4.1. Empirical Analysis of Capital Investment in Japan

The first empirical example analyzes business expenditures for new plant and equipment (BE) in Japan. The goal of this example is to demonstrate the analytical procedure and highlight the effectiveness of the reinforcement in the ML model approach.

The time series of BE reflects levels of capital investment and is known for exhibiting distinct structural characteristics. The original BE data were obtained from the website of the Japanese Cabinet Office (see [

11]). The data constitute a monthly time series spanning from January 1975 to December 2024, amounting to

observations.

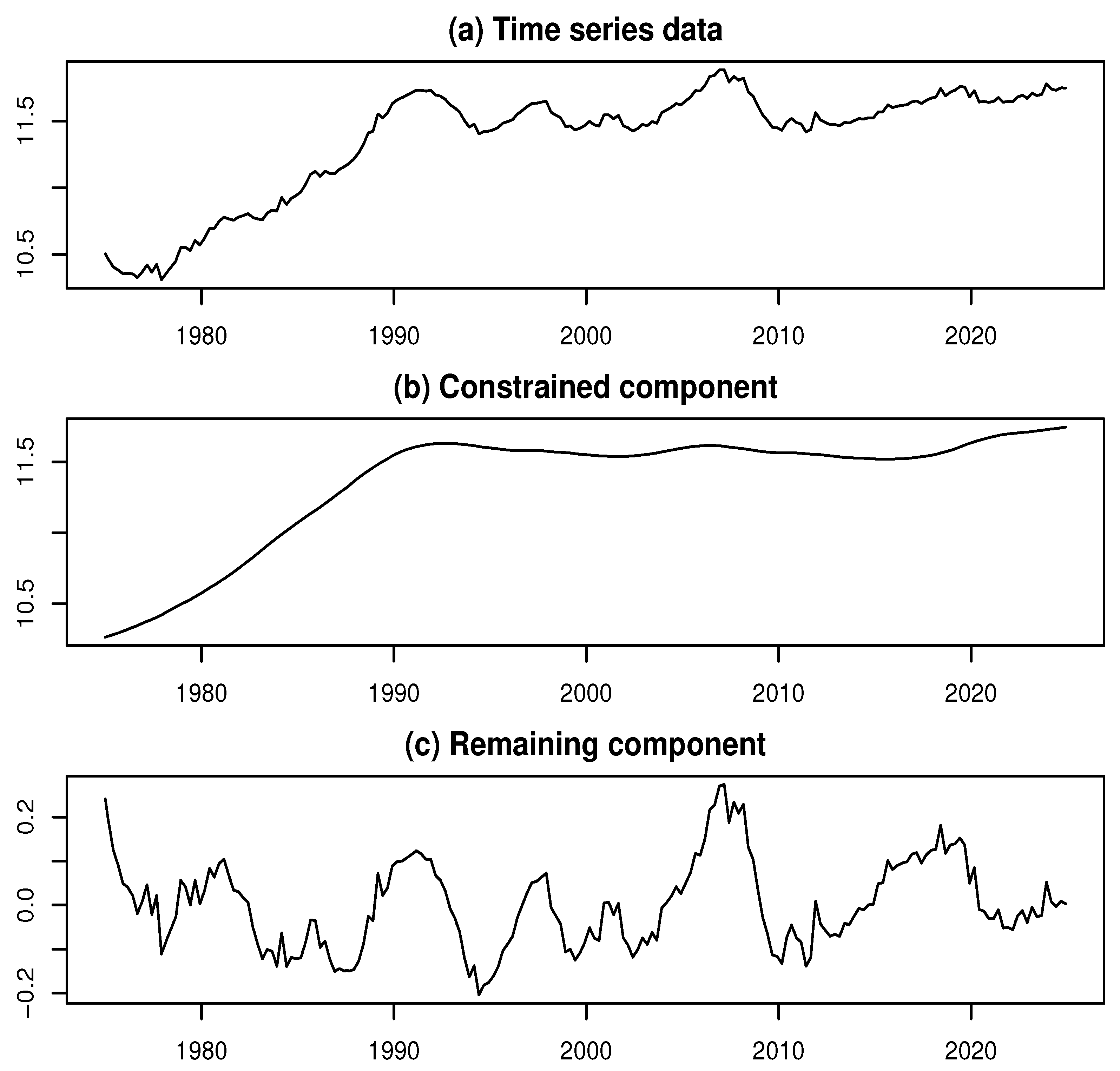

Figure 2a displays a plot of the logarithmically transformed BE series (log-BE).

