into hierarchical term representations within large language models [

7] highlight the importance of understanding complex semantic relationships, which our model approaches through bidirectional LSTM encoding and CRF decoding for global sequence optimization.

Recent efforts in enriching language models with external semantic cues—such as retrieval-based mechanisms—further echo our approach of incorporating multi-source social features. For instance, joint modeling with external knowledge retrieval has demonstrated improvements in handling informal or ambiguous text expressions [

8], which supports our incorporation of user interaction and topic metadata as additional semantic signals. Similarly, domain-specific transformer models [

9] contribute to the broader discussion of embedding social semantics into entity extraction tasks, which our study operationalizes through feature fusion techniques.

In support of robust representation learning, advancements in self-supervised learning offer transferable mechanisms for semantic alignment and representation optimization. Contrastive and variational methods [

10], though originally used in other modalities, reinforce the conceptual underpinning of our feature integration strategy—capturing intrinsic data structure without heavy reliance on labeled supervision. Additionally, graph neural network models provide further methodological insight into relational feature extraction, relevant to our modeling of user interaction networks [

11]. From the perspective of data-driven personalization, recommendation frameworks leveraging attention mechanisms [

12] [

13] illustrate how structural features can be dynamically weighted and fused—an idea reflected in our feature concatenation design for social text mining. Although originally applied to recommendation systems, these techniques underscore the general value of attention-guided feature interaction in downstream tasks like NER.

Other works on segmentation and temporal modeling provide technical strategies to enhance boundary recognition and dynamic sequence understanding. These include deep frameworks for boundary-aware classification [

14] and interpretable time-series modeling [

15], both of which align with our objective of refining entity boundary detection in unstructured text.

Moreover, system-level techniques such as federated learning for distributed model efficiency [

16], reinforcement learning for scheduling optimization [

17], and activity recognition through spatiotemporal modeling [

18] offer broader technical insights into adaptive and robust learning in complex, real-world environments. These methodologies, although peripheral in application, influence our model’s robustness design against noisy and context-rich data. Lastly, advanced adaptation strategies such as low-rank optimization (LoRA) [

19] point to future directions in efficient model transformation and could inspire enhancements to our fusion mechanism beyond simple concatenation—highlighting the evolving landscape of scalable, domain-adaptive learning.

III. Proposed Framework and Feature Integration

In this study, in order to improve the accuracy and robustness of named entity recognition in social text, a method framework that integrates the BiLSTM-CRF model and social text mining features is proposed. The overall structure consists of three parts: first, the distributed representation of the input text is obtained through the word embedding layer, then the bidirectional long short-term memory network (BiLSTM) is introduced to model the context, and finally the conditional random field (CRF) [

