1. Introduction

The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic caused a devastating effect and crisis in societies across the globe (Nicola et al., 2020; Schnitzler et al., 2021; Alizadeh et al., 2023). World Health Organization (2022) reported about 465 million cases of COVID-19 infections, almost 6 million deaths, and 365 million recoveries. In addition to the negative health impact, the COVID-19 pandemic also caused economic distress (Arndt et al., 2020; Khowa et al., 2022), exacerbated the plight of vulnerable populations (Kithiia et al., 2020; Sumner et al., 2020) and compounded food security issues and instability of informal sector (Ngcamu & Mantraris, 2021). International Labour Organization (2021) noted that an estimated 255 million full-time jobs vanished across the world due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, it negatively impacted the lifestyles, well-being, and community support structures (Coller & Webber, 2020; Giuntellaa et al., 2021). In May 2023, the World Health Organization (2023) advised that despite the persistently high level of global risk assessment, there is a decrease in risks to human health, primarily attributable to the prevalence of population-level immunity resulting from prior infections. As such, the COVID-19 pandemic no longer meets the criteria for a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC). Despite this, researchers caution that the incidence of zoonotic diseases, which are transmissible from animals to humans, and others such as pandemic influenza are increasing, with the likelihood of a novel pandemic outbreak elevated beyond historical levels (European Commission, 2021; Bai, 2022; Fauci et al., 2023). Aligned with this potential upcoming challenge, the Director of the World Health Organization advised that “in the face of overlapping and converging crises, pandemics are far from the only threat we face, when the next pandemic comes knocking – and it will – we must be ready to answer decisively, collectively, and equitably” (United Nations, 2023).

The pandemic's deleterious consequences necessitated that governments assume an interventionist role to alleviate the staggering social, health, and economic ramifications of the COVID-19 lockdown on sustainable development (Khambule, 2021). Despite this, most of the studies on the socio-economic impact of COVID-19 focused on the macro levels (Chitiga-Mabugu et al., 2021; Padhan & Prabheesh, 2021; Khambule, 2021), with very few using the lenses of the affected individuals in the communities. The few that focused on individuals zoomed in on the health aspects of COVID-19 (Parsons Leigh et al., 2020; Folayan et al., 2023), on practitioners (Ashcroft et al., 2021; de Koning et al., 2021; Clay et al., 2022; Aftab, 2023) or educational or work tools (Radu et al., 2020; Moens et al., 2021; Tran et al., 2021). Furthermore, most studies on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on socio-economic studies mainly focused on one or two socio-economic dimensions and not more comprehensive multiple dimensions. For example, there are studies that focused on the impact of COVID-19 or the impact of its associated regulation analysed the well-being only (Wang et al., 2020; Newson et al., 2021; Nikolaidis et al., 2021), income and expenditure with financial inflows only (Rönkkö et al., 2022), poverty and food insecurity only (Headey et al., 2022) and income and livelihood (Schotte & Zizzamia, 2022). This study analysed holistic socio-economic dimensions, which include employment, poverty, life quality, health and well-being, and family and social support. This study is crucial to enhance the knowledge to draw some lessons from and improve the future readiness of the countries, especially the developing countries, in major disruptions such as pandemics or other major events. Fauci et al. (2023, p.1) highlight the importance of lessons highlighting, amongst others, “Early, rapid, and aggressive action is critical in implementing public health interventions and countermeasure development.” As such, the overarching question of this research is: How has the government’s fiscal support intervention impacted the effects of health regulations on socio-economic dimensions in South Africa during the COVID-19 pandemic? The rest of the paper is comprised of the following sections. It starts with the theoretical foundation that underpins the study, followed by hypothesis development. This is followed by the methodology applied, the results, and then a discussion. The paper closes by providing conclusions which include implications, limitations, and suggestions for future research.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Crisis and Intervention Theories

A crisis can have multiple effects on society. COVID-19 was a crisis that caused health devastations and economic distress (Arias-Maldonado, 2020; Shang et al., 2021; Chitiga-Mabugu et al., 2021). The emergence of different outcomes during a crisis is contingent upon the characteristics of the system experiencing the crisis and its interactions with other systems. Applying the crisis theory to COVID-19 entails analysing its definition, societal implications, impact, and the intricate systems involved (Walby, 2022). Central to the theory of crisis is the concern about the dichotomy between reality and social construction, as well as their potential interplay, of which the reality is evident with COVID-19 with the level of health crisis (World Health Organization, 2022), increased poverty (World Bank, 2020) large scale job losses. COVID-19 pandemic also resulted in increased mental health concerns, which resulted from extreme levels of grief and loss, extended periods of isolation, unresolved pain, and fatigue (Mendelsohn et al., 2022), on-going anxiety and depression from lost sources of income and COVID-19 induces chronic health concerns (John Hopkins Medicine, 2022).

Crises like the COVID-19 pandemic necessitate prompt action from leaders (Bricka, 2022). Weiss (2000) explained that after an issue has been recognised - crisis, a desired outcome specified, and the stakeholders whose actions will determine the outcome have been named, policymakers must determine what the government may do to encourage the actors to alter their actions. An interventionist's strategy for exerting influence. A theory of intervention requires the specification of who should intervene, the target of whom should be influenced, the mechanism of how to intervene, and when and where a concrete social intervention should occur (Hankonen, 2013). A wide variety of governmental interventions in a society can range from policy, programmes, directives, guidelines, and by-laws (Vermeulen & Kok, 2012). Koehler and Chopra (2014) explained that the extent and scope of interventions should be considered in light of the specific nature of the state. This can include direct and indirect interventions which can range from strong prescriptive interventions to weak interventions involving guiding, facilitating, and encouraging approaches (Van der Waldt, 2015). In response to the unprecedented impact of the COVID-19 the governments around the world intervened with emergency health regulations This was critical as COVID-19 threatened health systems and citizen’s life in the countries (Warah, 2021). The emergency health regulation intervention to safeguard the lives had a domino effect resulting in negative socio-economic impacts (Vilakati; 2021) propelling governments to also implement economic interventions. The complexity of the COVID-19 pandemic thus brings to forth the need to understand both the crisis and intervention bringing a crisis-intervention perspective.

2.2. Limitation of Focus of COVID-19 as Health Crisis Only

Government around the world invoked emergency regulations to curb the spread of COVID-19 pandemic (Chung et al., 2021; Mtotywa & Mtotywa, 2022) through controlling the disease and flattening the curve (Rawson et al., 2020) using multiple non-pharmaceutical interventions (Haug et al., 2020; Susič, et al., 2022). This resulted in measures such as nationwide lockdowns, travel limitations and curfews, border closure, mandatory wearing of the masks among other actions (Ferhani & Rushton, 2020; Won et al., 2022). Other interventions included nation-wide testing and tracing of exposure to quarantine and minimise the spread of the virus. To ensure compliance, some of the countries like South Africa deployed military forces to support the police in enforcing the mandated lockdown (Dukhi et al., 2021). Ferhani and Rushton (2020) posit that governments worldwide have progressively recognised pandemics as not only public health concerns, but also as dangers to national security. As such, several countries integrated disease risks and responses into their national security policies, resulting in security policy communities assuming significant and novel responsibilities in the country's preparations for and management of pandemics. The COVID-19 pandemic disproportionately affected communities because the virus is spreading more rapidly in densely populated areas where there is limited capacity to implement effective measures to control its spread. There are a multitude of socio-economic dimensions that were affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and its subsequent emergency health regulations in South Africa and other countries around the world. These include poverty levels, employment levels, life quality, health and well-being, and family and social support. Quaglia and Verdun (2022) argued that the COVID-19 pandemic commenced as a public health crisis in early 2020, precipitated quick and severe economic repercussions, resulting in the most significant economic recession since World War II, with a global contraction of 3.5 percent in 2020. Despite this, most governments, including South Africa, did not have adequate foresight to treat the COVID-19 pandemic crisis as an integrated health and economic crisis, initially spending a lot of effort treating COVID-19 as only a health crisis. Boin and Rhinard, M. (2022, p. 655) acknowledge that despite European Union's performance on handling COVID-19 was positive it “acted quickly after a somewhat slow start and was very effective in mobilizing a variety of resources” In South African the government announced an economic intervention - fiscal support interventions towards the end of April 2020, a month after the first lockdown. Even after that, the main focus of the advisory bodies was limited to the health imperatives of COVID-19, mainly driven by Department of Health with less to negligible focus on economic impact (Richter & Nokhepheyi, 2024).

