Submitted:

19 March 2025

Posted:

20 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Recruitment

2.2. IL-6 Determination

2.3. Neuropsychological Evaluation

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

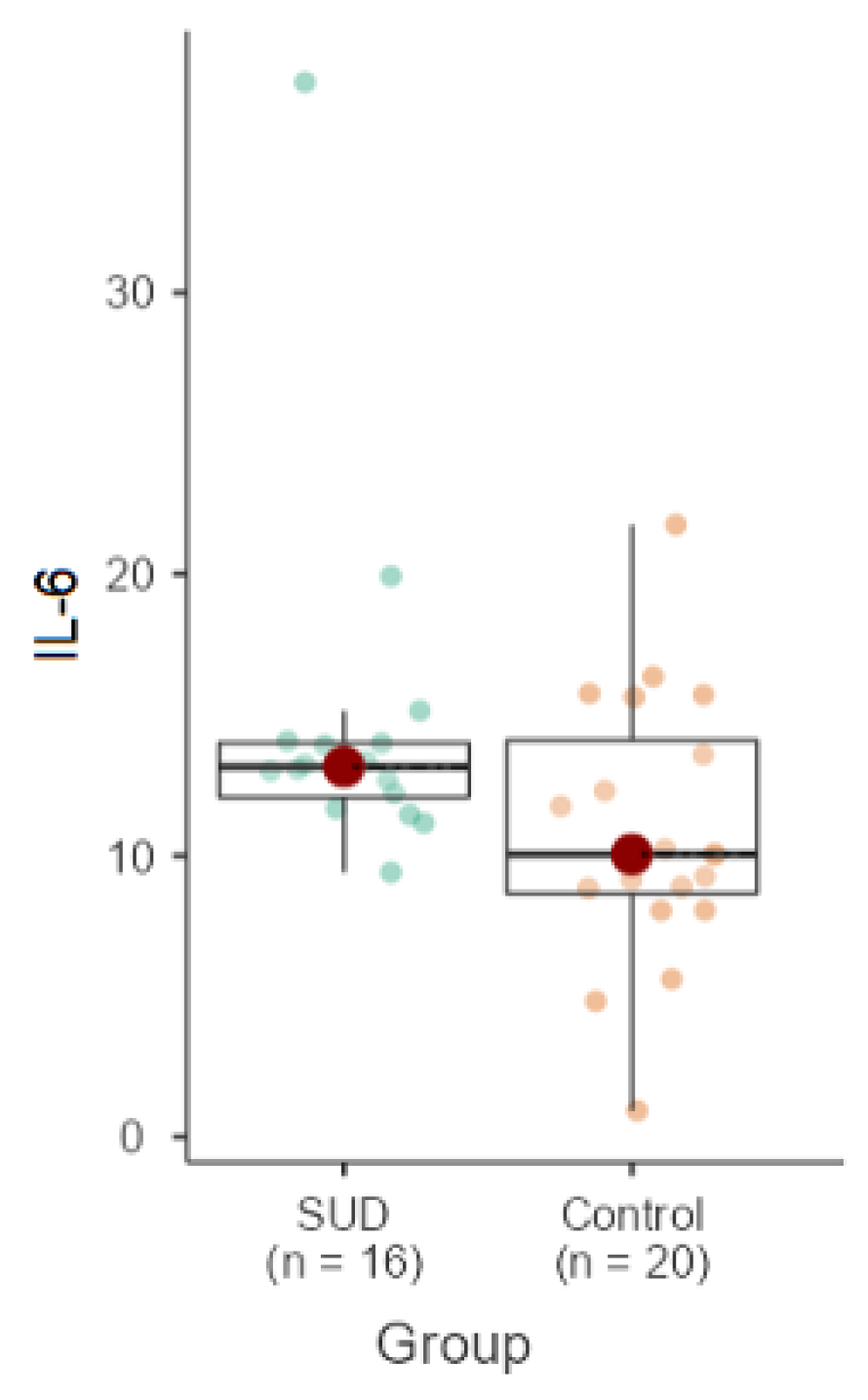

3.1. The plasma Levels of IL-6 Are Increased in Polydrug Male Consumers During Abstinence

3.2. Executive Dysfunction Persists in Polydrug Males During Abstinence