We applied the ML model approach to decompose the log-BE time series, performing the decomposition for each value of

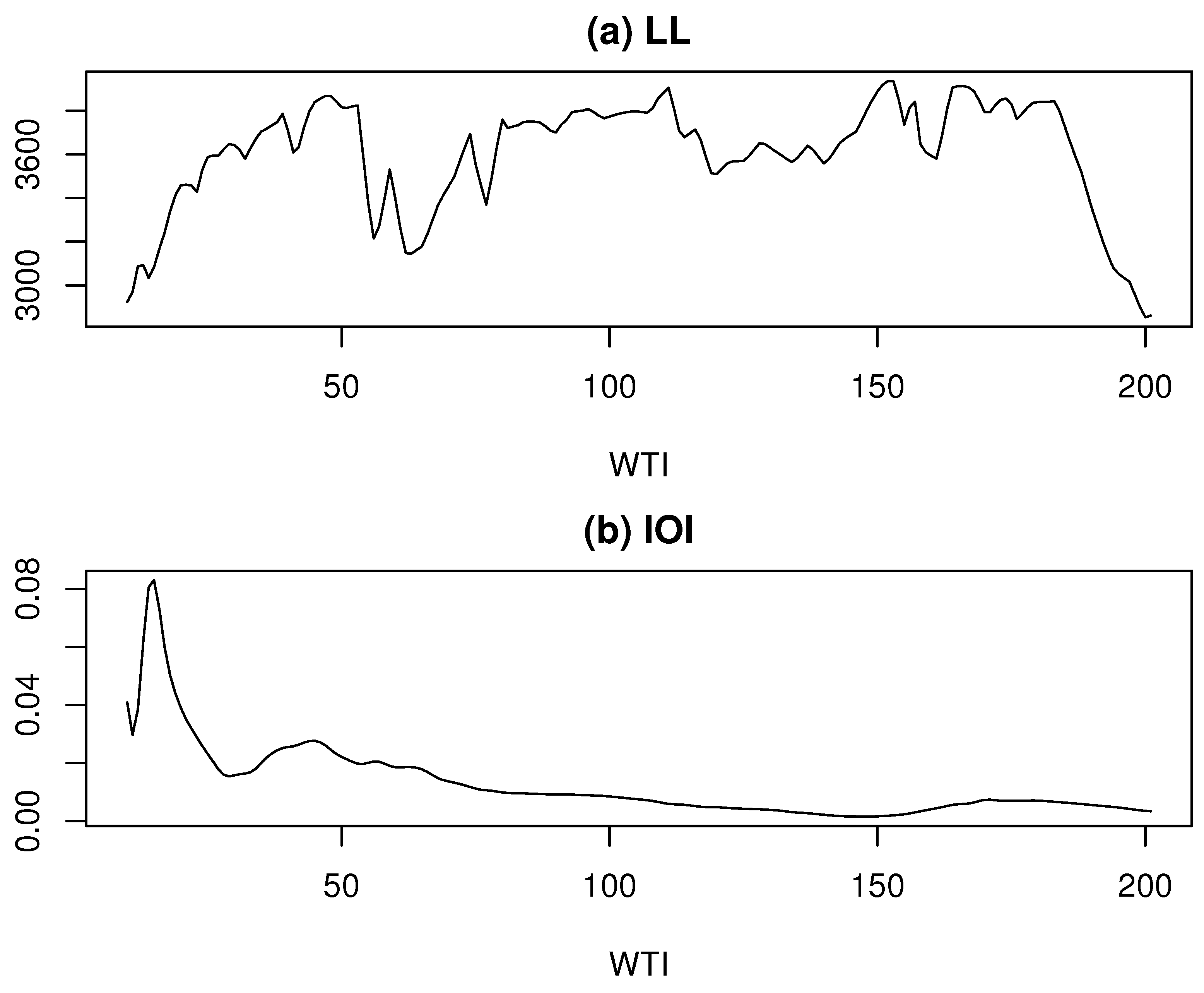

k ranging from 3 to 202. As shown in

Figure 1a, the log-likelihood (LL) exhibits local maxima at three values of

k: 47, 111, and 152, corresponding to LL values of 3867.97, 3905.51, and 3936.1, respectively. Among these, the highest LL is achieved at

, which is adopted as the estimate of

k. Furthermore,

Figure 1b indicates that the IOI reaches its minimum around

. These findings suggest that the maximum likelihood estimate of

k effectively captures a stable underlying structure.

Figure 2b,c illustrate the decomposed results for the log-BE time series, with

Figure 2b depicting the constrained component and

Figure 2c representing the remaining component.

Figure 2.

Data and decomposed results for the log-BE time series

Figure 2.

