Submitted:

17 April 2025

Posted:

18 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

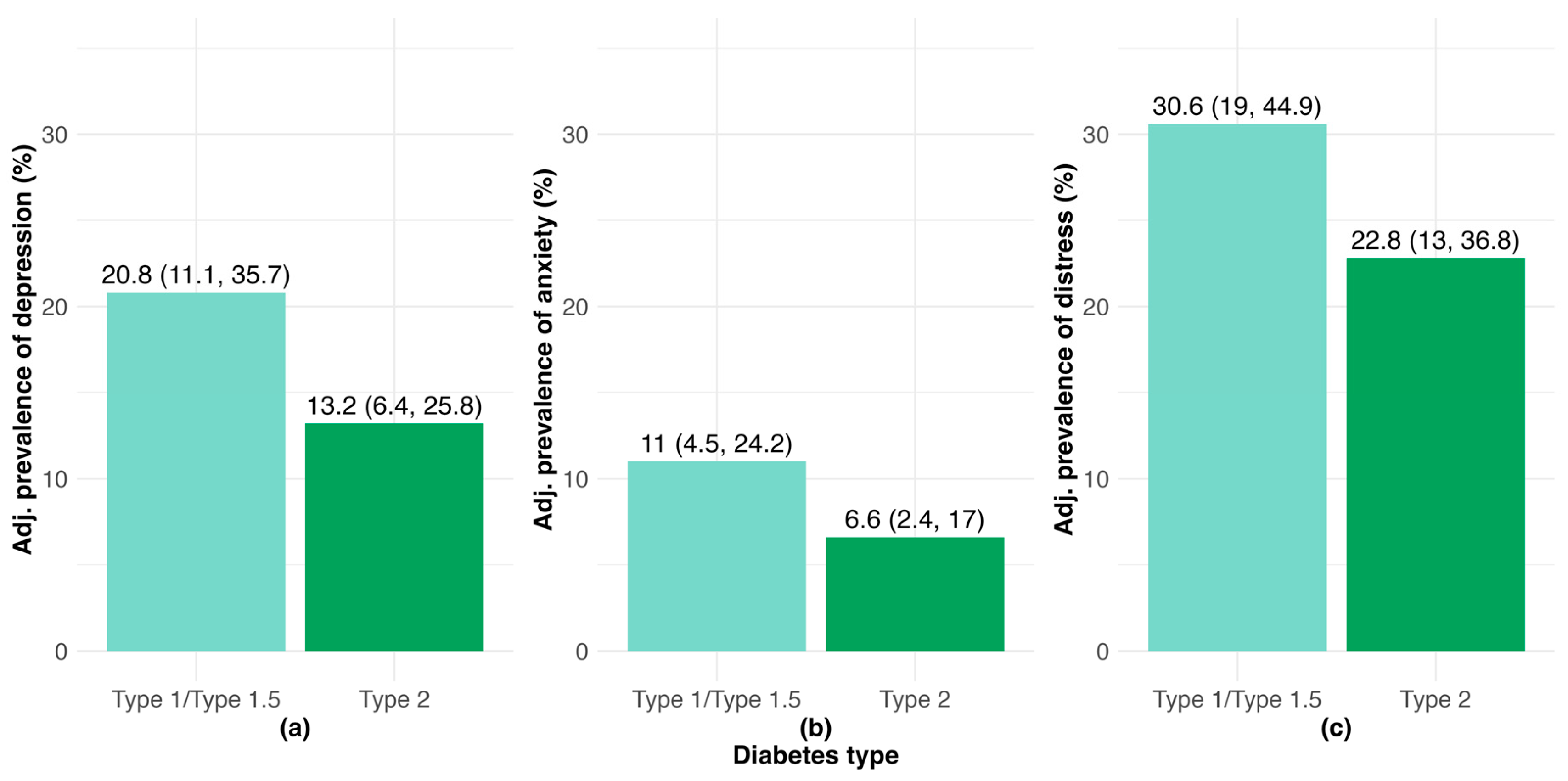

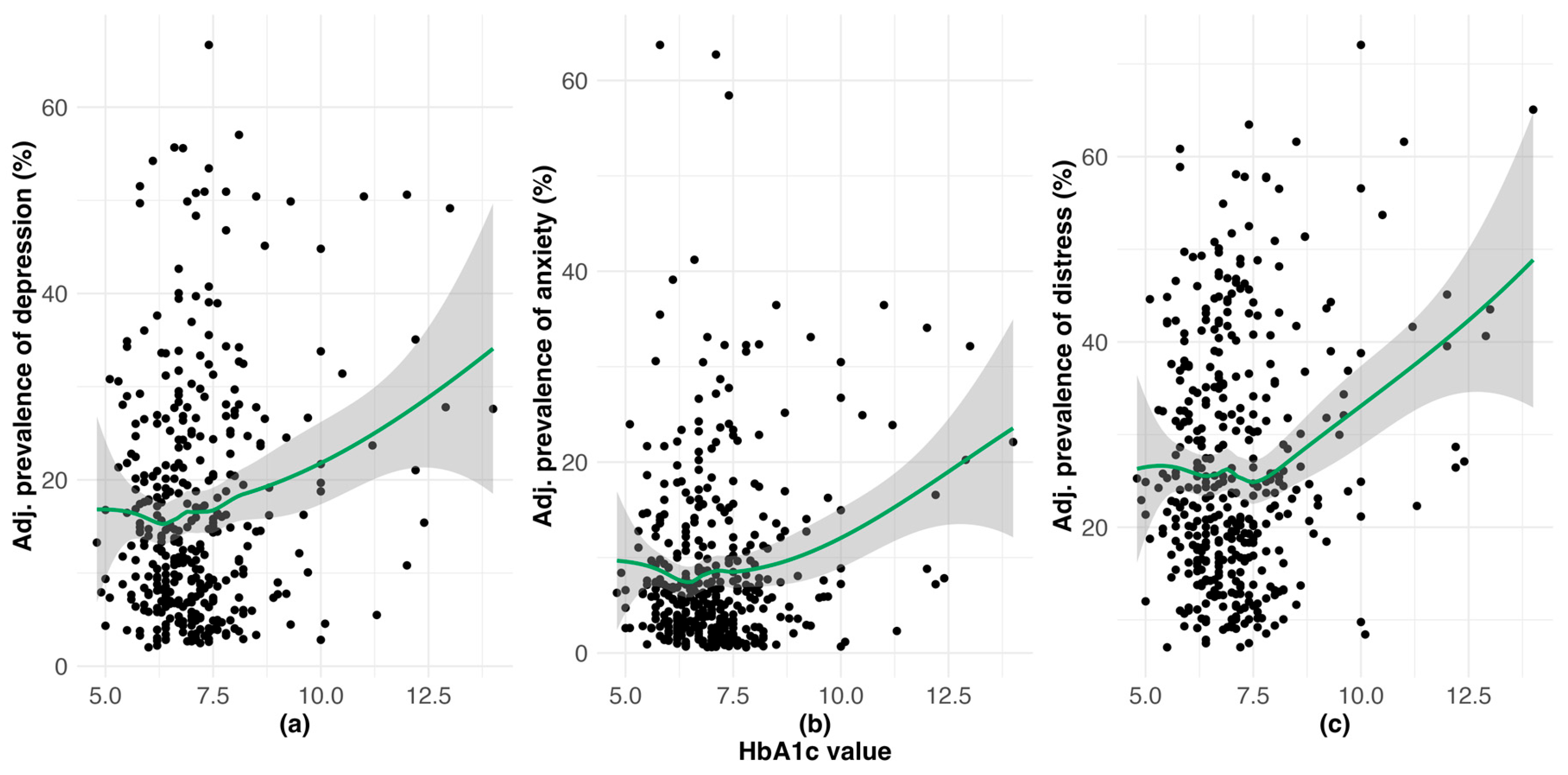

3.1. Burden of Clinically-Relevant Depression, Anxiety and DRD

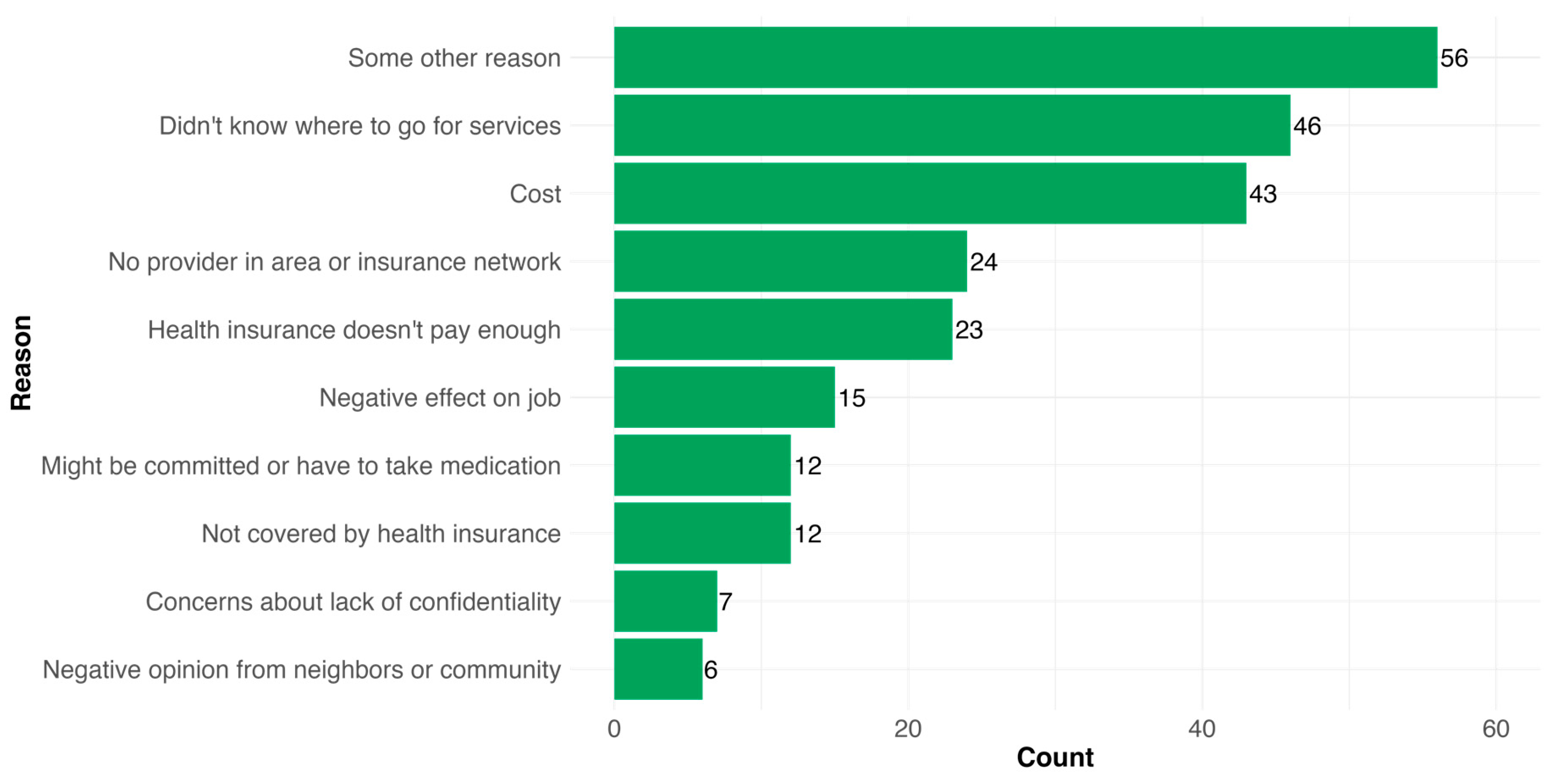

3.3. Mental Health Services Use and Barriers to Psychosocial Care Among PWD

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Young-Hyman, D.; De Groot, M.; Hill-Briggs, F.; Gonzalez, J.S.; Hood, K.; Peyrot, M. Psychosocial Care for People With Diabetes: A Position Statement of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2016, 39, 2126–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holt, R.I.G.; de Groot, M.; Golden, S.H. Diabetes and Depression. Curr. Diab. Rep. 2014, 14, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holt, R.I.G.; de Groot, M.; Lucki, I.; Hunter, C.M.; Sartorius, N.; Golden, S.H. NIDDK International Conference Report on Diabetes and Depression: Current Understanding and Future Directions. Diabetes Care 2014, 37, 2067–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mezuk, B.; Eaton, W.W.; Albrecht, S.; Golden, S.H. Depression and Type 2 Diabetes Over the Lifespan: A Meta-Analysis. Diabetes Care 2008, 31, 2383–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmans, R.S.; Rapp, A.; Kelly, K.M.; Weiss, D.; Mezuk, B. Understanding the Relationship between Type 2 Diabetes and Depression: Lessons from Genetically Informative Study Designs. Diabet. Med. 2021, 38, e14399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, S.H.; Lazo, M.; Carnethon, M.; Bertoni, A.G.; Schreiner, P.J.; Diez Roux, A.V.; Lee, H.B.; Lyketsos, C. Examining a Bidirectional Association Between Depressive Symptoms and Diabetes. JAMA 2008, 299, 