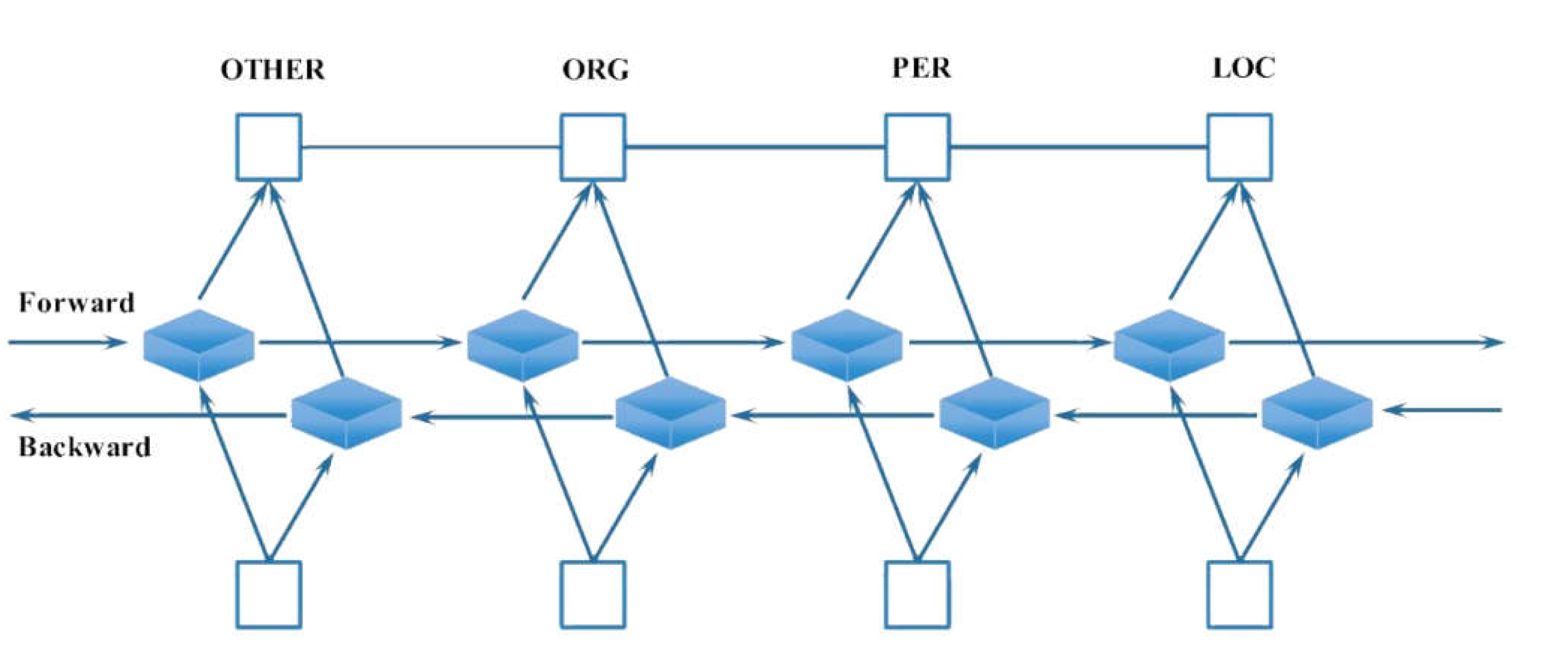

20] is combined to globally decode the label sequence. The model architecture is shown in

Figure 1.

Figure 1 shows the network structure of the named entity recognition model proposed in this paper, which is composed of a bidirectional long short-term memory network (BiLSTM) and a conditional random field (CRF). The model first extracts the contextual semantic information of each word in the sequence through forward and backward LSTM units to form a context-aware representation; then the features of the BiLSTM output are passed to the CRF layer, and the global optimal decoding of the complete label sequence is achieved by modeling the transfer relationship between labels. At the output layer, the model labels each word as its entity category, such as LOC, PER, ORG, or OTHER, based on the prediction results, thereby achieving accurate recognition of named entities in social texts.

In the input layer, assume that an input sequence of length T is , and its corresponding word vector is represented by , where represents the embedding vector of the t-th word and d is the word vector dimension. Word embedding can come from a pre-trained model such as Word2Vec or an embedding model dedicated to social text to improve the representation ability of domain vocabulary.

In the sequence modeling layer, BiLSTM processes the sequence in parallel through two LSTM units, forward and backward, to capture the bidirectional dependency information of the context. For any time step t, the hidden state of the forward LSTM is , and the hidden state of the backward LSTM is . The two are concatenated to form the final context representation:

Where represents the hidden layer dimension of the unidirectional LSTM. Based on this feature representation, this study further introduces social text features, including node degree centrality in the user relationship graph, TF-IDF representation of topic tags, and semantic category embedding based on contextual clustering, which are combined with to form an enhanced representation through splicing, namely:

Where represents the social semantics enhanced feature vector. This strategy enables the model to make full use of non-textual contextual semantic information and improve the tolerance and discrimination of non-standard expressions.

In the label prediction stage, the conditional random field (CRF) is used to model the entire label sequence. For the sequence label , the score function is defined as:

Among them, the first term is the emission score between the label and the current feature, the second term is the transfer score between labels, and represents the score of transferring from label i to label j. The prediction of the entire sequence is achieved by maximizing the probability:

The Viterbi algorithm is used for decoding to obtain the optimal label path. To optimize the model parameters, the log-likelihood objective function is maximized during training:

The above joint modeling process is trained under an end-to-end framework, and social features and contextual representations complement each other and jointly drive the improvement of entity recognition performance.

IV. Empirical Evaluation and Analysis

A. Datasets

This study employs the Twitter Named Entity Recognition (NER) dataset as the experimental data source to assess the performance of the proposed model in recognizing named entities in social text contexts. The dataset comprises unstructured, concise texts gathered from the Twitter platform. It encompasses a wide range of linguistic expressions, substantial noise levels, and intricate entity types, which accurately reflect the complexities encountered in NER tasks involving social texts.

