I. Introduction

Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI): is the hype real or it’s another technology in its early stages, with a lot of promises? In recent years, the field of artificial intelligence has witnessed a remarkable transformation with the emergence of generative AI and Large Language Models (LLMs). These technologies have revolutionized how machines understand, process, and generate human language, marking a significant milestone in the evolution of AI capabilities [

1]. Generative AI, particularly in the form of LLMs, has captured widespread attention not only within academic and research communities but also across industries, governments, and the general public [

2]. The launch of GPT models by OpenAI in November 2022 can be considered as a turning point for artificial intelligence, which later can be referred as 0-day for GenAI.

Generative AI refers to artificial intelligence systems capable of creating new content, including text, images, audio, code, and other media formats, based on patterns learned from existing data [

3]. Its ability depends on data which was used for training and the prompts provided by a user. The focal point of this technological revolution are Large Language Models—sophisticated neural network architectures trained on datasets of text data that can generate coherent, contextually relevant, and increasingly human-like responses to prompts [

4]. These models have demonstrated unprecedented capabilities in understanding context, generating creative content, answering complex questions, and even proving some incipient reasoning abilities that were previously thought to be exclusively human domains [

5].

LLMs are more than simple text generators. These models are transforming numerous fields, from healthcare and education to software development and creative industries [

6]. In healthcare, LLMs are being utilized for clinical documentation, medical research synthesis, and patient communication [

7]. Software developers leverage their coding capabilities using LLMs these models for code generation and debugging assistance [

8], while creative professionals like artists and social media influencers use them for content creation, and design [

9]. Even in research LLMs can be used to analyze different data and provide insights which were not previously discovered. The versatility and adaptability of LLMs have positioned them as one of the most significant technological advancements of the 21st century [

10].

Modern LLMs are basically the result of decades of work in areas like natural language processing, machine learning, and neural networks — all that research finally coming together [

11]. The big game-changer came in 2017 when the transformer architecture was introduced — it completely changed the way AI handles texts [

12]. This new setup, thanks to something called self-attention, allowed models to understand the bigger picture in language — like how words relate to each other even if they’re far apart in a sentence — way better than anything before. [

13]. Subsequent innovations in training methodologies, computational resources, and data availability have led to the rapid evolution of increasingly powerful models, from GPT (Generative Pre-trained Transformer) to BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers), LaMDA, PaLM, and beyond [

14]. While until recent days, LLMs required huge Graphical Processing Unit (GPU) resources, recent technological advances from the Chinese company DeepSeek now enable end users to deploy powerful, efficient language models using significantly fewer computational resources and even CPU usage. These advancements improve accessibility, allowing smaller organizations, researchers, and even individuals to leverage sophisticated LLM capabilities on more affordable hardware setups, significantly reducing operational costs and broadening the practical applicability of generative AI [

15].

Even though LLMs are powerful, there are some important problems and limitations which development must overcome. These include tendencies to generate plausible-sounding but factually incorrect information (hallucinations) [

16], perpetuate biases which can be detected in training data [

17], and consume substantial high amounts of computational resources during training [

18]. People have also started worrying about things like privacy, ownership of content, and how these models might be used in the wrong way — all of which have become really important issues.[

19]. The main idea would be that if AI is doing something bad, who should be accounted for it. As these technologies continue to evolve and integrate into unimagined dimensions of modern society, addressing these challenges becomes increasingly important for responsible development and deployment [

16].

This scientific review aims to provide a comprehensive examination of generative AI and Large Language Models, exploring their historical evolution, technical architecture, capabilities, applications, limitations, and future directions. By synthesizing insights from academic research, industry developments, and practical implementations, this review offers a holistic understanding of these transformative technologies. This article pulls together insights from trusted sources to give a clear and balanced look at where generative AI and LLMs stand today — and where they might be headed. While the article focuses on current status of LLMs, it is more than clear that in the future, the various applications of LLMs will interact with every aspect our lives, improving and providing new skills which will foster productivity in both personal and professional lives.

II. Methods

A. Research Design

This study employed a systematic review methodology to examine the current state of generative AI and large language models. The systematic approach was chosen to ensure thoroughness, minimize bias, and provide a structured framework for analyzing the diverse and rapidly evolving literature in this field [

20].

B. Search Strategy

A comprehensive search of scientific literature was conducted by using multiple databases including arXiv, IEEE Xplore, ACM Digital Library, Google Scholar, Web of Science, and MDPI. The search was performed between January and March 2025, focusing on literature published between 2017 (marking the introduction of the transformer architecture) and March 2025.

