1. Introduction

Public health measures implemented across many countries during the COVID-19 pandemic significantly reduced hospital admissions for non-COVID-related conditions. This decline was largely attributed to reduced transmission of respiratory viruses and a subsequent decrease in bacterial infections [

1].

In Italy, as in other European nations, NPIs varied in intensity throughout the pandemic. These measures were strictest in 2020 and extended until the spring of 2022, after which a gradual relaxation occurred, culminating in the complete withdrawal of any restriction by May 2023. With easing of NPIs epidemiological data indicate some resurgence of respiratory pathogens, notably RSV and other respiratory viruses and bacteria. However, there is no systematic study that have comprehensively examined the impact of these NPIs, and their subsequent removal, on hospitalizations for LRTIs, particularly among individuals with CRDs [

2]. IE is a global concern with an increasing incidence over the past few years [

3,

4]. Its clinical expression varies in a broad range of multisystemic manifestations and potential complications. Despite advances in diagnostic techniques and therapeutic interventions, mortality associated with IE remains high. In-hospital mortality rates range from 8% to 40% depending on population characteristics and study methodologies [

5]. Recent large-scale, multicenter studies, such as the EURO-ENDO Registry, report an in-hospital mortality rate of approximately 17%, with no observed decline in both developed and developing regions [

6]. Mortality exceeds 30% in critically ill patients, such as those requiring intensive care, highlighting the severe nature of the disease in these cases [

7].

To date, no studies have explored the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the epidemiology and severity of IE. Therefore, we aimed to assess and quantify the pandemic's effect on hospitalization trends, mortality rates, and the clinical characteristics and severity of IE in patients during and after the pandemic.

2. Study Design and Patients

In this retrospective case-series population study all patients referred to our center for suspected IE from January 1, 2017, to March 1, 2025, were enrolled. If they met the established criteria for a definite diagnosis of IE [

8] confirmed by the HCDD, they were categorized into three cohorts based on the time of diagnosis:

Pre-Pandemic group: Patients diagnosed from January 1, 2017, to March 10, 2020.

Pandemic group: Patients diagnosed between March 11, 2020, and March 20, 2022.

Post-Pandemic group: Patients diagnosed from March 21, 2022, to February 28, 2025.

2.1. Data Collection

Epidemiological Data: Clinical risk factors were recorded, including underlying heart conditions, heart failure upon admission, renal insufficiency, diabetes, embolic events, septic shock, COPD, peripheral vascular disease, immunocompromised status, and intravenous drug use.

Microbiological Features: Blood cultures, serology, and valve/tissue cultures were collected. Blood cultures were drawn from at least three separate samples before initiating antibiotic therapy. Additional cultures were obtained in cases requiring valve surgery or pacemaker/lead extraction.

Echocardiographic Findings: The largest vegetation length was measured. In the absence of vegetation, other echocardiographic criteria were assessed, such as new valvular regurgitation, flail leaflets, prosthesis dehiscence, abscess formation, pseudoaneurysm, fistula, or new valvular perforation.

Outcome Measurement: In-hospital mortality was recorded and analyzed.

2.2. Definitions

Underlying conditions were assessed using the CCI [

9], which classifies comorbidity severity into three categories: mild (CCI score of 1-2), moderate (CCI score of 3-4), and severe (CCI score ≥5).

The definitions of paravalvular abscess and pseudoaneurysm followed the European Society of Cardiology guidelines and were included under the broader category of “perivalvular extension” of infection [

8].

Sepsis was defined as life-threatening organ dysfunction resulting from a dysregulated host response to infection, characterized by an increase of 2 or more points in the SOFA score [

10]. A higher SOFA score indicated strong sepsis.

Septic shock was defined as a more severe subset of sepsis, associated with profound circulatory, cellular, and metabolic abnormalities, leading to an increased risk of mortality compared to sepsis alone. Clinically, septic shock was identified by the need for vasopressors to maintain a mean arterial pressure of ≥65 mm Hg, along with a serum lactate level >2 mmol/L (>18 mg/dL) in the absence of hypovolemia [

11]. Cardiogenic shock was defined as acute circulatory failure caused by myocardial dysfunction, characterized by a systolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg, tissue hypoperfusion, and a reduced cardiac index. [

12] Surgical indications and timing followed the current guidelines. [

8]

In-hospital mortality was defined as death occurring during the same hospital admission, irrespective of the underlying cause.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

The incidence rate per 100,000 inhabitants per year was calculated.

Continuous variables were expressed in mean ± SD in the case of normal distribution or median (interquartile) with non-normal distribution. The comparison of normal continuous variables was performed by t-test for 2 samples. Non-normally distributed variables were compared by the Mann–Whitney U-test. The comparison between variables in frequencies was performed using the chi-square test. The normality of continuous variables was tested by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test for all continuous variables (backward selection).

Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed on various clinical parameters, including causative microorganisms, persistent bacteremia, diabetes, renal insufficiency, heart failure, embolic events, neurological complications, septic shock, age, sex, COPD, peripheral vasculopathy, predisposing factors, community- or healthcare-acquired infections, valve involvement, prosthetic versus native valve IE, catheter-related IE, indications for surgery, cases where surgery was indicated but not performed

Actuarial survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan–Meier method, with the day of diagnosis as the starting point; in-hospital survival was estimated. Survival curves were compared using the log-rank test. The Kaplan–Meier curve was also made for survival analysis stratified by Period. Significance was calculated by the log-rank test. Hazard ratios and CIs for death were based on the Cox proportional hazards model (back-ward selection). This multivariate model included the variables that were significant in the univariate analysis with P <.1 and the most relevant clinical characteristics. A P-value of less than .05 was considered statistically significant. R Cran 3.3.0 for Windows 11 was used for all analyses.

3. Results

During the study period 597 patients were referred to our center for suspected IE. Of these, a total of 186 confirmed hospitalized cases of IE were diagnosed, with 81 cases occurring pre-pandemic, 35 during the COVID-19 pandemic, and 67 in the post-pandemic period. Pre-pandemic follow-up was 38.0 months, pandemic was 24.5 months, and post-pandemic was 35.4 months. Most cases involved male patients (55.56%, n=104), with a median age of 67.88±16.32 years. Baseline characteristics of the study population are presented in

Table 1.

Notably, patients admitted during the post-pandemic period were significantly younger than those in the pre-pandemic and pandemic groups 69.10 [21.0-89.30] years vs. 77.20 [28.9-90.90] years vs. 73.60 [41.80-93.55] years,

p=0.010). The aortic valve was the most involved (

Table S1). Prosthetic involvement occurred in 27.30%. IVDA was not significantly increased post-pandemic (12.80% vs 11.80% vs 25.30%, p=0.070). The Charleston Comorbidity Index was significantly higher in post-pandemic patients than in those of the pre-pandemic period (5.14±3.24 vs 2.78±2.18, p=0.000). The main results of the study are summarized in

Table 2.

Since 2022, there has been an increase in hospitalizations (67 post-pandemic vs. 35 during the pandemic), approaching the pre-pandemic levels.