The dataset contains 2,400 manually annotated English tweets. Each tweet is labeled with entity information. The entity types include person names (PER), locations (LOC), organizations (ORG), product names (PRODUCT), and unrecognized entities (OTHER). Compared to traditional news texts, tweets have looser grammatical structures. They often include abbreviations, slang, emojis, and irregular spellings. These characteristics make the dataset a strong benchmark for testing the robustness and generalization of NER algorithms in real-world complex scenarios. During data preprocessing, the original texts were tokenized. Special characters were removed, and abbreviations were standardized. At the same time, emojis and symbolic features relevant to semantic understanding were preserved. Based on the original train-validation-test split, 80% of the samples were used for training, 10% for validation, and 10% for final testing. This ensured fairness and comparability in the evaluation results.

B. Experimental Results

This paper first gives a comparative experiment on the recognition effect of different word embedding methods on NER tasks. The experimental results are shown in

Table 1.

As shown in

Table 1, different word embedding methods exhibit notable differences in NER performance. Traditional static embeddings such as Word2Vec and GloVe show stable results across evaluation metrics. They achieve F1 scores of 83.80% and 85.12%, respectively. This indicates their ability to represent standard text semantics to some extent. However, these methods fail to effectively capture contextual ambiguity and semantic variation. As a result, their performance is limited when dealing with informal expressions and complex entity relations in social texts. FastText, by incorporating subword information, outperforms Word2Vec and GloVe in terms of recognition accuracy. It achieves an impressive F1 score of 87.22%, showcasing superior robustness to common social text phenomena like word variations and spelling errors. Moreover, its recall rate surpasses that of other static embeddings, reaching an impressive 88.65%. Notably, after fine-tuning, its F1 score further increases to 91.78%. These results demonstrate that BERT effectively models the semantic features of words within their specific contexts. Consequently, it enhances the model’s ability to distinguish entity boundaries and types in complex texts. In summary, the use of dynamic, context-aware BERT embeddings significantly improves overall NER performance in social text scenarios. Furthermore, this paper gives an evaluation of the effect of multi-source social feature fusion, and the experimental results are shown in