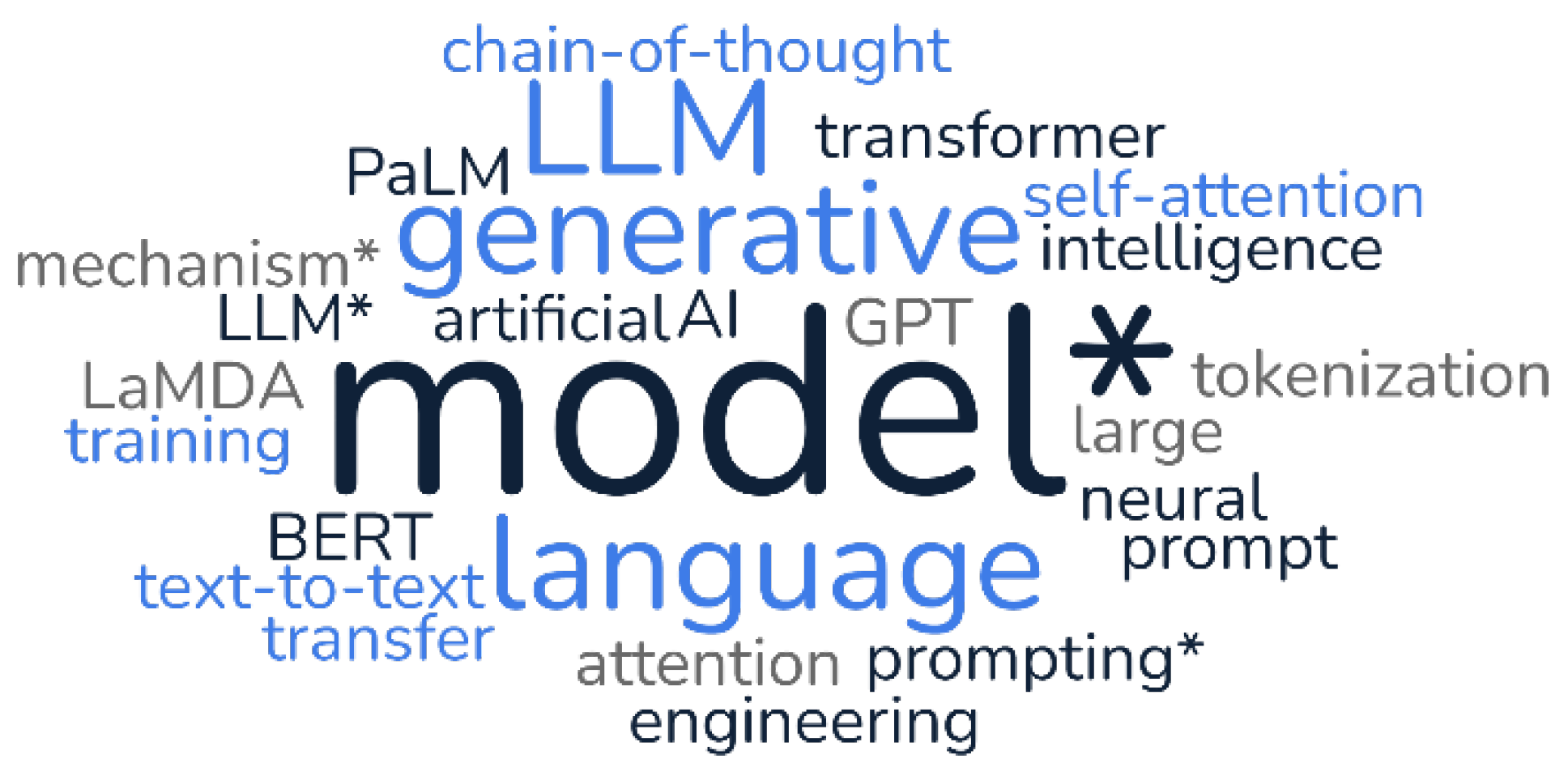

The following search terms were used in various combinations, highlighted in

Figure 1, Word cloud:

“generative AI” OR “generative artificial intelligence”

“large language model*” OR “LLM*”

“transformer model*” OR “attention mechanism*”

“GPT” OR “BERT” OR “LaMDA” OR “PaLM”

“neural language model*”, “self-attention”

“LLM model*”, “LLM training”

“chain-of-thought prompting*”, “prompt engineering”

“tokenization”, “text-to-text transfer”

C. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion Criteria:

Peer-reviewed journal articles, conference proceedings, and technical reports

Literature focusing on generative AI and large language models

Studies examining technical architecture, applications, limitations, or future directions

Publications in English

Literature published between 2017 and March 2025

Websites for institutions (European Commission) and blogs for main LLM providers (OpenAI, DeepSeek, Google)

Exclusion Criteria:

Non-English publications

Opinion pieces without substantial technical or empirical content

Studies focusing exclusively on other AI technologies without significant discussion of generative AI or LLMs

Duplicate publications or multiple reports of the same study

D. Data Extraction and Synthesis

Data extraction was performed using a standardized form that captured the following information:

Publication details (authors, year, journal/conference)

Study objectives and methodology

Key findings and contributions

Technical details of models or architectures discussed

Applications and use cases

Limitations and challenges identified

Future research directions proposed

The extracted data was synthesized using a thematic analysis approach, identifying key themes and patterns across the literature. These themes were organized into categories corresponding to the major sections of this review: historical evolution, technical architecture, applications, limitations and challenges, and future directions.

