Submitted:

05 May 2025

Posted:

08 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

Patient Demographics and Enrollment

Zinc Administration

- 1)

- mRNA and Western Immunoblot Study

- 2)

- Zinc Leaky Gut Study

Duodenal Biopsy Collection and Processing

RNA-seq Data Analysis

Western Immunoblot Analyses

Blood Sampling

D-Lactate Analyses

Results

Demographics and Zinc Administration

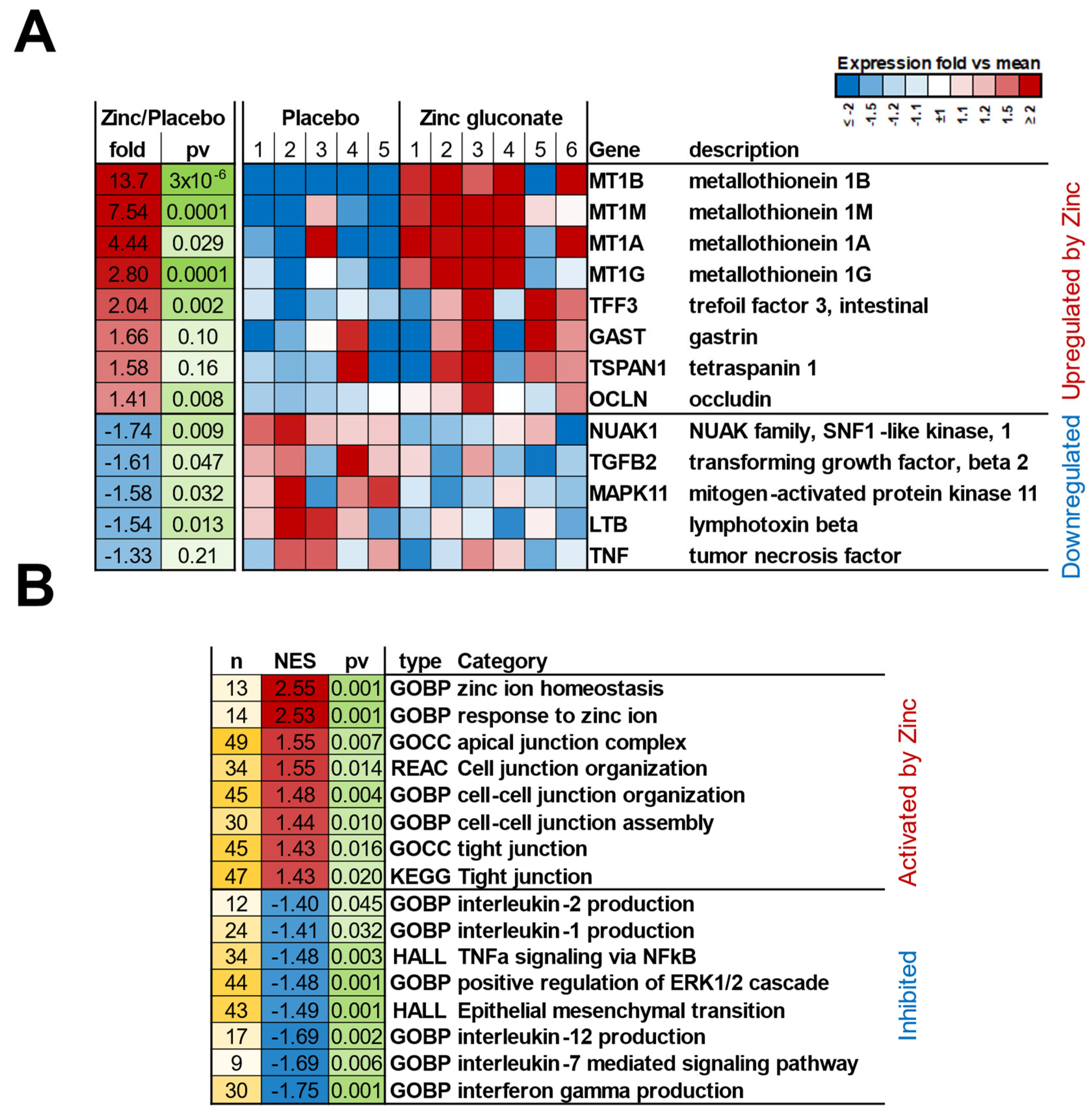

mRNA Expression

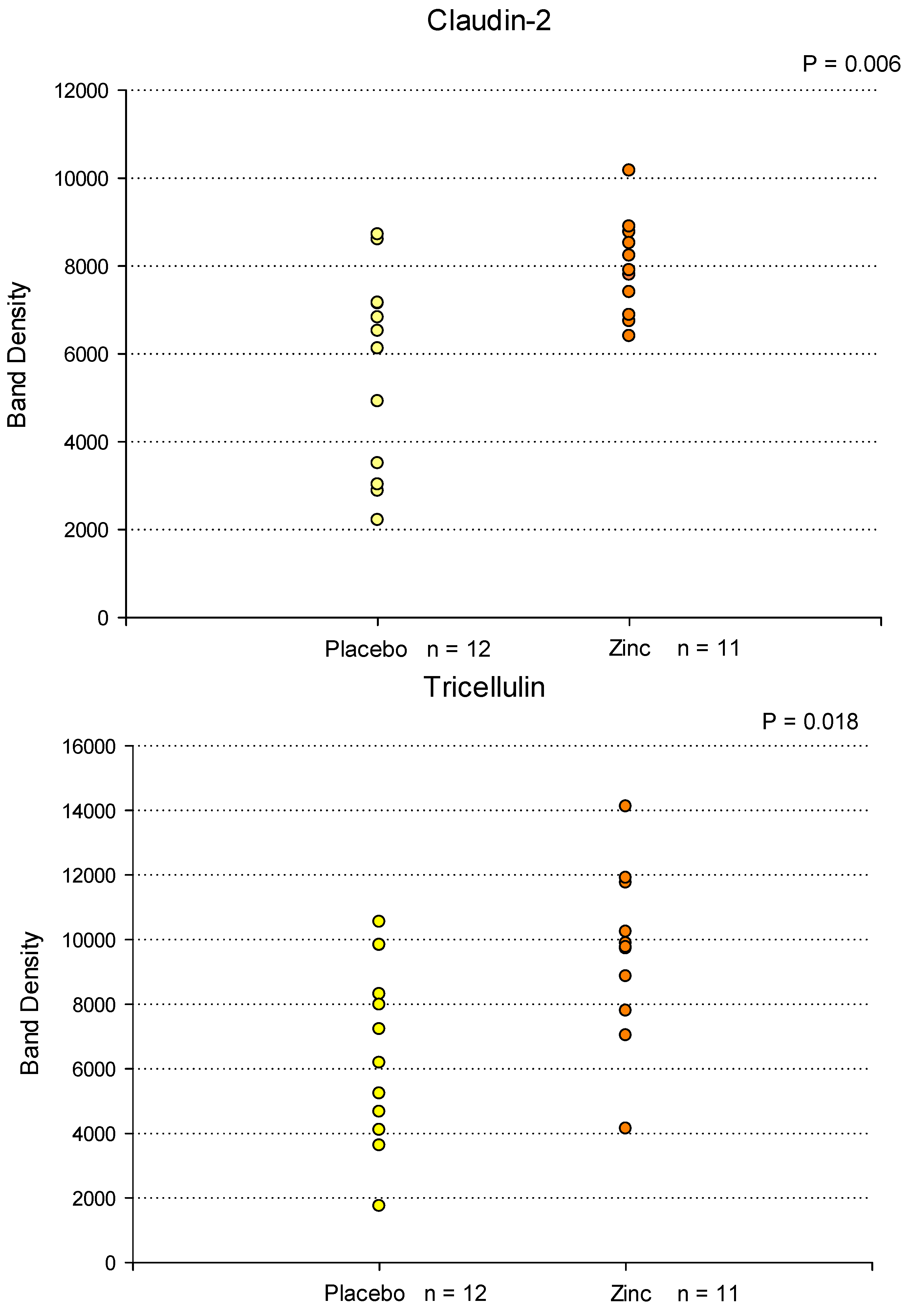

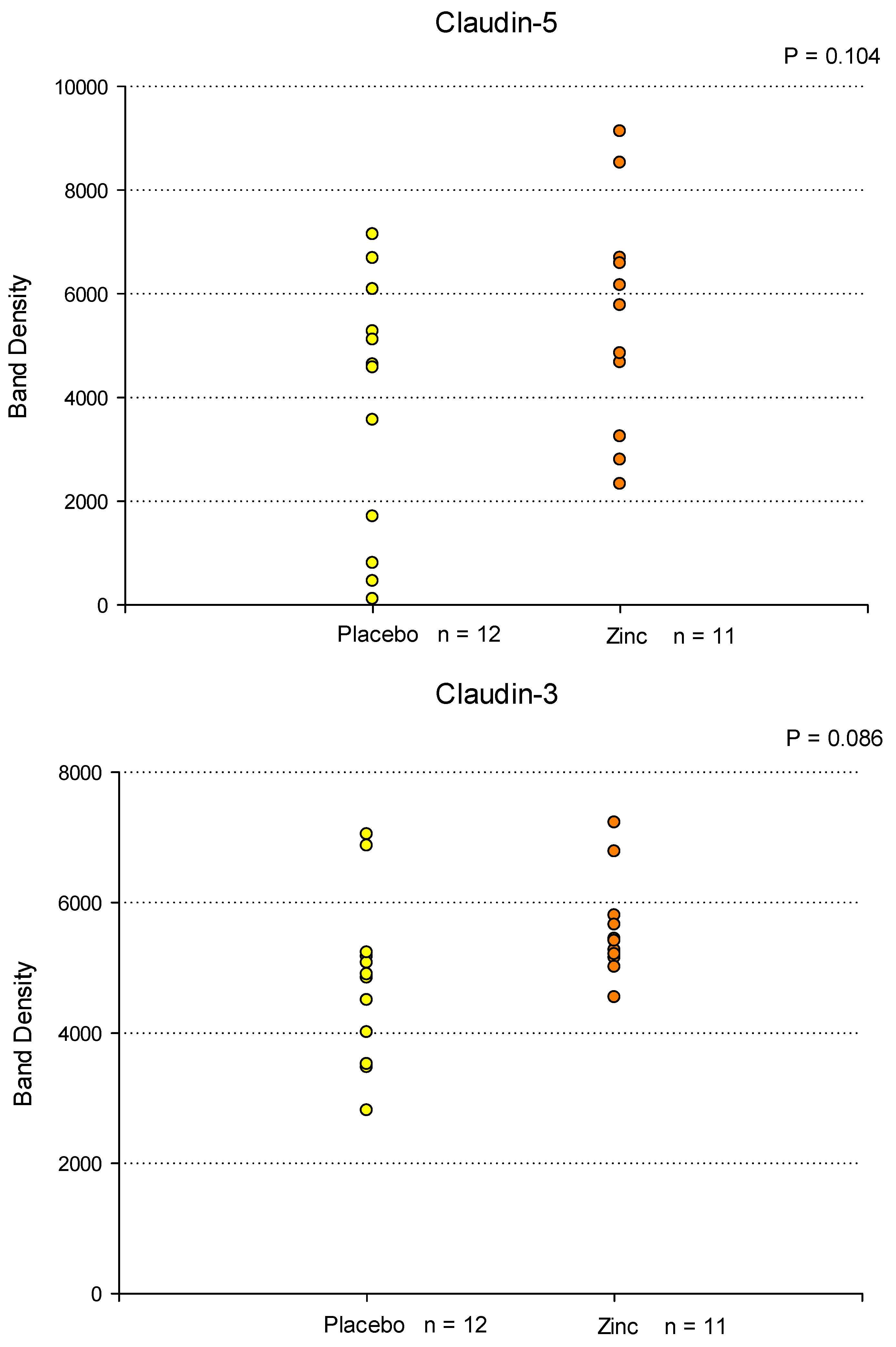

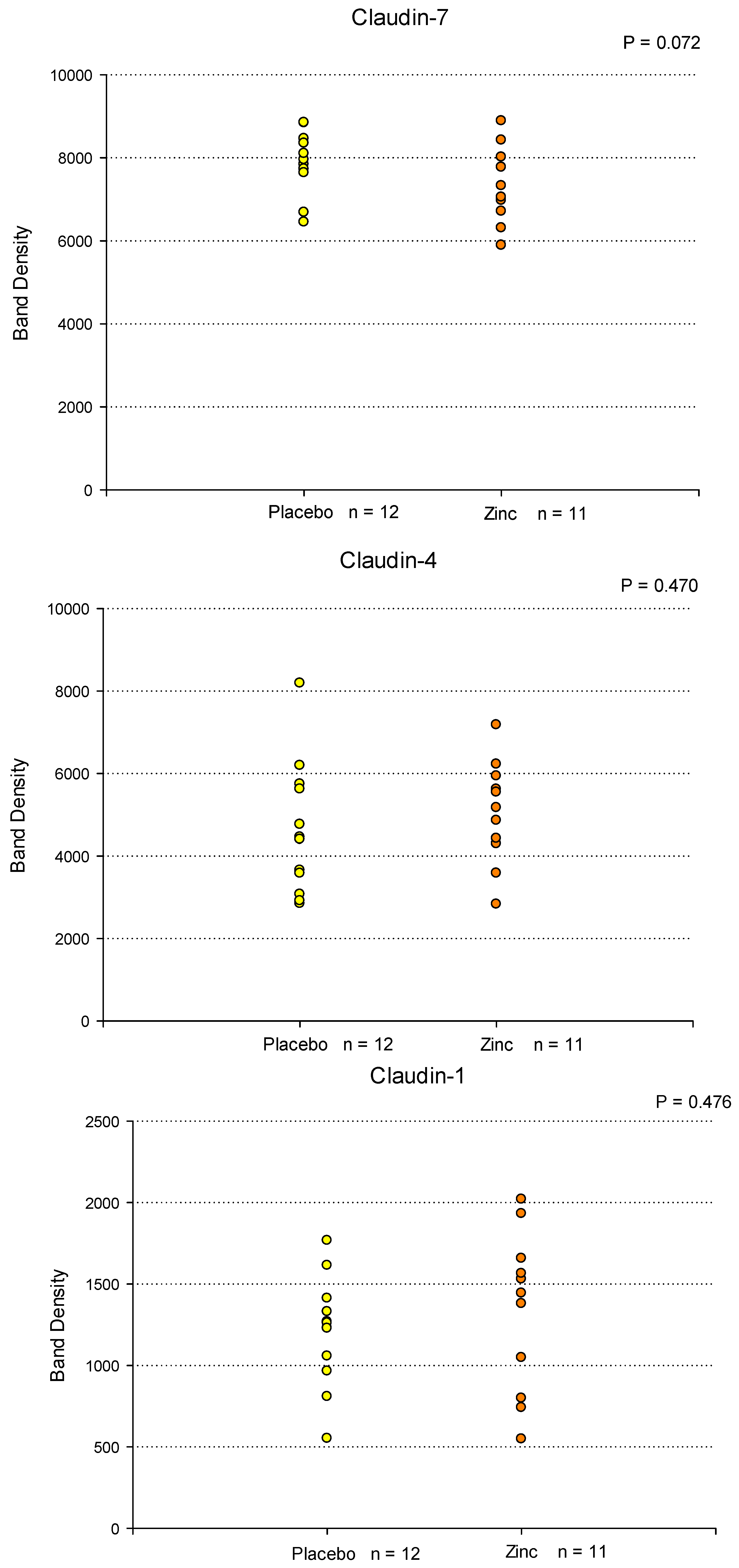

Western Immunoblot Analyses

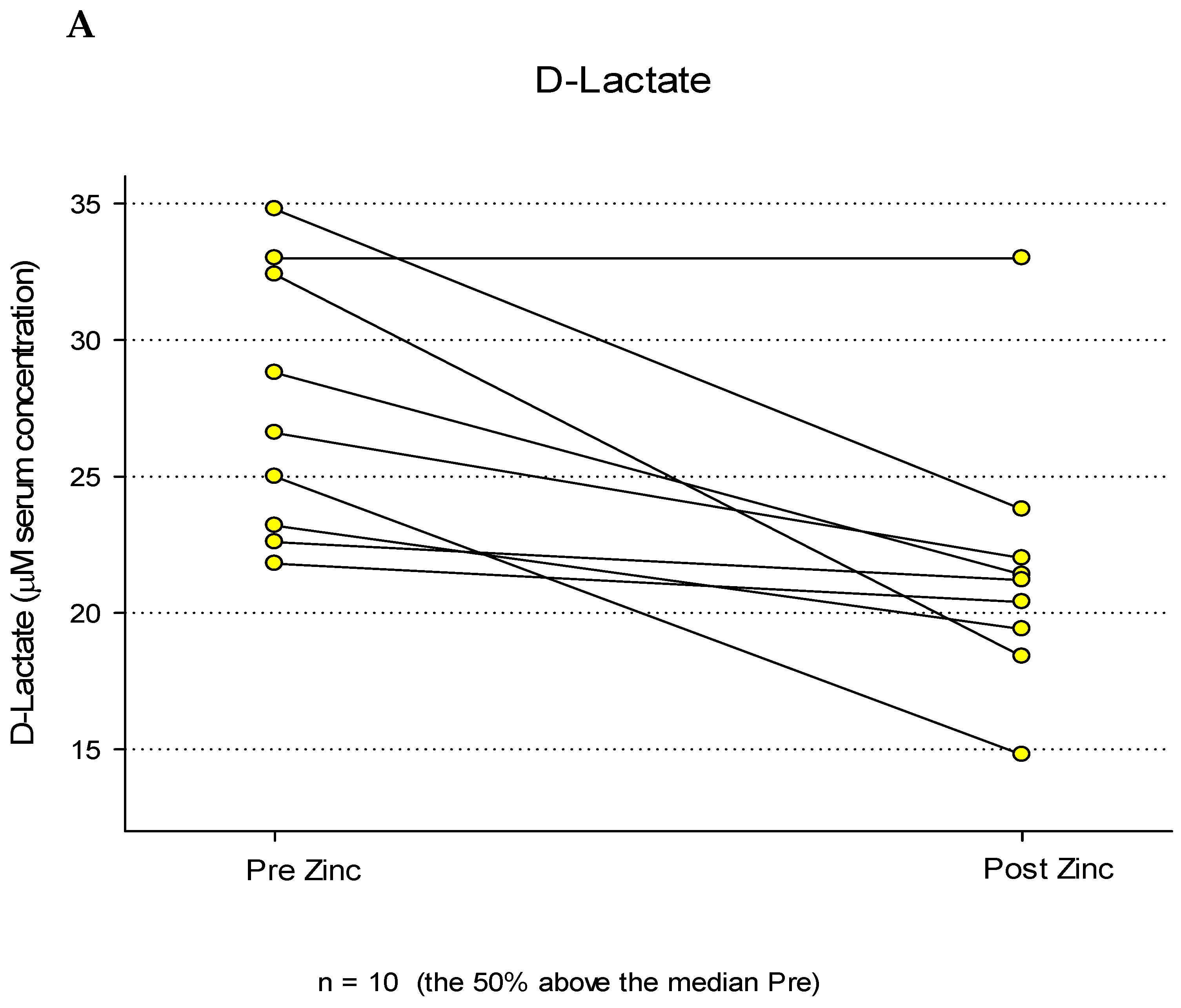

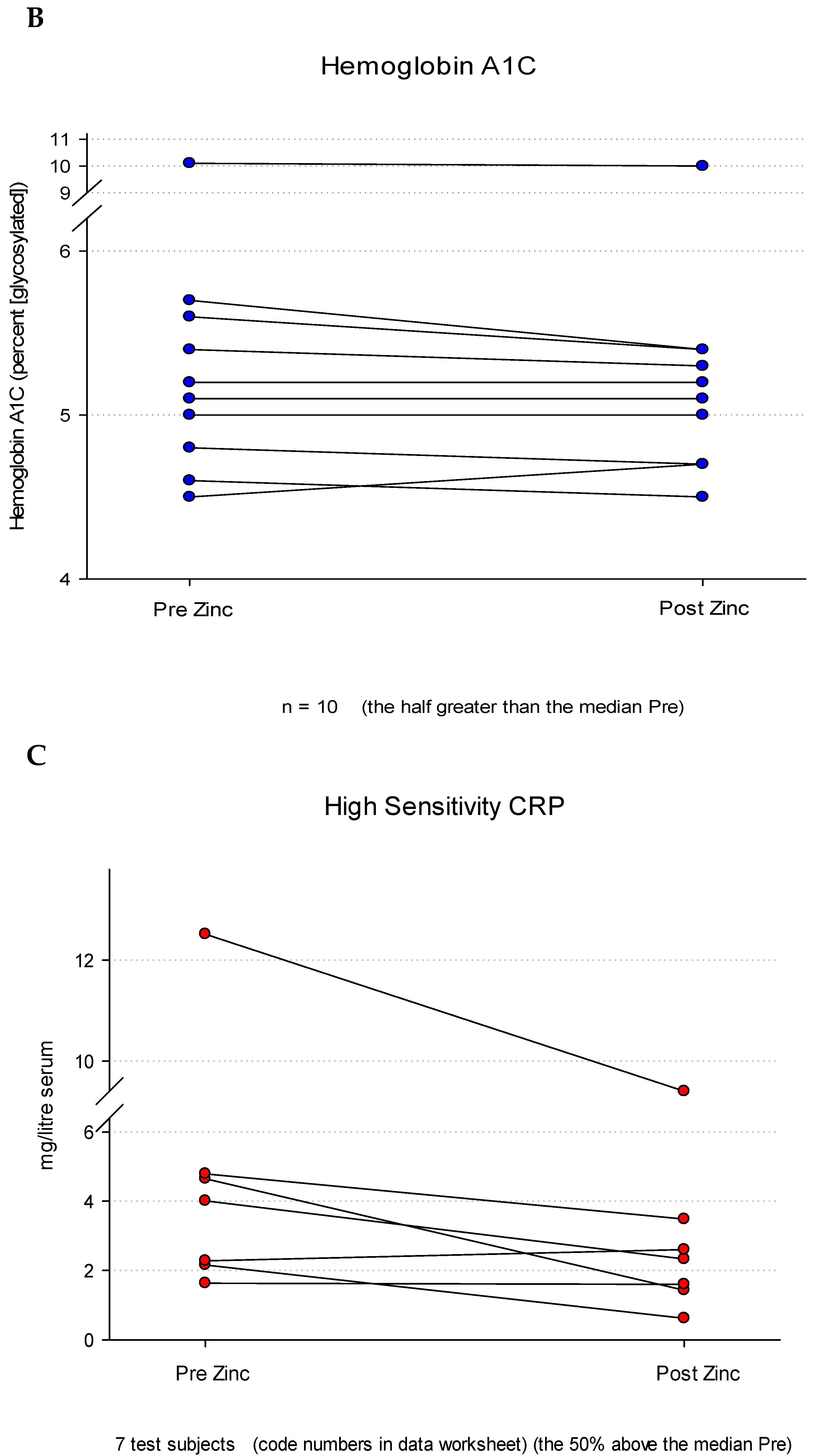

Serum D-Lactate Analyses

Discussion

Acknowledgements:

List of Abbreviations

| CRP | C-Reactive Protein |

| GERD | Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease |

| GI | Gastrointestinal |

| GSEA | Gene Set Enrichment Analysis |

| HS CRP | High Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein |

| LG | Leaky Gut |

| NSAID | Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drug |

| RDA | Recommended Daily Allowance |

| TER | Transepithelial Electrical Resistance |

| TJ | Tight Junction |

| Zn | Zinc |

References

- Guttman JA, Finlay BB. Tight junctions as targets of infectious agents. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009 Apr;1788(4):832-41. Epub 2008 Nov 14. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullin JM, Agostino N, Rendon-Huerta E, Thornton JJ. Keynote review: epithelial and endothelial barriers in human disease. Drug Discov Today. 2005 Mar 15;10(6):395-408. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson G, Kritas S, Butler R. Stressed mucosa. Nestle Nutr Workshop Ser Pediatr Program. 2007;59:133-42; discussion 143-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capaldo, CT. Claudin Barriers on the Brink: How Conflicting Tissue and Cellular Priorities Drive IBD Pathogenesis. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 ;24(10):8562. 10 May. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Soler AP, Miller RD, Laughlin KV, Carp NZ, Klurfeld DM, Mullin JM. Increased tight junctional permeability is associated with the development of colon cancer. Carcinogenesis. 