Data and decomposed results for the log-BE time series

Incidentally, to validate the results of this study, we refer to the state-space modeling approach introduced in [

8]. In that work, the R function

season is employed to decompose a time series into three components: a trend component, an AR component, and observation noise. When this function was applied to the log-BE series, the order of the trend component was estimated to be 2, and that of the AR component was estimated to be 4. Based on these estimates, the time series was decomposed accordingly.

To align with the ML model framework, we treated the trend component as the constrained component and considered the combined AR component and observation noise as the remaining component. For each value of k, we computed the MISS values by comparing the decomposition results from the ML model approach with those obtained using the season function. The MISS reached its minimum around , suggesting that the conventional state-space-based decomposition closely corresponds to the ML model approach at this value of k. Notably, around , the IOI value is approximately 0.08, which is near its maximum. This implies that the conventional component decomposition using the state-space model lacks stability.

These findings suggest that the constrained component produces a highly smooth time series, effectively capturing the long-term trend in log-BE. Consequently, most short-term fluctuations are absorbed into the remaining component, which exhibits complex and irregular behavior. This observation provides a strong rationale for reapplying the ML model approach to further decompose the (first) remaining component.

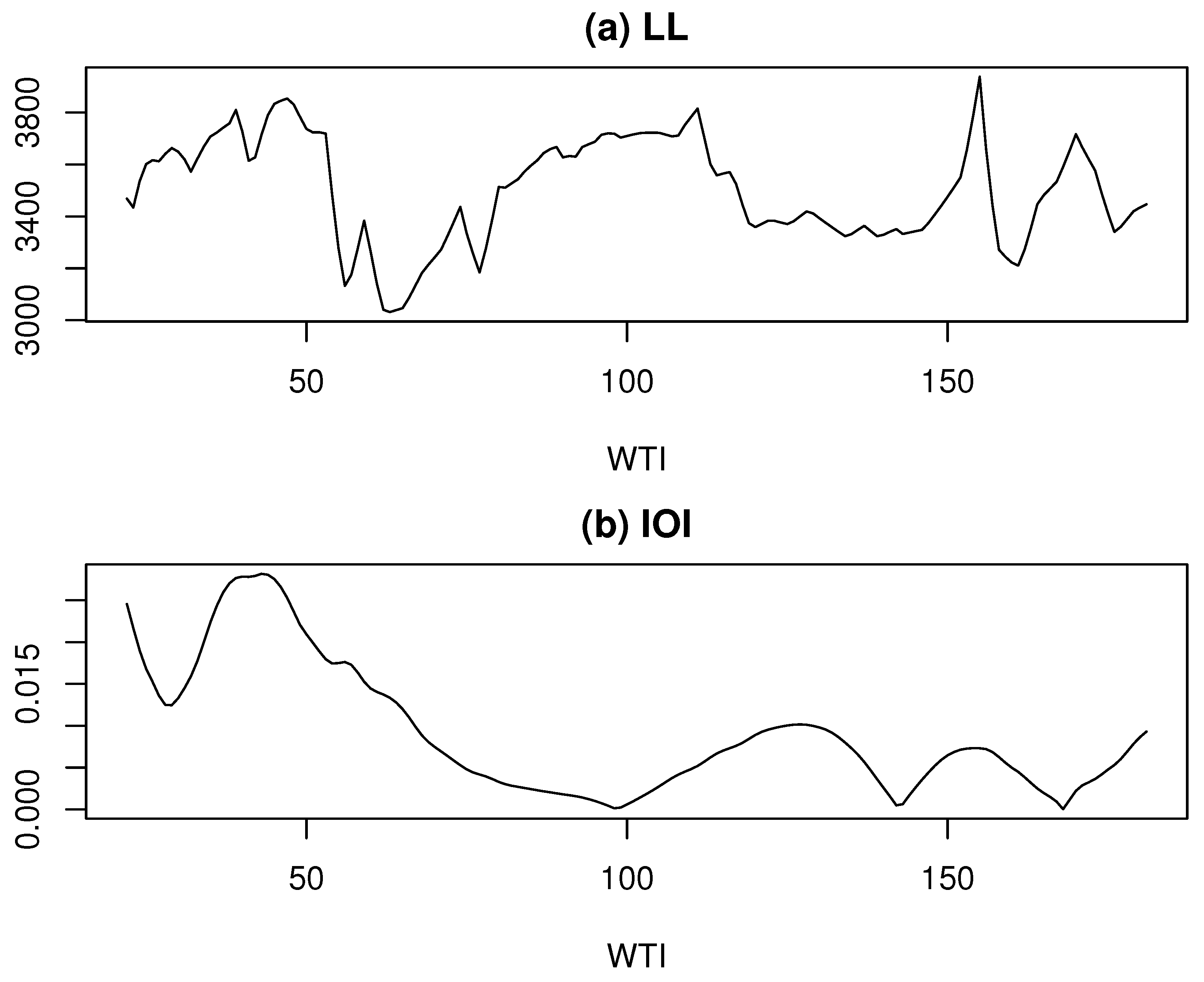

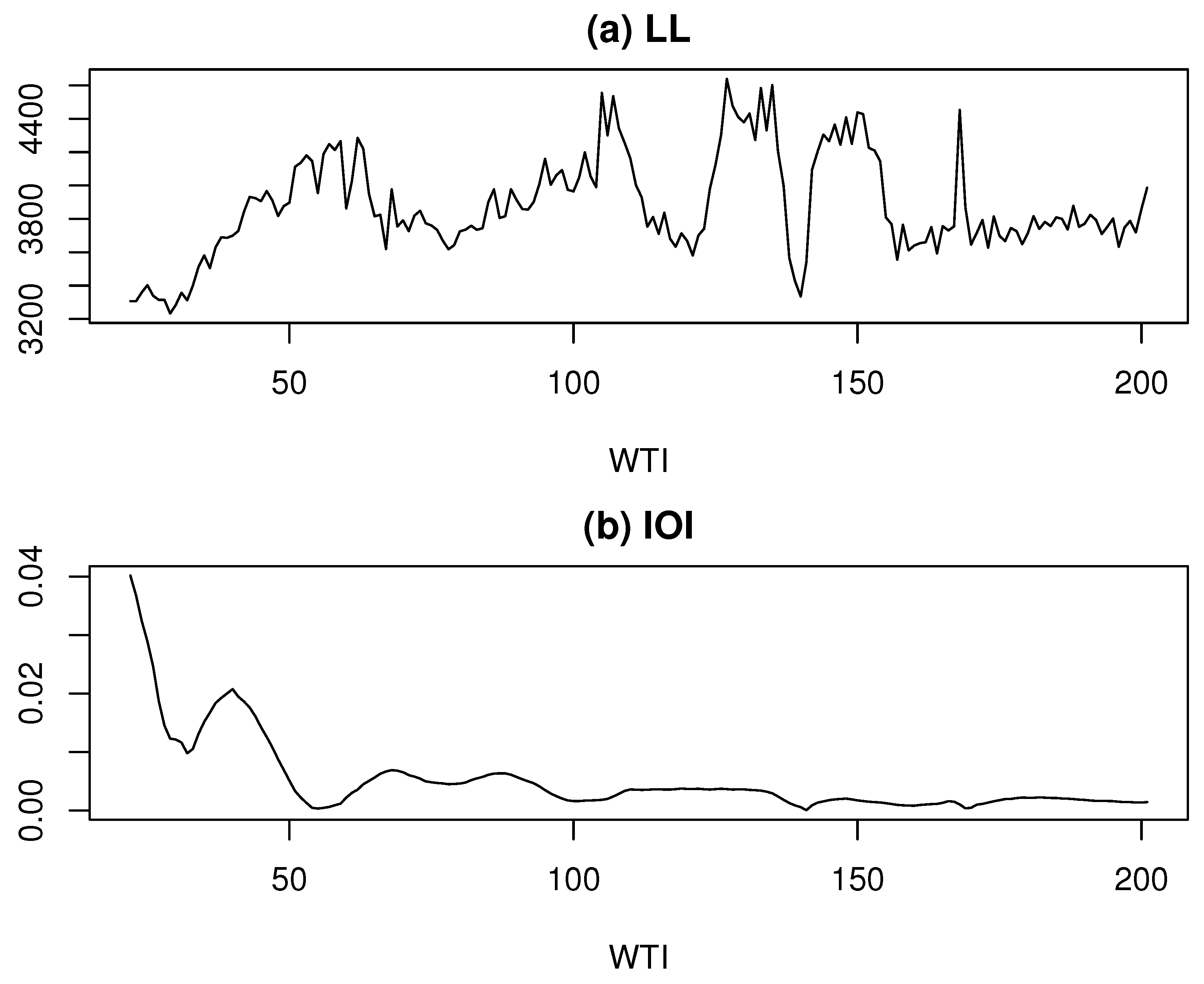

Thus, we further decomposed the log-BE time series for each value of

k ranging from 3 to 182. As shown in

Figure 3a, similar to the first component decomposition, the LL exhibits local maxima at three values of

k: 47, 111, and 155, corresponding to LL values of 3853.70, 3814.70, and 3937.52, respectively. Among these, the highest LL is achieved at

.

However, as shown in

Figure 3b, the IOI values at these

k points are elevated compared to their surroundings, suggesting that the most stable decomposition may not be achieved at these values. A closer examination of

Figure 3b reveals a noticeable dip in the IOI at

. Although the LL value at this point, 3719.58, is not exceptionally high, the LL values in its vicinity remain relatively stable at a high level. Therefore,

is adopted as the estimate of

k for the second component decomposition.