E. Quality Assessment and Limitations of Review Methodology

The quality of included studies was assessed using criteria adapted from the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [

21]. For technical papers, methodological rigor, clarity of reporting, and significance of contribution were evaluated. For empirical studies, study design, sample size, data collection methods, and analysis techniques were assessed.

Several limitations of selected methodology should be acknowledged. First, the rapid pace of development in generative AI means that some recent advancements may not be reflected in peer-reviewed literature. Second, proprietary details of commercial LLMs are often not fully disclosed in scientific publications, potentially limiting the understanding of state-of-the-art systems. Third, the interdisciplinary nature of the field necessitated searches across multiple databases, which may have resulted in some relevant studies being overlooked.

III. Results

A. Technical Architecture of Generative LLMs

The analysis of the technical approaches of modern LLMs revealed several key architectural components and principles used for these technologies to achieve their capabilities.

2). Components of Modern LLMs

Modern LLMs convert tokens (words or subwords) into numerical representations called embeddings using subword tokenization methods such as Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE) or SentencePiece [

25]. Each transformer block contains a feed-forward neural network that processes the output of the attention mechanism, introducing non-linearity and increasing representational capacity [

26]. Layer normalization stabilizes training and improves convergence by normalizing the activations across features for each example [

27]. Residual connections (skip connections) around each sub-layer facilitate gradient flow during training, especially in deep models [

28].

3). Architectural Variations

The GPT family of models uses a decoder-only transformer architecture with masked self-attention, making the model autoregressive [

29]. BERT uses only the encoder portion of the transformer, allowing bidirectional attention [

1]. T5 (Text-to-Text Transfer Transformer) uses the complete encoder-decoder architecture, framing all NLP tasks as text-to-text problems [

30]. Google’s PaLM and Gemini models introduce architectural innovations for improved scaling and multimodal capabilities [

31].

4). Scaling Properties, Emergent Capabilities and Efficiency Innovations

Research has identified several important scaling laws: performance on language tasks follows a power-law relationship with model size [

13]; performance also scales with the amount of training data, though with diminishing returns [

32]; and training compute (the product of model size and training tokens) is another key factor [

33]. LLMs exhibit emergent abilities—capabilities not present in smaller models but appearing once models reach a certain scale—including in-context learning, chain-of-thought reasoning, and instruction following [

34].

To address the computational demands of large models, researchers have developed various efficiency techniques: sparse attention mechanisms limit each token to attending only to a subset of other tokens [

23]; parameter-efficient fine-tuning methods like LoRA allow for efficient adaptation with minimal parameter updates [

35]; quantization reduces the precision of model weights to decrease memory requirements [

36]; and knowledge distillation transfers knowledge from a large “teacher” model to a smaller “student” model [

37].

