1. Introduction

Pharmacogenetic testing aims to assess the genetic predisposition that could influence drug treatment. Inter-individual variability in drug response can lead to treatment issues such as the lack of efficacy or the incidence of adverse drug reactions (ADRs). These types of situations are commonly observed in clinical practice and pose significant burden to patient health and healthcare systems. It is estimated that as much as 50% of the clinical treatments are either inefficient or generate drug-related toxicity [

1]. Depending on the context, genetic polymorphisms can explain the variability in drug response in a proportion of 20-95% of cases [

2]. This is possible especially because about half of all prescriptions include drugs that could potentially be influenced by genetic variability and over 95% of the general population carries at least one mutation that is relevant to the drug treatment [

3].

Over the decades, a plethora of scientific evidences have accumulated relating genetic polymorphisms to drug treatment problems. Efforts have been made by medical testing laboratories in implementing genotyping technologies in order to move genetic analysis from the scientific laboratory, closer to the patient. In this respect, “direct-to-consumer” testing has made an even greater leap, with companies such as 23andMe, who offer FDA-approved pharmacogenetic testing and counseling worldwide. On the other side, organizations such as the Clinical Pharmacogenomics Implementation Consortium (CPIC), the Pharmacogenetics Working Group of the Royal Dutch Association for the Advancement of Pharmacy (DPWG) or the Canadian Pharmacogenomics Network for Drug Safety (CPNDS) have worked on producing and implementing treatment guidelines that could help to ”genotype-tailor” drug therapy. Thus, after a patient has benefited from genotyping, ideally as part of a preventive pharmacogenetic strategy, the results can be interpreted by a medical professional. Further, recommendations for drug therapy adjustments can be made based on the treatment guidelines available either on the websites of organizations such as CPIC, DPWG or CPNDS, or by using the database PharmGKB, that has curated such guidelines and has made them available in an easy-to-use format [

4].

In this context, the European Union has recognized the potential of personalized medicine to enhance disease prevention, diagnosis and treatment, particularly in the context of an aging population and the rising prevalence of chronic diseases [

5]. Legislative frameworks are being developed to facilitate the integration of pharmacogenetic approaches into healthcare systems, with governments aiming to standardize access to genetic testing and treatment options [

6]. However, significant disparities exist among member states concerning the implementation of personalized therapy including variations in healthcare infrastructure, reimbursement policies and public awareness. These disparities have created an uneven landscape for the accessibility of personalized medical treatments [

7]. Moreover, ethical considerations surrounding data privacy and consent, especially concerning genetic information, continue to influence the development of policies aimed at protecting patient rights in the context of personalized therapy [

8].

In Romania, the Law no. 138 of May 24, 2023, which amends Romania’s Patient Rights Law (no. 46/2003) has a significant impact on the adoption of personalized therapy and pharmacogenetics in the healthcare system. It formally recognizes the rights to individualized treatments tailored to their biological, genetic or molecular profiles of patients, thus creating a legal foundation for precision medicine. This paves the way for the use of pharmacogenetic testing to optimize drug selection and dosing, reduce adverse reactions and improve treatment outcomes. Overall, the law marks a crucial step toward integrating advanced, science-driven approaches into routine medical care, ensuring safer and more effective therapies for patients.

Synevo Laboratories is one of the leading providers of medical laboratory services in Romania, with a strong national presence and a significant impact on the country’s healthcare system. With a network of hundreds of collection centers and multiple high-capacity laboratories, Synevo offers diagnostic services across a wide range of specialties, including genetic and molecular testing.

Thus, our objective was to observe the status of pharmacogenetic testing in Romania and to offer a descriptive analysis of the results of the pharmacogenetic tests carried out between 2017 and 2023 by the Synevo laboratories.

2. Results

In total, 31.453 pharmacogenetic tests were performed in the considered time interval (2017-2023). Among the tests, FVL is the most requested (31.230 patients), surpassing significantly the other pharmacogenetic tests (CYP2D6, CYP2C9, CYP2C19 or TPMT). Age distribution of patients that underwent pharmacogenetic testing was relatively heterogenous (

Table 1). Most patients (83%) were in the 19-40 years age interval, more specifically 45% (31-40 years) and 38% (19-30 years), while the other age groups were less well represented (3% for 1-18 years, 16% for 41-50 years, 11% for over 51 years). Thus, for CYP2C19 genotyping, most patients were in the over 51 years interval (66.7%). Additionally, for CYP2D6 genotyping 66.7% of patients belonged to the 41-50 years group. For TPMT genotyping most patients were in the two extreme groups, either 1-18 years group (31.9%), or over 51 years group (23.2%). Patients that underwent CYP2C9 genotyping were mostly in the 19-30 years group (45.7%) or in the 31-40 years group (39.1%), similar to patients that underwent FVL genotyping, 33.9% and 40.2%, respectively.

The distribution among sexes is significantly uneven, with women predominating (80%). However, when looking at individual pharmacogenetic tests, proportions between sexes may differ. For CYP2C19 genotyping there were almost double the number of men, compared to women (64% versus 36%). For CYP2D6 genotyping, women predominated (94%), as it did for FVL genotyping (80%). Alternatively, for TPMT and CYP2C9 genotyping the distribution among sexes was relatively even (

Table 2).

The distribution of patients by region in Romania revealed a significantly higher proportion of tests (51%) performed on patients from the Southern region, including the capital (Bucharest). Patients in the Eastern region followed (26%), whereas significantly less pharmacogenetic tests were performed in the Center of the country (13%) and the Western region (10%). The same pattern could be observed upon analysis of each individual pharmacogenetic test (

Table 3). The northern parts of Romania were assimilated into the western and eastern, respectively,