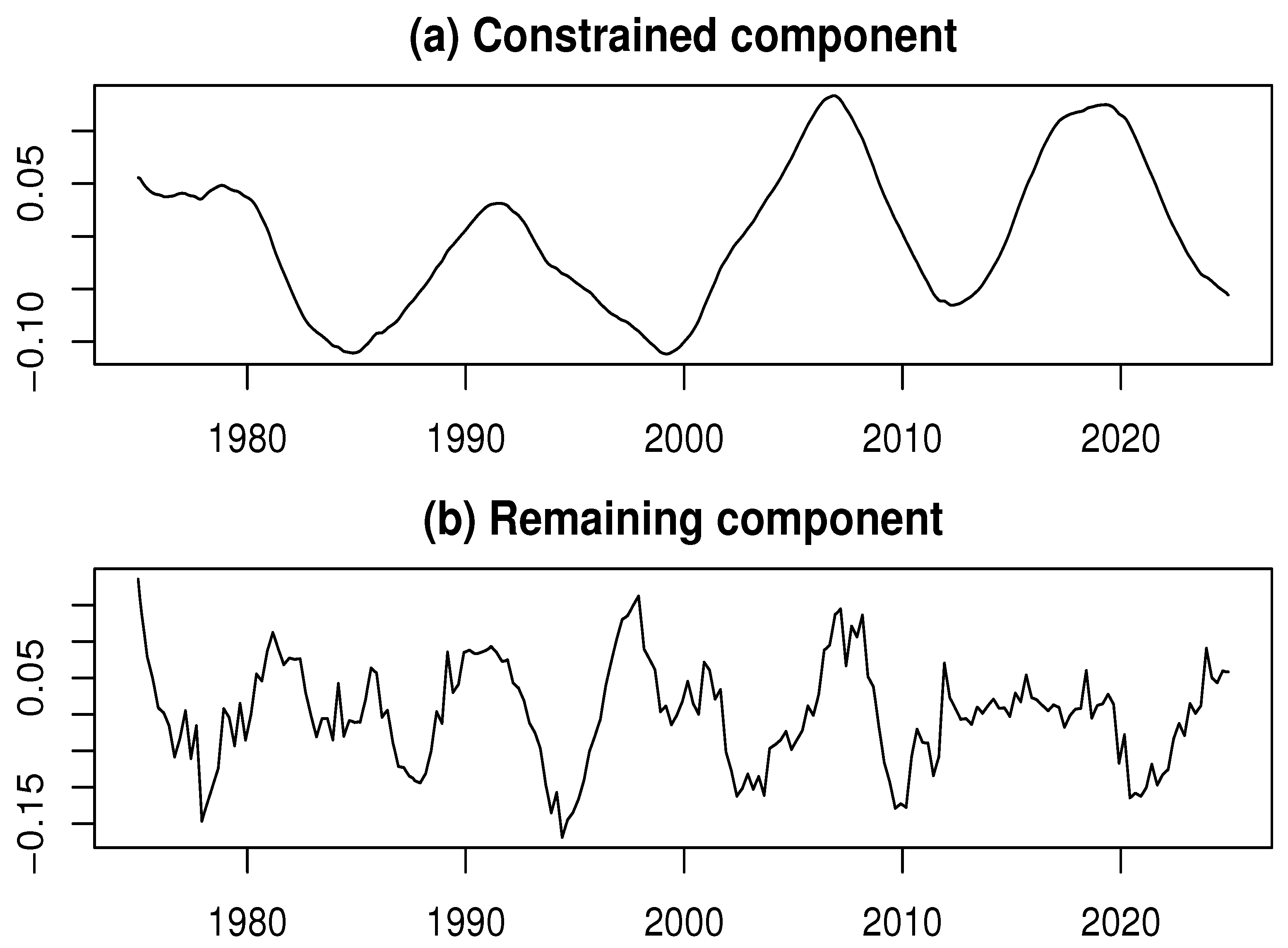

Figure 4 displays the results of the second decomposition applied to the remaining component obtained from the first decomposition.

Figure 4a,b show the constrained and remaining components, respectively.

The constrained component in the second decomposition, shown in

Figure 4a, exhibits cyclical behavior with a period of over a decade, aligning with the Juglar cycle. This point deserves emphasis: in this case, the time series subject to decomposition is itself a remaining component containing cyclical fluctuations of varying periods. Consequently, the constrained component extracted through this process captures a long-period, highly smooth cyclical fluctuation.