3.3. Correlations Between Cognitive Task Performance and Reaction Time

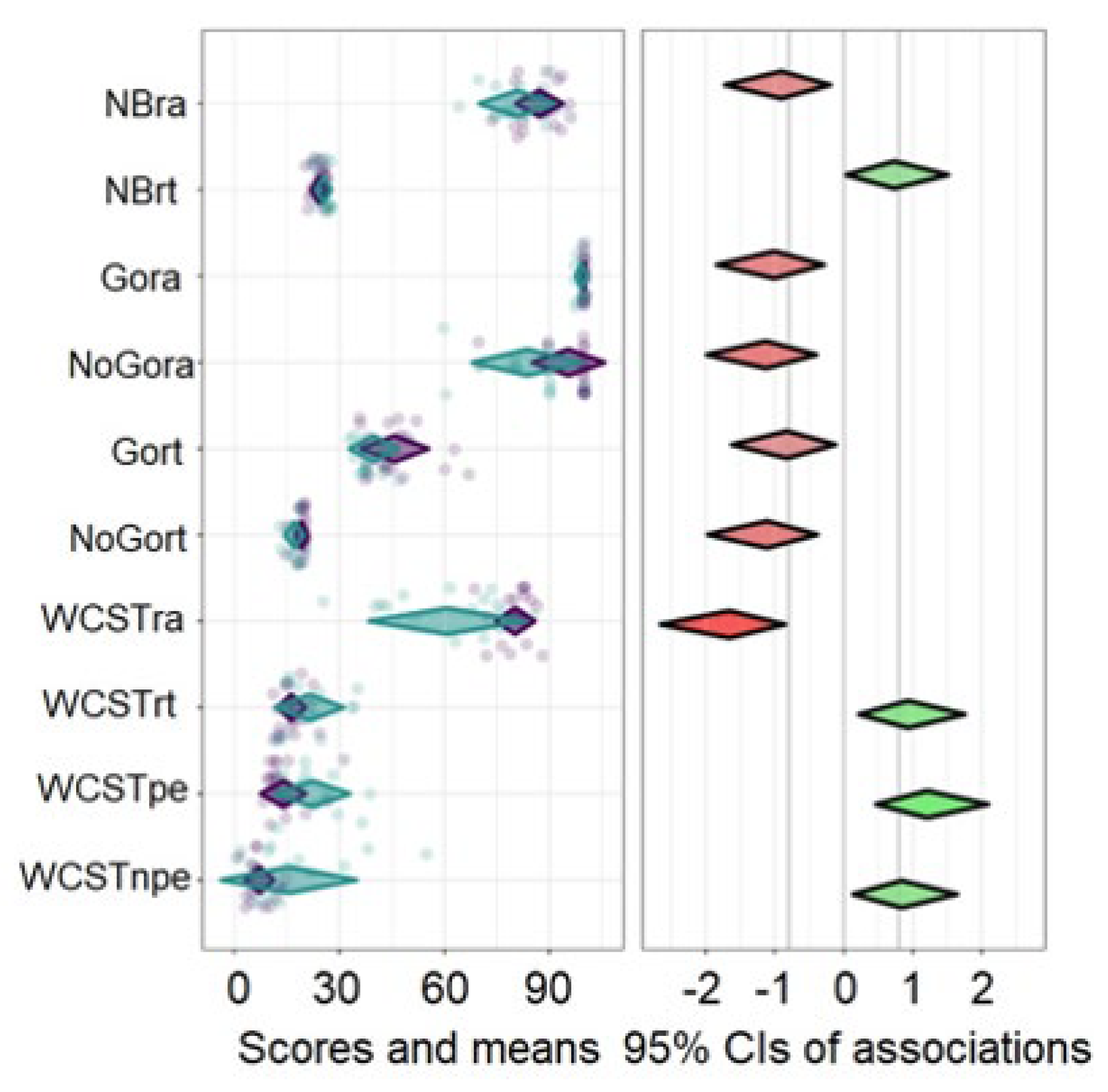

3.4. Plasma IL-6 Levels Correlate to Working Memory Performance in Adult Males

3.5. Inhibition and Cognitive Flexibility Are the Most Sensitive Cognitive Parameters That Differentiate EFs’ Performance Between the Groups

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Psychological Association. Clinical Psychology. 2020.