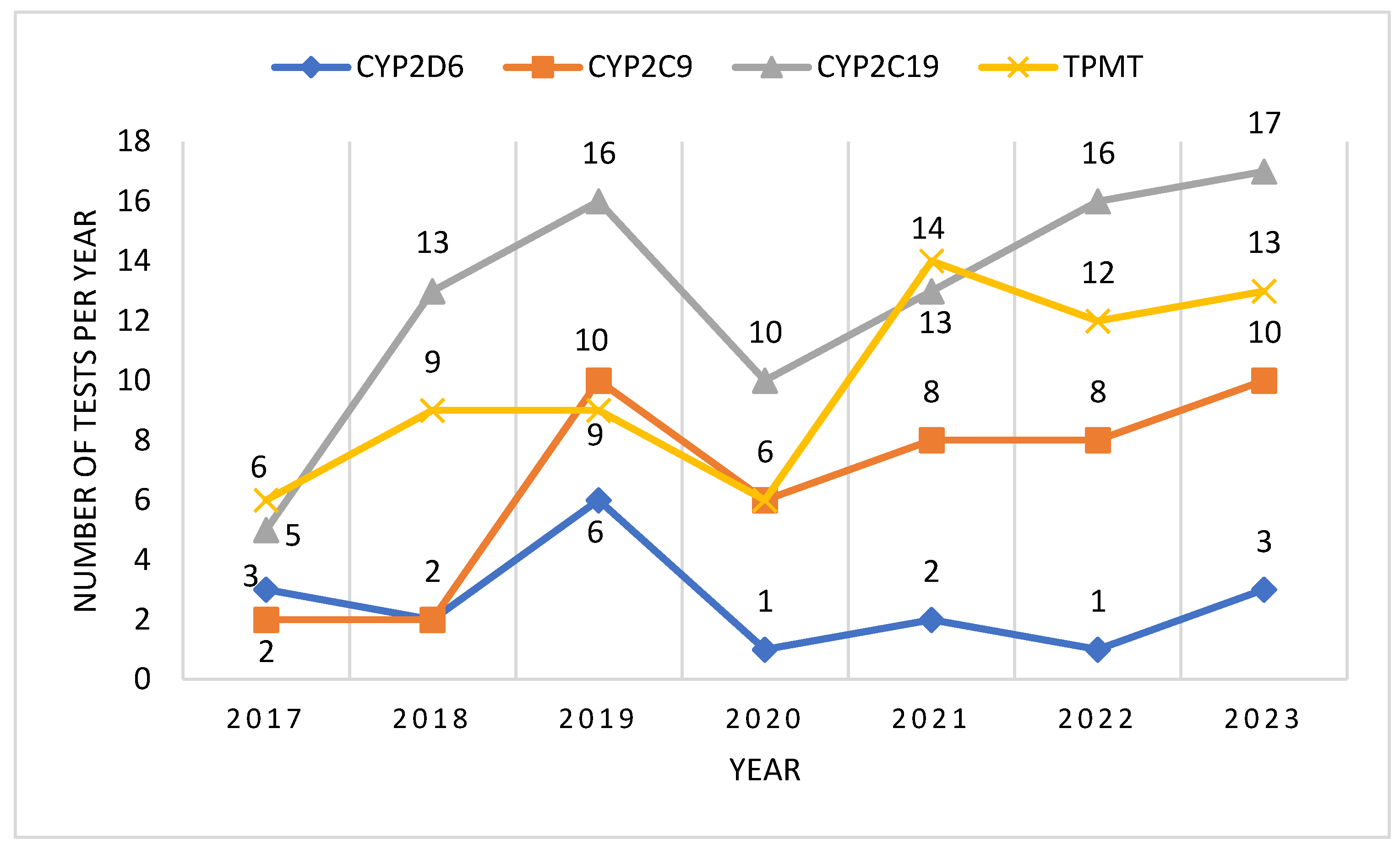

After analyzing the number of tests performed per year, we could observe an ascending trend, with a higher number of tests being performed each year, compared to the previous. In 2020 we could observe a decrease of the number of tests performed, probably due to the epidemiologic context related to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the ascending trend continued after 2020, and by 2023 it had reached and even surpassed pre-pandemic levels (

Figure 1).

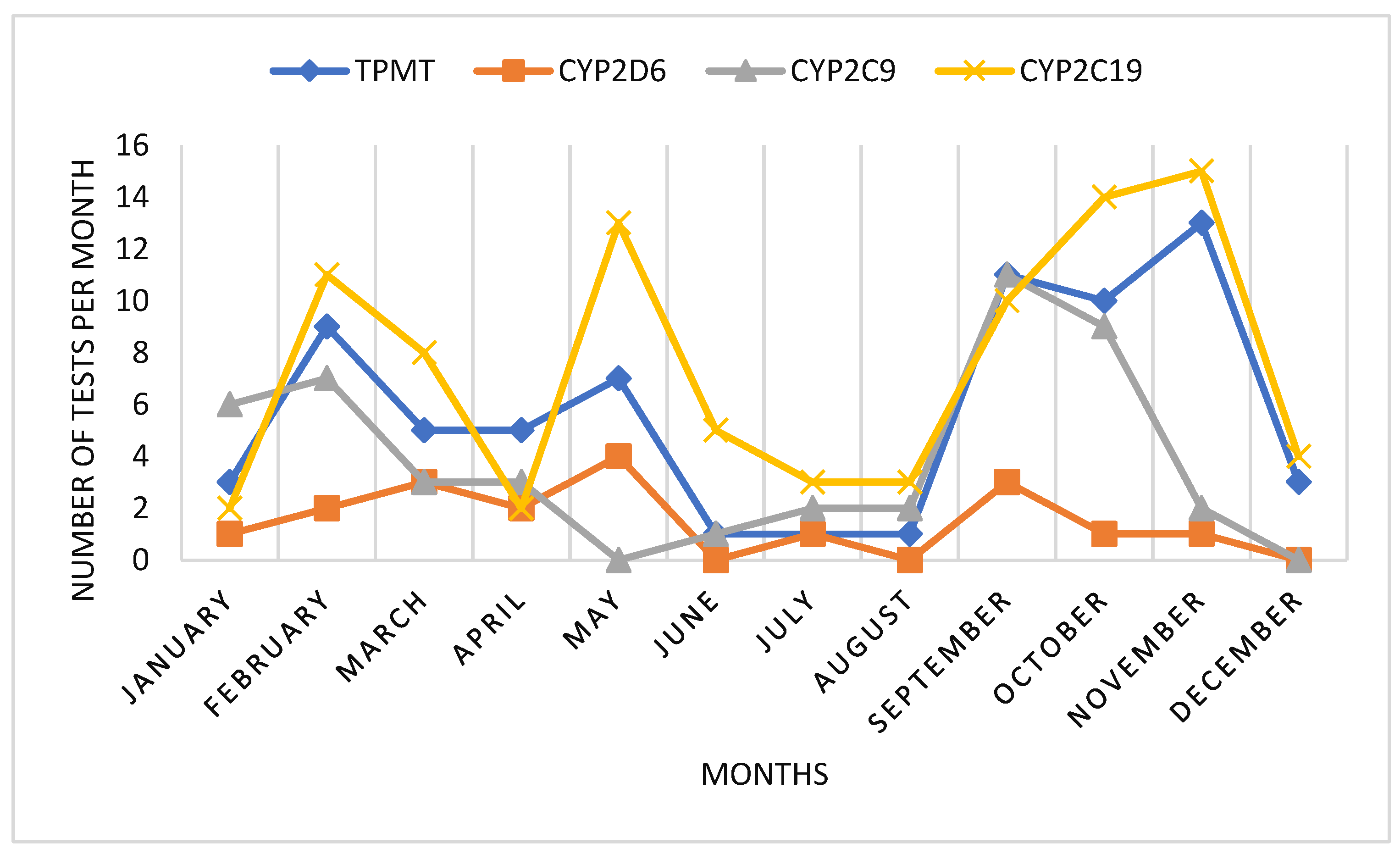

When analyzing the monthly use of pharmacogenetic tests, we could observe an interesting pattern. Mainly there were two periods of higher demand of tests, during January-May and during September-November. During summer months, pharmacogenetic testing was lower. Also in April, we could observe a decrease in pharmacogenetic testing, probably correlated to Easter holydays (

Figure 2).