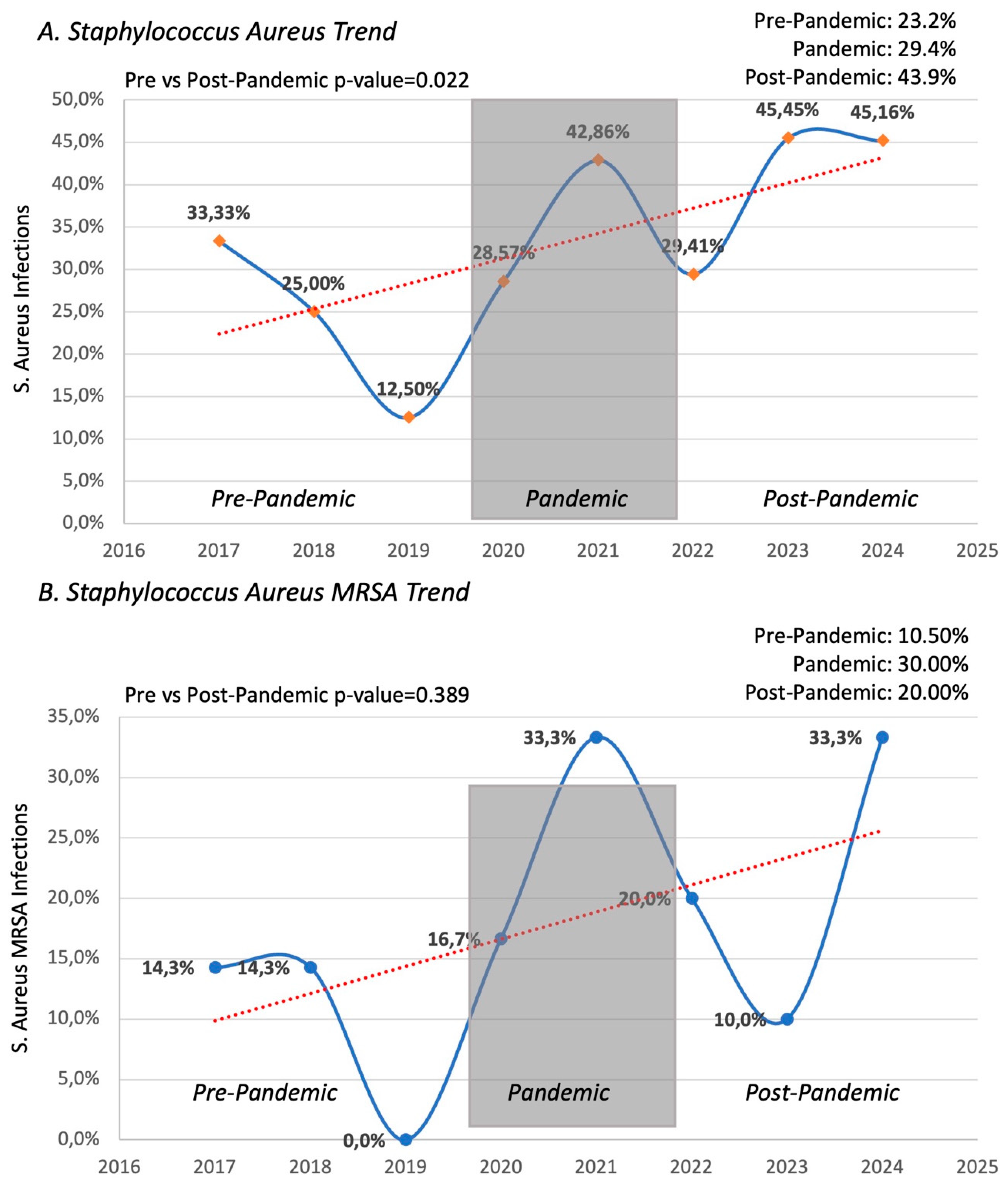

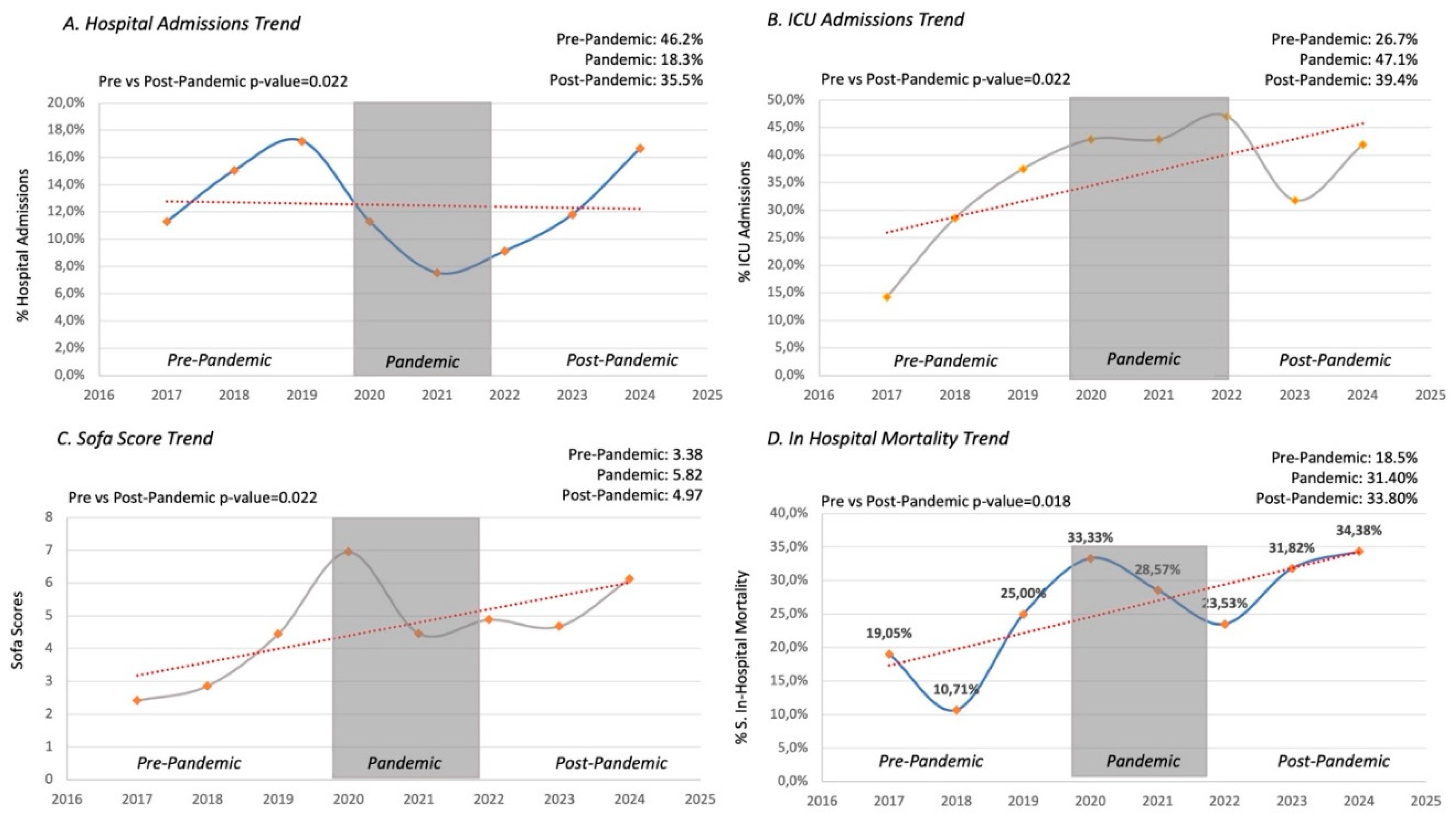

A significant rise in the incidence of Staphylococcus aureus infections across the pre-pandemic, pandemic, and post-pandemic was recorded (23.2% vs. 29.4% vs. 44.7%, p=0.022). A trend toward a rise in the MRSA infections post-pandemic was noticed, but it did not reach statistically significance vs the pre-pandemic period (20.0% vs 10.5%, p=0.389). Similarly, the incidence of sepsis, defined by elevated blood lactate levels with peripheric hypoperfusion, increased during and after the pandemic compared to the pre-pandemic period (55.9% vs. 53.7% vs. 34.9%, p=0.044). There was also a significant elevation in the SOFA score during and after the pandemic compared to pre-pandemic values (4.97±3.64 vs. 5.82±4.85 vs. 3.38±2.74, p=0.018). Although an increase in embolic events, particularly cerebral septic embolism, was observed during the pandemic and post-pandemic (26.70% vs. 37.10% vs. 43.30%), this rise did not reach statistical significance (p=0.090). Additionally, there were no significant differences in the incidence of abscess formation across the three periods (p=0.742). An increase in AHF cases was observed during the pandemic, though no significant differences were found between the pre-pandemic and post-pandemic (11.80% vs. 19.80% vs. 27.40%, p=0.118).

The rate of ICU admissions increased during and after the pandemic compared to pre-pandemic levels (47.10% vs. 40.30% vs. 26.70%,

p=0.070). The temporal trends were illustrated in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2.

There was also a notable rise in the number of patients requiring both ICU admission and surgical intervention, although surgery could not be performed in some cases due to high operative risk (

Table S2).

During and post-pandemic, percentage of patients with indication to surgery which was not performed was higher compared to pre-pandemic (32.40% vs 29.40% vs 10.50%, p=0.001)