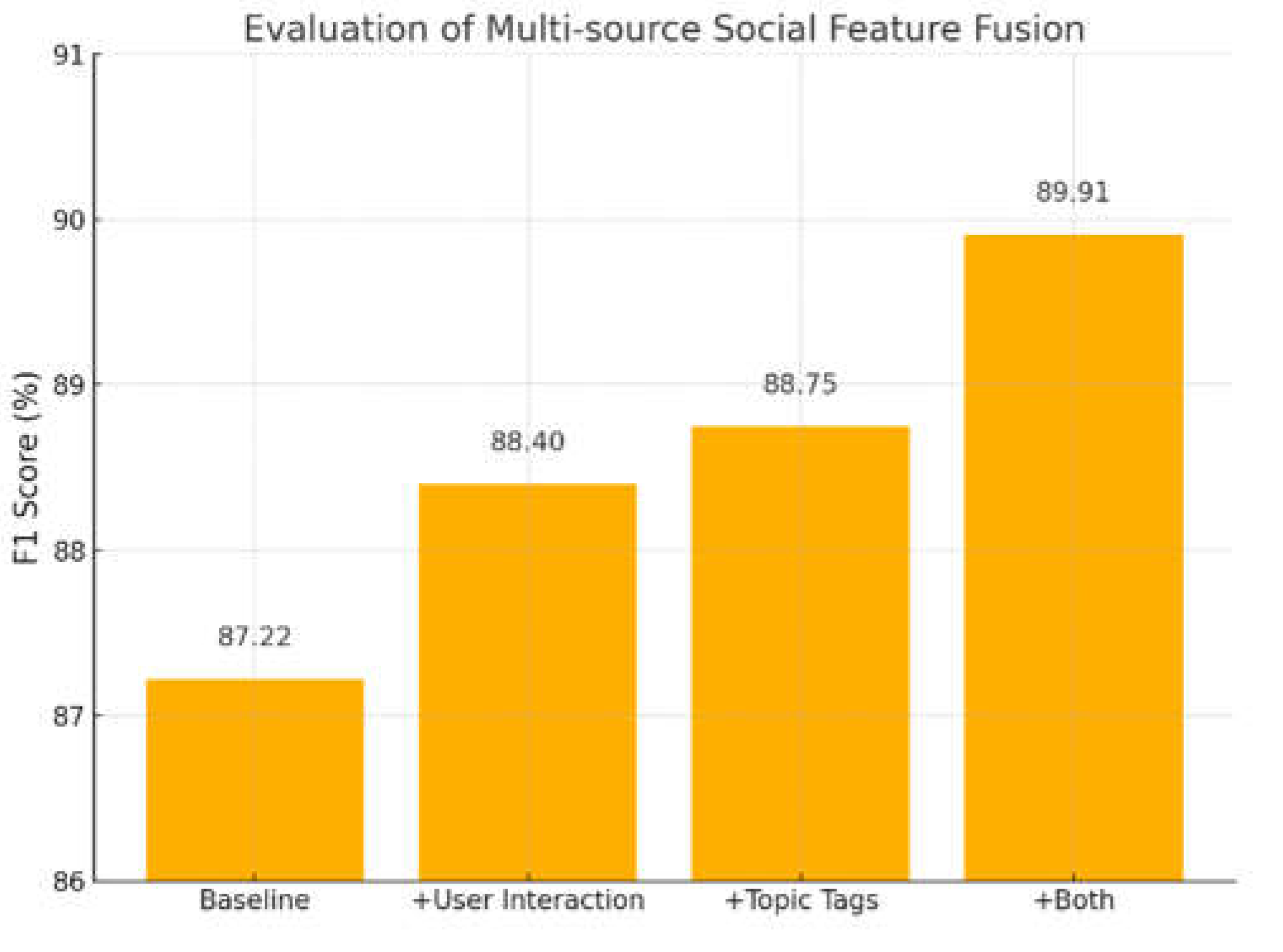

Figure 1.

Figure 2 presents the impact of multi-source social feature fusion on Named Entity Recognition (NER) performance. As evident, the baseline model without any social features achieves an F1 score of 87.22%, which serves as a reference point. Gradually introducing social features significantly improves the model’s performance. This suggests that social semantic information plays a positive role in enhancing the model’s recognition abilities.

When user interaction features are added alone, the F1 score increases to 88.40%. This suggests that user behavior patterns help in identifying entity boundaries and types. After incorporating topic labels, the F1 score further rises to 88.75%. This shows that aggregated topic information strengthens the model’s contextual perception, especially for topic-driven social texts. Most notably, when both types of social features are combined, the model reaches the highest F1 score of 89.91%. The result confirms the complementarity and fusion potential of multi-source social features. Finally, this paper gives an experiment on the effect of different sequence lengths on recognition accuracy. The experimental results are shown in