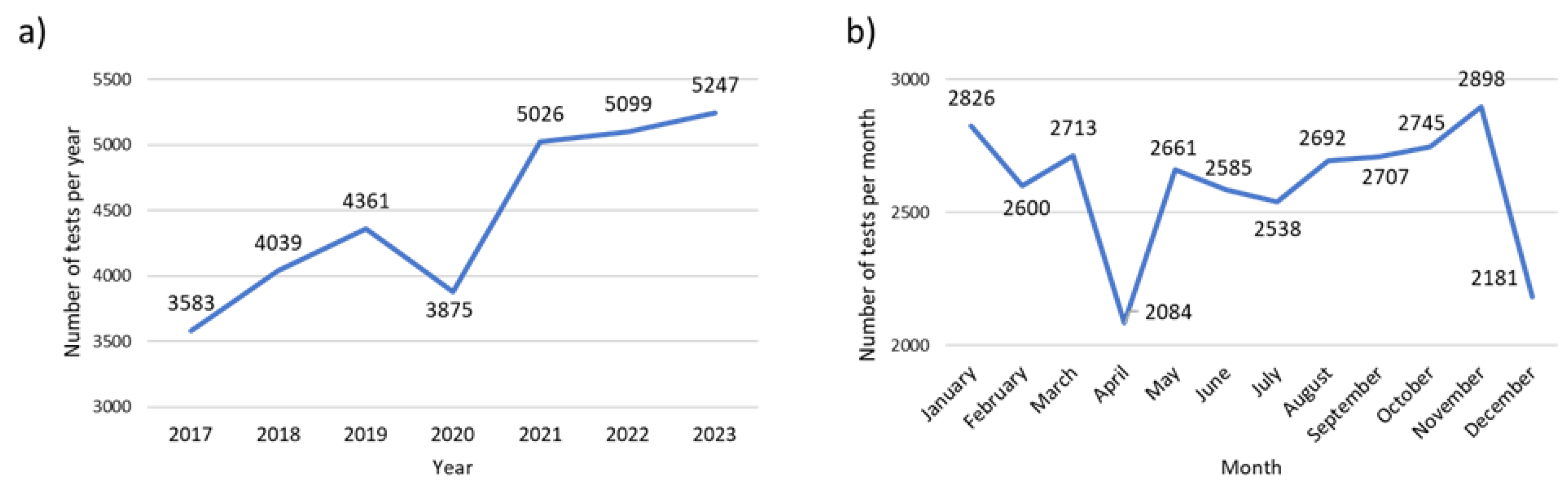

The factor V Leiden (FVL) genetic test is analyzed separately because of the significantly higher number of tests performed in comparison to the other pharmacogenetic tests (CYP2D6, CYP2C9, CYP2C19 and TPMT). For FVL genotyping we could also observe an ascending trend over time, with a significantly lower demand for this test in 2020, probably correlated to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, after the pandemic, the demand for FVL increased significantly. Thus, compared to 2017, the number of tests performed in 2023 almost doubled (

Figure 3a). Analyzing the monthly demand for FVL testing, we could observe a similar pattern compared to the other pharmacogenetic tests, more specifically, a higher demand of tests in the early months of the year and in autumn (September-November), with a drop in the summer months and in April (

Figure 3b).

Concerning the genotypes detected, for all pharmacogenetic tests, predominated the wild type gene, i.e. the normal gene variant. However, for each test, gene variants that could be of interest concerning pharmacotherapy safety or efficacy could be detected in a proportion of patients.

For phase I drug metabolizing enzymes, such as CYP isoenzymes (CYP2C9, CYP2C19 and CYP2D6), most patients could fit into the phenotype of normal (rapid) metabolizer, while phenotypes such as intermediate, slow or ultrarapid metabolizers could also be detected.

For CYP2C9, 59% of patients presented a phenotype of normal metabolizer. The rest were either intermediate metabolizers (15%) or poor metabolizers (26%) (

Table 4).

For CYP2C19, generally more genotypes could be detected compared to CYP2C9. Most patients could be categorized as normal metabolizers (48%), but also various genotypes could be detected that would lead to phenotypes such as intermediate (22%), slow (6%) or ultrarapid (24%) metabolizers (

Table 5).

Concerning CYP2D6 genotyping (

Table 6), allele coding for normal function enzymes could be identified in 40% of patients (normal metabolizers). Combinations of normal allele and mutant null allele (CYP2D6 *1/*5, CYP2D6 *1/*5), generating a phenotype of intermediate metabolizer could be identified in 39% of patients. A smaller proportion of patients could be categorized as slow metabolizer, based on a heterozygous genotype of null allele (CYP2D6 *4/*15).

The (TPMT) is a phase II drug metabolizing enzyme that methylates drugs and some endogenous substrates.

Table 7 shows that most patients undergoing TPMT genotyping presented the wild-type allele (TPMT*1). Aproximately 22% of patients presented allele associated with a phenotype of slow metabolizer (TPMT*3A and *3B).

Finally, most patients in our study underwent genotyping in order to detect the mutant variants for factor V Leiden (rs6025 mutation). As it can be observed in

Table 8, no mutation was detected in 84% of patients. Patients presenting the rs6025 mutation (16%), were either heterozygous (11%), or homozygous (5%). When analyzing two subsets of population, based on gender, we could observe a similarity in the distribution of the genetic status (normal, heterozygous mutant, homozygous mutant). Most patients in both groups presented no mutation (79% men versus 86% women), followed by heterozygous mutation (17% men versus 9% women) and lastly, a small proportion of patients presented the rs6025 mutation in homozygous form (4% men versus 5% women).

3. Discussion

Despite the growing importance of personalized medicine and the efforts made by private laboratories in offering pharmacogenetic testing in Romania, the use of this approach to personalized therapy remains relatively low, highlighting a gap between medical innovation and its practical implementation in clinical settings.

The trends of pharmacogenetic testing utilization reflect a complex interaction of seasonal health-seeking behaviors, cultural practices, and increased awareness of the importance of pharmacogenetic insights in personalized medicine. Our data show an uneven distribution of pharmacogenetic tests among sexes, which may partly stem from inherent biological differences. For example, women often experience more adverse drug reactions and have been found to exhibit different pharmacokinetic patterns for various medications, necessitating greater scrutiny through pharmacogenetic testing [

9]. In contrast, the higher prevalence of CYP2C19 testing among men may reflect gender-based differences in the types of medications prescribed or health conditions diagnosed, particularly concerning cardiovascular issues, where men are often at greater risk [

10]. Also, the predominance of women in CYP2D6 testing could possibly relate to higher instances of mood disorders in the female population and their awareness of pharmacogenetic factors affecting treatment efficacy [

11].

Sociocultural factors also play a significant role in health-seeking behavior, influencing who seeks pharmacogenetic testing. Women traditionally engage more with healthcare services and may be more proactive in seeking genetic testing for conditions such as those related to TPMT and CYP2D6, which have implications for emotional health or chronic conditions often treated with psychiatric medications [

12].

The regional disparities in the distribution of pharmacogenetic tests in Romania, with a significant portion (51%) being performed in the Southern region including the capital city, can be attributed to several intertwined factors. Firstly, Bucharest benefits from a more developed healthcare infrastructure compared to other areas. Urban centers often have greater access to specialized healthcare services, including genetic testing and personalized medicine initiatives, due to the concentration of healthcare institutions and professionals [

13]. Patients in these regions may be more likely to undergo pharmacogenetic testing as a result of increased availability of these services and greater proximity to healthcare facilities offering such tests. Secondly, public awareness and demand for pharmacogenetic testing may be higher in urban areas. Patients in big cities may be more engaged in healthcare due to better access to information and resources that promote understanding of the benefits of pharmacogenetic testing [

14]. Thirdly, the demographics of the populations in different regions also play an important role. Younger populations in urban areas may be more proactive in seeking testing, particularly in response to lifestyle-related health issues. The data suggests a higher percentage of younger patients seeking testing, likely motivated by health concerns or family histories of disease [

15]. Conversely, areas that have older populations present fewer requests for pharmacogenetic tests. Addressing these disparities is crucial for the equitable implementation of pharmacogenetics across all regions.

Regarding the evolution of pharmacogenetic testing in time, we could see an ascending trend, interrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic. While the initial decrease in pharmacogenetic testing during the COVID-19 pandemic can be explained by restricted healthcare access and patient hesitance, the subsequent recovery and rise in testing volumes are attributed to heightened awareness, healthcare system adaptation, and evolving clinical practices that prioritize personalized medicine [

16].

Concerning pharmacogenetic testing patterns within one year, the surge in testing during the first half of the year (January-May) is likely influenced by New Year's resolutions and heightened awareness of health and wellness that often accompanies the start of a new year. Individuals are more likely to engage in health checks and preventative healthcare practices immediately after the holiday season. This trend aligns with the findings from previous studies, which indicate that people often prioritize health and medical interventions at the beginning of the year [

17]. The notable decrease in the month of April, likely correlated with the Easter holidays, reflects the impact of cultural and religious observances on healthcare-seeking behavior. During significant holidays, clinics may have reduced hours or limited staffing, affecting the availability of testing services. Moreover, individuals may prioritize family gatherings and celebrations over medical appointments during these periods. Such patterns are supported by studies that examine healthcare activity fluctuations around major holidays, where patients may defer non-urgent testing in favor of festivities [

18].