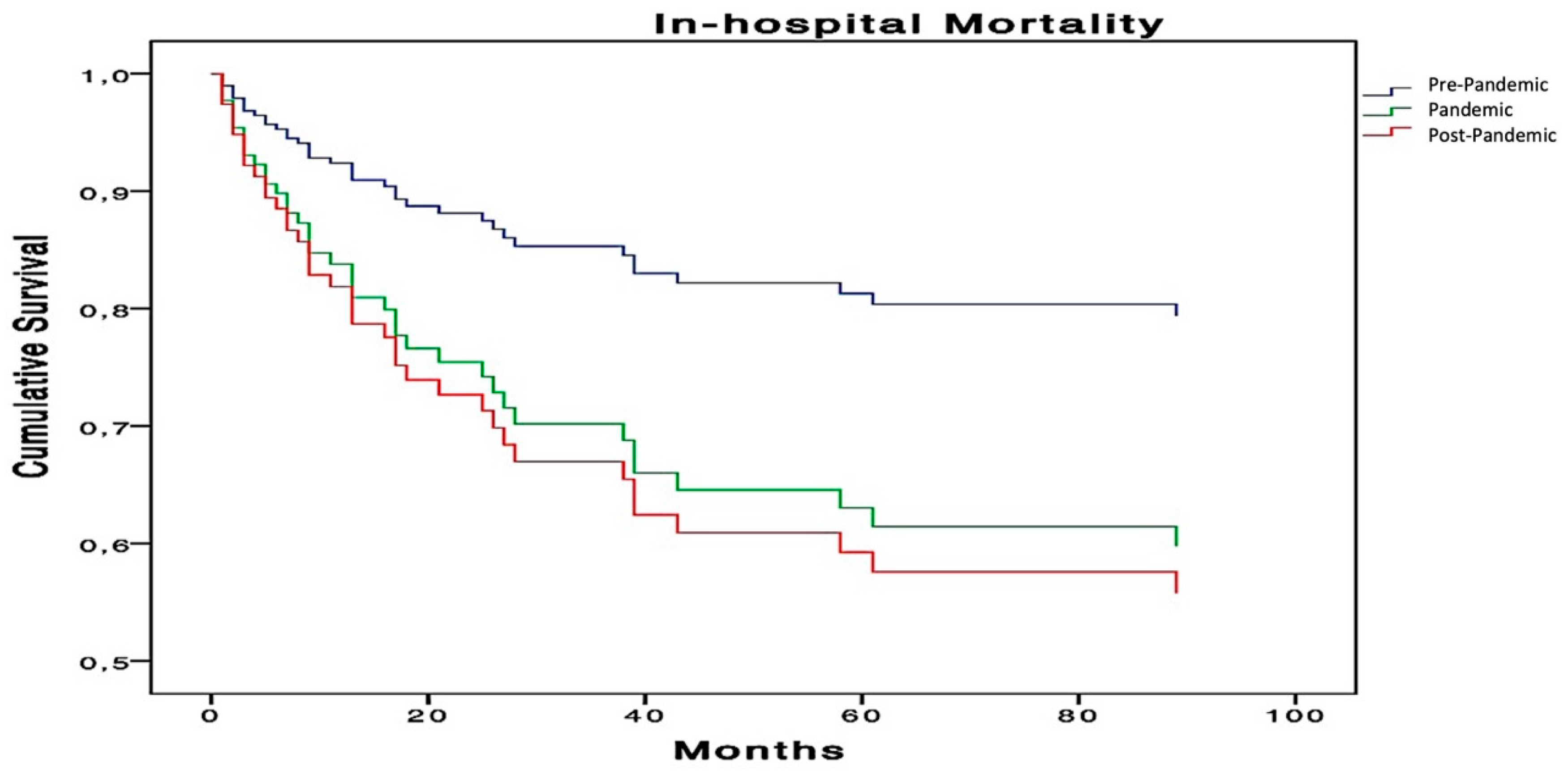

Kaplan-Meier survival curves (

Figure 3) revealed a significant increase in mortality during and after the pandemic (

p=0.018).

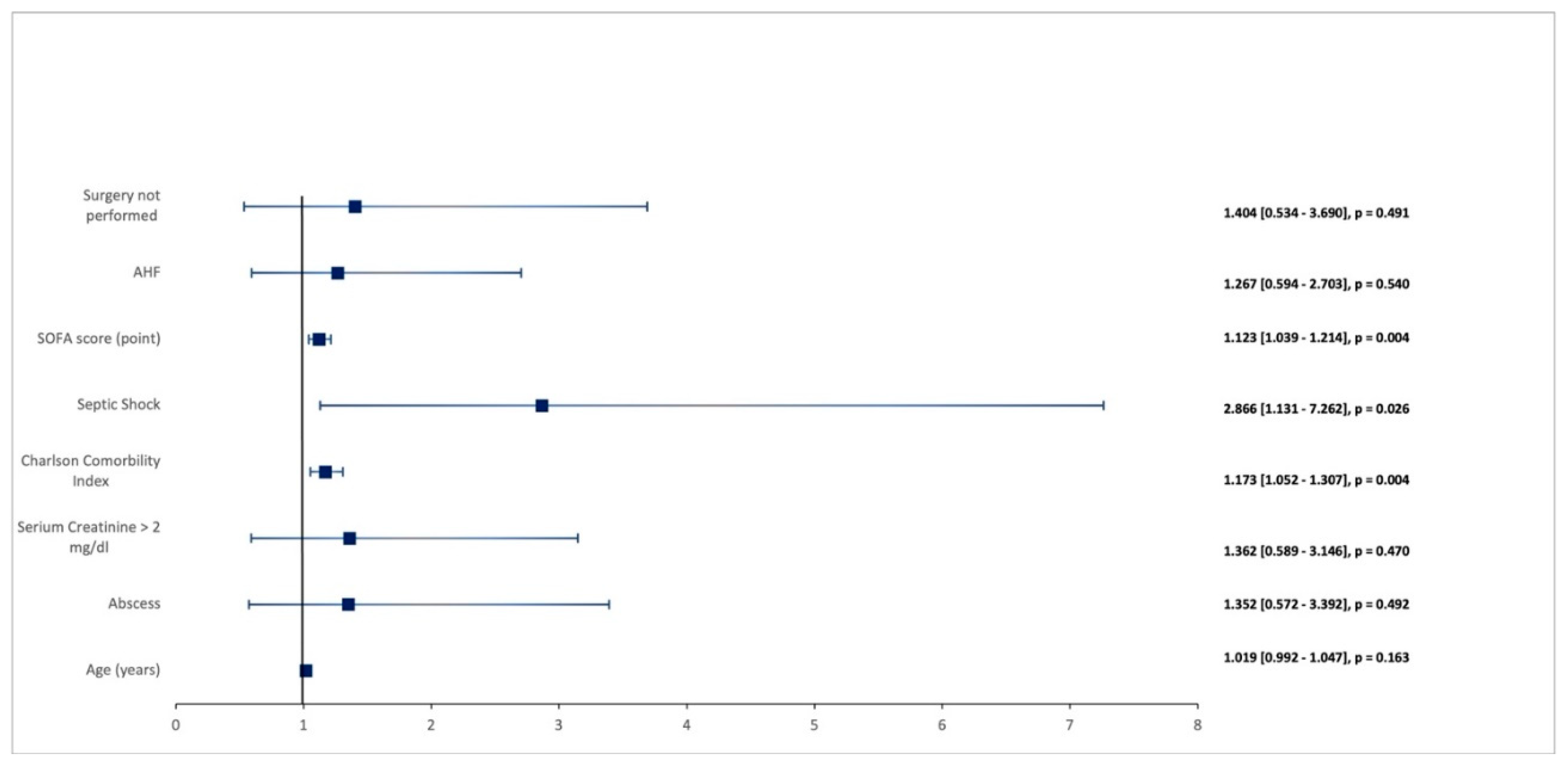

In the multivariate analysis, the rise in systemic sepsis (

Table 3 and

Figure 4) was also identified as a strong independent predictor of in-hospital mortality (

p=0.008).