1999 Aug;20(8):1425-31. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrestha A, Uzal FA, McClane BA. The interaction of Clostridium perfringens enterotoxin with receptor claudins. Anaerobe. 2016 Oct;41:18-26. Epub 2016 Apr 16. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hollander, D. Intestinal permeability, leaky gut, and intestinal disorders. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 1999 Oct;1(5):410-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Compare D, Sgamato C, Rocco A, Coccoli P, Ambrosio C, Nardone G. The Leaky Gut and Human Diseases: "Can't Fill the Cup if You Don't Plug the Holes First". Dig Dis. 2024 Jul 24:1-19. Epub ahead of print. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balkovetz, DF. Tight junction claudins and the kidney in sickness and in health. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009 Apr;1788(4):858-63. Epub 2008 Jul 16. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groeger SE, Meyle J. Epithelial barrier and oral bacterial infection. Periodontol 2000. 2015 Oct;69(1):46-67. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wittekindt, OH. Tight junctions in pulmonary epithelia during lung inflammation. Pflugers Arch. 2017 Jan;469(1):135-147. Epub 2016 Dec 5. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang M, Li H, Wang F. Roles of Transepithelial Electrical Resistance in Mechanisms of Retinal Pigment Epithelial Barrier and Retinal Disorders. Discov Med. 2022 Jul- Aug;34(171):19-24. [PubMed]