In recent years, increasing awareness of pharmacogenetic testing and its implications for personalized medicine has contributed to heightened interest and demand for testing resources [

19]. Initiatives highlighting the importance of genetic testing in optimizing drug therapies may play a role, especially in the months following public health campaigns that promote awareness and education. This growing knowledge encourages patients to seek pharmacogenetic testing more actively during periods when they engage with healthcare professionals.

We included in our analysis pharmacogenetic testing offered by the Synevo laboratories. They include mostly tests involving genes coding for drug metabolizing enzymes (CYP2C9, CY2C19, CYP2D6, TPMT) and Factor V Leiden. We evaluated the trends in the utilization of these pharmacogenetic tests as well as results, trying to extrapolate and integrate the information in the context of the population.

CYP2C9 Pharmacogenetic Testing

CYP2C9 is part of the CYP450 superfamily and it is the most abundant CYP2C isoform expressed by the liver, comprising approximately 20% of the total hepatic content. CYP2C9 is also involved in the metabolization of approximately 15% of all clinically used drugs [

20]. In addition, because the CYP2C9 gene is highly polymorphic, it is one of the key pharmacogenes involved in the implementation of personalized medicine. Currently, PharmVar has listed a total of 85 star-allele (CYP2C9*1-*85) out of which 2 allele (*1 and *9) code for enzymes with normal function, 21 generate enzymes with decreased function, 13 generate enzymes with no function and for the rest, function is either uncertain or still being studied.

Based on CYP2C9 diplotype (allele present on each of the two identical chromosomes), patients can be classified based on CYP2C9 phenotype. Individuals are categorized into the following CPIC–recommended phenotype categories: poor (PM), intermediate (IM) and normal (NM) metabolizers. The genotype to phenotype translation is made by using the Activity Score (AS), first used for the CYP2D6 gene [

21]. In short, every allele is assigned a score and the sum of the individual scores for each allele is used to categorize the patient to the specific phenotype category. By using the AS system, a patient can be assigned to a specific phenotype category and then receive tailored prescribing guidance. Of the 206 drugs with clinical guideline annotations from PharmGKB database, 27 drugs have annotations involving the CYP2C9 pharmacogene. Clinical annotations concerning drugs influenced by CYP2C9 polymorphism have been issued by CPIC (n=19) or by DPWG (n=9). These drugs include oral anticoagulants (acenocoumarol, phenprocoumon and warfarin), anticonvulsants (phenytoin, fosphenytoin), multiple NSAIDs (e.g., celecoxib, flurbiprofen, lornoxicam, ibuprofen, piroxicam, tenoxicam, and meloxicam), losartan, irbesartan, sulfonylureas (tolbutamide, glimepiride and gliclazide) and siponimod.

In our study, we have found a higher frequency of CYP2C9*2 and CYP2C9*3 alleles (41% of patients), as compared to other studies [

22], because we did not sample the general population, but our sample included patients that had an indication for pharmacogenetic testing based on a presumption that they may be positive for actionable pharmacogenes. Thus, it would be expected that these patients present with a higher frequency of alleles that possibly modify pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of drugs. From the functionally relevant CYP2C9 alleles, *2 and *3 were most abundant in Europe and the Middle East. Additionally, CYP2C9*3 was also common in South Asia but also in some countries in South America such as Uruguay, Columbia and Brazil [

22]. In vitro, CYP2C9*2 reduces enzyme activity by 50–70% whereas CYP2C9*3 almost completely abrogates enzyme function (reduction of 75–99%) [

22].

In our population, around 15% of the patients presented with a phenotype of intermediate metabolizer (CYP2C9*1/*2) and 26% were poor metabolizers (CYP2C9*2/*3). This translation of genetic variability into functional phenotypes can reveal that a great proportion of patients, around 40%, can benefit from therapy adjustment for drugs metabolized by CYP2C9, most specifically for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index.

Due to the significant impact of CYP2C9 variations, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) include CYP2C9 genotyping in the drug labels or summary of product characteristics of 19 drugs. Specifically, testing is required for the sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor modulator siponimod in multiple sclerosis and CYP2C9 genotype is also considered as actionable information for dosage of warfarin, phenytoin and several non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) [

22].

The most common clinical application of CYP2C9 genotype in formation described to date is its use, together with VKORC1 and possibly CYP4F2, to guide warfarin dosing. Individuals with one or two decreased or no function alleles have decreased metabolism of the more potent S- enantiomer of warfarin and increased risk of bleeding with usual warfarin doses (i.e., 5 mg per day), and thus, a lower warfarin dose is required to achieve therapeutic anticoagulation. Three multisite clinical trials have examined the efficacy of CYP2C9 plus VKORC1 genotype- guided warfarin, of which two trials demonstrated favorable effects of a genotype-guided approach on the outcome of improved anticoagulation control or reduction in risk for bleeding, thromboembolism, death, or supratherapeutic anticoagulation following total joint arthroplasty.

CYP2C9 decreased and no function alleles similarly lead to increased exposure to other CYP2C9 substrates, which may increase the risk for serious adverse effects, including neurotoxicity with phenytoin, gastrointestinal bleeding, and adverse cardiovascular effects with NSAIDs, and bradycardia with siponimod. Siponimod is contraindicated for poor metabolizers (PMs) with the CYP2C9*3/*3 genotype, who are expected to have little to no enzyme activity. Thus, genotyping is required prior to siponimod initiation. Lower phenytoin maintenance doses are recommended for patients with genotypes associated with significant reductions in enzyme activity. For NSAIDs, the consequences of decreased CYP2C9-mediated metabolism are expected to be greatest for drugs with a long elimination half- life (e.g., piroxicam, tenoxicam, and melocoxicam) and less significant for NSAIDs with shorter half- lives (e.g., celecoxib and ibuprofen). This is reflected by CPIC guidelines recommending that in PMs (e.g., CYP2C9*2/*3 or *3/*3 genotypes), piroxicam, tenoxicam, and meloxicam be avoided, whereas celecoxib and ibuprofen may be used but should be started at lower than usual doses.

Sex-related differences in CYP2C9 expression have been investigated to a limited extent, and to date there is no evidence supporting meaningful differences between males and females.

One study found slower metabolism of losartan in females compared with males [

23]. However, considering that estrogens upregulate CYP2C9 expression via the estrogen receptor, studies on sex differences should consider this possible confounder [

24]. Also, it seems that age could influence CYP2C9 expression, with CYP2C9 levels lower in children and increasing linearly up to 20 years [

25]. Findings for the effect of age on CYP2C9 contrast with CYP2C19 where levels appear to be higher in children than in adults.

CYP2C19 Pharmacogenetic Testing

CYP2C19 plays an important role in the metabolism of approximately 10% of commonly prescribed medications, including proton pump inhibitors like omeprazole, antidepressants such as amitriptyline or sertraline, and the antiplatelet agent clopidogrel [

26]. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has included CYP2C19 genotyping information in the drug labels of 28 medicines, recognizing the significance of CYP2C19 genetic variability in drug metabolism and therapeutic efficacy. Genetic polymorphisms in the CYP2C19 gene categorize individuals into distinct metabolic phenotypes: normal, ultrarapid, intermediate, and poor metabolizers. Currently, PharmVar has listed a total of 39 star-allele (CYP2C19*1-*39) out of which 7 allele code for enzymes with normal function, 6 generate enzymes with decreased function, 12 generate enzymes with no function, one allele codes for CYP2C19 with increased function (*17) and for the rest, function is either uncertain or still being studied.

