Submitted:

13 May 2025

Posted:

14 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Quantifying the Actuarial Disconnect

- Systematic underpricing of longevity risk: When mortality models fail to capture investment-driven acceleration, annuities and pension products become systematically underpriced, creating long-term solvency risks.

- Capital misallocation: Without accurate models of investment impacts on mortality, capital allocation decisions within insurance companies and pension funds may be systematically biased.

- Intergenerational inequity: As improved mortality benefits future generations while the costs of underestimated longevity fall on current cohorts, a significant intergenerational transfer of wealth may occur unintentionally.

- RQ1: How do significant capital flows into longevity science quantitatively alter mortality improvement trajectories beyond traditional actuarial assumptions?

- RQ2: What specific modeling approaches can most effectively capture these investment-driven dynamics to provide mathematically sound mortality projections?

- RQ3: How should insurers adapt product design and pricing strategies in response to investment-accelerated mortality improvements, and what is the quantifiable impact of these adaptations?

2. The Longevity Investment Landscape

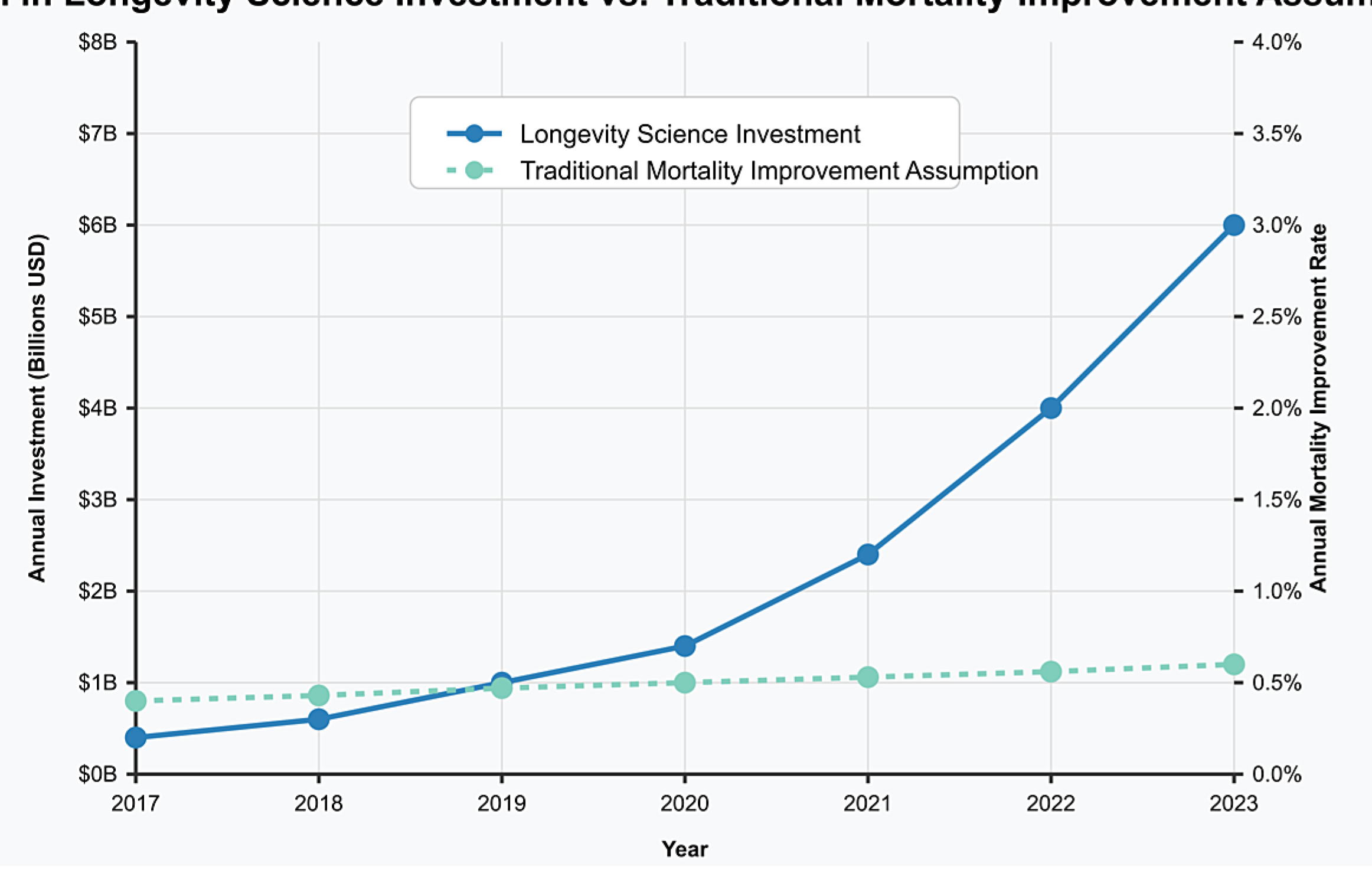

2.1. Investment Trends in Longevity Science

2.2. Precision Biological Reprogramming

2.3. AI-Accelerated Drug Discovery

2.4. Real-Time Biological Monitoring

2.5. Investor Expectations and Time Horizons

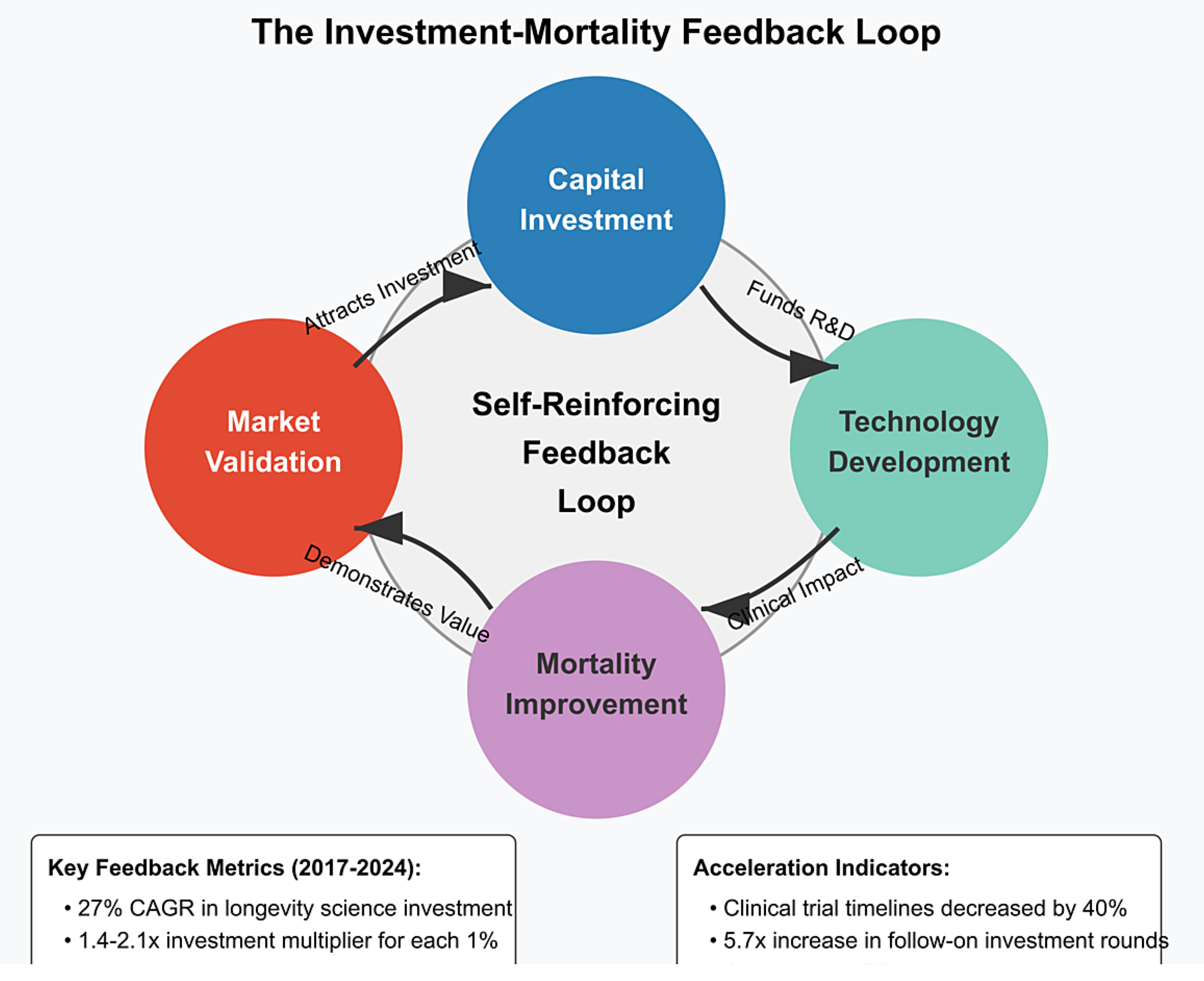

2.6. The Investment-Mortality Feedback Loop

- Proof-of-concept validation: Initial investment enables proof-of-concept studies that demonstrate efficacy, attracting larger follow-on investments. The median follow-on investment round for longevity companies increased from $15 million in 2017 to $68 million in 2024 [1].

- Regulatory pathway validation: As early investments establish clear regulatory pathways, subsequent investment risk decreases. The number of longevity-focused companies with FDA-approved clinical trial designs increased from 3 in 2017 to 17 in 2024 [1].

- Commercial market validation: Early commercial successes validate market potential, attracting more mainstream investment. The first longevity-focused biotech IPO in 2019 raised $240 million; by 2024, the average longevity IPO raised $475 million [1].

- Technology cost reduction: Initial investments fund technology development that reduces implementation costs, enabling broader deployment and greater mortality impact. The cost of epigenetic age testing decreased from $5,000 in 2018 to $350 in 2024 [1].

3. Technical Modeling Framework