2.3. COVID-19 Health Regulations and Socio-Economic Dimensions

Poverty poses a global threat that impacts both rich and developing countries. The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly altered the trajectory of human development. The regions most affected by the pandemic-induced rise in poverty are South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa (Moyer et al., 2022). However, its impact is particularly devastating for sub-Saharan Africa, while also having a catastrophic effect on emerging nations as a whole. The South African statistics experienced a decline of two levels, exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, which resulted in a significant number of South Africans losing their jobs. The COVID-19 pandemic and other financial limitations worsened poverty as most economies were halted for an extended duration (World Bank, 2020). Poverty is caused by other structural inadequacies, such as worker retrenchments, increasing crime rate and violence, structural changes in the family, deterioration of the agricultural sector, slow development in infrastructure, lack of a supportive foundation for start-up businesses, and an unstable power supply to mention a few (Omoniyi, 2018). The poverty issues are made worse by the prevailing high levels of unemployment (Gebel & Gundert, 2023). Perry (2019) emphasized the interdependency of poverty, unemployment, and inequality. The unemployment and earnings inequality data in South Africa have regressed over the years to remain at exceptionally elevated levels compared to international standards (Ventura, 2022).

Beyond the poverty and employment levels, COVID-19 had an effect on life quality, health and well-being, and family and social support. COVID-19 saw countries having different experiences due to the persistent struggle to access even the most basic services. Ajefu et al. (2023) explained that low- and middle-income countries faced substantial difficulties accessing essential necessities like food and medicine during the Covid-19 pandemic compared to high-income and industrialised nations. The restricted availability of fundamental provisions, such as sustenance, water, and other essential necessities, generally obstructed the general welfare of the populace. Despite this, countries like South Africa provide free water and electricity for certain households (Ruiters, 2016) and free primary health care (Chiwire et al., 2021). South Africa implemented preventative measures such as social separation, isolation, and mask usage to mitigate the spread of the infection. This situation placed millions of South African inhabitants in a state of helplessness, causing them to feel isolated and despondent. Families were prohibited from visiting one another and were kept to their respective residences, resulting in minimal social interaction. Citizens have been left requiring human intimacy more than ever before as the health and well-being of the world population were gravely affected, with families separated from loved ones who were infected with the virus, loved ones who died alone in hospitals across the world when visitation rights had to be suspended; and families who had to bury their loved ones in isolation and without the support from their extended families and the circle of friends. It has also proven challenging to maintain a healthy lifestyle with all the unpredictability and worry over finances, elderly parents, job security, lifestyles, and mental health. Undoubtedly, the pandemic has caused significant stress in both home life and communities, particularly among households already facing socio-economic difficulties. However, it is indisputable that family care plays a crucial role in improving the overall well-being of individuals. During the strict lockdowns, immediate family members could mutually support and provide essential financial assistance and childcare. Some parents devised novel activities and games to foster stronger family bonds and relationships while children took on additional familial duties (Orellana et al., 2022). The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic eroded some of the family and social support due to multiple factors, including travel restrictions and limitations on the number of attendees at funerals. The bereaved families were compelled to independently organize the burial and interment of their deceased relatives without the presence of family and community elders. Communal grieving is a prevalent custom in numerous African countries, persisting until the funeral ceremony. In many nations, the grieving procedure involves various therapeutic traditions, some of which necessitate performing them in the presence of the deceased's body at their residence. However, this was not feasible because of the lockdown time (Kgatle & Segalo, 2021).

2.4. Fiscal Support Interventions

Governments around the world intervene with fiscal support to help minimise the impact of COVID-19 on the economy and its citizens. Globally, governments were clearly committed to safeguarding their citizens and businesses in the face of what is expected to be the most significant economic downturn (Mohammed, 2021). Siddik (2020) analysed Economic stimulus for COVID-19 pandemic across more than 100 countries and categorising the countries as low, medium and high response groups to COVID-19. Country features such as median age, hospital beds per capita, total cases of COVID-19 pandemic, GDP, health expenditure, and COVID-19 government stringency index were significant determinants of economic stimulus. Elgin et al. (2022) indicated that nations with a comparatively larger informal sector prior to the epidemic had implemented a lower fiscal policy package. South African government also implemented the Economic Relief Package to alleviate the dire hardship experienced by many individuals (Mazenda et al., 2021). The economic interventions have encompassed a wide range of strategies and magnitudes, varying from 2.5% to a reported 50% of the Gross Domestic Product (Danielli et al., 2020). The Institute for Economic Justice (IEJ) (2020) contended that the magnitude of the rescue package should align with the extent of the crisis. Typically, the amount of COVID-19 government spending announced globally has been approximately equivalent to the projected economic decline in each country. This is because, in the context of a lockdown, each unit of currency spent is expected to have a diminished effect on stimulating economic activity compared to normal circumstances. Estimates of the economic loss in South Africa were approximately 10% before the announcement of the R500bn (US$ =27.03 bn), representing about 10% of the GDP. This intervention included loan guarantees, job support, tax and payment deferrals and holidays, social grants, wage guarantees, health interventions and municipalities support (South African Presidency, 2020). These interventions were in line with other countries around the world (OECD, 2020; IMF, 2020; Danielli et al., 2020). Rhabhi et al. (2020) posit that the government’s actions in many countries globally have yielded both favourable and unfavourable consequences on the economy and its uncertainty. This underscores the significant implications of government intervention in the economy amidst the COVID-19 pandemic.