- John LJ, Fromm M, Schulzke JD. Epithelial barriers in intestinal inflammation. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011 Sep 1;15(5):1255-70. Epub 2011 May 11. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, T. Regulation of intestinal epithelial permeability by tight junctions. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013 Feb;70(4):631-59. Epub 2012 Jul 11. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Köhler CA, Maes M, Slyepchenko A, Berk M, Solmi M, Lanctôt KL, Carvalho AF. The Gut- Brain Axis, Including the Microbiome, Leaky Gut and Bacterial Translocation: Mechanisms and Pathophysiological Role in Alzheimer's Disease. Curr Pharm Des. 2016;22(40):6152- 6166. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu CA, Hou Y, Yi D, Qiu Y, Wu G, Kong X, Yin Y. Autophagy and tight junction proteins in the intestine and intestinal diseases. Anim Nutr. 2015 Sep;1(3):123-127. Epub 2015 Sep 1. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- DiGuilio KM, Del Rio EA, Harty RN, Mullin JM. Micronutrients at Supplemental Levels, Tight Junctions and Epithelial Barrier Function: A Narrative Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2024 Mar 19;25(6):3452. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vargas-Robles H, Castro-Ochoa KF, Citalán-Madrid AF, Schnoor M. Beneficial effects of nutritional supplements on intestinal epithelial barrier functions in experimental colitis models in vivo. World J Gastroenterol. 2019 Aug 14;25(30):4181-4198. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hering NA, Schulzke JD. Therapeutic options to modulate barrier defects in inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis. 2009;27(4):450-4. Epub 2009 Nov 4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callaghan PJ, Rybakovsky E, Ferrick B, Thomas S, Mullin JM. Retinoic acid improves baseline barrier function and attenuates TNF-α-induced barrier leak in human bronchial epithelial cell culture model, 16HBE 14o. PLoS One. 2020 Dec 10;15(12):e0242536. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rybakovsky E, DiGuilio KM, Valenzano MC, Geagan S, Pham K, Harty RN, Mullin JM. Calcitriol modifies tight junctions, improves barrier function, and reduces TNF-α-induced barrier leak in the human lung-derived epithelial cell culture model, 16HBE 14o. Physiol Rep. 2023 Apr;11(7):e15592. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang B, Guo Y. Supplemental zinc reduced intestinal permeability by enhancing occludin and zonula occludens protein-1 (ZO-1) expression in weaning piglets. Br J Nutr. 2009 Sep;102(5):687-93. Epub 2009 Mar 9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sturniolo GC, Di Leo V, Ferronato A, D'Odorico A, D'Incà R. Zinc supplementation tightens "leaky gut" in Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2001 May;7(2):94-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrell CP, Morgan M, Rudolph DS, Hwang A, Albert NE, Valenzano MC, Wang X, Mercogliano G, Mullin JM. Proton Pump Inhibitors Interfere With Zinc Absorption and Zinc Body Stores. Gastroenterology Res. 2011 Dec;4(6):243-251. Epub 2011 Nov 20. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fosmire, GJ. Zinc toxicity. Am J Clin Nutr. 1990 Feb;51(2):225-7. [CrossRef]

