4.1. Theoretical Implications for Research Practice and Expertise

Our research presents important theoretical insights into research practice and expertise in the AI era. AI technologies that either automate or enhance numerous technical facets of research are upending the traditional view of research expertise as a matter of technical skill. Our results indicate that research expertise is increasingly defined by what [

13] refers to as “complementary competencies”—skills that enhance, rather than replicate, AI capabilities.

These shifts in research expertise can be situated within established theoretical frameworks. The transition toward integrative, critical capacities aligns with Mode 2 Knowledge Production [

60], which describes knowledge creation as increasingly transdisciplinary and context-driven. Our three models of human-AI collaboration reflect Distributed Cognition theory [

61], where cognitive processes extend beyond individual minds into technological systems. AI tools function as Boundary Objects [

62] that translate between computational and human domains, explaining challenges in reference accuracy and interpretive alignment. The dialogue model’s iterative knowledge creation parallels Knowledge Building Theory [

63], while post-phenomenological approaches [

64,

65] illuminate how AI mediates researchers’ relationship to their objects of study. Critical Realism [

66] offers a framework for maintaining epistemological vigilance toward AI-generated outputs, recognizing them as interpretations rather than direct representations of reality.

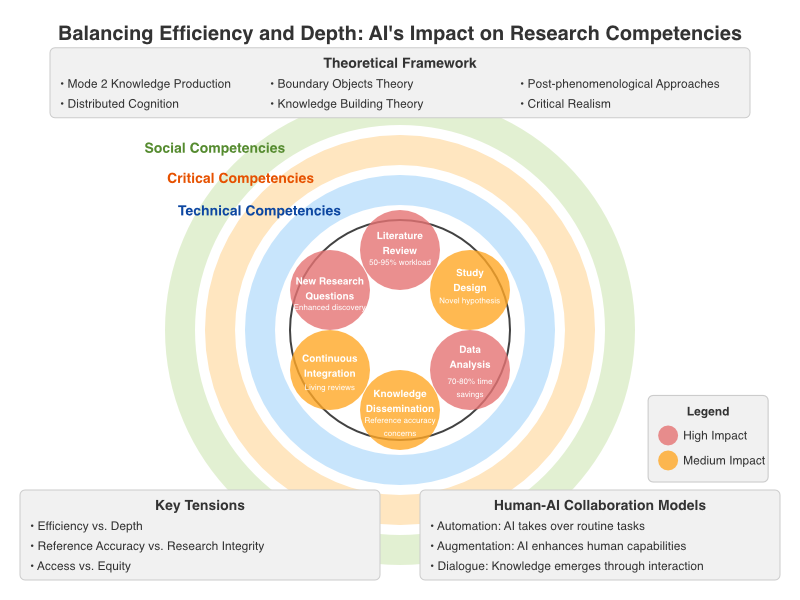

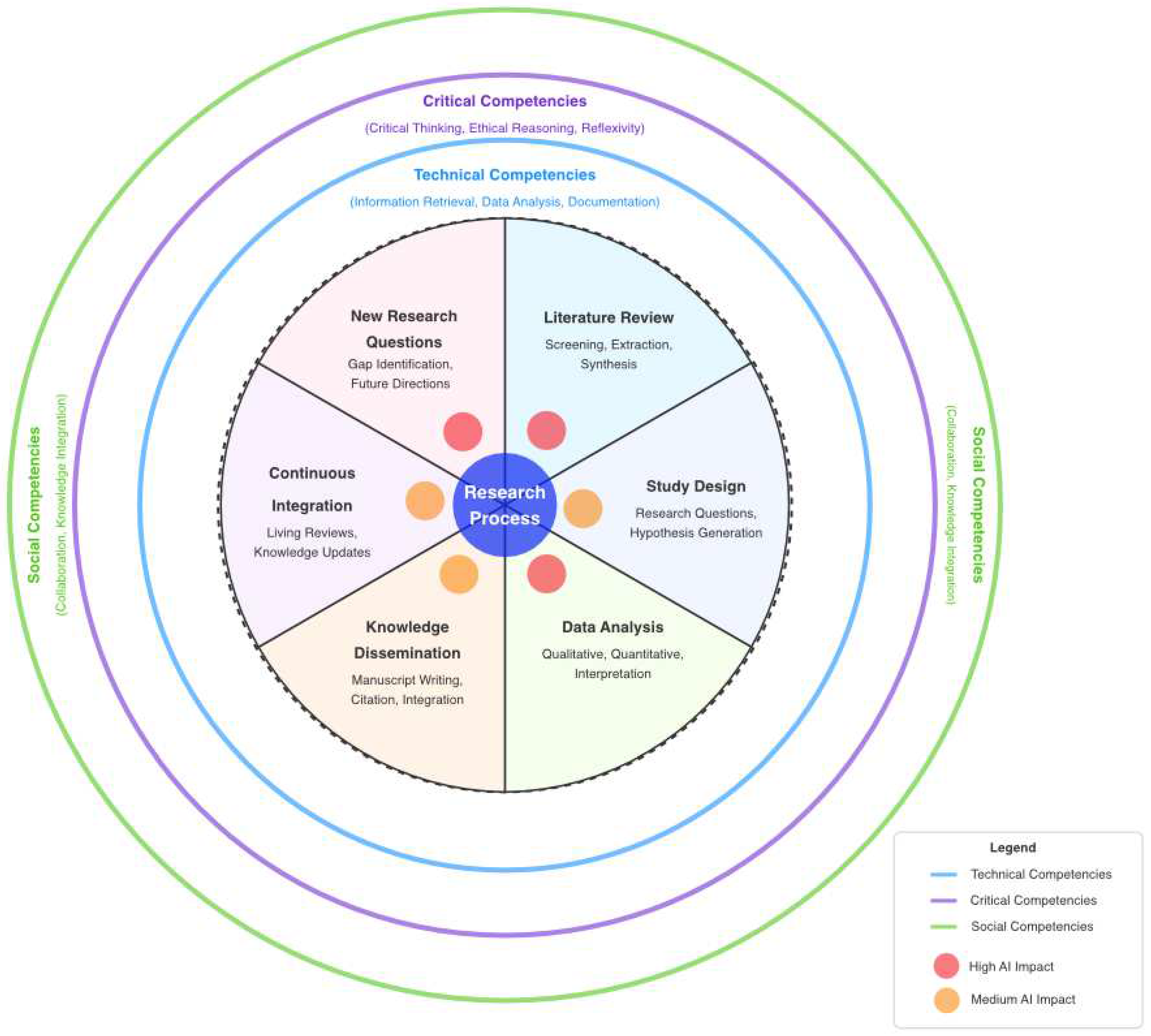

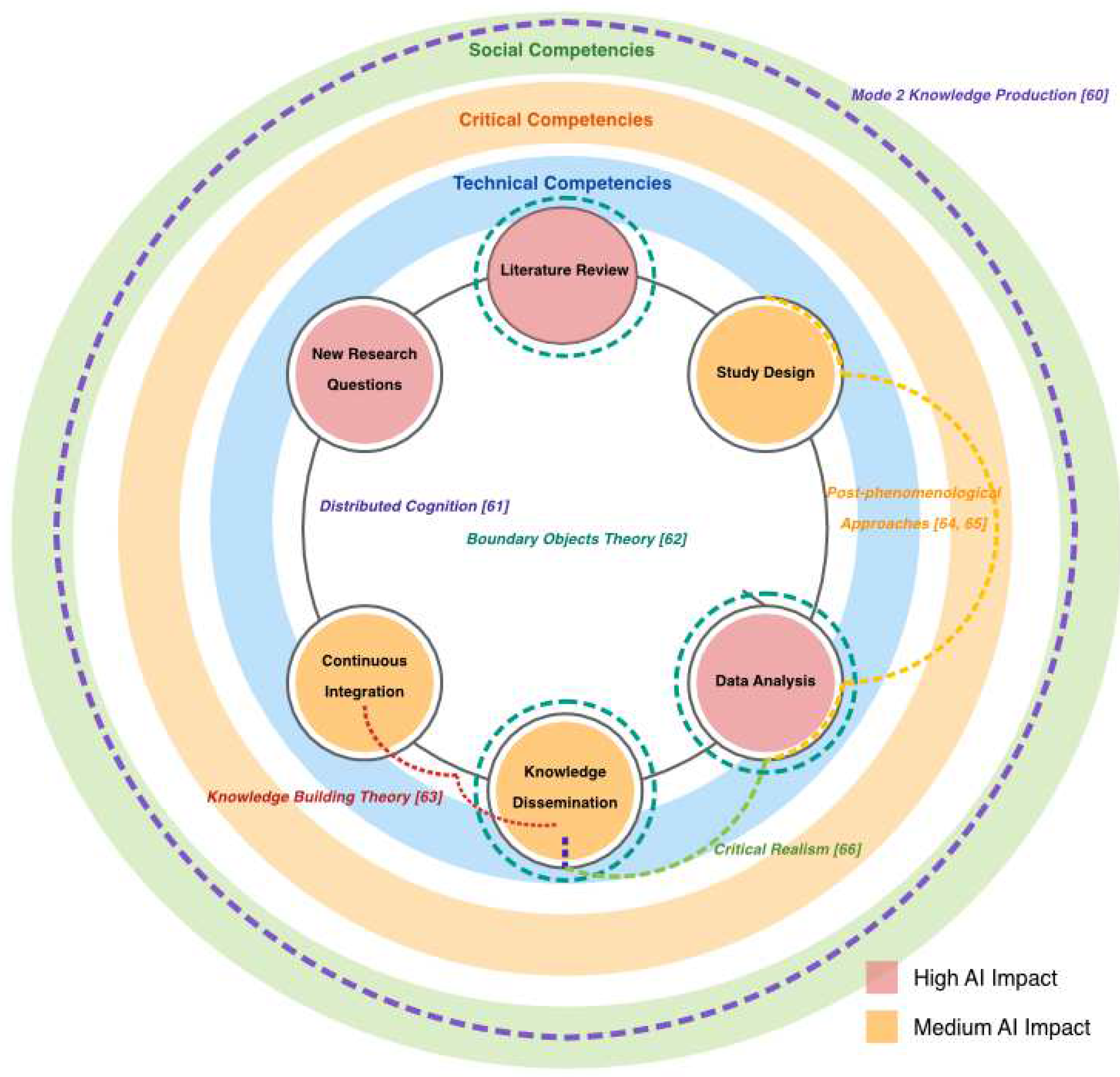

Figure 4 showcases the comprehensive conceptual framework demonstrating how artificial intelligence reshapes research processes and skills, augmented by theoretical insights clarifying these transformations. At its core, the framework outlines a six-phase research lifecycle—Literature Review, Study Design, Data Analysis, Knowledge Dissemination, Continuous Integration, and New Research Questions—surrounded by three concentric rings that represent dimensions of research competencies: technical (innermost), critical (middle), and social (outermost). Areas with high and medium AI impact are indicated by red and orange circles, with notable changes seen in Literature Review, Data Analysis, and the formulation of New Research Questions. The framework is further enhanced with theoretical overlays that offer explanatory richness: Mode 2 Knowledge Production [

60] encompasses the entire framework, highlighting the movement towards transdisciplinary research; Distributed Cognition [

61] bridges technical and critical domains, emphasizing cognitive extension into technological systems; Boundary Objects Theory [

62] focuses on human-AI interactions; Knowledge Building Theory [

63] guides collaborative advancement of knowledge; Post-phenomenological approaches [

64,

65] clarify AI’s mediating function in the perception of research; and Critical Realism [

66] fosters epistemological awareness regarding AI outputs. This theoretically-informed visualization illustrates that the integration of AI transcends mere technological adoption, signifying a profound rethinking of research expertise and the processes of knowledge creation across various fields.

These competencies encompass critical judgment regarding the suitability and limitations of AI outputs, ethical considerations for responsible AI usage, and integrative thinking spanning different disciplines.

This evolution mirrors changes in other fields where AI has reshaped professional practices. Similar to how medical expertise has transitioned from rote memorization of facts to diagnostic reasoning and clinical judgment (with medical knowledge becoming more readily available via digital tools), research expertise seems to evolve from simply executing technical tasks to focusing on critical evaluation, creative integration, and ethical reasoning.