Our results show that for CYP2C19, generally more genotypes could be detected compared to CYP2C9. CYP2C19 is known to exhibit a higher degree of polymorphism compared to CYP2C9, which may be linked to evolutionary pressures and the historical genetic landscape of various populations, including Romanians. This higher variability allows for a broader range of metabolizer phenotypes, making CYP2C19 particularly relevant in clinical contexts, especially concerning drug metabolism and patient response to medications [

27].

Also, the clinical implications associated with CYP2C19 polymorphisms, particularly regarding drugs such as clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), likely increase the testing rates among healthcare practitioners aware of its relevance in treatment efficacy and safety. This is evidenced in guidelines that recommend genotype testing to optimize therapy with these medications, especially in populations where such medications are frequently prescribed [

28].

In our study, most patients who were tested for CYP2C19 variability were over 51 years old, thus most likely under chronic treatment with drugs possibly influenced by CYP2C19 metabolism. Older adults are indeed more likely to take multiple medications, a phenomenon known as polypharmacy. For instance, one study indicated that approximately 26.3% of older adults in Taiwan were prescribed five to nine medications daily, while 15% used ten or more drugs [

29]. In older populations, where polypharmacy is prevalent due to multiple comorbidities, the implications of CYP2C19 variability become even more critical. Poor metabolizers may experience increased drug concentrations and adverse effects when prescribed medications that rely on CYP2C19 for metabolism, such as clopidogrel [

30]. Studies indicate that genetic polymorphisms in CYP2C19 not only influence treatment efficacy but also increase the likelihood of hospitalizations among patients experiencing adverse drug events due to polypharmacy [

31].

The prevalence of CYP2C19*17 haplotype associated with ultrarapid metabolism of CYP2C19 across the evaluated population has important implications. A growing body of research suggests that the distribution and frequency of alleles, including CYP2C19*17, may be influenced by factors such as demographic history, ethnicity, and geographic region [

32]. In Romania, the prevalence of CYP2C19 ultrarapid metabolizers can be explained by genetic drift, population admixture, and historical migrations that have shaped the genetic landscape of the region, positioning it similarly to various Eastern and Central European populations in terms of genetic diversity and overall ancestry. Various studies have indicated that populations from Eastern Europe, including Romania, exhibit a wide range of CYP2C19 genetic variability, encompassing both normal and ultrarapid metabolizer phenotypes [

32]. The high prevalence of the *17 allele may influence drug responses and treatment outcomes for medications metabolized by CYP2C19, such as clopidogrel and certain antidepressants, leading to differential therapeutic effectiveness and risks of adverse drug reactions when compared to other populations with lower frequencies of this variant [

32]. Additionally, clinical guidelines suggest that understanding the frequencies of these haplotypes will aid in the implementation of personalized medicine practices in different countries, including Romania, optimizing drug prescriptions based on genetic testing results [

32]. As healthcare systems increasingly adopt pharmacogenetic approaches, the high prevalence of ultrarapid metabolizers in the Romanian population highlights the urgency for tailored drug therapies that consider these genetic differences. This proactive approach could streamline treatment protocols, mitigating the risks of therapeutic failure and enhancing overall patient outcomes [

33]. Moreover, the implementation of clinical decision support systems that incorporate CYP2C19 genotype data could facilitate genotype-guided prescribing, benefiting individuals identified as ultrarapid metabolizers [

34]. Such measures would lead to a more effective healthcare model that aligns pharmacotherapy with individual genetic profiles, particularly as Romania continues to develop its public health strategies around pharmacogenomics [

35].

CYP2D6 Pharmacogenetic Testing

CYP2D6 plays a critical role in drug metabolism, being responsible for the biotransformation of approximately 20-25% of clinically used medications, including antidepressants, antipsychotics, and opioids [

36].

The FDA has included CYP2D6 genotyping information in the drug labels of approximately 78 medicines, recognizing the significance of CYP2D6 genetic variability in drug metabolism and therapeutic efficacy. Additionally, the CPIC has provided guidelines for 26 drugs where CYP2D6 genetic variations are actionable.

Genetic polymorphisms in the CYP2D6 gene categorize individuals into distinct metabolic phenotypes: normal, ultrarapid, intermediate, and poor metabolizers. Currently, PharmVar has listed a total of 177 star-allele (CYP2D6*1-*177) and an impressive number of suballeles. Around 11 allele code for enzymes with normal function, 17 generate enzymes with decreased function, 41 generate enzymes with no function, and for the rest, function is either uncertain or still being studied. There is no identified allele to code for CYP2D6 with increased function.

The concentrations of CYP2D6 tests in the 41-50 age cohort may reflect a combination of ongoing treatment adjustments and monitoring for mental health disorders, where pharmacogenetic factors become particularly critical in personalized medicine approaches [

37].

The findings from the CYP2D6 genotyping study, which revealed that 40% of patients were normal metabolizers, 39% were intermediate metabolizers, and a smaller proportion were classified as slow metabolizers, align with data reported in studies indicating similar allele distributions across various populations. For instance, the prevalence of normal metabolizers typically falls within this range in studies conducted in European cohorts, suggesting that the Romanian population exhibits alleles consistent with a broader ethnic background [

38]. The significant percentage of individuals categorized as intermediate metabolizers (39%) is noteworthy and reflects the prevalence observed in populations characterized by diverse genetic backgrounds. For example, studies have documented comparable intermediate metabolizer rates in Middle Eastern and African populations, indicating a potential genetic diversity contributing to these findings [

39,

40]. The emergence of slow metabolizers, identified in 6% of patients with a heterozygous genotype (CYP2D6 4/15) in this study, is within the range reported in the literature, though some sources highlight varying rates across different ethnic groups [

41,

42]. Analyzing these findings in the context of Romanian patients suggests a complex interplay of genetic factors that may align with historical migration patterns and regional population genetics. The high variability in CYP2D6 alleles can be attributed to population admixture, where distinct genetic backgrounds may yield a diverse array of phenotypes, impacting drug metabolism and therapeutic response [

43,

44].

Thiopurine S-methyltransferase (TPMT) Pharmacogenetic Testing

TPMT is an important enzyme involved in the metabolism of thiopurine drugs, including azathioprine and mercaptopurine, which are commonly used in the treatment of various conditions such as leukemia and autoimmune diseases, more specifically mercaptopurine, thioguanine, azathioprine and cisplatin. TPMT catalyzes the S-methylation of thiopurine compounds, playing a significant role in detoxifying these drugs to mitigate their potential toxic effects on patients [

45]. The genetic polymorphism of the TPMT gene has significant implications for drug metabolism, as variations in TPMT activity can lead to different responses to thiopurine therapy. Up to 10% of the population may carry variants associated with reduced enzymatic activity, increasing the risk of severe myelosuppression when exposed to standard drug doses [

46]. Notably, more than 20 alleles affecting TPMT function have been identified, highlighting the degree of genetic variability and its importance in tailoring pharmacotherapy [

47].

The results indicating that 88% of patients undergoing TPMT genotyping presented the wild-type allele (TPMT*1) are consistent with findings in various populations, highlighting the prevalence of this allele among different ethnic groups. For instance, a study by Ladić et al. reported a similar predominance of the TPMT*1 allele in Croatian patients with inflammatory bowel disease while also noting *3A as a more common pathological variant allele in that population [

48]. This comparison emphasizes the genetic variability of TPMT variants, as research has demonstrated that while mutant alleles (such as TPMT*3A and *3B) exist, their frequency and implications for drug metabolism can differ across populations.