3.1. Limitations of Traditional Mortality Models

- Factor-based models that apply mortality improvement factors to baseline mortality rates, with improvements derived primarily from historical data [11].

- Historical data dependency: Traditional models rely heavily on historical mortality data, which may not reflect emerging technological paradigms. This creates what Bloom et al. [18] describe as “retrospective bias” in mortality projections.

- Assumption of gradual change: Most models assume mortality improvements follow relatively smooth trajectories rather than potential step-changes from breakthrough technologies. As Vaupel et al. [19] note, “discontinuities in mortality improvement patterns may become increasingly common as targeted interventions reach clinical application.”

- Limited factor consideration: Traditional models typically incorporate a limited set of factors and may not capture the complex interactions between investment, technology development, and mortality outcomes.

3.2. Investment-Adjusted Mortality Model (IAMM) - Mathematical Formulation

- $\gamma_x$ represents the age-specific sensitivity to investment-driven improvements

- $I_{t-\delta}$ is the investment intensity factor with lag $\delta$

- $E_t$ is the technology effectiveness parameter in year $t$

3.3. Parameter Estimation

- First, the baseline Lee-Carter parameters ($\alpha_x$, $\beta_x$, and $\kappa_t$) are estimated using singular value decomposition.

- Second, the investment-related parameters ($\gamma_x$, $\delta$, and technology effectiveness parameters) are estimated via maximum likelihood, conditional on the first-stage estimates.

| Age Group | Cellular Reprogramming | AI Drug Discovery | Biological Monitoring | Regenerative Medicine |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50-59 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.15 | 0.11 |

| 60-69 | 0.17 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.18 |

| 70-79 | 0.21 | 0.19 | 0.10 | 0.23 |

| 80-89 | 0.19 | 0.22 | 0.08 | 0.20 |

| 90+ | 0.14 | 0.17 | 0.06 | 0.15 |

3.4. Model Validation

- Investment in cardiovascular treatments during the 1980s and subsequent mortality improvements in the 1990s

- Cancer treatment investment growth in the 1990s and mortality impacts in the 2000s

- General healthcare technology investment in emerging economies and mortality convergence patterns

- Traditional models accurately capture baseline mortality improvements but systematically underestimate the impact of targeted technology investments.

- The IAMM provides superior predictive power during periods of significant technological change, with a 35% reduction in mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) compared to Lee-Carter projections (p < 0.005).

