Introduction

Mammalian sperm-associated antigen 6 (SPAG6) is the orthologue of Chlamydomonas PF16, a protein localized in the central pair of the axoneme that modulates flagellar motility [

1]. Human

SPAG6 was cloned by screening a human cDNA library using serum from a patient whose blood was enriched with sperm antibodies [

2]. In humans,

SPAG6 gene is closely related to the progression of many cancers. For example, it is upregulated in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) and MDS-transformed AML [

3,

4,

5,

6] and is involved in the progression of Burkitt lymphoma [

7], non-small-cell lung cancer, etc [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. Mutations in human

SPAG6 cause sperm with multiple flagellar malformations and infertility[

14].

Mice have two

Spag6 genes. One is the ancient

Spag6, located on chromosome 2; the other one is an evolved gene called

Spag6-like (

Spag6l), located on chromosome 16 [

15,

16]. The mouse

Spag6 and

Spag6l genes have different expression patterns. The ancient

Spag6 gene is expressed in the tissues with motile cilia, including brain and testes, while

Spag6l is widely expressed [

16]. Even though the two SPAG6 proteins share a high identity in amino acid sequences, they perform different functions. No major phenotype was discovered in the global

Spag6 knockout mice [

16]; however, the global

Spag6l knockout mice developed significant phenotypes. More than 50% of the global

Spag6l knockout mice died of hydrocephalus before adulthood, and the surviving males were infertile due to malfunction of the motile cilia in early generations [

17]. The

Spag6l knockout mice not only showed defects in cilia motility, but multiple unexpected phenotypes unrelated to the cilia motility were discovered. Ciliogenesis and ciliary polarity were disrupted in the epithelial cells of the brain ventricles, trachea, middle ear, and eustachian tube in the absence of SPAG6L [

18,

19]. In addition, it is also involved in regulating cell proliferation, migration, division, and primary ciliogenesis of mouse embryonic fibroblasts [

20]. SPAG6L not only plays a role in the cells with primary cilia and motile cilia, it also plays a role in the cells without cilia. The immunological synapse is impaired in the immune cells of SPAG6L deficient mice [

21].

Sperm flagella have special motile cilia. The impaired sperm motility contributes to the male infertility phenotype in the absence of SPAG6L [

17]. Spermatogenesis defect is another factor that causes male infertility [

22]. The global

Spag6l knockout mice not only showed reduced sperm motility, but sperm number was also significantly reduced. The ultrastructure of sperm in the testis and epididymis was disrupted, manifested by frequent loss of sperm heads and disordered flagellum structure, including the loss of a central pair of microtubules and the disorder of the outer dense fibers and fibrous sheaths [

17].

Given that

Spag6l is ubiquitously expressed, and it plays multiple roles in vivo, we wish to further explore the mechanisms. However, even though half of the homozygous mice survived to adulthood in the early generations, all died at about three weeks after birth thereafter; we therefore generated the

Spag6lflox/flox mouse model. To test the model, the floxed mice were crossed to the

Hrpt-cre mice so that the

Spag6l was disrupted globally. The phenotype of the homozygous mutant mice was consistent with the global

Spag6l knockout mice [

23].

Both SPAG6 and SPAG6L proteins are present in the subset of microtubules in the transfected mammalian cells [

16]. SPAG6L plays a key role in modulating tubulin acetylation level [

20], and tubulin acetylation is a key factor for microtubule/cytoskeleton functions [

24]. In the global

Spag6l knockout mice, spermatogenesis was affected. Spermatogenesis occurs in the testis consisting of germ cells and somatic cells. Even though germ cells are the sperm-making cells, somatic cells, including the Sertoli cells and Leydig cells, also regulate the spermatogenesis process [

25,

26].

Sertoli cells, also known as nurse cells, are the only somatic cells in the seminiferous epithelium. They provide structural support and an immune barrier to germ cells and are involved in various steps of spermatogenesis. They also secrete products to nourish germ cells while engulfing apoptotic germ cells and excess cytoplasm during their development, thereby maintaining the stability of the spermatogenic microenvironment [

25,

27,

28,

29]. Sertoli cells have a large cytoplasm and a well-developed microtubule transport network [

30]. We were interested to know if SPAG6L plays a role in spermatogenesis through modulating Sertoli cell function. The floxed

Spag6l mice were then crossed to Amh (anti-Müllerian hormone)-Cre mice to specifically inactivate the

Spag6l in Sertoli cells. Surprisingly, even though

Spag6l is expressed in Sertoli cells, the Sertoli cell

Spag6l knockout mice did not show major spermatogenesis defects. These results indicate that inactivation of SPAG6L only in the Sertoli cells does not affect spermatogenesis and male infertility. It is possible that SPAG6, even though low in abundance in the Sertoli cells, compensates for the loss of SPAG6L.

