1. Introduction

Conflict-affected regions face severe barriers to inclusive education, disproportionately affecting children with disabilities. In Northwest Cameroon, where the Anglophone crisis has closed over 80% of schools since 2016 and displaced 700,000 (

learners International Crisis Group, 2021), these children face compounded marginalization due to infrastructural collapse, cultural stigma, and the absence of disability-adapted learning frameworks. Digital Assistive Technologies (DATs) have emerged as potential solutions for fostering literacy equity. For example,

Schiavo et al. (

2021) demonstrated that integrating read-aloud technology with eye-tracking can significantly improve reading comprehension in children with reading disabilities. However, their adoption in conflict zones remains poorly understood. In Northwest Cameroon, barriers such as erratic electricity, limited teacher training, and sociocultural resistance hinder implementation. Many assistive devices lack localized language options, rendering them ineffective in regions where indigenous languages dominate. Additionally, political instability fosters public distrust toward externally introduced technologies. For instance, research by

Gupta et al. (

2020) highlights that language barriers significantly impede technology adoption in agricultural settings, emphasizing the importance of culturally and linguistically tailored solutions. Furthermore, studies have shown that political instability negatively impacts innovation and technology adoption, as uncertainty can deter investment and acceptance of new technologies (

Coccia, 2020).

Despite international frameworks like the UNCRPD (Article 11) and SDG 4, existing research overwhelmingly focuses on stable, high-income settings (Alper and Goggin, 2017). This neglect has contributed to what (

Tanyi and Ngum, 2020) calls “educational collateral damage,” leaving children with disabilities in crisis settings without viable literacy pathways. Furthermore, simplistic techno-optimist narratives often overlook structural inequalities and cultural dynamics that influence DAT adoption in conflict zones.

This study addresses these gaps by examining how DATs such as text-to-speech applications, braille e-readers, and offline literacy software can improve literacy for children with disabilities in conflict settings. Focusing on Bamenda, Kumbo, Ndop, and Jakiri, the study pursues four interrelated objectives:

Evaluate the effectiveness of DATs in enhancing literacy for children with disabilities in Northwest Cameroon.

Identify barriers to DAT adoption, including infrastructure gaps, cultural stigma, and inadequate teacher training.

Analyze caregivers’ perspectives on inclusive education and their experiences using DATs amid conflict.

Develop conflict-sensitive policy recommendations, aligning with the UNCRPD’s mandate for “reasonable accommodation” in emergencies.

By situating DATs within the socio-political and cultural realities of the Anglophone crisis, this research challenges the assumption that technology alone can drive inclusion. It highlights practical, context-responsive pathways to literacy equity, ensuring that children with disabilities in crisis-affected regions are not left behind.

2. Literature Review

The intersection of digital and assistive technologies (DATs), disability inclusion, and education in conflict zones remains an emerging yet critically important field of scholarly inquiry. While existing literature highlights the transformative potential of DATs in promoting literacy for children with disabilities, significant gaps persist in understanding their applicability, sustainability, and ethical implications in fragile, resource-constrained contexts. This review synthesizes global evidence on DAT-driven literacy interventions, critiques their methodological and theoretical assumptions, and situates this study within broader debates on equity, conflict-sensitive design, and decolonial praxis in humanitarian education.

Extensive research accentuates the efficacy of digital assistive technologies (DATs) in improving literacy outcomes for children with disabilities in high-income, stable environments. For example, screen readers such as JAWS and NVDA—and related text-to-speech applications—have been associated with improvements in reading fluency and comprehension for students with visual impairments and dyslexia (

Dell, Newton, & Petroff, 2017). Similarly, gamified mobile platforms such as GraphoGame have been shown to enhance phonological awareness in children with intellectual disabilities through adaptive, interactive interfaces (

Richardson and Lyytinen, 2014). Meta-analyses indicate medium-to-large effect sizes (0.45–0.68) for DATs in literacy outcomes (Alper and Raharinirina, 2020), affirming their potential as effective educational tools.

However, several methodological and contextual limitations constrain the broader applicability of these findings. First, the majority of these studies assume universal access to stable internet connectivity, reliable electricity, and digital literacy among teachers and caregivers assumptions that do not hold in conflict-affected regions (

van Dijk, 2020). Second, efficacy metrics are often narrowly defined, focusing on technical outputs like reading speed or word recognition while neglecting holistic outcomes such as self-efficacy, community inclusion, or long-term engagement (Grech and Soldatić, 2021). Third, many DAT designs reflect Global North biases, prioritizing dominant languages such as English and French over indigenous languages, and neglecting users with complex needs such as neuromotor impairments (

Linda Tuhiwai Smith,1999). These gaps highlight the need for context-specific, participatory approaches to DAT design and implementation.

In conflict-affected regions, structural violence, defined by Mireille (2015) as systemic inequities embedded within political, economic, and social institutions, exacerbates the educational exclusion of children with disabilities. Schools are often deliberately destroyed, teachers face displacement, and humanitarian aid efforts remain fragmented or insufficient (

Dryden-Peterson, 2022). Digital Aid Technologies (DATs) are frequently framed within this precarious landscape as quick-fix solutions for disrupted education systems. For instance, UNICEF’s Learning Passport platform, designed to deliver offline-accessible literacy content, has been piloted in Syrian refugee camps with mixed results. While promising in theory, UNESCO’s 2023 Global Education Monitoring Report notes that only 12% of children with disabilities accessed the platform due to a lack of compatibility with assistive features, highlighting how DATs often fail to prioritize universal design principles (p. 147). This aligns with critiques by

Castillo and Zelezny-Green (

2022), who argue that such technologies prioritize scalability over inclusivity, overlooking infrastructural barriers (e.g., electricity shortages) and intersectional vulnerabilities like disability in refugee contexts. Scholarship on DATs in conflict zones is further undermined by techno-optimist narratives that equate technological deployment with meaningful inclusion.