4. Discussion

This study reports significant changes in the epidemiological patterns of infective endocarditis following the COVID-19 pandemic, reflecting broader trends observed in other viral and bacterial infections worldwide [

13]. First, we observed that after an initial decline in hospital admissions for non-COVID conditions during the pandemic, the number of admissions for endocarditis has been progressively returning to pre-pandemic levels following the relaxation of restrictive measures. Secondly, we noticed that the severity of endocarditis, which increased during the pandemic, has remained elevated compared to the pre-pandemic period. Specifically, during both the COVID and post-COVID periods, the observed rise in severe cases has been accompanied by an increased need for surgical intervention, but also by a higher number of patients with surgical indications who did not undergo surgery due to their more advanced disease state and subsequent inoperability. As previously observed in the EURO-ENDO registry [

6], the failure to perform indicated surgery is a key negative prognostic factor for mortality.

Reasons for this increased severity are multifactorial, mainly regarding two fundamental aspects: the higher frequency and selection of more aggressive and antibiotic-resistant bacteria and the greater frailty of patients.

Aspects related to infectious agents:

The easing of NPI has been associated with a resurgence of bacterial and viral infections, such as RSV and group A streptococcus [

14]. Indeed, we recorded a marked increase in infections caused by Staphylococcus aureus MSSA as well as MRSA. This late aspect has resulted in more severe septic conditions, with patients more frequently experiencing septic shock and higher SOFA scores during the pandemic and post-pandemic periods, leading to increased intensive care unit admissions. The EURO-ENDO registry [

6] has already established that S. aureus infection is another strong independent prognostic predictor of mortality in patients with IE. Therefore, the increased circulation of more aggressive and resistant pathogens could be one of the drivers of this worsening clinical picture.

Similar findings have been reported by other authors about Staphylococcus aureus infections. In a meta-analysis, Abubakar et al. [

15] reported that most studies (54.5%) indicated an increase in S. aureus infection/colonisation, particularly of MRSA, during the pandemic, with increases ranging from 4.6% to 170.6%. The excessive use of antibiotics during the COVID-19 period exacerbated antibiotic resistance in certain bacteria, as observed in previous years. This phenomenon during COVID-19 could be attributed not only to the overuse of antibiotics but also to the reduction of routine healthcare services.

Several authors have reported a growing rate in infections caused by antibiotic-resistant pathogens, such as MRSA and multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Musuroi et al. [

16] noted a significant increase in the frequency of non-fermenting Gram-negative bacteria, particularly

Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, between 2020 and 2023, alongside rising antimicrobial resistance in Pseudomonas and Klebsiella species. Although the frequency of Klebsiella pneumoniae infections remained stable at 7%, there was a significant rise in the incidence of pan-drug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae strains (40%), including resistance to colistin. This phenomenon may be explained by the selection of strains carrying multiple resistance genes because of antibiotic treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic. Xing et al. [

17] demonstrated a resurgence of macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections, with a high incidence (around 85%) of macrolide resistance. The authors emphasised that this significant winter epidemic of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections, alongside antibiotic resistance, may be attributed to reduced immunity and increased population susceptibility resulting from the lack of exposure to these agents during the pandemic years.

Patient-related aspects:

Another mechanism contributing to the worsening clinical profiles and increased mortality may be the greater frailty of patients. In our study, even though patients were younger, they were more compromised, presenting with more comorbidities compared to the pre-pandemic period, as indicated by the Charlson comorbidity index. One possible reason for this could be the delay in screening for various oncological and cardiovascular conditions during the pandemic. The lack of screening and access to treatment led to an increase in late-stage diagnoses of cancers and other chronic diseases. Pellegrini et al. [

18] found that the disruption of healthcare systems caused by the COVID-19 pandemic led to a significant shift toward more advanced melanoma diagnoses with a less favourable prognosis.

Similarly, Tarawneh et al. [

19] reported higher-stage lung cancer diagnoses during the pandemic, although no clinically significant delays in treatment were observed. A UK-based study highlighted how the absence of screening during the pandemic could lead to diagnostic delays with negative consequences on cancer staging, treatment initiation, mortality rates, and years of life lost [

20].

Furthermore, the use of NPI and social restrictions reduced the circulation of bacteria and viruses, leading to a loss of natural immunity, particularly among these more vulnerable patients. Post-pandemic studies on respiratory infections demonstrate similar patterns of delayed resurgence and increased severity. Chow et al. [

21] reported a resurgence of respiratory viruses, such as RSV, following the easing of NPI, exacerbated by decreased natural immunity due to the pandemic.