2751–2759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Duinkerken, E.; Snoek, F.J.; De Wit, M. The Cognitive and Psychological Effects of Living with Type 1 Diabetes: A Narrative Review. Diabet. Med. 2020, 37, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, L.; Polonsky, W.H.; Hessler, D.M.; Masharani, U.; Blumer, I.; Peters, A.L.; Strycker, L.A.; Bowyer, V. Understanding the Sources of Diabetes Distress in Adults with Type 1 Diabetes. J. Diabetes Complications 2015, 29, 572–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Jing, L.; Wang, J. Does Depression Increase the Risk of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2022, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, C.A.; Newham, J.; Rankin, J.; Ismail, K.; Simonoff, E.; Reynolds, R.M.; Stoll, N.; Howard, L.M. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Risk of Gestational Diabetes in Women with Preconception Mental Disorders. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2022, 149, 293–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojujutari Ajele, K.; Sunday Idemudia, E. The Role of Depression and Diabetes Distress in Glycemic Control: A Meta-Analysis. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2025, 221, 112014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrin, N.E.; Davies, M.J.; Robertson, N.; Snoek, F.J.; Khunti, K. The Prevalence of Diabetes-specific Emotional Distress in People with Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Diabet. Med. 2017, 34, 1508–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolucci, A.; Kovacs Burns, K.; Holt, R.I.G.; Comaschi, M.; Hermanns, N.; Ishii, H.; Kokoszka, A.; Pouwer, F.; Skovlund, S.E.; Stuckey, H.; et al. Diabetes Attitudes, Wishes and Needs Second Study (DAWN2TM): Cross-national Benchmarking of Diabetes-related Psychosocial Outcomes for People with Diabetes. Diabet. Med. 2013, 30, 767–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snoek, F.J.; Bremmer, M.A.; Hermanns, N. Constructs of Depression and Distress in Diabetes: Time for an Appraisal. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2025, 3, 450–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, L.; Skaff, M.M.; Mullan, J.T.; Arean, P.; Mohr, D.; Masharani, U.; Glasgow, R.; Laurencin, G. Clinical Depression Versus Distress Among Patients With Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2007, 30, 542–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olfson, M.; Marcus, S.C. National Patterns in Antidepressant Medication Treatment. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2009, 66, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Rodríguez, R.; Zhao, L.; Bizzozero-Peroni, B.; Martínez-Vizcaíno, V.; Mesas, A.E.; Wittert, G.; Heilbronn, L.K. Are E-Health Interventions Effective in Reducing Diabetes-Related Distress and Depression in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes? A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Telemed. J. E-Health Off. J. Am. Telemed. Assoc. 2024, 30, 919–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkinson, E.; Knoop, I.; Hudson, J.L.; Moss-Morris, R.; Hackett, R.A. The Effectiveness of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy and Third-Wave Cognitive Behavioural Interventions on Diabetes-Related Distress: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Diabet. Med. J. Br. Diabet. Assoc. 2022, 39, e14948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Y.-X.; Ma, L.; Li, J.-P. Effects of Mindfulness-Based Intervention on Glycemic Control and Psychological Outcomes in People with Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Diabetes Investig. 2021, 12, 1092–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinger, K.; De Groot, M.; Cefalu, W.T. Psychosocial Research and Care in Diabetes: Altering Lives by Understanding Attitudes. Diabetes Care 2016, 39, 2122–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyrot, M.; Rubin, R.R.; Lauritzen, T.; Snoek, F.J.; Matthews, D.R.; Skovlund, S.E. Psychosocial Problems and Barriers to Improved Diabetes Management: Results of the Cross-National Diabetes Attitudes, Wishes and Needs (DAWN) Study. Diabet. Med. 2005, 22, 1379–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peyrot, M.; Burns, K.K.; Davies, M.; Forbes, A.; Hermanns, N.; Holt, R.; Kalra, S.; Nicolucci, A.; Pouwer, F.; Wens, J.; et al. Diabetes Attitudes Wishes and Needs 2 (DAWN2): A Multinational, Multi-Stakeholder Study of Psychosocial Issues in Diabetes and Person-Centred Diabetes Care. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2013, 99, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snoek, F.J.; Kersch, N.Y.A.; Eldrup, E.; Harman-Boehm, I.; Hermanns, N.; Kokoszka, A.; Matthews, D.R.; McGuire, B.E.; Pibernik-Okanović, M.; Singer, J.; et al. Monitoring of Individual Needs in Diabetes (MIND)-2: Follow-up Data from the Cross-National Diabetes Attitudes, Wishes, and Needs (DAWN) MIND Study. Diabetes Care 2012, 35, 2128–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermanns, N.; Caputo, S.; Dzida, G.; Khunti, K.; Meneghini, L.F.; Snoek, F. Screening, Evaluation and Management of Depression in People with Diabetes in Primary Care. Prim. Care Diabetes 2013, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behavioral Health Toolkit Available online: https://professional.diabetes.org/professional-development/behavioral-mental-health/behavioral-health-toolkit.