B. Applications and Use Cases

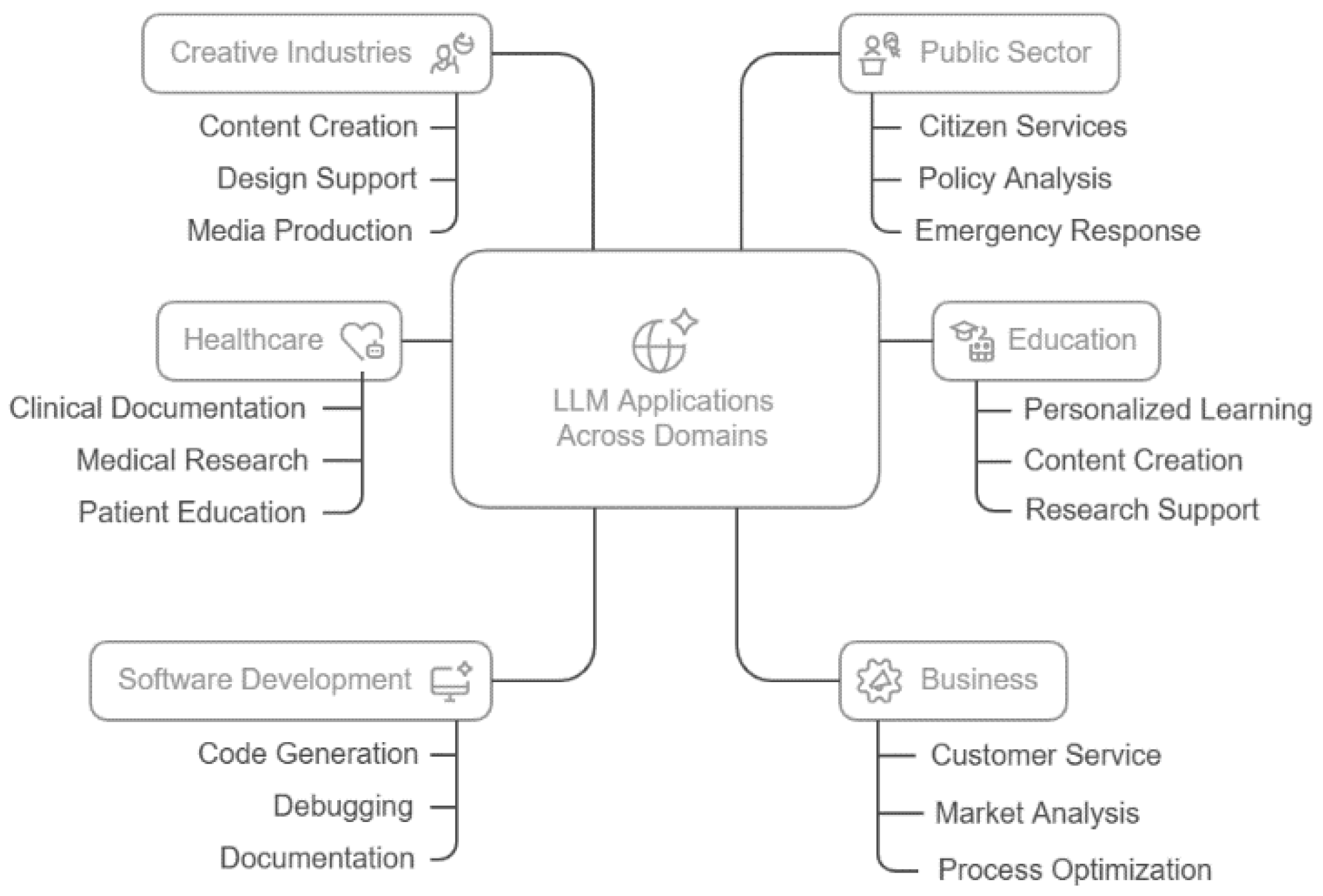

Diverse applications of generative AI and LLMs across multiple domains were discovered, as illustrated in

Figure 2, demonstrating their versatility and transformative potential.

LLMs excel at text summarization and content creation, distilling lengthy documents into concise summaries while preserving key information [

38]. They have significantly advanced machine translation capabilities, supporting communication across language barriers with unprecedented fluency [

39]. The conversational capabilities of LLMs have revolutionized virtual assistants and chatbots, enabling coherent, contextually appropriate dialogues [

40].

LLMs offer unprecedented opportunities for personalized education through adaptive tutoring systems that explain concepts in multiple ways and provide tailored feedback [

41]. Educators leverage LLMs to develop curriculum materials, lesson plans, and educational resources [

42]. In academic contexts, LLMs assist with literature reviews by summarizing research papers and identifying connections between studies [

43].

LLMs assist healthcare professionals with clinical documentation, generating notes, discharge summaries, and referral letters [

7]. They synthesize findings across thousands of studies, identify emerging trends, and summarize evidence-based practices [

44]. Artificial intelligence models can be used in combination with IoT devices to detect different pathologies or to detect early signs of future disorders [

45,

46]. LLMs facilitate improved patient education by generating personalized health information that accounts for a patient’s specific condition and health literacy level [

23].

Programming-focused LLMs generate code snippets, complete partial code, and translate requirements into functional implementations [

8]. They assist with debugging by identifying potential issues in code, suggesting fixes, and explaining the underlying problems [

47]. LLMs can generate comprehensive documentation from code, including function descriptions, parameter explanations, and usage examples [

48].

Enterprises deploy LLM-powered systems to handle customer inquiries, troubleshoot common issues, and provide product information [

6]. LLMs analyze consumer feedback, social media conversations, and market trends to provide businesses with actionable insights [

49]. In industrial settings, LLMs integrate with sensor data and operational metrics to optimize processes and predict maintenance needs [

6].

LLMs support creative professionals in developing narratives, scripts, poetry, and other creative works [

2]. Multimodal LLMs that combine text and image understanding support various design applications [

50]. In music and audio production, specialized LLMs assist with composition, arrangement, and sound design [

51].

Government agencies use LLMs to improve citizen services through more accessible information delivery and streamlined interactions [

6]. LLMs assist policymakers by analyzing large volumes of data, simulating potential policy outcomes, and identifying unintended consequences [

52].During emergencies, LLMs help coordinate response efforts by processing incoming information and facilitating communication between different agencies [

53].

C. Limitations and Challenges

A range of critical limitations and challenges has been identified in generative AI and LLMs, all of which demand attention for responsible development and deployment. The following sections detail these issues, highlighting technical, ethical, regulatory, environmental, and integration aspects.

1). Technical Limitations

LLMs tend generate content that appears plausible but contains factual errors or fabricated information—a phenomenon commonly referred to as “hallucination” [

16]. Current LLMs operate within fixed context windows that constrain their ability to maintain coherence and consistency across long documents or conversations [

23]. Despite their impressive language capabilities, LLMs struggle with complex reasoning, logical consistency, and mathematical accuracy [

54]. State-of-the-art models require enormous computational resources for both training and inference, creating barriers to entry for smaller organizations and researchers [

18].