2.5. Conceptual Model and Study Hypotheses

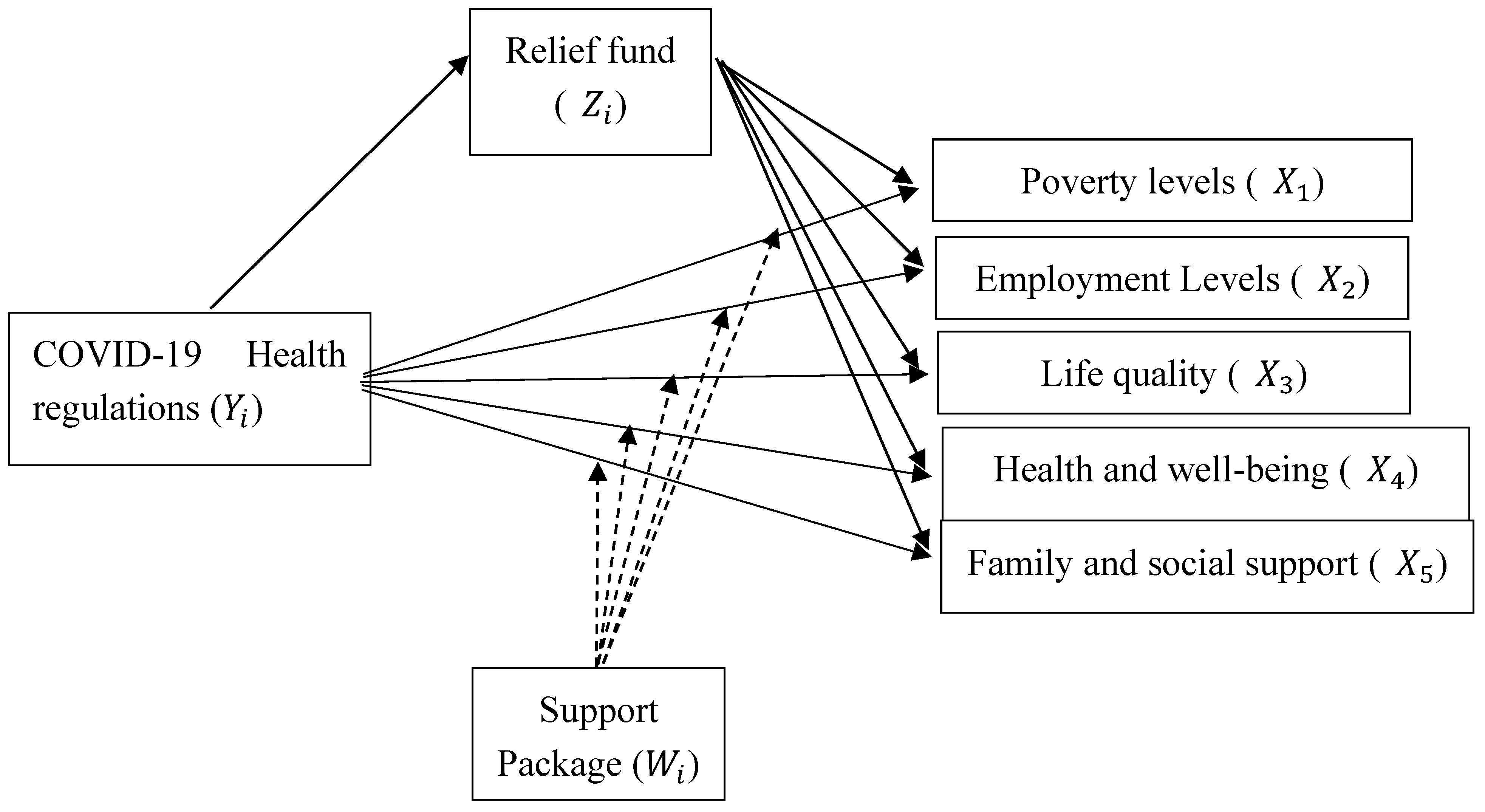

The study's conceptual model illustrates the influence of the COVID-19 Health regulations on socio-economic attributes and the moderating effect of the fiscal support interventions (

Figure 1). The study analyses the COVID-19 health regulations (COV) as the independent variables denoted with X and focuses on five socio-economic dimensions (SED): poverty levels (PVL), employment levels (EMP), life quality (LQT), health and well-being (HWB), and family and social support (FML) as dependent variables denoted with Y. The direct relationship model for the

ith subject is:

within this equation,

is the constant,

is the coefficient and

is the error term. The first hypothesis is:

Hypothesis 1 (H1). COVID-19 has a negative effect on socioeconomic dimensions (1a to 1e). In this mediation analysis, we considered the intervening construct - relief fund (RLF) denoted with

Z, which is known as the mediator to help explain how COV influences SED, which comprises PVL, EMP, LQT, HWB, and FML, denoted

,

…

, respectively. The mediation model for the

ith subject is:

and

are assumed to be uncorrelated error terms. In the analysis, the direct effect moves from

X to

Y while controlling for the mediator,

Z. As such

is the direct effect, while the indirect effect

X to

Y through the mediator,

Z represented by the product of

and

, and the total effect being the sum of direct and indirect effects of

X on

Y. The second hypothesis is:

Hypothesis 2 (H2). Relief fund interventions mediate the COVID-19 health regulations and socio-economic dimensions (2a to 2e). The study also has an interest in the moderation effect of the financial support package (SUP). Hair et al. (2021) posit that moderation is a scenario where the relationship between two constructs is not constant but rather varies based on the values of the moderator (SUP), which can change the strength or even the direction of the relationship of

X and

Y. Considering equation (1) as the basic model, we introduce the moderator,

W into the model and the equation is:

Where is the effect of the moderator on Y and is the coefficient of the interaction term, X and W. The third hypothesis is: Hypothesis 3 (H3). Financial support packages from fiscus interventions moderate the COVID-19 health regulations and socio-economic dimensions (3a to 3e).

3. Methods

The ethical clearance of the study was obtained with reference [FCRE2022/FR/04/006-MS(2)]. An explicit informed consent was obtained from the participants who participated in the survey. The research used cross-sectional quantitative research based on the post-positivist paradigm (Mtotywa, 2019; Leedy & Ormrod, 2019). The population were households in four selected South African Provinces, Eastern Cape, Gauteng, Kwa-Zulu Natal, and Limpopo. These Provinces cover two-thirds of South Africa’s population (66.5%) (Statistics South Africa, 2022). The sample size was calculated using Cochran’s (1977) sample size estimation formula:

Where n represents sample size, while P = expected proportion, Z statistic (Z) = 1.96 and d = precision. The sample size was 384, and the research used a non-probability sampling method employing a convenience sampling technique. A total of 302 responses from this self-administered survey were obtained from different households, equating to 78.6%. This was higher than the average online survey of 44.1% (Wu et al., 2022). The respondents comprised 30.43% male and 69.57% female, where 43.5% were between the ages of 36 and 45 years, 30.2% were aged 35 years or younger, and 26.2% were older than 45 years. Of these respondents, 71.2% lived in the suburbs or city centre, 21.9% lived in townships, and 6.90% lived in a village or a farm. The size of households: 36.09% of the respondents had a household size of 3 members or less, 41.39% had a household size of 4 to 5 members, and 22.18% had a household size of more than 5 members.

A 30-variable instrument using a 7-point Likert scale from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” was developed from the literature focusing on the constructs related to employment levels, poverty, Life quality, health and well-being, family and social support, COVID-19 health regulations, and fiscal support.

Appendix A provides the detailed survey questionnaire. The data was analyses with IBM Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 28 and SmartPLS 4 (Cheah et al., 2023). The empirical data was initially screened and cleaned, starting with the extreme outliers, using z-scores with guidelines of ±3.29 (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013). This was followed by missing value analysis to assess the levels of the missing values, and there were no issues with all variables having missing values of less than 10% (Dong & Peng, 2013). The overall instrument internal consistency was acceptable with Cronbach Alpha, α = 0.765 for the 30 items (George & Mallery, 2019).

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model

The structural equation modeling partial least square (PLS-SEM) using SmartPLS 4, was employed to determine the convergence validity, composite reliability, and discriminant validity (

Table 1).

The final model comprised of 26-variables, with four excluded (shaded grey) due to low factor loading (λ). The factor loadings in the final model all had λ ≥ 0.70 except VAR11 and VAR22, which were higher than 0.6, with the average loading factor for the items of their respective constructs still higher than 0.7 and were thus retained. The model's fit was further assessed using the root mean square residual (RMSR) (Hair et al., 2021). The SRMR measures how well the PLS-SEM model fits the data, and it fits well in this model with RMSR = 0.065, which is better than a threshold of 0.08 (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Henseler et al., 2014). The convergence validity of the constructs was assessed using the Average Variance Extracted (AVE). The results indicate that all constructs demonstrated convergence validity, as their AVE values were all above 0.5 (Hair et al., 2021), ranging from the lowest AVE = 0.598 for LQT and the highest AVE = 0.792 for PVL. Composite reliability with rho_a and rho_c, and α confirmed the reliability of the constructs with all values ≥ 0.70 (Cheung et al., 2023).

The discriminant validity was assessed with a Heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT) matrix (

Henseler et al., 2015). Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio (HTMT) quantifies the comparison between the average correlations among different constructs (heterotraits) and the average correlations within the same construct (monotraits).

Table 2 indicates that all the values in the matrix were less than 0.85 (HTMT

.85), confirming discriminant validity (Voorhees et al., 2015).

