Submitted:

06 May 2025

Posted:

07 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

Results

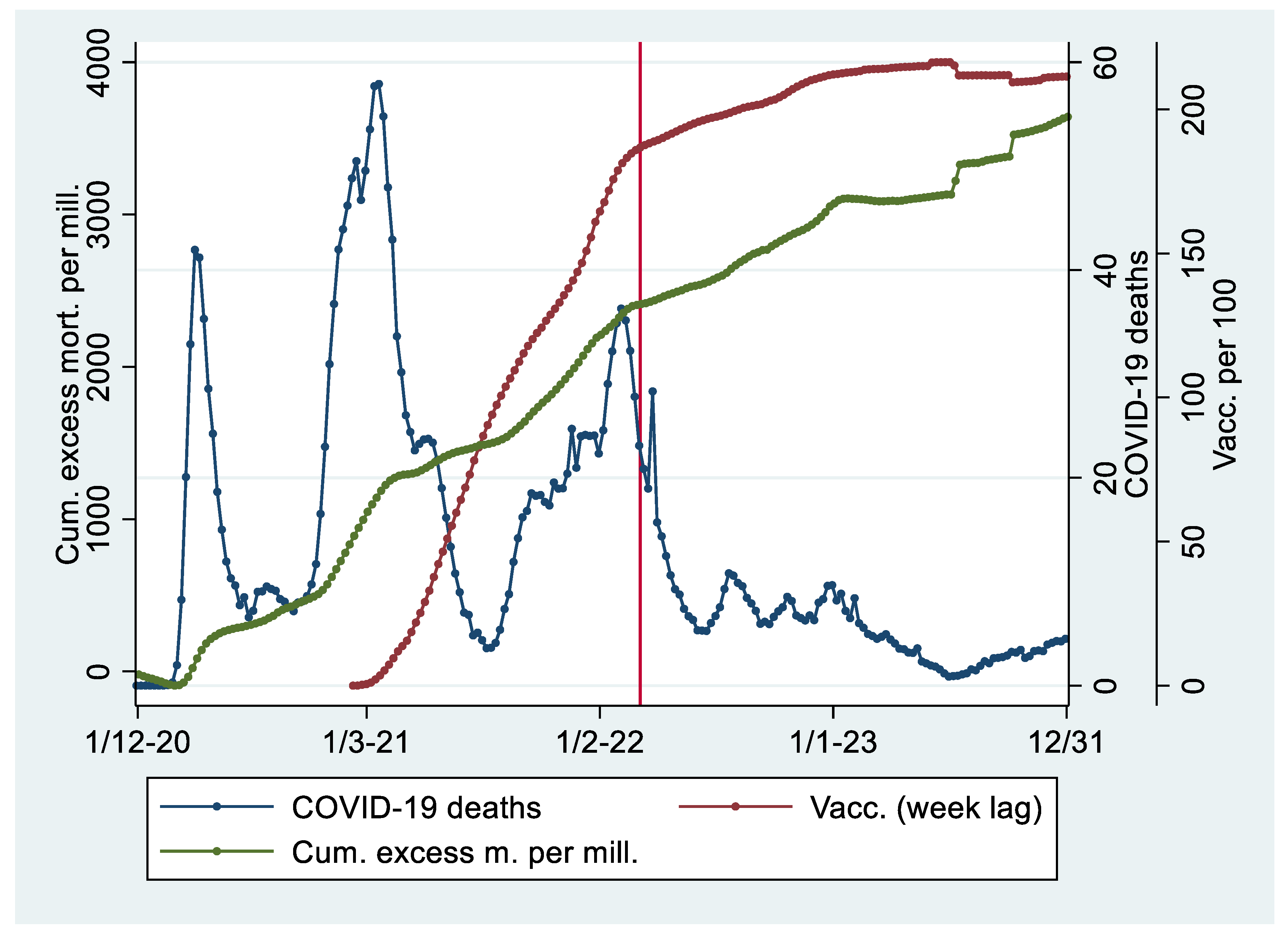

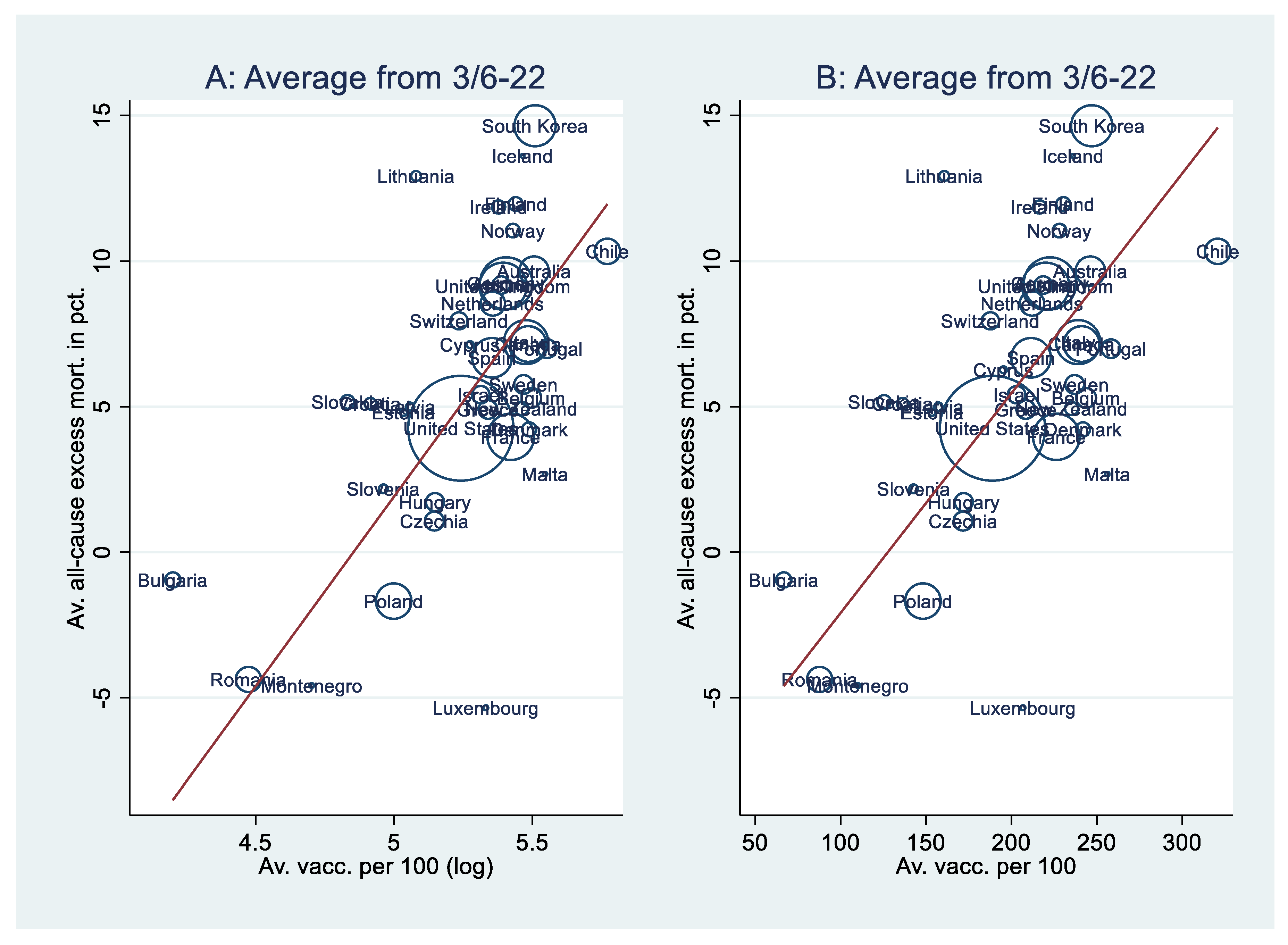

Descriptive Statistics

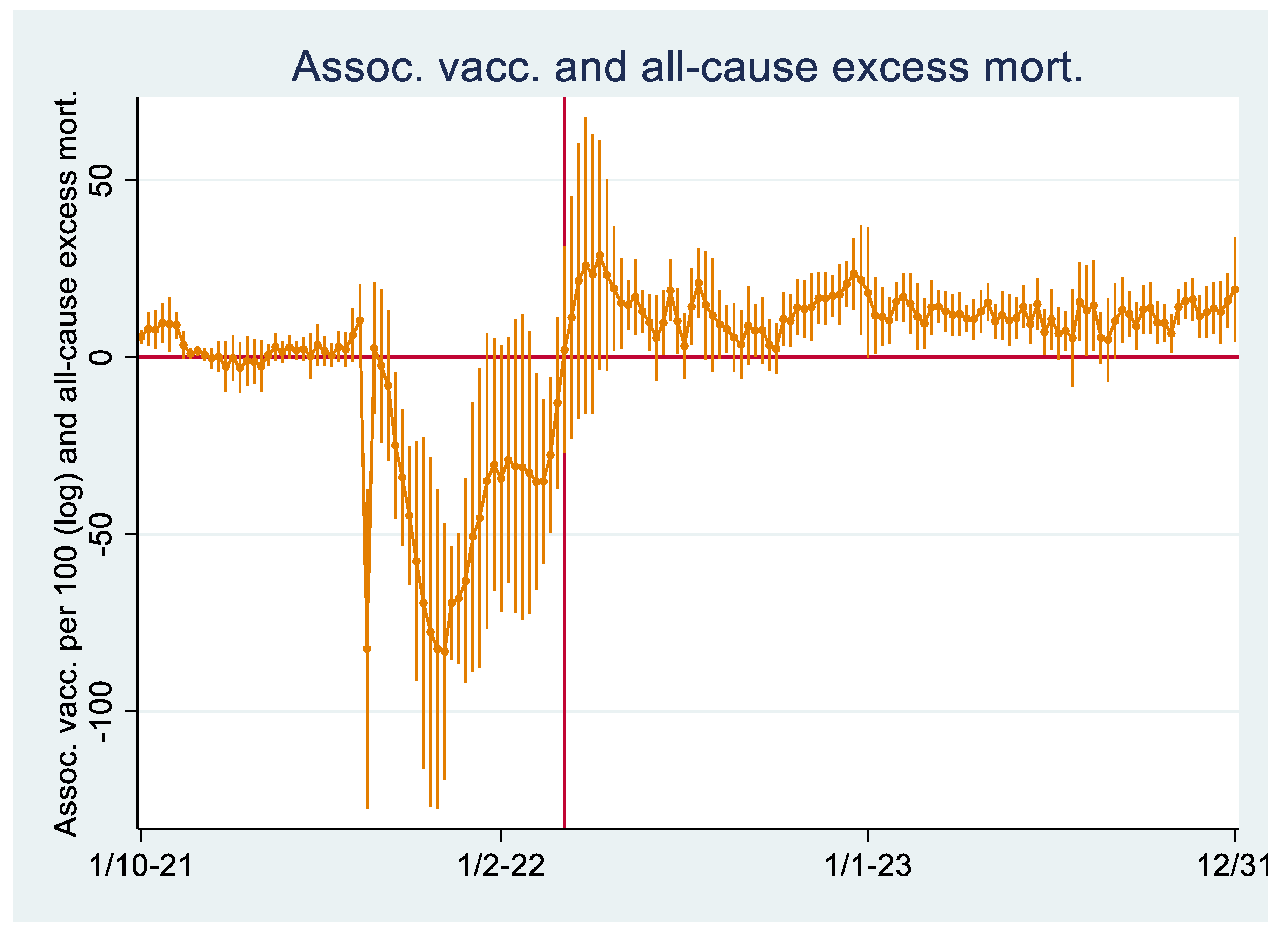

Regression Analyses I

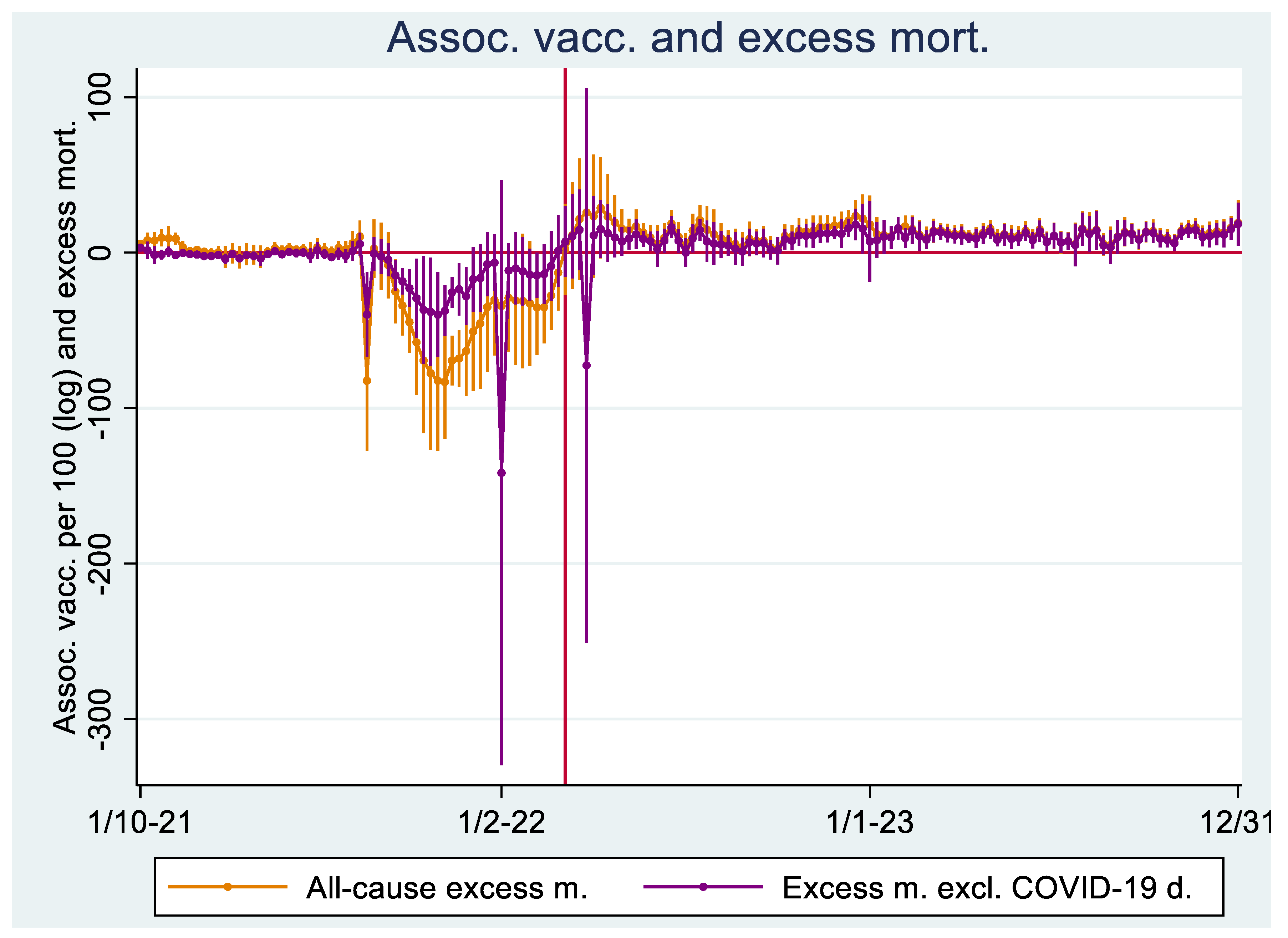

Regression Analyses II

Discussion

Limitations and Future Research

References

- Lopez-Doriga Ruiz, P.; Gunnes, N.; Michael Gran, J.; Karlstad, Ø.; Selmer, R.; Dahl, J.; et al. Short-term safety of COVID-19 mRNA vaccines with respect to all-cause mortality in the older population in Norway. Vaccine. 2023, 41, 323–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haas, E.J.; Angulo, F.J.; McLaughlin, J.M.; Anis, E.; Singer, S.R.; Khan, F.; et al. Impact and effectiveness of mRNA BNT162b2 vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 infections and COVID-19 cases, hospitalisations, and deaths following a nationwide vaccination campaign in Israel: an observational study using national surveillance data. Lancet. 2021, 397, 1819–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernal, J.L.; Andrews, N.; Gower, C.; Robertson, C.; Stowe, J.; Tessier, E.; et al. Effectiveness of the Pfizer-BioNTech and Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccines on covid-19 related symptoms, hospital admissions, and mortality in older adults in England: test negative case-control study. Bmj-British Medical Journal 2021, 373. [Google Scholar]