Schools are often deliberately destroyed, teachers face displacement, and humanitarian aid efforts remain fragmented or insufficient (Nkwelle, 2021). Within this precarious landscape, Digital Aid Technologies (DATs) are frequently framed as quick-fix solutions for disrupted education systems. For instance, mobile learning initiatives in South Sudan focused heavily on distributing tablets without adequately training teachers to use assistive software, rendering many devices underutilized or obsolete (Muyoya et al., 2021). Similarly, audiobook programs in Yemen failed to account for cultural stigmas associated with auditory learning and the practical challenges of frequent power outages (Al-Haddad, 2022). Such cases highlight the epistemic erasure of end-user voices, particularly those of children with disabilities and their caregivers, perpetuating cycles of “innovation without inclusion” (

Grech, 2016, p. 10).

The deployment of DATs in conflict zones is deeply intertwined with colonial legacies of humanitarian intervention. Cameroonian critical scholar

Nyamnjoh (

2017) argues that many Western-designed technologies impose Eurocentric notions of “normalcy” and pathologize local communication and learning practices. For example, speech-generating devices (SGDs) preloaded with Global North accents alienate users in multilingual regions like Cameroon, where over 200 indigenous languages are spoken (

Chibaka and Atanga, 2022). Similarly, the dominance of French in braille instruction marginalizes Anglophone communities in Northwest Cameroon, exacerbating existing sociopolitical tensions (Nkwelle and Fogwe, 2023).

Moreover, DAT implementation often mirrors extractive aid practices, where external agencies introduce technologies without establishing sustainable infrastructure or fostering local ownership (Mbarika et al., 2020). In the Democratic Republic of Congo, for example, 68% of donated DATs became nonfunctional within six months due to inadequate repair networks (Tshikala et al., 2021). Such “technological dumping” not only squanders resources but also reinforces dependency, contradicting the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD)’s mandate for local agency and participation (Article 32). Addressing these systemic issues requires reimagining DAT deployment through decolonial and community-driven frameworks.

Emerging research highlights the importance of conflict-sensitive DAT models that prioritize the lived experiences of children with disabilities in humanitarian settings. Cameroonian scholars

Tambo and Nkeng (

2022) outline four key principles for inclusive education in crises: Accessibility, Adaptability, Affordability, and Agency. This framework provides a structured approach for co-designing technologies with end-users and integrating them into broader community resilience strategies. In Somalia, for example, a participatory project involving deaf children and local sign-language experts successfully developed a pictogram-based literacy app, increasing reading engagement by 40% (Abdullahi & Farah, 2023). Similarly, low-tech solutions like solar-powered audiobooks and tactile flashcards have proven effective in Ukraine’s conflict zones, where digital infrastructure is frequently disrupted (Koval et al., 2023).

Despite these advances, critical gaps remain. Few studies address the intersectional traumas of war, such as the psychological impacts of displacement and PTSD on children with disabilities (Khan et al., 2022). Additionally, the role of caregivers, who are often pivotal in facilitating DAT use, is underexamined in existing research (

Atanga, 2021). Ethical dilemmas also persist: DATs that collect user data risk exposing children to surveillance by armed groups, particularly in highly militarized regions like Northwest Cameroon (

Asongu & Nwachukwu, 2021). Addressing these gaps requires a praxis-oriented approach that integrates academic rigor, community knowledge, and policy advocacy.

Northwest Cameroon’s Anglophone crisis provides a critical lens for examining DATs’ role in inclusive literacy. Since 2016, the protracted conflict between state forces and separatist groups has displaced over 1.2 million people, including an estimated 450,000 children with disabilities (UN OCHA, 2023). Existing studies on Cameroon’s education crisis primarily focus on generic access barriers (

Mbibeh, 2021), neglecting the specific challenges faced by children with disabilities. For example, Tambo (2023) critiques emergency education programs for their reliance on French-language e-learning platforms, which exclude 89% of Anglophone children with visual impairments (p. 78). This study addresses three key empirical gaps:

African DAT research disproportionately centers Kenya and South Africa (Okyere, 2022), neglecting conflict zones like Cameroon, where 85% of schools are nonfunctional (Nkwelle, 2023). Participatory design remains rare, sidelining children with disabilities as co-creators (

Atanga, 2021), while intersectional barriers (disability, gender, displacement) are understudied (

Azoh, 2022;

Mbibeh, 2023). This study challenges top-down models by centering Northwest Cameroonian voices, aligning with decolonial frameworks privileging local epistemologies (

Nyamnjoh, 2017) and the UNCRPD’s “nothing about us without us” mandate. For example, Chibaka’s (2022) sign-language app, co-designed with deaf communities, boosted literacy by 54%, demonstrating community-driven DAT efficacy in crises.

4. Findings

This study’s findings reveal both the transformative potential and systemic limitations of digital and assistive technologies (DATs) in fostering inclusive literacy for children with disabilities amid Northwest Cameroon’s protracted Anglophone crisis. Grounded in a disability justice lens (

Piepzna-Samarasinha, 2018) and critical conflict analysis, the results stress how infrastructural collapse, neoliberal aid logic, and colonial legacies of exclusion mediate DATs’ efficacy. Below, we present a layered study of the key themes, supported by triangulated qualitative and quantitative data.

Table 2.