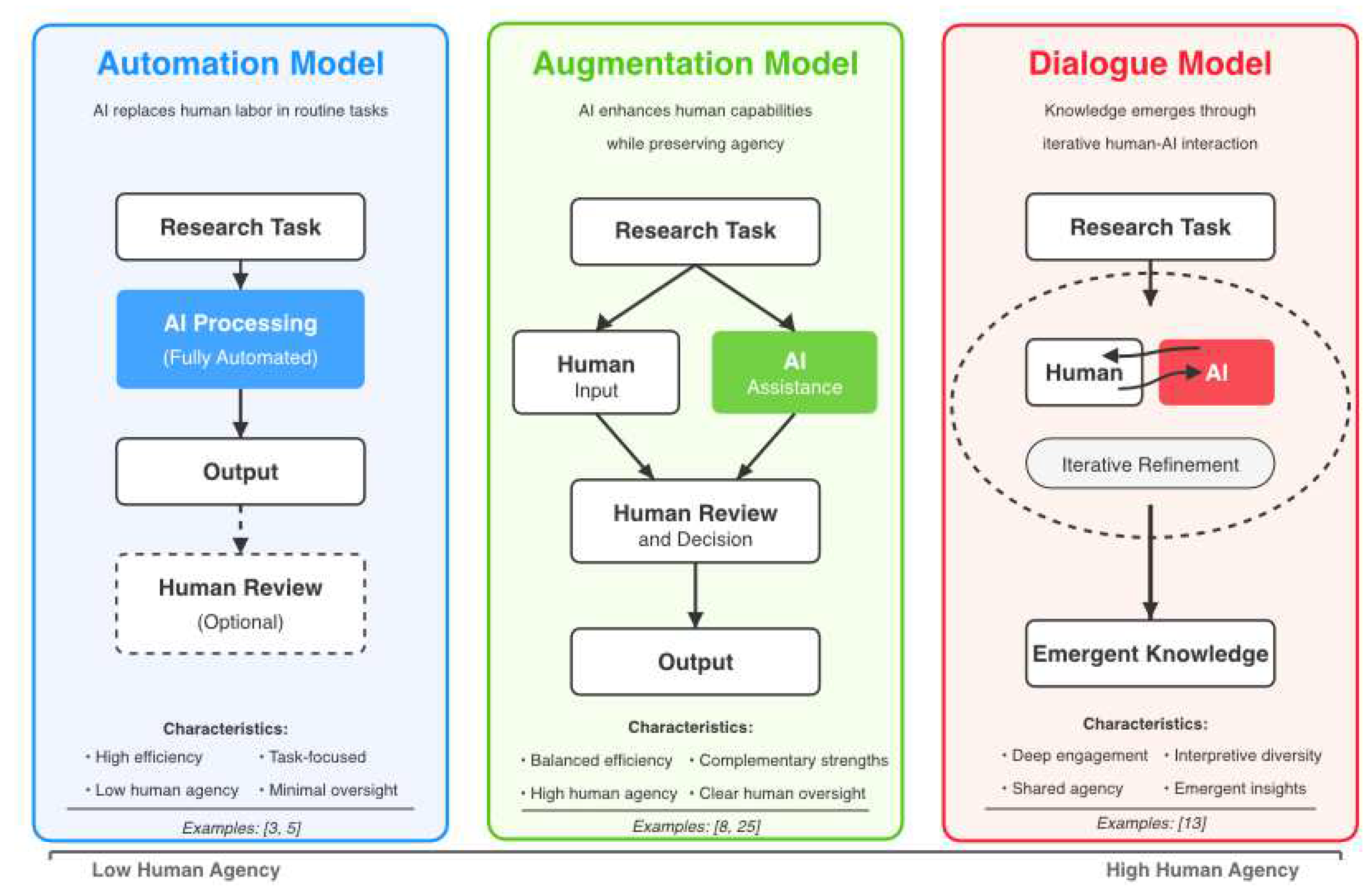

Our findings highlight several new models for human-AI collaboration in research, each with distinct impacts on researcher agency and identity. These models include “automation,” where AI tools take over routine tasks traditionally performed by humans [

3,

5]; “augmentation,” which enhances human capabilities while maintaining human agency [

8,

25]; and “dialogue,” where knowledge is developed through continuous human-AI interaction [

13].

These models propose transforming the researcher’s role from solitary knowledge creators to facilitators of complementary human and computational abilities. This change questions conventional views on individual authorship and expertise, advocating for more collaborative models of knowledge production that clearly recognize contributions from both humans and computers.

Our findings emphasize significant epistemological tensions that emerge from integrating AI into research. The efficiency and scale provided by AI tools allow for more thorough evidence synthesis and larger analyses, which could improve the breadth and overall quality of research. However, issues related to interpretive homogenization, accuracy of references, and excessive dependence on AI indicate possible compromises in depth, diversity, and originality.