Materials and Methods

Guidelines of the Wayne State University Institutional Animal Care with the Program Advisory Committee (Protocol number: 24-02-6561) were observed in the execution of all animal research.

Sertoli cell line MSC-1 was kindly provided by Dr. Jannette Dufour. It has been shown that the MSC-1 cell line is composed of a single cell type displaying numerous characteristics of Sertoli cells [

31]. MSC-1 cells were cultured in Dulbecco modified eagle medium (DMEM) (Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, MD) supplemented with penicillin-streptomycin and 5% fetal calf serum (FCS) at 37ºC in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO

2/95% air (v/v).

The

Amh-cre line, originally generated by Dr. Florian Guillou [

32], was kindly provided by Dr. William Walker at the University of Pittsburgh. The floxed

Spag6l line was generated in our laboratory. Genomic DNA was extracted from the toes of 7-day-old mice. Mouse genotypes were identified by PCR using the following primers:

Amh-cre forward: 5’-GCATTACCGGTCGATGCAACGAGTG-3’;

Amh-cre reverse:5’-GAACGTAGAGCCTGT TTTGCACGTTC-3’;

Spag6l forward: 5’-CTGTGGCATAGTTGTGGGTTTGAAG-3’;

Spag6l reverse: 5’-CAGCAGAGCCTGTAGCTCTACTC-3’.

Total RNA was extracted from Sertoli cells and mouse testes using TRIzol (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA). cDNA was synthesized by reverse transcription using a cDNA synthesis kit (Meridian Bioscience, Cincinnati, OH). RT-PCR was performed with cDNA as a template using the following specific primers: Spag6 forward: 5’-CCATCACAAACACGTTGCCCGT-3’; Spag6 reverse: 5’-GTTAATAAGAGGCTGATAGCTG-3; Spag6l forward: 5’-GTGGCTGTCACAAACACGCTGC-3’; Spag6l reverse: 5’- CAGTGGTTGGTAGCTGTCCACC-3’.

Mouse testicular and epididymal tissues were collected and then fixed overnight using Bouin’s solution (SIGMA, HT10132). The tissues were then embedded in paraffin, and 5-micron paraffin sections were prepared. After removing the paraffin, standard hematoxylin-eosin staining (H&E) and Periodic Acid-Schiff (PAS) stains were used for histological analysis. The sections were mounted with neutral gum and then photographed.

2-month-old and 5-month-old cKO male mice and control mice were bred independently with 2-5-month-old WT female mice for one month, and vaginal plugs were recorded to verify the occurrence of mating. The number and survival of offspring were also recorded, and the average number of litters was used to describe the fertility situation.

After the testes were collected, they were immediately fixed in 4% Formalin overnight and then embedded in paraffin. 5-micron sections were prepared using a Leica paraffin slicer, then dewaxed and boiled in 10 mM Tris-EDTA (pH = 9.0) or 10 mM sodium citrate (pH 6.0) for 30 minutes for antigen retrieval. Then, the sections were blocked by 10% goat serum at room temperature for one hour, followed by overnight incubation with the corresponding primary antibodies. The next day, PBS was used to wash away the excess primary antibodies, followed by incubation with the secondary antibodies at room temperature for one hour. For PNA staining, following blocking with 10% (v/v) goat serum, samples were incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated PNA (1:4000 dilution in 10% goat serum) for 1 hour at room temperature under light-protected conditions. After washing away the excess secondary antibodies (or PNA) with PBS, a mounting medium containing DAPI nuclear dye was added, and images were taken using a fluorescence microscope. The antibodies or dye used in this study are as follows: WT1 (Proteintech,12609-1-AP, Dilution ratio: 1:200); DDX4 (Abcam, ab27591, Dilution ratio: 1:400); ZO-1 (Thermofisher, 33-9100, Dilution ratio: 1:200); CONNEXTIN-43 (Cell Signaling Technology, 3512S, Dilution ratio: 1:200); PNA-488 (Thermo Scientific, P5767580, Dilution ratio: 1:4000); Goat Anti-Mouse IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor® 488) (Abcam, ab150113, Dilution ratio: 1:2000); Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor® 555) (Abcam, ab150078, Dilution ratio: 1:2000); DAPI (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA, USA); Phalloidin (Thermo Scientific, A12379).

ImageJ was used to analyze the images to count the number of Sertoli cells and germ cells. To count the cell numbers of the seminiferous tubule, at least 20 tubules were analyzed for each testis per mouse.

The cauda epididymis was promptly removed and immersed in PBS solution maintained at 37°C. The tissue was then incised, allowing the spermatozoa to disperse. Following this, a tenfold dilution of the sample was prepared, and the diluted sample was carefully dispensed onto a cell counting plate for enumeration. Sperm concentration was calculated using the formula: (number of sperm counted / volume of diluted sample) × dilution factor.