Further studies have found that the distribution of TPMT polymorphisms varies regionally; for example, Almoguera et al. indicated that in Asian populations, *3C is often the most prevalent variant, whereas *3A is more common in Caucasian populations [

49]. Additionally, the identification of *3A and *3B alleles in patients categorized as slow metabolizers underscores the clinical importance of understanding these genetic variations, as individuals with these alleles may experience heightened risks of adverse reactions to thiopurine medications due to diminished metabolic capacity [

50]. In populations like the Iraqi cohort studied by Kadhum et al., the presence of TPMT variants is associated with significant implications for treatment efficacy and safety, supporting the recommendation that pharmacogenetic testing should be standard practice to reduce adverse drug reactions and optimize dosing among this diverse population [

51].

Factor V Leiden (FVL) Pharmacogenetic Testing

FVL is a well-recognized hereditary thrombophilia risk factor caused by a mutation in the factor V gene leading to resistance to activated protein C (APC), which normally functions to inhibit coagulation pathways. The presence of this mutation significantly elevates the risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE), making it a critical consideration in pharmacotherapy, especially in the prescribing of anticoagulant therapies [

52]. FVL testing is advised when confirmation of the diagnosis is required in the case of categories of patients with low or borderline APC resistance results, positive lupus coagulant, extended activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), VTE associated with pregnancy, postpartum or the use of combined oral contraceptive, medications that might affect APC resistance results, VTE onset at age 40 or younger, which can be spontaneous, linked to environmental factors or with cases in the family of venous thromboses in at least one first degree relative [

52].

The prevalence of the FVL mutation varies by population, being found in about 5% of Caucasians, while it occurs less frequently in African Americans, approximately 1% [

53]. Understanding the genetic predisposition to thrombophilia, particularly FVL, is vital for tailoring anticoagulant treatment plans, especially in populations at higher risk, as inadequate management can lead to severe complications such as thrombosis during surgeries, pregnancy or in patients with certain conditions. Consequently, integrating personalized medicine approaches through genetic profiling enhances patient safety and outcomes by informing clinical decision-making tailored to individual genetic risks, emphasizing the importance of pharmacogenetic testing in diverse population settings [

54].

Our findings indicate that 16% of patients presented the FVL mutation (rs6025), with 11% being heterozygous and 5% homozygous. In Caucasian populations, the frequency of the FVL mutation typically ranges from 5% to about 10%, particularly among those at risk for venous thromboembolism (VTE) [

55]. Notably, some regions within Europe have reported frequencies as high as 10-15% in the general population [

55]. In several European studies, researchers highlighted the FVL mutation as a primary genetic risk factor for thrombosis, reinforcing the clinical necessity for screening in high-risk populations [

53]. In contrast, the results from the current analysis suggest a slightly higher incidence of the FVL mutation compared to some studies focusing on specific cancer or thrombosis cases. The observed 16% mutation rate indicates that while the Romanian cohort aligns with global data suggesting that FVL is a significant risk factor for thrombosis, population-specific genetic characteristics or environmental factors may also influence these results. However, the fact that the evaluated population is not the general population, but patients for whom doctors have had suspicions of thrombosis risk factors, it could explain the slightly higher prevalence of the problematic FVL mutation.

When examining the distribution of FVL among genders, the findings indicate a similar prevalence of the mutation across male and female patients. This observation is consistent with studies suggesting no substantial gender-based differences in the presence of this polymorphism. However, the slight variations in the presence of heterozygous and homozygous mutations reported here underscore the need for localized studies that consider demographic contexts when evaluating genetic risk factors for thrombosis [

56].

Moreover, the age distribution observed reflects the prevalence of certain conditions and the health-seeking behavior of different demographics. The predominance of younger adults undergoing FVL testing may indicate greater awareness of thrombosis-related risks, possibly influenced by family histories or personal medical backgrounds, which motivates testing early [

57]. Additionally, the high use of testing by women at fertile age (31-40 yo) could suggest that the test has been recommended by doctors in the context of pregnacy related thrombosis risk evaluation. In the case of pregnant women who are heterozygous for the Factor V Leiden variant, they have a five- to eight-fold increased risk of developing venous thromboembolism as opposed to pregnant women who do not carry the variant. Nevertheless, without other predisposing factors, the risk remains low. On the other side, at the fertile age use of contraceptives is also increased. Estrogen-containing contraceptives and hormone replacement therapy should be avoided in both women who are heterozygous for the factor V Leiden mutation, with a personal history of VTE, and homozygous carriers irrespective of the VTE history.

In recent years, the global demand for pharmacogenetic testing has grown significantly, driven by advances in personalized medicine and increasing evidence of its clinical utility. However, in Romania, the adoption of pharmacogenetic testing, although on an increasing trend, remains relatively limited. Even if the cost of testing has decreased considerably, making it more accessible to patients, the prescribing rates have not increased at the same pace. A key barrier could be the limited awareness among Romanian healthcare providers about the benefits of pharmacogenetic information in optimizing drug therapy, despite their increased interest in these tests [

58]. To bridge this gap, targeted educational initiatives are needed to inform prescribers about how pharmacogenetic testing can improve treatment efficacy, reduce adverse drug reactions, and contribute to more individualized patient care.

4. Materials and Methods

The present retrospective study utilized the database of Synevo laboratories, from which data were sourced based on a scientific collaboration agreement that ensured confidentiality and limited use to strictly scientific purposes. Data concerning pharmacogenetic testing between 2017 and 2023 within the Synevo laboratories were extracted from the database. The analysis focused on the genotyping of key pharmacogenetic markers, specifically CYP2D6, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, TPMT (thiopurine S-methyltransferase), and factor V Leiden. For each pharmacogenetic test, we collected comprehensive demographic data of the patients as well as the results of the genotyping analyses. These data were subsequently subjected to statistical analysis using IBM SPSS Statistics (IBM Corp., 2023), in order to describe the prevalence and distribution of different alleles and phenotypes within the studied population. The analysis employed appropriate statistical methods to assess the significance between genotypes and demographic variables, following standard protocols in pharmacogenetic research. The findings were compared to other studies in order to understanding the genetic landscape of Romanian patients in relation to drug metabolism and therapy personalization.

5. Conclusions

Between 2017 and 2023, pharmacogenetic testing in Romania experienced a rise in demand, performing over 31,000 tests, with factor V Leiden (FVL) as the clear leader. The majority of patients were women and adults aged 19 to 40, though each test showed unique demographic patterns: for instance, CYP2C19 testing was more frequent in older adults, while TPMT testing was notably common among children and seniors. Testing rates followed a steady upward trend, briefly interrupted in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, but quickly recovered, surpassing pre-pandemic levels. Seasonal patterns were evident, with peaks in spring and autumn, and lower activity during summer and around Easter. Genetic analysis revealed that while most patients carried the normal gene variants, a significant number harbored mutations relevant to drug metabolism, especially for CYP enzymes. These insights reflect a growing awareness and adoption of pharmacogenetic testing in Romania, paving the way toward safer, more personalized treatments.

As pharmacogenetics aims to optimize therapeutic efficacy and minimize adverse drug reactions, it empowers patients to receive the most appropriate medications based on their unique genetic makeup. Pharmacogenetic tests can provide useful information to clinicians in order to personalize pharmacotherapy. However, despite the fact that interest of Romanian medical professionals in these tests is increased [

58], there are currently several impediments to the prescription and routine clinical implementation of pharmacogenetic testing.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.P., A.C. and C.M.; methodology, C.P.; software, A.C.; validation, C.P., A.C. and C.M.; formal analysis, C.P.; investigation, A.C.; resources, O.V., A.A., A.C.; data curation, A.M., A.S., H.S.; writing—original draft preparation, C.P., A.S., S.L.P.; writing—review and editing, C.P., A.C. and C.M.; visualization, F.R.D.; supervision, C.M.; project administration, C.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

“The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki”

Informed Consent Statement

“Not applicable.”