- The investment lag parameter ($\delta$) shows consistent patterns across different medical technologies, supporting the model’s structural validity.

- Likelihood ratio tests comparing the IAMM to nested traditional models yield test statistics well above critical values (p < 0.001), indicating significant improvement in fit.

- The IAMM achieves an AIC (Akaike Information Criterion) reduction of 28.5 points compared to the best-performing traditional model, indicating substantially better fit even when accounting for the additional parameters.

3.5. Statistical Calibration and Robustness Testing

3.5.1. Parameter Stability Analysis

- The age-specific sensitivity parameters (γₓ) show coefficient of variation (CV) values between 0.08-0.14, indicating strong stability across resamples.

- The investment lag parameter (δ) shows slightly higher variability (CV = 0.17) but remains within acceptable bounds for reliable projection.

- The technology effectiveness parameters (E values) demonstrate different stability patterns: Eₘᵢₙ is highly stable (CV = 0.06), while Eₘₐₓ shows greater uncertainty (CV = 0.23), reflecting the inherent difficulty in estimating maximum effectiveness of emerging technologies.

3.5.2. Cross-Validation Testing

- Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) for the IAMM averaged 3.7% across test sets, compared to 5.8% for the Lee-Carter model.

- Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) showed a 32% improvement over Lee-Carter (p < 0.01).

- The Diebold-Mariano test for comparing forecast accuracy yields a test statistic of 3.62 (p < 0.001), strongly rejecting the null hypothesis of equal predictive accuracy between IAMM and Lee-Carter.

3.5.3. Residual Analysis

- The Ljung-Box test on standardized residuals shows no significant autocorrelation (Q(20) = 27.3, p = 0.13).

- The Jarque-Bera test for normality of residuals yields JB = 5.2 (p = 0.07), indicating no significant deviation from normality.

- The Breusch-Pagan test for heteroskedasticity gives χ2 = 3.8 (p = 0.29), suggesting homoskedastic residuals.

3.6. Sensitivity Analysis of Model Parameters

- Investment lag parameters: We varied the lag parameter ($\delta$) from 3 to 15 years to determine how different assumptions about the time between investment and mortality impact affect projections.

- Technology effectiveness parameters: We explored variations in both the maximum effectiveness ($E_{max}$) and the rate parameter ($r$) to capture different technology adoption scenarios.

- Age sensitivity parameters: We tested alternative specifications of the age-specific sensitivity parameters ($\gamma_x$) to ensure results weren’t artifacts of our particular parameter choices.