2). Ethical Concerns

LLMs learn from vast corpora of human-generated text, inevitably absorbing and potentially amplifying biases present in that data [

17]. The development and deployment of LLMs raise significant privacy concerns, particularly in domains like medicine where confidentiality is paramount [

5]. LLMs trained on vast corpora of text raise complex intellectual property questions regarding copyright status of training data and ownership of AI-generated content [

55]. The capabilities of advanced LLMs create potential for various forms of misuse, including generation of misinformation and automated production of harmful content [

19].

3). Regulatory and Compliance Challenges

The rapid advancement of generative AI has outpaced regulatory frameworks, creating uncertainty and compliance challenges across different jurisdictions [

56]. LLMs operate as “black boxes” with billions of parameters, making their decision-making processes opaque and difficult to interpret [

57]. The complexity and autonomy of LLMs complicate traditional accountability frameworks, with unclear responsibility distribution among developers, deployers, and users [

52].

4). Environmental Impact

The training of large language models requires enormous computational resources, resulting in significant energy consumption and carbon emissions [

18]. Beyond training, the ongoing operation of LLMs for inference also consumes significant resources, particularly for high-traffic applications [

58].

5). Implementation and Integration Challenges

Adapting general-purpose LLMs to specific domains presents significant challenges, particularly for specialized fields with domain-specific terminology and knowledge [

5]. Incorporating LLMs into existing technological ecosystems presents numerous integration challenges, including interfacing with legacy systems and ensuring consistent performance [

6]. Evaluating LLM performance presents unique challenges compared to traditional software due to the subjective nature of many language tasks and the impossibility of comprehensive testing across all possible inputs [

59].

D. Future Directions and Emerging Trends

Several promising research directions and emerging trends have been identified that are expected to influence the future development of generative AI and LLMs. The following sections outline key areas of ongoing innovation, highlighting advancements in model architecture, efficiency, domain specialization, reasoning capabilities, ethical AI, regulatory frameworks, and technological integration.

Researchers are exploring architectural innovations beyond transformers, including sparse attention mechanisms, mixture of experts approaches, retrieval-enhanced architectures, and neuro-symbolic approaches [

22]. The integration of multiple modalities—text, images, audio, video, and structured data—represents a significant frontier in LLM development [

50].

As model scaling faces economic and environmental constraints, research into parameter-efficient architectures is accelerating, including parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT), knowledge distillation, quantization and pruning, and neural architecture search [

35]. Innovations in training methodologies aim to reduce computational and data requirements through advances in self-supervised learning, curriculum learning, continual learning, and federated learning [

60].

While general-purpose LLMs demonstrate broad capabilities, specialized models tailored to specific domains are likely to proliferate, including scientific, legal, financial, and healthcare-specific models [

43]. Expanding beyond English-centric development to better serve global populations through multilingual models, cultural contextualization, and local knowledge integration is an important direction [

61].

Addressing current limitations in structured reasoning represents a critical frontier, with improvements to chain-of-thought techniques, integration with external tools, and formal verification methods [

34]. Developing stronger capabilities for understanding causality rather than mere correlation through causal inference, counterfactual reasoning, and temporal reasoning is an active area of research [

62].

Ensuring that AI systems behave in accordance with human values and intentions through constitutional AI, interpretability research, red-teaming, and value alignment is increasingly important [

63]. Addressing issues of bias and fairness through comprehensive frameworks for identifying and mitigating various forms of bias is a critical research direction [

17].

The regulatory environment for AI is rapidly developing, with emerging international standards, risk-based regulation, certification and auditing systems, and industry-led self-regulation initiatives [

56]. Mechanisms to ensure responsible development and deployment through standardized documentation, explainability tools, and audit trails are being developed [

64].

The integration of LLMs with broader technological ecosystems through AI-enabled infrastructure, autonomous agents, Internet of Things integration, and smart city applications represents a frontier of development [

6]. Evolving paradigms for human-AI interaction through collaborative interfaces, augmented creativity, cognitive prosthetics, and personalized AI assistants are emerging.

IV. Discussion

The presented systematic review reveals the remarkable trajectory of generative AI and LLMs from theoretical concepts to transformative technologies with wide-ranging applications. The evolution of these models has been characterized by several key developments: the breakthrough of the transformer architecture with its self-attention mechanism [

12], the scaling of models to unprecedented sizes, and the emergence of capabilities not explicitly programmed [

34]. These developments have enabled applications across diverse domains, from healthcare and education to creative industries and public services.

The technical architecture of modern LLMs, centered around self-attention mechanisms and deep neural networks, has proven remarkably effective at capturing the patterns and structures of human language [

12]. The scaling properties of these models have revealed fascinating relationships between model size, training data, and performance, suggesting pathways for continued advancement through both scaling and architectural innovation [

13].