Acknowledgments

”The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.”

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”

References

- Dunnenberger HM, Crews KR, Hoffman JM, Caudle KE, Broeckel U, Howard SC, et al. Preemptive Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation: Current Programs in Five US Medical Centers. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2015 Jan 6;55(1):89–106. [CrossRef]

- Cacabelos R, Naidoo V, Corzo L, Cacabelos N, Carril JC. Genophenotypic Factors and Pharmacogenomics in Adverse Drug Reactions. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Dec 10;22(24):13302. [CrossRef]

- Pirmohamed M. Pharmacogenomics: current status and future perspectives. Nat Rev Genet. 2023 Jun 27;24(6):350–62. [CrossRef]

- Barbarino JM, Whirl-Carrillo M, Altman RB, Klein TE. PharmGKB: A worldwide resource for pharmacogenomic information. WIREs Systems Biology and Medicine. 2018 Jul 23;10(4). [CrossRef]

- Nimmesgern E, Norstedt I, Draghia-Akli R. Enabling Personalized Medicine in Europe by the European Commission’s Funding Activities. Per Med. 2017 Jul 23;14(4):355–65. [CrossRef]

- Horgan D, Spanic T, Apostolidis K, Curigliano G, Chorostowska-Wynimko J, Dauben HP, et al. Towards Better Pharmaceutical Provision in Europe—Who Decides the Future? Healthcare. 2022 Aug 22;10(8):1594.

- Allen N, Liberti L, Walker SR, Salek S. A Comparison of Reimbursement Recommendations by European HTA Agencies: Is There Opportunity for Further Alignment? Front Pharmacol. 2017 Jun 30;8.

- Horgan D, Ciliberto G, Conte P, Baldwin D, Seijo L, Montuenga LM, et al. Bringing Greater Accuracy to Europe’s Healthcare Systems: The Unexploited Potential of Biomarker Testing in Oncology. Biomed Hub. 2020 Sep 14;5(3):1–42. [CrossRef]

- Shaaban S, Ji Y. Pharmacogenomics and health disparities, are we helping? Front Genet. 2023 Jan 23;14.

- Relling M V., Schwab M, Whirl-Carrillo M, Suarez-Kurtz G, Pui C, Stein CM, et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium Guideline for Thiopurine Dosing Based on <scp>TPMT</scp> and <scp>NUDT</scp> 15 Genotypes: 2018 Update. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2019 May 20;105(5):1095–105.

- Theken KN, Lee CR, Gong L, Caudle KE, Formea CM, Gaedigk A, et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium Guideline (CPIC) for CYP2C9 and Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2020 Aug 28;108(2):191–200. [CrossRef]

- Theken KN, Lee CR, Gong L, Caudle KE, Formea CM, Gaedigk A, et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium Guideline (CPIC) for CYP2C9 and Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2020 Aug 28;108(2):191–200. [CrossRef]

- Gawronski BE, Cicali EJ, McDonough CW, Cottler LB, Duarte JD. Exploring perceptions, knowledge, and attitudes regarding pharmacogenetic testing in the medically underserved. Front Genet. 2023 Jan 13;13. [CrossRef]

- Dawes M, Esquivel B. Pharmacogenetics Implementation in Primary Care. Med Res Arch. 2022;10(8).

- Lu M, Lewis CM, Traylor M. Pharmacogenetic testing through the direct-to-consumer genetic testing company 23andMe. BMC Med Genomics. 2017 Dec 19;10(1):47. [CrossRef]

- Dawes M, Esquivel B. Pharmacogenetics Implementation in Primary Care. Med Res Arch. 2022;10(8).

- Elliott LS, Henderson JC, Neradilek MB, Moyer NA, Ashcraft KC, Thirumaran RK. Clinical impact of pharmacogenetic profiling with a clinical decision support tool in polypharmacy home health patients: A prospective pilot randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2017 Feb 2;12(2):e0170905. [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Qi G, Han C, Zhou Y, Yang Y, Wang X, et al. The Landscape of Clinical Implementation of Pharmacogenetic Testing in Central China: A Single-Center Study. Pharmgenomics Pers Med. 2021 Dec;Volume 14:1619–28. [CrossRef]

- Jmel H, Boukhalfa W, Gouiza I, Seghaier RO, Dallali H, Kefi R. Pharmacogenetic landscape of pain management variants among Mediterranean populations. Front Pharmacol. 2024 May 15;15. [CrossRef]

- Sangkuhl K, Claudio-Campos K, Cavallari LH, Agundez JAG, Whirl-Carrillo M, Duconge J, et al. PharmVar GeneFocus: CYP2C9. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2021 Sep 12;110(3):662–76.

- Caudle KE, Sangkuhl K, Whirl-Carrillo M, Swen JJ, Haidar CE, Klein TE, et al. Standardizing <scp>CYP</scp> 2D6 Genotype to Phenotype Translation: Consensus Recommendations from the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium and Dutch Pharmacogenetics Working Group. Clin Transl Sci. 2020 Jan 24;13(1):116–24.

- Zhou Y, Nevosadová L, Eliasson E, Lauschke VM. Global distribution of functionally important CYP2C9 alleles and their inferred metabolic consequences. Hum Genomics. 2023 Feb 28;17(1):15. [CrossRef]

- Park YA, Song Y bin, Yee J, Yoon HY, Gwak HS. Influence of CYP2C9 Genetic Polymorphisms on the Pharmacokinetics of Losartan and Its Active Metabolite E-3174: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Pers Med. 2021 Jun 29;11(7):617. [CrossRef]

- Mwinyi J, Cavaco I, Yurdakok B, Mkrtchian S, Ingelman-Sundberg M. The Ligands of Estrogen Receptor α Regulate Cytochrome P4502C9 (CYP2C9) Expression. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011 Jul;338(1):302–9. [CrossRef]

- Magliocco G, Rodieux F, Desmeules J, Samer CF, Daali Y. Toward precision medicine in pediatric population using cytochrome P450 phenotyping approaches and physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling. Pediatr Res. 2020 Feb 10;87(3):441–9. [CrossRef]

- Dorji PW, Tshering G, Na-Bangchang K. CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP2D6 and CYP3A5 polymorphisms in South-East and East Asian populations: A systematic review. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2019 Apr 13;jcpt.12835.

- Lima JJ, Thomas CD, Barbarino J, Desta Z, Van Driest SL, El Rouby N, et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) Guideline for CYP2C19 and Proton Pump Inhibitor Dosing. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2021 Jun 20;109(6):1417–23. [CrossRef]

- Lee CR, Luzum JA, Sangkuhl K, Gammal RS, Sabatine MS, Stein CM, et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium Guideline for CYP2C19 Genotype and Clopidogrel Therapy: 2022 Update. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2022 Nov 8;112(5):959–67. [CrossRef]

- Lai SW, Liao KF, Lin CL, Lin CC, Lin CH. Longitudinal data of multimorbidity and polypharmacy in older adults in Taiwan from 2000 to 2013. Biomedicine (Taipei). 2020 Jun 24;10(2).