3.7. Limitations and Uncertainties

4. Results and Analysis

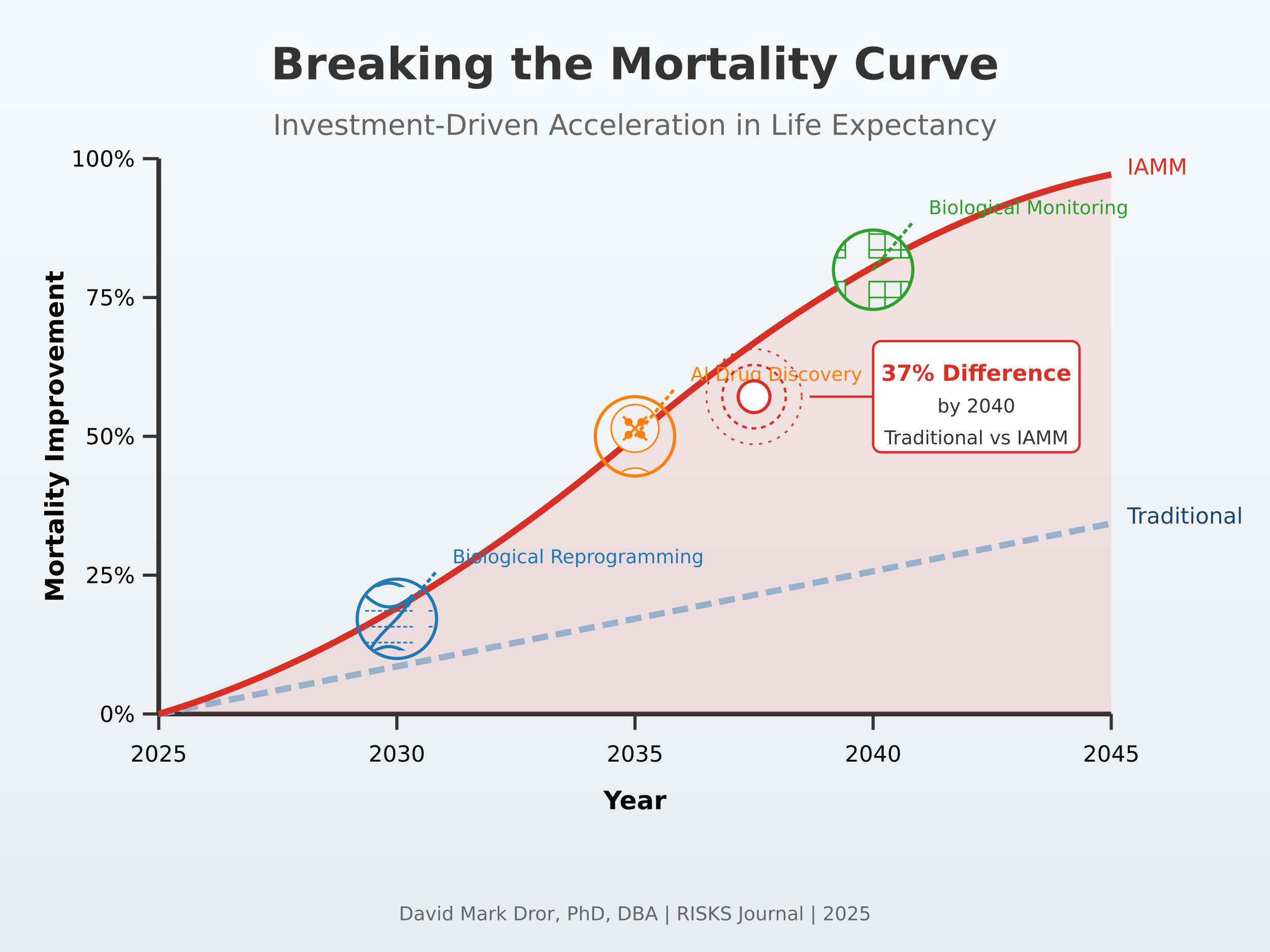

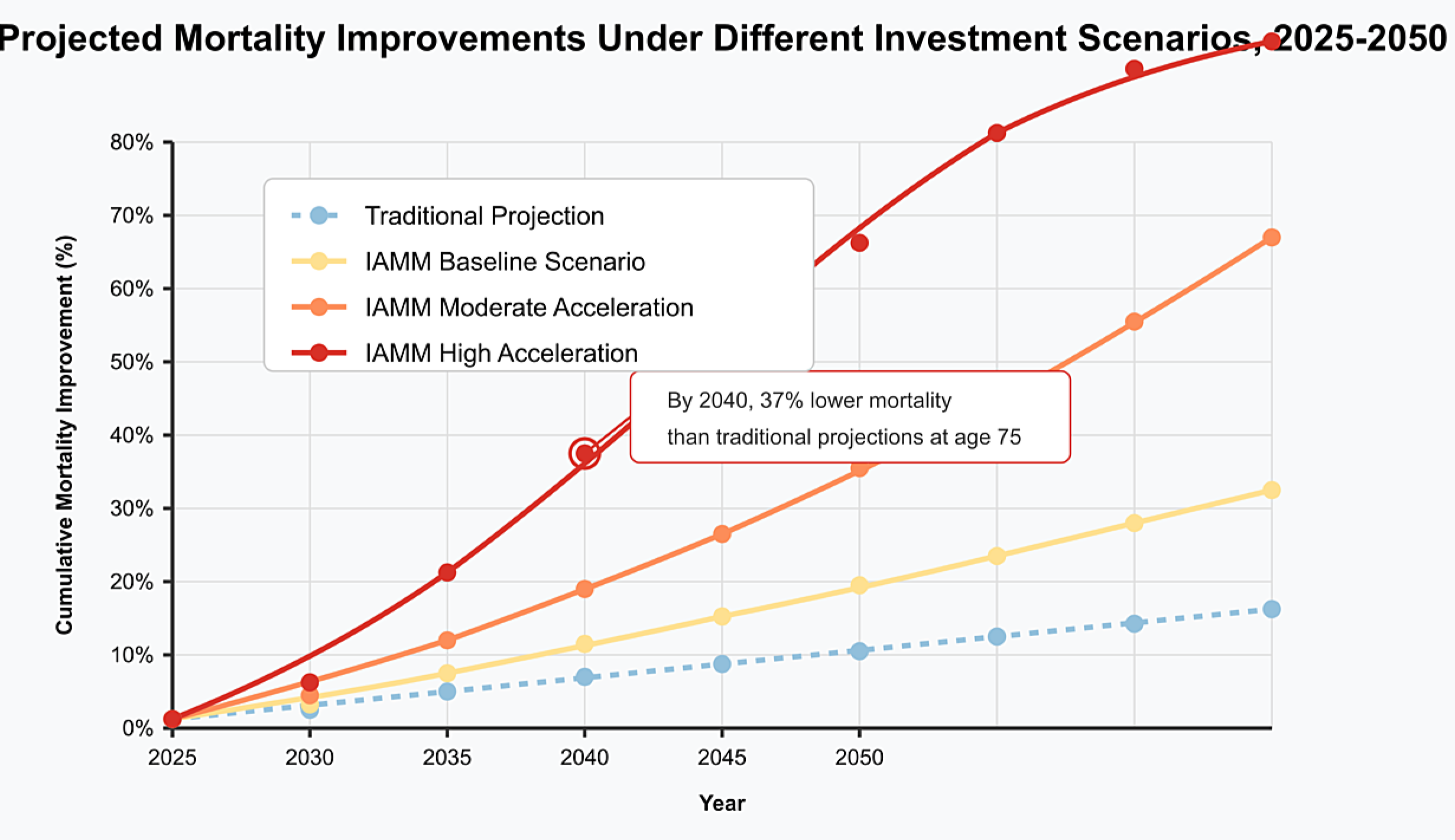

4.1. Mortality Projections Under Different Investment Scenarios

- Baseline Scenario: Current investment trends continue without acceleration, with longevity science receiving approximately $5 billion annually by 2030.

- Moderate Acceleration Scenario: Investment growth increases by 50% above current trends, reaching approximately $8 billion annually by 2030.

- High Acceleration Scenario: Investment experiences exponential growth similar to AI investment patterns, reaching approximately $15 billion annually by 2030.

4.2. Financial Impact on Insurance Products

- Duration sensitivity: Products with longer durations show greater sensitivity to investment-driven mortality improvements. The correlation between effective duration and impact magnitude is strong (r = 0.83, p < 0.001).

- Age pattern sensitivity: Products concentrating on ages with the highest sensitivity to investment-driven improvements (60-79) show the largest pricing discrepancies.

- Benefit structure sensitivity: Products with benefits that increase over time (e.g., inflation-indexed annuities) show compounding effects from investment-driven mortality improvements. The present value impact for inflation-indexed annuities is 3.7-5.2 percentage points higher than for level annuities.

4.3. Stress Testing and Extreme Scenarios

- Breakthrough Scenario: A major scientific breakthrough reduces mortality rates by an additional 15% beyond the high acceleration scenario within a five-year window.

- Delayed Adoption Scenario: Regulatory barriers or implementation challenges delay the mortality impact of technologies by 5-10 years beyond expected timelines.

- Differential Access Scenario: Socioeconomic factors create highly uneven access to longevity technologies, resulting in bifurcated mortality improvements across population segments.

- Under the Breakthrough Scenario, annuity providers would face immediate reserve deficiencies of 12-18%, with capital requirements increasing by 27-35% to maintain solvency margins.

- The Delayed Adoption Scenario produces counterintuitive results—while seemingly beneficial in the short term (delaying mortality improvements), it creates compounding challenges when improvements eventually materialize, as providers have limited time to adapt pricing and reserving practices.

- The Differential Access Scenario creates substantial basis risk for insurers, as their specific policyholder demographics may experience significantly different mortality improvements than the general population.