However, the findings also highlight significant limitations and challenges that must be addressed. Technical constraints such as hallucinations, context window limitations [

23], and reasoning deficiencies [

54] impact the reliability and applicability of LLMs in critical domains. Ethical concerns regarding bias, privacy, intellectual property, and potential misuse needs careful mitigation strategies. Regulatory uncertainties (while some countries tend to liberate AI development, others want to regulate as strict as possible), environmental impacts, and implementation challenges further complicate the landscape of LLMs development [

56].

A. Implications for Research and Practice

The findings suggest several important directions for future research. First, addressing the technical limitations of current LLMs, particularly hallucinations and reasoning limits, requires fundamental advances in model architecture and training methodologies [

10]. While there are new models arising daily, research must be continued, so new ways of LLM development approach should be proposed. Developing more efficient methods to train and deploy (in this particular case, inference) is essential for offering access to these technologies for new people and reducing their environmental impact [

35]. Third, research into interpretability of different concepts and finding new ways how to explain why some models are behaving in a particulate way is critical for addressing the “black box” nature of current systems [

57].

The interdisciplinary nature of challenges associated with LLMs necessitates collaboration across fields including computer science, linguistics, cognitive science, ethics, law, and social sciences [

3].

For people working in the field, this review points out how important it is to have smart, well-planned strategies — ones that really take into account what today’s LLMs can and can’t do. Organizations deploying these technologies should implement robust evaluation frameworks, monitoring systems, and governance structures to ensure responsible use [

64]. Domain-specific adaptation through fine-tuning or retrieval augmentation is essential for applications in specialized fields, like military and medicine.

The development of clear guidelines for human-AI collaboration can maximize the benefits of these technologies while maintaining appropriate human oversight. Educational initiatives to build AI literacy among professionals and the general public are important for enabling informed engagement with these technologies [

41,

61].

B. Ethical Considerations

The general adoption of generative AI and LLMs raises critical ethical questions that require consideration. The potential for these technologies to exacerbate existing inequalities through biased outputs or unequal access demands proactive approaches to fairness and accessibility [

17]. The environmental impact of large-scale AI systems necessitates more sustainable approaches to development and deployment [

18].

Questions of authorship, originality, and intellectual property in the context of AI-generated content challenge traditional legal and cultural frameworks [

55]. The potential for automation to disrupt labor markets requires thoughtful approaches to workforce transition and the development of new roles that leverage human-AI collaboration [

65].

C. Limitations of the Current Review

Several limitations of this review should be acknowledged. First, the rapid pace of development in this field means that some recent advancements may not be fully reflected in the literature analyzed. Second, proprietary details of commercial LLMs are often not fully disclosed, potentially limiting understanding of state-of-the-art systems. Third, focus on English-language publications may have excluded valuable insights from non-English research communities.

V. Conclusions

This systematic review has comprehensively examined the evolution, technical architecture, applications, limitations, and future directions of generative AI and Large Language Models. The findings demonstrate the transformative potential of these technologies across diverse domains, while also highlighting significant challenges that must be addressed for responsible development and deployment.

The technical architecture of modern LLMs, centered around self-attention mechanisms and deep neural networks, has enabled unprecedented capabilities in language understanding and generation. These technologies already demonstrate considerable promise across a wide variety of fields, including healthcare, education, software development, creative work, and public services. Their adaptability is clear from the way they’re being used to optimize medical research, personalize learning experiences, generate innovative software solutions, spark new forms of art and media, and streamline government operations.

At the same time, there are important limitations which can’t be overlooked. On the technical side, issues like model hallucinations and limited reasoning capabilities represent real challenges, often undermining the reliability of the systems and the adoption of such systems. On the ethics side, there are still big concerns about bias, data privacy, and making sure everyone has fair access. Figuring out how to regulate these technologies is still an open question, and on top of that, their environmental impact — since they use a lot of computing power — adds even more complexity. Putting these systems into real-world use isn’t easy either, with challenges like high costs and the need to train people to work with them. Tackling all this will take teamwork between tech folks, policymakers, and others, along with ongoing research to keep pushing the limits of what these models can actually do.

New breakthroughs in how these models are built could make them a lot more accurate and efficient, while also using less energy. Improving how well they “reason” could help fix some of the current problems—like when they give wrong or confusing answers. It also makes sense to fine-tune models for specific industries or tasks, so the results they give are more accurate and useful. On top of that, combining LLMs with other types of AI—like computer vision or reinforcement learning—might open the door to totally new and unexpected applications.

These technologies aren’t just about technical concepts — they’re changing the way we live, work, and connect with each other. As LLMs become part of our everyday lives — helping students learn, supporting doctors, powering apps, inspiring creativity, and even helping write this review — their impact on society and culture keeps growing. To make sure that impact is a positive one, we need to build in ethical values, fairness, and accountability from the ground up. And we also need smart governance — laws, policies, and systems that put people first and protect things like privacy, equality, and responsible innovation.