- Samman S, Roberts DC. The effect of zinc supplements on plasma zinc and copper levels and the reported symptoms in healthy volunteers. Med J Aust. 1987 Mar 2;146(5):246-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogden JD, Oleske JM, Lavenhar MA, Munves EM, Kemp FW, Bruening KS, Holding KJ, Denny TN, Guarino MA, Krieger LM, et al. Zinc and immunocompetence in elderly people: effects of zinc supplementation for 3 months. Am J Clin Nutr. 1988 Sep;48(3):655-63. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraga CG, Oteiza PI, Keen CL. Trace elements and human health. Mol Aspects Med. 2005 Aug-Oct;26(4-5):233-4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karam, SM. Lineage commitment and maturation of epithelial cells in the gut. Front Biosci. 1999 Mar 15;4:D286-98. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, Drenkow J, Zaleski C, Jha S, Batut P, Chaisson M, Gingeras TR. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013 Jan 1;29(1):15-21. Epub 2012 Oct 25. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Li B, Dewey CN. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011 Aug 4;12:323. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA- seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15(12):550. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, Paulovich A, Pomeroy SL, Golub TR, Lander ES, Mesirov JP. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge- based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005 Oct 25;102(43):15545-50. Epub 2005 Sep 30. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Aldridge GM, Podrebarac DM, Greenough WT, Weiler IJ. The use of total protein stains as loading controls: an alternative to high-abundance single-protein controls in semi-quantitative immunoblotting. J Neurosci Methods. 2008 Jul 30;172(2):250-4. Epub 2008 May 15. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Valenzano MC, Rybakovsky E, Chen V, Leroy K, Lander J, Richardson E, Yalamanchili S, McShane S, Mathew A, Mayilvaganan B, Connor L, Urbas R, Huntington W, Corcoran A, Trembeth S, McDonnell E, Wong P, Newman G, Mercogliano G, Zitin M, Etemad B, Thornton J, Daum G, Raines J, Kossenkov A, Fong LY, Mullin JM. Zinc Gluconate Induces Potentially Cancer Chemopreventive Activity in Barrett's Esophagus: A Phase 1 Pilot Study. Dig Dis Sci. 2021 Apr;66(4):1195-1211. Epub 2020 May 15. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Murray MJ, Barbose JJ, Cobb CF. Serum D(-)-lactate levels as a predictor of acute intestinal ischemia in a rat model. J Surg Res. 1993 May;54(5):507-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Mageed AB, Oehme FW. The effect of various dietary zinc concentrations on the biological interactions of zinc, copper, and iron in rats. Biol Trace Elem Res. 1991 Jun;29(3):239-56. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segawa S, Shibamoto M, Ogawa M, Miyake S, Mizumoto K, Ohishi A, Nishida K, Nagasawa, K. The effect of divalent metal cations on zinc uptake by mouse Zrt/Irt-like protein 1 (ZIP1). Life Sci. 2014 Sep 15;113(1-2):40-4. Epub 2014 Jul 31. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robles-Osorio ML, Sabath E. Tight junction disruption and the pathogenesis of the chronic complications of diabetes mellitus: A narrative review. World J Diabetes. 2023 Jul 15;14(7):1013-1026. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chegini Z, Noei M, Hemmati J, Arabestani MR, Shariati A. The destruction of mucosal barriers, epithelial remodeling, and impaired mucociliary clearance: possible pathogenic mechanisms of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus in chronic rhinosinusitis. Cell Commun Signal. 2023 Oct 30;21(1):306. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yang YF, Shen YD. Choroid plexus and its relations with age-related diseases. Yi Chuan. 2024 Feb 20;46(2):109-125. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berni Canani R, Caminati M, Carucci L, Eguiluz-Gracia I. Skin, gut, and lung barrier: Physiological interface and target of intervention for preventing and treating allergic diseases. Allergy. 2024 Jun;79(6):1485-1500. Epub 2024 Mar 4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiGuilio KM, Rybakovsky E, Abdavies R, Chamoun R, Flounders CA, Shepley-McTaggart A, Harty RN, Mullin JM. Micronutrient Improvement of Epithelial Barrier Function in Various Disease States: A Case for Adjuvant Therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Mar 10;23(6):2995. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Paterson BM, Lammers KM, Arrieta MC, Fasano A, Meddings JB. The safety, tolerance, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic effects of single doses of AT-1001 in coeliac disease subjects: a proof of concept study. Aliment PharmacolTher. 2007 Sep 1;26(5):757-66. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenner H, Holleczek B, Schöttker B. Vitamin D Insufficiency and Deficiency and Mortality from Respiratory Diseases in a Cohort of Older Adults: Potential for Limiting the Death Toll during and beyond the COVID-19 Pandemic? Nutrients. 2020 Aug 18;12(8):2488. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Obrenovich MEM. Leaky Gut, Leaky Brain? Microorganisms. 2018 Oct 18;6(4):107. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wasiak J, Gawlik-Kotelnicka O. Intestinal permeability and its significance in psychiatric disorders - A narrative review and future perspectives. Behav Brain Res. 2023 Jun 25;448:114459. Epub 2023 Apr 29. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown GC, Heneka MT. The endotoxin hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease. Mol Neurodegener. 2024 Apr 1;19(1):30. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lamberti LM, Walker CL, Chan KY, Jian WY, Black RE. Oral zinc supplementation for the treatment of acute diarrhea in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients. 2013 Nov 21;5(11):4715-40. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Amasheh M, Andres S, Amasheh S, Fromm M, Schulzke JD. Barrier effects of nutritional factors. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009 May;1165:267-73. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skrovanek S, DiGuilio K, Bailey R, Huntington W, Urbas R, Mayilvaganan B, Mercogliano G, Mullin JM. Zinc and gastrointestinal disease. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol. 2014 Nov 15;5(4):496-513. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang X, Valenzano MC, Mercado JM, Zurbach EP, Mullin JM. Zinc supplementation modifies tight junctions and alters barrier function of CACO-2 human intestinal epithelial layers. Dig Dis Sci. 2013 Jan;58(1):77-87. Epub 2012 Aug 19. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valenzano MC, DiGuilio K, Mercado J, Teter M, To J, Ferraro B, Mixson B, Manley I, Baker V, Moore BA, Wertheimer J, Mullin JM. Remodeling of Tight Junctions and Enhancement of Barrier Integrity of the CACO-2 Intestinal Epithelial Cell Layer by Micronutrients. PLoS One. 2015 Jul 30;10(7):e0133926. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shao Y, Wolf PG, Guo S, Guo Y, Gaskins HR, Zhang B. Zinc enhances intestinal epithelial barrier function through the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway in Caco-2 cells. J Nutr Biochem. 2017 May;43:18-26. Epub 2017 Jan 31. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buddington RK, Wong T, Howard SC. Paracellular Filtration Secretion Driven by Mechanical Force Contributes to Small Intestinal Fluid Dynamics. Med Sci (Basel). 2021 Feb 9;9(1):9. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hu C, Song J, Li Y, Luan Z, Zhu K. Diosmectite-zinc oxide composite improves intestinal barrier function, modulates expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and tight junction protein in early weaned pigs. Br J Nutr. 2013 Aug;110(4):681-8. Epub 2013 Jan 11. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guthrie GJ, Aydemir TB, Troche C, Martin AB, Chang SM, Cousins RJ. Influence of ZIP14 (slc39A14) on intestinal zinc processing and barrier function. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2015 Feb 1;308(3):G171-8. Epub 2014 Nov 26. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fan P, Tan Y, Jin K, Lin C, Xia S, Han B, Zhang F, Wu L, Ma X. Supplemental lipoic acid relieves post-weaning diarrhoea by decreasing intestinal permeability in rats. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr (Berl). 2017 Feb;101(1):136-146. Epub 2015 Dec 31. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranaldi G, Caprini V, Sambuy Y, Perozzi G, Murgia C. Intracellular zinc stores protect the intestinal epithelium from Ochratoxin A toxicity. Toxicol In Vitro. 2009 Dec;23(8):1516-21. Epub 2009 Aug 29. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roselli M, Finamore A, Garaguso I, Britti MS, Mengheri E. Zinc oxide protects cultured enterocytes from the damage induced by Escherichia coli. J Nutr. 2003 Dec;133(12):4077-82. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhry N, Scott F, Edgar M, Sanger GJ, Kelly P. Reversal of Pathogen-Induced Barrier Defects in Intestinal Epithelial Cells by Contra-pathogenicity Agents. Dig Dis Sci. 2021 Jan;66(1):88-104. Epub 2020 Feb 7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar P, Saha T, Sheikh IA, Chakraborty S, Aoun J, Chakrabarti MK, Rajendran VM, Ameen NA, Dutta S, Hoque KM. Zinc ameliorates intestinal barrier dysfunctions in shigellosis by reinstating claudin-2 and -4 on the membranes. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2019 Feb 1;316(2):G229-G246. Epub 2018 Nov 8. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Song ZH, Ke YL, Xiao K, Jiao LF, Hong QH, Hu CH. Diosmectite-zinc oxide composite improves intestinal barrier restoration and modulates TGF-β1, ERK1/2, and Akt in piglets after acetic acid challenge. J Anim Sci. 2015 Apr;93(4):1599-607. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camilleri, M. Human Intestinal Barrier: Effects of Stressors, Diet, Prebiotics, and Probiotics. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2021 Jan 25;12(1):e00308. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Davison G, Marchbank T, March DS, Thatcher R, Playford RJ. Zinc carnosine works with bovine colostrum in truncating heavy exercise-induced increase in gut permeability in healthy volunteers. Am J aClin Nutr. 2016 Aug;104(2):526-36. Epub 2016 Jun 29. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy SK, Behrens RH, Haider R, Akramuzzaman SM, Mahalanabis D, Wahed MA, Tomkins AM. Impact of zinc supplementation on intestinal permeability in Bangladeshi children with acute diarrhoea and persistent diarrhoea syndrome. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1992 Oct;15(3):289-96. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam J, Nuzhat S, Billal SM, Ahmed T, Khan AI, Hossain MI. Nutritional Profiles and Zinc Supplementation among Children with Diarrhea in Bangladesh. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2023 Feb 27;108(4):837-843. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| A. RNA Microarray Study | ||

| 1. Placebo Group (n = 5) | ||

| a. Mean age: 71.6 (range: 64 - 79) | ||

| b. Gender distribution: 2 male, 3 female | ||

| c. Racial composition: 5 Caucasian | ||

| 2. Zn-Treated Group (n = 6) | ||

| a. Mean age: 71.0 (range: 61 - 76) | ||

| b. Gender distribution: 1 male, 5 female | ||

| c. Racial composition: 5 Caucasian, 1 Afr. American | ||

| B. Western Immunoblot Study | ||

| 1. Placebo Group (n = 12) | ||

| a. Mean age: 68 (range: 55 - 78) | ||

| b. Gender distribution: 7 males, 5 females | ||

| c. Racial composition: 12 Caucasian | ||

| 2. Zn-Treated Group (n = 11) | ||

| a. Mean age: 68 (range: 54 - 75) | ||

| b. Gender distribution: 5 males, 6 females | ||

| c. Racial composition: 10 Caucasian, 1 Afr. American | ||

| C. Serum D-Lactate Study (n = 19) | ||

| 1. Mean age: 44.0 (range: 21 - 71) | ||

| 2. Gender distribution: 11 male, 8 female | ||

| 3. Racial composition: 16 Caucasian, 2 African American, 1 Asian |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).