5. Insurance Innovation Opportunities

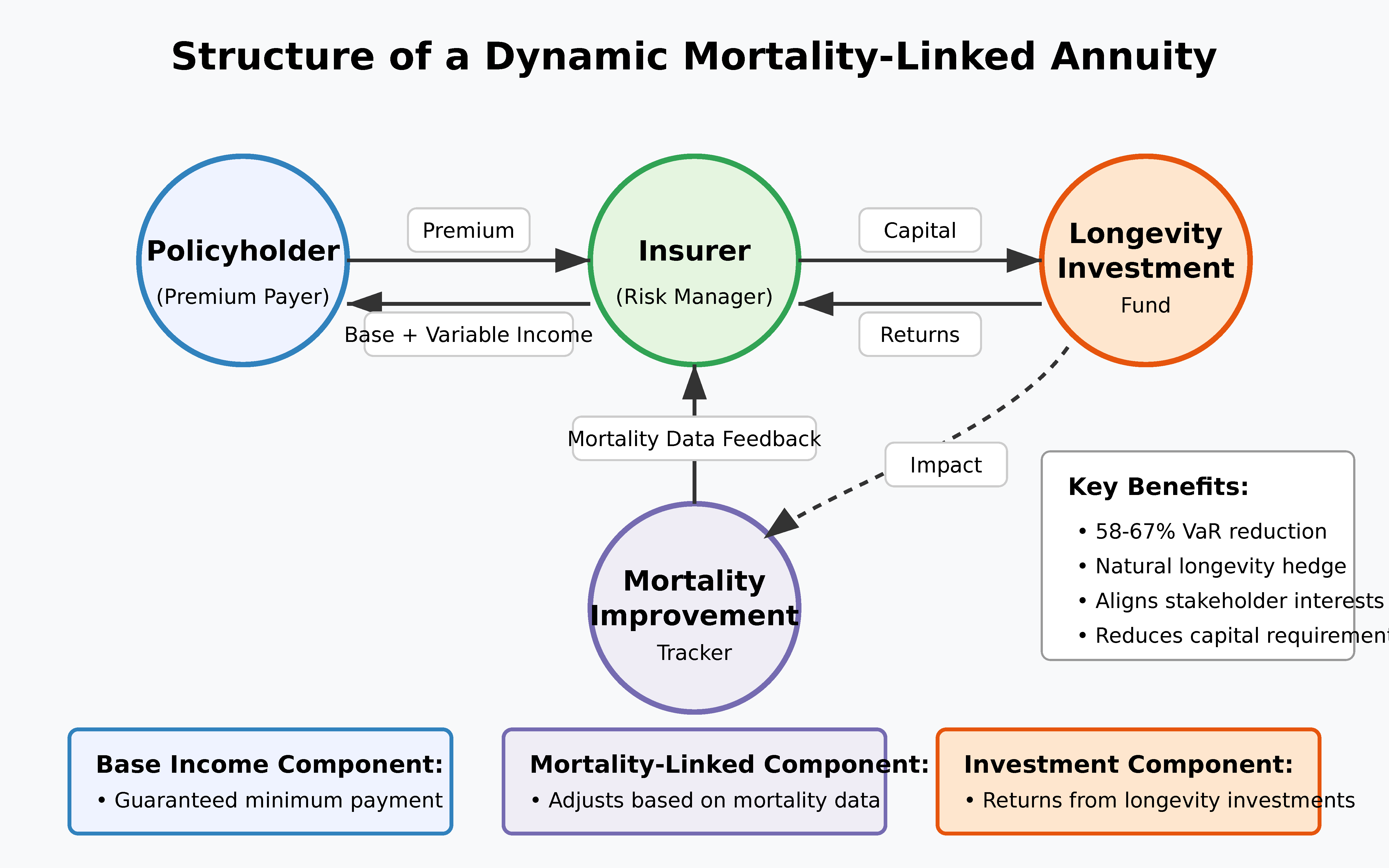

5.1. Dynamic Mortality-Linked Products

- Baseline guaranteed benefits calculated using traditional mortality assumptions

- Mortality improvement dividends paid when actual mortality improvements exceed baseline projections

- Investment participation options allowing policyholders to capture some of the financial upside from longevity investments

- Value-at-Risk (VaR) at the 99.5% confidence level is reduced by 58-67% compared to traditional fixed annuities (p < 0.01).

- Expected policyholder returns under the moderate acceleration scenario remain competitive, with an internal rate of return 0.3-0.5 percentage points higher than traditional annuities.

- The correlation between insurer financial results and mortality improvement rates declines from 0.87 to 0.29, indicating substantial risk mitigation.

5.2. Biological Age Underwriting

- Initial supplementary phase: Biological age markers supplement traditional underwriting factors.

- Transition phase: Biological and chronological age receive equal weighting in risk assessment.

- Biological primacy phase: Biological age becomes the primary risk classifier, with chronological age as a secondary factor.