- Fagherazzi, G. Technologies Will Not Make Diabetes Disappear: How to Integrate the Concept of Diabetes Distress into Care. Diabetes Epidemiol. Manag. 2023, 11, 100140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, P.; Kobayasi, R.; Pereira, F.; Zaia, I.M.; Sasaki, S.U. Impact of Technology Use in Type 2 Diabetes Distress: A Systematic Review. World J. Diabetes 2020, 11, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Care Workforce: Key Issues, Challenges, and the Path Forward; Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2024.

- Caitlan DeVries; Briana Mezuk; Alana Ewen; Alejandro Rodríguez-Putnam Diabetes Mental Health Initiative: The 3-D Study of Self-Management and Mental Health: Diabetes, Distress, and Disparities Available online: https://osf.io/yfz6b/.

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W. The PHQ-9: Validity of a Brief Depression Severity Measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.W.; Löwe, B. A Brief Measure for Assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanulewicz, N.; Mansell, P.; Cooke, D.; Hopkins, D.; Speight, J.; Blake, H. PAID-11: A Brief Measure of Diabetes Distress Validated in Adults with Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2019, 149, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Deng, W.; Zhao, M. Influence of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Prevalence of Depression in U. S. Adults: Evidence from NHANES. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 3107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terlizzi, E.; Zablotsky, B. Symptoms of Anxiety and Depression Among Adults: United States, 2019 and 2022; National Health Statistics Reports; National Center for Health Statistics (U.S.): Hyattsville, MD, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Polonsky, W.H.; Fisher, L.; Hessler, D.; Desai, U.; King, S.B.; Perez-Nieves, M. Toward a More Comprehensive Understanding of the Emotional Side of Type 2 Diabetes: A Re-Envisioning of the Assessment of Diabetes Distress. J. Diabetes Complications 2021, 36, 108103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoffmann, V.; Kirkevold, M. Life Versus Disease in Difficult Diabetes Care: Conflicting Perspectives Disempower Patients and Professionals in Problem Solving. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 750–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratanawongsa, N.; Karter, A.J.; Parker, M.M.; Lyles, C.R.; Heisler, M.; Moffet, H.H.; Adler, N.; Warton, E.M.; Schillinger, D. Communication and Medication Adherence: The Diabetes Study of Northern California. JAMA Intern. Med. 2013, 173, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, Z.W.; O’Shields, J.; Ali, M.K.; Chwastiak, L.; Johnson, L.C.M. Effects of Integrated Care Approaches to Address Co-Occurring Depression and Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Diabetes Care 2024, 47, 2291–2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Korff, M.; Katon, W.; Bush, T.; Lin, E.H.B.; Simon, G.; Saunders, K.; Ludman, E.; Walker, E.; Unutzer, J. Treatment Costs, Cost Offset, and Cost-Effectiveness of Collaborative Management of Depression: Psychosom. Med. 1998, 60, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, G.E.; Katon, W.J.; VonKorff, M.; Unützer, J.; Lin, E.H.B.; Walker, E.A.; Bush, T.; Rutter, C.; Ludman, E. Cost-Effectiveness of a Collaborative Care Program for Primary Care Patients With Persistent Depression. Am. J. Psychiatry 2001, 158, 1638–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katon, W.; Russo, J.; Lin, E.H.B.; Schmittdiel, J.; Ciechanowski, P.; Ludman, E.; Peterson, D.; Young, B.; Von Korff, M. Cost-Effectiveness of a Multicondition Collaborative Care Intervention: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2012, 69, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davy, C.; Bleasel, J.; Liu, H.; Tchan, M.; Ponniah, S.; Brown, A. Factors Influencing the Implementation of Chronic Care Models: A Systematic Literature Review. BMC Fam. Pract. 2015, 16, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leidner, C.; Vennedey, V.; Hillen, H.; Ansmann, L.; Stock, S.; Kuntz, L.; Pfaff, H.; Hower, K.I. Implementation of Patient-Centred Care: Which System-Level Determinants Matter from a Decision Maker’s Perspective? Results from a Qualitative Interview Study across Various Health and Social Care Organisations. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e050054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vennedey, V.; Hower, K.I.; Hillen, H.; Ansmann, L.; Kuntz, L.; Stock, S. Patients’ Perspectives of Facilitators and Barriers to Patient-Centred Care: Insights from Qualitative Patient Interviews. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e033449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchendu, C.; Blake, H. Effectiveness of Cognitive–Behavioural Therapy on Glycaemic Control and Psychological Outcomes in Adults with Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Diabet. Med. 2016, 34, 328–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkley, K.; Ismail, K.; Landau, S.; Eisler, I. Psychological Interventions to Improve Glycaemic Control in Patients with Type 1 Diabetes: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. BMJ 2006, 333, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkley, K.; Upsher, R.; Stahl, D.; Pollard, D.; Kasera, A.; Brennan, A.; Heller, S.; Ismail, K. Psychological Interventions to Improve Self-Management of Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review. Health Technol. Assess. 2020, 24, 1–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zu, W.; Zhang, S.; Du, L.; Huang, X.; Nie, W.; Wang, L. The Effectiveness of Psychological Interventions on Diabetes Distress and Glycemic Level in Adults with Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2024, 24, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, H.; Hutter, N.; Bengel, J. Psychological and Pharmacological Interventions for Depression in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus and Depression. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Azmiardi, A.; Murti, B.; Febrinasari, R.P.; Tamtomo, D.G. The Effect of Peer Support in Diabetes Self-Management Education on Glycemic Control in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Epidemiol. Health 2021, 43, e2021090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heisler, M. Overview of Peer Support Models to Improve Diabetes Self-Management and Clinical Outcomes. Diabetes Spectr. 2007, 20, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermanns, N.; Ehrmann, D.; Finke-Groene, K.; Kulzer, B. Trends in Diabetes Self-Management Education: Where Are We Coming from and Where Are We Going? A Narrative Review. Diabet. Med. J. Br. Diabet. Assoc. 2020, 37, 436–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deverts, D.J.; Zupa, M.F.; Kieffer, E.C.; Gonzalez, S.; Guajardo, C.; Valbuena, F.; Piatt, G.A.; Yabes, J.G.; Lalama, C.; Heisler, M.; et al. Patient and Family Engagement in Culturally-Tailored Diabetes Self-Management Education in a Hispanic Community. Patient Educ. Couns. 2025, 134, 108669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosland, A.-M.; Piette, J.D.; Trivedi, R.; Lee, A.; Stoll, S.; Youk, A.O.; Obrosky, D.S.; Deverts, D.; Kerr, E.A.; Heisler, M. Effectiveness of a Health Coaching Intervention for Patient-Family Dyads to Improve Outcomes Among Adults With Diabetes: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2237960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saint, K.; Heisler, M. Experiences of Participants Who Then Become Coaches in a Peer Coach Diabetes Self-Management Program: Lessons for Future Programs. Chronic Illn. 2021, 19, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, I.; Gopaldasani, V.; Jain, V.; Chauhan, S.; Chawla, R.; Verma, P.K.; Hosseinzadeh, H. The Impact of Peer Coach-Led Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Interventions on Glycaemic Control and Self-Management Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Prim. Care Diabetes 2022, 16, 719–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, J.; Nguyen, K.; Winston, J.; Allen, J.O.; Smith, J.; Thornton, W.; Mejia Ruiz, M.J.; Mezuk, B. Promoting Sustained Diabetes Management: Identifying Challenges and Opportunities in Developing an Alumni Peer Support Component of the YMCA Diabetes Control Program. Patient Educ. Couns. 2022, 105, 1322–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atac, O.; Heier, K.R.; Moga, D.; Fowlkes, J.; Sohn, M.-W.; Kruse-Diehr, A.J.; Waters, T.M.; Lacy, M.E. Demographic Variation in Continuous Glucose Monitoring Utilisation among Patients with Type 1 Diabetes from a US Regional Academic Medical Centre: A Retrospective Cohort Study, 2018-2021. BMJ Open 2025, 15, e088785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostiuk, M.; Moore, S.L.; Kramer, E.S.; Gilens, J.F.; Sarwal, A.; Saxon, D.; Thomas, J.F.; Oser, T.K. Assessment and Intervention for Diabetes Distress in Primary Care Using Clinical and Technological Interventions: Protocol for a Single-Arm Pilot Trial. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2025, 14, e62916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, M.; Bodenhofer, J.; Fischill-Neudeck, M.; Roth, C.; Domhardt, M.; Emsenhuber, G.; Grabner, B.; Oostingh, G.J.; Schuster, A. Comparison of the Efficacy of Type 2 Diabetes Group Training Courses With and Without the Integration of mHealth Support in a Controlled Trial Setting: Results of a Comparative Pilot Study. Diabetes Spectr. 2024, 38, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Advisors Available online: https://diabetes.med.umich.edu/about/advisors#patient-family-advisory-council-pfac.