Goldberg-Bockhorn et al. [

22] demonstrated that the reduced immune system exposure to pathogens during the pandemic, combined with the subsequent increase in respiratory viral infections, likely explains the exceptionally high post-pandemic surge of iGAS infections and the rise in invasive pulmonary diseases across Europe. This post-pandemic increase in infections was particularly pronounced among children under 10 and older adults; in Germany, it affected all age groups equally but was most prevalent in individuals over 65.

This decline in immunity has likely also contributed to the resurgence and severity of IE cases observed in this study. Therefore, the post-pandemic rebound of viral and bacterial infections has encountered a more fragile patient population unable to mount an adequate immune response, leading to more severe clinical presentations.

4.1. Study Limitations

This study has several limitations that should be recognised to properly contextualise the findings. First, its retrospective design might introduce biases, as the data were sourced from existing hospital records. Second, conducting the study at a single center may restrict the generalizability of the results. Third, the classification of patients into pre-pandemic, pandemic, and post-pandemic groups relies on specific timeframes, which may overlook other external factors affecting hospitalisation and mortality rates. Fourth, although the research included a considerable number of patients (186 confirmed cases), the sample sizes in the temporal cohorts may be too small to draw definitive conclusions about trends within certain subpopulations or rare outcomes. Fifth, while the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) was used to evaluate underlying conditions, it may not fully capture the range of patient frailty or functional status, as factors like social determinants of health were not included in the analysis. Sixth, the choice to perform surgical interventions was based on clinical judgment and may have been influenced by factors such as hospital resources and physician preferences, potentially leading to variability in treatment strategies across cohorts. Lastly, despite the statistical analyses performed, there remains a possibility of residual confounding from unmeasured variables that could impact the outcomes of interest.

5. Conclusion

In-hospital mortality from infective endocarditis has remained high post-pandemic, largely due to the increased systemic severity associated with a rise in frequency and more resistant bacterial infections. This trend may be a consequence of the surge in antibiotic resistance during the COVID-19 pandemic, exacerbated by the rapid easing of restrictions and a potential decline in natural immunity following extended NPIs.

These findings highlight the need for ongoing monitoring of antibiotic resistance patterns, enhanced infection prevention strategies, and optimised treatment protocols to tackle the evolving challenges posed by IE in the post-pandemic landscape.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Each author has contributed significantly to the present work. All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Pasquale Baratta, Francesco De Sensi, Bruno Sposato and Alberto Cresti. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Pasquale Baratta, Francesco De Sensi and Alberto Cresti and supervised by Ugo Limbruno. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

No funding sources were involved in the research.

Ethics approval

This research study was conducted retrospectively from data obtained for clinical purposes. All the procedures being performed were part of the routine clinical care. The study was conducted according to the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and authors are complying with the specific requirements of their institution and their countries. Misericordia’s Hospital ethics committee approved the study, N: 23876-2024-12.

Informed Consent Statement

Consent to participate/consent of publication. Informed consent was obtained from each patient.

Data Availability Statement

The corresponding author keeps all the material relating to each patient included in the study. This material is available for evaluation at Editors discretion.

Conflicts of interest/Competing interests

All the authors report they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Abbreviation

| AHF |

acute heart failure |

| CCI |

Charlson Comorbidity Index |

| COPD |

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| COVID-19 |

Coronavirus-19 Infection Disease |

| CRDs |

chronic respiratory diseases |

| CVC |

central venous catheter |

| GCS |

Glasgow Coma Scale |

| HCDD |

Hospital clinical digital database |

| HF |

heart failure |

| ICU |

intensive care unit |

| IE |

Infective Endocarditis |

| iGAS |

invasive group A streptococcal disease |

| IVDA |

intravenous drug abuse |

| LRTIs |

lower respiratory tract infections |

| LVEF |

left ventricular ejection fraction |

| MRSA |

methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus |

| MSSA |

methicillin-sensible Staphylococcus aureus |

| NPIs |

non-pharmaceutical interventions |

| OTI |

oratracheal intubation |

| PMK |

pacemaker |

| RSV |

respiratory syncytial virus |

| SOFA |

Sequential Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment |

References

- Chow EJ, Uyeki TM, Chu HY. The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on community respiratory virus activity. Nat Rev Microbiol 2023;21(3):195–210. [CrossRef]

- Xing FF, Chiu KH, Deng CW, Ye HY, Sun LL, Su YX, Cai HJ, Lo SK, Rong L, Chen JL, Cheng VC, Lung DC, Sridhar S, Chan JF, Hung IF, Yuen KY. Post-COVID-19 Pandemic Rebound of Macrolide-Resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae Infection: A Descriptive Study. Antibiotics (Basel). 2024 Mar 15;13(3):262. [CrossRef]

- Dayer MJ, Jones S, Prendergast B, Baddour LM, Lockhart PB, Thornhill MH. An increase in the incidence of infective endocarditis in England since 2008: a secular trend interrupted time series analysis. Lancet. 2015;385(9974):1219-1228.