- Fillmore MT. Drug Abuse as a Problem of Impaired Control: Current Approaches and Findings. Behav Cogn Neurosci Rev [Internet]. 2003 Sep 18;2(3):179–97. Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1534582303257007. [CrossRef]

- Volkow ND, Wang G-J, Fowler JS, Logan J, Gatley SJ, Hitzemann R, et al. Decreased striatal dopaminergic responsiveness in detoxified cocaine-dependent subjects. Nature [Internet]. 1997 Apr;386(6627):830–3. Available from: http://www.nature.com/articles/386830a0.

- Koob GF, Volkow ND. Neurocircuitry of Addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology [Internet]. 2010 Jan 26;35(1):217–38. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/npp2009110.

- Casey BJ, Jones RM. Neurobiology of the Adolescent Brain and Behavior: Implications for Substance Use Disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry [Internet]. 2010 Dec;49(12):1189–201. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0890856710006702.

- Lezak MD, Howieson D, Bigler E, Tranel D. Neuropsychological Assessment. 5th ed. New York: Oxford University Press Inc; 2012.

- Gilbert SJ, Burgess PW. Executive function. Curr Biol [Internet]. 2008 Feb;18(3):R110–4. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0960982207023676.

- Miyake A, Friedman NP, Emerson MJ, Witzki AH, Howerter A, Wager TD. The Unity and Diversity of Executive Functions and Their Contributions to Complex “Frontal Lobe” Tasks: A Latent Variable Analysis. Cogn Psychol. 2000 Aug;41(1):49–100.

- Aharonovich E, Nunes E, Hasin D. Cognitive impairment, retention and abstinence among cocaine abusers in cognitive-behavioral treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend [Internet]. 2003 Aug 20;71(2):207–11. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0376871603000929.

- Blume AW, Alan Marlatt G. The Role of Executive Cognitive Functions in Changing Substance Use: What We Know and What We Need to Know. Ann Behav Med [Internet]. 2009 Apr 28;37(2):117–25. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/abm/article/37/2/117-125/4565848.

- Horner MD, Harvey RT, Denier CA. Self-report and objective measures of cognitive deficit in patients entering substance abuse treatment. Psychiatry Res [Internet]. 1999 May;86(2):155–61. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0165178199000311.

- Aharonovich E, Hasin DS, Brooks AC, Liu X, Bisaga A, Nunes E V. Cognitive deficits predict low treatment retention in cocaine dependent patients. Drug Alcohol Depend [Internet]. 2006 Feb;81(3):313–22. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0376871605002516.

- Loftis JM, Choi D, Hoffman W, Huckans MS. Methamphetamine causes persistent immune dysregulation: a cross-species, translational report. Neurotox Res [Internet]. 2011 Jul;20(1):59–68. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20953917.

- Wisor JP, Schmidt MA, Clegern WC. Cerebral microglia mediate sleep/wake and neuroinflammatory effects of methamphetamine. Brain Behav Immun [Internet]. 2011 May;25(4):767–76. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21333736.

- Hanisch U-K. Microglia as a source and target of cytokines. Glia [Internet]. 2002 Nov;40(2):140–55. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/glia.10161. [CrossRef]

- Kreutzberg GW. Microglia: a sensor for pathological events in the CNS. Trends Neurosci [Internet]. 1996 Aug;19(8):312–8. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/0166223696100497.