- Person-Centered Care Available online:. Available online: https://www.cms.gov/priorities/innovation/key-concepts/person-centered-care (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- van der Feltz-Cornelis, C.M.; Nuyen, J.; Stoop, C.; Chan, J.; Jacobson, A.M.; Katon, W.; Snoek, F.; Sartorius, N. Effect of Interventions for Major Depressive Disorder and Significant Depressive Symptoms in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2010, 32, 380–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, E.B.; Chan, J.C.N.; Nan, H.; Sartorius, N.; Oldenburg, B. Co-Occurrence of Diabetes and Depression: Conceptual Considerations for an Emerging Global Health Challenge. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 142, S56–S66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, P.E.; Fournier, A.-A.; Sisitsky, T.; Simes, M.; Berman, R.; Koenigsberg, S.H.; Kessler, R.C. The Economic Burden of Adults with Major Depressive Disorder in the United States (2010 and 2018). PharmacoEconomics 2021, 39, 653–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavelaars, R.; Ward, H. ; Mackie, deMauri S. ; Modi, K.M.; Mohandas, A. The Burden of Anxiety among a Nationally Representative US Adult Population. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 336, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Anxiety only (N=13) |

Depression and anxiety (N=33) |

Depression only (N=50) |

Neither (N=433) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHQ-9 score | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 9.25 (4.43) | 20.1 (2.69) | 17.8 (2.52) | 5.43 (4.12) |

| Missing | 9 (69.2%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 24 (5.5%) |

| PAID-11 score | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 22.6 (10.8) | 25.6 (10.1) | 21.1 (9.24) | 9.33 (8.16) |

| Missing | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.0%) | 9 (2.1%) |

| GAD-7 score | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 18.0 (2.00) | 17.7 (2.05) | 9.54 (3.28) | 3.46 (3.56) |

| Missing | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (8.0%) | 10 (2.3%) |

| Diabetes type | ||||

| Type 1/Type 1.5 | 8 (61.5%) | 17 (51.5%) | 31 (62.0%) | 216 (49.9%) |

| Type 2 | 5 (38.5%) | 15 (45.5%) | 18 (36.0%) | 192 (44.3%) |

| Gestational (past or current) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.0%) | 0 (0%) | 21 (4.8%) |

| Diabetes - Type Unknown | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.0%) | 4 (0.9%) |

| Latest HbA1c value | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 7.59 (1.36) | 7.93 (1.72) | 7.40 (1.69) | 6.96 (1.27) |

| Missing | 1 (7.7%) | 9 (27.3%) | 3 (6.0%) | 57 (13.2%) |

| Current age | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 46.8 (15.8) | 41.0 (13.5) | 49.2 (14.5) | 55.9 (17.0) |

| Gender | ||||

| Man | 3 (23.1%) | 5 (15.2%) | 12 (24.0%) | 170 (39.3%) |

| Woman | 8 (61.5%) | 26 (78.8%) | 34 (68.0%) | 239 (55.2%) |

| Gender non-conforming | 0 (0%) | 2 (6.1%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (0.5%) |