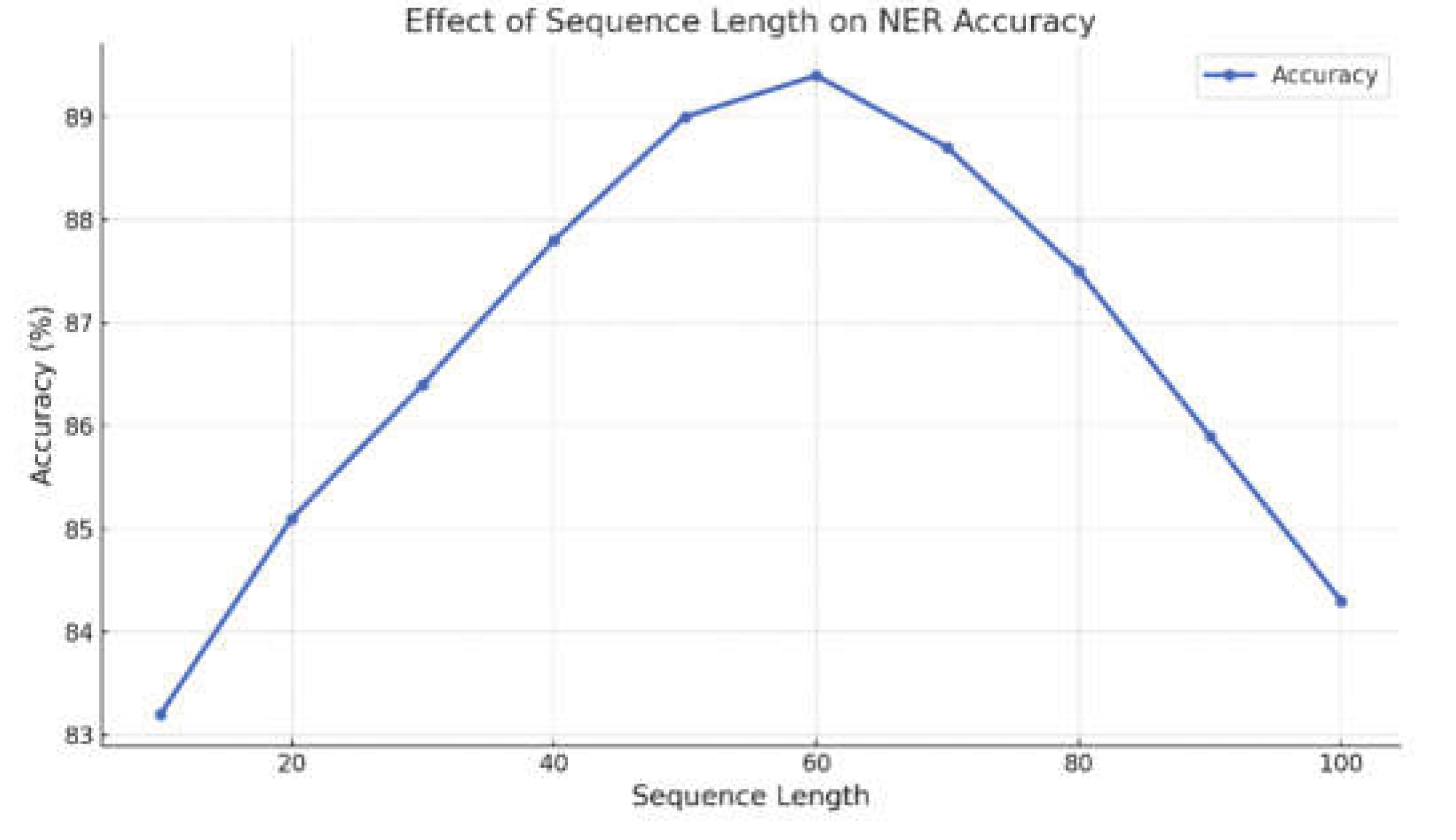

Figure 3.

Figure 3 illustrates the influence of varying input sequence lengths on NER accuracy. The accuracy gradually increases as the sequence length spans from 10 to 30. This suggests that as the textual information accumulates, the model progressively extracts more contextual clues, enhancing its recognition capabilities. During this phase, the model transitions from extracting local word-level features to grasping short phrase-level semantics, resulting in a significant performance improvement.

When the sequence length reaches 60, the model reaches its peak performance, achieving an accuracy of around 89.4%. At this point, the input contains ample information with minimal redundancy. The model effectively captures contextual semantics surrounding entities and distinguishes between various entity types. However, as the sequence length increases, the accuracy significantly drops. The decline is particularly sharp at lengths of 90 and 100, indicating that the model struggles with dispersed context and diluted key information in longer texts.

Overall, the results indicate that sequence length has a substantial impact on NER performance, and there exists an optimal length range. In this study, a length of 60 provides the best balance between feature representation and semantic aggregation. Therefore, in social text NER tasks, controlling input sequence length is crucial. It not only improves recognition accuracy but also reduces computational complexity and the risk of overfitting.

V. Conclusions

This paper proposes a method framework for named entity recognition in social text scenarios, which integrates the BiLSTM-CRF model with multi-source social text mining features. Based on capturing rich contextual semantic information, the method further incorporates social semantic features such as user interactions and topic labels. This effectively enhances the model’s ability to recognize informal expressions, noisy content, and semantically ambiguous entities. Experimental results show that the proposed model outperforms traditional models across multiple evaluation metrics, with a particularly notable improvement in F1 score. Through comparative experiments on different word embedding methods, social feature fusion strategies, and input sequence lengths, this study analyzes the impact of each factor on NER performance. The findings validate the effectiveness of dynamic contextual embeddings and multi-source social semantics in improving model generalization and robustness. Moreover, the experiments reveal that the model performs best within a specific range of input lengths. This suggests that, in practical deployment, the structure and dimensionality of input features should be carefully controlled to achieve optimal results.

Despite the promising performance of the proposed approach in social text environments, several challenges remain. These include improving cross-domain transferability, adapting to multilingual or multimodal inputs, and enhancing recognition for low-resource entity categories. Additionally, the current fusion strategy is mainly based on simple concatenation, lacking deeper semantic alignment mechanisms. Future research can proceed in several directions. First, integrating pre-trained language models with graph neural network structures may further enhance the joint modeling of social network structure and text semantics. Second, more refined social context modeling strategies can be explored, such as user behavior history modeling and entity co-occurrence graph construction. Third, extending the study to multilingual and multi-platform settings can improve the model’s transferability and general applicability, supporting complex social applications such as opinion monitoring, event extraction, and intelligent recommendation.

References

- Carvallo, T. Quiroga, C. Aspillaga, et al., “Unveiling Social Media Comments with a Novel Named Entity Recognition System for Identity Groups,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.13011, 2024.