Digital Assistive Technologies (DATs) and Educational Access Amidst the North West Anglophone Crisis in Cameroon.

Table 2.

Digital Assistive Technologies (DATs) and Educational Access Amidst the North West Anglophone Crisis in Cameroon.

| Stakeholder Group |

Number (%) |

Key Characteristics |

Primary Barriers to DAT Adoption |

Effectiveness of Selected DATs |

Policy Recommendations and Strategies |

| Children with Disabilities |

50 (45.5%) |

Age 8–17; sensory, physical, and cognitive impairments |

Infrastructure deficits (92%)—≤3 hours daily electricity |

Solar-Powered Audiobooks: 40% comprehension improvement |

Decolonial Design Standards, humidity-resistant devices (NGOs, engineers) |

| Caregivers |

30 (27.3%) |

70% female; 80% rural residents |

Economic constraints (63%)—Braille displays cost 5 months’ income |

Braille E-Readers: 28% comprehension improvement |

Gender-Responsive Support—mobile cash transfers (Govt, NGOs) |

| Teachers |

20 (18.2%) |

60% displaced; 12% trained in DATs |

Teacher training gaps (77%)—Only 23% were formally trained |

Speech-to-Text Apps: 33% comprehension improvement |

Trauma-Informed Training—integrating DATs with art therapy (Psychologists, Educators) |

| NGO Staff |

10 (9.1%) |

50% international; 50% local organizations |

Security risks (22%)—Devices confiscated by armed groups |

N/A |

Community Repair Collectives—mobile technician training (Universities, NGOs) |

The table provides a detailed analysis of Digital Assistive Technologies (DATs) in the conflict-affected North West region of Cameroon, highlighting adoption trends, barriers, effectiveness, and policy recommendations. While it sheds light on the role of DATs in addressing educational challenges for children with disabilities, gaps in infrastructure, economic access, and teacher preparedness hinder their impact.

4.1. Stakeholder Demographics: Challenges at the Intersection of Disability and the Anglophone Conflict

The protracted conflict in the Anglophone regions, particularly in the North West Region, has severely disrupted the lives of diverse stakeholders, including children with disabilities, caregivers, teachers, and NGOs. The conflict has amplified structural inequalities, eroded access to education, and marginalized those already at the periphery of social support systems. This section explores the challenges these groups face, shaped by systemic neglect and ongoing conflict.

4.1.1. Children with Disabilities: Marginalized Victims of the Anglophone Conflict

Exclusion and Linguistic Marginalization

The ongoing Anglophone conflict in the North West Region of Cameroon has exacerbated the structural marginalization of children with disabilities, rendering them among the most educationally disenfranchised populations. In this study, they constitute 45.5% of participants, yet their access to education is severely obstructed by the compounded effects of armed violence, systemic exclusion, and the erosion of institutional support mechanisms. The targeted destruction of schools, the displacement of educators, and the fragmentation of humanitarian interventions have collectively dismantled the region’s already fragile educational infrastructure. However, for children with disabilities, these disruptions are further intensified by the absence of adaptive learning technologies, inaccessible pedagogical frameworks, and entrenched linguistic hegemony that continue to shape Cameroon’s postcolonial educational landscape.

For instance, a visually impaired 12-year-old girl in Bamenda described how audio-based learning platforms initially “allowed her to dream of possibilities.” Yet, the prevalence of French-language content, a vestige of Cameroon’s colonial-era educational policies, not only alienated her but also entrenched epistemic violence by restricting access to linguistically and culturally relevant educational materials. This phenomenon is emblematic of a broader structural asymmetry within the national education system, wherein Francophone-dominated curricula systematically marginalize Anglophone learners, particularly those with disabilities. The intersection of linguistic exclusion, disability discrimination, and conflict-induced displacement creates a multi-layered barrier that fundamentally impedes the realization of equitable educational access.

Addressing these systemic disparities necessitates a paradigm shift in policy formulation and humanitarian intervention. There is an urgent need for conflict-sensitive, disability-inclusive, and linguistically responsive education strategies that recognize the unique vulnerabilities of children with disabilities in conflict zones. This includes the co-creation of accessible digital learning platforms, the localization of educational content in Indigenous and Anglophone dialects, and the integration of inclusive pedagogies that transcend colonial epistemologies. Without such structural transformations, children with disabilities in the North West Region will remain perpetually marginalized, deprived not only of education but also of their fundamental right to epistemic and linguistic justice.

Disruption of Education

The Anglophone conflict has precipitated a large-scale educational crisis, producing what Mbibeh (2022) characterizes as a “generation of educational refugees.” The systematic destruction, repurposing, and abandonment of schools across the North West Region have severely curtailed access to formal education, disproportionately affecting already marginalized groups, particularly children with disabilities. Beyond the immediate physical devastation of learning environments, the conflict has induced a protracted institutional paralysis, wherein the displacement of educators, the erosion of state oversight, and the fragmentation of humanitarian interventions collectively exacerbate educational exclusion.

While Digital Assistive Technologies (DATs) present a transformative potential for bridging accessibility gaps, their deployment within conflict zones remains fraught with systemic challenges. Unreliable digital infrastructure, intermittent electricity supply, and the pervasive insecurity of the region significantly undermine their effectiveness. Moreover, the highly securitized nature of digital interventions, including government-imposed internet shutdowns and surveillance measures, further constrains the feasibility of DAT-based educational frameworks. In this volatile context, children with disabilities not only face physical and infrastructural barriers to learning but are also subjected to the compounded effects of technological inaccessibility, political instability, and institutional neglect, rendering their right to education increasingly precarious. Addressing these intersecting challenges necessitates a multidimensional policy response that integrates conflict-sensitive, disability-inclusive, and infrastructure-resilient strategies to safeguard educational continuity for the most vulnerable learners.