- Cresti A, Chiavarelli M, Scalese M, et al. Epidemiological and mortality trends in infective endocarditis, a 17-year population-based prospective study. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2017;7(1):27-35. [CrossRef]

- Morelli S, De Marzio P, Voci P, Troisi G. Infective endocarditis. Recent progress in its epidemiology, clinical picture and therapy. Comments on cases. Recenti Prog Med. 1994;85(7-8):368-374. Khanal B, Harish BN, Sethuraman KR, Srinivasan S. Infective endocarditis: report of a prospective study in an Indian hospital. Trop Doct. 2002;32(2):83-85.

- Habib G, Lancellotti P, Erba PA, et al. The ESC-EORP EURO- ENDO (European Infective Endocarditis) registry. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. 2019;5(3):202-207. 1062.

- Cresti A, Baratta P, De Sensi F, Aloia E, Sposato B, Limbruno U. Clinical Features and Mortality Rate of Infective Endocarditis in Intensive Care Unit: A Large-Scale Study and Literature Review. Anatol J Cardiol. 2024 Jan;28(1):44-54.

- Habib G, Lancellotti P, Antunes MJ, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis: the Task Force for the Management of Infective Endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Endorsed by: European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS), the European association of nuclear medicine (EANM) Eur Heart J. 2015;36(44):3075-3128.

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373-383. [CrossRef]

- Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J, et al. The SOFA (Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/ failure. On behalf of the Working Group on Sepsis-Related Problems of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med. 1996;22(7):707-710.

- Singer et al.'s "Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock Sepsis-3" provided the reference for these criteria JAMA, 2016.

- van Diepen S, Katz JN, Albert NM, Henry TD, Jacobs AK, Kapur NK, Kilic A, Menon V, Ohman EM, Sweitzer NK, Thiele H, Washam JB, Cohen MG. Contemporary Management of Cardiogenic Shock: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research; and Mission: Lifeline. Circulation. 2017 Oct 17;136(16):e232-e268.

- World Health Organization (23 November 2023). Disease Outbreak News; Upsurge of respiratory illnesses among children in northern China. Available at: https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2023-DON494.

- Sturm LK, Saake K, Roberts PB, Masoudi FA, Fakih MG. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on hospital onset bloodstream infections (HOBSI) at a large health system. Am J Infect Control. 2022 Mar;50(3):245-249. [CrossRef]

- Abubakar U, Al-Anazi M, Alanazi Z, Rodríguez-Baño J. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on multidrug resistant gram positive and gram negative pathogens: A systematic review. J Infect Public Health. 2023 Mar;16(3):320-331. [CrossRef]

- Corina Musuroi, Silvia-Ioana Musuroi, Luminita Baditoiu, Zorin Crainiceanu, Delia Muntean, Adela Voinescu, Oana Izmendi, Alexandra Sirmon, Monica Licker. The Profile of Bacterial Infections in a Burn Unit during and after the COVID-19 Pandemic Period. Antibiotics (Basel) 2024 Aug 30;13(9):823. [CrossRef]

- Xing FF, Chiu KHY, Deng CW, Ye HY, Sun LL, Su YX, Cai HJ, Lo SKF, Rong L, Chen JL, et al. Post-COVID-19. Pandemic Rebound of Macrolide-Resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae Infection: A Descriptive Study. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 262.

- Pellegrini C, Caini S, Gaeta A, Lucantonio E, Mastrangelo M, Bruni M, Esposito M, Doccioli C, Queirolo P, Tosti G, Raimondi S, Gandini S, Fargnoli MC. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Delay of Melanoma Diagnosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers (Basel). 2024 Nov 5;16(22):3734. [CrossRef]

- Tarawneh TS, Mack EKM, Faoro C, Neubauer A, Middeke M, Kirschbaum A, Holland A. Diagnostic and therapeutic delays in lung cancer during the COVID-19pandemic: a single center experience at a German Cancer center. BMC Pulm Med. 2024 Jul 4;24(1):320. [CrossRef]

- Barclay NL, Pineda Moncusí M, Jödicke AM, Prieto-Alhambra D, Raventós B, Newby D, Delmestri A, Man WY, Chen X, Català M. The impact of the UK COVID-19 lockdown on the screening, diagnostics and incidence of breast, colorectal, lung and prostate cancer in the UK: a population-based cohort study.Front Oncol. 2024 Mar 27; 14:1370862. [CrossRef]

- Chow EJ, Uyeki TM, Chu HY. The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on community respiratory virus activity. Nat Rev Microbiol 2023;21(3):195–210. [CrossRef]

- Eva Goldberg-Bockhorn, Benjamin Hagemann, Martina Furitsch, Thomas K Hoffmann. Invasive Group A Streptococcal Infections in Europe After the COVID-19 Pandemic. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2024 Oct 4;121(20):673-680. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).