Generative AI and Large Language Models represent a groundbreaking convergence of potential and complexity. If we make the most of what these tools can do—while keeping a close eye on their flaws and the bigger picture—we’ve got a real opportunity to shape them into something that truly helps people and benefits society as a whole. What is worth mentioning is that if we compare the evolution of smartphones—taking the launch of the first iPhone in 2007 as a reference point—with the launch of ChatGPT in 2022, and we extrapolate based on how far smartphone technology has come, it becomes clear that the next AI revolution is a matter of years, not decades.

Acknowledgment

During the preparation of this review, the author used Manus for the purposes of summarization and text-generation for some general statements. The author has reviewed and edited the output and takes full responsibility for the content of this publication.

References

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.-W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1810.04805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.B.; et al. Language Models are Few-Shot Learners. arXiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bommasani, R.; et al. On the Opportunities and Risks of Foundation Models. arXiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radford, A.; Wu, J.; Child, R.; Luan, D.; Amodei, D.; Sutskever, I. Language models are unsupervised multitask learners. OpenAI Blog. Available online: https://cdn.openai.com/better-language-models/language_models_are_unsupervised_multitask_learners.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Yu, P.; Xu, H.; Hu, X.; Deng, C. Leveraging Generative AI and Large Language Models: A Comprehensive Roadmap for Healthcare Integration. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salierno, G.; Leonardi, L.; Cabri, G. Generative AI and Large Language Models in Industry 5.0: Shaping Smarter Sustainable Cities. Encyclopedia 2025, 5, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, M. ChatGPT Utility in Healthcare Education, Research, and Practice: Systematic Review on the Promising Perspectives and Valid Concerns. Healthcare 2023, 11, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; et al. Evaluating Large Language Models Trained on Code. arXiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rombach, R.; Blattmann, A.; Lorenz, D.; Esser, P.; Ommer, B. High-Resolution Image Synthesis with Latent Diffusion Models. 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA; 2022; pp. 10674–10685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuster, K.; Poff, S.; Chen, M.; Kiela, D.; Weston, J. Retrieval Augmentation Reduces Hallucination in Conversation. Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2021; Association for Computational Linguistics: Punta Cana, Dominican Republic, 2021; pp. 3784–3803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengio, Y.; Ducharme, R.; Vincent, P. A neural probabilistic language model. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, in NIPS’00; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000; pp. 893–899. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; et al. Attention Is All You Need. arXiv 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, J.; et al. Scaling Laws for Neural Language Models. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2001.08361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touvron, H.; et al. LLaMA: Open and Efficient Foundation Language Models. arXiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeepSeek-AI; et al. DeepSeek-R1: Incentivizing Reasoning Capability in LLMs via Reinforcement Learning. arXiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, E.M.; Gebru, T.; McMillan-Major, A.; Shmitchell, S. On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big? In Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, Virtual Event; ACM: Canada; pp. 610–623. [CrossRef]

- Bolukbasi, T.; Chang, K.-W.; Zou, J.; Saligrama, V.; Kalai, A. Man is to Computer Programmer as Woman is to Homemaker? Debiasing Word Embeddings. arXiv 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, D.; et al. Carbon Emissions and Large Neural Network Training. arXiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamkin, A.; Brundage, M.; Clark, J.; Ganguli, D. Understanding the Capabilities, Limitations, and Societal Impact of Large Language Models. arXiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; The PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Systematic Review Checklist. 2018. Available online: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/systematic-review-checklist/ (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Kitaev, N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Levskaya, A. Reformer: The Efficient Transformer. arXiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltagy, I.; Peters, M.E.; Cohan, A. Longformer: The Long-Document Transformer. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.05150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, P.; Uszkoreit, J.; Vaswani, A. Self-Attention with Relative Position Representations. In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 2 (Short Papers); Association for Computational Linguistics: New Orleans, Louisiana, 2018; pp. 464–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sennrich, R.; Haddow, B.; Birch, A. Neural Machine Translation of Rare Words with Subword Units. In Proceedings of the 54th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers); Association for Computational Linguistics: Berlin, Germany; pp. 1715–1725. [CrossRef]