4.2. Structural model and hypothesis testing

The structural model diagnostics assessment was performed to evaluate the presence of multicollinearity using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) (

Table 3). The VIF values in the sample were below the recommended threshold of 5, demonstrating the absence of multicollinearity concerns (Hair et al., 2021).

4.2.1. Direct Relationship

The PLS-SEM structural model was determined using bootstrap t-values (5000 sub-samples) (Tortosa et al., 2009). The results show that there is a statistically significant negative relationship between COVID-19 health regulations and employment levels (H1b: β = -0.124, t = 1.989, p <.05). The results also show a statistically significant relationship between COV and LQT (H1d: β = 0.241, t =3.230, p <.01) and COV and FML (H1e: β = 0.318, t = 5.167, p <.001). There was no statistically significant relationship between COV and HWB and COV and PVL with p-values greater than 5%. As such, hypotheses H1b, H1d, and H1e are supported, while H1a and H1c are not supported.

4.2.2. Mediation Analysis

The mediation analysis was performed to determine the mediating role of relief funds (RLF) in the relationship between COVID-19 health regulations (COV) and socioeconomic dimensions (SOE) (

Table 3). The results revealed a statistically significant indirect effect of COV on PVL through RLF (H2a:

β = 0,074,

t = 2.643, p < .05). The total effect of COV on PVL is not statistically significant (

β = -0,036,

t = 0.540,

n.s), and with the inclusion of the mediator the direct effect of COV on PVL was statistically significant (

β = -0,110,

t = 1,685,

n.s). The results indicate that there is full mediation and support

H2a. The results also indicate a statistically significant indirect effect of COV on EMP through RLF (

H2b:

β = 0,043,

t = 2,092, p < .05), with the total effect of COV on EMP not statistically significant but the direct effect of COV on EMP statistically significant (

β = -0,124,

t = 1,989, p < .05), thus indicating a competitive partial mediation effect and support hypothesis 2b. RLF also has a complementary partial mediation effect in the relationship between COV and HWB (

H2c:

β = 0,033,

t = 1.979, p < .05). RLF does not have a mediation effect in COV and LQT, similarly in COV and FML, as such

H2c and

2e are not supported.

4.2.3. Moderation Analysis

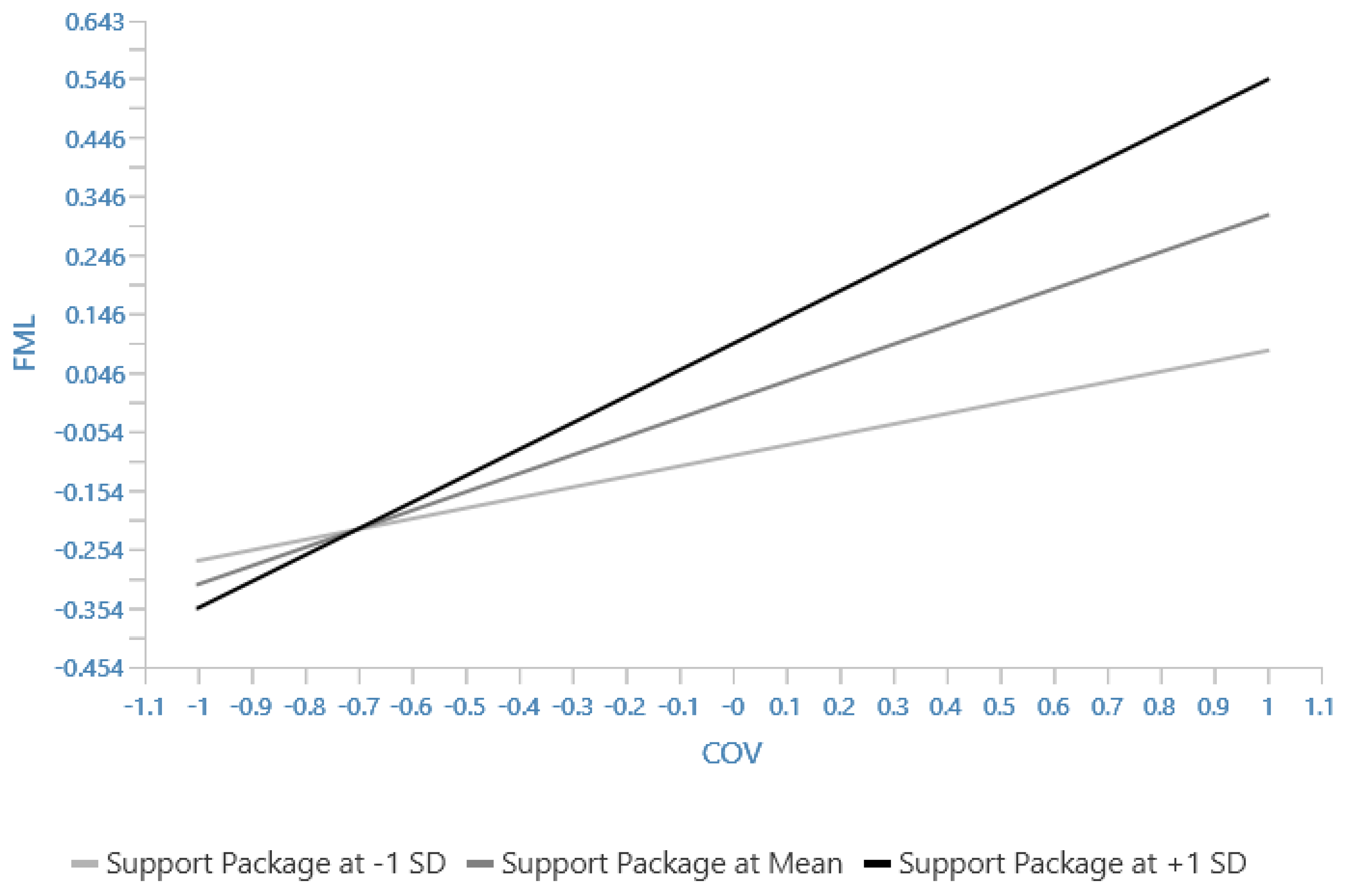

The moderation analysis results show that SUP interventions moderate the relationship between COV and FML, SUPx COV-> FML (

H3e:

β = 0,135,

t = 2,817, p < .01). The simple slope analysis show that at higher SUP (+1SD) the COV has higher impact on FML, while at low SUP (-1SD), increased COV has low impact on FML (

Figure 2). This means that with the increase in COV, the FML increases because the SUP increases (steeper gradient). SUP does not have a moderating effect in other relationships in the model; as such,

H3e is supported, while

Ha –

Hd is not supported.

4.3.4. Multigroup Analysis

Multigroup analysis was employed in the SEM to determine the mediation and moderation effects changed across the different demographic parameters - gender, age, area of stay, and number of members in a household (

Table 4). The results show that there was no statistically significant difference between females and males except for SUP moderation of COV and LQT. These results show that SUP moderated the relationship between COV and LQT more for females than males. We also compared the different age groups, and there were several statistically significant differences between them; RLF mediated the relationship between COV and PVL stronger for age groups older than 45 years than those 35 years and younger. The same pattern was also evident for RLF on COV and EMP.

SUP moderated COV and FML better for 45 years and older than 35 years and younger, and similarly for 35 – 45 years than 35 years and younger. SUP moderated the relationship between COV and PVL between 35 years and younger than 35 – 45-year-olds. We compared the different areas of stay, suburbs or city-centre, townships, and villages or farms. The results showed no statistically significant difference for the different structural paths. Similarly, there were no statistically significant differences between the different groups of members of the households (3 members or less, 4 – 5 members, more than five members) except one, where SUP moderated better the relationship between COV and PVL for those having 3-member household or less than those with 4 – 5 members of the households.