These tensions illustrate the broader discussions regarding the connection between human intelligence and machine intelligence. While AI is proficient in recognizing patterns, conducting statistical analysis, and synthesizing existing knowledge, human researchers bring contextual understanding, creative insights, ethical considerations, and critical reflexivity to the table. The challenge is to create research practices that capitalize on these complementary strengths both.

4.2. Practical Implications for Balanced AI Integration

Based on our insights related to the fourth research question, we propose a framework for the balanced integration of AI into research workflows. This framework consists of three essential components, aiming to maximize benefits while tackling the identified challenges.

Firstly, research workflows must explicitly include human oversight at crucial decision-making moments, especially during research phases that involve interpretation, ethical judgment, or creative insight [

8,

13]. This entails validating AI-generated citations and references by humans, critically reviewing AI-suggested codes or themes in qualitative analysis, and ethically evaluating AI-generated hypotheses or research questions.

Secondly, researchers should implement transparent documentation practices concerning AI utilization in their research. This includes clearly explaining the specific research processes that incorporated AI, thoroughly documenting the verification methods for AI-generated content, and acknowledging the limitations and possible biases associated with AI-assisted methodologies.

Third, various research stages and fields might gain from distinct human-AI integration models. Our findings indicate that literature screening and data extraction could benefit from increased automation [

3,

5], while qualitative analysis and interpretation are best supported by more interactive, dialogue-driven methods [

8,

25]. Furthermore, hypothesis generation and research design are enhanced through augmentation approaches that uphold human creative agency [

7,

9].

4.4. Institutional Policy Considerations

Our research indicates key factors that institutions should consider when formulating AI policies. They need to create strategies that tackle potential “research divides” by ensuring fair access to AI technologies and computational resources, delivering technical support and training to researchers in various fields, and establishing a common infrastructure for AI-enhanced research.

Institutions need to establish specific guidelines for the ethical application of AI in research. This includes mandates for transparency when reporting AI use, standards for validating AI-generated content, and protocols for proper attribution and acknowledgment. Additionally, institutions should reassess their evaluation and reward systems for research, minimizing focus on metrics that AI can easily manipulate (such as the volume of publications) while emphasizing the importance of critical insight, interpretive depth, and ethical judgment. Furthermore, they should create new metrics to evaluate the responsible integration of AI.

4.6. Limitations

This systematic review has methodological limitations to consider in interpreting the findings. First, our search strategy focused on English publications, potentially excluding relevant insights from studies in other languages. This limitation may introduce biases in understanding AI’s impact across different contexts.

Second, the fast-changing landscape of AI technologies imposes a time constraint. Numerous AI tools reviewed in the studies have received substantial updates since their publication, which might restrict the relevance of specific findings to the latest versions of these technologies. Furthermore, our inclusion timeframe (2018-2025) may have overlooked earlier essential research on automation and computer-assisted research methods.

Third, there is significant variability among the studies included regarding their methodological approaches, disciplinary backgrounds, and research focuses. Although this diversity broadens the scope of our review, it also makes direct comparison and synthesis across studies more complex. Furthermore, the differing definitions of crucial concepts like “research skills” and “AI integration” pose additional difficulties for cohesive synthesis.

Fourth, most studies analyzed in this review utilized cross-sectional or short-term evaluation designs. This scarcity of longitudinal studies restricts our comprehension of how research competencies develop over time with prolonged AI exposure, as well as how initial efficiency gains or challenges may shift with continued use and enhanced literacy.

Fifth, our findings may have been influenced by publication bias, as studies that show positive or significant effects of AI on research practices are more likely to be published than those that report null or negative effects.

Finally, although systematic, our quality assessment process relied on tools designed for conventional research methodologies, which may not fully capture the unique methodological considerations of studies examining emerging technologies. Adapting the assessment criteria partially addressed this limitation, but standardized quality assessment frameworks specific to AI-human interaction studies are still in development.

Even with these limitations, the consistent results across various studies and contexts indicate that the main patterns highlighted in this review reflect strong trends in the way AI is transforming research practices and skills. Future reviews should aim to include a broader range of languages, utilize longitudinal designs, and implement standardized assessment frameworks tailored to AI’s role in research contexts.