- Sekine Y, Iyo M, Ouchi Y, Matsunaga T, Tsukada H, Okada H, et al. Methamphetamine-Related Psychiatric Symptoms and Reduced Brain Dopamine Transporters Studied With PET. Am J Psychiatry [Internet]. 2001 Aug;158(8):1206–14. Available from: http://psychiatryonline.org/doi/abs/10.1176/appi.ajp.158.8.1206. [CrossRef]

- Felger JC, Li Z, Haroon E, Woolwine BJ, Jung MY, Hu X, et al. Inflammation is associated with decreased functional connectivity within corticostriatal reward circuitry in depression. Mol Psychiatry [Internet]. 2016 Oct 10;21(10):1358–65. Available from: http://www.nature.com/articles/mp2015168.

- Kohno M, Loftis JM, Huckans M, Dennis LE, McCready H, Hoffman WF. The relationship between interleukin-6 and functional connectivity in methamphetamine users. Neurosci Lett [Internet]. 2018 Jun;677:49–54. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0304394018303008.

- Dean AC, Kohno M, Morales AM, Ghahremani DG, London ED. Denial in methamphetamine users: Associations with cognition and functional connectivity in brain. Drug Alcohol Depend [Internet]. 2015 Jun 1;151:84–91. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25840750.

- Dean AC, Kohno M, Hellemann G, London ED. Childhood maltreatment and amygdala connectivity in methamphetamine dependence: a pilot study. Brain Behav [Internet]. 2014;4(6):867–76. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25365801.

- Kohno M, Morales AM, Ghahremani DG, Hellemann G, London ED. Risky decision making, prefrontal cortex, and mesocorticolimbic functional connectivity in methamphetamine dependence. JAMA psychiatry [Internet]. 2014 Jul 1;71(7):812–20. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24850532.

- Jankord R, Turk JR, Schadt JC, Casati J, Ganjam VK, Price EM, et al. Sex Difference in Link between Interleukin-6 and Stress. Endocrinology [Internet]. 2007 Aug 1;148(8):3758–64. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/endo/article/148/8/3758/2502096.

- Anthenelli RM, Heffner JL, Blom TJ, Daniel BE, McKenna BS, Wand GS. Sex differences in the ACTH and cortisol response to pharmacological probes are stressor-specific and occur regardless of alcohol dependence history. Psychoneuroendocrinology [Internet]. 2018 Aug;94:72–82. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0306453017316384.

- Lockwood KG, Marsland AL, Cohen S, Gianaros PJ. Sex differences in the association between stressor-evoked interleukin-6 reactivity and C-reactive protein. Brain Behav Immun [Internet]. 2016 Nov;58:173–80. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0889159116301957.

- Carroll ME, Anker JJ. Sex differences and ovarian hormones in animal models of drug dependence. Horm Behav [Internet]. 2010 Jun;58(1):44–56. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0018506X09002219.

- Levandowski ML, Hess ARB, Grassi-Oliveira R, de Almeida RMM. Plasma interleukin-6 and executive function in crack cocaine-dependent women. Neurosci Lett [Internet]. 2016 Aug;628:85–90. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0304394016304323.

- Illenberger JM, Mactutus CF, Booze RM, Harrod SB. Testing environment shape differentially modulates baseline and nicotine-induced changes in behavior: Sex differences, hypoactivity, and behavioral sensitization. Pharmacol Biochem Behav [Internet]. 2018 Feb;165:14–24. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0091305717305270.

- Fattore L, Marti M, Mostallino R, Castelli MP. Sex and Gender Differences in the Effects of Novel Psychoactive Substances. Brain Sci [Internet]. 2020 Sep 3;10(9):606. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3425/10/9/606.

- Peters G-JY, Crutzen R. Establishing determinant relevance using CIBER: an introduction and tutorial [Internet]. 2018. Available from: https://osf.io/5wjy4.

- Crutzen R, Ygram-Peters GJ, Noijen J. Using confidence interval-based estimation of relevance to select social-cognitive determinants for behavior change interventions. 2017;

- Stoet G. PsyToolkit: A software package for programming psychological experiments using Linux. Behav Res Methods. 2010 Nov;42(4):1096–104.