- Hendrycks, D.; Gimpel, K. Gaussian Error Linear Units (GELUs). arXiv 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ba, J.L.; Kiros, J.R.; Hinton, G.E. Layer Normalization. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1607.06450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition; 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, A.; Narasimhan, K.; Salimans, T.; Sutskever, I. Improving language understanding by generative pre-training. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Raffel, C.; et al. Exploring the Limits of Transfer Learning with a Unified Text-to-Text Transformer. arXiv 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhery, A.; et al. PaLM: Scaling Language Modeling with Pathways. arXiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, J.; et al. Training Compute-Optimal Large Language Models. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.15556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henighan, T.; et al. Scaling Laws for Autoregressive Generative Modeling. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.14701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; et al. Chain-of-thought prompting elicits reasoning in large language models. In Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, in NIPS ’22; Curran Associates Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, E.J.; et al. LoRA: Low-Rank Adaptation of Large Language Models. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2106.09685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Mao, H.; Dally, W.J. Deep Compression: Compressing Deep Neural Networks with Pruning, Trained Quantization and Huffman Coding. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1510.00149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinton, G.; Vinyals, O.; Dean, J. Distilling the Knowledge in a Neural Network. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1503.02531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Saleh, M.; Liu, P. Pegasus: Pre-training with extracted gap-sentences for abstractive summarization. In International conference on machine learning; PMLR, 2020; pp. 11328–11339. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, M.; et al. Google`s Multilingual Neural Machine Translation System: Enabling Zero-Shot Translation. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 2017, 5, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roller, S.; et al. Recipes for building an open-domain chatbot. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.13637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Z.; et al. LLM Agents for Education: Advances and Applications. arXiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, X.; et al. ERNIE-M: Enhanced Multilingual Representation by Aligning Cross-lingual Semantics with Monolingual Corpora. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2012.15674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltagy, I.; Lo, K.; Cohan, A. SciBERT: A Pretrained Language Model for Scientific Text. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1903.10676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteva, A.; et al. CO-Search: COVID-19 Information Retrieval with Semantic Search, Question Answering, and Abstractive Summarization. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.09595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, J.C.L.; Wong, V.; Li, K. Generative Pre-Trained Transformer-Empowered Healthcare Conversations: Current Trends, Challenges, and Future Directions in Large Language Model-Enabled Medical Chatbots. BioMedInformatics 2024, 4, 837–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciubotaru, B.-I.; et al. Frailty Insights Detection System (FIDS)—A Comprehensive and Intuitive Dashboard Using Artificial Intelligence and Web Technologies. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svyatkovskiy, A.; Deng, S.K.; Fu, S.; Sundaresan, N. IntelliCode compose: code generation using transformer. In Proceedings of the 28th ACM Joint Meeting on European Software Engineering Conference and Symposium on the Foundations of Software Engineering, Virtual Event; ACM: USA, 2020; pp. 1433–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, S.; Konstas, I.; Cheung, A.; Zettlemoyer, L. Summarizing Source Code using a Neural Attention Model. In Proceedings of the 54th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers); Association for Computational Linguistics: Berlin, Germany, 2016; pp. 2073–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grootendorst, M. BERTopic: Neural topic modeling with a class-based TF-IDF procedure. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.05794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, A.; Dhariwal, P.; Nichol, A.; Chu, C.; Chen, M. Hierarchical Text-Conditional Image Generation with CLIP Latents. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2204.06125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawthorne, C.; et al. Enabling Factorized Piano Music Modeling and Generation with the MAESTRO Dataset. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1810.12247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amodei, D.; Olah, C.; Steinhardt, J.; Christiano, P.; Schulman, J.; Mané, D. Concrete Problems in AI Safety. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1606.06565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; He, J.; Chen, K.; Zhou, Y.; Tang, Z. Collaborative filtering and deep learning based recommendation system for cold start items. Expert Syst. Appl. 2017, 69, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrycks, D.; et al. Measuring Mathematical Problem Solving With the MATH Dataset. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2103.03874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemley, M.A.; Casey, B. Fair Learning. SSRN Electron. J. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Comission. Proposal for a Regulation laying down harmonised rules on artificial intelligence. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/proposal-regulation-laying-down-harmonised-rules-artificial-intelligence (accessed on 4 January 2025).

- Doshi-Velez, F.; Kim, B. Towards A Rigorous Science of Interpretable Machine Learning. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1702.08608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strubell, E.; Ganesh, A.; McCallum, A. Energy and Policy Considerations for Deep Learning in NLP. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1906.02243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guu, K.; Lee, K.; Tung, Z.; Pasupat, P.; Chang, M.-W. REALM: Retrieval-Augmented Language Model Pre-Training. arXiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengio, Y.; Louradour, J.; Collobert, R.; Weston, J. Curriculum learning. In Proceedings of the 26th Annual International Conference on Machine Learning; ACM: Montreal Quebec Canada, 2009; pp. 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, N.T.; Moore, P.; Thanh, D.H.V.; Pham, H.V. A Generative Artificial Intelligence Using Multilingual Large Language Models for ChatGPT Applications. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengio, Y.; et al. A Meta-Transfer Objective for Learning to Disentangle Causal Mechanisms. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1901.10912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leike, J.; Krueger, D.; Everitt, T.; Martic, M.; Maini, V.; Legg, S. Scalable agent alignment via reward modeling: a research direction. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1811.07871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M.; et al. Model Cards for Model Reporting. arXiv 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D.; Restrepo, P. Automation and New Tasks: How Technology Displaces and Reinstates Labor. J. Econ. Perspect. 2019, 33, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).