Testes were aseptically dissected from mice, and the tunica albuginea was removed. Seminiferous tubules were enzymatically digested in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 2 mg/mL collagenase, 20 μg/mL DNase I, and 2 mg/mL hyaluronidase (all from Sigma) at 37°C for 30 min to generate a single-cell suspension. The suspension was filtered through a 70-μm cell strainer (Falcon) to remove undigested tissue fragments. Cell density was quantified using a hemocytometer, and cells were seeded at 50,000 cells/cm² in DMEM/F12 medium (Gibco) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; HyClone) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Thermo Fisher). Cultures were maintained in a humidified incubator at 35°C with 5% CO₂ for 72 hr. On day 4, adherent Sertoli cell monolayers were washed twice with PBS, followed by hypotonic treatment with 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5; MilliporeSigma) at room temperature for 5 min to selectively remove residual germ cells. Isotonicity was immediately restored using fresh medium replacement, and purified Sertoli cells were further cultured for downstream applications. Sertoli cells were plated on 8-well chamber slides (Thermo Scientific Nunc™) pre-coated for immunofluorescence assays. After removing the culture medium, cells were washed twice with PBS. Fixation was performed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA; Sigma-Aldrich) at room temperature (RT) for 15 min, followed by two additional PBS washes. Cellular permeabilization was achieved using 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS for 15 min at RT. Post-permeabilization washes (×2 PBS) preceded incubation with Alexa Fluor™ 488-conjugated phalloidin (1:40 dilution in 1% BSA/PBS; Invitrogen) for 1 hr at RT under light-protected conditions. Following final PBS washes (×2), nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (Vector Labs) and imaged on a Nikon DS-Fi2 Eclipse 90i Motorized Upright Fluorescence Microscope (The C.S. Mott Center for Human Growth and Development, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Wayne State University).

Statistical analyses were performed using Student’s t test. *p < 0.05 was considered as significant. Graphs were created using Microsoft Excel and GraphPad Prism.

Results

The MSC-1 cell line is a Sertoli cell line derived from transgenic mice carrying a fusion gene construct comprising the human Anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) transcriptional regulatory sequence fused to the SV40 T-antigen gene [

33]. This cell line has been used by many researchers as an in vitro model of Sertoli cells [

34,

35]. Total RNA was isolated from MSC-1 cells using TRIzol reagent, followed by reverse transcription into cDNA. RT-PCR analysis revealed high-level expression of both

Spag6 and

Spag6l in the MSC-1 cell line (

Supplemental Figure S1A), with testicular cDNA serving as a positive control.

Using CRISPR/Cas9 technology, we inserted LoxP sites flanking exon 3 of the

Spag6l gene [

23]. Subsequent breeding of LoxP-modified mice with

Amh-Cre transgenic mice enabled Cre recombinase-mediated excision of exon 3 between the paired LoxP sites, generating a conditional knockout allele specifically in Sertoli cells (

Supplemental Figure S1B). Genotyping analysis confirmed the

Spag6lflox/flox homozygous and

Spag6lflox/+ heterozygous genotypes, as shown in

Supplemental Figure S1C. The

Spag6lflox/flox;Amh-Cre+ mice were considered to be homozygous conditional knockout (cKO) mice, and the

Spag6lflox/+;Amh-Cre+ or

Spag6lflox/flox;Amh-Cre- mice were analyzed as the controls.

cKO mice exhibited no overt phenotypic differences compared to WT controls, including body weight and developmental progression. To investigate whether Sertoli cell-specific deletion of

Spag6l impacts male fertility, 2 and 5-month-old cKO males underwent monthly fertility assessments over a 3-month breeding trial. Surprisingly, all experimental cohorts demonstrated reproductive competence equivalent to controls, with no statistically significant differences in mean litter size per mating pair (P > 0.05,

Figure 1).

As Sertoli cells are pivotal regulators of testicular morphogenesis, we systematically evaluated whether Sertoli cell-specific deletion of

Spag6l compromises testicular functionality. Comparative analyses of age-matched cKO and WT littermates revealed no significant differences in testis/body weight ratio (

Figure 2A,B), indicating preserved testicular development despite

Spag6l deletion. Subsequently, cauda epididymal spermatozoa were collected from sexually mature cKO males (n=5/group) for quantitative assessment. Quantification using a hemocytometer demonstrated comparable sperm counts between genotypes (

Figure 2C,D). These findings collectively suggest that Sertoli cell-specific

Spag6l deficiency does not overtly impair spermatogenic output.

The principal function of the reproductive system resides in the generation of germ cells. Sertoli cells play an essential role in the regulation of spermatogenesis [

29]. Henceforth, we scrutinized the process of spermatogenesis within the testicular tissue. Briefly, histological sections of adult testes and epididymides were meticulously prepared and examined. In the testicular tissue of cKO mice, distinct phases of the 12-stage seminiferous epithelial cycle and the 16-step spermiogenesis process were unequivocally discernible (

Figure 3A,B, and

Supplemental Figure S2). Furthermore, H&E staining of the epididymal sections revealed a substantial aggregation of mature spermatozoa within the lumen (

Figure 3C). These results indicate that deletion of

Spag6l in Sertoli cells may not affect the normal spermatogenesis process.