5. Discussion

COVID-19 health regulations comprised of measures that prevented non-essential activities outside the home, set limitations on all public meetings, resulted in the closure of all schools, and implemented a curfew. These regulations also prohibited the sale of tobacco goods and spirits and established stringent internal and international travel controls (Van Walbeek et al., 2021; Köhler et al., 2023) at Alert Level 5, with the measures relaxed at the changes to lower alert levels (Department of Health, 2020).

This paper investigated fiscal support interventions on health regulations and socio-economic dimensions. Through survey analysis, we found that the relief fund, which entailed the COVID-19 Social Relief of Distress allowance of R350 per month, unemployment insurance fund claim, and food parcel distribution, among others, had a full-mediation effect on the relationship between COVID-19 health regulations and poverty levels. This confirms the effectiveness of government intervention on poverty with fiscal intervention (Khambule, 2021) to mitigate the increased poverty that was exacerbated by COVID-19 and its associated health regulations (Bassier et al., 2023). The results also reveal that relief funding has a competitive partial mediation effect between COVID-19 health regulations and employment levels. Unsurprisingly, relief funds had an intervening role as poverty and employment are generally intertwined (Perry, 2019). Noticeably, though, it is a competitive mediation that occurs in a situation where both indirect and direct effects are present, but they have opposite directions, also known as inconsistent mediation (Zhao et al., 2010). This implies that there are other factors that influence employment levels. This is not surprising considering the chronic challenges of high unemployment levels in South Africa. Ventura (2022) highlighted that South Africa had regressed over the years to remain at exceptionally high levels of unemployment compared to international standards. Bassier et al. (2023) posited that between February and April 2020, there was a significant 40% decrease in the number of people employed. Out of this fall, half of it was due to job terminations rather than temporary furloughs. The official unemployment climbed by 1% from quarter 4 in 2019, before the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, and quarter 1 in 2020 to 30.1%, then further continued to deteriorate, peaking at 35,3% in quarter 4 in 2021, then improved post-COVID-19 to 31.9% in quarter 3 of 2023 (Statistics South Africa, 2023). Despite the improvement, it still has not reached the pre-COVID-19 unemployment level of 29.1%. (Statistics South Africa, 2020).

The results also revealed that relief funds fully mediate the relationship between COVID-19 health regulations and health and well-being. This meant that the relief fund contributed towards health and well-being, which included stress, anxiety, and other related mental illness which was had increased due to Covid-19 (Mendelsohn et al., 2022). The crisis theory posits that individuals experiencing a condition of crisis exhibit heightened anxiety and are receptive to assistance. Thus, the rationale behind crisis theory is the conviction that offering assistance and direction to those in crisis will result in long-term mitigation of mental health issues. This aligned the reasoning behind the relief fund mediating the COVID-19 regulations and health and well-being. Relief funds did not have a mediation effect on COVID-19 regulations, life quality, or family and social support. The lack of mediation effect on life quality might be attributed to the comprehensive social service offering by the government, in particular, meant that free water and electricity for certain households (DPLG, 2005; Bhorat, 2012; Ruiters, 2016), free health services and access in the event of illness (Chiwire et al., 2021) which remained available even during Covid-19. The results also reveal that the R500 billion government support package moderates the relationship between COVID-19 health regulations and family and social support. The COVID-19 pandemic has had enormous impacts on the health system, society, and economy of countries around the world, including South Africa. Invoking emergency regulations and adopting national health regulations such as lockdowns significantly impacted the country's health and economy. Despite the COVID-19 health regulation helping to protect the lives of the communities, the regulations negatively impacted the economy, which was partially mitigated by the fiscal support interventions.

The impact of COVID-19 regulations on socioeconomic dimensions was fairly similar irrespective of gender, number of members in a household, or areas of stay, notwithstanding that one situation each. However, there were some patterns with age, where the impact was less on the 35-year-olds and younger for poverty and unemployment. This is not surprising, considering that almost 60% of the youth in South Africa are unemployed (Statistics South Africa, 2023).

6. Conclusion, Implications, and Suggested Future Direction

The COVID-19 pandemic outbreak brought the crisis with the COVID-19 health regulations and fiscal support interventions central in the attempts by the governments to minimise the impact on society. We performed a post-COVID-19 analysis of fiscal support interventions on health regulations and socio-economic dimensions. We concluded that COVID-19 regulation impacted socioeconomic dimensions, and the relief fund was a critical intervention to mediate poverty and employment. We can also conclude that other government support packages, which encompass loan guarantees, job support, tax and payment deferrals, social grants, wage guarantees, health interventions, and municipality support, helped mitigate the impact of COVID-19 health regulations. These results confirm the effectiveness of the government's budgetary support intervention in reducing the impact of its emergency response to COVID-19 health standards. This supports the notion of intervention and emphasises its intricacy, underscoring the significance of comprehensive intervention for future readiness and improving the perspective on crisis intervention.

6.1. Policy Implications

The multi-nature and complexity of the COVID-19 pandemic require understanding to develop holistic interventions that will balance health and economic disruptions in society. The analysis in this study is imperative for the government to respond to shocks that result in chaos that continue to occur at heightened levels of pandemic or other major events that disrupt the societies to build knowledge as there are insufficient tools to identify emerging threats and opportunities in a complex environment (Ercetin & Potas, 2019). Based on the empirical findings of this study, policymakers should focus on the determinants of economic stimulus of COVID-19 design more economic stimulus packages in such a way that they would be able to mitigate the negative effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. This is done through developing socio-demographic specifics like age-specific initiatives and socio-economic-specific interventions guided by ‘triple-challenges’ of poverty, employment, and inequality for developing countries such as South Africa. There is also a need to strengthen the systems and processes to ensure the policy interventions succeed. This considering that despite the positive impact of the fiscal interventions, there were issues such as corruption (John, 2021; Maxwell, 2022; Wesso & Hamman; 2023) which was even evident in food parcels that were part of the relief fund (Mudau, 2022) and delays (Khambule, 2021) in execution that would have comprised its full effectiveness.

6.2. Theoretical Implications

The theory of intervention is essential to ensure that interventions are not merely a collection of random activities but are carefully planned and executed with a thorough comprehension of the anticipated mechanisms of change. It increases the probability of success and offers a structure for assessment and continuous improvement. Having an intimate understanding of the crisis helps to plan intervention better, minimising the negative consequence of the intervention. Furthermore, it highlights the importance of inter- and intra-crisis learning. Quaglia and Verdun (2022). Explained that the process of policy learning gained from its experience with previous crises (inter-crisis learning) and valuable lessons (intra-crisis learning) are central to the management of the crisis as this helps to enhance the importance of timing (quick action). This imperative are important to elevate a need to further develop a crisis-intervention perspective.

6.3. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

The research was not without limitations, noticeable the convenience sampling and inadequate balance in respondents, for example, with gender, where females dominated compared to males. Additionally, not all South African provinces were covered in this study. Despite this, the study provides critical insights necessary for policy improvement and theoretical contributions. For future research, we recommend expanding the study to include all the provinces and possibly conducting a comparative analysis between developed and developed countries. This will validate our findings and provide lessons that can help optimise the interventions. Furthermore, a study should be conducted on all the different elements of fiscal support to understand the ones with a higher impact than the others. The necessity of this analytical route was evident in this study, where the relief fund’s importance was advanced as part of the bigger fiscal support package.