- M. Šeleng, Š. Dlugolinský, M. Staňo, et al., “Model for named entity extraction from short fire event-related texts,” Procedia Computer Science, vol. 256, pp. 557-564, 2025.

- Belbekri, W. Bouarroudj, F. Benchikha, et al., “Semantics-based oversampling for imbalanced named entity recognition datasets using Word2Vec embeddings,” Intelligent Data Analysis, 2025, Art. no. 1088467X251322099.

- M. R. Prusty, A. K. Sinha, S. S. K. Singh, et al., “Named Entity Recognition Based Neural Network Framework for Stock Trend Prediction Using Latent Dirichlet Allocation,” Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering, 2025, pp. 1–14.

- Kai, L. Zhu and J. Gong, “Efficient Compression of Large Language Models with Distillation and Fine-Tuning,” Journal of Computer Science and Software Applications, vol. 3, no. 4, pp. 30–38, 2023.

- X. Wang, G. Liu, B. Zhu, J. He, H. Zheng and H. arXiv:2504.04385, 2025.

- G. Cai, J. Gong, J. Du, H. Liu and A. Kai, “Investigating Hierarchical Term Relationships in Large Language Models,” Journal of Computer Science and Software Applications, vol. 5, no. 4, 2025.

- Z. Yu, S. Z. Yu, S. Wang, N. Jiang, W. Huang, X. Han and J. arXiv:2504.02310, 2025.

- X. Wang, “Medical Entity-Driven Analysis of Insurance Claims Using a Multimodal Transformer Model,” Journal of Computer Technology and Software, vol. 4, no. 3, 2025.

- Y. Liang, L. Dai, S. Shi, M. Dai, J. Du and H. arXiv:2504.04032, 2025.

- J. Wei, Y. Liu, X. Huang, X. Zhang, W. Liu and X. Yan, “Self-Supervised Graph Neural Networks for Enhanced Feature Extraction in Heterogeneous Information Networks,” 2024 5th International Conference on Machine Learning and Computer Application (ICMLCA), pp. 272-276, 2024.

- Liang, “A Graph Attention-Based Recommendation Framework for Sparse User-Item Interactions,” Journal of Computer Science and Software Applications, vol. 5, no. 4, 2025.

- L. Zhu, “Deep Learning for Cross-Domain Recommendation with Spatial-Channel Attention,” Journal of Computer Science and Software Applications, vol. 5, no. 4, 2025.

- T. An, W. Huang, D. Xu, Q. He, J. Hu and Y. arXiv:2503.22050, 2025.

- X. Yan, Y. Jiang, W. Liu, D. Yi and J. Wei, “Transforming Multidimensional Time Series into Interpretable Event Sequences for Advanced Data Mining,” 2024 5th International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Human-Computer Interaction (ICHCI), pp. 126-130, 2024.

- Y. Wang, “Optimizing Distributed Computing Resources with Federated Learning: Task Scheduling and Communication Efficiency,” Journal of Computer Technology and Software, vol. 4, no. 3, 2025.

- J. Wei, “Reinforcement Learning Approach to Traffic Scheduling in Complex Data Center Topologies,” Journal of Computer Technology and Software, vol. 4, no. 3, 2025.

- J. Zhan, “Single-Device Human Activity Recognition Based on Spatiotemporal Feature Learning Networks,” Transactions on Computational and Scientific Methods, vol. 5, no. 3, 2025.

- Y. Wang, Z. Fang, Y. Deng, L. Zhu, Y. Duan and Y. Peng, “Revisiting LoRA: A Smarter Low-Rank Approach for Efficient Model Adaptation,” unpublished.

- Y. Chen, et al., “Named entity recognition from Chinese adverse drug event reports with lexical feature based BiLSTM-CRF and tri-training,” Journal of Biomedical Informatics, vol. 96, p. 103252, 2019.

- S. Arslan, “Application of BiLSTM-CRF model with different embeddings for product name extraction in unstructured Turkish text,” Neural Computing and Applications, vol. 36, no. 15, pp. 8371–8382, 2024.

- H. Liu, et al., “TFM: A triple fusion module for integrating lexicon information in Chinese named entity recognition,” Neural Processing Letters, vol. 54, no. 4, pp. 3425–3442, 2022.

- W. Li, et al., “UD_BBC: Named entity recognition in social network combined BERT-BiLSTM-CRF with active learning,” Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence, vol. 116, p. 105460, 2022.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).