To investigate potential alterations in testicular cellular composition induced by

Spag6l deficiency, we conducted immunofluorescence characterization of germ cell and Sertoli cell populations within seminiferous tubules. Germ cells were identified using the meiotic marker DDX4 (cytoplasmic localization in spermatogonia, spermatocytes, and round spermatids), while Sertoli cells were distinguished by WT1 nuclear staining. Quantitative analysis of cross-sectional tubule profiles revealed comparable germ cell populations between genotypes, with cKO mice showing no statistically significant changes in the mean number of DDX4

+ cells per tubular lumen cross-section (

Figure 4A). Similarly, WT1

+ Sertoli cells maintained their characteristic basal compartment localization in cKO testes, with cell counts remaining comparable to WT controls (

Figure 4B).

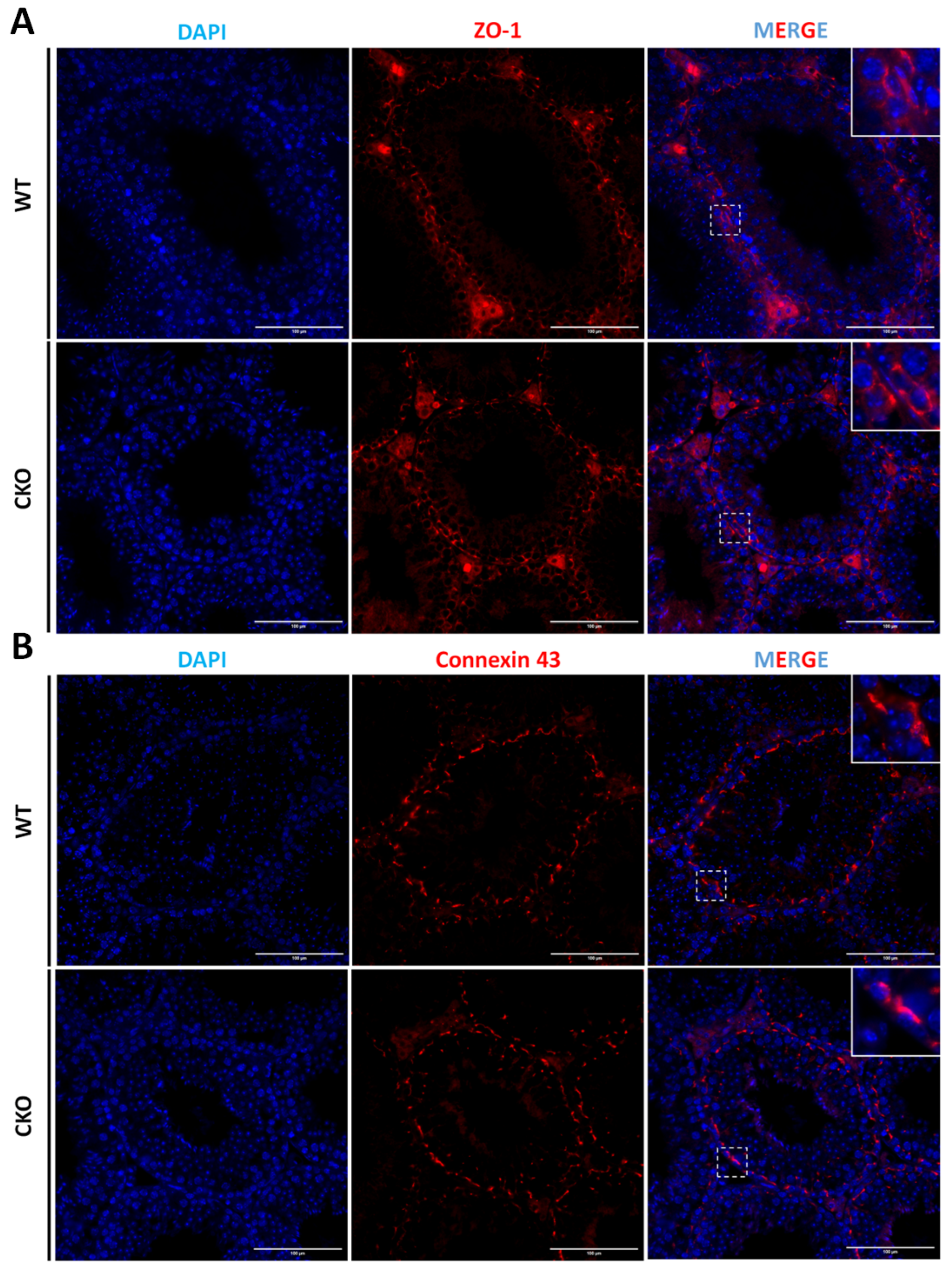

Within the seminiferous tubules, Sertoli cells play a pivotal role in establishing the essential blood-testis barrier (BTB). Hence, we employed antibodies against ZO-1 and Connexin-43 to delineate two crucial intercellular junction types within the BTB, namely tight junctions (TJ) and gap junctions (GJ). Our observations revealed that the distribution and integrity of these junctions remained unaffected when

Spag6l was disrupted in the Sertoli cells (

Figure 5).