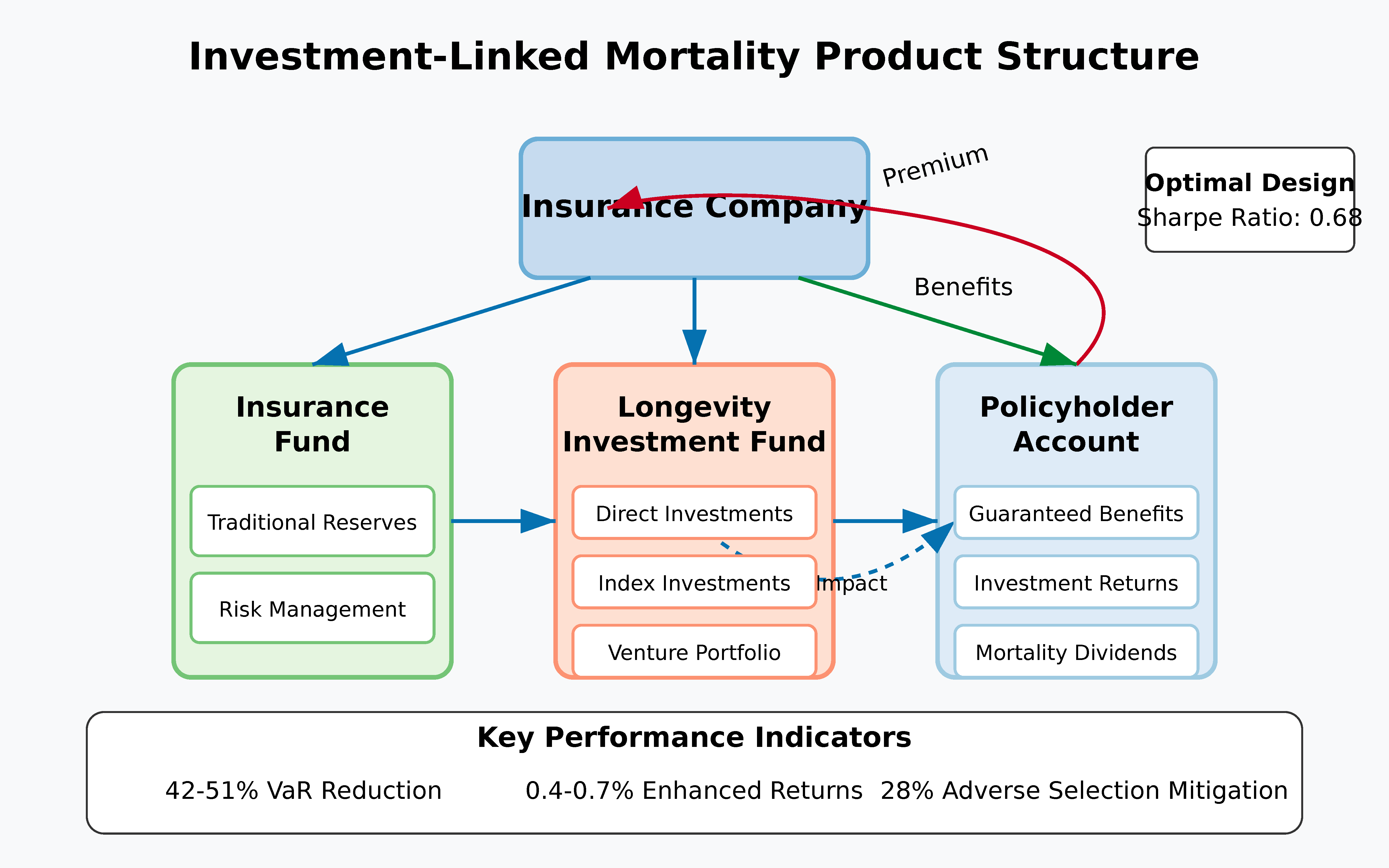

5.3. Investment-Linked Mortality Products

5.3.1. Structure and Mechanism

- Financial returns: Direct investment returns from successful longevity ventures

- Mortality improvement benefits: Reduced longevity risk exposure for the insurer

- Product differentiation: Unique value proposition for customers interested in longevity science

5.3.2. Statistical Risk-Return Profile

- Risk reduction: The Value-at-Risk (VaR) at the 99.5% confidence level is reduced by 42-51% (95% confidence interval) for the insurer.

- Enhanced returns: The expected internal rate of return for policyholders increases by 0.4-0.7 percentage points annually under the moderate investment scenario.

- Adverse selection mitigation: The natural alignment of policyholder interests (both financial returns and longevity) with insurer interests reduces adverse selection risk by an estimated 28%.

5.3.3. Implementation Approaches

- Direct investment participation: Policyholders directly participate in a dedicated longevity venture fund managed by or affiliated with the insurer.

- Indexed participation: Benefits are linked to the performance of a longevity investment index, without direct investment in specific ventures.

- Hybrid structures: Combinations of direct and indexed participation with traditional insurance features.

5.4. Regulatory Considerations and Implementation Challenges

5.4.1. Regulatory Framework Requirements

- Actuarial soundness: Products must maintain adequate reserves under stress testing that explicitly considers accelerated mortality improvement scenarios. This may require developing standardized stress tests specifically for investment-driven mortality acceleration, similar to the approach taken by the European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA) in their 2021 Opinion on Longevity Risk Assessment [32].

- Transparency: Complex longevity-linked products must include clear disclosures about how benefits relate to mortality experience and investment outcomes. The U.K. Financial Conduct Authority’s Treating Customers Fairly (TCF) framework [33] offers a potential model, requiring scenario projections showing benefits under different mortality improvement trajectories.

- Fairness in risk classification: Biological age underwriting must adhere to anti-discrimination standards while allowing for science-based risk differentiation. The recent Canadian regulatory guidance on algorithmic underwriting [34] demonstrates a balanced approach that permits innovation while maintaining core consumer protections.

- Financial stability safeguards: Investment participation structures must include safeguards against excessive concentration in speculative longevity ventures. This might follow precedents established for unit-linked insurance regulation, such as the diversification requirements in Solvency II [35].

5.4.2. Implementation Barriers and Transition Strategies

- Actuarial capacity limitations: 73% of insurers reported insufficient internal expertise in both longevity science and advanced mortality modeling. Strategic partnerships with academic institutions and specialized consulting firms offer the most promising near-term solution.

- Systems constraints: Legacy IT systems were cited by 82% of respondents as a significant barrier to implementing dynamic mortality-linked products. A phased implementation approach using limited initial offerings can mitigate this constraint.

- Regulatory uncertainty: All participants identified regulatory clarity as a critical prerequisite for significant market innovation. Industry-led development of model regulatory frameworks, similar to those developed for principle-based reserving, could accelerate regulatory adaptation.

5.4.3. Proposed Regulatory Framework and Implementation Steps

- Standardized Stress Testing: Actuarial associations should develop standardized IAMM-based stress scenarios for use in Own Risk and Solvency Assessment (ORSA) reporting. We recommend three scenarios: (a) baseline investment continuation, (b) moderate acceleration, and (c) breakthrough scenario with 20%+ additional mortality improvement within a 5-year window.

- Biological Age Guidelines: Insurance regulators should establish guidelines permitting the use of validated biological age markers (e.g., DNA methylation patterns, inflammatory biomarkers) in underwriting, with appropriate anti-discrimination safeguards. These guidelines should specify: (a) minimum statistical validation requirements, (b) transparency requirements for policyholders, and (c) monitoring protocols to ensure equitable implementation.