Appendix A. Survey Questionnaire Items

| Items |

| The coronavirus had an impact on our employment status in our household (Loss of work, diminished income) |

VAR1 |

| COVID-19 had a negative impact on our levels of poverty in our household (affordability) |

VAR2 |

| COVID-19 had a negative impact on our equality compared to other families in my community (progress in life or well-being) |

VAR3 |

| The COVID-19 had an impact on our way of life (e.g., family, social interaction, or community safety) |

VAR4 |

| I or a member of my family have lost employment due to Covid-19 |

VAR5 |

| A member of my family and I are struggling to find employment due to Covid-19. |

VAR6 |

| I or a member of my family are working reduced hours due to Covid-19 |

VAR7 |

| A member of my family or I have had a contract of employment terminated due to COVID-19. |

VAR8 |

| A member of my family or I have had to relocate to find employment since COVID-19 (past 28 months). |

VAR9 |

| My family is still able to have three meals a day |

VAR10 |

| My family has access to running water |

VAR11 |

| My family has a warm shelter to keep from bad weather conditions. |

VAR12 |

| My family members can afford to see a doctor (hospital) in the event of illness. |

VAR13 |

| My family is able to afford clothing for all our family members |

VAR14 |

| I or a member of my family suffers from stress due to Covid-19 challenges |

VAR15 |

| I or a member of my family suffers from anxiety due to the impact of COVID-19. |

VAR16 |

| I or a member of my family is experiencing increased alcohol usage due to COVID-19. |

VAR17 |

| I or a member of my family is experiencing increased drug usage due to COVID-19. |

VAR18 |

| A member of my family or I have had to seek help for a mental illness due to COVID-19. |

VAR19 |

| My family has received the family support needed during a time of difficulty since the COVID-19 outbreak. |

VAR20 |

| My family has received the social support needed during a time of difficulty since the COVID-19 outbreak. |

VAR21 |

| I and members of my family have felt the support of our friends even over the COVID-19 lockdown periods. |

VAR22 |

| Our family has maintained strong family ties even after the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic. |

VAR23 |

| A member of my family or I have been a recipient of the government relief fund ( R350 unemployment Fund, UIF Claim, Top up grant, Food parcel distribution, etc. ) |

VAR24 |

| The R500 billion government support package has cushioned the financial negative impact caused by COVID-19. |

VAR25 |

| The Lockdown imposed by the government has helped to flatten the curve for COVID–19 infections. |

VAR26 |

| The Travel bans introduced by the government has minimized the full impact of Covid-19 on the Country. |

VAR27 |

| The curfews introduced by the government have helped mitigate the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic. |

VAR28 |

| Making the wearing of face masks mandatory has assisted in the spreading of the COVID-19 Virus. |

VAR29 |

| Limiting the number of people attending funerals, cremations, and other gatherings has been helpful in reducing the infection rate of Covid-19. |

VAR30 |

References

- Aftab, A. (2023). Perceptions of Dental Students towards Online Teaching during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Open Access Journal of Dental Sciences, 8(1). [CrossRef]

- Ajefu, J. B., Demir, A., & Rodrigo, P. (2023). COVID-19-induced Shocks, Access to Basic Needs and Coping Strategies. The European Journal of Development Research, 35(6), 1347–1368. [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, H., Sharifi, A., Damanbagh, S., Hadi Nazarnia, H. & Nazarnia, M. (2023). Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the social sphere and lessons for crisis management: a literature review. Nat Hazards (2023). [CrossRef]

- Arias-Maldonado, M. (2020). COVID-19 as a Global Risk: Confronting the Ambivalences of a Socionatural Threat. Societies, 10(4), 92. MDPI AG. [CrossRef]

- Arndt, C., Davies, R., Gabriel, S., Harris, L., Makrelov, K., Modise, B., Robinson, S., Simbanegavi, W., van Seventer, D., & Anderson, L. (2020). Impact of Covid-19 on the South African economy: An initial analysis. SA-TIED Working Paper 111. https://sa-tied.wider.unu.edu/sites/default/files/pdf/SA-TIED-WP-111.pdf.

- Ashcroft, R., Sur, D., Greenblatt, A., & Donahue, P. (2021). The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Social Workers at the Frontline: A Survey of Canadian Social Workers. The British Journal of Social Work, 52(3), 1724–1746. [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y., Wang, Q., Liu, M., Bian, L., Liu, J., Gao, F., Mao, Q., Wang, Z., Wu, X., Xu, M. & Liang, Z. (2022). The next major emergent infectious disease: reflections on vaccine emergency development strategies, Expert Review of Vaccines, 21:4, 471-481. [CrossRef]

- Bassier, I., Budlender, J., Zizzamia, R., & Jain, R. (2023). The labor market and poverty impacts of COVID-19 in South Africa. South African Journal of Economics, 91(4), 419–445. [CrossRef]

- Boin, A., & Rhinard, M. (2022). Crisis management performance and the European Union: the case of COVID-19. Journal of European Public Policy, 30(4), 655–675. [CrossRef]

- Bricka, T. M., He, Y., & Schroeder, A. N. (2022). Difficult Times, Difficult Decisions: Examining the Impact of Perceived Crisis Response Strategies During COVID-19. Journal of Business and Psychology, 38(5), 1077–1097. [CrossRef]

- Bhorat, H., Oosthuizen, M., & van der Westhuizen, C. (2012). Estimating a poverty line: An application to free basic municipal services in South Africa. Development Southern Africa, 29(1), 77–96. [CrossRef]

- Canadian Human Rights Commission. (2020) Statement - Inequality amplified by COVID-19 crisis, 2020. Available: https://www.chrcccdp.gc.ca/eng/content/statement-inequality-amplified-covid-19- crisis.

- Centre of Excellence in Financial Services (2023). Lessons from the COVID-19 Pandemic in South Africa. [Online] Available from: https://www.resbank.co.za/content/dam/sarb/what-we-do/financial-stability/Lessons%20from%20the%20Covid-19%20pandemic%20in%20South%20Africa.pdf [Accessed 2 June 2023].

- Cheah, J. H., Magno, F., & Cassia, F. (2023). Reviewing the SmartPLS 4 software: the latest features and enhancements. Journal of Marketing Analytics. [CrossRef]

- Cheung, G. W., Cooper-Thomas, H. D., Lau, R. S., & Wang, L. C. (2023). Reporting reliability, convergent and discriminant validity with structural equation modeling: A review and best-practice recommendations. Asia Pacific Journal of Management. [CrossRef]

- Chiwire, P., Evers, S. M., Mahomed, H., & Hiligsmann, M. (2021). Willingness to pay for primary health care at public facilities in the Western Cape Province, Cape Town, South Africa. Journal of Medical Economics, 24(1), 162–172. [CrossRef]

- Chitiga-Mabugu, M., Henseler, M., Mabugu, R. & Maisonnave, H. (2021). Economic and distributional impact of COVID-19: Evidence from macro-micro modelling of South African economy. South African Journal of Economics. 89(1), 82-94.

- Chung, H.W., Apio, C., Goo, T. et al. (2021). Effects of government policies on the spread of COVID-19 worldwide. Sci Rep 11, 20495 . [CrossRef]

- Clay, K. C., Abdelwahab, M., Bagwell, S., Barney, M., Burkle, E., Hawley, T., Kehoe Rowden, T., LaVelle, M., Parker, A., & Rains, M. (2022). The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on human rights practices: Findings from the Human Rights Measurement Initiative’s 2021 Practitioner Survey. Journal of Human Rights, 21(3), 317–333. [CrossRef]

- Cochran, W. G. (1977). Sampling techniques (3rd ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Cohen, J. (1988). Set Correlation and Contingency Tables. Applied Psychological Measurement, 12(4), 425–434. [CrossRef]

- Coller RJ, Webber S. COVID-19 and the well-being of children and families. Pediatrics 2020;146:e2020022079.

- Danielli, S., Patria, R., Donnelly, P., Ashrafian, H., & Darzi, A. (2020). Economic interventions to ameliorate the impact of COVID-19 on the economy and health: an international comparison. Journal of Public Health, 43(1), 42–46. [CrossRef]

- de Koning, R., Egiz, A., Kotecha, J., Ciuculete, A. C., Ooi, S. Z. Y., Bankole, N. D. A., Erhabor, J., Higginbotham, G., Khan, M., Dalle, D. U., Sichimba, D., Bandyopadhyay, S., & Kanmounye, U. S. (2021). Survey Fatigue During the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Analysis of Neurosurgery Survey Response Rates. Frontiers in Surgery, p. 8. [CrossRef]

- Department of Health. (2020). Government Notices No R 867 - No. 43599. Disaster Management Act, 2002: Pretoria.