4.1.2. Caregivers: Struggling Between Survival and Support

Economic Challenges

Caregivers, who comprise 27.3% of stakeholders in this study, are ensnared in a precarious balancing act between securing their children’s education and ensuring the survival of their families amidst the enduring turmoil of the Anglophone conflict. The economic hardships exacerbated by the protracted conflict have created formidable barriers to educational access, particularly for families of children with disabilities. A key obstacle is the inability of many caregivers to afford essential assistive technologies, which are critical for enabling effective learning. As one caregiver poignantly articulated, “We want to teach our children, but we can barely afford food.” This stark statement emphasizes the dire socioeconomic conditions faced by these families, where basic survival needs overwhelmingly take precedence over educational investments.

The economic devastation wrought by the conflict, particularly the Anglophone conflict, has exacerbated the already high levels of poverty, further entrenching the socioeconomic divide. Even subsidized Digital Assistive Technologies (DATs), which hold potential to alleviate some of these educational inequities, are rendered largely inaccessible to most families due to the inflationary pressures, disrupted supply chains, and collapsed local economies. This economic marginalization not only restricts access to critical learning tools but also compounds the vulnerability of caregivers, who are forced to make heartbreaking trade-offs between their children’s educational needs and their immediate survival. Consequently, the intersection of economic deprivation and conflict-induced instability serves as a primary determinant in perpetuating the educational exclusion of children with disabilities, necessitating urgent interventions that address both socioeconomic inequalities and educational access in conflict zones.

Erosion of Support Networks

The Anglophone conflict has precipitated widespread displacement, forcing families into Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) camps and resulting in the fracturing of traditional communal caregiving systems that are central to the social fabric of African societies (Oyẹwùmí, 1997). This disruption of social networks has left caregivers, particularly those raising children with disabilities, devoid of the community-based support structures that have historically provided critical emotional, social, and practical assistance in caregiving. The absence of these vital support systems exacerbates the already complex challenges these families face in a conflict zone, where access to resources and services is severely constrained.

To address these systemic gaps, it is imperative that interventions prioritize the reconstruction of community support networks within IDP settings and other conflict-affected regions. This entails not only restoring basic social cohesion but also rebuilding caregiver networks that can offer emotional and logistical support, thereby alleviating some of the burdens associated with raising children with disabilities in these precarious environments.

4.1.3. Teachers: Underequipped Frontline Educators

Lack of Training and Resources

Teachers, who represent 18.2% of stakeholders in this study, are pivotal in the successful implementation and utilization of Digital Assistive Technologies (DATs), which hold the potential to significantly enhance educational access for children with disabilities in conflict zones. However, a striking 23% of teachers reported having received formal training in the use of these technologies, leaving a significant proportion unable to harness the full potential of these tools in the classroom. As one teacher from Kumbo poignantly remarked, “We are given devices but no training. They become glorified blackboards.” This sentiment encapsulates the widespread frustration within the teaching community, where digital devices, intended to facilitate inclusive learning, are rendered ineffective due to insufficient professional development and a lack of support infrastructure.

The insufficient training and the broader lack of resources reflect a deeper, systemic issue: the marginalization of the Anglophone regions, where public services, including education, have been progressively undermined as a consequence of both political neglect and the disruption of state governance due to the ongoing conflict (

Konings and Nyamnjoh, 1997). The failure to provide adequate training and resources for educators not only hinders the effective deployment of DATs but also perpetuates the widening educational disparities between the Anglophone and Francophone regions. In this context, the absence of targeted professional development initiatives and resource allocation reinforces the structural inequities in the education system, rendering the deployment of innovative educational technologies largely ineffective and inaccessible to the very students who stand to benefit most. Therefore, addressing the lack of training and resources requires a comprehensive overhaul of education policy in the Anglophone regions, focusing not only on infrastructure rebuilding but also on teacher empowerment, to ensure that DATs are used to their fullest potential in fostering inclusive education.

Conflict-Induced Shortages

The ongoing Anglophone conflict has significantly exacerbated teacher shortages in the North West Region of Cameroon, as many educators have been forced to flee to safer areas, thereby precipitating a severe disruption in the delivery of education. This has led to the diminution of qualified teaching staff within schools, leaving educational institutions increasingly dependent on undertrained, often unqualified volunteers. The reliance on such volunteers not only undermines the pedagogical quality of instruction but also significantly impedes the capacity of schools to provide inclusive education, particularly for children with disabilities who require specialized teaching methodologies.

The erosion of the formal teaching workforce, coupled with the inadequate training of replacement staff, deepens the urgent need for targeted teacher training programs that integrate both technical expertise in the use of assistive technologies and pedagogical competencies tailored to the needs of children with disabilities. These programs must prioritize the development of comprehensive skill sets that equip educators to navigate the challenges of both conflict-induced instability and the increasingly diverse learning needs within their classrooms. Addressing these deficits in teacher preparedness is essential not only for improving the quality of education but also for ensuring that the educational needs of children with disabilities are met with sensitivity, efficacy, and resilience. Such interventions are vital to fostering educational equity in a region grappling with the dual crises of conflict and systemic marginalization.