- Valentine G, Sofuoglu M. Cognitive Effects of Nicotine: Recent Progress. Curr Neuropharmacol [Internet]. 2018 May 1;16(4):403–14. Available from: http://www.eurekaselect.com/156791/article.

- Ashare RL, Schmidt HD. Optimizing treatments for nicotine dependence by increasing cognitive performance during withdrawal. Expert Opin Drug Discov [Internet]. 2014 Jun;9(6):579–94. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24707983.

- Wei Z, Chen L, Zhang J, Cheng Y. Aberrations in peripheral inflammatory cytokine levels in substance use disorders: a meta-analysis of 74 studies. Addiction [Internet]. 2020 Dec 18;115(12):2257–67. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/add.15160. [CrossRef]

- Kubera M, Filip M, Budziszewska B, Basta-Kaim A, Wydra K, Leskiewicz M, et al. Immunosuppression Induced by a Conditioned Stimulus Associated With Cocaine Self-Administration. J Pharmacol Sci [Internet]. 2008;107(4):361–9. Available from: http://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/jphs/107/4/107_FP0072106/_article.

- Elenkov IJ. Glucocorticoids and the Th1/Th2 Balance. Ann N Y Acad Sci [Internet]. 2004 Jun;1024(1):138–46. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1196/annals.1321.010. [CrossRef]

- Harrod SB, Booze RM, Welch M, Browning CE, Mactutus CF. Acute and repeated intravenous cocaine-induced locomotor activity is altered as a function of sex and gonadectomy. Pharmacol Biochem Behav [Internet]. 2005 Sep;82(1):170–81. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0091305705002777.

- Becker JB, McClellan ML, Reed BG. Sex differences, gender and addiction. J Neurosci Res [Internet]. 2017 Jan 2;95(1–2):136–47. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/jnr.23963. [CrossRef]

- Fox HC, Sinha R. Sex Differences in Drug-Related Stress-System Changes. Harv Rev Psychiatry [Internet]. 2009 Apr;17(2):103–19. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/00023727-200904000-00004.

- Harrod SB, Mactutus CF, Bennett K, Hasselrot U, Wu G, Welch M, et al. Sex differences and repeated intravenous nicotine: behavioral sensitization and dopamine receptors. Pharmacol Biochem Behav [Internet]. 2004 Jul;78(3):581–92. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0091305704001546.

- Jacobskind JS, Rosinger ZJ, Zuloaga DG. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis responsiveness to methamphetamine is modulated by gonadectomy in males. Brain Res [Internet]. 2017 Dec;1677:74–85. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0006899317304171.

- Volkow ND, Chang L, Wang G-J, Fowler JS, Ding Y-S, Sedler M, et al. Low Level of Brain Dopamine D 2 Receptors in Methamphetamine Abusers: Association With Metabolism in the Orbitofrontal Cortex. Am J Psychiatry [Internet]. 2001 Dec;158(12):2015–21. Available from: http://psychiatryonline.org/doi/abs/10.1176/appi.ajp.158.12.2015. [CrossRef]

- Said EA, Al-Reesi I, Al-Shizawi N, Jaju S, Al-Balushi MS, Koh CY, et al. Defining IL-6 levels in healthy individuals: A meta-analysis. J Med Virol [Internet]. 2021 Jun 22;93(6):3915–24. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/jmv.26654. [CrossRef]

- Luo Y, He H, Ou Y, Zhou Y, Fan N. Elevated serum levels of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-18 in chronic methamphetamine users. Hum Psychopharmacol Clin Exp [Internet]. 2022 Jan 25;37(1). Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hup.2810. [CrossRef]

- Trevizol AP, Brietzke E, Grigolon RB, Subramaniapillai M, McIntyre RS, Mansur RB. Peripheral interleukin-6 levels and working memory in non-obese adults: A post-hoc analysis from the CALERIE study. Nutrition [Internet]. 2019 Feb;58:18–22. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30273821.