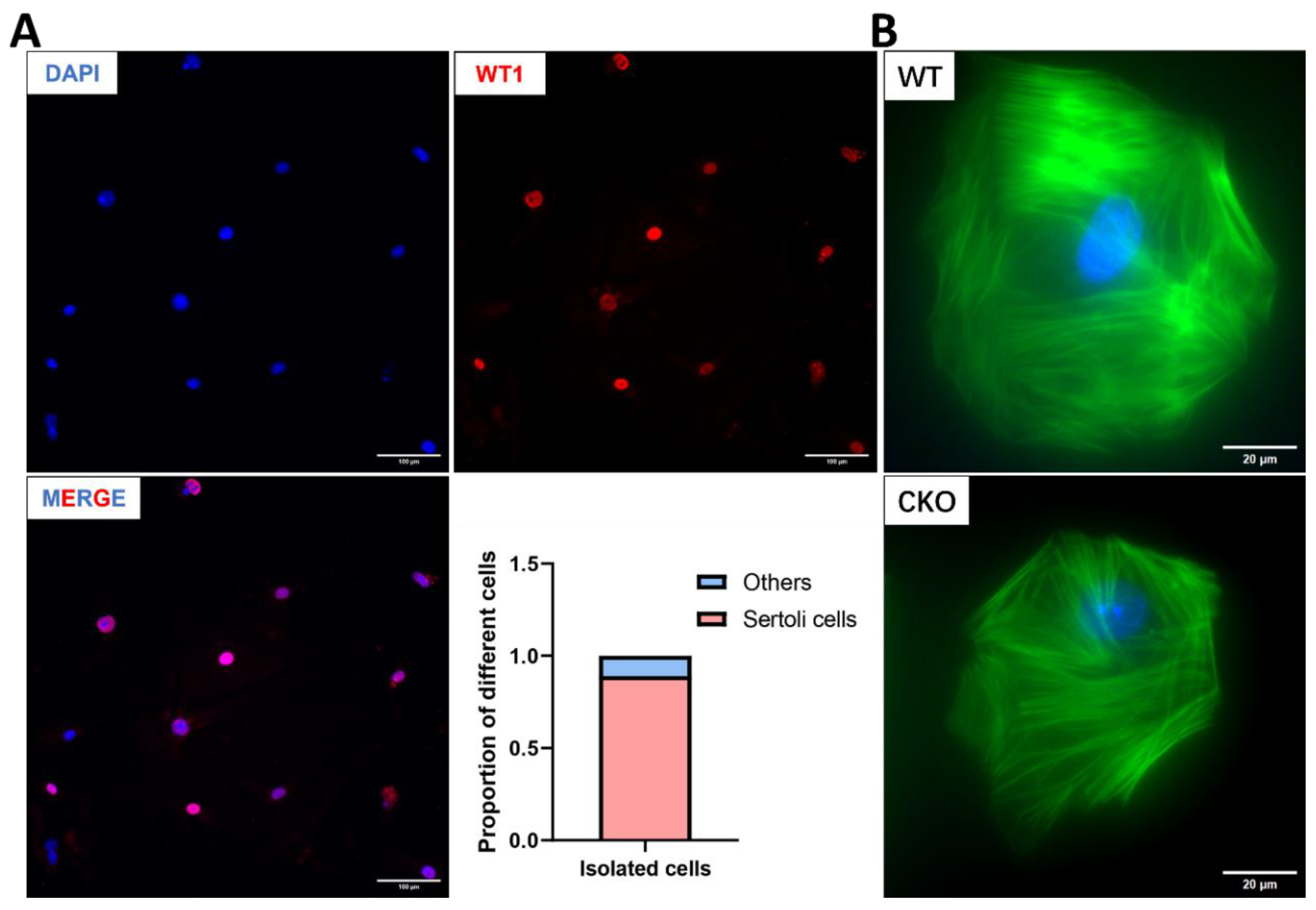

As a crucial structural element of the Sertoli cell cytoskeleton, F-actin plays a pivotal role in preserving BTB integrity. The actin-based microfilament network not only encapsulates developing germ cells to facilitate their directional migration through seminiferous tubules, but also coordinates with gap junctions, adherens junctions, and other intercellular connectors to mediate Sertoli-germ cell communication [

30,

36]. To investigate potential

Spag6l deficiency-induced alterations in Sertoli cell F-actin organization, we performed primary Sertoli cell isolation from WT and cKO mouse testes (

Figure 6A). Cellular purity was confirmed through WT1 nuclear immunostaining, while phalloidin staining revealed F-actin cytoskeletal architecture. Notably, comparative analysis demonstrated no significant differences in F-actin organization between WT and cKO Sertoli cells (

Figure 6B).