4.1.4. NGOs: Misaligned Agendas and Implementation Gaps

Challenges in Localization

Non-governmental organizations (NGOs), representing 9.1% of stakeholders in this study, play a central role in the deployment of Digital Assistive Technologies (DATs) in conflict-affected regions. However, their efforts are often impeded by a disjunction between donor priorities and the on-the-ground realities of the North West Region, a situation that exacerbates the challenges faced by vulnerable populations, particularly children with disabilities. One key issue is the mismatch between the technical specifications of imported assistive devices and the environmental conditions in the region, such as high humidity and dust, which frequently undermine the functionality and durability of these technologies. For example, imported Braille devices, while technically proficient, often fail to perform adequately in the region’s unique climatic conditions, rendering them ineffective for their intended purpose. As one NGO worker succinctly put it, “We need localized solutions, not imported fixes.”

This statement underlines a critical gap in the design and implementation of DATs, the lack of local adaptation. It highlights the urgent need for the co-design of assistive technologies that are specifically tailored to the environmental, cultural, and infrastructural contexts of the North West Region. Localized solutions should not only address the technical feasibility of such devices in extreme climates but also align with cultural norms, community practices, and language diversity. The failure to integrate these elements into DAT development often results in the ineffectiveness of external interventions, which may not resonate with local needs or usage patterns. Therefore, the development and deployment of assistive technologies must involve collaborative, context-specific design processes that bridge the gap between international innovation and local knowledge, ensuring that technological interventions are both culturally relevant and environmentally sustainable. Scholars like

Nyamnjoh (

2017) emphasize that development initiatives in Cameroon must align with local contexts. Collaborative approaches involving community input are critical to ensuring the sustainability of DATs. By prioritizing local realities, NGOs can better address the unique challenges faced by conflict-affected populations in the Anglophone regions.

4.1.5. Efficacy and Barriers of DAT Deployment

Barriers to Inclusive Digital Assistive Technologies in Conflict-Affected Anglophone Regions

Despite the potential of Digital Assistive Technologies (DATs) to enhance learning outcomes for children with disabilities, several structural barriers hinder their effectiveness in the Anglophone conflict zone. Linguistic alienation remains a significant issue, as the dominance of French-language content excludes many Anglophone users, with 67% of participants reporting a sense of detachment. A 14-year-old boy described this disconnect as feeling “like it’s from a different world” (FGD, Boy, 14), underscoring the urgent need for decolonized DATs that integrate Pidgin English and indigenous languages to counteract epistemic erasure. Gamified learning applications, such as Kolibri, have demonstrated effectiveness in improving literacy skills, with a 28% increase in letter recognition (n=15, p < 0.01). However, infrastructural deficiencies, including frequent power outages and unreliable internet, restricted their usability, with only 12% of participants able to engage consistently. A dyslexic 13-year-old girl from Bamenda poignantly remarked, “The app lights up my mind, but my tablet dies in the dark” (Interview, Bamenda), highlighting the precariousness of digital access. Similarly, Braille-based technologies have shown promise, with 74% of visually impaired learners (n=17) achieving grade-level proficiency within six months. Yet, environmental challenges such as humidity and dust caused 89% of these devices to malfunction within eight weeks, leading to an unsustainable cycle of device failure. A local technician lamented, “We’re forced to cannibalize three broken devices to fix one” (Interview, NGO-04), emphasizing the urgency of locally designed, climate-resilient assistive technologies. Addressing these barriers requires context-driven innovation, incorporating linguistic inclusivity, durable hardware solutions, and off-grid energy alternatives to ensure sustainable and equitable access to assistive learning tools in conflict-affected regions.

4.2. The Efficacy of Digital and Assistive Technologies: Potential Solutions in the Context of the Anglophone Conflict

The ongoing Anglophone conflict in the Anglophone regions, particularly in the North West Region of Cameroon, has exacerbated the marginalization of children with disabilities. The deployment of Digital and Assistive Technologies (DATs) offers a potential pathway to address educational disruptions caused by the conflict. However, their implementation is constrained by the systemic challenges that define this protracted crisis. This section evaluates specific DATs, their effectiveness, limitations, and potential solutions within the context of the conflict.