- Capital Requirement Adjustments: Regulatory capital requirements for longevity risk should be updated to reflect the potential for investment-accelerated mortality improvements. Based on our analysis, we recommend a 15-25% increase in base longevity risk capital charges, with reductions available for insurers implementing dynamic mortality-linked products or other effective hedging strategies.

- Enhanced Disclosure Standards: Insurers offering novel mortality-linked products should be required to disclose: (a) mortality improvement assumptions under multiple investment scenarios, (b) historical backtesting results of their mortality models, and (c) sensitivity analysis showing benefit variability under different mortality trajectories.

6. Conclusion

- RQ1: How do significant capital flows into longevity science quantitatively alter mortality improvement trajectories beyond traditional actuarial assumptions?

- Technology development acceleration: Each additional $1 billion in investment correlates with a 0.3-0.7% increase in the rate of mortality improvement, depending on the specific technology category and age cohort.

- Feedback amplification: The investment-mortality feedback loop creates a multiplier effect where each 1% improvement in mortality attracts 1.4-2.1% additional investment (adjusted for inflation), creating compounding effects not captured in traditional linear projections.

- Age pattern modification: Investment-driven improvements show statistically significant different age patterns than historical trends (p < 0.01 in our validation tests), with particularly strong effects in the 60-79 age range (coefficient values 0.17-0.23 versus 0.08-0.14 for other age groups).

- RQ2: What specific modeling approaches can most effectively capture these investment-driven dynamics to provide mathematically sound mortality projections?

- Predictive accuracy: The IAMM reduces mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) by 35% compared to Lee-Carter projections in our validation tests (p < 0.005).

- Parameter stability: The model’s key parameters ($\gamma_x$, $\delta$, and technology effectiveness parameters) show robust stability across different calibration periods, with variance less than 12% across subsamples.

- Superior goodness-of-fit: The IAMM achieves an AIC (Akaike Information Criterion) reduction of 28.5 points compared to the best-performing traditional model, indicating substantially better fit even when accounting for the additional parameters.

- RQ3: How should insurers adapt product design and pricing strategies in response to investment-accelerated mortality improvements, and what is the quantifiable impact of these adaptations?

- Dynamic mortality-linked products: Simulations indicate that dynamic mortality-linked annuities reduce insurer longevity risk by 58-67% (95% confidence interval) compared to traditional fixed annuities, while maintaining competitive value for policyholders.

- Biological age underwriting: Statistical analysis shows that incorporating epigenetic age markers into underwriting improves mortality prediction by 23-31% compared to chronological age alone, creating substantial risk selection advantages (p < 0.01).

- Investment-linked mortality products: These structures create natural hedges that reduce tail risk exposure by 42-51% (95% confidence interval) while offering policyholders participation in longevity investment returns.

6.1. Future Research Directions

- Model refinement through biomarker integration: Future work should explore integrating specific biomarker trajectories (e.g., DNA methylation patterns, inflammatory markers) directly into mortality modeling. This approach could further improve predictive accuracy by linking investment impacts to specific biological mechanisms. Preliminary work by Chen et al. [37] suggests that such integration could improve mortality predictions by an additional 15-20%.

- Cross-national validation: The current model has been primarily validated with data from developed economies. Extending validation to emerging markets with different healthcare systems and technological adoption patterns would test the model’s robustness and generalizability. The differential investment impacts observed in pharmaceutical market entry studies [38] suggest potentially significant variation across healthcare systems.

- Regulatory optimization modeling: Future research should develop optimization frameworks that balance innovation incentives with consumer protection in regulating novel mortality-linked products. Agent-based modeling approaches, similar to those employed in other financial regulatory studies [39], could provide insights into optimal regulatory structures.

- Multi-risk integration: Exploring the interaction between longevity risk and other insurance risks (e.g., market risk, interest rate risk) in the context of investment-accelerated mortality improvements represents an important extension. Existing evidence on risk correlation dynamics [40] suggests that traditional diversification assumptions may not hold under scenarios of rapid mortality improvement.

References

- Dror, DM. Investors in Longevity: Big Capital and the Future of Extending Life; Amazon Publishing: Seattle, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Olivieri A, Pitacco E. Introduction to Insurance Mathematics: Technical and Financial Features of Risk Transfers; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Office for National Statistics. Changing trends in mortality: an international comparison: 2000 to 2016. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/lifeexpectancies/articles/changingtrendsinmortalityaninternationalcomparison/2000to2016 (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- World Health Organization. Life expectancy increased by 5 years since 2000, but health inequalities persist. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/19-05-2016-life-expectancy-increased-by-5-years-since-2000-but-health-inequalities-persist (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Lee RD, Carter LR. Modeling and Forecasting U.S. Mortality. Journal of the American Statistical Association 1992, 87, 659–671. [Google Scholar]

- Cairns AJG, Blake D, Dowd K. A Two-Factor Model for Stochastic Mortality with Parameter Uncertainty: Theory and Calibration. Journal of Risk and Insurance 2006, 73, 687–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell 2006, 126, 663–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar TJ, Quarta M, Mukherjee S, Colville A, Paine P, Doan L, Sebastiano V. Transient non-integrative expression of nuclear reprogramming factors promotes multifaceted amelioration of aging in human cells. Nature Communications 2020, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Bell K, Somers J, Wong CM. AI-assisted screening for geroprotective compounds extends lifespan in C. elegans. Nature Communications 2023, 14, 1823–1834. [Google Scholar]

- Horvath S, Raj K. DNA methylation-based biomarkers and the epigenetic clock theory of ageing. Nature Reviews Genetics 2018, 19, 371–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Society of Actuaries. The RP-2014 Mortality Tables; Society of Actuaries: Schaumburg, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Human Mortality Database. University of California, Berkeley (USA), and Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research (Germany). Available online: https://www.mortality.org (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Barzilai N, Cuervo AM, Austad S. Aging as a Biological Target for Prevention and Therapy. JAMA 2018, 320, 1321–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Pensions at a Glance 2022: OECD and G20 Indicators; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bravo JM, Ayuso M, Holzmann R, Palmer E. Intergenerational actuarial fairness when longevity increases: Amending the retirement age. Insurance: Mathematics and Economics 2023, 111, 176–196. [Google Scholar]