Furthermore, the remaining component in the second decomposition, shown in

Figure 4b, is characterized by short-term cyclical fluctuations. These findings reinforce the consistency of the results with business cycle theory and underscore the effectiveness of the proposed approach in identifying and analyzing economic cycles (see [

1]).

The results presented above suggest the following: by incorporating additional metrics and estimation methods alongside the conventional maximum likelihood approach, more stable decomposition results can be achieved. Naturally, different decomposition outcomes may arise depending on the number of components extracted and the choice of k values. This underscores the fact that data analysis is inherently both data-driven and purpose-driven; thus, trial and error, guided by the analytical objectives of the data under investigation, is essential.

4.2. Empirical Analysis of Industrial Production in Japan

In this section, we present an empirical analysis of the seasonally adjusted index of industrial production (SAIIP) in Japan as a second example. This example demonstrates the effectiveness of the reinforced EML model approach in detecting and estimating outliers in time series data.

The SAIIP data were obtained from the same source as the BE data. As SAIIP serves as a principal indicator for analyzing economic trends, it is frequently used in empirical studies. Due to its sensitivity to sudden changes in economic conditions, outliers tend to appear frequently.

To facilitate comparison with the empirical example in [

7], we use the data as a monthly time series from January 1975 to December 2022, comprising a total of

months. A logarithmic transformation is applied to the SAIIP time series, which we refer to as log-SAIIP. The objective is to analyze the time series behavior of log-SAIIP.