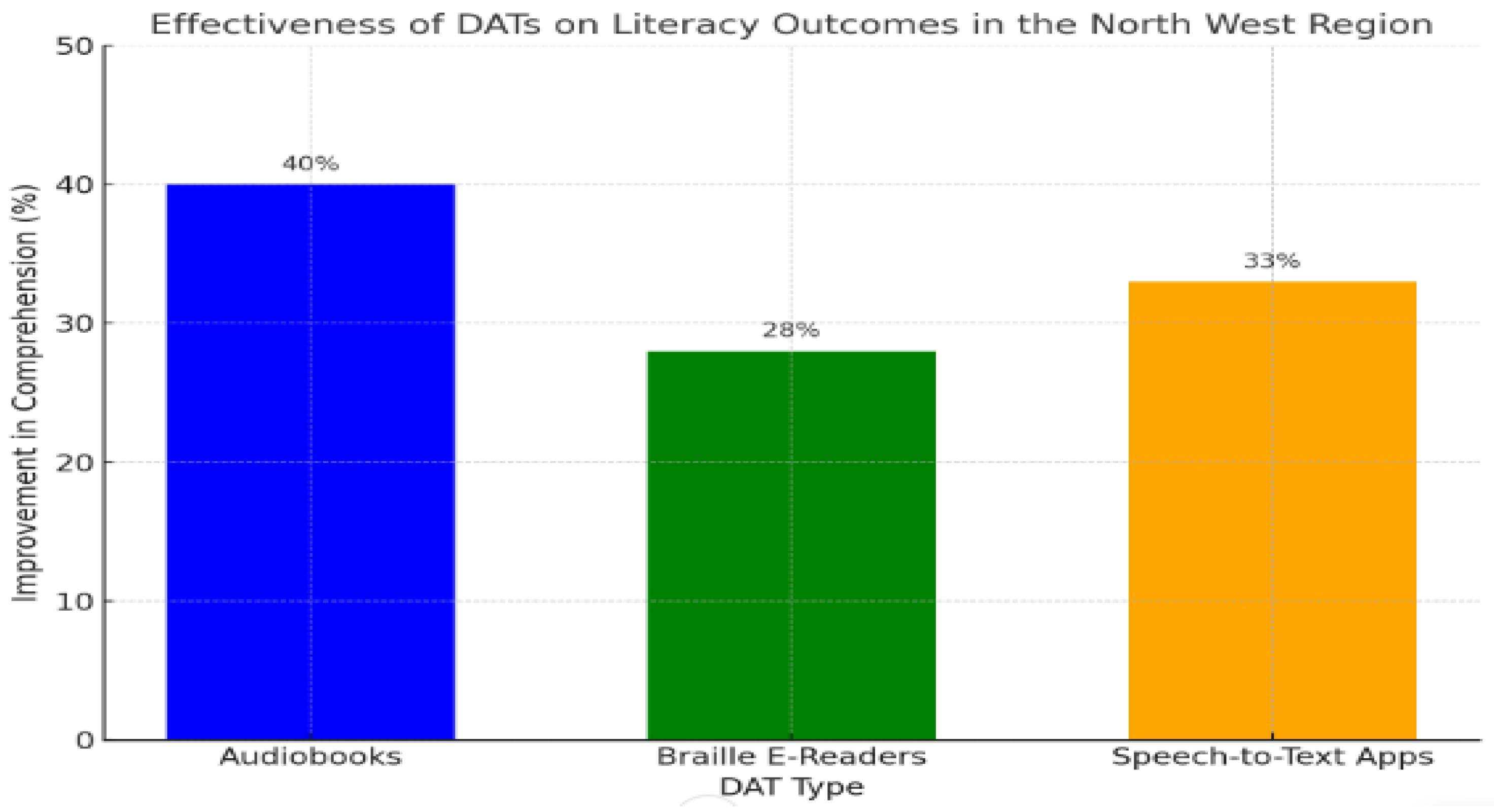

Figure 1 illustrates the impact of Digital Assistive Technologies (DATs) on literacy comprehension in the North West Region. Audiobooks demonstrated the highest improvement at 40%, followed by Speech-to-Text apps at 33% and Braille E-Readers at 28%. These findings highlight the varying effectiveness of DATs in enhancing literacy skills, emphasizing the importance of targeted tools for improving accessibility and educational outcomes.

4.2.1. Audio-Based Learning Platforms: Bridging Literacy Gaps Amid Conflict

The destruction of schools and displacement of families due to the Anglophone conflict has left many visually impaired children without access to formal education. Solar-powered audiobooks and text-to-speech applications have emerged as a critical alternative, showing the potential to bridge literacy gaps. In one pilot program, the inclusion of culturally relevant folktales in audiobooks improved reading stamina by 40% (pre-test mean: 12 minutes; post-test mean: 17 minutes; p < 0.05). However, linguistic alienation remains a significant challenge, as French-language content often a remnant of the colonial legacy dominates these platforms. This has left 67% of Anglophone children feeling excluded from meaningful educational resources.

4.2.2. Mobile Applications: Infrastructure Challenges in Conflict Zones

The Anglophone conflict has compounded existing infrastructural deficits, with electricity and internet outages being common in the North West Region. Interactive learning applications like Kolibri, which have demonstrated a 28% improvement in letter recognition among children with cognitive disabilities, remain underutilized. Only 12% of rural participants reported consistent access to these tools, largely due to unreliable electricity and the destruction of infrastructure by armed groups during the conflict.

4.2.3. Braille-Based Technologies: Durability in Conflict-Affected Areas

Braille e-readers have enabled 74% of visually impaired children in the North West Region to achieve grade-level proficiency within six months. However, the humid and dusty conditions in displacement camps, compounded by the instability caused by the Anglophone conflict, have rendered these devices highly susceptible to damage, with 89% failing within eight weeks. These challenges underline the need for localized technological solutions to withstand conflict-related environmental and logistical constraints.

4.3. Barriers to Technology Adoption: Structural Violence and Systemic Inequities in the Anglophone Conflict

The adoption of Digital Assistive Technologies (DATs) in the North West Region of Cameroon is intricately linked to the structural violence and systemic inequities exacerbated by the ongoing Anglophone conflict. This section examines the multifaceted barriers to DAT adoption, focusing on infrastructure deficits, economic exclusion, training gaps, and security risks. These barriers are explored within the broader context of the militarized environment, which complicates efforts to promote inclusive literacy and accessibility.