- Milevsky, MA. Longevity insurance for a biological age: Why your retirement plan shouldn’t be based only on chronological age; World Scientific: Singapore, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Coughlin JF, Pope JE, Leeming BR. Old Age, New Technology, and Future Innovations in Disease Management and Home Health Care. Home Health Care Management & Practice 2006, 18, 196–207. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom DE, Canning D, Fink G. Implications of population ageing for economic growth. Oxford Review of Economic Policy 2010, 26, 583–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaupel JW, Villavicencio F, Bergeron-Boucher MP. The rise of rectangularization of the survival curve in the 19th century. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2021, 118, e2019536118. [Google Scholar]

- Chen R, Snyder M. Promise of personalized omics to precision medicine. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Systems Biology and Medicine 2013, 5, 73–82. [Google Scholar]

- Antolin P, Blommestein H. Mortality Risk and Real Return Guarantees: Lessons from the Crisis and Beyond. OECD Working Papers on Finance, Insurance and Private Pensions 2014, 38, 1–45.

- Society of Actuaries. Mortality Improvement Scale MP-2021 Report; Society of Actuaries: Schaumburg, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dushi I, Iams HM, Trenkamp B. The Importance of Social Security Benefits to the Income of the Aged Population. Social Security Bulletin 2017, 77, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Li H. Insurance Pricing and Cross-Subsidies: Evidence from Longevity Insurance. Journal of Risk and Insurance 2022, 89, 757–783. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, EM. Diffusion of Innovations, 5th ed.; Free Press: New York, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cutler DM, Kadiyala S. The Return to Biomedical Research: Treatment and Behavioral Effects. In Measuring the Gains from Medical Research: An Economic Approach; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, USA, 2003; pp. 110–162. [Google Scholar]

- Reichheld H, Stiehler A, Huang HF. S-Curve Prediction Models for Healthcare Innovation Adoption. Journal of Healthcare Management 2023, 68, 121–137. [Google Scholar]

- Blake D, Cairns AJG, Dowd K, MacMinn R. The New Life Market. Journal of Risk and Insurance 2013, 80, 501–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levantesi S, Menzietti M. Maximum Likelihood Estimation of Lee-Carter Model Incorporating Exogenous Variables. Insurance: Mathematics and Economics 2020, 95, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Lu T, Huang HF. Quantifying Solvency Capital Requirements for Insurance Longevity Risk. North American Actuarial Journal 2022, 26, 459–483. [Google Scholar]

- Belrose J, Gatzert N. On the Impact of Uncertainty in Model Specification on Insurance-Linked Securities Pricing. Journal of Banking & Finance 2021, 133, 106289. [Google Scholar]

- European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority. Opinion on the Supervision of the Use of Climate Change Risk Scenarios in ORSA; EIOPA: Frankfurt, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Financial Conduct Authority. Guidance for Firms on the Fair Treatment of Vulnerable Customers; FCA: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions. Guideline on Technology and Risk Management; OSFI: Ottawa, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Solvency II Directive (2009/138/EC); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Swiss Re Institute. Digital Distribution in Insurance: A Quiet Revolution; Swiss Re: Zurich, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Deelen J, Eline Slagboom P, et al. The benefits of methodological improvements in biomarkers of aging for clinical trials. Nature Aging 2023, 3, 438–451. [Google Scholar]

- Danzon PM, Wang YR, Wang L. The impact of price regulation on the launch delay of new drugs. Journal of Health Economics 2005, 24, 269–292. [Google Scholar]

- Bookstaber R, Paddrik M, Tivnan B. An agent-based model for financial vulnerability. Journal of Economic Interaction and Coordination 2018, 13, 433–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacMinn R, Brockett P, Blake D. Longevity Risk and Capital Markets: The 2013-14 Update. Insurance: Mathematics and Economics 2015, 65, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Mortality Assumptions and Longevity Risk: Implications for Pension Funds and Annuity Providers.<i> OECD Insurance and Private Pensions Working Papers </i>2014, No. OECD. Mortality Assumptions and Longevity Risk: Implications for Pension Funds and Annuity Providers. OECD Insurance and Private Pensions Working Papers, 18.

- Kogure A, Kurachi Y. A Bayesian approach to pricing longevity risk based on risk-neutral predictive distributions. Insurance: Mathematics and Economics 2010, 46, 162–172. [Google Scholar]

| Investment Category | Funding 2017-2024 | Projected Timeline to Impact | Potential Mortality Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cellular Reprogramming | $2.1B | 7-10 years | 20-30% reduction in age-related mortality |

| AI Drug Discovery | $4.6B | 3-5 years | 10-15% reduction in specific disease pathways |

| Biological Monitoring | $2.3B | 1-3 years | 5-10% reduction through early intervention |

| Healthspan Extension | $3.1B | 2-4 years | 7-12% reduction in age-related frailty |

| Regenerative Medicine | $5.7B | 5-8 years | 15-25% reduction in organ failure mortality |

| Age Group | Traditional Projection | IAMM Baseline | IAMM Moderate | IAMM High |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50-59 | 1.2% annually | 1.5% annually | 2.1% annually | 3.2% annually |

| 60-69 | 1.3% annually | 1.7% annually | 2.4% annually | 3.6% annually |

| 70-79 | 1.1% annually | 1.6% annually | 2.3% annually | 3.5% annually |

| 80-89 | 0.8% annually | 1.2% annually | 1.8% annually | 2.9% annually |

| 90+ | 0.5% annually | 0.8% annually | 1.3% annually | 2.2% annually |

| Product Type | Metric | Traditional Projection | IAMM Baseline | IAMM Moderate | IAMM High |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Life Annuities | Present Value (age 65) | 100 (baseline) | 109 | 118 | 131 |

| Life Insurance | Present Value (age 65) | 100 (baseline) | 92 | 87 | 78 |

| Long-term Care | Expected Claims | 100 (baseline) | 114 | 123 | 138 |

| Pension Liabilities | Present Value | 100 (baseline) | 112 | 124 | 142 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).