| Missing | 2 (15.4%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (8.0%) | 22 (5.1%) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Native American or Alaskan Native | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.0%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (0.7%) |

| Asian | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 15 (3.5%) |

| Black or African American | 1 (7.7%) | 3 (9.1%) | 3 (6.0%) | 41 (9.5%) |

| Latino | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.0%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (1.8%) |

| White | 8 (61.5%) | 26 (78.8%) | 41 (82.0%) | 326 (75.3%) |

| Prefer not to Disclose | 4 (30.8%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (10.0%) | 32 (7.4%) |

| More than one race | 0 (0%) | 2 (6.1%) | 1 (2.0%) | 8 (1.8%) |

| Highest grade of school | ||||

| High school diploma or below | 2 (15.4%) | 9 (27.3%) | 9 (18.0%) | 80 (18.5%) |

| Associate’s degree or certificate program | 5 (38.5%) | 8 (24.2%) | 11 (22.0%) | 63 (14.5%) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 3 (23.1%) | 7 (21.2%) | 17 (34.0%) | 131 (30.3%) |

| Advanced degree | 3 (23.1%) | 9 (27.3%) | 13 (26.0%) | 159 (36.7%) |

| Annual household income | ||||

| Less than $50,000 | 7 (53.8%) | 18 (54.5%) | 24 (48.0%) | 113 (26.1%) |

| $50,000-$99,999 | 3 (23.1%) | 5 (15.2%) | 12 (24.0%) | 150 (34.6%) |

| $100,000-$149,999 | 2 (15.4%) | 5 (15.2%) | 7 (14.0%) | 73 (16.9%) |

| $150,000 or more | 1 (7.7%) | 5 (15.2%) | 7 (14.0%) | 87 (20.1%) |

| Missing | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 10 (2.3%) |

| Behavioral or mental health treatment in past 12 months | ||||

| Yes | 9 (69.2%) | 24 (72.7%) | 35 (70.0%) | 132 (30.5%) |

| No | 4 (30.8%) | 9 (27.3%) | 15 (30.0%) | 289 (66.7%) |

| Missing | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 12 (2.8%) |

| Take prescription medication for mental/emotional condition in the past 12 months | ||||

| Yes | 7 (53.8%) | 25 (75.8%) | 34 (68.0%) | 126 (29.1%) |

| No | 6 (46.2%) | 7 (21.2%) | 15 (30.0%) | 294 (67.9%) |

| Missing | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.0%) | 1 (2.0%) | 13 (3.0%) |

| Any mental health treatment or prescription medication use for mental health condition in last 12 months | ||||

| Yes | 9 (69.2%) | 26 (78.8%) | 38 (76.0%) | 165 (38.1%) |

| No | 4 (30.8%) | 7 (21.2%) | 12 (24.0%) | 266 (61.4%) |

| Missing | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (0.5%) |

| Characteristic | N | OR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 153 | 1.80 | 0.29, 11.7 | 0.5 |

| Diabetes type | 153 | |||

| Type 2 | — | — | ||

| Type 1/Type 1.5 | 1.24 | 0.53, 2.90 | 0.6 | |

| Current age | 153 | 1.00 | 0.97, 1.03 | >0.9 |

| Annual household income | 153 | |||

| Less than $50,000 | — | — | ||

| $50,000-$99,999 | 0.57 | 0.23, 1.39 | 0.2 | |

| $100,000-$149,999 | 0.40 | 0.14, 1.17 | 0.10 | |

| $150,000 or more | 1.02 | 0.30, 3.87 | >0.9 | |

| Gender | 153 | |||

| Man | — | — | ||

| Woman | 2.43 | 1.11, 5.40 | 0.027 | |

| Highest grade of school | 153 | |||

| High school diploma or below | — | — | ||

| Associate’s degree or certificate program | 0.61 | 0.20, 1.79 | 0.4 | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 0.73 | 0.26, 2.03 | 0.6 | |

| Advanced degree | 1.09 | 0.36, 3.26 | 0.9 | |

| Race/ethnicity | 153 | |||

| White | — | — | ||

| Black or African American | 0.24 | 0.07, 0.77 | 0.018 | |

| Another race | 1.28 | 0.37, 5.19 | 0.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).