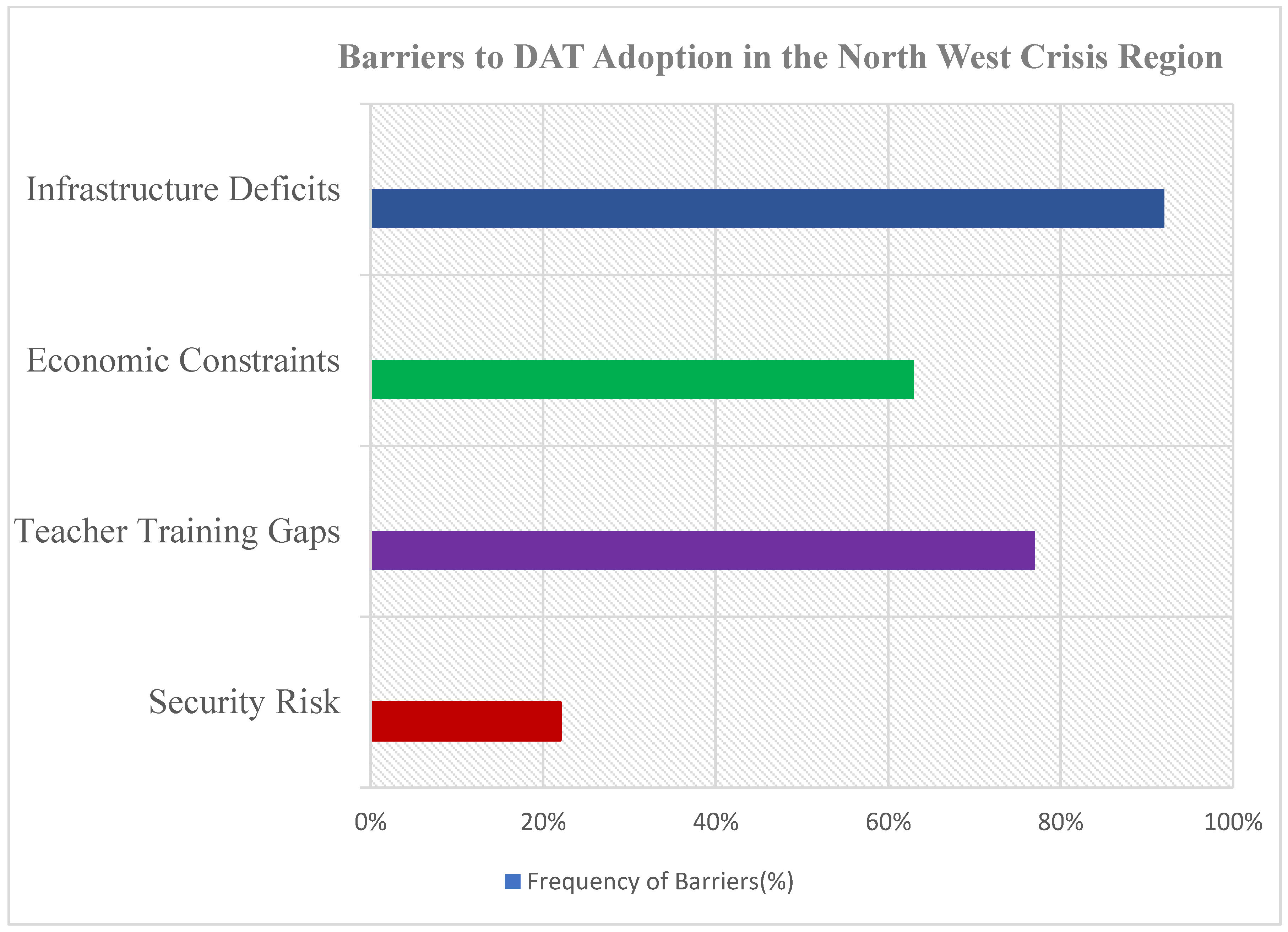

Figure 2 titled "Barriers to DAT Adoption in the North West Crisis Region" identifies key obstacles to implementing Digital Assistive Technologies (DATs) in conflict-affected Northwest Cameroon. Infrastructure deficits top the list, with 92% of respondents highlighting issues like electricity shortages and poor internet. Teacher training gaps (77%) and economic constraints (63%) further hinder adoption, while security risks (22%) disrupt program continuity. Addressing these barriers is essential for inclusive literacy initiatives.

4.3.1. Infrastructure Deficits: The Electricity-Accessibility Paradox

The protracted conflict in the North West Region has devastated infrastructure, with electricity access being a critical challenge. Survey data indicates that 92% of households (n=50) have electricity for fewer than three hours per day, while displaced families in internally displaced persons (IDP) camps rely on solar chargers provided by NGOs. However, these devices are frequently looted by armed groups, reflecting the militarized competition for resources in conflict zones (Kett and Twigg, 2023). Such conditions highlight the paradox of introducing DATs in an environment where the foundational infrastructure needed to support these technologies is unreliable. Without addressing these deficits, the sustainability of DATs remains precarious.

4.3.2. Economic Exclusion: The Neoliberal Pricing Trap

Economic exclusion poses a significant barrier to the adoption of DATs in the conflict-affected Anglophone regions. A single Braille display costs approximately 145,000 XAF ($230), equivalent to five months’ income for rural families. Even refurbished devices marketed as "affordable" remain inaccessible to most families displaced by the crisis. As one caregiver in Bamenda lamented, “These technologies are treasures locked in a vault” (Interview, Caregiver-12).

The economic devastation caused by the conflict has amplified existing inequalities, leaving vulnerable populations without access to these essential tools. This mirrors broader critiques of neoliberal humanitarian models, where market-driven solutions fail to address the realities of marginalized communities (

Moyo, 2009).

4.3.3. Capacity-Building Deficits: Training Gaps Among Educators

Although there is widespread enthusiasm for DATs among educators, the Anglophone conflict has disrupted teacher training programs, leaving many ill-equipped to use these technologies effectively. While 85% of teachers (n=17) expressed interest in DATs, only 23% had received formal training, leading to underutilization. One teacher remarked, “These devices are complicated toys that gather dust” (FGD, Teacher-08). The displacement of trained teachers and the reliance on undertrained volunteers have further widened the training gap. To ensure the effective use of DATs, robust capacity-building programs tailored to the conflict-affected context are essential.