- Vervoort L, Naets T, De Guchtenaere A, Tanghe A, Braet C. Using confidence interval-based estimation of relevance to explore bottom-up and top-down determinants of problematic eating behavior in children and adolescents with obesity from a dual pathway perspective. Appetite [Internet]. 2020 Jul 1;150:104676. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32198094.

- Sewpaul R, Crutzen R, Reddy P. Psychosocial determinants of the intention and self-efficacy to attend antenatal appointments among pregnant adolescents and young women in Cape Town, South Africa: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2022 Sep 23;22(1):1809. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36151528.

- Srisurapanont M, Lamyai W, Pono K, Indrakamhaeng D, Saengsin A, Songhong N, et al. Cognitive impairment in methamphetamine users with recent psychosis: A cross-sectional study in Thailand. Drug Alcohol Depend [Internet]. 2020 May;210:107961. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0376871620301265.

- Lugones-Sanchez C, Crutzen R, Recio-Rodriguez JI, Garcia-Ortiz L. Establishing the relevance of psychological determinants regarding physical activity in people with overweight and obesity. Int J Clin Health Psychol [Internet]. 2021;21(3):100250. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33995540.

- Crutzen R, Peters G-JY. A lean method for selecting determinants when developing behavior change interventions. Heal Psychol Behav Med [Internet]. 2023 Dec 31;11(1). Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/21642850.2023.2167719. [CrossRef]

- Charlton RA, Lamar M, Zhang A, Ren X, Ajilore O, Pandey GN, et al. Associations between pro-inflammatory cytokines, learning, and memory in late-life depression and healthy aging. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry [Internet]. 2018 Jan;33(1):104–12. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/gps.4686.

- Uddin LQ. Cognitive and behavioural flexibility: neural mechanisms and clinical considerations. Nat Rev Neurosci [Internet]. 2021 Mar 3;22(3):167–79. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41583-021-00428-w.

- Teubner-Rhodes S, Vaden KI, Dubno JR, Eckert MA. Cognitive persistence: Development and validation of a novel measure from the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test. Neuropsychologia [Internet]. 2017 Jul;102:95–108. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0028393217302014.

- Joutsa J, Moussawi K, Siddiqi SH, Abdolahi A, Drew W, Cohen AL, et al. Brain lesions disrupting addiction map to a common human brain circuit. Nat Med [Internet]. 2022 Jun 13;28(6):1249–55. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41591-022-01834-y.

- Colzato LS, Huizinga M, Hommel B. Recreational cocaine polydrug use impairs cognitive flexibility but not working memory. Psychopharmacology (Berl) [Internet]. 2009 Dec 2;207(2):225–34. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00213-009-1650-0.

- Morein-Zamir S, Robbins TW. Fronto-striatal circuits in response-inhibition: Relevance to addiction. Brain Res [Internet]. 2015 Dec;1628:117–29. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0006899314011998.

- Sjoberg EA, Cole GG. Sex Differences on the Go/No-Go Test of Inhibition. Arch Sex Behav [Internet]. 2018 Feb 12;47(2):537–42. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10508-017-1010-9.

- Young ME, Sutherland SC, McCoy AW. Optimal go/no-go ratios to maximize false alarms. Behav Res Methods [Internet]. 2018 Jun 29;50(3):1020–9. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.3758/s13428-017-0923-5.

- Bari A, Robbins TW. Inhibition and impulsivity: Behavioral and neural basis of response control. Prog Neurobiol [Internet]. 2013 Sep;108:44–79. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0301008213000543.

- Barker MJ, Greenwood KM, Jackson M, Crowe SF. Cognitive Effects of Long-Term Benzodiazepine Use. CNS Drugs [Internet]. 2004;18(1):37–48. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.2165/00023210-200418010-00004.