- Matveeva, O.; Shabalina, S.A. Comparison of vaccination and booster rates and their impact on excess mortality during the COVID-19 pandemic in European countries. Frontiers in Immunology. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordstrom, P.; Ballin, M.; Nordstrom, A. Risk of infection, hospitalisation, and death up to 9 months after a second dose of COVID-19 vaccine: a retrospective, total population cohort study in Sweden. Lancet. 2022, 399, 814–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faksova, K.; Walsh, D.; Jiang, Y.; Griffin, J.; Phillips, A.; Gentile, A.; et al. COVID-19 vaccines and adverse events of special interest: A multinational Global Vaccine Data Network (GVDN) cohort study of 99 million vaccinated individuals. Vaccine. 2024, 42, 2200–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraiman, J.; Erviti, J.; Jones, M.; Greenland, S.; Whelan, P.; Kaplan, R.M.; Doshi, P. Serious adverse events of special interest following mRNA COVID-19 vaccination in randomized trials in adults. Vaccine. 2022, 40, 5798–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, B.; Lu, P.; Monteiro, V.S.; Tabachnikova, A.; Wang, K.; Hooper, W.B.; et al. Immunological and Antigenic Signatures Associated with Chronic Illnesses after COVID-19 Vaccination. medRxiv, 2025; 2025.02.18.25322379. [Google Scholar]

- Ganan, D.; Paul, L.C.C.; Shuhei, N.; Chris Fook Sheng, N.; Nasif, H.; Akifumi, E.; Masahiro, H. Excess mortality during and after the COVID-19 emergency in Japan: a two-stage interrupted time-series design. BMJ Public Health. 2025, 3, e002357. [Google Scholar]

- Mostert, S.; Hoogland, M.; Huibers, M.; Kaspers, G. Excess mortality across countries in the Western World since the COVID-19 pandemic: 'Our World in Data' estimates of January 2020 to December 2022. BMJ Public Health. 2024, 2, e000282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasper, P.K.; Ioana, C.; Taulant, M.; John, P.A.I. COVID-19 advocacy bias in the BMJ: meta-research evaluation. BMJ Open Quality. 2025, 14, e003131. [Google Scholar]

- Our World in Data. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Vaccinations 2024 [Available from: https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations.

- Conceição, P. Human development report 2020-the next frontier: Human development and the anthropocene. United Nations Development Programme: Human Development Report. 2020.

- Arahirwa, V.; Tyrlik, K.; Abernathy, H.; Cassidy, C.; Alejo, A.; Mansour, O.; et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on delays in diagnosis and treatment of tick-borne diseases endemic to southeastern USA. Parasites & Vectors. 2023, 16, 295. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Ren, Y.; Liu, C.; Chen, X.; Li, D.; Peng, J.; et al. Global burden of mental disorders in children and adolescents before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Psychological Medicine. 2025, 55, e90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezaul Karim, K.M.; Tasnim, T. Impact of lockdown due to COVID-19 on nutrition and food security of the selected low-income households in Bangladesh. Heliyon. 2022, 8, e09368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, S.; Robinson, E.J.Z. Impact of COVID-19 on food insecurity using multiple waves of high frequency household surveys. Scientific Reports. 2022, 12, 1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Our World in Data. Data on COVID-19 (coronavirus) by Our World in Data 2024 [Available from: https://github.com/owid/covid-19-data/tree/master/public/data.

- Pizzato, M.; Gerli, A.G.; La Vecchia, C.; Alicandro, G. Impact of COVID-19 on total excess mortality and geographic disparities in Europe, 2020–, 2023: a spatio-temporal analysis. The Lancet Regional Health – Europe. 2024, 44.

- Hsieh, J.J. Encyclopedia Britannica. Ecological fallacy 2017, September 4 [Available from: https://www.britannica.com/science/ecological-fallacy.

- Wagner, C.H. Simpson's Paradox in Real Life. The American Statistician. 1982, 36, 46–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, O.J.; Barnsley, G.; Toor, J.; Hogan, A.B.; Winskill, P.; Ghani, A.C. Global impact of the first year of COVID-19 vaccination: a mathematical modelling study. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Goldin, M.; Fichera, A. Posts mislead on Pfizer COVID vaccine’s impact on transmission. Associated Press (AP) News. 2022 October 14.

- Our World in Data. Deaths, 1950 to 2023 2024 [Available from: https://ourworldindata.org/explorers/population-and-demography?indicator=Deaths&Sex=Both+sexes&Age=Total&Projection+scenario=None&country=OWID_WRL~CHN.

- Our World in Data. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Deaths 2024 [Available from: https://ourworldindata.org/covid-deaths.