- Dong, Y & Peng, C.Y. (2013). Principled missing data methods for researchers. Springerplus, 2 (1), 1-17.

- DPLG National Framework – Department of Provincial and Local Government. (2005). National Framework for Municipal Indigent Policies. Pretoria: Government Printers.

- Dukhi, N., Mokhele, T., Parker, W. A., Ramlagan, S., Gaida, R., Mabaso, M., Sewpaul, R., Jooste, S., Naidoo, I., Parker, S., Moshabela, M., Zuma, K., & Reddy, P. (2021). Compliance with Lockdown Regulations During the COVID-19 Pandemic in South Africa: Findings from an Online Survey. The Open Public Health Journal, 14(1), 45–55. [CrossRef]

- Elgin, C., Williams, C. C., Oz-Yalaman, G., & Yalaman, A. (2022). Fiscal stimulus packages to COVID-19: The role of informality. Journal of International Development, 34(4), 861–879. [CrossRef]

- European Commission (2021). Q&A: Future pandemics are inevitable, but we can reduce the risk. [Online] Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/research-and-innovation/en/horizon-magazine/qa-future-pandemics-are-inevitable-we-can-reduce-risk. [Accessed 5 June 2023].

- Fauci, A.S., Folkers, G.K. (2023). Pandemic Preparedness and Response: Lessons From COVID-19, The Journal of Infectious Diseases, jiad095. [CrossRef]

- Ferhani, A., & Rushton, S. (2020). The International Health Regulations, COVID-19, and bordering practices: Who gets in, what gets out, and who gets rescued? Contemporary Security Policy, 41(3), 458–477. [CrossRef]

- Folayan, M. O., Abeldaño Zuñiga, R. A., Virtanen, J. I., Ezechi, O. C., Yousaf, M. A., Jafer, M., Al-Tammemi, A. B., Ellakany, P., Ara, E., Ayanore, M. A., Gaffar, B., Aly, N. M., Idigbe, I., Lusher, J., El Tantawi, M., & Nguyen, A. L. (2023). A multi-country survey of the socio-demographic factors associated with adherence to COVID-19 preventive measures during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Public Health, 23(1). [CrossRef]

- Fuller, C.M., Simmering, M.J., Atinc, G., Atinc, Y.O., & Babin, B.J. (2016). Common methods variance detection in business research. Journal of Business Research, 69, 3192-3198.

- George, D., & Mallery, P. (2019). IBM SPSS Statistics 26 Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference (16th ed.). Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Gebel, M., & Gundert, S. (2023). Changes in Income Poverty Risks at the Transition from Unemployment to Employment: Comparing the Short-Term and Medium-Term Effects of Fixed-Term and Permanent Jobs. Social Indicators Research, 167(1–3), 507–533. [CrossRef]

- Giuntellaa, O., Hydea, K., Saccardob, S., & Sadoffc, S. (2021). Lifestyle and mental health disruptions during COVID-19. PNAS 118 (9) e2016632118. [CrossRef]

- Hair Jr, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., Danks, N. P., & Ray, S. (2021). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) using R: A workbook. [CrossRef]

- Headey, D., Goudet, S., Lambrecht, I., Maffioli, E. M., Oo, T. Z., & Russell, T. (2022). Poverty and food insecurity during COVID-19: Phone-survey evidence from rural and urban Myanmar in 2020. Global Food Security, 33, 100626. [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. [CrossRef]

- Haug, N., Geyrhofer, L., Londei, A., Dervic, E., Desvars-Larrive, A., Loreto, V., Pinior, B., Thurner, S., & Klimek, P. (2020). Ranking the effectiveness of worldwide COVID-19 government interventions. Nature Human Behaviour, 4(12), 1303–1312. [CrossRef]

- IMF. (2020). Policy responses to COVID-19. Available online from https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/imf-and-covid19/Policy-Responses-to-COVID-19.

- Institute for Economic Justice (IEJ) (2020). An emergency rescue package for South Africa in response to COVID-19. Available online from http//www.groundup.org.za/media/uploads/documents/IEJFull.pdf.

- John, V. M. (2021). The Violence of South Africa’s COVID-19 Corruption. Peace Review, 33(1), 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Khambule, I. (2021). COVID-19 and the Counter-cyclical Role of the State in South Africa. Progress in Development Studies, 21(4), 380–396. [CrossRef]

- Khowa, T., Cimi, A. & Mukasi, T. (2022). Socio-economic impact of COVID-19 on rural livelihoods in Mbashe Municipality, Jàmbá: Journal of Disaster Risk Studies 14(1), a1361. [CrossRef]

- Kithiia J, Wanyonyi I, Maina J, Jefwa T, Gamoyo M (2020) The socio-economic impacts of Covid-19 restrictions: Data from the coastal city of Mombasa. Kenya Data in Brief 33:106317.

- Köhler, T., Bhorat, H., Hill, R., & Stanwix, B. (2023). Lockdown stringency and employment formality: evidence from the COVID-19 pandemic in South Africa. Journal for Labour Market Research, 57(1). [CrossRef]

- Hankonen, N. (2013). Intervention Theories. In: Gellman, M.D., Turner, J.R. (eds) Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine. Springer, New York, NY. [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, S. (2022). The Impact of Corruption and Unethical Conduct During COVID-19 Pandemic on Public Funds, South Africa. Journal of Public Policy and Administration, 6(1), 1. [CrossRef]

- Moens, E., Lippens, L., Sterkens, P., Weytjens, J., & Baert, S. (2021). The COVID-19 crisis and telework: a research survey on experiences, expectations and hopes. The European Journal of Health Economics, 23(4), 729–753. [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, M. (2021). The role of fiscal stimulus packages in addressing economic conditions during the Covid-19 pandemic. TANMIYAT AL-RAFIDAIN, 40(132), 344–362. [CrossRef]

- Moore, G., Cambon, L., Michie, S., Arwidson, P., Ninot, G., Ferron, C., Potvin, L., Kellou, N., Charlesworth, J., & Alla, F. (2019). Population health intervention research: the place of theories. Trials, 20(1). [CrossRef]

- Moyer, J. D., Verhagen, W., Mapes, B., Bohl, D. K., Xiong, Y., Yang, V., McNeil, K., Solórzano, J., Irfan, M., Carter, C., & Hughes, B. B. (2022). How many people is the COVID-19 pandemic pushing into poverty? A long-term forecast to 2050 with alternative scenarios. PLOS ONE, 17(7), e0270846. [CrossRef]

- Mtotywa, M.M. (2019). Conversations with Novice Researchers. AndsM: East London.

- Mtotywa, M. M., & Mtotywa, V. L. V. (2022). Diagnostic assessment of post-COVID-19 operations for business model reconfiguration decision. Journal of Management and Research, 9(2), 66–94. [CrossRef]

- Mudau, P. (2022). The Implications of Food-Parcel Corruption for the Right to Food during the COVID-19 Pandemic in South Africa. SSRN Electronic Journal. [CrossRef]

- Newson, M., Zhao, Y., Zein, M. E., Sulik, J., Dezecache, G., Deroy, O., & Tunçgenç, B. (2021). Digital contact does not promote wellbeing, but face-to-face contact does: A cross-national survey during the COVID-19 pandemic. New Media & Society, 146144482110621. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, B.B. & Raswant, A (2018). The selection, use, and reporting of control variables in international business research: A review and recommendations. Journal of World Business, 53(6), 958-968. [CrossRef]

- Nicola M, Zaid A, Sohrabi C, Kerwan A, Al-Jabir A, et al. (2020). The socio-economic implication of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): A Review. International. Journal of Surgery, 78, 185-193.