- Loeber S, Duka T, Welzel Marquez H, Nakovics H, Heinz A, Mann K, et al. Effects of Repeated Withdrawal from Alcohol on Recovery of Cognitive Impairment under Abstinence and Rate of Relapse. Alcohol Alcohol [Internet]. 2010 Nov 1;45(6):541–7. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/alcalc/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/alcalc/agq065.

- Munro CA, Saxton J, Butters MA. The neuropsychological consequences of abstinence among older alcoholics: a cross-sectional study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res [Internet]. 2000 Oct;24(10):1510–6. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11045859.

- Proebstl L, Krause D, Kamp F, Hager L, Manz K, Schacht-Jablonowsky M, et al. Methamphetamine withdrawal and the restoration of cognitive functions – a study over a course of 6 months abstinence. Psychiatry Res [Internet]. 2019 Nov;281:112599. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0165178119314933.

- Hardwick RM, Forrence AD, Costello MG, Zackowski K, Haith AM. Age-related increases in reaction time result from slower preparation, not delayed initiation. J Neurophysiol [Internet]. 2022 Sep 1;128(3):582–92. Available from: https://journals.physiology.org/doi/10.1152/jn.00072.2022. [CrossRef]

- Cheng C-H, Tsai H-Y, Cheng H-N. The effect of age on N2 and P3 components: A meta-analysis of Go/Nogo tasks. Brain Cogn [Internet]. 2019 Oct;135:103574. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0278262618303737.

- Yaple ZA, Stevens WD, Arsalidou M. Meta-analyses of the n-back working memory task: fMRI evidence of age-related changes in prefrontal cortex involvement across the adult lifespan. Neuroimage [Internet]. 2019 Aug;196:16–31. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1053811919302812.

| Control Med(IQR) |

SUD Med (IQR) |

Statistical test | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 21.0 (2.0) | 24.5 (7.75) | U = 108.5, δ = 0.48, p = 0.15 |

| Year of schooling | 12.0 (0.0) | 12.0 (0.0) | U = 186.5, δ = 0.27, p = 0.29 |

| Days with abstinence | 171 (59.8) | ||

| f (%) | |||

| Consumption type | |||

| Alcohol | 16 (100%) | ||

| Tobacco | 16 (100%) | ||

| Inhalants | 2 (10.53%) | ||

| Cannabinoids | 6 (31.58%) | ||

| Benzodiazepines | 1 (5.26%) | ||

| Methamphetamines | 16 (100%) | ||

| Sociodemographic data are expressed as the median (Med) and interquartile rank (IQR), and frequency (f) of. Statistical analysis: Mann-Whitney U test. | |||

| Test | Control Med (IQR) |

SUD Med (IQR) |

U | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NBack right answer | 88.66 (82.33-92.00) | 80 (74.67-88.00) | 86 | 0.019* |

| NBack reaction time | 25.00(22.36-25.59) | 25.96(24.17-26.66) | 94 | 0.037* |

| Go-no-go right answer Go | 100 (100-100) | 100 ((97.50-100) | 110 | 0.009** |

| Go-no-go right answer no-go | 100 (97.50-100) | 90 (80.00-90.00) | 58.5 | 0.001* |

| Go-no-go reaction time Go | 43.91 (38.39-48.13) | 37-56 (36.50-44.03) | 88 | 0.023* |

| Go-no-go reaction time no-go | 20.00 (19.59-20.00) | 18.27(16.49-18.31) | 60 | 0.001*** |

| WCST right answer | 81.66 (78.33-83.33) | 65.83 (47.08-73.75) | 35 | 0.001*** |

| WCST reaction time | 15.82 (13.65-17.96) | 20.59 (15.36-24) | 101 | 0.063 |

| WCST perseverative errors | 11.66 (10-15) | 20 ((15.00-27.08) | 53.5 | 0.001*** |

| WCST non-perseverative errors | 6.66 (5.00-8.75) | 10 (6.25-19.17) | 99 | 0.053 |

| Data are expressed as the median (M) and the interquartile rank (IQR). WSCT = Wisconsin sort card test; NB = N-Back test. Statistical differences were established with the Mann-Whitney U test (P < 0.05). | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).