- Taubenberger, J.K.; Morens, D.M. 1918 Influenza: the mother of all pandemics. Revista Biomedica. 2006, 17, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viboud, C.; Simonsen, L.; Fuentes, R.; Flores, J.; Miller, M.A.; Chowell, G. Global Mortality Impact of the 1957-1959 Influenza Pandemic. J Infect Dis. 2016, 213, 738–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarstad, J. Were the 2022 Summer Heatwaves a Strong Cause of Europe’s Excess Deaths? Climate. 2024, 12, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlinsky, A.; Kobak, D. Tracking excess mortality across countries during the COVID-19 pandemic with the World Mortality Dataset. eLife. 2021, 10, e69336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J. Interpreting regression coefficients for log-transformed variables. Cornell Statistical Consulting Unit. 2020, 83. [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. Version 17. College Station, TX StataCorp LP; 2021.

- Wyller, T.B.; Kittang, B.R.; Ranhoff, A.H.; Harg, P.; Myrstad, M. Dødsfall i sykehjem etter covid-19-vaksine. Tidsskrift for Den norske legeforening. 2021, 141, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Brien, R.M. A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors. Qual Quant. 2007, 41, 673–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manniche, V.; Schmeling, M.; Gilthorpe, J.D.; Hansen, P.R. Reports of Batch-Dependent Suspected Adverse Events of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 Vaccine: Comparison of Results from Denmark and Sweden. Medicina (Kaunas) 2024, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmeling, M.; Manniche, V.; Hansen, P.R. Batch-dependent safety of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2023, 53, e13998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothman, K.J. A pictorial representation of confounding in epidemiolog1c studies. Journal of Chronic Diseases. 1975, 28, 101–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loney, T.; Nagelkerke, N.J. The individualistic fallacy, ecological studies and instrumental variables: a causal interpretation. Emerging Themes in Epidemiology. 2014, 11, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarstad, J.; Kvitastein, O.A. Is There a Link between the 2021 COVID-19 Vaccination Uptake in Europe and 2022 Excess All-Cause Mortality? Asian Pacific Journal of Health Sciences. 2023, 10, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solsvik, T.; Adomaitis, N. Norway drops AstraZeneca vaccine, J&J remains on hold. Reuters. 2021 May 12.

| Model | A1 | A2 | A3 | B1 | B2 | B3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | -63.3*** | -97.7*** | -72.2*** | -9.64** | -66.1** | -54.9*** |

| (-89.3, -37.3) | (-152, -43.5) | (-103, -40.7) | (-15.1, -4.15) | (-106, -26.6) | (-76.7, -33.2) | |

| Vacc. (log) | 13.0*** [.739] | 11.1*** [.631] | 10.2*** [.575] | |||

| (8.10, 18.0) | (5.41, 16.9) | (5.07, 15.2) | ||||

| Vacc. | .076*** [.752] | .067*** [.666] | .059*** [.590] | |||

| (.047, .104) | (.043, .090) | (.037, .082) | ||||

| Stringency | -.025 [-.048] | -.025 [-.048] | ||||

| (-.187, .136) | (-.158, .108) | |||||

| Hum. dev. | 49.8† [.370] | 38.2** [.284] | 62.8* [.467] | 42.9*** [.319] | ||

| (-5.86, 105) | (11.0, 65.4) | (11.9, 113) | (21.1, 64.8) | |||

| Cum. excess m. | 4.66e-4 [.165] | 6.28e-4 [.222] | ||||

| (-.001, .002) | (-.001, .002) | |||||

| Median age | .174 [.159] | .170 [.155] | .225* [.205] | |||

| (-.127, .476) | (-.106, .445) | (.029, .422) | ||||

| Population (log) | -.512 [-.185] | -.604** [-.219] | -.428 [-.155] | |||

| (-1.45, .429) | (-1.04, -.171) | (-1.29, .435) | ||||

| F-value | 28.6*** | 11.0*** | 14.0*** | 28.7*** | 13.3*** | 16.6*** |

| R-sq. | .546 | .642 | .611 | .566 | .687 | .669 |

| Adj. R-sq. | .533 | .573 | .578 | .554 | .627 | .637 |

| VIF | 1 | 2.69 | 1.51 | 1 | 2.30 | 1.27 |

| N | 39 | 38 | 39 | 39 | 38 | 39 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).