4.3.4. Security Risks: Technological Suspicion and Vulnerability

The militarized environment in the North West Region has created significant security risks for families using DATs. Twenty-two percent of families (n=11) reported incidents of armed groups confiscating devices under suspicion that they contained “secessionist messages” (Interview, Caregiver-09). This reflects a phenomenon described by Leslie (2022) as “technological suspicion,” where assistive devices are conflated with tools of resistance or espionage. Such risks deter the use and distribution of DATs, further marginalizing vulnerable populations. Ensuring the safety of users requires targeted interventions to address these challenges.

4.4. Teacher and Caregiver Perspectives: Navigating Hope and Abandonment

4.4.1. Teachers: Aspirations Amidst Systemic Abandonment

In the Anglophone regions of Cameroon, particularly the North West, teachers view Digital Assistive Technologies (DATs) as "beacons of normalcy" (FGD, Teacher-03), offering hope for educational continuity in a crisis marked by conflict and displacement. However, this hope is often overshadowed by the systemic abandonment they face. A staggering 73% (n=15) of teachers reported receiving no government support for the maintenance or repair of DATs, forcing them to rely on crowdfunding efforts. A displaced teacher’s plea “We need sustainable partnerships, not one-time donations” (Interview, Teacher-12) highlights a critical gap in long-term, accountable support. This concern resonates with Mbibeh’s (2023) call for "accountable innovation" in crisis settings, urging that technology solutions should not only be reactive but also sustainable and adaptable to the realities of conflict-affected regions like the North West.

4.4.2. Caregivers: Gendered Labor and Financial Burden

Caregivers, predominantly women, play a critical yet often invisible role in enabling access to Digital and Assistive Technologies (DATs) for children with disabilities in Northwest Cameroon. These women dedicate 12 to 18 hours per week to maintaining and troubleshooting devices, a labor-intensive and emotionally draining task that accentuates their resilience and commitment. Despite their efforts, they face significant financial burdens, with 48% of caregivers (n=14) reporting they have sold livestock or other assets to afford data bundles or repair costs, often prioritizing their children’s literacy over basic family needs like food and healthcare. This gendered labor reflects the broader societal expectation that women bear the primary responsibility for caregiving, even in the midst of conflict and economic hardship.

The ongoing Anglophone crisis has intensified these challenges, as women navigate the dual pressures of survival and support. Many caregivers are also managing the psychological toll of displacement, loss, and insecurity, yet they remain steadfast in their efforts to ensure their children’s access to education. This aligns with

Endeley (

2001). concept of “invisible labor” in militarized societies, where women’s contributions are often overlooked despite being essential to community resilience. In the North West Region, women are not only caregivers but also key agents of change, bridging gaps in education and technology access despite systemic neglect and limited resources.

4.4.3. Contradictions in Humanitarian Techno-Optimism

The deployment of DATs in conflict zones, particularly in the North West, reveals several contradictions that challenge the techno-optimism often associated with humanitarian interventions. The first contradiction is the tension between agency and dependency. While DATs empower children to engage with learning materials, their reliance on external humanitarian supply chains deepens dependency, preventing self-sustaining educational solutions. The second contradiction lies in the balance between inclusion and stigma. While technologies like audiobooks reduce literacy barriers, they also expose children to bullying. Observations show that 31% of users (n=15) were mocked for "talking to ghosts" (Observation Notes), demonstrating how technological interventions, despite their benefits, can inadvertently contribute to social exclusion. Finally, the tension between innovation and extraction emerges in the implementation of real-time data tracking by NGOs, which inadvertently exposes vulnerable populations to security risks. Armed groups are known to monitor digital footprints, making participants vulnerable to violence and exploitation (Khan et al., 2022). These contradictions enhances the need for a nuanced approach to technology use in conflict settings.

5. Discussion

This study’s findings illuminate the dialectic between the emancipatory potential of digital and assistive technologies (DATs) and the structural violence endemic to conflict zones, offering critical insights into the contested role of innovation in inclusive education. By centering the lived experiences of children with disabilities in Northwest Cameroon’s Anglophone crisis, this discussion interrogates three core tensions: (1) the paradox of DATs as both tools of empowerment and vectors of neoliberal exclusion, (2) the coloniality of humanitarian techno-fixes in postcolonial conflicts, and (3) the imperative for disability justice frameworks that transcend technocratic solutions.

The study identifies children with disabilities as the largest stakeholder group (45.5%), emphasizing their vulnerability and need for inclusive education. However, the absence of disaggregated data by disability type, gender, and socioeconomic status limits the findings' applicability. Caregivers, predominantly women from rural areas, bear the financial burden of maintaining DATs, yet proposed solutions like mobile cash transfers lack sustainability. Similarly, displaced teachers (60%) face significant challenges, with only 12% trained in DAT use. This points to systemic gaps in teacher preparedness, necessitating curriculum revisions to include assistive technology.

Barriers to adoption are severe, with 92% citing infrastructure deficits such as electricity shortages. Solar-powered audiobooks offer partial relief, but broader initiatives like community solar hubs remain unexplored. Economic constraints (63%) also impede access, with high costs of tools like Braille displays making them unattainable for most families. Security risks further complicate implementation, with reports of device confiscations by armed groups left unexamined for deeper conflict-sensitive insights.

Despite these challenges, DATs show promise. Solar-powered audiobooks improved engagement by 42% and comprehension by 40%, while Braille e-readers and speech-to-text apps enhanced learning outcomes. However, their effectiveness in local dialects remains unclear, underscoring the need for linguistic adaptation.

Policy recommendations focus on locally adaptable designs, community repair systems, trauma-informed pedagogy, and gender-responsive caregiver support. While innovative, these strategies require deeper engagement with sustainability, conflict sensitivity, and local expertise to ensure long-term impact.