Discussion

Mouse SPAG6L is a protein evolved from SPAG6. SPAG6L not only conducts the conserved function as a central apparatus protein to control cilia motility, but also plays an essential role in cilia formation. In global

Spag6l knockout mouse models that survived to adulthood, infertility emerges as the cardinal phenotypic manifestation, attributable to asthenozoospermia with structural flagellar abnormalities[

17]. Furthermore,

Spag6l deficiency disrupts ciliary motility through randomized axonemal orientation and compromised basal body polarity in both respiratory (tracheal) and auditory (middle ear) epithelia [

18,

19]. During evolution, SPAG16L gains new functions, and we believe that the key mechanism is to modulate microtubule/cytoskeleton functions by regulating tubulin acetylation levels [

37]. Our ectopic expression studies revealed partial colocalization of both SPAG6 and SPAG6L with α-tubulin networks, indicative of their potential participation in cytoskeletal modulation [

16]. Complementing these findings, comparative analysis of

Spag6-deficient versus WT mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) demonstrated

Spag6-deficient MEFs also showed reduced adhesion associated with a non-polarized F-actin distribution. Furthermore, cells overexpressing SPAG6L showed stronger staining for acetylated tubulin, and SPAG6L and acetylated tubulin were completely colocalized [

20]. These data collectively suggest an evolutionarily conserved role for the SPAG6 family proteins in cytoskeletal architecture regulation. Microtubules are dynamic structures involved in the function of Sertoli cells, providing tracks for the movement of germ cells/sperm cells. They must be strictly regulated to function normally [

38], while actin-based TJ and GJ together with intermediate filament-based desmosomes constitute the BTB [

39,

40,

41], which play an indispensable role in maintaining the stability of the internal environment of spermatogenesis and the migration of germ cells to the center of the seminiferous tubule. Previous studies in pigs have suggested the presence of primary cilia on immature Sertoli cells [

42]. However, it remains challenging to observe typical cilia on adult Sertoli cells in most cases. Sertoli cells have a large number of microvilli, which play an irreplaceable role in signal transmission and connection with germ cells [

36]. Considering our previous research results [

20], we believe that SPAG6L may have an important regulatory function in regulating the dynamic process of the Sertoli cytoskeleton.

However, systematic phenotyping reveals that

Spag6l ablation does not exert significant detrimental effects on Sertoli cell functional homeostasis during the first 6 postnatal months. cKO mice exhibited normal fertility, with no significant differences in litter size or sperm concentration. Histological evaluation via periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining further confirmed intact seminiferous epithelial architecture at all stages of the spermatogenic cycle of cKO mice. Immunofluorescence revealed conserved germ cell and Sertoli cell populations within seminiferous tubules of cKO mice, also demonstrating the location of gap junction protein Connexin 43 and tight junction-associated protein ZO-1, indicating intact Sertoli cell junctional functionality. Furthermore, phalloidin-based F-actin visualization in isolated Sertoli cells showed conserved cytoskeletal architecture, with filament orientation indistinguishable from controls. The lack of observable phenotypes in our study could arise from two compensatory mechanisms: (1) the inherent absence of ciliary architecture in terminally differentiated Sertoli cells, which minimizes dependency on SPAG6L, and (2) functional redundancy provided by persistent SPAG6 expression (93% sequence homology with SPAG6L in mouse models). Our initial experimental strategy sought to delineate the differential expression profiles of SPAG6 and SPAG6L through immunofluorescence microscopy or immunoblotting assays. However, this endeavor encountered formidable technical challenges due to the unavailability of high-specificity commercial antibodies capable of distinguishing them [

42,

43]. Despite generating six distinct polyclonal antibodies targeting divergent epitopes, there is insufficient specificity for unambiguous discrimination. These technical limitations currently preclude definitive subcellular localization analysis of SPAG6L in Sertoli cells. Nevertheless, our results suggest that the loss of

Spag6l in Sertoli cells alone does not significantly affect normal spermatogenesis in mice, at least before 6 months of age, which is an important supplement to our study of the functions of

Spag6 and

Spag6l in the mammalian reproductive system.