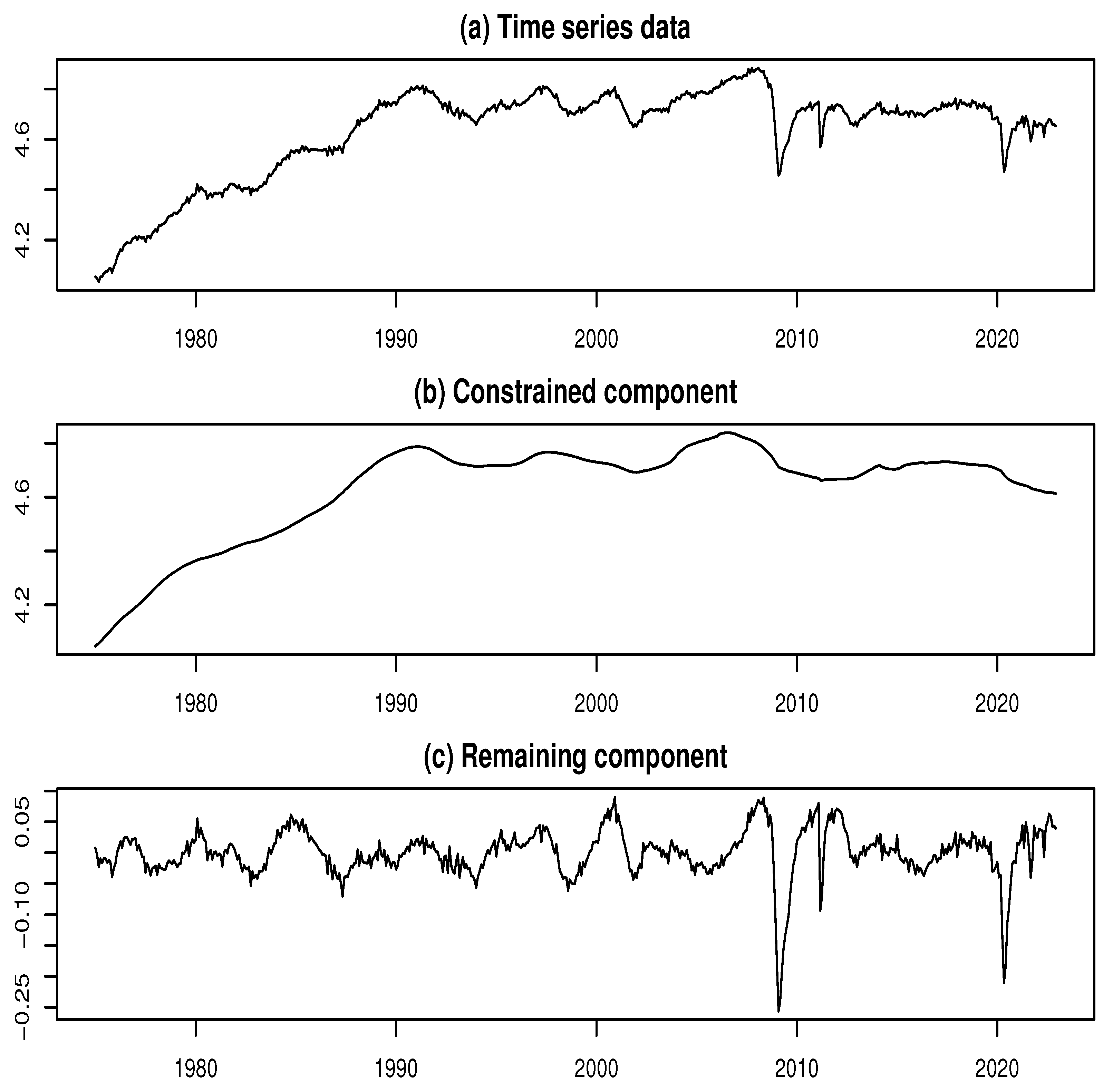

Figure 6a presents the time series plot of log-SAIIP. Two prominent declines are clearly observable in the series. The first, occurring around February 2009, is attributable to the aftermath of the 2007–2008 global financial crisis. The second, around May 2020, reflects the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. These sharp drops are likely to be associated with the presence of multiple outliers.

We applied the ML model approach to decompose the log-SAIIP time series, performing the decomposition for each value of

k ranging from 3 to 202. As shown in

Figure 5a, the log-likelihood (LL) exhibits three prominent local maxima at

,

, and

, corresponding to LL values of 4285.37, 4555.44, and 4601.83, respectively. Furthermore, at

, the LL shows a spike-like surge, reaching a peak value of 4453.67. A closer examination of

Figure 5b reveals a noticeable dip in the IOI at

, which corresponds to the first local maximum of the LL. Although the LL at this point is not the global maximum, the surrounding LL values remain relatively stable at a high level. Therefore, for the purpose of comparison with the findings of Kyo (2025b), and based on the above observation, we adopt

as the estimated value of

k for the second component decomposition.

Figure 6b,c present the results of the constrained-remaining component decomposition using the ML model approach with

. In

Figure 6b, the constrained component exhibits a smooth trend, while

Figure 6c shows that the remaining component displays cyclical variations, indicating the presence of business cycles in Japan. Notably, a substantial portion of the sharp declines observed around February 2009 and May 2020 can be attributed to the remaining component. These abrupt drops in the time series are likely to reflect the influence of outliers caused by sudden economic shocks. Therefore, the elements associated with these variations should be identified and treated as outliers, as they may distort the analysis of business cycles.

Figure 6.

Data and decomposed results for the log-SAIIP time series

Figure 6.

Data and decomposed results for the log-SAIIP time series

The upper bound for the number of potential outliers was set to , and the potential locations of the outliers were determined based on large squared values in the decomposed remaining component time series.

Furthermore, based on the AIC reduction maximization method, the number of outliers was estimated as , with the minimum AIC value being . The estimated outlier positions are at time points 410, 411, 545, 412, 413, 409, 414, 546, 547, 415, 416, 436, 435, 548, 544, 408, 149, 398, 401, 399, 397, 394, 400, and 403. Arranged in chronological order, these positions mainly correspond to the periods from December 2008 to August 2009 and from April 2020 to July 2020.