- Díaz-Ordóñez L, Ramírez-Montaño D, Candelo E, González-Restrepo C, Silva-Peña S, Rojas CA, et al. Evaluation of CYP2C19 Gene Polymorphisms in Patients with Acid Peptic Disorders Treated with Esomeprazole. Pharmgenomics Pers Med. 2021 Apr;Volume 14:509–20. [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein J, Friedman C, Hripcsak G, Cabrera M. Pharmacogenetic polymorphism as an independent risk factor for frequent hospitalizations in older adults with polypharmacy: a pilot study. Pharmgenomics Pers Med. 2016 Oct;Volume 9:107–16. [CrossRef]

- Petrović J, Pešić V, Lauschke VM. Frequencies of clinically important CYP2C19 and CYP2D6 alleles are graded across Europe. European Journal of Human Genetics. 2020 Jan 29;28(1):88–94. [CrossRef]

- El Rouby N, Alrwisan A, Langaee T, Lipori G, Angiolillo DJ, Franchi F, et al. Clinical Utility of Pharmacogene Panel-Based Testing in Patients Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Clin Transl Sci. 2020 May 16;13(3):473–81. [CrossRef]

- Johnson SG, Shaw PB, Delate T, Kurz DL, Gregg D, Darnell JC, et al. Feasibility of clinical pharmacist-led CYP2C19 genotyping for patients receiving non-emergent cardiac catheterization in an integrated health system. Pharm Pract (Granada). 2017 Jun 30;15(2):946–946. [CrossRef]

- Dawes M, Esquivel B. Pharmacogenetics Implementation in Primary Care. Med Res Arch. 2022;10(8).

- Molden E, Jukić MM. CYP2D6 Reduced Function Variants and Genotype/Phenotype Translations of CYP2D6 Intermediate Metabolizers: Implications for Personalized Drug Dosing in Psychiatry. Front Pharmacol. 2021 Apr 22;12. [CrossRef]

- McDermott JH, Wright S, Sharma V, Newman WG, Payne K, Wilson P. Characterizing pharmacogenetic programs using the consolidated framework for implementation research: A structured scoping review. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022 Aug 18;9. [CrossRef]

- Dalton R, Lee S, Claw KG, Prasad B, Phillips BR, Shen DD, et al. Interrogation of <scp>CYP</scp> 2D6 Structural Variant Alleles Improves the Correlation Between <scp>CYP</scp> 2D6 Genotype and <scp>CYP</scp> 2D6-Mediated Metabolic Activity. Clin Transl Sci. 2020 Jan 25;13(1):147–56.

- Zembutsu H, Nakamura S, Akashi-Tanaka S, Kuwayama T, Watanabe C, Takamaru T, et al. Significant Effect of Polymorphisms in CYP2D6 on Response to Tamoxifen Therapy for Breast Cancer: A Prospective Multicenter Study. Clinical Cancer Research. 2017 Apr 15;23(8):2019–26.

- Ammar R, Paton TA, Torti D, Shlien A, Bader GD. Long read nanopore sequencing for detection of HLA and CYP2D6 variants and haplotypes. F1000Res. 2015 Jan 21;4:17. [CrossRef]

- El Akil S, Elouilamine E, Ighid N, Izaabel EH. Explore the distribution of (rs35742686, rs3892097 and rs1065852) genetic polymorphisms of cytochrome P4502D6 gene in the Moroccan population. Egyptian Journal of Medical Human Genetics. 2022 Nov 21;23(1):153. [CrossRef]

- Qiao W, Yang Y, Sebra R, Mendiratta G, Gaedigk A, Desnick RJ, et al. Long-Read Single Molecule Real-Time Full Gene Sequencing of Cytochrome P450-2D6. Hum Mutat. 2016 Mar;37(3):315–23. [CrossRef]

- Gaedigk A, Riffel AK, Leeder JS. CYP2D6 Haplotype Determination Using Long Range Allele-Specific Amplification. The Journal of Molecular Diagnostics. 2015 Nov;17(6):740–8. [CrossRef]

- Chin FW, Chan SC, Abdul Rahman S, Noor Akmal S, Rosli R. CYP2D6 Genetic Polymorphisms and Phenotypes in Different Ethnicities of Malaysian Breast Cancer Patients. Breast J. 2016 Jan;22(1):54–62. [CrossRef]

- Pristup J, Schaeffeler E, Arjune S, Hofmann U, Angel Santamaria-Araujo J, Leuthold P, et al. Molybdenum Cofactor Catabolism Unravels the Physiological Role of the Drug Metabolizing Enzyme Thiopurine S-Methyltransferase. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2022 Oct 31;112(4):808–16. [CrossRef]

- Krynetski EY, Schuetz JD, Galpin AJ, Pui CH, Relling M V, Evans WE. A single point mutation leading to loss of catalytic activity in human thiopurine S-methyltransferase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1995 Feb 14;92(4):949–53. [CrossRef]

- Shaaban S, Walker BS, Ji Y, Johnson-Davis K. TPMT and NUDT15 genotyping, TPMT enzyme activity and metabolite determination for thiopurines therapy: a reference laboratory experience. Pharmacogenomics. 2024 Dec 11;25(16–18):679–88. [CrossRef]

- Ladić A. AN EPIDEMIOLOGICAL STUDY OF THIOPURINEMETHYLTRANSFERASE VARIANTS IN A CROATIAN INFLAMMATORY BOWEL DISEASE PATIENT COHORT. Acta Clin Croat. 2016;16–22. [CrossRef]

- Almoguera B, Vazquez L, Connolly JJ, Bradfield J, Sleiman P, Keating B, et al. Imputation of TPMT defective alleles for the identification of patients with high-risk phenotypes. Front Genet. 2014 May 12;5. [CrossRef]

- Esraa Ali Kadhum, Manal K Rasheed, Hasanein H.Ghali. Thiopurine S-Methyltransferase Genotyping in Iraqi Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Patients ; A Single Institute Study. Indian Journal of Forensic Medicine & Toxicology. 2021 Nov 30;16(1):1647–52. [CrossRef]

- Tamm R, Mägi R, Tremmel R, Winter S, Mihailov E, Smid A, et al. Polymorphic Variation in TPMT Is the Principal Determinant of TPMT Phenotype: A Meta-Analysis of Three Genome-Wide Association Studies. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2017 May;101(5):684–95. [CrossRef]

- Van Cott EM, Khor B, Zehnder JL. Factor <scp>V</scp> <scp>L</scp> eiden. Am J Hematol. 2016 Jan 17;91(1):46–9.

- Grewal I, Elsemary O, Nasim S, Almullahassani A. Early Recognition of Signs of Hypercoagulability to Prevent Adverse Health Outcomes. Clinical Case Reports and Studies. 2023 May 23;2(4). [CrossRef]

- Heraudeau A, Delluc A, Le Henaff M, Lacut K, Leroyer C, Desrues B, et al. Risk of venous thromboembolism in association with factor V leiden in cancer patients – The EDITH case-control study. PLoS One. 2018 May 18;13(5):e0194973. [CrossRef]

- Simone B, De Stefano V, Leoncini E, Zacho J, Martinelli I, Emmerich J, et al. Risk of venous thromboembolism associated with single and combined effects of Factor V Leiden, Prothrombin 20210A and Methylenetethraydrofolate reductase C677T: a meta-analysis involving over 11,000 cases and 21,000 controls. Eur J Epidemiol. 2013 Aug 31;28(8):621–47. [CrossRef]

- Tuncay A, Sener EF, Emirogullari ON. Investigation of Genetic Polymorphisms in Infective Endocarditis and Artificial Valve Thrombosis. Erciyes Tıp Dergisi/Erciyes Medical Journal. 2017 Jul 10;39(2):63–6. [CrossRef]

- Ottaviani A, Mansour D, Molinari L V., Galanti K, Mantini C, Khanji MY, et al. Revisiting Diagnosis and Treatment of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: Current Practice and Novel Perspectives. J Clin Med. 2023 Sep 1;12(17):5710. [CrossRef]

- Pop C, Cristina A, Iaru I, Popa SL, Mogoșan C. Nation-Wide Survey Assessing the Knowledge and Attitudes of Romanian Pharmacists Concerning Pharmacogenetics. Front Pharmacol. 2022 Jul 1;13. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).