- Nikolaidis, A., Paksarian, D., Alexander, L., Derosa, J., Dunn, J., Nielson, D. M., Droney, I., Kang, M., Douka, I., Bromet, E., Milham, M., Stringaris, A., & Merikangas, K. R. (2021). The Coronavirus Health and Impact Survey (CRISIS) reveals reproducible correlates of pandemic-related mood states across the Atlantic. Scientific Reports, 11(1). [CrossRef]

- OECD (2020). Key policy responses from OECD. Available online from https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/en/#policy-responses.

- Padhan, R., & Prabheesh, K. (2021). The economics of COVID-19 pandemic: A survey. Economic Analysis and Policy, 70, 220–237. [CrossRef]

- Parsons Leigh, J., Fiest, K., Brundin-Mather, R., Plotnikoff, K., Soo, A., Sypes, E. E., Whalen-Browne, L., Ahmed, S. B., Burns, K. E. A., Fox-Robichaud, A., Kupsch, S., Longmore, S., Murthy, S., Niven, D. J., Rochwerg, B., & Stelfox, H. T. (2020). A national cross-sectional survey of public perceptions of the COVID-19 pandemic: Self-reported beliefs, knowledge, and behaviors. PLOS ONE, 15(10), e0241259. [CrossRef]

- Perry, J. (2019). African Truth Commissions and Transitional Justice. New York: Lexington Books.

- Quaglia, L., & Verdun, A. (2022). Explaining the response of the ECB to the COVID-19 related economic crisis: inter-crisis and intra-crisis learning. Journal of European Public Policy, 30(4), 635–654. [CrossRef]

- Rabhi, A., Bennagem Touati, A., & Haoudi, A. (2020). The Nexus between Government Intervention and Economic Uncertainty during the COVID-19 Pandemic. SSRN Electronic Journal. [CrossRef]

- Radu, M.-C.; Schnakovszky, C.; Herghelegiu, E.; Ciubotariu, V.-A.; Cristea, I. (2020). The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Quality of Educational Process: A Student Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, 17, 7770. [CrossRef]

- Rawson T, Brewer T, Veltcheva D, Huntingford C, Bonsall M.B. (2020). How and When to End the COVID-19 Lockdown: An Optimization Approach. Front Public Health, 8: 262.

- Rönkkö, R., Rutherford, S., & Sen, K. (2022). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the poor: Insights from the Hrishipara diaries. World Development, 149, 105689. [CrossRef]

- Ruiters, G. (2016). The Moving Line Between State Benevolence and Control: Municipal Indigent Programmes in South Africa. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 53(2), 169–186. [CrossRef]

- Schnitzler, L., Janssen, L., Evers, S., Jackson, L., Paulus, A., Roberts, T., & Pokhilenko, I. (2021). The broader societal impacts of COVID-19 and the growing importance of capturing these in health economic analyses. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care, 37(1), E43. [CrossRef]

- Schotte, S., & Zizzamia, R. (2022). The livelihood impacts of COVID-19 in urban South Africa: a view from below. Social Indicators Research, 165(1), 1–30. [CrossRef]

- Shang, Y., Li, H., & Zhang, R. (2021). Effects of Pandemic Outbreak on Economies: Evidence From Business History Context. Frontiers in Public Health, 9. [CrossRef]

- Siddik, M. N. A. (2020, December). Economic stimulus for COVID-19 pandemic and its determinants: evidence from cross-country analysis. Heliyon, 6(12), e05634. [CrossRef]

- South African Presidency. (2020). Statement by President Cyril Ramaphosa on further economic and social measures in response to the COVID-19 epidemic. The South African Presidency.

- Shmueli, G., M. Sarstedt, J.F. Hair, J.-H. Cheah, H. Ting, S. Vaithilingam, and C.M. Ringle. (2019). Predictive model assessment in PLS-SEM: Guidelines for using PLSpredict. European Journal of Marketing 53 (11): 2322–2347.

- Sumner, A., Hoy, C. & Ortiz-Juarez, E. (2020). Estimates of the impact of COVID-19 on global poverty. WIDER Working Paper 2020/43. United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research. [Online] Available from: https://www.wider.unu.edu/sites/default/files/Publications/Working-paper/PDF/wp2020-43.pdf. [Accessed 1 June 2023].

- Susič, D., Tomšič, J., & Gams, M. (2022). Ranking Effectiveness of Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions Against COVID-19: A Review. Informatica, 46(4). [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2013). Using multivariate statistics (6th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

- Tran, T.K.; Dinh, H.; Nguyen, H.; Le, D.-N.; Nguyen, D.-K.; Tran, A.C.; Nguyen-Hoang, V.; Nguyen Thi Thu, H.; Hung, D.; Tieu, S.; et al. (2021). The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on College Students: An Online Survey. Sustainability, 13, 10762. [CrossRef]

- United Nations (2023). World must be ready to respond to next pandemic: WHO chief. [Online] Available from: https://news.un.org/en/story/2023/05/1136912. [8 June 2023].

- Van Walbeek, C., Hill, R., Filby, S., van der Zee, K (2021). Market impact of the COVID-19 national cigarette sales ban in South Africa. National Income Dynamics Study Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey Wave 3 Policy Paper No. 11.

- Van der Waldt, G. (2015). Government Interventionism and Sustainable Development: The Case of South Africa. African Journal of Public Affairs, 8(2): 35-51.

- Vermeulen, W.J.V. and Kok, M.T.J. (2012). Government Interventions in Sustainable Supply Chain Governance: Experience in Dutch Front-running Cases. Ecological Economics, 83:183–196.

- Voorhees, C. M., Brady, M. K., Calantone, R., & Ramirez, E. (2015). Discriminant validity testing in marketing: an analysis, causes for concern, and proposed remedies. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 44(1), 119–134. [CrossRef]

- Walby, S. (2022). Crisis and society: developing the crisis theory in the context of COVID-19. Global Discourse, 12(3–4), 498–516. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Hegde, S., Son, C., Keller, B., Smith, A., & Sasangohar, F. (2020). Investigating Mental Health of US College Students During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Cross-Sectional Survey Study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(9), e22817. [CrossRef]

- Weiss, J.A. (2000) From Research to Social Improvement: Understanding Theories of Intervention. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 29(1), 81-110.

- Wesso, C., & Hamman, A. (2023, January 12). Grappling with the scourge of money laundering during the Covid-19 pandemic in South Africa. Journal of Anti-Corruption Law, 6(1). [CrossRef]

- World Bank (2020). Measuring poverty. [Online]. Available from: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/measuringpoverty [Accessed: 30 August 2023].

- World Health Organization (2022). WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard. [Online]. Available from: https://covid19.who.int/ [ Accessed 18 March 2022].

- World Health Organization (2023). Statement on the fifteenth meeting of the IHR (2005) Emergency Committee on the COVID-19 pandemic [Online] Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/05-05-2023-statement-on-the-fifteenth-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-coronavirus-disease-(covid-19)-pandemic?adgroupsurvey={adgroupsurvey}&gclid=CjwKCAjw1YCkBhAOEiwA5aN4ATC1w9CRFr_Q2nZLtdwO1zd5LHZ66vOg3_cNeDV7JchBSQDcvQ5d9RoCl7cQAvD_BwE. [Accessed 8 June 2023].

- Won JY, Lee YR, Cho MH, Kim YT, Heo BY. (2022). Impact of Government Intervention in Response to Coronavirus Disease 2019. Int J Environ Res Public Health. [CrossRef]

- Wu, M., Zhao, K. & Fils-Aime, F. (2022). Response rates of online surveys in published research: A meta-analysis. Computers in Human Behavior Reports, 7, 2022. Retrieved from Loyola Ecommons, Education: School of Education Faculty Publications and Other Works.

- Zhao, X., Lynch, J. G., & Chen, Q. (2010). Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and Truths about Mediation Analysis. Journal of Consumer Research, 37(2), 197–206. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).