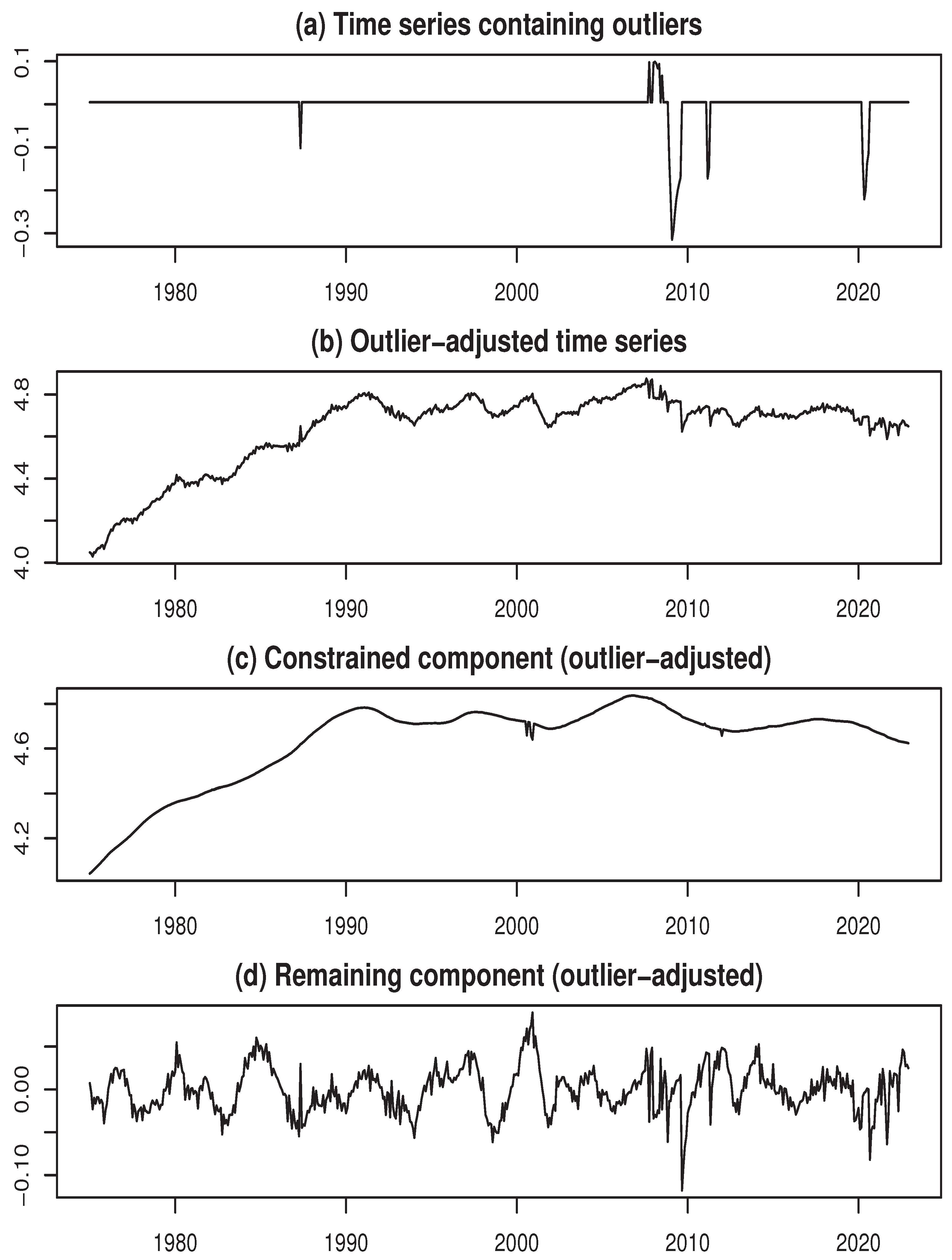

Finally, we performed the estimation of outliers using

.

Figure 7a depicts the time series containing outliers,

Figure 7b displays the final outlier-adjusted time series, while

Figure 7c,d show the estimates of the constrained and remaining components for the outlier-adjusted time series. It can be confirmed that, compared to the initial estimate of the remaining component in

Figure 6c, the estimation results with the outlier-adjusted data in

Figure 7d show a significant improvement in uniformity.

As a reference for comparison, we again present the main results obtained in [

7]. In [

7], we used an EML model approach, which is reviewed in

Section 3.3, for detecting and estimating outliers. The number of outliers was estimated as

based on the method of determining outlier locations according to the order of the squared standardized outliers, resulting in a minimum AIC value of

. The outlier positions were estimated at the following time points: 410, 411, 412, 413, 409, 414, 415, 435, 416, 545, 436, 546, 408, 149, 547, 544, 398, 394, 397, 399, 401, and 548.

Thus, by updating the method for detecting outliers, the AIC decreased by 789.62, thereby improving the reliability of the estimation results. As a result, two additional outliers were detected. These newly added outliers are active at time points 400 and 403, corresponding to April and July of 2008, respectively. The marginal contributions to the AIC reduction for each are 13.43 and 17.53, respectively. The difference between the component decomposition results obtained in [

7] and those shown in

Figure 7 is not easily visually discernible in the graph, so it will be omitted. However, as described below, a comparison based on the numerical values of the evaluation metrics is possible.

Therefore, we evaluate the decomposition results using the index of symmetry and uniformity (ISU), proposed by [

12], as a benchmark. For a given time series, the ISU is defined as the logarithmic ratio of the standard deviation of the series’ absolute values to the standard deviation of the original series. For the outlier-adjusted remaining component, a larger standard deviation of the absolute values indicates a smoother outlier-adjusted constrained component. This suggests that the influence of outliers on the decomposition result is weaker, leading to greater stability, which is desirable. Conversely, a smaller standard deviation of the absolute values implies greater symmetry around the mean and also a weaker influence of outliers on the remaining component – another desirable outcome. Therefore, the decomposition results can be evaluated using the minimum ISU criterion applied to the outlier-adjusted remaining component.

The following results were obtained based on the above findings. For the result derived from the method proposed by [

7], the ISU was

, whereas for the result based on the present AIC reduction maximization method, the ISU decreased to

. This demonstrates the advantage of the AIC reduction maximization method in updating conditions, as evaluated by the minimum ISU principle.

Considering these outcomes, a key feature of the proposed method is its thorough implementation of the ML model approach, which makes it particularly promising for handling outliers in the decomposition of constrained and remaining components.