Given that

Spag6-/- has been reported to generate no obvious abnormalities in multiple systems, including the reproductive system [

16], it may be important to further study the functions of these two

Spag6 genes in Sertoli cells. A potential solution is to cross existing

Spag6-/- mice with our

Spag6lflox/flox; Amh-Cre

+ line to generate triple-transgenic

Spag6-/-;

Spag6lflox/flox; Amh-Cre

+ animals. This strategy would complete the double knockout of

Spag6 and

Spag6l in Sertoli cells and allow exploration of the synergistic/antagonistic effects of

Spag6 and

Spag6l in Sertoli cells. Alternatively, we recently initiated work to establish a knock-in mouse model, adding HA and V5 tag proteins after SPAG6 and SPAG6L, respectively, which is expected to further reveal the similarities and differences in their expression and localization in Sertoli cells in future studies.

Figure 1.

Spag6l cKO mice were fertile. Longitudinal assessment of male reproductive capacity. Age-stratified cohorts (2 and 5-month-old) of conditional knockout (cKO) and age-matched WT males mice underwent continuous mating trials with proven-fertility WT females. Litter size quantification revealed maintained reproductive performance in cKO mice across both age groups (2-month: WT 6.3 ± 0.6 vs cKO 7.7 ± 1.6 vs; 5-month: WT 7.7 ± 0.6 vs cKO 7.3 ± 1.5, mean ± SD). Statistical analysis by two-tailed unpaired Student's t-test (n = 3 biological replicates per group, ns: P > 0.05).

Figure 1.

Spag6l cKO mice were fertile. Longitudinal assessment of male reproductive capacity. Age-stratified cohorts (2 and 5-month-old) of conditional knockout (cKO) and age-matched WT males mice underwent continuous mating trials with proven-fertility WT females. Litter size quantification revealed maintained reproductive performance in cKO mice across both age groups (2-month: WT 6.3 ± 0.6 vs cKO 7.7 ± 1.6 vs; 5-month: WT 7.7 ± 0.6 vs cKO 7.3 ± 1.5, mean ± SD). Statistical analysis by two-tailed unpaired Student's t-test (n = 3 biological replicates per group, ns: P > 0.05).

Figure 2.

Comprehensive evaluation of testis morphology and spermatogenic capacity. (A) Gross morphological analysis. Comparative visualization of testes and epididymis from 2-month-old cKO mice versus WT littermates. (B) Testis weight index quantification. Combined testicular mass (bilateral, mg/g) normalized to body weight showed comparable ratios between genotypes (WT: 7.32 ± 0.59 vs cKO: 7.62 ± 0.95, mean ± SD). (C) Spermatozoa morphological assessment. Caudal epididymal sperm suspensions obtained through mechanical dissociation in PBS (37°C, 20 min) exhibited normal sperm architecture in both groups (inset: representative contrast micrograph). (D) Sperm counting. Hemocytometric analysis revealed conserved sperm concentrations in cKO mice (WT: 4.77 ± 2.36 ×10⁶/mL vs cKO: 5.39 ± 1.22 ×10⁶/mL). Statistical significance determined by two-tailed unpaired Student's t-test (n = 3 biological replicates, ns: P > 0.05).

Figure 2.

Comprehensive evaluation of testis morphology and spermatogenic capacity. (A) Gross morphological analysis. Comparative visualization of testes and epididymis from 2-month-old cKO mice versus WT littermates. (B) Testis weight index quantification. Combined testicular mass (bilateral, mg/g) normalized to body weight showed comparable ratios between genotypes (WT: 7.32 ± 0.59 vs cKO: 7.62 ± 0.95, mean ± SD). (C) Spermatozoa morphological assessment. Caudal epididymal sperm suspensions obtained through mechanical dissociation in PBS (37°C, 20 min) exhibited normal sperm architecture in both groups (inset: representative contrast micrograph). (D) Sperm counting. Hemocytometric analysis revealed conserved sperm concentrations in cKO mice (WT: 4.77 ± 2.36 ×10⁶/mL vs cKO: 5.39 ± 1.22 ×10⁶/mL). Statistical significance determined by two-tailed unpaired Student's t-test (n = 3 biological replicates, ns: P > 0.05).

Figure 3.

Histomorphometric evaluation of germ cell development and spermatogenic progression. (A) Stage-specific seminiferous epithelium analysis. Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) histochemistry revealed preserved cytoarchitectural organization across all spermatogenic stages (I-XII) in 2-month-old cKO mice, with intact BTB formation and normal germ cell associations. Scale bar: 20μm. (B) Spermiogenesis phase tracking Immunofluorescence demonstrated characteristic 16-step spermatogenic progression, visualized through lectin-based acrosomal tracking (PNA, red) and nuclear demarcation (DAPI, blue). Scale bar: 10μm (C) H&E staining of the caudal epididymis of 2-month-old mice, no significant change in sperm number was found. Scale bar in the corner. Scale bar: 300μm.

Figure 3.

Histomorphometric evaluation of germ cell development and spermatogenic progression. (A) Stage-specific seminiferous epithelium analysis. Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) histochemistry revealed preserved cytoarchitectural organization across all spermatogenic stages (I-XII) in 2-month-old cKO mice, with intact BTB formation and normal germ cell associations. Scale bar: 20μm. (B) Spermiogenesis phase tracking Immunofluorescence demonstrated characteristic 16-step spermatogenic progression, visualized through lectin-based acrosomal tracking (PNA, red) and nuclear demarcation (DAPI, blue). Scale bar: 10μm (C) H&E staining of the caudal epididymis of 2-month-old mice, no significant change in sperm number was found. Scale bar in the corner. Scale bar: 300μm.

Figure 4.

Immunofluorescence showed no obvious changes in germ cells and Sertoli cells. (A) Paraffin section of testis showing the location of germ cells in the seminiferous tubules. Scale bar: 100μm; (B) Average number of germ cells in seminiferous tubules. n=20, WT 140.90±14.86 vs cKO 152.20±16.60; (C) Location of Sertoli cells in seminiferous tubules. Scale bar: 100μm; (D) Average number of Sertoli cells in seminiferous tubules. n=20, WT 20.55±3.53 vs cKO 19.85±2.20; DDX4: germ cell marker, WT1: Sertoli cell marker, DAPI: nuclear marker. Tissue from 2-month-old mouse testes. Statistical significance determined by two-tailed unpaired Student's t-test (n = 3 biological replicates, ns: P > 0.05).

Figure 4.

Immunofluorescence showed no obvious changes in germ cells and Sertoli cells. (A) Paraffin section of testis showing the location of germ cells in the seminiferous tubules. Scale bar: 100μm; (B) Average number of germ cells in seminiferous tubules. n=20, WT 140.90±14.86 vs cKO 152.20±16.60; (C) Location of Sertoli cells in seminiferous tubules. Scale bar: 100μm; (D) Average number of Sertoli cells in seminiferous tubules. n=20, WT 20.55±3.53 vs cKO 19.85±2.20; DDX4: germ cell marker, WT1: Sertoli cell marker, DAPI: nuclear marker. Tissue from 2-month-old mouse testes. Statistical significance determined by two-tailed unpaired Student's t-test (n = 3 biological replicates, ns: P > 0.05).

Figure 5.

Immunofluorescence showed that the structure of testicular BTB was unchanged. (A) ZO-1 was highly enriched in the lateral membrane area (close to the basement membrane) of Sertoli cells in the seminiferous epithelium of cKO mice, and the signal was continuous without abnormal localization, indicating that there was a complete tight junction structure between its Sertoli cells. Scale bar: 100μm; (B) In the seminiferous epithelium of cKO mice, Connexin 43 signals were mainly localized on the basal side, indicating gap junctions formed between Sertoli cells. Connexin 43 signals were also observed in the central area close to the lumen, suggesting the formation of gap junctions between supporting cells and germ cells. The above results were not significantly abnormal with the WT. Scale bar: 100μm. ZO-1: Tight junction-related protein, Connextin-43: Gap junction-related protein. DAPI: nuclear marker.

Figure 5.

Immunofluorescence showed that the structure of testicular BTB was unchanged. (A) ZO-1 was highly enriched in the lateral membrane area (close to the basement membrane) of Sertoli cells in the seminiferous epithelium of cKO mice, and the signal was continuous without abnormal localization, indicating that there was a complete tight junction structure between its Sertoli cells. Scale bar: 100μm; (B) In the seminiferous epithelium of cKO mice, Connexin 43 signals were mainly localized on the basal side, indicating gap junctions formed between Sertoli cells. Connexin 43 signals were also observed in the central area close to the lumen, suggesting the formation of gap junctions between supporting cells and germ cells. The above results were not significantly abnormal with the WT. Scale bar: 100μm. ZO-1: Tight junction-related protein, Connextin-43: Gap junction-related protein. DAPI: nuclear marker.

Figure 6.

Cytoskeletal integrity assessment in isolated Sertoli cells. (A) Validation of cellular purity. WT1 immunostaining (red; Sertoli cell nuclear marker) with DAPI counterstain (blue; pan-nuclear) confirms efficient Sertoli cell isolation. Scale bar: 100μm; (B) Microfilament network analysis. Phalloidin staining (green; F-actin) reveals preserved cytoskeletal architecture in cKO Sertoli cells. DAPI (blue) denotes nuclei. Tissues derived from postnatal day 20 mice. Scale bars: 20μm.

Figure 6.

Cytoskeletal integrity assessment in isolated Sertoli cells. (A) Validation of cellular purity. WT1 immunostaining (red; Sertoli cell nuclear marker) with DAPI counterstain (blue; pan-nuclear) confirms efficient Sertoli cell isolation. Scale bar: 100μm; (B) Microfilament network analysis. Phalloidin staining (green; F-actin) reveals preserved cytoskeletal architecture in cKO Sertoli cells. DAPI (blue) denotes nuclei. Tissues derived from postnatal day 20 mice. Scale bars: 20μm.